Abstract

Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3), a class III receptor tyrosine kinase essential for hematopoiesis, is a well-established oncogenic driver in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Canonical internal tandem duplications (ITD) and tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) mutations inform prognosis and guide targeted therapy. Recent evidence highlights FLT3 as a critical oncogenic hub in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), where its alterations extend beyond ITD/TKD mutations to include non-canonical mutations with only partially explored functional implications. Moreover, recently discovered regulatory mechanisms, mostly acting on the FLT3 locus, drive FLT3 overexpression in ALL, including transcriptional regulation by rearranged ZNF384, epigenetic modifications, novel circular-RNA URAD::FLT3 fusions, and 13q12.2 deletions leading to enhancer hijacking and topologically associated domain (TAD)-boundary disruptions. The impact of these alterations on leukemogenesis and the possibility to target them in ALL subtypes is discussed here. Data from the Functional Omics Resource of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (FORALL) across B- and T-ALL cell line subtypes drug screening, and from preclinical and clinical evidence reveals a variable efficacy in FLT3-mutated and FLT3-overexpressing ALL subtypes, supporting a molecularly guided treatment approach. Building on the success of FLT3 inhibitors in mutated AML and in light of the emerging results in patients lacking FLT3-ITD and in FLT3-like AML cases, presenting with a gene expression pattern similar to FLT3-mutated ones despite the absence of mutations, we discuss their potential in ALL and we consider novel therapeutic strategies, including new FLT3 inhibitors, antibody-based approaches, FLT3 CAR-T therapy, and synergistic drug combinations, such as FLT3 and BCL2 inhibition. These new insights reviewed here may redefine FLT3 as a pan-leukemic target, with ALL-specific activation mechanisms offering unique therapeutic windows. The implementation of FLT3 expression profiling and full-coding mutation screening in ALL (and in AML) diagnostics could unlock precision medicine approaches. By bridging the AML experience with ALL innovations, this review outlines a roadmap for FLT3-targeted therapies and combination strategies, underscoring the urgency of biomarker-driven clinical trials to optimize FLT3-directed interventions in acute leukemias.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12943-025-02455-y.

Keywords: Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3), Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), FLT3 inhibitor, Targeted therapies

Background

Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) is a transmembrane receptor that plays a critical role in hematopoiesis, primarily by regulating the proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells [1]. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), FLT3 is one of the most frequently mutated genes, detected in approximately 25–30% of newly-diagnosed adult patients [2–4]. The comparison between paired diagnosis and relapse samples has demonstrated that FLT3 mutations are dynamic, with changes occurring in approximately 20–40% of cases [5, 6]. Specifically, 14–35% of patients acquire FLT3 mutations at disease progression, while 8–28% of cases loose the mutation at relapse [5, 6]. Canonical mutations such as internal tandem duplications (ITDs) and tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) point mutations represent well-characterized oncogenic events [1]: they drive leukemogenesis and inform risk stratification and therapeutic decision-making [7–9].

In acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), FLT3 mutations occur in approximately 5% of cases, with a higher frequency in specific subgroups as KMT2A-rearranged (KMT2A-r) and hyperdiploid ALL [10–13]. Although the cure rate in ALL has increased significantly over the years, especially in pediatric patients, refractory or relapsed cases continue to pose a significant clinical challenge, particularly in the adult population [14–17].

The widespread use of next-generation sequencing (NGS), complemented by epigenetic (e.g., ChIP-seq, ATAC-seq), 3D genome analyses (e.g., Micro-C, Hi-C) and integrative multi-omics data analyses, has revealed a far more complex landscape of FLT3 alterations and regulatory mechanisms.

Indeed, growing evidence has highlighted that FLT3 dysregulation in AML and ALL extends beyond classical activating mutations. Some non-canonical FLT3 mutations, previously considered of uncertain significance, have been demonstrated to exert activating effects [18]. In parallel, novel molecular mechanisms of FLT3 overexpression have been discovered that result from transcriptional or epigenetic deregulation, independent of direct gene mutation. Epigenetically-driven FLT3 deregulation has been observed in specific acute leukemia subtypes, harboring BCL11B or ZNF384 rearrangements [19, 20]. Additionally, loss of regulatory elements within the 3D nuclear architecture at the FLT3 locus, such as enhancers or CTCF proteins, can disrupt normal chromatin interactions and result in FLT3 transcriptional activation [21–23]. Moreover, a novel layer of complexity has emerged with the identification of circular RNA (circRNA) and circRNA fusions involving the FLT3 locus with potential functional relevance [13, 24]. Therefore, the discovery of new druggable FLT3/FLT3-related alterations may offer innovative treatment strategies for ALL patients. This review will provide a comprehensive overview of current knowledge on FLT3, from biological functions to activation mechanisms, including pathways involved and its role in ALL and AML. Special emphasis is placed on the evolving understanding of FLT3 in ALL, where novel alterations and regulatory events are increasingly recognized. We also critically discuss the therapeutic implications of these discoveries, focusing on the potential of FLT3 inhibitors (i) in both canonical and non-canonical FLT3-altered (alt) ALL, and highlight future directions for research and clinical application.

FLT3 structure, activation and signal transduction

FLT3 gene, mapping on chromosome 13q12, includes 24 exons encoding for a transmembrane protein of 993 amino acids that belongs to the class III subfamily of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs). It consists of four regions: a N-terminal extracellular region (541 aa) with five immunoglobulin-like (IgG-like) domains (D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5), that are required for cell surface recognition, interaction with the ligand and receptor dimerisation [25]; a transmembrane region, and an intracellular module (431 aa) consisting of a juxtamembrane domain (JMD) and two tyrosine kinase (TK) subdomains (TKD1 and TKD2) connected by a kinase insert domain (Fig. 1A) [26]. The transcribed messenger RNA (mRNA) is glycosylated in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Moreover, N-acetylglucosamine, galactose, fucose, and mannose residues are added to the N-terminal code to facilitate the receptor migration to the plasma membrane [27]. Therefore, the human FLT3 has two forms: a 158-160-kDa glycosylated membrane-associated protein, and a cytoplasmic unglycosylated 130-143-kDa protein (Fig. 1B) [28].

Fig. 1.

FLT3 receptor structure and activities. A FLT3 domain organization and cellular localization. B Mechanism of activation and intracellular signal transduction of FLT3-wt receptor. C Intracellular signal transduction of FLT3-mut receptor. D1-D5: immunoglobulin-like domains; JMD: juxta membrane domain; TKD1/2: tyrosine kinase domains; A-loop: activation loop; G: glycosylated residue; FL: FLT3 ligand; P: phosphorylated residue

FLT3 is expressed almost exclusively in the hematopoietic tissues, predominantly in the bone marrow, lymph nodes, thymus, and spleen [29, 30]. In normal bone marrow, FLT3 is selectively expressed by CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells [30]. FLT3 expression is regulated by the interplay of multiple signaling pathways (JAK-STAT, PI3K, MAPK), transcription factors (PU.1, GATA-2, C/EBPα), epigenetic modifications (chromatin remodeling, DNA methylation) and microRNA-driven post-transcriptional mechanisms (miR-126, miR-155) [30–32]. Under normal conditions, the receptor is activated by binding to the FLT3 ligand (FL) on the cell surface through D1-D5 domains, followed by internalization, dimerization through the D3 IgG-like domain of two inactive monomers and conformational changes allowing TKDs phosphorylation [25, 30, 33]. The active/inactive status of the receptor is controlled by the positions of the N (TKD1) and C (TKD2) catalytic lobes, linked by the activating peptide A-loop (Asp-Phe-Gly DFG). In its inactive state (DFG-out), the A-loop adopts a closed conformation that blocks access to ATP and peptides, and the JM domain stabilizes the closed conformation through steric interactions. Tyrosine phosphorylation forces the A-loop to open (DFG-in), enabling catalytic activity [34]. Upon receptor dimerization and phosphorylation of at least a specific tyrosine residue at the JM domain, the A-loop adopts an open conformation, exposing the catalytic domain to ATP and substrates, leading to receptor activation [35].

FLT3 activation triggers multiple signaling cascades, regulating protein synthesis, metabolism, cell proliferation and survival through (i) interaction with adaptor proteins as SHC proteins, GRB2, GAB2, SHIP, CBL, and CBLB [35] and downstream activation of the JAK/STAT pathway (where STAT5 is indirectly activated via ERK pathway [36]) or the RAS pathway, which engages RAF, MEK, ERK kinases, and downstream activated RSK/CREB and ELK pathways, (ii) activation of PI3K and its effectors, including PDK1, AKT and mTOR, (iii) phosphorylation of other cytoplasmic proteins as PLCγ1, VAV, and FYN, involved in signaling amplification (Fig. 1B) [27].

Alterations of these complex regulatory networks are frequently observed in hematological malignancies, and in particular in AML and ALL, contributing to the abnormal growth and survival of leukemic cells [32, 37, 38]. In particular, FLT3-ITD drives constitutive direct STAT5 phosphorylation and transcriptional activity (Fig. 1C) [39, 40], which is not observed in FLT3-wt and in FLT3-TKD cells [40, 41]. Moreover, FLT3-ITD located in the TKD domain is responsible for an increased WEE1 protein stability (compared with FLT3-ITD in the JM), that in turn results in a stronger phosphorylation of CDK1, followed by its association with cyclin B1 and arrest in the G2/M cell cycle phase in response to midostaurin (Fig. 1C) [42]. Conversely, midostaurin induces cyclin B1 degradation in FLT3-ITD-JM cells that accumulate in the G1 phase. These data highlight the critical role of the WEE1–CDK1 axis in the FLT3-ITD context [42].

This review provides a comprehensive overview of FLT3 in AML and ALL, from mutation-driven and mutation-independent mechanisms of deregulated activity to the most relevant preclinical and clinical results obtained by FLT3–targeting therapeutic strategies, critically evaluating their potential application in ALL.

