Abstract

Pyrazole-fused quinoxalines provide an attractive structural motif for medicinal chemistry and have inspired the development of novel synthetic methods. This work details a concise methodology for the synthesis of a new class of pyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-4-ones, where the incorporation of a sulfonyl fluoride enables sulfur(IV) fluoride exchange (SuFEx) chemistry. This synthetic approach opens the door for the rapid diversification of these fused heterocycles, providing a powerful strategy for the expansion of chemical space and the development of novel bioactive compounds.

Keywords: Click chemistry, Fused-ring systems, Heterocycles, Pyrazole, SuFEx reaction

1. Introduction

Nitrogenous heterocycles enable essential life processes, including storing and transmitting the genetic code, regulating neurochemistry, and enabling redox reactions crucial in cellular metabolism, among others. Their ubiquity in pharmaceuticals,[1] agrochemicals,[2] fluorophores,[3–7] and other useful molecules stems from the structural and functional diversity imparted by various natural and synthetic nitrogen-containing scaffolds.[8–10]

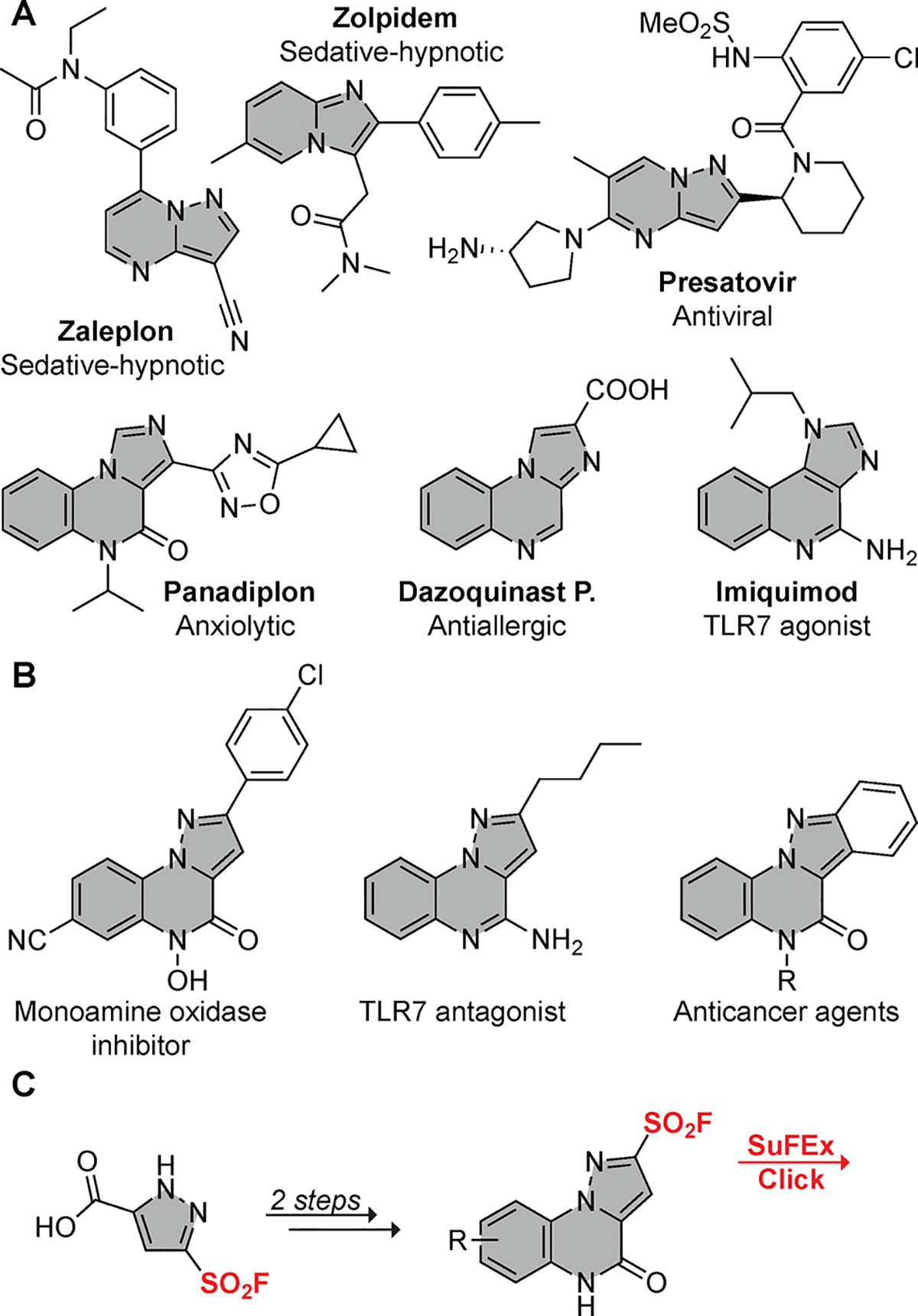

Notably, fused N-heterocycles engage with biological targets and serve as the core structural element of commercial pharmaceuticals including Imiquimod,[11] Zaleplon,[12] Dazoquinast P.,[13] Zolpidem,[14] and Presatovir[15] (Figure 1A). Fusion of a pyrazole with quinoxaline and quinazoline rings presents a promising scaffold displaying diverse biological activities, including as monoamine oxidase inhibitors,[16] TLR7 antagonists,[11] topoisomerase inhibitors,[17] thrombin inhibitors,[18] and anticancer agents[19] as illustrated in Figure 1B. These examples prove the versatility of the pyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline scaffold with broad applicability in medicinal chemistry.[17,20] As such, substantial effort has been directed toward devising innovative and efficient synthetic strategies for accessing functionalized pyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline derivatives.[21]

Figure 1.

