Abstract

RNA modifications are critical in regulating gene expression and cell functions by affecting RNA stability, splicing, translation, and degradation. The catalytic core of N6-adenosine-methyltransferase catalytic subunit METTL3 has emerged as a key enzyme in tumorigenesis by enhancing the translation efficiency of oncogenic transcripts, which is a promising therapeutic target for cancers, including acute myeloid leukemia. In this study, we presented a novel METTL3 inhibitory bioactivity (pIC50) prediction model (ML3-mix-DPLIFE) by combining machine learning, protein–ligand docking, and protein–ligand interaction analysis, through encoding the conventional physicochemical properties, chemical fingerprint, and the docking-based protein–ligand interaction features (DPLIFE) with leveraging auto-stacking 6 algorithms. A feature selection algorithm further optimized the model (ML3-mix-DPLIFE-FS) and obtained a promising mean squared error (MSE) of 0.261 and a Pearson’s correlation coefficient (CC) of 0.853 on an independent test dataset, and identified 8 residues critical for ligand interactions with METTL3. To further test the model, the pIC50s of recently reported inhibitors were predicted using the ML3-mix-DPLIFE-FS model, and a good MSE of 0.418 and CC of 0.727 were obtained. This innovative strategy seamlessly integrates machine learning prediction with structural biology insights and reveals a novel way to identify key protein–ligand interactions for further structural rational drug design.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-20634-1.

Keywords: Human N6-adenosine-methyltransferase catalytic subunit METTL3 , Machine learning, Feature selection, Protein–ligand docking, The docking-based protein–ligand interaction features (DPLIFE)

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Drug discovery

Introduction

RNA modifications are essential for regulating gene expression and cellular functions, influencing various biological processes, and governing non-coding RNAs1, including tRNAs, rRNAs, and microRNAs. The most abundant internal modification in eukaryotic mRNA significantly impacts various aspects of RNA metabolism, including stability, splicing, translation, and degradation2. To date, over a hundred different types of RNA chemical modifications have been identified in many types of RNAs, including mRNA, rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, microRNA, and long noncoding RNA3. Common modifications include 5-methylcytosine (m5C)4,5, N7-methylguanosine (m7G)6, N1-methyladenosine (m1A)7, N4-acetylcytidine (Ac4C)8, pseudouridine (Ψ)9, 2′-O-methylation (Nm)10, N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am)11, and N6-methyladenosine (m6A) 12–14. Among these modifications, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) stands out as the most prevalent and conserved ribonucleotide modification15, in which over 25% of human transcripts have been identified with more than 12,000 m6A occurrences16. The N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification, is a complex process involving the crucial participation of multiple proteins that add (writers), recognize (readers), and remove (erasers) the m6A marks3,17.

N6-adenosine-methyltransferase catalytic subunit METTL3 (METTL3) and its non-catalytic subunit METTL14 form the catalytic core of the m6A RNA methyltransferase complex, a critical player in post-transcriptional RNA modification18. These two components were further supported by regulatory elements, including WTAP17,19, RBM1520,21, VIRMA22, ZC3H1323, YTHDF23,24, and HAKAI25. METTL3’s primary function is to catalyze the addition of methyl groups to the N6 position of adenosine residues, enabling the fine-tuning of RNA stability, splicing, and translation. Its critical role in RNA metabolism has positioned METTL3 as a key regulator of cellular processes, with its dysfunction linked to a range of diseases. In oncology, METTL3 has been extensively studied for its role in promoting tumorigenesis. Elevated METTL3 expression has been observed in cancers such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML)26,27, hepatocellular carcinoma28, and lung adenocarcinoma29,30. In AML, METTL3-mediated m6A methylation promotes the translation of oncogenic transcripts, such as MYC and BCL2, which are crucial for leukemia cell proliferation and survival31. Targeting the methyltransferase activity of METTL3 presents a promising strategy to regulate m6A methylation patterns and modulate oncogene expression, offering potential therapeutic benefits in cancer treatment32.

Recent advances in prediction models related to METTL3 have primarily focused on identifying m6A RNA modification sites. The machine learning model m6Aboost, for instance, tackled the problem of false positives in antibody-based m6A detection by using miCLIP2 datasets33. Similarly, the iM6A deep learning model presented high accuracy in predicting m6A deposition sites while identifying critical cis-element sequences that govern site-specific methylation34. Recent research has demonstrated that METTL3 has an m6A target-selective role31,35, with the development of numerous small-molecule inhibitors targeting METTL3 against acute myeloid leukemia, gastric cancer, and neuroblastoma tumor suppression, such as UZH2 and STM245718,36,37. Nevertheless, the prediction model for METTL3 inhibition on drug development has yet to be developed.

To facilitate the drug development for METTL3, this study presented a prediction model using a novel machine learning strategy to conquer the dataset limitation. Due to the small data size of two publicly available datasets of METTL3 inhibitors, the bioactivity distribution of the two datasets derived from METTL3 and METTL3-METTL14 experiments were carefully compared and merged. To overcome the limited number of inhibition bioactivity data for the target protein, a comprehensive approach combining machine learning, protein–ligand docking, and protein–ligand interaction analysis was utilized. This innovative strategy seamlessly integrates computational predictions with structural biology insights, enabling the accurate identification of potent METTL3 inhibitors. Models were developed using AutoGluon, a stacking algorithm leveraging 6 machine learning algorithms for achieving high performance. An optimized METTL3 bioactivity prediction model was developed using the merged datasets with the integration of contact residues of METTL3-ligand docking analysis. Furthermore, key residues with significant impacts on bioactivity were identified using forward feature selection through the minimum redundancy maximum relevance (mRMR) algorithm38, providing critical guidance for the rational design of future METTL3-targeting inhibitors. The developed model was effective in identifying METTL3 inhibitors and was further validated by external data of recently published inhibitors from the literature.

