Abstract

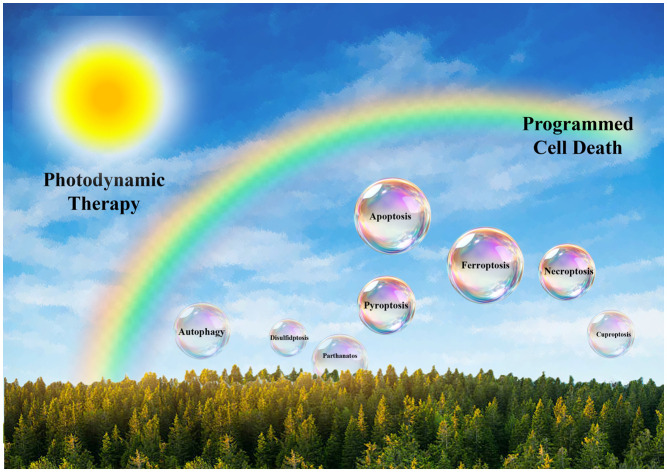

A fundamental biological mechanism, programmed cell death (PCD), is essential for tissue homeostasis, immunological control, and development. Its dysregulation is a characteristic of many diseases in multicellular organisms, including cancer, where unchecked proliferation is made possible by evading cell death. Therefore, one of the main tenets of contemporary anticancer therapies is the restoration or induction of PCD in cancer cells. One potential, least invasive method among these is photodynamic treatment (PDT). PDT uses light-activatable photosensitisers, which cause cancer cells to explode with reactive oxygen species (ROS) when exposed to light. These ROS harm important biomolecules, throw off the cellular redox equilibrium, and cause cells to die. PDT-induced cell death was previously believed to be mostly caused by autophagy, necrosis, or apoptosis. Recent research, however, has shown that it can trigger a wider range of unconventional cell death pathways. ROS can cause ferroptosis by oxidising membrane lipids, fragmenting DNA, and lowering intracellular glutathione (GSH) levels. Similarly, necroptosis or pyroptosis can result from severe oxidative stress activating death receptor signalling. Sometimes, in response, cells use survival strategies like autophagy, which can also lead to cell death. This review explores these new, unconventional methods of cell death and how PDT can be used to take advantage of them. Next-generation photosensitisers based on iridium (Ir), ruthenium (Ru), and rhenium (Re) complexes are given special attention because they provide deep tissue penetration, improved photostability, and adjustable ROS production. Their incorporation into PDT has revolutionary potential for improving cancer treatment precision and conquering therapeutic resistance.

This review investigates the mechanics behind unconventional cell death pathways for anticancer treatments: the role photodynamic therapy plays in inducing them, and further encourages investigation into the use of atypical cell death pathways.

1. Introduction

Due to its high prevalence, fatality rates, and the financial toll it takes on healthcare systems around the world, cancer continues to be a serious global health concern.1 The World Health Organisation (WHO) recently estimated that cancer was the second largest cause of death worldwide in 2020, accounting for around 10 million fatalities.2 Tumour heterogeneity and adaptive capacity frequently lead to medication resistance, disease recurrence, and metastasis, even with significant advancements in early diagnosis, diagnostics, and therapeutic modalities.3 As a result, oncological research is still motivated by the desire for more specialised, effective, and less harmful therapeutic alternatives. Photodynamic therapy (PDT), one of the newer treatments, has drawn interest because of its distinct mode of action, which uses the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to photoactivate non-toxic substances and produce localised cytotoxic effects. Crucially, the effectiveness of PDT is being connected increasingly to its ability to control and trigger different types of programmed cell death (PCD), a process whose control is essential to the development of cancer and the response to treatment.4

A collection of biological processes known as “programmed cell death” has been conserved throughout evolution and is intended to preserve homeostasis, get rid of damaged or possibly dangerous cells, and influence the immune system.5 Although apoptosis has long been thought to be the most common type of PCD, over the last 20 years, a number of different but connected cell death mechanisms have been discovered, such as necroptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and autophagic cell death. Each of these pathways has distinct morphological characteristics, immunological effects, and molecular signalling cascades.6 Tumour cells frequently develop the capacity to avoid or inhibit various PCD pathways in the context of cancer, which aids in uncontrolled growth, treatment resistance, and immune surveillance evasion. As a result, cancer holds great promise for treatment approaches that might reactivate or avoid these death-resistance pathways. PDT stands out as a strong contender in this respect due to its ability to both geographically and temporally induce oxidative stress and begin numerous death pathways.7

A variety of tactics are used by cancer cells to evade apoptotic signals. Overexpression of anti-apoptotic proteins from the B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family, such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, is a typical mechanism. These proteins impede the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis by blocking the release of cytochrome c and the subsequent activation of caspase.8 On the other hand, tumours frequently downregulate or functionally inactivate pro-apoptotic members of the same family, such as Bak and Bax, which tips the scales in favour of cell survival. Furthermore, almost 50% of human malignancies have mutations in the TP53 gene, which codes for the tumour suppressor protein p53. Since wild-type p53 causes cell cycle arrest or apoptosis in response to a variety of cellular stressors, its deactivation eliminates a crucial obstacle to the growth of tumours. Moreover, inhibitors of apoptosis proteins (IAPs), which bind and block caspases, the primary apoptotic executors, can be upregulated in cancer cells.9,10 Together, these changes allow cancer cells to avoid dying, which leads to unchecked proliferation and resistance to traditional treatments.11,12

The complex and dynamic milieu known as the tumour microenvironment (TME) is made up of several cellular and non-cellular elements that interact with tumour cells to affect the course, metastasis, and response to treatment of cancer.13 Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), immunological cells (including T cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and tumour-associated macrophages), endothelial cells, and pericytes are important biological components of the TME. The extracellular matrix (ECM), growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, and extracellular vesicles are examples of non-cellular components. Through bidirectional communication, these components alter signalling pathways that control angiogenesis, immune evasion, cell proliferation, and survival in tumour cells.14

The TME's function in fostering resistance to cell death is an important feature. For example, CAFs express a range of soluble molecules that can decrease apoptotic signalling and activate survival pathways in cancer cells, including interleukins, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), and ECM components. Similarly, within the TME, tumour-associated macrophages frequently take on an M2-like phenotype, producing growth factors and anti-inflammatory cytokines that promote tumour growth and suppress cytotoxic immune responses.15 Furthermore, hypoxia-induced factors (HIFs) can be stabilised by the hypoxic conditions frequently present in solid tumours as a result of abnormal vasculature.16 These HIFs then upregulate genes related to angiogenesis, metabolism, and survival, further strengthening the tumour's resistance to apoptosis.17

Three components make up the system that powers photodynamic therapy: molecular oxygen, a particular light wavelength, and a photosensitiser (PS).18 When light activates the photosensitiser, it first changes from its ground state to an excited singlet state, then it crosses between systems to reach a triplet state.19 After that, the triplet-state PS can either interact with substrates to create free radicals through type I reactions or transfer energy to molecular oxygen through type II reactions, producing singlet oxygen (1O2) and other ROS. The oxidative damage caused by these highly reactive ROS to vital macromolecules such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids results in cellular malfunction and death.20 While ROS's short half-life and small diffusion distance (∼0.02–0.1 μm) guarantee that cytotoxicity is limited to the lit tumour site, minimising harm to surrounding normal tissue, PDT's spatial selectivity is attributed to the localised nature of light delivery (Fig. 1).21

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram showing the mechanism of action of photodynamic therapy in cancer cells.

For the treatment of cancer, tetrapyrrolic compounds conjugated with metal complexes have emerged as a promising class of PSs in PDT due to their enhanced photophysical and photobiological properties. The coordination of transition metals such as Ru, Cu, Pt, Fe, Rh, Ir, and Pd with compounds including porphyrins, chlorins, bacteriochlorins, and phthalocyanines results in enhanced singlet oxygen production, red-shifted absorbance, and greater photostability. The heavy atom effect, especially from high-Z metals (such Ru, Ir, and Pt), makes it easier for systems to cross one another. This increases the generation of ROS, which, in turn, enhances phototoxicity. Tetra(2-naphthyl)tetracyanoporphyrazine and its Fe(ii) complex, for example, show promising PDT agents due to their strong ROS output and specific tumour accumulation. Strong near-infrared (NIR) absorption by palladium-conjugated porphyrinoids allows for deeper tissue penetration and better hypoxic tumour treatment.22–24 Because of their strong NIR absorption, metallo-bacteriochlorins minimise off-target toxicity by enabling deep tissue activation and demonstrating quick systemic elimination. Through synergistic mechanisms, ruthenium-based tetrapyrrole complexes have demonstrated dual phototoxic and chemotoxic effects, hence enhancing therapeutic efficacy. These metal–tetrapyrrole conjugates' nanoformulations also improve their overall photodynamic performance, targeted administration, and bioavailability. These chemicals have a lot of therapeutic promise despite issues, including poor solubility and possible toxicity. Multidisciplinary attempts to create next-generation PDT agents with strong anticancer activity and less systemic adverse effects are still drawn to their adaptability and tunability.25,26

The potential of PDT to start different PCD pathways based on several factors, including the kind and subcellular location of the photosensitiser, the light dose and fluence rate, the cellular redox state, and the tumour microenvironment, is one of its distinguishing features.27 Certain porphyrins and chlorins are examples of photosensitizers that target mitochondria and can directly damage the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane, causing cytochrome c release, activation of the caspase cascade, and ultimately apoptotic cell death.28 Alternatively, lysosome-localising photosensitizers can cause permeabilisation of the lysosomal membrane, which releases hydrolases such as cathepsins that either directly cause apoptosis or activate other types of PCD.29 Moreover, depending on the strength of stress signals, photosensitizers that build up in the endoplasmic reticulum might cause ER stress and the unfolded protein response, which can result in apoptosis or immunogenic types of cell death.30

