Abstract

Abstract

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is one of the most aggressive malignancies, with early detection being crucial for improving patient outcomes. Serum biomarkers, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and pro-gastrin releasing peptide (ProGRP), play significant roles in the early screening and pathological classification of SCLC. In the study, the affinity peptides of NSE and ProGRP were screened by phage display technology, which were then assessed for binding affinity using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and biolayer interferometry (BLI). Circularly permuted fluorescent protein (cpFP) probes were constructed by genetically encoding the selected peptides as binding domains. The E1 probe for NSE and the P10 probe for ProGRP demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in detecting their respective targets. The E1 probe with a concentration of 4 μg/mL reacted well with NSE (1–16,000 ng/mL), and the reaction exhibited a good linear relationship when the NSE concentration was between 1 and 100 ng/mL. The 4 μg/mL P10 probe reacted well with ProGRP (0.01–2000 ng/mL) and showed good linear relationship between 0.01 and 50 ng/mL. Clinical validation revealed that adjusting the upper limit of normal concentrations significantly improved the probes’ diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for SCLC. These probes offer a high-sensitivity, specific, rapid, and cost-effective approach to SCLC detection, holding promise for early diagnosis and improved patient management .

Key points

In this study, peptides targeting NSE and ProGRP were selected by phage display technology, and the peptides obtained have good affinity with the corresponding proteins.

Based on R-GECO1, cpFP probes were constructed using peptides as binding domains, and E1 probe for NSE and P10 probe for ProGRP were obtained.

E1 probe and P10 probe have good sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of SCLC.

Keywords: Small cell lung cancer, Neuron-specific enolase, Pro-gastrin-releasing peptide, Peptides, Phage display, Circularly permuted fluorescent protein

Introduction

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is one of the most lethal of malignancies, accounting for approximately 13–15% of lung cancer cases (Megyesfalvi et al. 2023), which is characterized by highly aggressive, rapid growth, early metastasis, and resistance to conventional treatments, resulting in a 5-year survival rate of only about 6.4% (Lee et al. 2023). The diagnosis of SCLC primarily relies on the morphological features of cancer tissue, which is difficult to obtain and requires invasive procedures (Stewart et al. 2020). As a result, histological diagnosis is not recommended for screening and early diagnosis, leading to most SCLC cases being diagnosed at an advanced stage, significantly reducing the cure rate of the malignant tumor (Harmsma et al. 2013). Early detection, accurate classification, and close monitoring of SCLC are imperative for optimal clinical outcomes. Analyzing tumor markers in easily accessible specimens such as blood, sputum, or urine can provide a patient friendly and effective method for screening and diagnosis (Qian et al. 2024). Research has shown that neuron-specific enolase (NSE) and pro-gastrin-releasing peptide (ProGRP) are ideal indicators for assisting in the diagnosis of SCLC, playing an indispensable role in screening and pathological classification of lung cancer (China 2022). At present, the commonly used methods for detecting NSE and ProGRP include electrochemiluminescence, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and radioimmunoassay. Despite being very mature, these methods are complex to operate, require large equipment, and have high costs, making them difficult to popularize (Cao et al. 2022). Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop a low-cost, easy to operate, accurate, and rapid detection method to facilitate the screening of SCLC.

Affinity peptides, chains of amino acids ranging from 2 to 50 residues, exhibit a multitude of biological functions dictated by their specific sequences (Gomes et al. 2018). They are characterized by their enormous chemical diversity, excellent biological recognition ability, and high biocompatibility, which allow them to traverse cell membranes without triggering immune responses (Wang et al. 2022). Affinity peptides screened through phage display technology and modified at specific sites for conjugation to imaging probes or drugs have seen a surge in biomedical applications (Saw et al. 2021). Circularly permuted fluorescent protein (cpFP) represents an innovative class of fluorescent protein. Its design hinges on linking the initial N-terminus and C-terminus with a peptide chain while maintaining the original conformation of the fluorescent protein. By strategically opening the peptide chain to create new termini, these are then connected to a binding domain protein that responds specifically to a target of interest. Upon binding, the fluorescent protein’s chromophore undergoes a conformational change, enabling the monitoring of the target (Jiang et al. 2024). The cpFP’s exposure of chromophores to the external environment renders it highly sensitive to even minor conformational alterations, leading to detectable shifts in fluorescence (Zhao et al. 2011a, b). Moreover, the fluorescence intensity of cpFP has the advantages of broad dynamic range (Kostyuk et al. 2019) and high signal-to-noise ratios (Sakaguchi et al. 2009). Circularly permuted fluorescent protein (cpFP) represents an innovative class of fluorescent protein. Its design hinges on linking the initial N-terminus and C-terminus with a peptide chain while maintaining the original conformation of the fluorescent protein. By strategically opening the peptide chain to create new termini, these are then connected to a binding domain protein that responds specifically to a target of interest. Upon binding, the fluorescent protein’s chromophore undergoes a conformational change, enabling the monitoring of the target (Jiang et al. 2024). The cpFP’s exposure of chromophores to the external environment renders it highly sensitive to even minor conformational alterations, leading to detectable shifts in fluorescence (Zhao et al. 2011a, b). Moreover, when the structural domain is located within the sensitive region of the chromophore, the fluorescence intensity fluctuates. The effective conformational coupling between the sensory and reporting unit endows cpFP with a significant advantage of a broad dynamic range (Kostyuk et al. 2019). Beyond small molecules and ions, proteins with relatively moderate conformational rearrangements can be tested as sensory units, and cpFP can provide affordable signal-to-noise ratios for measurement (Sakaguchi et al. 2009).

