Abstract

Background:

In adults living with HIV, non-invasive biomarkers have been described for the early identification of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver diseases (MASLD). However, this issue remains unexplored in children and young people with vertical HIV (YWVH), among whom MASLD prevalence is around 30%.

Methods:

To identify biomarkers associated with MASLD in YWVH under sustained viral suppression with antiretroviral therapy, we analysed plasma lipid species, plasma bile acid profile, and gut microbiome composition in a cross-sectional cohort of 10 YWVH with MASLD and 19 YWVH without clinical evidence of MASLD (control).

Results:

Here we show that YWVH with MASLD have significantly increased circulating levels of eight specific lipid molecules and one bile acid, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA). UDCA and two triglycerides (TG54:5 and TG56:7) are identified as key biomolecules with strong discriminatory potential. The regression model incorporating these markers, along with hepatic steatosis index (HSI) and triglycerides-glucose index (TyG), demonstrates the highest predictive accuracy for MASLD (AUC of 0.932). UDCA correlates positively with Blautia and Collinsella genus (p = 0.040 and p = 0.021, respectively), and negatively with Faecalibacterium (p = 0.030). Notably, principal component analysis based on bile acid levels reveals two possible subpopulations within the control group, one potentially at higher risk for MASLD.

Conclusions:

Combining UDCA, TG54:5 and TG56:7 with the validated HSI score provides a potential model with high specificity and sensitivity for predicting MASLD in YWVH. Moreover, early alterations in the bile acid profile may help identify YWVH at risk of developing MASLD.

Subject terms: Predictive markers, HIV infections

Plain Language Summary

Children and young people who acquired HIV at birth are increasingly developing liver problems, such as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), a condition caused by fat accumulation in the liver. While there are non-invasive tools for early detection in adults, no biomarkers are currently available for children and youth. This preliminary study aims to identify simple, blood-based markers that could support early detection of MASLD in this population. Blood and stool samples from 29 participants were analysed to examine circulating fats, bile acids, and gut bacteria. The results indicate that one bile acid and two triglycerides were higher in those with MASLD and, when combined with clinical scores, could predict the disease. These findings may support earlier diagnosis and help prevent liver damage.

Chafino et al. investigate plasma biomarkers to identify metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in youth with vertically acquired HIV. Plasma metabolomics and gut microbiome analyses reveal ursodeoxycholic acid and specific triglycerides as key molecules in a predictive model for MASLD.

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease or MASLD, previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)1,2, is becoming the commonest cause of chronic liver disease in the general population, with a global prevalence of approximately 30%3,4. MASLD is defined by the presence of ≥5% hepatic fat accumulation without other known causes of fatty liver, such as excessive alcohol consumption5. It is frequently accompanied by other comorbidities such as obesity, hypertension or type 2 diabetes6,7, all part of the metabolic syndrome. In the general population, around 20% of individuals with MASLD progress to MASH (metabolic-associated steatohepatitis, previously known as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis or NASH), fibrosis and cirrhosis in worst cases8–11. However, the mechanisms underlying this progression remain poorly understood, given the multifactorial aetiology of MASLD, which likely involves multiple factors, including genetics, diet, metabolism, and inflammation11.

Recent studies have reported a higher prevalence of MASLD among people living with HIV (PLHIV), ranging from 34 to 49%, in whom liver disease is now the second leading cause of non-HIV-related mortality12–14. Notably, MASLD affects 30% of children and young people with vertical HIV (YWVH), a rate 20% higher than in the young population without HIV infection15. Chronic inflammation and over-activation of the immune system driven by the virus may contribute to MASLD development in PLHIV. YWHIV has the peculiarity of showing a premature ageing and immune senescence phenotype, which could be associated with the early development of MASLD among other comorbidities, caused by prolonged exposure to HIV and antiretroviral treatment (ART) since birth16.

Although the pathophysiology of MASLD remains incompletely understood, some authors have pointed out adipose tissue dysfunction and lipid abnormalities17,18. For example, high levels of triglycerides (TGs) are known to increase the risk of MASLD, likely a high ratio of oleic/stearic acid levels and a low concentration of lignoceric19,20. Additionally, the gut microbiota has been implicated in MASLD development through its role in regulating hepatic function and lipid metabolism21,22. In PLHIV, alterations in the gut microbiome secondary to a massive depletion of lymphoid tissue during acute HIV infection and subsequent persistent disruption of the gut barrier despite effective ART are thought to contribute to persistent inflammation and comorbidities. These disruptions may influence MASLD development23–25 through the disruption of fatty acid oxidation and glucose metabolism, leading to the accumulation of hepatic fat26.

In adults, several clinical scores such as Hepatic Steatosis Index (HSI), Fatty Liver Index (FLI), AST to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) or Triglyceride and Glucose index (TyG) are validated for detecting MASLD27–29. However, no such non-invasive biomarkers or tools are currently available for young patients, limiting early diagnosis and intervention. We therefore hypothesize that metabolic and inflammatory changes associated with MASLD could be reflected in the lipidic profile, plasma short-chain fatty acid relative abundance and plasma bile acids, which are synthesized from cholesterol in the liver and metabolized by the gut microbiome30. A deeper understanding of MASLD pathophysiology, along with the identification of accessible biomarkers for routine clinical use, is essential to identify YWVH at risk of disease progression.

In this preliminary study, we show that YWVH with MASLD have significantly elevated circulating levels of specific lipid species and bile acids. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) and triglycerides TG54:5 and TG 56:7 emerge as key biomarkers with strong discriminatory potential. A regression model combining these markers with HIS and TyG scores achieves high predictive accuracy for MASLD. Moreover, principal component analysis of bile acid levels reveals two subpopulations within the control group, one potentially at increased risk for MASLD. These findings support the development of a non-invasive predictive model and suggest that early alterations in bile acid profiles may help identify YWVH at risk of liver disease.

Methods

Study design

Retrospective and cross-sectional study which comprised 29 youths with vertically acquired HIV (YWVH) under ART participating in the NashVIH Study, a study addressing the prevalence of MASLD in the CoRISpe-FARO cohort62. All individuals were recruited between June 2018 and December 2020 at Hospital Universitario La Paz and Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón in Madrid (Spain). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of participating hospitals (HULP-PI-3138) and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants signed informed consent before inclusion in the study. All patients included in the study were screened for a full panel of metabolic and infectious diseases with liver involvement, including viral infections. Participants with a history of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) and/or HCV or co-infection, acute infections or opportunistic diseases, or chronic inflammatory diseases at study inclusion, and/or daily reporting >30 g in men and >20 g in females of alcohol intake were excluded.

All information was collected and stored in a RedCAP database specially designed for this purpose and allocated to the Research Institute. Data regarding socio-demographic and clinical data were obtained from the medical records of the CoRISpe-FARO cohort, including comorbidities, historic virological and immunological data. Weight, height, waist, and hip measurements were taken according to a unified protocol. Body Mass Index (BMI) was automatically calculated, and z-score adjusted were determined. Standard deviations for BMI according to age and gender were calculated for those below 18 years of age using the 2010 Spanish Growth charts. Overweight was defined as a BMI z-score between +1 and +2 SD, and obesity as > 2 SD. For patients >= 18 years, the WHO definition for overweight (BMI > 25) and obesity (BMI > 30) was used.