The most researched type of PCD, apoptosis, is a tightly controlled, immunologically quiet process that involves both extrinsic and internal signalling pathways.31 The Bcl-2 protein family modulates mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilisation (MOMP), which in turn controls the intrinsic (mitochondrial) route.32 PDT-induced mitochondrial oxidative damage can increase pro-apoptotic proteins like Bak and Bax, which causes cytochrome c to be released and caspase-9 and executioner caspases-3/7 to be activated. Conversely, the extrinsic pathway entails the activation of death receptors, including TRAIL-R and Fas, which results in the recruitment of FADD and the activation of caspase-8. Interestingly, there is a lot of interaction between the two pathways. For example, caspase-8 can cleave Bid to tBid, which encourages permeabilisation of the mitochondria.33

Nevertheless, a lot of malignancies create defences against apoptosis by mutating death receptor signalling, losing pro-apoptotic proteins (such as p53 and Bax), or upregulating anti-apoptotic proteins (like Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL).34 Alternative types of PCD become crucial in these situations. The receptor-interacting protein kinases RIPK1 and RIPK3, as well as the mixed lineage kinase domain-like (MLKL) pseudokinase, are responsible for necroptosis, a type of controlled necrosis.35 Necroptosis is a pro-inflammatory process because, in contrast to apoptosis, it results in the rupture of the plasma membrane and the release of intracellular DAMPs.36 When caspase activity is decreased or RIPK1/RIPK3 expression is elevated, PDT has been demonstrated to induce necroptosis, offering a useful pathway to cell death in malignancies that are resistant to apoptosis.37

However, PDT can also trigger ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of non-apoptotic cell death characterised by the accumulation of lipid peroxides. System Xc− (cystine/glutamate antiporter), intracellular iron pools, and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) are the main controllers of ferroptosis.38 Inhibiting GPX4 activity, promoting lipid peroxidation, and overwhelming antioxidant defences are all ways whereby PDT-induced ROS, especially singlet oxygen, can cause ferroptotic cell death. The metabolic phenotype, iron load, and redox state of some cancer cells affect their susceptibility to ferroptosis, and PDT can alter these factors.39

When overactivated, autophagy, a lysosome-mediated degradation system, can function as a type of PCD or as a survival strategy in metabolic stress. Depending on the amount and location of oxidative damage, PDT can alter autophagic flux.40 While greater doses or specific lysosomal damage can result in faulty autophagy and cell death, moderate PDT doses may cause protective autophagy that postpones cell death. Furthermore, autophagy might affect the overall fate of cells by interacting with the pathways leading to necroptosis and apoptosis.41

The TME, which is crucial in determining therapy responses, is another important factor to take into account. By causing damage to the tumour vasculature, increasing vascular permeability, and upsetting the extracellular matrix, PDT-induced ROS can alter the TME. However, because PDT depends on molecular oxygen, tumour hypoxia—a typical characteristic of solid tumours—can reduce its effectiveness.42 The hypoxic tumour microenvironment, which restricts the effectiveness of traditional PDT due to oxygen dependence, has given rise to hypoxia-activated prodrugs (HAPs), a potential approach in PDT-based cancer phototherapeutics. Typically seen in solid tumours, HAPs are made to be inert in normoxic environments and preferentially activate in hypoxic ones. When hypoxia-responsive moieties such as nitroimidazoles, azobenzene, and quinones are included in photosensitiser frameworks, site-specific therapeutic effects and regulated activation are made possible. To increase ROS formation locally, nitroimidazole-conjugated porphyrin compounds, for instance, undergo bio-reduction under hypoxia to release the active photosensitiser. As demonstrated by azobenzene-linked BODIPY conjugates, azo-based linkers have been used to conceal photosensitizers or photosensitive medications that cleave reductively in low-oxygen settings.43–46 Additionally, quinone-based triggers in metal complexes, like photosensitisers based on Ir(iii) or Ru(ii), have been employed for hypoxia-activated phototoxicity with negligible off-target effects. For improved tumour accumulation, certain HAPs also add bio-reductive components to exosomes or nanocarriers. These clever designs provide a strong platform for treating aggressive and treatment-resistant tumours by enhancing PDT selectivity and safety while also enhancing combination therapies through synergistic chemo-photo effects.47–49

From a translational standpoint, a number of variables, such as the optimisation of photosensitiser pharmacokinetics, light delivery methods, dosimetry, and treatment timing, are critical to the clinical effectiveness of PDT.50 Although Photofrin and Foscan, two first- and second-generation photosensitisers, have shown promise in treating some types of cancer, they have drawbacks such as low tissue penetration, prolonged photosensitivity, and restricted tumour selectivity.51,52 To improve therapeutic precision, third-generation photosensitizers combine theranostic functions, stimuli-responsive release mechanisms, and tumour-targeting ligands.53 PDT is becoming more applicable to deep-seated tumours at the same time, thanks to developments in fibre-optic technology, light-emitting diode (LED) arrays, and upconversion nanoparticles.54,55

Key obstacles to the clinical translation of metal-based PSs for PDT include low photostability, prolonged systemic retention that results in photosensitivity, poor solubility, and decreased ROS generation in hypoxic tumour settings. PDT's efficacy is further limited by its poor tumour selectivity and limited light penetration. But transition metal complexes, particularly Ru(ii), Ir(iii), and Os(ii) molecules, have distinct benefits such as high ROS production, tunable photophysical characteristics, and activation under X-ray or near-infrared light.56–58 Targeted delivery and enhanced tumour accumulation are made possible by their capacity to undergo precise structural alterations. In order to improve systemic anticancer effects, emerging techniques concentrate on creating intelligent, tumour-activated PSs and combining PDT with immunotherapy. The increasing potential of metal-based PDT agents is demonstrated by clinical candidates such as purlytin, lutrin/antrin, TOOKAD soluble, and most notably TLD-1433 (a Ru(ii) complex in trials). With these advancements, PDT will no longer be a localised treatment but rather a potent tool that may treat metastatic malignancies more precisely and with fewer adverse effects.59,60

In conclusion, photodynamic therapy is a flexible and multidimensional approach to cancer treatment that can activate the immune system and specifically trigger a variety of pathways leading to programmed cell death. The interaction of subcellular targets, PDT-induced ROS, and PCD molecular regulators determines the treatment result and offers several avenues for intervention. In addition to helping to improve current PDT techniques, a better knowledge of these systems will open the door for the logical development of combination therapies that take advantage of weaknesses in the machinery that kills cancer cells. With a focus on the mechanistic diversity, therapeutic implications, and future options for incorporating PDT into contemporary cancer treatment paradigms, this study attempts to provide a thorough analysis of the state of PDT-induced PCD.

2. ROS-regulated programmed cell death pathway

2.1. Apoptosis

2.1.1. Apoptotic pathways and regulation

Apoptosis, a closely controlled and designed type of cell death, is essential for preserving cellular homeostasis and getting rid of damaged or dangerous cells, particularly ones that have the potential to cause cancer. Because it acts as a natural defence against carcinogenesis, apoptosis is very important in the study of cancer biology. But cancer cells often have the capacity to avoid death, which leads to the growth of tumours, resistance to treatment, and unfavourable clinical results. The intrinsic (mitochondrial) and extrinsic (death receptor-mediated) signalling routes are the two main ways that apoptosis occurs. Both pathways lead to the activation of executioner caspases, which coordinate the methodical breakdown of cellular constituents.61

The Bcl-2 protein family controls MOMP, which is the main regulator of the intrinsic pathway. MOMP and the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondrial intermembrane gap into the cytosol are promoted by pro-apoptotic members like Bak and Bax.62 After cytochrome c, caspase-9, and apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 (Apaf-1) form the apoptosome, downstream effector caspases, including caspase-3 and -7, are activated. Anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, on the other hand, prevent this process and increase cell survival.63

On the other hand, extracellular death ligands like Fas ligand (FasL), tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) link to their corresponding transmembrane death receptors (Fas, TNFR1, DR4/DR5) to start the extrinsic route.64 The death-inducing signalling complex (DISC), which is created as a result of this ligand–receptor interaction, attracts and activates initiator caspase-8.65 By cleaving the BH3-only protein Bid into its truncated version (tBid), which translocates to mitochondria and activates MOMP, activated caspase-8 can either directly cleave and activate effector caspases or enhance the apoptotic signal, connecting the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways (Fig. 2).66

Fig. 2. Schematic representation of apoptotic cell death pathways.

