Abstract

Background

Health utility measurement is critical for cost-utility analysis (CUA). However, clinical studies often lack direct utility data, and methods of measuring health utility vary across different periods and regions, resulting in missing utility information. Mapping, a method employed to infer utility when direct utility data is absent, has been widely applied in recent years but still faces challenges. This systematic review evaluates the current landscape, trends, and limitations of mapping studies and provides recommendations for improving study design and reporting standards.

Methods

A literature search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, and the HERC Database of Mapping Studies from 2018 to 2024. The study extracted information from the included studies and performed quality assessments based on existing mapping guidelines.

Results

One hundred thirty-one studies were included, 92 focused on Mapping as the primary objective, five were reviews, 13 focused on methodology, and 21 focused on economic evaluation. The source measure, target measure, and models in mapping functions development remain EORTC-QLQ-C30 (n = 13), EQ-5D (n = 79), and OLS (n = 93). Studies now use larger sample sizes and a higher proportion of response Mapping, and model applications have increased in diversity. However, 32 studies still lack conceptual overlap analysis, and only 16 studies with repeated measurements addressed its issue. Additionally, two studies did not report the region of the sample and value set, while 27 had inconsistencies between the two regions.

Conclusions

In the last seven years, mapping studies have improved sample size, model application, and result reporting. However, limitations remain in analysing conceptual overlap, ensuring alignment between the sample and value set regions, and processing repeated measurements. To advance the quality of mapping studies, it is necessary to update mapping guidelines and ensure that all mapping functions are developed in compliance with them.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12955-025-02426-3.

Keywords: Systematic review, Mapping, Utility, Crosswalking, Health-related quality of life, Patient-reported outcomes, Preference-based measures

Introduction

The allocation of medical resources is often guided by Health Technology Assessment (HTA), where cost-effectiveness analysis (CUA) is a commonly used economic evaluation method. In CUA, utility is frequently measured through Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALY) [1]. QALY combines Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) with life expectancy, calculated as the product of the Health State Utility Value (HSUV) and survival time. HSUV is determined using Preference-Based Measures (PBM), which assess HRQoL across dimensions such as physical function, pain, social function, and emotional well-being. PBM then calculates HSUV by applying a value set to the severity levels of each dimension [2]. Current PBM includes EuroQOL five dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D), Short form 6 dimensions (SF-6D), Health utility index Mark 3 (HUI-3), and Child health utility nine dimensions (CHU-9D), with EQ-5D and SF-6D being the most widely used [3]. However, most clinical studies do not use PBM to measure HSUV [4–6]. Instead, they frequently rely on disease-specific, non-preference-based Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) to gather data on effectiveness and other non-economic indicators [7]. Incorporating PBM can increase administrative time and costs, burdening researchers and participants. Additionally, different HTA agencies recommend various PBM depending on the period and region [5, 8, 9], and results can vary among PBM [2, 10–15]. Even for the same PBM, results may not be directly comparable due to differences in versions or value sets [1, 16–19]. Furthermore, PBM inconsistency or absence issues often arise when CUA involves clinical data across different times or regions. These factors contribute to gaps in the utility data required for CUA.

Mapping is a method for establishing a connection between the source and target measure, using a mapping function to estimate the target measure value based on existing measurements. This approach helps bridge the gap between available evidence and the information required for CUA [1, 5]. Mapping can also convert results from different PBMs into a single PBM, thus enhancing comparability [14]. This method, also known as "Cross-Walking" or "Transfer to Utility," is considered a suboptimal option when PBMs are missing in existing studies. It has recently been recommended by the Chinese Pharmaceutical Association [9] and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [20]. Between 2000 and 2019, 28.85% of HTAs conducted through the single technology appraisal (STA) process derived utility values through mapping [21]. Mapping is divided into direct and indirect methods. Direct mapping estimates the HSUV of the target measure directly from the source measure. In contrast, indirect mapping is a two-step process: the first step estimates the HRQoL for each dimension of the target measure based on the source measure, and the second combines these HRQoL with a value set to calculate the HSUV [1, 5]. Direct mapping does not require HRQoL for each dimension of the target measure, making it simpler to implement. However, the HSUV produced is based on a region-specific value set and omits detailed information on each dimension of the target measure. Although indirect mapping requires more comprehensive data, it allows for responses to each dimension of the target measure and, in the second step, can calculate HSUV according to region-specific value sets, resulting in a mapping function with broader applicability [18].

NICE, the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR), Oxford University, and the University of Sheffield have all published mapping guidelines [4, 22–24] to provide comprehensive guidance on various aspects of mapping studies. In addition to these four guidelines, Oxford University's Health Economics Research Centre (HERC) developed a mapping study database targeting EQ-5D and produced a related review [25]. However, recent reviews mostly focus on specific aspects of mapping studies, such as rare diseases [20], data relevance [26], and mapping from PROMIS-29 to EQ-5D [2], while neglecting to examine conceptual overlap as well as the consistency between the sample region and the value set region. Furthermore, The most recent systematic review inclusion date was October 2018 [1], which no longer reflects the current mapping studies state and needs updating.

Recently, extensive discussion has emerged concerning using QALY [27–29]. If QALY were to be replaced by a new metric, the mapping would facilitate a transition between QALY and the new metric, thus supporting economic evaluations of pharmaceuticals across different periods. In summary, mapping plays a crucial role in health economic evaluations when health utility evidence is lacking, making high-quality mapping practices an immediate priority. This systematic review aims to review recent mapping studies and analyse the current landscape of mapping research. It investigates the conceptual overlap and regional consistency between the sample population and value set that have been neglected in previous studies. The review seeks to reveal the latest developments and limitations in mapping research, providing recommendations for advancing high-quality mapping studies.

Methods

This systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (ID: CRD420250651687). It complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement and will be reported based on the PRISMA 2020 checklist.

Data sources and search strategy

The review searched three databases: PubMed, Web of Science, and the HERC Database of Mapping Studies [30], with searches finalized by December 31, 2024. The search strategy included multiple terms related to mapping, such as “mapp*,” “map,” “cross walk,” “crosswalk*,” and “transfer to utility,” combined with health preference-related keywords like “healthutilit*,” “QALY,” “quality of life,” “qol,” “health state utilit*,” “health state value,” “utility score,” “utility index,” “PBM,” “preference-based,” and “preference based.” PubMed and Web of Science searches were limited to subject headings and the Social Sciences index. The results from PubMed and Web of Science were merged with those collected from the HERC Database of Mapping Studies. Further details on the search strategy are provided in Additional file 1.

Inclusion criteria

The latest systematic review of Mapping included studies up to October 2018 [1]. This review only includes studies published after this date to analyse development trends in mapping studies and enable comparative analysis. After merging the results from the three databases and removing duplicates, three rounds of screening were conducted: title, abstract, and full text. At the title screening stage, studies were excluded if they were unrelated to quality of life, focused solely on analysing factors influencing quality of life, examined the structure or application of patient-reported outcome measures, or were scoping reviews. At the abstract screening stage, studies were excluded if they merely compared the structures of scales, investigated preferences, reported utility statistics, or presented outcomes that were not preference-based. Finally, at the full-text screening stage, outside the designated study period, CEA that did not derive utility values through mapping and studies solely seeking HSUV evidence was excluded. In order to offer a thorough analysis of mapping research, we include not only original studies on developing mapping algorithms but also relevant reviews, methodological studies, and economic evaluation applications.

Study selection

The studies screening process involved three reviewers. two reviewers (Q. S., Y. Z.) independently screened the studies, and after both completed their screenings, a third reviewer (L. S.) consolidated the results. Any discrepancies in the consolidated results were discussed with the other reviewers to reach a final consensus.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data was extracted from studies that focused on mapping as the primary objective. The research team extracted data from all eligible publications using a standardized extraction table, and two reviewers (Q. S., Y. Z.) independently extracted information from the included records. Three checklists and one technical support document guided the development of the extraction table and served as quality assessment criteria. These resources included the MAPS checklist [23], the ISPOR Good Practices for Outcomes Research report on “Mapping to Estimate Health-State Utility from Non-Preference-Based Outcome Measures” [4], the University of Sheffield’s mapping practice recommendations [24], and NICE’s mapping technical support document [31].

To comprehensively evaluate the reporting quality of Mapping studies, a set of 27 quality assessment criteria was developed based on the checklists and technical support documents. These criteria cover various aspects of mapping research, including the content of the title and abstract, sample characteristics, country, source and target measures, value sets, data processing, models, variables, validation, and external generalizability. Detailed quality assessment information is provided in Additional file 2. On this basis, to reflect the current state of mapping research, data was extracted on bibliographic details, source measures, target measures, sample size, the countries of the sample and value set, methods for assessing conceptual overlap, data processing methods, mapping approaches and models, covariates, and validation methods. Detailed extraction information is provided in Additional file 3.