Both shear wave ultrasounds (p-SWE) and transient elastography (TE) with controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) were used to establish MASLD diagnosis. The criteria defined by Dasaranthy S et al. and Bril F et al.64,65 were used for the diagnosis of steatosis by pSWE: increased parenchymal echogenicity of the liver, hepatic vein blurring, portal vein blurring and visualization of diaphragm as described elsewhere15. CAP evaluates the ultrasonic attenuation in the liver at 3.5 MHz at a depth 25–65 mm using FibroScan. CAP values in dB/m were reported as the median of 10 acquisitions, and the cut-off point of 248 dB/m defined by Karlas et al.63 was used to evaluate the presence of steatosis. Furthermore, four scores validated to predict liver abnormalities in the adult population were calculated for study participants, and their accuracy in predicting MASLD was compared to non-invasive imaging techniques. Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4), Hepatic Steatosis Index (HSI), Triglyceride Glucose Index (TyG)] and AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) were calculated to predict fibrosis/MASLD using MedCalc Statistical Software version 19.2.6 (MedCalc Software bv, Ostend, Belgium; https://www.medcalc.org; 2020) (https://www.mdcalc.com/)15. FIB-4 (age*AST)/(platelet count*√ALT) was used to evaluate liver fibrosis, and a value > 2.67 suggests fatty liver, and >3.25 suggests cirrhosis by HCV; a value < 1.3 is relevant to exclude significant fibrosis. HIS (8*ALT/AST + BMI (+2 if type 2 diabetes, +2 if female) is an index used to identify candidates for liver study, and for interpretation, MASLD was diagnosed >36, ruled out with a value < 30, whereas values between 30 and 36 are considered inconclusive. TyG (ln [fasting triglyceride (mg/dl)*fasting glucose (mg/dl)]/2) is an index to determine insulin resistance when it is 4.49 or larger and to identify individuals at risk for liver steatosis when it is 8.38 or larger. APRI (AST (IU/L)/AST upper normal limit (IU/l)/platelet count (109/l)*100) values < 0.5 ruled out fibrosis.

Plasma sampling and biochemistry analysis

Fasting blood was drawn for the usual blood and biochemistry tests, including a complete lipid profile. Liver enzymes (AST, ALT, and GGT) were considered elevated according to laboratory ranges: ALT > 35UI/L, AST and GGT when > 40 UI/L. Fasting total cholesterol was considered elevated when > 200 mg/dL and triglycerides when >150 mg/dL66. Real-time measurements of plasma HIV-1 viral load (VL) were quantified using the Cobas TaqMan HIV-1 assay (Roche Diagnostics Systems, Inc., Branchburg, NJ) with a detection limit of 50 copies/mm3. Absolute and percentage of CD4 and CD8 T-cells were measured with standard flow cytometric methods. Plasma for omics analysis was obtained from total blood and was stored at −80 °C until use.

Faecal samples and 16S rDNA sequencing of gut microbiota

Stool samples were collected in regular stool collection tubes at inclusion, processed and cryopreserved at −80 °C until use. For sequencing, DNA extraction was performed in the robotic workstation MagNA Pure LC Instrument (Roche) using the MagNA Pure LC DNA isolation kit III (Bacteria, Fungi) (Roche). Total DNA was quantified with a Qubit Fluorometer (ThermoFisher). For each sample, the V3-V4 regions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified and the amplicon libraries were constructed following Illumina instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The sequencing was performed using kit V3 (2 × 300 cycles) with MiSeq sequencer (Illumina) at the IRYCIS Sequencing Service, Madrid, Spain. We obtained an average of 143,7411494 (removing outliers) 16S rRNA joined sequences per sample.

Metagenomic analysis

The taxonomic sequence classifier Kraken (v2.0.7-beta, paired-end option), which examines the k-mers within a query sequence, was used to estimate the taxonomic assignment for the sequencing reads using the 16S rRNA gene amplicon data. This database maps k-mers to the lowest common ancestor of all genomes known to contain a given k-mer. Silva ribosomal RNA Database (release 132), available in the Kraken 2 web, was used to obtain the taxonomic information on the 16S rDNA sequences. Sequences were pre-processed and quality control was applied by using the trimmomatic package (v0.33 Paired End method, minimum length of 100, average quality of 30) to filter the reads by length and quality. For subsequent analyses, only those annotated OTUs that belonged to the Bacteria domain were considered and were used to select the 15 most abundant genus. The ggplot2 package was used to generate the different spatial plots using R Statistics version 4.3.1.

Lipidomics analysis by Folch extraction (Lip-II) by LC-QTOF

For the extraction of hydrophobic lipids, liquid-liquid extraction with chloroform:methanol (2:1) based on the Folch procedure was performed by adding four volumes of chloroform:methanol (2:1) containing an internal standard mixture (Lipidomic SPLASH®) to plasma as previously described67,68. Then, the samples were mixed and incubated at −20 °C for 30 min. Afterwards, water with NaCl (0.8 %) was added and the mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm. The lower phase was recovered, evaporated to dryness and reconstituted with methanol:methyl-tert-butyl ether (9:1) and analysed by UHPLC-qTOF (model 6550 of Agilent, USA) in both positive and negative electrospray ionization modes. The chromatographic method consisted of elution with a ternary mobile phase containing water, methanol, and 2-propanol with 10 mM ammonium formate and 0.1% formic acid. The stationary phase was a C18 column (Kinetex EVO C18 Column, 2.6 μm, 2.1 mm×100 mm) that allows the sequential elution of the more hydrophobic lipids such as lysophospholipids, sphingomyelins, phospholipids, diglycerides, triglycerides, and cholesteryl esters, among others. Lipid species were identified by matching their accurate mass and tandem mass spectrum, when available, to Metlin-PCDL from Agilent, containing more than 40,000 metabolites and lipids. In addition, the chromatographic behaviour of pure standards for each family and bibliographic information was used to ensure their putative identification. The identification indicates the lipid family (LPC-lysophosphatidylcholine, PC-phosphatidylcholine, SM-sphingomyelin, MG-Monoacylglycerol, DG-diglyceride, TG-triglyceride, Cer-Ceramide and ChoE-cholesterol ester), the total number of carbons of the acyl chains and the number of double bonds. Optimised retention time (min) and precursor ion (m/z) for each identified lipid species are indicated as supplementary data (Supplementary Data 1).

Determination of bile acids by HPLC-MS/MS

Samples (100 μL plasma) were aliquoted into 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes and mixed with 400 μL of 100 ng/mL CA-d5 and 100 ng/mL TCA-d5 in ACN. Samples were vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 15,000 rpm and 4 °C. Supernatants were transferred to a new tube and were evaporated in a SpeedVac at 45 °C. Samples were reconstituted with 50 μL of methanol:water (1:1) and transferred to glass vials for their analysis. The chromatographic separation was performed with a mobile phase A containing 0.1% ammonium hydroxide and 10 mM ammonium acetate and B with Acetonitrile. The column temperature was set at 27 °C, and the injection volume was 2 μL. Optimised retention time (min), precursor ion and product ion (m/z), and collision energy (CE) for each identified bile acid are indicated as supplementary data (Supplementary Data 1).