2.1.2. Apoptotic pathways induction through photodynamic therapy

PDT induces apoptosis by generating singlet oxygen (1O2) and other ROS upon light activation of photosensitizers. These ROS cause oxidative damage to vital cellular macromolecules—including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids—leading to programmed cell death. The PS's chemical makeup and subcellular location, the amount of light used, and the oxygenation level of the TME are some of the variables that affect the apoptotic response to PDT.67

PSs that target mitochondria, such as Photofrin, Verteporfin, and Foscan, have shown great effectiveness in triggering intrinsic apoptosis by triggering cytochrome c release, mitochondrial depolarisation, and MOMP in response to light activation. As a result, the intrinsic caspase cascade is activated, and the apoptosome is assembled. Furthermore, oxidative stress brought on by PDT can suppress anti-apoptotic proteins like Bcl-2 and survivin, increase the expression of pro-apoptotic proteins like Bax, Bak, and p53, and alter signalling pathways like mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), all of which contribute to the apoptotic result. Notably, PDT can also trigger the extrinsic route by increasing the expression of death receptors and their ligands, such as Fas and TRAIL-R, or by making cancer cells more susceptible to receptor-mediated apoptosis through receptor clustering and membrane remodelling brought on by ROS.68

Crucially, PDT's capacity to trigger apoptosis in a regulated and immunologically advantageous way offers therapeutic benefits for the treatment of cancer. In contrast to necrosis, which frequently causes inflammation and collateral tissue damage, apoptosis is immunologically silent or even immunogenic in some circumstances, particularly when damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as calreticulin, HMGB1, and ATP are released. By encouraging dendritic cell maturation and cytotoxic T lymphocyte activation, these compounds can improve anti-tumour immunity. Furthermore, PDT's selectivity for cancerous cells over healthy tissues reduces systemic toxicity due to selective PS accumulation and localised light activation. Cancer is characterised by resistance to apoptosis, which is frequently caused by p53 mutations, overexpression of anti-apoptotic proteins, or downregulation of death receptors.69

However, by concurrently activating several pro-apoptotic pathways and altering the tumour microenvironment, PDT presents a viable method to get past this resistance. For example, by reactivating p53-independent apoptotic pathways or downregulating Bcl-2 expression, PDT has been demonstrated to restore apoptosis sensitivity in resistant cancer morphologies.70 All things considered, PDT's pro-apoptotic mechanisms offer a complex and effective way to destroy tumour cells while protecting the surrounding healthy tissues, which makes it a useful supplement or substitute for traditional cancer treatments. The development of novel PSs with enhanced tumour selectivity, deeper tissue penetration, and subcellular targeting capabilities, as well as combinatorial strategies that combine PDT with apoptosis-sensitising agents, immune checkpoint inhibitors, or traditional chemoradiation, are ongoing research efforts to further improve PDT's apoptotic efficacy.71

2.1.3. Photosensitizer inducing apoptosis via PDT

Cyclometalated iridium(iii) complexes are strong photodynamic agents that, after being activated by light, cause apoptosis by a carefully planned series of intracellular processes. Therefore, it is a hot topic among researchers who want to create phototherapeutics that can destroy tumour cells. Mono-metallic and Bi-metallic iridium complexes using ligands with extended conjugation were designed and synthesized by Miao Zhong et al. (1), Shu-fen He et al. (2), Qin Zhou et al. (3), Jing Hao et al. (4), Wenlong Li et al. (5), Zheng-Yin Pan et al. (6), Rui Tu et al. (7), Zanru Tan et al. (8), Elisenda Zafon et al. (9) and, Li-Zhen Zeng et al. (10). The potency of these complexes as apoptosis inducing phototherapeutics were investigated. These metal complexes are mostly cationic in nature, thus making them specific towards mitochondria (Table 1).72–81

Table 1. Cyclometalated iridium III complexes inducing apoptosis via photodynamic therapy.

| Sl. no. | Cyclometalated iridium(iii) complex | Cancer cell lines | IC50 (light) | Apoptosis mechanism | Localisation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | HepG2 | 4.4 ± 0.7 μM | Mitochondrial disruption and Trx inhibition | Mitochondria | 72 |

| 2 | 2 | HeLa | 0.83 ± 0.06 μM | Mitochondria-membrane disruption and PI3K/AKT signaling pathway | Mitochondria | 73 |

| 3 | 3 | A549 | 2.23 ± 0.08 μM | Decrease in MMP, caspase, and Bcl-2 regulation | Mitochondria | 74 |

| 4 | 4 | SGC-7901 | 0.6 ± 0.1 μM | Mitochondrial dysfunction, Ca2+ level regulation, decrease in ATP levels | Mitochondria | 75 |

| 5 | 5 | A549 | 0.2 ± 0.05 μM | Mitochondrial injury and lipid peroxidation | Mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum | 76 |

| 6 | 6 | MDA-MB-231 | 0.26 μM | Mitochondrial disruption and ER stress | Mitochondria | 77 |

| 7 | 7 | HeLa | 1.8 μM | Mitochondria-membrane disruption and ROS generation | Mitochondria | 78 |

| 8 | 8 | A549 | 24.0 nM | Mitochondrial disfunction and ROS generation | Mitochondria | 79 |

| 9 | 9 | PC-3 | 2.4 ± 1.4 μM | Decreasing MMP and NADH oxidation, and DNA photocleavage | Mitochondria | 80 |

| 10 | 10 | A549 | 0.426 ± 0.041 μM | Caspase activation, GSH depletion and lipid peroxidation | Mitochondria | 81 |

| 11 | 11 | HCT116 | 30.93 nM | Decrease in MMP, pro-apoptotic gene activation, and caspase activation | Mitochondria | 82 |

| 12 | 12 | HCT116 | 0.1095 ± 1.2 μM | DNA fragmentation and cellular blebbing | Lysosomes and mitochondria | 83 |

| 13 | 13 | MDA-MB-231 | 5.31 μM | Cytochrome C release and caspase activation | Mitochondria | 84 |

| 14 | 14 | MCF-7 | 10 ± 1.90 μM | Proapoptotic protein activation and mitochondrial membrane damage | Mitochondria | 85 |

| 15 | 15 | A549R | 0.83 ± 0.10 μM | ROS accumulation and mitochondrial membrane potential depolarisation | Mitochondria | 86 |

| 16 | 16 | A549 | 0.23 ± 0.08 μM | ROS accumulation, MMP depletion, and caspase activation, | Mitochondria | 87 |

| 17 | 17 | HeLa | 0.00070 ± 0.0002 μM | NADH oxidation, DNA damage and mitochondrial damage | Mitochondria | 88 |

| 18 | 18 | A549 | 11.0 ± 0.4 μM | Elevated pro-apoptotic Bax protein and Cyt C release and downregulation of Bcl-2 | Mitochondria | 89 |

| 19 | 19 | HepG2 | 0.5 μM | ROS damage to mitochondria | Mitochondria | 90 |

| 20 | 20 | Hep G2 | 1–10 μM | Cytochrome C release and NADH photo-oxidation | Mitochondria | 91 |

| 21 | 21 | A375 | 1.1 ± 0.4 μM | MMP depletion, ROS generation | Mitochondria | 92 |

When these complexes are exposed to radiation, they change into an excited triplet state and release energy to molecular oxygen, producing reactive oxygen species (ROS), especially singlet oxygen (1O2). The ROS build up in cancer cells, particularly in subcellular organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum, lysosomes, or mitochondria, depending on where the complex is located within the cell. When mitochondria-targeting iridium(iii) complexes damage mitochondrial membranes oxidatively, pro-apoptotic substances, including cytochrome c, are released into the cytosol, and mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) is lost. The cell enters apoptosis, which is marked by chromatin condensation, membrane blebbing, and DNA breakage, when this release triggers initiator caspase-9, which in turn triggers executioner caspases such as caspase-3 and -7. Further sensitising the cells to apoptosis, these complexes can also downregulate anti-apoptotic proteins (like Bcl-2) and upregulate pro-apoptotic proteins (like Bax). These complexes can selectively kill cancer cells by apoptosis while reducing off-target toxicity because they can accurately control ROS formation both geographically and temporally with light.

A prospective therapeutic target, myeloid cell leukaemia-1 (Mcl-1) is an antiapoptotic oncoprotein that is overexpressed in a variety of malignancies. Even though there are several small-molecule Mcl-1 inhibitors, it is still difficult to distribute them precisely. Using the location of Mcl-1 on the outer mitochondrial membrane, a series of mitochondria-targeting luminous cyclometalated iridium(iii) prodrugs were created by Tejal Dixit et al. (11), containing Mcl-1 inhibitors via ester linkage. According to mechanistic research, 11 quickly builds up in mitochondria and is triggered by overexpressed esterase, which releases two cytotoxic agents: the ROS-generating iridium(iii) complex and the Mcl-1 inhibitor (I-2). Through cell cycle arrest and the mitochondria-mediated route, this dual action causes the depolarisation of the mitochondrial membrane and initiates apoptosis. Significant morphological alterations and a decrease in tumour growth in 3D multicellular tumour spheroids of HCT116 cells further demonstrated the compound's effectiveness.82

A possible approach to next-generation PDT with increased efficacy and fewer adverse effects is organelle-targeted PSs. Twelve of the cyclometalated iridium(iii) complexes that were synthesised and characterised by Monika Negi et al. (12), which demonstrated outstanding photophysical characteristics, such as a long photoluminescence lifetime and a high singlet oxygen quantum yield. When exposed to blue light (456 nm), 12 effectively produces hydroxyl and singlet oxygen radicals, which cause cancer cells to undergo apoptosis. It causes considerable cytotoxicity (PI > 400) and morphological disruption in 3D tumour spheroids, particularly accumulating in mitochondria and lysosomes. The effectiveness of PDT is increased by this dual organelle targeting through type I/II mechanisms.83

The majority of Ir(iii)-based photosensitisers are mononuclear, although little is known about binuclear systems. Nishna Neelambaran et al. introduced a dinuclear Ir(iii) complex (13) containing 2-(2,4-difluorophenyl)pyridine and 4′-methyl-2,2′-bipyridine ligands. 13 showed much better photoluminescence quantum yield (Φp = 0.70) and singlet oxygen generation (Φs = 0.49). Additionally, 13 demonstrated significant photocytotoxicity and robust cellular uptake against MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Without the need for further targeting moieties, its dual positive charge promoted intrinsic mitochondrial localisation. Si-DMA staining, annexin V-FITC/PI flow cytometry, cytochrome c release, and NaN3 inhibition tests were used to confirm ROS-induced apoptosis. This demonstrates how effective image-guided photodynamic therapy can be with 13.84

