Abstract

Integrated lipidomics and flavoromics were employed to elucidate the mechanism of antioxidants in mitigating flavor deterioration of fish oil from silver carp viscera. Results demonstrated that antioxidants effectively mitigated the progression of lipid oxidation indicators, including acid value, peroxide value, p-anisidine value, total oxidation value, polar components, and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances. Lipidomics revealed that tert-butylhydroquinone (TBHQ) and propyl gallate (PG) significantly attenuated the oxidative degradation of triacylglycerols (TG), diacylglycerols (DG), and phosphatidylethanolamines (PE) containing unsaturated fatty acids. Flavoromics identified that these antioxidants markedly suppressed the formation of six characteristic off-flavor compounds: 1-octen-3-ol, N-nonyl aldehyde, (E, E)-2,4-heptadienal, (E)-2-nonenal, (E)-2-decenal, and eugenol, thereby preventing the development of fishy odor. Multivariate statistical analysis established PE, TG, and DG molecular species as critical precursors in the antioxidant-mediated suppression of volatile off-flavors generation. The findings offer novel mechanistic insights into the dual protective role of antioxidants in maintaining lipid integrity and preserving flavor quality.

Keywords: Fish oil, Storage, Antioxidant, Lipid oxidation, Volatile organic compounds

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Antioxidants effectively mitigated the progression of lipid oxidation of fish oil.

-

•

TBHQ and PG attenuated the oxidative degradation of TG, DG, and PE.

-

•

Antioxidants suppressed the formation of six characteristic off-flavors of fish oil.

-

•

TG, DG and PE were precursors in the antioxidant-mediated suppression of off-flavors.

1. Introduction

Fish oil is a lipid-rich extract mainly derived from the tissues of fatty fish. Due to its high concentration of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), especially eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), it has received extensive attention from scientific and commercial fields (Khoshnoudi-Nia et al., 2022). The benefits of these long-chain fatty acids for cardiovascular health, neurological function, and regulation of inflammatory responses have been well documented (Liao et al., 2022). However, the structural feature that confers these health benefits, multiple double bonds in the carbon chain, makes fish oil particularly susceptible to oxidative degradation. The oxidation process is initiated through three main pathways: Auto-oxidation (spontaneous reaction with oxygen in the atmosphere), photo-oxidation (light-induced formation of free radicals), and enzymatic oxidation (Clarke et al., 2021). This complex chain reaction proceeds through initiation, propagation, and termination stages. It generates primary oxidation products (peroxides and hydroperoxides), which subsequently decompose into secondary products, including aldehydes, ketones, and short-chain fatty acids. Notably, EPA and DHA, containing five and six double bonds, respectively, are particularly vulnerable to oxidation, with the reaction rate increasing exponentially with each additional double bond (Zheng et al., 2024).

The incorporation of antioxidants is a widely recognized strategy to mitigate lipid oxidation and prolong the shelf life of fish oil. Due to the high content of PUFAs, fish oil is particularly susceptible to oxidative degradation, which compromises its nutritional quality and generates undesirable off-flavors. Antioxidants function by interrupting free radical chain reactions or chelating pro-oxidative metal ions, thereby effectively delaying the onset of lipid peroxidation (Nawaz et al., 2024). This approach not only preserves the oxidative stability of fish oil during processing and storage but also aligns with industry demands for maintaining product integrity and extending commercial viability. Antioxidants (e.g., tert-butylhydroquinone, TBHQ; propyl gallate, PG; and tea polyphenol, TP) are commonly employed to mitigate lipid oxidation (Cho et al., 2025; Ma et al., 2025; Xu et al., 2025). However, their mechanisms of action in preserving lipid stability and flavor integrity remain poorly understood. Traditional studies have focused on monitoring primary oxidation markers (e.g., peroxide value, POV) or secondary products (e.g., thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances, TBARS) (de Oliveira et al., 2024), yet these approaches fail to capture the complex interplay between lipid degradation pathways and volatile flavor dynamics. Furthermore, the unique composition of silver carp viscera oil, characterized by high phospholipid (PL) content and pro-oxidant residues from visceral tissues, demands tailored antioxidant strategies to address its distinct oxidative vulnerabilities.

Recent advances in lipidomics and flavoromics offer unprecedented opportunities to unravel the molecular mechanisms underlying flavor deterioration. Lipidomics, a rapidly evolving branch of metabolomics, focuses on the comprehensive analysis of lipid species within biological systems to elucidate their structural diversity, metabolic pathways, and functional roles. Utilizing advanced analytical techniques such as mass spectrometry (MS) coupled with chromatographic separation (e.g., liquid chromatography), lipidomics enables the high-throughput identification and quantification of numerous lipid molecules, including glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids, triacylglycerols, and fatty acids, with high sensitivity and specificity (Xue et al., 2024). Flavoromics, a specialized subfield of flavor science, focuses on the systematic profiling and functional analysis of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that contribute to the aroma characteristics of food. This technology utilizes a suite of cutting-edge analytical platforms, such as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS), two-dimensional GC (GC × GC-TOF/MS), proton-transfer reaction mass spectrometry (PTR-MS), and olfactometry. The integrated approach enables the precise identification and quantification of trace-level VOCs, including aldehydes, esters, terpenes, and sulfur-containing compounds (Cai et al., 2024). Therefore, lipidomics enables the comprehensive profiling of oxidized triacylglycerols (TGs), phospholipids (PLs), and free fatty acids (FFA), while flavoromics identifies critical VOCs linked to sensory defects. Integrating these approaches can bridge the gap between biochemical oxidation processes and consumer-perceived quality, providing a holistic view of antioxidant efficacy.

This study investigates the dual role of antioxidants in suppressing lipid oxidation and flavor deterioration in silver carp viscera oil through an integration method of lipidomics and flavoromics. Using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS) and GC–MS, we systematically analyze the temporal changes in lipid species and flavor-active volatiles under accelerated storage conditions, with or without antioxidant intervention. By correlating lipid degradation pathways with VOC profiles, we aim to elucidate how antioxidants modulate oxidative cascades and preserve flavor stability at a molecular level. The findings will advance the rational design of antioxidant systems for freshwater fish oils, enhancing their application in functional foods and nutraceuticals while reducing waste from underutilized fishery byproducts.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Fish oil antioxidant treatment

Fresh live silver carp were purchased from a Rainbow Supermarket, Nanchang, China. Fishes were procured, euthanized by percussive stunning to the head, and eviscerated. Crude fish oil was extracted from the viscera using n-hexane solvent extraction. The crude oil subsequently underwent a refining process comprising degumming, deacidification (neutralization), decolorization (bleaching), and deodorization to produce refined fish oil conforming to national standards (Li et al., 2025). The Schaal oven accelerated oxidation test was conducted to accelerate the oxidation of fish oil at 60 °C for a 20-day period (Wang, Liu, et al., 2024; Wang, Cui, et al., 2024). Accurately 500 g of refined silver carp visceral fish oil was portioned into 50 mL conical flasks (50 g per flask). Then 0.02 % TBHQ, 0.02 % PG, and 0.02 % TP were respectively added to different flasks, and fish oil without antioxidant was the control group (CON) (Beker et al., 2016; Esazadeh et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2025). The TP was purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. with a purity of 98 %. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate was the most effective active ingredient in tea polyphenols (Zhao et al., 2024), with epigallocatechin-3-gallate having the highest content, accounting for approximately 65 % of the total catechins (Chanphai et al., 2018). After sealing, the samples were placed in a light-protected oven maintained at 60 ± 1 °C for accelerated oxidation. The flasks were shaken every 24 h and randomly positioned within the oven to ensure uniform heating. Oil samples were randomly collected from the oven on days 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 16, and 20 during the incubation period. The obtained oil samples were stored in brown glass bottles at −20 °C in a freezer for subsequent analysis.

2.2. Determination of oxidation indexes

The acid value (AV) was determined according to the cold solvent indicator titration method specified in GB 5009.229-2016. The peroxide value (POV) was measured following the titration method outlined in GB 5009.227-2016. The determination of p-anisidine value (p-AV) was conducted according to the National Standard of the People's Republic of China GB/T 24304-2009 “Animal and vegetable fats and oils-determination of p-Anisidine value”. The total oxidation value (TOTOX) was calculated as: TOTOX = 2 × POV + AV. Polar compounds were measured using a Testo analyzer. The probe was inserted into the oil bath, with the immersion depth positioned midway between the minimum and maximum marks. The stabilized reading after equilibration was recorded as the polar component content of the thermally oxidized oil. Malondialdehyde (MDA) content was determined following the National Food Safety Standard GB 5009.181-2016 “Determination of Malondialdehyde in Foods”.

2.3. Lipidomics determination

Lipid extraction was performed based on the method described by Wang, Liu, et al. (2024) and Wang, Cui, et al. (2024) with minor modifications. Briefly, 50 mg of fish oil was accurately weighed into a 2 mL centrifuge tube. Sequentially, 280 μL of extraction solvent (methanol:water = 2:5, v/v), 400 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), and one grinding bead (6 mm diameter) were added. The mixture was subjected to cryogenic grinding at −10 °C and 50 Hz for 6 min, followed by low-temperature ultrasonic extraction at 5 °C and 40 kHz for 30 min. After static incubation at −20 °C for 30 min, the mixture was centrifuged at 13,000 ×g and 4 °C for 15 min. Subsequently, 350 μL of the supernatant was collected and dried under nitrogen gas. The residue was reconstituted with 100 μL of resuspension solution (isopropanol: acetonitrile = 1:1, v/v), vortexed for 30 s, and sonicated in an ice-water bath at 40 kHz for 5 min. After centrifugation at 13,000 ×g and 4 °C for 10 min, the supernatant was collected for analysis.

Quality control (QC) samples were prepared by pooling equal volumes of all sample extracts. During the experiment, one QC sample was inserted every 10 experimental samples to monitor the reproducibility of the analytical workflow.

The UPLC-MS/MS parameters were optimized based on the method by Mitrowska et al. (2023), and mass spectrometry analysis was conducted following Chen, He, et al. (2024) and Chen, Zhang, et al. (2024). Chromatographic conditions: Mobile phase A: 10 mmol/L ammonium acetate in 50 % acetonitrile (aqueous) containing 0.1 % formic acid. Mobile phase B: 2 mmol/L ammonium acetate in acetonitrile/isopropanol/water (10/88/2, v/v/v) containing 0.02 % formic acid. Gradient elution program: 0–4 min: 35 %–60 % B; 4–12 min: 60 %–85 % B; 12–15 min: 85 %–100 % B; 15–17 min: 100 % B (isocratic); 17–18 min: 100 %–35 % B; 18–20 min: 35 % B (equilibration). Other parameters: Injection volume: 2 μL; flow rate: 0.40 mL/min; column temperature: 40 °C. Mass spectrometry parameters: Ionization modes: Positive and negative ion switching. Spray voltages: +3000 V (positive mode), −3000 V (negative mode). Scan range: m/z 200–2000. Gas settings: Sheath gas pressure: 60 psi; auxiliary gas pressure: 20 psi. Ion source temperature: 370 °C. Collision energies: Stepped energies of 20, 40, and 60 V. Data acquisition: Full MS and MS/MS spectra were recorded simultaneously in both ionization modes. Raw UPLC-MS data were processed using the lipid search software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, CA, USA) to generate a data matrix containing lipid species, retention times, m/z values, and peak intensities. Lipid identification was achieved by matching MS1 and MS2 spectra against metabolic databases. The raw data were imported into LipidSearch software (Thermo Fisher, USA) for lipidomic processing and database searching. During the database search, the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) threshold was set to ≥3. Molecular formula prediction was performed based on the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of precursor ions from the first-level mass spectrometry, along with information on possible adduct ions and isotope peaks. Potential metabolites were identified by matching with database entries within a mass deviation of 10 ppm. Secondary identification of metabolites was achieved by matching characteristic lipid ions and specific fragments with database information on fragment ions, collision energy, and ion fragment intensity. The database search thresholds were set as follows: m-score threshold: 5.0; c-score threshold: 2.0; mass tolerance for precursor ions: 10 ppm.

