Abstract

Engineering the properties of electromagnetic wavefronts has become essential to imaging, wireless security, sensing, and wireless communication. In particular, wavefronts that exhibit low spatial coherence can enable sensing functionalities with high accuracy and low latency. The typical use of such wavefronts cannot take advantage of these possibilities, as they require the ability to dynamically reconfigure the wavefront in a controllable and repeatable fashion, over a broad spectral bandwidth. Here, we propose a new approach for generating broadband reconfigurable wavefronts which not only exhibit low spatial coherence at a particular frequency, but are also decorrelated with the wavefronts simultaneously generated at other frequencies. We demonstrate that this frequency-domain decorrelation is a key feature that, in combination with dynamic reconfigurability, enables localization measurements with an order-of-magnitude improvement in accuracy compared to the state of the art.

Subject terms: Electrical and electronic engineering, Techniques and instrumentation

Burak Bilgin and colleagues propose an approach for generating broadband reconfigurable wavefronts exhibiting low spatial and spectral coherence. Broadcasting such wavefronts enables rapid localization with an order-of-magnitude improvement in accuracy compared to prior methods.

Introduction

Wavefront engineering has become an integral method in the millimeter-wave and terahertz regimes for imaging, wireless sensing, security, and communications1,2. The ability to tailor and dynamically reconfigure the wavefront of an electromagnetic broadcast has emerged as a key capability for many RF systems. Starting with conventional beamforming using phased arrays, this field has recently grown to encompass more diverse and exotic wavefronts, including those which possess orbital angular momentum3,4 and those which exhibit unique and unusual properties in the near field of the transmitting aperture5,6. Of particular interest here is the class of wavefronts with low spatial coherence, in which the amplitude and/or phase of the wave E(θ, ϕ) vary rapidly with the angular coordinates. Such waves, initially described in the context of statistical optics7, have been recognized as valuable tools in RF systems, enabling advances in wireless security8–11, imaging12–14, and sensing15–19. Despite the growing interest in such wavefronts, there have been few examples exploiting the ability to dynamically reconfigure between different realizations of a low-coherence wavefront. This is particularly the case for broadband signals where diverse incoherent wavefronts are generated simultaneously across a bandwidth, allowing one to exploit not only the low spatial coherence but also the low coherence in the spectral domain.

In this work, we demonstrate that such dynamically reconfigurable low-coherence broadband wavefronts can provide unique new capabilities. We illustrate this point by demonstrating how such fields can be employed for enhanced angular localization, an important capability for many RF systems20–23. A crucial aspect of our approach is that each broadband wavefront is not only spatially incoherent but also spectrally incoherent, such that different frequency components within the bandwidth of the radiated signal exhibit distinct angular amplitude and phase profiles. The aperture that generates these wavefronts is equipped with resonators that have continuously tunable and frequency-diverse amplitude and phase modulation capabilities, enabling sequential re-randomization of the wavefronts at each frequency, thereby unlocking distinct low-coherence wavefront generation across different time instances over wideband. In this work, we exploit this joint spectral and spatial coherence to demonstrate a new framework for angular localization, which offers better than 0.1° angular uncertainty, representing an order-of-magnitude improvement in estimation error with respect to prior methods15,24–26, with the lowest average error reported being 1° in ref. 26.

Results and discussion

Wavefront generation

Our approach for generating programmable low-coherence wavefronts combines a wideband radiation source with a multi-pixel transmissive metasurface, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The metasurface consists of an array of sub-wavelength metallic split-ring resonators (SRRs) on a dielectric substrate. These SRRs are grouped into interconnected subsets to form a number of adjacent column-shaped pixels27. Each electrically-interconnected set of SRRs forms a Schottky contact to the underlying doped semiconductor, such that a reverse bias applied between this contact and an ohmic contact generates a depletion region underneath and adjacent to the metallization. An analog voltage applied to the Schottky contact, therefore, continuously tunes the scattering response of the column of SRRs to an incident THz wave28.

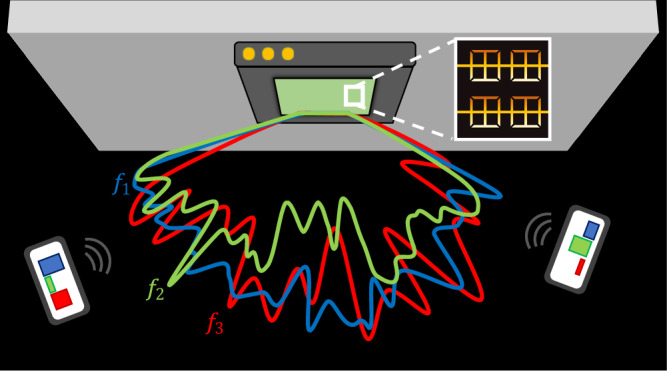

Fig. 1. Low-coherence wavefronts.

