Abstract

Penicillin binding protein 4 (PBP4) is essential for Staphylococcus aureus cortical bone osteocyte lacunocanalicular network (OLCN) invasion, which causes osteomyelitis and serves as a bacterial niche for recurring bone infection. Moreover, PBP4 is also a key determinant of S. aureus resistance to fifth-generation cephalosporins (ceftobiprole and ceftaroline). From these perspectives, the development of S. aureus PBP4 inhibitors may represent dual functional therapeutics that prevent osteomyelitis, and reverse PBP4-mediated β-lactam resistance. A high-throughput screen for small molecules that inhibit S. aureus PBP4 function identified compound 1 We recently described a preliminary structure activity relationship (SAR) study on 1, identifying several compounds with increased PBP4 inhibitory activity, some of which also inhibit PBP2a. Herein, we expand our exploration of phenyl ureas as antibiotic adjuvants, investigating their activity with penicillins and additional cephalosporins against PBP2a-mediated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA). We screened the previously reported pilot library, and prepared an additional series of phenyl ureas based on compound 1. Lead compounds potentiate multiple β-lactam antibiotics, lowering minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) below susceptibility breakpoints, with up to 64-fold reductions in MIC.

Keywords: Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Adjuvant, Antibiotic resistance, β-Lactam, Phenyl urea

The rise in antibiotic resistance, and a concomitant decline in efficacious treatment options for bacterial infections remains an urgent threat to global human health. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that approximately 2.8 million people acquire an antibiotic-resistant infection annually in the United States, resulting in approximately 35,000 deaths.1 Accounting for a large proportion of resistant infections are the ESKAPE pathogens (Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterobacter species), which are known for their ability to ‘escape’ the action of antibiotics.2 S. aureus, specifically methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), one of the most prevalent pathogens in community and healthcare infections, is responsible for an estimated 10,600 annual deaths, and poses an economic burden upwards of $1.7 billion each year in the United States.1

One approach to combatting antibiotic resistance is the development of non- microbicidal small molecule adjuvants that disrupt resistance mechanisms, and potentiate the activity of conventional antibiotics. Adjuvants typically have little to no antibacterial properties themselves, but enhance the efficacy of antibiotics through various mechanisms, including: inhibiting proteins that mediate antibiotic modification, enhancement of antibiotic uptake, inhibition of efflux, or inhibition of signaling pathways that are essential for antibiotic resistance.3–5 The classic example of this approach is Augmentin, a combination of amoxicillin and the β-lactamase inhibitor clavulanic acid that has been successfully employed in the clinic since the 1980s.6

β-Lactam antibiotics, which covalently bind penicillin binding proteins (PBPs), disrupt peptidoglycan cross-linking during cell wall biosynthesis and lead to bacterial lysis and cell death.7 A suite of β-lactams are efficacious against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, although increasing levels of resistance render them inadequate treatment options in many cases.8–12 S. aureus, encodes four native PBPs: PBP1, PBP2, PBP3, and PBP4, of which PBP3 and PBP4 are non-essential.13–15 Resistance to β-lactams in MRSA predominantly occurs through the acquisition of the non-native PBP2a, which has a lower affinity for most β-lactam antibiotics than do the native PBPs, including PBP4.8,12,16–18 It has recently been recognized that S. aureus also employs a non-canonical, PBP2a-independent MRSA pathway that is governed by PBP4 overexpression.13,19–21 Such PBP4 overproducers exhibit high-level resistance to all β-lactams including fifth generation cephalosporins (ceftobiprole and ceftaroline), which are the only clinically employed β-lactams that bind PBP2a with high affinity.22 Moreover, PBP4 is essential for S. aureus osteocyte lacuna-canalicular network (OLCN) invasion in vivo, as a mutant lacking pbp4 was unable to initiate osteomyelitis in a murine model of infection, validating PBP4 as a promising target for the prevention of osteomyelitis.23 Therefore the potential therapeutic impact of PBP4 inhibitors encompasses use both as β-lactam adjuvants, and in the treatment of osteomyelitis.

