Abstract

Background

This research work aimed to study the parasite clearance of two commonly prescribed artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) in under-five children with uncomplicated malaria in a comprehensive healthcare facility in Southwestern Nigeria.

Methods

An open-label, randomised controlled clinical trial was conducted. The participants were randomised into two treatment groups using simple randomisation by computer-generated random numbers. Children between the ages of six and 59 months with uncomplicated malaria in a comprehensive healthcare facility in southwestern Nigeria were enrolled after fulfilling the study criteria between July 2020 and December 2020. They had either artemether-lumefantrine (AL) or dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine phosphate (DHAPQ) for three days. The participants were monitored for 42 days by examining blood films for malaria parasite density on days 1, 2, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42. Malaria parasite genotyping by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was done to differentiate between reinfection and recrudescence. The main outcome measures were malaria parasite clearance, adequate clinical and parasitological response on days 28 and 42 (ACPR28 and ACPR42), and tolerability.

Results

A total of 122 participants were randomised to receive either AL (61 participants) or DHAPQ (61) with a mean age of 23.6 ± 13.0 (months) and 27.6 ± 16.6 (months), respectively. Day 42 per protocol analysis included 113 participants – 57 in the AL group and 56 in the DHAPQ group after excluding the nine that were lost to follow-up. Although not statistically significant, the median baseline malaria parasite density of participants in AL group was higher than that in the DHAPQ group (3,600.0 parasite/µL, lower quartile (LQ) 2,420 parasite/µL, upper quartile (UQ) 5,399 parasite/µL versus 3,440.0 parasite/µL, LQ 2,640 parasite/µL, UQ 5,597 parasite/µL; p = 0.636). The mean fever clearance time was significantly lower in the AL group compared to the DHAPQ group (46.16 ± 3.31 h vs. 48.83 ± 8.95 h; p = 0.032). Parasite clearance time was shorter in the AL treatment group compared to DHAPQ (61.30 ± 23.75 h vs. 63.97 ± 23.42 h; p = 0.541), but this difference was not statistically significant. The day 42 PCR uncorrected cure rate in the AL group and DHAPQ group was 94.7% and 92.9% respectively (p = 0.679). The cure rate increased to 100% in both groups after PCR correction. Five participants in the DHAPQ group reported mild adverse events compared to none of those in the AL group.

Conclusion

The study concluded that both DHAPQ and AL had good parasite clearance.

Trial registration

Registered on 10/07/2020 with the Pan African Clinical Trials Registry, Cochrane South Africa (PACTR202007553348930).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12879-025-11704-w.

Keywords: Plasmodium (P.) falciparum, Parasite clearance, Artemisinin combination therapy, Artemether-lumefantrine, Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine phosphate

Introduction

Artemisinin-based combination therapies, which are the first-line antimalarials, have been known to have fast malaria parasite clearance [1]. There are, however, reports of artemisinin-resistant malaria in Southeast Asia [2–4]. The resistance resulting from mutations in the Plasmodium (P.) falciparum K13 (pfkelch13) gene is associated with delayed parasite clearance and a high rate of treatment failures with recrudescent infections [5]. Similar artemisinin resistance in infections by P. falciparum, causing treatment failure, had been reported in Rwanda, Uganda, Tanzania, and Eritrea [6–9]. Reduced therapeutic efficacy of AL and DHAPQ as low as 74% and 84% respectively, has been reported in Burkina Faso [10]. There are also reports of early malaria treatment failures, which may be due to delayed parasite clearance in Nigeria [11, 12]. It is, however, not known if artemisinin resistance has spread to Nigeria.

Malaria transmission is high in Nigeria. Under-five children are particularly more prone to malaria and its severe forms because of the loss of the inherited passive immunity from their mother and inadequate acquired partial immunity. The rate of movement of residents of Nigeria across international boundaries is also high [13], increasing the probability of importation of ACT-resistant strains of P. falciparum into the country. Recent research shows that resistance is becoming a greater concern in Africa, even if the confirmed K13 variants that are strongly linked to delayed parasite clearance have not been extensively documented or are not very common in Nigeria. For example, it has been confirmed that the R561H mutation is arising and expanding clonally in Rwanda, which is a serious problem for the continent [14]. A legitimate worry that calls for constant monitoring is the possibility of comparable de novo development or geographic expansion from other African locations or even from outside the continent via human movement. Many of the mutations found in Africa are novel and have emerged independently, while some validated Asian mutations are present at low frequencies, according to recent multicentre studies and meta-analyses that tracked the spread of particular parasite lineages using molecular techniques like Identity by Descent [15, 16]. This is an important finding since it implies that artemisinin resistance in Africa may evolve locally. In addition, drug pressure from the widespread use of ACTs [17] and the use of sub-standard and counterfeit ACTs in Nigeria [18] are possible causes of a gene mutation that can cause the resistance of P. falciparum to widely used ACTs.

When widespread resistance to previous antimalarial medications like sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and chloroquine developed in 2005, Nigeria, in accordance with WHO guidelines, commenced the use of ACTs for the treatment of uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria. According to the original policy, the Nigerian Malaria Eradication Programme chose AL as the first-line antimalarial medicine [19]. The country then updated its treatment guidelines in 2009 to incorporate artesunate-amodiaquine, DHAPQ, and artesunate-mefloquine as second-line alternatives in situations where AL was unavailable or where therapy with the first-line medication had failed [20]. This dual-ACT policy, which has different partner drugs, guarantees therapy availability and offers a way to monitor possible drug resistance is still the current treatment guideline in Nigeria [21].

The rate at which malaria parasites are cleared is an integral determinant of the therapeutic efficacy of antimalarial drugs, and this, in turn, can be used to assess artemisinin resistance in vivo [22]. Even as what occurs presently is still partial Artemisinin resistance [23], partner drug resistance must be monitored and forestalled by routinely evaluating the therapeutic outcome of malaria treatment with ACTs [24]. A therapeutic efficacy trial seeks to know the number of patients with microscopic evidence of malarial parasitaemia on day 3 of treatment and the number of treatment failures by day 28 or 42 [24, 25]. Although a therapeutic efficacy of these ACTs was conducted by the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health in 2018 [26], there is a need for continuous monitoring of the efficacy of ACTs to detect any emergence of resistance and treatment failures. This is in line with the requirement of biennial therapeutic efficacy studies to assess the parasite clearance of ACTs in malaria-endemic regions like Nigeria, made by the World Health Organisation [24].

This study tried to address this gap in knowledge by determining the parasite clearance of AL and DHAPQ, the two most commonly prescribed ACTs in Nigeria [27]. We decided to compare DHAPQ with AL because it has gained wider acceptance in treating uncomplicated malaria, partly due to its simple single-daily dosing and an extended half-life of piperaquine that may confer longer post-treatment prophylaxis [28]. It also compared the therapeutic efficacy and tolerability of the two ACTs. Parasite clearance of the ACTs is mediated by the drug efficacy and the host immune system, which are also moderated by the malaria parasite’s resistance to the drug [23]. Monitoring the emergence of resistance to ACTs using their parasite clearance can be done by assessing their fever clearance time, parasite clearance time, and day-3 parasite positivity [25]. Delayed or ineffective parasite clearance will result in treatment failure instead of an adequate clinical and parasitological response [23]. The study aimed to determine the parasite clearance of two commonly prescribed ACTs in under-five children with uncomplicated malaria. We hypothesised that there is no statistical difference in the parasite clearance rates of the two commonly administered ACTs in under-five children with uncomplicated malaria.