At present, the detection of macromolecular proteins has mostly relied on antibodies. However, the complex structure and high cost of antibodies limit their application as cpFP probe binding domain proteins. On the contrary, the synthesis of affinity peptides is highly pure and reproducible. Using affinity peptides instead of antibodies as binding domain proteins to construct cpFP probes can significantly reduce the production cost of probes and facilitate the widespread popularization and application of probes (Premchanth et al. 2024). In addition, phage display technology, developed by Smith in 1985 and recognized with the 2018 Nobel Prize (Stiltner et al. 2021), is a highly effective method for peptide screening. It enables the presentation of numerous peptides on the surface of a bacteriophage, capable of binding to targets with high specificity and affinity (Zhang et al. 2023). Then, affinity peptides can be served as adaptive elements for cpFP probes after modifications, enhancing their selectivity, reliability, and sensitivity (Jahandar-Lashaki et al. 2025; Gyuricza et al. 2021), to ensure rapid and accurate detection of target protein.

Taken together, this study obtained affinity peptides for NSE and ProGRP through phage display, and constructed cpFP using affinity peptides as binding domain proteins to realize the highly sensitive, specific, rapid, and cheap detection of NSE and ProGRP (Figs. 1 and 2), providing powerful tools for early screening and diagnosis of SCLC.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for constructing probes based on cpFP and using affinity peptides screened by phage display as binding domains

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the cpFP probe construct

Materials and methods

Phage display

The library panning was performed in the 96-well plate coated with NSE or ProGRP using a Ph.D.−12 Phage Display Peptide Library Kit (E8110SC, New England BioLabs, MA, USA). According to the protocol, 100 μg/mL of target protein in bicarbonate buffer (pH 8.6) was coated on plates at 4 ℃ overnight, and an equal volume of bicarbonate buffer was added to the control well. Following blocked with bovine serum albumin (BSA), the protein-coated plates were incubated with phages for 60 min on a shaker at room temperature. The unbound phages were removed by TBST buffer (TBS buffer + 0.1% Tween-20) for ten times, and the bound phages were eluted by Glycine-BSA buffer (0.2 M glycine–HCl, 1 mg/mL BSA, pH 2.2) and amplified for next round of panning. After three rounds of screening, 30 blue single colonies on the solid Luria–Bertani (LB) culture plate were randomly selected for sequencing by dideoxy sequencing of phage DNA (Zhang et al. 2022).

ELISA

Based on the sequencing results, amplified monoclonal phages were tested for their affinity for the corresponding marker by ELISA. Wells of a 96-well plate were coated with the protein (100 μg/mL, 200 μL/well) and blocked with 300 μL of BSA. Approximately 1010 phage particles (100 μL) were added to each well and incubated for 1 h at 37 ℃. The plates then were washed six times with TBST buffer, and incubated with secondary horseradish peroxidase labeled anti-M13 antibody (100 μL, 11,073, SinoBiological, Beijing, China) at a dilution of 1:5000 for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, the color was developed by o-phenylenediamine substrate solution (OPD, P6662, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) in dark and visualized at 492 nm. The experiment was repeated three times, with five replicates each time.

Peptide synthesis

Based on the above results, the affinity peptides were synthesized using the standard solid-phase fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl method (Synpeptide Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). The products were purified to a minimum purity of 95% by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and were analyzed and identified by mass spectrometry (MS).