(A) Commercially available drugs with fused heterocycle motifs in their molecular structures. (B) Examples of compounds featuring pyrazole-quinoxaline motifs studied for their biological significance. (C) Strategy for the synthesis of fused pyrazole-quinoxaline derivatives and subsequent sulfur–fluoride exchange (SuFEx) click reactions reported within.

Herein, we disclose a novel approach to rapidly access pyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-4-ones bearing a sulfonyl fluoride (Figure 1C). We harnessed previously disclosed Ullman-type N-arylations employed to cyclize similar substrates[18,19] to generate clickable pyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-4-ones—the sulfonyl fluoride enables efficient, selective, and modular functionalization via Sulfur–Fluoride Exchange (SuFEx) click chemistry.[22] SuFEx reactions proceed under mild conditions and enable the addition of a wide range of nucleophilic groups, expanding the chemical diversity of accessible compounds.[23] This approach opens new avenues for the rapid syntheses of an important class of fused heterocycles.

2. Results and Discussion

En route to SuFEx-able pyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline derivatives, we first synthesized 3-(fluorosulfonyl)-1H-pyrazole-5-carboxylic acid 3. We utilized our previously reported 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition strategy of 1-bromoethene-1-sulfonyl fluoride (Br-ESF) 2 with a diazoacetate[24] employing tert-butyl diazoacetate 1 to enable efficient ester hydrolysis. The desired 3-(fluorosulfonyl)-1H-pyrazole-5-carboxylic acid 3 was obtained in 71% yield over two steps with the sulfonyl fluoride remaining intact (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 3-(fluorosulfonyl)-1H-pyrazole-5-carboxylic acid 3 via catalyst-free diazo–Br-ESF 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition and selective ester hydrolysis.

We next functionalized the carboxylic acid via acyl substitution with 2-iodoaniline. Our initial attempts focused on the reaction of 3 with 2-iodoaniline using well-established carbodiimide reagents for amide coupling. We obtained the 5-((2-iodophenyl)carbamoyl)-1H-pyrazole-3-sulfonyl fluoride 4a in poor to fair yields with N,N’-diisopropylcarbodiimide (DIC), N,N’-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopripyl)carbodiimide (EDC, with either N,N’-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) or 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP, Table S1). The addition of 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) in the reaction of 3 with EDC and DIPEA provided 4a with an isolated yield of 56% after 16 h (Scheme 2). Similarly, uronium and phosphonium reagents HBTU and PyBOP gave yields between 53% and 43%, respectively.

Scheme 2.

Optimized conditions for the acyl substitution reactions of o-iodoaniline with 3-(fluorosulfonyl)-1H-5-carboxylic acid 3.

Acyl substitution was also achieved through the reaction of the acyl chloride 3-Cl with 2-iodoaniline, which was obtained by refluxing 3 in excess thionyl chloride (Scheme 2). The room temperature reaction of 3-Cl in pyridine with catalytic DMAP resulted in an improved isolated yield of 62% over two steps. Overall, 4a was obtained in fair but useful yields via the reaction of 3 and 2-iodoaniline promoted by either EDC, DIPEA, and HOBt (56%) or through the acyl chloride 3-Cl (62%), providing access to a diverse set of SuFExable amide derivatives.

