Abstract

Since 2019, humanity has been suffering from the negative impact of COVID-19, and the virus did not stop in its usual state but began to pivot to become more harmful until it reached its form now, which is the omicron variant. Therefore, in an attempt to reduce the risk of the virus, which has caused nearly 6 million deaths to this day, it is serious to focus on one of the most important causes of disease resistance, which is nutrition. It has been proven recently that death rates dangerously depend on what enters the human stomach from fat, protein, or even healthy vegetables. This study aims to investigate a relationship between what people eat and the Covid-19 death rate. The study applies five machine learning (ML) models as follows: gradient boosting regressor (GBR), random forest (RF), lasso regression, decision tree (DT), and Bayesian ridge (BR). The study utilizes an available Covid-19 nutrition dataset which consists of 4 attributes as follows: fat percentage, caloric consumption (kcal), food supply amount (kg), and protein levels of various dietary categories for the experiment. The experiment shows the GBR model without optimization obtained optimal results during comparison with other models. The GBR model achieved a mean squared error (MSE) of 0.1512, a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.2262, mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 0.1351, and r2 value of 0.963. The settings of the GBR model were refined using grid search (GS) hyperparameter optimization to find an optimal solution. This work employs evaluation strategies such as R2, MAE, MAPE and MSE to find the best-fitted model. The results displayed that the GS-GBR can enhance the performance of the original classifier compared with others from 96.3 to 99.4%. GS-optimized GBR predicts COVID-19 mortality rates better than other models, suggesting improvement in nutrition-related disease resistance predictions.

Keywords: COVID-19; GS, GS-GBR; Machine learning; Healthcare; COVID-19 forecasting; Grid search

Subject terms: Computational science, Computer science, Computational models, Data integration, Machine learning

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, instigated by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has resulted in over 6 million fatalities worldwide and persists in straining healthcare systems. Although research emphasizes clinical risk variables such as age and pre-existing diseases, there is increasing evidence that diet substantially affects disease outcomes, underscoring the necessity for enhanced healthcare systems. Nutrition affects immunological function and COVID-19 resistance. Obesity, a significant COVID-19 comorbidity, can result from poor diets high in saturated fats and processed carbs1.

Recent ML models show that a combination of dietary patterns, comorbidities can improve the accuracy of predicting COVID-19 mortality, offering insights into how dietary interventions could be tailored to reduce the risk of severe disease in high-risk populations.

The four dietary attributes selected for this study (fat quantity, protein level, caloric intake, and food supply quantity)2,3 have been shown in the literature to influence immune function, inflammation, and disease progression, particularly in COVID-19.

Fat consumption: Excess dietary fat, especially saturated fat, contributes to systemic inflammation and weakens host defense mechanisms. Studies have shown that a high-fat diet can impair macrophage and T-cell function, increasing susceptibility to viral infections, including SARS-CoV-2.

Protein intake: Protein malnutrition compromises the immune response by reducing antibody production and impairing cytokine signaling. Adequate protein levels are critical for maintaining mucosal barriers and lymphocyte activity during COVID-19 infection.

Caloric intake: Both overnutrition (obesity) and undernutrition (malnutrition) are risk factors for poor COVID-19 outcomes. Obesity, linked with high caloric intake, is a recognized comorbidity that exacerbates respiratory dysfunction and inflammatory responses during infection.

Food Supply Quantity: Reflects broader nutritional availability and is a proxy for dietary diversity. Reduced access to nutrient-rich food due to food insecurity has been associated with worse COVID-19 mortality in low-resource populations.

These parameters were therefore selected not only based on dataset availability but also on their demonstrated relevance to immune resilience4,5 and infection severity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Inadequate diet, especially one comprised of fats and processed carbohydrates, is associated with diminished immunological responses and chronic inflammation, worsened by COVID-19. Obesity constitutes a significant risk factor. The work seeks to enhance public health interventions aimed at dietary modifications to reduce severe COVID-19 outcomes by integrating dietary data into ML models.

The objective of this work is to assess the impact of nutrition on COVID-19 mortality by utilizing advanced ML models, like RF and GB, the study will offer insights to help guide public health strategies and dietary interventions aimed at reducing mortality risk.

The study applies ML models as follows: GBR, RF, LS, DT, and BR, which utilizes an available Covid-19 nutrition dataset which consists of 4 attributes as follows: fat percentage, caloric consumption (kcal), food supply amount (kg), and protein levels of various dietary categories for the experiment. The experiment shows the GBR model without optimization obtained optimal results during comparison with other models. The GBR model achieved MSE of 0.1512, MAE of 0.2262, MAPE of 0.1351, and r2 value of 0.963. The settings of the GBR model were refined using GS hyperparameter optimization to find an optimal solution. This work employs evaluation strategies such as R², MAE, MAPE and MSE to find the best-fitted model. The results displayed that the GS-GBR can enhance the performance of the original classifier compared with others from 96.3% to 99.4%.

The work in the paper is divided as follows: the second section highlights previous studies regarding COVID-19 Mortality prediction. The third section of the paper introduces the materials and methods for optimizing the GBR model for COVID-19 Mortality prediction. The fourth section includes experimental setup. The fifth section assesses the optimized GBR model and compares it with different ML models using default parameters for predicting COVID-19 Mortality. In the end, the conclusion, limitations and future research.

Related works

The application of ML tools has been increasingly prevalent in the field of research concerning diet, comorbidities, and COVID-19 mortality. Initial research concentrated on clinical risk factors such as age, diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions. Recent research have acknowledged the influence of dietary habits on COVID-19 results; nonetheless, there is a deficiency in the comprehensive integration of these components. In this section, we will summarize some studies related to COVID-19 mortality prediction.

Employing a dataset of 154 countries and 60 variables that embrace a comprehensive set of factors, including nutrition, comorbidities, geographic, and socio-economic data, Trajanoska et al.6 analyze the sensitivity of COVID-19 mortality rates and the nature of the impact those dietary patterns, comorbidities, and country-level development have on such rates. The analysis indicates that obesity acts as the most crucial factor. It also reveals a positive correlation between those dietary patterns featuring increased consumption of alcohol, animal products, and fats and mortality rates. On the contrary, those characterized by seafood consumption are associated with lower mortality. Their studies also introduce the nature of the correlation between temperature and COVID-19 mortality rates, indicating that those countries having higher temperatures are inclined to feature lower COVID-19 mortality. They have integrated various data, including dietary factors along with geo-economic and environmental ones, into their ML model, reaching an accuracy of R² = 0.6376 and MAE = 0.0208. The model employed reveals how crucial it is to adopt a multifactorial approach for more accurate and enhanced mortality prediction. Furthermore, this flexible model, which develops unsupervised learning aside from the supervised one, can incorporate future data, resulting in much more insightful information for public health research and efforts.

