Abstract

Wound healing is a complex and dynamic process that involves the coordinated efforts of various cellular and molecular mechanisms. Chronic wounds of various etiologies, such as diabetic ulcers and pressure sores, pose significant challenges to healthcare systems worldwide due to their recalcitrant nature and associated complications. Wound healing is a complex physiological process, crucial for tissue repair and regeneration. Recently, plant-derived drugs have gained considerable attention due to their potential therapeutic applications in wound healing. In this study, we have evaluated the wound-healing properties of Ocimum canum (OC-12) extract in in-vitro and in-vivo models. Initially, we used bio-assay-guided isolation approach to identify phytochemicals present in the OC-12 extract. This leads us to isolate nine compounds for the first time from this plant. The extract’s efficacy in promoting wound closure and cell migration was evaluated using in-vitro scratch assays in fibroblast cell lines. In LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages, the extract at a concentration of 50 µg/ml reduced the pro-inflammatory cytokines i.e. IL-6 and TNF-α levels, by 27% and 37% respectively. At the concentration of 20µM, the isolated compounds BS, ND, and SL showed the 30%, 21%, and 23% inhibition of IL-6, respectively. Subsequently, BS, ND, and SL inhibited TNF-α production by 37%, 42% and 39%, respectively. The extract also possesses antioxidant potential, with a 51.7 µg/mL EC50 value as shown in DPPH radical scavenging assay. In in-vivo wound model, topical application of the 100 mg/mL extract reflected faster wound closure compared to the control, highlighting its therapeutic potential in wound management and inflammation control. These results emphasize the promising therapeutic application of OC-12 extract for the development of novel wound healing agents.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-19923-6.

Keywords: Ocimum canum (OC-12), Phytochemicals, Antioxidant, Wound-healing, Cytokine, Histopathology, Cell migration

Subject terms: Structure elucidation, Mechanism of action, Natural products

Introduction

The loss or damage to normal anatomical and functional integrity of the skin is referred to as a wound. It may be due to physical, chemical, or thermal agents, which lead to disruption of skin functionality and the underlying tissue structure. Based on time of healing, wounds can be categorised into acute and chronic wounds. Acute wounds take less than 30 days to repair the damage, while chronic wounds recover in more than 30 days1.

As a natural, dynamic process, wound healing uses cell migration, proliferation, and the deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) to restore the afflicted area’s structural integrity, which is achieved through the deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM), cell migration, and proliferation. Numerous cells, including macrophages, platelets, neutrophils, monocytes, endothelial cells, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts, must work in a well-coordinated manner to accomplish this essential operation2.

A series of processes that are triggered after an injury occurs on the skin in order to mend the damaged tissue is termed a healing cascade. Four steps comprise the healing cascade: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and maturation3. Hemostasis and microbial invasion of the wound surface typically start the healing process by causing inflammation. Pro-inflammatory cells proliferate quickly to reach the site of injury and clear the wound of pathogens and cell debris during the inflammatory stage. Following this, new tissues, matrix, and blood vessels gradually form to fill the wound area and initiate wound healing4.

However, in individuals with co-morbidities, these healing processes are delayed due to the constant secretion of pro-inflammatory molecules or impaired angiogenesis and uncoordinated healing phases, resulting in decreased rate of wound healing. Consequently, these individuals are more prone to developing chronic, non-healing wounds such as infected wounds, diabetic ulcers, venous stasis ulcers, and pressure ulcers5.

Traditional herbal remedies are primarily made from natural plants and their components. These substances are obtained from plants with minimal industrial processing. People around the world primarily rely on this form of healthcare6. According to a WHO report (2024), the annual market value of traditional medicine is growing at 7–8% annually and is expected to reach US$289 billion by 2031. The presence of several life-sustaining components generated from plants that have important physiological advantages has led researchers to examine these plants closely in an effort to regulate possible wound-healing processes7. Because of their numerous active constituents and minimal side effects, a variety of phytochemicals and related plant extracts have demonstrated a potential role in wound healing and are employed as an alternative8. Numerous studies have documented the ability of several phytochemicals, such as flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenes, and carbohydrates, to promote wound healing9.

Among these medicinal plants, Ocimum canum (syn. Ocimum americanum), commonly known as hoary basil, has been widely used in traditional systems of medicine such as Ayurveda and folk practices for treating skin diseases, cuts, and wounds due to its antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties10. Despite its established ethno-medicinal significance, there is a notable lack of scientific data validating its phytochemical profile in the context of wound healing.

To address this gap, the current study aims to investigate, for the first time, the antioxidant and wound-healing potential of OC-12 using a bioassay-guided phytochemical isolation approach. No prior reports have elucidated the isolation of specific wound-healing phytoconstituents from OC-12, highlighting the novelty of this research. The research also aims to support in vitro and in vivo findings with molecular docking to understand the mechanistic interactions of isolated phytochemicals.

Compared to their counterparts, natural compounds are generally more affordable, offer better biocompatibility, and have antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory qualities. They have also been demonstrated to improve wound healing with few adverse effects and a lower risk of resistance. The amalgamation of characteristics found in natural polymers and compounds with the less-researched external stimuli is critical to the development of sophisticated, low-cost, and non-invasive approaches for managing severe and challenging wounds, including diabetic ulcers, chronic wounds, and infected wounds. Chronic wounds, which are typified by a delayed healing period and an increased risk of complications, place a heavy strain on individuals as well as healthcare systems that are trying to keep up with the rising expenses of treating them. Venous stasis ulcers, pressure ulcers, and the most prevalent diabetic ulcers are among the disorders classified as chronic wounds5.

Despite the difficulties in locating and guaranteeing the purity of active molecules, a number of clinical trials on herbal products are still accessible. This research offers important insights into the possible advantages and efficacy of employing phytochemicals and plant extracts in wound healing11. As per the mandate of the institute, in this study, efforts have been made to utilize bioassay guided approach to isolate antioxidant and wound healing phytochemicals first time from the Ocimum canum (OC-12). The present communication also describes the docking studies to complement the in vitro and in vivo data and explain the probable mechanism behind wound healing.

Results and discussion

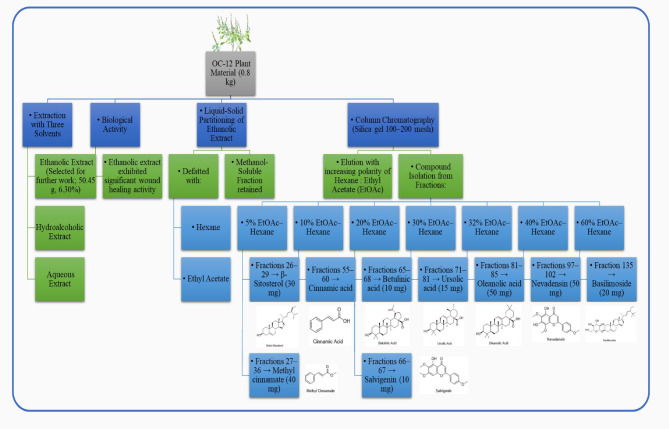

Isolation of compounds from O. Canum

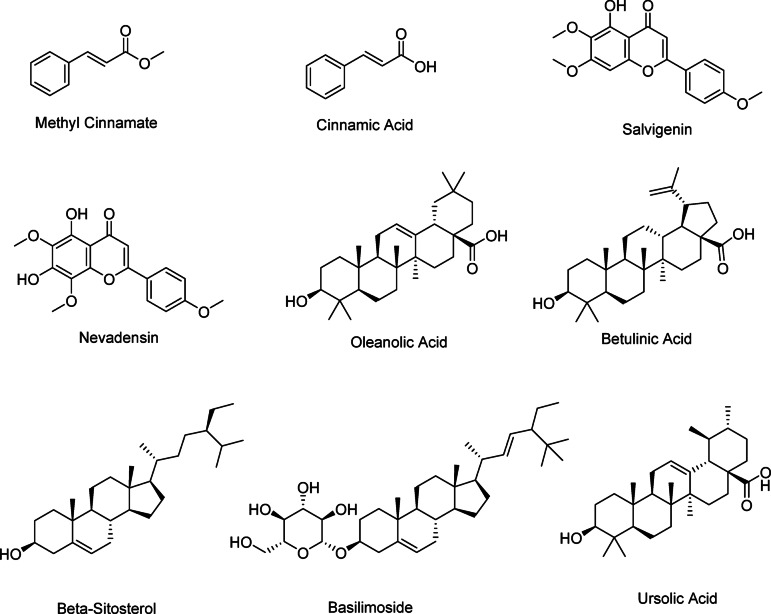

Total nine compounds were isolated (1) Methyl cinnamate (40 mg), (2) beta-Sitosterol (30 mg) (3) Cinnamic acid (4) Betulinic acid (10 mg) (5) Salvigenin (SL) (10 mg) (6) Ursolic acid (15 mg) (7) Olenonic acid (50 mg) (8) Nevadensin (ND) (50 mg) (9) Basilimoside (BS) (20 mg). The chemical structures of the compounds are presented in Fig. 1. The chemical structures of the compounds were assigned on the basis of 1H NMR, 13C NMR, DEPT, Mass values. (Supplementary information S1-S34).

