Abstract

Background

People with disabilities face profound health disparities and systemic barriers to healthcare access, especially in low- and middle-income countries. These barriers range from inaccessible infrastructure and communication formats to negative attitudes and limited training among healthcare workers. This paper focuses on the co-design of the Disability Awareness Toolkit (DAT), a practical, contextually grounded toolkit to promote inclusion and accessibility in health and post-GBV clinical services in South Africa.

Method

The development of the DAT followed the co-design framework established by Birds et al., structured around two design cycles. The first cycle focused on creating the Disability Awareness Checklist (DAC) and its accompanying automated reporting system. The second cycle involved the development of the DAC’s implementation support tools, including an intervention menu and a training component. Each cycle incorporated (a) pre-design activities such as literature and document reviews and key interest holder mappings, (b) co-design activities such as workshops with a diverse group of interest holders—including persons with disabilities—alongside DAC facilitator training, and pilot testing in healthcare settings, and (c) post-design adaptation. Feedback was collected using accessible, structured formats to ensure clarity and inclusivity. Any conflicting feedback was resolved through follow-up discussions and consensus-building, reinforcing the participatory and inclusive nature of the process.

Results

The iterative co-design process was informed by the lived experiences of healthcare users and providers, revealing the importance of local relevance, flexibility, and power-sensitive collaboration. The final DAT consists of a comprehensive toolkit: the DAC with 53 core elements, automated reporting tools, a practical intervention menu tailored to local contexts, and an integrated training approach. The consultative process led to formally adopting appreciative inquiry as a key facilitation technique, helping participants better identify actionable, locally feasible solutions. The combination of the tool design and appreciative inquiry showed promise to create awareness and initiate change.

Conclusion

The DAT’s evolution highlights the power of co-design in addressing healthcare inequalities. It demonstrates how inclusive, locally grounded, and flexible design processes can produce meaningful quality assurance tools that reflect the diverse realities of service users and providers in unequal contexts.

Keywords: Primary health, Accessibility, Inclusion, Disability, Audit, South Africa

Background

People with disabilities face significant health disparities characterised by both increased health risks and barriers to healthcare [1–5]. On the one hand, the scarce evidence available reveals that adults with disabilities are at increased risk of many health conditions, including HIV, COVID-19, cancer and diabetes [4, 6]. Similarly, global evidence shows that children with disabilities are more likely to be malnourished and die in childhood, have respiratory infections, fever and diarrhoea [4]. Women and girls with disabilities are also at increased risk of gender-based violence (GBV) and have lower coverage of modern contraceptives than women without disabilities [4, 6, 7]. In fact, they are twice as likely to be exposed to HIV and GBV than their peers without disabilities in Sub-Saharan Africa, where both HIV and GBV are endemic [4, 6, 8, 9].

On the other hand, the majority of people with disabilities live in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) where they experience policy-related, physical, financial, structural, communication and attitudinal barriers to healthcare [3–5, 10]. Research has shown that women with disabilities experience particular barriers when accessing sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) services, including post-GBV, pregnancy prevention and HIV services [11–14]. Several studies have described the inaccessibility of facilities, communication, and negative attitudes of healthcare workers as key barriers [4, 10, 15]. Further work also revealed that healthcare workers experienced challenges when working with people with disabilities, in particular through a lack of resources and training opportunities that enable them to work with people with disabilities, emotional difficulties when working with this population and excessive workloads that leave limited time to attend to patients [16].

As a result, people with disabilities in LMIC face a 2- to 3-fold higher mortality rate than those without disabilities, primarily due to barriers to healthcare, lower health awareness, and reduced autonomy [1, 17, 18]. These challenges also contribute to lower rates of preventive screenings, immunisations, and treatments [3, 4, 19]. To uphold their right to health on an equal basis, it is essential to eliminate barriers to healthcare. A crucial step in this process is the development of disability-inclusive and accessible primary health care (PHC), including post-GBV clinical services, where people with disabilities are expected, accepted and connected [1, 19].

It is well understood that ‘disability-inclusive and accessible’ PHC services must fulfil accessibility requirements by aligning with the principles of ‘universal design’ and ‘reasonable accommodation’ [20]. This includes barrier-free physical infrastructure such as ramps, non-slip floors, wide corridors, colour contrasts, assistive devices, and diverse, user-friendly communication formats, including simple language, text-to-voice and visuals [21–23]. When universal design falls short, services must provide ‘reasonable accommodation’, including diverse communication techniques such as sign language, augmented communication, Braille and personalised assistance [20, 21, 23]. Beyond accessibility, inclusion requires that healthcare services be person-centred, acceptable to, and able to cater to the needs of people with disabilities. It also entails that healthcare workers are competent and equipped to identify, support, and connect people with disabilities to essential services, including rehabilitation (e.g. physiotherapy or speech therapy), disability (e.g. assistive devices) and social services (e.g. grants and assistants) [1, 4, 21]. This also requires a commitment to support individuals with disability throughout their entire care pathway journey [1, 5, 10, 21]. However, research from LMIC highlights significant gaps. PHC services in these settings lack many basic accessibility features [5, 24, 25]. Barriers to inclusion are related to a lack of consideration of the needs and voices of people with disabilities. Healthcare workers may have low confidence, lack disability training, and sometimes have negative attitudes towards people with disabilities [5, 26]. Resource constraints and weak care pathway linkages further hinder efforts to identify, refer, and follow up with individuals. These limit the provision of essential services and undermine efforts to monitor and evaluate service coverage for this population [4, 5, 10, 21, 22, 26].

In their systematic review on health equity and people with disabilities, Grèaux et al. emphasise that “profound systemic changes and action-oriented strategies are warranted to promote health equity for persons with disabilities” (page 1) [5]. Similarly, Mactaggart et al. highlight the need for more robust evidence and data “on the accessibility of primary health facilities to identify practical and cost-effective solutions to the common barriers of people with disabilities” (page 7) [5, 21]. They emphasise that facility and service assessments are a critical first step, as they expose gaps to address. Their research reveals that while disability accessibility audits are commonly conducted for buildings, transportation, and websites, they are rarely applied to healthcare services and remain largely unexamined. A global search for suitable disability audit or assessment tools for LMIC identified only six potential tools [21]. Among these, the South African Disability Awareness Checklist (DAC), and focus of this paper, stood out as the most promising for adaptation and testing due to its “relative brevity compared to other tools and background as a disability sensitisation and action tool” (page 2) [21]. According to the review, crucial to its selection was its co-design process, which involved consultation with interest holders and ensured alignment with international frameworks [21]. Our paper will engage with how our team undertook this process.

Co-designing healthcare tools promotes person-centred care by engaging service users, providers, policymakers, and other interest holders throughout the process [27]. In the context of disability research, it also aligns with the disability sector’s motto, “Nothing about us without us” [28]. A core principle of co-design is the active involvement and contributions of diverse interest holders in the design, implementation, and evaluation of service delivery or innovations [27, 29]. The co-design process requires careful management of power dynamics, including addressing rigid hierarchical structures, creating opportunities for input, considering sociocultural beliefs and practices, navigating political interference, and adapting working methods to ensure inclusivity [29]. However, there is a paucity of literature on co-design processes in health research, particularly within the context of disability and healthcare in LMIC [29].