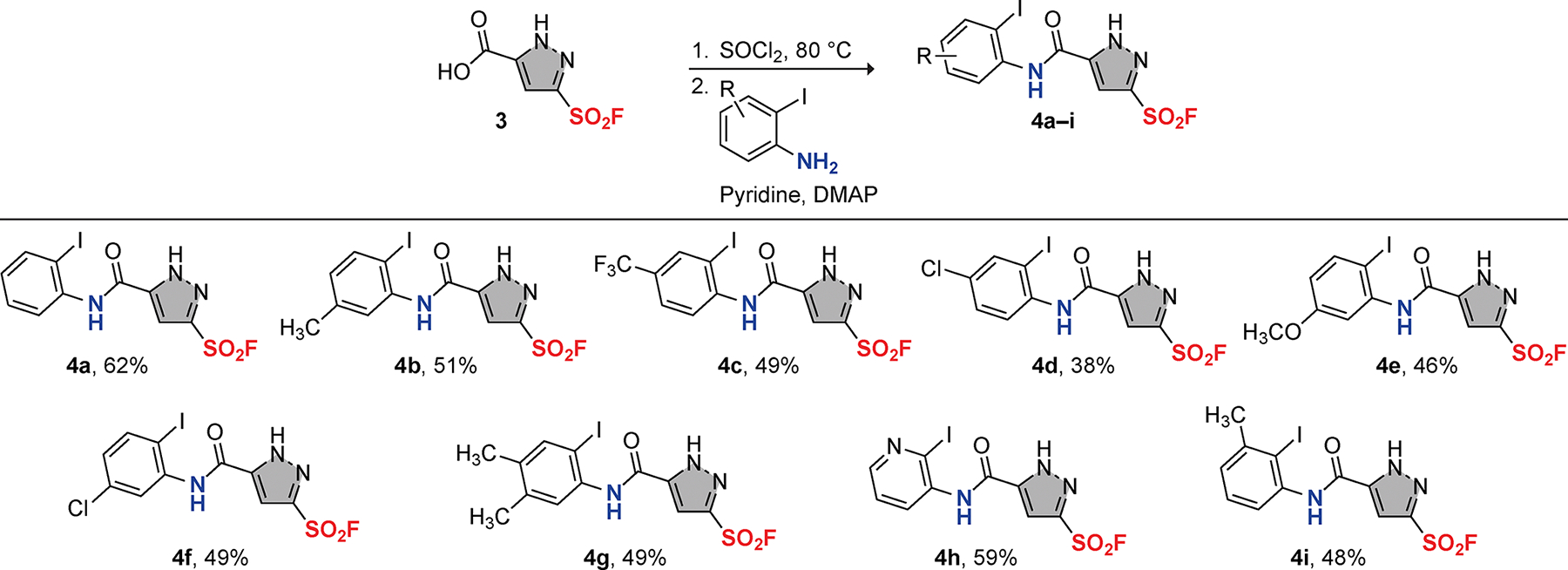

Utilizing the optimal reaction conditions (via the acyl chloride 3-Cl), we synthesized 5-carbamoyl-1H-pyrazole-3-sulfonyl fluorides 4a–i from the pyrazolyl carboxylic acid 3 and a series of ortho-iodoarylamines. The resulting compounds were obtained in moderate yields and exhibit a variety of substitution patterns, including both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups (Figure 2).[25] Notably, the reaction of 2-iodopyridin-3-amine with 3 afforded 4 h in a 59% yield, which is comparable to that of 4a.

Figure 2.

Acyl substitution of pyrazolyl carboxylic acid 3 with o-iodoarylamines to generate 5-carbamoyl-1H-pyrazole-3-sulfonyl fluorides 4.

With 5-carbamoyl-1H-pyrazole-3-sulfonyl fluorides 4a–i in hand, our focus shifted to intramolecular cyclization via C–N coupling of the pyrazole ring with the aryl iodide to afford the corresponding 4-oxo-4,5-dihydropyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-2-sulfonyl fluorides 5a–i. We investigated Buchwald–Hartwig and Ullmann-type cross-coupling reactions using various combinations of catalysts, ligands, and bases, employing 5-((2-iodophenyl)carbamoyl)-1H-pyrazole-3-sulfonyl fluoride 4a as a model substrate (Table 1).[18,19,26,27]

Table 1.

Optimization of Reaction Conditions for the Synthesis of Fused 4-oxo-4,5-dihydropyrazolo[1,5-a]-quinoxaline-2-sulfonyl fluorides.

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Entry | Catalyst | Mol % | Ligand | Mol % | Base | Equiv. | Solvent | T, °C | t, h | Yield, %a) |

|

| ||||||||||

| 1 | Pd(dba)2 | 10 | X-Phos | 20 | t-BuOK | 2.0 | DMF | 100 | 12 | — |

| 2 | CuI | 30 | TMEDA | 50 | t-BuOK | 2.0 | DMF | 100 | 12 | — |

| 3 | Cu(acac)2 | 30 | TMEDA | 100 | t-BuOK | 2.0 | Dioxane | 120 | 12 | — |

| 4 | CuI | 15 | 1,10-Phenanthrolineb) | 25 | K2CO3 | 2.3 | Dioxane | 150 | 12 | — |

| 5 | CuI | 15 | 1,10-Phenanthrolineb) | 20 | K2CO3 | 2.3 | Toluene | 150 | 4 | 20 |

| 6 | CuI | 20 | 1,10-Phenanthrolineb) | 50 | K3PO4 | 2.1 | Toluene | 150 | 12 | Traced) |

| 7 | Cu2O | 25 | 1,10-Phenanthrolineb) | 60 | K2CO3 | 3.0 | Toluene | 150 | 17 | 91 |

| 8 | Cu2O | 25 | 1,10-Phenanthrolinec) | 60 | K2CO3 | 3.0 | Toluene | 150 | 17 | 83 |

| 9 | Cu2O | 50 | 1,10-Phenanthrolineb) | 60 | K2CO3 | 3.0 | Toluene | 150 | 17 | 77 |

| 10 | Cu2O | 50 | 1,10-Phenanthrolineb) | 60 | Cs2CO3 | 3.0 | Toluene | 150 | 24 | Traced) |

| 11 | Cu2O | 50 | 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-Phenanthroline | 60 | K2CO3 | 3.0 | Toluene | 150 | 24 | 49 |

Isolated yield, unless otherwise stated.