Fig. 1.

The chemical structures of the isolated compounds from Ocimum canum (OC-12).

5,7-dihydroxy-6,8,4’-trimethoxyflavone (1): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.78 (s, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2 H), 7.02 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2 H), 6.59 (s, 1H), 6.55 (s, 1H), 3.97 (s, 3 H), 3.93 (s, 3 H), 3.90 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 182.72, 164.04, 162.62, 158.74, 153.26, 153.08, 132.61, 128.04(2 C), 123.57, 114.53(2 C), 106.16, 104.16, 60.90, 56.33, 55.57. HRMS: 345.0974 (C18H17O7).

5-hydroxy-6,7-dimethoxy-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)−4 H-chromen-4-one (2): 1H NMR (400 MHz, Acetone) δ 12.75 (s, 1H), 7.92 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2 H), 7.01 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2 H), 6.56 (s, 1H), 3.84 (s, 3 H), 3.79 (s, 3 H), 3.75 (s, 3 H). 13 C NMR (101 MHz, Acetone) δ 182.78, 170.10, 163.72, 162.89, 150.61, 148.93, 145.81, 131.57, 128.15, 123.53, 114.61, 103.72, 103.11, 60.94, 59.68, 55.12. HRMS: 329.1013 (C18H17O6).

Methyl cinnamate (3): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.70 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (m, J = 4.8, 2.5, 1.1 Hz, 2 H), 7.44–7.32 (m, 3 H), 6.44 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.44, 144.89, 134.40, 130.31, 128.91(2 C), 128.09(2 C), 117.82, 51.71. GCMS: m/z 162.15.

Cinnamic acid (4): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.14 (s, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 7.59–7.52 (m, 2 H), 7.45–7.33 (m, 3 H), 6.46 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 172.59, 147.15, 134.05, 130.80, 129.00(2 C), 128.41(2 C), 117.34. LCMS: m/z 147.10 (M-H).

Oleanolic acid (5): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 12.00 (s, 1H), 5.21 (t, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 3.15 (t, J = 11.1, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 2.79–2.70 (m, 1H), 1.91 (m, J = 13.4, 4.1 Hz, 1H), 1.82 (m, J = 11.3, 3.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.67 (m, J = 13.3, 8.9, 4.3 Hz, 2 H), 1.57–1.45 (m, 8 H), 1.35 (dd, J = 14.5, 3.0 Hz, 2 H), 1.29–1.22 (m, 2 H), 1.22–1.18 (m, 3 H), 1.13–1.08 (m, 1H), 1.06 (s, 3 H), 1.01 (dd, J = 14.0, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 0.91 (s, 3 H), 0.87–0.83 (m, 9 H), 0.70 (s, 3 H), 0.68 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 183.55, 143.61, 122.64, 79.05, 55.20, 47.63, 46.53, 45.87, 41.58, 40.95, 39.26, 38.76, 38.39, 37.09, 33.79, 33.08, 32.59, 32.44, 30.69, 28.11, 27.68, 27.17, 25.95, 23.59, 23.40, 22.91, 18.29, 17.15, 15.55, 15.33. LCMS: m/z 455.55 (M-H).

Ursolic acid (6): 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO) δ 5.12 (s, 1H), 4.38 (s, 1H), 4.16 (s, 1H), 3.00 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 2.10 (d, J = 11.2 Hz, 1H), 1.91 (d, J = 13.1 Hz, 1H), 1.80 (dd, J = 22.0, 9.2 Hz, 3 H), 1.55 (m, J = 7.0 Hz, 4 H), 1.46 (m, J = 16.2 Hz, 6 H), 1.27 (m, J = 12.7 Hz, 4 H), 1.07–1.01 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 5 H), 0.93–0.84 (m, 9 H), 0.80 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 3 H), 0.74 (s, 3 H), 0.67 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO) δ 178.82, 138.63, 125.05, 77.37, 56.54, 55.26, 52.84, 47.49, 47.30, 42.09, 38.96, 38.92, 38.82, 38.71, 36.97, 36.78, 33.17, 30.64, 28.70, 27.99, 27.38, 24.26, 23.72, 23.31, 21.53, 18.93, 18.45, 17.46, 17.37, 16.51, 15.66. LCMS: m/z 455.55 (M-H).

Betulinic Acid (7): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 4.68 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 4.55 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 3.18–3.07 (m, 1H), 2.98 (m, J = 10.8, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.27–2.16 (m, 2 H), 1.97–1.84 (m, 2 H), 1.65 (m, 5 H), 1.55 (m, J = 11.2, 3.2 Hz, 3 H), 1.46 (dd, J = 13.4, 3.5 Hz, 2 H), 1.43–1.30 (m, 7 H), 1.29–1.20 (m, 3 H), 1.19–1.10 (m, 2 H), 1.03–0.97 (m, 1H), 0.94 (s, 3 H), 0.91 (s, J = 2.1 Hz, 6 H), 0.79 (s, 3 H), 0.71 (s, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 179.04, 150.66, 109.30, 78.57, 56.18, 55.38, 50.53, 46.98, 42.35, 40.61, 38.77, 38.74, 38.26, 37.07(2 C), 34.28, 32.20, 30.49, 29.60, 27.68, 26.77, 25.49, 20.82, 19.01, 18.22, 15.90, 15.70, 15.19, 14.46., HRMS : 455.3523(C30H47O3).

Beta-Sitosterol (8): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.35 (t, J = 5.8, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 3.57–3.51 (m, 1H), 2.33–2.22 (m, 2 H), 2.12–1.92 (m, 2 H), 1.90–1.77 (m, 3 H), 1.67 (m, J = 13.8, 7.4, 7.0, 2.8 Hz, 3 H), 1.55–1.46 (m J = 14.7, 5.7, 2.8 Hz, 6 H), 1.29–1.23 (m, 6 H), 1.19–1.13 (m, 2 H), 1.09–1.05 (m, 2 H), 1.01 (d, 6 H), 0.92 (s, J = 6.6, 2.5 Hz, 3 H), 0.85 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 3 H), 0.82 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 3 H), 0.80 (s, 3 H), 0.69 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 140.76, 121.75, 71.83, 56.77, 56.06, 51.25, 50.13, 45.84, 42.30, 40.52, 39.78, 37.26, 36.52, 36.16, 33.95, 31.91, 31.67, 28.27, 26.06, 25.43, 24.32, 23.07, 21.23, 21.10, 19.84, 19.41, 19.04, 18.79, 12.00, 11.88. LCMS: m/z 397.30 (M + H-H2O).