Biolayer interferometry (BLI)

The binding affinities of peptides to NSE or ProGRP were tested on an Octet RH96 instrument with Octet BLI Discovery 12.2.1.18 (Octet RH96, Sartorius AG, Goettingen, Germany). NSE and ProGRP were immobilized onto amine reactive second-generation biosensors (AR2G, 18–5095, Sartorius AG, Goettingen, Germany) by amine coupling, and remaining sites were quenched with ethanolamine, and the peptides were diluted in several gradient concentrations. Each measurement consisted of three steps: 60 s of baseline step, 90 s of association step, and 180 s of dissociation step. All experiments were carried out at room temperature. Five replicate wells were used for each concentration, and the dissociation constant (KD) was calculated using Octet Data Analysis software 11.0 on the raw data. The results were graphically presented using WPS Office Excel (12.1.0.16929).

Plasmid construction

R-GECO1, a cpFP was used as a template for the engineering of the probes (Zhao et al. 2011a, b). Through LBI detection, two peptides with high affinity were selected for each serum tumor marker, and two strategies were used to construct the plasmids (Fig. 3). The two peptides were used as the N-terminal and C terminal of cpFP respectively in the first strategy, while the dodecapeptides were divided into two hexapeptides to insert into the N-terminal and C-terminal of cpFP in the second strategy. As a result, three sequences were obtained for each marker and were inserted in pRSETB between BamHI and EcoRI sites with a 6 × His tag.

Fig. 3.

The strategy for the construction of the cpFP probe. A Using R-GECO1 as a template, the cpFP probe was constructed with two selected dodecapeptides as the N-terminus and C-terminus, respectively. B Using R-GECO1 as a template, the cpFP probe was construced with two hexapeptides separated from the selected dodecapeptide as the N-terminus and C-terminus. The black wavy lines represented the linker between the cpFP and peptide

Protein expression and purification

The plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3, CB105-02, Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China) cells before protein expression. The cells were grown in LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/mL ampicillin (A8180, Saituo, Dalian, China) for 6 h at 37 ℃ with 220 rpm shaking and induced by isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, 0.5 mM, AGM1483, Aogma, Shanghai, China) for 4 h at 17 ℃ with 170 rpm shaking. The bacterial pellets were collected and then disrupted by sonication in lysis buffer (10 nM imidazole, 50 nM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.4), which were subjected to centrifugation at 12,000 rpm at 4 ℃ for 20 min to obtain the supernatant solution. Protein purification was performed using an AKTA protein purification instrument (Pure L1, GE healthcare, MA, USA). Finally, the protein was dialyzed at 4 ℃ in PBS for 4 h, immediately packaged and stored at − 80 ℃.

Fluorescence detection

Fluorescence detection was carried out at room temperature using a microplate reader (Infinite E Plex, Tecan, Grodlg, Austria). The excitation wavelength was set at 490 nm, and the emission wavelength was set at 600 nm for fluorescence detection. To measure the sensitivity, specificity, and standard curve of the probes, the reaction system was made up of 20 μL solution of substance to detect, including BSA, NSE, ProGRP, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCCAg), and cytokeratin fragment 19 (CYFRA21-1), and 180 μL probe solution. F0 was set as the basic fluorescence intensity in PBS, and the result was represented by F/F0 as the change in fluorescence intensity. When the probe was used to detect serum, a background control was set which consist of 180 μL PBS and 20 μL serum, with the fluorescence value defined as F1. The fluorescence value of detection well was obtained by reaction of 180 μL probe solution and 20 μL serum, which defined as F2. The final result was represented by (F2-F1)/F0, and substituted it into the standard curve to calculate the concentration of the target protein.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed based on the Student’s t test or one-way analysis of variance, followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad software (v9.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). P < 0.05 was regarded as a statistically significant difference.

Results

Biopanning for binding peptides and peptide sequence analysis

In order to screen specific protein or peptides, the phage display technology was used in which exogenous proteins or peptides were fused with phage coat proteins and displayed in the phage surface, and achieved screening by specific binding to the targets. The specific phage with highest specificity were identified and enriched by three rounds of biopanning and increasing the concentration of Tween 20 and washing times. Phage sequencing showed that there were six peptides specifically binding to NSE, and 11 peptides specifically binding to ProGRP (Table 1).

Table 1.

Peptide sequence of the selected binding phage

| NSE | ProGRP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Peptide sequence | Repetition | No | Peptide sequence | Repetition |