Methods

Study design

This was an open-label, parallel, randomised controlled clinical trial.

Study site

It was conducted between July 2020 and December 2020 at the Urban Comprehensive Health Centre of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile-Ife, Osun State, in South-Western Nigeria. Ile-Ife is situated in the rainforest belt of South-Western Nigeria. Malaria transmission in South-Western Nigeria is classified by the WHO as endemic, meaning that it occurs year-round [29]. A favourable tropical climate with high temperatures and heavy rainfall, which provides the perfect environment for the Anopheles mosquito vector to grow year-round, is what causes the region’s high malaria load. The prevalence among under-five children in South-Western Nigeria is 22% according to the 2021 Nigeria Malaria Indicator Survey [19]. This suggests a substantial and ongoing disease load in the area. The predominant parasite species, P. falciparum, is responsible for the majority of malaria cases.

Study participants and eligibility criteria

Children between the ages of 6 months and 59 months with uncomplicated malaria were included in the study. A diagnosis of uncomplicated malaria was made when the child presented with any of the following clinical features: an axillary temperature of ≥ 37.5 °C or a history of fever in the preceding 24 h. Additionally, symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, nasal discharge, headache, joint pain, abdominal pain, and weakness or reduced activity were considered. This diagnosis also required a confirmed P. falciparum mono-infection, with a parasite density count between 2,000 and 200,000 parasites/µl, determined by viewing Giemsa-stained thick and thin peripheral blood smears under the microscope. Finally, the child needed to be able to swallow oral medication. Patients with sickle cell anaemia, severe malnutrition, severe malaria, acute lower respiratory tract infection that requires antibiotic therapy, and a history of hypersensitivity to any of the study drugs were excluded from the study.

Sample size determination, sampling procedure, and randomisation of study participants

The sample size was calculated using the formula for comparing two independent proportions as described by Noordzij et al. [30] .Where n represents the sample size in each of the groups; p1 is the cure rate of AL from a previous study; q1 is the failure rate of AL, which is calculated as (1 − p1); p2 is the cure rate of DHAPQ; q2 is the failure rate of DHAPQ, calculated as (1 − p2); and x denotes the difference to be detected. The intended difference in the event rate was 10%. Using the treatment failure rates of 4.5% and 2.7% for AL and DHAPQ, respectively [31], a minimum sample size of 55 patients was required to reach a 95% confidence level and a precision of 5% for each arm of the study with a statistical power of 80%. The number of study participants was increased to 61 patients per study arm to account for a 10% loss to follow-up and withdrawals during the 42-day follow-up period.

.Where n represents the sample size in each of the groups; p1 is the cure rate of AL from a previous study; q1 is the failure rate of AL, which is calculated as (1 − p1); p2 is the cure rate of DHAPQ; q2 is the failure rate of DHAPQ, calculated as (1 − p2); and x denotes the difference to be detected. The intended difference in the event rate was 10%. Using the treatment failure rates of 4.5% and 2.7% for AL and DHAPQ, respectively [31], a minimum sample size of 55 patients was required to reach a 95% confidence level and a precision of 5% for each arm of the study with a statistical power of 80%. The number of study participants was increased to 61 patients per study arm to account for a 10% loss to follow-up and withdrawals during the 42-day follow-up period.

Of the 318 patients screened for eligibility, 22 declined consent, 174 were excluded (concomitant lower respiratory tract infection = 31, severe malaria = 102, severe malnutrition = 18, sickle Cell Anaemia = 11, history of hypersensitivity to DHAPQ = 12), and 122 were enrolled in the study. The children whose caregivers declined consent and those who were ineligible were evaluated and treated appropriately. All consecutive eligible patients with uncomplicated malaria were enrolled on the study after their primary caregivers had provided written informed consent. Patients were randomised into the treatment groups using simple randomisation by computer-generated random numbers by the principal investigator in the ratio of 1:1. The allocation sequence was concealed in 122 sealed opaque brown envelopes containing cards of similar size, each placed in a box. Each primary caregiver was allowed to pick an envelope from the box after informed consent had been obtained. The envelope was opened to disclose the treatment by the research assistant who administered the treatment.

Data collection

All clinical and laboratory data were recorded on each of the follow-up days by the study physicians on the case report forms (S5 File) developed in line with the World Health Organisation proforma for antimalarial therapeutic efficacy trials [25]. Data collected for each participant were age (at last birthday), sex, weight, height, mid-upper arm circumference, axillary temperature (measured with a mercury thermometer (U-MECR) to the nearest 0.1ᵒC), history of fever in the preceding 24 h, and laboratory parameters, which include haemoglobin concentration and malaria parasite densities.

The anthropometric measurements of participants were taken by the researchers or their trained research assistants. Weight was measured using a calibrated Hana® bathroom scale. Children who were unable to stand were weighed while naked with their caregiver, and the caregiver’s weight was then subtracted to determine the child’s weight. The scale was zeroed before each measurement. Height was measured in centimetres using a wall-mounted tape, or length (from occiput to heel) for children who could not stand. Mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) was measured using a Shakir’s strip at the midpoint of the left arm’s acromion and olecranon processes. MUAC values were categorised as normal nutritional status (≥ 12.5 cm, green), moderate malnutrition (< 12.5 cm to 11.5 cm, yellow), or severe malnutrition (< 11.5 cm, red).

Laboratory procedures

From a single sterile finger prick, one drop of capillary blood was collected in the centre of a labelled microscope glass slide and two drops on another slide for a thin and thick film for malaria parasite, respectively. Another drop of blood was placed on the strip of a portable Mission Hemoglobinometer® to determine the haemoglobin concentration. Two drops each of capillary blood were also blotted at two different spots on a Whatman™ 3 MM® filter paper (Sigma-Aldrich Inc., St. Louis, MO) for Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) analysis. The air-dried filter papers were placed in separate polythene envelopes containing a silica gel pouch and stored in a cool, dry place until the samples were analysed.

Thin and thick films for malaria parasites were prepared, fixed and stained by the two study microscopists [25]. The microscopists examined each slide independently using a light microscope at a magnification of ×1000. The parasite density was obtained by finding the average of the two counts. In case of discordance of > 25% in the parasite density, the slide was re-examined by a malaria parasitologist. The parasite density was determined as the average of the two most consistent counts. The asexual parasite density was estimated by dividing the number of observed asexual parasites by the number of white blood cells (WBCs), and multiplying the result by an assumed normal WBC level of 8,000/l of blood [25]. A slide was deemed to be parasite-negative after 200 microscope fields were examined, and no parasite was detected [25]. After allocating the participants into treatment categories, the microscopists were blinded to treatment allocation.