Results

Studies included

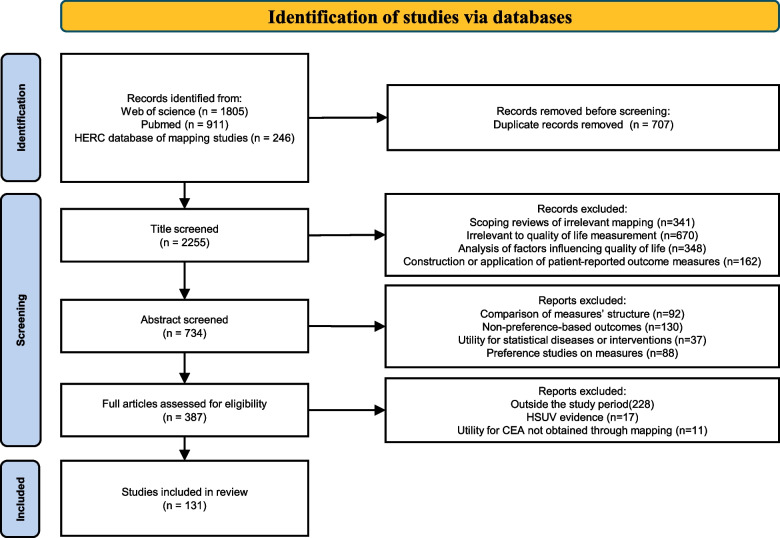

Figure 1 illustrates an overview of the search and selection processes. A total of 2962 studies were considered for this systematic review. After excluding 707 duplicates, 2255 studies remained. Following title screening, 1521 studies were excluded, leaving 734 studies. Subsequently, 347 studies were excluded based on abstract screening, resulting in 387 studies for full-text screening. After full-text assessment and chronological filtering, 131 studies were included in the final analysis [1, 2, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 19, 20, 26, 32–151].

Fig. 1.

Study selection flowchart

Among the 131 studies, 92 focused on Mapping as the primary objective, 21 on economic evaluation, 13 on methodology, and five reviews. Among the reviews, one study examined the impact of repeated measurements on mapping and found that repeated measurements can lead to underestimating standard errors. Another review focused on mapping in rare diseases, revealing that such studies generally have small sample sizes, and the floor effect associated with the severity of rare diseases may compromise prediction accuracy. Three additional reviews were conducted, one analysing the mapping from PROMIS-29 to EQ-5D, one Summarizing Mapping studies of PROMs used in hip, knee, and shoulder replacement Surgeries, and another reviewing Mapping studies published between January 2007 and October 2018.

Among the 13 studies focused on methodology, six examined Mapping models, two focused on the selection and application of value sets, two addressed issues related to sample size and data processing, and the remaining 3 validated the reliability of Mapping. The 21 economic evaluation studies covered disease areas including nervous system diseases (n = 5), musculoskeletal and connective tissue diseases (n = 6), male reproductive system diseases (n = 3), respiratory diseases (n = 1), endocrine, nutritional, and metabolic diseases (n = 1), and complications and related care during pregnancy, childbirth, and the puerperium (n = 1).

Source and target measure

In a review of 92 studies focused on Mapping as the primary objective, 13 studies (14.13%) utilized multiple source measures, while 17 studies (18.48%) employed various target measures. By treating each target measure individually as a separate Mapping function, there are 113 mapping functions in total (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mapping functions information statistics

| Target Measure | Sample | Mapping methods | Average application quantity of model | Average application quantity of covariate | Validation methods | Average application quantity of performance evaluation indicators | Average application quantity of prediction ability charts | Subgroup analysis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Mean | Max | Direct | Response | Both | Direct | Response | Internal | External | Both | Yes | No | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L (53,46.90%) | 71 | 741.20 | 5708 | 32 (60.38%) | 0 (0%) | 21 (39.62%) | 3.47 | 1.36 | 2.08 | 47 (88.68%) | 1 (1.89%) | 5 (9.43%) | 3.58 | 0.94 | 25 (47.17%) | 28 (52.83%) |

| EQ-5D-3L (26,23.01%) | 172 | 7917.94 | 49,999 | 11 (42.31%) | 3 (11.54%) | 12 (46.15%) | 3.30 | 1.53 | 1.46 | 24 (92.31%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7.69%) | 3.35 | 0.92 | 14 (53.85%) | 12 (46.15%) |

| SF-6D (11,9.73%) | 239 | 3968.45 | 36,706 | 6 (54.55%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (45.45%) | 2.82 | 1.00 | 2.81 | 10 (90.91%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.09%) | 4.36 | 0.55 | 5 (45.45%) | 6 (54.55%) |

| HUI-3 (6,5.31%) | 209 | 1346.83 | 6348 | 5 (83.33%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (16.67%) | 2.33 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 6 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4.00 | 0.83 | 2 (33.33%) | 4 (66.67%) |

| SF-6Dv2 (6,5.31%) | 389 | 1173.50 | 3320 | 6 (10.00%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4.00 | NA | 2.17 | 5 (83.33%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (16.67%) | 4.33 | 1.00 | 3 (50.00%) | 3 (50.00%) |

| CHU9D (3,2.65%) | 108 | 2913.67 | 6898 | 2 (66.67%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.33%) | 4.67 | 1.00 | 2.33 | 2 (66.67%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33.33%) | 2.67 | 0.33 | 2 (66.67%) | 1 (33.33%) |

| ReQoL-UI (2,1.77%) | 1340 | 1956.50 | 2573 | 1 (50.00%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5) | 2.50 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5.00 | 1.50 | 0 (0%) | 2 (100%) |

| 15D (1,0.88%) | 228 | 228.00 | 228 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 3.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3.00 | 0.00 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| AQoL-8D (1,0.88%) | 61 | 61.00 | 61 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3.00 | NA | 2.00 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2.00 | 1.00 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| AQoL-4D (1,0.88%) | 3376 | 3376.00 | 3376 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 7.00 | NA | 2.00 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3.00 | 1.00 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| MSIS-8D (1,0.88%) | 1056 | 1056.00 | 1056 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2.00 | NA | 2.00 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| CHU-9D (1,0.88%) | 2152 | 2152.00 | 2152 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 5.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4.00 | 1.00 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| VFQ-UI (1,0.88%) | 2778 | 2778.00 | 2778 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.00 | NA | 2.00 | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5.00 | 2.00 | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) |

| Total (113) | 61 | 2282.24 | 49,999 | 67 (59.29%) | 3 (2.65%) | 43 (38.05%) | 3.39 | 1.11 | 1.96 | 102 (90.27%) | 1 (0.88%) | 10 (8.85%) | 3.56 | 0.93 | 53 (46.9%) | 60 (53.1%) |

In the parentheses following each target measure, the number and percentage represent the count of studies utilizing that specific target measure and its proportion relative to the total number of target measures. Abbreviation definitions are provided in the List of Abbreviations

The frequency of source measure utilization is presented in Table 1. The most prevalent instruments observed were the EORTC-QLQ series, including EORTC QLQ-C30 (n = 13), EORTC QLQ-H&N35 (n = 3), EORTC QLQ-CR29 (n = 1), and EORTC QLQ-BR53 (n = 1). This was followed by the FACT series, comprising FACT-B (n = 3), FACT-G (n = 3), and FACT-L (n = 1). Notably, most source measures (n = 104) were identified as non-preference-based instruments. However, two studies applied the PBM, specifically the EQ-5D-5L (n = 2) mapped to SF-6Dv2 and EQ-5D-3L. As illustrated in Table 2, the most frequently applied target measure was EQ-5D-5L (n = 53, 46.90%), followed by EQ-5D-3L (n = 26, 23.01%) and SF-6D (n = 11,9.73%).

Table 1.

Frequency of source measure application

| n > 3 | 3 ≥ n > 1 | n = 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EORTC QLQ-C30 (13) | EORTC QLQ-H&N35 (3) | 5-D itch scale (1) | EPIC (1) | IWQOL-Lite (1) | OP (1) | QOLIE-31-P2 (1) | WHODAS 2.0–12 (1) |

| FACT-B (3) | AcroQoL (1) | ESAS-r: Renal (1) | KOOS (1) | OSS (1) | RAND-12 (1) | WHOQOL-BREF (1) | |

| FACT-G (3) | ADCS-ADL (1) | FAACT (1) | Lequesne Functional Index (1) | PANSS (1) | SAQ (1) | WHOQOL-HIV Bref (1) | |

| MLHFQ (3) | ALSFRS-R (1) | FACIT-F (1) | LTCQ-8 (1) | PCI (1) | SBI (1) | WI-NRS (1) | |

| BASDAI (2) | BCVA (1) | FACT-L (1) | MacNew (1) | PDI (1) | SDQ (1) | WOMAC (1) | |

| BASFI (2) | CH-QLQ2 (1) | FAQLQ-PF (1) | MAX-PC (1) | PDQ-8 (1) | SF-36 (1) | ||

| CAT (2) | CLDQ-NASH (1) | FSS (1) | MENQOL (1) | PedsQL 4.0 (1) | Spanish National Health Survey functional disability scale (1) | ||

| EQ-5D-5L (2) | CPCHILD (1) | GAD-7 (1) | MOS-HIV (1) | PedsQL GCS (1) | SQLS (1) | ||

| FACT-H&N (2) | DLQI (1) | GHQ-12 (1) | MSQ (1) | PedsQL (1) | SWEMWBS (1) | ||

| HAQ-DI (2) | EORTC QLQ-BR53 (1) | Haem-A-QoL (1) | ODI (1) | PHQ-9 (1) | TCM-HSS (1) | ||

| HIT-6 (2) | EORTC QLQ-CR29 (1) | HeartQoL (1) | OHS (1) | PROMIS-GH10 (1) | UWQoL (1) | ||

| PROMIS-29 (2) | EPDS (1) | IBS-QoL (1) | OKS (1) | QoL-AD (1) | WHODAS 2.0 (1) | ||

The values in parentheses following each source measure indicate the number of studies that applied that source measure. Abbreviation definitions are provided in the List of Abbreviations

Sample and estimation methods

The reported sample sizes varied significantly, with the smallest being 61 [108] and the largest being 49999 [12] (Table 2). Only three studies (3.26%) had a sample size below 100. Among target measures with multiple Mapping functions, 38.05% of the mapping functions considered both direct and response mapping. For less frequently applied target measures, such as HUI-3 and CHU9D, a higher proportion of mapping functions only employed direct mapping (83.33% and 66.67%). In contrast, among the more commonly used target measures, studies using EQ-5D-3L and SF-6D showed the highest proportions of adopting both mapping methods (39.62% and 45.45%). However, the proportion for EQ-5D-5L was comparatively lower (39.62%), and all studies employing SF-6Dv2 adopted only direct mapping.