Methods

The programs were developed on the Ubuntu 20.04 operating system using Python 3.7.11. To achieve various analytical tasks, several Python packages were utilized: numpy and pandas for data manipulation, matplotlib for visualization, scikit-learn for machine learning, rdkit-pypi for cheminformatics, torch and AutoGluon v0.5.239 for machine learning.

Datasets

Two datasets (DB1 and DB2) of chemicals and the human METTL3 IC50 bioactivities were obtained from ChEMBL40. DB1 contains 151 IC50 values for METTL3/METTL14 inhibitors (CHEMBL4106140) and DB2 consists of 607 IC50 values for METTL3 inhibitors (CHEMBL4739695). A merged dataset of DB1 and DB2 was developed by removing duplicates and was composed of 644 chemicals and their corresponding IC50 values. The negative logarithm of the IC50 values (pIC50) was used as the label for model training.

Protein–ligand docking and docking-based protein–ligand interaction feature encoding (DPLIFE)

For conventional model development, each record of protein–ligand bioactivity was encoded by two commonly used features of 1024 bits of extended-connectivity fingerprints with a diameter of 6 atoms (ECFP)41 by RDKit42 and 1444 physicochemical properties by PaDEL-Descriptor43. As protein–ligand docking can provide better structural insights, we propose incorporating the docking-based protein–ligand interaction features (DPLIFE) to further improve the prediction model.

To compute the DPLIFE feature, the reported human METTL3-METTL14 ligand-bound crystal structure was used (PDB ID: 7O2I)37 for docking experiments with its small inhibitor compound STM2457 removed. The open-source RDKit toolkit 2022.9.442 with Python version 3.7.11 was utilized to generate the three-dimensional structures of ligands. The protein structure was prepared and protonated using the AMBER-FB15 force field44. Protein–ligand docking was performed to analyze potential binding pockets and protein–ligand interactions using AutoDock Vina 1.1.2 following the protein–ligand docking protocol45. The compound STM2457 was employed to validate the docking procedure, ensuring the accuracy of the redocking process with less than 0.8 Å root-mean-square deviation (RMSD). This threshold confirmed that the docking protocol could reliably reproduce the experimentally observed binding pose, thereby validating the precision of the docking methodology for further analyses.

DPLIFE features consisting of one feature of docking score and 185 features of protein–ligand interaction profile were extracted from the docked complex generated from the abovementioned docking process. The protein–ligand interaction features were calculated based on the analysis results of the Protein–Ligand Interaction Profiler (PLIP) tool46,47. Target-specific docking analyses were conducted using the crystal structure (PDB ID: 7O2I), which comprises 205 residues. The C-terminal 20 residues without interaction with ligands were removed. The remaining 185 residues-specific interactions were subsequently encoded into numeric features for further model development. The interaction types were coded as follows: 0 for no interaction, 1 for hydrophobic interactions, 2 for π-π stacking, 3 for π-cation interactions, 5 for salt bridges, and 6 for hydrogen bonds.

Principal component analysis (PCA) and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) analysis

To evaluate the chemical space distribution and compatibility of combining two ligand datasets (DS1: CHEMBL4106140 and DS2: CHEMBL4739695) for METTL3 inhibitor modeling, principal component analysis (PCA)48 and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE)49 were conducted. Prior to dimensionality reduction, non-structural features, i.e. molecular identifiers, SMILES strings, and bioactivity labels, were excluded. The PCA was performed to extract 2 principal components, with the explained variance examined to confirm that the primary chemical variance was captured. The t-SNE was applied to the same preprocessed data matrix using a perplexity of 160, 2 dimensions, and 1,000 iterations to preserve local chemical relationships. The results of both PCA and t-SNE analyses were visualized as scatter plots, with samples color-coded by dataset, allowing assessment of chemical space similarity.

Model development

To ensure a rigorous process for model development, the original dataset was uniformly divided into 64% training, 16% validation, and 20% test sets ratio for model training, validation, and independent test, respectively. To construct a prediction model, the AutoGluon-Tabular39 was used for developing an auto-staking50 model based on 6 different algorithms of neural networks51, LightGBM boosted trees52, XGBoost53, CatBoost54, random forests55, and extremely randomized trees56. The maximum training time was limited to 2 h. To assess model performance, both the mean squared error (MSE) and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (CC) were employed. The mean squared error (MSE) was utilized as the objective function for model training, as detailed in Eq. 1 below.

|

1 |

In this equation, Yi and yi represent the experimental and predicted values for each instance, and i and n denote the specific instance and the total number of instances, respectively. The formula for calculating CC was provided in Eq. 2 below.

|

2 |

In this equation,  represents the average of the experimental values for the variable being predicted while

represents the average of the experimental values for the variable being predicted while  denoting the average of the predicted values.

denoting the average of the predicted values.

Feature selection for identifying key residues

The minimum redundancy maximum relevance (mRMR) algorithm38 was used to rank the features based on the training dataset in order to determine which features were most pertinent for forecasting METTL3 bioactivities. Subsequently, a sequential forward feature selection algorithm57 was applied to select the optimal feature subset giving the highest validation MSE performance on the validation dataset. In brief, the top-ranked n features were selected for model development and validation using the training and validation datasets, respectively, where the feature number of n was incrementally increased until reaching a convergence of validation MSE values. Since the chemical fingerprint was usually considered as a whole, the feature selection applies only to the physicochemical properties and DPLIFE features while keeping the ECFP information unselected for model development. The incremental selection stops when less than 5% improvement in validation MSE value was obtained by including an additional feature.