Data processing: Missing value handling: Metabolites with >20 % missing values in any sample group were excluded. The remaining missing values were imputed using the minimum observed value. Normalization: Peak intensities were normalized by total sum normalization to mitigate batch effects. Quality control: Variables with a relative standard deviation (RSD) > 30 % in QC samples were removed. Data transformation: Log10 transformation was applied to stabilize variance.

2.4. Determination of volatile compounds

Solid-phase microextraction (SPME) conditions: Volatile compound analysis was performed according to the method by Mascrez et al. (2024) with minor modifications. Briefly, 2.00 g of fish oil sample was accurately weighed into a 15 mL headspace vial and equilibrated at 55 °C in a water bath for 30 min. A SPME fiber was then inserted into the headspace of the vial to adsorb volatile compounds for 30 min. After thermal desorption at 250 °C, the analytes were analyzed using a gas chromatography-mass spectrometer (7890 A/5975, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA).

GC–MS conditions: Column: DB-Wax capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). Injection port: Temperature 250 °C; carrier gas: helium (He); flow rate: 1.0 mL/min; splitless mode. Oven program: Initial temperature 40 °C (held for 3 min), ramped to 240 °C at 5 °C/min, then held for 15 min. Mass spectrometry: Electron ionization (EI) source; ionization energy: 70 eV; ion source temperature: 230 °C; quadrupole temperature: 150 °C.

GC–MS data processing: Unknown compounds were identified by matching mass spectra against the NIST 20 library. Compounds with forward and reverse match factors ≥800 (maximum 1000) were annotated, and their names were reported.

The key flavor compounds in fish oil were analyzed using the odor activity value (OAV) method integrated with variable importance in projection (VIP) analysis, following the protocol established by Li et al. (2024). The OAV was calculated using the formula:

where: Cx: Concentration of the target compound (μg/kg); OTx: Odor threshold of compound x (μg/kg).

2.5. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Experimental data were plotted using Origin 2021 software. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 software with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significant differences were determined by Duncan's test (p < 0.05), and Pearson correlation analysis was subsequently conducted.

3. Results

3.1. Changes in oxidized values of antioxidant-treated fish oil in an oven

As illustrated in Fig. 1(A), the AV of fish oil across all groups exhibited an overall increasing trend during the storage period. The Con group reached an AV of 0.53 mg/g on day 20. In contrast, all antioxidant-treated groups showed significantly lower AV values compared to the Con group on day 20. Specifically, the AV in TP group decreased by 14.24 % (0.45 mg/g), and the PG group decreased by 26.46 % (0.38 mg/g). The TBHQ group demonstrated the most effective inhibition, with an AV of 0.29 mg/g, representing a minimal increase of 0.04 mg/g compared to fresh fish oil. These results indicate that antioxidants effectively suppressed AV elevation during accelerated oxidation, with the efficacy ranking as TBHQ > PG > TP.

Fig. 1.

Changes in oxidative parameters of fish oil treated with different antioxidants during Schaal oven storage. (A) Acid value (AV); (B) Peroxide value (POV); (C) p-Anisidine value (p-AV); (D) Total oxidation value (TOTOX); (E) Polar compounds (PC); (F) Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS).

The POV results are shown in Fig. 1(B). Antioxidants significantly inhibited lipid oxidation in fish oil over the 20-day accelerated storage period, with all treated groups maintaining lower POV values than the Con group. The Con group reached a maximum POV of 34.36 meq/kg, while the TBHQ, PG, and TP groups showed peak values of 10.56 meq/kg (69.28 % reduction), 17.75 meq/kg (48.35 % reduction), and 20.83 meq/kg (39.39 % reduction), respectively. Statistical analysis confirmed that TBHQ provided the strongest inhibition of POV elevation (p < 0.01), followed by PG and TP. The antioxidant efficacy order for POV suppression was TBHQ > PG > TP.

As depicted in Fig. 1(C), p-AV values increased progressively in all groups during storage. TBHQ treatment notably attenuated p-AV elevation, achieving a 69.20 % protective rate (15.70 vs. Con: 50.99). The PG group initially exhibited strong antioxidant activity, with a 53.04 % protective rate (12.80 vs. Con) on day 9, but its efficacy declined over time, yielding only a 37.78 % protective rate (vs. 31.72 % in the Con group) on day 20. The TP group showed the weakest inhibition, with a 29.71 % protective rate (vs. 35.83 % in the Con group), likely due to thermal degradation of TPs (e.g., dehydroxylation and ring-opening reactions) under high-temperature conditions, which reduced their antioxidant capacity. The efficacy order for p-AV suppression was TBHQ > PG > TP.

TOTOX is an integrative indicator that combines the levels of both primary (hydroperoxides) and secondary (aldehydes/ketones) oxidation products. The TOTOX values for all samples are shown in Fig. 1(D). All groups displayed rising TOTOX trends during storage. The Con group reached 119.71 by day 20, whereas antioxidant-treated groups showed markedly lower values: TBHQ (36.82), PG (67.22), and TP (77.49). TBHQ demonstrated the highest protective effect, with PG and TP following in descending order. The antioxidant efficacy for TOTOX inhibition was TBHQ > PG > TP.

As shown in Fig. 1(E), the changes in polar compounds content were smaller and slower in antioxidant-treated groups compared to the Con group. After 20 days of storage at 60 °C, the PC content of TBHQ-treated fish oil increased by only 0.5 % relative to fresh fish oil (pre-storage), demonstrating the most effective inhibition. The PG and TP groups exhibited PC values of 9 % and 9.5 %, respectively, on day 20, indicating comparatively weaker efficacy. These results suggest that antioxidants effectively suppressed polar compound accumulation during storage, with the efficacy ranking as TBHQ > PG > TP.

TBARS values, which quantify carbonyl compounds formed during the late stages of lipid peroxidation and are widely recognized as a key indicator of lipid oxidation. As depicted in Fig. 1(F), all groups showed increasing TBARS trends during storage. However, the antioxidant-treated groups (TBHQ, PG, TP) exhibited significantly slower increases compared to the rapid rise observed in the Con group. On day 20, the MDA content in the TBHQ group reached 5.25 mg/kg, representing a 73.41 % reduction relative to the Con group. The PG and TP groups showed reductions of 63.13 % and 51.00 %, respectively. These findings confirm that antioxidants effectively mitigated TBARS elevation, with the efficacy order being TBHQ > PG > TP.

3.2. Changes in lipidomics of antioxidant-treated fish oil in an oven

Untargeted lipidomics was used in the analysis of lipid composition characteristics in antioxidant-inhibited oven-accelerated oxidized silver carp visceral oil. As shown in Fig. 2(A), there were 1064 lipid metabolites, including 1038 lipid metabolites identified in positive ion mode and 26 lipid metabolites detected in negative ion mode. Based on the international lipid classification standards, these lipids were categorized into five major classes: glycerolipids (GL, 752, 70.68 %), glycerophospholipids (GP, 298, 28.01 %), sphingolipids (SP, 5 species, 0.47 %), fatty acids (FA, 4, 0.38 %), and sterol lipids (ST, 5, 0.47 %). GL and GP constituted the predominant components, collectively accounting for 98.69 % of the total lipid molecular composition. At the subclass level, the lipid profile of silver carp visceral oil was primarily characterized by TG (540, 50.75 %), DG (204, 19.17 %), and PE (196, 18.42 %). As illustrated in Fig. 2(B), the fatty acid composition was primarily classified as follows: PUFAs (34 %, 855), saturated fatty acids (SFAs,24.8 %, 623), monounsaturated fatty acids (24 %, 604), and odd-chain fatty acids (17.2 %, 434).

Fig. 2.

Comparative analysis of lipid samples. (A) PCA scores; (B) PLS-DA score plot; (C) Model overview; (D) Permutation testing; (E) Venn map; (F) Heatmap.

The effect of antioxidants on accelerating the lipid secondary classification of oxidized fish oil is shown in Table 1. The glycerol ester molecules of fish oil without added antioxidants decreased with the prolongation of oxidation time. The DG content in the Con group decreased from 1601.714 ± 6.414 log10 area on day 0 of accelerated oxidation to 1581.706 ± 1.439 log10 area on day 20. The TG content in the Con group decreased from 4440.120 ± 5.952 log10 area on day 0 of accelerated oxidation to 4433.892 ± 5.825 log10 area on day 20. The total GL content in the Con group decreased from 6060.878 ± 11.247 log10 area on day 0 of accelerated oxidation to 6033.65 ± 7.382 log10 area on day 20. The antioxidant TBHQ significantly inhibited the decrease of DG, TG, and total GL in fish oil (p < 0.05), and these substances had the highest content on the 12th day of accelerated oxidation, at 1625.085 ± 5.038, 4473.078 ± 10.640, and 6116.138 ± 11.940 log10 area, respectively. At the same time, antioxidant PG can significantly inhibit the decrease of DG, TG, and total GL in fish oil. These substances have the highest content on the 20th day of accelerated oxidation, at 1601.519 ± 7.771, 4466.292 ± 6.889, and 6086.141 ± 8.408 log10 area, respectively. In addition, antioxidants did not have a significant effect on total GP (p > 0.05), but significantly affected the content of PE and phosphatidylethanolamine ethers (PEt) (p < 0.05). The PEt content in the Con group decreased from 57.063 ± 0.132 log10 area on day 0 of accelerated oxidation to 55.670 ± 0.178 log10 area on day 20. The PE content in the Con group was balanced from 1506.044 ± 2.055 log10 area on day 0 of accelerated oxidation to 1507.449 ± 2.744 log10 area on day 20. TBHQ could significantly increase the content of PE in fish oil (p < 0.05), reaching its highest value of 1530.222 ± 2.135 log10 area on the 12th day of accelerated oxidation. TBHQ could significantly increase the content of PEt in fish oil, reaching its highest level of 58.068 ± 0.133 log10 area on the 12th day of accelerated oxidation. PG could also significantly increase the content of PE, reaching its highest value of 1514.500 ± 1.769 log10 area on the 20th day of accelerated oxidation. Antioxidants TBHQ and PG had no significant effect on SP and ST (p > 0.05). The above results indicate that TBHQ and PG mainly affect the DG, TG, PE, and PEt molecules of fish oil that accelerate oxidation.

Table 1.