Drug administration

The participants randomised to the AL group received Coartem Dispersible manufactured by Novartis Pharmaceutical [Batch: KU177; Manufacturing date: 02, 2020; Expiry date: 01, 2022], which was given as a co-formulated flavoured dispersible tablet of 20/120 mg. One tablet (20/120 mg) was given to participants weighing 5–14 kg, two tablets (40/240 mg) were given to those weighing 15–24 kg, and three tablets (60/360 mg) were given to participants weighing 25–35 kg [1]. This was administered at 0 h, 8 h, 24 h, 36 h, 48 h and 60 h. The 0 h, 24 h, and 48 h doses were administered by the caregivers in the comprehensive healthcare centre and were directly observed by the researchers or their trained assistants. The doses at 8 h, 36 h, and 60 h were given by caregivers at home. The caregivers of the participants were reminded to use the drug through a phone call at the time when the drug was due. The tablets were dispersed in water for participants who could not swallow them.

Participants in the DHAPQ group received P-Alaxin® manufactured by Bliss GVS Pharma Limited, [Batch: J1ALB003; Manufacturing date: 12, 2019; Expiry date: 11, 2021] given once daily, at the standard dose of 2.5 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg for dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine, respectively. Two formulations were used: 80 mg dihydroartemisinin + 640 mg piperaquine in 80 ml suspension and 40 mg dihydroartemisinin + 320 mg piperaquine tablet. Younger children who could not swallow tablets were given the suspension formulation at a dose of 2.4mls/kg per dose, while older ones who could swallow tablets were given the tablet formulation as follows: one tablet was given to participants weighing 11– ˂17 kg and two tablets were given to those weighing 17– ˂25 kg. All the doses of DHAPQ were administered by the primary caregivers in the comprehensive healthcare centre and were directly observed and supervised by the researcher or his two trained assistants.

To enhance the absorption of the antimalarial drugs, each participant in the AL and DHAPQ groups was given two sachets and one sachet of 14 g of Peak® powder milk (containing 26 g of milk fat), respectively. The caregivers were asked to dissolve the milk in water in a disposable plastic cup in the clinic and give it to the participants to drink after taking the drug. This was to be repeated for each dose of AL taken at home. All participants were monitored for half an hour after taking their doses in the comprehensive healthcare centre. Those who vomited at this time received another dose of the drug. If another vomiting occurred, the participant was withdrawn from the study and offered alternative treatment with a parenteral antimalarial. Participants were also withdrawn from the study if there was a need to use medications with antimalarial properties during the follow-up period.

High fever with a temperature greater than 38 °C was reduced by tepid sponging with lukewarm water. The caregivers were told to administer paracetamol syrup at 15 mg/kg body weight only if the fever did not come down with tepid sponging and exposure. They were informed not to administer paracetamol on the morning of follow-up. This was to have a fair idea of the fever clearance. Participants were also counselled to avoid using unprescribed medications, including herbal remedies.

Follow-up

Study treatment was provided for 3 days, starting on the day of randomisation (Day 0) and completed on Day 2. The participants were then followed up until day 42. Follow-up visits were scheduled on days 1, 2, 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42. The study physicians examined the participants during the visits. During the follow-up visits, primary caregivers were asked about adverse events that had occurred since the last visit. An adverse event was any sign or symptom that did not exist before the commencement of treatment but occurred during treatment or follow-up, or that was present at day 0 and became worse during treatment and follow-up, regardless of malaria parasite clearance [32]. Axillary temperature was measured, and a thick blood film specimen was taken to screen for the presence of malaria parasites and their density. Two drops of blood were spotted on the filter paper for parasite genotyping on each of the follow-up days and any time treatment failure was observed. Baseline haemoglobin concentration was checked only on day zero. The primary caregivers of participants who missed their follow-up appointment were called or visited at home that day. The participants who were treated with AL and later developed treatment failure were retreated with DHAPQ and vice versa.

Malaria parasite genotyping

At the end of the study, paired Day 0 and post-treatment dried blood spots on the filter were analysed for every patient with treatment failure to distinguish recrudescence from re-infection with different parasite strains in line with the WHO protocol [25, 33]. A genotype analysis was performed at the Molecular Biology Laboratory of the Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology (LAUTECH), Ogbomoso, South Western Nigeria, using a nested PCR technique to identify the different alleles of msp-1, msp-2, and Glurp genes of the parasite using allele-specific primers as described by Funwei et al. [34]. Based on the WHO 3/3 Match, P. falciparum recrudescence was said to occur if all or any one of the alleles in all three marker genes were shared between the paired enrolment and post-treatment samples [25, 35]. Reinfection with a new P. falciparum strain was when all or any one of the alleles for all three marker genes in the paired enrolment and post-treatment samples differed entirely. To avoid bias, all the dried blood samples collected for PCR genotyping were de-identified and assigned unique laboratory codes at OAUTHC before being transported to LAUTECH. The laboratory personnel at LAUTECH, performing the DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and gel electrophoresis, were completely unaware of the treatment outcome or microscopy results of the patients from whom the samples originated. The individuals responsible for reading and interpreting the PCR gel electrophoresis results were also blinded to the clinical outcomes and patient identifiers.

Study endpoints

The primary outcomes were malaria parasite clearance and adequate clinical and parasitological response on days 28 and 42 (ACPR28 and ACPR42). Malaria parasite clearance was assessed by day-3 parasite positivity, parasite clearance time, and fever clearance time. Parasite clearance time was the period between taking the first dose of an antimalarial medication and having the first two thick blood films in a row that are free of asexual P. falciparum parasites after inspecting 200 oil immersion fields [36, 37]. Fever clearance time is the duration from the first antimalarial dose till the temperature initially drops to 37.5 °C and remains below it for 24 h [22]. ACPR was defined as the absence of parasitaemia on day 28 (day 42) regardless of axillary temperature without initially having early treatment failure (ETF), late clinical failure (LCF), or late parasitological failure (LPF) [1, 25].

ETF was defined as the appearance of danger signs or severe malaria on days 1, 2, or 3 in the presence of parasitaemia, or parasitaemia on day 2 greater than day 0 count regardless of axillary temperature, or parasitaemia on day 3 with axillary temperature ≥ 37.5 °C, or parasitaemia on day 3 > 25% of day 0 count regardless of axillary temperature [1, 25]. LCF was defined as the appearance of danger signs or severe malaria and/or axillary temperature ≥ 37.5 °C, between days 4 and 28 (day 42) with parasitaemia without initially having ETF [1, 25]. LPF was said to have occurred if the axillary temperature is < 37.5 °C and there is parasitaemia on any day between days 7 and 28 (day 42) without initially having ETF or LCF [1, 25]. The secondary outcome was the tolerability of the two treatment regimens. The tolerability was assessed by the caregivers’ or participants’ reports of adverse events.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using the statistical product and service solutions (SPSS) software version 25 (SPSS, Chicago, Il, USA) and the specially designed WHO Excel spreadsheet [38]. The independent variables were the two treatment groups, while the dependent variables were malaria parasite density, PCR corrected and uncorrected adequate clinical and parasitological cure rate on days 28 and 42, parasite clearance time, fever clearance time, and adverse effects. The mean age, baseline temperature, and haemoglobin concentration of the participants that were continuous and normally distributed were compared by Independent Student’s T-tests. The baseline malaria parasite densities were not normally distributed and were reported in median (lower quartile–upper quartile) and compared by the Wilcoxon rank sum test. The chi-square test of independence was used to compare the proportion of categorical variables.