Results and discussion

Ligand-based model development for METTL3 bioactivity

To develop prediction models of METTL3 inhibitory activities, two datasets of DS1 and DS2 sourced from CHEMBL4106140 and CHEMBL4739695 were collected. To investigate the potential for combining the two datasets to enlarge the training set, the bioactivity distributions of the two datasets were compared and found to be similar (Fig. S1). Principal component analysis (PCA)48 and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) analysis49, based on ECFP and physicochemical features, were then utilized to visualize the chemical spaces of the two datasets. As shown in Fig. 1, both datasets exhibit comparable bioactivity distributions. PCA analysis revealed that the first two principal components explain over 92% of the total variance and that the chemical spaces of DS1 and DS2 substantial overlap, indicating structural similarity between the datasets. Additionally, t-SNE visualization demonstrated that the two datasets occupy partially overlapping regions in chemical space, with clear areas of intersection. These analyses indicated that the two datasets possessed substantial structural similarity and overlap, suggesting enhancement of the chemical space coverage of the developed model by the combination of two datasets.

Fig. 1.

Chemical space visualization of DS1 and DS2 datasets using (A) the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) obtained from a principal component analysis (PCA), with explained variations shown in parentheses; (B) t-SNE.

Two single-dataset models (ML3-DS1 and ML3-DS2) were trained separately on DS1 and DS2 using features of ECFP and physicochemical properties employing AutoGluon-Tabular. The mixed-dataset model (ML3-mix) was trained on the concatenated DS1 and DS2 dataset, which pooled samples from both DS1 and DS2, removed redundant entries, and used their ECFP and physicochemical features. Table 1 shows the validation and test results of the developed models. The model training for ML3-DS1, ML3-DS2, and ML3-mix takes 29, 53, and 60 min. While good validation MSE of 0.176 and test MSE and CC of 0.057 and 0.971, respectively, were obtained for the ML3-DS1 model on the DS1 dataset, the generalization ability of ML3-DS1 was poor on the DS2 dataset. Similarly, the ML3-DS2 model with a good validation MSE of 0.335 and good test MSE and CC of 0.130 and 0.935, respectively, using the DS2 dataset performed poorly on the DS1 dataset. The overall test performance on both DS1 and DS2 datasets of ML3-DS1 and ML3-DS2 was poor performance with an MSE greater than 0.78 and a CC less than 0.62. It shows that a small dataset was not sufficient to train a robust model even with good validation and test results. It was therefore important to investigate the utilization of a combined dataset for developing a robust model.

Table 1.

The validation and test performance of developed models.

| Models | Training dataset | # features | MSE (validation) | DS1 test set | DS2 test set | Overall test set* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSE | CC | MSE | CC | MSE | CC | ||||

| ML3-DS1 | DS1 |

2478 (ECFP & PP) |

0.176 | 0.057 | 0.971 | 1.261 | 0.138 | 0.972 | 0.370 |

| ML3-DS2 | DS2 |

2478 (ECFP & PP) |

0.335 | 2.839 | 0.644 | 0.130 | 0.935 | 0.781 | 0.620 |

| ML3-mix | DS1 + DS2 |

2478 (ECFP & PP) |

0.303 | 0.231 | 0.829 | 0.296 | 0.830 | 0.280 | 0.829 |

| ML3-mix-DPLIFE | DS1 + DS2 |

2664 (ECFP, PP & DPLIFE) |

0.307 | 0.168 | 0.874 | 0.299 | 0.840 | 0.264 | 0.849 |

| ML3-mix-DPLIFE-FS | DS1 + DS2 |

1636 (ECFP, PP-FS & DPLIFE-FS) |

0.309 | 0.168 | 0.874 | 0.294 | 0.845 | 0.261 | 0.853 |

CC, Pearson’s correlation coefficient; MSE, mean squared error; ECFP, extended-connectivity fingerprints; PP, physicochemical properties, DPLIFE, docking-based protein–ligand interaction features; PP-FS, selected PP features; DPLIFE-FS, selected DPLIFE features; *: the combined test set of DS1 and DS2 test sets. The baseline performances were indicated with underscores, while the improved performances were highlighted in bold font.

The performance of the ML3-mix model utilizing both DS1 and DS2 datasets was reasonably good with a validation MSE of 0.303 and test MSE and CC of 0.280 and 0.829, respectively using the combined dataset. The test MSE and CC on individual datasets were satisfying with 0.231 and 0.829 for DS1 and 0.296 and 0.830 for DS2. These results indicate that dataset integration was beneficial for model development.

Incorporation of protein–ligand interaction features (DPLIFE) for model improvement

While the ligand-based model provides good performance on the prediction of pIC50 values of METTL3 ligands, no structural insights into the protein–ligand interactions can be obtained from ligand-based approaches making further validation and investigation difficult. To overcome the limitation, this study incorporated the protein–ligand interaction information to facilitate the identification of METTL3 inhibitors. In short, the protein–ligand docking process was conducted to identify potential ligand binding poses based on the human METTL3-METTL14 heterodimer crystal structure (PDB ID 7O2I)37 with the inhibitor STM2457 removed (Fig. 2). The docking-based protein–ligand interaction information (DPLIFE) was then represented as numeric feature vectors including one feature of the docking score and 185 protein–ligand interaction features.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of the stacked ensemble model development for the METTL3 bioactivities using 186 docking-based protein–ligand interaction features (DPLIFE), 1024-bit chemical fingerprint (ECFP), and 1444 physicochemical features.