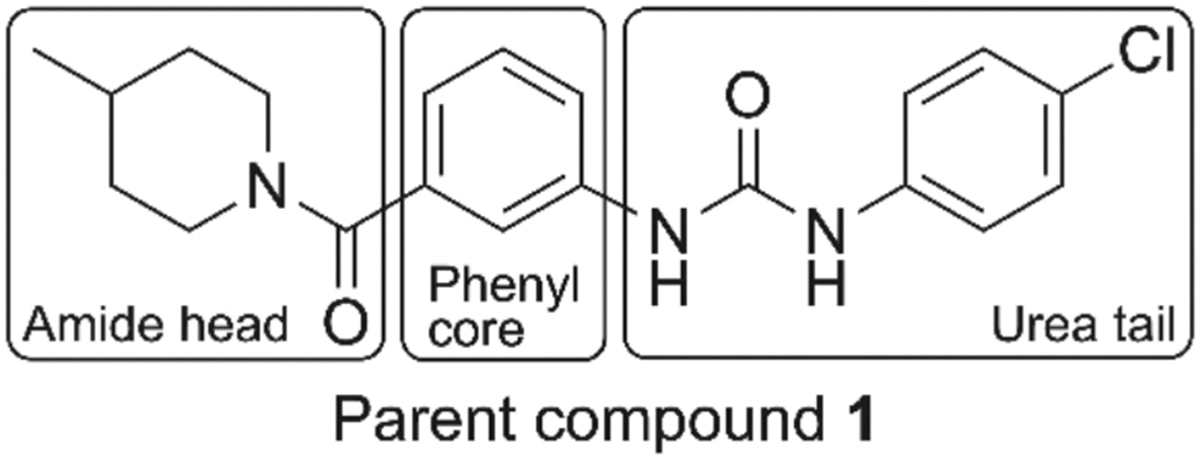

Previously, we identified phenyl urea 1 (Fig. 1) as an inhibitor of S. aureus’ PBP4 function from a whole-cell high-throughput screen of a 30,000-member small molecule library.20 More recently, we developed an in silico model for targeting PBP4 with this chemical scaffold, and subsequently synthesized a series of phenyl urea analogs (2–18 Fig. 2) to explore the structure activity relationship (SAR) around the 4-chlorophenyl tail of compound 1.24 When examining the selectivity of the phenyl ureas for PBP4 over other PBPs, we noted that several compounds exhibit moderate affinity for PBP2a (albeit lower than for PBP4), leading us to posit their utility as adjuvants for a variety of β-lactam antibiotics whose resistance is mediated by PBP2a. Herein, we detail our investigation of the phenyl urea scaffold to identify compounds that enhance β-lactam efficacy against MRSA.

Fig. 1.

Structure of parent compound 1 showing amide head, phenyl core, and urea tail regions for SAR exploration as antibiotic adjuvants against MRSA.

Fig. 2.

Urea tail analogs 2–18, synthesized in our prior study. 24

We previously determined that parent compound 1 and analogs 2–18 (Fig. 2) are non-toxic towards S. aureus, registering stand-alone minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 200 μM or greater against two USA300 MRSA strains (ATCC BAA-1556 and AH-1263).24 We began the initial evaluation of the adjuvant potential of this library against BAA-1556 and AH-1263 at a concentration of 60 μM, using oxacillin as our representative β-lactam (Table 1). Compound 1 reduces the oxacillin MIC from 32 μg/mL to its Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoint value of 2 μg/mL25 (16-fold) against BAA-1556, and from 32 μg/mL to 1 μg/mL (32-fold) against AH-1263. Compound 2, which has a chloro substituent at the 3-position of the phenyl ring, is equipotent (MIC within two-fold) to 1 against both strains. The 3,5-dichlorophenyl analog 3 and the 3,4-dichlorophenyl compound 4 are less active than 1, against AH-1263, only lowering the oxacillin MIC four-fold, while the 2,3-dichlorophenyl analog 5 is inactive against both strains.

Table 1.

