Abstract

Introduction

The prevalence of diabetes and its complications is an important global health problem. Diabetic retinopathy (DR), a common and specific microvascular complication of diabetes, has seriously affected socioeconomic factors and individual quality of life. This cross-sectional study utilized data from NHANES 1999–2020 to investigate the association between family income to poverty ratio (PIR) and DR prevalence among U.S. adults aged 20 years and above.

Methods

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in 1999–2020, which included 39,210 participants, were utilized for this study. They were divided into two groups according to PIR < 5 or PIR ≥ 5. The baseline characteristics were described to show the distribution of each characteristic. Multiple linear regression and curve fitting were used to study the linear and nonlinear correlations between PIR and DR prevalence. Subgroup analysis and interaction tests were performed to test the stability of the relationship between PIR and DR prevalence. ROC analysis was performed to evaluate predictive performance.

Results

Among 39,210 adults aged 20 years and above, 31,907 (81.37%) were in Group 1 (PIR < 5), and 7,303 (18.63%) were in Group 2 (PIR ≥ 5). Compared with the prevalence of DR in Group 1 (2.7%), the prevalence of DR in Group 2 (1.5%) was lower. After adjusting for all covariates, a significant negative correlation was found between PIR and the prevalence of DR (OR: 0.91, 95% CI: [0.86 ~ 0.97], p = 0.002). Non-Hispanic Whites showing significant benefit (OR: 0.87, 95% CI: [0.80 ~ 0.96], p = 0.005, P for interaction = 0.017). After adjusting for age, the ROC analysis demonstrated a discriminative ability of the model with AUC of 0.747(95% CI: [0.74 ~ 0.76]).

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that an increase in PIR is correlated with a decrease in the likelihood of DR occurrence, suggesting its potential application value as an indicator for predicting the likelihood of DR occurrence. More screening and attention should be provided to low-income populations to reduce preventable social burdens.

Keywords: Family income to poverty ratio (PIR), Diabetes mellitus, Diabetic retinopathy, Prevalence, NHANES

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) encompasses a range of metabolic conditions marked by persistently elevated blood glucose levels [1]. Diabetic retinopathy (DR), a frequent and diabetes-specific microvascular complication, affects approximately one-third of the 246 million individuals with diabetes [2]. Estimates suggest that in 2020, approximately 103.12 million adults globally had DR, with projections indicating that this number will rise to 160.50 million by 2045 [3, 4]. According to the Global Burden of Disease Study [3]among adults aged 50 years and above, DR ranks as the fifth leading cause of blindness and moderate to severe vision impairment. Notably, the age-standardized global prevalence of blindness due to diabetic eye disease increased from 14.9% in 1990 to 18.5% in 2020 [3–5]. Additionally, epidemiological research revealed that [6] diabetes retinopathy was a risk factor for systemic vascular complications, which could increase the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, kidney disease and other clinical diseases. Given its substantial impact on public health [4]early prevention and screening for DR are crucial for both public health and clinical outcomes.

Research [7–9] has consistently demonstrated the beneficial influence of income on health outcomes, with higher-income individuals generally experiencing lower morbidity and mortality across various health metrics. This relationship is likely attributed to the advantages provided by greater financial resources, including better access to healthcare, the ability to afford rising medication costs, improved housing conditions, and healthier dietary options [7]. In this study, income was measured via family income to poverty ratio (PIR), an index developed by NHANES that adjusts annual household income for household size and the poverty threshold guidelines established by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Based on the local cost of living [7]different rules apply to different places. PIR is calculated by dividing family or individual income by the poverty threshold specific to each survey cycle, serving as an effective indicator of income disparity closely tied to human life and health [9, 10]. Since healthcare expenses are often shouldered by families, PIR may offer a more reliable measure for assessing income in healthcare contexts. Utilizing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999 to 2020, this cross-sectional study thoroughly examined the relationship between PIR and the prevalence of DR.