Basilimoside (9) : 1H NMR (400 MHz, Pyr) δ 5.33 (dd, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 4.56 (dd, J = 11.8, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 4.41 (dd, J = 11.7, 5.2 Hz, 1H), 4.34–4.21 (m, 1H), 4.05 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 3.95 (m, J = 16.6, 6.2, 5.6 Hz, 2 H), 2.72 (dd, J = 14.1, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 2.54–2.40 (m, 1H), 2.17–2.07 (m, 1H), 2.01–1.70 (m, 3 H), 1.61–1.46 (m, 3 H), 1.28 (m, J = 12.1, 6.1 Hz, 22 H), 1.06 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2 H), 0.93–0.77 (m, 18 H), 0.65 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 3 H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, Pyr) δ 140.68, 138.65, 121.73, 102.36, 78.36 (2 C), 77.86, 71.46, 62.61, 56.61, 56.02, 50.12, 45.82, 42.27, 39.73, 39.12, 37.27, 36.71, 36.19, 32.09, 30.08, 29.75, 29.32, 28.35, 26.14, 24.31, 23.17, 22.73, 21.08, 19.79, 19.22, 19.00, 18.81, 14.08, 11.95, 11.77. LCMS: m/z 611.56 (M + Na).

Cell viability/cytotoxicity

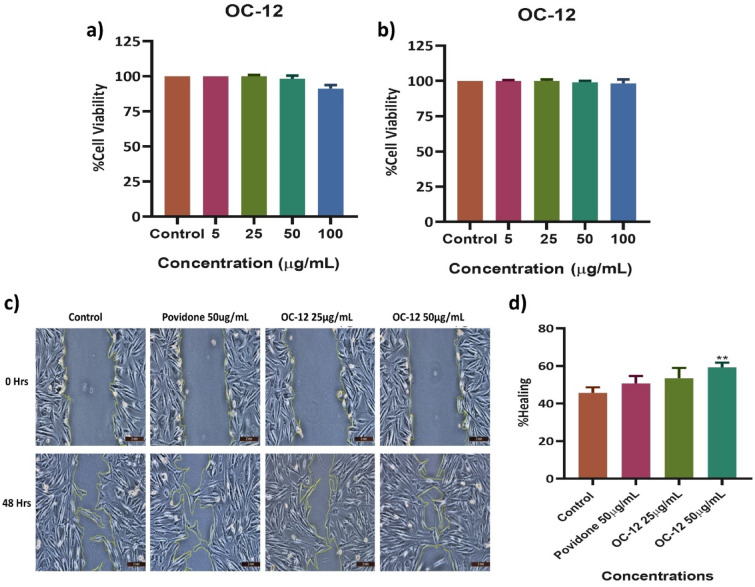

In this study, we investigated the cytotoxic activity of the OC-12 extract on human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) and RAW 264.7 cells using an MTT assay. The effect of OC-12 extract on the cell viability of HDFs at 24 h can be seen in Fig. 2(a). The effect of OC-12 extract on the RAW 264.7 cells at 24 h can be seen in Fig. 2(b).

Fig. 2.

Effect of OC-12 extract on cell viability and Cell migration. MTT assay was performed to check the cell viability of OC-12 extract using HDFs and RAW 264.7 cells at concentrations of 5, 25, 50, and 100 µg/mL after 24 h of treatment. (a) HDFs cells (b), RAW 264.7 cells (c). Images of scratch assay to examine the extent of cell migration in human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) treated with Povidone 50 µg/mL, OC-12 extract 25 µg/mL, and 50 µg/mL at 0 h and 48th hours, viewed under a 10X lens of the inverted light microscope. The yellow line marked area shows the wound area. (d) Bar Graph quantifying the rate of wound closure at 48 h post-treatment. Results were shown as means ± SD (N = 3). Analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA, followed by a Dunnett`s post hoc test. **p < 0.01 compared to Control.

The highest concentration of OC-12 extract (100 µg/mL) showed the lowest cell viability percentage in HDFs cells. The percentage viability for all the concentrations is mentioned in Fig. 2(a). The effect on the viability of raw cells after 24 h of treatment with OC-12 extract is mentioned in Fig. 2(b). The Lowest cell viability was recorded in the highest concentration (100 µg/mL) of OC-12 extract. All the remaining concentrations showed a high cell viability percentage.

Cell migration assay

The In vitro wound healing activity of the OC-12 extract was evaluated by treating the fibroblast cells with the extract concentrations showing no cytotoxicity. The extract at the concentration of 50 µg/mL and 25 µg/mL was decided for treating scratch wounds. The extract was scrutinized for its ability to stimulate fibroblast migration in a scratch assay. 50 µg/mL concentration exhibited the best ability to heal the wound with a migration rate or wound closure of 59 ± 1.5% at 24 h, which was significantly (p < 0.001) better than that of the control untreated group. The wound healing property of povidone was pronounced after 48 h, giving a migration rate of 50 ± 2%. The wound healing effect of extract at 25 µg/ml was 53. ± 1.7%. Povidone as expected indicated better wound healing as compared to the control. Extract at both concentrations showed faster wound healing as compared to the control. The maximum healing percentage was recorded at 50 µg/ml dose of extract. Figure 2c and d.

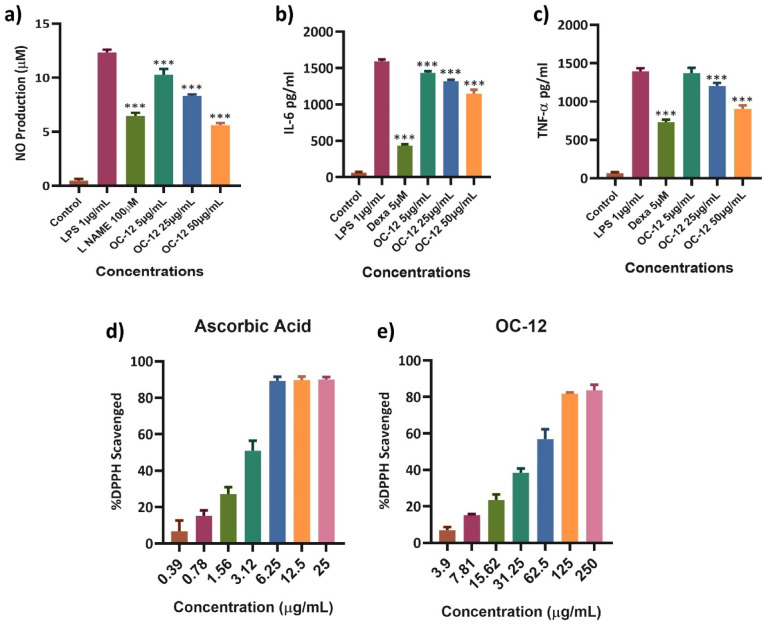

Nitric oxide Estimation

The inhibitory effect of various concentrations of OC-12 extract on Nitric oxide (NO) production was investigated using LPS-activated RAW 264.7 macrophages. The results revealed that NO production was significantly lowered by OC-12 extract in a dose-dependent manner, with greater significant inhibition of 53% at the highest concentration (50 µg), 32%, and 12% at 25 µg and 5 µg concentrations, respectively. L-Name (100µM) used as the positive control also significantly inhibited the NO production. (Fig. 3a) and Fig. S35.

Fig. 3.

Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity of OC-12 extract. a) Nitric Oxide (NO) production was estimated in RAW 264.7 cells treated with various concentrations of the OC-12 extract, followed by LPS stimulation after 1 h of treatment. L-NAME 100µM was used as the positive control. After 24 h, the supernatant was collected for NO estimation. The test drug groups were compared with LPS. All the extract concentrations significantly inhibited NO production. (***p < 0.001). b&c) Inhibition of cytokine expression in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells were measured by ELISA. All three concentrations of extracts and positive control showed highly significant inhibition of IL-6 and TNF-α compared to LPS (***p < 0.001). d, e) The antioxidant activity of the extract was tested using the DPPH radical scavenging assay. Activities were measured for different concentrations of positive control (Ascorbic acid) alongside OC-12 extract. All the data represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 versus LPS group. Significant differences were assessed by using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test.