A ML3-mix-DPLIFE model was developed using the mixed dataset. As shown in Table 1, a slightly increased validation MSE of 0.307 was obtained, while a significant improvement on the DS1 test set and a slight improvement on the DS2 test set was found. The test MSE and CC were 0.168 and 0.874 for the DS1 test set, and 0.299 and 0.840 for the DS2 test set, respectively. The overall test performance of MSE and CC for ML3-mix-DPLIFE were 0.264 and 0.849, which was better than the ML3-mix model with 0.280 and 0.829, respectively. The results showed that the DPLIFE features could facilitate learning from small datasets.

Permutation feature importance assay

A permutation feature importance assay was performed to thoroughly evaluate the individual and combined contributions of each feature set (Table S1). The model integrating all features, ECFP, PP, and DPLIFE, yielded the highest performance (MSE 0.264, CC 0.849). When evaluated individually, the model using only PP demonstrated superior performance (CC 0.833) compared to models using only ECFP (CC 0.788) or only DPLIFE (CC 0.500) (Table S1). Combinations of DPLIFE with either ECFP or PP resulted in only marginal improvements over the respective single-feature models, with less than a 1% increase in CC. The resulting order of feature importance for predictive accuracy was determined as PP > ECFP > DPLIFE. While DPLIFE features alone had limited predictive power, their inclusion with molecular fingerprints and physicochemical properties improved model robustness and accuracy, resulting in more than a 2.4% improvement in CC. This analysis suggested the necessity of feature complementarity for developing effective and generalizable predictive models for METTL3 bioactivity.

Identification and analysis of key residues for METTL3 bioactivities

Since the incorporation of DPLIFE features was useful for improving the model performance, it was therefore interesting to know which were the key residues and interactions by using machine learning algorithms. To achieve this goal, an mRMR‐based forward feature selection algorithm was used to identify the most relevant DPLIFE features and physicochemical property features.

As shown in Fig. 3A, the MSE performance was converged in the feature number of 1,636 with a validation MSE of 0.309 which was similar to the model using the full feature set. The feature selection removed redundant and irrelevant features with reduced training time while keeping the performance unaffected. The final feature set includes 1,024 ECFP, 603 physicochemical properties, and 9 DPLIFE (i.e. 8 key contact features and one docking score feature) (Fig. 3B). The selected DPLIFE features comprised 8 key protein–ligand contact residues and one docking score. The model ML3-mix-DPLIFE-FS based on the selected features yields a slightly reduced test MSE of 0.261 and an improved test CC of 0.853 (Table 1) for the overall test set. Excluding a significant number of DPLIFE features was reasonable by the observation that only a few key residues were responsible for the bioactivity of proteins, consistent with the fact that fewer than 2% of protein residues were involved in binding and activity58.

Fig. 3.

The mRMR‐based forward feature selection. (A) The validation performance of top-ranked features with the highlighted final feature set. (B) Composition of the final feature set; the 603 selected physicochemical features were listed in Table S2. (C) The identified 8 key residues (red sticks) critical for METTL3 bioactivities (PDB ID: 7O2I). The inset table ranks these residues by mRMR relevance score.

The 8 key residues influencing METTL3 bioactivities ranked by the mRMR algorithm were Arg 379, Pro 396, Ile 400, Trp 431, Trp 457, His 512, Lys 513, and Gln 550, in a sequential order. The identified residues were mapped onto the METTL3 structure (PDB ID: 7O2I) (Fig. 3C) for visualization. The mean pIC50 values of chemicals interacting with 0 and at least 1, 2, and 3 key residues out of the 8 key residues are 7.357, 7.494, 7.569, and 7.600, respectively, indicating a potential influence of the number of interacted key residues on the pIC50.

Numerous studies have explored the significance of key residues in METTL3 through mutagenesis experiments, providing critical insights into its catalytic mechanism and structural dynamics. Among the identified key residues, Lys 513, ranked second in this study, has been extensively studied using the Lys513Ala mutant. This mutation abolished the recruitment of the ligand’s adenosine and eliminated METTL3 catalytic activity, confirming its essential role in RNA methyltransferase function59. Similarly, His 512, ranked 7th in this study, exhibits flexibility in the apo state and was stabilized upon adenosine binding making the catalytic site accessible. Furthermore, Trp 457 and Trp 431, ranked 1st and 4th in this study, respectively, have been highlighted as essential aromatic residues forming the ligand-binding aromatic cages. These residues play pivotal roles in stabilizing the ligand within the METTL3 active site, a process vital for enzymatic activity35. Additionally, Pro 396, ranked third in this study, contributes significantly to ligand binding through its backbone carbonyl, which interacts with reactive groups and nearby ion pairs. This interaction was critical for the stability of the enzyme-ligand complex and efficient catalysis59. Likewise, Gln 550, ranked 6th in this study, was involved in stabilizing the hydroxyl groups of ribose in the ligand. Mutagenesis of this residue to alanine (Gln550Ala) was shown to moderately reduce enzymatic activity, indicating its supporting role in METTL3 function60. Furthermore, Pro 396 and Ile 400, ranked 3rd and 8th in this study, have been implicated as a key residue within gate loop 1 (Pro 396 - Gly 407)61, a flexible region critical for regulating cofactor and substrate binding, as well as product release62.

Independent test on external data of novel METTL3 inhibitors

Recent studies have introduced a series of novel bisubstrate analogs (BAs) as METTL3 inhibitors, with experimentally determined pIC50 values for 5 novel BAs (BA1, BA2, BA3, BA4, BA6) reported59. While the independent test on the test dataset has been conducted, an additional test on the unseen BAs structures can provide a better understanding of the model performance. The predicted pIC50 values using the ML3-mix-DPLIFE-FS model and experimentally determined pIC50 values of the 5 BAs were shown in Table 2. The BA2 and BA4, the two most effective inhibitors reported in the study, were predicted to be the best inhibitor with pIC50 values of 7.061 and 7.129, respectively, which closely aligned with the experimentally reported pIC50 of 8.046 and 7.74559. The CC between the predicted and experimental pIC50 values for all BAs was 0.727, with a mean squared error (MSE) of 0.418. BA6 exhibited the lowest predicted (6.021) and experimental (≤ 6.301) values, showing a promising tool for prioritizing inhibitors. Since experimental conditions can lead to a large variation of pIC50 values63, some deviation was expected when comparing the predicted and experimental values.