Most mapping functions used more than one regression method (n =94, 83.19%), among studies employing direct Mapping, the average number of models used exceeded 3 (Table 2), although 17 studies employed only one model. 36 distinct Mapping model types were employed in total Mapping functions, comprising 369 models (Table 3). The most frequently applied model for direct mapping was OLS (n = 93, 25.20%), followed by Tobit regression (n = 56, 15.18%), GLM (n = 40, 10.84%), and CLAD (n = 37, 10.03%). Additionally, ALDVMM (n = 27, 7.32%), BETAMIX (n = 25, 6.78%), and TPM (n = 21, 5.69%) were also used to some extent (Table 3). In contrast, response Mapping utilized 17 distinct model types, comprising 61 models (Table 3). Mapping functions employing response mapping used an average of only one model, predominantly OLM (n = 19, 31.15%) and ML (n = 12, 19.67%).

Table 3.

Mapping functions information extraction

| Target measure | Models | Covariate | Internal validation methods | Predictive performance metrics | Predictive assessment plots | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Response | |||||

| EQ-5D-5L (53,46.90%) | OLS (45,84.91%) | OLM (10,18.87%) | Age (39,73.58%) | Sample splitting (15,28.3%) | MAE (45,84.91%) | Scatter Plot Comparing Observed and Predicted Values (25,47.17%) |

| Tobit regression (28,52.83%) | ML (5,9.43%) | Gender (33,62.26%) | tenfold cross-validation (14,26.42%) | RMSE (38,71.7%) | Bland–Altman Plot (13,24.53%) | |

| GLM (19,35.85%) | GLOGIT (2,3.77%) | BMI (4,7.55%) | Full-sample resubstitution validation (11,20.75%) | AIC (17,32.08%) | Error Histogram (7,13.21%) | |

| CLAD (17,32.08%) | OPM (2,3.77%) | Treatment and clinical management factors (15,28.3%) | fivefold cross-validation (7,13.21%) | MSE (14,26.42%) | CDF Plot (4,7.55%) | |

| ALDVMM (16,30.19%) | MVP (1,1.89%) | Other disease characteristics/health status factors (11,20.75%) | Validation in temporally distinct datasets (2,3.77%) | BIC (13,24.53%) | Histogram Comparing Observed and Predicted Values (1,1.89%) | |

| BETAMIX (15,28.3%) | SUR-OPM (1,1.89%) | Other demographic/socioeconomic factors (6,11.32%) | Bootstrap validation (2,3.77%) | Adj R2 (12,22.64%) | Failure to account for predictive assessment plots (12,22.64%) | |

| TPM (13,24.53%) | GEE (1,1.89%) | Failure to account for covariate (10,18.87%) | ninefold cross-validation (2,3.77%) | ICC (11,20.75%) | ||

| MM (7,13.21%) | OLR (1,1.89%) | Leave-one-out cross-validation (1,1.89%) | R2 (10,18.87%) | |||

| Beta regression (6,11.32%) | GOPM (1,1.89%) | threefold cross-validation (1,1.89%) | CCC (6,11.32%) | |||

| FLOGIT (3,5.66%) | GBT (1,1.89%) | Spearman's ρ (4,7.55%) | ||||

| GEE (2,3.77%) | MVOPR (1,1.89%) | ME (3,5.66%) | ||||

| Mixed-effects linear regression (2,3.77%) | BN (1,1.89%) | AE (3,5.66%) | ||||

| RMM (1,1.89%) | MLR (1,1.89%) | nRMSE (2,3.77%) | ||||

| MFP (1,1.89%) | Failure to account for response mapping (32,60.38%) | Pred R2 (2,3.77%) | ||||

| FEM (1,1.89%) | nMAE (2,3.77%) | |||||

| FRM (1,1.89%) | Pearson's r (1,1.89%) | |||||

| REM (1,1.89%) | Lin’s CCC (1,1.89%) | |||||

| Mixed-effects Tobit regression (1,1.89%) | MID (1,1.89%) | |||||

| Three part models (1,1.89%) | GMSE (1,1.89%) | |||||

| GBT (1,1.89%) | AICC (1,1.89%) | |||||

| Beta regression-inflated GAMLSS (1,1.89%) | GMAE (1,1.89%) | |||||

| OIB (1,1.89%) | LL (1,1.89%) | |||||

| LASSO (1,1.89%) | MAD (1,1.89%) | |||||

| Median regression (1,1.89%) | ||||||

| EQ-5D-3L (26,23.01%) | OLS (18,69.23%) | OLM (7,26.92%) | Age (18,69.23%) | Sample splitting (11,42.31%) | MAE (24,92.31%) | |

| Tobit regression (12,46.15%) | ML (4,15.38%) | Gender (13,50%) | Full-sample resubstitution validation (9,34.62%) | RMSE (23,88.46%) | ||

| GLM (8,30.77%) | SUR-OPM (3,11.54%) | Zubrod Performance Status (1,3.85%) | fivefold cross-validation (3,11.54%) | BIC (9,34.62%) | ||

| ALDVMM (8,30.77%) | OLR (2,7.69%) | Viral load(log—viral load) (1,3.85%) | Bootstrap validation (2,7.69%) | AIC (7,26.92%) | ||

| TPM (7,26.92%) | NP (2,7.69%) | Race (1,3.85%) | tenfold cross-validation (2,7.69%) | R2 (5,19.23%) | ||

| CLAD (7,26.92%) | MLR (1,3.85%) | BMI (1,3.85%) | Leave-one-out cross-validation (1,3.85%) | MSE (4,15.38%) | ||

| Beta regression (4,15.38%) | NP-LM (1,3.85%) | Diabetes status (1,3.85%) | ICC (4,15.38%) | |||

| BETAMIX (3,11.54%) | GLOGIT (1,3.85%) | Failure to account for covariate (7,26.92%) | ME (4,15.38%) | |||

| ZOIB (1,3.85%) | LASSO (1,3.85%) | Spearman's ρ (3,11.54%) | ||||

| EPM (1,3.85%) | GOPM (1,3.85%) | CCC (1,3.85%) | ||||

| MM (1,3.85%) | Failure to account for response mapping (11,42.31%) | MID (1,3.85%) | ||||

| Mixed-effects linear regression (1,3.85%) | QIC (1,3.85%) | |||||

| MRM (1,3.85%) | Adj R2 (1,3.85%) | |||||

| FLOGIT (1,3.85%) | ||||||

| Cox regression (1,3.85%) | ||||||

| PWL (1,3.85%) | ||||||

| NMIX (1,3.85%) | ||||||

| Failure to account for direct mapping (3,11.54%) | ||||||

| SF-6D (11,9.73%) | OLS (10,90.91%) | OPM (2,18.18%) | Gender (10,90.91%) | Sample splitting (6,54.55%) | MAE (11,100%) | Scatter Plot Comparing Observed and Predicted Values (3,27.27%) |

| Tobit regression (6,54.55%) | OLM (1,9.09%) | Age (8,72.73%) | fivefold cross-validation (4,36.36%) | RMSE (8,72.73%) | Bland–Altman Plot (2,18.18%) | |

| BETAMIX (5,45.45%) | ML (1,9.09%) | Race (1,9.09%) | Full-sample resubstitution validation (2,18.18%) | AIC (7,63.64%) | CDF Plot (1,9.09%) | |

| CLAD (5,45.45%) | MLR (1,9.09%) | Seizure-free status (1,9.09%) | Validation in temporally distinct datasets (1,9.09%) | BIC (6,54.55%) | Failure to account for predictive assessment plots (5,54.55%) | |

| GLM (2,18.18%) | Failure to account for response mapping (5,45.46%) | Health insurance status (1,9.09%) | Leave-one-out cross-validation (1,9.09%) | MSE (3,27.27%) | ||

| MM (1,9.09%) | Marital status (1,9.09%) | tenfold cross-validation (1,9.09%) | Adj R2 (3,27.27%) | |||