1,10-Phenanthroline monohydrate.

Anhydrous 1,10-Phenanthroline.

Determined by LC-MS.

Initial screenings with Pd(dba)2 and X-Phos (Entry 1) did not yield the desired product 5a. Similar results were observed when employing copper(I) iodide and copper(II) acetylacetonate with TMEDA as a ligand (Entries 2 and 3). Changing the ligand to 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate, the solvent to dioxane, and the base to potassium carbonate was ineffective (Entry 4); however, the desired product was obtained in 20% yield upon treatment with copper(I) iodide (15 mol%), 1,10-phenanthroline (20 mol%), and potassium carbonate (2.3 equiv.) in toluene at 150 °C (Entry 5). Analogous conditions with potassium phosphate as the base produced the desired product in only trace amounts, as determined by LC-MS (Entry 6). The optimal conditions were achieved by employing copper(I) oxide (25 mol%) with 1,10-phenanthroline (60 mol%) and potassium carbonate (3.0 equiv.) in toluene at 150 °C for 17 h, where 5a was obtained in an excellent yield of 91% (Entry 7). Using anhydrous 1,10-phenanthroline under the optimal conditions slightly lowered the yield to 83% (Entry 8). Increasing the catalyst loading to 50 mol% had a negative effect on the reaction (Entry 9), as did the use of 2,9-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline (Entry 11). Meanwhile, cesium carbonate was found to be ineffective as the base (Entry 10).

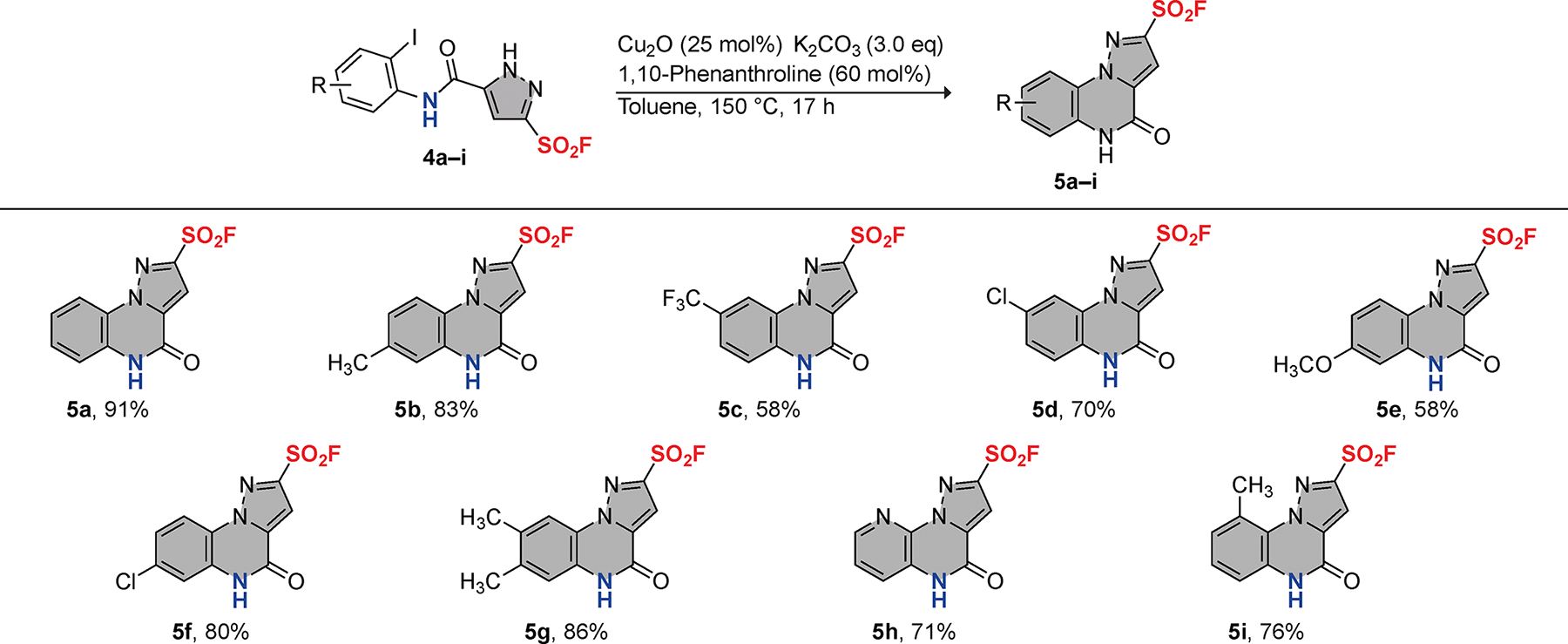

With the optimal N-arylation conditions established, we performed intramolecular C—N coupling with the set of 5-carbamoyl-1H-pyrazole-3-sulfonyl fluorides 4a–i (Figure 3). The 4-oxo-4,5-dihydropyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-2-sulfonyl fluorides 5a–i were obtained in good to excellent yields, demonstrating the scope of the reaction. We also sought to determine the ability of aryl bromides to undergo C—N coupling. We synthesized 5-((2-bromophenyl)carbamoyl)-1H-pyrazole-3-sulfonyl fluoride 4a’ and subjected it to the optimal conditions, which afforded compound 5a, albeit in significantly reduced yield (32%; Scheme S1). Additionally, multiple side products were observed by thin layer chromatography in the reaction of the bromo-derivative (4a’) that were not detected in the reaction of the parent (4a).

