Abstract

Objective

This research aims to analyze the global, regional, and national burden of LE-PAD from 1990 to 2021 through the GBD 2021 database. We also assess the impact of dietary risk factors and use decomposition and frontier analyses to identify key drivers and disparities in disease burden.

Methods

We used data from the GBD 2021 study (covering 204 countries and territories) to analyze LE-PAD-related prevalence, incidence, mortality, and DALYs, and conducted trend analysis and projections via joinpoint regression and autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models. Decomposition analysis evaluated the contributions of population growth, aging, and epidemiological changes, and frontier analysis identified countries with high LE-PAD rates relative to their SDI.

Results

From 1990 to 2021, global LE-PAD prevalence and incidence rose significantly. Females had higher prevalence, and males under 75 had higher mortality. Dietary risk factors like high processed meat and low whole-grain intake were major contributors. Population growth drove the increased burden, somewhat mitigated by epidemiological changes. Frontier analysis showed country disparities, with some high-income countries having relatively high LE-PAD burden.

Conclusion

The growing burden of LE-PAD demands targeted interventions, better healthcare infrastructure, and sustained research. Addressing modifiable risk factors, promoting healthy lifestyles, and conducting effective public health campaigns and education are crucial to reduce its impact.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s41043-025-01094-9.

Keywords: Lower extremity peripheral arterial disease burden, Global burden of disease 2021, Dietary risk factors, Decomposition analysis, Frontier analysis, ARIMA model prediction, Health policy implications

Highlights

Type of research: Global burden analysis of lower extremity peripheral arterial LE-PAD using data from the updated GBD 2021 study.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s41043-025-01094-9.

Take home message

The burden of LE-PAD continues to grow globally, despite declines in age-standardized rates.

Targeted interventions addressing modifiable risk factors, such as diet and smoking, are essential to mitigate the impact of LE-PAD.

Effective public health strategies and improved healthcare infrastructure are urgently needed to address this growing challenge.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s41043-025-01094-9.

Key findings

Global prevalence and incidence of LE-PAD increased significantly from 1990 to 2021, with higher burden in high SDI regions.

Dietary risk factors, such as high intake of processed meat and low consumption of whole grains, were major contributors to the disease burden.

Decomposition analysis showed population growth as the primary driver of increased LE-PAD burden, with mitigating effects from epidemiological changes.

Frontier analysis identified significant disparities, with some high-income countries showing higher LE-PAD burden relative to their SDI.

Projections through 2036 indicate continued growth in LE-PAD burden, highlighting the need for sustained public health efforts.

Table of contents summary

This global burden analysis using the updated GBD 2021 data shows significant increases of disease burden in LE-PAD from 1990 to 2021, with projections indicating continued growth. Targeted interventions addressing modifiable risk factors are essential to mitigate this growing burden.

Introduction

Peripheral arterial disease, commonly known as lower extremity arterial disease (LE-PAD) [1] is defined as vascular occlusion or narrowing in the lower limb arteries [2]. This condition significantly impairs lower extremity function and affects hundreds of millions globally, being the third most common clinical manifestation of atherosclerosis following coronary artery disease and stroke [3]. The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) estimates a 72.50% increase in global LE-PAD prevalence from 1990 to 2019 [4]. Despite its heavy burden, awareness and focus on LE-PAD remain insufficient compared to other cardiovascular diseases. Only about 55% of the disease burden is attributed to identified risk factors such as tobacco use, diabetes, and hypertension across all socio-demographic index (SDI) groups [4].

Dietary risk factors play a pivotal role in LE-PAD’s development and progression. Trials and observational studies indicate that fiber, vitamins, and adherence to a Mediterranean diet can reduce LE-PAD incidence for primary prevention [5]. Conversely, diets high in saturated fats, meat, and deficient in protein, magnesium, or selenium negatively impact LE-PAD. This study will explore dietary risks’ impact on LE-PAD’s burden, providing insights into potential preventive measures [6].

The GBD study adopts a comprehensive approach to estimate disease burden, including integrating multi-source data, using the DisMod-MR model for disease modeling, and applying Bayesian statistical frameworks and Monte Carlo methods to quantify uncertainties. These methods collectively form a systematic analytical framework capable of generating comparable and consistent estimates of disease burden [7, 8]. By utilizing the GBD framework, this study systematically analyzes and compares the prevalence, incidence, mortality, and DALYs of LE-PAD at global, regional, and national levels. The study also includes frontier analysis and offers projections up to 2036, providing a comprehensive, future-oriented overview.

Methods

Research population and data compilation

Our study used GBD 2021 data to analyze LE-PAD’s prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs across 204 countries from 1990 to 2021. Based on the socio-demographic index (SDI), which combines per-capita income, years of schooling, and fertility rate, the 204 countries and regions are categorized into five SDI quintiles: low, low-middle, middle, high-middle, and high SDI regions. Using two criteria of epidemiological similarity and geographical proximity, the globe is further divided into 21 GBD regions, including high-income Asia Pacific, middle Latin America, the Caribbean and so on, which are also simplified into seven super GBD regions like the high-income region [9, 10]. Our analysis included 204 countries and territories, grouped into 21 GBD regions based on geographic proximity and subsequently classified into five categories according to the SDI.

Data analysis

Overview

We assessed the dataset’s structure and estimated numbers and rates for essential metrics, including prevalence, incidence, deaths, and DALYs of LE-PAD at global, regional, and national levels [11]. We analyzed measure variations from 1990 to 2021 across multiple regions for both case numbers and age-standardized rates (ASRs) per 100,000 individuals.

To ensure reliable burden estimation, the GBD study uses a Bayesian statistical framework with the Monte Carlo method to calculate 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs): first, integrate multi-source data and perform stratified modeling via the DisMod-MR 2.1 model to correct data biases; then, conduct 500 random draws per parameter to simulate plausible value ranges (preserving and propagating uncertainties from measurement error, model assumptions, and regional heterogeneity); finally, generate UIs using the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the 500 draws to quantify burden estimate uncertainty [12]. The 95% UI indicates a 95% probability that the true value lies within the interval. The interval width reflects the estimate’s robustness: a wide interval suggests sparse data or significant model uncertainty, often seen in low-income countries, while a narrow one implies sufficient data and a stable model [13].

