Abstract

De novo assembly of ancient metagenomic datasets is a challenging task. Ultra-short fragment size and characteristic postmortem damage patterns of sequenced ancient DNA molecules leave current tools ill-equipped for ideal assembly. We present CarpeDeam, a novel damage-aware de novo assembler designed specifically for ancient metagenomic samples. Utilizing maximum-likelihood frameworks that integrate sample-specific damage patterns, CarpeDeam demonstrates improved recovery of longer continuous sequences and protein sequences in many simulated and empirical datasets compared to existing assemblers. As a pioneering ancient metagenome assembler, CarpeDeam opens the door for new opportunities in functional and taxonomic analyses of ancient microbial communities.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13059-025-03839-5.

Keywords: Ancient DNA, Metagenomics, De novo assembly, Microbes, Proteins

Background

DNA recovered from ancient organisms, termed ancient DNA (aDNA), has transformed evolutionary science. Besides the exploration of ancestral human populations, aDNA enables the reconstruction of past environments covering eukaryotic species diversity and microbial community dynamics [1–4]. However, the computational analysis of aDNA is challenging [5, 6]. Two primary processes lead to the breakdown and chemical alteration of aDNA. Hydrolytic mechanisms cause the degradation of DNA molecules and deamination converts cytosines into uracil molecules. These are misinterpreted as putative base substitutions during DNA sequencing [7]. This phenomenon, known as “damage,” occurs predominantly at the ends of aDNA fragments, and the rate of occurrence of damage at each fragment position can be quantified [8–11]. As a result, aDNA fragments show elevated frequencies of CT substitutions at the 5 end and GA substitutions at the 3 end, respectively [12]. Along with the short fragment size, damage profiles are commonly used for aDNA authentication [13–16]. However, the ambiguity introduced by deaminated bases hampers downstream analysis such as read mapping or genome assembly [17–19].

Metagenomes represent the collective genetic material from various species within a sample, derived from environments such as the human gut or soil, including bacteria, archaea, viruses, and eukaryotes [20, 21]. The field has expanded with the advent of massive parallel sequencing, leading to a deeper understanding of microbial diversity and functional profiling on Earth [22–24]. However, analyzing metagenomic datasets relies on dedicated tools as the data is inherently complex due to high species diversity and varying abundance profiles, and the choice of tools depends on the specific research goals [25]. There are two main approaches that follow different objectives when analyzing metagenomic data: taxonomic classification and functional annotation [26].

Taxonomic classification categorizes genomic sequences to determine microbial composition, thus offering an overview of the taxonomic diversity [27]. Numerous tools have been developed, utilizing both read-based and assembly-based approaches. Read-based methods employ various strategies such as marker gene analysis, database alignment, or k-mer-based techniques [27–30]. Assembly-based methods, which work with either assembled contigs or long reads, potentially increase classification accuracy. These approaches rely on tailored data structures or alignment techniques to efficiently process large numbers of sequences [31–34]. Notably, taxonomic classification has been widely applied to ancient metagenomes [3, 35–39], with specialized tools developed to address the unique challenges posed by degraded, short aDNA fragments [40, 41].

While functional annotation of sequences can be achieved by mapping reads to protein databases, assembly-based methods often provide more accurate and comprehensive results, particularly in metagenomic studies with many unknown or distantly related species [42]. De novo assembly is commonly used to uncover a wide range of elements, from protein-coding genes to entire genomes. This approach is especially advantageous for ancient samples, where modern references may fail to capture distantly related species. Moreover, short fragment lengths and characteristic aDNA damage patterns further complicate alignment-based methods [43].

Several studies have demonstrated the applicability of de novo assembly for searching aDNA samples for antibiotic-resistance genes or unknown metabolites, or for reconstructing whole genomes [17, 44–49]. For instance, a study by Wan et al. [50] recently demonstrated the potential of mining proteomes from extinct species, termed the “extinctome,” to identify novel antimicrobial genes. Considering that approximately 90% of prokaryotic genomes are protein-coding [51–53], de novo assembly of extinct species is the gateway for revealing unknown proteomes. While Klapper et al. [17] highlighted the fact that deeply sequenced datasets can be assembled using conventional assembly algorithms, the assembly process becomes more challenging when dealing with samples that exhibit high damage rates and low coverage.

To demonstrate the effects of varying fragment length and damage patterns, we simulated fragments of a simple metagenomic environment with different fragment sizes and deamination rates. As shown in Fig. 1A, fragment length and damage drastically influence the outcome of ancient metagenome assembly. The damage patterns used for the simulations (Fig. 1B) represent two levels of damage intensities as they can be found in studies profiling ancient microorganisms. Even at moderate damage levels with the first position of the 5 end exhibiting a damage rate of ~35%, we observed a significant drop in assembly performance. Several studies have documented rates of nucleotide misincorporation at the 5 end, ranging from 15% to 60% [3, 17, 36, 54–57]. Our findings highlight the need for optimized assembly algorithms to address the unique characteristics of ancient metagenomic datasets.

Fig. 1.

A Impact of aDNA damage and fragment length on metagenomic assembly. The plots show the sum of all contigs larger than 500 bp after assembling a simulated toy dataset with either MEGAHIT [58] or metaSPAdes [59]. Each bar plot refers to a different combination of fragment length and damage rate of the simulated data. While empirical data is inherently more complex in terms of variation in fragment lengths and damage patterns, our simplified dataset demonstrates how common assemblers are limited by aDNA damage. B Damage patterns used for the simulation of aDNA fragments. We used two levels of deamination rates for the simulations: moderate damage and mild damage compared to the rates found in ancient microbial studies [3, 17, 36, 54–57]. The blue traces represent C-to-T substitution rates, while the red traces indicate G-to-A substitution rates

There are two major classes of de novo assembly algorithms: Overlap Layout Consensus (OLC) and de Bruijn graphs. OLC algorithms rely on the computation of full read overlaps, while de Bruijn graph algorithms construct contigs using sub-sequences of length k (k-mers) [60]. Although OLC algorithms are precise, they are computationally impractical for assembling large datasets produced by high-throughput sequencing technologies [61, 62]. Consequently, de Bruijn graph algorithms have become the prevalent algorithmic basis for most assemblers developed in the past decade. De Bruijn graph assemblers connect k-mers that overlap by at least k−1 nucleotides in a graph structure, thereby efficiently assembling short reads into contigs [58, 63, 64]. However, de Bruijn graph assemblers face a precision-sensitivity trade-off when assembling complex metagenomic data. Longer k-mers provide higher specificity for individual species but suffer from reduced sensitivity in populations with high intra-species diversity. Conversely, shorter k-mers offer increased sensitivity but lack the specificity required to effectively distinguish between closely related species [62, 65]. Moreover, as k-mer length increases, sequencing errors are more likely to interfere with matching k-mers correctly, making read correction methods necessary to address this issue. Ancient metagenomic datasets, characterized by damaged and short fragments, amplify this issue by naturally increasing diversity and complexity and thereby stretching the limits of de Bruijn graph assemblers [6]. New assembly strategies are needed to overcome these issues.

The de novo metagenomic assembler PenguiN [62] uses a greedy-iterative overlap-based assembly method. Inspired by the protein level assembler PLASS [65], it clusters reads based on shared k-mers. Extension candidates are then selected from these clusters using a Bayesian model that leverages alignment length and sequence identity between the query and extension candidate in both protein and nucleotide space. The extension process continues iteratively, first clustering, then extending. Clustering reduces the computational complexity of finding overlaps from quadratic in the number of reads to quasi-linear. This overlap-centric approach avoids the precision-sensitivity trade-off seen for de Bruijn graph assemblers, resulting in improved recovery from highly diverse metagenomic datasets [62, 65].