Estimation of cytokines by ELISA

The ELISA assay was performed to check the cytokines expression for IL-6 and TNF-α. The regulated secretion of these cytokines controls the inflammatory phase and helps in fast wound healing12. Cytokines expression was estimated in LPS induced RAW 264.7 cells treated with various concentrations of OC-12 extract i.e., 5 µg/mL, 25 µg/mL, and 50 µg/mL. Along with Dexamethasone (5µM) as the standard drug (positive Control) while the untreated cell being the normal control. Dexamethasone widely used standard drug has significantly inhibited the pro inflammatory cytokines production. OC-12 extract inhibited the production of IL-6 and TNF-α that suppress the prolonged inflammatory phase thereby accelerating the wound healing process. The observed inhibitory effects extract against IL-6 and TNF-α were maximum at 50 µg/mL concentration (Fig. 3b and c).

DPPH scavenging activity

The radical scavenging activity of OC-12 Extract at different concentrations ranging from 250–3.90 µg/mL was determined using the DPPH scavenging assay. The radical scavenging activity of the extract showed that the OC-12 extract at 250 µg/mL concentration inhibited 83% and 6.88% at the lowest concentration of 3.90 µg/mL with an EC50 value of 51.76 µg/mL Fig. 3e. The positive control (ascorbic acid), which displayed 80–90% DPPH scavenging activity at 10x less concentration range of 25 to 0.3906 µg/mL with an EC50 of 2.682 µg/mL (Fig. 3 d and e).

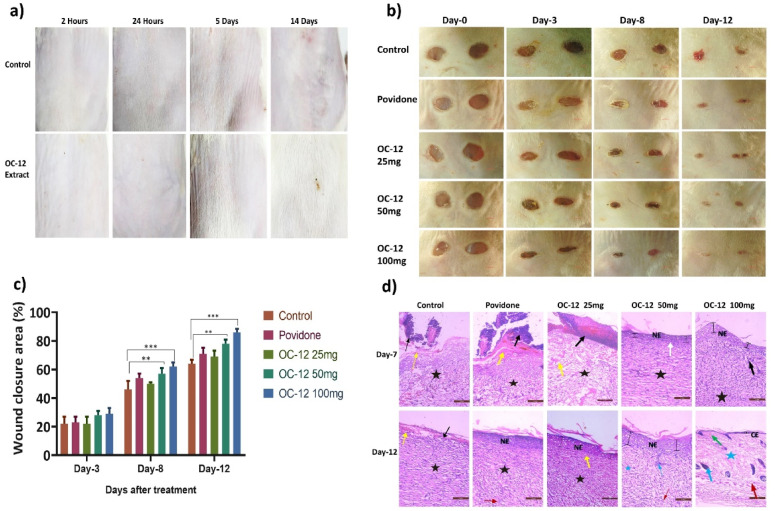

Dermal irritation test

The results of the dermal (skin) irritation test showed that OC-12 extract did not show any skin irritation, as can be seen in the images of the treated skin of the Wistar rats. There was no sign of erythema and edema. This indicates that the topical application of the extract is safe for further studies. (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

a). Dermal (Skin) irritation test performed in Wistar rats to ascertain the toxicity profile of the extract. Images of rat dorsal skin were taken at 2 h, 24 h, 5 days, and 14 days post-application of the test extract. No sign of irritation was observed. b). Representative images of full thickness excisional wound created using biopsy punch and photographed on days 0 3,8, and 12 post-wound creation. Treatment groups include: Control, 5% povidone-iodine ointment, and extract-treated groups (25, 50, and 100 mg/mL). c). Graph showing wound healing percentage on Days 3, 8, and 12 of the experiment. The bar graph represents data presented as mean ± SD (n = 4). Statistical analysis was done using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey`s test. On Day 3, there was no difference observed. However, by Days 8 and 12, we noticed a significant reduction in wound size in the groups that received the 50 and 100 mg/mL extracts when compared to the control group. The results were statistically significant, with p-values: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 compared to the control. d). Hematoxylin-eosin-stained sections of wound tissue collected on days 7 and 12 from all the groups were visualized using an inverted microscope (magnification 20X), and photographs were captured. Histopathological changes observed are marked with different symbols, Black Arrow- inflammation, Red arrow- Blood vessels, Blue- Hair follicle, Green- Collagen, Yellow- Fibrin, Black star- Granulation tissue, NE- Newly formed Epithelium, CE- Complete Epithelium, Blue star- Scar tissue, White arrow: undifferentiated epithelium.

IN-VIVO wound healing

A mouse model of full-thickness wounds was used to evaluate the activity of the extract in vivo. As shown in Fig. 4b, OC-12 extract treatment significantly accelerated the full-thickness wound repair in mice as compared to the normal control group. At days 3, 8, and 12, the wound healing rates observed in extract 100 mg/ml treated mice were 29%, 62% and 86% and the wound healing rates observed in mice treated with a concentration of 50 mg/ml of extract were 28.5%, 57% and 78% respectively. OC-12 extract at both concentrations showed comparable wound healing-promoting capacity to Povidone, a positive control, in a mouse model of dermal full-thickness wounds. Whereas OC-12 extract at a concentration of 25 mg/ml did not show any significant wound healing-promoting effect (Fig. 4b and c) and Fig. S36.

Histopathology study

Hematoxylin-eosin-stained wound tissue sections collected on days 7 and 12 from all the groups.

were visualized using an inverted microscope (magnification 20X), and photographs were captured. On Day 7, it was recorded that the untreated group and the group treated with extract 25 mg/mL concentration showed significant changes, including prominent fibrosis, cellular infiltration, inflammation, and epithelium degradation. The povidone-treated group also exhibited the same pattern. Extract-treated groups (50 and 100 mg/mL) indicated the formation of a distinct newly formed epithelial layer, fewer signs of inflammation, and the presence of granulation tissue. On day 12, it was recorded that distinct epithelial layer formation had taken place in the untreated group and the low-dose extract-treated group, where fibrinogen was replaced by granulation tissue. The 50 mg/mL extract-treated group and the povidone group showed vasculature formation, and a thick and distinct epithelial layer was observed, while scar tissue also started forming. In the 100 mg/mL extract-treated group, complete epithelial structure was restored, granulation tissue was replaced by scar tissue, vasculature and hair follicles were visible, papillary dermis and sebaceous glands were observed. Figure 4d.

Evaluation of isolated compounds from bioactive extract

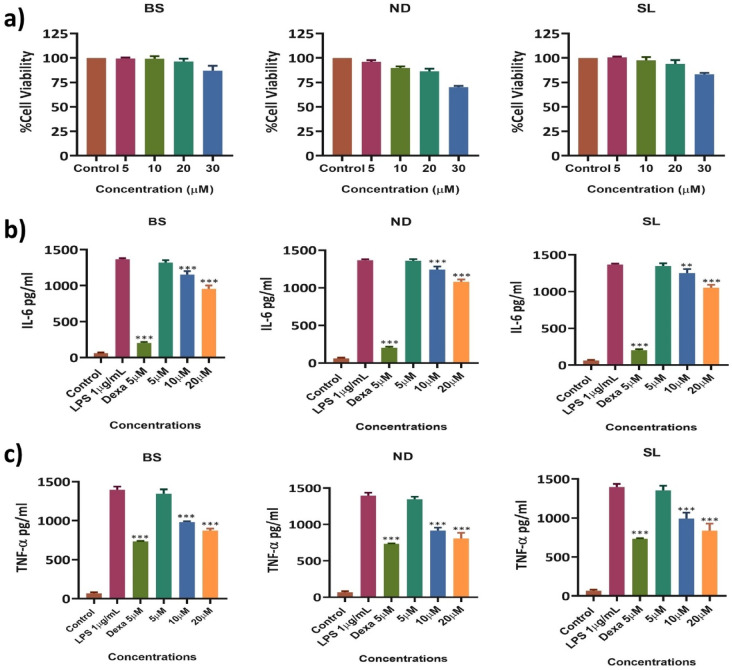

Cell viability/cytotoxicity of the isolated compounds

The cytotoxic activity of the test compounds (Basilimoside (BS), Nevadensin (ND), Salvigenin (SL) was evaluated using RAW 264.7 cells in an MTT assay (Fig. 5a). The test compounds showed the lowest cell viability percentage at the highest concentration (30µM). The viability percentage was 87% in BS, 70% in ND, and 83% in SL at 30µM concentration. At 20µM, percentage viability was recorded as 96% in BS. 89% in ND, and 94% in SL. The viability percentage was recorded in a concentration-dependent manner. 20µM concentration was considered a safe concentration and was taken as the highest concentration for further studies.

