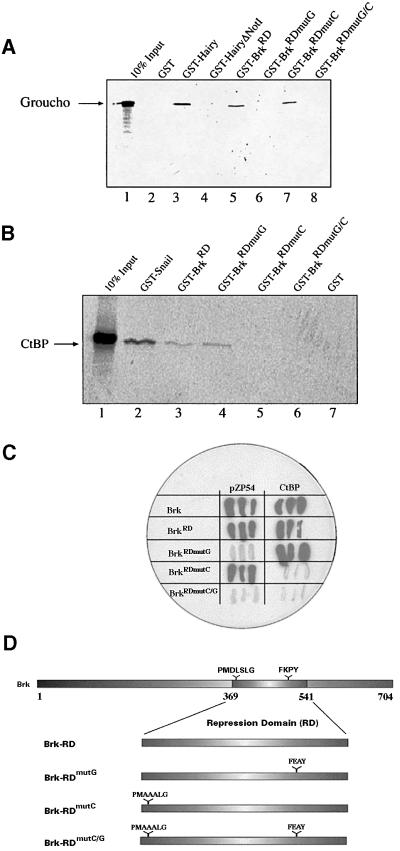

Fig. 2. Brk interacts physically with Gro and CtBP. (A and B) In vitro pull-down assays. 35S-labelled Gro (A) or dCtBP (B) were incubated with GST–BrkRD derivatives immobilized on glutathione–agarose beads and, following washing, retained 35S-labelled protein was subjected to SDS–PAGE (not shown) and autoradiography. (A) Gro binds specifically to GST–BrkRD (lane 5) and to GST–BrkRDmutC (lane 7), but not to GST–Brk variants in which Brk’s FKPY motif is mutated (lanes 6 and 8). GST–Hairy (lane 3) serves as a positive control, whereas Hairy lacking its C-terminal Gro-binding domain (HairyΔNotI, lane 4) and GST alone (lane 2) are negative controls. (B) CtBP binds specifically to GST–BrkRD (lane 3) and BrkRDmutG (lane 4), although to a lesser extent than to GST–Snail (lane 2), an established CtBP partner (Nibu et al., 1998a). Mutating Brk’s CtBP recruitment core motif abolishes CtBP binding (lanes 5 and 6). GST alone, lane 7. (A and B) 10% of input-labelled protein was run in lane 1. Arrows indicate positions of full-length Gro (A) and CtBP (B). (C) Yeast two-hybrid assay. Full-length Brk, or just its RD, interacts strongly in yeast with full-length Gro (not shown), with pZP54 (Gro251–719) and with CtBP (white colonies indicate lack of interactions). Mutating either the Gro or CtBP recruitment motif in Brk’s RD results in loss of interactions between Brk and the corresponding corepressor. (D) A schematic representation of Brk’s RD (residues 369–541) and derived constructs. The Brk corepressor recruitment motifs, and respective mutant versions, are indicated.

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov website belongs to an official

government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock (

) or https:// means you've safely

connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive

information only on official, secure websites.