The Estimated Annual Percentage Change (EAPC) was employed to quantify trends in ASRs, derived from a generalized linear model assuming a Gaussian distribution [14]. When calculating the EAPC, calendar year was set as the explanatory variable X, and the natural logarithm of the age-standardized rate (ln[ASR]) was used as the dependent variable Y to fit the data to the regression line y = a + bx + ε. The EAPC was then calculated using the fitted regression line parameter β with the formula: EAPC = 100 × (exp(β) − 1) [15, 16]. This calculation is valid only when the ASR changes remain stable throughout the observation period. Statistical hypothesis testing was conducted to evaluate the calculated EAPC and exclude the influence of random factors. The hypothesis test for EAPC is equivalent to the hypothesis test for the slope of the fitted line; specifically, if the slope of the line is statistically significant, the EAPC is considered valid. The hypothesis test for EAPC involved a t-test on the slope b of the fitted line: tb = b/sb (where b is the slope of the line and sb is the standard error of slope b), with the degrees of freedom V being the number of calendar years minus 2. Due to the influence of the standard error of slope b on both the slope of the fitted line and the EAPC, the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the EAPC were calculated as described in reference [17, 18].

Relative changes were calculated using the formula: Relative change (%) = [(Value in 2021 - Value in 1990) / Value in 1990] * 100% [11].

Graphs in this section were generated using R software (Version 4.2.3) and JD_GBDR (Version 2.7.4; Jingding Medical Technology Co., Ltd.).

To eliminate the influence of population structure disparities across countries/regions on the results and ensure the comparability of data at global, regional, and national levels, this study accessed and employed the GBD standard population (https://www.healthdata.org/). Constructed based on the age distribution of the world population in 2000 and adopting the World (WHO 2000–2025) Standard [19], the GBD standard population comprises 18 age groups (0–4 years, 5–9 years, …, 95 + years), with weights reflecting the standardized age structure of the global population [20].

Joinpoint regression analysis

The joinpoint regression model, composed of multiple linear statistical models, assesses temporal changes in disease burden. It quantifies illness rate variations via the least squares method, reducing subjectivity from traditional linear trend analyses [21]. By calculating the squared residual error between estimated and actual values, it determines the trend variation’s inflection point. Developed using Joinpoint software (version 5.1.0.0; National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD, USA), this model analyzes temporal data patterns by connecting multiple line segments on a logarithmic scale. To evaluate trends, it calculates the annual percentage change (APC) and average annual percentage changes (AAPCs). AAPCs represent a geometrically weighted average of APCs from the joinpoint trend analysis, with weights based on each period’s length within the timeframe [22]. The calculation methods of joinpoint for AAPC and 95% CI were referenced from the study by Kim et al. [23]. An AAPC number and 95% CI exceeding 0 indicate an upward trend in the ASR, and vice versa. If the AAPC’s 95% CI includes zero, the ASR is deemed stable over time [24].

Relationship between LE-PAD burden and SDI

The socio-demographic index (SDI) is a composite indicator developed by GBD researchers to assess a region’s socio-economic status [25]. It integrates per capita income, educational achievement, and fertility rates into a statistic ranging from 0 to 1 [26]. The correlation between LE-PAD burden and SDI was analyzed using Pearson correlation analysis. Statistical analysis and graphical representation were performed using R version 4.3.3.

Cross-country inequalities analysis

To quantify disparities in LE-PAD burden among countries, we used the slope index of inequality and the concentration index. The slope index of inequality was calculated by regressing country-level against the relative position scale of socio-demographic development [27]. The concentration index was determined by constructing a Lorenz concentration curve and integrating the area beneath it, with values ranging from − 1 to 1 [28]. The slope index measures the absolute burden gap between extreme values of the SDI, while the concentration index dynamically maps burden distribution through Lorenz curves, collectively revealing whether disparities disproportionately affect low-resource populations [29]. Statistical analysis and graphical representation were performed using R version 4.3.3.

Age-period-cohort analysis

Age-period-cohort models dissect the dynamic drivers of disease burden by isolating the independent effects of age, period, and birth cohorts. Age effects mirror the impact of physiological aging on LE-PAD; period effects can capture the immediate influence of public health events; and cohort effects reveal the impact of long-term exposures related to birth cohorts [30]. Age-period-cohort models are widely used in sociology and epidemiology to analyze the dynamic drivers of disease burden by separating the independent effects of age, period, and birth cohorts. This study applied Poisson-distribution-based age-period-cohort models to characterize health outcome trends across these dimensions [31]. To address multicollinearity among age, period, and cohort effects, the Intrinsic Estimator (IE) method was used. By imposing constraint conditions on model parameters, IE stabilizes estimates and mitigates bias from multicollinearity, enabling accurate reflection of each factor’s true effect [32]. The log-linear regression model (log(Yi) = µ + α∗agei + β∗periodi + γ∗cohorti + ε) was employed, with Yi representing LE-PAD prevalence/mortality rates. Following GBD protocols, age groups were defined as 0–4, 5–9, …, 95 + years, and data were aggregated over 5-year intervals. Model fitting used the APC Web Tool (https://analysistools.cancer.gov/apc/) [30]. In this section, JD_GBDR (V2.22, Jingding Medical Technology Co., Ltd.) was used for the drawing of the figures.

Decomposition analysis

Decomposition analysis partitioned burden variations into population growth, aging, and epidemiological changes via counterfactual modeling, which isolates each driver’s independent contribution while accounting for synergistic effects [33]. The specific method is based on Yan Xie et al.‘s approach [34]. Statistical analysis and graphical representation were performed using R version 4.3.3.