Fig. 5.

a). Percentage cell viability of BS, ND, and SL in RAW 264.7 cells at concentrations of 5, 10, 20, and 30µM after 24 h of treatment. b&c). Effect of BS, ND, and SL on the production of IL-6 and TNF-α in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. Cells were pretreated with BS, ND, and SL for 1 h and stimulated for 24 h with LPS. b). IL-6, and c). TNF-α production was determined by ELISA. The results are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. The bar graphs indicate significant differences with asterisks (**p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001) when compared to the LPS control.

Estimation of cytokines of the isolated compounds

To examine the effect of Basilimoside (BS), Nevadensin (ND), and Salvigenin (SL) on the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells (Fig. 5b and c). The cells were treated with various concentrations (5µM, 10µM, and 20µM) of test compounds, with Dexamethasone (5µM) as a positive control. The expression levels of cytokines were measured using ELISA kits. The cells treated with LPS (1 µg/mL) alone showed a marked increase in inflammatory cytokine levels compared to those in the untreated control cells. However, the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α were significantly decreased in the positive control, BS, ND, and SL-treated cells in a concentration-dependent manner. In particular, 20µM, which was the highest treatment concentration, markedly decreased IL-6 and TNF-α expression levels. In LPS-treated cells, the IL-6 and TNF-α production was 1368 pg/mL and 1397 pg/mL, which is considered as 100%, while Dexa showed production of IL-6 203 pg/mL and TNF-α 733 pg/mL, which indicates a highly significant inhibition of cytokine production as expected.

The IL-6 and TNF-α production in BS, ND, and SL treated cells at 20µM concentration, BS showed 955 and 873 pg/mL which indicates 30% and 37% inhibition as compared to LPS, ND at 20 µM concentration showed 1080 and 808 pg/mL which inhibited IL-6 and TNF-α levels by 21% and 42% while SL showed 1052 and 838 pg/mL which inhibited the cytokine growth by 23% and 39% respectively, compared with the LPS alone-stimulated group. The inhibition was recorded in a concentration-dependent manner in all three compounds.

There are several reports on wound healing potential of various extracts of plant and marine origin reveals the inflammation is the one of the important key factor that effect the wound healing process12. Some of the extracts can protect cells from oxidative DNA damage, mitochondrial degradation and thus promote wound healing13. Antioxidant properties of the compounds and extracts also plays crucial role in suppression of ROS production14.

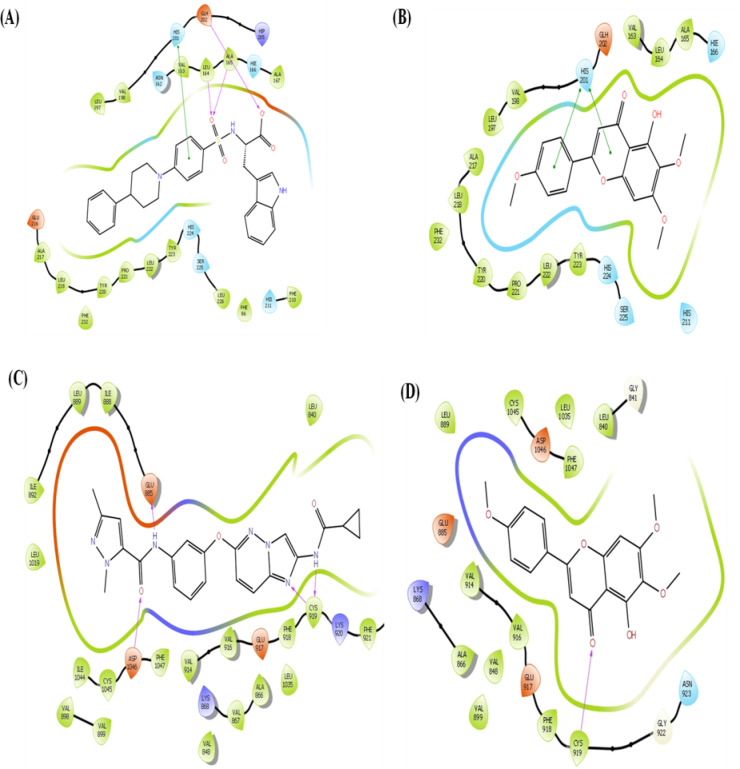

In-silico evaluation of isolated compounds

The binding affinity of all the compounds against different targets enlisted in Table 1. Out of 14 protein targets, compound Salvigenin (SL) and Nevadensin (ND) show higher binding affinity against Matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3) (PDB ID: 1CIZ) with binding free energy of −8.04 kcal/mol and − 7.44 kcal/mol, respectively than the co-crystalize non-peptide inhibitor (PDB ID: DPS, Ki = 36 nM) with − 7.32 kcal/mol. Compound Basilimoside (BS) show binding affinity of −7.01 kcal/mol comparable to co-crystalize inhibitor. The co-crystalized inhibitor (DPS) showed hydrogen bond interactions with LEU 164, ALA 165 and GLH 202 depicted in Fig. 6A. The residue HIS 201 involved in π-π interactions. While compound SL and ND show π-π interactions with HIS 201. Compound ND also show π-π interactions with TYR 223 and hydrogen bond interactions with HIE 166 and GLH 202. These interactions are depicted in Fig. 6B. The MMP-3 is an enzyme involved in extracellular matrix (ECM) remodelling, facilitating the migration of cells by breaking down ECM components15. Proper levels of MMP-3 help clear damaged ECM, enabling new tissue formation. In chronic wounds, MMP-3 is often overexpressed, resulting in excessive ECM breakdown. This destabilizes the wound bed and prevents the formation of new tissue, contributing to a chronic wound state. The MMP-3 inhibitors in chronic wounds can help regulate excessive ECM degradation, creating a stable scaffold for new tissue formation16. The compound SL also show higher binding affinity for Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (PDB ID: 3VO3) with binding free energy − 8.98 kcal/mol than co-crystal inhibitor (PDB ID: 0KF, IC50 = 1.4–1.8 nM) having score of −7.20 kcal/mol. Interactions shown in Fig. 6C. The co-crystallized inhibitor (0KF) showed hydrogen interactions with GLU 885, CYC 919 and ASP 1046, while compound SL showed hydrogen bond interaction with CYC 919 shown in Fig. 6D. The VEGFR-2 is central to angiogenesis, the process of new blood vessel formation, which supplies nutrients and oxygen to the wound site. Activation of VEGFR-2 promotes endothelial cell proliferation and migration, which are necessary for neovascularization in the wound bed17,18. The VEGFR-2 inhibition strategy is commonly applied in the treatment of cancer. The in vitro study suggested inhibition of MMP-3 by compound SL, ND and BS which may be responsible for wound healing process. These compounds bind to MMP-3 with high affinity and inhibition of MMP-3 must be the probable mechanism of action behind wound healing process.

Table 1.