| ALDVMM (1,9.09%) | Employment status (1,9.09%) | R2 (2,18.18%) | ||||

| FLOGIT (1,9.09%) | Income level (1,9.09%) | ICC (2,18.18%) | ||||

| NCCN risk category (1,9.09%) | CCC (2,18.18%) | |||||

| Relapse Frequency (1,9.09%) | AE (1,9.09%) | |||||

| Obesity-related comorbidities (1,9.09%) | Spearman's ρ (1,9.09%) | |||||

| Prostate cancer treatment type (1,9.09%) | ME (1,9.09%) | |||||

| Year of prostate cancer diagnosis (1,9.09%) | Pred R2 (1,9.09%) | |||||

| Failure to account for covariate (1,9.09%) | ||||||

| HUI-3 (6,5.31%) | OLS (5,83.33%) | ML (1,16.67%) | Age (1,33.33%) | Full-sample resubstitution validation (2,33.33%) | MAE (5,83.33%) | Error Histogram (2,33.33%) |

| TPM (2,33.33%) | Failure to account for response mapping (5,83.33%) | Gender (1,33.33%) | tenfold cross-validation (3,50.00%) | RMSE (4,66.67%) | Scatter Plot Comparing Observed and Predicted Values (2,33.33%) | |

| Tobit regression (2,33.33%) | Disease severity (1,33.33%) | Sample splitting (1,16.67%) | AIC (3,50%) | Bland–Altman Plot (1,16.67%) | ||

| MRM (1,16.67%) | Mini-mental state examination (1,33.33%) | R2 (3,50%) | Failure to account for predictive assessment plots (3,50.00%) | |||

| CLAD (1,16.67%) | Failure to account for covariate (3,50.00%) | ICC (3,50%) | ||||

| Equipercentile linking (1,16.67%) | Adj R2 (2,33.33%) | |||||

| BETAMIX (1,16.67%) | MSE (1,16.67%) | |||||

| IRT model (1,16.67%) | BIC (1,16.67%) | |||||

| Pearson's r (1,16.67%) | ||||||

| ME (1,16.67%) | ||||||

| SF-6Dv2 (6,5.31%) | OLS (6,100%) | Failure to account for response mapping (6,100%) | Age (6,100%) | tenfold cross-validation (3,50.50%) | RMSE (6,100%) | Bland–Altman Plot (5,83.33%) |

| Tobit regression (5,83.33%) | Gender (3,50%) | Sample splitting (33.33%) | MAE (6,100%) | Scatter Plot Comparing Observed and Predicted Values (1,16.67%) | ||

| CLAD (4,66.67%) | Cancer type (1,16.67%) | Full-sample resubstitution validation (1,16.67%) | AIC (3,50%) | |||

| MM (3,50%) | Negative utility values (1,16.67%) | BIC (3,50%) | ||||

| GLM (3,50%) | BMI (1,16.67%) | CCC (2,33.33%) | ||||

| TPM (1,16.67%) | Worst-dimension attainment (1,16.67%) | Spearman's ρ (2,33.33%) | ||||

| CATREG (1,16.67%) | ICC (2,33.33%) | |||||

| MFP (1,16.67%) | Pred R2 (1,16.67%) | |||||

| Adj R2 (1,16.67%) | ||||||

| CHU9D (3,2.65%) | OLS (3,100%) | MLOGIT (1,33.33%) | Gender (3,100%) | Sample splitting (1,33.33%) | MAE (3,100%) | Scatter Plot Comparing Observed and Predicted Values (1,33.33%) |

| GLM (3,100%) | Failure to account for response mapping (2,66.67%) | Age (2,66.67%) | fivefold cross-validation (1,33.33%) | MSE (2,66.67%) | Failure to account for predictive assessment plots (2,66.67%%) | |

| CLAD (2,66.67%) | Economic status (1,33.33%) | tenfold cross-validation (1,33.33%) | CCC (1,33.33%) | |||

| Tobit regression (1,33.33%) | GMFCS level (1,33.33%) | Bootstrap validation (1,33.33%) | RMSE (1,33.33%) | |||

| EEE (1,33.33%) | R2 (1,33.33%) | |||||

| FMM (1,33.33%) | ||||||

| ZOIB (1,33.33%) | ||||||

| Beta regression (1,33.33%) | ||||||

| MM (1,33.33%) | ||||||

| ReQoL-UI (2,1.77%) | ALDVMM (1,50.00%) | SUR-OPM (1,50.00%) | Gender (2,100%) | Full-sample resubstitution validation (2,100%) | RMSE (2,100%) | CDF Plot (2,100%) |

| BETAMIX (1,50.00%) | Failure to account for response mapping (1,50.00%) | Age (2,100%) | MAE (2,100%) | Bland–Altman Plot (1,50.00%) | ||

| GLM (1,50.00%) | AIC (2,100%) | |||||

| OLS (1,50.00%) | BIC (2,100%) | |||||

| Tobit regression (1,50.00%) | LL (1,50%) | |||||

| AE (1,50%) | ||||||

| 15D (1,0.88%) | OLS (1,100%) | OLM (1,100%) | Gender (1,100%) | Sample splitting (1,100%) | RMSE (1,100%) | Failure to account for predictive assessment plots (1,100%) |

| GLM (1,100%) | Age (1,100%) | MAE (1,100%) | ||||

| MM (1,100%) | ICC (1,100%) | |||||

| AQoL-8D (1,0.88%) | OLS (1,100%) | Failure to account for response mapping (1,100%) | Gender (1,100%) | Sample splitting (1,100%) | RMSE (1,100%) | Scatter Plot Comparing Observed and Predicted Values (1,100%) |

| GLM (1,100%) | Age (1,100%) | MAE (1,100%) | ||||

| MM (1,100%) | ||||||

| AQoL-4D (1,0.88%) | OLS (1,100%) | Failure to account for response mapping (1,100%) | Gender (1,100%) | fivefold cross-validation (1,100%) | RMSE (1,100%) | Error Histogram (1,100%) |

| MM (1,100%) | Age (1,100%) | MAE (1,100%) | ||||

| GLM (1,100%) | ICC (1,100%) | |||||

| BETAMIX (1,100%) | ||||||

| LASSO (1,100%) | ||||||

| GBT (1,100%) | ||||||

| SVR (1,100%) | ||||||

| MSIS-8D (1,0.88%) | OLS (1,100%) | Failure to account for response mapping (1,100%) | Gender (1,100%) | Sample splitting (1,100%) | RMSE (1,100%) | Scatter Plot Comparing Observed and Predicted Values (1,100%) |

| CLAD (1,100%) | Age (1,100%) | MAE (1,100%) | ||||

| CHU-9D (1,0.88%) | OLS (1,100%) | ML (1,100%) | Gender (1,100%) | tenfold cross-validation (1,100%) | RMSE (1,100%) | Scatter Plot Comparing Observed and Predicted Values (1,100%) |

| GLM (1,100%) | Age (1,100%) | MAE (1,100%) | ||||

| MM (1,100%) | CCC (1,100%) | |||||

| Tobit regression (1,100%) | Adj R2 (1,100%) | |||||

| Beta regression (1,100%) | ||||||

| VFQ-UI (1,0.88%) | ALDVMM (1,100%) | Failure to account for response mapping (1,100%) | Gender (1,100%) | Full-sample resubstitution validation (1,100%) | ME (1,100%) | Scatter Plot Comparing Observed and Predicted Values (1,100%) |

| Age (1,100%) | MAE (1,100%) | CDF Plot (2,100%) | ||||

| RMSE (1,100%) | ||||||

| AIC (1,100%) | ||||||

| BIC (1,100%) | ||||||

The values in parentheses represent the frequency with which each category appears in the corresponding target measure. At the same time, the percentages indicate the proportion of these occurrences relative to the total for that target measure. Abbreviation definitions are provided in the List of Abbreviations

Twenty-one mapping functions (18.58%) did not consider any covariates, while the remaining functions employed fewer than two covariates on average (Table 2). The most frequently used covariates were age (n = 82, 72.57%) and gender (n = 71, 62.83%), followed by BMI (n = 6, 5.31%). Additionally, supplementary covariates were included in studies involving different disease domains related to various source measures, such as treatment type for prostate cancer (n = 1) and diabetic status (n = 1).

Validation

All mapping functions were validated for performance (Table 2), typically through internal validation (n = 102, 90.27%). A total of 9 distinct validation methods were employed, amounting to 121 validation procedures (Table 3). The most frequently used method was cross-validation, which included 10-fold (n = 25, 20.66%), 5-fold (n = 16, 13.22%), 9-fold (n = 2, 1.65%), and 3-fold (n = 1, 0.83%), this was followed by sample splitting (n = 38, 31.40%) and full-sample resubstitution validation (n = 28, 23.14%).

Mapping functions employed more than three performance metrics (Table 2), with 22 types used across 274 (Table 3). The most frequently used metrics were MAE (n = 100, 36.50%) and RMSE (n = 89, 32.48%), followed by AIC (n = 42, 15.33%), BIC (n = 35, 12.77%), MSE (n = 26, 9.49%), R2 (n = 21, 7.66%), Adj R2 (n = 20, 7.30%), ICC (n = 19, 6.93%), and CCC (n = 15, 5.47%).