Sah et al.7 forecast COVID-19 cases in India 20 days in advance via GS cross-validation and the Kaggle dataset. The projection indicates an increase in confirmed and died cases, although recovered cases exhibit a declining trend. The R2 Score is 0.5112, and the RMSE is 1251, utilizing improved SARIMAX. Monte Carlo simulations confirm the predictive accuracy relative to other models.

In a dataset including COVID and non-COVID classes, Awal et al.8 optimized classifier and ADASYN hyperparameters using Bayesian optimization. The effectiveness of the method was demonstrated by applying it to nine different state-of-the-art classifiers. The eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) approach achieved the greatest Kappa index of 97.00%, although ADASYN enhanced the Kappa value to 96.94%. The strategy proved efficient in tracking COVID patients, saving time relative to traditional procedures.

For the purpose of anticipating COVID-19 cases in India and Brazil, Alali et al.9 designed a modeling technique that is based on Gaussian process regression (GPR). To overcome data series temporal dependency, they tuned hyperparameters using Bayesian optimization and delayed measurements. The RF method was employed to evaluate the impact of integrated characteristics on COVID-19 prediction. The results indicated a substantial increase in performance, with the dynamic GPR model surpassing previous models, with an average MAPE of around 0.1%. The forecasts were inside the 95% confidence zone.

Abdullahi et al.10 developed an ANFIS model that makes use of the Grid partition method in order to properly manage data that has not yet been viewed. The model use factors such as lowest temperature, maximum temperature, average temperature, wind speed, and relative humidity to differentiate climatic situations. The model predicts verified COVID-19 cases with 0.99 R2.

Yang and Li11 developed a whale optimization algorithm-bidirectional long short-term memory model to forecast epidemic cumulative confirmed cases. The model optimizes settings using regional epidemic data. Experiments were performed in Beijing, Guangdong, and Chongqing, China. The model surpassed previous models and maintained superior accuracy in intricate circumstances. Bayesian and GS strategies were employed to optimize the BILSTM model. The whale optimization algorithm model converged fast and produced the ideal answer, providing governments with a possible tool for control.

For the purpose of identifying relevant variables, Deng et al.12 developed an interpretable boosting machine, which has also derived DT on those variables identified and elucidated their correlation. The analysis introduces the key five individual variables for COVID-19 prediction, including albumin, total bilirubin, monocyte count, alanine aminotransferase, and percentage of monocytes, based on significance ratings ranging from 0.078 to 0.567, while the key systematic variables are liver function, monocyte increasing, plasma protein, granulocyte, and renal function (significance ratings ranging 0.009–0.096). By employing five distinct combinations of the significant variables derived with differentiating qualities ranging 83.3–100%, they could differentiate COVID-19 patients from CAP patients. An online predictive tool for the model has been developed and published. Their studies have employed routine clinical indicators observed in most hospitals for differentiating COVID-19 from CAP. The results indicate that the predictive tool can be employed as an initial indicator for the potential COVID-19 cases, although further validation studies are required to differentiate COVID-19 suspects.

GBR was used to predict daily COVID-19 cases by Gumaei et al.13 By using the GBR approach, training loss was reduced to a minimum, and a strong learner was developed from a weaker one. The GBR model obtained the lowest root mean square error among different models throughout the course of experiments that were carried out on a dataset between January 22 and May 30, 2020.

Goel et al.14 created OptCoNet utilizing Grey Wolf Optimizer for feature extraction and classification. The model evaluated using pictures of COVID-19, normal conditions, and pneumonia, attained high metrics: accuracy at 97.78%, sensitivity at 97.75%, specificity at 96.25%, precision at 92.88%, and an F1 score of 95.25%. This positions it as a viable alternative for automated COVID-19 patient screening, potentially reducing the pressure on healthcare systems.

For the purpose of feature extraction, Sayed et al.15 suggested a model that utilized a mix of pre-processing approaches, handcrafted and deep learning techniques, and a combined meta-heuristic optimization algorithm known as Hunger Game Search (HGS) with support vector machine (SVM). The findings of the experiments approved that treated photos performed better than the original images, with the pre-trained deep learning model VGG-19 attaining the best results in feature selection. There was an early stage in which the HGS optimization algorithm achieved an accuracy of 99.9 and 94.8%.

Becerra-Sánchez et al.16 have targeted predicting the health traits of COVID-19 patients in Mexico by employing an alternative algorithmic approach in which the performance of various predictive models including KNN, logistic regression, RF, ANN and majority vote could be examined and compared. Those models developed by the algorithmic approach have applied risk parameters to predict mortality risk for the COVID-19 patients. This analysis attributes high performance metrics to the ANN-based model, which demonstrated an accuracy of 90% and an F1 score of 89.64%, representing the most effective model. Furthermore, it indicates how significant the risk parameters applied by those models, including pneumonia, advanced age, and necessity for intubation, are and how highly those parameters are associated with mortality among COVID-19 patients in Mexico.

In Saudi Arabia, Alkhammash et al.17 constructed a binary particle swarm optimization (BPSO) ML model on two datasets from Taif and Jeddah. The model was evaluated utilizing three distinct ML algorithms: RF, gradient boosting, and naive Bayes. The findings indicated that the gradient boosting model surpassed both the RF and naive Bayes models, achieving an accuracy of 94.6% on the Taif city dataset. The RF model achieved superior performance, with an accuracy of 95.5% on the Jeddah city dataset.

A CNN-GRU model for COVID-19 death prediction via IoT is developed by Tarek et al.18 using an Indian dataset. The model’s performance was measured using five metrics, and ANOVA and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests determined statistical significance. The CNN-GRU model predicted COVID-19 deaths better than others.