Statistics

Before the statistical analyses, the normal distribution and homogeneity of the variables were tested using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas variables with a skewed distribution were represented as the median (Interquartile range: 25th percentile – 75th percentile). Statistical differences between groups were performed using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U-test. Global significance of qualitative variables such as sex, symptoms, comorbidities, and clinical treatments was calculated with the χ2 test for categorical data according to MASLD development. Associations between quantitative variables were evaluated using the Spearman correlation test, whereas qualitative variables were evaluated using by biserial-point correlation test. Logistic regression analyses and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were employed to evaluate the potential accuracy of different lipid levels with selected parameters for the diagnosis of MASLD development. Random forest (RF) analyses and sparse PLS-DA (sPLS-DA) were performed using MetaboAnalyst 6.0 software to determine the bile acids and lipids with higher accuracy for classifying patients according to MASLD development. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 21.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and graphical representations were generated with GraphPad Software (GraphPad Prism version 9.4.1), PowerPoint software (version 2007) and MetaboAnalyst 6.0. The comparisons were considered significant at P values < 0.05.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of participating hospitals (HULP-PI-3138) and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All adult participants signed the informed consent form, and for minors, parental consent was obtained prior to their inclusion in the study.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Participants Characteristics

The study cohort comprised 29 YWVH, 10 presenting MASLD and 19 without MASLD (Control group) (Table 1). Both groups, MASLD and Control, were formed mostly by women (60% and 63%, respectively), ranging from 10 to 27 years of age. BMI was higher in the MASLD group (p = 0.05), with a non-significantly increased prevalence of overweight/obesity in that group. No significant differences were detected with biochemical parameters, but both aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet ratio index (APRI) and hepatic steatosis index (HSI) were significantly different between groups (Table 1). All patients were on ART, and most were suppressed, and one participant in each group had a CD4+ nadir <200 cells/μL. The commonly used current ART regimen in the two groups was the combination of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) with one integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI).

Table 1.

Characteristics of youth with vertical HIV (YWVH) with MASLD (MASLD) or without MASLD (Control)

| MASLD (n = 10) | Control (n = 19) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20 (10.70–27) | 18 (15–24) | 0.369 |

| Sex (Women) | 6 (60%) | 12 (63.2%) | 0.868 |

| BMI | 23.25 (20.45–25.45) | 19 (19–22.50) | 0.051 |

| Overweight (BMI > 25) | 3 (30%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0.066 |

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 0.161 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 79.5 (77–86.7) | 82 (72–84) | 0.730 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 83 (68.75–173.75) | 77 (57–137) | 0.536 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 171 (136–181.50) | 153 (146–174) | 0.535 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 102.5 (74.25–117.75) | 83 (59.50-96) | 0.187 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 43 (36–52.25) | 51 (46–56) | 0.077 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.475 (0.40–59) | 0.5 (0.34–16) | 0.651 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (U/L) | 18 (12–24.50) | 22 (12–28) | 0.475 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (U/L) | 17.5 (14.50–21) | 22 (14–21) | 0.231 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) (U/L) | 19 (15–36.50) | 17 (14–21) | 0.310 |

| Fibro Scan values (Kpa) | 5.15 (3.72–6.62) | 5 (4.55–5.55) | 0.907 |

| Fibrosis-4 score (FIB-4) | 0.26 (0.18–0.40) | 0.34 (0.24–0.55) | 0.172 |

| AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) | 0.15 (0.10–0.20) | 0.20 (0.20–0.30) | 0.040 |

| Hepatic steatosis index (HSI) | 33.95 (28.45–39.72) | 27.95 (26.87–32.05) | 0.017 |

| TyG | 4.39 (4.27–4.78) | 4.4 (4.22–4.61) | 0.520 |

| Viral loads detectable (>50 copies/ml) | 0 (0%) | 5 (26.3%) | 0.075 |

| CD4+ T-cell count | 880.50 (670–1442.5) | 792.50 (665–1081.75) | 0.350 |

| CD8+ T-cell count | 820 (685–1101) | 814 (519.50–955) | 0.402 |

| CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratio | 1.50 (0.94–2.06) | 1.20 (0.91–1.57) | 0.303 |

| CD4+ T-cell Nadir | 296.50 (212–370.50) | 443 (310.75–524.5) | 0.055 |

| CD4+ T-cells <200 cell/ul | 1 (10%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0.676 |

| Years in ART | 17 (9.83–25.73) | 15.65 (11.9–22.15) | 0.732 |

| Current ART (%) | |||

| 1 PI (%) | 2 (20) | 1 (5.3) | 0.215 |

| 1 PI + 1 INSTI (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.3) | 0.460 |

| 1 NNRTI + 1 INSTI (%) | 1 (10) | 1 (5.3) | 0.632 |

| 2 NRTI + 1 INSTI (%) | 3 (30) | 10 (52,6) | 0.244 |

| 2 NRTI + 1 PI (%) | 1 (10) | 4 (21.1) | 0.454 |

| 2 NRTI + 1 NNRTI (%) | 3 (30) | 2 (10.5) | 0.187 |

| 2 NNRTI + 2 INSTI | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

Statistical differences between groups were performed using the χ2 test for categorical data and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous data according to MASLD development. Data are presented as N (%) or median (25th–75th interquartile range). BMI body mass index, TyG triglycerides and fasting glucose index. TyG Triglycerides and fasting glucose index, PI Protease inhibitor, INSTI integrase strand transfer inhibitors, NNRTI non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and NRTI nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. The significant p-value is marked in bold.

Alteration of lipidic profile in MASLD

A total of 15 bile acids and 178 lipid species were identified in plasma samples. Univariate analyses indicated that ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) was the only bile acid significantly increased in the MASLD group (p = 0.029) (Fig. 1a). One diacylglyceride (DG) (DG36:3 (p = 0.0017)) and seven different triacylglycerides (TG) (TG53:4 (p = 0.035), TG54:4 (p = 0.017), TG54:5 (p = 0.003), TG52:4 (p = 0.019), TG52:5 (p = 0.035), TG52:3 (p = 0.044) and TG56:7 (p = 0.007)) were also significantly increased in the MASLD group (Fig. 1a). Random forest (RF) analysis showed UDCA, TG54:5 and TG56:7 as the bile acid and the lipid species that better differentiated the two groups (Fig. 1b). UDCA relative abundance positively correlated with TG54:5 (ρ = 0.489, p = 0.013) and TG56:7 (ρ = 0.413, p = 0.040).

Fig. 1. Plasma relative abundance of UDCA and several lipid species increased in MASLD.

a Relative abundance representation of bile acid and lipid species that resulted significantly different between the MASLD group (green, n = 10 independent samples) and the Control group (orange, n = 19 independent samples). Data is represented by box and whiskers plots with an error bar indicating the standard deviation. Significance between groups (p values < 0.05) was determined by the non-parametric U-Mann-Whitney test. b Random Forest graphs of all bile acids (left) and top eight lipid species (right) in YWVH comparing the MASLD group to the Control. Random forest (RF) analyses were performed using MetaboAnalyst 6.0 software. The intensity of colours indicates the significance of the compound in differentiating groups (high in red and low in blue). c Heatmap showing the Spearman correlation coefficient (p) of pairwise comparison analyses between relevant biochemical parameters and clinical scores in MASLD with levels of the top three molecules differentiating groups. d Heatmap showing the Point-biserial correlation coefficient (pb) of pairwise comparison analyses between overweight and obesity and the top three biomolecules differentiating groups. Correlation analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software, and heatmaps were generated with GraphPad Software. The correlation matrix is colour-coded according to the Spearman correlation coefficient (1:−0.5, red:blue through white), and correlations with statistical significance are indicated with an asterisk as *p < 0.05. UDCA Ursodeoxycholic acid, DG Diacylglycerol, TG Triglycerid, GCDCA Glycochenodeoxycholic acid, GCA Glycocholic acid, CDCA Chenodeoxy-cholic acid, TLCA Taurolithocholic acid, TUDCA Tauroursodeoxycholic acid, TCDCA Taurochenodeoxycholic acid, GDCA Glycodeoxycholic acid, DCA Deoxycholic acid, TCA Taurocholic acid, LCA Lithocholic acid, GUDCA Glycoursodeoxycholic acid, GLCA Glycolithocholic acid, TDCA Taurodeoxycholic acid, CA Cholic acid.