Potentiation of oxacillin by group 1 analogs against MRSA ATCC BAA-1556 and AH-1263. All compounds tested at 60 μM. OX denotes oxacillin alone.

| Oxacillin MIC (μg/mL) (fold reduction) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Compound | ATCC BAA-1556 | AH-1263 |

|

| ||

| OX | 32 | 32 |

| 1 | 2 (16) | 1 (32) |

| 2 | 1 (32) | 1 (32) |

| 3 | 4 (8) | 8 (4) |

| 4 | 2 (16) | 8 (4) |

| 5 | 16 (2) | 16 (2) |

| 6 | 32 (–) | 32 (–) |

| 7 | 2 (16) | 8 (4) |

| 8 | 64 (–) | 64 (–) |

| 9 | 2 (16) | 2 (16) |

| 10 | 64 (–) | 64 (–) |

| 11 | 64 (–) | 16 (2) |

| 12 | 32 (–) | 32 (–) |

| 13 | 16 (2) | 16 (2) |

| 14 | 1 (32) | 1 (32) |

| 15 | 16 (2) | 16 (2) |

| 16 | 16 (2) | 32 (–) |

| 17 | 16 (2) | 8 (4) |

| 18 | 8 (4) | 8 (4) |

Compounds 6, 8, and 10, which contain either electron-donating (6 and 8) or electron withdrawing (10) substituents at the 4-position of the phenyl urea tail are all inactive. The 4-methyl analog 7 has lower activity than 1 against AH-1263, however, the 4-fluoro analog 9 is equipotent to 1 against both strains. Analogs 11, 12, and 13, which contain varying di-substitution patterns on the phenyl urea tail, are inactive against both strains.

Compound 14, which possesses a 3-methylphenyl urea tail, is active against both MRSA strains, lowering the oxacillin MIC to 1 μg/mL (32-fold reduction). Compounds 15 and 16, which have a 3-trifluoromethylphenyl and 2-fluorophenyl tail respectively, are both inactive. The unsubstituted phenyl analog 17 is inactive against BAA-1556 and has only moderate activity (four-fold reduction in oxacillin MIC) against AH-1263, demonstrating the essentiality of phenyl ring substitution for activity.

Lastly, for the series of phenyl urea tail analogs, we looked at the impact of replacing the aromatic phenyl ring with an aliphatic (cyclohexyl) ring. Compound 18 exhibits only moderate activity, lowering the MIC to 8 μg/mL (four-fold reduction) against both strains. From this first group of phenyl urea tail analogs, compounds 2, 4, 7, 9, and 14 are equipotent to parent compound 1 against at least one strain, with analogs 2 and 14 the most active, both lowering the oxacillin MIC to 1 μg/mL, (32-fold), against both BAA-1556 and AH-1263.

Next, we expanded the first-generation library to study the impact that varying the identity of the amide head group (R1) has upon activity, by synthesizing compounds 19–28 (Scheme 1)). When designing analogs of 1 with altered amide heads, we explored a variety of aliphatic, aromatic and heteroaromatic amines in place of the 4-methyl piperidine group of compound 1. Compounds were synthesized as previously reported using the approach outlined in Scheme 1 (compound 21 was purchased).24 The appropriate commercially available amine first underwent an EDC mediated coupling with 3-nitrobenzoic acid or 4-nitrobenzoic acid to form amides 19a-28a, followed by a Pd/C catalyzed reduction of the nitro group to produce the aniline intermediates 19b-28b, which were coupled with 4-chlorophenyl isocyanate, or underwent CDI mediated reaction with 4-chloroaniline, to yield the urea products 19–28.

Scheme 1.

General synthesis of second generation phenyl urea analogs. Reagents & conditions: (a) 3-nitrobenzoic acid or 4-nitrobenzoic acid, EDC, DMAP, DCM, rt., 24 h; (b) Pd/C (10 %), H2, MeOH, rt., 12 h or Na2S2O4, DMF/H2O (9:1), 90 °C, 3 h; (c) 4-chlorophenyl isocyanate, Et3N, DCM, rt., 16 h or 4-chloroaniline, CDI, Et3N, DCM, rt., 12 h.

Compound 19 possesses a pyrrolidine group in place of the 4-methylpiperidine group of compound 1. In compound 20, an oxygen atom is introduced to the aliphatic ring through a morpholine group, in compound 21 the 4-methyl group is removed from the piperidine ring, while compound 22 has a cyclohexylamino moiety. Aromatic head groups including 3-aminopyridine (23), aniline (24), 4-chloroaniline (25), 3,5-dimethylaniline (26) and 3,5-dimethoxyanline (27) are explored. Finally, compound 28 contains a 4-methylpiperidine head group with a para orientation to the urea linker, as opposed to the meta orientation of compound 1.