Moreover, 46.90% of the mapping functions conducted subgroup analyses (Table 2). Predictive assessment plots were provided for 90 mapping functions (79.65%), each employing fewer than one plot average. Six types of predictive assessment plots were utilized, amounting to 101 plots overall (Table 3). The most used plots were the Scatter Plot Comparing Observed and Predicted Values (n = 36, 35.64%) and the Bland–Altman Plot (n = 22, 21.78%).

Quality assessment

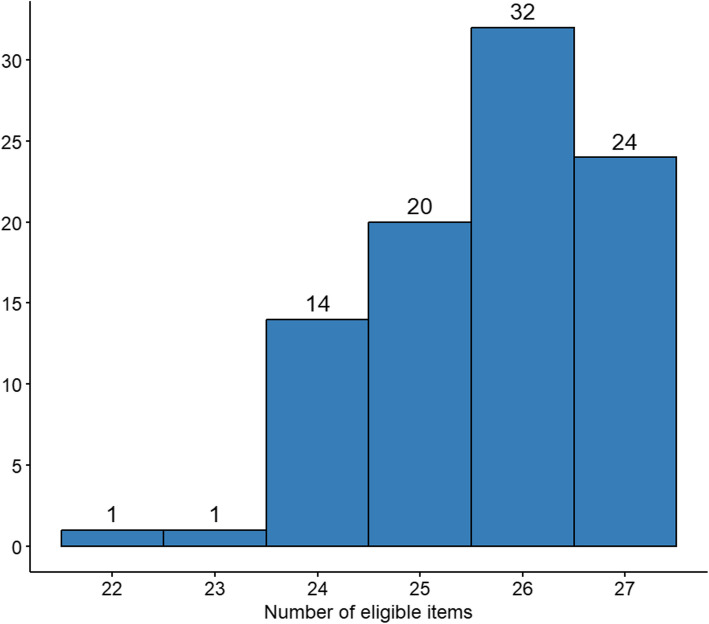

Figure 2 graphically demonstrates the distribution of the studies’ quality. Among the 92 studies focused on Mapping as the primary objective, each met more than 20 of the reporting quality criteria, 24 studies fully satisfied all quality standards, among the 27 quality criteria, deficiencies were observed in 8 items, including sample description (n = 39), conceptual overlap (n = 32), consistency between the sample population and the value set population (n = 29), regression variable description (n = 10), regression design description (n = 6), data integrity and missing data handling (n = 4), description of source and target measures (n = 2), and comparison with previous studies (n = 1).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of eligible items number

Regarding sample description, 37 studies did not report the appropriateness of the sample size, and seven studies failed to indicate whether repeated observations were present. Among the 19 studies that reported the presence of repeated observations, three did not address this issue, while the remaining 16 employed various methods to handle repeated observations. These methods included the use of robust standard errors (n = 3), cluster-robust standard errors (n = 3), random effects/mixed effects models (n = 3), generalized estimating equations (GEE) (n = 3), conducting separate regressions for different time points (n = 2), and averaging the score over two time periods (n = 1).

Thirty-two studies did not assess conceptual overlap before developing the mapping function. While the remaining studies, various methods were employed: Spearman correlation analysis (n = 42), qualitative evaluation of content overlap (n = 12), Pearson correlation analysis (n = 7), exploratory factor analysis (EFA) (n = 5), scatter plot (n =3), Bland–Altman plot (n = 1), intraclass correlation coefficient (n = 1), principal component analysis (PCA) (n = 1), literature review (n = 1), and multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) (n = 1).

Among the 29 studies where the region of the sample population did not match that of the target measure’s value set, two studies could not be compared due to missing region information for the value set. In 3 studies, partial consistency was observed. In 2 of these, the Hong Kong value set was used because mainland China did not have an SF-6D value set at the time, while in 1 study, the UK value set was adopted because the EQ‑5D‑5L and SF‑6D demonstrated good reliability and validity in Singapore. Of the remaining 24 studies, 15 explained that a corresponding value set was unavailable for the sample population at that time. One study (with a Canadian sample) employed the UK value set due to its widespread use. The remaining eight studies did not explain. Furthermore, in three studies, the regions of the sample population and the target measure’s value set were different regions within the same country, ten studies were located on the same continent, and the remaining 16 were from different continents.

In the section on data integrity and missing data handling, three studies did not specify the completeness of the data, and one study did not detail the method used to handle missing values. 56 studies removed missing values, one employed chained regression multiple imputation, and one used median imputation. Additionally, one study excluded questionnaires with more than 20% missing data, while in the SF-6Dv2, items that were missing or marked as “not applicable” were assigned a value of 1, and in the FAQLQ-PF, missing values were imputed using the median. Regarding regression variable descriptions, ten studies did not clarify whether covariates were used, and in the regression design descriptions, six studies did not outline the strategy for selecting model variables. Finally, concerning comparisons with previous studies, only one study did not consider comparing its results with those of previously published mapping algorithms that utilized the same source and target measures.

Discussion

This systematic review comprises 131 studies covering various aspects of Mapping research: 92 focused on Mapping as the primary objective, 21 on economic evaluation, 13 on methodology, and five reviews. Among the 113 mapping functions, the source measures are mostly non-preference-based, with the EORTC-QLQ-C30 being the most frequently used and the EQ-5D-5L being the primary target measure. Sample sizes varied considerably across studies, with only three studies having fewer than 100 participants. Of the Mapping functions, 59.29% employed only direct Mapping, while 38.05% considered both direct and response Mapping. Direct Mapping functions used an average of more than three models, most commonly OLS and Tobit regression. Whereas response mapping studies typically used about one model, predominantly OLM and ML. On average, each model incorporated fewer than two covariates, most frequently age and gender. All mapping functions assessed performance, with 90.27% using internal validation methods, most commonly cross-validation, and sample splitting. More than three performance metrics were reported per mapping function, with MAE and RMSE being the most common, and approximately one predictive performance plot was used on average, most frequently Scatter Plots Comparing Observed and Predicted Values and Bland–Altman Plots. Additionally, 46.9% of the mapping functions conducted subgroup analyses.

Compared to previous review findings [1], studies focused on mapping as the primary objective over the past seven years indicate that the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EQ-5D continue to be the most widely used source and target measures, respectively. Notably, within EQ-5D applications, the use of the EQ-5D-5L has increased from 14.97% to 67.09%, now surpassing the EQ-5D-3L. The incidence of studies with small sample sizes has decreased, with those having fewer than 100 participants dropping from 10 (4%) to 3 (3.26%). Additionally, the proportion of Mapping functions employing both direct and response Mapping increased by 22.05%, and the use of multiple models in Mapping rose by 22.19%. The inclusion of age and gender as covariates increased by 21.57% and 7.83%, respectively, and all recent studies now report model parameters. In predictive performance evaluation, MAE and RMSE remain the most frequently used metrics, while the proportion of Mapping functions reporting predictive performance plots has increased by 27.65%. These trends suggest that recent mapping research has adopted more rigorous sample size requirements, expanded model applications, and enhanced parameter reporting and predictive performance plotting standardization and comprehensiveness.

However, 32 (34.78%) of the studies did not conduct a conceptual overlap analysis. In many cases, the correlation between the dimensions of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and those of the EQ-5D-5L and EQ-5D-3L was only moderate to strong [36, 85, 133]. Due to cultural differences among populations in various regions, which may lead to different interpretations and perceptions of the scales, the observed correlations are uncertain. Conceptual overlap analysis evaluates whether the source measure is appropriate for mapping to the target measure by examining its content and structure, and it is considered a prerequisite for mapping [18]. Future mapping function development should incorporate this step to ensure mapping validity. Furthermore, Pearson correlation analysis, which tends to underestimate the relationship between ordered categorical data [152], was still used in 7 studies for assessing conceptual overlap.The MAPS statement recommends initially applying Spearman correlation to examine the source and target measures relationship, followed by exploratory or confirmatory principal components analysis (PCA) to further investigate and compare their structures [23]. Although Spearman correlation has been widely employed, only one study has used PCA. Future research should comprehensively and appropriately apply these testing methods.

Differences in cultural background, health perceptions, socioeconomic conditions, and healthcare environments across regions may lead to biases in utility estimation when the geographical origin of the sample population does not match that of the target measure’s value set [153, 154]. In studies exhibiting such geographical discrepancies, some cases involve different countries (n = 10, 34.48%), and in over half of the instances (n = 16, 55.17%), the regions do not belong to the same continent. The EQ-5D-3L user manual recommends using the value set from the nearest region when a region value set is unavailable [155]. However, cases remain where the closest available value set is not used. For example, when the EQ-5D-3L is the target measure, and the sample is from Canada, the nearest available value set is from the United States. Nonetheless, the UK value set is chosen because of its widespread use. Moreover, more than half of these studies did not consider response mapping (n = 17, 58.62%). Consequently, even if a value set from the sample's region is later developed, it cannot be substituted. Future research should carefully consider the selection of value sets and, if the data includes detailed information on the dimensions of the target measure, develop response mapping meanwhile.