Table 2.

Comparison of predicted and experimentally reported bioactivities of recently reported METTL3 inhibitors.

| Newly discovered compounds from reference59 | Key residue interactions from reported structure* | Experimental pIC5059 | Predicted pIC50 | Docking score by AutoDock Vina45 (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA1 | Arg 379, Gln 550 | 6.461 | 6.965 | − 8.0 |

| BA2 | Arg 379, Pro 396, Ile 400, His 512, Lys 513, Gln 550 | 8.046 | 7.061 | − 7.3 |

| BA3 | Not available | 7.678 | 7.039 | − 8.4 |

| BA4 | Arg 379, His 512, Lys 513, Gln 550 | 7.745 | 7.129 | − 6.9 |

| BA6 | Arg 379, His 512, Lys 513, Gln 550 | ≤ 6.301 | 6.021 | − 8.5 |

For external benchmarking, the predictive performance of the ML3-mix-DPLIFE-FS model was evaluated against the recently reported deep learning-based bioactivity predictor HAC-Net64 and alternative approaches, including NNscore 2.065, and GNINA 1.366 (Table S4). The ML3-mix-DPLIFE-FS model showed strong predictive capability, with predicted pIC50 values for BA1, BA2, BA3, BA4, and BA6 closely matching experimental measurements, achieving a Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ) of 0.90. In comparison, conventional molecular docking with AutoDock Vina yielded a lower correlation (CC 0.62, ρ 0.80). Nevertheless, HAC-Net predictions for pKa showed weak association with experimental data (CC − 0.49, ρ − 0.30) (Table 2 and S4). In addition, NNscore 2.0 yielded negligible correlations (CC − 0.01, ρ − 0.30), and GNINA predictions were similarly weak correlations (CC − 0.43, ρ − 0.40). These results indicated that, for this test set, the ML3-mix-DPLIFE-FS model exhibited higher correlation with METTL3 inhibitor bioactivity data.

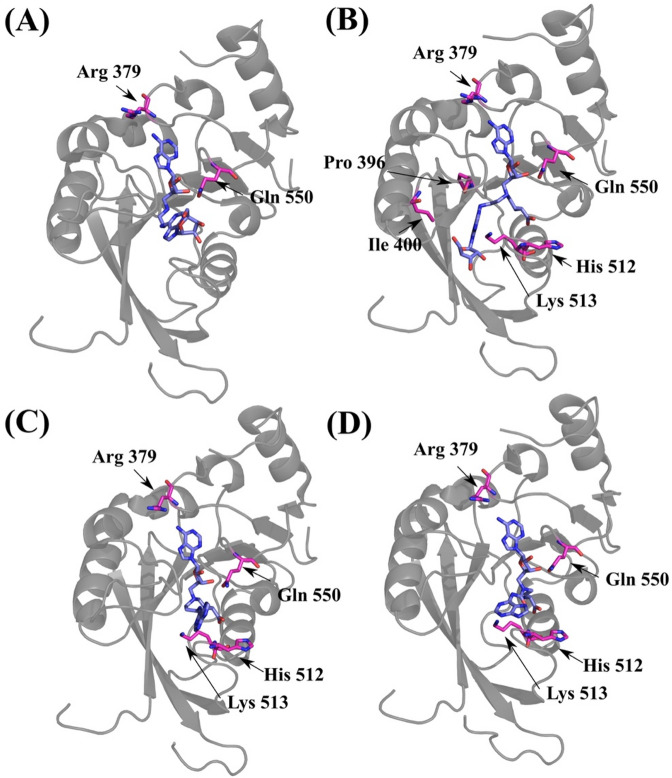

Since the cocrystal structures of these BAs have been reported59, the analysis of their binding poses and interactions with the identified 8 key residues can further validate the developed model. This study therefore highlighted the 8 key residues and the key residues within 4 Å of the ligand in the protein–ligand complex on the newly available crystal structures (Fig. 4). Results indicated that in every analyzed complex, at least 2 key residues were located in close proximity to the ligand, further substantiating their functional importance in inhibitor bioactivities. During the course of this study, three new METTL3-inhibitor cocrystal structures were published, allowing us to incorporate additional PDB entries (PDB IDs: 9G4S, 9G4U, and 9G4W) into our analyses. As shown in Fig. S2, the 8 key residues identified as essential for METTL3 bioactivity were consistently detected across all analyzed protein–ligand crystal structures. Analysis of these cocrystal structures further supports the elongated ligand binding pocket with 8 key residues in defining the binding pocket architecture required for METTL3 inhibition (Fig. S2).

Fig. 4.

Key residues relevant to METTL3 bioactivities in recently reported protein-inhibitor structures. (A) The METTL3-BA1 protein–ligand crystal structure (PDB ID: 8PW9). (B) The METTL3-BA2 protein–ligand crystal structure (PDB ID: 8PW8). (C) The METTL3-BA4 protein–ligand crystal structure (PDB ID: 8PWA). (D) The METTL3-BA6 protein–ligand crystal structure (PDB ID: 8PWB). The key residues within 4 Å of the ligand were highlighted in magenta stick representations.