Visualization of a broadband source generating low-coherence wavefronts at different frequencies simultaneously by electrically tuning the metasurface attached to its transmitting aperture. Its tunability allows dynamic wavefront generation and deployment of effective communication tools through the same structure, enabling joint communication and sensing.

The geometrical parameters of the SRRs are chosen to produce a resonant response at a frequency of 145 GHz, producing an amplitude modulation over a spectral width of about 25 GHz, and an on-off contrast ratio of about 4.5 dB on resonance. As a result, in the waveguide D band (frequencies between 110 and 170 GHz), both the amplitude and phase of the field scattered by the SRRs change with respect to both frequency and applied bias. The pixels, therefore, collectively form a one-dimensional reconfigurable grating, where the scattering response of each column of the grating can be independently controlled by an external voltage bias27. For any voltage V applied to a given column within the allowable voltage range (between zero volts and −20 V, the maximum reverse bias), the scattered field from that column experiences an amplitude change ΔA and a phase shift Δϕ which both depend on the voltage, and which vary for each frequency within the incident wave’s spectral bandwidth (see Supplementary Note 1 and Fig. S1). By applying a random set of control voltages to the P columns, we can therefore convert an incident spatially coherent beam into an outgoing scattered wave with low spatial coherence in one dimension (i.e., in the plane perpendicular to the columns of the metasurface).

Evidently, the efficacy of this approach to generating low-coherence wavefronts depends on the range of amplitude and phase values at each of the incident frequencies, ΔAmax(f) and Δϕmax(f). One challenge in implementing this strategy for producing low-coherence wavefronts lies in the achievable range of modulation parameters provided by the metasurface. The limited range of phase modulation is a well-known problem in such planar devices29, with no examples in the literature reporting greater than about Δϕmax≈130°30 (although more elaborate designs can achieve greater than 2π range31). For our device, the maximum phase modulation depends on frequency due to the resonant response, but never exceeds about Δϕmax≈50° in the D band spectrum. We therefore must determine the minimum spatial coherence that can be produced by a modulator of the sort described here.

Numerical modeling

As a first step, we explore this question using Monte Carlo simulations. For a given range of amplitude and phase modulation ΔAmax and Δϕmax, and a given number of pixels P, we model each pixel (column) of the device as a scattering site producing a spherical wave with a randomly chosen amplitude and phase within the allowable range. We then compute the superposition of these spherical waves to determine the net electric field as a function of angle, according to:

| 1 |

Here, r = {r1, r2, ⋯ rP} is the vector of distances from the pth column to the user, Aineiωt is the incident wave (a uniform plane wave), and denotes the scattering function of the pth pixel, chosen randomly within the allowed range defined by ΔAmax and Δϕmax. Since the metasurface in our study contains long, narrow column-shaped pixels, we may treat this as effectively a one-dimensional problem, neglecting the azimuthal angle dependence, although of course the results can readily be generalized to two-dimensional metasurface arrays.

For each E(f, θ) determined in this fashion, we can compute the degree of angular correlation of the wavefront. By averaging over many realizations of the randomness, we can extract an ensemble-averaged angular correlation function, defined as:

| 2 |

where the angle brackets indicate averaging over the random ensemble, and where Δθ = θ1 − θ2 (see “Methods” section for details on ensemble averaging).

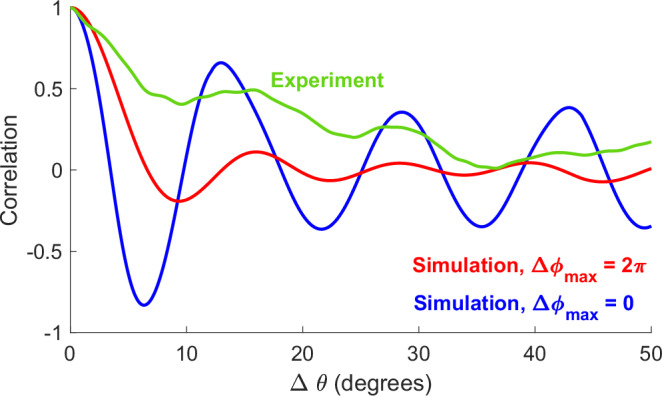

Figure 2 depicts typical results of such simulations with an ideal phase-only metasurface, showing the variation of C(Δθ) for two extreme cases: when the phase modulation range Δϕmax is zero (i.e., no variation at all across the metasurface) and 2π (the full range of possible values for each pixel). From these results, we observe that the average angular correlation oscillates when the metasurface’s modulation range is limited, showing large correlation even at large values of Δθ. On the other hand, when the metasurface has full 2π phase control, the average correlation quickly decays to zero and stays near zero with increasing Δθ, showing that the dynamic range of the metasurface plays a critical role in generating wavefronts with low angular coherence.