Frontier analysis

Frontier analysis quantifies the discrepancy between each country’s actual disease burden and the theoretical optimal value by constructing a “best-performance frontier”-defined as the set of countries with the lowest disease burden at the same SDI. Unlike traditional cross-country inequalities comparisons, this approach identifies countries with disproportionately high burdens within the same SDI category, signaling structural deficiencies in healthcare systems or risk factor management, and advocates for learning from frontier-neighboring countries at comparable SDI levels. By decoupling economic development from disease control capacity, this analysis provides targeted insights for resource allocation and complements limitations of conventional inequality assessments [35]. This approach could pinpoint the leading ones. These leading regions then served as standards and goals for others. For every country and territory, we calculated the ‘effective difference’. This value represented the disparity between the existing disease burden and the potential one, with adjustments made according to the SDI [34].

Predictive analysis

To forecast future trends in LE-PAD burden, we employed the autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model. We selected the ARIMA model for forecasting because it can model long-term trends of non-stationary time series—eliminating non-stationarity via differencing (d) and capturing linear dependencies through autoregressive (p) and moving average (q) terms. Parameter selection followed a data-driven approach: after confirming stationarity via the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test, the auto.arima algorithm optimized (p, d, q) using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to avoid subjective bias. ARIMA leverages time-dependent autocorrelation in historical data for future forecasting, offering interpretability and computational efficiency without requiring large labeled datasets, unlike machine learning models. Compared to static regression, its dynamic capture of serial autocorrelation enhances accuracy [36, 37]. The calculation of ARIMA prediction and its 95%CI referred to Forecasting: Principles and Practice (2nd ed) [38]. Predictive analyses were conducted using R version 4.3.3.

Dietary risk factors analysis

We assessed the impact of dietary factors on LE-PAD burden using data from the GBD 2021 database. The analysis focused on seven dietary risks and compared observed risk factor levels to a theoretical minimum risk exposure level. Analyses were performed using R version 4.3.3.

Results

Overview of the global burden

Results of the trend analysis for LE-PAD

From 1990 to 2021, global LE-PAD prevalence increased significantly (from 56.29 million to 113.71 million cases), while the age-standardized prevalence rate (ASPR) decreased from 1513.05 to 1326.45 per 100,000-a 12.33% reduction over the study period (Supplementary materials Table. 1). The incidence case number increased by 96.86%, while the age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) declined by 11.42% (Supplementary materials Table. 2). Similarly, mortality due to LE-PAD rose by 72.79%, but the age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR) decreased significantly by 35.89% (Supplementary materials Table. 3). The global DALYs increased by 70.68%, although the age-standardized DALYs rate (ASDR) declined by 30.12% (Supplementary materials Table. 4). Comprehensive analyses of prevalence, incidence, mortality, and DALYs across 204 countries and territories are illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2 and Supplementary Materials Tables 5–8 and Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Fig. 1.

The case number of prevalence in 2021

Fig. 2.

The ASR of prevalence in 2021

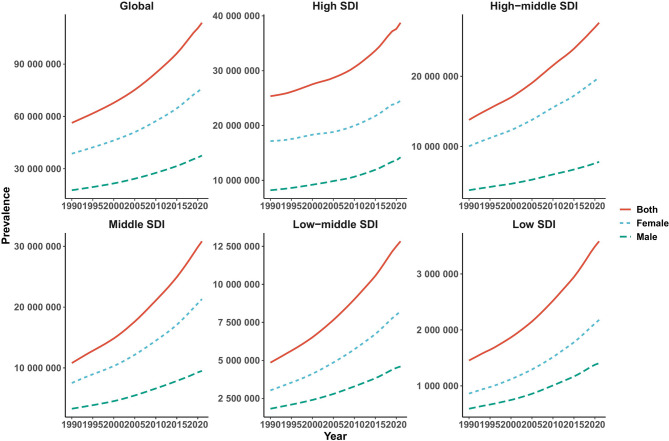

Fig. 3.

The trends of case number in prevalence (A), incidence (B), deaths (C), and DALYs (D) for LE-PAD categorized by global and 5 SDI regions from 1990 to 2021

Fig. 4.

The trends of case number and ASR in prevalence for LE-PAD across different genders, female and male, by age groups ranging from under 5 years to 95 + years in global

Fig. 5.

The joinpoint analysis of ASR in prevalence for both gender

Results of the trends by year, sex and age for LE-PAD

Over the past 30 years, the absolute number of LE-PAD cases has risen yearly globally and in all 5 SDI regions (Fig. 4). Detailed analyses across global, 5 SDI regions, and 21 GBD regions are in Supplementary Materials Fig. 6. The ASRs for LE-PAD have generally declined globally, though trends vary regionally (Supplementary Materials Fig. 7).

Females have higher prevalence, incidence, and DALYs, while males have higher mortality rates and more deaths before 75 (Fig. 38). The 60–74 age group has the highest prevalence, while the main age categories for incidence, mortality, and DALYs are 60–74, 80–89, and 65–84, respectively. Detailed analyses across the 5 SDI regions and 21 GBD regions, by age and gender, are in Supplementary Materials Fig. 9–34.

Results of the joinpoint regression analysis for LE-PAD

Joinpoint regression analysis identified significant trends and inflection points in LE-PAD’s ASRs from 1990 to 2021, with consistent trends between genders: prevalence ASR declined rapidly from 1990 to 2006 (APC = -0.57%, P < 0.05), slowed from 2006 to 2015 (APC = -0.47%, P < 0.05), and stabilized (APC = -0.01%, P > 0.05) (Fig. 5and Supplementary Materials Fig. 35); incidence ASR declined marginally from 1990 to 2007 (APC = -0.50%, P < 0.05), slowed from 2007 to 2015 (APC = -0.39%, P < 0.05), and stabilized from 2015 to 2021 (APC = -0.11%, P > 0.05) (Fig. 5and Supplementary Materials Fig. 35); mortality ASR fluctuated from 1990 to 2000, then declined (Supplementary Materials Fig. 36A-C); DALYs ASR fluctuated from 1990 to 2000, then declined, with significant APC variations (Supplementary Materials Fig. 36D-F).