FLT3 mutations and deregulation in ALL and AML

Canonical FLT3 mutations

FLT3 is among the most frequently mutated genes in hematological malignancies and especially in AML, occurring in about 30% in adult patients and 10–15% in pediatric ones [43, 44]. The two most frequent and “canonical” FLT3 mutations in AML are internal tandem duplications (FLT3-ITD) and FLT3-TKD mutations (Table S2). FLT3-ITD mutations are in-frame duplicated DNA insertion of 3-to-over-400 base pairs, located predominantly within the JM domain or, less frequently (about 30% of FLT3-ITD cases), in the TDK1 (exon 15; “non-JMD” FLT3-ITD). FLT3-TKD mutations are point mutations (PM) or small deletions in the activation loop, most frequently occurring as D835 PM or deletions of residue I836 at TKD2 [1, 10, 45, 46] (Fig. 2 panel 1).

Fig. 2.

Mechanisms of FLT3 dysregulation in acute leukemias occurring at the FLT3 locus. 1. FLT3 mutational spectrum in AL, with a particular focus on mutations reported in ALL. Mutations, classified as canonical and non-canonical, encompass a range of mutations dispersed across various domains, including the Ig-like domains, JMD and TKD-1/2 regions. 2. Representative FLT3 gene fusions identified in leukemia, among which ETV6–FLT3 is the most commonly reported. 3. FLT3 upregulation via epigenetic activation in ZNF384-r B-ALL cases. In physiological conditions, the z-FLT3 enhancer is methylated and inactive. In ZNF384-r B-ALL cases, the ZNF384 fusion protein binds to z-FLT3, activating it through histone modifications (H3K27ac, H3K4me3), altering chromatin structure via CTCF, and recruiting RNA polymerase II to drive continuous FLT3 transcription. 4. The rt-circRNA URAD::FLT3 generated through read-through transcription and back-splicing, links URAD exon 1 with FLT3 exons 16, leading the loss of the extracellular and transmembrane domains, while conserving most of the TKDs. 5. Impact of TAD disruption on FLT3 expression. In healthy cell chromatin, FLT3 transcription is regulated by the R2. In B-ALL, deletions at the 5′ of the FLT3 gene involving PAN3 disrupt two neighbouring TAD boundaries, leading to enhancer hijacking by the R3 element within PAN3. This abnormal regulation increases FLT3 expression, contributing to leukemogenesis. 6. A focal 13q12.2 deletion in the FLT3::PAN3 locus (different from the one described in panel 5) removes the FLT3 and PAN3 promoters, triggering chromatin reorganization that juxtaposes a PAN3 enhancer with the CDX2 promoter (R4). This results in CDX2 upregulation and downregulation of FLT3 and PAN3 [black arrows indicate transcriptional direction and signal transduction; red arrows indicate increased FLT3 expression; R1: promoter element; R2: PAN3 regulator element; R3: distal enhancer element; R4: CDX2 promoter; z-FLT3: enhancer; Me: methylated; Me3: 3-methylated; Ac: acetylated; grey triangles: TAD; ZNF384: Zinc Finger Protein 384; PAN3: Poly(A) specific ribonuclease subunit PAN3; URAD: Ureidoimidazoline (2-Oxo-4-Hydroxy-4-Carboxy-5-) Decarboxylase; CDX2: Caudal Type Homeobox 2; UBTF: Upstream Binding Transcription Factor]

FLT3-ITD and TKD occur in approximately 25–30% and 7–10% of AML cases, respectively [47–49] with distinct molecular characteristics and clinical implications. FLT3-ITD has been closely associated with a poorer prognosis, increased relapse rates, and lower overall survival (OS) compared to FLT3-TKD [37, 50–53]. It is a marker of intermediate risk in patients treated by chemotherapy and identifies a subgroup of patients with intermediate benefit to venetoclax/azacitidine regimen [43, 54].

Recent evidence suggests that non-JMD FLT3-ITD mutations are associated with even poorer prognosis [lower CR rates, shorter relapse-free survival (RFS) and OS], with primary resistance to chemotherapy and lower sensitivity to tyrosine kinase inhibitors [1]. Moreover, multiple FLT3-mutated clones, including FLT3-ITD microclones, coexist at disease diagnosis and evolve during therapy. FLT3-ITD microclones are frequently found in patients who are diagnosed as FLT3-ITD negative by conventional approaches. FLT3-ITD microclones have been suggested to associate with NPM1 and DNMT3A mutations, a favorable ELN 2022 risk, and shorter relapse free survival [55]. When comparing FLT3-ITD mutated clones between disease diagnosis and relapse (to chemotherapy or chemotherapy + midostaurin), 24% of FLT3-ITD microclones were retained at the time of relapse and 43% of them became macroclones [56].

FLT3 mutations frequently co-occur with additional genetic alterations in AML, contributing to the molecular heterogeneity of the disease and impacting clinical outcomes. In particular, NPM1 (occurring in 32−61.3% of FLT3‑mut AML versus 10.5–40.6% of all AML cases) and DNMT3A (detected in 32.7–39.4% and 9.4–26.1%, respectively) are the predominant partner lesions (Table S2). Although most of our knowledge on FLT3 comes from AML, recent studies provided new insights into B- and T-ALL [13, 57].

FLT3 mutations occur in 2-14.4% of pediatric and adult ALL patients. Of them, 18.8–32.1% are TKD PM, and 6.3–21% are ITD alterations [13, 18, 57]. However, in a group of 43 de novo adult ALL cases, ITD mutations are reported as the most frequent aberrations, accounting for 35% of FLT3 mutations [58]. The prevalence of FLT3 mutations differs among ALL subtypes [13]. In adult and pediatric patients, a frequency of 5.3–7.5% and 3.1–4.1%, respectively, was reported in the B- and T-ALL subgroups [10, 59]. Among T-ALL, a higher incidence of FLT3-ITD, up to 35% of adult and 13% of pediatric cases, was described in early T-cell precursor-ALL (ETP-ALL) [60]. Moreover, 34.8% of patients aberrantly expressing CD117 (20.4% of T-ALL), normally not found in T cells, also carry FLT3 mutations, primarily ITDs [61].

Among the heterogeneous adults and pediatric B-Other subgroup (B-ALL lacking the most recurrent rearrangements and all routinely assessed classifying aberrations), 8.3% of FLT3-mut cases have been identified by whole-exome sequencing (WES) [62]. The incidence increases to 14.4–48.6% and 6.8–15.7% in childhood and adult cases with chromosomal abnormalities/hyperdiploidy and KMT2A-r, respectively [57, 59, 63, 64]. A high FLT3 mutational rate (10.1–13.5%) has also been detected with the PAX5-alt subtype [59, 63]. FLT3 co‑occurring mutations have been also identified in ALL patients, although the cohort size, except for few studies, is substantially smaller compared with AML. Based on the available data, the most frequently co-mutated genes in adults are NRAS, PAX5, and PTPN11, with KRAS also frequently observed in adolescents and young adults (AYA) (Table S2). In the pediatric cohorts the most commonly co‑mutated genes are KRAS, NRAS, PTPN11, CREBBP and CDKN2A, although their prevalence varies across studies, underscoring distinct genetic contexts that may underlie diverse therapeutic responses (Table S2).

Regarding its clinical relevance, FLT3-ITD has been associated with poor OS and disease-free survival (DFS) in a cohort including 44% of hyperdiploid ALL [58] and a recent study reported a lower rate of minimal residual disease (MRD)-negative status by day 19 among FLT3-mut compared with wild-type (wt) ALL (21.2% vs. 45.3%), suggesting poorer early treatment response [57]. A recent manuscript on acute leukemias of ambiguous lineage cases also assessed the FLT3-ITD allelic ratio by PCR-based fragment analysis [65]. The authors reported, in one out of four cases, a 0.69 FLT3-ITD allelic ratio, that was considered a high allelic ratio with clinical impact according to the ELN 2017 AML diagnostic criteria [43]. In the remaining cases, only the allelic frequency was reported based on NGS data, without calculation of the allelic ratio. Overall, a systematic evaluation of FLT3-ITD allelic ratio and of its potential relevance in ALL is still missing.

This data indicates that, while being a diagnostic marker in AML, FLT3 mutations also could play a significant role in ALL, with varying prevalence across subtypes. Their association with poor prognosis and lower MRD-negative rates suggests their clinical impact and highlights the need for tailored treatment strategies. Further investigation is needed to assess the presence and evolution of microclones and address the potential prognostic relevance of FLT3-ITD allelic ratio in B-ALL and T-ALL.

Beyond canonical mutations: the emerging landscape of non-canonical mutations and other rare genomic alterations

Given the established role of canonical FLT3 mutations, most studies focused on them, especially in the past [10, 66]. The advent of WES/whole-genome sequencing (WGS) technologies and deep full-coding targeted gene panels fostered a growing interest in the identification of non-canonical FLT3 mutations in the last few years (Fig. 2, panel 1). Special emphasis was placed on FLT3-JMD point mutations (not ITD), that, compared with FLT3-TKD have been associated with higher relapse rate, Shorter DFS and OS, particularly in patients under 60 years of age, demonstrating a prognostic profile similar to that observed with FLT3-ITDs. These results suggest that FLT3-ITD–targeted therapies may also be applicable to FLT3-JMD–positive patients [53].

Non-canonical mutations span all FLT3 domains [18] and can be classified into non-canonical point mutations (NCPMs), in-frame insertion-deletion (INDELs), frameshifts and other ITDs (in-frame insertion and duplication outside JM or TKD1). Some NCPMs located in TKD1/2, and JMD are recurrent (FLT3-NCPM-RPM), while others are rarer/non-recurrent (FLT3-NRPM).