| E1 | FGSAKNILNCCY | 6 | P1 | SVYNALYLAASE | 10 |

| E2 | SKPDCSTVGGPR | 2 | P2 | KIWLIPGGDVLA | 4 |

| E3 | EHAPHPLGGSNS | 1 | P3 | TFSKVWIVSKDT | 2 |

| E4 | SLRLDVPAQWTM | 1 | P4 | KVWLMESPIKEW | 2 |

| E5 | LHRYDDRATLAN | 1 | P5 | SVYNALYQAASE | 1 |

| E6 | VPMPAFDLHDGF | 1 | P6 | LHAYSALVYPPK | 1 |

| P7 | MSDTNTKRTLTE | 1 | |||

| P8 | SVRDFYLWSSHS | 1 | |||

| P9 | VVGRAMAYSTIP | 1 | |||

| P10 | SVDYSRDHIASE | 1 | |||

| P11 | SFSKVWIVSKDA | 1 | |||

Then, the monoclonal phage ELISA was performed based on the sequence results to evaluate the affinity of the selected phage to the target protein. The results indicated that the screened phages bind to correspond protein with high affinity, confirming the validity of the biopanning. According to the repetition of the sequence in the biopanning and the affinity suggested by ELISA, three peptides were selected for NSE and ProGRP, respectively, for subsequent experiment, with E1, E2, and E5 for NSE (Fig. 4A), and P2, P3, and P10 for ProGRP (Fig. 4B). P5 was excluded because of the high sequence repeatability of the P5 and the peptides screened by other experiments in our laboratory, although ELISA indicated that P5 and ProGRP had the highest binding force.

Fig. 4.

The binding affinity of the screened binding phages. Absorbance values measured at 450 nm from ELISA assays for NSE (A) and ProGRP (B). *P < 0.05 vs. control group (n = 3)

Affinity analysis of screened peptides

Through the above experiments, three peptide sequences with high affinity for NSE or ProGRP were obtained. The peptides were synthesized and further evaluated the binding force by BLI detection. The equilibrium KD is an index to evaluate molecular interaction. The smaller KD is, the greater affinity is. The results in Fig. 5A showed that E1 (KD = 7.40E—08) and E5 (KD = 2.90E—08) displayed stronger binding to NSE compared with E2 (KD = 1.00E—06). Figure 5 B showed P2 (KD = 9.50E—08) and P10 (KD = 4.20E—08) displayed stronger binding to ProGRP compared with P3 (KD = 1.60E—07).

Fig. 5.

Affinity analysis of screened peptides. The binding affinities of the screened peptides to corresponding serum tumor markers was detected by BLI assay. a Determination of the KD for the interaction between E1, E2, E5, and NSE respectively. b Determination of the KD for the interaction between P2, P3, P10, and ProGRP respectively

Sensitivity detection of the probe

According to the results of BLI detection, two peptides for each marker were selected to construct the probes. Using R-GECO1 as the template, cpFP probes were constructed by connecting the peptides as the N-terminal and C-terminal of R-GECO1 through two strategies. Three probes were constructed for each marker. At the same concentration (4 μg/mL), E1 (Fig. 6A) probe which was obtained by connecting the two hexapeptides separated from E1 to the C-terminal and N-terminal, showed the highest fluorescence value after reacting with NSE. And it was found that among the probes synthesized for ProGRP, P10 (Fig. 6B) had the highest sensitivity.

Fig. 6.

Sensitivity detection of the probe. Based on R-GECO1, the probes were constructed and synthesized according to the strategies, and the sensitivity of the reaction between each probe and corresponding tumor marker was detected. a Fluorescence values of PBS, E1 probe, E1-5 probe, and E5 probe mixed with NSE respectively tested by a microplate reader. b Fluorescence values of PBS, P2 probe, P2-10 probe, and P10 probe mixed with proGRP respectively tested by a microplate reader

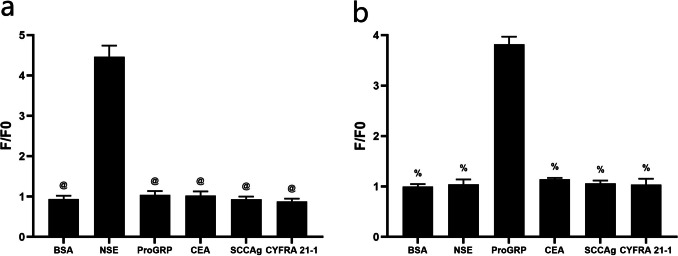

Specificity detection of the probes

In combination with the previous experimental results, E1 probe and P10 probe were selected as cpFP probes of NSE and ProGRP in the study. To verify the specificity, BSA, NSE, ProGRP, CEA, SCCAg, and CYFRA21-1 were used as substrates to react with the probes. When the probes reacted with the corresponding marker, the changes in the fluorescence signal were most distinct, with F/F0 higher than other groups, and the difference was statistically significant. Therefore, we concluded that the E1 probe (Fig. 7A) and P10 probe (Fig. 7B) showed specificity.

Fig. 7.