This paper will outline the co-design process for the Disability Awareness Toolkit (DAT), which includes a straightforward disability facility assessment tool, the Disability Awareness Checklist (DAC), along with its online data management tool, intervention menu and training approach [30, 31]. This paper will reflect on our processes, features and adaptations in designing this toolkit and how it initiates disability inclusion and accessibility in health and post-GBV clinical services in an LMIC. We will also reflect on how we worked with a diverse set of interest holders, including people with disabilities, in the co-design process, and adaptations made due to the intensive consultation process. The combined process is presented here by a group of authors, including researchers, service delivery and civil society representatives. Half of the authors are also people with lived experience of disability, giving the paper a unique perspective of people with disabilities as tool developers and academic writers.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the South African Medical Research Council (EC028-6/2021) and the Department of Health. All participants were provided with informed consent, and participation was voluntary.

Methods

Design phases

The Disability Awareness Toolkit (DAT) was developed based on research on gender, disability, HIV, and GBV in Sub-Saharan Africa [11, 26, 32, 33]. Early studies highlighted the increased vulnerability of people with disabilities to HIV and GBV and the need for inclusive healthcare services [11, 15, 32, 34–42]. Based on these studies, a training program on disability, HIV, and GBV was piloted in 2014 in South Africa by some of the authors, including a disability checklist as a training tool capturing accessibility and inclusion aspirations laid out in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) [26]. Participants assessed their PHC facilities using this checklist and identified actionable improvements, fostering agency and practical solutions suitable for their resource-limited settings [34, 43]. Further, applications in South Africa and Botswana showed that the training together with the checklist led to improvements in service accessibility and staff attitudes [26]. This discovery led to further development and testing of the checklist in a quality assurance project focusing on post-GBV clinical services in South Africa (2021–2024).

The further development followed a design process that aligns with Bird et al.‘s cyclical process and design phases of pre-design, co-design, and post-design (Fig. 1) [27]. Two design cycles were completed, one developing and testing the Disability Awareness Checklist (DAC) as part of a Quality Assurance tool for post-GBV and public healthcare clinical services and one developing and testing the Disability Awareness Toolkit (DAT), including the DAC and its intervention menu in primary healthcare (PHC) clinics in South Africa (Table 1) [44, 45].

Fig. 1.

DAC design steps for each cycle

Table 1.

Project process phases and steps aligned with bird’s co-design framework

| Co-design phases | Design steps | Cycle 1 (DAC design) | Cycle 2 (DAC menu design) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-design | Step 1: Contextual Inquiry |

Conducting literature and tool review, adaptation of draft DAC version 1 and integration into GBV QA tool, Building a collaborative team |

Dissemination, informational interviews and discussions with researchers and implementers on needed improvements for the DAC and its proposed intervention menu and training |

| Step 2: Preparation & Training |

Selecting consultation experts and facilitators for stakeholder engagement Preparing of consultation materials |

Selecting consultation experts and facilitators, DAC online training development Drafting of DAC intervention menu |

|

| Co-design | Step 3: Framing the Issue | Conducting expert consultation to review QA tool, including draft DAC version - identifying what must change | Conducting expert consultations and workshops, and informational consultations to improve DAC and its draft intervention menu |

| Step 4: Generative Design |

Adapting QA tool including DAC version 1 (content and RedCap data entry interface), Selecting of facilitators (QA process with experienced researchers) |

Developing DAC version 2, a facilitator guide and finalising DAC intervention menu, Selecting facilitators (QA process with inexperienced young people with and without disabilities) |

|

| Step 5: Sharing Ideas and piloting |

Preparing fieldwork processes Conducting DAC assessment and appreciative inquiry in pilot post-GBV and PHC clinics. |

Preparing fieldwork processes Conducting DAC assessment and appreciative inquiry in pilot PHC clinics |

|

| Post-design | Step 6: Data Analysis |

Organising and analysing data Experimenting with narrative reports and solution-finding |

Organising and analysing data Professionalising narrative reports and solution-finding |

| Step 7: Requirements and Translations |

Further adapting the DAC Identifying needed actions to improve the process (e.g. DAC menu, training) |

Further adapting the DAC menu Identifying needed actions to improve the process (e.g. disability and GBV training, M&E, DAC menu) |

During the pre-design phase, the team reviewed literature and potential tools, gathered feedback from conference presentations and meetings, adapted the previous checklist, and identified interest holders and facilitators for the co-design process [44]. The team also reflected on their own positionality and relative power and discussed potential power dynamics amongst interest holders and how to facilitate inclusive consultations, allowing both written and verbal/signed feedback. Accessibility needs were prioritised through accommodations such as Braille, audio formats, sign language, breaks, and language adaptations.

This phase also included the selection of appropriate facilitators for fieldwork testing, which included, in cycle one, the lead researchers (some of them with disabilities) and junior staff. In cycle two, the team selected young people with disabilities as DAC facilitators. They were trained to work collaboratively and appreciatively with the facility staff, the DAC and its intervention menu [44, 46].

During the co-design phase, the team conducted expert consultation workshops and prepared the fieldwork. Cycle one consultations developed and adapted the DAC, and cycle two developed the DAC intervention menu (links to solutions) [44]. This process also included discussions with local interest holders, particularly the local District AIDS Councils and civil society, to gain support and advice for the project undertakings (methods, sampling, process) [47]. In cycle two this also included sharing the DAC and a draft intervention menu with the broader disability sector community through the South African Disability Alliance and a two-day intensive workshop with disability and health sector representatives refining the DAC and its draft intervention menu [48]. After each round of consultations, the team field-tested the DAC assessment in pilot healthcare facilities. In cycle two, the team also tested the DAC intervention menu [44, 45].

In the post-design phase, the team analysed and synthesised the data collected with the DAC in each cycle, including data from the intervention menu. The team experimented with different facility reporting formats for the DAC assessment and selected solutions, which led to automated RedCap and detailed narrative reports for each facility. Team consultations revealed the need for further adaptations to ensure the DAC language was clear and straightforward. Cycle one also revealed the need to enhance the appreciative inquiry process during the result discussions in facilities by developing the DAC intervention menu that lays out feasible solutions. Cycle two consultations led to identifying and developing healthcare worker training which was required.

Co-design approach

Experts and fieldwork healthcare facilities were identified for consultation in collaboration with key interest holders (e.g., the Department of Health, District Aids Council, disability sector and development partners). The team applied two sampling techniques for the formal expert consultations and DAT pilot testing fieldwork. In cycle one, the team utilised a maximum variation sampling approach to ensure that experts from diverse backgrounds would provide feedback on the development of the DAC and its integration into a more extensive GBV-QA process tool. This sample included different vulnerable subgroups (people with disabilities are part of all key populations), the Department of Health (DOH), the government, and development partners (Table 2). In cycle two, the team applied purposeful sampling. It included experts from the disability sector, including academics, activists, DOH leadership, and development partners. It was necessary to consult with interest holders who could inform the DAC intervention menu. People with disabilities were part of both cycles as team members and experts.

Table 2.