Fig. 2. Angular correlation characterization.

Average correlation function at calculated according to Equation (2) at 145 GHz and varying angular separation values for an ideal phase-only metasurface with a full range of phase modulation (Δϕmax = 2π, red), no phase modulation (Δϕmax = 0, blue), and measured using the real metasurface (green). In the simulations, the pixels of the metasurface are assigned randomized phase responses within the allowed range: [0, Δϕmax], and then the complex E-field E(θ) is calculated. For Δϕmax = 2π, the correlation function is averaged over 1000 randomly chosen configurations. The experimental data is measured and averaged over 10 configurations.

Having established the average correlation behavior in such extreme cases, we then evaluate the low-coherence wavefront generation capability of the metasurface used in our experiments, by applying the same correlation function to experimentally measured wavefronts (green curve in Fig. 2). These experimental results show weaker oscillatory features than the Δϕmax = 0 simulation, as well as a slower correlation decay compared to the Δϕmax = 2π simulation. In other words, the experimental result exhibits behavior that is intermediate between the two simulated cases.

These results call attention to the consequences of the limited phase modulation range of most metasurface devices, noted above. Although an ideal metasurface can produce a very low-coherence wavefront, the real devices achieve a slower decay to zero correlation. This slower decay ultimately limits the ability of such devices to achieve high-accuracy localization15,16. To overcome this limitation, we consider the possibility that our incident wave may be spectrally broadband, so that we can exploit not only low spatial coherence at a single frequency but also low correlation between different frequency components.

Broadband characterization

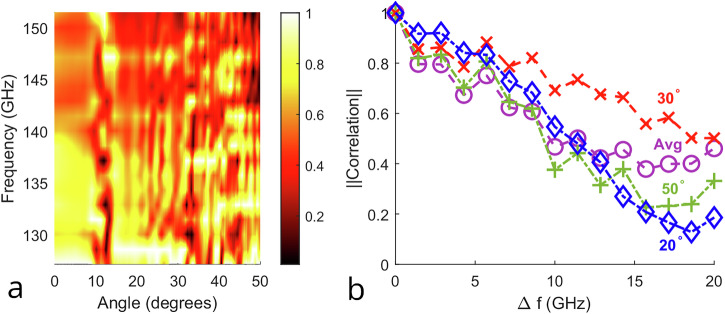

As noted previously, the scattering function Aeiϕ of the pixels is frequency-dependent. Consequently, a single bias voltage corresponds to a diverse set of scattering functions. This frequency-diverse behavior of the metasurface is a critical enabler of generating low-coherence wavefronts simultaneously across various frequencies when a broadband source illuminates the surface. Fig. 3a presents an example, generated by illuminating the metasurface with a broadband input, with a single fixed (randomly chosen) set of voltages applied to the pixels. The vertical striations in this heatmap suggest some correlated behavior across frequency. So, as above in Fig. 2, we can quantify the correlation decay. Here, instead of calculating correlation over a set of angular separation values of the same wavefront, we calculate it across different wavefronts generated simultaneously at different frequencies, separated by Δf, at a fixed angular location. We then average this behavior over multiple random voltage configurations. Fig. 3b shows the results for several fixed angular locations, as well as the average. These results show that the frequency-diverse response of the metasurface, combined with a broadband source signal, can generate a set of wavefronts that exhibit decorrelation across both spectral and spatial dimensions.

Fig. 3. Wideband wavefront characterization.

a Normalized linear amplitude values at varying angles over a 24.3 GHz bandwidth generated by a metasurface configured to generate low-coherence wavefronts as characterized in Equation (1), with a particular fixed (but randomly chosen) set of control voltages applied to the pixels of the device. To emphasize the frequency decorrelation at each angle, the broadband signal obtained at each angle is normalized independently. The frequency-diverse response of the metasurface is evident in the random variation of the heatmap along the vertical direction. b The absolute value of correlation calculated at varying frequency separation values, with a frequency step size of 1.43 GHz (determined by the spectral resolution of the measurement apparatus). Three representative curves are shown for specific angular locations (blue at 20°, red at 30°, green at 50°), while the purple curve shows the average.

We note that while the results in Fig. 3b demonstrate the average behavior of multiple metasurface configurations, it would also be of interest to study the diversity of the behavior across different configurations. On the other hand, due to the large number of possible configurations (~1037) and the requirement of identifying the subset of these configurations that are valuable for the purposes of this work, we defer this exploration to future work.