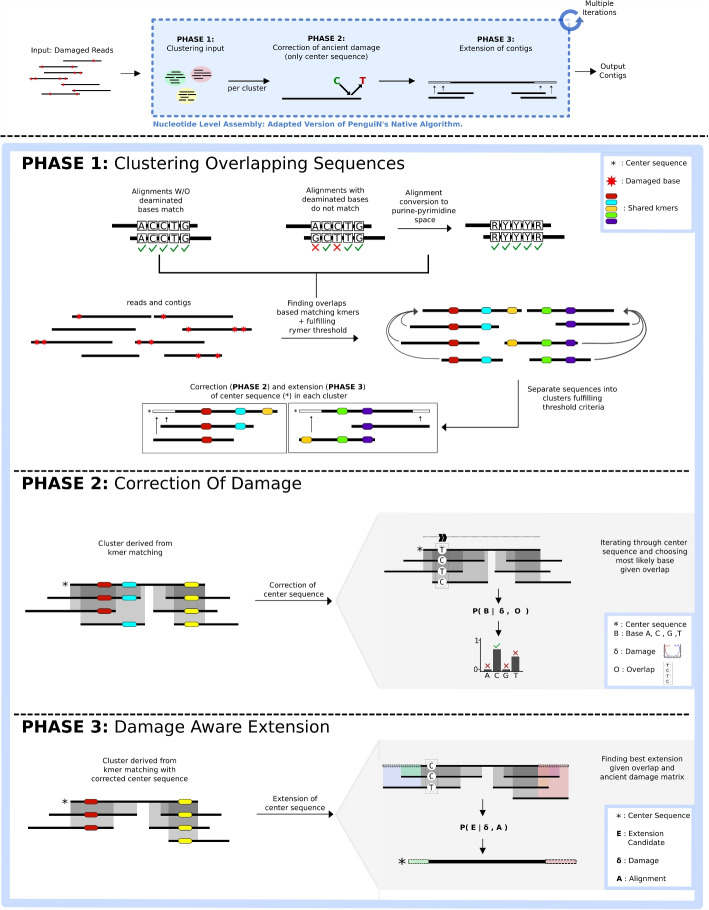

Here we introduce CarpeDeam, a de novo assembler specifically designed for ancient metagenomic data, based upon the greedy-iterative workflow of PenguiN [62]. It addresses the aforementioned challenge of high damage levels. Each iteration comprises three phases: First, sequences are clustered based on shared k-mers analogs to PenguiN. CarpeDeam additionally refines clusters by using a filter that employs a purine-pyrimidine encoding [66]. This encoding, which we refer to as RYmer space, ensures that cluster assignments of sequences are robust to aDNA damage events. In the second phase, sequences with base substitutions that are likely to be due to damage in the aDNA fragments are corrected. The final phase involves the elongation of contigs through an extension rule that takes into account aDNA-specific substitution patterns.

We introduce CarpeDeam, a novel assembler specifically designed for ancient metagenomic datasets. Our analysis highlights the challenges assemblers face when dealing with aDNA datasets, as performance varies greatly depending on fragment length distributions and damage patterns. CarpeDeam demonstrates superior performance in simulated datasets and in many empirical datasets, recovering unique genomic segments that are missed by other assemblers. CarpeDeam offers two modes: a default “safe” mode for reducing errors and an “unsafe” mode for increased sensitivity. These promising results mark an important step forward in damage-specific assembly; however, further advancements will be needed to fully address the complexities of ancient metagenomic datasets.

Results

Workflow of CarpeDeam

CarpeDeam is an assembler based on the metagenome assembler PenguiN. It employs a similar greedy, iterative overlap strategy, yet it incorporates several critical adjustments tailored for assembling ancient metagenomic data. Whereas PenguiN utilizes six-frame translated reads to find overlaps in amino acid space, we omit this step as ancient DNA fragments are ultrashort, resulting in even shorter amino acid sequences. In the text, we use the term aDNA fragments to describe the trimmed and merged sequencing reads (see discussion in Lien et al. [67]).

Overall CarpeDeam relies on three iteratively repeated steps: During PHASE 1 (see Fig. 2), sequences are clustered based on shared k-mers via the MMseqs2 linclust algorithm [68]. In this process, each sequence within a cluster is required to align to the center sequence with a minimum sequence identity. The center sequence is defined as the longest sequence within the cluster and becomes the focus for subsequent correction or extension processes, depending on the stage. The remaining sequences in the cluster, termed member sequences, overlap with the center sequence and contribute to its damage correction. In the extension phases, they serve as extension candidates. While PenguiN applies a relatively high default sequence identity threshold (99%), the presence of deaminations in aDNA requires a reduction in this threshold as the sequence identity is naturally lower even for sequences of the same provenance. CarpeDeam filters clusters using a reduced sequence identity threshold of 90% while introducing the concept of RYmer sequence identity, which converts sequences to a reduced nucleotide alphabet of purines (adenine and guanine) and pyrimidines (cytosine and thymine) to account for deaminated bases. First, the clusters are generated with all member sequences sharing at least one k-mer with the center sequence and the sequence similarity of the full overlap is computed following PenguiN’s workflow. Additionally, we compute the sequence similarity in RYmer space, where an A or a G is encoded as R (one letter encoding for purine) and a C or T as Y (one letter encoding for pyrimidine), of the full overlap. For a detailed explanation of this concept, please refer to Section S7 in Additional file 1. Overall, the RYmer space sequence identity allows for mismatches due to deamination events.

Fig. 2.

CarpeDeam’s main workflow: The input are aDNA sequences (FASTQ format) which have been trimmed and, for paired-end data, merged. During an iterative process, the fragments are corrected and extended to long contigs. In PHASE 1, the fragments are grouped into clusters sharing at least one k-mer as well as an overlap sequence identity of 99% in RYmer space. PHASE 2 corrects deaminated bases. In particular, the center sequence of each cluster (which is always the longest sequence) is assigned the most likely base per position given the evidence of overlapping sequences in the cluster and the user-provided damage patterns. In PHASE 3, the center sequence of each cluster is extended by the candidate sequence from the cluster that is most likely to be the correct extension. In fact, PHASE 3 is divided into two steps. First, only aDNA fragments (non-extended sequences) are taken into account for extension, as the provided damage patterns are only valid for non-extended sequences. In the second step of PHASE 3 exclusively contigs (sequences that already have been extended at least once) are used for the extension, applying a modified Bayesian extension model from the native PenguiN assembler

In PHASE 2 (see Fig. 2), CarpeDeam corrects deaminated bases. Any base in the center sequence of a cluster that is covered by at least one other sequence from the cluster can be corrected. Employing the user-provided damage patterns, the method utilizes a maximum-likelihood estimation to infer the most probable base for each position. The likelihood model is explained in more detail in the Methods section.

During PHASE 3 (refer to Fig. 2), sequences are extended. PenguiN employs an extension rule based on a Bayesian model, which selects the most suitable extension for each cluster. In contrast, we split the extension process into two distinct phases. The initial phase exclusively targets non-extended sequences (i.e. aDNA fragments). The key aspect is that the damage pattern provided by the user is only valid for these sequences, enabling the application of our likelihood model. Consequently, the initial phase focuses on extending the center sequence using yet non-extended sequences. Within each iteration, the extension continues as long as our likelihood model supports a strong belief in the accuracy of the extension (see the “Methods” section). The subsequent phase involves merging contigs: sequences that have already been extended and corrected. For this, CarpeDeam applies PenguiN’s Bayesian model with adjustments to improve its applicability to ancient datasets (see the “Methods” section).

We assessed the performance of CarpeDeam by generating 81 simulated datasets derived from three distinct ancient environments: gut microbiome [44], dental calculus [35], and bone material [69]. For each environment, 27 datasets were created, varying in coverage, damage, and fragment length distribution. Furthermore, we assembled and evaluated 20 empirical datasets, performing taxonomic classification and protein similarity search on the contigs as evaluation criteria (see the “Methods” section for further details).

According to our findings, MEGAHIT [58] and metaSPAdes [59] are the metagenomic assemblers of choice and have been applied in published studies for de novo assembly of ancient metagenomic datasets [17, 44–49]. To evaluate CarpeDeam’s efficacy, we conducted an extensive benchmark comparison against the state-of-the-art assemblers MEGAHIT and metaSPAdes as well as the novel assembler PenguiN [62].

Overall, during our analysis we found that CarpeDeam can produce an elevated number of misassemblies. To offer users more flexibility in managing this trade-off, we introduced two operational modes for CarpeDeam: safe and unsafe. The safe mode (set as default) additionally implements a consensus-calling approach during the extension phase to reduce misassemblies. Users can opt for the unsafe mode, which disables only the consensus calling mechanism, potentially increasing sensitivity at the cost of a higher rate of chimeric contigs. This dual-mode approach allows users to balance between assembly sensitivity and accuracy based on their specific research needs and dataset characteristics.

Simulated data

Evaluation strategy of assembly quality with metaQUAST and Prokka

We simulated 81 datasets of metagenomic paired-end Illumina short reads of three different environments by varying three parameters: average coverage depth (3×, 5×, and 10×), fragment length distributions (medium, short, and ultra-short), and DNA damage patterns (moderate, high, and ultra-high). The taxonomic profiles of our simulated datasets were derived from three publications [35, 44, 69], representing varying levels of complexity in species diversity. For instance, the most complex dataset mirrors a gut microbiome consisting of 116 identified microbial species derived from Wibowo et al. [44], with individual species abundances ranging from a maximum of 10.77% to a minimum of 0.011%. At 10× average coverage, this results in the least abundant species having a coverage of only 0.15×. While all species had the same simulated rate of damage and fragmentation patterns, we also created non-uniform simulations where different species have different rates of damage and fragmentation patterns (see Additional file 1, Section S4 [70]).

We assembled the simulated datasets with CarpeDeam, PenguiN [62], MEGAHIT [58], and metaSPAdes [59].