Currently, direct Mapping functions employ an average of more than 3 models, whereas response mapping functions employ only one average. Since model predictive performance is affected by the type and distribution of data, it is advisable to use a wide variety of models when possible. Testing different combinations of covariates can help compare predictive performance, allowing the selection of the most effective application model. Most existing direct mapping functions employ linear models, with OLS being the most widely used. However, OLS requires the data to meet specific assumptions. Violations, such as repeated measurements and ceiling effects (most individuals achieved the maximum score), can lead to underestimated standard errors when using linear models directly [2, 5, 20, 26, 68]. Furthermore, seven studies did not indicate whether the data contained repeated observations, and three studies with repeated observations did not address this issue. Future studies should verify the presence of repeated measurements and ceiling effects before initiating mapping predictions and apply appropriate adjustments if necessary. For repeated observations, methods like cluster-robust standard errors can be used. In contrast, TPM, ALDVMM, or alternative methods like random forests, unaffected by repeated measurements and ceiling effects, may address it, ensuring estimation accuracy. Small sample sizes can compromise the stability of regression coefficients and increase prediction errors. Thus, studies should justify sample size selection, particularly for rare diseases where samples are often limited [20].

Nevertheless, it should be noted that this study had several potential limitations. Ideally, comparing the findings of the new review with the original review to identify trends would require that both reviews employ identical search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria. However, with mapping research progressing, this strategy and criteria of the new review would be refined and cannot remain unchanged. Although comparisons under these conditions may not be optimal, they still reveal overarching trends by enhancing comprehensiveness while preserving consistency. Secondly, the considerable heterogeneity in validation methods and performance metrics used across studies developing mapping algorithms significantly limits the feasibility of meaningful statistical comparisons. As a result, neither our study nor existing reviews have been able to conduct such analyses. Future research could categorize mapping algorithms by their source and target measures, then validate and compare them using the same datasets, validation methods, and performance metrics. Additionally, studies developing mapping algorithms could strive to reach consensus on the selection of validation methods and performance metrics.

Conclusion

The systematic review indicates that over the past 7 years, the content and format of mapping studies have become more standardized, with the most used source measure, target measure, and models remaining consistent. Sample sizes have generally increased, the proportion of studies employing response mapping has risen, and the type of models applied has diversified. In addition, our analysis finds aspects that previous reviews overlooked, including a lack of conceptual overlap analysis, inadequate handling of repeated measurements, and regional inconsistencies between the sample populations and the value sets. Mapping guidelines require continuous updates to address these limitations, and researchers should adopt more standardized and comprehensive practices in mapping development studies to advance the quality of mapping research collectively.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Searches conducted of the systematic review. The table summarises the search terms and results for each literature search.

Additional file 2. Quality assessment. One table listing the sub-items used and the results of the full-text assessment.

Additional file 3. Data extraction table. Giving details of the studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- HTA

Health Technology Assessment

- CUA

Cost-Utility Analysis

- QALY

Quality Adjusted Life Years

- HRQoL

Health-Related Quality of Life

- HSUV

Health State Utility Value

- PBM

Preference-Based Measures

- 15D

15-Dimensional Health-Related Quality of Life Instrument

- AQoL-8D

Assessment of Quality of Life – 8 Dimensions

- CHU9D

Child Health Utility 9-Dimension

- EQ-5D-3L

EuroQol 5-Dimension 3-Level Questionnaire

- EQ-5D-5L

EuroQol 5-Dimension 5-Level Questionnaire

- HUI-3

Health Utilities Index Mark 3

- ReQoL-UI

Recovering Quality of Life Utility Index

- SF-6D

Short Form 6-Dimension

- SF-6Dv2

Short Form 6-Dimension Version 2

- PROMs

Patient-reported outcome measures

- AcroQoL

Acromegaly Quality of Life Questionnaire

- ADCS-ADL

Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living

- ALSFRS-R

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Functional Rating Scale–Revised

- BASDAI

Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index

- BASFI

Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index

- BCVA

Best-Corrected Visual Acuity

- CAT

COPD Assessment Test

- CH-QLQ

Chronic Headache Questionnaire

- CLDQ-NASH

Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire for Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis

- CPCHILD

Caregiver Priorities & Child Health Index of Life with Disabilities

- DLQI

Dermatology Life Quality Index

- EORTC QLQ-BR53

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Breast Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (53 items)

- EORTC QLQ-C30

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (30 items)

- EQ-5D-5L

EuroQol 5-Dimension 5-Level Questionnaire

- EPDS

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- EPIC

Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite

- ESAS r: Renal

Edmonton Symptom Assessment System—revised for Renal patients

- FAACT

Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Therapy

- FAQLQ-PF

Food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire–Parent Form

- FACIT F

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue

- FACT B

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Breast

- FACT G

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General

- FACT H&N

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Head and Neck

- FACT L

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Lung

- GHQ 12

General Health Questionnaire 12

- GAD 7

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7

- HAQ DI

Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index

- HIT 6

Headache Impact Test 6

- IBS QoL

Irritable Bowel Syndrome Quality of Life Questionnaire

- IWQOL Lite

Impact of Weight on Quality of Life Lite

- KOOS

Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

- LTCQ 8

Long Term Conditions Questionnaire (8 items)

- MacNew

MacNew Heart Disease Health Related Quality of Life Questionnaire

- MAX PC

Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer

- MENQOL

Menopause Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire

- MLHFQ

Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire

- MOS HIV

Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey

- MSQ

Migraine Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire version 2.1

- ODI

Oswestry Disability Index

- OHS

Oxford Hip Score

- OKS

Oxford Knee Score

- PedsQL 4.0

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0

- PANSS

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

- PCI

Head and Neck Patient Concerns Inventory

- PDQ 8

Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire 8

- PHQ 9

Patient Health Questionnaire 9

- PROMIS 29

Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System 29

- PROMIS GH10

Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Global Health 10

- QLQ H&N35

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Head and Neck 35

- QOLIE 31 P

Quality of Life in Epilepsy Inventory 31 Patient Version

- QoL AD

Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease

- RAND 12

RAND 12 Item Health Survey

- SAQ

Seattle Angina Questionnaire

- SBI

Shah modified Barthel Index

- SDQ

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

- SWEMWBS

Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale

- TCM HSS

Traditional Chinese Medicine Health Status Scale

- UWQoL

University of Washington Quality of Life Questionnaire

- WHODAS 2.0

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0

- WHODAS 2.0–12

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 12 item version

- WHOQOL BREF

World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Version

- WHOQOL HIV Bref

World Health Organization Quality of Life HIV Brief

- WINRS

Worst Itching Intensity Numerical Rating Scale

- WOMAC

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

- ALDVMM

Adjusted Limited Dependent Variable Mixture Model

- BETAMIX

Beta mixture model

- CLAD

Censored Least Absolute Deviation

- EEE

Extended Estimating Equations

- EPM

Extended Probit Model

- FEM

Fixed Effects Model

- FLOGIT

Fractional Logit

- FRM

Fractional Regression Model

- GAMLSS

Generalized Additive Models for Location Scale and Shape

- GBT

Gradient Boosted Tree

- GEE

Generalized Estimating Equations

- GLM

Generalized Linear Model

- IRT

Item Response Theory

- MM

Robust MM-estimator

- MRM

Multivariate Regression Model

- NMIX

Normal Mixture Model

- OIB

One-Inflated Beta regression

- OLS

Ordinary Least Squares

- PWL

Piecewise Linear

- REM

Random Effects Model

- Tobit

Tobit regression

- TPM

Two-Part Model

- ZOIB

Zero-One-Inflated Beta regression

- BN

Bayesian Network

- GEE

Generalized Estimating Equations

- GBT

Gradient Boosted Trees

- GLOGIT

Generalized Logit Model

- GOPM

Generalized Ordered Probit Model

- LASSO

Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator

- ML

Multinomial Logistic Model

- MVP

Multivariate Probit Model

- MVOPR

Multivariate Ordered Probit Regression

- NP

Non–Parametric approach

- NP-LM

Non-Parametric approach excluding Logical Inconsistencies

- OLM

Ordered Logit Model

- OPM

Ordered Probit Model

- SUR–OPM

Seemingly Unrelated Regression Ordered Probit Models.