Angular localization

In the preceding sections, we demonstrated a method to generate wavefronts that exhibit decorrelation in both spatial and spectral domains. Next, we consider the use of these dynamically reconfigurable low-coherence broadband wavefronts for sensing. We envision that a wireless communication node could use these wavefronts as beacons to enable the angular localization of a target receiver. Specifically, spatial decorrelation enables the unique characterization of different angles within the field of view, while spectral decorrelation enables the expansion of this characterization to many distinct frequencies, thus creating a wide “feature” space. If we discretize the angles within the transmitter’s field of view to K different values, Θ = {θ1, θ2, . . . , θK}, then each of the F frequency components within the transmitted bandwidth {f1, f2, . . . fF} corresponds to an element h(f, θ) of a one-shot signature codebook HKF, which can be pre-characterized, and used by the receiver to perform an angle-of-departure (AoD) estimation.

A user located at an angle of departure ϕ receiving the broadband signal can obtain an estimate of the angle of departure, ϕ*, by identifying the closest pre-characterized codebook signature h(θ) using a simple minimization procedure:

| 3 |

We emphasize that this is a low-latency measurement since all of the signatures h(fj, ϕ) are transmitted simultaneously.

Furthermore, in scenarios with low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) or bandwidth limitations, we can perform repeated measurements to improve the accuracy of the localization result. By changing the P voltages applied to the metasurface columns from one random set to a different random set, we reconfigure the metasurface to produce a different set of wavefronts, also exhibiting low coherence but distinct from the first set. We can repeat this procedure T times, using voltage configurations . Thus, by generating new sets of signatures ht(fj, ϕ), (t = 1, 2, . . . , T) sequentially, we expand our codebook from frequency-domain only (HKF) to both frequency and time (HKFT), thus enabling the scaling of estimation accuracy in both domains.

Given the limited ability of metasurfaces to produce low-coherence wavefronts due to their limited modulation range, as characterized above, the efficacy of this localization procedure must be demonstrated. The spatial correlation decays (see Fig. 2) suggest an average speckle spot size of a few degrees, so it is not obvious that one could achieve sub-degree precision in angular localization. Yet, the ability to exploit broadband signals offers an opportunity that warrants further study.

To evaluate the performance, we conduct experiments using a time-domain THz spectroscopy system32. A broadband beam with a nearly ideal Gaussian spatial profile illuminates the metasurface at normal incidence, and a receiver detects the scattered low-coherence wavefront, as a function of angle, in a transmission geometry. Due to the low power of time-domain THz systems, these measurements are carried out at a small scale over a relatively short range; the general approach, however, is scalable with higher power to arbitrary transmitter–receiver distances. We can estimate the angle of departure using these measured signals, discretized with 0.1° resolution, via Equation (3). We perform one set of measurements to build the codebook using 10 randomly chosen voltage sets, and then repeat the measurements using the same voltage sets as a test measurement. We compute the error between the ground-truth angular position of the receiver and the estimated value, using different numbers of spectral components (codebook bandwidth) and numbers of measurements (codebook time steps).

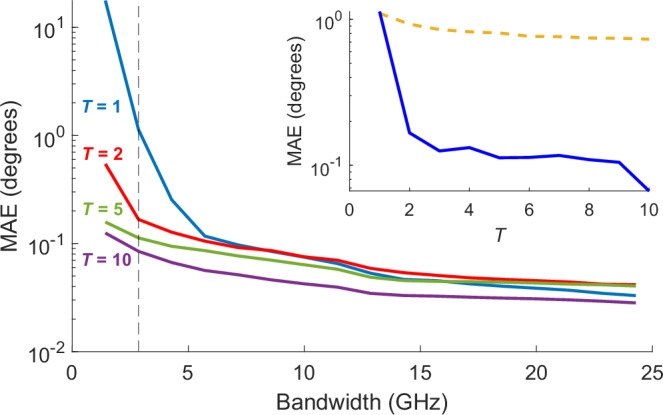

Figure 4 shows the mean absolute error (MAE) as a function of codebook bandwidth, where each curve corresponds to a different number of iterated measurements (T). Even for a single measurement (T = 1), and despite the correlated behavior across angular separations of a few degrees (Fig. 2) and across spectral separation of a few GHz (Fig. 3b), we nevertheless observe that the error decreases rapidly with increasing number of spectral components. For instance, the MAE decreases from 17.7° with only two complex wavefront components in the codebook to 0.033° with 18 components across the spectral range 127–152 GHz. We note that an MAE of less than 0.1° represents more than one order-of-magnitude improvement compared to the state of the art in AoD estimation15,24–26.