Changes in lipid contents during accelerated oxidation of silver carp fish oil treated with different antioxidants (Log10 area).

| Category | Class name | D_0 | CON_6 | CON_12 | CON_20 | TBHQ_6 | TBHQ_12 | TBHQ_20 | PG_6 | PG_12 | PG_20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GL | DG | 1601.714 ± 6.414b | 1590.030 ± 2.089cd | 1588.633 ± 6.756cd | 1581.706 ± 1.439e | 1600.914 ± 5.637b | 1625.085 ± 5.038a | 1591.660 ± 4.132bc | 1594.471 ± 2.084abc | 1599.470 ± 7.157ab | 1601.519 ± 7.771b |

| MG | 12.300 ± 0.099ab | 12.124 ± 0.075abc | 11.557 ± 0.034d | 11.963 ± 0.258c | 12.100 ± 0.076bc | 12.004 ± 0.246bc | 11.855 ± 0.133cd | 12.157 ± 0.322abc | 12.084 ± 0.297bc | 12.458 ± 0.064a | |

| TG | 4440.120 ± 5.952de | 4444.370 ± 2.247cde | 4443.368 ± 7.678cde | 4433.892 ± 5.825e | 4452.124 ± 8.605cd | 4473.078 ± 10.644a | 4449.809 ± 13.803cd | 4453.105 ± 4.351bcd | 4456.634 ± 8.085bc | 4466.292 ± 6.889ab | |

| WE | 6.744 ± 1.289de | 6.539 ± 1.527cde | 6.097 ± 0.145cde | 6.088 ± 0.211e | 5.664 ± 0.222cd | 5.971 ± 0.169a | 5.839 ± 0.247cd | 5.983 ± 0.404bcd | 6.791 ± 1.306bc | 5.872 ± 0.191ab | |

| Total GL | 6060.878 ± 11.247cd | 6053.064 ± 4.797d | 6049.655 ± 13.103de | 6033.650 ± 7.382e | 6070.802 ± 13.972bc | 6116.138 ± 11.941a | 6059.163 ± 17.659cd | 6065.716 ± 6.106cd | 6074.978 ± 7.462bc | 6086.141 ± 8.408b | |

| GP | PE | 1506.044 ± 2.055cd | 1505.820 ± 5.959cd | 1509.027 ± 6.143bc | 1507.399 ± 4.217c | 1501.449 ± 2.744de | 1530.222 ± 2.135a | 1504.466 ± 3.030cde | 1499.217 ± 1.103e | 1506.726 ± 3.621cd | 1514.500 ± 1.769b |

| PEt | 57.063 ± 0.132b | 56.063 ± 0.076d | 55.670 ± 0.178e | 54.857 ± 0.060f | 57.030 ± 0.143b | 58.068 ± 0.133a | 56.398 ± 0.137c | 56.457 ± 0.062c | 56.438 ± 0.044c | 56.290 ± 0.068c | |

| PG | 290.287 ± 0.254e | 304.799 ± 4.661bc | 307.502 ± 2.873ab | 310.177 ± 5.216a | 289.441 ± 3.420e | 300.077 ± 1.288cd | 300.777 ± 1.135cd | 296.742 ± 2.778d | 308.725 ± 4.254ab | 304.150 ± 3.607bc | |

| PI | 69.954 ± 2.039d | 77.228 ± 2.042bc | 78.684 ± 3.576ab | 81.575 ± 1.778a | 70.446 ± 2.442d | 75.636 ± 2.580bc | 76.353 ± 2.372bc | 74.699 ± 0.980c | 76.979 ± 2.163bc | 81.444 ± 2.510a | |

| PIP2 | 13.940 ± 0.309ab | 13.906 ± 0.482ab | 14.245 ± 0.564ab | 14.470 ± 0.130a | 14.072 ± 0.174ab | 14.170 ± 0.239ab | 13.709 ± 0.522ab | 13.722 ± 0.549ab | 13.413 ± 0.274b | 14.162 ± 0.287ab | |

| PMe | 17.371 ± 0.052b | 17.096 ± 0.049de | 16.958 ± 0.061f | 16.646 ± 0.039g | 17.384 ± 0.030b | 17.548 ± 0.013a | 17.160 ± 0.054cd | 17.195 ± 0.036c | 17.134 ± 0.045cde | 17.077 ± 0.029e | |

| PS | 126.554 ± 1.690fg | 133.231 ± 0.819cd | 136.016 ± 2.093abc | 138.519 ± 1.249a | 124.849 ± 3.834g | 134.283 ± 2.576bcd | 131.421 ± 1.587de | 129.356 ± 0.714ef | 135.646 ± 0.236abc | 137.006 ± 0.894ab | |

| Total GP | 2081.213 ± 4.132fg | 2108.142 ± 8.621d | 2118.103 ± 4.812bc | 2123.644 ± 3.941ab | 2074.671 ± 3.034g | 2130.005 ± 4.777a | 2100.283 ± 1.427e | 2087.389 ± 4.119f | 2115.062 ± 3.775c | 2124.63 ± 2.111ab | |

| SP | Cer | 7.651 ± 0.034a | 7.660 ± 0.106a | 7.764 ± 0.031a | 7.682 ± 0.092a | 7.572 ± 0.194a | 7.603 ± 0.229a | 7.748 ± 0.045a | 7.752 ± 0.051a | 7.528 ± 0.274a | 7.709 ± 0.053a |

| SPHP | 5.898 ± 0.368a | 6.608 ± 1.331a | 6.172 ± 0.314a | 6.714 ± 1.270a | 6.385 ± 0.250a | 6.739 ± 1.008a | 6.969 ± 0.971a | 6.243 ± 0.163a | 6.720 ± 1.085a | 5.901 ± 0.631a | |

| SPH | 15.507 ± 0.026ef | 15.686 ± 0.055c | 15.792 ± 0.045b | 16.054 ± 0.051a | 15.551 ± 0.050ef | 15.479 ± 0.048g | 15.700 ± 0.082c | 15.582 ± 0.014de | 15.677 ± 0.076c | 15.637 ± 0.046cd | |

| Total SP | 36.833 ± 0.399a | 37.760 ± 1.069a | 37.635 ± 0.424a | 38.344 ± 1.491a | 37.341 ± 0.303a | 37.542 ± 1.293a | 38.206 ± 0.636a | 37.462 ± 0.252a | 37.763 ± 1.167a | 37.040 ± 0.723a | |

| ST | AcHexStE | 15.629 ± 1.374ab | 16.838 ± 0.194a | 16.402 ± 1.126a | 13.680 ± 1.110b | 15.205 ± 1.619ab | 17.296 ± 0.224ab | 15.809 ± 1.591ab | 16.019 ± 1.301ab | 16.337 ± 1.062a | 15.867 ± 1.277ab |

| SiE | 22.096 ± 0.053bcd | 21.980 ± 0.009e | 22.028 ± 0.119de | 22.014 ± 0.013de | 22.116 ± 0.031bc | 22.230 ± 0.035a | 22.034 ± 0.021cde | 22.084 ± 0.066bcd | 22.075 ± 0.020bcd | 22.156 ± 0.019ab | |

| Total ST | 37.725 ± 1.407ab | 38.818 ± 0.200a | 38.429 ± 1.216a | 35.694 ± 1.123b | 37.320 ± 1.639ab | 39.526 ± 0.189a | 37.843 ± 1.587ab | 38.103 ± 1.320ab | 38.413 ± 1.082a | 38.023 ± 1.288ab | |

Notes: GL, glycerolipids; DG, diglyceride; MG, monoglyceride; TG, triglyceride; WE, wax esters; GP, glycerophospholipids; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PEt, phosphatidylethanol; PG, phosphatidylglycerol; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol; PMe, phosphatidylmethanol, PS, phosphatidylserine; SP, sphingolipids; Cer, ceramides; SPHP, sphingosine phosphate; SPH, sphingosine; ST, sterol lipids; AcHexStE, acylGlcStigmasterol ester; SiE, sitosterol ester.

Different superscript letters (a, b, c, d, e, f, g) denote significant differences at p < 0.05.

Multivariate analysis of lipid variation was carried out in antioxidant-inhibited oven-accelerated oxidized silver carp visceral oil. The lipid differential characteristics of antioxidant-inhibited oven-accelerated oxidized silver carp visceral oil were analyzed using principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA). In the PCA score plot, the variance contribution rates of principal component 1 (PC1) and principal component 2 (PC2) were 26.40 % and 8.15 %, respectively, with a cumulative explanation rate of 34.55 %. PC1 and PC2, as linear combinations of original variables (i.e., expression levels of specific lipid molecules), were quantified by loading values to evaluate the contribution of individual lipids to each principal component (Fig. 2C). In the PLS-DA model, component 1 (R2Y = 0.0994, Q2 = 0.0648) and component 2 (R2Y = 0.199, Q2 = 0.0446) explained 16.2 % and 7.5 % of the variable information, respectively (Fig. 2D and E). Experimental data demonstrated that lipid samples from antioxidant-inhibited oven-accelerated oxidized silver carp visceral oil exhibited significant separation trends (p < 0.05) in both PCA and PLS-DA score plots. The permutation test results revealed that the regression lines (dashed lines) of R2 (blue dots) and Q2 (red triangles) met the criteria for model validity. At a permutation retention (horizontal coordinate) of 1.0, the Q2 regression line intersected the Y-axis at −0.0785 (R2 = 0.1494) (Fig. 2F). Although the Q2 value fell below conventional thresholds due to limited sample size, the downward trend of the regression line with decreasing permutation retention indicated no over fitting in the model.

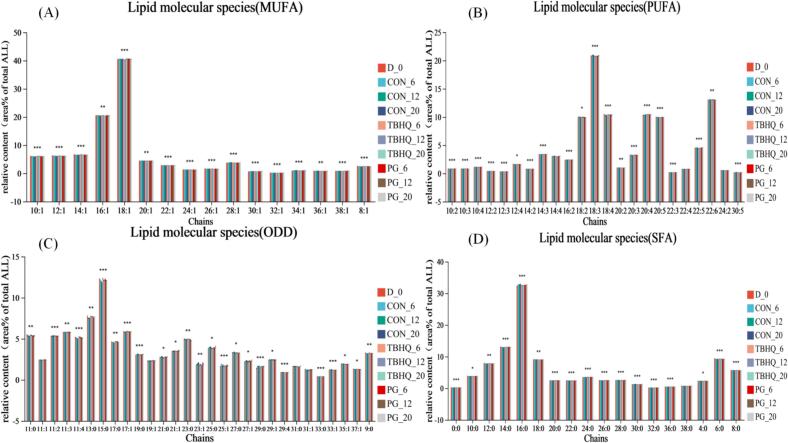

The classification and statistics of unsaturated species with different lipid chains are shown in Fig. 3. The antioxidant treatment significantly inhibited lipid oxidation in fish oil samples, with markedly distinct fatty acid profiles observed. Specifically, the analysis detected 16 monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), 23 PUFAs, 29 odd-chain fatty acids (OCFAs), and 17 SFAs showing statistically significant variations (p < 0.05) between treated and Con groups. The fatty acid composition was categorized as follows: Monounsaturated fatty acids (SFAs) included C8:1, C10:1, C12:1, C14:1, C16:1, C20:1, C22:1, C24:1, C26:1, C24:1, C26:1, C28:1, C30:1, C32:1, C34:1, C36:1, C38:1; PUFAs comprised C10:2, C10:3, C10:4, C12:2, C12:3, C12:4, C14:2, C14:3, C14:4, C16:2, C18:2, C18:3, C18:4, C20:2, C20:3, C20:3, C20:4, C20:5, C22:3, C22:4, C22:5, C22:6, C24:2, C30:5; odd-chain fatty acids (OCFAs) contained C11:0, C11:1, C11:2, C11:3, C11:4, C13:0, C15:0, C17:0, C19:0, C19:1, C21:1, C23:0, C23:1, C25:0. C25:1, C27:0. C27:1, C29:0, C29:4, C31:0, C33:0, C33:1, C35:1, C37:1, C9:0; and SFAs included C4:0, C6:0, C8:0, C10:0, C12:0, C14:0, C16:0, C18:0, C20:0, C22:0, C24:0, C26:0, C28:0, C30:0, C32:0, C36:0, C38:0.