Moreover, the mutational spectra differed between AML and ALL. AML exhibited a significantly higher overall frequency of FLT3 mutations, encompassing the majority of non-canonical variants. In contrast, ALL displayed a lower overall FLT3 mutational rate but harbored the highest proportion of NCPM), ranging from 58.3 to 59.2%, compared to only 11.1% in AML [18, 57] (Fig. 3). The most common non-canonical mutations in the pediatric cohort were N676K/S, A680V, L576P, and V592 in B-ALL and N676K, E598inframe_insertion, and S451F in T-ALL (Fig. 2 panel 1) [59]. Pediatric, Adolescent and Young Adult and adult Philadelphia (BCR-ABL1) negative (Ph-) B-ALL without recurrent fusion genes exhibited a higher prevalence of JM-PM and non-D835/836 TKD mutations, and additional TKD variants (M837del, P857S, Y842N, N676K and p.837_838delMSinsVQG) [62]. K623I and M837K mutations were detected for the first time in ALL patients, but the specific biological effects must be further investigated [10].

Fig. 3.

FLT3 mutations in AML and ALL patients. Frequency of canonical and non-canonical FLT3 mutations (left) and non-canonical mutation domain distribution details (right). TKD: tyrosine kinase domain; ITD: internal tandem duplication; Ig-like domain: immunoglobulin-like domain; TMD: transmembrane domain; JMD: juxtamembrane domain; TKD1: tyrosine kinase domain-1; TKD2: tyrosine kinase domain-2 [18]

Regarding FLT3 INDEL mutations, 5 FLT3-JM-in-frame deletions between residues 574 and 597 [10] and two FLT3-TKD-in-frame deletions at amino acid 837 [62] were detected in B-ALL. Wider FLT3 deletions were found in 6 pediatric B-ALL cases (3 iAMP21, 1 hyperdiploid, 1 B-other and 1 DUX4-r) and 3 pediatric T-ALL (2 BCL11B and 1 TLX3 subtypes) [59]. A first indication of a germline FLT3 mutation in ALL comes from a hyperdiploid pediatric case carrying the FLT3 Y842C mutation, a recognized AML somatic activating mutation hotspot locus in the kinase domain activation loop [67, 68].

Several non-canonical mutations are activating variants associated with increased phosphorylation activity and oncogenic signaling, including the NCPM-RPM N676K/S, N841, D839, A680V, V592A/D/G, S574G, V579A, and F594L which promoted downstream STAT5 phosphorylation, similar to canonical TKD-mut [10, 13, 18, 53] (Table S2). Furthermore, activating FLT3-JMD PMs showed increased sensitivity to multiple FLT3i (gilteritinib, sorafenib and quizartinib) and importantly, a higher sensitivity to gilteritinib compared to FLT3-ITD cases, probably due to a restrict domain motion [53]. Even non-canonical deletions at the JMD level showed an activation pattern similar to that caused by FLT3-ITD, with a constitutive activation of AKT, ERK1/2 and STAT5 [69]. Additionally, the TKD D835Y, D839G, N841I, Y842N, G846D and the JM Y572C mutations (Table S2) were shown to induce constitutive phosphorylation of the FLT3 protein, resulting in cellular transformation and sensitivity to FLT3i, like sorafenib, quizartinib and midostaurin [13, 18]. Conversely, Y589D, despite its critical location as a phosphorylation site, showed no transformative ability in vitro (Table S2) [13]. In silico analyses predicted a “deleterious” risk for additional FLT3-JM-PM (E573G, Q575P, V579G, Q580P, G583S, Y589D, Y599C) and FLT3-TKD-PM (A627T) mutations, while biological information is still lacking for a number of alterations reported in the literature [10].

An additional mechanism of FLT3 deregulation is represented by t(13q12;v) translocations (Fig. 2 panel 2), which have been rarely described in patients affected by lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (mainly T cell type), myeloid sarcoma, chronic eosinophilic leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) [70, 71]. ETV6::FLT3 was the most frequent rearrangement, occurring between ETV6 exons 1–6 and FLT3 exons 14–24 and preserving the included FLT3-TKD. The rearrangements led to ligand-independent FLT3 oligomerization and downstream pathway activation [71]. Six patients, with different hematological neoplasms, treated with the FLT3i sunitinib or sorafenib showed a spectrum of responses, from rapid hematological and cytogenetic responses with long-term remissions to treatment resistance due to acquired mutations or severe bone marrow suppression [72–77].

These findings underscore the growing complexity of FLT3 mutational landscapes beyond canonical alterations, particularly in ALL. While some non-canonical mutations behave as activating mutations, exhibit oncogenic potential and provide sensitivity to FLT3i, some of them do not induce a constitutive activation or even induce inactivation. Moreover, a number of alterations remain biologically uncharacterized, highlighting the need for further functional studies.

Novel mechanisms of FLT3 dysregulation

Although mutations are the established leukemogenic alterations of FLT3, the gene is frequently overexpressed in AML and ALL [67]. Several transcription factors, including PBXs, CEBPA, HOXA9, MEIS1, MYB, PU.1, BCL11A, PAX5 and PBX3/MEIS1 and MEIS1/PBXs/HOXA9 complexes regulate FLT3 expression (Fig. 4) [29, 30, 78–87].

Fig. 4.

FLT3 transcriptional regulation in AL. Transcriptional activators promote FLT3 transcription (green), whereas repressors inhibit its transcription (red)

In AML and ALL, the abnormal expression of HOXA9, a proto-oncogene that directly regulates FLT3 and influences patient survival and treatment response, is associated with unfavourable outcomes [88]. Moreover, in KMT2A-r AML, enhanced expression of the HOXA9/MEIS1 target SCUBE1 has been recently linked with the amplification of FLT3 signaling by facilitating the activation of downstream LYN-AKT pathways, crucial for leukemic cell survival and proliferation [89]. The myeloblastosis oncogene MYB regulates FLT3 mRNA levels in T-ALL, AML, and CML [80]. In AML, MYB functionally cooperates with CEBPA to modulate FLT3 transcription [29]. A similar interplay can be hypothesized in ALL, since CEBPA and FLT3, are co-expressed in common lymphoid progenitors and pre/pro-B cells and contribute to subgroup stratification as reported below [90]. PAX5, a gene frequently targeted by genomic lesions in ALL, plays a critical role in B-cell commitment and differentiation [91, 92]. Under physiological conditions, PAX5 is a direct repressor of FLT3 transcription and its heterozygous deletion in pro-B cells induced FLT3 upregulation, suggesting a potential link between PAX5 deletions in B-ALL and FLT3 overexpression [93, 94]. HES1 also binds the promoter region of the FLT3 gene repressing its transcription in AML [95].

About 70% of AML cases show FLT3 upregulation, often correlating with high phosphorylation levels and pathway activation that drive proliferation and survival even in the absence of mutations [34, 45, 96]. Evidence suggests that FLT3 overexpression is predictive of shorter OS and increased relapse rates, independently of the mutational status [97]. Of note, FLT3 expression levels do not differ between mutated and wt AML [98].

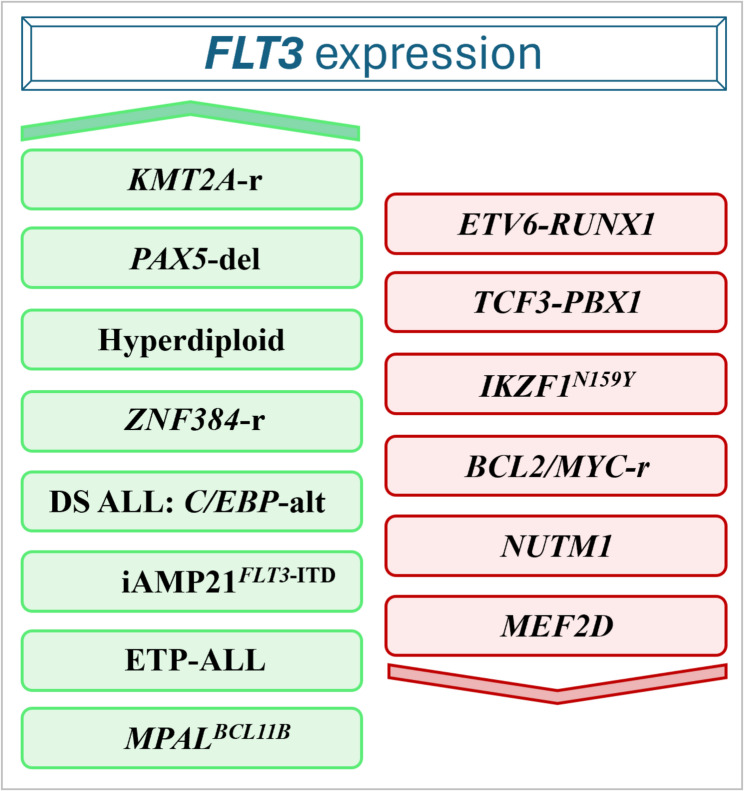

In B-ALL, FLT3 expression was detected in the majority of pediatric and adult patients, with some differences across different molecular subtypes (Fig. 5) [19]. A lower FLT3 expression was found in NUTM1, BCL2/MYC, and IKZF1-N159Y cases while the highest expression levels characterized hyperdiploid, ZNF384-r and KMT2A-r patients with and without FLT3 mutations [19, 21]. Interestingly, FLT3 expression correlates with the B-cell differentiation stage, being higher in immature ALL subtypes (such as KMT2A-r and ZNF384-r) and lower in more mature subtypes, including ETV6::RUNX1, TCF3::PBX1, and MEF2D-r [19]. Moreover, combined CEBPA/FLT3 expression defines a subgroup within pediatric DUX4-r and KMT2A-r cases with potential clinical implications [59]. The pediatric iAMP21 subgroup was significantly enriched in FLT3-ITD and FLT3-highly expressing cases compared with B-other samples (50% vs. 10.7%). Cases with co-occurrence of FLT3 aberrations and SH2B3 lesions showed the highest sensitivity to the FLT3i gilteritinib [99]. In Down Syndrome pediatric ALL (DS-ALL), the C/EBP-alt subgroup, one of the most represented subtypes (10.5% vs. 0.1% in non-DS-ALL), exhibited a high frequency of FLT3 point mutation in TKD2 or insertion/deletion in JMD, mainly at V579 codon, along with elevated FLT3 expression, regardless of FLT3 mutational status [100].

Fig. 5.