Fig. 4. Angle estimation with varying time and frequency resources.

The mean absolute error (MAE) achieved with varying bandwidth values used to construct the angle estimation codebook. By varying the codebook variable T, we perform angle estimation ranging from one-shot to 10-shot (see “Methods” section). In the figure, the blue, red, green, and purple curves represent T = 1, 2, 5, and 10, respectively. The MAE is calculated by averaging the estimation error for all beacons that correspond to the entire FoV and then averaging over 100 independent noise observations at a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 30 dB. As the collected signals are discretized with 0.1∘ resolution, the error for estimation is also calculated with 0.1∘ discretization, e.g., estimations of signals assigned in the correct angle “bin" correspond to zero error. The inset shows the dramatic improvement in estimation error resulting from repeated measurements (increasing T) with a solid blue curve. Also shown (dashed yellow curve) is the improvement that would result if the only effect of repeated measurements was to improve the overall SNR through averaging.

Furthermore, as we enable sequential randomization of the wavefronts by reconfiguring the metasurface, we observe (inset of Fig. 4) that the estimation error is also improved with increasing T. This improvement is more pronounced at lower bandwidth values (<5 GHz) since there are only a few (<5) frequency components in the beacon. While still notable, the improvement is less pronounced at higher bandwidth, where the estimation accuracy with 10 shots reaches saturation around 0.03° with 24.3 GHz bandwidth. However, it should be noted that the saturation is dependent on other factors such as the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), as discussed below. Improving estimation error through increasing bandwidth and number of shots provides the users with a time-frequency trade-off, thereby allowing accurate angle estimation even in bandwidth-contentious networks.

Noise robustness

The above analysis assumes a particular level of noise (SNR = 30 dB), and our results must clearly depend on this value since the received signal is a noisy and attenuated version of the pre-characterized beacon h(θ). To evaluate the robustness of our approach against noise, we compare the MAE values at varying SNR levels for one-shot (T = 1) and 10-shot (T = 10) estimation (Fig. 5). Here, degradation in estimation accuracy with decreasing SNR occurs much faster for one-shot estimation compared to 10-shot. Specifically, for an SNR of 5 dB, one-shot estimation results in 2.5° MAE, an order-of-magnitude higher than that of 10-shot estimation. On the other hand, at 30 dB SNR, the respective MAE values are quite similar (see “Methods” section for details on added noise).

Fig. 5. Noise robustness of angle estimation.

Mean absolute error (MAE) values (on a log scale), calculated over the entire field of view using the full 24.3 GHz codebook bandwidth, at varying signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) levels. Red and blue curves correspond to one-shot and 10-shot (T = 1 and 10), respectively. Error bars represent the minimum and maximum errors within 100 independent estimations. The inset shows two example sets of estimated angle values against ground truth at 5 dB SNR for one-shot and 10-shot estimation.

To understand how a low SNR affects individual angle estimations, we show in the inset of Fig. 5 two example sets of estimations against the ground truth for one-shot and 10-shot estimation methods, for an SNR of 5 dB. Here, a perfectly accurate estimation profile aligns with y = x, and our estimation profiles at high SNR = 30 dB for one-shot and multi-shot methods closely follow this trend (the 30 dB SNR results are shown in Supplementary Note 2 and Fig. S3). However, at a much lower 5 dB SNR (inset), clear differences are observable. The estimated values with 10 shots (blue points) are still close to the ground truth, scattered near y = x. In contrast, the single-shot estimations (red points) exhibit some scatter throughout the field of view. In particular, two distinct patterns can be identified: many of the estimated points are clustered near the y = x ground truth, while those that are not appear to be scattered roughly symmetrically about the opposite line y = −x. This pattern reflects an underlying mirror symmetry in the generated wavefronts. This symmetry has one obvious source: the edges of the metasurface. As noted above, the metasurface consists of a series of adjacent parallel columns, which collectively define a rectangular aperture through which the normally incident Gaussian beam is diffracted. This aperture diffraction pattern, symmetric around θ = 0°, is superimposed on the spatially random fluctuations induced by the randomly configured metasurface. This source of left-right correlation could be eliminated through careful design of both the metasurface and its packaging, as well as more careful apodization of the input beam. Yet, despite this effect, we emphasize that our method can still achieve a remarkable MAE of only 0.16° with a 10-shot estimation protocol, even with a low SNR of 5 dB.