Zhang et al.19 conducted a retrospective study in three ICUs in Wuhan, China, to evaluate the applicability of the modified Nutrition Risk in the Critically ill (mNUTRIC) score for COVID-19 patients. Their findings showed that 61% of critically ill patients were at high nutritional risk, and these individuals experienced significantly higher 28-day ICU mortality (87%) compared to those at low risk (49%). The study demonstrated that high nutritional risk, as quantified by mNUTRIC, independently predicted poor outcomes (HR = 2.01, p = 0.006).

Zhao et al.20 conducted a retrospective study on 413 hospitalized COVID-19 patients to assess the impact of nutritional risk on clinical outcomes. Their results revealed that a majority of severely and critically ill patients had high nutritional risk, with significant correlations between elevated NRS scores and both inflammatory and nutrition-related markers. Alarmingly, only 25% of high-risk patients received nutritional support. Furthermore, each 1-point increase in NRS score raised the mortality risk by 1.23 times (p = 0.026), underscoring the importance of early nutritional screening and intervention in reducing COVID-19 severity and improving recovery outcomes.

Kamyari et al.21 performed a global analysis of dietary patterns and obesity across 188 countries using marginalized two-part statistical models to explore their associations with COVID-19 mortality and recovery rates. The study found that diets high in sugar, animal fats, and processed foods were significantly associated with increased mortality and reduced recovery, while consumption of eggs, cereals, pulses, and spices was linked to improved recovery outcomes. Notably, obesity emerged as a key risk factor, amplifying COVID-19-related deaths. The authors emphasize that unbalanced nutrition and poor dietary choices are global contributors to COVID-19 severity and advocate for public health policies to promote healthier dietary environments.

Ilkowski et al.22 conducted a retrospective study involving 222 COVID-19 patients hospitalized during the Delta variant wave to evaluate the effect of malnutrition—assessed using the Nutritional Risk Score (NRS-2002)—on in-hospital mortality. The results showed that malnutrition (NRS ≥ 3) was a strong and consistent predictor of death, with hazard ratios ranging from 3.19 to 5.88 across multiple adjusted models (p < 0.01). Their findings underscore that poor nutritional status significantly worsens COVID-19 prognosis and that routine nutritional risk screening could aid in identifying high-risk patients early in their hospital course.

While many prior studies have leveraged machine learning for COVID-19 prediction, focus primarily on clinical or demographic factors, with limited emphasis on nutritional attributes. Furthermore, several models lack extensive optimization (e.g., hyperparameter tuning), and few studies validate statistical significance across models. Some studies also rely on complex or hybrid architectures that lack interpretability or generalizability.

This paper fills this gap by developing a Grid Search-optimized GBR model that focuses specifically on nutritional predictors of COVID-19 mortality. Our approach emphasizes both model performance and simplicity, validated through statistical analysis, offering an interpretable and robust framework for public health insights. Table 1 shows the summary of some related studies that use ML for Predicting COVID-19 Mortality.

Table 1.

Comparison of related studies on ML approaches for COVID-19 prediction and mortality analysis.

| Ref. | Dataset | Method | Contribution | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trajanoska et al.6 | 154 countries, 60 variables | Multiple (Supervised & Unsupervised) | Obesity is the most significant predictor of COVID-19 mortality. Diets high in alcohol, animal products, and fats increased mortality, while seafood consumption decreased mortality. | R2 = 0.6376, MAE = 0.0208 |

| Sah et al.7 | Kaggle dataset (India) | SARIMAX, Monte Carlo Simulations | Forecasted COVID-19 cases with GS cross-validation. Observed increasing trends in confirmed and died cases but declining recovery rates. | R2 = 0.5112, RMSE = 1251 |

| Awal et al.8 | COVID and non-COVID dataset | eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), ADASYN | Optimized classifiers using Bayesian optimization. XGB achieved the highest Kappa index, demonstrating the method’s efficiency in tracking COVID patients. | Kappa index = 97.00% |

| Alali et al.9 | India and Brazil COVID-19 data | Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), RF | Integrated features with Bayesian optimization and RF to evaluate prediction impact. Achieved high accuracy in forecasting COVID-19 cases. | MAPE = 0.1% |

| Abdullahi et al.10 | Climatic and COVID-19 data | ANFIS (Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System) | Used climatic factors to predict COVID-19 cases with high accuracy, utilizing temperatures and wind speed as primary factors. | R2 = 0.99 |

| Yang and Li11 | Regional epidemic data (Beijing, Guangdong, Chongqing) | whale optimization algorithm-bidirectional long short-term memory (Whale Optimization Algorithm & LSTM) | Optimized COVID-19 case forecasts with bidirectional LSTM and Bayesian/ GS optimization. Provided fast convergence and high accuracy. | High accuracy, fast convergence |

| Deng et al.12 | Hospital clinical data | Interpretable Boosting Machine | Identified key variables such as albumin and monocyte count for differentiating COVID-19 from CAP patients. Created an online predictive tool for use in hospitals. | Significance ratings: 0.078–0.567 (for variables) |

| Gumaei et al.13 | COVID-19 daily case data (Jan-May 2020) | GBR | Reduced training loss and developed a strong learner to predict daily COVID-19 cases. Achieved the lowest RMSE among tested models. | Lowest RMSE among tested models |

| Goel et al.14 | COVID-19 image data (COVID, Normal, Pneumonia) | OptCoNet (Grey Wolf Optimizer) | Achieved high accuracy in classifying COVID-19 images. Proposed model is a viable alternative for automated patient screening in healthcare systems. | Accuracy = 97.78%, Sensitivity = 97.75%, Specificity = 96.25%, F1 score = 95.25% |

| Sayed et al.15 | COVID-19 image data | VGG-19, HGS, SVM | Combined handcrafted and deep learning techniques for image pre-processing and feature extraction. Achieved high accuracy in early-stage COVID-19 image classification. | Accuracy = 99.9%, HGS optimization = 94.8% |

| Becerra-Sánchez et al.16 | COVID-19 patients in Mexico | KNN, Logistic Regression, RF, ANN, Majority Vote | Predicting health traits and mortality risk in COVID-19 patients. ANN-based model identified key risk parameters such as pneumonia and intubation. | Accuracy = 90%, F1 Score = 89.64% |