Materials and methods

Data sources and study population

This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for observational research reporting. Data were obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) managed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The procedures complied with ethical standards established by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board, which granted approval for this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. We downloaded data spanning 1999–2020 from the NHANES website (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes), encompassing 107,622 participants across 10 survey cycles. The dataset includes demographic information, laboratory data, and questionnaire responses.

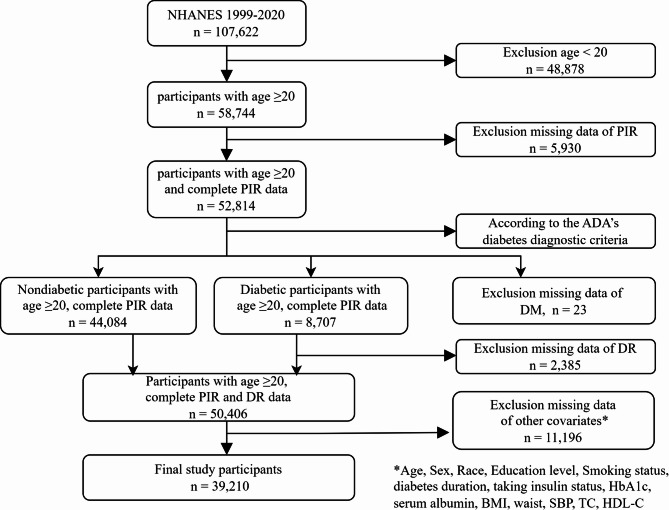

The study participants consisted of individuals aged 20 years and above in the United States, excluding those under the age of 20 (n = 48,878) and those with missing PIR data (n = 5,930). According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA) diagnostic criteria for diabetes [11] diabetes is defined as having any of the following conditions: (a) fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or HbA1c concentration ≥ 6.5% or 2-h PG ≥ 11.1 mmol/L during the OGTT; (b) a response ‘yes’ to the question: ‘Doctor told you have diabetes?’ or ‘Taking insulin now?’. For participants with diabetes, we excluded those who lacked self-reported data on DR (n = 2,385); for nondiabetic participants, missing self-reported data on DR were standardized as not having DR. Missing data of DM and DR were also excluded. Additionally, 11,196 participants had missing data on other covariates. Ultimately, 39,210 cases were included in the final sample (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart illustrating the selection of participants in the NHANES from 1999–2020. DM, diabetes mellitus; DR, diabetic retinopathy; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Assessment of PIR

According to the NHANES official website, PIR variable was calculated by dividing family income (INDFMIN2) by poverty guidelines, which are specific to family size, as well as the appropriate year and state. The values were not computed if the income screener information (INQ 220: < $20,000 or ≥ $20,000) was the only family income information reported. If family income was reported as a range value, the midpoint of the range was used to compute the variable. Values at or above 5.00 were coded as 5.00 or more due to disclosure concerns. The values were not computed if the family income data were missing. In this study, we categorized individuals with PIR < 5 into Group 1 and those with PIR ≥ 5 into Group 2.

Assessment of DR

The occurrence of DR is considered as the outcome factor in this study. DR is defined as a response ‘yes’ to the question “Has any doctor ever told you that diabetes has affected your eyes or that you had retinopathy?” Nondiabetic patients lacking these self-reported data were categorized as ‘No’.

Study variables

The demographic variables included in this analysis were participants’ age (years), sex (male or female), race (Mexican American, other Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, or other race), and education level (below high school, high school, or above high school). In addition, according to clinical practice and covariate screening, we also included body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, smoking status, disease duration, taking insulin status, HbA1c, serum albumin (ALB), systolic blood pressure (SBP), total cholesterol (TC), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) reported by the NHANES. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters and was grouped into underweight (< 18.5), normal (18.5 to < 25), overweight (25 to < 30), and obese (≥ 30). Smoking status was classified as never-smoker (smoking fewer than 100 cigarettes in their entire life), former smoker (smoking more than 100 cigarettes but having quit smoking) or current smoker (smoking at least 100 cigarettes in their entire life). The duration of diabetes was calculated by subtracting the age of diabetes obtained for the first time from the age. For nondiabetic participants, missing self-reported data on taking insulin were standardized as not taking insulin. The waist circumference, HbA1c, serum ALB, SBP, TC and HDL-C data were extracted from the NHANES website.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), whereas categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. The normality of continuous variables was examined via the Shapiro‒Wilk test. Student’s t test was used for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Mann‒Whitney U test was used for nonnormally distributed continuous variables. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. A simple deletion method was used for variables with missing data.