Circulating UDCA relative abundance was positively correlated with biochemical parameters of plasma total cholesterol (ρ = 0.605, P = 0.001) and total triglycerides (TGs) (ρ = 0.608, P = 0.001). Both, TG54:5 and TG56:7 were positively correlated with total plasma triglycerides (ρ = 0.693, P < 0.001 and ρ = 0.404, P = 0.033) and HSI parameter (ρ = 0.555, p = 0.009 and ρ = 0.585, p = 0.005, respectively) (Fig. 1c). TG56:7 was positively correlated with the obesity condition (ρb = 0.443, p = 0.018) (Fig. 1d).

UDCA, TG54:5 and TG56:7 as biomarkers of MASLD condition

Lipidomic-based biomarkers analysis by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves was performed individually for the three candidates that obtained the best position in the above RF analysis. Since the candidates had two specific lipid species; total triglyceride (TGs) concentrations measured by biochemical conventional methods were also included in the statistical models. The best candidate was TG56:7 with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.861 (95% CI = 0.717–1.005) (orange line). The AUCs of the other candidates were 0.806 for TG54:5 (95% CI = 0.634–977), 0.806 for UDCA (95% CI = 0.626–985) and 0.580 for TGs (95% CI = 0.337–823) (Fig. 2a). Binary logistic regressions combining the selected molecules were also assessed for improving the discriminatory power of the candidates. The two best combinations were UDCA + TG56:7 (blue line) and UDCA + TG54:5 + TG56:7 (purple line) with the same AUC of 0.882 (95% CI = 0.735–1.029) followed by TG54:5 + TG56:7 (green line) with an AUC of 0.840 (95% CI = 0.687–0.994) and UDCA + TG54:5 with an AUC of 0.806 (95% CI = 0.625–0.986) (Fig. 2b). ROC curves were also performed for the two clinical scores related to steatosis development in the MASLD condition, TyG and HSI, to compare the distinguishing power of validated clinical parameters with the selected lipids. The AUC for TyG was 0.616 (95% CI = 0.356–0.876) and the AUC for HSI was 0.813 (95% CI = 0.628–977) (Figure c). In addition, the discriminatory power of different combinations of selected biomolecules and HSI and TyG for differentiating MASLD and Control was analysed by binary logistic regression. The combination of UDCA, total triglycerides (biochemical parameter), HSI and TyG obtained an AUC of 0.875 (95% CI = 0.700–1.050) (green line). The combination of the three selected biomolecules (UDCA + TG 54:5 + TG56:7) with HSI and TyG scores, however, significantly improved the discriminatory power of the model with an AUC of 0.932 (95% CI = 0.819–1.044) (red line) (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2. Biomarkers associated with MASLD.

a Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of the most significant bile acid (UDCA) and first two lipids (TG54:5 and TG 56:7) in random forest analysis and plasma total triglycerides (TGs) to discriminate MASLD from the Control group. b ROC curves of binary logistic regression combining lipidic molecules. c Information on the Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves between MASLD and Control. d ROC curves of the two significant clinical scores for clinical steatosis detection (HSI and TyG). e ROC curves of binary logistic regression combining clinical scores and lipidic molecules. Logistic regression analyses and ROC curves were performed using IBM SPSS Software. UDCA Ursodeoxycholic acid, TGs Triglycerides, TyG Triglycerides and Glucose ratio, HSI hepatic steatosis index. MASLD ≥ indicates the cut-off value for each variable with specific specificity and sensitivity

Gut microbiota associated with plasma UDCA relative abundance

Bile acids modulate gut microbiota composition and function by activating host signalling pathways31.

First, the microbiota of the participants was evaluated to identify the most abundant genus in each group. Faecal samples were available for 25 of the 29 YWVH included in the study; nine belonged to the MASLD group (n = 9/10) and 16 to the Control group (n = 16/19). A total of 444 different genus abundances were identified in each group, of which the top 15 are shown in Fig. 3a. No significant differences were observed between groups, but the analysis with the top 15 showed that the relative abundance of six genus predominated in the MASLD group compared to the Control group, of which Bifidobacterium, Blautia and Catanenibacterium obtained the highest relative levels (Fig. 3b). By contrast, another six genus resulted in lower values in the MASLD group compared to the Control group, of which Bacteroides and Faecalibacterium were in the top 3. Of note, Lachnospiraceae UGC-008 and Subdoligranulum obtained the same relative abundance in both groups.

Fig. 3. Relative abundances of gut microbiota.

a Bar-plot analysis shows the top 15 genus abundances in each group. The ggplot2 package was used to generate the different spatial plots using R Statistics. b Relative abundance levels of the most abundant genus. No significant differences between the MASLD group (green, n = 10 independent samples) and the Control group (orange, n = 19 independent samples) were observed by the non-parametric U-Mann Whitney test. Data is represented by box and whiskers plots with the error bar indicating the standard deviation, and each dot represents an individual. c Spearman correlation between levels of UDCA and the different relative abundance of specific genus. Green dots represent the MASLD group, and orange dots represent the MASLD group. Correlation analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software

Then, we tested whether circulating UDCA, the bile acid that was significantly different between the two groups, was correlated with any of the most abundant genus that composed the microbiota of the participants. Interestingly, Blautia and Collinsella positively correlated (ρb = 0.441, p = 0.040, and ρb = 0.511, p = 0.021, respectively) and Faecalibacterium negatively correlated with UDCA relative abundance (ρb = −0.462, p = 0.030) (Fig. 3c).

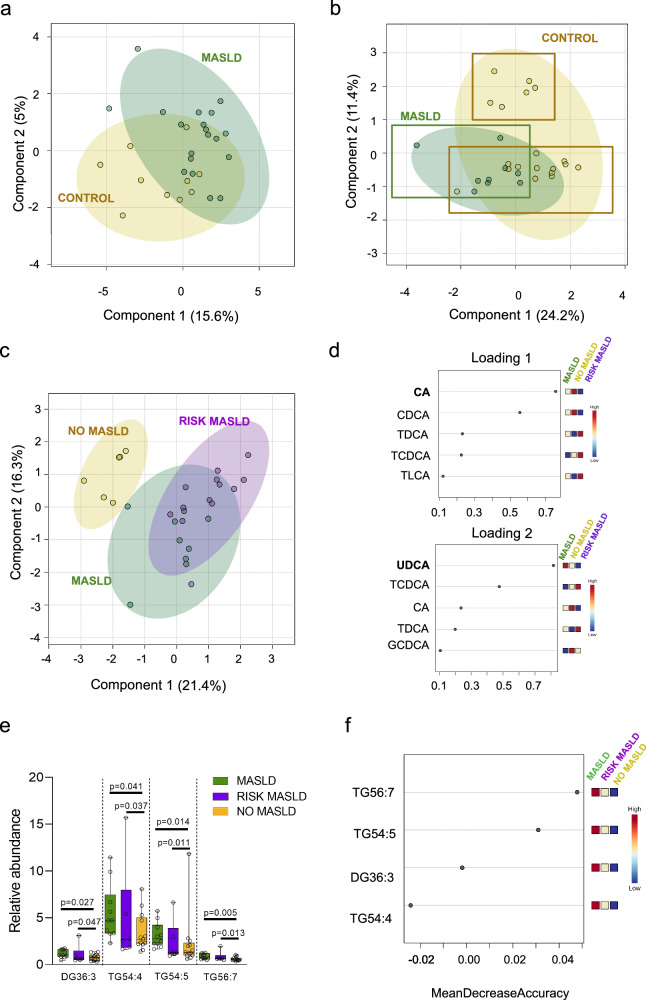

Bile acid profile as an early predictor of MASLD development

Finally, an overview of metabolites was analysed using sparse PLS-DA (sPLS-DA) algorithms to validate the possibility of MASLD classification based on lipids or bile acids. Lipids visualisation using sPLS-DA plot showed model discrimination between MASLD and Control groups with a partial overlap (Fig. 4a). The separation between groups reinforced the role of lipidomic-based biomarkers in MASLD identification during YWVH care follow-up.