Stakeholder sampling consultative workshops – number of participants

| Expert consultations | Cycle 1 (DAC design) | Cycle 2 (DAC menu design) |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | ||

| Co-researcher consultations (researchers in the same researcher organisation that were not part of the team) | 5 | 0 |

| GBV response sector, including SA academics, NGO/CBO, National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) and DOH representatives, and service providers | 9 | 0 |

| LGBTQI + sector, including activists, academics, NGO/CBO representatives, and DOH service providers | 11 | 0 |

| Sex worker sector, including SA activists, academics, NGO/CBO representatives, and DOH service providers | 12 | 0 |

| Disability sector, including SA activists, academics, NGO/CBO representatives, and PHC service providers for disability and rehabilitation services | 6 | 17 |

| Department of Health leadership | 5 | 5 |

| The project team | ||

| The team at the research organisation | 3 | 5 |

| Department of Health representatives | 1 | 1 |

| Disability sector lead representative | 1 | 1 |

| Development partners representatives | 3 | 1 |

During the consultations, the team shared the draft versions of the tool (including a readable version for screen reader JAWS). We provided the opportunity to give individual written and/or verbal feedback in online group consultations. For this purpose, the team provided guiding questions, prompting comments and a feedback form. The guiding questions prompted interest holders’ perception of the DAC regarding its standards/elements and verification criteria, its suitability to assess inclusion and accessibility, the importance of standards/elements, and where and how the tool could be used. The feedback form captured data on the specific elements of the tool, the discussion points or comments on this element and recommendations to improve the element. It also provided space to suggest additional elements, changes in approach, and suggestions for applying the tool. Online expert consultations and meetings were in English, recorded, captured in meeting notes, and synthesised in meeting reports. Where needed, sign language was available. A consolidated report was developed for each cycle of consultations. The team discussed conflicting feedback, and further consensus discussions were facilitated where needed.

Field-testing

The final draft of the tool was tested in PHC and post-GBV public clinical services. During the field testing, the team applied a purposeful sampling technique, focusing on healthcare facilities that provide post-GBV clinical services in cycle one and PHC clinics in cycle two (Table 3). These facilities were selected in consultation with interest holders and the Department of Health to maximise the diversity of the collected data without interfering with patient care. The project was implemented in three districts chosen in collaboration with the DOH and development partners. Cycle one included the Ekurhuleni and uMgungundlovu districts with 14 facilities, and cycle two included the eThekwini district with 10 facilities.

Table 3.

Sampling of healthcare facilities for field-testing – number of facilities

| Type of health facility | Cycle 1 (DAC design) | Cycle 2 (DAC menu design) |

|---|---|---|

| Post-GBV Clinical Service Thuthuzela centres | 5 | 0 |

| Crisis Centres | 5 | 0 |

| Primary Health Care Clinics | 2 | 8 |

| Primary Health Care Mobile Clinics | 2 | 0 |

| Primary Health Care Community Health Centres | 0 | 2 |

During the field testing, the team used the respective DAC version and a RedCap electronic data entry version (12.5.2 and 13.10.1) in both cycles. In cycle two, the intervention menu was added. The team administered the two-stage process of the DAC in each health facility, with stage one assessing the facility based on all DAC elements and stage two applying appreciative inquiry techniques to work collaboratively towards finding feasible solutions for the facility. Appreciative Inquiry (AI) is a collaborative process focusing on positive change management rather than problem-solving [49]. In line with AI, the team first defined a collective goal with facility staff (improve disability inclusion) and then followed the first two stages of AI - discover & dream, and thereafter discussed the last two stages of AI - design & destiny/delivery [49, 50]. During DAC visits, facilitators worked with participants to set collective goals for increasing disability inclusion and accessibility. Discussions focused on identifying possible changes (discovery), starting with each participant’s personal agency, followed by envisioning and planning these changes (dream and design). In cycle two, a DAC intervention menu supported this process, helping facility staff identify feasible solutions and plan for implementation. Facilitators recorded discussions and solutions, and after each district field test, the team reviewed necessary adaptations.

Facility feedback

Data from the DAC assessment and solutions identified during the appreciative inquiry were entered into RedCap, generating automated reports with visual spider diagrams and synthesis tables for each DAC sub-domain. The team shared these reports on the same day in a joint meeting where the results were discussed and solutions to address gaps brainstormed. In cycle two, each facility received a comprehensive narrative report detailing the findings and proposed solutions for change.

The field testing data were analysed separately for each facility and collectively across all facilities, using descriptive statistics for assessment data and guided content analysis for qualitative data from the comment section. The results were synthesised into two fieldwork reports, further discussed in key stakeholder meetings and conference presentations and used to inform the development of healthcare worker training [45, 48, 51].

Results

The process of co-design led to several adaptations, transforming the original disability checklist first into the DAC and thereafter developing the DAT, including the DAC and its intervention menu and training. The original checklist included four domains with 31 elements: universal design (7 elements), reasonable accommodation (10 elements), capacity building (8 elements), and linkages to care and support (6 elements). The answer option for each element included a simple binary format Yes/No with the option to choose ‘Not sure’ when applicable. It also had an additional field to identify “things that I can change/influence”. This provided the baseline for the first co-design cycle of expert consultations and development of the DAC version one (47 elements). The second co-design cycle led to further development and adaptations into the DAT, including the DAC version two (53 elements), its intervention menu, and training tools.

Process of co-design and field-testing

In the first cycle of the co-design process, the team assessed six disability audit tools, including the original disability checklist. Most tools focused on physical accessibility and communication, but the disability checklist stood out for addressing staff training and care pathway linkages. It was the only action-oriented tool suitable for resource-poor settings. Other tools provided valuable insights on international standards, which informed the adaptation of the checklist into draft DAC version one.

Using a draft version of the DAC, the team conducted six expert consultations and two district fieldwork meetings. They also presented at several District AIDS Council meetings, discussing the DAC as part of a broader QA tool for post-GBV services. While expert consultations focused on content, the fieldwork and district meetings were key to securing project buy-in and stakeholder permissions. As the quote below illustrates, feedback and identifying actionable steps were vital for gaining interest holder support.

When we [District AIDS Council] first started working with you [the research team], I was hesitant and concerned that we would not receive any feedback from you. However, you have shown otherwise, this meeting [dissemination meeting] is so important, and I really appreciate all the sharing, feedback, and information (District AIDS Council representative, project dissemination meeting)

The expert consultations revealed how experts perceived the DAC, its potential impact, and some potential challenges. Participants welcomed the DAC as a sensitisation and action-orientated tool in these consultations. They highlighted that it is important to address the gaps in accessibility and inclusion in both post-GBV clinical and healthcare services. Some went as far as conceptualising the DAC as a disability audit tool.

The Disability checklist- it’s a great one, but the most important thing would be “action”. It is up to the disability advocate action going forward (expert in GBV and HIV sector)

Children with disabilities are not catered for at TCCs [post GBV clinical service centres]. There are no interpreters. Even in court, these children do not get a fair chance in terms of telling their stories. The Disability audit tool is needed (expert GBV sector)

The consultation provided specific feedback on necessary adaptations regarding missing elements and language adaptations. For instance, experts highlighted that some disability groups were better considered than others in the original version, that language needed to be adjusted or that elements were missing and needed to be added.

Upon closer inspection, we found that these documents [original tool] are almost exclusively angled towards wheelchair users, with only nominal mention of any other form of impairment (expert disability sector)

The reporting system /patient feedback is missing in the tool (expert disability sector)

This process resulted in 16 additional elements being added to the original Checklist in phase one. The language was made more precise, and the care pathway linkage domain was meaningfully reorganised, starting from intake forms and moving to referrals, monitoring, and evaluation processes. During the expert consultations, participants also discussed the need to incorporate the DAC into existing QA tool processes. While the DAC was integrated into a post-GBV QA tool in this project, the need for integration into a South African QA tool for PHC services, such as the ideal clinic tool [52], was also discussed. Furthermore, experts highlighted the need to provide healthcare workers with training and sensitisation around disability following a DAC assessment. They said this training also has to include community workers, who could be laypeople.