Schematic overview of AL subtypes exhibiting differential FLT3 expression patterns (upregulation is indicated in green and downregulation in red)

In T-ALL, patients classified as ETP-ALL showed higher FLT3 expression compared with non-ETP cases (Fig. 5). Moreover, activating FLT3 mutations were mainly found in this T-ALL subgroup, highlighting a role for aberrant FLT3 signaling in ETP-ALL [101].

In ambiguous stem cell leukemias [most commonly myeloid and either T- or B-lymphoid lineage as mixed phenotype acute leukemia (MPAL) and ETP-ALL] chromosome rearrangements or focal amplifications involving BCL11B locus cause enhancer hijacking and consequent aberrant BCL11B activation (Fig. 5), that was associated with FLT3 upregulation regardless of the presence of FLT3 genomic alterations, which are however present in 80% of cases [20]. BCL11B-activated/FLT3-mutated preclinical T/myeloid MPAL and one acute undifferentiated leukemia patients-derived xenograft (PDX) cells resulted highly sensitive to the combination of gilteritinib and the BCL2i venetoclax [102].

FLT3 is an interesting therapeutic target in ZNF384-r B-ALL, representing 1–6% and 10–15% of pediatric and adult cases, respectively [24, 103, 104]. ZNF384 encodes a C2H2-type zinc finger protein, widely expressed in almost all ALL subtypes, that functions as a transcription factor, activating FLT3 [19]. ZNF384 chimeric proteins activate FLT3 transcription by binding to a unique enhancer region upstream of the FLT3 gene (z-FLT3), activating it through histone modifications, altering chromatin structure and recruiting RNA polymerase II (Fig. 2 panel 3). Notably, FLT3 silencing in ZNF384-r cells resulted in reduced cell viability [19] and FLT3i were effective against in vivo models of ZNF384-r ALL [19, 94].

Emerging evidence has revealed two previously unrecognized mechanisms underlying FLT3 overexpression in B-ALL, both implicating the FLT3 locus and adjacent genes. Specifically, these mechanisms involve the formation of read-through (rt) fusion circRNAs and 3D genome alterations.

10% of pediatric cases express the URAD::FLT3 rt-circRNAs. The fusion events occur when exon 1 of URAD, encoding a decarboxylase involved in purine catabolic processes, and exons 16–23 of FLT3, located approximately 11 kb apart on chromosome 13 in the same orientation, undergo a circularization and back-splicing process through read-through transcription (Fig. 2 panel 4). URAD::FLT3 rt-circRNAs were associated with elevated expression levels of both genes and poor prognosis, in terms of central nervous system (CNS) involvement and high relapse rate. Although the functional consequences of circular transcripts and this specific fusion rt-circRNA remain unexplored, their enrichment in high-risk ALL patients suggests a potential role in disease progression and unveils a druggable pathogenic mechanism deserving further investigation [13].

Somatic heterozygous deletions at 13q12.2 between FLT3 and PAN3 genes, immediately 5’ to the FLT3 promoter, disrupt the boundaries of two neighboring topologically associated domains (TAD) and lead to the aberrant interaction between the preserved FLT3 promoter and a distal enhancer that is physiologically insulated into a separate TAD, that drives FLT3 overexpression in B-ALL (Fig. 2 panel 5) [21]. A different 13q12.2 focal deletion involving the FLT3::PAN3 locus has been reported in the CDX2/UBTF B-ALL subtype. In contrast to the above described deletion, the latter removes both FLT3 and PAN3 promoters and induces a chromatin looping mechanism that causes the interaction of the PAN3 enhancer with the CDX2 promoter (~ 30 kb downstream of FLT3). The rearranged cases showed CDX2 upregulation and FLT3/PAN3 downregulation (Fig. 2 panel 6) [22, 23].

Although a possible association with FLT3 regulation was not a goal of recent studies, interestingly, in the same region, circPAN3 have highlighted its pivotal role in mediating drug resistance in AML, regulating autophagy through the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway. The study findings highlight circPAN3 as a potential therapeutic target in AML, but its role in ALL remains unexplored [24].

Overall, the available data suggests that a number of putative cis-regulatory elements can activate FLT3 expression in ALL and AML, because of genomic alterations, fusion genes and transcription factor deregulation. Future studies focused on the identification of the regulatory DNA sequences at this locus are needed to allow a comprehensive understanding of the epigenomic mechanisms regulating FLT3 expression in ALL.

Consequences of FLT3 mutations on the interaction between malignant cells and the leukemia microenvironment

The comprehensive investigation of FLT3 constitutive activation in AML has elucidated its critical role in modulating cytokine and chemokine release and in orchestrating the dynamic interplay between leukemic blasts and the bone marrow microenvironment.

It is well established that AML cells residing within bone marrow niches exhibit increased chemoresistance, largely due to their interactions with stromal cells and the extensive bidirectional exchange of soluble factors, including cytokines and chemokines [105, 106]. Among these, chemokineligand 12 (CXCL12) plays a pivotal role in the bone marrow retention of leukemic blasts via binding to its receptor CXCR4, which is expressed on the surface of AML cells. In the context of FLT3-ITD–mutated AML, multiple biological mechanisms contribute to enhanced bone marrow retention: (i) upregulation of CXCR4 expression [107], (ii) persistent activation of Rho-associated kinase 1 (ROCK1), which regulates actin cytoskeleton dynamics, chemotaxis, and directed migration toward the bone marrow niche [105] and (iii) overexpression of endothelial and platelet selectins (E-SEL and P-SEL), which mediate blast-endothelial interactions [106]. Although these FLT3-driven mechanisms have not been fully characterized in ALL, CXCR4 is similarly implicated in B homing and retention in B-ALL, where its elevated expression correlates with poor prognosis [108]. Based on these insights, therapeutic strategies targeting the CXCR4/CXCL12 axis in combination with chemotherapy or FLT3 inhibitors in AML [108, 109], or with chemotherapy alone in ALL, are under active investigation. In AML, clinical responses to CXCR4/CXCL12 antagonists have been limited, with the notable exception of a single clinical study combining plerixafor and G-CSF with daunorubicin and cytarabine, which demonstrated improved outcomes. However, these results may be confounded by the inclusion of patients with more favorable-risk disease [110]. In pediatric ALL, the combination of CXCR4 inhibition with chemotherapy resulted in modest clinical activity, potentially due to the lack of molecular stratification in the enrolled cohort [111]. These findings highlight the need for future studies to assess the efficacy of CXCR4-targeted approaches specifically in patients harboring FLT3 alterations or dysregulations in downstream signaling pathways [111, 112]. FLT3-ITD mutations also contribute to microenvironmental remodeling by inducing upregulation of miR-155 acting both as a cell intrinsic [82] mechanism and a paracrine mediator through extracellular vesicle [113]. The enrichment of miR-155 in AML-derived EVs has been shown to: (i) enhance myeloproliferative signaling, (ii) suppress type I interferon (IFN)–mediated immune responses, and (iii) promote expansion of FLT3-ITD–positive blasts, collectively fostering a leukemia-permissive microenvironment [114].

Beyond EVs, FLT3-ITD–driven alterations in the bone marrow niche further contribute to therapeutic resistance. In particular, overexpression of the Tec-family tyrosine kinase BMX in FLT3-mutant AML plays a central role in reshaping the stromal landscape. BMX activity enhances the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as CCL5, CXCL1, and CXCL2, thereby strengthening leukemia–stroma interactions [115] and supporting resistance to FLT3 inhibitors. This resistance is further compounded by BMX-mediated STAT5 activation. In addition, both stromal cells and FLT3-ITD AML blasts contribute to the secretion of GM-CSF and IL-3, which reactivate the JAK/STAT5 pathway and enable escape from FLT3i-induced apoptosis [116].

Emerging data also suggest that FLT3-ITD mutations modulate the immune landscape beyond the leukemic compartment. Specifically, conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) derived from FLT3-ITD–mutant progenitors retain the mutation, expand aberrantly, and exhibit a skewed T-bet⁻ cDC2 phenotype [117]. These altered cDCs drive polarization of naïve CD4⁺ T cells toward a Th17 phenotype, leading to elevated IL-17A levels in both murine models and FLT3-ITD AML patients. The resulting pro-inflammatory milieu likely contributes to immune evasion and impaired anti-leukemic immunity.

Although the immunological and microenvironmental consequences of FLT3 mutations have been extensively characterized in AML, corresponding evidence in the context of ALL remains limited. Further mechanistic studies are warranted to elucidate whether analogous processes, such as bone marrow niche remodeling, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance, are similarly driven by FLT3 mutations or alterations in ALL.

FLT3 inhibitors in ALL: from the AML experience to new potential therapeutic strategies in ALL

The growing interest in FLT3 and its role in leukemogenesis has led to the development of various FLT3i developed primarily in AML [118]. These inhibitors, which act on distinct conformations of the FLT3 kinase, have demonstrated clinical benefits, particularly in AML patients harbouring ITD or TKD mutations [45, 119]. FLT3i can be classified into type I or type II inhibitors based on their mechanism of action [62, 118, 120, 121]. Type I inhibitors, including crenolanib, gilteritinib, midostaurin, ponatinib [122], sunitinib, TAK-659 [123], and lestaurtinib bind to the active kinase conformation of FLT3, both near the activation loop and in the ATP-binding pocket, without distinguishing between DFG-in and DFG-out conformations. They are effective against both ITD and TKD mutations since the TKD mutation is only present in the DFG-in conformation, whereas the ITD mutation can occur in both DFG-in and DFG-out conformations [45, 119, 124, 125]. Conversely, type II inhibitors quizartinib, sorafenib and pexidartinib [126] bind to the inactive kinase conformation in a region adjacent to the ATP-binding domain through the hydrophobic pocket formed in the DFG-out conformation. For this reason, they are active only against ITD mutations [45, 119, 124, 125].

FLT3i are also categorized as first- or second-generation based on their specificity. First-generation inhibitors (sunitinib, sorafenib, midostaurin, ponatinib and lestaurtinib), targets multiple RTKs [127, 128], while the second-generation inhibitors quizartinib, gilteritinib and crenolanib, that have been specifically designed to inhibit FLT3, exhibit fewer off-target effects, even if they still inhibit other RTKs [121] (Table S2).