Conclusions

We have described a novel method to dynamically generate broadband wavefronts with low coherence in both angle and frequency, and demonstrated that this capability can enable low-latency estimation of angle of departure, with unprecedented accuracy. A key aspect of this innovation lies in the repeatable reconfigurability of the metasurface. Unlike a wireless channel in a rich multi-path scattering environment, here the low-coherence wavefront can be repeatably generated. This enables the idea of using a pre-characterized codebook for localization. This, of course, relies on the fact that the channel in our envisioned use case is dominantly line-of-sight, with little contribution from multi-path effects, which is often the case for frequencies above 100 GHz20.

The low-coherence wavefronts employed in our work should be contrasted with the smooth convex angle-frequency function of a THz leaky-wave antenna (LWA), which has been used in prior work24–26,33,34 to demonstrate a low-latency (one-shot) localization, also in a line-of-sight channel, by exploiting the dispersive angle-frequency coupling. That approach results in limited accuracy due to the strongly correlated response at adjacent angles, and cannot be significantly improved by using sequential measurements. Similarly, other static structures15,16,35 discussed previously for one-shot localization are not capable of carrying out dynamic wavefront generation. In contrast, the reconfigurability of our metasurface allows us to produce a sequence of distinct low-coherence wavefronts, leading to dramatic improvements with iterated measurement. Thus, our approach offers a unique ability to engineer the trade-off between the latency (number of shots) and localization accuracy, and achieves extremely high accuracy even for a relatively small number of iterations (≤10) and even in relatively poor SNR environments. Indeed, this method can achieve a mean absolute error better than 1° even in a channel with an SNR of 0 dB, and better than 0.1° at higher SNR in a single shot. Due to the fact that we exploit the rapid correlation decay in both space and frequency, we not only achieve a finer-resolution system, but also demonstrate these remarkably precise values for localization, even though the angular correlation function (for a given frequency) decays much more slowly.

We also note that LWAs have been proposed in prior work as promising candidates for communication networks25,36–38. However, the communication functionality of this architecture is severely limited by its dispersive and non-reconfigurable radiation pattern. In contrast, the reconfigurable architecture in our work unlocks critical integrated communication and sensing capabilities that were previously not available through LWAs.

Finally, we emphasize that our experimental demonstrations employ a metasurface with a relatively limited phase modulation range of only Δϕmax ≈ 50°. The achieved accuracy and the rate of convergence with increasing bandwidth both depend on the characteristics of the metasurface scattering function , including both the range of phase modulation and its frequency dependence. The square SRR configuration employed in our system does not offer the largest demonstrated range of values for these parameters30, so further improvements are clearly possible. Furthermore, since the wavefronts generated in our system are broadcast, the same principle would work in the presence of multiple receivers: each receiver, presumably at a different location from others, would be able to identify its corresponding angle of departure without interference effects. Similarly, as the constructed codebooks would be affected by changes to metasurface-to-receiver distance, we believe that this could be further exploited for simultaneous angle and distance estimation with a further optimized pool of metasurface configurations and the receiver’s estimation algorithm. Consequently, studying the characteristics of the generated wavefronts at varying propagation distances will be an integral part of expanding this work. In addition, studying the wavefronts in azimuth and elevation jointly will be critical to accurately model the three-dimensional field of view, thus enabling full positioning of the receiver. As such, we believe these are interesting avenues to explore in future work.

Nevertheless, it is remarkable that such precise results can be obtained even with significant limitations on the modulation parameters.

Methods

Experimental setup

We use a LUNA T-Ray 5000 Time-Domain Terahertz Spectroscopy system with a single transmitter and receiver producing directional, approximately Gaussian beams32. In the setup (shown in Supplementary Fig. S2), the metasurface is placed 11 centimeters away from the stationary transmitter and is centered on top of a motorized stage to enable fine-resolution angular positioning. The receiver is placed 15 centimeters away from the metasurface on a rail attached to the motorized stage. Due to the ultra-low power architecture of the system (~10 μW spread across ~2 THz bandwidth25), the limited modulation efficiency of the metasurface, and the fact that the source power is scattered over a wide angle range, the distances are relatively small, to avoid the effect of experimental noise on the generated random spectral patterns.

To generate the wavefronts, we obtain an amplitude-voltage curve at the resonance frequency, 145 GHz, according to the experimentally observed amplitude response-bias voltage relation in Supplementary Fig. S1b. Then, we select 16 amplitude response values randomly, with a uniform distribution, from the range of possible amplitude response values. Using the previously obtained amplitude-voltage curve, we then convert these 16 amplitude values to their corresponding voltage values, which make up a single voltage configuration. By applying this voltage configuration to the metasurface’s pixels, we generate the described low-coherence wavefronts upon excitation from the wideband THz source. We select 10 different configurations to evaluate the localization performance at up to T = 10 shots.