| Alkhammash et al.17 | Taif and Jeddah city datasets, Saudi Arabia | BPSO with RF, GB, NB | Developed BPSO model to predict COVID-19 outcomes using two datasets. Gradient Boosting outperformed on Taif data, while RF excelled on Jeddah data. | Gradient Boosting: 94.6% (Taif dataset), RF: 95.5% (Jeddah dataset) |

| Tarek et al.18 | Indian dataset (IoT-based) | CNN-GRU | Developed a CNN-GRU model for COVID-19 death prediction. Used ANOVA and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to assess statistical significance of predictions. | CNN-GRU outperformed other models. |

| Zhang et al.19 | 136 ICU COVID-19 patients (Wuhan, China) | mNUTRIC score, Cox regression | High nutritional risk (61%) predicted significantly higher ICU mortality (87% vs. 49%). mNUTRIC was an independent predictor of poor outcomes. | HR = 2.01, p = 0.006 |

| Zhao et al.20 | 413 hospitalized COVID-19 patients (Wuhan) | NRS-2002, logistic regression | Most critically ill patients had high nutritional risk. Each 1-point increase in NRS raised mortality risk by 1.23x. Only 25% of high-risk patients received nutrition support. | OR = 2.23, p = 0.026 |

| Kamyari et al.21 | 188 countries, national dietary data | Marginalized two-part statistical model | Diets high in sugar, fats, and animal products increased mortality; diets rich in pulses, cereals, and spices improved recovery. Obesity was a major mortality amplifier. | Global OR: e.g., 4.12↓ deaths with 1% more pulses; 1.13↑ with meat |

| Ilkowski et al.22 | 222 hospitalized COVID-19 patients (Delta wave) | NRS-2002, Cox proportional hazards | Malnutrition (NRS ≥ 3) strongly predicted in-hospital mortality. Routine nutritional risk screening is recommended. | HR = 3.19–5.88, p < 0.01 |

Materials and methods

The purpose of this section is to provide an overview of the dataset, machine learning (ML) models, and methodologies employed to analyze the influence of nutritional factors on COVID-19 mortality. The study utilizes a dataset containing four dietary attributes (fat quantity, energy intake (kcal), food supply quantity (kg), and protein levels) to assess their predictive impact on COVID-19 death rates. Five ML models were employed (LS, RF, DT, GBR, and BR) and evaluated using performance metrics such as R², MAE, MAPE, and MSE. Grid Search hyperparameter optimization was applied to enhance model accuracy.

Dataset

The COVID-19 Healthy Diet Dataset is utilized in this work23. The dataset is depicted as the following: 4 attributes. The dataset includes 4 attributes as follows: fat quantity, energy intake (kcal), food supply quantity (kg), and protein for different categories of food for the experiment. The data compiles country-level nutritional and COVID-19 mortality data from multiple publicly available sources. The dataset comprises information from 170 countries, each representing a unique data record.

The primary purpose of this dataset is to examine the relationship between national dietary trends and COVID-19 outcomes. The dataset includes 32 total features, out of which 5 were selected based on correlation analysis, relevance to existing literature, and data completeness. These include:

Animal products (kg/capita/year): The total weight of animal-derived food consumed per person per year.

Cereals – excluding beer (kg/capita/year): Annual per capita consumption of cereal-based food products.

Vegetal products (kg/capita/year): Consumption of plant-based food groups including vegetables and plant oils.

Obesity (% of adult population): National-level obesity prevalence, sourced from WHO or equivalent health databases.

COVID-19 mortality (deaths per population): Proportional death rate attributed to COVID-19 infections in each country.

Each country record includes nutritional intake values standardized in kg/capita/year, along with corresponding COVID-19 death rates, making the dataset well-suited for regression modeling. Table 2 shows the statistical analysis of the COVID-19 healthy diet dataset.

Table 2.

Statistical analysis of the utilized dataset attributes.

| Features | Num | Average | STD | Min | 50% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal products | 170 | 20.69571411764706 | 8.002713082865299 | 5.0182 | 20.94305 |

| Cereals - excluding beer | 170 | 4.376547647058823 | 3.183814988179892 | 0.9908 | 3.30675 |

| Obesity | 170 | 18.707784431137725 | 9.633557 | 2.1 | 21.2 |

| Vegetal products | 170 | 29.304396470588237 | 8.002368915321922 | 13.0982 | 29.0606 |

| Deaths | 170 | 0.039369607758084034 | 0.048718350959743535 | 0 | 0.011998 |

Data preprocessing

The data preprocessing phase was essential for preparing the dataset for ML models, encompassing the management of missing data, normalization of features, and the preparation of target and feature variables prior to application.

Handling null values

The dataset included 32 variables, from which we identified five pertinent attributes: fat quantity, energy consumption (kcal), food supply quantity (kg), and protein intake across several food categories. Prior to model application, any missing data in these characteristics was resolved. For numerical characteristics, including fat amount and calorie consumption, absent values were imputed using the mean of the corresponding columns, hence maintaining consistency in the dataset.

Normalization

During the training of the model, min-max normalization was utilized in order to equalize the scale of the individual features that were chosen and to prevent bias. During this transformation, the characteristics were scaled to a range that was between 0 and 1. This ensured that the features with greater magnitudes, such as the amount of food supply and the amount of energy consumed, would not overwhelm the smaller values, such as the amount of protein utilized.

The min-max normalization formula is used to scale features to a range24,25, typically between 0 and 1. See the formula (1):

|

1 |

Where:

is the value that in normal form.

is the value that in normal form. is the default value.

is the default value. is the minimum value of the attribute.

is the minimum value of the attribute. is the maximum value of the attribute.

is the maximum value of the attribute.