Figure 3.

Synthesis of 4-oxo-4,5-dihydropyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-2-sulfonyl fluorides via intramolecular N-arylation.

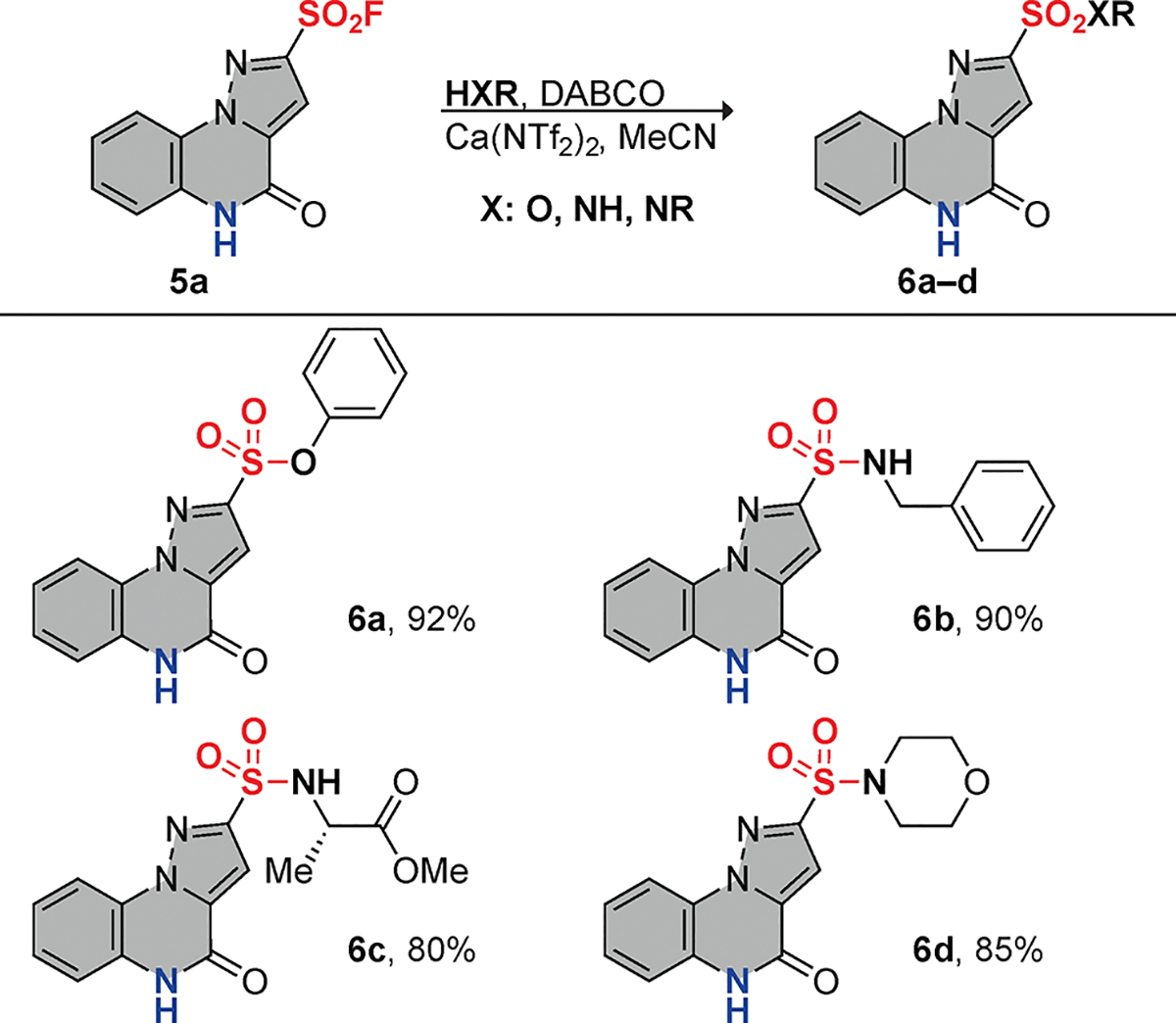

We next determined the ability of the pyrazolo-sulfonyl fluorides to undergo SuFEx click reactions (Figure 4). 4-oxo-4,5-dihydropyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-2-sulfonyl fluoride 5a was reacted with phenol to give the corresponding sulfonate 6a in 92% yield. Primary and secondary amines gave the respective sulfonamides 6b and 6d in 90% and 85% yield, respectively. Additionally, 5a was reacted with an amino acid derivative—the methyl ester of L-alanine—resulting in an 80% yield of 6c. These results demonstrate that SuFExable pyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline derivatives efficiently react with a variety of nucleophiles, providing a versatile platform for further functionalization.