All assemblers were run with their default parameters, except for the minimum contig length, which was set to a minimum of 500 bp. For CarpeDeam we ran both the safe and the unsafe mode. We specified the flag –only-assembler for metaSPAdes because we observed the program getting stuck in the step that aims to correct sequencing errors. Skipping this step was advised in the issues section of the metaSPAdes GitHub repository (issue 306).

The reference genomes underlying our simulations were used to evaluate the assemblies of all four assemblers. We used the original references to compute the following alignment-based metrics: NA50, LA50, largest alignment, duplication ratio, misassemblies, and mismatches per 100 kb as generated by metaQUAST [71]. We set the sequence identity threshold at 90% for the metaQUAST [71] alignments as suggested in the metaQUAST documentation. Additionally, we mapped the aDNA fragments back to the contigs using Bowtie2 [72] with –very-sensitive-local and reported the fraction of mapped fragments against the contigs via SAMtools [73].

Comparison of assemblers based on standard metrics reported by metaQUAST

For our benchmark, we set the minimum contig length to 500 bp. Figure 3 presents four key metrics – largest alignment, number of misassemblies per contig, covered genome fraction, and NA50 – for nine selected datasets: moderate damage and short fragment length at coverage depths of 3×, 5×, and 10×. Results for all 81 datasets are provided in Section S2 in the Additional file 1.

Fig. 3.

Performance evaluation of assemblers CarpeDeam (safe and unsafe modes), MEGAHIT, metaSPAdes, and PenguiN across nine simulated datasets. Results are presented for datasets with category moderate damage and short fragment length distribution, simulated for three environments (gut, dental calculus, and bone) and three coverage levels (3×, 5×, and 10×). The metrics shown are largest alignment (row 1), misassemblies per contig (row 2), genome fraction (row 3), and NA50 (row 4). Each bar represents the performance of an assembler for a specific metric, coverage, and environment

CarpeDeam, in both its safe and unsafe modes, and MEGAHIT demonstrated strong performance across the presented assembly metrics. In contrast, PenguiN and metaSPAdes were less effective at assembling comparable fractions of the metagenomes.

A notable difference was observed in the “largest alignment” metric (Fig. 3, row 1), where CarpeDeam’s unsafe mode consistently produced substantially longer contigs compared to other assemblers. This advantage was particularly evident in the calculus and gut datasets. For most datasets, even CarpeDeam’s safe mode yielded larger maximum alignments than MEGAHIT, while not achieving ultra-long alignments as the unsafe mode did. Only for the 3× gut dataset, MEGAHIT had a larger alignment than both CarpeDeam modes. PenguiN and metaSPAdes both had significantly shorter maximum alignments.

As expected, the increased sensitivity of CarpeDeam’s unsafe mode came at the cost of a higher misassembly rate, as shown by the “misassemblies per contig” metric (Fig. 3, row 2). For the 3× gut dataset, CarpeDeam’s unsafe mode generated more than twice as many misassemblies per contig than MEGAHIT; for the 5× gut dataset, four times as many per contig than MEGAHIT; and for the 10× gut datasets, six times as many per contig than MEGAHIT.

Although CarpeDeam’s safe mode exhibited an elevated misassembly rate compared to MEGAHIT, PenguiN, and metaSPAdes, the difference was less pronounced. The most notable difference was observed in the 10× gut datasets, where the safe mode created about 2.5 times as many misassemblies per contig as MEGAHIT.

The fraction of recovered genomic content is shown in row 3 of Fig. 3 and CarpeDeam (both modes) score the highest in this category. Although the genome fraction recovered by MEGAHIT varied across datasets, it generally fell between the values obtained by CarpeDeam’s safe and unsafe modes. For the gut dataset, the values of the recovered genomic fractions were for CarpeDeam’s safe mode, for CarpeDeam’s unsafe mode, and for MEGAHIT (in that order): 2.1%, 2.9%, and 3.0% for the 3× dataset; 4.7%, 6.2%, and 5.8% for the 5× dataset; and 10.4%, 12.8%, and 9.2% for the 10× dataset. Both metaSPAdes and PenguiN recovered a substantially lower genome fraction.

Finally, the NA50 metric is presented in Fig. 3, row 4. Generally, the N50 metric represents the length of the shortest contig such that half of the total assembled length is contained in contigs of this length or longer. While N50 is a commonly used metric to get a first impression of assembly quality, it does not distinguish between contigs that align with a reference genome and those that do not. The NA50 metric on the other hand considers only those contigs that have aligned to a reference genome. This adjustment helps to mitigate the influence of long chimeric or misassembled contigs that might artificially inflate the N50 value.

The top three performers in terms of NA50 values are CarpeDeam (in both safe and unsafe modes) and MEGAHIT. It is worth noting that CarpeDeam’s unsafe mode sometimes exhibits significantly higher NA50 values for certain datasets.

Table 1 presents additional metrics reported by metaQUAST [71] for evaluating the gut datasets with moderate damage and short fragment length distribution, representing the most complex of the three samples. Additional results for the dental calculus and bone datasets, which are progressively less complex, as well as other parameter combinations of fragment length distributions and damage patterns, are provided in the Additional file 1, section S2.

Table 1.

Assembly evaluation metrics for the simulated gut metagenomic environment with moderate damage and short fragment length distribution

| Assembler | Cov. | Genome fraction (%) | Largest alignment | Reads mapped fraction | NA50 | LA50 | Misassemblies per contig | # Mismatches per 100 kb | Duplication ratio | Total length (bp) | Total Len.1000 bp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarpeDeam (safe mode) | 3× | 2.101 | 6223 | 0.227 | 801 | 4004 | 0.011 | 395.290 | 1.095 | 9,796,467 | 3,402,822 |

| CarpeDeam (safe mode) | 5× | 4.658 | 12,431 | 0.395 | 905 | 7270 | 0.013 | 389.740 | 1.132 | 22,446,367 | 10,049,155 |

| CarpeDeam (safe mode) | 10× | 10.390 | 37,369 | 0.627 | 1163 | 12,068 | 0.017 | 399.340 | 1.202 | 53,148,016 | 30,956,547 |

| CarpeDeam (unsafe mode) | 3× | 2.919 | 13,325 | 0.314 | 1043 | 3799 | 0.022 | 512.640 | 1.116 | 13,875,108 | 7,349,327 |

| CarpeDeam (unsafe mode) | 5× | 6.188 | 42,402 | 0.508 | 1302 | 5061 | 0.029 | 504.740 | 1.180 | 31,087,499 | 18,945,119 |

| CarpeDeam (unsafe mode) | 10× | 12.763 | 136,564 | 0.762 | 2464 | 5468 | 0.052 | 518.150 | 1.395 | 75,781,097 | 58,813,418 |

| MEGAHIT | 3× | 3.025 | 13,419 | 0.246 | 934 | 4037 | 0.009 | 158.760 | 1.008 | 12,938,041 | 5,982,557 |

| MEGAHIT | 5× | 5.757 | 8461 | 0.317 | 903 | 8831 | 0.010 | 160.800 | 1.008 | 24,629,258 | 10,713,343 |

| MEGAHIT | 10× | 9.168 | 12,385 | 0.313 | 966 | 12,524 | 0.008 | 153.460 | 1.009 | 39,242,566 | 18,863,238 |

| metaSPAdes | 3× | 0.110 | 981 | 0.007 | 554 | 373 | 0.016 | 481.170 | 1.001 | 469,988 | 0 |

| metaSPAdes | 5× | 0.211 | 1806 | 0.015 | 574 | 645 | 0.006 | 377.930 | 1.003 | 902,081 | 38,373 |

| metaSPAdes | 10× | 0.592 | 4064 | 0.049 | 629 | 1463 | 0.002 | 328.500 | 1.012 | 2,550,384 | 417,629 |

| PenguiN | 3× | 0.021 | 838 | 0.002 | 549 | 78 | 0.018 | 979.500 | 1.045 | 93,626 | 0 |

| PenguiN | 5× | 0.049 | 886 | 0.005 | 563 | 172 | 0.000 | 1037.790 | 1.054 | 218,456 | 0 |

| PenguiN | 10× | 0.151 | 1038 | 0.014 | 555 | 577 | 0.006 | 1182.980 | 1.122 | 721,791 | 1043 |

The table shown also includes the fraction of aDNA fragments mapped against the assembly. Across all three datasets, CarpeDeam’s unsafe mode consistently demonstrated a higher number of aDNA fragments mapping to its contigs than other assemblers. Notably, MEGAHIT performed very well for the 3× coverage gut dataset, with the highest values for both the “Genome fraction” and “Largest alignment” metrics.

The metric “mismatches per 100kb” is also presented in Table 1. MEGAHIT consistently exhibited the lowest number of mismatches per 100 kb across all coverage levels. Interestingly, PenguiN displayed the highest mismatch values, exceeding 1000 mismatches per 100 kb for all three coverages (3×, 5×, and 10×). This observation aligns with the fact that PenguiN does not perform base correction, as it was designed for modern viral metagenomes. In contrast, the de Bruijn graph assemblers MEGAHIT and metaSPAdes employ bubble merging algorithms to resolve bases in cases where multiple possibilities exist.