We need to find a way in which the tool can incorporate the role of community health care workers since they are the ones that go from house to house engaging with people with disabilities (expert disability sector)

Sensitisation and special training are crucial when working with people with disabilities. The tool can advocate for training (expert disability sector)

The team conducted an additional consultation workshop in phase two to develop the DAC intervention menu. The DAC and a draft menu were shared in preparation for the workshop with the broader disability sector. As a result of including additional interest holders, the team had to navigate the needs of new groups who had not been engaged in the first cycle of the design process. In some cases, this revealed important new suggestions on how to adapt the DAC further while ensuring that the menu can also identify feasible solutions for an LMIC. For instance, the blind sector revealed that very few people can read Braille, and Braille is not necessarily helpful in emergencies. Hence, even though Braille signing might be an international standard, it would be better to find audio solutions that are accessible to all South African people who are blind. The workshop led to the consensus to include text-to-voice options or QR codes into the Checklist instead of Braille.

Braille signage on walls is generally not usable as most blind people will not be feeling around the walls in the case of an emergency - wherever possible, solutions that use voice instructions are preferable. Only approximately 10% of the VI [Visually impaired] population are Braille literate (expert disability sector)

At other times, suggestions included very detailed or high-tech items, which were not feasible for a simple action-orientated tool that aims to be short, feasible, and sensitise and initiate change in resource-poor settings. For example, one suggestion was to provide headphones at each clinic for people with hearing impairments. This proposal was carefully discussed with healthcare workers and DOH representatives, who explained that this is impractical both for operational reasons and due to hygiene concerns in a clinical environment. The group agreed that a more practical and straightforward approach would be to assess whether health facilities can connect people with disabilities to services that provide assistive devices, including hearing aids, and follow up on whether those referred received these items.

As a basic requirement, reception areas must be equipped with an FM [frequency modulated] system with headphones for those with hearing loss, including the elderly. Later phases may include a telecoil installed for use by those wearing hearing aids or cochlear implants (expert disability sector)

The process of considering everyone’s needs while aiming to develop a short, feasible and action-orientated tool required consultations with different interest holders and sometimes several back-and-forth consultations with the same interest holders until a consensus could be found. Allowing fieldwork participants to share their experiences with the tool was also critical. This sharing allowed the team to showcase the impact of the DAC on healthcare services and their staff and motivated workshop participants to find feasible solutions before adding too many elements to the DAC itself. In this process, fieldwork participants highlighted that healthcare workers are willing to make changes but need assistance and feasible ideas for adjusting their work environment. These reflections became important in leading the co-design to focus on a concise checklist that has a fitting intervention menu, hence guiding the practical implementation of change with feasible solutions that are locally available.

I have learned a lot from the process [DAC assessment] and was willing to make changes in our care centres. However, we needed more assistance and ideas on how to make facilities accessible and responsive to the needs of people with disabilities. An intervention menu for the DAC will help other managers like me to identify more opportunities for change and ensure that no one is left behind (manager of participating health care facilities, DAT consultation meeting)

The consultations and sharing of material also led to utilising the DAC version one outside the project. For instance, one organisation for people with disabilities utilised the DAC to assess its impact on their community facilities. Again, the feedback from these additional experiences was discussed in the DAT consultative workshop. The users’ reflections strengthened the emphasis on the simple design of the DAC, which enabled lay persons, including those with disabilities, to utilise this tool and sensitise and educate healthcare workers about possible changes.

Our team [Organisation of Persons with Disabilities (OPD) in DAT workshop] is assessing health facilities, and these did not have basic accessibility elements such as ramps. Yet the assessment process itself made an immediate impact and initiated change, in particular, as people with disabilities themselves were involved. The DAC is a useful tool as it can be applied by laypersons, including people with disabilities. It is an action-orientated tool that educates and sensitises both healthcare workers and organisations of people with disabilities about what is needed to change health facilities. We approached building contractors to build ramps so that they could have access to the facilities (OPD representatives utilising the DAC, DAT consultative workshop)

The combination of the broad and ongoing consultation over two years, engagement with different interest holders, sharing of fieldwork experiences and consensus-building process led to the development of the DAT, including the DAC version two, its intervention menu and training.

Features and adaptations in the design phases

The two co-design cycles led to several features and adaptations, including the overall DAC design (title, cover, number of elements, outlines), assessment elements, intervention menu for all four domains, and answer scales. It also included the development of appreciative inquiry support tools such as automated RedCap reports, narrative reports, the DAC intervention menu, and the development of facilitator training. An overview of the features and adaptations is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Features and adaptations during the DAT development process

| Features | Cycle one development and testing of DAC version one | Cycle two development and testing of DAC version two and its intervention menu |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Design | ||

| Title and cover |

• Named checklist DAC to highlight the tool’s process orientation of raising awareness and initiating change • Designed cover with images of African people utilising health services |

• Inserted short instructions on process and training needs before DAC assessment tables |

| Number of DAC elements | 47 standards/elements | 53 standards/elements |

| Layout and structure |

• Designed data entry table layouts • Structured tables in four main domains and divided domains into subdomains |

• Added a table to enter all measurements at the beginning of the DAC assessment • Added numbers in front of each element to align quickly with the intervention menu (used the same numbers) |

| Content of DAC Assessment tool | ||

| Universal Design | 17 standards/elements | 21 standards/elements |

|

• Developed three sub-domains: (1) entrance to services (5), (2) reception, corridors and waiting rooms (9) and (3) examination rooms (3) • Adapted language and insertion of precise measurements according to international disability accessibility standards • Added elements for transport, parking, different types of doors (entrance, toilet, exam rooms), wide enough corridors and doorways, accessible emergency evacuation features, non-slip floors |

• Adapted three sub-domains: (1) entrance to services (6), (2) reception, corridors and waiting rooms (11) and (3) examination rooms (4) • Adapted language and checked the correct measurements according to South African building standards • Added elements on colour contrast of doors, ramps, steps and walkways and more detail to emergency evacuation processes to accommodate different types of disabilities • Removed directions in Braille and replaced them with verbal instructions and QR code maps (many blind people cannot read Braille) |

|

| Reasonable Accommodation | 13 standards/elements | 13 standards/elements |

|

• Developed two sub-domains: (1) Information and communication (7) and (2) assistance and support (6) • Moved features such as disability desk and adjustable beds to universal design domain • Added assistance to fill in forms, guide dogs, inclusion in routine satisfaction surveys and signages |

• Kept the number of elements the same • Added to medication boxes Braille signage option to have QR code instead • Added to the element of guide dogs, that facility must have a protocol in place on how to accommodate these dogs |

|

| Capacity of Staff | 6 standards/elements | 8 standards/elements |

|

• Separated disability from mental health training • Dropped element prompting if the facility has a staff member with a disability • Added training on emergency evacuation for people with disabilities |

• Replaced wording of “sensitisation training” with awareness training • Amended training element to reflect on GBV and disability-related violence training needs • Added element on disability guidelines for facility • Added available promotional or educational material for staff as this, in the absence of training, can provide the first guidance |

|

| Care pathway linkages | 11 standards/elements | 12 standards/elements |

| • Added elements into the “linkages domain” to follow people with disabilities through their care pathway, from screening and intake forms to treatment, referral and linkages with disability and rehabilitation services |

• Renamed domain “care pathway linkages” to show emphasis on the whole healthcare journey and alignment with the South African healthcare language • Adapted language to be more explicit on what is needed • Added an up-to-date directory of organisations for people with disabilities |

|

| Answer scale | • Stayed with the simple binary format of the original to keep the tool simple and user-friendly for less experienced facilitators and allow space for accepting feasible low-cost solutions |

• Stayed with a simple binary format, some academics made suggestions to include a graded answer scale to have more accuracy, this was declined by practitioners who felt a simple answer scale is more suitable for resource-poor settings as it allows low-cost solutions/innovations • Instead, included a graded solution option in the DAC intervention menu, facilitating the appreciated inquiry process |

| Implementation of Appreciative Inquiry | ||

| Result presentation |

• Developed DAC RedCap data entry tool and result tables to produce consolidated automatic reports with spider diagrams and tables • Added notes option to RedCap data entry tool |