Results of the relationship between LE-PAD burden and SDI for LE-PAD

The relationship between LE-PAD burden and SDI shows varied patterns: prevalence rises with SDI up to near 0.60, peaks near 0.80, then declines (Supplementary Materials Fig. 37A); incidence increases with SDI up to near 0.65, then declines (Supplementary Materials Fig. 37B); mortality generally falls with rising SDI, but has a temporary rise around SDI 0.65–0.75 (Supplementary Materials Fig. 33C); DALYs follow mortality’s trend, with a transient rise around SDI 0.65–0.75 (Supplementary Materials Fig. 37D). These findings stress the importance of grasping the nuanced socio-economic development and LE-PAD burden relationship. Higher SDI generally means better health outcomes, but disease burden may temporarily rise during transitions. This highlights the need for targeted public health interventions in rapidly changing regions. The relationship across 204 countries and territories is in Supplementary Materials Fig.

Cross-country inequality analysis for LE-PAD

Cross-country inequality analysis showed significant LE-PAD burden disparities across SDI levels, with higher SDI countries having greater absolute and relative inequalities in prevalence than lower SDI regions (Supplementary Materials Fig. 39). In 1990, the slope index of inequality was 1117.76 per 100,000, widening to 2293.29 by 2021 (Supplementary Materials Fig. 39A). The concentration index analysis indicated a more uniform distribution of LE-PAD prevalence over time via the Lorenz concentration curve (Supplementary Materials Fig. B). Similar disparity trends were found for incidence, deaths and DALYs (Supplementary Materials Figs. 40–42).

Results of the age-period-cohort analysis for LE-PAD

Prevalence emerged in the 40–44 years age group and increased significantly with advancing age (Supplementary Fig. Fig. 43A). Within each age group, prevalence exhibited a slight downward trend over time (Supplementary Fig. 43B). Compared with earlier-born cohorts, later-born cohorts had a marginally lower prevalence when they reached the same age (Supplementary Fig. 43C). The age-period-cohort analysis results of ASIR, ASMR, and ASDR for LE-PAD are in Supplementary Materials Fig. 44–46.

Results of the decomposition analysis for LE-PAD

Decomposition analysis quantified contributions of population growth, aging, and epidemiological changes to LE-PAD burden variations from 1990 to 2021: prevalence mainly rose due to population growth (Supplementary Materials Fig.47A); incidence was chiefly determined by population growth and aging, with epidemiological changes dampening the increase (Supplementary Materials Fig.47B); mortality’s increase from population growth and aging was offset by epidemiological improvements (Supplementary Materials Fig. 47C); DALYs were chiefly contributed by aging and population growth, yet epidemiological changes reduced the overall burden (Supplementary Materials Fig. 47D). These findings highlight the complex interaction between demographic and epidemiological factors in shaping LE-PAD burden. The decomposition analysis results for different sex and 21GBD regions are in Supplementary Materials Fig. 48–52.

Results of the frontier analysis for LE-PAD

Frontier analysis revealed SDI’s impact on LE-PAD’s ASRs: prevalence and incidence ASRs decline with higher SDI (Supplementary materials Figs. 53 A, 53 C); mortality and DALYs ASRs show similar downward trends (Supplementary Materials Figs. 54 A, 54 C). Notably, these ASRs (prevalence, incidence, mortality, DALYs) show distinct temporal trends by SDI level: they mostly decrease over time in low SDI regions but increase in high SDI regions. For example, in 2021, high SDI countries like the U.S. and Denmark had higher-than-expected prevalence and incidence, while low SDI countries like Niger and Somalia were closer to the frontier (Supplementary materials Figs. 53 B, 53 D). Regarding mortality rates and DALYs, low SDI countries such as Somalia are close to the frontier line, whereas high SDI countries like Barbados and Belarus are far from it (Supplementary materials Figs.54 B, 54 D).

Results of the predictive analysis for LE-PAD

ARIMA model projections for LE-PAD’s ASRs from 2022 to 2036 show: ASPR is set to rise slightly, mainly due to male population increase, while female prevalence stays stable (Supplementary materials Fig. 55 A and 55 B); ASIR will also increase slightly, with male incidence up and female incidence slightly down (Supplementary materials Fig. 55 C and 55 D); in contrast, mortality and DALYs ASRs are expected to decline for both genders (Supplementary materials Fig. ).

Results of the dietary risk factors for LE-PAD

Supplementary materials Fig. 57 illustrates the contribution of seven dietary risk factors to age-standardized deaths for global, five SDI regions, and 21 GBD regions in 2021. A diet high in processed meat, a diet low in whole grains, and a diet high in red meat were identified as the major contributors to the burden of LE-PAD. Notably, there was no significant difference observed between genders, indicating that these dietary risk factors affect both males and females similarly. This phenomenon was also consistent with the trends observed in DALYs (Supplementary materials Fig. 58).

Discussion

Global burden and future trends of LE-PAD

Our study comprehensively analyzed the global LE-PAD burden from 1990 to 2021, finding significant rises in prevalence, incidence, mortality, and DALYs despite declines in ASRs. These results match previous studies on cardiovascular diseases’ growing burden in aging populations [4]. For instance, a study using GBD 2019 data reported a 72.50% increase in global LE-PAD prevalence from 1990 to 2019 [4]. Our research extends these findings via detailed 2036 projections, frontier, decomposition analyses, and dietary risk factor assessments, collectively emphasizing LE-PAD’s future burden and the need for sustained public health efforts, healthcare planning, and targeted interventions.

Our analysis revealed distinct LE-PAD burden patterns across age groups and genders. Females had higher prevalence and incidence rates than males, with the highest prevalence in the 60–74 years age group [4]. This aligns with prior studies suggesting women are more likely to have asymptomatic or atypical LE-PAD symptoms, resulting in higher prevalence but possible underdiagnosis [4]. However, males had higher mortality rates than females before 75, while females had higher rates after 75. This gender disparity may stem from differences in risk factor exposure and biological factors. For example, smoking and heavy alcohol consumption, major LE-PAD risk factors, are more common in males, contributing to higher mortality rates. In contrast, females often have higher diabetes and hypertension rates, explaining their higher prevalence and incidence [4]. Additionally, estrogen in females may protect against cardiovascular events, leading to lower mortality rates in younger age groups [39]. However, the slowdown in the mortality rate and DALYs rate of LE-PAD around 2020 may be associated with the prevalence of COVID-19 [40].