Binding free energy (kcal/mol) of compounds under investigation against various target proteins.

| Compound | EGFR (3W33) | AKT(3QKL) | PIK3C3 (7RSP) | P38 MAPK13 (5EKO) | P38 MAPK11 (3GP0) | P38 MAPK11 (3ZS5) | ERK2 (3SA0) | ERK1 (4QTB) | MMP-2 (7XJO) | MMP-3 (1CIZ) | MMP-8 (4QKZ) | MMP-12 (3F16) | VEGFR-2 (3VO3) | VEGFR-1 (3HNG) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-bound PDB ligand | −12.051 | −10.460 | −8.853 | −8.206 | −10.286 | −10.901 | −7.870 | −11.231 | −9.234 | −7.321 | −7.064 | −7.076 | −7.204 | −10.458 |

| Methyl Cinnamate | −6.104 | −5.251 | −6.662 | −4.380 | −6.507 | −5.543 | −5.703 | −6.008 | −4.769 | −6.051 | −5.322 | −5.228 | −5.296 | −6.341 |

| Cinnamic Acid | −4.999 | −3.683 | −5.618 | −4.294 | −5.299 | −4.695 | −4.541 | −5.669 | −3.351 | −5.259 | −4.611 | −4.703 | −4.785 | −6.057 |

| Salvigenin | −9.038 | −4.767 | −8.339 | −6.822 | −9.111 | −7.202 | −5.120 | −5.579 | −5.544 | −8.048 | −7.059 | −5.235 | −8.983 | −6.01 |

| Nevadensin | −8.805 | −4.982 | −8.150 | −5.788 | −6.109 | −7.695 | −5.221 | −5.861 | −5.219 | −7.443 | −4.981 | −5.338 | −6.671 | −5.349 |

| Oleanolic acid | −5.352 | −4.667 | −4.379 | −5.434 | −5.345 | −2.991 | −5.266 | −4.667 | −4.350 | −4.969 | −4.453 | −3.399 | −3.583 | −4.939 |

| Betulinic acid | −5.428 | −3.501 | −4.347 | −4.328 | −4.021 | −3.176 | −5.020 | −3.424 | −3.594 | −5.454 | −3.647 | −3.355 | −3.406 | −4.951 |

| Beta - Sitosterol | −8.203 | −4.221 | −6.578 | −5.802 | −8.504 | −6.285 | −5.618 | −5.406 | −5.642 | −6.061 | −5.360 | −5.933 | −4.137 | −4.510 |

| Ursolic acid | −5.687 | −4.757 | −4.946 | −5.204 | −5.624 | −3.842 | −5.215 | −5.167 | −4.223 | −5.243 | −4.430 | −3.107 | −4.159 | −4.98 |

| Basilimoside | −7.952 | −7.052 | −7.495 | −6.453 | −7.289 | −7.711 | −4.347 | −7.184 | −6.719 | −7.015 | −6.094 | −5.502 | −4.969 | −4.899 |

EGFR - Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor kinase, AKT - RAC-alpha serine/threonine-protein kinase, PIK3C3 - Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic subunit type 3, P38 MAPK13 - Mitogen-activated protein kinase 13, P38 MAPK11 - Mitogen-activated protein kinase 11,, P38 MAPK14 - Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14, ERK2 - Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1, ERK1 - Mitogen-activated protein kinase 3, MMP-2 - Matrix metalloproteinase-2, MMP-3 - Matrix metalloproteinase-3, MMP-8 - Matrix metalloproteinase-8, MMP-12 - Matrix metalloproteinase-12, VEGFR-2 - Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2, VEGFR-1 - Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1.

In-bound ligand PDB IDs: W19 (3W33), SMR (3QKL), 7IK (7RSP), N17 (5EKO), NIL (3GP0), SB2 (3ZS5), NRA (3SA0), 38Z (4ATB), RYH (7XJO), DPS (1CIZ), QZK (4QKZ), HS3 (3F16), 0KF (3VO3), 8ST (3HNG).

Fig. 6.

(A) The co-crystalize inhibitor (DPS) show hydrogen bond interactions with LEU 164, ALA 165 and GLH 202 (B) Compound ND also show π-π interactions with TYR 223 and hydrogen bond interactions with HIE 166 and GLH 202. (C) compound SL also show higher binding affinity for Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (PDB ID: 3VO3) with binding free energy − 8.98 kcal/mol than co-crystal inhibitor (PDB ID: 0KF, IC50 = 1.4–1.8 nM) having score of −7.20 kcal/mol. (D) The co-crystallized inhibitor (0KF) show hydrogen interactions with GLU 885, CYC 919 and ASP 1046, while compound SL show hydrogen bond interaction with CYC 919.

Materials and methods

NMR

1H NMR spectra were recorded on Brucker-AVANCE DPX FT-NMR 400 and 500 MHz, while13C NMR spectra were recorded at 100 and 125 MHz in CDCl3 and CD3OD. Chemical shifts for protons are reported in parts per million (ppm) downfield from tetramethylsilane (TMS), TMS was used as an internal standard and is referenced to the residual proton in the NMR solvent (CDCl3, 7.26 ppm; CD3OD, 3.31 ppm) and the carbon resonance of the solvent (CDCl3, 77.16 ppm; CD3OD, 49.0 ppm).

General information

The high-resolution mass spectra were obtained using an Agilent 6540 (Q-TOF) high-resolution mass spectrometer in electrospray (ESI MS) mode. All thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on silica gel 60 F254 (0.25 mm thick, Merck), and spots were visualized by UV (254 and 366 nm) and an anisaldehyde reagent was used as the development agent. Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), penicillin, streptomycin, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and Fetal bovine serum (FBS)were purchased from GIBCO USA. The 3(4-5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and 2,2-diphenyl-1picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) were purchased from SIGMA. ELISA kits for TNF alpha and IL-6 were provided by G. Biosciences. The Griess reagent kit was purchased from Invitrogen (USA). The study’s other common compounds were all of the research-grade variety.

Plant material

The weight of dry powdered plant material of OC-12 was 0.8 Kg. The plant material was collected by Dr. Siya Ram Meena with the permission of the Director, CSIR-Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine, Canal Road, Jammu from the Chathta farm of the CSIR-Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine, Canal Road, Jammu and deposited in the herbarium of CSIR-Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine, Canal Road, Jammu (57203). The plant material was identified by the Dr. Sumeet Gairola, Taxonomist at CSIR–Indian Institute of Integrative Medicine, Canal Road, Jammu, India.

Extraction and isolation

Three extracts (Ethanolic, Hydroalcoholic, and Aqueous) were prepared and subjected to wound healing activity. The ethanolic extract exhibited significant Wound healing activity. This extract was further defatted with hexane and ethyl acetate by liquid-solid partition, and the remaining extract was completely soluble in methanol. In detail, the whole dry powdered plant material of OC-12 (0.8 kg) was extracted with ethanol after 24 h, repeated three times at room temperature, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to provide the crude extract (50.45 g, 6.30%). This extract was subjected to column chromatography using silica gel (100–200 mesh) and eluted by increasing the polarity of the elution solvent system of hexanes and EtOAc (100% hexanes to 100% EtOAc), based on their analytical TLC data. The bioassay guided isolation and quantitative distribution of phytochemicals are given in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Scheme of the bioassay guided Isolation, fractionation and Quantitative Distribution of Phytochemicals.

The compound (1) Methyl cinnamate (40 mg) was isolated from fractions 27–36 in 5% EtOAc–hexane.

Compound (2) β-Sitosterol (30 mg) was isolated from fractions 26–29 in 5% EtOAc–hexane.

Compound (3) Cinnamic acid was isolated from fractions 55–60 in 10% EtOAc–hexane.

Compound (4) Betulinic acid (10 mg) was isolated from fractions 65–68 in 20% EtOAc–hexane.

Compound (5) Salvigenin (10 mg) was isolated from fractions 66–67 in 20% EtOAc–hexane.

Compound (6) Ursolic acid (15 mg) was isolated from fractions 71–81 in 30% EtOAc–hexane.

Compound (7) Oleanolic acid (50 mg) was isolated from fractions 81–85 in 32% EtOAc–hexane.

Compound (8) Nevadensin (50 mg) was isolated from fractions 97–102 in 40% EtOAc–hexane.

Compound (9) Basilimoside (20 mg) was isolated from fraction 135 in a 60% EtOAc–hexane solvent system (Please see Supplementary Information for column chromatography Fig. S37–S46).

Biological activity

Cell culture

Human dermal fibroblasts and Raw 264.7 cells procured from National Centre for Cell Sciences (NCCS, Pune, India) were cultured in high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% FBS, 1% sodium bicarbonate,1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution. Cells were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere using an Eppendorf Galaxy 170 s CO2 incubator. Cells were cultured in a T75 flask. The culture’s media was replaced every 48 to 72 h, and cells were observed under the Leica DMi-1 inverted microscope.