The analysis of therapeutic efficacy was done using both the intention-to-treat (ITT) and the per-protocol (PP) populations approach. All participants enrolled in the study were regarded as the ITT population. The PP population consisted of participants who finished the trial without going against the established protocol. The clinical outcomes of treatment of the two groups were compared using the chi-square test and the risk ratio with a 95% Confidence Interval. The cumulative survival was compared using Kaplan–Meier product-limit estimates of failure. The participants who were lost to follow-up were not included in the PCR-uncorrected per-protocol analysis. The last follow-up day was censored in their Kaplan–Meier analysis [39]. In the PCR-corrected per-protocol analysis, those who were lost to follow-up or had falciparum re-infection were excluded. The last follow-up day was censored in their Kaplan–Meier analysis. A p-value of < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

Between July 2020 and December 2020, 122 participants were enrolled and randomised into the two study groups: 61 participants in each of the treatment groups. Nine participants were lost to follow-up during the 42-day follow-up period, as seen in Fig. 1. Four participants in the AL treatment group were lost to follow-up (LFU) on Days 1, 7, 35, and 42, respectively. Five participants were lost to follow-up in the DHAPQ treatment group. Two of them on Day 1, the third on Day 14, the fourth on Day 35, and the fifth on Day 42. Thus, 57 (93.4%) of the 61 participants treated with AL completed the study, while 56 (91.8%) of the 61 participants treated with DHAPQ completed the study.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart describing the progress of patients through the study

Patients characteristics

Table 1 shows that the median (lower quartile-upper quartile) parasite density of the participants in the AL group was 3,600.0(2,420-5,399) parasite/µL, while that of the DHAPQ group was 3,440.0(2,640-5,597) parasite/µL (W = 3,667.0, p = 0.636). There were also no significant differences in the other baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the two treatment groups. Thus, the participants in both treatment arms were comparable in terms of their sociodemographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and treatment groups of the study participants

| Characteristics |

Artemether-lumefantrine (N=61) n(%) |

Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine phosphate (N=61) n(%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | ||||

| 6 -23 | 37(60.7) | 33(54.1) | ||

| 24 -41 | 16(26.2) | 13(21.3) | 0.263 | |

| 42 -59 | 8(13.1) | 15(24.6) | ||

| Mean ± SD (months) | 23.6 ± 13.0 (months) | 27.6 ± 16.6 (months) | 0.142^ | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 26(42.6) | 31(50.8) | ||

| Female | 35(57.4) | 30(49.2) | 0.368 | |

| Weight (kg) | ||||

| 5 – 10 | 25(41.0) | 24(39.3) | ||

| 11 – 16 | 34(55.7) | 32(52.5) | 0.505 | |

| >16 | 2(3.3) | 5(8.2) | ||

| Temperature (0C) | ||||

| 36.4 - 37.4 | 1(1.6) | 1(1.6) | ||

| 37.5 – 38.5 | 18(29.5) | 18(29.5) | ||

| 38.6 – 39.6 | 38(62.3) | 40(65.6) | 0.870 | |

| ≥ 39.7 | 4(6.6) | 2(3.3) | ||

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | ||||

| 7 – 9.9 | 14(23.0) | 16(26.2) | ||

| 10 -10.9 | 13(21.3) | 19(31.1) | 0.391 | |

| ≥ 11 | 34(55.7) | 26(42.6) | ||

| Parasite density(parasite/μL) | ||||

| Median (LQ-UQ) | 3,600.0 (2,420-5,399) | 3,440.0 (2,640-5,597) | 0.636§ | |

| Range | 2,010 - 8,820 | 2,010 – 9,640 | ||

^ Student T-test, § Wilcoxon rank sum test, LQ – lower quartile, UQ – upper quartile

Parasite clearance dynamics

Parasitaemia during follow-up

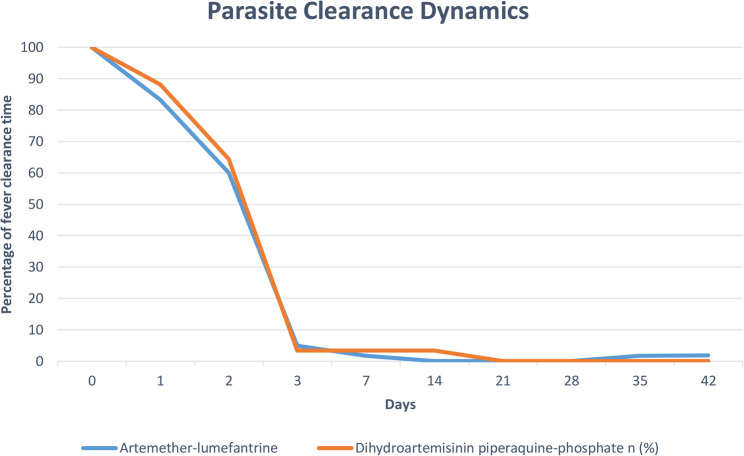

Malaria parasites were present in a substantial percentage of participants in both treatment arms on Day 1— 83.3% of those receiving AL treatment and 88.1% of those receiving DHAPQ treatment (Fig. 2). By Day 3, both groups’ parasite positivity had significantly decreased. 3.4% (95% CI 0.4–11.7) of participants in the DHAPQ group and 5.0% (95% CI 1.0–13.9) of participants in the AL group had parasitaemia. The parasite clearance rates at this early stage were comparable, as the difference in parasite positivity between the two groups on Day 3 was not statistically significant (p = 0.662).

Fig. 2.

Parasite clearance of artemether-lumefantrine and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine phosphate

The trend of parasite clearance continued, with only 1.7% of the AL group and 3.4% of the DHAPQ group remaining positive on Day 7. By Day 14, 3.4% of the DHAPQ group still had parasitaemia, whereas all participants in the AL group had completely eradicated their parasites (0.0%). By Day 21, all participants in both treatment arms had completely cleared their parasites, and this status persisted until Day 28. Malaria parasitaemia resurfaced in one participant each on Days 35 and 42 in the AL group.

Parasite and fever clearance time

Table 2 shows that the mean parasite clearance time among the participants in the AL group was slightly shorter than that in the DHAPQ group, but the difference was not statistically significant (61.30 ± 23.75 h vs. 63.97 ± 23.42 h; p = 0.541). The mean fever clearance time was significantly lower in the AL group compared to the DHAPQ group (46.16 ± 3.31 h vs. 48.83 ± 8.95 h; p = 0.032).

Table 2.