Fig. 3.

Classification and statistics of lipid chain unsaturation species. (A) Monounsaturated fatty acids; (B) Polyunsaturated fatty acids; (C) Odd-numbered fatty acids; (D) Saturated fatty acids.

The statistical chart of the difference in the number of volcano plots of lipids accelerated by the addition of antioxidants is shown in Fig. 4 (A). The experimental results demonstrated that during the accelerated oxidation process of fish oil, the down-regulated lipid levels progressively increased, indicating the occurrence of oxidative degradation in lipid molecules. Upon the addition of antioxidants to the oxidized fish oil, both TBHQ and PG significantly suppressed lipid down-regulation, with TBHQ exhibiting superior inhibitory efficacy compared to PG. These findings align consistently with the phenomena observed in Fig. 1 of the present study. At the secondary lipid classification level, the differential lipids were primarily TG, PE, DG, CL, ChE, MG, MGDG, MLCL, PEt, PG, PI, PIP2, PMe, PS, SPH, and AcHexStE (Fig. 4B). Whereas at the tertiary classification level, the lipid species exhibiting significant differences were mainly PE (8:1e/15:0), PEt (18:0/15:0), PG (25:1/18:2), TG (12:1e/6:0/18:3), TG (12:1e/6:0/16:0), PE (34:1/14:4), TG (20:3e/10:1/10:3), TG (14:0/12:4/20:4), PE (20:1/11:3) and DG (18:1/22:6) (Fig. 4C). The above results indicate that antioxidants significantly inhibit the oxidative degradation of TG, DG, and PE containing unsaturated fatty acids (UFAs).

Fig. 4.

Differential lipid analysis. (A) Statistical chart of differences in lipid volcanic chart quantity; (B) Different lipid molecular species; (C) One-way anova test bar plot.

3.3. Changes in flavoromics of antioxidant-treated fish oil in an oven

As shown in Table 2, HS-SPME-GC–MS analysis detected 54 volatile compounds in fish oil subjected to accelerated oxidation at 60 °C, including 2 alcohols, 30 aldehydes/ketones, 10 hydrocarbons, 8 aromatic compounds, 6 nitrogen-containing compounds, and 4 heterocyclic compounds. Aldehydes, alcohols, ketones, and hydrocarbons constituted the predominant volatile components. Notably, the contribution of individual compounds to aroma characteristics depends not only on their concentrations but also on their odor thresholds in the matrix. Compounds with OAVs ≥1 were identified as key flavor contributors: Nonanal, (E, E)-2,4-heptadienal, (E)-2-nonenal, (E)-2-decenal, 1-octen-3-ol, and eugenol.

Table 2.

Changes in volatile compounds during accelerated oxidation of silver carp fish oil treated with different antioxidants (μg/kg).

| CAS | Name | RI | Threshold (μg/kg) | Blank |

Con |

PG |

TP |

TBHQ |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D_0 | D_6 | D_12 | D_20 | D_6 | D_12 | D_20 | D_6 | D_12 | D_20 | D_6 | D_12 | D_20 | ||||

| Aldehyde | ||||||||||||||||

| 122-00-9 | P-methyl acetophenone | 1900 | 15.6 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.35 ± 0.02b | 0.42 ± 0.01a | ND | ND |

| 3045-98-5 | 2-Methylene-cyclohexane-1-ketone | 1400 | / | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 4.62 ± 0.49a | ND | ND |

| 124-19-6 | N-nonyl aldehyde | 1400 | 1 | 5.15 ± 0.37ab | ND | ND | ND | 4.45 ± 1.28abc | 1.42 ± 0.33d | ND | 3.23 ± 0.39c | 5.38 ± 2.26ab | ND | 5.68 ± 1.50a | 3.91 ± 0.96bc | ND |

| 4313-03-5 | (E,E)-2,4-heptadienal | 1500 | 10 | 49.20 ± 5.63a | 19.43 ± 1.86b | 15.51 ± 1.70bcd | 46.61 ± 4.18a | 15.38 ± 0.72bcd | 11.82 ± 0.53de | 9.40 ± 0.81e | 18.39 ± 1.62bc | 16.98 ± 4.08bc | 11.95 ± 1.43de | 14.30 ± 0.19cd | 4.39 ± 0.98f | 3.06 ± 0.43f |

| 100-52-7 | Benzaldehyde | 1500 | 350 | 29.46 ± 6.37a | 6.80 ± 1.61bc | 3.37 ± 0.32cdef | 6.04 ± 1.24bcde | 6.51 ± 1.50bcd | 3.03 ± 0.46def | 2.55 ± 0.14ef | 4.97 ± 0.90cdef | 4.50 ± 1.01cdef | 2.77 ± 0.56def | 9.22 ± 0.92b | 2.65 ± 0.37ef | 1.47 ± 0.17f |

| 1077-16-3 | Phenylhexanal | 1501 | / | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.49 ± 0.08a | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 18829-56-6 | (E)-2-nonylaldehyde | 1501 | 0.1 | 2.58 ± 0.46c | 1.41 ± 0.33de | 0.44 ± 0.37ef | 1.36 ± 0.54de | 4.39 ± 0.51b | 1.09 ± 0.19ef | 0.12 ± 0.02f | 3.85 ± 1.09b | 0.39 ± 0.07ef | ND | 7.28 ± 2.01a | 2.28 ± 0.62cd | ND |

| 20697-55-6 | 4-oxo-(E)-2-hexenal | 1501 | / | 3.11 ± 0.23a | 1.18 ± 0.05bc | 0.70 ± 0.58de | ND | 1.00 ± 0.29cd | 0.44 ± 0.42ef | 1.03 ± 0.01cd | 0.74 ± 0.08de | ND | 1.46 ± 0.28b | ND | ND | ND |

| 96-48-0 | γ-butyrolactone | 1600 | 64 | 1.47 ± 0.02b | 1.64 ± 0.06b | 4.81 ± 4.42a | 0.17 ± 0.30b | ND | 1.15 ± 0.11b | ND | ND | ND | 0.61 ± 0.17b | NDc | 0.68 ± 0.27b | ND |

| 98-86-2 | Acetophenone | 1301 | 3000 | 1.35 ± 0.16a | 1.24 ± 0.08a | 0.57 ± 0.16bc | ND | 0.80 ± 0.10b | ND | 0.25 ± 0.22de | 0.55 ± 0.48bc | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.35 ± 0.04cd |

| 34246-54-3 | 3-Ethylbenzaldehyde | 1700 | / | 2.54 ± 1.02a | 1.18 ± 0.60bc | 1.64 ± 0.36b | 1.47 ± 0.30b | 0.95 ± 0.32bc | 1.37 ± 0.10bc | 0.68 ± 0.11cd | 0.99 ± 0.20bc | 1.11 ± 0.14bc | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 5973-71-7 | 3,4-Dimethylbenzaldehyde | 1800 | / | ND | ND | ND | 4.61 ± 1.86b | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 7.70 ± 5.37a | 2.37 ± 0.16bc | ND |

| 14237-73-1 | 3,7,11,15-Tetramethylhexadecan-2-ene-1-acetic ester | 1900 | / | 4.95 ± 4.95a | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.24 ± 1.19b | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 610-99-1 | 2’-Hydroxyphenylacetone | 1901 | / | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.37 ± 0.00a | ND | ND |

| 626-19-7 | Isophthalaldehyde | 2100 | / | 11.86 ± 1.27b | 14.05 ± 1.53a | 3.81 ± 3.18c | 3.77 ± 0.33c | ND | 1.04 ± 0.37d | 0.96 ± 0.07d | ND | 0.57 ± 0.17d | 1.20 ± 0.20d | ND | ND | 0.53 ± 0.10d |

| 97-53-0 | Eugenol | 2101 | 7 | 8.37 ± 6.95c | ND | ND | ND | 13.72 ± 0.40bc | 7.40 ± 0.63c | 1.57 ± 0.21d | 13.33 ± 5.30ab | 10.78 ± 2.53bc | 1.34 ± 0.13d | 17.49 ± 1.66a | 6.66 ± 0.39c | 2.05 ± 0.04d |

| 629-80-1 | Palmitaldehyde | 2200 | / | 2.96 ± 2.96a | ND | ND | ND | 1.97 ± 1.29a | 1.69 ± 1.46ab | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 937-30-4 | P-ethyl acetophenone | 2200 | / | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.68 ± 0.30a | ND | 0.62 ± 0.11a | 0.75 ± 0.43a | 0.59 ± 0.06a | ND | ND | 0.28 ± 0.22b | ND |

| 3913-81-3 | (E)-2-Decenal | 1601 | 0.4 | 3.63 ± 0.31de | 6.13 ± 1.97c | 1.59 ± 0.32f | 1.23 ± 0.04f | 9.19 ± 0.86b | 2.32 ± 0.25ef | 0.55 ± 0.37f | 9.25 ± 1.54b | 8.99 ± 1.19b | 0.49 ± 0.20f | 12.30 ± 1.60a | 4.18 ± 1.02d | 0.48 ± 0.37f |

| 108-94-1 | Cyclohexanone | 1050 | 2,000,000 | ND | ND | ND | 6.28 ± 0.09a | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Alkanes | ||||||||||||||||

| 629-59-4 | n-Tetradecane | 1401 | 3500 | 178.04 ± 116.02a | 62.27 ± 1.09b | 53.02 ± 16.64b | 8.35 ± 2.69b | 15.48 ± 3.93b | 16.69 ± 4.22b | 9.75 ± 1.47b | 8.91 ± 1.55b | 8.43 ± 0.51b | 29.03 ± 7.06b | 7.90 ± 0.27b | 11.69 ± 3.02b | 5.97 ± 1.31b |

| 629-62-9 | Pentadecane | 1501 | 250,000 | 45.47 ± 14.90b | 43.52 ± 3.54bc | 14.55 ± 4.76fg | 18.16 ± 2.99f | 34.93 ± 1.85cd | 22.34 ± 1.50ef | 5.02 ± 1.15gh | 59.90 ± 10.05a | 31.70 ± 3.31de | 3.48 ± 1.05h | 45.55 ± 2.97b | 23.35 ± 1.25ef | 6.68 ± 0.90gh |

| 544-76-3 | n-Cetane | 1601 | / | 44.29 ± 25.46a | 32.41 ± 4.59abc | 14.03 ± 4.37def | 15.59 ± 4.29def | 22.96 ± 1.51cd | 17.46 ± 2.61cdef | 3.25 ± 0.94ef | 23.83 ± 15.15bcd | 24.21 ± 1.92bcd | 1.93 ± 0.80f | 39.33 ± 5.16ab | 18.90 ± 2.42cde | 5.06 ± 0.59ef |