Cell viability

MTT (3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)−2, 5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay was performed to evaluate the cell viability at various concentrations of the Extract. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates with a seeding density of 10,000 cells per well, and the plates were incubated for 24 h before treatment. After 24 h, the cells were treated with different concentrations of the extract, i.e., 5 µg/mL, 25 µg/mL, 50 µg/mL, and 100 µg/mL. Whereas the control well contains only media supplemented with 10% FBS. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere for 24 h. After the incubation, 20 µl of 2.5 mg/ml of MTT solution was added to each well, including the control wells, and the plates were again incubated for 3 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Followed by 4 h of incubation, the previous media was discarded, and 200 µl DMSO was added to each well. The formazon product thus formed was measured at 570 nm using a spectrophotometer.

Cell migration assay

Human Dermal Fibroblasts (HDFs) cells were seeded in 6 well cell culture plates at a density of 2lakh cells/well. The plates were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. After the formation of the monolayer, the cells were washed with PBS. A scratch was made in a monolayer with the help of a 200 µl sterile pipette in each well. The cells were again washed to remove the debris. Then 2 ml of fresh medium was added to each well, and each well was photographed using an inverted microscope equipped with a camera. The cells were then treated with 25 µg/mL and 50 µg/mL concentrations of OC-12 extract. The untreated wells were kept as a normal control. Povidone (50 µg/mL) treated wells were kept as a positive control. The plate was then incubated again for 48 h. After the incubation, the plate was observed using a microscope, and photographs were captured. The percentage of migration was then evaluated and calculated by using Image J software. The wound area was calculated by using the formula:

Where A (t) is the wound area at time t and A(0) is its initial area. The migration rate is then indirectly evaluated as the percentage of wound area at a specific time point.

Estimation of inflammatory cytokines by ELISA

To evaluate the production or inhibition of cytokines IL-6, and TNF-α, in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced RAW 264.7 cells by the extract, the ELISA assay was performed. The cells were seeded in 96 well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well. The plates were incubated at 37 °C degrees with 5% CO2 in the humidified atmosphere for 24 h. After incubation, the cell was treated with different concentrations of extract 5, 25, and 50 µg/mL, and the plates were again incubated for 1 h. Post one hour incubation the cells were stimulated with LPS 1 µg/mL in each well except control wells and the plate was incubated for 24 h. After incubation, the supernatant was collected and the expression of cytokines was assessed by using the ELISA kits IL6, and TNF-α. The experiment was conducted in triplicate. Dexamethasone (5µM) was considered as positive control. The rest of the procedure was followed as per the protocol provided with kit. The absorbance was taken by a microplate reader.

Nitric oxide estimation

This study investigates the influence of OC-12 on nitrite production in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. To this end, cells were cultured at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well in 96-well plates and maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 overnight in a humidified incubator. Following incubation, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium, and cells were subjected to varying concentrations of OC-12 extract (5 µg, 25 µg, and 50 µg), with L NAME (100µM) as a positive control and untreated cells as a normal control. After one hour of treatment, LPS was administered to stimulate the cells, and the plates were returned to the incubator for an additional 24 h. Nitric oxide levels were quantified using an Invitrogen nitric oxide kit. The assay procedure was conducted in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Specifically, 100 µL of samples were mixed with 80µL of demineralized water and 20 µL of Griess reagent solution in a 96-well plate. The plate was then incubated in the dark for 10 min, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a Tecan plate reader. The quantification of nitrite levels was achieved by reference to a standard curve.

DPPH scavenging activity assay

Free radical scavenging activity of the extract was done using the 1‑Diphenyl‑1‑2‑picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Assay. The extract was reconstituted in methanol to obtain the initial concentration of 1 mg/mL; similarly, ascorbic acid was also reconstituted in methanol. The final extract concentrations were 250 µg, 125 µg, 62.5 µg, 31.25 µg, 15.625 µg, 7.81 µg, and 3.90 µg while the concentrations for Ascorbic Acid were 25 µg, 12.5 µg, 6.25 µg, 3.125 µg, 1.5625 µg, 0.781 µg and 0.390 µg. The plates were then incubated for 30 min. After incubation, the absorbance was taken at a wavelength of 517 nm using a microplate reader. DPPH scavenging percentage was calculated using the formula.

DPPH scavenging percent (%) = [Control A0 −sample A1/control A0 ×] 100

Where control A0. And sample A1. Are absorbance of the DPPH without the extract and DPPH with the extract, respectively.

Dermal Irritation Test

Dermal (skin) irritation test was performed in Wistar rats according to the OECD guidelines 404. Animals were divided into two groups of five animals each. Hair was removed from the dorsal surface of all the animals, and the animals were left undisturbed for the next 24 h. One group was considered the control group, while the other group was treated with extract. The extract was applied evenly on the shaved skin. The skin was observed after 2 h, 24 h, and 72 h; the control group received sterile water, which was also held with adhesive tape. Observation of any signs of irritation like erythema and edema was made for 14 days.

Excisional wound healing study

Male Balb/c mice (5–6 weeks old) were obtained from the CCSEA (CPCSEA) registered Animal House Facility of CSIR IIIM Jammu. The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (Approval No. IAEC/354/83/23). Animals were kept under standard conditions at a temperature between 22 and 25 °C under 12 h of light/dark cycles. Mice were fed with commercial rat feed (pellets) and water. All of the procedures were performed in accordance with the local institutional guidelines. 35 animals were grouped into 5 groups (7 animals per group): Normal control, Positive control (Povidone 5%), OC-12 100 mg/mL, OC-12 50 mg/mL, and OC-12 25 mg/mL. The mice were anaesthetized using an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (50 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). Their dorsal skin was shaved and sanitised with 70% ethanol. Two 5-mm full-thickness wounds were created in their dorsal skin by using a sterile biopsy punch. The test drugs were applied topically with a sterile swab on a daily basis for 12 days. The wound area was measured using a digital vernier caliper and determined by taking pictures of the wounds19.

The experiment was conducted on all 35 animals (n = 7) in each group (n = 5) up to 12 days. On day − 7, 3 animals from each group were sacrificed for histopathological analysis. The remaining four animals were used for wound size measurement and photographed.

The percentage wound contraction was estimated as the percentage of the reduction in the original wound size. Percentage wound contraction was calculated as:

%Wound contraction = Wound area on day 0 -Wound area on nth day/Wound area on day 0 × 100.

Where n = number of days (0, 3, 8, and 12). During wound healing, the period of epithelialization was also measured. This represents the number of days taken for complete healing20.

Histology and microscopy

On Days 7 and 12, animals were sacrificed and wound tissues were collected for histological and molecular analyses. Full-thickness skin tissue was then fixed in 4% formalin solution (Sigma) overnight and dehydrated for embedding in paraffin. Tissues were sectioned at 5 μm thickness, mounted on glass slides, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and digital photomicrographs were taken from the representative area using a Leica DMi1 inverted microscope.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using Graph Pad Prism software (Microsoft, San Diego, CA, USA) version 8 and were expressed as Mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s posthoc test was used to compare control group and treated group. A P-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In-silico method

Total 14 target protein involved in wound healing process, investigated using molecular docking enlisted in supplementary file. Ligand structures obtained from plant extract of OC-12 were drawn manually using ChemDraw21. The compounds were saved in SDF format and converted to PDB format using Open Babel22. Energy minimization was performed using the MMFF94 force field in Open Babel to optimize ligand geometry. Finally, the ligands were converted to the PDBQT format using AutoDock Tools23. The 3D structure of the target proteins was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank. Water molecules and non-essential ions were removed using PyMOL24. Missing residues, if any, were modeled using Swiss-PDBViewer25. Polar hydrogens were added, and the Kollman charges were assigned using AutoDock Tools23. The prepared protein structure was saved in the PDBQT format. The binding site was determined based on known ligand-binding sites or active site residues. A grid box was centred at the binding site, and its dimensions were set to encompass the active site residues fully. Grid box parameters were generated for docking keeping co-crystallize ligand at centre. Docking simulations were performed using AutoDock Vina26. The docking protocol involved setting the exhaustiveness at 8 to balance accuracy and computational efficiency. The command-line interface was used to execute docking, and the parameters were specified in a configuration file. Docking results were analyzed based on binding affinity values (in kcal/mol). The conformation with the lowest binding energy was considered as the best pose. The interactions between the ligand and the protein were visualized using PyMOL24. And Desmond27 to identify key hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and other non-covalent interactions. The docking protocol was validated by relocking a co-crystallize ligand into the active site and calculating the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the experimental and docked poses. An RMSD value of < 2 Å was considered acceptable.