Detailed analysis of METTL3–inhibitor cocrystal structures demonstrates that the ligand binding site is defined by the spatial arrangement of the 8 key residues: Arg 379, Pro 396, Ile 400, Trp 431, Trp 457, His 512, Lys 513, and Gln 550. These residues collectively shape an elongated binding pocket capable of accommodating a variety of inhibitors, as illustrated in Fig. 4 and Fig. S2. Notably, Trp 457 was consistently located within 4 Å of the bound ligands in the newly reported METTL3–inhibitor cocrystal structures (Fig. S2), indicating its frequent involvement as a lower pocket interaction residue. In contrast, this proximity was not observed in the BA-bound cocrystal structures (Fig. 4), suggesting potential differences in binding mode and pocket engagement between the newly reported inhibitors and the bisubstrate analogs. Further quantification of interaction contributions revealed that Trp 457 and Trp 431 are characterized by a high frequency of hydrophobic interactions with ligands (22.6% and 22.7%, respectively) (Table S3). Trp 431 also occasionally participates in π–π stacking interactions, highlighting the importance of both residues in providing aromatic and hydrophobic stabilization of the ligand. Hydrogen bonding is predominantly contributed by Arg 379, Pro 396, Gln 550, and Lys 513, with Gln 550 and Pro 396 exhibiting hydrogen bonding in 11.7% and 5.6% of cases, respectively. Additionally, Arg 379 forms salt bridges (0.2%) alongside hydrogen bonds, further anchoring the ligand within the binding pocket (Table S3). Notably, inhibitors exhibiting interactions with a greater number of these key interaction residues were observed to demonstrate enhanced effectiveness, highlighting the importance of these residues in the design of potent METTL3 inhibitors.

Conclusion

The discovery of METTL3 inhibitors has garnered significant interest in recent years due to their potential applications in cancer treatment67 and their potential as antiviral therapies68. METTL3, a key catalytic subunit of the m6A RNA methyltransferase complex, plays a critical role in modulating oncogenic and antiviral pathways by regulating RNA methylation. Targeting METTL3 provides a promising avenue for developing therapeutic interventions, particularly for cancers such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML), where it promotes the translation of oncogenic transcripts MYC and BCL2. This study introduces a novel method for METTL3 inhibitor discovery. In addition to conventional features of chemical fingerprint and physicochemical properties, the newly introduced DPLIFE features representing ligand–protein interaction information were found to be useful for improving model predictivity and interpretability. Eight key protein–ligand interaction residues were identified via feature selection, and the optimized ML3-mix-DPLIFE-FS model achieved high predictive accuracy, with predicted pIC50 values closely matching experimental IC₅₀ data for benchmark inhibitors. Validation with additional BAs confirmed both the model performance and the relevance of these residues. Considering the importance of interaction type and its contribution to the final prediction, which was not fully addressed in this work, future studies could incorporate interaction type–wise features derived from advanced protein–ligand complex modeling methods, such as NeuralPLexer69 and UMol70, to further improve accuracy and generalizability. This approach not only provided a powerful METTL3-focused drug discovery tool for addressing unmet therapeutic needs in oncology and virology, but also demonstrated a combinational methodology that could be applied to rational drug design for other targets.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- UniProtKB

The Universal Protein Knowledgebase

- METTL3

The methyltransferase 3, N6-adenosine-methyltransferase complex catalytic subunit (UniProtKB primary accession number: Q86U44)

- METTL14

The methyltransferase 14, N6-adenosine-methyltransferase non-catalytic subunit (UniProtKB primary accession number: Q9HCE5)

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- MYC

Myc proto-oncogene protein (UniProtKB primary accession number: P01106)

- BCL2

B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 protein; Apoptosis regulator Bcl-2 (UniProtKB primary accession number: P10415)

- DPLIFE

The docking-based protein–ligand interaction features

- CC

Pearson’s correlation coefficient

- IC50

Half maximal inhibition concentration

- MSE

Mean squared error

- RMSD

Root-mean-square deviation

- ECFP

Extended-connectivity fingerprints

- mRMR

The minimum redundancy and maximum relevance algorithm

- PDB ID

Protein data bank identifier

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- BA

Bisubstrate analog

Author contributions

W.C.H. and C.W.T. designed and conducted the experiments, wrote the main manuscript, and prepared all figures and tables. C.W.T. and H.P.H. contributed to project management and participated in manuscript editing and review. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants NSTC-113-2628-E-400-001-MY3 from the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan.

Data availability

Data and materials are available on GitHub [https://github.com/drhuangwc/METTL3] (https://github.com/drhuangwc/METTL3).