Figure 4.

SuFEx reactions of 4-oxo-4,5-dihydropyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-2-sulfonyl fluoride.

Spectroscopic studies of 4-oxo-4,5-dihydropyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-2-sulfonyl fluorides 5a–i were performed, as pyrazole derivatives often display attractive properties for various applications (Table 2 and Figure 5).[3–7] Each compound displayed two absorption peaks centered at 259–264 nm (λabs(1)) and 320–334 nm (λabs(2)). Interestingly, the λmax corresponds to the λabs(1) peak (at ~260 nm) for all compounds except 5h, while the intensities of the two peaks are nearly equal for compounds 5b, 5e, and 5g. Distinct shoulders at ~15 nm longer wavelength than the low-energy peaks are apparent in all cases and pronounced in spectra obtained for compounds 5c–h.

Table 2.

Photophysical data of 5a–i (100 μM, DMSO, and λex: 260 nm).

| λabs(1), nma) | λabs(2), nma) | Relative Intensityb) | λem, nm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 5a | 260 | 324 | 1.4 | 387 |

| 5b | 260 | 327 | 1.1 | 392 |

| 5c | 259 | 320 | 1.5 | 384.5 |

| 5d | 263 | 332 | 1.5 | 405.5 |

| 5e | 261 | 332 | 1.0 | 394 |

| 5f | 261 | 326 | 1.2 | 390 |

| 5g | 266 | 334 | 1.1 | 394.5 |

| 5h | 259 | 327 | 0.6 | 385 |

| 5i | 264 | 320 | 2.0 | 384.5 |

Absorption λmax indicated by bold type-face.

λabs(1): λabs(2).

Figure 5.

(A) Absorption spectra of compounds 5a–i (100 μM, DMSO). (B) Emission spectra of compounds 5a–i (100 μM, DMSO, and λex: 260 nm).

In the emission spectra, Stokes shifts of 60–70 nm were observed relative to the λabs(2) peak with maximum emission (λem) observed at wavelengths ranging from 385–406 nm for 5a–i. Additionally, red-shifted emission peaks were observed at ~700–800 nm; however, their intensity was found to be significantly lower than the fluorescence peaks. Compound 5h was found to display the highest emission intensity for both peaks, suggesting the nitrogen of the pyridine ring may facilitate intersystem crossing and phosphorescence.

The effect of the pyridine N on the photophysical properties was investigated using a combined experimental and computational approach, with 5a and 5h as model compounds. Initial experiments in DMSO revealed two absorption maxima for both compounds. The longer wavelength bands (λabs(2)) were observed at 324 nm for 5a and 327 nm for 5h. Fluorescence emissions were detected at 387 nm for 5a and 385 nm for 5h. From these values, the experimental Stokes shifts were determined to be 63 nm for 5a and 58 nm for 5h (Table 3).

Table 3.

Experimental and predicted photophysical data between 5a and 5h. All wavelengths in nm.

| Experimental Data | CAM-B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) | ωB97XD/def2-SVP | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λabs(2) | λem(1)a) | Stokes Shift | λabs(2) | λem(1)a) | Stokes Shift | λem(2)a) | λabs(2) | λem(1)a) | Stokes Shift | λem(2) a) | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 5a | 324 | 387 | 63 | 283 | 356 | 73 | 490 | 275 | 342 | 66 | 463 | |

| 5h | 327 | 385 | 58 | 285 | 357 | 71 | 495 | 278 | 343 | 65 | 466 | |

λem(1) and λem(2) indicate fluorescence and phosphorescence wavelengths, respectively.

To rationalize the observed photophysical properties, we performed TD-DFT calculations using both CAM-B3LYP[28] and ωB97XD[29] levels of theory, with solvent effects modeled via the SMD continuum for DMSO. The computed vertical excitation energies closely reproduced experimental trends (Table 3). At the CAM-B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p) level, emission maxima were predicted at 356 nm for 5a and 357 nm for 5h, corresponding to theoretical Stokes shifts of 73 and 71 nm, respectively. With ωB97XD/def2-SVP, the emission wavelengths were slightly shorter: 342 nm (5a) and 343 nm (5h), giving Stokes shifts between 66 and 65 nm. These theoretical shifts differ from experimental ones by only 5–10 nm, indicating good semi-quantitative agreement. Both experimental and theoretical results consistently show that 5h has a slightly smaller Stokes shift than 5a, validating the reliability of the computational approach in capturing the relative photophysical behavior.