Specificity detection of the probes. a Changes in fluorescence of E1 probe upon reacting with BSA, NSE, proGRP, CEA, SCCAg, and CYFRA 21–1, respectively. @P < 0.05 vs. NSE group. b Changes in fluorescence of P10 probe upon reacting with BSA, NSE, proGRP, CEA, SCCAg, and CYFRA 21–1, respectively. %P < 0.05 vs. ProGRP group. (n = 5)

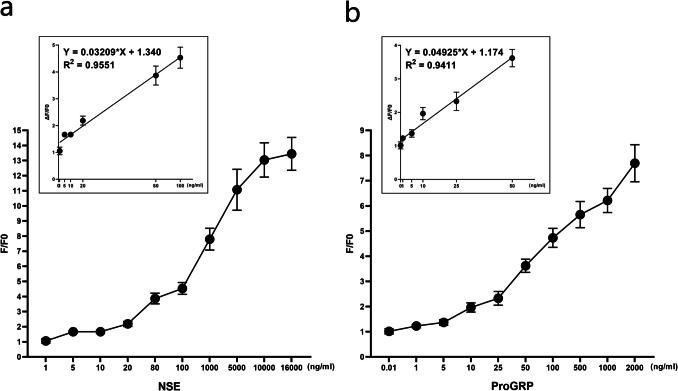

Linearity test for the probes

The quantitative assay kits (Toujing, Shanghai, China) were used to detect the serum tumor markers in the Central Hospital of Dalian University of Technology, and the upper limits of normal concentration for NSE and ProGRP are 16.8 ng/mL and 68.3 pg/mL (Zhang et al. 2021). In the study, the binding reactions were performed with 180 μL of probe solution (4 μg/mL) and 20 μL of marker solution at different concentrations. The E1 probe was reacted with NSE at 1, 5, 10, 20, 80, 100, 1000, 5000, 10,000, and 16,000 ng/mL (Fig. 8A), and the P10 probe was reacted with ProGRP at 0.01, 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 500, 1000, 2000 ng/mL (Fig. 8B). The results showed that the F/F0 value gradually increased as the concentration of protein increased. Referring to the current upper limit of normal concentration, the linear regression curve of E1 probe was fitted with the concentration of 1 to 100 ng/mL, and P10 probe was fitted with the concentration of 1 to 50 ng/mL. As shown in Fig. 8, the R2 values for curve fits were all ˃ 0.9, suggesting the detection ranges of the probes can satisfied the clinical needs.

Fig. 8.

Linearity test for the probes. The reaction system consists of 180 μL/well probe (4 μg/mL) and 20 μL/well serum tumor marker. a Obvious fluorescence change was observed when E1 probe reacted with NSE, and F/F0 increased with the increase of NSE concentration (1–16,000 ng/mL). The linear regression analysis of E1 probe was performed using six increasing concentrations of NSE: 1 ng/mL, 5 ng/mL, 10 ng/mL, 20 ng/mL, 80 ng/mL, and 100 ng/mL. b Obvious fluorescence change was observed when P10 probe reacted with ProGRP, and F/F0 increased with the increase of ProGRP concentration (0.01–2000 ng/mL). The linear regression analysis of P10 probe was performed using six increasing concentrations of ProGRP: 0.01 ng/mL, 1 ng/mL, 5 ng/mL, 10 ng/mL, 25 ng/mL, and 50 ng/mL. (n = 5)

Evaluation of assay performance against patient samples

Patients from the Central Hospital of Dalian University of Technology, with SCLC, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and other occupying diseases, including benign space-occupying pulmonary lesions and tumors in other location, were randomly enrolled in the study. Serum samples were collected after written informed consent, and the results were analyzed according to the upper limits of normal concentration mentioned above. The E1 probe was used to detect serum samples from ten patients, and it was found that the NSE levels in all subjects were lower than the current hospital standard for the upper limit of normal concentration, which is set at 16.8 ng/mL (Fig. 9A). In an effort to enhance the diagnostic accuracy for SCLC, this study proposed recalibrating the upper limit of NSE’s normal concentration to 11.0 ng/mL. With this adjustment, it was observed that the NSE levels in patient with SCLC exceeded this new threshold, while in four out of five patients with NSCLC, the levels were below it, and the levels of the four patients with occupying diseases were below it.

Fig. 9.

Evaluation of assay performance against patient samples. a The E1 probe was used to detect NSE in 1 SCLC patient (red), 5 NSCLC patients (yellow), and 4 patients with other occupying diseases (green). b The P10 probe was used to detect ProGRP in 1 SCLC patient (red), 6 NSCLC patients (yellow), and 3 patients with other occupying diseases (green). The thick dashed lines represented the current upper limit of normal concentration. The thin dashed lines represented the adjusted upper limit of normal concentration for better diagnostic sensitivity and specificity

The P10 probe was used to detect serum samples from the ten patients, and found that the ProGRP levels of all patients were above the current upper limit of the normal concentration used in hospitals, which is 0.068 ng/mL (Fig. 9B). To obtain appropriate diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of SCLC, the study attempted to adjust the upper limit of ProGRP normal concentration to 1.14 ng/mL, so that the ProGRP level of the SCLC patient was above the limit, the ProGRP levels of three out of six NSCLC patients were below the limit, and the ProGRP levels of three patients with other occupying diseases were below the limit.