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Esteller, M. Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet.12, 861–874. 10.1038/nrg3074 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer, K. D. et al. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3′ UTRs and near stop codons. Cell149, 1635–1646. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang, Y., Hsu, P. J., Chen, Y. S. & Yang, Y. G. Dynamic transcriptomic m6A decoration: Writers, erasers, readers and functions in RNA metabolism. Cell. Res.28, 616–624. 10.1038/s41422-018-0040-8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Squires, J. E. et al. Widespread occurrence of 5-methylcytosine in human coding and non-coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res.40, 5023–5033. 10.1093/nar/gks144 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li, M. et al. 5-methylcytosine RNA methyltransferases and their potential roles in cancer. J. Transl. Med.20, 214. 10.1186/s12967-022-03427-2 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, Y., Lin, H., Miao, L. & He, J. Role of N7-methylguanosine m7G in cancer. Trends Cell. Biol.32, 819–824. 10.1016/j.tcb.2022.07.001 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu, Y. et al. Research progress of N1-methyladenosine RNA modification in cancer. Cell. Commun. Signal22, 79. 10.1186/s12964-023-01401-z (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kudrin, P., Singh, A., Meierhofer, D., Kusnierczyk, A. & Orom, U. A. V. N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) promotes mRNA localization to stress granules. EMBO Rep.25, 1814–1834. 10.1038/s44319-024-00098-6 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stockert, J. A., Weil, R., Yadav, K. K., Kyprianou, N. & Tewari, A. K. Pseudouridine as a novel biomarker in prostate cancer. Urol. Oncol.39, 63–71. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.06.026 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimitrova, D. G., Teysset, L. & Carre, C. RNA 2′-O-Methylation (Nm) modification in human diseases. Genes10, 117. 10.3390/genes10020117 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu, Y. et al. PCIF1, the only methyltransferase of N6,2-O-dimethyladenosine. Cancer Cell. Int.23, 226. 10.1186/s12935-023-03066-7 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rottman, F., Shatkin, A. J. & Perry, R. P. Sequences containing methylated nucleotides at the 5′ termini of messenger RNAs: Possible implications for processing. Cell3, 197–199. 10.1016/0092-8674(74)90131-7 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei, C. M., Gershowitz, A. & Moss, B. Methylated nucleotides block 5′ terminus of HeLa cell messenger RNA. Cell4, 379–386. 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90158-0 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boccaletto, P. et al. MODOMICS: A database of RNA modification pathways. 2021 update. Nucleic Acids Res.50, D231–D235. 10.1093/nar/gkab1083 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang, X. et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature505, 117–120. 10.1038/nature12730 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dominissini, D. et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature485, 201–206. 10.1038/nature11112 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su, S. et al. Cryo-EM structures of human m6A writer complexes. Cell Res.32, 982–994. 10.1038/s41422-022-00725-8 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiorentino, F., Menna, M., Rotili, D., Valente, S. & Mai, A. METTL3 from target validation to the first small-molecule inhibitors: A medicinal chemistry journey. J. Med. Chem.66, 1654–1677. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01601 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang, Q., Mo, J., Liao, Z., Chen, X. & Zhang, B. The RNA m6A writer WTAP in diseases: Structure, roles, and mechanisms. Cell. Death Dis.13, 852. 10.1038/s41419-022-05268-9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang, Y. et al. Enhancing m6A modification of lncRNA through METTL3 and RBM15 to promote malignant progression in bladder cancer. Heliyon10, e28165. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28165 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balacco, D. L. & Soller, M. The m6A writer: Rise of a machine for growing tasks. Biochemistry58, 363–378. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b01166 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yue, Y. et al. VIRMA mediates preferential m6A mRNA methylation in 3′UTR and near stop codon and associates with alternative polyadenylation. Cell Discov.4, 10. 10.1038/s41421-018-0019-0 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, Y. et al. N6-methyladenosine methylation-related genes YTHDF2, METTL3, and ZC3H13 predict the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Ann. Transl. Med.10, 1398. 10.21037/atm-22-5964 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chelmicki, T. et al. m6A RNA methylation regulates the fate of endogenous retroviruses. Nature591, 312–316. 10.1038/s41586-020-03135-1 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bawankar, P. et al. Hakai is required for stabilization of core components of the m6A mRNA methylation machinery. Nat. Commun.12, 3778. 10.1038/s41467-021-23892-5 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sabnis, R. W. Novel METTL3 modulators for treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML). ACS Med. Chem. Lett.12, 1061–1062. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00280 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hwang, K. et al. Targeted degradation of METTL3 against acute myeloid leukemia and gastric cancer. Eur. J. Med. Chem.279, 116843. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2024.116843 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan, F. et al. The role of RNA methyltransferase METTL3 in hepatocellular carcinoma: Results and perspectives. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol.9, 674919. 10.3389/fcell.2021.674919 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.An, Y. & Duan, H. The role of m6A RNA methylation in cancer metabolism. Mol. Cancer21, 14. 10.1186/s12943-022-01500-4 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang, S. et al. The N6-methyladenosine epitranscriptomic landscape of lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov.14, 2279–2299. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-23-1212 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vu, L. P. et al. The N6-methyladenosine (m6A)-forming enzyme METTL3 controls myeloid differentiation of normal hematopoietic and leukemia cells. Nat. Med.23, 1369–1376. 10.1038/nm.4416 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng, C., Huang, W., Li, Y. & Weng, H. Roles of METTL3 in cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic targeting. J. Hematol. Oncol.13, 117. 10.1186/s13045-020-00951-w (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kortel, N. et al. Deep and accurate detection of m6A RNA modifications using miCLIP2 and m6Aboost machine learning. Nucleic Acids Res.49, e92. 10.1093/nar/gkab485 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo, Z., Zhang, J., Fei, J. & Ke, S. Deep learning modeling m6A deposition reveals the importance of downstream cis-element sequences. Nat. Commun.13, 2720. 10.1038/s41467-022-30209-7 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moroz-Omori, E. V. et al. METTL3 inhibitors for epitranscriptomic modulation of cellular processes. ChemMedChem16, 3035–3043. 10.1002/cmdc.202100291 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yankova, E. et al. Small-molecule inhibition of METTL3 as a strategy against myeloid leukaemia. Nature593, 597–601. 10.1038/s41586-021-03536-w (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dolbois, A. et al. 1,4,9-Triazaspiro[5.5]undecan-2-one derivatives as potent and selective METTL3 inhibitors. J. Med. Chem.64, 12738–12760. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00773 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radovic, M., Ghalwash, M., Filipovic, N. & Obradovic, Z. Minimum redundancy maximum relevance feature selection approach for temporal gene expression data. BMC Bioinform.18, 9. 10.1186/s12859-016-1423-9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erickson, N. et al. AutoGluon-Tabular: Robust and accurate autoML for structured data. arXiv:10.48550/arXiv.2003.06505 (2020).