To collect the data, we first apply the designed set of voltages to the functioning pixels (columns) of the metasurface using a National Instruments DAC card (NI PCIe-6738). Then, we rotate the receiver across the metasurface’s field of view Θ = [−50°, 50°] with 0. 1° resolution and collect the received time-domain signal at each location, with the signal averaged 100 times to ensure high experimental SNR. Time-domain waveforms are Fourier transformed to extract spectral information (amplitude and phase of the measured electric field) for all frequencies within the bandwidth of the measured signals. For the measurements described here, we focus only on a subset of this broad spectrum, corresponding to the range 127–152 GHz, the range over which the metasurface provides an amplitude modulation tunable with applied DC bias (see Supplementary Fig. S1b). For each set of voltages, the same dataset is collected twice this way across the entire field of view, once for codebook construction and the other as a test set.

Signal processing

For the calculation of the correlation function in Fig. 2, near-zero angles are excluded from the ensemble averaging to avoid the effect of unmodulated signal leakage. For angle estimation (Figs. 4 and 5), we add white Gaussian noise to all frequency components of each received signal in the test set. The SNR is defined with respect to the average power from all frequency components of a given signal. For the analysis in Fig. 4, the added noise is adjusted with SNR = 30 dB. In the inset, the SNR is 30 dB for the curve depicting the improvement from adding shots (blue), while it ranges between 30 dB and 35 dB for the curve depicting the improvement from simple averaging (yellow dashed), reflecting the SNR change resulting from such averaging. For Fig. 5, it is varied between 0 and 30 dB, and the estimation profiles in the inset are achieved at 5 dB. As an estimation algorithm, we use the Least Squares Orthogonal Matching Pursuit (LS-OMP)39 algorithm with known sparsity (1-sparse), which is equivalent to the least squares error comparison between the received signal and each column of the codebook. We estimate the angle of each received signal in the test set and calculate the mean absolute error (MAE) across the field of view, then repeat 100 times with different noise observations to calculate the mean and variance of MAE.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

B.B., J.L., and E.K.’s research was supported by Cisco and Intel, by NSF grants 2433923, 2402783, and 2211618, and by ARO DURIP grant W911NF-23-1-0340. D.M.’s research was funded in part by grants from the US National Science Foundation (grant numbers 2402781, 2433924, 2211616, and 1954780). This work was performed, in part, at the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Los Alamos National Laboratory (Contract 89233218CNA000001) and Sandia National Laboratories (Contract DE-NA-0003525).

Author contributions

H.C., C.C., S.A., and M.P.L. fabricated the metasurface. B.B., J.L., D.M.M., and E.W.K. conceived of the experiments. B.B. and J.L. performed the experiments and conducted the simulations. B.B., J.L., H.C., D.M.M., and E.W.K. contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Engineering thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: [Rosamund Daw].

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s44172-025-00502-6.

References

- 1.Dowski, E. R. Jr & Johnson, G. E. Wavefront coding: a modern method of achieving high-performance and/or low-cost imaging systems. In Current Developments in Optical Design and Optical Engineering VIII, vol. 3779 (eds Fischer, R. E. & Smith, W. J.) 137–145 (SPIE, 1999).

- 2.Singh, A. et al. Wavefront engineering: realizing efficient terahertz band communications in 6G and beyond. IEEE Wirel. Commun.31, 133–139 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen, R., Zhou, H., Moretti, M., Wang, X. & Li, J. Orbital angular momentum waves: generation, detection, and emerging applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor.22, 840–868 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohammadi, S. M. et al. Orbital angular momentum in radio-a system study. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag.58, 565–572 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy, I. V. et al. Ultrabroadband terahertz-band communications with self-healing Bessel beams. Commun. Eng.2, 70 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerboukha, H., Zhao, B., Fang, Z., Knightly, E. & Mittleman, D. M. Curving THz wireless data links around obstacles. Commun. Eng.3, 58 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodman, J. Statistical Optics (Wiley, 2015).

- 8.Wei, M. et al. Physical-level secure wireless communication using random-signal-excited reprogrammable metasurface. Appl. Phys. Lett.122, 051704 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hassan, F. et al. RMDM: using random meta-atoms to send directional misinformation to eavesdroppers. In 2023 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security (CNS) 1–9 (IEEE, 2023).

- 10.Staat, P. et al. Intelligent reflecting surface-assisted wireless key generation for low-entropy environments. In 2021 IEEE 32nd Annual International Symposium on Personal, Indoor and Mobile Radio Communications (PIMRC) 745–751 (IEEE, 2021).

