Abstract

Objectives:

Transitional foods are foods that start as one texture and change to another with minimal chewing required. While transitional foods have been promoted for pharyngeal swallowing dysfunction, their effects on swallowing safety and efficiency are not well understood. The aims of this study were to characterize differences in swallowing efficiency and safety between transitional, pureed, and regular food textures.

Methods:

This was a retrospective study of consecutive outpatient adults who underwent flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) at a multidisciplinary dysphagia clinic. FEES were used to obtain measures of swallowing safety and efficiency and were included if containing at least one trial of transitional, pureed, and regular food textures. FEES were blindly analyzed by pairs of raters. Multilevel statistical models were used to compare differences in outcome measures across textures.

Results:

A total of 219 swallowing trials were analyzed. A greater number of swallows was required for pureed compared to transitional foods (p = .011). There was a greater amount of epiglottic residue (p < .05) and oropharyngeal residue (p < .0001) for pureed and regular foods compared transitional foods (p < .05). There was also a greater amount of hypopharyngeal residue for pureed compared transitional foods (p < .0001). Differences in swallowing safety could not be determined.

Conclusion:

Transitional foods were associated with better swallowing efficiency than pureed and regular food textures in this heterogenous sampling of dysphagic adults. Future research should prospectively assess the effects of transitional foods on swallowing safety and efficiency in specific dysphagic populations.

Keywords: Flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES), transitional foods, pharyngeal residue, IDDSI

Introduction

In speech-language language pathology (SLP) and otolaryngology-head and neck surgery (OHNS) clinical practice, diet texture modification (DTM) is one commonly used intervention for people with dysphagia. DTM include changing the viscosity of liquids and/or modifying solid foods using standardized guidelines 1. While the effects of DTM on long-term health outcomes is unclear 2, current research demonstrate DTM can result in immediate changes in swallowing safety (penetration/aspiration) and efficiency (e.g., mealtime length, number of swallows, oral residue, pharyngeal residue) 3,4. For example, thickened liquids tend to flow slower than thin liquids from the oral cavity to the esophagus contributing to less frequent occurrences of airway invasion 5–10. DTM is a common approach to make foods easier to chew and swallow, particularly for individuals with dental issues or masticatory muscle weakness 11.

Transitional foods are a unique category of DTM that have been introduced into clinical practice through the International Dysphagia Diet Standardization Initiative (IDDSI) framework. IDDSI provides a new global guideline on texture modification and standardization of terminology and definitions for DTM and liquids applicable to individuals with swallowing dysfunction of all ages, in all care settings, and all cultures 12. IDDSI defines a transitional food as, ‘food that starts as one texture (e.g., firm solid) and changes into another texture specifically when moisture (e.g., water, saliva) is applied, or when a change in temperature occurs (e.g., heating)’ 13. According to IDDSI, transitional foods require no biting, minimal chewing, and can be broken down with the tongue, making them ideal for individuals with chewing difficulties 14. Some examples of transitional solid foods as noted by IDDSI, include Veggie Stix™, Cheeto Puffs™, Baby MumMum™, and Gerber Graduate Puffs™ 15.

Distinct textural properties of transitional foods allow them to be easily deformed. This characteristic may facilitate more safe and efficient clearance through the pharynx during swallowing compared to their original texture 16. Although transitional food texture properties and behaviors have been studied before 14,17, there is little research on the use of transitional foods in the adult population with dysphagia. One recent study used videofluoroscopic analysis of swallowing safety, efficiency, and kinematics between transitional and pureed foods, but found no statistically significant differences between food types18. However, a limitation of this study was that Varibar barium sulfate pudding was added to both foods in order to be viewed on fluoroscopy, potentially impacting the natural textural proprieties of these foods. Therefore, additional research is needed to instrumentally compare differences in measures of swallowing physiology and function between transitional and non-transitional food types.

Importantly, while it has been well-established that ratings of pharyngeal residue, penetration, and aspiration can change as an effect of liquid type and color during FEES,19–24 and that ratings of pharyngeal residue can change as an effect of puree type and color during FEES,25 no studies have investigated whether or how ratings of safety (penetration/aspiration) and efficiency (pharyngeal residue) are affected in transitional foods in dysphagic outpatient adults during FEES. Understanding whether transitional foods compared to other foods impacts these ratings is important for understanding whether transitional foods may offer benefits to patients with deglutitive dysfunction and may be incorporated in standardized FEES protocols for management.

The aim of this study was to assess the effects of transitional foods on swallowing safety and efficiency by comparing penetration-aspiration, number of swallows and amount of post-swallow residue between transitional, pureed, and regular food textures in outpatient dysphagic adults. We hypothesized that transitional foods would exhibit greater swallowing safety and efficiency when compared to regular but not pureed foods.

Methods

This was a retrospective study approved by the Institutional Review Board at Weill Cornell Medicine (IRB #: 22–07025080). Informed consent was not required by the Institutional Review Board for this retrospective review.