Mean parasite and fever clearance time of artemether-lumefantrine and dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine phosphate

| Artemether-lumefantrine | Dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine phosphate | T-test | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Parasite Clearance Time in Hours | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 61.30 ± 23.75 | 63.97 ± 23.42 | 0.614+ | 0.541 |

| Mean fever Clearance time in Hours | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 46.16 ± 3.31 | 48.83 ± 8.95 | 2.173+ | 0.032* |

+ Student T-test

Treatment outcomes

Polymerase chain reaction uncorrected efficacy

Table 3 showed the Day 28 intention-to-treat population analysis. During this period, two participants in the AL group and three in the DHAPQ group were lost to follow-up. Five participants also had treatment failure. This was distributed as one in the AL group (LCF at day 7) and four in the DHAPQ group (one LPF at day 14, and three LCFs-two at day 7 and one at day 14 respectively). Finally, 58 participants in the AL group and 54 in the DHAPQ group had adequate clinical and parasitological response. This gave a day 28 crude ITT cure rate of 95.1% for AL, which was higher than 88.5% for DHAPQ. The difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.190). In the per-protocol analysis (Table 4) of the 59 and 58 participants who were successfully followed up to day 28 in the AL and DHAPQ groups, respectively, the uncorrected ACPR cure rate was 98.3% for AL and 93.1% for the DHAPQ group. This difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.170).

Table 3.

The various clinical outcomes in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria with AL and DHAPQ (Day 28) (intention to treat population)

| PCR Uncorrected | AL (N=61) | DHAPQ (N=61) | Relative risk (AL vs DHAPQ) |

95% Confidence 0interval | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||||

| Late clinical failure | 1 | 1.6 | 3 | 4.9 | 3.000 | 0.32-28.05 | 0.335 | |

| Late parasitological failure | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.6 | 3.000 | 0.12-72.23 | 0.499 | |

| Adequate clinical and parasitological response (crude ITT cure rate) | 58 | 95.1 | 54 | 88.5 | 0.931 | 0.84-1.04 | 0.190 | |

LCF Late clinical failure, LPF Late parasitological failure, ACPR Adequate clinical and parasitological response

Table 4.

The various clinical outcomes in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria with AL and DHAPQ (Day 28) (per protocol population)

| PCR Uncorrected | AL (N=59) | DHAPQ (N=58) | Relative risk(AL vs DHAPQ) | 95% Confidence interval | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | n | % | ||||

| Late clinical failure | 1 | 1.7 | 3 | 5.1 | 3.052 | 0.33-28.50 | 0.328 |

| Late parasitological failure | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.7 | 3.051 | 0.13-73.40 | 0.492 |

| Adequate clinical and parasitological response | 58 | 98.3 | 54 | 93.1 | 0.947 | 0.88 -1.02 | 0.170 |

| PCR Corrected cure rate | AL (N=58) | DHAPQ (N=54) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||||

| 58 | 100 | 54 | 100 | - | - | -# | |

LCF Late clinical failure, LPF Late parasitological failure, ACPR Adequate clinical and parasitological response#: No p-value was computed because ACPR was constant in both treatment groups

At the end of day 42, seven participants had treatment failure. This was distributed as three in the AL group (LCF at day 7, 35, and 42) and four in the DHAPQ group (one LPF at day 14, and three LCFs-two at day 7 and one at day 14 respectively). Finally, 58 (95.1%) participants in the AL group and 54 (88.5%) in the DHAPQ group had adequate clinical and parasitological response. The PCR uncorrected ACPR on day 42 was 94.7% for the participants in the AL group and 92.9% for the DHAPQ group (Table 4). There was no statistical difference in the ACPR rate in the two treatment groups (p = 0.679).

Polymerase chain reaction corrected efficacy

The Polymerase chain reaction genotyping of the malaria parasite among the participants with treatment failures showed that all seven treatment failures were due to P. falciparum reinfection. Following PCR correction in which participants who were lost to follow-up and those who had P. falciparum re-infection were excluded, the cure rate was 100% for both AL and DHAPQ on both day 28 and day 42 (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 5.

The various clinical outcomes in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria with AL and DHAPQ (Day 42)

| PCR Unadjusted | AL (N=57) | DHAPQ (N=56) | Relative risk (DHAPQ vs. AL) | 95% Confidence interval | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||||

| Late clinical failure | 3 | 5.3 | 3 | 5.3 | 0.983 | 0.207-4.663 | 0.982 |

| Late parasitological failure | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.8 | 0.328 | 0.014-7.875 | 0.492 |

| Adequate clinical and parasitological response | 54 | 94.7 | 52 | 92.9 | 1.02 | 0.928-1.122 | 0.679 |

| PCR Adjusted | AL (N=54) | DHAPQ (N=52) | 95% Confidence interval | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||||

| 54 | 100 | 52 | 100 | - | - | --# | |

LCF Late clinical failur, LPF Late parasitological failure, ACPR Adequate clinical and parasitological response#: No p-value was computed because ACPR was constant in both treatment groups

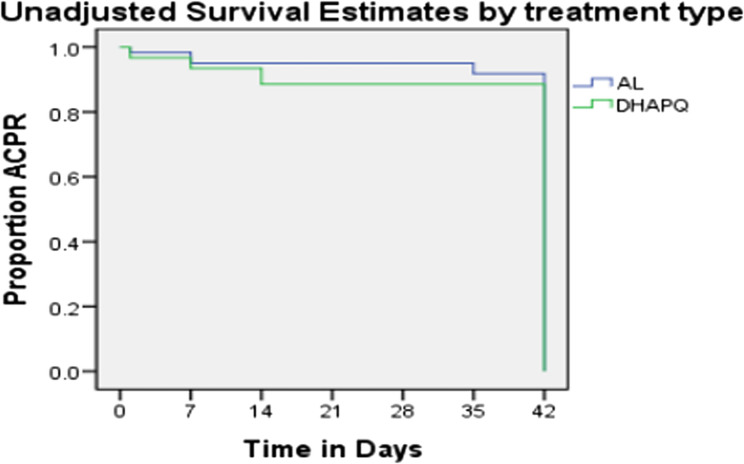

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis

As shown in Fig. 3, the cumulative incidence of success or cure on day 42 using the PCR-uncorrected Kaplan–Meier survival estimate was 94.7% (95% CI 85.4–98.9) in the AL group and 92.9% (95% CI 82.7–98.0) in the DHAPQ group. Although the percentage of participants with adequate clinical or parasitological response was higher among those in the AL than in DHAPQ, this was, however, not statistically significant. (Log-rank statistic = 0.386, p = 0.535).

Fig. 3.

Unadjusted survival estimates by treatment type

Tolerability

AL and DHAPQ were well tolerated with no serious adverse events observed (Table 6). None of the participants in the AL group recorded an adverse event. Five participants (8.9%) in the DHAPQ group reported mild adverse events, which were vomiting in 1(1.8%) participant, body itching in 3(5.4%) participants, and abdominal pain in 1(1.8%) participant. Although the relative risk (RR) of these adverse events in the DHAPQ group compared to the AL group seemed to be higher (RR for abdominal pain and vomiting = 3.053; RR for body itching and rashes = 7.123), none of the differences were statistically significant.