Although experimental excitation wavelengths (e.g., 260 nm) align with higher-lying singlet excited states (S7–S8) with significant oscillator strengths, the predicted emission from these states (λem ≈ 311–322 nm) poorly matches the experimental fluorescence maxima (~385–387 nm). Emission from S1 → S0 transition, however, shows better agreement in both wavelength (342–357 nm) and Stokes shift, indicating rapid internal conversion to S1 prior to fluorescence. This behavior aligns with Kasha’s rule, which states that fluorescence typically originates from the lowest excited singlet state regardless of excitation wavelength.[30] Thus, both compounds exhibit Kasha-like photo physics with emission primarily from S1.

We then compared the vertical excitation energies of the low-lying singlet and triplet states to evaluate the potential for intersystem crossing (ISC) and phosphorescence (Table S3). At both levels of theory, 5a and 5h have nearly identical S1 energies as well as their respective T1 energies, indicating that they possess similar fundamental emission characteristics. However, significant differences emerged in the alignment of their triplet states. The T3 state in 5h lies only ~0.05 eV below S1, forming a small energy gap that promotes efficient ISC via vibronic coupling and enhanced spin–orbit-mediated state mixing.[31] Conversely, the T3 state in 5a lies slightly above S1 (ΔS1–T1 = 0.03 eV), producing an energetically less favorable ISC pathway. This energetic proximity in 5 h supports a mechanistic basis for enhanced ISC and, consequently, potential phosphorescence.

To further support this hypothesis, we calculated the phosphorescence emission wavelengths as vertical T1 → S0 transitions. Using CAM-B3LYP/6–31 + G(d,p), phosphorescence was predicted at 490 nm for 5a and 495 nm for 5h; with ωB97XD/def2-SVP, the values were 463 nm (5a) and 466 nm (5h). These results place the phosphorescence in the visible region and show a modest red-shift for 5h compared to 5a. Coupled with the favorable S1–T3 gap, these findings offer strong computational evidence for its enhanced ISC potential and observable phosphorescence of 5h under appropriate experimental conditions.[32]

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, we have developed a concise synthetic route to SuFExable pyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-4-ones. A 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of Br-ESF with tert-butyl diazoacetate followed by ester hydrolysis provides the sulfonyl fluoride-containing pyrazolyl carboxylic acid. Acyl substitution with various ortho-iodoaryl amines provides a set of 5-carbamoyl-1H-pyrazole-3-sulfonyl fluorides that efficiently undergo intramolecular C—N coupling to form the desired 4-oxo-4,5-dihydropyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-2-sulfonyl fluorides. Sulfur(VI) fluoride exchange (SuFEx) reactions of both nitrogen and oxygen-based nucleophiles demonstrate the utility of this robust strategy for the diversification of these fused heterocycles. Overall, this method enables the rapid generation of a wide array of structurally distinct molecules with potential applications in medicinal chemistry and materials science.

4. Experimental Section

1-bromoethene-1-sulfonyl fluoride (Br-ESF) (2) was prepared according to previously reported procedures.[33–36]

3-(fluorosulfonyl)-1H-pyrazole-5-carboxylic acid (3). 1-bromoethene-1-sulfonyl fluoride 2 (150 mg, 794 μmol, 1.0 eq) was dissolved in 8 mL acetonitrile in a 25 mL round bottom flask. To the solution, tert-butyl 2-diazoacetate 1 (147 mg, 1.03 mmol, 1.3 eq) was added. The resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1h. The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure when the reaction was complete (controlled by HPLC). The crude residue was dissolved in a mixture of TFA and DCM (1:3 v/v) and was stirred for 12 h. The solvent was evaporated, and the dry residue was fractioned on silica gel, eluting with a mixture of Hexane/EtOAc 1:1 (Rf = 0.15) to afford compound 3 (155 mg, 71%) as a white powder (mp 101–102 °C). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3CN) δ 12.87 (br, 1H), 7.48 (s, 1H). 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CD3CN) δ 158.60, 145.16, 144.89, 137.64, 112.36. 19F NMR (471 MHz, CD3CN) δ 63.7 (s). HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M – H]− Calcd for C4H3FN2O4S 192.9724; Found 192.9725.

4.1. General Procedure for Acyl Substitution

Thionyl chloride (1.0 mL) was added to 3-(fluorosulfonyl)-1H-pyrazole-5-carboxylic acid 3 (1.0 eq) and the mixture was stirred at reflux for 1 h. The solution was cooled to room temperature and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in pyridine (5.0 mL) and the desired aryl amine (1.05–1.1 equiv.) and a catalytic amount of DMAP were added at 0 °C. The resulting mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for 12 h. The resulting mixture was poured into a 1 M HCl solution at 0 °C and then extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic layer was dried over MgSO4, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the dry residue was purified using flash chromatography.

4.2. General Procedure for N-Arylation

The product obtained from the General Procedure for Acyl Substitution (1.0 equiv.) was dissolved in 1.0–2.0 mL of dry toluene in a sealed tube fitted with a rubber septum. The reaction vessel was evacuated under vacuum and backfilled with argon 2–3 times. Cu2O (0.20–0.35 equiv.), 1,10-phenanthroline monohydrate (0.60 equiv.), and K2CO3 (3.0 equiv.) were added under an inert atmosphere and the vessel was sealed. The resulting mixture was heated at 150 °C until completion. The reaction mixture was then quenched with a saturated aqueous solution of NH4Cl and extracted with EtOAc. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure and purified using flash chromatography.