We conducted univariate logistic regression analysis and multivariate logistic regression analysis to control the potential confounders. Two logistic regression models adjusted for different confounders were established in this study. Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, race, and education level. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, race, education level, BMI, waist circumference, smoking status, duration of diabetes, taking insulin status, HbA1c, serum ALB, SBP, TC and HDL-C. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to study the relationship between PIR and the prevalence of DR. To reduce potential bias, we also performed subgroup analysis and interaction analysis on age (20–39, 40–59, > 60), sex, race, education level, BMI, smoking status, and taking insulin status. To explore the association between PIR and prevalence of DR, RCS analyses were performed. In the RCS model, we also adjusted for all confounding factors. The predictive validities were quantified as areas under the ROC curves. All the data were statistically analyzed via R software (version 4.4.2).

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the two groups with PIR < 5 and PIR ≥ 5 in the NHANES from 1999 to 2020. The average age of the study population was 48.4 years, 48.8% were male, most were non-Hispanic white (46.1%), and the prevalence of DR was 2.5%. According to PIR score, 31,907 (81.37%) participants were in Group 1 (PIR < 5), and 7,303 (18.63%) were in Group 2 (PIR ≥ 5). Compared with those in Group 1, more participants in Group 2 were elderly non-Hispanic white men, with higher education levels, lower BMI, fewer smokers, lower HbA1c levels, lower SBP levels and shorter diabetes durations. Compared with the prevalence of DR in Group 1 (2.7%), the prevalence of DR in Group 2 (1.5%) was lower, and the prevalence of DR in Group 1 was higher in each survey cycle (as shown in Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of adult participants in NHANES 1999–2020

| Characteristics | Total | Ratio of family income to poverty | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 5 | ≥ 5 | |||

| Participants, N | 39,210 | 31,907 | 7,303 | |

| Age, years | 48.4 ± 17.8 | 48.0 ± 18.2 | 49.8 ± 15.4 | < 0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 19,119 (48.8) | 15,333 (48.1) | 3,786 (51.8) | < 0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Mexican American | 6,530 (16.7) | 6,013 (18.8) | 517 (7.1) | |

| Other Hispanic | 3,193 (8.1) | 2,862 (9) | 331 (4.5) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 18,068 (46.1) | 13,525 (42.4) | 4,543 (62.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 7,835 (20.0) | 6,836 (21.4) | 999 (13.7) | |

| Other race | 3,584 (9.1) | 2,671 (8.4) | 913 (12.5) | |

| Education level, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Below high school | 9,540 (24.3) | 9,224 (28.9) | 316 (4.3) | |

| High school | 9,030 (23.0) | 8,099 (25.4) | 931 (12.7) | |

| Above high school | 20,640 (52.6) | 14,584 (45.7) | 6,056 (82.9) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Never smoker | 21,327 (54.4) | 16,810 (52.7) | 4,517 (61.9) | |

| Former smoker | 9,617 (24.5) | 7,617 (23.9) | 2,000 (27.4) | |

| Current smoker | 8,266 (21.1) | 7,480 (23.4) | 786 (10.8) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 595 (1.5) | 526 (1.6) | 69 (0.9) | |

| Normal (18.5–25) | 11,171 (28.5) | 8,854 (27.7) | 2,317 (31.7) | |

| Overweight (25–30) | 13,431 (34.3) | 10,728 (33.6) | 2,703 (37.0) | |

| Obese (≥ 30) | 14,013 (35.7) | 11,799 (37.0) | 2,214 (30.3) | |

| Waist, cm | 98.5 ± 15.9 | 98.8 ± 16.1 | 97.2 ± 14.9 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes duration, year | 1.40 (5.46) | 1.51 (5.69) | 0.90 (4.25) | < 0.001 |