Fig. 4. Subpopulations in the Control group based on bile acid levels.

a sPLS-DA plot constructed on the lipid profile, including all lipids detected in 19 Control (in yellow) and 10 MASLD (in green). b sPLS-DA plot constructed on the bile acid profile, including all bile acids detected in 19 Control (in yellow) and 10 MASLD (in green), shows two subpopulations in the Control group. c sPLS-DA plot constructed on the bile acid profile distinguishing the three populations: NO MASLD for the subpopulation with low risk to develop MASLD (in yellow), and RISK MASLD (in purple) for the subpopulation that presented a bile acid profile like MASLD group (in green). Coloured circles represent 95% confidence intervals, and coloured dots represent individual samples. d Loading plots show the variables that contribute most to group separation among MASLD, RISK MASLD and NO MASLD in components 1 and 2 of the proposed sPLS-DA model. sPLS-DA analyses and representation were performed using MetaboAnalyst 6.0 software. e Relative abundance of different significant lipids depending on bile acid classification (MASLD n = 10 independent samples, RISK MASLD n = 6 independent samples and NO MASLD n = 13 independent samples). Significance between groups (p values < 0.05) was determined by the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis and U-Mann Whitney test. Data is represented by box and whiskers plots, with an error bar indicating the standard deviation, and each dot represents an individual. f Random Forest of significant lipids in YPLHIV comparing MASLD, RISK MASLD and NO MASLD groups (left to right) by MetaboAnalyst 5.0. The intensity of colours indicates the significance of the compound in differentiating groups (high in red and low in blue).

The sPLS-DA plot based on the bile acid profile also discriminated between the MASLD and Control group with a partial overlap (Fig. 4b). Of interest, the discriminatory model revealed a clear subpopulation within the Control group that was clustered near the MASLD group, based on loadings of component 2 (y axis) (Fig. 4c). UDCA was identified as the most important component separating the samples in component 1 and corroborated the role of plasma UDCA in MASLD identification during YWVH care follow-up (Fig. 4d). Cholic acid (CA) was identified as the most important compound separating the samples in component 2 (Fig. 4d), suggesting a potential role of bile acids in identifying YWVH at risk of MASLD. Thus, the Control group was reclassified into two subgroups (Fig. 4c), NO MASLD and RISK-MASLD, and the potential of bile acids as an early predictor of MASLD development was evaluated.

Patient characteristics were reanalysed based on this new classification criterion, including the three groups (Table 2). The RISK-MASLD group were mainly composed of younger women with a median age of 17 years (p = 0.035). BMI was higher in the MASLD group compared to RISK-MASLD and NO-MASLD (p = 0.019). Related to specific liver function tests to detect hepatic steatosis, FIB-4 and APRI values were higher in the NO-MASLD group compared to RISK-MASLD and MASLD groups (p = 0.014 and p = 0.054, respectively), and the HSI parameter showed the highest value in the MASLD group (33.95 (28.45–39.72) (p = 0.054)). Of interest, RISK-MASLD obtained intermediate APRI (0.20 (0.15–0.25)) and HSI (28.1 (27.1–31.6)) values as well as the lowest BMI values (18.7 (17.8–19.7) kg/m2) of the three groups. No significant differences were detected in biochemical, viral load and immunity parameters among groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of YWVH participants classified based on bile acid profile

| MASLD (n = 10) | RISK MASLD (n = 13) | NO MASLD (n = 6) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20 (10.7–27) | 17 (10.5–18.5) | 24 (19–24.25) | 0.035 |

| Sex (Women) | 6 (60%) | 9 (69.2%) | 3 (50%) | 0.714 |

| BMI | 23.25 (20.45–25.45) | 18.7 (17.8–19.7) | 21.35 (19.07–24.85) | 0.019 |

| Overweight (BMI > 25) | 3 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0.115 |

| Obesity (BMI > 30) | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.374 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 79.5 (77–86.7) | 78 (74.5–84) | 84 (80.25–85.75) | 0.388 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 83 (68.75–173.75) | 75 (52–143) | 78 (63.5–277) | 0.766 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 171 (136–181.5) | 153 (129–177.5) | 152.5 (149–175) | 0.780 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 102.5 (74.25–117.75) | 78 (68–108.5) | 84 (80.5–90) | 0.411 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 43 (36–52.25) | 52 (48–58) | 46.5 (41.25–57.25) | 0.112 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.475 (0.4–59) | 0.50 (0.34–0.59) | 1.89 (0.45–31.75) | 0.528 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (U/L) | 18 (12–24.5) | 22 (13–27) | 18 (11.25–29.75) | 0.752 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (U/L) | 17.5 (14.5–21) | 19 (15.5–29) | 24.5 (13.75–32.2) | 0.436 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) (U/L) | 19 (15–36.5) | 17 (14–21.5) | 17.5 (11.75–28.5) | 0.596 |

| Fibro Scan values (Kpa) | 5.15 (3.72–6.62) | 5 (4.2–5.45) | 5.2 (4.75–7.3) | 0.706 |

| Fibrosis-4 score (FIB-4) | 0.26 (0.18–0.40) | 0.255 (0.21–0.335) | 0.52 (0.415–0.68) | 0.014 |

| AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) | 0.15 (0.1–0.2) | 0.2 (0.15–0.25) | 0.3 (0.175–0.55) | 0.054 |

| Hepatic steatosis index (HSI) | 33.95 (28.45–39.72) | 28.1 (27.12–31.62) | 27.35 (26.8–34) | 0.054 |

| TyG | 4.39 (4.27–4.78) | 4.34 (4.1–4.6) | 4.41 (4.23–4.8) | 0.732 |

| Viral loads detectable (>–50 copies/ml) | 0 (0%) | 3 (23.1%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0.175 |

| CD4+ T-cells count | 880.5 (670–1442.5) | 727 (580–1020.5) | 1000 (801–1216) | 0.310 |

| CD8+ T-cells count | 820 (685–1101) | 843 (596.5–997.5) | 540 (410–814) | 0.213 |

| CD4+/CD8+ T-cells ratio | 1.5 (0.94–2.06) | 1.24 (0.86–1.56) | 1.16 (0.96–1.81) | 0.556 |

| CD4+ T-cells Nadir | 296.5 (212–370.5) | 443 (321–810) | 459 (241.25–508.75) | 0.154 |

| CD4+ T-cells <200 cell/ul | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0.825 |

| Years in ART | 17 (9.83–25.73) | 13.45 (11.37–17.2) | 20.6 (17.22–23.9) | 0.226 |

| Current ART | ||||

| 1 PI (%) | 2 (20) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 0.407 |

| 1 PI + 1 INSTI (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 0.137 |

| 1 NNRTI + 1 INSTI (%) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 0.367 |

| 2 NRTI + 1 INSTI (%) | 3 (30) | 7 (53.8) | 3 (50) | 0.501 |

| 2 NRTI + 1 PI (%) | 1 (10) | 4 (30.8) | 0 (0) | 0.194 |

| 2 NRTI + 1 NNRTI (%) | 3 (30) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (16.7) | 0.373 |

| 2 NNRTI + 2 INSTI (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

Statistical differences between groups were performed using the χ2 test for categorical data and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous data according to MASLD development. Data are presented as n (%) or median (25th-75th interquartile range) TyG Triglycerides and fasting glucose index, PI Protease inhibitor, INSTI integrase strand transfer inhibitors, NNRTI non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and NRTI nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. The significant p-value is marked in bold.