| 629-78-7 | n-Heptadecane | 1701 | / | 755.99 ± 14.68b | 709.20 ± 51.42b | 469.09 ± 220.19c | 440.25 ± 32.36c | 793.94 ± 28.66b | 779.43 ± 9.48b | 129.31 ± 45.45e | 706.41 ± 63.15b | ND | 86.90 ± 5.99e | 1183.52 ± 171.50a | 852.62 ± 68.95b | 215.74 ± 13.19d |

| 2579-04-6 | 8-Heptadecene | 1800 | / | 145.68 ± 84.11a | 123.99 ± 33.11a | 78.68 ± 21.31b | 70.11 ± 6.37b | 4.00 ± 0.28c | 2.10 ± 0.37c | ND | 2.80 ± 0.37c | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 330207-53-9 | (E)-14-Hexadecene | 1800 | / | 64.15 ± 37.46ab | 56.19 ± 21.65abc | 28.95 ± 4.08cde | 27.1 ± 10.33cde | 42.21 ± 4.42bc | 31.41 ± 8.1cd | 4.87 ± 1.92de | 45.11 ± 28.07bc | 40.75 ± 5.21bc | ND | 79.48 ± 20.19a | 41.87 ± 6.68bc | 6.08 ± 0.85de |

| 593-45-3 | n-Octadecane | 1900 | / | 58.21 ± 45.96a | 30.6 ± 22.80abc | 12.11 ± 9.92bc | 12.49 ± 9.04bc | 15.75 ± 3.29bc | 17.78 ± 8.88bc | ND | 23.48 ± 16.64bc | 13.68 ± 1.40bc | ND | 0 ± 0d | 32.21 ± 8.67ab | 2.39 ± 0.41bc |

| 629-92-5 | Nonadecane | 2000 | / | 21.15 ± 18.26ab | 8.78 ± 10.71abc | 3.88 ± 3.76c | ND | 5.79 ± 1.76c | 5.23 ± 3.72c | ND | 6.88 ± 5.15bc | 1.96 ± 0.12c | ND | 22.26 ± 17.90a | 6.57 ± 5.43bc | ND |

| 18435-45-5 | 1-Nonadecene | 2001 | / | 33.24 ± 29.61a | 16.77 ± 18.86abc | 6.46 ± 6.90bc | ND | 10.52 ± 3.89bc | 8.94 ± 7.74bc | ND | 6.97 ± 8.35bc | 4.35 ± 0.44bc | ND | 9.49 ± 8.10bc | 22.58 ± 7.20ab | ND |

| 629-94-7 | Eicosane | 2200 | / | 3.96 ± 1.07a | 2.01 ± 1.27b | 1.61 ± 0.41bc | 1.00 ± 0.08c | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.17 ± 0.66bc | ND |

| Alcohols | ||||||||||||||||

| 102608-53-7 | Phytol | / | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.36 ± 0.60b | ND | 17.30 ± 14.59a | 7.10 ± 0.76b | ND | |

| 3391-86-4 | 1-Octene-3-ol | 980 | 1 | 1.70 ± 0.19c | 2.85 ± 0.72c | 5.72 ± 0.48b | 13.77 ± 2.34a | 1.73 ± 0.14c | 2.16 ± 0.24c | 5.40 ± 0.33b | 2.09 ± 0.42c | 5.57 ± 0.86b | 12.85 ± 1.04a | 1.32 ± 0.10c | 1.38 ± 0.01c | 2.61 ± 0.14c |

| Acids | ||||||||||||||||

| 506-32-1 | Arachidonic acid | 2300 | 1,830,000 | 47.08 ± 41.53a | 27.60 ± 39.94ab | 9.77 ± 11.69b | 4.93 ± 8.54b | ND | 16.89 ± 13.47ab | ND | 23.93 ± 18.45ab | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 108698-02-8 | Methyl percis 7,10,13,16, 19-docosapentaenoate | 2301 | / | 28.37 ± 25.11b | ND | ND | ND | ND | 12.72 ± 11.13b | ND | 21.11 ± 16.88b | ND | ND | 80.58 ± 70.58a | 31.94 ± 4.19b | 0 ± 0b |

| 93-99-2 | Phenyl benzoate | 2350 | / | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.57 ± 0.27a | 0 ± 0b | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Heterocyclic class | ||||||||||||||||

| 70424-13-4 | Cis-2-(2-pentenyl) furan | 1300 | 1000 | 1.65 ± 0.08d | 2.73 ± 0.48c | 3.69 ± 0.34b | 8.05 ± 0.30a | ND | 1.48 ± 0.36de | 0.88 ± 0.52fg | ND | ND | 1.04 ± 0.64ef | ND | 0.97 ± 0.20efg | 0.41 ± 0.34h |

| 78508-96-0 | (S)-5-HydroxymetHyl-2(5H)-furanone | 1400 | / | 1.24 ± 0.04a | ND | ND | 0.78 ± 0.21b | ND | ND | 0.36 ± 0.05c | ND | ND | 0 ± 0e | ND | ND | 0.25 ± 0.07d |

| 4265-25-2 | 2-Methylbenzofuran | 1801 | / | 1.67 ± 0.74a | 0.9 ± 0.29b | 0.65 ± 0.09bc | 0.54 ± 0.03bc | 0.62 ± 0.10bc | ND | ND | 0.57 ± 0.01bc | ND | 0.36 ± 0.06cd | ND | ND | 0.30 ± 0.09cd |

| 6305-52-8 | 2-Butyldecahydronaphthalene | 2100 | 200 | ND | ND | ND | 4.12 ± 1.14a | ND | ND | ND | 0.31 ± 0.27b | ND | ND | 0.53 ± 0.02b | ND | ND |

| Nitrogenous compounds | ||||||||||||||||

| 16232-28-3 | 2-Methyl-5-(1-butylene-1-yl) pyridine | 1700 | / | ND | ND | ND | ND | 12.66 ± 6.31b | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 21.39 ± 0.49a | 0.74 ± 0.20c | 0.64 ± 0.11c |

| 100-61-8 | N-methylaniline | 1700 | / | ND | ND | ND | ND | 59.08 ± 16.13b | ND | ND | 14.02 ± 2.36c | ND | ND | 84.19 ± 3.49a | 0 ± 0c | ND |

| 62-53-3 | Aniline | 1701 | 4,660,000 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.42 ± 0.37b | ND | ND | 0.30 ± 0.15c | ND | ND | 2.09 ± 0.12a | 0 ± 0c | ND |

| 140-29-4 | Phenylacetonitrile | 1900 | 1000 | 4.33 ± 0.89a | 1.29 ± 0.07b | 1.07 ± 0.19b | ND | 1.44 ± 0.25b | ND | ND | 1.04 ± 0.04b | ND | ND | 1.46 ± 0.11b | 0.37 ± 0.02c | ND |

| 1971-46-6 | 1H-1,2, 3-triazole | 2201 | / | ND | ND | ND | ND | 6.01 ± 1.96a | ND | ND | 2.32 ± 0.91b | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 100813-60-3 | 1H isoindole, 3-methoxy-4, 7-dimethyl | 2001 | / | ND | ND | ND | ND | 60.44 ± 1.61a | ND | ND | 13.34 ± 3.95b | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Aromatic compounds | ||||||||||||||||

| 98-82-8 | Isopropyl benzene | 1301 | 400 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.65 ± 0.16fg | 0.51 ± 0.09g | 3.32 ± 0.19b | 0.92 ± 0.18ef | 2.08 ± 0.30d | 3.66 ± 0.29a | ND | 1.16 ± 0.11e | 2.79 ± 0.42c |

| 934-74-7 | 5-Ethyl-m-xylene | 1301 | / | 1.90 ± 0.96a | 0.82 ± 0.15b | 0.49 ± 0.08bc | ND | ND | ND | 0.34 ± 0.06bc | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 95-93-2 | 1,2,4,5-Tetratoluene | 1401 | 87 | 37.05 ± 2.07a | 8.98 ± 1.01b | 5.64 ± 1.33c | ND | 9.93 ± 1.04b | 2.39 ± 3.05d | ND | 8.95 ± 0.91b | ND | ND | 11.13 ± 0.78b | ND | ND |

| 27831-13-6 | 4-Vinyl-1,2-xylene | 1500 | / | 0.92 ± 0.92c | ND | ND | ND | 1.84 ± 0.60a | 1.22 ± 0.53ab | ND | 1.55 ± 0.83ab | 1.62 ± 0.73ab | ND | 1.50 ± 0.31ab | 1.02 ± 0.51ab | ND |

| 826-18-6 | 1-Pentene benzene | 1600 | / | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.63 ± 0.05b | 1.32 ± 0.30a | ND | ND | ND |

| 16002-93-0 | (E)-1-Phenyl-1-pentene | 1600 | / | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.64 ± 0.13b | 0.81 ± 0.09a | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 829-99-2 | 1-Heptenyl benzene | 1801 | / | 1.63 ± 0.03b | 2.32 ± 0.72a | ND | 0 ± 0d | 1.72 ± 0.37b | 1.17 ± 0.22c | 0 ± 0d | 1.33 ± 0.22bc | 1.27 ± 0.22bc | ND | ND | 0.95 ± 0.08c | ND |

| 108-95-2 | Phenol | 1901 | 5900 | ND | ND | ND | 0 ± 0e | 0.68 ± 0.13a | 0.52 ± 0.09b | 0.25 ± 0.02d | 0.45 ± 0.06bc | 0.5 ± 0.06b | 0.37 ± 0.06c | 0.55 ± 0.02b | 0 ± 0e | ND |

| OAV ≥ 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 124-19-6 | N-nonyl aldehyde | 1400 | 1 | 5.15 | ND | ND | ND | 4.45 | 1.42 | ND | 3.23 | 5.38 | 0.00 | 5.68 | 3.91 | ND |

| 4313-03-5 | (E,E)-2,4-Heptadienal | 10 | 4.92 | 1.94 | 1.55 | 4.66 | 1.54 | 1.18 | 0.94 | 1.84 | 1.70 | 1.20 | 1.43 | 0.44 | 0.31 | |

| 18829-56-6 | (E)-2-Nonylaldehyde | 1501 | 0.1 | 25.82 | 14.14 | 4.43 | 13.58 | 43.94 | 10.88 | 1.18 | 38.54 | 3.87 | ND | 72.83 | 22.78 | ND |

| 3913-81-3 | (E)-2-Decenal | 1601 | 0.4 | 9.07 | 15.33 | 3.97 | 3.06 | 22.97 | 5.79 | 1.37 | 23.13 | 22.49 | 1.23 | 30.75 | 10.44 | 1.21 |

| 3391-86-4 | 1-Octene-3-ol | 980 | 1 | 1.70 | 2.85 | 5.72 | 13.77 | 1.73 | 2.16 | 5.40 | 2.09 | 5.57 | 12.85 | 1.32 | 1.38 | 2.61 |

| 97-53-0 | Eugenol | 2101 | 7 | 1.20 | ND | ND | ND | 1.96 | 1.06 | 0.22 | 1.90 | 1.54 | 0.19 | 2.50 | 0.95 | 0.29 |

Note: ND: Not detected. Different superscript letters (a, b, c, d) within the same row indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

During the 20-day accelerated oxidation, the OAV of (E)-2-decenal in the Con group declined from 9.07 to 3.06, while TBHQ, PG, and TP treated groups exhibited lower values (1.21, 1.23, and 1.37, respectively). Nonanal in the Con group decreased from an initial OAV of 5.15 to 0 by day 6, whereas antioxidant-treated groups stabilized at 3.23. 1-Octen-3-ol in the Con group surged from 1.70 (day 0) to 13.77 (day 20), but antioxidants significantly suppressed this increase (TBHQ: 2.61; PG: 5.40; TP: 12.89). In addition, (E)-2-decenal OAV dropped from 4.46 (day 0) to 0.00 (day 12), while 1-octen-3-ol OAV rose from 2.95 to 6.11 (day 20; p < 0.05). Nonanal, (E, E)-2,4-heptadienal, and (E)-2-nonenal OAVs exhibited a decline-rise trend during oxidation. Eugenol OAV stabilized after day 9 (1.51 to 0.73–0.89; p > 0.05).