| Taking insulin now, n (%) | 1,224 (3.1) | 1,089 (3.4) | 135 (1.8) | < 0.001 |

| HbA1c,% | 5.6 ± 1.0 | 5.7 ± 1.0 | 5.5 ± 0.8 | < 0.001 |

| SBP, mmHg | 124.2 ± 19.3 | 124.6 ± 19.7 | 122.5 ± 17.6 | < 0.001 |

| TC, mg/dL | 195.0 ± 42.3 | 194.3 ± 42.6 | 197.9 ± 40.8 | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C, mmol/l | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| Serum albumin, g/L | 42.3 ± 3.6 | 42.2 ± 3.7 | 42.7 ± 3.5 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 4,656 (11.9) | 4,068 (12.7) | 588 (8.1) | < 0.001 |

| DR, n (%) | 984 (2.5) | 873 (2.7) | 111 (1.5) | < 0.001 |

N reflects the study sample. PIR Poverty income ratio, BMI Body mass index, SBP Systolic blood pressure, TC Total cholesterol, HDL-C High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, DR Diabetic retinopathy

Fig. 2.

Trends in the prevalence of DR among participants 20 years and above stratified by Income Group, 1999–2020

Associations between PIR and the prevalence of DR

Table 2 shows the single-factor logistic regression of PIR and DR prevalence and the multifactor logistic regression analysis of two models after adjusting for relevant variables to evaluate the correlation between PIR and DR prevalence. The unadjusted model revealed that PIR was negatively correlated with DR prevalence (OR: 0.83, 95% CI: [0.79 ~ 0.86], p < 0.001). After adjusting for all confounders, this relationship remained statistically significant (OR: 0.91, 95% CI: [0.86 ~ 0.97], p = 0.002).

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted associations between PIR and the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy according to different models

| Exposure | Unadjusted model | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| PIR classification | 0.83 (0.79–0.86) | p < 0.001 | 0.86 (0.82–0.90) | p < 0.001 | 0.91 (0.86–0.97) | p = 0.002 |

|

Group2 (PIR ≥ 5), n = 7,303 |

Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

|

Group1 (PIR < 5), n = 31,907 |

0.83 (0.78–0.88) | p < 0.001 | 0.84 (0.79–0.90) | p < 0.001 | 0.87 (0.81–0.94) | p < 0.001 |

Unadjusted model: no covariates were adjusted. Model 1: Age, sex, race and education level were adjusted. Model 2: All covariates were adjusted. A P value (P for trend) < 0.05 suggests that the linear trend is statistically significant. PIR, ratio of family income to poverty

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses were performed to examine the robustness of the association between PIR and DR prevalence in different population settings (Fig. 3). The association of PIR on DR prevalence was only modified by race (P for interaction = 0.017), With Non-Hispanic Whites showing significant benefit (OR: 0.87, 95% CI: [0.80 ~ 0.96], p = 0.005) but not on other races. The relationship in other subgroups maintained consistent with the main results (P for interaction > 0.05 for age, sex, education level, BMI, smoking status, taking insulin status).

Fig. 3.

Subgroup analysis of the association between PIR and presence of DR in the age, sex, race, education level, BMI, smoking status, taking insulin status. All covariates were adjusted.OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