Participants

A retrospective review was conducted of patients with dysphagia who were evaluated at a multidisciplinary outpatient dysphagia clinic staffed by a speech-language pathologist and a laryngologist between September 2022 and January 2023. Each patient underwent a standard-of-care flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) by a speech-language pathologist. FEES was performed by one speech-language pathologist with 9 years of clinical experience and dysphagia expertise. FEES were included for analysis if at least one trial of a pureed (Mott’s applesauce), transitional solid (Savorease™ Crispy Melts), and regular (Nabisco graham cracker) food texture. Savorease™ Crispy Melts is a transitional food that quickly dissolves when moistened.14 Each food texture aligned with the IDDSI definitions of the transitional, IDDSI Level 4 (pureed), and IDDSI Level 7 (regular) foods. FEES were excluded from analysis if one of the three food textures was missing, or if endoscopic visualization was absent due to obscuring of the camera lens.

Collected demographic data included age, sex, and primary medical diagnosis. Dysphagia severity measures were extracted from patients’ medical charts, including patient-reported Functional Oral Intake Scale (FOIS) 26, clinician-reported FOIS, Eating Assessment Tool-10 (EAT-10)27, secretion severity scale rating 28 and maximum Penetration-Aspiration Scale (PAS) 29 based on FEES.

Procedures & Equipment

FEES equipment consisted of a 2.4 mm diameter flexible distal chip laryngoscope (VNL8-J10, PENTAX Medical, Montvale, NJ), a video processor with an integrated xenon light source (DEFINA EPK-300, PENTAX Medical), and an LCD display. Approximately 0.1 mL of liquid mixture solution of lidocaine and neo-synephrine was aerosolized to each naris 3 minutes prior to the start of the FEES to optimize patient comfort 30. No lubrication was used prior to scope insertion. White balancing was not routinely performed at the start of every exam. FEES was then initiated by passing a flexible laryngoscope transnasally to view the pharynx, larynx, and subglottis before and after the swallow of various food and liquid consistencies.

FEES were completed with patients seated comfortably in an upright position in an exam room chair. A clinic standardized swallowing protocol was planned for each patient and included a range of bolus volumes and consistencies. Patients were presented with two trials of each of the following three food types in the same fixed order: applesauce, Crispy Melts, graham cracker (Figure 1). However, due to safety concerns and logistical considerations, not all patients were presented with two trials of each food texture. For the applesauce, patients were presented with a teaspoon of applesauce (~5.3 g/5ml) and asked to put it in their mouth and swallow it like they normally would. For the Crispy Melts, patients were presented with a single Crispy Melts (~0.3–0.5g), asked to put all of it in their mouth and swallow as they normally would. For the graham cracker, patients were presented with a half-graham cracker (~3.8g) and asked to take a single bite from that cracker and swallow it like they normally would. The graham cracker bite sizes were not systematically recorded, but were observed to be half or less of the cracker presented. White food coloring (four drops of AmeriColor™ Bright White Soft Gel Paste) was added to a four-ounce container of applesauce to enhance endoscopic visualization 23. No food coloring was added to the Crispy Melt or graham cracker to avoid altering textural properties.

Figure 1:

Picture of food trials as presented to the patient (left to right): pureed food—a teaspoon of applesauce (~5.3 g); Transitional food—one Crispy Melts (~0.3–0.5 g), and regular food—half a graham cracker (~3.8 g). Patients were instructed to consume applesauce and Crispy Melt in one bite and swallow as they normally would. Patients were instructed to take a single bite from the graham cracker as they typically would and swallow.

Data Analysis & Outcome Measures

FEES videos were saved to endoPortal cloud-based software (KayPENTAX endoPortal 2.2.0, Montvale, NJ) upon patient encounter completion. FEES videos were subsequently downloaded from endoPortal prior to blinded analysis. The first author identified and recorded the time points for each swallowing trial to be blindly analyzed.

FEES videos were randomly assigned to one of two raters – each rating 50% of the total sample using the Visual Analysis of Swallowing Efficiency and Safety (VASES). Raters were blinded to study aims, demographic information, and food texture being rated. FEES videos were rated in the order with which they were recorded using QuickTime player (Apple) for frame-by-frame analysis.

VASES was used to facilitate the standardized measures of swallowing efficiency and safety 31,32. Measures of swallowing efficiency included number of swallows and amount of oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and epiglottic residue. Measure of swallowing safety was the 8-point Penetration-Aspiration Scale (PAS) 33. PAS was used to describe the depth of and reaction to airway invasion, with a score of 1 indicating no penetration/aspiration, scores 2–5 representing varying severity levels of laryngeal penetration, and scores 6–8 representing varying severity levels of aspiration.

After all data were blindly analyzed, residue rating data were plotted to identify outliers. Outliers were re-analyzed by a third rater, who was blinded to the original ratings, to assess for the potential of extreme measurement error. If the residue ratings differed by >10, then the new residue rating was used to replace the previous outlier. If the new residue rating differed by ≤10, then the original residue rating was kept. Once resolution of outliers was completed, 20% of the final dataset was randomly selected for repeated analysis by the two graduate interns to assess intra-rater reliability for this within-subject study design.