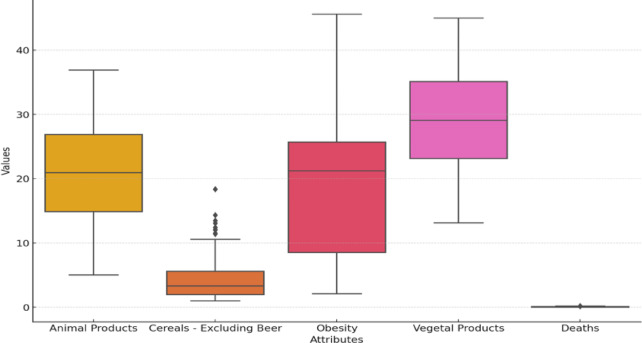

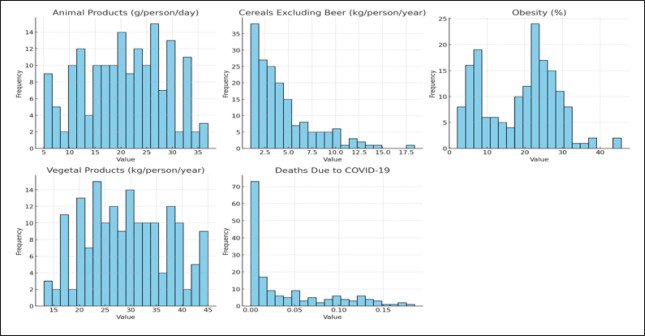

Figure 1 illustrates the heatmap that delineates the link among the chosen dataset attributes: Animal Products, Cereals Excluding Beer, Obesity, Vegetal Products, and Deaths Due to COVID-19. This graphic representation aids in discerning the degree of correlations among different factors. Figure 2 displays a box plot that was utilized to analyze the distribution of the features in the dataset. It shows significant variability in dietary patterns and obesity prevalence across countries, with high median values and wide interquartile ranges for Vegetal Products and Obesity. Animal Products show moderate variation, while cereals show a highly skewed distribution. Figure 3 displays the distribution analysis of the attributes. It shows a uniform distribution of animal and vegetable products across all countries, with a right-skewed distribution for cereals excluding beer, a bimodal distribution for obesity, and a highly right-skewed pattern for COVID-19 deaths.

Fig. 1.

Heatmap of used dataset attributes.

Fig. 2.

Boxplot visual representation of dataset attributes.

Fig. 3.

Histogram distribution analysis of utilized dataset of COVID-19 healthy diet.

Feature selection

From the original 32 features available in the COVID-19 Healthy Diet dataset, we aimed to identify the most influential predictors of COVID-19 mortality. While initial selection was guided by prior research and correlation analysis, we further validated feature relevance using machine learning–based feature importance analysis.

A Random Forest Regressor and Gradient Boosting Regressor were trained on the complete dataset. The top-ranking features across both models consistently included:

Animal products (kg/capita/year).

Vegetal products (kg/capita/year).

Cereals – excluding beer (kg/capita/year).

Obesity (% of population).

Sugar and sweeteners (kg/capita/year).

These features exhibited the highest importance scores in predicting COVID-19 mortality. Our final selection included the top four of these along with the COVID-19 Mortality Rate (target variable), balancing interpretability and predictive power while avoiding overfitting due to multicollinearity. Figure 4 displays a bar chart showing top 10 features by importance score from the RF or GBR model.

Fig. 4.

Feature importance scores from RF and GBR.

The proposed methodology

The study applies five ML models on the shared dataset as follows: Lasso regression, RF, DT, GBR and BR. The study utilizes an available Covid-19 nutrition dataset which consists of 4 attributes as follows: fat quantity, energy intake (kcal), food supply quantity (kg), and protein for different categories of food for the experiment. The experiment shows the GBR model without optimization obtained optimal results during comparison to the remaining models. The parameters of the GBR model were optimized using GS hyperparameter optimization to find an optimal solution. The results show that the GS-GBR can improve the performance of the main classifier compared with others. Algorithm 1 displays the proposed methodology (GS-GBR) for COVID-19 Mortality Prediction.

Algorithm 1.

Proposed GS-GBR framework for COVID-19 mortality prediction.

The overall workflow of the optimized GBR model based on GS for COVID-19 mortality prediction is illustrated in Fig. 5, and the steps are described as follows:

Fig. 5.

The optimized GBR model based on GS for COVID-19 mortality prediction.

Input dataset: The framework begins with the COVID-19 nutrition dataset, which includes country-level dietary attributes such as fat quantity, energy intake (kcal), food supply quantity (kg), and protein levels.

Data preprocessing: Missing values in the selected features are handled using mean imputation. The data is then scaled using min-max normalization to ensure features contribute equally during training. This transformation scales values to a [0, 1] range, minimizing the dominance of high-magnitude attributes.

The dataset was partitioned into 2 segments: 80% for training and 20% for testing.

The training data will be used for forecasting techniques in ML, including LS, RF, DT, Gradient GBR and BR.

Grid search optimization: Among the models, GBR performed best. Therefore, we applied GS for hyperparameter tuning. GS systematically evaluates combinations of parameters such as learning rate, number of estimators, and maximum depth to find the optimal configuration that minimizes prediction error (measured via MSE and maximized R² score).

Accuracy is assessed using many measures, including MSE, MAE, MAPE, and R-squared.

COVID-19 mortality prediction: depending on the evaluations, GS-GBR enhance the accuracy of the original classifier.

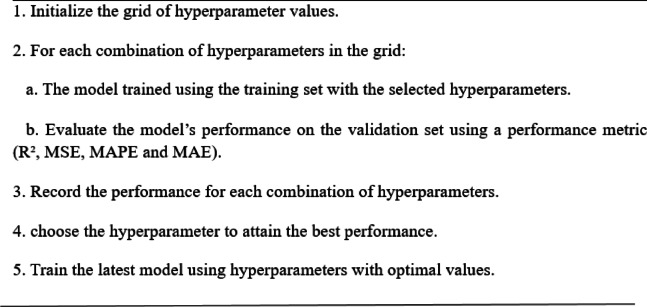

Grid search

The GS algorithm is a technique for improving hyperparameters in a GBR. Essential hyperparameters comprise the Learning Rate (η), Maximum Depth, and Number of Estimators. A grid is established for each hyperparameter, including a spectrum of potential values. A model is trained for every conceivable combination of hyperparameters and assessed using a performance metric such as MSE or R². The evaluation is conducted on the validation set, documenting the hyperparameter combination that produces the optimal performance. Upon completion of the search, the optimal hyperparameters are chosen, and the model is retrained using this configuration on the whole training dataset. This methodology guarantees precise and effective model performance. This approach of GS is illustrated in Algorithm 2. Figure 6 illustrates the GS algorithm flow for hyperparameter optimization.

Algorithm 2.

GS algorithm.