Finally, alteration in lipid profile was evaluated according to this new criterion (three groups). DG 36:3, TG 54:4, TG 54:5 and TG 56:7 resulted significant increase in MASLD and RISK-MASLD groups. The relative abundance of these lipid species showed a decreasing pattern towards the NO-MASLD group (Fig. 4e). RF analysis confirmed TG56:7 and TG54:5 as the lipid species that better differentiated the NO-MASLD group from the MASLD group. Any lipid species obtained the ability to differentiate the RISK-MASLD group from the NO-MASLD group (Fig. 4f).

Discussion

MASLD has turned into a major public health problem8, whose prevalence has increased among PLHIV (around 45%, depending on the diagnostic technique)14, maybe due to ART exposure or chronic inflammation, combined with obesity or other metabolic factors32. Identifying patients at risk is key, as no treatment is available, and prevention is nowadays the only proven intervention. There are different clinical scores to identify MASLD patients, such as HSI, FLI, APRI or TyG27–29, validated in adult populations but not in children and youth. Among YWVH, the prevalence of MASLD reaches 30% versus 10% in the absence of HIV15,33. Non-invasive biomarkers for early detection and progression of MASLD in youths are very much needed, and our results suggest that lipid profiles might be useful.

Total plasma triglycerides, which have been traditionally reported as the clinical parameter most significantly related to MASLD, have been recently replaced by TyG, which has been validated as the most sensitive and accurate non-invasive clinical score for the diagnosis of MASLD in HIV-uninfected adults34,35. Unfortunately, this clinical score was not valid to differentiate youth with MASLD in the present study (p = 0.520). In our study, the hepatic steatosis index (HSI) was higher in the MASLD group, although the mean values of 34 HSI were below the threshold for MSLD diagnosis. These results underline the need to identify new biomarkers of MASLD in youth. In this sense, plasma triglycerides, together with phosphatidylcholines (PCs) and total saturated fatty acids, have been previously related to MASLD when compared with healthy uninfected individuals36–39. In this preliminary study, seven different lipid species were significantly different according to MASLD status. Among the seven lipid species identified, increased levels of DG36:3, TG52:4 and TG54:4 were previously related to MASLD in people without HIV40. In line with these findings, our study confirmed that an increase in the relative abundance of plasma TG54:5 and TG56:7 showed the best ability to differentiate MASLD from the Control group (YWVH without MASLD)37. On the other hand, it has also been previously reported that bile acids, which play a key role in the metabolism of cholesterol and dietary fatty acids41,42, were altered in people who suffer steatosis or MASLD43,44. In the present study, the plasma relative abundance of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) was significantly increased in the MASLD group compared to the control group. UDCA is a secondary bile acid produced in the colon by the bacterial metabolism of the primary bile acid, chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA)45,46. Curiously, UDCA, previously reported in MASLD47, is often referred to as the “therapeutic” bile acid due to its anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective actions in several conditions, including neurological, ocular, cardiovascular, and metabolic disorders48. UDCA has been proposed as a possible treatment for MASLD, although the results of the different clinical trials are inconclusive49. Due to its anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic role56, an increase in circulating UDCA levels in MASLD could be a natural response to the inflammation and tissue damage resulting from fat deposition in the liver47.

Of note, the combination of the three identified molecules, which were significantly altered in the MASLD group, together with the validated clinical scores for MASLD diagnosis, resulted in a potential model for predicting MASLD in our study cohort of YWVH. First, our results confirmed the potential of both HSI and TyG scores in differentiating MASLD from the Control group (AUC of 0.813 and 0.616, respectively) rather than using plasma total triglycerides (AUC 0.580). Second, the ROC curves also highlighted the potential of UDCA, TG 54:5 and TG 56:7 in the clinical MASLD diagnosis. Each of them showed a higher precision for the differentiation of MASLD compared to plasma triglycerides alone (AUC 0.580) or TyG score (0.616). Even in the case of TG 56:7, its ability to differentiate MASLD from the control group resulted in a higher AUC than that obtained when using the HSI (AUC 0.861 vs. AUC 0.813, respectively). Furthermore, the combination of TG 56:7 with other molecules improved the AUC from 0.861 to 0.882 (UDCA + TG56:7 or UDCA + TG54:5 + TG56:7), which demonstrated that this triglyceride could be a good candidate to be considered a “gold standard” in MASLD diagnosis. Third, the combination of clinical scores accepted for MASLD diagnosis and our three-pointed molecules resulted in an improved predictive model with high specificity and sensitivity. The proposed model, including both HSI and TyG together with values for UDCA, TG 54:5 and TG56:7, resulted in an AUC of 0.932, which suggests that, if further confirmed, the test could have a very good diagnostic performance.

There is a close relationship between liver function and the composition of the microbiota through the gut-liver axis, which controls bile acid metabolism, nutrient absorption and immunity50. Disruption of microbial homoeostasis can lead to dysbiosis, resulting in increased gut permeability and inflammation, and consequently altering the levels of bile acid and SCFA, which are essential for lipid metabolism and maintaining the integrity of the gut endothelial barrier51,52. The translocation of bacterial metabolites from the gut to the liver via the portal venous system and elevated levels of ethanol resulting from bacterial metabolism are associated with liver disease and inflammation53. In MASLD patients, low bacterial diversity has been reported, although several phyla predominance have been observed54. In this study, Bifidobacterium, Blautia and Catanenibacterium obtained the highest relative levels in the MASLD group compared to the Control group. Of note, the high presence of Blautia has been associated with worse development of the liver disease55. By contrast, Bacteroides and Faecalibacterium were those with the lowest relative abundance in the MASLD group, according to those previously reported56,57. Decreased abundance of Faecalibacterium has been accentuated in lean MASLD compared with obese people23,58. Fecalibacterium is a bacterial producer of butyrate, a bacterial metabolite, which helps to maintain the intestinal barrier in proper condition and regulates the immune system65,66; low abundance of Faecalibacterium could explain decreased levels of butyrate, which has been associated with MASLD59. By contrast, Collinsella, one of the main producers of UDCA through the 7α/7β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases, were positively correlated with UDCA relative abundance, which may explain the elevated levels of UDCA in YWVH with MASLD60. Although these results may support data previously reported, it should be noted that in this study no significant differences were observed regarding the presence of MASLD associated with microbiota. But our results showed that the lipidomic profile changes significantly in YWVH and could be a better option for use as a diagnostic tool for MASLD detection, rather than specific microbiota composition or classical clinical scores.