Discussion

SCLC is recognized as one of the most malignant and lethal subtypes of lung cancer, characterized by an abnormally high value-added rate, a strong tendency for early metastasis, and an overall poor prognosis (Rudin et al. 2021). Therefore, it is necessary to diagnose the disease through a sensitive and rapid method in the early stage to avoid the high incidence rate and mortality caused by late diagnosis. In its early stages, SCLC often presents without noticeable symptoms, necessitating reliance on imaging techniques such as chest X-ray, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (McLoud 2002), as well as invasive examinations such as sputum cytology and bronchoscopy (Tsujimoto et al. 2022) for diagnosis. However, these methods are not without their drawbacks. Imaging techniques, which are phenotype-dependent, have limited resolution for detecting tumors smaller than a millimeter, and invasive sampling is both complex and distressing for patients. In addition, these methods are often time-consuming, labor-intensive, require precise instruments, expensive, and have limited reliability.

The understanding of SCLC at the molecular level has greatly advanced and improved, establishing a clear link between molecular alterations and tissue-level changes during carcinogenesis. This has enabled sensitive and specific biomarker analysis in blood or other body fluids for the early diagnosis of SCLC, thereby reducing the risk of false positives. The use of non-invasive technology for highly specific and sensitive detection of biomarkers associated with SCLC in blood samples offers a painless, simple and straightforward method for early detection. Biomarkers can be categorized into genetic and protein-based markers. While genetic biomarker detection techniques are well-established, it may be limited in its ability to detect post-translational modifications of genes. Protein biomarkers, on the other hand, can discern such modifications and are more sensitive, even in small amounts (Khanmohammadi et al. 2020). Therefore, the detection of protein biomarkers is helpful for the early diagnosis of SCLC, as well as monitoring the response and the potential for recurrence.

SCLC is characterized by its neuroendocrine phenotype, which leads to alternations in the expression of NSE and gastrin releasing peptide (GRP) (Pavel et al. 2020). NSE, a biomarker specific to neurons and peripheral neuroendocrine cells, exhibits increased concentrations in body fluids as SCLC progresses. This elevation renders NSE a highly reliable tumor biomarker for SCLC diagnosis, treatment monitoring, and prognosis evaluation (Mehta et al. 2024). GRP, a mitotic factor expressed in respiratory and neuroendocrine cells, is known for its unstable molecular structure. Consequently, it is recommended to detect its precursor, ProGRP, which is synthesized in an equimolar ratio with the primary peptide (Lyubimova et al. 2022). Studies have confirmed that ProGRP processes high specificity and sensitivity in SCLC patients, making it an effective tumor marker for diagnosing SCLC (Dong et al. 2019; Yu and Wang 2024). However, protein-based tumor biomarkers face limitations compared to nucleic acids, as they cannot be amplified in concentration and are susceptible to significant interference from other proteins. This susceptibility necessitates the use of a large number of samples and is compounded by the drawbacks of current detection methods, which include multiple steps and prolonged time consumption. To address these challenges, this study combined peptides and cpFP to develop a detection method that is rapid, simple, reliable, and cost-effective for both NSE and ProGRP.

Since affinity peptides are short chains composed of less than 50 amino acid residues, they offer several advantages over antibodies or lager proteins, including their small size, easy of synthesis, and amenability to modification (AlDeghaither et al. 2015). Through phage display technology, it is possible to isolate affinity peptides with high selectivity, which are crucial for targeted recognition and therapy (Saw and Song 2019). cpFP probes, encoded by specific genes, has emerged as valuable tools in biosensing and bioimaging due to their lower signal-to-noise ratios and precise spatial resolution (Kostyuk et al. 2019). By cpFP probes being constructed to incorporate affinity peptides as binding domain proteins, the combined strengths of cpFPs and affinity peptides can be leveraged to achieve sensitive, specific, rapid, and cost-effective detection of target proteins.