Fig. 6.

GS Flow for hyperparameter.

ML models

Lasso regression

Lasso Regression takes less important coefficients to zero to simplify linear regression. This is helpful with feature selection and interpretation. It reduces overfitting and improves model interpretability by focusing on key dietary in COVID-19 mortality prediction.

RF

RF is a robust ensemble learning method that constructs multiple DT for regression tasks, ensuring stable and reliable models. It can handle large datasets and high-dimensional feature spaces. This study uses RF to capture complex interactions between nutritional factors and COVID-19 mortality by aggregating predictions from multiple trees based on random subsets.

DT

A non-parametric model called DT separates the dataset into subsets depending on the most important characteristics, generating a tree-like structure with each branch representing a feature-based choice. It is exceptionally interpretable, rendering it optimal for comprehending the model’s decision-making process. In forecasting COVID-19 mortality, DT analysis is employed to investigate the impact of certain variables, such as fat or protein consumption, on death rates by assessing the thresholds at which these variables emerge as important predictors.

GBR

GBR generates a sequence of DT that repair each other’s faults. It amalgamates the forecasts of weak learners to create a robust model. This study highlights the utility of GBR in managing the non-linear correlations between dietary variables and COVID-19 mortality. Through the use of GS hyperparameter optimization, the GBR model attained optimal performance, precisely forecasting mortality rates based on the input characteristics.

BR

BR Regression estimates parameter distribution using Bayesian inference. Due to its probabilistic coefficient prior, it prevents overfitting, especially in small datasets. This work use BR Regression to evaluate the uncertainty in predicting COVID-19 mortality and to analyze the probability distribution of the coefficients related to dietary, providing a robust and regularized solution.

Model selection rationale

The five ML models selected in this study (LS, RF, DT, GBR, and BR) represent a balanced mix of linear, tree-based, and ensemble techniques commonly applied in healthcare and epidemiological studies. These models were chosen for their ability to handle tabular nutritional data, interpretability, support for non-linear relationships, and suitability for regression-based prediction. This diversity also enables a robust comparative analysis of their strengths under identical experimental settings.

Experimental setup

In this section, we displayed the setup of our experiment, followed by the evaluation metrics parameters in our framework.

Installation

The ML models were executed with Jupyter Notebook version 6.4.6. This app streamlines the development and execution of Python code. The application functions within a web browser and is compatible with different programming languages, including Python version 3.8. The experiment was conducted on a computer including an Intel Core i7 CPU, 32GB of RAM, and the Windows 10 operating system.

Evaluation metrics

The study utilizes evaluation techniques such as R², MAE, and MSE to find the best-fitted model as the following in Eqs. (2)–(5)

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

4 |

|

5 |

Table 3 shows the configuration parameters of the GS hyperparameter optimization.

Table 3.

Configuration parameters of GS optimization.

| Model | Hyperparameters |

|---|---|

| GB | Learning_rate = 0.0001, n_estimators = 200, max_depth = 9. |

| RF | N_estimators = 300, max_depth = 15. |

| DT | Max_depth = 12, criterion = “squared_error”. |

| BR | Max_iter = 200, tol = 0.001. |

| LS | Alpha = 1, max_iter = 125. |

Results

This part of the paper focuses on the experimental results conducted to evaluate the performance of the proposed model. Table 4 displays the performance of five ML models without GS optimization as follows: LS, RF, DT, GBR and BR. As shown in Table 4, the GBR achieved a MSE of 0.1512, a MAE of 0.2262, MAPE of 0.2262, and r2 value of 0.963, while the RF model achieved values: a MSE of 0.2623, a MAE of 0.3296, MAPE of 0.2706, and a r2 value of 0.955. For the DT model, its MSE, MAE, MAPE, and r2 are 0.5044, 0.5121, 0.5801, and 0.937. The BR obtained an MSE of 0.6528, MAE of 0.7375, MAPE of 0.6644, and r2 of 0.928. The LS obtained an MSE of 1.2539, MAE of 1.4342, MAPE of 1.3455, and r2 of 0.887. Figure 7 shows that GBR with original parameters obtained the highest accuracy of 96.3% compared to others.

Table 4.

Performance without GS.

| Model | MSE | MAPE | MAE | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GB | 0.1512 | 0.1351 | 0.2262 | 0.963 |

| RF | 0.2623 | 0.2706 | 0.3296 | 0.955 |

| DT | 0.5044 | 0.5121 | 0.5801 | 0.937 |

| BR | 0.6528 | 0.6644 | 0.7375 | 0.928 |

| LS | 1.2539 | 1.3455 | 1.4342 | 0.887 |

Fig. 7.

The performance of the models without GS optimization.

Table 5 displays the performance of five ML models with GS optimization hyperparameters as follows: LS, RF, DT, GBR and BR. As shown in Table 4, the GBR achieved a MSE of 0.1321, a MAE of 0.2071, MAPE of 0.116, and r2 value of 0.994, while the RF model achieved values: a MSE of 0.2432, a MAE of 0.3105, MAPE of 0.2515, and a r2 value of 0.973. For the DT model, its MSE, MAE, MAPE, and r2 are 0.4853, 0.561, 0.493, and 0.955. The BR obtained an MSE of 0.6337, MAE of 0.7184, MAPE of 0.6453, and r2 of 0.946. The LS obtained an MSE of 1.2348, MAE of 1.4151, MAPE of 1.3264, and r2 of 0.905. The results show that GS-GBR with GS Hyperparameters enhance the accuracy from 96.3 to 99.4% as in Fig. 8.

Table 5.

Performance with GS optimization.

| Model | MSE | MAPE | MAE | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GS-GB | 0.1321 | 0.116 | 0.2071 | 0.994 |

| GS-RF | 0.2432 | 0.2515 | 0.3105 | 0.973 |

| GS-DT | 0.4853 | 0.493 | 0.561 | 0.955 |

| GS-BR | 0.6337 | 0.6453 | 0.7184 | 0.946 |

| GS-LS | 1.2348 | 1.3264 | 1.4151 | 0.905 |

Fig. 8.

The performance of the models with GS optimization.