• Added narrative reports for all facilities explaining RedCap results and summarising appreciative inquiries and recommendations |

| Communication techniques and discussions |

• Provided a RedCap summary report • Implemented DAC stages one and two • Experimented with appreciative inquiry techniques • Emphasised on staff autonomy to initiate change and collaborative discussion to identify at least three things that can be changed and how they can be changed |

• Trained staff with appreciative inquiry techniques and DAC stage one and two implementation • Developed draft DAC intervention menu to support fieldwork staff in the appreciative inquiry and provide suggestions for change • Ensured all clinics received a narrative report and kept this report confidential for the clinic staff |

| Linking to Interventions and Solutions |

• Identified the need to develop a document that lists potential solutions, as DAC facilitators are not familiar with everything available and do not have South African building standards • Connected facility managers to disability sector leadership where requested |

• Developed DAC intervention menu in exact alignment with the DAC assessment tool • Identified missing solutions for the DAC intervention menu, such as training, approved disability screening tools, data collection, as well as the need to improve procurement options (e.g. height adjustable beds) • Connected facilities to local Organisations of Persons with Disabilities (OPDs) |

| Type of facilitators | • The experienced research team who had conceptualised the project (PIs and CO-Is) | • Young people with and without disabilities who were new to the project |

| Identification of training and support tools for DAT | ||

| Training needs |

• Developed facilitator manual • Developed Standard Operation Procedures (SOP) for implementation |

• Developed a short training video for DAT facilitators in addition to the facilitator manual and SOP • Developed and piloted an online training course on GBV and disability for healthcare and social workers |

| Implementation needs | • Utilised electronic measuring tools such as angle and distance measurers on smartphones, some facilitators might need training with these |

• Trained fieldwork staff with supportive communication techniques • Trained team on the difference between screening and diagnostic tools, as not all facilitators are familiar with the difference |

Implementation of appreciative inquiry

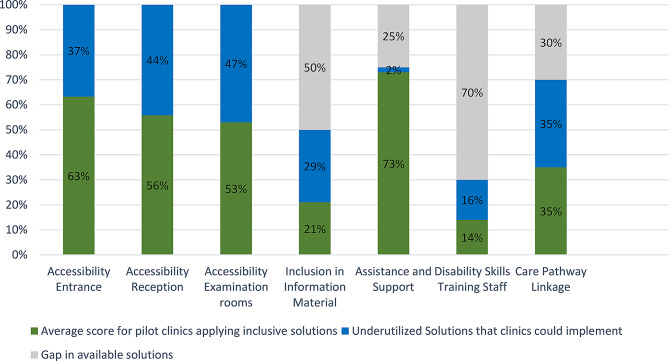

The DAC and its intervention menu were implemented in a two-stage process during a ‘DAC-visit’. In the first stage (assessment), facilitators used the DAC to assess the level of accessibility and preparedness of the health facility to service people with disabilities. Facilitating this process required assessment and synthesis skills from facilitators. The team developed a RedCap data entry and report template to support this process and designed a step-by-step facilitator guide and SOP. The RedCap report rapidly synthesised results with automated result tables and a simple visual spider diagram (Fig. 2). These were available to the team in real-time, directly after the DAC assessment. The fieldwork revealed that mobile data and a portable printer were crucial for this implementation as some health facilities did not have reliable internet, printers, or electricity. The simplicity of the spider diagram report emerged as an important feature for providing quick feedback regarding achievements and gaps (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Example of results in spider diagram for one health facility, results in percentage

The second stage (reflection) focused on discussing the results and finding feasible solutions to initiate change. Some lay facilitators found this process challenging, in particular when they struggled with capacity at under resourced clinics or if couldn’t identify feasible local solutions. This challenge highlighted the need to develop more support for facilitators. To address this, the team formalised the implementation of the appreciative inquiry techniques. It also engaged interest holders in a second design process to develop the DAC intervention menu (this had not been planned at the project’s outset). The team discovered that the appreciative inquiry technique was most effective when emphasising the participant’s strengths, particularly their agency to initiate change. Facilitators were trained to identify their agency (define) with facility staff and work together to identify potential approaches to improve their facility (dream). The intervention menu, mirroring the DAC, proved essential for proposing feasible solutions during the appreciative inquiry process design stage, where participants determined which elements to focus on and how to address them. This step-by-step process was vital for initiating willingness to change. Participants expressed that they initially expected poor results in the assessment, so the structured approach, guiding them from defining their strengths to identifying actionable solutions, was particularly valuable.

I knew, based on your questions, that we would not do well, but I appreciated the fact you came and showed us what needs to be done (Data Manager)

It was a good experience for us, and we are hopeful that step-by-step gaps identified will be closed (Operational Manager)

Furthermore, the fieldwork revealed that sharing and explaining results in narrative reports were important design aspects. While the Redcap reports provided quick, simple overviews of results through tables and spider diagrams, descriptive narratives explained the synthesised results and proposed solutions.

The report was very informative. I liked the background and table results, and they were easy to understand because we had a brief understanding of Redcap results (Nursing Assistant manager)

Findings in the post-design phase

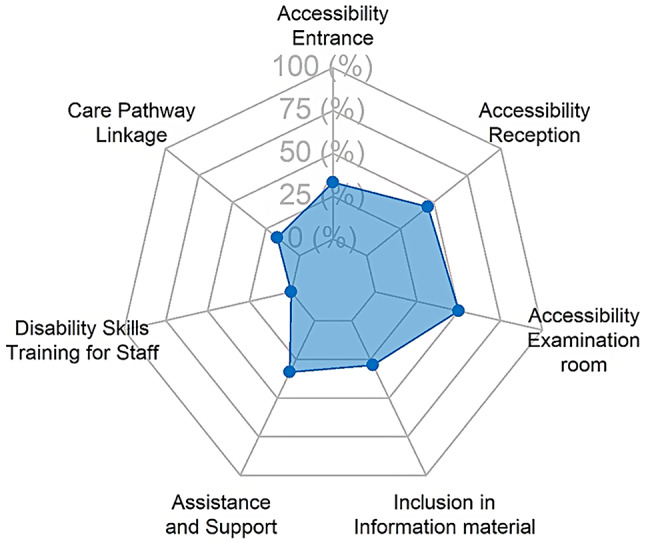

After fieldwork completion, the team synthesised the results in both design phases. This synthesis included descriptive statistics of the DAC results for all health facilities combined with mapping of available solutions in the DAC intervention menu. This process revealed two developmental aspects. Firstly, many health facilities were not utilising available solutions, even in the domain of universal access, which is regulated by building and facility standards that can be implemented in South Africa (Fig. 3, light blue bar part) [53]. The full results will be published in an upcoming paper.

Fig. 3.

Pilot results and gaps in available solutions for all pilot clinics combined

Secondly, the process revealed that some solutions were unavailable for certain elements in the DAC domains. This gap was evident for 50% of accessible/inclusive information elements, 25% of disability-related assistance elements in the reasonable accommodation domain, 70% for the capacity of staff elements (accredited disability skills training for staff), and 30% of essential care pathway linkages elements (Fig. 3, light grey bar part). These gaps included essential elements such as accredited disability etiquette training for health care workers (or other training), a disability screening tool for PHC, and patient forms that collect information on disability and reasonable accommodation needs [44, 45]. Hence, the post-design phase revealed further gaps that need further research and innovation.