Table 6.

The various reported mild adverse events from Day 0 to Day 42 among participants treated with AL and DHAPQ

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.8 | 3.053 | 0.127-73.386 | 0.492 |

| Body itching and rashes | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 5.4 | 7.123 | 0.376-134.816 | 0.191 |

| Vomiting | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.8 | 3.053 | 0.127-73.386 | 0.492 |

Discussion

This study found that AL and DHAPQ were efficacious in the treatment of malaria in children with an ACPR cure rate that exceeds 90%. Reinfection, not recrudescence, was the cause of the seven treatment failures that the participants had. The drugs were tolerable with only 8.6% of the participants in the DHAPQ developing mild adverse events. The high therapeutic efficacies, safety and tolerability of the two drugs indicate that they both can continue to be used to treat uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Nigeria.

This clinical trial observed that the treatment failures were due to reinfection and not recrudescence. This may suggest that the suspected artemisinin resistance reported in Nigeria [11, 12] was due to reinfection by another strain of malaria parasite. The clinical and public health implications of the high re-infection rates found in this study suggest ongoing intense malaria transmission in this region despite control measures. Continued molecular surveillance of anti-malarial drug resistance is needed to monitor for emerging resistance and guide future treatment policies. There is hope that the adoption and deployment of malaria vaccines will lessen and eventually eradicate malaria infection and related morbidity and mortality. These findings underscore the need to educate and counsel caregivers on using malaria prevention strategies such as long-lasting insecticidal-treated nets and indoor residual spraying. This is in the spirit of using every consultation as an opportunity for health promotion and disease prevention.

The results of this study demonstrate the high efficacy of AL and DHAPQ in treating uncomplicated falciparum malaria, demonstrating their continuous relevance in the chemotherapeutic approach to malaria control. This will significantly lessen the burden of malaria when used with improved diagnosis and effective vector control. DHAPQ provides an alternative treatment option to artemether-lumefantrine and artesunate amodiaquine, which are the two recommended ACTs in the Nigerian National Malaria Control Programme [40]. This is not only because of its observed efficacy but also due to its simple single-daily dosing, supporting the call for its use as a first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria in Nigeria.

In this study, the Day-3 parasite positivity was 5% (95% CI of 1.0-13.9) in the AL group and 3.4% (95% CI of 0.4–11.7) in the DHAPQ treatment group. This high Day-3 parasite positivity may be due to the higher baseline parasite density observed among the participants. Parasite clearance is relatively slower in the face of a high parasite load [41]. Given that artemisinin resistance is defined as a delayed malaria parasite clearance of greater or equal 10% after a three-day treatment with an ACT [42], the fact that day-3 parasite positivity was present in 5% and 3.4% of participants in the AL and DHAPQ, respectively, ruled out the possibility of artemisinin resistance in the study area.

The high mean parasite clearance time of 61.30 ± 23.75 h and 63.97 ± 23.42 h among the participants in the AL and DHAPQ groups, respectively, may invariably be due to the higher initial parasite load. Similarly high mean parasite clearance times have been reported by other studies [26, 43, 44]. These studies were conducted during the rainy season when malaria transmission is higher. The mean fever clearance time was significantly lower in the AL group compared to the DHAPQ group (46.16 ± 3.31 h vs. 48.83 ± 8.95 h; p = 0.032). This was similar to what was obtained in a survey done in Senegal [45]. This value was, however, higher than those observed in other studies where antipyretics were used in the management of fever [43, 46]. The use of antipyretics can mask fever and give a lower fever clearance time. Only 5% of the participants in this study were given Paracetamol on the first day, while fever was reduced in others by tepid sponging with lukewarm water.

The high adequate clinical and parasitological response recorded for both ACTs in this study showed that they are still highly effective for the management of uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in under-five children. These findings are in tandem with those reported from other trials [26, 45, 47, 48]. Although the efficacy result from this index study was reassuring, the reports of lower therapeutic efficacies of both drugs in neighbouring Burkina Faso [10] and Mali [49] in 2021, call for continuous biennial monitoring of these ACTs as stipulated by the World Health Organisation [25]. Artemisinin resistance manifests clinically as ETF, while partner drug resistance manifests as LCF or LPF [50]. This means that the absence of ETF and the observation of LCF and LPF in this study denotes the resistance of the partner drug and not that of artemisinin.

Artemisinin and its derivatives have been considered safe and well-tolerated in patients of all age groups without causing any serious unexpected adverse events [51]. The findings from the comparative tolerability of AL and DHAPQ were not surprising. Both of them were well tolerated by the participants, with none of the participants in the artemether-lumefantrine group reporting any adverse event. DHAPQ was less well tolerated than AL, with five participants having mild adverse events in the form of vomiting, body itching, and abdominal pain. Though small, this favourable level of tolerability and no untoward severe adverse events concurs with reports from other previous studies [43, 52–54].

Limitations

A major limitation of this study is that the patients were not admitted, and the evening doses of AL were not directly observed. This may have led to missed unreported doses and an underestimation of the efficacy of AL. To mitigate against this risk, the caregivers were reminded daily to take their medications throughout the study duration. Admitting the study participants would also reduce the risk of reinfection. The use of 200 microscope fields as against 100 microscope fields as a cut-off for declaring a slide to be parasite-negative might have led to an overestimation of the antimalarial efficacy.

Another limitation of this study is the small sample size and its single-centre design, which may limit the representativeness of the findings to the wider population of under-five children with uncomplicated malaria in the region. Reinfection and recrudescence rates could vary in a larger and more diverse population sample. Although the study was conducted at a comprehensive healthcare facility in southwestern Nigeria, the findings may still be generalizable to other malaria-endemic areas in sub-Saharan Africa that share similar epidemiological characteristics, health system structures, and treatment protocols. Nevertheless, caution is warranted in extrapolating the results to settings with different parasite genetic profiles, transmission dynamics, levels of drug resistance, or patterns of healthcare access and adherence. Larger, multi-site studies are recommended to strengthen the evidence base and support broader policy applications regarding ACT efficacy, re-infection rates, and resistance surveillance in the region.