The OPLS-DA model constructed from GC–MS data demonstrated robust performance (R2X = 0.956, R2Y = 0.926, Q2 = 0.802), indicating high explanatory and predictive capacity (Fig. 4B). Sample distribution revealed: Fresh fish oil (Blank) was distinct from oxidized Con, PG, and TBHQ groups. The Con group clustered in the first quadrant at day 6 but shifted to the second quadrant by day 12 to day 20, likely due to volatile degradation or transformation post-oxidation. Antioxidant-treated groups (TP, TBHQ, and PG) clustered separately from Con after day 12, highlighting altered flavor profiles.

A permutation test (200 iterations) validated the model (R2 = 0.365, Q2 = −0.771), with Q2 intercepting the negative y-axis, confirming no overfitting and enabling reliable discrimination of antioxidant-treated samples. VIP analysis identified 19 key volatile compounds (VIP > 1.0; Fig. 4C) contributing to sample classification. The ranking by contribution was: (E)-1-phenyl-1-pentene > γ-butyrolactone > 4-ethylacetophenone > 1-pentenylbenzene > n-heptadecane > phenol > isophthalaldehyde > 4-methylacetophenone > nonanal > 1-heptenylbenzene > 3-ethylbenzaldehyde > 4-oxo-(E)-2-hexenal > (S)-(−)-5-hydroxymethyl-2(5H)-furanone > benzeneacetaldehyde > 1-octen-3-ol > cumene > pentadecane > hexadecanal > benzyl benzoate.

3.4. Correlation analysis between key lipids and volatile flavor compounds

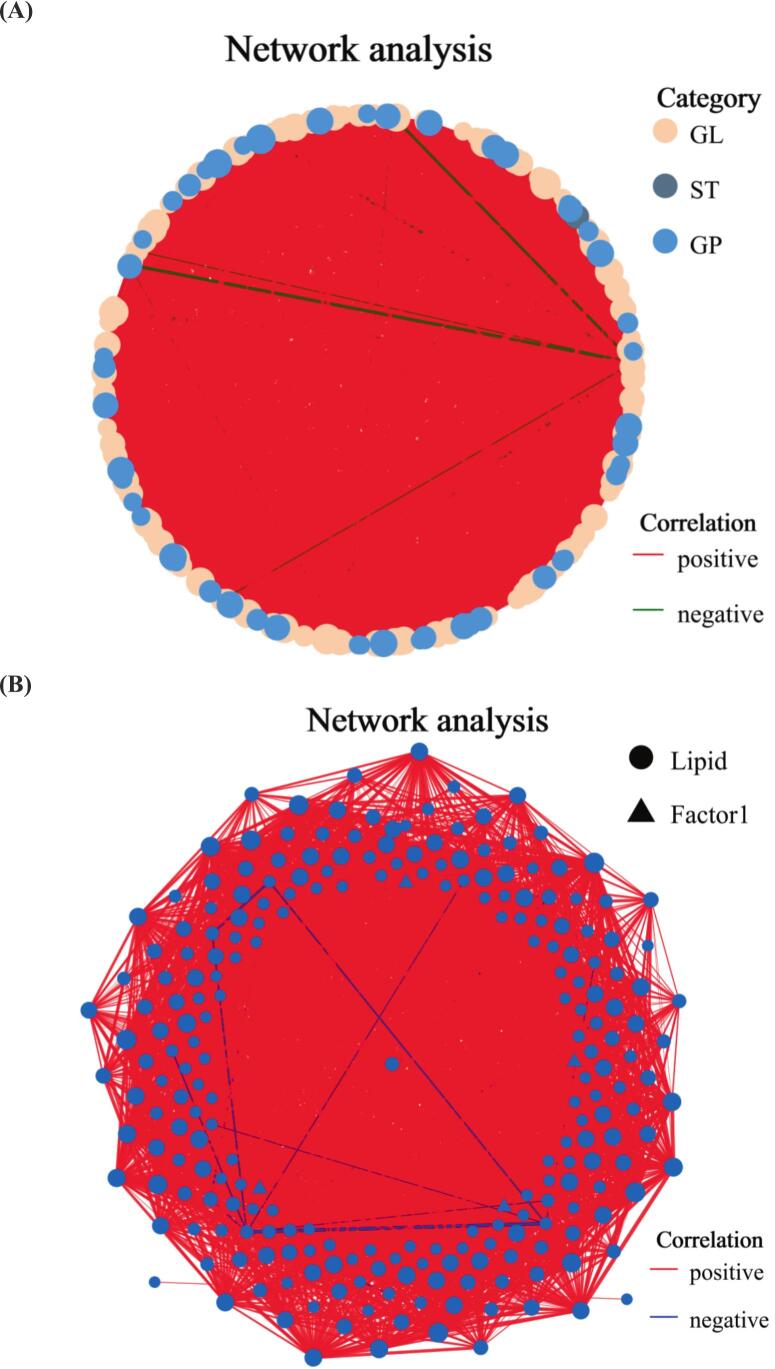

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to clarify the interrelationships between critical aroma compounds (OAV ≥ 1) and differential lipids (VIP > 1.0, p < 0.05). The single-factor correlation network diagram mainly reflects the correlation of various metabolite classification levels. The size of nodes in the graph represents their degree, and different colors indicate different classifications. The color of the line represents positive and negative correlation, red represents positive correlation, and blue represents negative correlation. The thickness of the line indicates the magnitude of the correlation coefficient, and the thicker the line, the higher the correlation between species. The more lines there are, the closer the connection between the nodes. Fig. 5(A) shows positive correlations between most of the GL, ST, and GP nodes among the different lipids. As shown in Fig. 5(A), there were positive correlations between most of the GL, ST, and GP nodes in differential lipids. Among differential lipids, nodes corresponding to GL, ST, and GP predominantly exhibited positive intercorrelations. The differential lipid profile was dominated by GL and GP subclasses. Statistical analysis revealed 2179 significant edges (Pearson correlation coefficient > 0.9) between Node 1 and Node 2. Node 1 comprised 755 TG, 891 DG, 369 PE, and 113 PEt. Node 2 contained 1140 TG, 498 DG, 308 PE, and 104 PEt molecular species.

Fig. 5.

Correlation network diagram. (A) Single factor correlation network diagram; (B) Multi factor correlation network diagram.

The multivariate correlation network diagram primarily illustrates the correlations among metabolite taxonomic levels under specific environmental conditions, or the associations between metabolite taxonomic levels and species within a given environmental context. In this visualization, node size corresponds to degree centrality, reflecting connectivity importance. Distinct color schemes represent different taxonomic species. Edge coloration denotes correlation polarity (red: positive, blue: negative). Edge thickness scales with correlation coefficient magnitude, where thicker lines indicate stronger associations. Network density (line quantity) reflects nodal interconnectivity, with increased line numbers signifying more robust node relationships. This representation adheres to graph-theoretical conventions for ecological network analysis, employing adjacency matrices to quantify interaction strengths while maintaining visual clarity through standardized encoding of topological parameters. The multi-factor correlation analysis (R2 ≥ 0.8, p < 0.05) between differential lipids and key volatile flavor compounds is shown in Fig. 5(B). Eugenol exhibited significant positive correlations with 74 differential lipid molecules, including 26 TG, 10 PE, 33 DG, 1 monoglyceride (MG), 1 phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and 1 cholesteryl ester (ChE). 1-Octen-3-ol exhibited significant negative correlations (p < 0.05) with 10 DG (18:3/20:3, 16:0/22:6, 16:1/14:0, 17:1/22:6, 18:0/22:6, 18:1/18:2, 18:1/20:2, 18:3/20:5, 18:4/16:0, 18:4/16:1), 5 TG (12:1e/6:0/20:5, 16:1e/6:0/10:4, 18:0e/18:1/20:1, 18:1/10:1/10:1, 18:4/14:4/18:4), 4 PE (12:0e/11:3, 24:1/22:6, 8:0e/11:2, 8:1e/10:0), and 1 PEt (15:0/16:1). Nonanal exhibited a significant positive correlation with TG (16:1e/6:0/10:4) and DG (16:0/22:6) (p < 0.05), while (E)-2-decenal showed a significant positive correlation with PE (14:0e/18:1) (p < 0.05). The above findings demonstrate that PE, TG, and DG act as critical precursors in the antioxidant-mediated suppression of volatile flavor deterioration in fish oil.

4. Discussions

This study pioneers a combined lipidomics and flavoromics approach to holistically decipher the protective role of antioxidants against oxidative degradation and flavor deterioration in silver carp viscera-derived fish oil.

4.1. Analysis of antioxidants inhibiting the oxidation pathways of fish oil

The oxidation of fat is the main spoilage process of fish oil, mainly producing odorless hydrogen peroxide, which is a significant oxidation product. Subsequently, it is easily degraded to form secondary compounds such as alkanols, alkyl-2-enables, alkyl-2,4-aldehyde, different ketones, alcohols, and hydrocarbons, producing unpleasant odors (flavor deterioration) and posing serious health risks to consumers (Rathod et al., 2021). Fish oil contains a high proportion of UFAs, as well as heme pigments and trace amounts of metal ions such as iron, copper, and cobalt that are easily oxidized. Fish oil oxidation not only causes fat to deteriorate, but also has a direct impact on sensory, color, and functional properties. Lipid oxidation is a free radical-induced chain reaction that typically occurs through different pathways, such as photooxidation (singlet O2), thermal oxidation (temperature dependent), enzymatic oxidation, and auto-oxidation (free radicals), primarily attacking PUFAs and propagating as a continuous free radical chain mechanism (Clarke et al., 2021). Lipid oxidation begins with the removal of unstable hydrogen atoms from fatty acyl chains that produce alkyl groups. Alkyl groups react with oxygen molecules to form peroxyl radicals. Peroxy radicals extract hydrogen from neighboring lipid molecules, forming lipid radicals and lipid hydroperoxide molecules (Cao et al., 2024). Lipid hydroperoxides are further degraded under the action of catalysts, resulting in the formation of several alkanes, aldehydes, ketones, and alcohols. Lipophilic antioxidants (e.g., TBHQ, PG, and TP) quench free radicals (e.g., peroxyl [ROO−] and alkoxyl [RO−] radicals) generated during autoxidation, thereby terminating chain propagation reactions. This directly reduces the formation of secondary oxidation products (e.g., aldehydes, ketones) responsible for off-flavors of fish oil.