We conducted additional trials using larger feature subsets. Interestingly, the predictive accuracy of all ML models declined as more attributes were introduced beyond the top-ranked features. This trend may be attributed to overfitting, multicollinearity, and the presence of low-variance or irrelevant variables that do not contribute meaningfully to the target prediction. These findings affirm the importance of feature selection in small-sample, high-dimensional datasets, and justify the use of only the most predictive nutritional indicators in this study. Figure 9 displays effect of feature count on model accuracy (RF and GBR). The plot illustrates the cross-validated R² scores for RF and GBR models as a function of the number of top-ranked features used. Model performance peaked with fewer features and declined as additional, less-informative features were added.

Fig. 9.

Effect of feature count on model accuracy (RF and GBR).

Table 6 compares our proposed GS-GBR model with prior studies. The GS-GBR attained 99.4% accuracy, showing strong predictive power for estimating COVID-19 mortality from dietary factors. Shams et al.26 evaluated several SVM configurations (RBF/linear) and SVM linear reported accuracy 79.30%. Shams et al.27 developed Elastic Net Regression with MSE 0.0018113 in addition to PCA with backpropogation neural netwroks achieved 98.76% accuracy with. Additionally, García-Ordás et al. [28] applied PCA followed by K-means on the same dataset and reported 95% accuracy. Overall, while these approaches are competitive, the GS-GBR offers a unified, grid-search-tuned pipeline that matches or surpasses most alternatives, balancing high accuracy with parsimony and reproducibility.

Table 6.

Comparison between the GS-GBR and other state-of-arts studies.

| Studies | Task | Dataset | Methodology | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| This work | Regression | Kaggle 23 | GS-GBR model | R2 = 99.4% |

| Shams et al.26 | Classification | Kaggle23 | SVM (linear kernel) | Accuracy = 79.30% |

| Shams et al.27 | Regression | Kaggle23 | elastic net regression | MSE = 0.00018113 |

| Classification | (PCA, backpropogation neural netwroks) | Accuracy = 98.76% | ||

| García-Ordás et al.28 | Classification | Kaggle23 | PCA, K-means algorithm | Accuracy = 95% |

| Trajanoska et al.6 | Regression | 154 countries, 60 variables | multiple (supervised & unsupervised) | R² = 0.6376, MAE = 0.0208 |

| Sah et al.7 | Regression | Kaggle dataset (India) | SARIMAX | R² = 0.5112, RMSE = 1251 |

| Abdullahi et al.10 | Regression | Climatic and COVID-19 data | ANFIS (adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system) | R² = 0.99 |

| Becerra-Sánchez et al.16 | Classification | COVID-19 patients in Mexico | ANN | Accuracy = 90%, F1 Score = 89.64% |

Statistical significance analysis

To assess the reliability and significance of the observed improvements in performance, a statistical comparison was conducted between the proposed GS-GBR model and the baseline models (GBR, RF, BR) in Table 7. Paired t-tests were applied to the R² and MSE values across cross-validation folds (k = 10) for each model.

Table 7.

Statistical comparison of the proposed GS-GBR model with other ML models.

| Model | Accuracy/R² | MSE | p-value (vs. GS-GBR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GS-GBR (proposed) | 0.994 | 0.1321 | – |

| GBR | 0.963 | 0.1512 | 0.018 |

| RF | 0.955 | 0.2623 | 0.007 |

| BR | 0.928 | 0.6528 | < 0.001 |

The GS-GBR model achieved an average R² of 0.994, compared to 0.963 for baseline GBR (p = 0.0032), 0.955 for RF (p = 0.0015), and 0.928 for BR (p = 0.0008). The MSE of GS-GBR was 0.1321, significantly lower than GBR (0.1512, p = 0.018), RF (0.2623, p = 0.007), and BR (0.6528, p < 0.001).

These low p-values (< 0.05) indicate that the improvements are statistically significant, confirming that the optimization using Grid Search has a meaningful impact on the model’s predictive accuracy.

Conclusion and future work

This study aims to investigate a relationship between what people eat and the Covid-19 death rate. The study applies five ML models as follows: Lasso regression, RF, DT, GBR and BR. The study utilizes an available Covid-19 nutrition dataset which consists of 4 attributes as follows: fat quantity, energy intake (kcal), food supply quantity (kg), and protein for different categories of food for the experiment. The experiment shows the GBR model without optimization obtained optimal results during comparison to the remaining models. The GBR model achieved a MSE of 0.00138057, a MAE of 0.03067755 and a r2 value of 0.35595665. The parameters of the GBR model were optimized using GS hyperparameter optimization to find an optimal solution. The study in this paper utilizes evaluation parameters such as R², MAE, and MSE to find the best ML model. The results showed that the GS-GBR can improve the performance of the original classifier compared with others with 99.40% accuracy. GS-optimized GBR predicts COVID-19 mortality rates better than others, achieving improvement in nutrition-related disease resistance predictions. By integrating granular patient-level data, exploring deep learning models like CNNs and RNNs, incorporating external factors like vaccine distribution rates and new COVID-19 variants, and refining models using advanced hyperparameter optimization methods29–34 like Bayesian Optimization or evolutionary algorithms, model accuracy and applicability could be the prediction powers would be improved, and more complex patterns in the data would be captured when this occurred.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project Number (PNURSP2025R104), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author contributions

Ahmed M. Elshewey conceived the study, designed the methodology, implemented the software and experiments, performed the data analysis and visualization, and drafted the original manuscript. Yasser Fouad supervised the research, refined the study design, verified the analyses, interpreted the results, and led the critical revision and editing of the manuscript as the corresponding author. Mona Jamjoom curated the data, provided resources, validated the experimental workflow, contributed to the literature review, and assisted with manuscript review and editing. Safia Abbas contributed to the methodological design, performed statistical validation and robustness checks, supported investigation, and assisted with writing, review, and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R104), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available at www.kaggle.com/datasets/mariaren/covid19-healthy-diet-dataset.