None of the second-generation analogs exhibit comparable potency compared to compound 1 (Table 2). Only compound 19 lowers the oxacillin MIC more than two-fold against either strain, effecting a modest four-fold reduction against AH-1263, illustrating the essentiality of the 4-methylpiperidine group for oxacillin potentiation.

Table 2.

Potentiation of oxacillin by amide head analogs (19–28) against MRSA ATCC BAA-1556 and AH-1263. All compounds tested at 60 μM. OX denotes oxacillin alone.

| Oxacillin MIC (μg/mL) (fold reduction) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Compound | ATCC BAA-1556 | AH-1263 |

|

| ||

| OX | 32 | 32 |

| 1 | 2 (16) | 1 (32) |

| 19 | 16 (2) | 8 (4) |

| 20 | 32 (–) | 16 (2) |

| 21 | 16 (2) | 16 (2) |

| 22 | 32 (–) | 32 (–) |

| 23 | 64 (–) | 64 (–) |

| 24 | 32 (–) | 32 (–) |

| 25 | 32 (–) | 32 (–) |

| 26 | 32 (–) | 32 (–) |

| 27 | 32 (–) | 64 (–) |

| 28 | 16 (2) | 16 (2) |

Following these studies, the SAR of the phenyl urea scaffold for potentiation of additional β-lactam antibiotics was further explored by screening parent compound 1 and eight additional derivatives (compounds 2, 4, 7, 9, 14, 19, 21, and 28) with six additional β-lactam antibiotics (three penicillins and three cephalosporins) against the same two MRSA strains (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Potentiation of penicillin antibiotics by phenyl urea adjuvants against MRSA ATCC BAA-1556 and AH-1263. All compounds tested at 60 μM. ABX denotes respective antibiotic tested alone.

| Compound | Penicillin G MIC (μg/mL) (fold reduction) | Amoxicillin MIC (μg/mL) (fold reduction) | Ampicillin MIC (μg/mL) (fold reduction) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| ATCC BAA-1556 | AH-1263 | ATCC BAA-1556 | AH-1263 | ATCC BAA-1556 | AH-1263 | |

|

| ||||||

| ABX | 4 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 1 | 4 (–) | 0.0625 (64) | 4 (2) | 8 (–) | 2 (4) | 1 (8) |

| 2 | 0.125 (32) | 0.125 (32) | 0.5 (16) | 0.5 (16) | 0.25 (32) | 0.25 (32) |

| 4 | 0.25 (16) | 2 (2) | 1 (8) | 4 (2) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) |

| 7 | 0.5 (8) | 1 (4) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 1 (8) | 1 (8) |

| 9 | 0.5 (8) | 1 (4) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 0.5 (16) | 1 (8) |

| 14 | 0.25 (16) | 0.25 (16) | 0.5 (16) | 0.5 (16) | 0.5 (16) | 0.5 (16) |

| 19 | 0.5 (8) | 0.5 (8) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 1 (8) | 2 (4) |

| 21 | 0.125 (32) | 0.25 (16) | 0.5 (16) | 0.5 (16) | 0.5 (16) | 0.5 (16) |

| 28 | 4 (–) | 4 (–) | 8 (–) | 4 (2) | 8 (–) | 8 (–) |

Table 4.

Potentiation of cephalosporin antibiotics by phenyl urea adjuvants against MRSA ATCC BAA-1556 and AH-1263. All compounds tested at 60 μM. ABX denotes antibiotic alone.

| Compound | Cefoxitin MIC (μg/mL) (fold reduction) | Cefotaxime MIC (μg/mL) (fold reduction) | Cephalothin MIC (μg/mL) (fold reduction) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| ATCC BAA-1556 | AH-1263 | ATCC BAA-1556 | AH-1263 | ATCC BAA-1556 | AH-1263 | |

|

| ||||||

| ABX | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 4 | 4 |

| 1 | 32 (–) | 32 (–) | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 4 (–) | 1 (4) |

| 2 | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 1 (4) | 0.5 (8) |

| 4 | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 1 (4) | 2 (2) |

| 7 | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 4 (–) | 2 (2) |

| 9 | 16 (2) | 8 (4) | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| 14 | 16 (2) | 8 (4) | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 0.5 (8) | 0.25 (16) |

| 19 | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 16 (2) | 1 (4) | 2 (2) |