Despite CarpeDeam recovering significantly more than PenguiN, the higher mismatch rate per 100 kb in CarpeDeam is indicative of its damage correction process, which is based on PenguiN. CarpeDeam’s safe mode shows a lower mismatch rate per 100 kb than its unsafe mode, yet is higher than MEGAHIT. For instance, for the 5× gut dataset in Table 1, the mismatch rates are 449 mm.p 100kb (CarpeDeam safe), 613 mm.p 100kb (CarpeDeam unsafe), 159 mm.p 100kb (MEGAHIT), 1147 mm.p 100kb (PenguiN), and 379 mm.p.100kb (metaSPAdes). As indicated in Table 1, CarpeDeam exhibits a higher duplication rate. This impacts the mismatch rate per 100 kbp because the number of mismatches computed by metaQUAST is proportional to the duplication ratio. Consequently, mismatch rates can be elevated when there are numerous overlapping alignments, as each assembly alignment is analyzed independently. Additionally, the higher misassembly rate contributes to the mismatch rate. For instance, a misassembled contig aligning to the reference can accumulate mismatches at the ends of the aligned region due to chimeric nature of the contig. Since metaQUAST tolerates a certain degree of sequence divergence, these mismatches are included in the calculation, further elevating the mismatch rate.

The tables reveal a general trend where CarpeDeam demonstrates higher sensitivity, producing a larger number of contigs. This is indicated by its elevated duplication ratio and higher mapped fraction, while achieving a genome fraction similar to MEGAHIT. Our observations align with the findings presented in the PenguiN [62] manuscript: PenguiN’s approach recovers more strain-resolved viral genomes, while generally exhibiting a higher duplication rate. In contrast, MEGAHIT appears to prioritize precision, generating fewer contigs with a lower rate of misassemblies, resulting in capturing less of the genomic diversity present in the sample.

We show NA50 and LA50 in Table 1 as they can be viewed as more informative as their “non-aligned” counterparts N50 and L50. A higher NA50 is considered better as it describes the minimum alignment length to be considered, covering half of the alignment length of all contigs. For LA50, however, a lower value is considered better, as it describes the number of aligned blocks that need to be considered to cover half of the alignment length of all contigs. It must be noted that these metrics need to be evaluated in the context of the covered genome fraction. For instance, while PenguiN and metaSPAdes both have small LA50 values, the tools recovered a much smaller genome fraction than CarpeDeam and MEGAHIT.

Impact of fragment length distributions and damage levels on assembly performance

Our simulation of three different samples, with varying coverages, fragment lengths, and damage profiles, resulted in a total of 81 datasets. The results of these assemblies are presented in the Additional file 1, Section S2, as extended heatmaps for various metrics reported by metaQUAST [71].

There were several key observations. Fragment length distributions had a notable impact on the assembly performance. The distributions are shown in the Additional file 1, Fig. S1 (A). Assemblies derived from the medium fragment length distribution (median 58 bp) generally outperformed those from the short (median 47 bp) and ultra-short (median 42 bp) distribution (Additional file 1, Figs. S2–S13). Interestingly, datasets with ultra-short fragments often recovered a slightly higher genome fraction than those with short fragments, despite the latter distribution having a longer median fragment length. This trend is particularly evident for assemblers such as CarpeDeam, PenguiN, and metaSPAdes, while it is less pronounced for MEGAHIT. The distributions differ in their maximum fragment lengths, with the ultra-short distribution reaching up to 140 bp and the short distribution reaching only 120 bp. These rare longer fragments likely have a disproportionate influence on assembly performance.

Damage profiles also played a critical role in assembly outcomes. Counterintuitively, the parameter combination of ultra-high damage and medium fragment lengths yielded the highest genome fractions in many cases. This contrasts with the moderate damage datasets, which consistently performed worse. A closer examination of the damage profiles revealed that the slope of the substitution rates across positions is a significant factor. While moderate damage had the lowest substitution rate at position 1 of the simulated fragments, it maintained relatively high rates at position 5, suggesting that a steeper decline in substitution rates positively influences assembly performance.

Evaluation of non-misassembled contigs across assemblers

To further evaluate the quality of assemblies beyond the genome fraction metric, we assessed the ability of each assembler to reconstruct long, non-misassembled contigs as classified by metaQUAST. While genome fraction provides valuable information, it does not account for the length of individual contigs mapping back to the reference genome (by default metaQUAST considers all alignments over 65 bp). Consequently, a high number of short contigs may inflate the genome fraction without necessarily representing superior assembly quality. To address this limitation, we analyzed the number of non-misassembled contigs exceeding 2000 bp for each assembler across the datasets with short fragment length and moderate damage.

We demonstrate CarpeDeam’s capacity to generate longer accurate contigs across datasets, shown in the Additional file 1, Fig. S18. CarpeDeam (unsafe mode) consistently produced more long contigs for all datasets except one (3× coverage bone dataset, where MEGAHIT outperformed both CarpeDeam modes). CarpeDeam’s safe mode and MEGAHIT exhibited alternating performance, with CarpeDeam producing more longer non-misassembled contigs in four cases and MEGAHIT in four cases. Notably, PenguiN and metaSPAdes generated significantly fewer long contigs compared to other assemblers. Although CarpeDeam produced a higher number of misassemblies, which would require careful filtering in downstream analyses, the increased quantity of non-misassembled contigs over 2000 bp suggests a notable improvement in assembly contiguity.

Comparison of non-coding genomic content across assemblers

To complement our metaQUAST alignment analysis, we performed an additional examination of the assembly fractions (Fig. 4). We used skani [74], a tool for calculating average nucleotide identity (ANI) and aligned fraction (AF), employing an approximate mapping method without base-level alignment. Contigs shorter than 1000 bp were excluded to focus on long genomic segments.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of mapped fractions of base pairs, genomic features, and RNA recovery across different assemblers and coverage levels for the gut dataset. A Distribution of mapping categories (mapped non-duplicated, mapped duplicated variant, mapped duplicated redundant representative, mapped duplicated redundant, unmapped non-duplicated, and unmapped duplicated base pairs) for assemblies of the gut dataset at 10×, 5×, and 3× coverage levels. B Types of genomic features recovered in contigs based on Prokka annotations, for different assemblers (gut dataset). C Recovery of rRNAs and tRNAs with sequence identities above and below 98% for MEGAHIT and CarpeDeam (safe and unsafe modes) across different coverage levels (gut dataset; moderate damage, short fragment length distribution)

We categorized the mapping results into groups to provide a detailed evaluation of the assembly quality and its ability to handle redundancy and variation. The category unmapped_nondup_bp includes non-redundant nucleotides in the assemblies that do not map to the reference with an average nucleotide identity (ANI) of over 99%. These sequences represent unique content that was not successfully aligned to the reference. In contrast, unmapped_dup_bp comprises nucleotides in the assemblies that also do not map to the reference but include redundant sequences, reflecting over-represented regions introduced by the assembler.

For mapped base pairs, mapped_dup_var_bp consists of duplicates that are highly similar to reference sequences (ANI > 99%) but show minor variations, such as mutations present in some species but absent in others. This category highlights the assembly’s ability to capture genetic diversity. Meanwhile, mapped_dup_red_bp represents redundant mapped base pairs that are likely a result of assembling more than one contig for the same genomic region, indicating redundancy in the assembly process.

The category mapped_dup_red_rep_bp quantifies the subset of redundant mapped base pairs required to create a representative set. By comparing this to mapped_dup_red_bp, one can infer metrics similar to the “duplication ratio” reported by metaQUAST, highlighting how redundant base pairs captured by mapped_dup_red_bp are distributed. This subset, defined by mapped_dup_red_rep_bp, represents the unique base pairs within the redundant regions.

Finally, mapped_nondup_bp captures the non-redundant mapped base pairs, excluding the duplicates. This category indicates how much of the reference is covered by base pairs that map with high ANI and are unique, making them especially valuable for downstream analyses.

Overall, we conducted this mapping strategy to provide a more detailed evaluation of the nucleotide fractions in the assembled contigs that can be mapped to the reference. Unlike metaQUAST’s Genome Fraction metric, which applies a minimum alignment length and a fixed sequence similarity threshold, skani offers a more flexible approach to assessing mappings.

Our six categories capture detailed differences in the assemblies, including their ability to manage redundancy, capture genetic variation (e.g., within highly similar genetic regions), and evaluate completeness in terms of reference coverage. These results help users evaluate CarpeDeams’ suitability for their specific research needs. For instance, while higher redundancy may complicate downstream analyses like binning, it poses less of a concern when focusing on specific gene regions, where sensitivity is of greater interest.