Socio-Demographic disparities and inequalities

The relationship between LE-PAD burden and SDI is complex, with initial increases and subsequent declines at higher SDI levels, indicating improved socio-economic conditions may first worsen LE-PAD burden but further development can enhance health outcomes [4]. However, significant cross-country inequalities exist, with higher prevalence and incidence rates in high SDI countries, stressing the need for equitable healthcare policies addressing socio-economic factors and ensuring preventive care access [41]. Our findings contrast with previous studies assuming a linear SDI-disease burden relationship, highlighting the need for tailored interventions in middle-income countries with the highest burden [4].

Role of dietary risk factors

Our study identified key dietary risk factors for LE-PAD: high processed meat and red meat intake, and low whole grain consumption, consistent with global trends linking unhealthy diets to cardiovascular diseases [42]. Processed meats-high in sodium, saturated fats, and preservatives-increase cardiovascular disease risk (including LE-PAD) [6], while low intake of whole grains (rich in protective fiber, vitamins, and minerals) is associated with higher LE-PAD rates (due to insufficient essential nutrients) [43]. Whole grains are rich in dietary fiber, vitamins, and minerals, which have protective effects against cardiovascular diseases. Low intake of whole grains is associated with higher rates of LE-PAD due to the lack of these essential nutrients [43]. Increasing the consumption of whole grains has been shown to reduce cardiovascular risk factors [44]. Red meat, a significant source of saturated fats and cholesterol, contributes to atherosclerosis, a key LE-PAD cause [6]. Replacing red meat with plant-based proteins or leaner protein sources like fish can reduce cardiovascular disease risk [44]. Public health strategies should promote healthier dietary patterns like the Mediterranean diet, rich in fiber, fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, shown to reduce LE-PAD incidence [45]. Our study extends previous research by detailing dietary risks across regions and SDI groups, revealing their universal significance and underscoring the need for global dietary interventions, especially in high-income regions with prevalent unhealthy patterns.

Decomposition analysis insights

Our decomposition analysis found that population growth was the main driver of the increased LE-PAD burden, while epidemiological changes had mitigating effects. Population growth significantly increased the prevalence and incidence of LE-PAD by expanding the at-risk population. However, healthcare improvements, particularly in managing hypertension and diabetes, reduced LE-PAD’s per-capita burden despite ongoing population growth. Aging also had a complex impact, as healthcare advances improved outcomes for the elderly, reducing mortality rates. Nevertheless, the rising prevalence of LE-PAD among seniors still highlights the need for enhanced preventive measures and early detection [46].

Frontier analysis and country-level disparities

The frontier analysis sheds light on the intricate relationship between SDI and LE-PAD’s ASRs. Generally, prevalence and incidence ASRs decrease as SDI increases, with mortality and DALYs ASRs following a similar downward trend. This implies that higher SDI, reflecting better socio-economic conditions, is associated with lower LE-PAD burden. However, the temporal trends of these metrics show notable differences across SDI levels. In low SDI regions, these indicators mostly decline over time, possibly due to gradually improving healthcare access and disease management. In contrast, high SDI regions have seen an increase in these metrics over time, perhaps due to lifestyle changes such as sedentary behavior and unhealthy diets, which may offset the benefits of advanced healthcare systems [45]. In 2021, some high SDI countries like the United States of America and Denmark had higher prevalence and incidence rates than expected. This (higher prevalence/incidence in high SDI countries) may stem from higher rates of obesity, smoking, and other cardiovascular risk factors. In contrast, low SDI countries like Niger and Somalia were closer to the frontier for prevalence and incidence-meaning their observed rates are near the theoretical minimum for their SDI levels. When it comes to mortality rates and DALYs, low SDI countries like Somalia are near the frontier line. This might suggest that despite limited resources, these countries have relatively efficient approaches to managing LE-PAD mortality. Conversely, high SDI countries like Barbados and Belarus are farther from the frontier line for mortality and DALYs. This could indicate that these countries may have room for improvement in healthcare efficiency or disease management strategies. The findings highlight that while SDI is a crucial determinant of health outcomes, it is not the sole factor. Countries need to tailor their healthcare policies to address specific risk factors and healthcare system inefficiencies. High SDI countries with higher-than-expected LE-PAD rates might benefit from targeted interventions focusing on modifiable risk factors like smoking cessation, diabetes management, and dietary improvements. Meanwhile, low SDI countries might need to strengthen their healthcare systems and disease surveillance to approach the frontier and achieve better health outcomes relative to their SDI levels.

Policy implications and recommendations

Our analysis of LE-PAD’s global burden and risk factors yields these policy recommendations:

Enhanced public awareness and screening

Public health campaigns should focus on educating the population about LE-PAD symptoms, risk factors, and the importance of early screening, particularly in high-burden, low-awareness regions. Screening programs should utilize the Ankle-Brachial Index to detect asymptomatic cases, especially among high-risk groups such as individuals with diabetes and hypertension [47].

Targeted interventions for high-risk populations

Regions with high LE-PAD burden should prioritize interventions targeting modifiable risk factors such as smoking cessation, diabetes management, and hypertension control. Tailored programs for high-risk age groups (e.g., 60–74 years) can significantly reduce the incidence and progression of LE-PAD. Interventions should also address gender-specific risk factors, such as smoking among males and diabetes among females [47].

Promotion of healthy diets

Policymakers should implement policies that promote healthier dietary habits, such as subsidizing whole grains, fruits, and vegetables, and taxing processed foods high in sodium, sugar, and saturated fats. Public health initiatives should educate the population about the benefits of a balanced diet in preventing cardiovascular diseases, such as the Mediterranean [48] or DASH [49] diets. This is particularly important given the significant contribution of dietary factors such as high intake of processed meat and low consumption of whole grains to the burden of LE-PAD [47].