- 40.Mendez, D. et al. ChEMBL: Towards direct deposition of bioassay data. Nucleic Acids Res.47, D930–D940. 10.1093/nar/gky1075 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogers, D. & Hahn, M. Extended-connectivity fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model50, 742–754. 10.1021/ci100050t (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bento, A. P. et al. An open source chemical structure curation pipeline using RDKit. J. Cheminform.12, 51. 10.1186/s13321-020-00456-1 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yap, C. W. PaDEL-descriptor: An open source software to calculate molecular descriptors and fingerprints. J. Comput. Chem.32, 1466–1474. 10.1002/jcc.21707 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang, L. P. et al. Building a more predictive protein force field: A systematic and reproducible route to AMBER-FB15. J. Phys. Chem .B121, 4023–4039. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b02320 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eberhardt, J., Santos-Martins, D., Tillack, A. F. & Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J. Chem. Inf. Model.61, 3891–3898. 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adasme, M. F. et al. PLIP 2021: Expanding the scope of the protein-ligand interaction profiler to DNA and RNA. Nucleic Acids Res.49, W530–W534. 10.1093/nar/gkab294 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salentin, S., Schreiber, S., Haupt, V. J., Adasme, M. F. & Schroeder, M. PLIP: Fully automated protein-ligand interaction profiler. Nucleic Acids Res.43, W443–W447. 10.1093/nar/gkv315 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jolliffe, I. T. & Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci.374, 20150202. 10.1098/rsta.2015.0202 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maaten, L. v. d. & Hinton, G. Visualizing Data using t-SNE. Journal of Machine Learning Research9, pp. 2579–2605. https://www.jmlr.org/papers/v9/vandermaaten08a.html (2008).

- 50.Ting, K. & Witten, I. H. Stacking bagged and dagged models. In: ICML’97: Proc. of the Fourteenth International Conference on Machine Learning, 367–375.10.5555/645526.657147 (1997).

- 51.Schmidhuber, J. Deep learning in neural networks: An overview. Neural Netw.61, 85–117. 10.1016/j.neunet.2014.09.003 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ke, G. et al. LightGBM: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In:NIPS’17: Proc. of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. pp. 3149–3157 10.5555/3294996.3295074 (2017).

- 53.Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In:KDD’16: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. pp. 785–794 (2016). 10.1145/2939672.2939785

- 54.Dorogush, A. V., Ershov, V. & Gulin, A. CatBoost: Gradient boosting with categorical features support. arXiv:10.48550/arXiv.1810.11363 (2018).

- 55.Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn.45, 5–32. 10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geurts, P., Ernst, D. & Wehenkel, L. Extremely randomized trees. Mach. Learn.63, 3–42. 10.1007/s10994-006-6226-1 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chiu, Y. W., Tung, C. W. & Wang, C. C. Multitask learning for predicting pulmonary absorption of chemicals. Food Chem. Toxicol.185, 114453. 10.1016/j.fct.2024.114453 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kulandaisamy, A., Lathi, V., ViswaPoorani, K., Yugandhar, K. & Gromiha, M. M. Important amino acid residues involved in folding and binding of protein-protein complexes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.94, 438–444. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.10.045 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Corbeski, I. et al. The catalytic mechanism of the RNA methyltransferase METTL3. Elife12, RP2537. 10.7554/eLife.92537 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang, X. et al. Structural basis of N6-adenosine methylation by the METTL3-METTL14 complex. Nature534, 575–578. 10.1038/nature18298 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu, X., Ye, W. & Gong, Y. The role of RNA methyltransferase METTL3 in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Front. Oncol.12, 873903. 10.3389/fonc.2022.873903 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bedi, R. K., Huang, D., Li, Y. & Caflisch, A. Structure-based design of inhibitors of the m6A-RNA writer enzyme METTL3. ACS Bio. Med. Chem. Au.3, 359–370. 10.1021/acsbiomedchemau.3c00023 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalliokoski, T., Kramer, C., Vulpetti, A. & Gedeck, P. Comparability of mixed IC50 data—A statistical analysis. PLoS ONE8, e61007. 10.1371/journal.pone.0061007 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kyro, G. W., Brent, R. I. & Batista, V. S. HAC-Net: A hybrid attention-based convolutional neural network for highly accurate protein-ligand binding affinity prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model.63, 1947–1960. 10.1021/acs.jcim.3c00251 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Durrant, J. D. & McCammon, J. A. NNScore 2.0: A neural-network receptor-ligand scoring function. J. Chem. Inf. Model.51, 2897–2903. 10.1021/ci2003889 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McNutt, A. T., Li, Y., Meli, R., Aggarwal, R. & Koes, D. R. GNINA 1.3: The next increment in molecular docking with deep learning. J. Cheminform.17, 28. 10.1186/s13321-025-00973-x (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pomaville, M. et al. Small-molecule inhibition of the METTL3/METTL14 complex suppresses neuroblastoma tumor growth and promotes differentiation. Cell. Rep.43, 114165. 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114165 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim, G. W., Moon, J. S., Gudima, S. O. & Siddiqui, A. N6-methyladenine modification of hepatitis delta virus regulates its virion assembly by recruiting YTHDF1. J. Virol.96, e0112422. 10.1128/jvi.01124-22 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qiao, Z., Nie, W., Vahdat, A., Miller III, T. F. & Anandkumar, A. State-specific protein-ligand complex structure prediction with a multi-scale deep generative model. Nat. Mach. Intell.10.1038/s42256-024-00792-z (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bryant, P., Kelkar, A., Guljas, A., Clementi, C. & Noe, F. Structure prediction of protein-ligand complexes from sequence information with Umol. Nat. Commun.15, 4536. 10.1038/s41467-024-48837-6 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data and materials are available on GitHub [https://github.com/drhuangwc/METTL3] (https://github.com/drhuangwc/METTL3).