To meet their high energy needs for development and metastasis, cancer cells mostly rely on mitochondria. Cyclometalated iridium(iii) probes were created by Chandana Reghukumar et al. (14) to target this susceptibility. In MCF-7 breast cancer cells, 14 showed better photosensitising efficacy and less dark toxicity. Its positive charge and intense red fluorescence (colocalization coefficient = 0.90) facilitate mitochondrial targeting. When 14 is activated by light, it produces singlet oxygen (ΦΔ = 0.79), alters the potential of the mitochondrial membrane, hinders respiration, and causes death. SERS analysis and Annexin V staining were used to validate these effects. 14 is therefore a powerful theranostic agent that combines both fluorescence and Raman-based imaging capabilities with laser-activated mitochondrial damage.85

After synthesising and comprehensively characterising four iridium(iii) complexes, 15 was shown to be a promising photosensitiser by Kai Xiong et al., that targets mitochondria because of its high singlet oxygen production and precise mitochondrial localisation. While 15 showed little toxicity to normal HLF cells, it showed strong phototoxicity to A549 lung cancer cells and their cisplatin-resistant version, A549R. Because cancer cells internalise more of the complex, this selective cytotoxicity is explained by differential cellular absorption. 15 efficiently overcame drug resistance in A549R cells by inducing mitochondria-mediated apoptosis upon 405 nm light irradiation. These results demonstrate 15's potential as a targeted photodynamic treatment agent for resistant cancer types, providing a method to kill cancer cells only while leaving healthy tissues intact.86

Complexes of cyclometalated iridium(iii) have a lot of potential as metallodrugs to treat cancer. The anticancer potential of three phosphorescent complexes that target mitochondria was assessed by Yi Li et al. (16) in this investigation. IC50 values for all three examined cancer cell lines ranged from 0.23 to 5.6 μM, indicating much higher antiproliferative action than cisplatin. Their preponderance in mitochondria was confirmed by colocalization tests. According to mechanistic studies, these complexes cause mitochondrial malfunction, which is manifested by apoptosis, increased intracellular ROS levels, and depolarisation of the mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). According to these results, all the complexes are potent candidates for the creation of next-generation anticancer treatments because they appear to cause cytotoxicity by interfering with mitochondrial integrity and redox equilibrium.87

Carlos Gonzalo-Navarro et al. (17) coordinated π-expanded ligands to Ir(iii) half-sandwich complexes to enhance excited-state lifetimes and promote 1O2 generation. Derivatives of the form [CpIr(C∧N)Cl] and [CpIr(C∧N)L]BF4 were synthesised, with greater π-expansion leading to higher phototoxicity (PI > 2000) and notable activity under red light (PI = 63). TD-DFT calculations supported the effect of π-expansion. These complexes induce reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, mitochondrial membrane depolarisation, DNA cleavage, NADH oxidation, and lysosomal damage, triggering apoptosis and secondary necrosis. This work introduces the first class of half-sandwich iridium cyclometalated complexes for effective PDT.88

The anticancer potential of four neutral cyclometalated iridium(iii) dithioformic acid complexes was evaluated by Yuting Wu et al. (18). Assays for toxicity showed remarkable effectiveness, especially when used against human non-small cell lung cancer (A549) cells. 18 displayed potent anticancer action (IC50 = 11.0 ± 0.4 μM), was almost twice as effective as cisplatin, and successfully stopped A549 cell migration. These complexes specifically targeted mitochondria, resulting in apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, increased intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). According to Western blot examination, apoptotic signalling cascades were triggered by the considerable release of cytochrome c (Cyt-c), the elevation of pro-apoptotic Bax, and the downregulation of Bcl-2. When taken together, these results demonstrate their many uses in cancer treatment, including as apoptotic induction, anti-metastatic action, and mitochondrial imaging.89

Because of their unique photophysical characteristics, cyclometalated iridium(iii) complexes are great options for applications like fluorescent lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) probes and photosensitisers. For FLIM-guided photodynamic treatment (PDT), a novel iridium(iii) complex, with aggregation-induced emission (AIE) properties, was created by Dandan Chen et al. (19) in this work. Variations in fluorescence lifetime showed that 19 was highly sensitive to changes in mitochondrial viscosity. In the near-infrared spectrum, it also demonstrated advantageous multiphoton absorption (two-photon: 700–800 nm; three-photon: 1150–1450 nm). Notably, FLIM allowed for real-time monitoring of changes in mitochondrial viscosity during PDT. This study demonstrates how 19 can be used as a therapeutic agent and a diagnostic tool, allowing for self-reporting PDT responses and accurate detection of cellular microenvironmental alterations.90

As a hydride donor, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-reduced (NADH) is essential for preserving cellular equilibrium. To identify endogenous NADH levels, a quinoline-appended iridium complex is presented in this work by Shanmughan Shamjith et al. (20) as a dual-mode molecular probe for both fluorescence and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS). 20 has detection limits of 25.6 nM (fluorescence) and 15 pM (SERS) after undergoing a NADH-triggered switch that turns on luminescence (turn-ON) and turns off SERS signals (turn-OFF). The energy barrier for the hydride transfer from NADH to 20, which forms N-20, is 19.7 kcal/mol, according to density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Furthermore, by preventing photoinduced electron transfer (PeT), N-20 acts as a photosensitiser, producing singlet oxygen and NAD radicals. This makes it an effective tool for multiphase photodynamic treatment and NADH sensing.91

Zanru Tan et al. (21) created a series of dinuclear cyclometalated Ir(iii) complexes as photodynamic anticancer drugs that work with two photons. These complexes selectively accumulate in mitochondria and show significant two-photon absorption (2PA) cross-sections (σ2 = 66–166 GM). Notably, 21 displayed a phototoxicity index (PI) of 24 and an IC50 of 2.0 μM. 21 efficiently generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) when excited by two photons, causing damage to the mitochondria and the death of cancer cells. To improve 2PA for PDT applications, this study demonstrates how dinuclear complexes with conjugated planar bridges can significantly increase optical characteristics (Fig. 3).92

Fig. 3. Selective cyclometalated Ir(iii) complexes which trigger apoptosis as phototherapeutics.

2.2. Ferroptosis

2.2.1. Ferroptotic pathways and regulation

In 2012, the research group of B. Stockwell discovered a new cell death modality selectively triggered by the oncogenic RAS selective lethal small molecule, elastin. This cell death modality was named ferroptosis. The term “ferroptosis” is derived from the Greek word “ptosis” (falling) and the Latin word “ferrum” (iron).93 Ferroptosis represents a controlled necrotic cell death pathway that primarily triggers oxidative alterations in phospholipid membranes linked to iron concentration in the microenvironment. Ferroptosis can be distinctly identified from other conventional cell death pathways due to its notable morphological, biochemical, and genetic traits.94 Several ferroptosis inhibitors are known to exist, including ferrostatin 1, liproxstatin-1, an inhibitor of ROS and lipid peroxidation, and deferoxamine, an iron chelator. Ferroptosis is morphologically defined by outer mitochondrial membrane rupture, decreased or absent mitochondrial cristae, and shrinkage of the mitochondria with increasing membrane density. There is no chromatin condensation or margination, and the nucleus size is constant. Ferroptosis is associated with cellular shrinkage and the emergence of homogeneous circular protrusions of the plasma membrane, along with a gradual loss in its elasticity, according to recent atomic force microscopy investigations conducted in murine fibrosarcoma L929 cells. The cytoskeleton is unaffected, and membrane blebs are discernible even if surface roughness forms in the early phases of ferroptosis.95 A recent review found that ferroptosis is controlled by several genes, mostly associated with iron homeostasis and lipid peroxidation metabolism (e.g., GPX4, TFR1, SLC7A11, NRF2, NCOA4, P53, HSPB1, ACSL4, FSP1). The hunt for the new, specialised ferroptosis activator genes continues to linger on, though.96 Ferroptosis was first identified biochemically as being associated with inhibition of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) or blocking of the cystine/glutamate antiporter (system Xc). The activity of system Xc, a heterodimer composed of the SLC7A11 and SLC3A2 subunits, ordinarily distributes cystines and holds the cellular antioxidant environment in check, inhibiting the buildup of ROS. A selenium protein named GPX4 is essential for lipid peroxide detoxification and for reducing the detrimental effects of phospholipid peroxidation inducers.97 As the system is compromised or GPX4 levels are reduced, the antioxidant cysteine–glutathione (GSH) metabolism is exhausted. Accordingly, lipid peroxides are incapable of being metabolised, and Fe2+ oxidises lipids through the Fenton reaction, which causes the production of extremely detrimental lipid peroxides and the death of cells. Therefore, a key element in regulating ferroptotic processes is the intricate interaction between lipid, iron, and cysteine metabolism.98 Lipid peroxides have been proposed to be a crucial indicator of ferroptosis; the more lipid peroxides are present within the cell, the greater the extent of ferroptosis is observed. Other known inducers of ferroptosis include the small molecule compound Ras selective lethal 3 (RSL3), which inactivates GPX4, FIN56, which triggers ferroptosis and promotes GPX4 degradation whilst plummeting the level of the antioxidant CoQ10, and FINO2, which directly oxidises iron and indirectly inhibits GPX4 enzymatic function, contributing to widespread lipid peroxidation.99