Figure 4, panel A, presents the results for the gut dataset across 10×, 5×, and 3× coverage levels. Our analysis revealed that CarpeDeam (unsafe mode) exhibited the highest mapped_non_dup_bp fraction, particularly in the 10× coverage dataset. This advantage decreased at lower coverages (5× and 3×), with the difference between CarpeDeam and MEGAHIT diminishing. Substantial fractions of unmapped_non_dup_bp sequences were observed across assemblies, most notably in CarpeDeam (safe and unsafe) and MEGAHIT. PenguiN and metaSPAdes showed significantly lower fractions across all mapping categories compared to other assemblers.

We further investigated the types of genomic features other than coding regions recovered by different assemblers (Fig. 4, panel B). For this analysis, we used Prokka’s annotation output. Our results showed that CarpeDeam demonstrated a strong ability to recover rRNA, tRNA and repeat region segments while MEGAHIT assembled significantly less base pairs that could be classified by Prokka. It should be noted that only the results for MEGAHIT and CarpeDeam (safe and unsafe) are presented here, as other assemblers recovered substantially less genomic content overall, making their inclusion in the plot impractical for comparative purposes. The results refer to the gut dataset with moderate damage and the short fragment length distribution.

Figure 4, panel C, illustrates the recovery of rRNAs and tRNAs with sequence identities above and below 98%. For tRNAs in the 3× gut dataset, CarpeDeam (safe mode) and MEGAHIT reconstructed comparable numbers of high-identity (ge98%) sequences, while CarpeDeam (unsafe) outperformed both, reconstructing more than three times as many. This difference became more pronounced in the 5× and 10× datasets, where both CarpeDeam modes assembled significantly more high-identity tRNAs than MEGAHIT. For rRNA reconstruction, we could observe a distinct pattern: MEGAHIT recovered very few, whereas both CarpeDeam modes recovered several rRNAs. For instance, for the 10× gut dataset, CarpeDeam’s unsafe mode could recover more than 200 rRNAs of which more than 100 had a sequence identity of 98%. Notably, CarpeDeam (safe mode) recovered fewer rRNAs overall, but those recovered predominantly exhibited 98% sequence identity. Conversely, CarpeDeam (unsafe mode) recovered a larger quantity of rRNA, albeit with a considerable fraction (< 50%) showing < 98% sequence identity. Interestingly, some RNA sequences annotated by Prokka in the assemblies failed to match the reference annotation. While CarpeDeam (safe) and MEGAHIT exhibited similarly low rates of these “no hit” instances, CarpeDeam (unsafe) demonstrated the highest occurrence of unmatched annotations.

Evaluation of recovered protein content in assembled contigs

Effectively reconstructing protein-coding sequences is essential for creating detailed microbial gene catalogs. These catalogs organize genes found in microbial communities and serve as references for standardized analysis across different samples and studies, making the accurate reconstruction of protein-coding sequences a crucial aspect of our evaluation [75]. Therefore, we assessed the performance of the assemblers in reconstructing proteins by predicting proteins from the reference genomes of our simulated metagenomes with short fragment length distribution and moderate damage using Prokka [76] and searching for highly similar proteins with MMseqs2 map [77] in the Uniref100 database [78].

Figure 5 shows the number of predicted open reading frames (ORFs, i.e., DNA translated into amino acid space) that exhibit significant similarity to predicted proteins from the reference genomes. We reported the number of unique matches in the reference. This approach allowed us to measure the assemblers’ ability to reconstruct biologically meaningful protein-coding sequences.

Fig. 5.

Evaluation of predicted protein sequences. Results are presented for CarpeDeam (safe and unsafe modes), MEGAHIT, metaSPAdes, and PenguiN across datasets with moderate damage and short fragment lengths in three simulated environments (bone, dental calculus, and gut) with varying coverage levels (3×, 5×, and 10×). The figure shows the number of predicted ORFs with significant similarity to reference proteins, filtered for alignments covering 90% of the reference protein and 90% sequence similarity

CarpeDeam’s unsafe mode consistently outperformed other assemblers in assembling more proteins (Fig. 5, panel A). However, for the 3× bone dataset, MEGAHIT assembled more proteins than CarpeDeam’s unsafe mode. Apart from the 3× bone dataset, MEGAHIT assembled significantly more proteins than CarpeDeam’s safe mode for the bone 5× and gut 3× datasets. In contrast, CarpeDeam’s safe mode assembled significantly more proteins for all 10× datasets, as well as the 3× and 5× calculus datasets. For the gut 5× dataset, MEGAHIT and CarpeDeam’s safe mode assembled a very similar number of proteins. The other assemblers assembled significantly fewer proteins across all datasets.

As Table 1 of the metaQUAST results indicates that CarpeDeam tends to assemble a higher rate of duplicated contigs compared to other assemblers. Therefore, we conducted additional analysis to assess the impact of duplications on downstream processes. Of particular interest was the potential inflation of unique protein sequence counts in our protein analysis due to duplicated sequences. To address this concern, we performed three additional analyses that account for duplication rates.

First, we clustered predicted proteins with the linclust [68] algorithm at 100% sequence identity and 80% coverage, then searched the cluster representatives against the predicted proteins from the reference using the MMseqs2 map [77] module.

Second, to account for potential duplicates in the reference itself, we clustered the predicted proteins from the reference at 100% sequence identity and 80% coverage. We then searched these clustered reference proteins against the predicted proteins from the contigs using MMseqs2 map.

Finally, we employed miniprot [79] to search the predicted proteins from the reference directly against the DNA contigs. This method bypasses potential undercalling by our protein predictor and focuses on protein-to-DNA alignments directly, providing a complementary perspective to the second analysis. We applied a filter to only obtain hits with at least 95% sequence identity and 95% coverage of the reference proteins. In all cases, we reported the number of unique proteins from the reference.

Overall, these additional analyses still favor CarpeDeam, although MEGAHIT recovers similar numbers of proteins especially in the 3× datasets. The detailed results of these analyses are visualized in the Additional file 1, Section S3.

Assembly of empirical datasets

Next, we extended our analysis to include 20 empirical metagenomic datasets from five distinct sample sites. These datasets were obtained from a study by Fellows Yates et al. [36] and represent ancient metagenomic samples from oral microbiomes of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. The datasets exhibit varying levels of damage, which we used as input for the damage pattern parameter of CarpeDeam. Detailed information about these samples is summarized in Table 2. For the damage pattern input parameter of CarpeDeam, we used the average damage rate across all taxonomies reported.

Table 2.

aDNA fragments statistics and sample metadata for the empirical ancient oral microbiome datasets from Fellows Yates et al. [36]

| Dataset | Microbiome origin | Period | # Reads (merged) | Length | N50 | GC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAF008.B0101 | Modern human | LSA | 8,929,849 | 35–141 | 53 | 56.17 |

| TAF016.B0101 | Modern human | LSA | 1,631,218 | 35–141 | 97 | 63.35 |

| TAF017.A0101 | Modern human | LSA | 1,879,275 | 35–141 | 82 | 56.46 |

| TAF017.C0101 | Modern human | LSA | 1,981,178 | 35–141 | 47 | 51.25 |

| TAF017.C0101.171215 | Modern human | LSA | 1,970,380 | 35–141 | 47 | 51.12 |

| TAF018.A0101 | Modern human | LSA | 5,361,000 | 35–141 | 84 | 63.17 |

| TAF018.B0101 | Modern human | LSA | 5,327,186 | 35–141 | 57 | 52.6 |

| EMN001.A0101 | Modern human | UP | 9,911,123 | 35–141 | 69 | 55.41 |

| ECO002.B0101 | Modern human | Meso | 9,173,902 | 35–141 | 48 | 49.44 |

| ECO002.C0101 | Modern human | Meso | 8,841,304 | 35–141 | 48 | 49.71 |

| ECO004.B0101 | Modern human | Meso | 7,748,024 | 35–141 | 52 | 50.08 |

| ECO004.C0101 | Modern human | Meso | 6,965,132 | 35–141 | 50 | 52.55 |

| ECO006.B0101 | Modern human | Meso | 7,533,408 | 35–141 | 64 | 61.37 |

| ECO010.B0101 | Modern human | Meso | 8,903,259 | 35–141 | 48 | 49.89 |

| OAK001.A0101 | Modern human | LSA | 6,252,614 | 35–141 | 48 | 57.32 |

| OAK003.A0101 | Modern human | LSA | 13,951,366 | 35–141 | 61 | 53.48 |

| OAK004.A0101 | Modern human | LSA | 10,976,392 | 35–141 | 53 | 54.21 |

| OAK005.A0101 | Modern human | LSA | 13,749,370 | 35–141 | 59 | 56.99 |

| GDN001.A0101 | Neanderthal | MP | 13,440,839 | 35–141 | 65 | 58.58 |

| GDN001.B0101 | Neanderthal | MP | 11,972,554 | 35–141 | 52 | 57.12 |

Library Prep indicates whether the sequencing data was paired-end. The table includes the total number of merged reads, minimum and maximum aDNA read lengths, N50, and GC content

LSA Later Stone Age, UP Upper aleolithic, Meso Mesolithic, MP Middle Paleolithic

Identification of homologous proteins in empirical datasets

Given the absence of ancient reference genomes for the empirical datasets, our evaluation focused on the proteome space. In the context of ancient prokaryotic samples, the ideal scenario would be to identify ancient proteins that exhibit strong similarity to existing sequences while remaining previously undiscovered. To maximize the detection of similar proteins from our assembled contigs, we employed a sensitive screening approach. We used the –easy-search module of MMseqs2 [77] with –search-type 4, which extracts all possible open reading frames (ORFs) from the contigs and searches the resulting amino acid sequences against a provided database. For this analysis, we queried the UniRef100 database [78], which encompasses over 400 million reference protein sequences.