Finally, based on bile acid analysis, two different subpopulations were identified in the Control group (NO MASLD group). Of interest, one of the subpopulations identified was closely related to the plasma bile acid profile of the MASLD group. Curiously, the new subgroup identified (RISK MASLD) revealed a similar FIB-4 scoring to the MASLD group, which did not even show pathological values for our groups of study. These results suggested that although there is no clinical evidence that the new subgroup suffered from MASLD, changes in bile acid levels may begin to reflect an early pathogenic state for this subgroup of NO MASLD participants. It is previously reported that bile acids play a role in the metabolism of cholesterol and dietary fatty acids41,42 and their levels are modified in people who suffer from steatosis or MASLD [50,51]. Indeed, some specific bile acid levels are indicators of the onset of steatosis and its progression to cirrhosis43.

This is a preliminary case-control study, but some limitations should be highlighted. The small size reduced the likelihood of more robust findings and impeded the comparison between overweight/obese and lean individuals. The lack of knowledge about previous ART and the diversity of current ART does not allow for the evaluation of the potential effect of previous ART exposure, nor for performing association analysis between ART and the lipid profile. However, it is important to point out that this is a retrospective and cross-sectional study with HIV participants from the CoRISpe Cohort, a well-characterised national paediatric cohort with exhaustive follow-up and detailed clinical data. MASLD diagnosis was not based on biopsies and/or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) test, which limited the evaluation of the real risk of being diagnosed with MASLD. Imaging techniques are not the gold standard for liver steatosis diagnosis, but allow a non-invasive approach and permit close follow-up of patients. The low sensitivity if the fat content is lower than 20-30% and the interobserver variability, partially overcome with the use of standardised parameters such as p-SWE or CAP, are some of the main limitations of imaging diagnostics. Furthermore, our results suggested no statistically significant differences in imaging diagnosis in children and youths. Despite the limitations, our results in lipid and bile acid profile concordance with the case-control classification criteria based on both image techniques and usual steatotic liver disease (SLD) scores. Of note, the present study highlighted the combination of biomarkers and clinical scores as an interesting approach to the diagnostic challenge of MASLD. Although it could still be complicated to implement these parameters in routine clinical care, if further confirmed to generate easy-to-use techniques for the rapid detection of at least one of the molecules identified to increase the rapid clinical diagnosis of uncertain MASLD in YWVH, it will be of great interest61. Longitudinal follow-up of these cohorts will provide additional data regarding the identification of patients at risk of MASLD.

In conclusion, the increasing prevalence of MASLD in PLHIV, together with the absence of non-invasive markers for early diagnosis, is a public health challenge starting in childhood. In the present preliminary study, two triglycerides (TG 54:5 and TG 56:7) and one bile (UDCA) have been identified as potential biomarkers with great ability to distinguish between youths with perinatal HIV with and without MASLD. These molecules, together with the validated HSI and TyG clinical scores for MASLD diagnosis, resulted in a potential model with high specificity and sensitivity for predicting MASLD in YWVH. If confirmed, an early alteration of the plasma bile acid profile could identify youth patients at risk of steatosis. Furthermore, the potential of the biomarkers to elaborate a clinical diagnostic tool should be assessed in future works with an appropriate study design for this purpose and including an additional sample set as a validation group.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the collaboration of all the patients, their families and medical and nursing staff who have taken part in the project. The authors thank specialized technicians of the metabolomics facility of the Centre for Omic Sciences (COS) Joint Unit of the Universitat Rovira i Virgili-Eurecat for their contribution to mass spectrometry analysis. This work was supported by the Fondo de Investigacion Sanitaria [PI17/01283, PI19/01337, PI20/00326, PI23/0080 and PI23/01493]-ISCIII-FEDER (co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund/European Social Fund; “A way to make Europe”/”Investing in your future”); the Programa de Suport als Grups de Recerca AGAUR (2021SGR01404) and the CIBER -Consorcio Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red- (CB21/13/00020, CB21/13/00077, CB21/13/00025), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and Unión Europea – NextGenerationEU. TS is supported by grants from the Programa de Intensificacioín de de la Sociedad Europea de Infectología pediatrica (ESPIDS Springboard Award 2023) and from Acción Estratégica en Salud 2024 AES INT24/00011. AR and LT-D are supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) under grant agreements “CP19/00146” and “CP23/00009”, respectively, through the Miguel Servet Programme. MF-P is supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) under grant agreements “FI24/00034” through the Contratos predoctorales de formación PFIS. LT-D is supported by “Beca de Movilidad de la SEIMC”. AR is supported by GeSIDA through the “III Premio para Jóvenes Investigadores 2019”. LT-D is supported by GeSIDA through the “IV Premio para Jóvenes Investigadores 2020”.

Author contributions

Concept and design: S.C., L.T.-D., J.H.-G., A.R. and T.S.; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data, S.A., A.O., M.L.N. and M.L.M.; drafting of the manuscript, S.C., A.R. and T.S.; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, L.T.-D., J.H.-G., C.V., M.L.N., J.P., M.L.N. and F.V.; statistical analysis, S.C. and M.F.-P.; funding acquisition, A.R. and T.S.; administrative, technical, or material support, S.F.-A.; supervision A.R. and T.S.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

Source data underlying the results shown in Figs. 1–4 are available at Supplementary Data 2. Additional information may be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Anna Rull, Email: anna.rull@iispv.cat.

Talía Sainz, Email: talia.sainz@uam.es.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s43856-025-01149-2.