FLT3i typically induce cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase (e.g. through p27KIP1 accumulation by quizartinib) and induction of apoptosis [129–133].

Moreover, gilteritinib, lestaurtinib, quizartinib, and, in some cases, sorafenib promote AML cell differentiation by restoring CEBPA and PU.1 activity, which FLT3 inhibits [134–136]. Building on AML experience, we have identified selective and non-selective FLT3 inhibitors that have been also studied or are under investigation in ALL both at clinical and pre-clinical levels and we here discuss the most recent results obtained in the field (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overview of ALL pre-clinical studies of FLT3 inhibitors

| Inhibitor | Study setting | Sample type | Major findings | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midostaurin | In vitro |

B-ALL AML primary cells |

Infant patients with KMT2A-r ALL responded similarly as FLT3-ITD AML. The response is correlated with the level of FLT3 expression, which is higher in KMT2A-r infant patients. | [137] |

| In vitro and in vivo |

B/T-ALL cell line ALL-PDX |

B-ALL KMT2A-r SEM and AML FLT3-ITD MV4-11 cell lines were the most sensitive to the action of midostaurin as a single agent. The combination of midostaurin and a PAK1 inhibitor (FRAX486) was highly synergistic in the SEM cell line and in a primary T-ALL sample with the FLT3 D835H mutation. Midostaurin alone reduced in vivo leukemia growth, which was further decreased by the combination. | [138] | |

| Gilteritinib | In vitro and in vivo |

B/T ALL cell lines ALL primary cells ALL PDX |

Among the tested cell lines, SEM and JIH-5 (B-ALL ZNF384-r) displayed the highest sensitivity among tested cell lines, with LC50 (lethal concentration) of 44nM and 3.9nM, respectively. Ex vivo ZNF384-r and DUX4-r ALL showed the best response. In vivo, gilteritinib was effective against a xenograft model of JIH-5 and an ALL PDX. | [19] |

| In vitro and in vivo |

B-ALL cell lines B-ALL PDX |

The combination of gilteritinib and ruxolitinib increased cell death of B-ALL Ph-like MUTZ-5 and MHH-CALL-4 cell line models and was effective in PDX mice. | [139] | |

| Quizartinib | In vitro | B-ALL primary cells | Quizartinib significantly inhibited B-ALL cell proliferation, with a greater effect in FLT3-mut cases. | [62] |

| In vitro and in vivo | T-ALL PDX | PDX models from T-ALL cases carrying PRC2 complex mutations and high FLT3 expression were sensitive to quizartinib. | [140] | |

| In vitro | B-ALL cell lines | Quizartinib reduced the confluence of SEM cells as single agent. The combination with RAD001 (mTORi), or MK2206 (AKTi) or the triplet further reduced the cell confluence. | [141] | |

| In vitro | B-ALL cell line | In the SEM cell line, quizartinib decreased the levels of SAMHD1 and hENT1 transcripts and SAMHD1 phosphorylation. | [142] | |

| Crenolanib | In vitro | B-ALL primary cells | Crenolanib reduced the percentage of proliferating B-ALL FLT3-mut cells. | [62] |

| In vitro and in vivo |

B-ALL cell lines B-ALL PDX |

B-ALL KMT2A-r and RS4;11 resistant cell lines to dexamethasone with acquired FLT3 mutation were more sensitive to crenolanib compared to the parental RS4;11 cell line and to B-ALL DUX4-r NALM-6 and B-ALL TCF3-PBX1 697 resistant cell lines, which do not have FLT3 mutations. Crenolanib delayed the engraftment of RS4;11/FLT3-mut cells in the xenograft model. | [143] | |

| Sorafenib | In vitro | B/T cell lines | Sorafenib was tested at concentrations of 7.3 µM and 0.73 µM on the SEM, RS4;11, and T-ALL JURKAT cell lines. While all three cell lines responded to the 7.3 µM dose, only the SEM cells were sensitive at 0.73 µM. | [144] |

| In vitro and in vivo | T-ALL PDXL | PDX models from T-ALL cases carrying PRC2 complex mutations and high FLT3 expression were sensitive to sorafenib. | [140] | |

| Sunitinib | In vitro and in vivo |

B-ALL cell lines B-ALL PDX |

The SEM cell line was more sensitive to sunitinib compared with NALM-6. The combination of sunitinib and venetoclax was effective in both SEM and PDX models of KMT2A-r B-ALL. | [145] |

| Ponatinib | In vitro | B-ALL cell lines | The combination of ponatinib and venetoclax showed synergy in the Ph+ SUB-B15 cell line and in a primary sample of Ph+ of B-ALL. In the SUP-B15, the treatment combination induced an increase of the pro-apoptotic protein BIM, along with a downregulation of LYN and STAT5. | [146] |

| Lestaurtinib | In vitro | B/T ALL cell lines | Lestaurtinib was highly effective in cell lines expressing high levels of FLT3, with the HB-1119, SEM-K2, and B1 B-ALL KMT2A-r cell line models displaying the highest sensitivity. Ex vivo tests on primary samples from pediatric patients confirmed a greater efficacy against FLT3 upregulated cells. | [147] |

| TAK-659 | In vivo | B-ALL PDX | TAK-659 reduced CD45 + cell burden in the mice treated with TAK-659 compared to controls and delayed leukemia progression in 6 out of 8 PDX models. | [148] |

Midostaurin

Midostaurin (PKC412) was the first FLT3i approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicine Agency (EMA) in 2017 for the treatment of newly-diagnosed AML with FLT3 mutations. The approval was based on the results of the phase III RATIFY study on AML patients younger than 60 years: the addition of midostaurin to chemotherapy prolonged OS from 25.6 to 74.7 months, with a 4-year OS of 51.4% and 44.3% and event-free survival (EFS) of 28.2% in the midostaurin vs. the placebo arm [149]. Of note, the RATIFY trial data revealed that the efficacy of midostaurin varies according to the insertion site of the ITD mutation [150]. Patients harbouring the ITD in the JM domain (70% of FLT3-ITD cases) obtained the greatest benefit from the combined treatment. Conversely, no clinical advantage of midostaurin addition was observed in patients with FLT3-ITD located in the TKD or with mixed JM/TKD insertions). The molecular mechanisms response for the poor response in the latter patient population deserve further investigation.

Pediatric (non-infant) KMT2A-r ALL and FLT3-ITD AML showed similar ex vivo responses to midostaurin, with higher FLT3 expression associated with increased sensitivity. Conversely, infant KMT2A-r and pediatric FLT3-low patients showed no detectable FLT3 phosphorylation, and no response to midostaurin [137]. Based on these results, a phase I/II trial (#NCT00866281, clinicaltrials.gov) evaluated the efficacy of midostaurin single agent in relapsed/refractory (R/R) pediatric KMT2A-r ALL or FLT3-mutated AML. Clinical response rates were 56% in AML and 23% in ALL, with a median OS of 3.7 and 1.4 months, respectively. The study demonstrated a limited activity of midostaurin monotherapy, although the results may be revised in light of post-enrollment molecular analyses [151].

Preclinical studies reported a synergic activity of midostaurin and FRAX486, an inhibitor of p21-activated kinases (PAK), PAK1 and PAK2, in the KMT2A-r FLT3-high SEM B-ALL cell line and inFLT3D835H primary cells, both in vitro and in vivo [138]. Moreover, midostaurin reduced leukemia engraftment and improved the survival of a FLT3D835H PDX B-ALL model and SEM cell line.

Gilteritinib

Gilteritinib (ASP2215) is a pyrazinecarboxamide derivative and induces apoptosis in cells carrying FLT3-ITD, and the TKD D835Y mutation, and F691 mutations, the latter inducing resistance to quizartinib [25].

Gilteritinib has been approved by FDA and EMA as monotherapy treatment in adults with R/R FLT3-mut AML based on the results of the phase III ADMIRAL trial. Patients receiving gilteritinib showed a complete remission/complete remission with incomplete count recovery (CR/CRi) rate of 34%, compared with 15% of those treated with standard salvage therapies [121].

Among a panel of B- and T-ALL models, the KMT2A-r SEM and the ZNF384-r JIH-5 cells displayed the highest sensitivity, that was confirmed ex vivo on ZNF384-r primary cases and in ZNF384-r ALL PDX and JIH-5 xenograft models [19]. DUX4-r ALL also showed a promising ex vivo response to the drug [19].

Gilteritinib also showed a promising activity against Philadephia-like (Ph-like) B-ALL as single agent and in combination with the JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib. The addition of gilteritinib to ruxolitinib increased cell death in MHH-CALL-4 and MUTZ-5 models from 20–30–60%, as confirmed in a PDX model of IGH::CRLF2 B-ALL by reduction of spleen weight blasts infiltrate [139].

Moreover, gilteritinb displayed clinical activity in T-ALL and MPAL. An ETP-ALL patient relapsed to multiple chemotherapy regimens and haploidentical donor stem cell transplant with FLT3-TKD mutation achieved CR with MRD negative status after 4 weeks of venetoclax and gilteritinib combination, followed by 5 weeks of gilteritinib monotherapy (due to venetoclax-based toxicity). The response was maintained for 8 months before relapse, which was induced by a FLT3-wt clone [152].

Similarly, in a 55-year-old FLT3-ITD MPAL patient, fourth line gilteritinib treatment (4 months) followed by two cycles of gilteritinib/azacitidine combination induced a CRi that was maintained for 8 months. Of note, the patient had previously failed a second line therapy with midostaurin in combination with methotrexate and cytarabine [153].