Conclusion

The extract exhibited faster wound closure (Wound healing) activity further antioxidant and inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines, Nitric oxide inhibition, cell migration indicates that the extract showing wound closure activity due to its effect on inflammatory phase of wound healing process. This may be due to the presence of phytochemicals such as Methyl cinnamate, beta-Sitosterol, Cinnamic acid, Betulinic acid, Salvigenin, Ursolic acid, Olenonic acid, Nevadensin, and Basilimoside.

The effect of Basilimoside (BS), Nevadensin (ND), and Salvigenin (SL) on the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF- in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells was evaluated which reveals that the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α were significantly decreased in the BS, ND, and SL-treated cells in a concentration-dependent manner.

Docking studies complement the in vitro study data and explain probable mechanism behind the wound healing by compounds SL, ND and BS through inhibition of MMP-3. This needs to be further investigated by in vivo studies. Docking studies also indicate Salvigenin (SL) can be investigated for role in cancer therapeutics due to high affinity for VEGFR-2.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Director, CSIR-IIIM, Jammu for providing necessary facility during the course of study. Authors also acknowledge funding from CSIR-Aroma Mission Project HCP-0007. Author (Arfan Khalid) would like to thank UGC and AcSIR for granting UGC- fellowship for Ph.D program and Academy of Scientific and Innovative Research (AcSIR), Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh- 201 002, India for getting registered in the Ph.D program.

Author (Sagar Bhayye) acknowledge DBT Builder Scheme No. BT/INF/22/SP41297/2021, Dept. Of Science and Technology, Govt. Of India for providing computational facility.

Institutional Publication Number: CSIR-IIIM/IPR/00868.

Author contributions

AK, Bioactivity of pure compounds & extracts, Equal contributions JPB, Extraction and Isolation of Pure compounds Equal contributions RS, Extraction and Isolation of Pure compounds Equal contributions MM, Extraction and Isolation of Pure compounds AP, Bioactivity of pure compounds & extracts YKN, Extraction and Isolation of Pure compounds Equal contributions SRM, Plant material & identification of the plant GY, Supervision of Bioactivity of pure compounds & extracts SB Insilico analysis of pure compounds ZA, Supervision of Bioactivity of pure compounds & extracts MKV, Designed the overall study & Characterization of pure compounds & supervision, Manuscript writing & editing.

Data availability

All the data generated for this study are available in the supplementary files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Experiments were approved and then performed in compliance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC), Its approval No. IAEC/354/83/23. The study reported in accordance with CCSEA (Committee for control and supervision of experiment on animals)/CPCSEA guidelines.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Supplementary Information

1H NMR, 13C NMR, DEPT and MS data of the isolated compounds are given in the supplementary files.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Arfan Khalid, Jayaprakash Behera and Rohit Singh.

References

- 1.Tsala, D. & Emery Dawe amadou, and Solomon habtemariam. ‘Natural wound healing and bioactive natural products’. Phytopharmacology4, 532–560 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avishai, E. & Yeghiazaryan, K. Olga golubnitschaja. ‘Impaired wound healing: facts and hypotheses for multi-professional considerations in predictive, preventive and personalised medicine’. EPMA J.8, 23–33 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh, M. et al. ‘Innovative approaches in wound healing: trajectory and advances’, Artificial cells, nanomedicine, and biotechnology, 41: 202 – 12. (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Alavi, A. et al. Kirsner. ‘Diabetic foot ulcers: part I. Pathophysiology and prevention’. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.70, 1 (2014). e1-1. e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agale Shubhangi Vinayak ‘Chronic leg ulcers: epidemiology, aetiopathogenesis, and management’, Ulcers, 413604. (2013).

- 6.Saleem, A., Saleem, M., Akhtar, M. F., Ashraf Baig, F., Rasul, A. & M. M., & HPLC analysis, cytotoxicity, and safety study of Moringa Oleifera lam. (wild type) leaf extract. J. Food Biochem.44 (10), e13400. 10.1111/jfbc.13400 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Governa, P., Carullo, G. & Biagi, M. Vittoria Rago, and Francesca Aiello. ‘Evaluation of the in vitro wound-healing activity of calabrian honeys’, Antioxidants 8: 36. (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Farahpour, M. R. & Hamishehkar, H. Effectiveness of topical Caraway essential oil loaded into nanostructured lipid carrier as a promising platform for the treatment of infected wounds. Colloids Surf., A. 610, 125748 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manzoureh, R. & Farahpour, M. R. Topical administration of hydroethanolic extract of trifolium pratense (red clover) accelerates wound healing by apoptosis and re-epithelialization. Biotech. Histochem.96, 276–286 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choudhary, D., Sahu, R. & Kaithwas, G. Ocimum species: A review on phytochemistry and Pharmacology. Indian J. Nat. Prod. Resour.6 (2), 132–141 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kmail, A., Said, O. & Saad, B. How thymoquinone from Nigella sativa accelerates wound healing through multiple mechanisms and targets. Curr. Issues. Mol. Biol.45, 9039–9059 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holzer-Geissler, Judith, C. J. et al. Barbara Wolff-Winiski, and Hermann Fahrngruber. ‘The impact of prolonged inflammation on wound healing’, Biomedicines, 10: 856. (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Mazumder, B. et al. Sea cucumber-derived extract can protect skin cells from oxidative DNA damage and mitochondrial degradation, and promote wound healing. Biomed. Pharmacother. 80, 117466 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.More, G. K. & Raymond, T. Makola. In-vitro analysis of free radical scavenging activities and suppression of LPS-induced ROS production in macrophage cells by solanum sisymbriifolium extracts. Sci. Rep.10 (1), 6493 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caley, M. P., Martins, V. L. C. & O’Toole, E. A. Metalloproteinases and wound healing. Adv. Wound Care. 4 (4), 225–234. 10.1089/wound.2014.0581 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tardáguila-García, A. et al. Metalloproteinases in chronic and acute wounds: A systematic review and Meta‐analysis. Wound Repair. Regeneration. 27 (4), 415–420. 10.1111/wrr.12717 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bao, P. et al. The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in wound healing. J. Surg. Res.153 (2), 347–358. 10.1016/j.jss.2008.04.023 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tonnesen, M. G., Feng, X. & Clark, R. A. F. Angiogenesis in Wound Healing. Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings 5 (1), 40–46. (2000). 10.1046/j.1087-0024.2000.00014.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Thangavel, P., Ramachandran, B., Chakraborty, S. & Kannan, R. Suguna lonchin, and vignesh muthuvijayan. ‘Accelerated healing of diabetic wounds treated with L-glutamic acid loaded hydrogels through enhanced collagen deposition and angiogenesis: an in vivo study’. Sci. Rep.7, 1–15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon, Y. et al. Youngjae ryu, and Hyeona kang. ‘N-acetylated proline-glycine-proline accelerates cutaneous wound healing and neovascularization by human endothelial progenitor cells’. Sci. Rep.7, 1–13 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cousins, K. & ChemOffice Plus A package of programs for chemists. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci.33 (5), 788–789. 10.1021/ci00015a603 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Boyle, N. M. et al. Open babel: an open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform. 3 (1), 33. 10.1186/1758-2946-3-33 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huey, R. & Morris, G. M. AutoDock Tools (The Scripps Research Institute, 2003).

- 24.DeLano, W. L. & Pymol An Open-Source molecular graphics tool. CCP4 Newsl. Protein Crystallogr.40 (1), 82–92 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guex, N., Peitsch, M. C. & Schwede, T. Automated comparative protein structure modeling with SWISS-MODEL and Swiss‐PdbViewer: A historical perspective. Electrophoresis30 (S1). 10.1002/elps.200900140 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock vina: improving the speed and accuracy of Docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem.31 (2), 455–461 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D. E. Shaw Research. Desmond Molecular Dynamics System. (2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data generated for this study are available in the supplementary files.