The post-design phase also revealed important process information related to training needs for healthcare workers, acquisition challenges, and facilitator experiences.

For example, the need to develop accredited training on disability etiquette and disability and GBV had already been identified as an important next step during the fieldwork phases [44, 45]. The team piloted such training, which participants in the dissemination events welcomed, as they felt it would enable them to understand how to address the gaps in their facilities. Translating results into training opportunities was also perceived as an appropriate way to give back to participants and their facilities. It, therefore, could be a meaningful aspect of co-design.

I am also very excited about the ongoing training, very soon I will be able to close more gaps in disability in our clinic (nursing manager)

Post-design consultations also revealed how participants at sites had used the information from the pilot testing process and what aspects they implemented. For instance, some facility managers reported that the DAC assessment process gave them space to reflect and understand why people with disabilities do not come to their facilities. It also allowed them to identify errors in the procurement and building of structures and feasible solutions to fill identified gaps.

The DAC assessment process offered me an opportunity to reflect on my personal and professional role in the facility, and I realised that I had missed important elements of inclusivity and accessibility in our care centres. Clients with disabilities may not come to our facilities because they are not accessible, don’t respond to their health needs, or people with disabilities simply cannot get there. We have made mistakes when purchasing items such as doors, furniture, and bathroom sets. I discovered that our processes need updating as they don’t capture crucial information such as disability status and needs. I found that there were easy wins hidden within the DAC, such as linking to organisations for persons with disabilities (OPDs) or sending staff for disability etiquette training (manager participating health care facility, DAC meeting)

Post-design consultation in phase two also revealed why some existing solutions are challenging to implement. For instance, height-adjustable examination beds are available in South Africa but are more expensive and, therefore, less often ordered. Hence, participants expressed that this information needs to be further communicated and inform the country’s procurement system, which needs to negotiate better rates. Further consultations with DOH were therefore recommended.

Finding solutions for our gaps is important; some are easier implemented than others, and some need industry adjustments. For instance, I have tried to get height-adjustable beds, but they are very expensive. We need to be able to procure them at better rates (Department of Health representative, end of project consultation meeting)

The post-design work also revealed important aspects of the DAC facilitator training in cycle two, which included young people with disabilities who were new to research and facility assessments. The engagement with these facilitators revealed that ongoing training and support for the facilitators during implementation is important as more questions arise during the fieldwork. It also revealed that the DAC intervention menu was essential to support these DAC facilitators during the appreciative inquiry process.

Initially, I was nervous during the first visit, worried about making mistakes since it was my first time in the field… I had to learn about concepts such as screening tools to identify impairments in children and adults… The Intervention menu was instrumental for me in providing recommendations and conducting the DAC. After visiting several clinics, I gained confidence, became more comfortable with the process, and felt more at ease asking and answering questions (young person with disability facilitating DAC testing)

My experience working with the DAC was at first very nerve-racking because I was not confident enough. Through familiarising myself with the DAC and with continuous support from the team, I gained confidence and felt empowered to deliver a tool that assists healthcare providers in making their clinics more inclusive and accessible for people with disabilities (young person with disability facilitating DAC testing)

Discussion

This paper explores the co-development of the Disability Awareness Toolkit (DAT) and its potential to enhance disability inclusion and accessibility in health and post-GBV clinical services in South Africa. Our experience highlights co-design as a circular rather than a linear process that must be informed by the lived experience of people working in and using these services. Following Bird’s co-design framework, we moved through the pre-, co-, and post-design phases in two cycles. Each cycle revealed the need for further adaptation to refine implementation and maximise impact, leading to additional iterations [27]. Even after two cycles, key questions remain for a third cycle, which would doubtless lead to further amendments, including evaluating changes in participating facilities, identifying training needs, integrating the DAT into quality assurance processes, and ensuring the DAC and intervention menu stay relevant.

Furthermore, the DAT evolved as a dynamic tool, adaptable to different contexts and timeframes. What works in one setting may not work in another, requiring continuous flexibility and balancing of power dynamics. For example, well-resourced public health settings might benefit from a graded DAC answer scale. In contrast, less-resourced ones may want to keep it simple and even remove elements, such as guide dog support, if they are less relevant. Similarly, the specific adaptations suggested by blind participants in our study—such as using text-to-voice technology instead of Braille—highlighted the need to decolonise global and Western norms in favour of centring the voices and perspectives of people in our country. These examples underscore the importance of ongoing, locally informed adaptation in the co-design process.

Our work highlights the value of a co-design approach in developing quality assurance (QA) tools for change, such as the DAT. This approach ensures that end-user needs remain central to the QA process. For example, the DAC assessment was structured as a two-stage process, incorporating both an assessment and a reflection stage. However, our findings indicate that facilitating the reflection stage requires knowledge about providing feedback and which solutions are available for service providers. Facilitators required additional guidance, training, and support to navigate this stage effectively. This led to the developing of a simple assessment tool supported by an intervention menu, automated reports, and training resources. These aspects responded to the facilitator’s and staff’s need to create solutions without needing to be disability experts. While pilot testing has shown promising results for implementation, further impact evaluations are necessary to fully assess the DAT’s effectiveness as a developmental tool for driving change.

The importance of co-production in health interventions has been highlighted globally and has been reflected upon by another research team in KwaZulu-Natal. While co-developing a GBV prevention intervention, they emphasised the complexity and benefits of co-production [54]. Our experience with the co-design approach shares similar lessons to the KwaZulu-Natal study and aligns with Bird et al.‘s findings on leveraging the creative insights of end users, healthcare users, and providers to develop solutions that enhance disability inclusion and accessibility [27]. However, co-designing a tool in a middle-income country with the highest income inequality globally and with diverse populations and interest holders underscored the need for extensive consultations and the meaningful inclusion of various groups, particularly hard-to-reach populations such as people with disabilities. In our study, this required openness to expanding consultations, iterating on the tool multiple times, and addressing power dynamics and varying needs. It also demanded a pragmatic balance between feasibility, within the current context, and identifying critical gaps—such as the need for training and screening tools—that must be addressed in future projects.

The strong interest holder engagement and widespread buy-in raised key questions about the tool’s implementation. Initially designed for post-GBV clinical care, its potential application in public healthcare facilities beyond those offering GBV care emerged as a crucial consideration. In South Africa, it also became evident that the tool could contribute to broader quality assurance (QA) initiatives, such as the Ideal Clinic program and the ongoing National Health Insurance (NHI) efforts. Future consultations must explore how best to integrate the tool (or parts of it) into these processes and determine which QA mechanisms can be leveraged for effective implementation.

Generally, disability-inclusive QA processes could assist in providing quality care to persons with disabilities through continued monitoring, assessment, and improvement efforts. However, inclusive QA in healthcare has been largely absent [4]. In South Africa, the “Ideal Clinic” is a formalised healthcare QA tool [52]. An ideal clinic has “good infrastructure, adequate staff, adequate medicine and supplies, good administrative processes, and sufficienct bulk supplies…” [52]. The associated ideal clinic checklist has been developed to assess health facilities in South Africa against various standards. Although the Checklist is comprehensive for general healthcare, it lacks basic disability-inclusion and accessibility assessment features. It includes only a few questions on the availability of wheelchairs, access for people in wheelchairs (including entrance, ramps, and toilets), and access to allied health practitioners [52]. Recently, new healthcare disability audit tools have also been developed in other settings [21, 23]. However, these tools are either very long, look only at accessibility features, do not consider the care pathway and/or have not been field tested [21]. In addition, very few disability audits or assessment tools have been peer-reviewed and tested for LMIC [21]. None of them used a co-design approach [21]. As such, the question has been posed as to whether the DAT could be added to the ideal clinic assessment process or if the DAT should be used to inform adaptations of the ideal clinic checklist. Both are plausible, but co-design processes and consultations should determine the more practical method.