The search results were subsequently filtered using stringent criteria: sequence identity (35%), E-value (E-12), and alignment length (100 residues). Figure 6, panel A, presents the number of unique hits in the UniRef100 database, considering only the best hit for each query based on the lowest E-value. This approach allows to assess the potential unknown protein content in our aDNA assemblies while maintaining only highly significant matches.

Fig. 6.

A Heatmap of unique UniRef100 protein hits for ORFs predicted from contigs assembled by CarpeDeam, MEGAHIT, PenguiN, and metaSPAdes across empirical samples (Grouped by sample site). Hits were filtered by E-value , identity, alignment length residues. B Venn diagrams of species-level taxonomic assignments from translated contigs queried against the Genome Taxonomy Database for the Datasets GDN001.A0101 and EMN001.A0101. C Recovered genome fraction for highly damaged taxa, as reported by metaQUAST

Figure 6, panel A, shows the number of unique protein hits per sample and assembler in a heatmap. The performance of assemblers varies considerably across samples. Overall, MEGAHIT and CarpeDeam generally performed best, with MEGAHIT clearly outperforming all other assemblers in the ECO and TAF samples. In contrast, CarpeDeam achieved the best results in the GDN, EMN and OAK samples.

Interestingly, although metaSPAdes did not perform as well as MEGAHIT in previous analyses, it assembled more unique protein hits in the EMN dataset. When comparing the safe and unsafe modes of CarpeDeam, the safe mode yielded more hits in most datasets, indicating the presence of frameshifts likely caused by misassemblies in the unsafe mode.

Exploring taxonomy assignment through contig translation into protein space

Another use case for assembled contigs is taxonomic classification. This approach offers several advantages over classifying individual short reads, especially in the context of aDNA analysis. Contig-based classification improves accuracy by leveraging longer sequences, which is particularly beneficial for ultra-short, degraded aDNA fragments. It also helps mitigate misclassifications caused by conserved regions or horizontal gene transfer events [32, 34, 80].

Considering these advantages, we assessed the performance of assemblers in recovering proteins informative for taxonomic assignment using two empirical datasets: EMN001.A0101 and GDN001.A0101. Open reading frames (ORFs) were extracted directly from the assembled contigs using the –easy-taxonomy module of MMseqs2 [34], which translates the contigs in all six reading frames and queries them against the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) [81].

It is important to note that this approach primarily focuses on detecting bacteria closely related to modern species, specifically those represented in the GTDB, which is derived from RefSeq and GenBank genomes. Consequently, this method may not necessarily identify completely unknown species. The discovery of novel species presents significant challenges, as potential misassemblies would require careful downstream analysis to ensure accurate identification and exclusion of misassembled sequences.

Given these considerations, we adopted a conservative approach with stringent criteria for taxonomic assignment. Matches were filtered to meet the following thresholds: a minimum of 95% sequence identity in amino acid space, at least 70% target protein coverage, and an E-value (E−6). This conservative strategy aims to minimize false positives while maintaining high confidence in the reported taxonomic assignments.

We quantified the number of distinct species identified by each assembler based on the proteome alignment (Fig. 6, panel B). This metric provides a comparative measure of the assemblers’ performance in recovering taxonomically informative sequences from our empirical aDNA samples.

Figure 6, panel B, row 1 presents the taxonomic assignment results for the GDN001 dataset. A substantial number of species were identified by all assemblers, with MEGAHIT and CarpeDeam (unsafe mode) sharing the largest common set. Notably, both MEGAHIT and CarpeDeam identified a considerable number of unique taxa, with MEGAHIT slightly outperforming CarpeDeam (234 vs. 218 unique taxa, respectively; first Venn diagram).

Row 2 of panel A displays results for the EMN001.A0101 dataset, revealing a similar pattern to GDN001.A0101. However, consistent with its lower damage rate, the assemblies of the EMN001.A0101 dataset yielded identifications for a larger number of taxa overall. CarpeDeam demonstrated a marginal advantage in unique taxa identification compared to MEGAHIT (605 vs. 529, respectively; third Venn diagram).

A key observation from this analysis is that no single assembler consistently outperforms the others. While the different algorithms naturally share a significant portion of their results, each assembler reveals unique findings.

To further evaluate the assemblers’ performance on highly damaged taxa, we focused on four species reported by Fellows Yates et al. [36] to exhibit damage patterns of up to 40% that were identified in both samples: Fretibacterium fastidiosum, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Tannerella forsythia, and Treponema denticola. We used the reference genomes of these taxa as input for metaQUAST [71] and reported the recovered genome fraction using a contig length cutoff of 500 bp.

The analysis of the GDN001.A0101 dataset revealed that CarpeDeam was the only assembler capable of recovering any fraction of a reference genome. While no assembler successfully recovered sequences from F. fastidiosum, T. denticola or T. forsythia, CarpeDeam in unsafe mode recovered approximately 0.07% of the F. nucleatum genome, whereas safe mode recovered around 0.025%.

In the EMN001.A0101 dataset, most assemblers recovered only small fractions of the reference genomes. Notably, MEGAHIT failed to assemble any contigs longer than 500 bp that mapped to either F. nucleatum or T. forsythia. Among the assemblers, CarpeDeam performed best, recovering the largest fractions for all four target species. Interestingly, the safe and unsafe modes of CarpeDeam showed similar performance, yielding comparable fractions of the reference genomes.

Table 3 shows the relative abundances of four species presented in Fig. 6, panel C, derived using MetaPhlan2 [82]. The abundances are generally very low (<1%) and differ between the datasets. In GDN001.A0101, T. forsythia is absent, while other species have abundances below 0.12%. Notably, only F. nucleatum had a small genome fraction assembled by CarpeDeam. In contrast, EMN001.A0101 shows higher abundances for F. nucleatum and F. fastidiosum (0.25%), correlating slightly better with the genome fractions recovered.

Table 3.

Relative abundances of bacterial species in the two samples as reported by Metaphlan2, found in the data repository of the study by Fellows Yates et al. [36]

| Species abundance in % | GDN001.A0101 | EMN001.A0101 |

|---|---|---|

| Fretibacterium fastidiosum | 0.11313 | 0.24148 |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | 0.03592 | 0.26263 |

| Tannerella forsythia | 0 | 0.02834 |

| Treponema denticola | 0.10765 | 0.02202 |

Overall, no clear proportional relationship is observed between relative abundance and genome recovery, likely due to the low abundances and approximative nature of the tools. Since the contigs were filtered to have a minimum length of 500 bp, this could also contribute to the lack of correlation.

Detection of rRNA genes and potential biosynthetic gene clusters

16S rRNA gene detection is widely used for phylogenetic analysis in metagenomic studies due to the conserved regions of the gene [83]. However, in aDNA studies, detection of the full-length (approximately 1500 bp [83]) 16S rRNA gene is challenging because of the short fragment lengths and characteristic damage patterns inherent to aDNA. Previous studies have targeted several of the nine hypervariable V1–V9 regions [84–89], which are considerably shorter, thereby requiring the reconstruction of only a few hundred base pairs rather than the full 1500 bp gene. Nevertheless, Ziesemer et al. [90] demonstrated that targeting specific hypervariable segments in aDNA studies remains challenging when using amplicon sequencing; in such cases, de novo assembly can significantly improve the recovery of either full genes or hypervariable regions.

We investigated the detection of 16S rRNA genes by assessing the number of unique hits detected across sequence identity thresholds ranging from 90 to 100%. To ensure robust capture of hypervariable regions, we required that the annotated contigs span at least 80% of a 16S rRNA gene. In Fig. 7, panel A, we present the number of unique hits across different sequence identity thresholds rather than relying on a single cutoff.

Fig. 7.

A Detection of 16 s rRNA genes. Shown are the numbers of unique hits in the SILVA database from assembled contigs that were annotated with Prokka and filtered by sequence identity thresholds (90% to 100%) and a minimum coverage of 80%. B Identification of BGC protoclusters in the OAK003 sample using antiSMASH

For the GDN001.A0101 dataset, all assemblers performed similarly; however, CarpeDeam in both modes recovered more 16S rRNA hits (< 200) compared to other assemblers (< 150) at the 90% similarity threshold. The number of hits converged with increasing sequence identity, and no assembler reconstructed 16S rRNA genes with sequence similarity above 95%. At 95%, metaSPAdes recovered the most hits (11), followed by CarpeDeam and MEGAHIT.