| 21 | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 8 (4) | 0.5 (8) | 0.5 (8) |

| 28 | 32 (–) | 32 (–) | 32 (–) | 32 (–) | 2 (2) | 4 (–) |

The representative penicillins evaluated were the natural penicillin: penicillin G, and the aminopenicillins: amoxicillin and ampicillin. Three of the nine compounds reduce the MIC of penicillin G to its clinical breakpoint of 0.125 μg/mL25 against at least one of the two strains (Table 3), with the most potent compounds being 1, 2, and 21, which lower the penicillin G MIC by 64-fold, 32-fold, and 32-fold respectively. Although compound 14 does not lower the penicillin G MIC to its clinical breakpoint, it does lower it 16-fold from 4 μg/mL to 0.25 μg/mL against both strains. Three compounds (2, 14, and 21) lower the amoxicillin MIC below its clinical breakpoint of 2 μg/mL (Streptococcus pneumoniae breakpoint selected for use as the standard here, as no CLSI breakpoint is established for amoxicillin in S. aureus),25 from 8 μg/mL to 0.5 μg/mL against both strains. Analogs 2, 14, and 21 are also the most active in combination with ampicillin, lowering the MIC to or within two-fold of its breakpoint value (0.25 μg/mL in Streptococcus viridians)25 in both strains.

As with oxacillin, compounds 2 and 14 exhibit the most potent activity with the additional penicillin antibiotics. In contrast, analog 21, which does not potentiate oxacillin, displays increased potency with penicillin G, amoxicillin, and ampicillin, while compound 1 potentiates penicillin G against MRSA AH-1263 (64-fold MIC reduction) but not BAA-1556, only moderately potentiates ampicillin (four to eight-fold MIC reduction), and does not potentiate amoxicillin against either strain.

Lastly, compounds were evaluated for activity with three diverse cephalosporins: cephalothin (1st generation), cefoxitin (2nd generation), and cefotaxime (3rd generation) (Table 4). First-generation cephalosporins are active against gram-positive cocci, including methicillin susceptible S. aureus, while 2nd and 3rd generation cephalosporins exhibit reduced S. aureus activity compared to 1st generation cephalosporins.26 None of the compounds reduced the MIC of cefoxitin to its breakpoint of 4 μg/mL in either strain tested.25 Although compound 21 reduces the cefotaxime MIC four-fold from 32 μg/mL to 8 μg/mL against both strains, it does not lower the cefotaxime MIC below its clinical breakpoint of 1 μg/mL (Streptococcus viridans breakpoint selected for use as standard here as no CLSI breakpoint is established for cefotaxime in S. aureus).26 All compounds reduce the MIC of cephalothin by a minimum of four-fold against at least one strain, with analogs 2, 14, and 21 being the most active, reducing the MIC by eight-fold, 16-fold, and eight-fold respectively against at least one strain. There is no CLSI breakpoint established for cephalothin in S. aureus or other gram-positive strains. With the cephalosporin antibiotics, the most active compounds are again 2, 14, and 21; however, all three compounds exhibit greater activity with the panel of penicillins examined here.

In conclusion, we synthesized and evaluated 29 phenyl urea adjuvants in combination with seven β-lactam antibiotics. We identified several compounds that potentiate β-lactam antibiotics against two PBP2a mediated MRSA strains, decreasing MICs up to 64-fold. The mechanism of action of these compounds is potentially via inhibition of PBP2a in addition to other PBPs, and further assays to confirm this will be reported in due course. The most potent compounds exhibit greater activity in combination with penicillin antibiotics compared to cephalosporins, and activity with oxacillin is not necessarily predictive of activity with other β-lactam antibiotics, suggesting the possible need for specific antibiotic pairing with this class of adjuvants. Studies to address these fundamental mechanistic questions are being pursued.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2025.130164.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the National Institutes of Health (DE022350 to CM, AI175024; AI134685; and AR072000 to PMD). The graphical abstract was created in BioRender. Nemeth, A. (2024) https://BioRender.com/g04q263

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Christian Melander reports financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health. Paul Dunman reports financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hailey S. Butman: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation. Monica A. Stefaniak: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation. Danica J. Walsh: Investigation. Vijay S. Gondil: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Mikaeel Young: Investigation. Andrew H. Crow: Investigation. Ansley M. Nemeth: Investigation. Roberta J. Melander: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation. Paul M. Dunman: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Christian Melander: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.