- 11.Ji, Z. et al. Secret key generation for intelligent reflecting surface assisted wireless communication networks. IEEE Trans. Vehicular Technol.70, 1030–1034 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stantchev, R. I. et al. Compressed sensing with near-field THz radiation. Optica4, 989–992 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan, W. L. et al. A single-pixel terahertz imaging system based on compressed sensing. Appl. Phys. Lett.93, 121105 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen, Y. C. et al. Terahertz pulsed spectroscopic imaging using optimized binary masks. Appl. Phys. Lett.95, 231112 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, M. S. et al. Frequency-diverse antenna with convolutional neural networks for direction-of-arrival estimation in terahertz communications. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol.14, 354–363 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbasi, M. A. B., Fusco, V., Yurduseven, O. & Fromenteze, T. Frequency-diverse multimode millimetre-wave constant-ϵr lens-loaded cavity. Sci. Rep.10, 22145 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei Wang, J. et al. High-precision direction-of-arrival estimations using digital programmable metasurface. Adv. Intell. Syst.4, 2100164 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, J. W. et al. Polarization and direction-of-arrival estimations based on orthogonally polarized digital programmable metasurfaces. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys.56, 465001 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoang, T. V., Fusco, V., Abbasi, M. A. B. & Yurduseven, O. Single-pixel polarimetric direction of arrival estimation using programmable coding metasurface aperture. Sci. Rep.11, 23830 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jornet, J., Knightly, E. & Mittleman, D. Wireless communications sensing and security above 100 GHz. Nat. Commun.14, 841 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen, H. et al. A tutorial on terahertz-band localization for 6G communication systems. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor.24, 1780–1815 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, X. & Caloz, C. Direction-of-arrival (DOA) estimation based on spacetime-modulated metasurface. In 2019 IEEE International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation and USNC-URSI Radio Science Meeting 1613–1614 (IEEE, 2019).

- 23.Fang, X. et al. Accurate direction-of-arrival estimation method based on space-time modulated metasurface. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag.70, 10951–10964 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amarasinghe, Y., Mendis, R. & Mittleman, D. M. Real-time object tracking using a leaky THz waveguide. Opt. Express28, 17997–18005 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghasempour, Y., Shrestha, R., Charous, A., Knightly, E. & Mittleman, D. M. Single-shot link discovery for terahertz wireless networks. Nat. Commun.11, 2017 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kludze, A. et al. Quasi-optical 3D localization using asymmetric signatures above 100 GHz. In Proc. 28th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking 120–132 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2022).

- 27.Karl, N. et al. An electrically driven terahertz metamaterial diffractive modulator with more than 20 dB of dynamic range. Appl. Phys. Lett.104, 091115 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen, H.-T. et al. A metamaterial solid-state terahertz phase modulator. Nat. Photonics3, 148–151 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng, H. et al. A review of terahertz phase modulation from free space to guided wave integrated devices. Nanophotonics11, 415–437 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang, Y. et al. Large phase modulation of thz wave via an enhanced resonant active HEMT metasurface. Nanophotonics8, 153–170 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim, J. Y. et al. Full 2π tunable phase modulation using avoided crossing of resonances. Nat. Commun.13, 2103 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koch, M., Mittleman, D., Ornik, J. & Castro-Camus, E. Terahertz time-domain spectroscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim.3, 48 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saeidi, H., Venkatesh, S., Lu, X. & Sengupta, K. THz prism: one-shot simultaneous localization of multiple wireless nodes with leaky-wave THz antennas and transceivers in CMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits56, 3840–3854 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lees, H., Headland, D., Murakami, S., Fujita, M. & Withayachumnankul, W. Terahertz radar with all-dielectric leaky-wave antenna. APL Photonics9, 036107 (2024).

- 35.Zhou, T. et al. Short-range wireless localization based on meta-aperture assisted compressed sensing. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech.65, 2516–2524 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yeh, C.-Y., Ghasempour, Y., Amarasinghe, Y., Mittleman, D. M. & Knightly, E. W. Security and angle-frequency coupling in terahertz WLANs. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw.32, 1524–1539 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dasala, K. P. & Knightly, E. W. Multi-user terahertz WLANs with angularly dispersive links. In Proc. Twenty-Third International Symposium on Theory, Algorithmic Foundations, and Protocol Design for Mobile Networks and Mobile Computing, MobiHoc ’22 121–130 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2022).

- 38.Ghasempour, Y., Amarasinghe, Y., Yeh, C.-Y., Knightly, E. & Mittleman, D. M. Line-of-sight and non-line-of-sight links for dispersive terahertz wireless networks. APL Photonics6, 041304 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tropp, J. A. & Gilbert, A. C. Signal recovery from random measurements via orthogonal matching pursuit. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory53, 4655–4666 (2007). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.