In contrast, the EMN001.A0101 dataset showed a significantly different result. Only CarpeDeam assembled 16S rRNA genes, with the unsafe mode recovering over 2500 hits and the safe mode over 1500 hits at the 90% similarity threshold. At 95% similarity, both modes of CarpeDeam converged, still recovering over 600 unique hits.

For a deeper investigation of the 16S rRNA genes in the EMN001.A0101 dataset, we examined contigs that aligned to the SILVA database covering at least 99% of a full-length 16S rRNA gene with a minimum sequence identity of 95% (a threshold commonly used for genus-level identification [91–93]). CarpeDeam was the only assembler that produced contigs meeting these criteria. We then assigned taxonomic labels to the recovered 16S rRNA genes and compared these with the genera reported by Fellows Yates et al., where they were using a read alignment approach. To rule out contamination, we also compared the detected genera against a catalog of potential contaminants provided by Fellows Yates et al.. Additionally, we mapped the reads back to the genes to validate their ancient authenticity (PyDamage [94] results in the external data repository). Notably, CarpeDeam recovered three genera on species level (Actinobacteria, Brachymonas, and Johnsonella, shown in bold in Table 4) that were absent in the Fellows Yates et al. study and not listed as contaminants. In total, we identified five taxa on species level (sequence similarity 99% [95]) and five taxa on genus level (sequence similarity 95% [91–93]). Overall, this analysis underscores the enhanced sensitivity of CarpeDeam and demonstrates its suitability as a complementary method for taxonomic identification alongside read mapping approaches. The result is also remarkable given the low sequencing depth, as the EMN001.A0101 dataset comprised fewer than 10 million merged reads.

Table 4.

Best hit alignments of assembled contigs to the SILVA 16S rRNA gene database for the EMN001.A0101 dataset

| Sequence similarity | 16S rRNA gene coverage | |

|---|---|---|

| Species level identification | ||

| Brachymonas sp. canine oral taxon 015 | 0.988 | 1.0 |

| Johnsonella ignava ATCC 51276 | 0.998 | 1.0 |

| Propionibacterium sp. oral taxon 192 str. F0372 | 0.998 | 1.0 |

| Desulfobulbus oralis | 0.998 | 0.996 |

| Streptococcus sanguinis SK150 | 0.994 | 0.997 |

| Genus level identification | ||

| Actinobacteria bacterium canine oral taxon 406 | 0.983 | 1.0 |

| Aggregatibacter aphrophilus | 0.987 | 1.0 |

| Chlorobium sp. ShCl03 | 0.966 | 0.999 |

| Actinomyces slackii | 0.960 | 0.998 |

| Pseudopropionibacterium massiliense | 0.952 | 0.999 |

Bold entries denote three species that were not detected by Fellows Yates et al. using the MALT approach. The values for sequence similarity and gene coverage correspond to the highest scoring alignment for each genus

Additionally, we evaluated the assemblers’ ability to reconstruct contigs containing biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). Figure 6 (panel A) indicates that the OAK samples are the most protein-rich. Accordingly, we selected the OAK003 sample for further analysis. Using antiSMASH [96], we screened the contigs from each assembler for BGCs and reported the number of protoclusters per BGC type. A protocluster is defined as a genomic region that contains the core biosynthetic genes for a specific secondary metabolite along with its neighboring genes. Based on curated detection rules, each protocluster corresponds to a single product type [97].

Figure 7 (panel B) shows that antiSMASH identified 11 distinct protocluster types across all assemblers. Both CarpeDeam modes contain the highest number of protoclusters, with 62 identified in safe mode and 52 in unsafe mode. MEGAHIT contains 25 protoclusters, PenguiN contains 10, and metaSPAdes contains 8. The distribution of protocluster types varied among assemblers. For example, MEGAHIT did not detect any RRE-containing, lassopeptide, or terpene protoclusters, which were present in the CarpeDeam assemblies.

Another notable difference was observed in the total number of aligned nucleotides. We searched the protein sequences reported by antiSMASH against the nr database [98] and summed the alignment lengths of the best hits, determined by the lowest E-value. The safe mode of CarpeDeam assembled sequences with more than twice the total aligned length (in base pairs) compared to MEGAHIT. When aligning the BGC protocluster sequences against the nr database, the best hits had a median sequence similarity exceeding 92% for CarpeDeam, MEGAHIT, and metaSPAdes, while PenguiN showed a lower median similarity of over 83%. To ensure ancient authenticity, we mapped the OAK003 reads against the BGC-involved contigs, all of which exhibited characteristic nucleotide substitutions at the fragment ends (see PyDamage [94] results in the external data repository).

Discussion

Evaluating assembly algorithms: understanding strengths, limitations and underlying assumptions

The reconstruction of full-length genes or entire genomes from ancient metagenomes poses significant challenges for de novo assemblers. De novo assembly of metagenomic samples is already complex for modern samples and it becomes exceptionally challenging with aDNA due to its degraded nature, characterized by extremely short fragment sizes and deaminated nucleotides.

While modern metagenomic assemblers like MEGAHIT [58] and metaSPAdes [59] are widely used, their de Bruijn Graph implementations face a precision-sensitivity trade-off when dealing with highly complex datasets [62, 65]. As graph complexity increases, these tools must employ simplification strategies, potentially compromising assembly completeness or accuracy, especially in regions of high genomic diversity or low coverage.

PenguiN [62] addresses this issue through a greedy iterative overlap approach, leveraging whole read information for improved performance in variant-rich datasets. Ancient metagenomic datasets, particularly those from poorly preserved samples, present additional challenges for both de Bruijn graph and overlap-based assembly strategies. Base substitutions in aDNA fragments artificially increase the genomic diversity in metagenomic samples. Deep sequencing can facilitate assembly [17], but it may be impractical due to sample limitations or cost constraints [6].

Our tool, CarpeDeam, builds upon PenguiN’s whole-read approach, incorporating a maximum-likelihood framework that utilizes sample-specific damage pattern matrices for contig correction and extension. Given the close relationship between CarpeDeam and PenguiN, with large parts of their algorithms sharing the same codebase, it is essential to clarify their distinctions.

Both assemblers share a foundational concept – leveraging the MMseqs2 linclust algorithm to cluster reads based on shared k-mers, yet they differ significantly in their suitability for assembling aDNA datasets. Overall, clustering by shared k-mers enables both tools to extend sequences in an overlap-based consensus approach. This method avoids an all-vs-all read comparison, which scales quadratically with the number of input reads and is thus computationally infeasible.

In both assemblers, a cluster is defined by sequences that not only share at least one k-mer with the cluster representative (the longest sequence) but also meet a sequence similarity threshold regarding the overlapping portions of two sequences. For PenguiN, this threshold is set to 99% by default, meaning that within the overlap of a member sequence and its cluster representative, at least 99% of the bases must be identical [62]. The assumption that sequences belonging to the same cluster are highly similar makes PenguiN particularly well-suited for assembling viral genomes or microbial 16S rRNAs from modern, non-ancient metagenomic samples, which it was specifically designed for. Furthermore, PenguiN uses a Bayesian framework to infer the most likely extension, given the observations of overlap length and sequence similarity. PenguiN’s framework relies on the premise that mismatches in overlapping reads are rare and primarily arise from sequencing errors. Sequencing errors, especially in modern Illumina datasets, tend to be minimal (< 0.1–0.6%) [99] and can be further reduced upstream of assembly by quality filtering reads before assembly [100]. Consequently, PenguiN does not include a base correction algorithm; it relies on overlaps between presumed high-quality reads for accurate assembly.

However, this design makes PenguiN unsuitable for aDNA assembly. aDNA fragments inherently contain postmortem base substitutions, which artificially inflate sequence diversity and disrupt assumptions about sequence identity. Without correcting these substitutions, PenguiN faces two critical challenges. First, damaged reads may fail to cluster because the sequence mismatches caused by deaminations reduce overlap identity below the required 99% threshold. Second, even if damaged reads do cluster and overlap, the accumulation of deaminated bases during iterative extensions can propagate errors, further hindering assembly. While it is possible to lower the sequence identity threshold, as we did with CarpeDeam, this alone does not address the issue of accumulating damage.

These challenges are addressed by CarpeDeam, which incorporates damage-aware correction, extension, and RY-mer sequence identity filtering to adapt PenguiN’s sensitivity for aDNA samples.