2.2.2. Ferroptotic pathways induction through photodynamic therapy

The ability of PDT to cause ferroptosis in tumour cells has been demonstrated by mounting data in recent years, providing a viable avenue for improving anticancer efficacy. 5-Aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) is one prominent example. It has shown strong anticancer effects in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) models, notably in BALB/cAJcl-nu/nu mice that have had KYSE30 cells subcutaneously implanted. Mechanistic studies showed that 5-ALA-mediated PDT contributes to the buildup of lipid peroxides and oxidative stress in tumour cells by downregulating important ferroptosis-suppressing proteins, such as glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) and heme oxygenase 1 (HMOX1). The development of third-generation PSs and attempts to use PDT to induce ferroptosis have grown intimately related. These next-generation PS platforms include PSs coupled with targeting moieties like sugars, monoclonal antibodies, or peptides, PSs encapsulated within liposomes, and nanocomplexes and nanocarriers designed to include PSs alongside chemotherapeutic drugs. These nanostructures' synthesis and design are very beneficial since they overcome several drawbacks of traditional PDT. These nano-constructs primarily improve tumour selectivity and reduce off-target cytotoxicity by increasing the targeted distribution of therapeutic drugs and PSs to tumour cells.27,100

Importantly, these systems can include PSs that absorb in the 600–1000 nm NIR region, which enables more effective light activation of the PS and deeper tissue penetration. This ability minimises phototoxic effects on nearby healthy tissues by allowing a decrease in PS dosage without compromising therapeutic efficacy. Furthermore, the co-administration of pharmaceutical drugs via nano-platforms not only speeds up the induction of cell death but also stimulates strong antitumor immune responses, which are crucial for eradicating remaining tumour cells and stopping the spread of the disease. Within this context, oxygen-enhanced PDT is a particularly novel method that aims to address a significant obstacle to effective PDT: the hypoxic nature of solid tumours. These oxygen-augmented platforms contain elements that can increase local oxygen levels in the tumour microenvironment, which increases the production of ROS when exposed to radiation. Ferroptotic cell death is greatly increased by the oxidative stress that follows. Crucially, increased interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) release indicates that this oxygen-rich environment encourages T cell infiltration and activation. Ferroptosis is exacerbated by the cytokine-induced downregulation of SLC3A2 and SLC7A11, which are parts of the cystine/glutamate antiporter system Xc−. This further disturbs intracellular redox equilibrium.101

Moreover, photosensitisers alone or in combination with drugs that induce ferroptosis can be included into nano-constructs. These designs successfully induce ferroptosis in both configurations, highlighting their potential as therapeutics. But even with these developments, there are still major obstacles to overcome. Finding a careful balance between the danger of systemic iron-induced toxicity and efficient iron administration is a major challenge. Iron overloading tissues can cause oxidative damage that is not intended, while low iron availability can hinder the development of ferroptosis and reduce the effectiveness of treatment. Therefore, the ability of nano-constructs to maintain effective photodynamic reactions and promote robust ferroptosis must be given equal weight with their biocompatibility and tumour selectivity in the rational design of these structures. For ferroptosis-activating PDT techniques to be clinically translated and integrated into precision oncology paradigms, these design issues must be resolved.102

2.2.3. Photosensitizer inducing ferroptosis via PDT

An iridium(iii) complex that uses proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) to cause strong photoactivated cell killing was created by Jing Chen et al. (22). Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1), a canonical inhibitor of ferroptosis, efficiently inhibits the ferroptosis-like cell death mechanism that 22 activates upon light irradiation. However, conventional iron chelators and ROS scavengers do not affect this mechanism, which points to a nonclassical ferroptotic pathway. Using a polyunsaturated fatty acid model, mechanistic investigations showed that 22 directly stimulates lipid peroxidation (LPO) through a PCET-mediated mechanism. Studies on subcellular localisation revealed that 22 primarily builds up in the ER and mitochondria, where it causes ER stress, LPO buildup, mitochondrial enlargement, and the downregulation of GPX4, a crucial regulator of ferroptosis. Surprisingly, 22 retains its photocytotoxic effectiveness in hypoxic environments, and in vivo tests confirmed that it can effectively stop tumour growth when activated by a two-photon laser. To treat hypoxic and drug-resistant tumours, this study presents a unique paradigm in which photoactivated PCET promotes LPO and ferroptosis-like cell death, independent of both iron and oxygen.103

To improve therapeutic efficacy, Yu Pei et al. constructed a pH-responsive iridium–ferrocene combination (23) that cleverly takes advantage of the features of the TME. 23 dissociates in the acidic lysosomal environment after being internalised by cancer cells, avoiding the quenching of photoinduced electron transfer (PET) and increasing its brightness and photosensitising properties. 23 produces significant amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) under light irradiation via both type I and type II photodynamic processes. Notably, the complex's Fe2+ moiety catalyses Fenton reactions to create hydroxyl radicals (˙OH) when there is no light present. The Fe3+ produced during this process is then recycled back into Fe2+ by GSH-mediated redox cycling. Lipid peroxidation (LPO) and ferroptosis are the results of this enzymatic loop's substantial GSH depletion and ongoing ˙OH generation. PDT effectiveness is further increased by oxygen creation during Fenton reactions, which also reduces tumour hypoxia. Both photodynamic and ferroptotic effects are amplified when GSH depletion and TME oxygenation occur together. Studies conducted both in vitro and in vivo showed that 23 has strong anticancer efficacy and outstanding biocompatibility. All things considered, 23 is a multipurpose theranostic drug that can target lysosomes, activate in response to pH changes, and synergistically increase therapeutic effects, providing a potential method for accurate and successful cancer treatment.104

Using iridium hydrides, Xinyang Zhao et al. (24) created a unique iridium(iii) complex that is especially designed to trigger ferroptosis by targeting the mitochondria. Given that GPX4 plays a crucial role in controlling ferroptosis, the researchers purposefully included triphenylphosphine as a mitochondria-targeting moiety to improve the complex's transport to the mitochondrial compartment, where GPX4 is mostly found. To increase the complex's cytotoxic effects through ferroptotic pathways, 24, a ligand that induces ferroptosis, was also added to functionalise it. By dual inhibiting ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) and GPX4, two important negative regulators of ferroptosis, this Ir(iii) compound successfully triggered ferroptosis in human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells. Crucially, the complex also had fluorescent characteristics, which made it possible to follow its intracellular location in real time when excited by visible light (488 nm). This made it a useful tool for theranostic and mechanistic research. Furthermore, the 24 ligand's intrinsic toxicity was greatly decreased by its coordination to the Ir(iii) centre, improving the complex's overall biocompatibility and qualifying it for in vivo application. This work opens up new possibilities for the development of tailored cancer treatments with integrated diagnostic capabilities by presenting a viable approach for the design of mitochondria-targeted metallodrugs that cause ferroptosis.105

Xiangdong He et al. established a folate receptor-targeted Iridium complex (25) for PDT, which consists of three essential parts: a terminal folic acid ligand for tumour-specific targeting, polyethylene glycol (PEG) for self-assembly and solubility, and a cyclic Ir(iii) core. Cellular absorption studies have established that folic acid promotes selective accumulation in tumour cells overexpressing folate receptors, while the PEG moiety allows 25 to create stable, water-soluble nanoparticles. Under 420 nm irradiation, 25 shows a significant 1O2 quantum yield, causing oxidative stress that manifests as LPO buildup, glutathione (GSH) depletion, and GPX4 downregulation. Ferroptosis is brought on by these alterations taken together. In a mouse tumour xenograft model, the compound showed strong anticancer effects by a hybrid mechanism that combines ferroptosis and apoptosis. 25 is a viable option for clinical PDT applications due to its excellent therapeutic performance, tumour selectivity, and favourable biocompatibility.106

Lu Zhu et al. (26) created two chirality-dependent iridium(iii) phenyl quinazolinone complexes that inhibit FSP1 to cause ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Despite their structural similarities, the two enantiomers showed varied PDT responses and significantly differing ferroptosis-inducing capacities. Molecular simulations and proteomic investigations demonstrated that the l-isomer selectively binds to and inhibits metallothionein-1 (MT1), making cancer cells more susceptible to ferroptosis. A series of biological processes, including increased formation of ROS, lipid peroxidation, glutathione depletion, and FSP1 inactivation, were set off by this interaction. The d-isomer, on the other hand, only slightly increased ferroptotic activity. The study showed that the l-isomer may be produced efficiently via simple chiral resolution, allowing for precise regulation of ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. The promise of stereoselective ferroptosis inducers for focused and effective pancreatic cancer treatment is highlighted by these findings, which offer a fresh viewpoint on the use of chirality in the creation of metallodrugs.107

A hydrogen sulphide (H2S)-responsive iridium(iii) complex has been created by Yi Li et al. (27) as a cancer-selective ferroptosis inducer. Because of its high sensitivity and specificity for intracellular H2S, 27 can selectively activate H2S-rich cancer cells and make it easier to distinguish between malignant and healthy tissues in vitro and in vivo based on H2S content. The complex primarily builds up in mitochondria, where it intercalates into mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), seriously damaging it and impairing mitochondrial function. This impact is greatly amplified when exposed to light. Ferroptosis is brought on by 27-mediated PDT, which produces a lot of ROS and depletes GSH. This results in the buildup of LPO and the downregulation of GPX4. Additionally, the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS–STING) pathway is activated by substantial mtDNA damage. This leads to ferritinophagy and iron homeostasis disruption, which intensifies ferroptotic cell death in both in vitro and in vivo scenarios. 27-mediated PDT mostly affects genes linked to ferroptosis, autophagy, and cancer immunity, according to transcriptomic research using RNA sequencing. The first cancer-specific small-molecule photosensitiser that can both induce ferroptosis and activate the cGAS–STING pathway is presented in this work, providing a new paradigm for the creation of multipurpose, cancer-selective therapeutic agents that combine immune modulation and ferroptosis induction for increased anti-cancer efficacy.108