Furthermore, the DAT field testing results highlight the tool’s potential to identify gaps in service delivery and opportunities for change in each facility, echoing work from other colleagues adapting this tool. For instance, the work by Mactaggart et al. is exciting as it built on the DAC version one (cycle one) and adapted it further for the context of Uganda in 2024 [21]. The authors adapted the tool to include 71 elements/indicators. The field testing revealed an accessibility score of 17.8% with a median of 21 suggested changes per facility [21]. This result highlights low baseline accessibility levels and how the tool identified numerous opportunities to improve facilities for better disability inclusion and accessibility. This study indicates that the tool has potential for application beyond South Africa, provided it undergoes an in-country co-design and adaptation process. A notable outcome of co-design in different contexts is the evolving differences in how DAC assessment elements are applied and how results are discussed with facility staff. For instance, the Ugandan team adapted the DAC by incorporating additional elements in the assessment stage while maintaining informal discussions during the reflection stage to identify opportunities for change, as outlined in the original DAC version [21].

In contrast, our study aimed to keep the DAC assessment concise (with fewer elements that have feasible solutions available) and took an additional step during the reflection stage by formalising discussions using the appreciative inquiry approach, complemented by a supporting intervention menu. Insights from other researchers on the co-design process, the facilitation of DAC visits and inquiries, the nature of adaptations made, and their resulting outcomes provide valuable learning opportunities for future efforts. These insights should be further explored as the tool is implemented to promote disability inclusion and accessibility in healthcare services beyond the scope of our study, potentially within a community of practice.

Lastly, this paper was written two months before the 2024 World Disability Summit in Berlin, where the Global Disability Inclusion Report (GDIR) was released [55]. Among several key recommendations, the GDIR advocates “implementing and enforcing accessibility standards and action plans” and “enhancing the participation of persons with disabilities” [55]. In this context, the evolution of the DAT highlights the importance of co-design in informing how the development of inclusive healthcare assessment and interventions can include people with disabilities, hence implementing the principle of ‘nothing about us without us’. Our experience underscores the need for a cyclical co-design process with local interest holders, where standards and solutions are continuously adapted to align with emerging innovations, from local low-cost solutions to international technological advances. It demonstrates how inclusive, locally grounded, and flexible design processes can produce meaningful quality assurance tools that reflect the diverse realities of service users and providers in unequal contexts. It also created awareness of the challenges people with disabilities face and how awareness and advocacy can contribute towards change.

Abbreviations

- AIDS

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- CRPD

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

- DAC

Disability Awareness Checklist

- DAT

Disability Awareness Toolkit

- DOH

Department of Health

- GBV

Gender-Based Violence

- GDIR

Global Disability Inclusion Report

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- JAWS

Job Access with Speech

- LMIC

Low-and-middle income

- NHI

National Health Insurance

- PHC

Primary Health Care

- QA

Quality Assurance Tool

Author contributions

JHH conceptualised this study, designed and adapted the tools, trained and supervised the fieldwork team and conducted the analysis. She also wrote the first and final draft of this paper. TN coordinated the study, collected and entered data and reviewed the draft and final paper, SW conceptualised the study, collected and entered data and reviewed the draft and final paper, NZ & SM collected and entered data and reviewed the draft and final paper, AM supervised fieldwork, lead interest holder engagement at DOH and reviewed the draft and final paper, TP designed and adapted the tools and reviewed the draft and final paper, JL & TM facilitated the interest holder engagements, reviewed the developed tools and reviewed the paper and BC designed and adapted the tools, supported the fieldwork team, managed the data entry and cleaning and analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the South African Medical Research Council.

Data availability

Data will be provided upon written request to the authors.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was granted by the Department of Health and the South African Medical Research Council (EC028-6-2021). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Authors information

JHH is a Chief Specialist Scientist and disability researcher with a disability. and over 20 years of research and implementation experience, TN is a Technologist with 10 years of study implementation experience, SW is a Senior Specialist Scientist and GBV researcher who has over 20 years of research and implementation experience, NZ & SM are young researchers with disability who conducted research for the first time in this study, AM is a public health practitioner who coordinates crisis and PHC centres and has over 20 years experience in health and post-GBV care delivery, TP a public health and disability researcher with over 10 years experience, JL was a disability sector representative and person with disability with over 10 years experience, TM is a disability sector representative and young person with disability, BC is a Senior Researcher on disability, health and data science with 10 years experience.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

^Deceased: Jacques Lloyed.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kuper H, Azizatunnisa L, Rodriguez G, Denae, Rotenberg S, Banks LM, Smythe T, Heydt P. Building disability-inclusive health systems. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9:e316–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuper H, Hanass-Hancock J. Framing the debate on how to achieve equitable health care for people with disabilities in South Africa. South Afr Health Rev 2020:45–52.

- 3.Kuper H, Rotenberg S, Azizatunnisa L, Morgen-Banks L. The association between disability and mortality: a mixed-method study. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9:e306–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organisation. Global report on health equity for persons with disabilities. Geneva: WHO; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gréaux M, Moro MF, Kamenov K, Russell AM, Barrett D, Cieza A. Health equity for persons with disabilities: A global scoping review on barriers and interventions in healthcare services. Int J Equity Health. 2023;22:2–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Missing Billion Initiative, Clinton Health Access Initiative. Reimagining health systems that expect, accept and connect 1 billion people with disabilities. A follow-on to the first missing billion report. London: The Missing Billion Initiative, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunkle K, Van der Heijden I, Stern E, Chirwa E. Disability and violence against women and girls global programme. vol. July 2018 brief. London: What Works; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Beaudrap P, Benningguisse G, Moute C, Dongmo Temgoua C, Kayiro PC, Nizigiyimana V, Pasquir E, Zerbo A, Beautwanyo E, Niyondiko D, Ndayishimiye N. The multidimensional vulnerability of people with disability to HIV infection: results from the handiSSR study in Bujumbura, Burundi. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Beaudrap P, Beninguisse G, Pasquier E, Tchoumkeu A, Touko A, Essomba F, Brus A, Aderemi TJ, Hanass-Hancock J, Eide AH, et al. Prevalence of HIV infection among people with disabilities: a population-based observational study in Yaoundé, Cameroon (HandiVIH). Lancet-HIV. 2017;4:e161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashemi G, Wickenden M, Bright T, Kuper H. Barriers to accessing primary healthcare services for people with disabilities in low and middle-income countries, a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Disabil Rehabilitation. 2022;44:1207–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanass-Hancock J. Disability and HIV/AIDS - A systematic review of literature in Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2009;12:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohleder P, Swartz L, Schneider M, Henning Eide A. Challenges to providing HIV prevention education to youth with disabilities in South Africa. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:619–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rohleder P, Swartz L, Schneider M, Eide H. HIV/AIDS and disability organisations in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2010;22:221–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohleder P, Leslie Swartz L. Providing sex education to persons with learning disabilities in the era of HIV/AIDS: tensions between discourses of human rights and restriction. J Health Psychol. 2009;14:601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dickman B, Roux A, Manson S, Douglas G, Shabalala N. How could she possibly manage in court?’ An intervention programme assisting complainants with intellectual disabilities in sexual assault cases in the Western Cape. In Disability and social change: a South African agenda. Edited by Watermeyer B, Swartz L, Lorenzo T, Schneider M, Priestley M. Cape Town: HSRC Press 2006: 116–133.