The combination of gilteritinib and venetoclax [154] and the triplet gilteritinib, venetoclax and azacitidine are under clinical investigation in R/R FLT3-mut AML with the aim of improving the clinical response [155, 156], along with a novel dual FLT3/BCL-2 inhibitors in adult R/R AML (#NCT03625505) [154, 157]. Recent data obtained in BCL11B-activated lineage ambiguous leukemia and from in vitro study, suggested that the synergy between venetoclax and gilteritinib originates from prolonged inhibition of proliferation and survival signals [158]. Gilteritinib blocks oncogenic signaling pathways as the MAPK one and reduces MCL1 expression, while venetoclax promotes the release of BIM from protective complexes with BCL2, thereby facilitating the activation of the apoptotic mediators BAX and BAK. These synergistic effects, which prevent the restoration of survival signals and counteract MCL1-mediated resistance, prove particularly effective even in patients with unfavorable molecular profiles [159–161].

Quizartinib

Quizartinib (AC220) is a benzothiazole-phenyl urea derivative and was the first drug selectively developed to target FLT3, proving effective against both FLT3-wt and FLT3-ITD. Quizartinib has been approved in Japan as monotherapy for R/R FLT3-ITD AML in 2019 based on results of the QuANTUM-R study (#NCT02039726). The drug improved OS from 4.7 months in the chemotherapy arm to 6.2 months [162]. However, despite an initial clinical response, a fraction of patients became resistant by acquiring TKD mutations (D835Y, D835V, and D835F), alone or in combination with the F691L alteration (#NCT00989261) [25, 163]. FDA and EMA approved in 2023 the combination of quizartinib and chemotherapy for the treatment of newly-diagnosed adult FLT3-ITD AML [164, 165], based on the results of the QuANTUM-First study (#NCT02668653). Quizartinib administration following 3 + 7 chemotherapy extended the median OS to 31.9 months compared to 15.1 months in the chemotherapy/placebo arm [166].

The phase II QUIWI (#NCT04107727) trial also suggested a potential efficacy of quizartinib in addition to chemotherapy newly-diagnosed FLT3-ITD-negative (KMT2A-r negative) AML, with an EFS of 18.8 months compared with 9.9 months of the placebo arm [167]. A FLT3-like gene expression signature [168, 169] identified a subset of patients who gained significant benefit from quizartinib combination as a potential biomarker of response [168]. In addition, the transcriptomic analysis of patients maintaining the most durable response revealed a strong downregulation of heat shock protein genes in the FLT3-ITD negative long-responder, suggesting their potential role in quizartinib response [170]. Overall, these results highlight the potential of using the FLT3-like signature as a biomarker to select FLT3-wt AML patients who may respond favourably to quizartinib, offering valuable insights for personalized AML treatment. To confirm these results, the phase III QuANTUM-WILD trial (#NCT06578247) is being initiated [171].

In pediatric patients, the combination of quizartinib and cytarabine/etoposide was not as successful as in the adult population. In a phase I study (#NCT01411267) on 22 AML or KMT2A-r or hyperdiploidy ALL patients at first relapse, aged 1 month to 21 years, the overall response rate (ORR) was 43% in FLT3-ITD AML vs. 14% in FLT3-wt patients, while no response was obtained in KMT2A-r ALL [172].

Moreover, the clinical results did not confirm the preclinical data demonstrating a good response of the SEM cell line [142] and of FLT3-ITD or FLT3-TKD primary Ph- B-ALL cells [62] to quizartinib single agent. Adjusted treatment schedules (e.g. sequential drug administration) and novel combinations (e.g. with AKT and mTOR inhibitors, according to preclinical data) [141] may open new quizartinib-based therapeutic opportunities. Currently, the combination of quizartinib and venetoclax is under investigation in a phase I trial in R/R AML harbouring FLT3-ITD mutations (#NCT03735875).

Crenolanib

Crenolanib (CP-868596) is a quinoline derivative. In AML it induced a CR rate of 23% in R/R patients not previously treated with FLT3i, with a median OS of 55 weeks, while a CR rate of 5%, with a median OS of 13 weeks was achieved in patients previously treated with FLT3i (phase II trial #NCT01657682). When focusing on FLT3-mut AML at relapse, crenolanib achieved a combined CR/CRi rate of 50% in patients who had not previously received FLT3i and a CR + PR rate of 28% in patients with prior FLT3i treatment (phase II study #NCT01522469) [173].

The combination of crenolanib with cytarabine/anthracycline induced an overall CR rate of 86% and a median OS of 20.2 months in AML (phase II study #NCT02283177) [174].

Crenolanib is also effective in treating AML patients that carry FLT3 mutations conferring resistance to quizartinib, such as D835 [175, 176]. However, NRAS, IDH1, IDH2, TET2, TP53 and other FLT3 mutations have been associated with crenolanib resistance [177].

Currently, no clinical trials have been conducted in ALL. Few information available from preclinical studies suggests a reduction of cell proliferation in crenolanib-treated Ph- B-ALL cells [62] and a delayed leukemia engraftment in a xenograft models of dexamethasone-resistant RS4;11 B-ALL. Of note, dexamethasone resistance was associated enrichment of transcriptional programs related to kinase signaling pathways, strong FLT3 phosphorylation and expression of the mature, glycosylated FLT3 form [143].

Sorafenib

Sorafenib (Bay 43-9006) is a diaryl-urea, originally designed as a MAP kinase pathway inhibitor that has been used in various tumors types due to its ability to inhibit RET, KIT, VEGFR, PDGFR in addition to FLT3 [19].

Sorafenib exerts significant anti-proliferative effects in AML cell lines or ex vivo models, particularly in FLT3-ITD mutated cases [162]. However, it did not obtain approval due to the lack of convincing clinical benefit. Indeed, in the phase II SORAML study (#NCT00893373), the addition of sorafenib to chemotherapy in the treatment of newly-diagnosed AML patients failed to prolong 5-year OS, despite an improved EFS (41% vs. 27%) and RFS, 53% vs. 36% [178]. These data were confirmed by the phase II ALLG AMLM16 study that showed a better response in patients with high FLT3-ITD expression [179].

A recently report showed a durable response (1 year of CR) of a Ph+ therapy-related ALL patient carrying FLT3Y572C and FLT3I836delI variants to decitabine, imatinib, and sorafenib addition, after failure of one week of dexamethasone, vindesine and imatinib regimen [180].

Sorafenib showed a promising activity in wt AML and ALL patients with refractory CNS leukemia (phase II #ChiCTR2100048055 study): the 6 ALL patients, including FLT3-ITD and FLT3-wt cases achieved CR, and with a median follow-up time of 20.1 months, 5 of them were alive [181].

These data, along with the lower target specificity of the drug, suggest that sorafenib may open a therapeutic window also in FLT3-wt patients. Indeed, in combination with conventional salvage chemotherapy, sorafenib induced 26/43 and 5/43 partial response (PR) in FLT3-wt AML and ALL patients relapsed after allogeneic transplantation (allo-HSCT), with a 2-year OS of 44.2% and EFS of 30.2% [182].

Moreover, mutations in PRC2 complex genes (e.g. EZH2), that are common in T-ALL and in particular in ETP-ALL, unveiled a selective vulnerability to FLT3 inhibition by sorafenib or quizartinib, driven by their positive regulation of FLT3 expression, resulting in activation of the downstream signaling pathways [140]. In vitro studies also suggested potential synergic combinations of sorafenib with cytarabine, doxorubicin and everolimus in FLT3-wt KMT2A-r B-ALL SEM and RS4;11 models ad in the T-ALL JURKAT cells [144].

Sunitinib

Sunitinib (SU 11248) is an indole pyrrole approved for the treatment of metastatic renal carcinoma and advanced forms of gastrointestinal stromal Tumor resistant to imatinib. In the AMLSG 10− 07 phase I/II study (#NCT00783653), the combination of cytarabine/daunorubicin chemotherapy with sunitinib induced 59% CR/CRi in newly-diagnosed FLT3-ITD or FLT3-TKD AML patients of patients, (57% of FLT3-ITD and 62% of FLT3-TKD). For 17/22 patients, the median OS was 1.6 years. However, 41% of patients relapsed by FLT3F691L, FLT3Y842C, FLT3D835V, FLT3D835Y mechanisms, that need to be further elucidated [183].

In ALL, in vitro studies suggest an activity of sunitinib against FLT3-high cells. Sunitinib administration following with the pro-apoptotic synthetic peptide BIM-BH3, was more effective on KMT2A-r SEM cells that express high FLT3 levels, compared with NALM-6 (DUX4-r, B-ALL), that were characterized by BIM-mediated upregulation of the anti-apoptotic proteins MCL1 and BCL2. Moreover, the combination of sunitinib and venetoclax further improved cytotoxicity in SEM cells and in PDX models of KMT2A-r B-ALL [145]. Accordingly, sunitinib provided a clinical benefit to a ZNF384-r FLT3-high B-ALL patient relapsed after transplantation and several chemotherapy lines [94]. The treatment induced a clinical response bridging the patient to a second allo-HSCT, that granted a CR longer than 4 years [94].

Ponatinib

Ponatinib (AP24534) is an imidazo-pyridazine derivative targeting multiple TKs and approved for the treatment of Ph+ ALL and CML [47], able to target leukemic cells carrying the BCR-ABL1T315I mutation [184]. Ponatinib also potentiates the activity of venetoclax against the BCR-ABL1 SUP-B15 B-ALL cell line and primary B-ALL samples, by increasing the levels of pro-apoptotic protein BIM and reducing the phosphorylation of the CRKL and LYN kinases [146]. Despite being primarily active on other kinases [47, 185, 186], ponatinib inhibited the proliferation of FLT3-ITD Ba/F3 cells [187] and demonstrated a similar efficacy to sorafenib and sunitinib against the FLT3-ITD MV4-11 AML cell line [186].

However, ponatinib failed to demonstrate clinical efficacy in the phase II PONALLO study (#NCT03690115) on AML patients that had previously received another FLT3i (22 out of 23). Indeed, 50% of the patients experienced relapse after ponatinib treatment [188].

Given its broad activity, ponatinib has attracted much interest also in the Ph- B-ALL subgroups, including the high-risk Ph-like cohort, with encouraging results [189] and a number of clinical trials investigating the efficacy of ponatinib in ALL are ongoing (#NCT05268003, #NCT04688983, #NCT04475731, #NCT06207123, #NCT05306301). However, the relationship between FLT3 expression or mutational status and response to Ponatinib need further investigation in this setting.