4.3. General Procedure for SuFEx

4-oxo-4,5-dihydropyrazolo[1,5-a]quinoxaline-2-sulfonyl fluoride 5a (1.0 equiv.), a nucleophile (1.0–1.1 equiv.; see Figure 4), calcium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)amide (1.4 equiv.), DABCO (2.1–3.0 equiv.), and acetonitrile (1.0 mL) were combined in a vial. The reaction was stirred at room temperature until the starting material was fully consumed as confirmed by TLC. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the resulting residue was purified by flash chromatography.

Supplementary Material

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under https://doi.org/10.1002/ajoc.202500474

Supporting Information

Experimental procedures, 1H and 13C NMR spectra (PDF), along with computational methods and data, Cartesian coordinates of optimized structures.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by start-up funds from NMSU and by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20GM103451.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

References

- [1].Heravi MM, Zadsirjan V, RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 44247–44311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ndikuryayo F, Gong X-Y, Yang W-C, Agric J. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 17762–17770. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Willy B, Müller TJJ, Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2082–2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Benson N, Suleiman O, Odoh SO, Woydziak ZR, Pyrazole I, J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 11856–11862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tigreros A, Portilla J, RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 19693–19712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Reddy DS, Novitskiy IM, Beloglazkina AA, Kutateladze AG, Org. Lett. 2024, 26, 2558–2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Melo-Hernández S, Ríos M-C, Portilla J, RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 39230–39241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Katritzky AR, Advances in Heterocyclic Chemistry, Academic Press, Cambridge, MA, 1963–2016. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fuse S, Morita T, Johmoto K, Uekusa H, Tanaka H, Chem. -Eur. J. 2015, 21, 14370–14375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ciupa A, RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 10565–10572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bou Karroum N, Moarbess G, Guichou J-F, Bonnet P-A, Patinote C, Bouharoun-Tayoun H, Chamat S, Cuq P, Diab-Assaf M, Kassab I, Deleuze-Masquefa C, J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 7015–7031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Cherukupalli S, Karpoormath R, Chandrasekaran B, Hampannavar GA, Thapliyal N, Palakollu VN, Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 126, 298–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yadav A, Yadav A, Tripathi S, Dewaker V, Kant R, Yadav PN, Srivastava AK, J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 7350–7364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Langtry HD, Benfield P, Zolpidem, Drugs 1990, 40, 291–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mackman RL, Sangi M, Sperandio D, Parrish JP, Eisenberg E, Perron M, Hui H, Zhang L, Siegel D, Yang H, Saunders O, Boojamra C, Lee G, Samuel D, Babaoglu K, Carey A, Gilbert BE, Piedra PA, Strickley R, Iwata Q, Hayes J, Stray K, Kinkade A, Theodore D, Jordan R, Desai M, Cihlar T, J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 1630–1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Panova VA, Filimonov SI, Chirkova ZV, Kabanova MV, Shetnev AA, Korsakov MK, Petzer A, Petzer JP, Suponitsky KY, Bioorg. Chem. 2021, 108, 104563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Garg M, Chauhan M, Singh PK, Alex JM, Kumar R, Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 444–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dunker C, Imberg L, Siutkina AI, Erbacher C, Daniliuc CG, Karst U, Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Li Y, He L, Qin H, Liu Y, Yang B, Xu Z, Yang D, Molecules 2024, 29, 464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Waseem AM, Elmagzoub RM, Abdelgadir MMM, Bahir AA, El-Gawaad NSA, Abdel-Samea AS, Rao DP, Kossenas K, Bräse S, Hashem H, Results Chem. 2025, 13, 101989. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wiethan C, Franceschini SZ, Bonacorso HG, Stradiotto M, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 8721–8727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dong J, Krasnova L, Finn MG, Sharpless KB, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 9430–9448. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Homer JA, Xu L, Kayambu N, Zheng Q, Choi EJ, Kim BM, Sharpless KB, Zuilhof H, Dong J, Moses JE, Sulfur Fluoride Exchange. Nat. Rev. Methods Primer 2023, 3, 58. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yamanushkin P, Kaya K, Feliciano MAM, Gold B, J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 3868–3873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kozlowski MC, Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 7247–7249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Klapars A, Huang X, Buchwald SL, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 7421–7428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yang Q, Zhao Y, Ma D, Org. Process Res. Dev. 2022, 26, 1690–1750. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yanai T, Tew DP, Handy NC, Chem. Phys. Lett. 2004, 393, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chai J-D, Head-Gordon M, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kasha M, Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1950, 9, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Marian CM, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2021, 72, 617–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Penfold TJ, Gindensperger E, Daniel C, Marian CM, Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 6975–7025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Thomas J, Fokin VV, Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 3749–3752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Smedley CJ, Giel M-C, Molino A, Barrow AS, Wilson DJD, Moses JE, Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 6020–6023. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Leng J, Qin H-L, Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 4477–4480. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Eremin DB, Fokin VV, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 18374–18379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.