A cyclometalated Ir(iii) complex with a ferrocene moiety (28) was created by Yu-Yi Ling et al. This complex acts as a self-amplifying photosensitiser that can catalyse type I and type II PDT processes by producing ˙OH and 1O2. Through a robust association with apotransferrin (Apo-Tf), which is mediated by the overexpression of transferrin receptors (TfR) on MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, 28 demonstrates significant selectivity towards these cells. 28 effectively stimulates ferroptosis, lipid peroxidation, and peroxynitrite (ONOO−) production in both normoxic and hypoxic environments upon light activation. Interestingly, immunogenic cell death (ICD) is also triggered by 28-induced PDT, which improves ferroptosis-mediated cancer immunotherapy. Further in vivo research has shown that 28 can trigger systemic anticancer immune responses by suppressing distant tumours in addition to the main tumour growth. The applicability of complex 28 is restricted by its visible light excitation, which limits tissue penetration despite its encouraging therapeutic profile. The authors suggest methods include using two-photon excitation, adding ligands with extended π-conjugation, or combining upconversion nanomaterials or organic dyes with long-wavelength absorption to get over this restriction. All things considered, this work provides the first instance of a self-amplifying, small-molecule-based photosensitiser that can induce ferroptosis to enhance cancer immunotherapy, providing important information for the development of next-generation photoimmunotherapeutic drugs.109

Using a logical molecular design approach, Qing Zhang et al. designed a PDT agent based on a small-molecule iridium complex (29) to increase the production of ROS. They evaluated the capacity of 29 to transmit energy to molecular oxygen and generate triplet excited states by theoretical calculations, emphasising its favourable energy levels, high molar extinction coefficient, and effective oxidative potential. The photocytotoxicity of 29 was superior to that of traditional iridium-based photosensitisers (IC50 = 91 nM). Changes in intracellular ROS, GSH, malondialdehyde (MDA), LPO, and MMP further demonstrated that laser-activated 29 causes ferroptosis. Importantly, in order to show in vitro and in vivo that 29 promotes ferroptosis by decreasing GPX4, the researchers used CRISPR/Cas9-generated GPX4-knockout cells and GPX4-overexpressing cells. Interestingly, 29 also demonstrated strong anti-tumour activity and positive biosafety characteristics. The understanding of the mechanistic functions of photosensitizers based on iridium complexes in PDT is greatly advanced by this work (Fig. 4) (Table 2).110

Fig. 4. Illustration explaining the mode of action of photosensitizers for the induction of ferroptosis in cancer cells.

Table 2. Photosensitizers instigating various cell death pathways as cancer phototherapeutics.

| Sl. no. | Photosensitizer | Cell line | Photo-cytotoxicity | Cell death pathway | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22 | HeLa | 1.18 ± 0.51 μM | Ferroptosis | 103 |

| 2 | 23 | 4 T1 | <90% | 104 | |

| 3 | 24 | HT1080 | 7.48 μM | 105 | |

| 4 | 25 | HeLa | 12.66 ± 0.25 μM | 106 | |

| 5 | 26 | PANC-1 | 2.70 ± 0.11 μM | 107 | |

| 6 | 27 | HeLa | 1.45 ± 0.22 μM | 108 | |

| 7 | 28 | MDA-MB-231 | 0.05 ± 0.03 μM | 109 | |

| 8 | 29 | 4 T1 | 91 nM | 110 | |

| 9 | 30 | A549 | 0.93 ± 0.1 μM | Paraptosis | 118 |

| 10 | 31 | HepG2 | 1.6 μM | 119 | |

| 11 | 32 | MCF-7 | 0.86 μM | 120 | |

| 12 | 33 | Jurkat cells | 7–16 μM | 121 | |

| 13 | 34 | Jurkat cells | 0.4–7.2 μM | 122 | |

| 14 | 35 | Jurkat cells | 8.8–18 μM | 123 | |

| 15 | 36 | MDA-MB-231 | 4.6 ± 0.13 μM | Pyroptosis | 134 |

| 16 | 37 | MDA-MB-231 | 0.1 ± 0.06 μM | 135 | |

| 17 | 38 | U14 | 1.9 ± 0.3 μM | 136 | |

| 18 | 39 | 4 T1 | 7.1 μM | 137 | |

| 19 | 40 | MDA-MB-231 | 0.0200 ± 0.0006 μM | 138 | |

| 20 | 41 | A549 | 0.48 μM | Necroptosis | 150 |

| 21 | 42 | BEL-7402 | 0.47 ± 0.11 μM | 151 | |

| 22 | 43 | MV4- 11 | 1.69 ± 0.23 μM | 152 | |

| 23 | 44 | A549 | 1.94 ± 0.14 μM | 153 | |

| 24 | 45 | A549R | 2.2 ± 0.2 μM | 154 | |

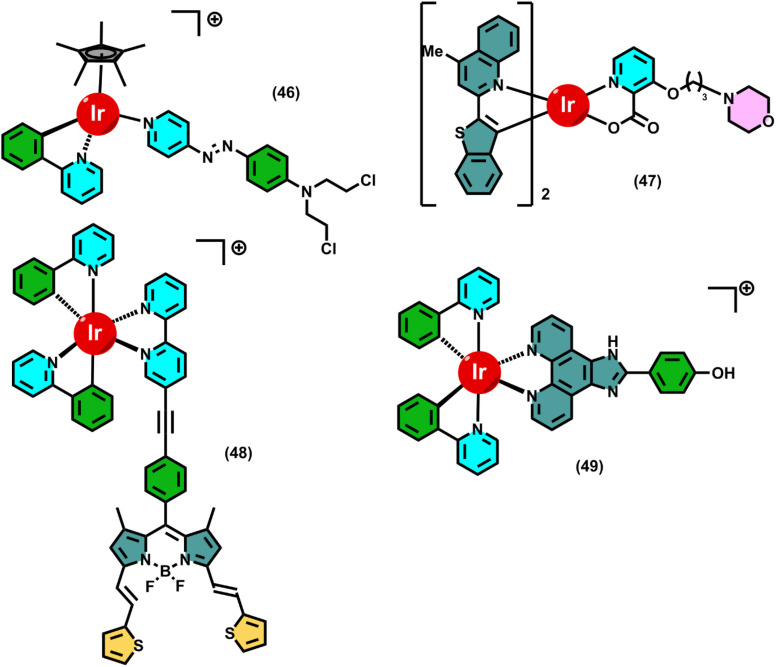

| 25 | 46 | A549 | 5.6 ± 0.4 μM | Autophagy | 163 |

| 26 | 47 | HeLa | 0.636 μM | 164 | |

| 27 | 48 | A549 | 0.7 μM | 165 | |

| 28 | 49 | EMT6 | 0.6 μM | 166 |

2.3. Paraptosis

2.3.1. Paraptotic pathways and regulation

Sperandio and colleagues coined the term “paraptosis” in 2000 to describe its unique features. They are “para-”, which means “beside” or “alongside”, and “-ptosis”, which means “falling” or “death” and is the same suffix as “apoptosis”. Because “paraptosis” literally means “a form of cell death simultaneous to apoptosis”, it is a distinct type of programmed cell death even if it employs a caspase-independent mechanism.111 Paraptosis is a non-apoptotic, caspase-independent kind of controlled cell death that differs from necrosis and apoptosis due to its distinct morphological and molecular characteristics. Unlike apoptosis, paraptosis does not exhibit the characteristics of DNA breakage, chromatin condensation, or apoptotic body formation. Instead, its most distinctive features are the lack of membrane blebbing, the progressive growth of the mitochondria and ER, and the notable cytoplasmic vacuolization. The non-acidic vacuoles produced during paraptosis have nothing to do with autophagic or lysosomal activity. They are mostly caused by the distension of the ER and, to a lesser degree, by the enlargement of the mitochondria.112

Paraptosis may be brought on by several events, including the activation of insulin-like growth factor receptor I (IGF-IR), the administration of particular phytochemicals (such as celastrol or curcumin), proteasome inhibitors, and medications that cause ER stress. Paraptosis is significantly influenced by mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling pathways, such as the JNK and ERK1/2 pathways. These signalling pathways allow both increased protein synthesis and ER stress, both of which are critical for vacuole development. Although cycloheximide and other inhibitors can halt the process, paraptosis also necessitates continuous protein translation, indicating a dependence on newly synthesised proteins that may accumulate and strain the ER.113

Mitochondrial dysfunction, including increased production of ROS and loss of MOMP, also affects how paraptosis is executed. Importantly, paraptosis is mechanically independent of apoptosis, as evidenced by the fact that it is not suppressed by pan-caspase inhibitors or conventional anti-apoptotic proteins like Bcl-2. The biological importance of paraptosis includes possible roles in neurological disorders and tumour suppression. It is particularly interesting in cancer therapy because it offers a mechanism to destroy cells that are resistant to apoptosis by initiating a distinct and irreversible death process.114

2.3.2. Paraptotic pathways induction through photodynamic therapy

Although it has long been believed that PDT primarily causes cell death by apoptosis, there is growing evidence that PDT can also cause other, non-apoptotic processes, like paraptosis. Paraptosis is a distinct kind of programmed cell death characterised by extensive cytoplasmic vacuolization, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) dilatation, mitochondrial swelling, and the absence of caspase activation, DNA breakage, or chromatin condensation.115

ROS-mediated oxidative stress, which jeopardises the structural and functional integrity of the mitochondria and the ER, is the primary mechanism by which PDT may induce paraptosis. The accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER causes ROS-induced ER stress and unfolded protein response (UPR) activation. When this stress surpasses the adaptive capacity of the cell, it results in ER dilatation and vacuole formation, which are characteristics of paraptosis. At the same time, mitochondrial dysfunction, which is marked by swelling and loss of membrane potential, exacerbates cellular stress and promotes paraptosis. Since paraptosis does not include caspase activation and is not inhibited by anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 or pan-caspase inhibitors, it is mechanistically distinct from apoptotic cell death.116