Conclusion

AL was found to have a good parasite clearance based on the World Health Organisation recommendation that the cure rate of artemisinin-based combination therapy should be at least 90% for it to be considered effective and relevant for use. Similarly, DHAPQ was also found to have good parasite clearance. However, no significant statistical difference was observed between their efficacy. It recommended health education of caregivers of under-five children on malaria prevention and continuous efficacy monitoring of the drugs.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the effort of the microscopists led by Mrs E.E. Olowoyo of the Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, OAUTHC, Ile-Ife, who worked extremely inconvenient hours to ensure high-quality microscopy. We are also grateful to Mr M.A. Adedeji and Mrs Z.K Ahmed, who were the research assistants.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Artemisinin-based Combination Therapy

- ACPR

Adequate Clinical and Parasitological Response

- AL

Artemether–Lumefantrine

- DHAPQ

Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine phosphate

- ETF

Early Treatment Failure

- glurp

Glutamate-rich protein

- iRBCs

Infected red blood cells

- ITT

Intention-to-treat

- RBC

Red Blood Cell

- LCF

Late Clinical Failure

- LFU

Lost to follow-up

- LPF

Late Parasitological Failure

- msp1

Merozoites surface protein 1

- msp2

Merozoites surface protein 2

- MUAC

Mid-upper arm circumference

- OAUTHC

Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex

- PBS

Peripheral blood smears

- PCR

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- Pfcrt

Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter

- PfK13

P. falciparum K13 propeller gene

- Pfmdr-1

P. falciparum multidrug resistance protein 1

- PP

Per Protocol

- SPSS

Statistical Product for Service Solution

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

AAA, ISB, TOA conceived and designed the study. AAA, SAO, OOO, AOO, TOO, and OOA supervised patient enrollment, clinical follow-up, and data collection. RIF, OO, and AAA conducted laboratory analyses. DAA, AAA, ABB performed the data analysis and interpretation. AAA, AOA, MKO, ATS, KMA, AOF, and EOA drafted the manuscript. All authors agreed to be responsible for every part of the work, approved the final version, and critically reviewed the manuscript for significant intellectual content.

Funding

The study was funded by the researchers.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval for the conduct of the study was obtained from the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex, Ile-Ife Ethical Review Committee (ERC/2019/10/06) (S1 File). The study was registered on 10/07/2020 with the Pan African Clinical Trials Registry, Cochrane South Africa (PACTR202007553348930) (S2 File). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of eligible participants before their recruitment into the study. For the parents or guardians who could not read, the Subject Information Sheet was read and explained to them, and they thumb-printed their consent afterwards. Data were collected anonymously. All the caregiver-child pairs received a token of $1.5 to cover the costs of transportation and a light snack for each appointment at the comprehensive health centre. There were no changes to the pre-specified primary or secondary trial outcomes, nor were there any substantial amendments to the study protocol after the trial’s initiation.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of the children.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation. WHO guidelines for malaria. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Das S, Kar A, Manna S, Mandal S, Mandal S, Das S, et al. Artemisinin combination therapy fails even in the absence of plasmodium falciparum kelch13 gene polymorphism in central India. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phuc BQ, Rasmussen C, Duong TT, Loi MA, Ménard D, Tarning J, et al. Treatment failure of dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine for plasmodium falciparum malaria, Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(4):715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, Sreng S, Mao S, Sopha C, et al. Dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine resistance in plasmodium falciparum malaria in cambodia: a multisite prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(3):357–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uwimana A, Penkunas MJ, Nisingizwe MP, Warsame M, Umulisa N, Uyizeye D, et al. Efficacy of Artemether–Lumefantrine versus Dihydroartemisinin–Piperaquine for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria among children in rwanda: an Open-Label, randomised controlled trial. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2019;113(6):312–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Straimer J, Gandhi P, Renner KC, Schmitt EK. High prevalence of plasmodium falciparum K13 mutations in Rwanda is associated with slow parasite clearance after treatment with Artemether-Lumefantrine. J Infect Dis. 2022;225(8):1411–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikeda M, Kaneko M, Tachibana S-I, Balikagala B, Sakurai-Yatsushiro M, Yatsushiro S, et al. Artemisinin-resistant plasmodium falciparum with high survival rates, Uganda, 2014–2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(4):718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borrmann S, Sasi P, Mwai L, Bashraheil M, Abdallah A, Muriithi S, et al. Declining responsiveness of plasmodium falciparum infections to artemisinin-based combination treatments on the Kenyan Coast. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11):e26005. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukhongo HN, Kinyua JKe, Weldemichael YG, Kasili RW. Screening for antifolate and Artemisinin resistance in plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates from three hospitals of Eritrea. F1000 research. 2023;10:628. 10.12688/f1000research.54195.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Gansané A, Moriarty LF, Ménard D, Yerbanga I, Ouedraogo E, Sondo P, et al. Anti-Malarial efficacy and resistance monitoring of Artemether-Lumefantrine and Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine shows inadequate efficacy in children in Burkina Faso, 2017–2018. Malar J. 2021;20(1):48–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wundermann GS, Osiki AA. Currently observed trend in the resistance of malaria to Artemisinin-Based combination therapy in Nigeria – A report of 5 cases. Infect Drug Resist. 2017;21(2):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ajayi NA, Ukwaja KN. Possible Artemisinin-Based combination Therapy-Resistant malaria in nigeria: A report of three cases. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2013;46(4):525–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noreen N, Ullah A, Salman SM, Mabkhot Y, Alsayari A, Badshah SL. New insights into the spread of resistance to Artemisinin and its analogues. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2021;27(3):142–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uwimana A, Legrand E, Stokes BH, Ndikumana JL, Warsame M, Umulisa N, et al. Emergence and clonal expansion of in vitro artemisinin-resistant plasmodium falciparum kelch13 R561H mutant parasites in Rwanda. Nat Med. 2020;26(10):1602–8. doi.org/10.038/s41591-020-1005-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwuafor AA, Ogban GI, Elem DE, Emanghe UE, Owai PA, Erengwa PC, et al. Plasmodium falciparum Kelch 13-propeller gene mutation update in Nigeria – a systematic review. Nigerian Health J. 2023;23(2):587–96. 10.60787/tnhj.v23i2.670. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ndong Ngomo JM, Mawili-Mboumba DP, Mouity TN, Leonetti A, Mabika DM, Mihindou JC. Clonal Transmission of Emerging Novel Plasmodium falciparum Kelch13 Mutations and Increasing Complexity of Infection in Libreville, Gabon, 2021–2023. medRxiv. 2025;8(7):25333205. 10.1101/2025.08.07. medRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blasco B, Leroy D, Fidock DA. Antimalarial drug resistance: linking plasmodium falciparum parasite biology to the clinic. Nat Med. 2017;23(8):917–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Izevbekhai O, Adeagbo B, Olagunju A, Bolaji O. Quality of artemisinin-based antimalarial drugs marketed in Nigeria. Trans R Soc Trop. 2017;111(2):90–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Malaria Elimination Programme (NMEP) NPCN. National bureau of statistics (NBS), and ICF International. Nigeria malaria indicator survey 2021 final Report. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville. Maryland, USA: NMEP, NPopC, and ICF International; 2022. pp. 1–190. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Federal Ministry of Health NMCP, Abuja, Nigeria. Nigeria Strategic Plan 2009–2013. 2009.https://extranet.who.int/countryplanningcycles/sites/default/files/planning_cycle_repository/nigeria/nigeria_draft_malaria_strategic_plan_2009-13.pdf

- 21.Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria. National guideline for diagnosis and treatment of malaria. 4th ed. Abuja, Nigeria: National Malaria Elimination Programme; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toure OA, Landry TNG, Assi SB, Kone AA, Gbessi EA, Ako BA, et al. Malaria parasite clearance from patients following Artemisinin-Based combination therapy in Côte d’ivoire. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11(1):2031–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organisation. Artemisinin resistance and Artemisinin-Based combination therapy efficacy. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2018. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO. | Responding to antimalarial drug resistance. WHO. 2018.