This study ultimately obtained E1 probe targeting NSE and P10 probe targeting ProGRP. Analysis of patient blood samples revealed that these probes, after adjusting for the upper limit of normal concentration, demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for SCLC diagnosis. Analysis of patient blood samples revealed that these probes, after adjusting the upper limit of normal concentration, demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of SCLC. In addition, cpFP probes can be readily produced through vector amplification and expression, offering a cost-effective solution. The detection process required only a microplate reader, which is user-friendly and provides rapid result interpretation. Owing to these attributes, the E1 and P10 probes show great potential for widespread use in the screening and diagnosis of SCLC. However, the study was constrained by the limited number of SCLC cases, which prevented the acquisition of a substantial sample size, and further discussion is required regarding the upper limits of normal concentration. To obtain the desired diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, it is essential to continue expanding the sample size and types to further define the impacts of complex matrices in biological samples and explore the upper limits of normal concentration. Besides, monitoring during the treatment of SCLC is also crucial. In future research, we will include samples of patients who are already in the treatment stage and clarify the role of probes in efficacy monitoring and recurrence warning of SCLC through long-term follow-up.

Author contribution

BL and BW designed the experiment and checked the manuscript. DX, QJ, and ZL designed the probes, performed the experiment, acquired the data, and drafted the manuscript. AS, JL, and CX analyzed and interpreted the data. SS, HZ, and HY revised the manuscript and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dalian Key R&D Program Project (No.2021YF18SN023) and Dalian Major Basic Research Projects (No. 2023JJ11CG005).

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Dalian University of Technology (No. DUTSBE231018-01).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Dengyue Xu, Hong Yuan, and Zhi Li contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Bin Wu, Email: wubin@ln.ccic.com.

Bo Liu, Email: lbo@dlut.edu.cn.

References

- AlDeghaither D, Smaglo BG, Weiner LM (2015) Beyond peptides and mAbs—current status and future perspectives for biotherapeutics with novel constructs. J Clin Pharmacol 55(Suppl 3):S4-20. 10.1002/jcph.407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Lu S, Guo C, Chen W, Gao Y, Ye D, Guo Z, Ma W (2022) A novel electrochemical immunosensor based on PdAgPt/MoS2 for the ultrasensitive detection of CA 242. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 10:986355. 10.3389/fbioe.2022.986355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- China NHCotPsRo (2022) Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of primary lung cancer. Chin J Ration Drug Use 19(9):1–28. 10.3969/j.issn.2096-3327.2022.09.001