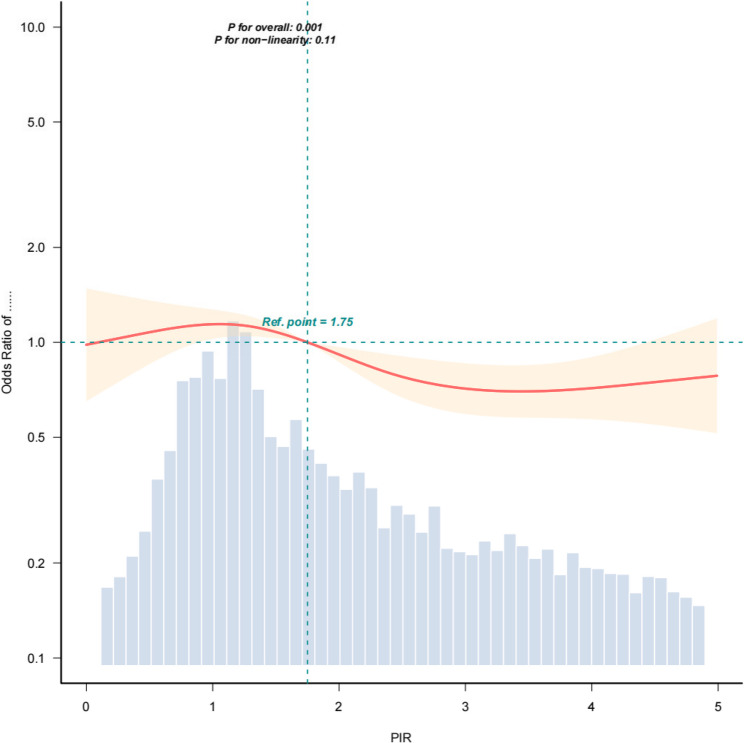

Curve fitting

Since PIR of respondents with PIR > 5 is recorded as 5, we studied curve fitting for the subgroup with PIR < 5 alone. The RCS analysis further confirmed the linear negative correlation between PIR and the presence of DR (p = 0.11 for the nonlinear test), as illustrated in Fig. 4. The multivariate logistic regression of this subgroup was recalculated(OR: 0.87, Cl: [0.81 ~ 0.94], p < 0.001).

Fig. 4.

Restricted cubic splines showing the relationship between PIR and the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy. All covariates were adjusted

ROC curve

As shown in Fig. 5, after adjusting for age, the ROC analysis demonstrated a discriminative ability of the model with an AUC of 0.747 (95% CI: [0.735 ~ 0.759]). At the optimal cutoff threshold of 0.020, the model achieved a sensitivity of 82.0% and a specificity of 59.0%. The data showed that PIR had a moderate predictive value for the prevalence of DR.

Fig. 5.

Receive–operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis for PIR as a predictor of the severity of diabetic retinopathy, after adjusting for age

Discussion

In this large cross-sectional study of American adults aged 20 years and above, we found that PIR was negatively correlated with the prevalence of DR (OR: 0.91, 95% CI: [0.86 ~ 0.97], p = 0.002). The curve fitting results showed that the high-income group had a lower risk of DR than the low-income group. The results of subgroup analysis and interaction analysis showed that the association was robust in all ages and genders, but the association was more significant in non Hispanic white individuals (OR: 0.87, 95% CI: [0.80 ~ 0.96], p = 0.005, P for interaction = 0.017). Racial differences indicated potential social environmental factors. We should also consider the large difference in the number of samples from different ethnic groups, which leads to insufficient statistical power and cannot detect the true association. In the population with BMI < 25 (OR: 1.07, 95% CI: [0.92 ~ 1.24], p = 0.371), the non significant interaction (p = 0.324) means that weight status may not significantly change the exposure outcome relationship. ROC analysis after adjusting for age yielded an AUC of 0.749, indicating the moderate predictive value of PIR for the presence of DR. The high sensitivity (82.6%) and relatively low specificity (58.9%) indicate that PIR has potential value as a screening tool, and clinical practice should be considered in disease prediction as an economic indicator.