- 25.World Health Organisation. Methods for Surveillance of Antimalarial Drug Efficacy. Geneva: World Health Organisation. 2009. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/publications/gmp/methods-for-surveillance-of-antimalarial-drug-efficacy.pdf?sfvrsn=29076702_2

- 26.Ebenebe JC, Ntadom G, Ambe J, Wammanda R, Jiya N, Finomo F, et al. Efficacy of Artemisinin-Based combination treatments of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Under-Five-Year-Old Nigerian children ten years following adoption as First-Line antimalarials. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;99(3):649–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ezenduka CC, Ogbonna BO, Ekwunife OI, Okonta MJ, Esimone CO. Drugs use pattern for uncomplicated malaria in medicine retail outlets in Enugu Urban, Southeast nigeria: implications for malaria treatment policy. Malar J. 2014;13(1):243–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agarwal A, McMorrow M, Onyango P, Otieno K, Odero C, Williamson J, et al. A randomised trial of Artemether-Lumefantrine and Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria among children in Western Kenya. Malar J. 2013;12(1):254–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organisation. World malaria report 2024: addressing inequity in the global malaria response. Geneva: World Health Organisation. 2024. p. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 30.Noordzij M, Tripepi G, Dekker FW, Zoccali C, Tanck MW, Jager KJ. Sample size calculations: basic principles and common pitfalls. Nephrol Dialysis Transpl. 2010;25(5):1388–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nji AM, Ali IM, Moyeh MN, Ngongang EO, Ekollo AM, Chedjou JP, et al. Randomised Non-inferiority and safety trial of Dihydroartemisin-Piperaquine and Artesunate-Amodiaquine versus Artemether-Lumefantrine in the treatment of uncomplicated plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cameroonian children. Malar J. 2015;14(1):27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gold MS, Balakrishnan MR, Amarasinghe A, MacDonald NE. An approach to death as an adverse event following immunisation. Vaccine. 2016;34(2):212–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zani B, Gathu M, Donegan S, Olliaro PL, Sinclair D. Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine for treating uncomplicated plasmodium falciparum malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;14(1):34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Funwei RI, Thomas BN, Falade CO, Ojurongbe O. Extensive diversity in the allelic frequency of plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface proteins and Glutamate-Rich protein in rural and urban settings of Southwestern Nigeria. Malar J. 2018;17(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organisation. Informal consultation on methodology to distinguish reinfection from recrudescence in high malaria transmission areas: report of a virtual meeting, 17–18 May 2021. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khoury DS, Zaloumis SG, Grigg MJ, Haque A, Davenport MP. Malaria parasite clearance: what are we really measuring? Trends Parasitol. 2020;36(5):413–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thriemer K, Hong NV, Rosanas-Urgell A, Phuc BQ, Ha DM, Pockele E, et al. Delayed parasite clearance after treatment with Dihydroartemisinin-Piperaquine in plasmodium falciparum malaria patients in central Vietnam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(12):7049–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organisation. Tools for Monitoring Antimalarial Drug Efficacy: WHO Data Entry and Analysis Tool 2017. Geneva: World Health Organisation. 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/case-management/drug-efficacy-and-resistance/tools-for-monitoring-antimalarial-drug-efficacy

- 39.Ranganathan P, Pramesh C, Aggarwal R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Intention-to-Treat versus Per-Protocol analysis. Perspect Clin Res. 2016;7(3):144–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Federal Ministry of Health. National guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of malaria. 3rd ed. Abuja: National Malaria Elimination Programme; 2015. pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ouji M, Augereau JM, Paloque L, Benoit-Vical F. Plasmodium falciparum resistance to Artemisinin-Based combination therapies: A sword of Damocles in the path toward malaria Elimination. Parasite. Parasite. 2018;25(24):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Health Organisation. Q & A on Artemisinin Resistance. Geneva: World Health Organisation. 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/malaria/mpac-documentation/mpac-april2018-q-a-artemisinin-resistance-session2.pdf?sfvrsn=ed1d4c78_2

- 43.Ojurongbe O, Lawal OA, Abiodun OO, Okeniyi JA, Oyeniyi AJ, Oyelami OA. Efficacy of Artemisinin combination therapy for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Nigerian children. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2013;7(12):975–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taïsso MH, Souleymane IM, Alio HM, Diar MSI, Sougoudi DA, Mbanga D, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of the ASAQ versus AL association in children 6–59 months for the treatment of uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in Massakory (Chad). Am J Biomed Life Sci. 2021;9(5):259–66. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sylla K, Abiola A, Tine RCK, Faye B, Sow D, Ndiaye JL, et al. Monitoring the efficacy and safety of three Artemisinin-Based combination therapies in senegal: results from two years of surveillance. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oguche S, Okafor HU, Watila I, Meremikwu M, Agomo P, Ogala W, et al. Efficacy of Artemisinin-Based combination treatments of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Under-Five-Year-Old Nigerian children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2014;91(5):925–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akano K, Ntadom G, Agomo C, Happi CT, Folarin OA, Gbotosho GO, et al. Parasite reduction ratio one day after initiation of Artemisinin-Based combination therapies and its relationship with parasite clearance time in acutely malarious children. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7(1):122–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shibeshi W, Alemkere G, Mulu A, Engidawork E. Efficacy and safety of Artemisinin-Based combination therapies for the treatment of uncomplicated malaria in paediatrics. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diarra Y, Kone O, Sangaré L, Doumbia L, Haidara DB, Diallo M, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of Artemether–Lumefantrine and Artesunate–Amodiaquine for the treatment of uncomplicated plasmodium falciparum malaria in Mali, 2015–2016. Malar J. 2021;20(1):235–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Slater HC, Griffin JT, Ghani AC, Okell LC. Assessing the potential impact of Artemisinin and partner drug resistance in sub-Saharan Africa. Malar J. 2016;15(1):10–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schramm B, Valeh P, Baudin E, Mazinda CS, Smith R, Pinoges L, et al. Tolerability and safety of Artesunate-Amodiaquine and Artemether-Lumefantrine fixed dose combinations for the treatment of uncomplicated plasmodium falciparum malaria: two Open-Label, randomised trials in Nimba County, Liberia. Malar J. 2013;12(1):250–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Q, Zhang Z, Yu W, Lu C, Li G, Pan Z, et al. Surveillance of the efficacy of Artemisinin–Piperaquine in the treatment of uncomplicated plasmodium falciparum malaria among children under 5 years of age in Est-Mono District, Togo, in 2017. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11(784):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Warsame M, Hassan AM, Hassan AH, Jibril AM, Khim N, Arale AM, et al. High therapeutic efficacy of Artemether–Lumefantrine and Dihydroartemisinin–Piperaquine for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Somalia. Malar J. 2019;18(1):231–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adjei A, Narh-Bana S, Amu A, Kukula V, Owusu-Agyei S, Oduro A, et al. Outcomes in a safety observational study of Dihydroartemisinin/Piperaquine (Eurartesim®) in the treatment of uncomplicated malaria at public health facilities in four African countries. Malar J. 2016;15(1):43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.