- AIC

Akaike Information Criterion

- Adj R2

Adjusted Coefficient of Determination

- BIC

Bayesian Information Criterion

- CCC

Concordance Correlation Coefficient

- CDF

Cumulative Distribution Function

- DIC

Deviance Information Criterion

- GMSE

Gradient Mean Squared Error

- GMAE

Gradient Mean Absolute Error

- ICC

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient

- LL

Log-likelihood

- MAE

Mean Absolute Error

- ME

Mean Error

- MSE

Mean Squared Error

- MID

Minimum Important Difference

- nMAE

Normalized Mean Absolute Error

- nRMSE

Normalized Root Mean Square Error

- Pearson’s r

Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient

- Pred R2

Predicted Coefficient of Determination

- R2

Coefficient of Determination

- RMSE

Root Mean Square Error

- Spearman’s ρ

Spearman’s rank-correlation coefficient

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Q.S., L.S.; Methodology: Q.S.; Data curation: Q.S., Y.Z.; Formal analysis and investigation: Q.S., Y.Z.; Writing—original draft preparation: Q.S., X.P.; Writing—review and editing: Q.S., X.P., L.S.; Supervision: L.S., X.P.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mukuria C, Rowen D, Harnan S, Rawdin A, Wong R, Ara R, et al. An updated systematic review of studies mapping (or cross-walking) measures of health-related quality of life to generic preference-based measures to generate utility values. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2019;17:295–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan T, Mulhern B, Viney R, Norman R, Tran-Duy A, Hanmer J, et al. Evidence on the relationship between PROMIS-29 and EQ-5D: a literature review. Qual Life Res. 2022;31:79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Williams GR, Hartley GG, Nicol S. The relationship between health-related quality of life and weight loss. Obes Res. 2001;9:564–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wailoo AJ, Hernandez-Alava M, Manca A, Mejia A, Ray J, Crawford B, et al. Mapping to estimate health-state utility from non–preference-based outcome measures: an ISPOR good practices for outcomes research task force report. Value Health. 2017;20:18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernández Alava M, Wailoo A, Pudney S, Gray L, Manca A. Mapping clinical outcomes to generic preference-based outcome measures: development and comparison of methods. Health Technol Assess. 2020;24:1–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Z, Dou L, Li S. Patient-reported Outcome: Recent Advances in Applications and Research at Home and Abroa. Chinese General Practice. 2023;26:401–8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Q, Huang D, Jiang L, Tang Y, Zeng D. Obtaining SF-6D utilities from FACT-H&N in thyroid carcinoma patients: development and results from a mapping study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1160882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan K, Mistry H, Matharu M, Norman C, Petrou S, Stewart K, et al. Mapping between headache specific and generic preference-based health-related quality of life measures. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022;22:277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu G, Hu S, Wu J, Dong Z, Li H. China Guidelines for Pharmacoeconomic Evaluations (2020). China: Market Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pennington B, Hernandez-Alava M, Pudney S, Wailoo A. The impact of moving from EQ-5D-3L to -5L in NICE technology appraisals. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37:75–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alava MH, Wailoo A, Grimm S, Pudney S, Gomes M, Sadique Z, et al. EQ-5D-5L versus EQ-5D-3L: the impact on cost effectiveness in the United Kingdom. Value Health. 2018;21:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez Alava M, Pudney S, Wailoo A. Estimating the relationship between EQ-5D-5L and EQ-5D-3L: results from a UK population study. Pharmacoeconomics. 2023;41:199–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorgelly PK, Doble B, Rowen D, Brazier J, Thomas DM, Fox SB, et al. Condition-specific or generic preference-based measures in oncology? A comparison of the EORTC-8D and the EQ-5D-3L. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:1163–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie S, Wu J, Chen G. Comparative performance and mapping algorithms between EQ-5D-5L and SF-6Dv2 among the Chinese general population. Eur J Health Econ. 2023;25:7–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brazier J, Roberts J, Tsuchiya A, Busschbach J. A comparison of the EQ-5D and SF-6D across seven patient groups. Health Econ. 2004;13:873–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J, Xie S, He X, Chen G, Brazier JE. The simplified Chinese version of SF-6Dv2: translation, cross-cultural adaptation and preliminary psychometric testing. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:1385–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo N, Liu G, Li M, Guan H, Jin X, Rand-Hendriksen K. Estimating an EQ-5D-5L value set for China. Value Health. 2017;20:662–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernández Alava M, Wailoo A, Wolfe F, Michaud K. A comparison of direct and indirect methods for the estimation of health utilities from clinical outcomes. Med Decis Making. 2014;34:919–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben AJ, van Dongen JM, Finch AP, Alili ME, Bosmans JE. To what extent does the use of crosswalks instead of EQ-5D value sets impact reimbursement decisions?: a simulation study. Eur J Health Econ. 2022;24:1253–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meregaglia M, Whittal A, Nicod E, Drummond M. “Mapping” health state utility values from non-preference-based measures: a systematic literature review in rare diseases. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38:557–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osipenko L, Ul-Hasan SA, Winberg D, Prudyus K, Kousta M, Rizoglou A, et al. Assessment of quality of data submitted for NICE technology appraisals over two decades. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e074341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longworth L, Rowen D. NICE dsu technical support document 10: the use of mapping methods to estimate health state utility values. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425834/. Cited 2024 Oct 8. [PubMed]

- 23.Petrou S, Rivero-Arias O, Dakin H, Longworth L, Oppe M, Froud R, et al. The MAPS reporting statement for studies mapping onto generic preference-based outcome measures: explanation and elaboration. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:993–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ara R, Rowen D, Mukuria C. The use of mapping to estimate health state utility values. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35:S57-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dakin H, Abel L, Burns R, Yang Y. Review and critical appraisal of studies mapping from quality of life or clinical measures to EQ-5D: an online database and application of the MAPS statement. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliveira Gonçalves AS, Werdin S, Kurth T, Panteli D. Mapping studies to estimate health-state utilities from nonpreference-based outcome measures: a systematic review on how repeated measurements are taken into account. Value Health. 2023;26:589–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devlin NJ, Drummond MF, Mullins CD. Quality-adjusted life years, quality-adjusted life-year-like measures, or neither? The debate continues. Value Health. 2024;27:689–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Willke RJ, Pizzi LT, Rand LZ, Neumann P. The value of the quality-adjusted life years. Value Health. 2024;27:702–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basu A. Logical inconsistencies with expected utility theory may align better with patient preferences—a response to Paulden et al. Value Health. 2024;27:815–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dakin H, Abel L, Burns R, Koleva-Kolarova R, Yang Y. HERC database of mapping studies, Version 9.0. 2023. Available from: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:919a8d77-7a2b-422e-9437-c545d5c7a04a. Cited 2024 Jul 19.

- 31.Wailoo A, Alava MH, Pudney S. ‘ Mapping to estimate health state utilities. 2023. Available from: http://www.nicedsu.org.uk