- 16.Van Eggerat L, Hanass-Hancock J, Myezwa H. HIV-related disabilities: an extra burden to HIV & AIDS health care? AJAR Afr J AIDS Res. 2015;14:285–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rotenberg S, Chen S, Hanass-Hancock J, Davely C, Banks LM, Kuper H. Do people with disabilities have the same level of HIV knowledge and access to testing? Evidence from 513,252 people across 37 multiple indicator cluster surveys. J Int AIDS Soc. 2024;27:e26239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aderemi T. Sexual abstinence and HIV knowledge in school-going adolescents with intellectual disabilities and nondisabled adolescents in Nigeria. J Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2013;25:161–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuper H, Heydt P. The missing billion. Access to health services for 1 billion people with disabilities. London: London School for Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.United Nations. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. UN; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Mactaggart I, Sentoogo Ssemata A, Menya A, Smythe T, Rotenberg S, Marks S, Bannink Mbazzi F, Kuper H. Adapting and pilot testing a tool to assess the accessibility of primary health facilities for people with disabilities in Luuka District, Uganda. Int J Equity Health. 2024;23:10–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vergunst R, Swartz L, Hem K. E: access to health care for persons with disabilities in rural South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organisation. Disability-Inclusive health service Toolkit. A resource for health facilities in the Western Pacific region. Geneva: WHO; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Rooy Ggun, Amadhila EM, Mufune P, Swartz L, Mannan H, MacLachlan M. Perceived barriers to accessing health services among people with disabilities in rural Northern Namibia. Disabil Soc. 2012;27:761–75. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eide A, Mannan H, Khogali M, van Rooy G, Swartz L, Munthali A, Hem K, MacLachlan M, Dyrstad K. Perceived barriers for accessing health services among individuals with disability in four African countries. Plos 1. 2015;10:e0125915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanass-Hancock J, Alli F. Closing the gap: training for health care workers and people with disability on the interrelationship of HIV and disability. Disabil Rehabilitation. 2015;37:2012–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bird M, McGillion M, Chambers E, Dix J, Fajardo C, Gilmour M, Levesque K, Lim A, Mierdel S, Quellette C, et al. A generative co-design framework for healthcare innovation: development and application of an end-user engagement framework. Res Involv Engagem. 2021;7:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.South African National AIDS Council. Nothing about Us without Us: HIV/AIDS and disability in South Africa. Cape Town: South African National AIDS Council; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh DR, Sah RK, Simkhada B, Darwin Z. Potentials and challenges of using co-design in health services research in low- and middle-income countries. Global Health Res Policy. 2023;8:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanass-Hancock J, Willan S, Carpenter B, Tesfay N, Dunkle K. Disability awareness checklist for health care services. Durban: South African Medical Research Council; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanass-Hancock J, Willan S, Carpenter B, Tesfay N, Dunkle K. Disability awareness checklist. Facilitator guide. Durban: South African Medical Research Council; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanass-Hancock J. Interweaving conceptualisations of gender and disability in the context of vulnerability to HIV/AIDS in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Sex Disabil. 2009;27:35–47. [Google Scholar]

- 33.UNAIDS. Disability and HIV reference report. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanass-Hancock J, Molefhe M, Taukobong D, Mthethwa N, Keakabetse T, Pitsane A. ALIGHT Botswana. From Understanding the context of violence against women and girls with disabilities to actions. Research report. Durban: SAMRC; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanass-Hancock J, Grant C, Strode A. Disability rights in the context of HIV and AIDS: A critical review of nineteen Eastern and Southern Africa (ESA) countries. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:2184–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanass-Hancock J, Carpenter B, Myezwa H. The missing link: exploring the intersection of gender, capabilities and depression in the context of chronic HIV. Health Place. 2016;59:1212–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dickman B, Roux A. Complainants with learning disabilities in sexual abuse cases: a 10-year review of a psycho-legal project in cape Town, South Africa. Br J Learn Disabil. 2005;33:138–44. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wazakili M, Mpofu R, Devlieger P. Should issues of sexuality and HIV and AIDS be a rehabilitation concern? The voices of young South Africans with physical disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2009;31:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wazakili M, Mpofu R, Devlieger P. Experiences and perceptions of sexuality and HIV/AIDS among young people with physical disabilities in a South African township: a case study. Sex Disabil. 2006;24:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watermeyer B, Schwartz L, Lorenzo T, Schneider M, Priestley M. Disability and social change: a South African agenda. Cape Town: HSRC; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kvam MH, Braathen SH. I thought… maybe this is my chance: sexual abuse against girls and women with disabilities in Malawi. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment 2008;20:5–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Kvam MH, Braathen SH. Violence and abuse against women with disabilities in Malawi. In SINTEF health report. pp. 1–65. Nor SINTEF; 2006:1–65.

- 43.Hanass-Hancock J, Mthethwa N, Molefhe M, Keakabetse T. Preparedness of civil society in Botswana to advance disability inclusion in programmes addressing gender-based and other forms of violence against women and girls with disabilities. Afr J Disabil. 2020;9:a664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hanass-Hancock J, Ndlovu T, Carpenter B, Willan S. Field testing a quality assurance tool for assessing the quality of post-gender-based violence care services in clinical settings in South Africa. Fieldwork report. Durban: South African Medical Research Council; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanass-Hancock J, Ndlovu T, Carpenter B, Mhlongo S, Zululu N. Disability awareness checklist and intervention Menu. Fieldwork results eThekwini 2024. Durban: South African Medical Research Council; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ndlovu T, Hanass-Hancock J, Carpenter B. Disability-inclusion in health and post-GBV clinical services. Pilot short course for health professionals, social workers, and other professionals working with survivors of GBV. Evaluation report. Durban: South African Medical Research Council; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hanass-Hancock J, Willan S. Introducing the post-GBV care quality assurance tool for use in South Africa. UMgungundlovu and Ekhurhuleni fieldwork mobilisation meeting report June 2022. Durban: South African Medical Research Council; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanass-Hancock J, Dunkle K, Ndlovu T. Disability awareness Checklist. Meeting report 28 & 29 August 2023. Durban: South African Medical Research Council; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruhe MC, Bobiak SN, Litaker D, Carter CA, Wu L, Schroeder C, Zyzanski SJ, Weyer SM, Werner JJ, Fry RE, Stange KC. Appreciative inquiry for quality improvement in primary care practices. Qual Manag Health Care. 2011;20:37–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luhalima T, Mulaudizi F, Phetlu D. Use of an appreciative inquiry approach to enhance quality improvement in the management of patient care. Archives Intern Med Res. 2022;5:357–63. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zukulu N, Nlovu T, Mhlongo S. Enhancing care: addressing GBV for vulnerable populations in South Africa. Durban: SAMRC; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 52.South African Department of Health. Ideal clinic Manual. April 2022. Pretoria: DOH; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 53.South African Bureau of Standards. The application of the National Building regulations. Pretoria: SABS; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mannell J, Washington L, Khaula S, Khoza Z, Mkhawanzi S, Burgess RA, Brown LJ, Jewkes RJ, Shai N, Willan S, Gibbs A. Challenges and opportunities in coproduction: reflections on working with young people to develop an intervention to prevent violence in informal settlements in South Africa. BMJ Global Health. 2023;8:e011463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cote A, Banks LM. Global disability inclusion Report. A Multi-stakeholder report for the global disability summit 2025. Berlin: BMZ Germany, IDA and Kingdom of Jordanian; 2025. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided upon written request to the authors.