Furthermore, PDT-induced paraptosis requires ongoing protein synthesis, as seen by the inhibitory effects of translational blockers such as cycloheximide. A role in controlling stress responses and promoting vacuolization has also been suggested by the involvement of MAPK signalling pathways, specifically ERK1/2 and JNK. Importantly, PDT has a therapeutic advantage in treating cancers that are resistant to apoptosis because of its ability to induce paraptosis. PDT interacts with multiple cell death mechanisms, including paraptosis, to increase the overall efficacy of cancer treatments and offers a practical method for avoiding apoptotic resistance in malignant cells.117

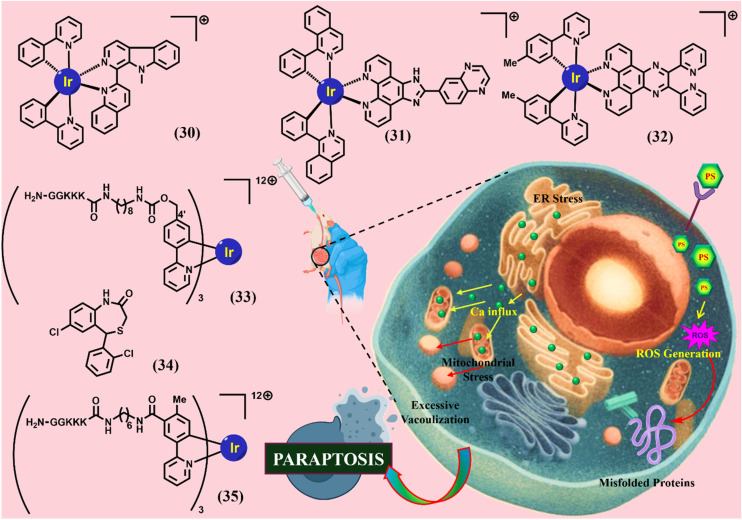

2.3.3. Photosensitizer inducing paraptosis via PDT

Four new cyclometalated phosphorescent Ir(iii) complexes were synthesized by Liang He et al. (30). These complexes display outstanding photophysical properties, including high luminescence quantum yields, long phosphorescence lifetimes, and two-photon excited phosphorescence. They display potent anticancer activity against human cancer cell lines tested. Cell imaging and ICP MS results show that they are preferentially accumulated in the mitochondria, probably due to their positive charge and lipophilicity. Anticancer mechanisms studies show that 30 possesses an entirely different mode of action from cisplatin. 30 induces mitochondria-derived cytoplasmic vacuolation associated with caspase-independent paraptotic cell death. 30 affects the UPS and MAPK signaling pathways, both of which have been reported to be associated with paraptosis. The complex disrupts the physiological functions of mitochondria severely and quickly, which are indicated by the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, reduction of cellular ATP production, mitochondrial respiration inhibition, and ROS elevation. The severe and rapid damage to mitochondria and the UPS results in the collapse of mitochondria and the subsequent cytoplasmic vacuolation before the cells are ready to start the mechanisms of apoptosis and/or autophagy. ROS inhibition assays further confirm that increased mitochondrial superoxide has a critical role in 30-induced cell death. In vivo studies have demonstrated the anticancer efficacy of 30. Overall, this work has identified caspase-independent non-apoptotic paraptosis as the major mode of cell death caused by 30, which is unique and may have potential in cancer treatment. Furthermore, this work also gives useful insights into the design and anticancer mechanisms of new metal-based anticancer agents.118

Immunotherapy has emerged as a highly effective strategy for cancer treatment by harnessing the innate immune system to selectively recognize and eliminate malignant cells while sparing normal tissues. Jiaxin Liao et al. designed and synthesized three novel cyclometalated iridium(iii) complexes and assessed for their antitumor properties (31). Upon co-incubation with HepG2 cells, 31 was found to accumulate in lysosomes, where it triggered paraptotic cell death and induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. Notably, 31 also elicited immunogenic cell death (ICD), which facilitated dendritic cell maturation, thereby enhancing the recruitment of effector T cells to tumor sites. Additionally, 31 downregulated the presence of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells within the tumor microenvironment and stimulated systemic antitumor immune responses. To date, 31 represents the first documented iridium(iii)-based complex capable of inducing paraptosis while concurrently promoting tumor cell ICD. Importantly, 31 achieved this without altering cell cycle progression or elevating ROS levels in HepG2 cells.119

Six mononuclear Ir complexes using polypyridyl pyrazine-based ligands and {[cp*IrCl(μCl)]2 and [(ppy)2Ir(μCl)]2} precursors have been synthesised and characterised by Tripathy et al. (32). The complexes have shown potent anticancer activity against various human cancer cell lines (MCF7, LNCap, Ishikawa, DU145, PC3, and SKOV3) while on of the complexes is found to be inactive. Flow cytometry studies have established cellular accumulation of the complexes the highest in 32, which is in accordance with their observed cytotoxicity. No changes in the expression of PARP, Caspase 9, and Beclin1, Atg12, discard apoptosis and autophagy, respectively. Overexpression of CHOP, activation of MAPKs (P38, JNK, and ERK), and massive cytoplasmic vacuolisation collectively suggest a paraptotic mode of cell death induced by proteasomal dysfunction as well as endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial stress. An intimate relationship between p53, ROS production, and the extent of cell death has also been established using p53 wild, null, and mutant type cancer cells.120

K. Yokoi et al. reported the design and synthesis of a green-emitting iridium complex-peptide hybrid (33), which has an electron-donating hydroxy acetic acid (glycolic acid) moiety between the Ir core and the peptide part. It was found that 33 is selectively cytotoxic against cancer cells, and the dead cells showed a green emission. Mechanistic studies of cell death indicate that 33 induces a paraptosis-like cell death through the increase in mitochondrial Ca2+ concentrations via direct Ca2+ transfer from ER to mitochondria, the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), and the vacuolization of cytoplasm and intracellular organelles. Although typical paraptosis and/or autophagy markers were upregulated by 33 through the MAPK signalling pathway, as confirmed by Western blot analysis, autophagy is not the main pathway in 33-induced cell death. The degradation of actin, which consists of a cytoskeleton, is also induced by high concentrations of Ca2+, as evidenced by co-staining experiments using a specific probe.121

The same group further described that (34), an inhibitor of a mitochondrial sodium (Na+)/Ca2+ exchanger, induces paraptosis in Jurkat cells via intracellular pathways similar to those induced by 33. The findings allow us to suggest that the induction of paraptosis by 33 and 34 is associated with membrane fusion between mitochondria and the ER, subsequent Ca2+ influx from the ER to mitochondria, and a decrease in the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm). On the contrary, celastrol, a naturally occurring triterpenoid that had been reported as a paraptosis inducer in cancer cells, negligibly induces mitochondria-ER membrane fusion. Consequently, we conclude that the paraptosis induced by 33 and 34 (termed as “paraptosis II” by the group) proceeds via a signalling pathway different from that of the previously known paraptosis induced by celastrol, a process that negligibly involves membrane fusion between mitochondria and the ER (termed as “paraptosis I” by the group).122

Once again, the same group conducted a detailed mechanistic study of cell death induced by (35), a typical example of iridium complex−peptide hybrids, and describe how 35 induces paraptotic programmed cell death like that of celastrol, a naturally occurring triterpenoid that is known to function as a paraptosis inducer in cancer cells. It is suggested that 35 (50 μM) induces ER stress and decreases the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), thus triggering intracellular signalling pathways and resulting in cytoplasmic vacuolization in Jurkat cells (which is a typical phenomenon of paraptosis), while the change in ΔΨm values is negligibly induced by celastrol and curcumin. Other experimental data imply that both 35 and celastrol induce paraptotic cell death in Jurkat cells, but this induction occurs via different signalling pathways (Fig. 5) (Table 2).123

Fig. 5. A graphical representation of how photosensitizers work to cause cancer cells to undergo paraptosis.

3. Inflammation-regulated programmed cell death pathways

3.1. Pyroptosis

3.1.1. Pyroptotic pathways and regulation

A unique, pro-inflammatory type of controlled cell death, pyroptosis, was first discovered in Shigella flexneri-infected macrophages and then in response to Salmonella typhimurium.124 Over time, pyroptosis has been linked to a variety of clinical situations, such as ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction, microbial infections, and different phases of cancer development. Numerous terms, including pyronecrosis, gasdermin-dependent cell death, and caspase-1-dependent cell death, have been used to describe this type of cell death.125 However, the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death has officially recognised the term “pyroptosis”, which was created by Cookson and Brennan in 2001 and is derived from the Greek words “pyro”, which means fire or fever, and “ptosis”, which means falling.126

Although it shares some characteristics with both necrosis and apoptosis, pyroptosis is distinguished from both by a combination of morphological and biochemical characteristics. At first, pyroptotic cells show signs of death, including chromatin condensation and DNA fragmentation. But these are followed by events that resemble necrosis, such as swelling of the cells, rupture of the membrane, and the consequent release of intracellular pro-inflammatory substances such as cytokines and DAMPs. Mechanistically, the activation of inflammatory caspases-most notably caspase-1, but also human caspases 4 and 5 and mouse caspase 11-is strongly linked to pyroptosis.127 Usually, the formation of multiprotein complexes called inflammasomes, which comprise adaptor proteins like ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD domain) and sensor proteins like NOD-like receptors (NLRP3, NLRC4), AIM2, and Pyrin, activates these caspases. Caspases-1 trigger strong inflammatory reactions by cleaving pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their mature, secretory forms when they are activated. The gasdermin family of proteins, especially gasdermin D (GSDMD), is a crucial pyroptotic executor. When the N-terminal segment of GSDMD is broken down by inflammatory caspases, it moves to the plasma membrane, where it oligomerizes and creates big, non-selective holes. By upsetting ionic gradients and allowing water to enter, these pores cause cellular lysis and swelling, which releases DAMPs and inflammatory cytokines into the extracellular environment.128