- Dong A, Zhang J, Chen X, Ren X, Zhang X (2019) Diagnostic value of ProGRP for small cell lung cancer in different stages. J Thorac Dis 11:1182–1189. 10.21037/jtd.2019.04.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes Von Borowski R, Gnoatto SCB, Macedo AJ, Gillet R (2018) Promising antibiofilm activity of peptidomimetics. Front Microbiol 9:2157. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyuricza BSJ, Arató V, Szücs D, Vágner a, Szikra D, Fekete A (2021) Synthesis of novel, dual-targeting 68Ga-NODAGA-LacN-E[c(RGDfK)]2 glycopeptide as a PET imaging agent for cancer diagnosis. Pharmaceutics 13(6):796. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13060796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmsma M, Schutte B, Ramaekers FC (2013) Serum markers in small cell lung cancer: opportunities for improvement. Biochim Biophys Acta 1836:255–272. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahandar-Lashaki S, Farajnia S, Faraji-Barhagh A, Hosseini Z, Bakhtiyari N, Rahbarnia L (2025) Phage display as a medium for target therapy based drug discovery, review and update. Mol Biotechnol 67:2161–2184. 10.1007/s12033-024-01195-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Lin Y, Zheng S (2024) Development of the IMP biosensor for rapid and stable analysis of IMP concentrations in fermentation broth. Biotechnol J 19:e2400040. 10.1002/biot.202400040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanmohammadi A, Aghaie A, Vahedi E, Qazvini A, Ghanei M, Afkhami A, Hajian A, Bagheri H (2020) Electrochemical biosensors for the detection of lung cancer biomarkers: a review. Talanta 206:120251. 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.120251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostyuk AI, Demidovich AD, Kotova DA, Belousov VV, Bilan DS (2019) Circularly permuted fluorescent protein-based indicators: history, principles, and classification. Int J Mol Sci 20:4200. 10.3390/ijms20174200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-h, Saxena A, Giaccone G (2023) Advancements in small cell lung cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 93:123–128. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2023.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubimova NV, Kuz’minov AE, Markovich AA, Lebedeva AV, Timofeev YS, Stilidi IS, Kushlinskii NE (2022) Pro-gastrin-releasing peptide as a marker of small cell lung cancer. Bull Exp Biol Med 173:257–260. 10.1007/s10517-022-05529-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoud TC (2002) Imaging techniques for diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. Clin Chest Med 23:123–136. 10.1016/s0272-5231(03)00064-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megyesfalvi Z, Gay CM, Popper H, Pirker R, Ostoros G, Heeke S, Lang C, Hoetzenecker K, Schwendenwein A, Boettiger K, Bunn PA Jr., Renyi-Vamos F, Schelch K, Prosch H, Byers LA, Hirsch FR, Dome B (2023) Clinical insights into small cell lung cancer: tumor heterogeneity, diagnosis, therapy, and future directions. CA Cancer J Clin 73:620–652. 10.3322/caac.21785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta D, Gupta D, Kafle A, Kaur S, Nagaiah TC (2024) Advances and challenges in nanomaterial-based electrochemical immunosensors for small cell lung cancer biomarker neuron-specific enolase. ACS Omega 9:33–51. 10.1021/acsomega.3c06388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavel M, Oberg K, Falconi M, Krenning EP, Sundin A, Perren A, Berruti A, ESMO Guidelines Committee (2020) Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 31:844–860. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premchanth JS, Sadanandan S, Rajamani R (2024) A critical review on the identification of pathogens by employing peptide-based electrochemical biosensors. Crit Rev Chem 1–14:1. 10.1080/10408347.2024.2390551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian X, Meng Q-H, Holdenrieder S, van Rossum H, van den Heuvel M (2024) Circulating lung cancer biomarkers: from translational research to clinical practice. Tumor Biol 46:S27–S33. 10.3233/tub-230012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudin CM, Brambilla E, Faivre-Finn C, Sage J (2021) Small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 7:3. 10.1038/s41572-020-00235-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi R, Endoh T, Yamamoto S, Tainaka K, Sugimoto K, Fujieda N, Kiyonaka S, Mori Y, Morii T (2009) A single circularly permuted GFP sensor for inositol-1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate based on a split PH domain. Bioorg Med Chem 17:7381–7386. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saw PE, Song EW (2019) Phage display screening of therapeutic peptide for cancer targeting and therapy. Protein Cell 10:787–807. 10.1007/s13238-019-0639-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saw PE, Xu X, Kim S, Jon S (2021) Biomedical applications of a novel class of high-affinity peptides. Acc Chem Res 54:3576–3592. 10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CA, Gay CM, Xi Y, Sivajothi S, Sivakamasundari V, Fujimoto J, Bolisetty M, Hartsfield PM, Balasubramaniyan V, Chalishazar MD, Moran C, Kalhor N, Stewart J, Tran H, Swisher SG, Roth JA, Zhang J, de Groot J, Glisson B, Oliver TG, Heymach JV, Wistuba I, Robson P, Wang J, Byers LA (2020) Single-cell analyses reveal increased intratumoral heterogeneity after the onset of therapy resistance in small-cell lung cancer. Nat Cancer 1:423–436. 10.1038/s43018-019-0020-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiltner J, McCandless K, Zahid M (2021) Cell-penetrating peptides: applications in tumor diagnosis and therapeutics. Pharmaceutics 13(6):890. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13060890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto Y, Matsumoto Y, Tanaka M, Imabayashi T, Uchimura K, Tsuchida T (2022) Diagnostic value of bronchoscopy for peripheral metastatic lung tumors. Cancers (Basel) 14:375. 10.3390/cancers14020375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X-J, Cheng J, Zhang L-Y, Zhang J-G (2022) Self-assembling peptides-based nano-cargos for targeted chemotherapy and immunotherapy of tumors: recent developments, challenges, and future perspectives. Drug Deliv 29:1184–1200. 10.1080/10717544.2022.2058647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Wang P (2024) A comparative study of ProGRP and CEA as serological markers in small cell lung cancer treatment. Discov Oncol 15:485. 10.1007/s12672-024-01323-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Xiang B, Lin YP (2021) Predictive value of combined detection tumor markers in the diagnosis of lung cancer. Chin J Prev Med 55:786–791. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20200715-01015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhang X, Gao H, Qing G (2022) Phage display derived peptides for Alzheimer’s disease therapy and diagnosis. Theranostics 12:2041–2062. 10.7150/thno.68636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Ru B, Hu J, Xu L, Wan Q, Liu W, Cai W, Zhu T, Ji Z, Guo R, Zhang L, Li S, Tong X (2023) Recent advances of CREKA peptide-based nanoplatforms in biomedical applications. J Nanobiotechnol 21:77. 10.1186/s12951-023-01827-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Jin J, Hu Q, Zhou H-M, Yi J, Yu Z, Xu L, Wang X, Yang Y, Loscalzo J (2011) Genetically encoded fluorescent sensors for intracellular NADH detection. Cell Metab 14:555–566. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Araki S, Wu J, Teramoto T, Chang YF, Nakano M, Abdelfattah AS, Fujiwara M, Ishihara T, Nagai T, Campbell RE (2011) An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca(2+) indicators. Science 333:1888–1891. 10.1126/science.1208592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.