- 32.Kral P, Allen FL, Larsen S, Holst-Hansen T, Olivieri A-V, Manton A. Treatment effect of semaglutide 2.4 mg on health-related quality of life from STEP 1 SF-6D derived from SF-36 with Australian weights. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26:1171–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kangwanrattanakul K. Mapping of the World Health Organization quality of life brief (WHOQOL-BREF) to the EQ-5D-5L in the general Thai population. Pharmacoecon Open. 2023;7:139–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo W, Xie S, Wang D, Wu J. Mapping IWQOL-lite onto EQ-5D-5L and SF-6dv2 among overweight and obese population in China. Qual Life Res. 2024;33:817–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fishman J, Higgins V, Piercy J, Pike J. Cross-walk of the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire for Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis (CLDQ-NASH) and the EuroQol EQ-5D-5L in patients with NASH. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2023;21:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crott R. Direct mapping of the QLQ-C30 to EQ-5D preferences: a comparison of regression methods. Pharmacoecon Open. 2018;2:165–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheung YB, Tan HX, Luo N, Wee HL, Koh GCH. Mapping the Shah-modified Barthel index to the Health Utility Index Mark III by the mean rank method. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:3177–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bilbao A, Martín-Fernández J, García-Pérez L, Arenaza JC, Ariza-Cardiel G, Ramallo-Fariña Y, et al. Mapping WOMAC onto the EQ-5D-5L utility index in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Value Health. 2020;23:379–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pennington BM, Hernandez-Alava M, Hykin P, Sivaprasad S, Flight L, Alshreef A, et al. Mapping from visual acuity to EQ-5D, EQ-5D with vision bolt-on, and VFQ-UI in patients with macular edema in the LEAVO trial. Value Health. 2020;23:928–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patton T, Hu H, Luan L, Yang K, Li S-C. Mapping between HAQ-DI and EQ-5D-5L in a Chinese patient population. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:2815–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hernandez-Alava M, Pudney S. Mapping between EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L: a survey experiment on the validity of multi-instrument data. Health Econ. 2022;31:923–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bourbeau J, Granados D, Roze S, Durand-Zaleski I, Casan P, Koehler D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the COPD Patient Management European Trial home-based disease management program. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:645–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou K, Renouf M, Perrocheau G, Magné N, Latorzeff I, Pommier P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of hypofractionated versus conventional radiotherapy in patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer: an ancillary study of the PROstate fractionated irradiation trial - PROFIT. Radiother Oncol. 2022;173:306–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang D, Peng J, Chen N, Yang Q, Jiang L. Mapping study of papillary thyroid carcinoma in China: Predicting EQ-5D-5L utility values from FACT-H&N. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1076879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su J, Liu T, Li S, Zhao Y, Kuang Y. A mapping study in mainland China: predicting EQ-5D-5L utility scores from the psoriasis disability index. J Med Econ. 2020;23:737–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang K, Guo X, Yu S, Gao L, Wang Z, Zhu H, et al. Mapping of the acromegaly quality of life questionnaire to ED-5D-5L index score among patients with acromegaly. Eur J Health Econ. 2021;22:1381–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharma R, Gu Y, Sinha K, Aghdaee M, Parkinson B. Mapping the strengths and difficulties questionnaire onto the child health utility 9d in a large study of children. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:2429–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Franklin M, Hernandez Alava M. Enabling QALY estimation in mental health trials and care settings: mapping from the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 to the ReQoL-UI or EQ-5D-5L using mixture models. Qual Life Res. 2023;32:2763–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gray LA, Wailoo AJ, Alava MH. Mapping the FACT-B instrument to EQ-5D-3L in patients with breast cancer using adjusted limited dependent variable mixture models versus response mapping. Value Health. 2018;21:1399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sun S, Jonsson H, Salen K-G, Anden M, Beckman L, Fransson P. Is ultra-hypo-fractionated radiotherapy more cost-effective relative to conventional fractionation in treatment of prostate cancer? A cost-utility analysis alongside a randomized HYPO-RT-PC trial. Eur J Health Econ. 2022;24:237–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hagiwara Y. Using a sample size calculation framework for clinical prediction models when developing and selecting mapping algorithms based on linear regression. Med Decis Making. 2023;43:992–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhattarai N, Price CI, McMeekin P, Javanbakht M, Vale L, Ford GA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of an enhanced paramedic acute stroke treatment assessment (PASTA) during emergency stroke care: economic results from a pragmatic cluster randomized trial. Int J Stroke. 2022;17:282–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lim J, Choi S-E, Bae E, Kang D, Lim E-A, Shin G-S. Mapping analysis to estimate EQ-5D utility values using the COPD assessment test in Korea. Health Quality Life Outcomes. 2019;17:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Sadique Z, Zapata SM, Grieve R, Richards-Belle A, Lawson I, Darnell R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of high flow nasal cannula therapy versus continuous positive airway pressure for non-invasive respiratory support in paediatric critical care. Critical Care. 2024;28:386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Marrie RA, Dufault B, Tyry T, Cutter GR, Fox RJ, Salter A. Developing a crosswalk between the RAND-12 and the health utilities index for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2020;26:1102–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thokala P, Hnynn Si PE, Alava MH, Sasso A, Schaufler T, Soro M, et al. Cost effectiveness of difelikefalin compared to standard care for treating chronic kidney disease associated pruritus (CKD-aP) in people with kidney failure receiving haemodialysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2023;41:457–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Callander EJ, Slavin V, Gamble J, Creedy DK, Brittain H. Cost-effectiveness of public caseload midwifery compared to standard care in an Australian setting: a pragmatic analysis to inform service delivery. Int J Qual Health Care. 2021;33:mzab084. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Powell LC, L’Italien G, Popoff E, Johnston K, O’Sullivan F, Harris L, et al. Health state utility mapping of rimegepant for the preventive treatment of migraine: double-blind treatment phase and open label extension (BHV3000-305). Adv Ther. 2023;40:585–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hagiwara Y, Shiroiwa T, Taira N, Kawahara T, Konomura K, Noto S, et al. Gradient boosted tree approaches for mapping European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire core 30 onto 5-level version of EQ-5D index for patients with cancer. Value Health. 2023;26:269–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Flint I, Medjedovic J, Drogon O’Flaherty E, Alvarez-Baron E, Thangavelu K, Savic N, et al. Mapping analysis to predict SF-6D utilities from health outcomes in people with focal epilepsy. Eur J Health Econ. 2022;24:1061–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang F, Devlin N, Luo N. Impact of mapped EQ-5D utilities on cost-effectiveness analysis: in the case of dialysis treatments. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20:99–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wen J, Jin X, Al Sayah F, Short H, Ohinmaa A, Davison SN, et al. Mapping the Edmonton symptom assessment system-revised: renal to the EQ-5D-5L in patients with chronic kidney disease. Qual Life Res. 2022;31:567–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lamu AN. Does linear equating improve prediction in mapping? Crosswalking MacNew onto EQ-5D-5L value sets. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21:903–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Desai M, Bentley A, Keck WA, Haag T, Taylor RS, Dakin H. Cooled radiofrequency ablation of the genicular nerves for chronic pain due to osteoarthritis of the knee: a cost-effectiveness analysis based on trial data. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Fatemi B, Rezaei S, Taheri S, Peiravian F. Cost-effectiveness analysis of tofacitinib compared with adalimumab and etanercept in the treatment of severe active rheumatoid arthritis; Iranian experience. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2021;21:775–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen D-Y, Hsu P-N, Tang C-H, Claxton L, Valluri S, Gerber RA. Tofacitinib in the treatment of moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis: a cost-effectiveness analysis compared with adalimumab in Taiwan. J Med Econ. 2019;22:777–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sturkenboom R, Keszthelyi D, Brandts L, Weerts ZZRM, Snijkers JTW, Masclee AAM, et al. The estimation of a preference-based single index for the IBS-QoL by mapping to the EQ-5D-5L in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Qual Life Res. 2022;31:1209–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aghdaee M, Parkinson B, Sinha K, Gu Y, Sharma R, Olin E, et al. An examination of machine learning to map non-preference based patient reported outcome measures to health state utility values. Health Econ. 2022;31:1525–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ayala A, Ramallo-Farina Y, Bilbao-Gonzalez A, Forjaz MJ. Mapping the EQ-5D-5L from the Spanish national health survey functional disability scale through Bayesian networks. Qual Life Res. 2023;32:1785–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mitsakakis N, Bremner KE, Tomlinson G, Krahn M. Exploring the benefits of transformations in health utility mapping. Med Decis Making. 2020;40:183–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morup MF, Taieb V, Willems D, Rose M, Lyris N, Lamotte M, et al. The cost-effectiveness of a bimekizumab versus IL-17A inhibitors treatment-pathway in patients with active axial spondyloarthritis in Scotland. J Med Econ. 2024;27:682–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang X, Yamato K, Kojima Y, Paris JJ, Peterse EFP, Simons MJHG, et al. Modeling monthly migraine-day distributions using longitudinal regression models and linking quality of life to inform cost-effectiveness analysis: a case study of fremanezumab in Japanese-Korean migraine patients. Pharmacoeconomics. 2023;41:1263–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goodwin E, Hawton A, Green C. Using the fatigue severity scale to inform healthcare decision-making in multiple sclerosis: mapping to three quality-adjusted life-year measures (EQ-5D-3L, SF-6D, MSIS-8D). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Webb EJD. An item-response mapping from general health questionnaire responses to EQ-5D-3L using a general population sample from England. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2023;21:327–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vilsboll AW, Kragh N, Hahn-Pedersen J, Jensen CE. Mapping dermatology life quality index (DLQI) scores to EQ-5D utility scores using data of patients with atopic dermatitis from the National Health and Wellness Study. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:2529–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shaw JW, Bennett B, Trigg A, DeRosa M, Taylor F, Kiff C, et al. A comparison of generic and condition-specific preference-based measures using data from Nivolumab trials: EQ-5D-3L, mapping to the EQ-5D-5L, and European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Utility Measure-Core 10 Dimensions. Value Health. 2021;24:1651–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khairnar R, DeMora L, Sandler HM, Lee WR, Villalonga-Olives E, Mullins CD, et al. Methodological comparison of mapping the expanded prostate cancer index composite to EuroQoL-5D-3L using cross-sectional and longitudinal data: secondary analysis of NRG/RTOG 0415. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2022;6:e2100188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang Q, Yu XX, Zhang W, Li H. Mapping function from FACT-B to EQ-5D-5 L using multiple modelling approaches: data from breast cancer patients in China. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hernandez Alava M, Sasso A, Hnynn Si PE, Gittus M, Powell R, Dunn L, et al. Relationship between standardized measures of chronic kidney disease-associated pruritus intensity and health-related quality of life measured with the EQ-5D questionnaire: a mapping study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2023;103:adv11604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Coon C, Bushmakin A, Tatlock S, Williamson N, Moffatt M, Arbuckle R, et al. Evaluation of a crosswalk between the european quality of life five dimension five level and the menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire. Climacteric. 2018;21:566–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Franken MD, de Hond A, Degeling K, Punt CJA, Koopman M, Uyl-de Groot CA, et al. Evaluation of the performance of algorithms mapping EORTC QLQ-C30 onto the EQ-5D index in a metastatic colorectal cancer cost-effectiveness model. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ahadi MS, Vahidpour N, Togha M, Daroudi R, Nadjafi-Semnani F, Mohammadshirazi Z, et al. Assessment of utility in migraine: mapping the migraine-specific questionnaire to the EQ-5D-5L. Value Health Reg Issues. 2021;25:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oliveira Goncalves AS, Panteli D, Neeb L, Kurth T, Aigner A. HIT-6 and EQ-5D-5L in patients with migraine: assessment of common latent constructs and development of a mapping algorithm. Eur J Health Econ. 2021;23:47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zahra M, Durand-Zaleski I, Gorecki M, Autiero SW, Barnett G, Schupbach WMM. Parkinson’s disease with early motor complications: predicting EQ-5D-3L utilities from PDQ-39 data in the EARLYSTIM trial. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu RH, Wong ELY, Jin J, Dou Y, Dong D. Mapping of the EORTC QLQ-C30 to EQ-5D-5L index in patients with lymphomas. Eur J Health Econ. 2020;21:1363–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]