Pyroptosis can occur through a non-canonical pathway in addition to the canonical pathway driven by caspase-1. In this route, cytosolic lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from Gram-negative bacterial infections directly activate caspase-4 and -5 (in humans) or caspase-11 (in mice). GSDMD is also cleaved by these caspases, which promotes pore formation and cell death. Crucially, either directly or by activating secondary caspase-1, this mechanism also aids in the development of IL-1β and IL-18. Apoptotic caspase-3 and its association with gasdermin E (GSDME) constitute a third pathway. Cells expressing this gasdermin isoform undergo pyroptosis when caspase-3 cleaves GSDME under specific stressors. A point of confluence between apoptotic and pyroptotic pathways is highlighted by the caspase-3/GSDME axis, which is becoming more widely acknowledged as being important in chemotherapy-induced cancer cell death.129

In conclusion, pyroptosis is a complex and strictly controlled type of cell death that plays a vital role in the interaction between inflammation and innate immunity. Its distinctive characteristics—rupturing the plasma membrane, releasing inflammatory cytokines, and engaging gasdermin proteins—highlight its possible significance in immunogenic cell death, especially in cancer treatment. In the context of infectious disease, cancer, and inflammatory disorders, a better knowledge of the molecular regulators of pyroptosis may open the door to new therapeutic approaches that utilise or alter this process.130

3.1.2. Pyroptotic pathways induction through photodynamic therapy

Novel membrane-anchored photosensitisers (PSs) with aggregation-induced emission capabilities, such TBD-3C, have been developed recently in PDT. These PSs efficiently induce apoptosis and pyroptosis, with pyroptosis being the primary effect, in a variety of cancer cell lines, including 4 T1, HeLa, and C6. ROS-mediated caspase-1 activation, GSDMD cleavage, and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 are the hallmarks of this cell death.131 Similarly, pyroptosis in HepG2 cells has been demonstrated to be triggered by curcumin-loaded PLGA microbubbles in sono-PDT. A non-canonical pyroptosis mechanism, including downregulation of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), activation of caspase-8 and -3, and GSDME cleavage, was discovered through mechanistic studies of PDT utilising 5-ALA, protoporphyrin IX dimethyl ester, and chlorin e6 in esophageal squamous carcinoma cells. Pyroptosis was inhibited by overexpression of PKM2, indicating that it may be a therapeutic target to improve the effectiveness of PDT.132

Pyroptosis is still not well understood in PDT, despite its importance. There is good reason to look at pyroptosis as a powerful and immunogenic cell death pathway in tumours treated with PDT, since ROS plays a key role in both PDT and pyroptotic signalling. Although PDT-induced inflammation is advantageous for immune activation, it must be carefully controlled because too much cytokine synthesis, including IL-1β, might have detrimental effects. To keep this balance, the light dose and PS concentration must be optimised. All things considered, pyroptosis presents a viable path to improve PDT's immunological and therapeutic effectiveness, especially in malignancies that are resistant. The molecular regulators of this process and their potential in combination therapy should be better defined in future studies.133

3.1.3. Photosensitizer inducing pyroptosis via PDT

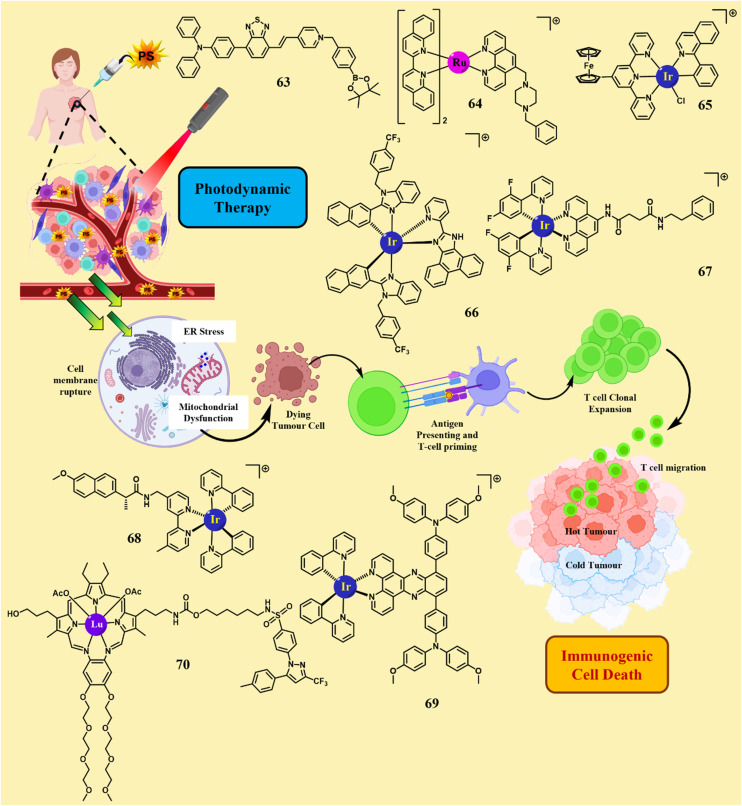

Recent developments in the realm of photoactive metal complexes have demonstrated their exceptional ability to combine immune activation and direct photodynamic tumour death through intricately coordinated mechanistic pathways, especially by triggering innate immune signalling and pyroptosis. By creating a cholic acid-modified iridium(iii) photosensitiser (36) that preferentially localised in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Yun-Shi Zhi et al. initially brought attention to this potential. Complex 36 experienced effective intersystem crossing at the Ir(iii) centre upon light irradiation, producing type I and type II ROS. The overabundance of ROS disrupted ER homeostasis, causing ER stress and GSDME cleavage-mediated pyroptotic cell death. Simultaneously, the complex caused the release of extracellular HMGB1, ATP secretion, and exposure to calreticulin (CRT), which are examples of traditional damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). These signals were essential for antigen presentation and dendritic cell maturation, which allowed for T cell activation and the in vivo destruction of primary and metastatic tumours.134

This strategy was furthered by Bin-Fa Liang et al. with cholic acid-modified ruthenium(ii) complexes (37), which had the same ER-targeting ability but, for theranostics, an unusual combination of singlet oxygen (1O2) production and near-infrared aggregation-induced emission (AIE) phosphorescence. By activating the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS–STING) pathway, ROS-mediated ER disruption by 37 mechanistically triggered the phosphorylation of TBK1 and IRF3, which in turn triggered the release of cytokines and type I interferon. This cascade produced strong in vivo antitumor immunity with an extraordinarily high phototoxicity index (PI = 83.3) by reinforcing pyroptosis and amplifying innate immune signalling. When combined, these investigations show that ER stress and ROS overproduction are important upstream triggers; however, the Ru(ii) systems took use of STING-mediated immune amplification, whereas the Ir(iii) complexes focused on DAMP-driven ICD.135

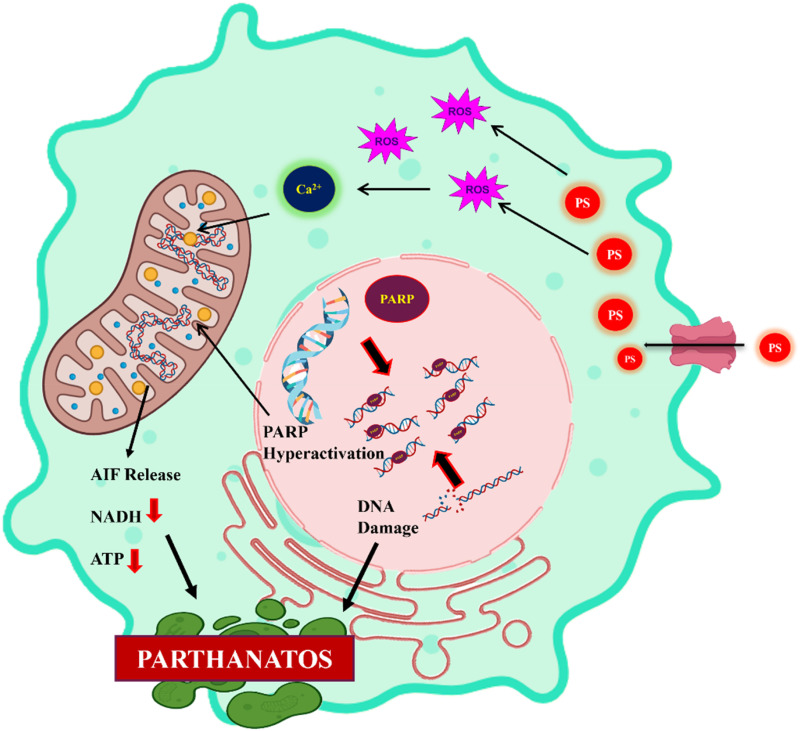

Going beyond Ir and Ru, Yu-Yi Ling et al. created Pt-based photosensitisers (38), which were intended to be the initial photoactivators of the cGAS-STING pathway. These Pt complexes, in contrast to ER-focused approaches, caused photoirradiation-induced damage to nuclear and mitochondrial DNA as well as the nuclear envelope. Cytosolic DNA fragments released by such genotoxic stress directly activated the cGAS enzyme, resulting in cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) and initiating downstream STING signalling. Innate immune sensing and immunogenic lytic death were integrated at the same time that ROS buildup and DNA damage caused pyroptotic cell death. Crucially, this dual method not only destroyed cancer cells but also enhanced robust adaptive immune responses, demonstrating that nuclear and mitochondrial targeting is a different but no less successful way to activate photo-immunotherapeutic immunity.136