References

- 1.De, A., Bhagat, N., Mehta, M., Taneja, S. & Duseja, A. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) definition is better than MAFLD criteria for lean patients with NAFLD. J. Hepatol.80, e61–e62 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan, W.-K. et al. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A State-of-the-Art Review. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr.32, 197–213 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le, M. H. et al. 2019 Global NAFLD prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.20, 2809–2817.e28 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Younossi, Z. M. et al. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology77, 1335–1347 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrne, C. D. & Targher, G. NAFLD: a multisystem disease. J. Hepatol.62, S47–S64 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyysalo, J. et al. Circulating triacylglycerol signatures in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with the I148M variant in PNPLA3 and with obesity. Diabetes63, 312–322 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anstee, Q. M., Targher, G. & Day, C. P. Progression of NAFLD to diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease or cirrhosis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.10, 330–344 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rinella, M. & Charlton, M. The globalization of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Prevalence and impact on world health. Hepatology64, 19–22 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pouwels, S. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a review of pathophysiology, clinical management and effects of weight loss. BMC Endocr. Disord.22, 63 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estes, C., Razavi, H., Loomba, R., Younossi, Z. & Sanyal, A. J. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology67, 123–133 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samy, A. M., Kandeil, M. A., Sabry, D., Abdel-Ghany, A. A. & Mahmoud, M. O. From NAFLD to NASH: Understanding the spectrum of non-alcoholic liver diseases and their consequences. Heliyon10, e30387 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Navarro, J. HIV and liver disease. AIDS Rev.25, 87–96 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith, C. J. et al. Trends in underlying causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011 (D:A:D): a multicohort collaboration. Lancet384, 241–248 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalligeros, M. et al. Prevalence and characteristics of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and fibrosis in people living with HIV Monoinfection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.21, 1708–1722 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrasco, I. et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease using noninvasive techniques among children, adolescents, and youths living with HIV. AIDS36, 805–814 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiappini, E. et al. Accelerated aging in perinatally HIV-infected children: clinical manifestations and pathogenetic mechanisms. Aging10, 3610 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soti, S., Corey, K. E., Lake, J. E. & Erlandson, K. M. NAFLD and HIV: Do Sex, Race, and Ethnicity Explain HIV-Related Risk?. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep.15, 212 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manzano-Nunez, R. et al. Uncovering the NAFLD burden in people living with HIV from high- and middle-income nations: a meta-analysis with a data gap from Subsaharan Africa. J. Int AIDS Soc.26, e26072 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arendt, B. M. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in HIV infection associated with altered hepatic fatty acid composition. Curr. HIV Res.9, 128–135 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martínez-Sanz, J. et al. Effects of HIV infection in plasma free fatty acid profiles among people with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Med.11, 3842 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, R., Mao, Z., Ye, X. & Zuo, T. Human gut microbiome and liver diseases: from correlation to causation. Microorganisms9, 1017 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamichhane, S. et al. Linking gut microbiome and lipid metabolism: moving beyond associations. Metabolites11, 55 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duarte, M. J., Tien, P. C., Somsouk, M. & Price, J. C. The human microbiome and gut-liver axis in people living with HIV. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep.20, 170–180 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safari, Z. & Gérard, P. The links between the gut microbiome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Cell Mol. Life Sci.76, 1541–1558 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aron-Wisnewsky, J. et al. Gut microbiota and human NAFLD: disentangling microbial signatures from metabolic disorders. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.17, 279–297 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komazaki, R. et al. Periodontal pathogenic bacteria, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans affect non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by altering gut microbiota and glucose metabolism. Sci. Rep.7, 13950 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bedogni, G. et al. The Fatty Liver Index: a simple and accurate predictor of hepatic steatosis in the general population. BMC Gastroenterol.6, 33 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loaeza-del-Castillo, A., Paz-Pineda, F., Oviedo-Cárdenas, E., Sánchez-Avila, F. & Vargas-Vorácková, F. AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) for the noninvasive evaluation of liver fibrosis. Ann. Hepatol.7, 350–357 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, S. et al. The triglyceride and glucose index (TyG) is an effective biomarker to identify nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Lipids Health Dis.16, 15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia, W., Xie, G. & Jia, W. Bile acid-microbiota crosstalk in gastrointestinal inflammation and carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.15, 111–128 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo, X. et al. Interactive Relationships between intestinal flora and bile acids. Int J. Mol. Sci.23, 8343 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maurice, J. B. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in HIV-monoinfection. AIDS31, 1621–1632 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clemente, M. G., Mandato, C., Poeta, M. & Vajro, P. Pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Recent solutions, unresolved issues, and future research directions. World J. Gastroenterol.22, 8078–8093 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomizawa, M. et al. Triglyceride is strongly associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among markers of hyperlipidemia and diabetes. Biomed. Rep.2, 633–636 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ling, Q. et al. The triglyceride and glucose index and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A dose–response meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol.13, 1043169 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Puri, P. et al. The plasma lipidomic signature of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology50, 1827–1838 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kartsoli, S., Kostara, C. E., Tsimihodimos, V., Bairaktari, E. T. & Christodoulou, D. K. Lipidomics in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Hepatol.12, 436–450 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flores, Y. N. et al. Serum lipids are associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a pilot case-control study in Mexico. Lipids Health Dis.20, 136 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masoodi, M. et al. Metabolomics and lipidomics in NAFLD: biomarkers and non-invasive diagnostic tests. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.18, 835–856 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang, J. et al. Applying lipidomics to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a clinical perspective. Nutrients15, 1992 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiao, T.-Y., Ma, Y., Guo, X.-Z., Ye, Y.-F. & Xie, C. Bile acid and receptors: biology and drug discovery for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Acta Pharm. Sin.43, 1103–1119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winston, J. A. & Theriot, C. M. Diversification of host bile acids by members of the gut microbiota. Gut Microbes11, 158–171 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nimer, N. et al. Bile acids profile, histopathological indices and genetic variants for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progression. Metabolism116, 154457 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boldys, A. & Buldak, L. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Navigating terminological evolution, diagnostic frontiers and therapeutic horizon-an editorial exploration. World J. Gastroenterol.30, 2387–2390 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ishizaki, K., Imada, T. & Tsurufuji, M. Hepatoprotective bile acid ‘ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA)’ Property and difference as bile acids. Hepatol. Res33, 174–177 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward, J. B. J. et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid and lithocholic acid exert anti-inflammatory actions in the colon. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.312, G550–G558 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lai, J. et al. Alterations in circulating bile acids in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomolecules13, 1356 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vang, S., Longley, K., Steer, C. J. & Low, W. C. The unexpected uses of Urso- and Tauroursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of non-liver diseases. Glob. Adv. Health Med3, 58–69 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiang, Z. et al. The role of ursodeoxycholic acid in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol.13, 140 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Albillos, A., de Gottardi, A. & Rescigno, M. The gut-liver axis in liver disease: Pathophysiological basis for therapy. J. Hepatol.72, 558–577 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forlano, R., Mullish, B. H., Roberts, L. A., Thursz, M. R. & Manousou, P. The intestinal barrier and its dysfunction in patients with metabolic diseases and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J. Mol. Sci.23, 662 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pérez-Reytor, D., Puebla, C., Karahanian, E. & García, K. Use of short-chain fatty acids for the recovery of the intestinal epithelial barrier affected by bacterial toxins. Front Physiol.12, 650313 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dinh, D. M. et al. Intestinal microbiota, microbial translocation, and systemic inflammation in chronic HIV infection. J. Infect. Dis.211, 19–27 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang, Q. et al. Gut microbiota–mitochondrial inter-talk in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front. Nutr.9, 934113 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luther, J. et al. Hepatic injury in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis contributes to altered intestinal permeability. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.1, 222–232 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zazueta, A. et al. Alteration of gut microbiota composition in the progression of liver damage in patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Int. J. Mol. Sci.25, 4387 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lenoir, M. et al. Butyrate mediates anti-inflammatory effects of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in intestinal epithelial cells through Dact3. Gut Microbes12, 1–16 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martínez-Sanz, J. et al. A gut microbiome signature for HIV and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Front. Immunol.14, 1297378 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu, L. et al. Gut microbiota and butyrate contribute to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in premenopause due to estrogen deficiency. PLoS One17, e0262855 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.He, Z. et al. Gut microbiota-derived ursodeoxycholic acid from neonatal dairy calves improves intestinal homeostasis and colitis to attenuate extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing enteroaggregative Escherichia coli infection. Microbiome10, 79 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wong, V. W.-S., Adams, L. A., de Lédinghen, V., Wong, G. L.-H. & Sookoian, S. Noninvasive biomarkers in NAFLD and NASH - current progress and future promise. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.15, 461–478 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Jose, M. I. et al. A new tool for the paediatric HIV research: general data from the Cohort of the Spanish Paediatric HIV Network (CoRISpe). BMC Infect. Dis.13, 2 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Karlas, T. et al. Individual patient data meta-analysis of controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) technology for assessing steatosis. J. Hepatol.66, 1022–1030 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dasarathy, S. et al. Validity of real time ultrasound in the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis: A prospective study. J. Hepatol.51, 1061 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bril, F. et al. Clinical value of liver ultrasound for the diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in overweight and obese patients. Liver Int.35, 2139–2146 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suwanlerk, T. et al. Lipid and glucose abnormalities and associated factors among children living with HIV in Asia. Antivir. Ther.28, 13596535231170751 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tarancón-Diez, L. et al. Early antiretroviral therapy initiation effect on metabolic profile in vertically HIV-1-infected children. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.76, 2993–3001 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tarancon-Diez, L. et al. Transient viral rebound in children with perinatally acquired HIV-1 induces a unique soluble immunometabolic signature associated with decreased CD4/CD8 ratio. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc.12, 143–151 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Source data underlying the results shown in Figs. 1–4 are available at Supplementary Data 2. Additional information may be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.