Untargeted lipidomic profiling revealed that antioxidant-treated fish oil exhibited significantly lower levels of oxidized TG and PE containing UFAs compared to untreated Cons. It was used to identify specific oxidized lipid species that served as precise markers of oxidation pathways, going far beyond traditional metrics like POV or AV. This aligns with the inhibition of PUFA degradation pathways (e.g., C20:4, C20:5, and C22:6 oxidation), which are critical precursors of rancid flavors. Despite revealing group separation trends, the PLS-DA model exhibited limited predictive power, as indicated by a low Q2 value (Q2 = 0.0648). This was likely attributable to the relatively small sample size (n = 3) in the context of high-dimensional metabolomic data, a known challenge that could lead to overfitting and unstable model performance. Consequently, the model was interpreted with caution regarding its predictive capabilities. TG (12:1e/6:0/18:3, 12:1e/6:0/16:0, 20:3e/10:1/10:3, 14:0/12:4/20:4), DG (18:1/22:6), PE (8:1e/15:0, 18:0/15:0, 34:1/14:4, 20:1/11:3), and PEt (18:0/15:0) were the key molecules of TBHQ and PG to inhibit the degradation of accelerated oxidized fish oil from silver carp viscera (Fig. 4C). The single-factor correlation network diagram also showed that TG, DG, PE, and PEt were associated lipid molecules in which antioxidants play a role in inhibiting the oxidation of fish oil (Fig. 5A). This suggests that TBHQ and PG might inhibit the oxidation process of fish oil by suppressing the conversion of TG to DG and PE to PEt pathways. TGs could be hydrolyzed into DGs by endogenous hydrolytic enzymes, and DGs could be re-esterified into TGs by endogenous esterifying enzymes (Deaver & Popat, 2022). Lipase-mediated hydrolysis of TG to DG and FFAs increases the pool of oxidizable substrates. FFAs, particularly PUFAs, are highly prone to autoxidation due to their bis-allylic hydrogen atoms. By inhibiting TG hydrolysis via lipase suppression, TBHQ and PG could reduce FFA availability, thereby limiting oxidative chain reactions. PE can be hydrolyzed by phospholipases to release phosphoethanolamine (PEt) and other products (e.g., phosphatidic acid) (Marchisio et al., 2022). TBHQ and PG might target phospholipase activity or stabilize PE by blocking enzyme activation. TG-derived FFAs and PEt are precursors for volatile aldehydes (e.g., MDA, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal) via β-scission of hydroperoxides. By suppressing TG-to-DG and PE-to-PEt pathways, TBHQ and PG reduce the substrate pool for secondary oxidation, mitigating rancidity. In addition, PE might act as an antioxidant to inhibit lipid oxidation of accelerated fish oil from the silver carp viscera. It was reported that PLs could protect fish oil against lipid oxidation (Donmez et al., 2024). Zhu et al. (2023) demonstrated that compared to soybean PLs, yellow croaker roe PLs have significant antioxidant activity and it can effectively improve the thermal and oxidative stability of fish oil, thereby extending its shelf life. Altogether, the inhibition of TG-to-DG and PE-to-PEt conversions represents a plausible mechanism for TBHQ and PG in preserving fish oil stability.

4.2. Analysis of the mechanism of antioxidants in suppressing flavor deterioration of fish oil

The deterioration of fish oil flavor, mainly derived from silver carp viscera, was predominantly driven by lipid oxidation, which generated volatile secondary oxidation products such as aldehydes (N-nonyl aldehyde, (E, E)-2,4-heptadienal, (E)-2-nonylaldehyde, nonanal) and alcohols (1-octene-3-ol, eugenol) (Table 2). These compounds contributed to off-flavors characterized by rancidity, fishiness, and metallic notes. Antioxidant TBHQ and PG mitigated this process by interrupting the oxidative cascade at critical stages, thereby preserving lipid stability and flavor quality. Current research is predominantly limited to preliminary studies on the effects of antioxidants in mitigating lipid oxidation in PUFA-rich fish oils, with few investigations correlating lipid oxidation with flavor deterioration. For instance, Xue et al. (2023) found that omega-3 PUFAs were more easily oxidized compared to other PUFAs, and the UFAs at the sn-2 position and those closest to the carbonyl group were oxidized first. In the present study, we found that TG, DG, and PE containing PUFAs exhibited significant correlations with critical deteriorating flavor compounds 1-octene-3-ol and eugenol, which were inhibited by antioxidants of TBHQ and PG. This implied that antioxidants such as TBHQ and PG might inhibit the accelerated conversion process of TG, DG, and PE containing PUFAs in fish oil into deteriorating volatile flavor compounds such as aldehydes and alcohols. However, Wen et al. (2023) also found that the oxidation of oleic acid (C18:1)and linoleic acid (C18:2) also contributes to the off-flavor in fish oil.

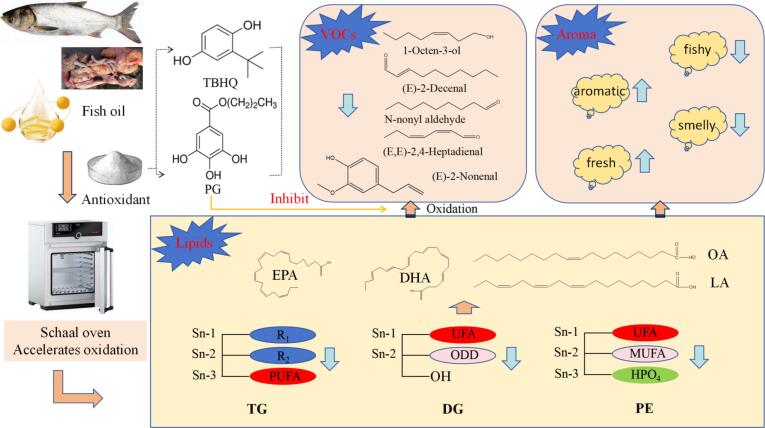

The aldehydes in the flavor deterioration of accelerated oxidized fish oil originated from the double bond cleavage of UFAs. Thermal processing promoted fish oil oxidation, leading to the rupture of double bonds (C C) in unsaturated long-chain fatty acids (Yu et al., 2021). In foods (particularly in fats and oils containing PUFAs) during oxidation or thermal degradation processes, (E)-2-decenal can be generated as a product of lipid peroxidation reactions, such as from the breakdown of C18:2 or linolenic acid (Zhao et al., 2024). Current research has found that (E)-2-decenal exhibited a significant positive correlation with PE(14:0e/18:1). Antioxidants such as TBHQ and PG might inhibit the hydrolysis of PE into C18:1, thereby preventing its oxidative degradation and subsequent generation of (E)-2-decenal (Fig. 6). Nonanal might originate from C18 PUFAs such as C18:2 and α-linolenic acid (C18:3). These fatty acids underwent oxidation to form hydroperoxides, which subsequently decomposed via beta-scission to produce short-chain aldehydes (Liu et al., 2024). Correlation analysis has revealed significant positive associations between nonanal and specific lipid species, namely DG (16:0/22:6) and TG (16:1e/6:0/10:4) (Fig. 5B). Antioxidants such as TBHQ and PG likely suppress the oxidative degradation of UFAs (DHA) and palmitoleic acid derived from DG (16:0/22:6) and TG (16:1e/6:0/10:4), thereby inhibiting their conversion into nonanal.

Fig. 6.

The possible mechanism of antioxidants in suppressing flavor deterioration of fish oil.

The presence of alcohols in rancid fish oil primarily stemmed from the oxidative degradation of UFAs, where the cleavage of hydroperoxides (formed during autoxidation) generated volatile alcohols, such as 1-octen-3-ol, which were key contributors to metallic and grassy off-notes (Cheng et al., 2023). 1-Octen-3-ol is a volatile compound characterized by a mushroom-like or earthy odor. It is primarily formed through the oxidation or enzymatic degradation of PUFAs, particularly linoleic acid (C18:2). The hydroperoxide derivatives of C18:2 (e.g., 13-hydroperoxy-octadecadienoic acid, 13-HPODE) are cleaved by hydroperoxide lyase (HPL) into C10 carbonyl compounds (such as 10-oxo-8-decenoic acid) and C8 fragments. These C8 fragments are subsequently reduced or dehydrated to generate 1-octen-3-ol (Miyazaki et al., 2023). While α-linolenic acid (18:3 ω-3) may also act as a precursor fatty acid under specific conditions, it contributes minimally to C8 products like 1-octen-3-ol (Chen, He, et al., 2024; Chen, Zhang, et al., 2024). Similarly, arachidonic acid (20:4 ω-6), EPA, and DHA in animal fats may generate structurally similar alcohols via oxidation, though their contributions are minor (Jiarpinijnun et al., 2022). In the current study, we found significant negative correlations between 1-octen-3-ol and TG, DG, and PE containing C18:1, C18:2, EPA, and DHA (Fig. 5B). Antioxidants such as TBHQ and PG might inhibit the formation of 1-octen-3-ol by blocking the oxidative chain reactions of C18:1, C18:2, EPA, and DHA, thereby reducing hydroperoxide formation and interrupting its downstream degradation pathway (Fig. 6). Eugenol is a natural phenylpropanoid compound, and its biosynthesis primarily follows the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway, which relies on phenylalanine as the starting precursor (Jiang et al., 2023). While fatty acid oxidation (e.g., β-oxidation) was not a direct source of eugenol, it might indirectly influence its synthesis by supplying energy (e.g., ATP) or metabolic intermediates. The present study has observed positive correlations between fatty acid metabolism and eugenol accumulation (Fig. 5B); however, this relationship is likely attributed to energy provision or regulation of metabolic flux, rather than direct contributions of fatty acid-derived precursors.

In a word, the possible molecular mechanism by which antioxidants inhibit the volatile flavor deterioration during oven-accelerated oxidation of silver carp visceral fish oil is shown in Fig. 6. TBHQ and PG suppressed the conversion pathways of polyunsaturated triacylglycerols (TG-DG) and PE-PEt, while simultaneously inhibiting the oxidative degradation of C18:1, C18:2, C18:2, EPA, and DHA into key deteriorated aldehyde ((E)-2-decenal and nonanal) and alcohol (1-octen-3-ol and eugenol) volatile flavor compounds in fish oil. This consequently delayed the generation of fishy odor and rancid off-flavors in the fish oil. However, the current study has not yet fully elucidated the molecular mechanisms by which TBHQ and PG specifically suppress the TG-DG conversion and PE-PEt pathways, nor has it clarified how they inhibit critical radical chain reactions or the formation of key volatile flavor deterioration intermediates during oxidation. Furthermore, the lipid-derived flavor precursors suppressed by TBHQ and PG, as well as the key intermediates responsible for inhibiting the formation of deteriorated flavors in fish oil, remain to be confirmed and systematically explored in future research.