FLT3F691I and FLT3F691L mutations are known to confer strong resistance to quizartinib. While ponatinib retains some activity against FLT3F691-mutated leukemia, its efficacy is reduced, particularly when these mutations co-occur with FLT3-ITD or FLT3D835. Additional studies are required to determine whether ponatinib can effectively overcome resistance in specific clinical settings [187].

Lestaurtinib

Lestaurtinib (CEP-701) is an indocarbazole derivative initially developed as a NTRK1i [47]. Based on preclinical results showing a promising drug activity against FLT3-high KMT2A-r B-ALL cell lines [147], the phase III AALL0631 study (#NCT00557193) evaluated its combination with chemotherapy at post induction. However, lestaurtinib addition did not improve EFS (36% vs. 39%) and 3 year OS (45% vs. 46%) of KMT2A-r infant ALL patients aged less than one year [190]. A fraction of patients characterized by 85% reduction of FLT3 phosphorylation by FLT3i plasma inhibitory assay and ex vivo blasts sensitivity to lestaurtinib achieved a 3-year EFS of 88%, with an OS of 94% [190], suggesting that the drug may provide a clinical benefit in selected patient cohorts.

Pexidartinib

Pexidartinib (PLX3397) is an oral drug specifically developed for the treatment of tenosynovial giant cell tumor (TGCT), as a potent Colony Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor (CSF1R) inhibitor [191]. The drug also demonstrated an antagonistic activity against KIT and FLT3-ITD [192]. In the phase I/II #NCT01349049 clinical trial on FLT3-ITD R/R AML that had previously received other FLT3i-based regimens, pedixartinib achieved an ORR of 21%, which is lower compared with quizartinib and gilteritinib responses (CR rate of 40% and 50%, respectively, in similar populations). While preclinical studies showed pexidartinib activity against FLT3F691L, clinical trials reported limited responses in patients. This suggests that in vitro sensitivity may not always predict clinical efficacy, highlighting the need for better biomarkers of response. A phase I clinical trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of pexidartinib in R/R AML and ALL, independently of FLT3 status, is ongoing (#NCT02390752) [193].

BMF-500

BMF-500 is an oral FLT3i with no activity against KIT. The phase I Covalent-103 (#NCT05918692) clinical trial is currently evaluating its safety, tolerability, and efficacy in R/R AML (that have previously received another FLT3i), R/R ALL and R/R MPAL either FLT3-mut or wt [194].

TAK-659

TAK-659 (mivavotinib) is a reversible FLT3 and spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK) inhibitor. In AML, SYK activated FLT3 through direct binding and its inhibition sensitizes FLT3-ITD AML cells to FLT3i. In a phase Ib trial in relapsed/refractory AML, TAK-659 demonstrated modest clinical activity. Objective responses were observed exclusively in patients harboring FLT3-ITD mutations, whereas no responses were detected among those with FLT3-TKD mutations or FLT3-wt status, as determined by central laboratory testing. Nevertheless, 21 of the 33 evaluable patients with FLT3-wt disease demonstrated peripheral blast reductions of ≥ 50%, indicating biological activity [123]. In ALL pediatric PDX models representative of KMT2A-r, B-ALL and Ph-like subtypes and were FLT3 and SYK expression was assessed to be significantly higher in B-ALL than in T-ALL, TAK-659 was well tolerated and delayed leukemia progression, but was not able to induce remission [148].

Personalized medicine approaches based on FLT3 inhibitors in acute leukemias: dream or reality?

Given the established driver role of FLT3 mutations (at least in AML), and our increasing knowledge on resistant mechanisms mediated by on-target lesions, the development of novel FLT3i with diverse specificities is a very active field [132]. However, a huge effort is still needed to address the potential efficacy of the different inhibitors against the increasing list of non-canonical mutations, and of emerging FLT3 direct or indirect alterations (Fig. 2) along with the interaction between other genetic drivers and FLT3 expression in determining sensitivity to them.

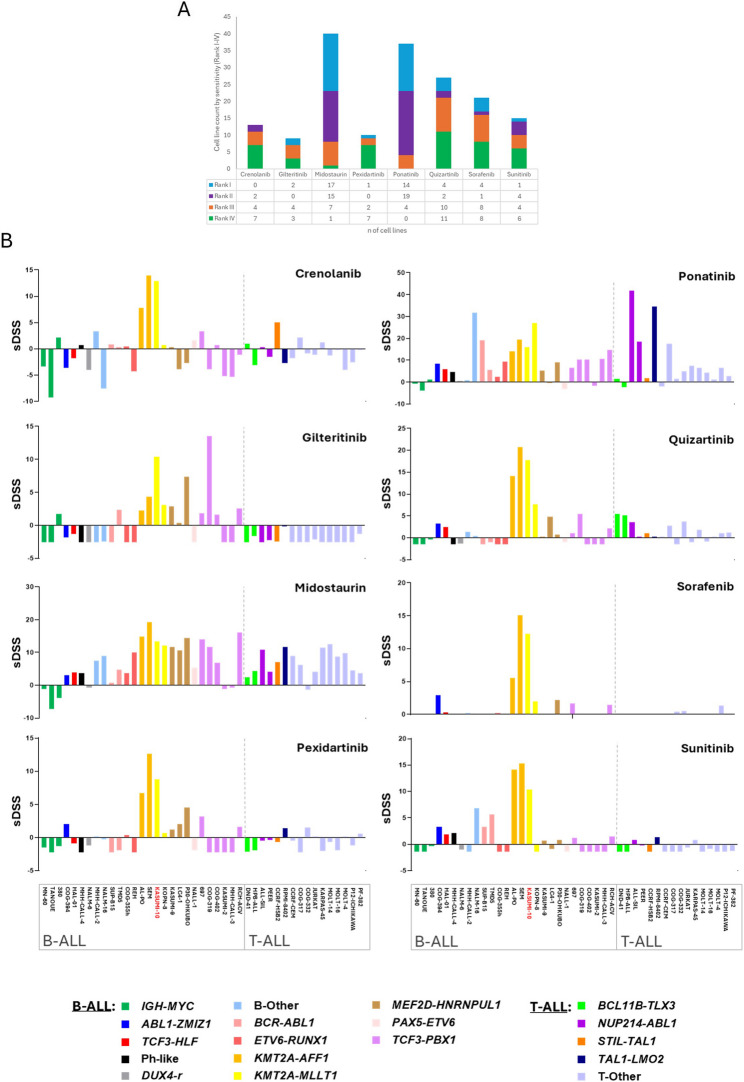

Recently, the response data of 43 pediatric/AYA ALL cell lines representative of 18 B- and T-ALL subtypes, to 8 FLT3i (crenolanib, gilteritinib, midostaurin, pexidartinib, ponatinib, quizartinib, sorafenib, and sunitinib, Table S2) have been released in the Functional Omics Resource of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (FORALL) web-portal [195, 196].

According to drug sensitivity scores (sDSS), midostaurin and ponatinib were among the top scoring drugs in most cell lines, while gilteritinib and pexidartinib displayed the lowest efficacy (Fig. 6A). The reported sensitivity to FLT3i varies across different experimental settings. While gilteritinib showed low efficacy in some drug screening panels, it was effective in specific xenograft models of ALL, as said before. This suggests that drug response may be context-dependent, possibly influenced by additional genetic or epigenetic factors. Future studies should aim to define predictive biomarkers for FLT3i sensitivity in ALL.

Fig. 6.

Drug sensitivity profiling of 43 pediatric and adolescent/young adult (AYA) ALL cell Lines exposed to 8 different FLT3 inhibitors. A. Each cell line was ranked from 1 (most sensitive) to 8 (least sensitive) for each compound, based on its drug sensitivity score (sDSS), a quantitative metric that integrates potency and efficacy (https://proteomics.se/forall/). The bar chart shows the distribution of the top four ranked drugs across all cell lines, categorized as follows: Rank I (light blue), Rank II (purple), Rank III (orange), and Rank IV (green). Drugs most frequently ranked in the top positions (e.g., midostaurin and ponatinib) are indicative of broader efficacy across diverse ALL subtypes, whereas those with fewer top ranks (e.g., gilteritinib and pexidartinib) exhibited limited activity. B. Selective Drug Sensitivity Score (sDSS) of individual FLT3 inhibitors across B- and T-ALL cell lines, grouped accordingly and separated by a dashed vertical line. Each bar represents the sDSS for a given cell line treated with a specific FLT3 inhibitor, color-coded by ALL subtypes (as indicated in the legend below). Among the profiled cell lines, KASUMI-10 (highlighted in red) is the only one harboring a known FLT3 mutation. sDSS≥ 8: high sensitivity; 5 ≤ sDSS < 8: intermediate sensitivity; sDSS < 5: resistance. KASUMI-10 (shown in red in the legend) is a FLT3-mut cell line

Midostaurin had a broad activity, ranking among the top inhibitors across diverse leukemia subtypes (e.g. KMT2A-r, TCF3 ::PBX1, MEF2D-r). Ponatinib demonstrated the highest efficacy in T-ALL and KMT2A-r or Ph+ B-ALL subtypes (Fig. 6B). Quizartinib was highly effective in KMT2A-r cell lines but displayed modest activity against T-ALL. Crenolanib, sorafenib, sunitinib and pexidartinib were highly specific for KMT2A-r cell lines (Fig. S3). Gilteritinib was effective against COG-319 (TCF3::PBX1) and KASUMI-10 (KMT2A-r, FLT3-mut). Of note, KASUMI-10 the only FLT3-mutated B-ALL cell line in the cohort, was sensitive to all the drugs tested, and especially to quizartinib, ponatinib and midostaurin (Fig. S3). Nine cell lines (7 B-ALL and 2 T-ALL), were resistant to all FLT3i including one TCF3::PBX1 (KASUMI-2) and 2 IGH ::MYC translocated (MN-60, TANOUE). Nine additional models (4 B-ALL and 5 T-ALL), exhibited limited response (Fig. 6B and Table S2). Regarding molecular subtypes, KMT2A::AFF1 cell lines were highly sensitive to quizartinib and midostaurin while KMT2A::MLLT1 leukemia responded well to quizartinib, and ponatinib (Fig. S3). As expected, ponatinib was the most effective inhibitor for BCR::ABL1 cell lines. ETV6::RUNX1 cells displayed low sensitivity to all inhibitors, with only modest activity observed for ponatinib and sunitinib (Fig. S3). Midostaurin was the most effective inhibitor in MEF2D-r cell lines followed by ponatinib. The T-ALL BCL11B::TLX3 subtype showed moderate sensitivity to quizartinib, while the T-ALL NUP214::ABL1 subtype was sensitive to ponatinib followed by midostaurin (Fig. S3).