Clinically, DR is defined as the presence of typical retinal microvascular signs in individuals with diabetes mellitus [2]. Although diabetes affects the eye in many ways (e.g. increasing the risk of cataracts) [12], DR is the most common and serious ocular complication [2]. Targeted early screening of DR provides a way for the diagnosis and treatment of DR to reduce the burden of preventable blindness [13]. Previous studies on the prevalence of DR focused on hyperglycemia, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes duration and many other risk factors [2], as well as inflammation, vitamins, lactate dehydrogenase and other related indicators [14–18]; however, few studies have explored the prevalence of DR in the field of income, especially large-scale cross-sectional studies. Using data from the NHANES (1999–2020), this cross-sectional study revealed a significant inverse linear relationship between PIR and the prevalence of DR.

Although the exact mechanism by which PIR affects DR prevalence is unclear, we propose a potential explanation on the basis of existing studies. Low-income families are faced with living and eating environments that are not conducive to physical health, relatively poor psychological status, and lacking in adequate medical coverage [10, 19]. This is usually more likely to lead to the occurrence of diabetes and hinders timely screening, diagnosis and treatment of DR, thus promoting the occurrence and progression of DR. In contrast, individuals with higher household income have sufficient financial ability and energy to screen for and intervene in diseases and inhibit disease progression. A survey [20] of vision health in the United States revealed that individuals with lower education and income were less likely to see an ophthalmologist. They are most likely unable to obtain vision screening programs and are less able to afford glasses when needed. Moreover, due to the influence of various social and psychological factors, individuals with higher socioeconomic status have higher medical compliance and often hold a positive attitude toward disease treatment, further delaying the progression of the disease.

On the basis of these findings, we speculate that PIR can be used as a potential indicator to reflect the prevalence of DR, thus providing a valuable reference point for predicting the possibility of DR occurrence. Especially for different race and low-income areas, it has strong sociological significance, therefore policy and public health efforts should be directed to provide assistance to DR high-risk groups and regions. Meanwhile, we should provide more DR screening and attention to low-income people and intervene through health education and treatment in advance to prevent their onset and slow their progress to reduce the preventable social burden. In addition, as a measure of economic status, PIR may be a useful tool for assessing socioeconomic differences.

This study has the following limitations, among which the first is the limitation of the cross-sectional study itself. The study explored the linear relationship between PIR and the prevalence of DR, while the causal relationship between the two still needs to be further explored. Second, the results of our evaluation rely on NHANES self-reported information, which may have potential bias and cannot fully reflect the real situation, in particular, self-reports involving taking insulin status. Third, the sample size is limited. In particular, information about DR after 2021 was not collected from the NHANES database, i.e. we lack relevant data from recent years. If we have access to more sample data, more accurate results will be obtained. Fourth, although many potential confounding factors and exclusion criteria are considered, other confounding factors not considered may affect the experimental results, which may contribute to confounding bias. It is worth noting that for type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes causing DR, due to the limitation of NHANES itself, we fail to make a distinction. Taking these limitations into account, we performed multivariate analysis, subgroup analysis and interaction analysis, while further longitudinal studies are still needed to verify our findings.

Results

We established a correlation between PIR and the prevalence of DR. An increase in PIR was correlated with a decrease in the probability of DR, indicating that it has potential application value as an indicator to predict the probability of DR. Although specific clinical conclusions are provided, the exact underlying mechanism is still unclear. Therefore, further trials are needed to provide more evidence to illustrate the predictive value of PIR for the prevalence of DR.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ALB

Albumin

- BMI

Body mass index

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- DR

Diabetic retinopathy

- e.g.

Exempli gratia (for example)

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- PIR

Income-to-poverty ratio

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- TC

Total cholesterol

Authors’ contributions

Y.S. analyzed and interpreted all data, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. Y.Q. wrote and revised parts of the manuscript. L.G. provided the conceptualization, reviewed and edited part of manuscripts.H.Z. provided the methodology, and carried out supervision and project administration. X.H. oversaw and supported data analysis.L.L.Verified the results. Z.L. provided Software support. R.X. carried out statistical analysis and visualization. X.Z. provided important suggestions on the manuscript. X.W. and D.Z. downloaded and managed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong province (ZR2022MH054, ZR2019MH064), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81703838), the Key Research and Development in Shandong Province (2019GSF108210), the 2022 Traditional Chinese Medicine literature and characteristic technology inheritance project (0686-2211CA080200Z), the Shandong Geriatric Society (LKJGG2021W110) and the Traditional Chinese Medicine science and technology project of Shandong Province (2021Z044).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) repository, [https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes]

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocols involved were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Research Ethics Review Board (ERB).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hongxing Zhang and Xiaochun Han has the equal contribution and share the corresponding authorship.