To maintain objectivity, we ran all assemblers in their default modes, as this reflects the typical approach researchers might take when applying these tools. However, we recognize that the performance of assemblers may vary depending on parameter settings, particularly for challenging datasets such as aDNA. In our case, we noticed that metaSPAdes encountered issues during the error correction step, which is designed to address sequencing errors rather than ancient DNA damage. To proceed, we followed the advice provided by the developers in a related GitHub issue (see the “Results,” subsection “Simulated Data,” and ran metaSPAdes in “only assembler” mode as suggested. Given the unique characteristics of ancient DNA, a comprehensive parameter benchmarking study could provide valuable insights into optimizing assembly strategies. However, such an exploration is beyond the scope of the current manuscript.

Significant impact of fragment length distribution and damage patterns on the assembly process

Our extended analysis of simulated aDNA samples, incorporating three fragment length distributions (medium, short, and ultra-short), three levels of DNA damage (moderate, high, and ultra-high), and three depths of coverage (3×, 5×, and 10×), revealed that all these factors significantly influence the de novo assembly of aDNA samples.

Modern de novo assemblers are generally designed to handle sequencing reads that, when merged upon assembly, are several hundred base pairs in length. In a paired-end sequencing context, read lengths typically range from 2 × 75 bp to 2 × 300 bp [101], providing a very different starting condition compared to aDNA samples. aDNA molecules are heavily degraded, resulting in short DNA fragments with read length distributions peaking well below 100 bp [102]. These distributions often follow an inverse exponential relationship between fragment length and abundance [103]. A commonly used metric, the median fragment length, serves as an informative proxy for estimating the most abundant read size, which is expected to significantly influence the assembly process.

Our simulations support this observation to some extent. Larger median fragment lengths and more uniform length distributions, such as those observed in the medium fragment length distribution used in this study (Additional file 1, Fig. S1 (A)), positively impact assembly quality. However, we also observed that rare long fragments (> 100 bp) seemingly have a disproportionate influence on assembly outcomes. Despite being a small minority, these long sequences appear to act as exceptionally useful anchors, enabling assemblers to produce more contiguous and less fragmented assemblies. This effect was observed in both de Bruijn graph assemblers, MEGAHIT and metaSPAdes, and was even more pronounced in the overlap-consensus assemblers, CarpeDeam and PenguiN.

Damage levels also had a significant influence on assembly quality. The three damage levels used in this study (moderate, high, and ultra-high) differ in two key aspects. First, the maximum damage at the first position of a fragment varies considerably, with substitution rates ranging from 0.33 in moderate damage to 0.58 in ultra-high damage. Second, the damage levels differ in their slope, representing how quickly substitution rates decline along the fragment. For example, while ultra-high damage exhibits a substitution rate of only 0.05 at position 5, moderate damage maintains a substitution rate of approximately 0.14 at the same position.

Interestingly, all assemblers struggled more with the moderate damage level and its lower decline rate compared to the ultra-high damage level, as demonstrated in the Additional file 1, Section S2. This counterintuitive result can be explained by the mechanics of the assembly algorithms.

For de Bruijn graph-based assemblers, such as MEGAHIT and metaSPAdes, the extraction of k-mers as building blocks presents a challenge. These assemblers often start with or higher [58, 59]. With already short fragment lengths, the number of k-mers that can be extracted is limited. For instance, in the case of a 40-bp read where the first and last 5 bases have relatively high substitution rates, only the central portion of the read contributes k-mers that accurately represent the original sequence. k-mers spanning damaged regions are more likely to contain mismatches, making it difficult to find matching k-mers from other reads, and thereby impeding graph extension.

Overlap-based assemblers, such as CarpeDeam and PenguiN, face a different set of challenges. Reads are clustered together based on shared k-mers, but the full overlap must meet a minimum sequence identity threshold (90% for CarpeDeam, 99% for PenguiN). For ultra-short reads with high substitution rates in the first few positions, the sequence identity can quickly fall below these thresholds. While lowering the threshold could mitigate this issue, it would significantly increase computational resource usage (due to larger clusters) and the risk of misassemblies.

These findings are critical for future studies utilizing de novo assembly for aDNA and highlight the importance of developing methods specifically optimized for highly fragmented and damaged DNA.

Impact of coverage depth on the assembly process and the issue of misassemblies

The role of coverage depth in the assembly process has been risen in other studies as well. For instance, Klapper et al. [17] assembled ancient metagenomic datasets to identify biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), leading to the experimental validation of previously unknown molecules. Their findings showed that while modern metagenomic samples produced more contiguous assemblies than ancient samples, deeply sequenced ancient metagenomes achieved similarly high-quality assemblies [17].

Our simulations support this observation. Higher average coverage depths consistently resulted in better assemblies across multiple metrics. However, as detailed in Additional file 1, Section S2, current assemblers still face challenges when dealing with the short fragment lengths and high levels of damage. For instance, while MEGAHIT often achieved genome fractions comparable to CarpeDeam, it underperformed in terms of largest alignment and NA50. This highlights the limitations of assemblers not specifically designed for aDNA, even under high-coverage conditions.

Another study by Jackson et al. [104] demonstrated as well that deeply sequenced samples could be successfully assembled with MEGAHIT. However, deep sequencing is often impractical due to sample limitations or cost constraints [6].

The improved performance of de Bruijn graph-based assemblers with high coverage is straightforward to explain: higher coverage ensures that genome positions are more likely to be covered by k-mers free of deaminated bases, enabling more contiguous paths through the assembly graph. Theoretically, the same principle applies to overlap-based assemblers like CarpeDeam and PenguiN. While higher coverage datasets in our simulations led to improved assembly metrics overall, a significant misassembly rate could be observed. In unsafe mode, CarpeDeam exhibited particularly high misassembly rates, especially in high-coverage datasets.

This issue led to the introduction of the safe mode for CarpeDeam. In early assembly stages, short reads may overlap with 100% sequence identity, particularly in cases involving mobile genetic elements (MGEs) shared between species [105]. Under these conditions, the assembler cannot reliably distinguish sequences from different species. Graph-based assemblers handle this by marking such regions as diverging paths, effectively “cutting” contigs at these points, resulting in shorter but accurate assemblies. The safe mode of CarpeDeam addresses this issue by utilizing a consensus calling mechanism, thereby reducing misassembly rates severalfold, albeit at the cost of shorter contigs. Users can alternatively choose the unsafe mode, which disables the consensus calling mechanism, potentially increasing sensitivity but at the risk of producing more misassembled or chimeric contigs.

It must be noted that it might seem counterintuitive why CarpeDeam’s unsafe mode exhibited exceptionally high misassembly rates in high-coverage datasets, where higher coverage should theoretically improve assembly. We believe that this is triggered by sequences of highly abundant species. In some cases, clusters may contain reads that overlap perfectly with the center sequence at 100% identity. While the correct extension may originate from a less abundant species, the assembler is more likely to select a perfectly overlapping but incorrect sequence from the most abundant species, leading to misassemblies. A detailed investigation of this issue is provided in Additional file 1, Section S4, where we are showing that identical sequences can occur within a single genome or between genomes of different species, with considerable variation across prokaryotic taxa [105, 106] (Additional file 1 Figs. S16 and S17).

Our observations highlight the trade-off between sensitivity and accuracy in metagenomic assembly, especially in the context of aDNA and diverse prokaryotic communities. The availability of safe and unsafe modes allows users to adjust the assembly approach based on their specific research goals and the nature of their datasets.

A potential future solution could involve incorporating a graph-like structure within the clusters sharing a k-mer, combining the overlap-based approach with the flexibility of graph assemblers. However, this approach requires further research. Downstream analyses – such as protein prediction or contig alignments against reference databases – can help identify misassembly breakpoints, enabling researchers to extract valuable insights from the contigs for further investigation.

Protein-centric approaches in aDNA research

We assembled 20 empirical datasets from 5 sample sites, two of which were further analyzed for taxonomic classification. The results underscore the potential of protein prediction in aDNA research to uncover novel insights. Protein prediction becomes feasible only with sequences that are sufficiently long for ORF prediction, which is challenging when dealing with inherently short aDNA reads. As highlighted by Borry et al. [94], predicting ORFs directly from ancient DNA reads is extremely difficult, if not impossible, with current tools. By contrast, de novo assembly generates sequences long enough for ORF prediction.

Proteins offer unique advantages in aDNA research as they are more conserved than nucleotide sequences. Modern tools like MMseqs2 [77], and DIAMOND [107] enable rapid and sensitive screening of translated sequences against large protein databases. These advantages highlight the potential of protein-centric approaches for the discovery of functional elements and taxonomic profiling in aDNA datasets.

Gene- and protein-centric approaches have already demonstrated success in related fields. Klapper et al. [17] identified and experimentally validated bioactive molecules from biosynthetic gene clusters in ancient metagenome-assembled genomes. Wan et al. [50] applied deep learning to analyze proteomes of extinct organisms, identifying potential antimicrobial peptides effective against highly pathogenic bacteria. Such studies could benefit from advanced de novo assembly methods with higher sensitivity, such as those provided by CarpeDeam.