The large-scale analysis of response data across diverse B- and T-ALL cell line subtypes reveal novel, very specific and sometimes unexpected FLT3i sensitivity patterns, highlighting their potential beyond AML. However, the complexity of these drug response data clearly suggest that we still lack specific biomarkers for a tailored therapeutic application of FLT3i in ALL. The presence of co-occurring genetic lesions beyond FLT3 mutations, along with other genetic, epigenetic and transcriptional mechanisms of FLT3 dysregulation need to be taken into account in order to explain the diverse sensitivity to FLT3i. Moreover, in light of clinical translation of FLT3i-based therapeutic approaches in ALL, some potential challenges have to be considered, and in particular primary and acquired resistance to FLT3 targeting agents. Clinical experience in AML has uncovered multiple mechanisms of resistance, including enforced signaling through upregulated AXL [197], compensatory lesions within the MAPK pathway [162, 198], which are actually frequent in ALL and also co-occur with FLT3 alterations, and on target FLT3 mutations as the FLT3 D835, which reduces the effectiveness of type II inhibitors [162, 198]. Of note, the FLT3 G846D mutation in the TKD was demonstrated to confer resistance to sorafenib but not to midostaurin in a pediatric ALL cohort [13]. In addition, signaling from the bone marrow stroma through the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis [199] and the E-SEL/E-SEL-L interaction [200] can hamper the efficacy of FLT3i. The expression of the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP3A4 by bone marrow stromal cells has been also identified as a key mechanism of resistance to FLT3 inhibitors such as sorafenib, gilteritinib, and quizartinib, owing to its role in drug metabolism. CYP3A4 activity is largely governed by genetic polymorphisms, which contribute to interindividual variability in drug clearance. One proposed strategy to overcome this resistance mechanism involves the co-administration of CYP3A4 inhibitors, such as clarithromycin, to reduce enzymatic degradation of FLT3 inhibitors. However, this approach carries the risk of excessive systemic drug exposure, potentially resulting in heightened toxicity due to uncontrolled increases in plasma drug concentrations [201].

Taken together, while data on biomarkers of response and resistance to FLT3i in ALL are currently limited, it is conceivable that some mechanisms described in AML may be also relevant in ALL. As the use of FLT3i in ALL increases and new studies are ongoing, it is likely that additional resistance mechanisms will be uncovered, providing a clearer understanding of how to optimize personalized FLT3-targeted therapies in this setting.

Novel therapies targeting FLT3

The development and clinical evaluation of novel small molecules targeting FLT3 remains ongoing, as demonstrated by the phase I trial of the novel FLT3i clifutinib, which induced responses in 40% of R/R AML patients (#NCT04827069) [202].

Among the emerging compounds, momelotinib represents a promising candidate for the treatment of FLT3-ITD leukemias. Already approved by the FDA for the treatment of myelofibrosis [203], momelotinib is distinguished by its dual inhibitory activity against both FLT3 and JAK2. JAK2 activation, triggered by cytokines such as IL-3 and GM-CSF, has been implicated in mediating resistance to FLT3i in AML [203]. Preclinical studies in mutated AML demonstrated that momelotinib significantly suppresses leukemic proliferation in vitro and in vivo, including those resistant to quizartinib [204]. Given its dual targeting of FLT3 and JAK2, momelotinib could also be a valuable therapeutic option in ALL, especially in the Ph-like ALL cases characterized by JAK-STAT pathway activation [205]. Further clinical investigation is warranted to assess its efficacy in this context.

Beyond the use of specific FLT3i, other approaches are also under investigation for targeting aberrant FLT3 expression, including antibodies and chimeric antigen receptors (CAR) T.

An Fc-optimized FLT3 antibody, 4G8-SDIEM, was developed to enhance natural killer (NK) cell-mediated antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) by binding to the CD16a receptor. The antibody induced strong NK cell activation and degranulation, significantly enhancing ADCC in the co-culture of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy donors with FLT3+ SEM or primary B-ALL cells [206].

FLT3CART and CD19xFLT3CART were tested against FLT3-high AML and KMT2A-r ALL. FLT3CART was effective against ALL cells, including pediatric and adult PDX models with high FLT3 expression. CD19xFLT3CART demonstrated enhanced efficacy by reducing antigen escape and promoting cytokine production. The combination of FLT3CART with gilteritinib accelerated the elimination of leukemic ALL and AML cells, improved survival, and increased the number of FLT3CART cells in the peripheral blood of PDX models [207, 208].

These emerging FLT3-targeted therapies, offer promising alternatives to traditional inhibitors, potentially overcoming aberrant FLT3 expression resistance and antigen escape.

Conclusions

For many years, FLT3 has been preferentially studied in AML, becoming an established molecular and diagnostic marker and one of the first targets of tailored therapies. Several FLT3i have been developed over time, with varying degrees of selectivity, and some of them have entered clinical practice for the treatment of FLT3-mut AML. In ALL, FLT3 mutations were identified years ago, but due to the lower prevalence, particularly of canonical FLT3 mutations, the research interest in the field remained limited, with few isolated studies or single cases addressing the functional consequences of FLT3 alterations and inhibition in ALL.

Today, this landscape is rapidly evolving. The advent of NGS technologies has highlighted an increasing frequency of FLT3 mutations in ALL, deserving further attention in the diagnostic workup of the disease to guide tailored therapeutic approaches, mirroring current standard practice in AML. Notably, increasing evidence suggests that FLT3-targeted therapies may hold promise in ALL. Moreover, epigenetic-driven expression, deletions, 3D genomic modifications, and the formation of specific circRNA and fusion-derived circRNAs have uncovered novel mechanisms of FLT3 deregulation and upregulation both in AML and ALL. Although some non-canonical FLT3 mutations have been shown to enhance phosphorylation activity and contribute to leukemic transformation, their overall clinical significance remains unclarified. It is currently unclear whether these mutations confer the same therapeutic vulnerabilities as canonical FLT3-ITD or TKD mutations. Moreover, comprehensive studies on larger patients’ cohorts are required to determine the impact of mutations on disease progression and response to FLT3i.

A big effort is also needed to better understand the pathogenicity of non-canonical mutations, their preferential onset in B-ALL compared with AML, the role of high, still ligand-dependent, FLT3 activity across leukemia subtypes, the mechanisms driving vulnerability to FLT3i in FLT3-wt cells.

As highlighted throughout this review, the impact of FLT3 alterations on therapeutic response and clinical outcome is also modulated by the broader co-occurring genetic landscape, including mutations, gene fusions, and deletions, which warrants comprehensive characterization in both AML and ALL. Of note, while in AML the most frequent co-occurring mutations affect complementary biological processes as transcriptional regulation and DNA methylation, in ALL, mutations targeting different steps of the receptor tyrosine kinase signaling co-occur with FLT3 lesions, thus emphasing the crucial oncogenic role of the pathway in the disease pathogenesis.

To date, the different responses of each cellular model and the specificities of the inhibitors remain unexplained. Predictive biomarkers of drug sensitivity, as recently suggested for the FLT3-like signature, and a more refined understanding of resistance mechanisms are essential for informed therapeutic decision-making and improved clinical outcomes [168, 209].

This knowledge may also provide useful insights to design improved therapeutic combinations able to reduce the development of resistance that currently remains a challenge in the field of FLT3-targeted agents.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ADCC

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

- ALL

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- Allo-HSCT

Allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- A-loop

Activating loop

- alt

Altered

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- AYA

Adolescent and Young Adult

- CAR

Chimeric antigen receptors

- cDC

Conventional dendritic cells

- CDX2

Caudal type homeobox 2

- circRNA

Circular RNA

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CR

Complete remission

- CRi

Complete remission with incomplete count recovery

- DS-ALL

Down syndrome pediatric all

- EFS

Event-free survival

- EMA

European medicine agency

- ETP-ALL

Early t-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- FDA

Food and drug administration

- FL

FLT3 ligand

- FLT3

Fms like Tyrosine Kinase

- i

Inhibitor

- IgG-like

Immunoglobulin-like

- INDEL

Insertion-deletion

- ITD

Internal tandem duplication

- JMD

Juxtamembrane domain

- MDS

Myelodysplastic syndrome

- miR

MicroRNAs

- MPAL

Mixed phenotype acute leukemia

- MRD

Minimal residual disease

- mRNA

Messenger RNA

- NCPM

Non-canonical point mutation

- NGS

Next-Generation Sequencing

- NK

Natural killer

- ORR

Overall response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PAK

P21-activating kinases

- PAN3

Poly(A) specific ribonuclease subunit PAN3

- PDX

Patients-derived xenograft

- Ph

Philadelphia (BCR-ABL1)

- Ph-like

Philadelphia-like

- PM

Point mutations

- PR

Partial response

- R/R

Relapse/refractory

- r

Rearranged

- RFS

Relapse-free survival

- RPM

Recurrent point mutation

- rt-circRNA

Read-through circular RNA

- RTKs

Receptor tyrosine kinase

- TAD

Topologically associated domain

- TKD

Tyrosine kinase domain

- UBTF

Upstream binding transcription factor

- URAD

Ureidoimidazoline (2-Oxo-4-Hydroxy-4-Carboxy-5-) decarboxylase

- WES

Whole-exome sequencing

- wt

Wild-type

- ZNF384