Strengthening healthcare infrastructure

The increasing burden of LE-PAD necessitates robust healthcare infrastructure capable of providing comprehensive diagnostic and treatment services. This includes expanding access to specialized vascular care, promoting multidisciplinary approaches to patient management, and ensuring the availability of advanced diagnostic tools and treatments. Targeted interventions for LE-PAD could integrate advanced technologies such as machine learning and artificial intelligence [50], novel CO2 angiography technique [51] and new drugs such as Semaglutide [52]). Ensuring regular screenings and early intervention can significantly reduce the progression of LE-PAD [53].

Research and surveillance

Continued monitoring and research on LE-PAD epidemiology are essential for understanding future trends and identifying emerging risk factors. Investment in research to explore the impact of novel risk factors and interventions can inform evidence-based policy decisions. This includes investigating the impact of dietary patterns, lifestyle changes, and socioeconomic factors on LE-PAD [42].

Addressing gender and age-specific needs

Interventions should be tailored to address gender-specific risk factors. For males, focus on smoking cessation programs and hypertension management. For females, emphasize early screening for diabetes and hypertension, especially in older age groups (post-75 years), to mitigate the long-term burden of LE-PAD [42].

Resource allocation based on regional differences

Our study shows that in high SDI countries like the US and Denmark, the prevalence and incidence of LE-PAD are much higher than in “best-performing frontier” nations with the same SDI level. This finding suggests that some of these high-income countries may not be managing risk factors well. To solve this, these countries need to strengthen the control of modifiable risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, and diabetes to reduce the burden of LE-PAD. Some countries with high SDI but unusually high disease mortality and DALYs, such as Barbados and Belarus, may have inefficient healthcare systems. These countries need to optimize their cardiovascular disease screening systems by promoting screening, such as ankle-brachial index, for early identification and intervention in asymptomatic patients [54] and learning the latest treatments and management strategies.

Balancing resource allocation with population structure and medical needs

Decomposition analysis shows that population growth is the main driver of the increasing LE-PAD burden, but epidemiological changes have partly offset this trend. At the same time, aging has significantly increased the incidence, mortality, and DALYs of LE-PAD. In light of this, we suggest that in low-and middle-income regions with rapid population growth, such as South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, priority should be given to allocating specialized vascular surgery medical resources and strengthening the training of primary care physicians in early LE-PAD diagnostic techniques such as Ankle-Brachial Index measurement. In high-income countries with severe aging populations, such as Japan and European nations, investment in home care services and remote monitoring devices should be increased to reduce hospitalization rates and complication risks for elderly patients.

Cross-national health equity intervention strategies

Cross-country inequality analysis shows that the LE-PAD burden gap between the highest-and lowest-SDI regions continues to widen. To address this challenge, the following measures can be taken at the cross-national level: promote the establishment of “health partnerships” between high SDI and low SDI countries through international organizations such as the WHO. High SDI countries can transfer early diagnostic and therapeutic technologies for LE-PAD to low SDI regions, which can provide local epidemiological data to support global disease burden analysis. Meanwhile, with the financial support of international organizations, the chronic disease prevention and control network can be improved. In addition, a global monitoring system needs to be established to dynamically coordinate resource allocation based on real-time early warning data, focusing on regions with rapidly growing burdens or weak prevention and control capabilities, in order to reduce health disparities between regions with different levels of social development.

Limitations and future research

Our study offers insights into the global LE-PAD burden and its risk factors, yet has limitations. The analysis uses GBD data, which may be incomplete or inaccurate, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Also, the GBD may not fully show the link between dietary patterns and LE-PAD, requiring more research [11].

Future research directions

Future work should enhance data collection-particularly in low- and middle-income countries-to better estimate LE-PAD metrics and conduct longitudinal research to understand disease progression. It should also explore how dietary changes and lifestyle factors influence LE-PAD risk through mechanistic studies, including their biological impacts and intervention effectiveness, while investigating emerging risk factors like air pollution and genetic interactions [55]. Additionally, developing predictive models and biomarker-based strategies for personalized interventions is critical, such as applying machine learning and bioinformatics to identify high-risk individuals and guide treatments. For example, recent studies show machine learning algorithms can build LE-PAD subtype prediction models using clinical data and neutrophil-related biomarkers [55, 56]. Research should also evaluate the cost-effectiveness of healthcare interventions, the potential of telehealth solutions, and address global health equity through cross-country collaborations and policy impact studies. Public health campaigns should target modifiable risks like poor diets, using effective communication to boost awareness and adherence [55]. Finally, with the aging population, developing elderly-specific interventions is essential for improving LE-PAD management.

Conclusion

Our study shows that LE-PAD significantly impacts global public health. To reduce its burden, we must address the modifiable risk factors of LE-PAD and strengthen healthcare systems globally. Advanced technologies can help identify high-risk individuals and guide treatments. Effective public health campaigns and education programs are also crucial for improving awareness and adherence to preventive measures. Combining these strategies with ongoing research and surveillance is essential for tackling LE-PAD’s growing burden and improving cardiovascular health globally.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) for facilitating open access. We especially thank for the technical support for the JD_GBDR software.

Author contributions

Yujun He: Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Supervision, Project administration. Miao Zhou: Writing-review & editing, Investigation, Data curation, Validation. Jie Tang: Writing-review & editing, Formal analysis, Supervision. Yaling Zheng: Writing-review & editing, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. Jianying Chen: Writing-review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation. Bowen Xing: Writing-review & editing, Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization. Dan Li: Writing-review & editing, Investigation, Validation. Mengya Liang: Writing-review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology. Weiwei Tang: Writing-review & editing, Data curation, Visualization. Xiaojun Li: Writing-review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Xiaoyi Wang: Writing-review & editing, Investigation, Data curation.

Funding

This study is supported by (1) 2026 Annual General Program of Zhejiang Provincial Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project (No. 767). (2) General Project of Scientific Research Program of Hunan Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No: B2024153). (3) The third round of Taizhou Traditional Chinese Medicine (Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine) key (supported) disciplines (No: Tai Wei Fa [2020] 52).

Data availability

The datasets utilized in this investigation are accessible in open repositories. The repository names and accession numbers are provided below: All data may be accessed via the IHME website (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Generative AI disclosure

In revision this manuscript, artificial intelligence (AI) tools were utilized solely for language-related tasks, including translating portions of draft text and refining linguistic expression to enhance clarity and readability. AI did not participate in any substantive aspects of the research, such as study design, data collection, statistical analysis, interpretation of results, or formulation of conclusions. All scientific content and intellectual contributions remain the sole responsibility of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yujun He, Miao Zhou and Jie Tang contribute equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xiaojun Li, Email: lixj@enzemed.com.

Xiaoyi Wang, Email: 984437045@qq.com.

References

- 1.Gong W, Shen S, Shi X. Secular trends in the epidemiologic patterns of peripheral artery disease and risk factors in China from 1990 to 2019: findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:973592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ying AF, Tang TY, Jin A, Chong TT, Hausenloy DJ, Koh W-P. Diabetes and other vascular risk factors in association with the risk of lower extremity amputation in chronic limb-threatening ischemia: a prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porras CP, Teraa M, Bots ML, de Boer AR, Peters SAE, van Doorn S, et al. The frequency of primary healthcare contacts preceding the diagnosis of Lower-Extremity arterial disease: do women consult general practice differently?? J Clin Med. 2022;11:3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eid MA, Mehta K, Barnes JA, Wanken Z, Columbo JA, Stone DH, et al. The global burden of peripheral artery disease. J Vasc Surg. 2023;77:1119–e11261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zúnica-García S, Javier Blanquer-Gregori JF, Sánchez-Ortiga R, Chicharro-Luna E, Jiménez-Trujillo MI. Association between mediterranean diet adherence and peripheral artery disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus: an observational study. J Diabetes Complications. 2024;38:108871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cecchini AL, Biscetti F, Rando MM, Nardella E, Pecorini G, Eraso LH, et al. Dietary risk factors and eating behaviors in peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:10814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Z, Xia F, Lin R. Global burden of cancer and associated risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1980–2021: a systematic analysis for the GBD 2021. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang X, Lyu Y, Li J, Li Y, Chi C. Global, regional, and National burden of preterm birth, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2021. eClinicalMedicine. 2024;76:102840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang X, Fang Y, Chen H, Zhang T, Yin X, Man J, et al. Global, regional and National burden of anxiety disorders from 1990 to 2019: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30:e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du M, Liu M, Liu J. Global, regional, and National disease burden and attributable risk factors of HIV/AIDS in older adults aged 70 years and above: a trend analysis based on the global burden of disease study 2019. Epidemiol Infect. 2023;152:e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang F, Ma B, Ma Q, Liu X. Global, regional, and National burden of inguinal, femoral, and abdominal hernias: a systematic analysis of prevalence, incidence, deaths, and dalys with projections to 2030. Int J Surg. 2024;110:1951–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C, Wang Y, Liu M, Ma C, Ma C, Wang J, et al. Global, regional, and National burden and trends of tension-type headache among adolescents and young adults (15–39 years) from 1990 to 2021: findings from the global burden of disease study 2021. Sci Rep. 2025;15:18254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403:2133–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li L-B, Wang L-Y, Chen D-M, Liu Y-X, Zhang Y-H, Song W-X, et al. A systematic analysis of the global and regional burden of colon and rectum cancer and the difference between early- and late-onset CRC from 1990 to 2019. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1102673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang D, Liu S, Li Z, Wang R. Global, regional and National burden of gastroesophageal reflux disease, 1990–2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. Ann Med. 2022;54:1372–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang C-Y, Han K, Yang F, Yin S-Y, Zhang L, Liang B-Y, et al. Global, regional, and National prevalence of hearing loss from 1990 to 2019: A trend and health inequality analyses based on the global burden of disease study 2019. Ageing Res Rev. 2023;92:102124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qin Y, Tong X, Fan J, Liu Z, Zhao R, Zhang T, et al. Global burden and trends in incidence, mortality, and disability of stomach cancer from 1990 to 2017. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2021;12:e00406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang R, Li F. Comparison of estimated annual percentage change with average growth rate in public health applications. Chin J Health Stat. 2015;328–9.

- 19.World (WHO 2000–. 2025) Standard - Standard Populations - SEER Datasets. SEER. [cited 2025 May 29]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/stdpopulations/world.who.html

- 20.World Health Organization. WHO methods and data sources for global burden of disease estimates 2000–2019. [cited 2025 May 29]. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/gho-documents/global-health-estimates/ghe2019_daly-methods.pdf

- 21.Zhang Y, Liu J, Han X, Jiang H, Zhang L, Hu J, et al. Long-term trends in the burden of inflammatory bowel disease in China over three decades: A joinpoint regression and age-period-cohort analysis based on GBD 2019. Front Public Health. 2022;10:994619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19:335–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim H-J, Luo J, Chen H-S, Green D, Buckman D, Byrne J, et al. Improved confidence interval for average annual percent change in trend analysis. Stat Med. 2017;36:3059–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du M, Chen W, Liu K, Wang L, Hu Y, Mao Y, et al. The global burden of leukemia and its attributable factors in 204 countries and territories: findings from the global burden of disease 2019 study and projections to 2030. J Oncol. 2022;2022:1612702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.GBD 2021 Suicide Collaborators. Global, regional, and National burden of suicide, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Public Health. 2025;10:e189–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu Y, Shang Z, Zhang W, Hu X, Shen R, Zhang K, et al. Global, regional, and National burden of spinal cord injury from 1990 to 2021 and projections for 2050: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease 2021 study. Ageing Res Rev. 2024;103:102598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Heath Organization. Handbook on health inequality monitoring with a special focus on low- and middle-income countries. 2023 [cited 2024 Oct 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241548632

- 28.Cao F, He Y-S, Wang Y, Zha C-K, Lu J-M, Tao L-M, et al. Global burden and cross-country inequalities in autoimmune diseases from 1990 to 2019. Autoimmun Rev. 2023;22:103326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu B, Feng J, Wang Y, Hou L, Fan Y. Transnational inequities in cardiovascular diseases from 1990 to 2019: exploration based on the global burden of disease study 2019. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1322574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Y. Social inequalities in happiness in the united states, 1972 to 2004: an Age-Period-Cohort analysis. Am Sociol Rev. 2008;73:204–26. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, Schulhofer-Wohl S, Fu WJ, Land KC. The intrinsic estimator for Age‐Period‐Cohort analysis: what it is and how to use it. Am J Sociol. 2008;113:1697–736. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo L. Assessing validity and application scope of the intrinsic estimator approach to the age-period-cohort problem. Demography. 2013;50:1945–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Z, Wu C, Zhang B, Sun H, Liu W, Yang Y, et al. Global, regional and National burdens of alcoholic cardiomyopathy among the working-age population, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis. J Health Popul Nutr. 2025;44:170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xie Y, Bowe B, Mokdad AH, Xian H, Yan Y, Li T, et al. Analysis of the global burden of disease study highlights the global, regional, and National trends of chronic kidney disease epidemiology from 1990 to 2016. Kidney Int. 2018;94:567–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu Q, Wang L, Chen Q, Wang Z. The global, regional, and National burdens of maternal sepsis and other maternal infections and trends from 1990 to 2021 and future trend predictions: results from the global burden of disease study 2021. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2025;25:285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen HV, Naeem MA, Wichitaksorn N, Pears R. A smart system for short-term price prediction using time series models. Comput Electr Eng. 2019;76:339–52. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y, Ning Y, Shen B, Shi Y, Song N, Fang Y, et al. Temporal trends in prevalence and mortality for chronic kidney disease in China from 1990 to 2019: an analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. Clin Kidney J. 2022;16:312–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.8.8. Forecasting | Forecasting: Principles and Practice (2nd ed). [cited 2025 May 29]. Available from: https://otexts.com/fpp2/arima-forecasting.html

- 39.Li Z, Yang Y, Wang X, Yang N, He L, Wang J, et al. Comparative analysis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease burden between ages 20–54 and over 55 years: insights from the global burden of disease study 2019. BMC Med. 2024;22:303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smolderen KG, Lee M, Arora T, Simonov M, Mena-Hurtado C. Peripheral artery disease and COVID-19 outcomes: insights from the Yale DOM-CovX registry. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2022;47:101007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norgren L. Peripheral artery disease: a global need for detection, prevention, and treatment. Lancet Global Health. 2023;11:e1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.You Y, Wang Z, Yin Z, Bao Q, Lei S, Yu J, et al. Global disease burden and its attributable risk factors of peripheral arterial disease. Sci Rep. 2023;13:19898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen W, Zhang S, Hu X, Chen F, Li D. A review of healthy dietary choices for cardiovascular disease: from individual nutrients and foods to dietary patterns. Nutrients. 2023;15:4898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klink U, Härtling V, Schüz B. Perspectives on healthy eating of adult populations in High-Income countries: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Int J Behav Med. 2024;31:923–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blinc A, Paraskevas KI, Stanek A, Jawien A, Antignani PL, Mansilha A, et al. Diet and exercise in relation to lower extremity artery disease. Int Angiol. 2024;43:458–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rammos C, Kontogiannis A, Mahabadi AA, Steinmetz M, Messiha D, Lortz J, et al. Risk stratification and mortality prediction in octo- and nonagenarians with peripheral artery disease: a retrospective analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2021;21:370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.King RW, Canonico ME, Bonaca MP, Hess CN. Management of peripheral arterial disease: lifestyle modifications and medical therapies. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiography Interventions. 2022;1:100513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.D’Alessandro C, Giannese D, Panichi V, Cupisti A. Mediterranean dietary pattern adjusted for CKD patients: the MedRen diet. Nutrients. 2023;15:1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mozaffari H, Ajabshir S, Alizadeh S. Dietary approaches to stop hypertension and risk of chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin Nutr. 2020;39:2035–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flores AM, Demsas F, Leeper NJ, Ross EG. Leveraging machine learning and artificial intelligence to improve peripheral artery disease detection, treatment, and outcomes. Circul Res. 2021;128:1833–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Afsharirad A, Javankiani S, Noparast M. Comparing the accuracy and safety of automated CO2 angiography to iodine angiography in peripheral arterial disease with chronic limb ischemia: a prospective cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2024;87:527–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bonaca MP, Catarig A-M, Houlind K, Ludvik B, Nordanstig J, Ramesh CK, et al. Semaglutide and walking capacity in people with symptomatic peripheral artery disease and type 2 diabetes (STRIDE): a phase 3b, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2025;405:1580–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patel RAG, Sakhuja R, White CJ. The medical and endovascular treatment of PAD: A review of the guidelines and pivotal clinical trials. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2020;45:100402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horstick G, Messner L, Grundmann A, Yalcin S, Weisser G, Espinola-Klein C. Tissue optical perfusion pressure: a simplified, more reliable, and faster assessment of pedal microcirculation in peripheral artery disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;319:H1208–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang L, Ma Y, Li Q, Long Z, Zhang J, Zhang Z, et al. Construction of a novel lower-extremity peripheral artery disease subtype prediction model using unsupervised machine learning and neutrophil-related biomarkers. Heliyon. 2024;10:e24189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shen M, Zhang Y, Zhan R, Du T, Shen P, Lu X et al. Predicting the risk of cardiovascular disease in adults exposed to heavy metals: Interpretable machine learning. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 23];290. Available from: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.117570 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets utilized in this investigation are accessible in open repositories. The repository names and accession numbers are provided below: All data may be accessed via the IHME website (https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/).