References

- 1.CDC. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. 2013.

- 2.Pendleton JN, Gorman SP, Gilmore BF. Clinical relevance of the ESKAPE pathogens. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2013;11(3):297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melander RJ, Melander C. The challenge of overcoming antibiotic resistance: an adjuvant approach? ACS Infect Dis. 2017;3(8):559–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright GD. Antibiotic adjuvants: rescuing antibiotics from resistance. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24(11):862–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.González-Bello C Antibiotic adjuvants - a strategy to unlock bacterial resistance to antibiotics. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2017;27(18):4221–4228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geddes AM, Klugman KP, Rolinson GN. Introduction: historical perspective and development of amoxicillin/clavulanate. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;30(suppl 2):S109–S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bush K, Bradford PA. β-Lactams and β-Lactamase Inhibitors: an overview. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;Vol. 6(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Worthington RJ, Melander C. Overcoming resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics. J Organomet Chem. 2013;78(9):4207–4213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mora-Ochomogo M, Lohans CT. β-Lactam antibiotic targets and resistance mechanisms: from covalent inhibitors to substrates. RSC Med Chem. 2021;12(10):1623–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander JAN, Worrall LJ, Hu J, et al. Structural basis of broad-spectrum β-lactam resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Nature. 2023;613(7943):375–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher JF, Meroueh SO, Mobashery S. Bacterial resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics: compelling opportunism, compelling opportunity. Chem Rev. 2005;105(2):395–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster TJ. Antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Current status and future prospects. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2017;41(3):430–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Navratna V, Nadig S, Sood V, Prasad K, Arakere G, Gopal B. Molecular basis for the role of Staphylococcus aureus penicillin binding protein 4 in antimicrobial resistance. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(1):134–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Memmi G, Filipe SR, Pinho MG, Fu Z, Cheung A. Staphylococcus aureus PBP4 is essential for beta-lactam resistance in community-acquired methicillin-resistant strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(11):3955–3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chambers HF. Penicillin-binding protein-mediated resistance in pneumococci and staphylococci. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(suppl 2):S353–S359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Łeski TA, Tomasz A. Role of penicillin-binding protein 2 (PBP2) in the antibiotic susceptibility and cell wall cross-linking of Staphylococcus aureus: evidence for the cooperative functioning of PBP2, PBP4, and PBP2A. J Bacteriol. 2005;187(5):1815–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otero LH, Rojas-Altuve A, Llarrull LI, et al. How allosteric control of Staphylococcus aureus penicillin binding protein 2a enables methicillin resistance and physiological function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(42):16808–16813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fishovitz J, Hermoso JA, Chang M, Mobashery S. Penicillin-binding protein 2a of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. IUBMB Life. 2014;66(8):572–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyke AW, Ward JB, Hayes MV, Curtis NA. A role in vivo for penicillin-binding protein-4 of Staphylococcus aureus. Eur J Biochem. 1981;119(2):389–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young M, Walsh DJ, Masters E, et al. Identification of identification of Staphylococcus aureus penicillin binding protein 4 (PBP4) inhibitors. Antibiotics (Basel). 2022;11(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander JAN, Chatterjee SS, Hamilton SM, Eltis LD, Chambers HF, Strynadka NCJ. Structural and kinetic analyses of penicillin-binding protein 4 (PBP4)-mediated antibiotic resistance in. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(51):19854–19865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton SM, Alexander JAN, Choo EJ, et al. High-level resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to β-lactam antibiotics mediated by penicillin-binding protein 4 (PBP4). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masters EA, de Mesy Bentley KL, Gill AL, et al. Identification of penicillin binding protein 4 (PBP4) as a critical factor for Staphylococcus aureus bone invasion during osteomyelitis in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(10), e1008988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gondil VS, Butman HS, Young M, et al. Development of phenyl-urea-based small molecules that target penicillin-binding protein 4. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2024;103(6), e14569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Suceptibility Testing; Nineteenth Informational Supplement. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison CJ, Bratcher D. Cephalosporins: a review. Pediatr Rev. 2008;29(8):264–267. quiz 273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.