5. Conclusion

This study employed integrated lipidomics and flavoromics approaches to elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which antioxidants suppress lipid oxidation and flavor deterioration in fish oil extracted from silver carp viscera. During accelerated oxidation periods, the addition of TBHQ, PG, and TP significantly inhibited lipid oxidation in fish oil, effectively decelerating the rate of increase in AV, POV, p-AV, TOTOX, polar components, and TBARS. Lipidomic profiling demonstrated that antioxidants preferentially preserved oxidation-prone TG-DG and mitigated phospholipid hydrolysis (PE-PEt), thereby stabilizing the overall lipid architecture. GC–MS identified 54 volatile compounds, revealing significant compositional and concentration-based differentiation in volatile profiles among antioxidant-treated fish oil samples during accelerated oxidation. OAV analysis pinpointed six critical odor-active compounds, with antioxidants effectively suppressing the formation of key flavor substances such as 1-octen-3-ol, (E)-2-decenal, and nonanal, thereby inhibiting the development of fishy odor. These mechanistic insights underscore the importance of targeting lipid oxidation pathways for comprehensive quality preservation. The findings advance sustainable valorization of silver carp viscera by reducing waste and enhancing the commercial viability of fish oil in nutraceutical and functional food applications.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Bin Peng: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis. Linchuan Xu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Liping Yuan: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Chengwei Yu: Writing – review & editing, Resources. Mingming Hu: Formal analysis, Data curation. Bizheng Zhong: Software, Resources. Zongcai Tu: Project administration, Funding acquisition. Jinlin Li: Visualization, Validation, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD2100904), Outstanding Youth Project of Jiangxi Natural Science Foundation (20224ACB215010), Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (20232BAB215060, 20242BAB25407), and the earmarked fund for CARS (CARS-45), the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (32260604).

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Beker S.A., da Silva Y.P., Bücker F., Cazarolli J.C., de Quadros P.D., Peralba M.C.R.…Bento F.M. Effect of different concentrations of tert-butylhydroquinone (TBHQ) on microbial growth and chemical stability of soybean biodiesel during simulated storage. Fuel. 2016;184:701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2016.07.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai D.L., Li X.Q., Liu H.F., Wen L.K., Qu D. Machine learning and flavoromics-based research strategies for determining the characteristic flavor of food: A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2024.104794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H., Xiong S.F., Dong L.L., Dai Z.T. Study on the mechanism of lipid peroxidation induced by carbonate radicals. Molecules. 2024;29(5):1125. doi: 10.3390/molecules29051125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanphai P., Bourassa P., Kanakis C.D., Tarantilis P.A., Polissiou M.G., Tajmir-Riahi H.A. Review on the loading efficacy of dietary tea polyphenols with milk proteins. Food Hydrocolloids. 2018;77:322–328. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2017.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., He Y.H., Li X.Y., Zhu H.B., Li Y.Y., Xie D., Z. Improvement in muscle fatty acid bioavailability and volatile flavor in tilapia by dietary α-linolenic acid nutrition strategy. Foods. 2024;13(7):1005. doi: 10.3390/foods13071005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Zhang M.Q., Feng T., Liu H.Y., Lin Y.X., Bai B. Comparative characterization of flavor precursors and volatiles in Chongming white goat of different ages by UPLC-MS/MS and GC-MS. Food Chemistry: X. 2024;24 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H., Mei J., Xie J. Analysis of key volatile compounds and quality properties of tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) fillets during cold storage: Based on thermal desorption coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (TD-GC-MS) LWT. 2023;184 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y.-E., Kang D.-H., Kim D.-K. Inactivation efficacy of combination treatment of propyl Gallate and UVA LED for Escherichia coli O157:H7 in apple juice. Journal of Food Science. 2025;90(8) doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.70488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke H.J., McCarthy W.P., O’Sullivan M.G., Kerry J.P., Kilcawley K.N. Oxidative quality of dairy powders: Influencing factors and analysis. Foods. 2021;10(10):2315. doi: 10.3390/foods10102315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaver J.A., Popat S.C. Handbook of waste biorefinery: Circular economy of renewable energy. 2022. Fats, oils, and grease (FOG): Opportunities, challenges, and economic approaches; pp. 285–308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donmez D., Limon J., Russi J.P., Relling A.E., Riedl K., Manubolu M., Campanella O.H. Encapsulation of fish oil, a triglyceride rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, within a maillard reacted lecithin-dextrose matrix. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research. 2024;18 doi: 10.1016/j.jafr.2024.101283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esazadeh K., Ezzati Nazhad Dolatabadi J., Andishmand H., Mohammadzadeh-Aghdash H., Mahmoudpour M., Naemi Kermanshahi M., Roosta Y. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of tert-butylhydroquinone, butylated hydroxyanisole and propyl gallate as synthetic food antioxidants. Food Science & Nutrition. 2024;12(10):7004–7016. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.4373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N., Wang L.Q., Jiang D.M., Wang M., Yu H., Yao W., R. Combined metabolome and transcriptome analysis reveal the mechanism of eugenol inhibition of aspergillus carbonarius growth in table grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) Food Research International. 2023;170 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.112934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiarpinijnun A., Geng J.T., Thanathornvarakul N., Keratimanoch S., Üçyol N., Okazaki E., Osako K. Identifying volatile compounds in rabbit fish (Siganus fuscescens) tissues and their enzymatic generation. European Food Research and Technology. 2022;248(6):1485–1497. doi: 10.1007/s00217-022-03977-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshnoudi-Nia S., Forghani Z., Jafari S.M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of fish oil encapsulation within different micro/nanocarriers. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2022;62(8):2061–2082. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1848793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A.J., Feng X.Y., Yang G., Peng X.W., Du M.Y., Song J., Kan J.Q. Impact of aroma-enhancing microorganisms on aroma attributes of industrial Douchi: An integrated analysis using E-nose, GC-IMS, GC-MS, and descriptive sensory evaluation. Food Research International. 2024;182 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2024.114181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.L., Bai J.R., Zhou H.J., Xu L.C., Yuan L.P., Yu C.W.…Peng B. Comprehensive lipidomics and flavoromics reveals the accelerated oxidation mechanism of fish oil from silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) viscera during heating. Food Chemistry. 2025 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.143651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J., Xiong Q.S., Yin Y.Y., Ling Z.Y., Chen S.J. The effects of fish oil on cardiovascular diseases: systematical evaluation and recent advance. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2022;8:802306. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.802306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Liu Y.H., Bai F., Wang J.L., Xu H., Jiang X.M.…Xu X.X. Multi-omics combined approach to analyze the mechanism of flavor evolution in sturgeon caviar (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii) during refrigeration storage. Food Chemistry: X. 2024;23 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma P., Liu W.D., Wen H.L., Shen M.Y., Luo Y., Xie J.H. Comparative study of rosemary extract, TBHQ, citric acid and their composite antioxidants on the overall quality of peanuts and evaluation of their synergistic antioxidant properties and interaction. Food Research International. 2025;214 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2025.116623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchisio F., Di Nardo L., Val D.S., Cerminati S., Espariz M., Rasia R.M.…Castelli M.E. Characterization of a novel thermostable phospholipase C from T. Kodakarensis suitable for oil degumming. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2022;106(13):5081–5091. doi: 10.1007/s00253-022-12081-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascrez S., Aspromonte J., Spadafora N.D., Purcaro G. Vacuum-assisted and multi-cumulative trap in headspace SPME combined with comprehensive multidimensional chromatography-mass spectrometry for profiling virgin olive oil aroma. Food Chemistry. 2024;442 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.138409. Get rights and content. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitrowska K., Kijewska L., Giannetti L., Neri B. A simple and sensitive method for the determination of methylene blue and its analogues in fish muscle using UPLC-MS/MS. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A. 2023;40(5):641–654. doi: 10.1080/19440049.2023.2195948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki R., Kato S., Otoki Y., Rahmania H., Sakaino M., Takeuchi S.…Nakagawa K. Elucidation of decomposition pathways of linoleic acid hydroperoxide isomers by GC-MS and LC-MS/MS. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 2023;87(2):179–190. doi: 10.1093/bbb/zbac189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz A., Walayat N., Khalifa I., Harlina P.W., Irshad S., Qin Z., Luo X. Emerging challenges and efficacy of polyphenols–proteins interaction in maintaining the meat safety during thermal processing. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2024;23(2) doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.13313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira V.S., Viana D.S.B., Keller L.M., de Melo M.T.T., Mulandeza O.F., Barbosa M.I.M.J.…Saldanha T. Impact of air frying on food lipids: Oxidative evidence, current research, and insights into domestic mitigation by natural antioxidants. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2024.104465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rathod N.B., Ranveer R.C., Benjakul S., Kim S., Pagarkar A.U., Patange S., Ozogul F. Recent developments of natural antimicrobials and antioxidants on fish and fishery food products. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2021;20(4):4182–4210. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.Y., Liu L.L., Peng F.L., Ma Y.C., Deng Z.Y., Li H.Y. Natural antioxidants enhance the oxidation stability of blended oils enriched in USFA. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2024;104(5):2907–2916. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.13183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.X., Cui S.H., Liu J.J., Ye Z.H., Xu Y.F., Wang Z.Y.…Huang W.Q. The same species, different nutrients: Lipidomics analysis of muscle in mud crabs (Scylla paramamosain) fed with lard oil and fish oil. Food Chemistry. 2024;440 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.138174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.T., Guo X.Q., Qin Z.L., Liu R.Q., Li S.J., Du M.T.…Bai Y.H. Self-assembly of tea polyphenol onto the high strength chitosan film fabricated via a new way to enhance the antioxidant and antibacterial activity for meat preservation. Food Packaging and Shelf Life. 2025;49 doi: 10.1016/j.fpsl.2025.101482. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y.Q., Xue C.H., Zhang H.W., Xu L.L., Wang X.H., Bi S.J.…Jiang X.M. Concomitant oxidation of fatty acids other than DHA and EPA plays a role in the characteristic off-odor of fish oil. Food Chemistry. 2023;404 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M.Q., Yu Y.X., Li J., Bi Y.L., Liu J., Fu C.Y. A mechanistic perspective: How does tert-butylhydroquinone retain antioxidative efficacy in edible oils during towards a safer food chain: Recent advances in multi-technology based lipidomics application to food quality and safety. Storage? Food Chemistry. 2025;493 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2025.145963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue J., Wu H.X., Ge L.J., Lu W.B., Wang H.H., Mao P.Q.…Shen Q. Towards a safer food chain: Recent advances in multi-technology based lipidomics application to food quality and safety. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2024 doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2024.104859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Z.Y., Liu J., Li Q., Yao Y.Y., Yang Y.L., Ran C.…Zhou Z.G. Synthesis of lipoic acid ferulate and evaluation of its ability to preserve fish oil from oxidation during accelerated storage. Food Chemistry: X. 2023;19 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2023.100802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L.J., Wang Y., Wen H., Jiang M., Wu F., Tian J. Synthesis and evaluation of acetylferulic paeonol ester and ferulic paeonol ester as potential antioxidants to inhibit fish oil oxidation. Food Chemistry. 2021;365 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Cao G., Wang Z., Liu D., Ren L., Ma D. The recent progress of bone regeneration materials containing EGCG. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2024;12(39):9835–9844. doi: 10.1039/D4TB00604F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.N., Chen S.M., Liu L., Hu Q.Y., Zhang Y.H., Zhang Y.S.…Jiao W.J. In vitro gastrointestinal digestibility and lipid oxidation of fish oil-in-water emulsions: Influence of different EPA/DHA ratios. LWT. 2024;210 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2024.116855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y.J., Zheng X.H., Zeng Q.L., Zhong R.B., Guo Y.J., Shi F.F., Liang P. The inhibitory effect of large yellow croaker roe phospholipid as a potential antioxidant on fish oil oxidation stability. Food Bioscience. 2023;56 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2023.103291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data