Yanzheng Song is the first author, Yanzheng Song and Yaohui Qu has the equal contribution.

Contributor Information

Liangqing Guo, Email: glq5028@163.com.

Hongxing Zhang, Email: drzhanghongxing@163.com.

Xiaochun Han, Email: hanxch002@163.com.

References

- 1.Gomułka K, Ruta M. The role of inflammation and therapeutic concepts in diabetic Retinopathy-a short review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(2): 1024. 10.3390/ijms24021024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung N, Mitchell P, Wong TY. Diabetic retinopathy. Lancet (London England). 2010;376(9735):124–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teo ZL, Tham YC, Yu M, et al. Global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through 2045: systematic review and Meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2021;128(11):1580–91. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yau JWY, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(3):556–64. 10.2337/dc11-1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators, Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the right to sight: an analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(2):e144–60. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30489-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung N, Wong TY. Diabetic retinopathy and systemic vascular complications. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2008;27(2):161–76. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdalla SM, Yu S, Galea S. Trends in cardiovascular disease prevalence by income level in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2018150. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yi H, Li M, Dong Y, et al. Nonlinear associations between the ratio of family income to poverty and all-cause mortality among adults in NHANES study. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):12018. 10.1038/s41598-024-63058-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minhas AMK, Jain V, Li M, et al. Family income and cardiovascular disease risk in American adults. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):279. 10.1038/s41598-023-27474-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia Y, Ca J, Yang F, Dong X, Zhou L, Long H. Association between family income to poverty ratio and nocturia in adults aged 20 years and older: a study from NHANES 2005–2010. PLoS One. 2024;19(5):e0303927. 10.1371/journal.pone.0303927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(Suppl 1):S19–40. 10.2337/dc23-S002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeganathan VSE, Wang JJ, Wong TY. Ocular associations of diabetes other than diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(9):1905–12. 10.2337/dc08-0342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nwanyanwu KMJH, Nunez-Smith M, Gardner TW, Desai MM. Awareness of diabetic retinopathy: insight from the National health and nutrition examination survey. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(6):900–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dascalu AM, Georgescu A, Costea AC, et al. Association between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) with diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetic patients. Cureus. 2023. 10.7759/cureus.48581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang P, Xu W, Liu L, Yang G. Association of lactate dehydrogenase and diabetic retinopathy in US adults with diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes. 2024;16(1): e13476. 10.1111/1753-0407.13476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeong H, Maatouk CM, Russell MW, Singh RP. Associations between lipid abnormalities and diabetic retinopathy across a large united States National database. Eye. 2024;38(10):1870–5. 10.1038/s41433-024-03022-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi YJ, Kwon JW, Jee D. The relationship between blood vitamin A levels and diabetic retinopathy: a population-based study. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):491. 10.1038/s41598-023-49937-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Ophthalmology, Sir Run Run Hospital, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 211112, Jiangsu Province, China, Gao Y, Tang Y, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with type 2 diabetes at different stages of diabetic retinopathy. Int J Ophthalmol-Chi. 2024;17(5):877–82. 10.18240/ijo.2024.05.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seabrook JA, Avison WR. Socioeconomic status and cumulative disadvantage processes across the life course: implications for health outcomes. Can Rev Sociol. 2012;49(1):50–68. 10.1111/j.1755-618x.2011.01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Cotch MF, Ryskulova A, et al. Vision health disparities in the united States by race/ethnicity, education, and economic status: findings from two nationally representative surveys. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(6 Suppl):S53–e621. 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) repository, [https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes]