Abstract

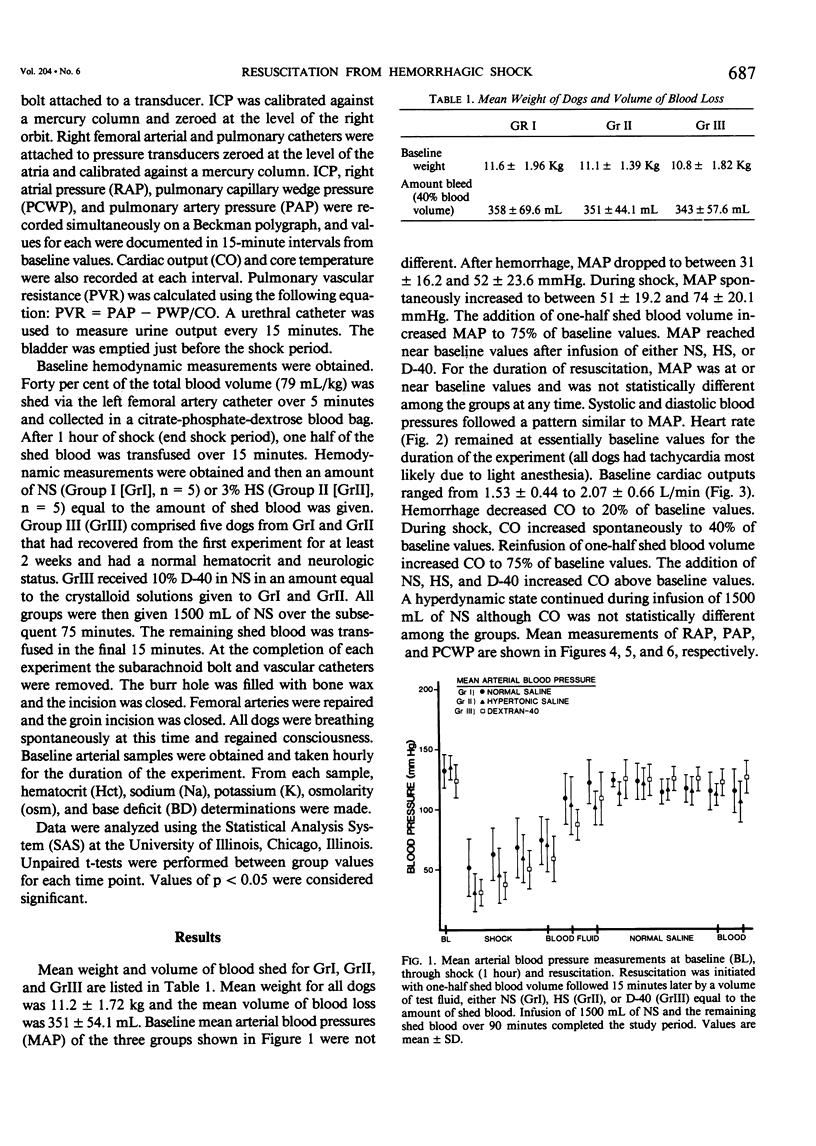

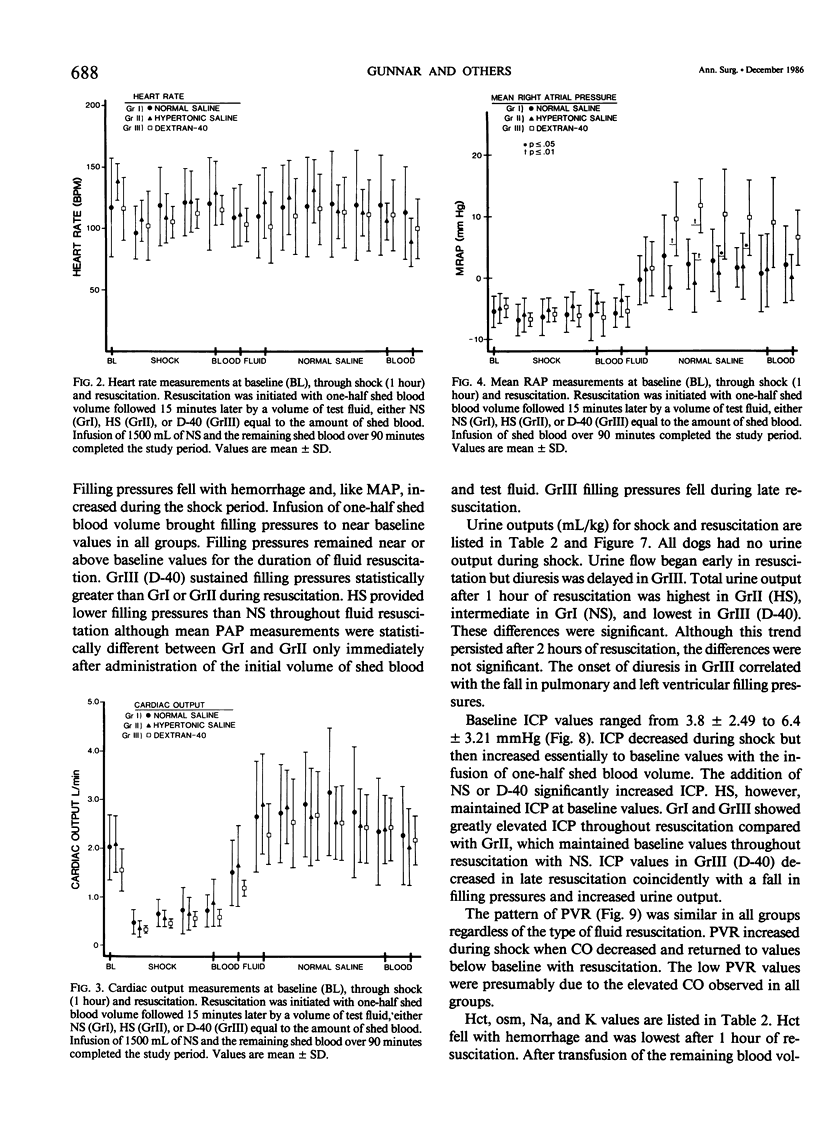

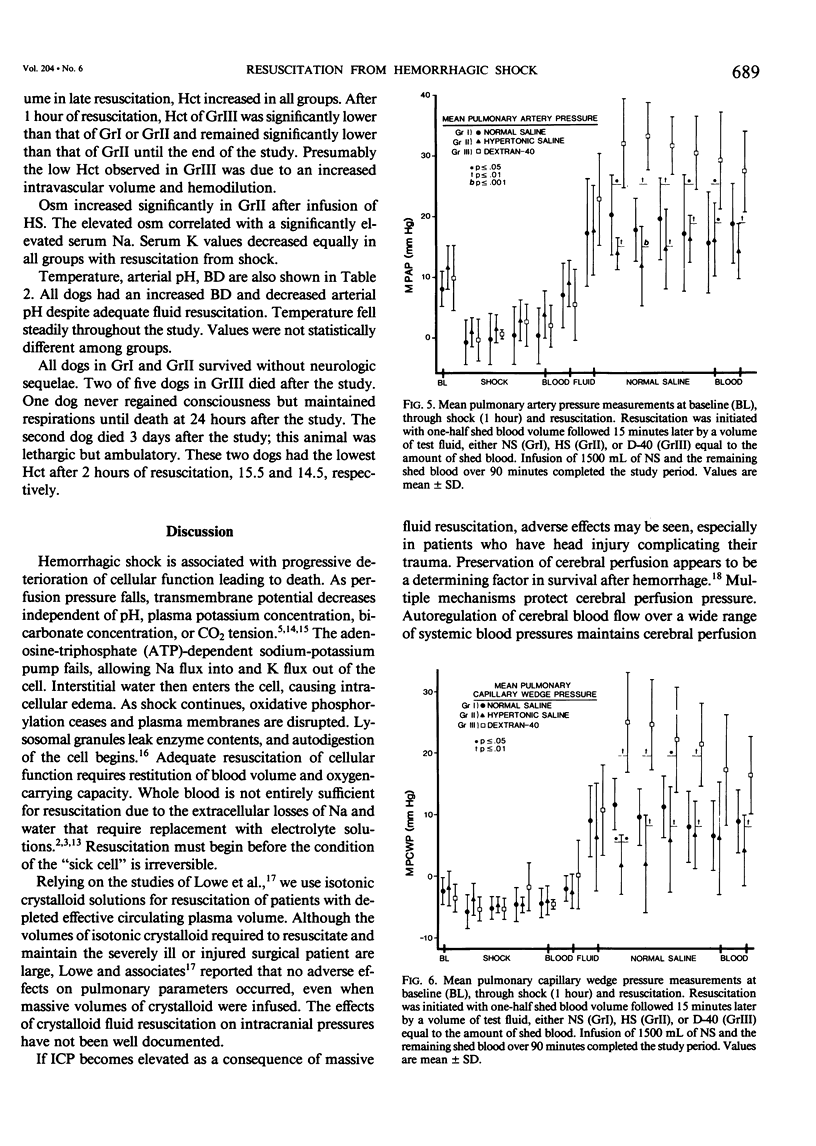

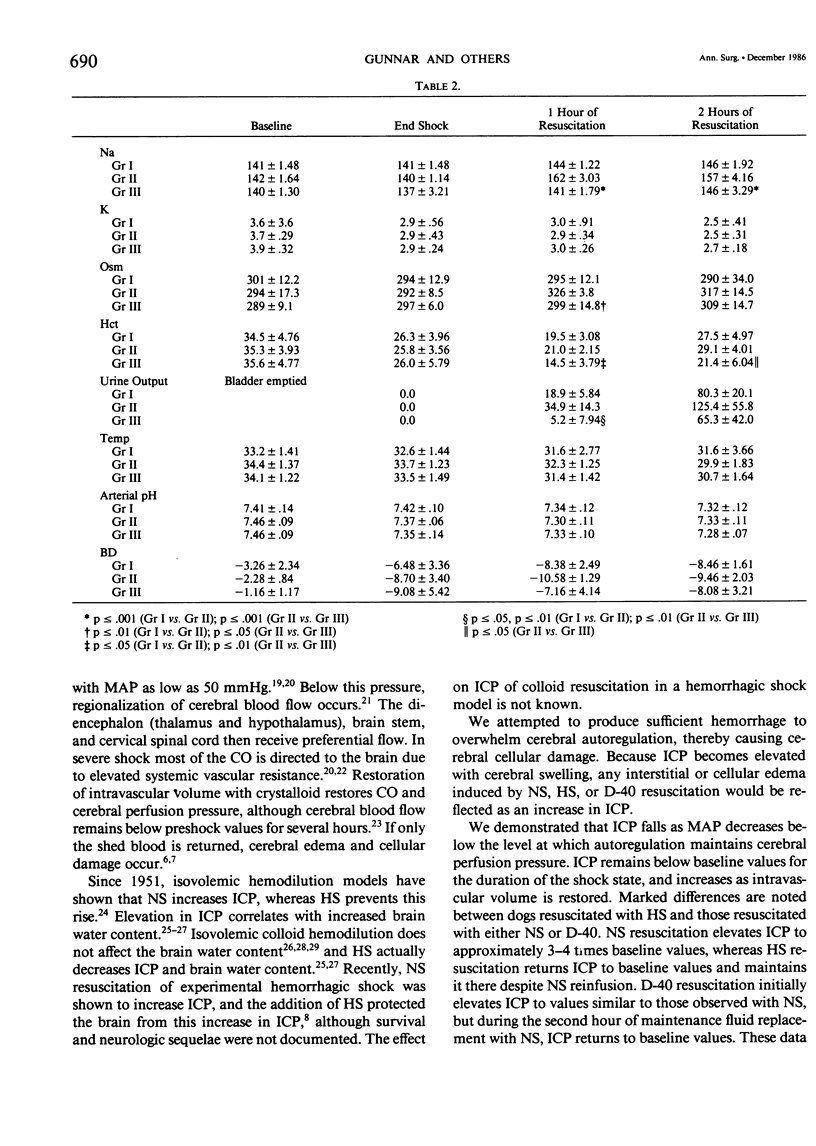

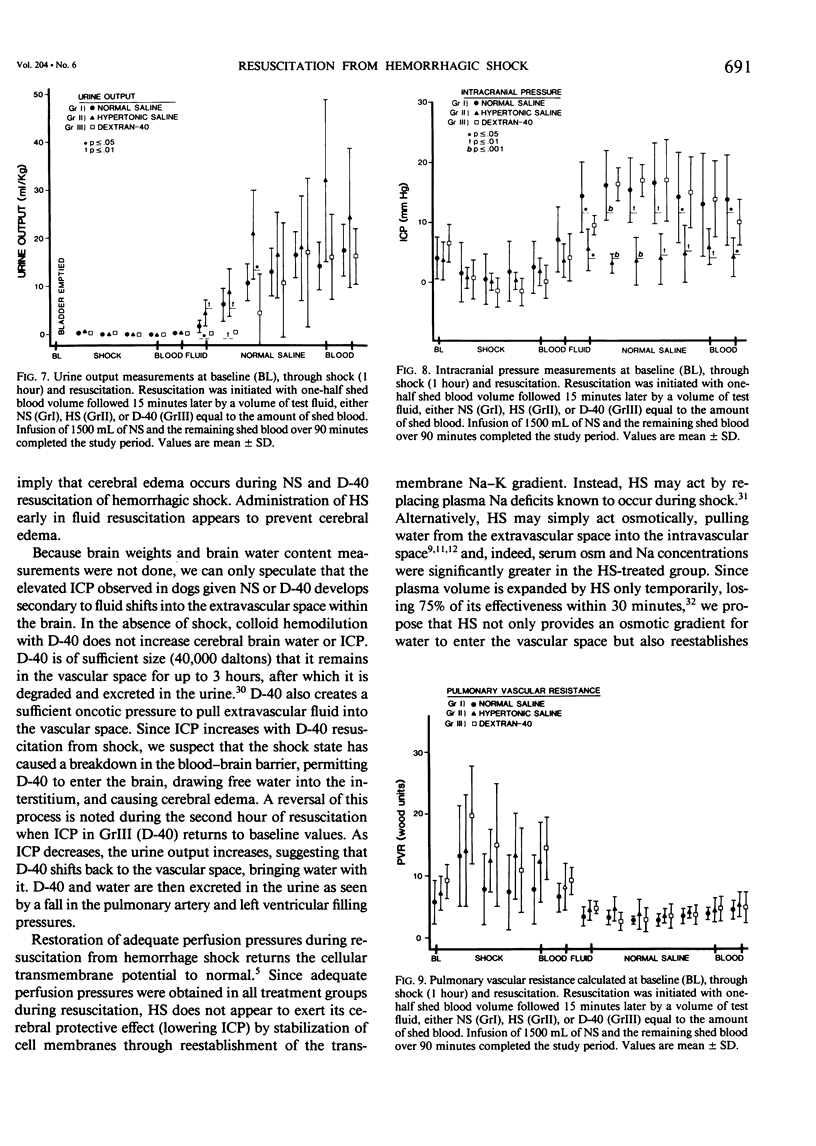

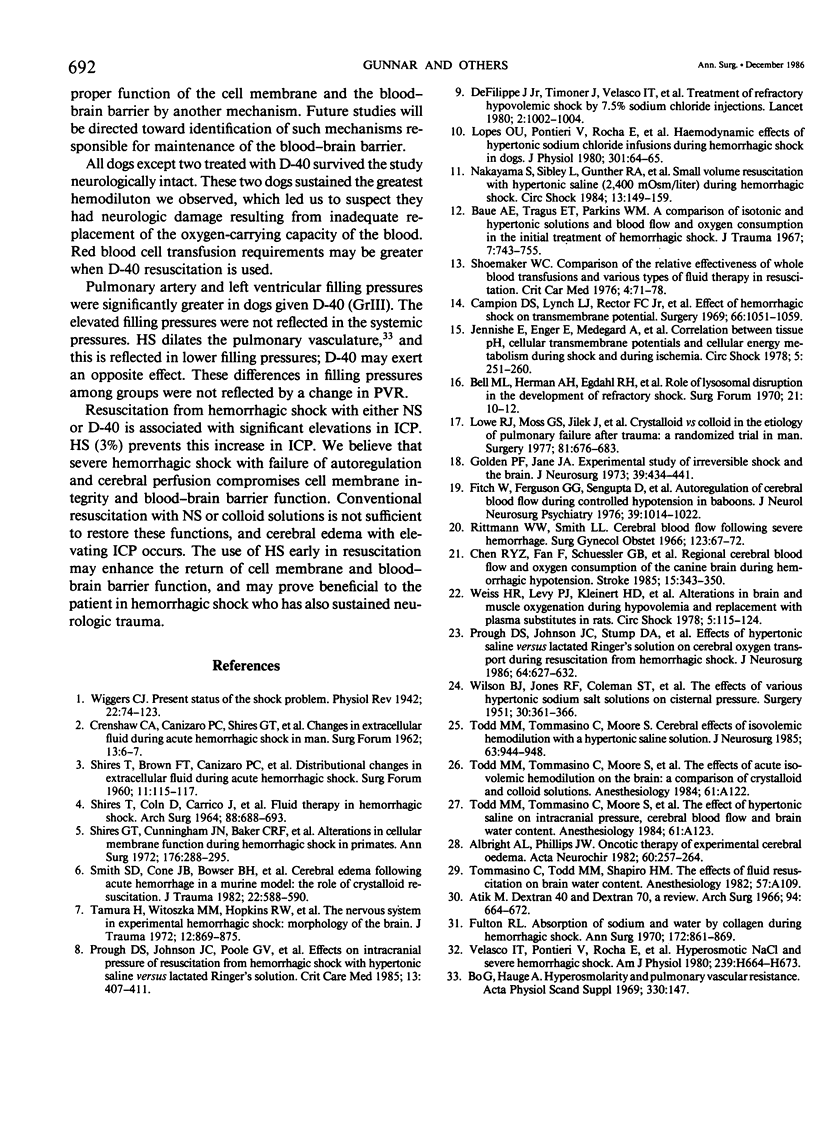

Resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock by infusion of isotonic (normal) saline (NS) is accompanied by a transient elevation in intracranial pressure (ICP), although cerebral edema, as measured by brain weights at 24 hours, is prevented by adequate volume resuscitation. The transient increase in ICP is not observed during hypertonic saline (HS) resuscitation. The effect of colloid resuscitation on ICP is unknown. Beagles were anesthetized, intubated, and ventilated, maintaining pCO2 between 30-45 torr. Femoral artery, pulmonary artery, and urethral catheters were positioned. ICP was measured with a subarachnoid bolt. Forty per cent of the dog's blood volume was shed and the shock state maintained for 1 hour. Resuscitation was done with shed blood and a volume of either NS (n = 5), 3% HS (n = 5), or 10% dextran-40 (D-40, n = 5) equal to the amount of shed blood. Intravascular volume was then maintained with NS. ICP fell from baseline values (4.7 +/- 3.13 mmHg) during the shock state and increased greatly during initial fluid resuscitation in NS and D-40 groups, to 16.0 +/- 5.83 mmHg and 16.2 +/- 2.68 mmHg, respectively. ICP returned to baseline values of 3.0 +/- 1.73 mmHg in the HS group with initial resuscitation and remained at baseline values throughout resuscitation. NS and D-40 ICP were greater than HS ICP at 1 hour (p less than .001) and 2 hours (p less than .05) after resuscitation. These results demonstrate that NS or colloid resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock elevates ICP and that HS prevents elevated ICP.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Albright A. L., Phillips J. W. Oncotic therapy of experimental cerebral oedema. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1982;60(3-4):257–264. doi: 10.1007/BF01406311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atik M. Dextran 40 and dextran 70. A review. Arch Surg. 1967 May;94(5):664–672. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1967.01330110080011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baue A. E., Tragus E. T., Parkins W. M. A comparison of isotonic and hypertonic solutions and blood on blood flow and oxygen consumption in the initial treatment of hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 1967 Sep;7(5):743–756. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196709000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell M. L., Herman A. H., Egdahl R. H., Smith E. E., Rutenburg A. M. Role of lysosomal disruption in the development of refractory shock. Surg Forum. 1970;21:10–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRENSHAW C. A., CANIZARO P. C., SHIRES G. T., ALLSMAN A. Changes in extracellular fluid during acute hemorrhagic shock in man. Surg Forum. 1962;13:6–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campion D. S., Lynch L. J., Rector F. C., Jr, Carter N., Shires G. T. Effect of hemorrhagic shock on transmembrane potential. Surgery. 1969 Dec;66(6):1051–1059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R. Y., Fan F. C., Schuessler G. B., Simchon S., Kim S., Chien S. Regional cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption of the canine brain during hemorrhagic hypotension. Stroke. 1984 Mar-Apr;15(2):343–350. doi: 10.1161/01.str.15.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch W., Ferguson G. G., Sengupta D., Garibi J., Harper A. M. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow during controlled hypotension in baboons. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1976 Oct;39(10):1014–1022. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.39.10.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton R. L. Adsorption of sodium and water by collagen during hemorrhagic shock. Ann Surg. 1970 Nov;172(5):861–869. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197011000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden P. F., Jane J. A. Experimental study of irreversible shock and the brain. J Neurosurg. 1973 Oct;39(4):434–441. doi: 10.3171/jns.1973.39.4.0434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennische E., Enger E., Medegård A., Appelgren L., Haljamäe H. Correlation between tissue pH, cellular transmembrane potentials, and cellular energy metabolism during shock and during ischemia. Circ Shock. 1978;5(3):251–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe R. J., Moss G. S., Jilek J., Levine H. D. Crystalloid vs colloid in the etiology of pulmonary failure after trauma: a randomized trial in man. Surgery. 1977 Jun;81(6):676–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama S., Sibley L., Gunther R. A., Holcroft J. W., Kramer G. C. Small-volume resuscitation with hypertonic saline (2,400 mOsm/liter) during hemorrhagic shock. Circ Shock. 1984;13(2):149–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prough D. S., Johnson J. C., Stump D. A., Stullken E. H., Poole G. V., Jr, Howard G. Effects of hypertonic saline versus lactated Ringer's solution on cerebral oxygen transport during resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock. J Neurosurg. 1986 Apr;64(4):627–632. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.64.4.0627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittmann W. W., Smith L. L. Cerebral blood flow following severe hemorrhage. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1966 Jul;123(1):67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIRES T., COLN D., CARRICO J., LIGHTFOOT S. FLUID THERAPY IN HEMORRHAGIC SHOCK. Arch Surg. 1964 Apr;88:688–693. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1964.01310220178027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shires G. T., Cunningham J. N., Backer C. R., Reeder S. F., Illner H., Wagner I. Y., Maher J. Alterations in cellular membrane function during hemorrhagic shock in primates. Ann Surg. 1972 Sep;176(3):288–295. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197209000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker W. C. Comparison of the relative effectiveness of whole blood transfusions and various types of fluid therapy in resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 1976 Mar-Apr;4(2):71–78. doi: 10.1097/00003246-197603000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. D., Cone J. B., Bowser B. H., Caldwell F. T., Jr Cerebral edema following acute hemorrhage in a murine model: the role crystalloid resuscitation. J Trauma. 1982 Jul;22(7):588–590. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198207000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura H., Witoszka M. M., Hopkins R. W., Simeone F. A. The nervous system in experimental hemorrhagic shock: morphology of the brain. J Trauma. 1972 Oct;12(10):869–875. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197210000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd M. M., Tommasino C., Moore S. Cerebral effects of isovolemic hemodilution with a hypertonic saline solution. J Neurosurg. 1985 Dec;63(6):944–948. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.63.6.0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco I. T., Pontieri V., Rocha e Silva M., Jr, Lopes O. U. Hyperosmotic NaCl and severe hemorrhagic shock. Am J Physiol. 1980 Nov;239(5):H664–H673. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.239.5.H664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILSON B. J., JONES R. F., COLEMAN S. T., MOYER C. A. The effects of various hypertonic sodium salt solutions on cisternal pressure. Surgery. 1951 Aug;30(2):361–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss H. R., Levy P. J., Kleinert H. D., Murthy V. S. Alterations in brain and muscle oxygenation during hypovolemia and replacement with plasma substitutes in rats. Circ Shock. 1978;5(2):115–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Felippe J., Jr, Timoner J., Velasco I. T., Lopes O. U., Rocha-e-Silva M., Jr Treatment of refractory hypovolaemic shock by 7.5% sodium chloride injections. Lancet. 1980 Nov 8;2(8202):1002–1004. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]