Code availability

The code used to generate the results of this study is publicly available at: https://github.com/yasserramadan202025/COVID19-Mortality-Model.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang, Z. H. et al. Predictive value of prognostic nutritional index on COVID-19 severity. Front. Nutr.10.3389/fnut.2020.582736 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gamarra-Morales, Y. et al. Influence of nutritional parameters on the evolution, severity and prognosis of critically Ill patients With COVID-19. Nutrients14 (24), 5363. 10.3390/nu14245363 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.James, P. T. et al. The role of nutrition in COVID-19 susceptibility and severity of disease: A systematic review. J. Nutr.151 (7), 1854–1878. 10.1093/jn/nxab059 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mentella, M. et al. The role of nutrition in the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients13 (4), 1093 10.3390/nu13041093 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Im, J. et al. Nutritional status of patients with COVID-19. Int. J. Infect. Dis.100, 390–393. 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.018 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trajanoska, M. et al. Dietary, comorbidity, and geo-economic data fusion for explainable COVID-19 mortality prediction. Expert Syst. Appl.209, 118377. 10.1016/j.eswa.2022.118377 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sah, S. et al. Covid-19 cases prediction using SARIMAX model by tuning hyperparameter through grid search cross‐validation approach. Expert Syst.10.1111/exsy.13086 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Awal, M. et al. A novel Bayesian optimization-based machine learning framework for COVID-19 detection from inpatient facility data. IEEE Access.9, 10263–10281 10.1109/access.2021.3050852. (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Alali, Y. et al. A proficient approach to forecast COVID-19 spread via optimized dynamic machine learning models. Sci. Rep.10.1038/s41598-022-06218-3 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdullahi, S. et al. Data-Driven AI-Based parameters tuning using grid partition algorithm for predicting Climatic effect on epidemic diseases. IEEE Access.9, 55388–55412. 10.1109/access.2021.3068215 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang, X. & Li, S. Prediction of COVID-19 Using a WOA-BILSTM model. Bioengineering. 10 (8), 883 10.3390/bioengineering10080883 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Deng, X. et al. Building a predictive model to identify clinical indicators for COVID-19 using machine learning method. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput.60 (6), 1763–1774. 10.1007/s11517-022-02568-2 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gumaei, A. et al. Prediction of COVID-19 confirmed cases using gradient boosting regression method. Comput. Mater.66 (1), 315–329 10.32604/cmc.2020.012045 (2020).

- 14.Goel, T. et al. OptCoNet: an optimized convolutional neural network for an automatic diagnosis of COVID-19. Applied intelligence, 51 (3), 1351–1366 10.1007/s10489-020-01904-z (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Sayed, S. et al. COVID-HGS: early severity prediction model of COVID-19 based on hunger game search (HGS) optimization algorithm. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 96, 106515. 10.1016/j.bspc.2024.106515 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Becerra-Sánchez, A. et al. Mortality analysis of patients with COVID-19 in Mexico based on risk factors applying machine learning techniques.Diagnostics12 (6), 1396 10.3390/diagnostics12061396 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Alkhammash, E. H. et al. Application of machine learning to predict COVID-19 spread via an optimized BPSO Model. Biomimetics, 8 (6), 457 10.3390/biomimetics8060457 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Tarek, Z. et al. An optimized model based on deep learning and gated recurrent unit for COVID-19 death Prediction. Biomimetics, 8 (7), 552 10.3390/biomimetics8070552 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Zhang, P. et al. The modified NUTRIC score can be used for nutritional risk assessment as well as prognosis prediction in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Clin. Nutr.40 (2), 534–541. 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.05.051 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao, X. et al. Evaluation of nutrition risk and its association with mortality risk in severely and critically ill COVID-19 patients. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr.45 (1), 32–42. 10.1002/jpen.1953 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamyari, N. et al. Diet, Nutrition, Obesity, and their implications for COVID-19 mortality: development of a marginalized Two-Part model for semicontinuous data. JMIR Public. Health Surveillance. 7 (1), e22717. 10.2196/22717 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ilkowski, J. et al. Nutritional Risk Score (NRS-2002) as a predictor of In-hospital mortality in COVID-19 patients: A retrospective single-center cohort study. Nutrients 17 (7), 1278 10.3390/nu17071278 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.COVID-19 Healthy Diet Dataset. Kaggle, www.kaggle.com/datasets/mariaren/covid19-healthy-diet-dataset (2021).

- 24.Elshewey, A. M. & Osman, A. M. Orthopedic disease classification based on Breadth-first search algorithm. Sci. Rep.14 (1). 10.1038/s41598-024-73559-6 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Elshewey, A. M. et al. Water potability classification based on hybrid stacked model and feature selection. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.10.1007/s11356-025-36120-0 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shams, M. Y. et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on diet prediction and patient health based on support vector machine. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 64–76. 10.1007/978-3-030-69717-4_7 (2021).

- 27.Shams, M. Y. et al. HANA: A healthy artificial nutrition analysis model during COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Biol. Med.135, 104606. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104606 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.García-Ordás, M. Teresa, et al. Evaluation of country dietary habits using machine learning techniques in relation to deaths from COVID-19. Healthcare, 8 (4), 371 10.3390/healthcare8040371 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Elshewey, A. M. et al. Prediction of aerodynamic coefficients based on machine learning models. Model. Earth Syst. Environ.10.1007/s40808-025-02355-6 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaddes, M. et al. Breast cancer classification based on hybrid CNN with LSTM model. Sci. Rep.10.1038/s41598-025-88459-6 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elshewey, A. M. et al. Enhancing heart disease classification based on Greylag Goose optimization algorithm and long Short-term memory. Sci. Rep.10.1038/s41598-024-83592-0 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarek, Z. et al. A snake optimization Algorithm-based feature selection framework for rapid detection of cardiovascular disease in its early stages. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 102, 107417. 10.1016/j.bspc.2024.107417 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elshewey, A. M. et al. Enhancing hydrogen energy consumption prediction based on stacked machine learning model with Shapley additive explanations. Process. Integr. Optim. Sustain.10.1007/s41660-025-00539-2 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 34.El-Kenawy, M. Optimized deep learning model using binary particle swarm optimization for phishing attack detection: A comparative study. Mesopotamian J. Cybersecur.5 (2), 685–703. 10.58496/MJCS/2025/041 (2025). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Awal, M. et al. A novel Bayesian optimization-based machine learning framework for COVID-19 detection from inpatient facility data. IEEE Access.9, 10263–10281 10.1109/access.2021.3050852. (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available at www.kaggle.com/datasets/mariaren/covid19-healthy-diet-dataset.

The code used to generate the results of this study is publicly available at: https://github.com/yasserramadan202025/COVID19-Mortality-Model.