Statistical Analysis

All data were statistically analyzed using R version 4.1.1 34. Data and R code are openly available at the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/cmnv8/?view_only=27cb76dd90624af099992b608964d478). An alpha of p < 0.05 was used as the level of statistical significance. Given the exploratory nature of this study, no adjustments were used to correct for multiple statistical comparisons.

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize outcome measures across the three bolus consistencies. Odds ratios (O.R.) were used as standard effect sizes for all statistical models. Multilevel beta regressions were used to examine the relationship between food textures (transitional, pureed, regular) and oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and epiglottic residue ratings. Ordinal cumulative link multilevel models were used to examine the relationship between food texture, number of swallows, and PAS. Participant was treated as a random effect for all multilevel models. Because number of swallows may significantly impact residue ratings, and preliminary analysis was performed to determine if number of swallows should be treated as a fixed effect for the residue rating models. This revealed that number of swallows significantly influenced oropharyngeal residue ratings, but not hypopharyngeal or epiglottic residue ratings. Therefore, number of swallows was included as a fixed effect covariate for the oropharyngeal residue model.

Intra-rater reliability was examined using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for all continuous variables (residue ratings). ICCs were calculated using a two-way, random effects, absolute agreement, single rater model. Weighted Cohen’s Kappa (κw) was used to measure intra-rater reliability for all ordinal data (number of swallows; PAS). Linear weights were applied to Kappa for the number of swallows outcome since the difference between two adjacent categories (1–2 swallows) is the same for all adjacent categories (e.g., 2–3 swallows, 3–4 swallows, 4–5 swallows, etc.). Quadratic weights were applied to Kappa for the PAS outcome since the difference between two adjacent categories are not conceptually linear in nature 35.

Results

A total of 41 FEES were identified from 39 unique patients, yielding an analysis of 219 swallowing trials. These trials included 78 transitional food trials, 75 pureed food trials, and 66 regular food trials. Patients included 28 males and 11 females, with an average age of 74 years (SD = 15.6) and a range of medical diagnoses and estimated dysphagia severity levels (Table 1).

Table 1:

Demographics Table

| Total (N=39) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean (SD) | 75.6 (14.5) |

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 78.0 [68.5, 86.0] |

| Min, Max | 35.0, 99.0 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 11 (28.2%) |

| Male | 28 (71.8%) |

| Neurologic Disease | |

| No | 26 (66.7%) |

| Yes | 13 (33.3%) |

| Respiratory Disease | |

| No | 35 (89.7%) |

| Yes | 4 (10.3%) |

| Cricopharyngeal Dysfunction | |

| No | 29 (74.4%) |

| Yes | 10 (25.6%) |

| Other Medical Diagnosis | |

| Cervical osteophytes | 6 (15.4%) |

| Esophageal | 5 (12.8%) |

| Skull base surgery | 4 (10.3%) |

| Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion (ACDF) | 3 (7.7%) |

| Other- vocal fold changes | 2 (5.1%) |

| Rheumatic disease | 2 (5.1%) |

| Lung cancer | 1 (2.6%) |

| Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) | |

| Mean (SD) | 16.1 (11.3) |

| Median [Q1, Q3] | 14.0 [6.75, 25.5] |

| Min, Max | 0, 40.0 |

| Missing | 3 (7.7%) |

| Functional Oral Intake Scale (FOIS): Patient-Reported | |

| 2 | 2 (5.1%) |

| 3 | 3 (7.7%) |

| 5 | 7 (17.9%) |

| 6 | 17 (43.6%) |

| 7 | 10 (25.6%) |

| FOIS: Clinician-Recommended | |

| 2 | 1 (2.6%) |

| 3 | 3 (7.7%) |

| 5 | 11 (28.2%) |

| 6 | 14 (35.9%) |

| 7 | 10 (25.6%) |

| Maximum Penetration-Aspiration Scale (PAS) Scores | |

| 1 | 8 (20.5%) |

| 2 | 3 (7.7%) |

| 3 | 8 (20.5%) |

| 4 | 1 (2.6%) |

| 5 | 6 (15.4%) |

| 6 | 1 (2.6%) |

| 7 | 6 (15.4%) |

| 8 | 6 (15.4%) |

| Secretion Severity Scale | |

| 0 | 20 (51.3%) |

| 1 | 12 (30.8%) |

| 2 | 2 (5.1%) |

| 3 | 5 (12.8%) |

Abbreviations: Sample size (n); Standard Deviation (SD); 25th percentile (Q1); 75th percentile (Q3)

Intra-rater reliability for each outcome was: Number of Swallows κw = 0.782 (absolute agreement = 84.1%); Oropharyngeal Residue ICC = 0.842 (95% CI: 0.728 – 0.910; average absolute difference = 4.39%); Hypopharyngeal Residue ICC = 0.860 (95% CI: 0.759 – 0.921; average absolute difference = 2.25%); Epiglottic Residue ICC = 0.910 (95% CI: 0.841 – 0.950; average absolute difference = 3.11%); PAS κw = 0.940 (absolute agreement = 95.5%).

Aim 1: Differences in Swallow Efficiency Across Transitional, Pureed, and Regular Foods

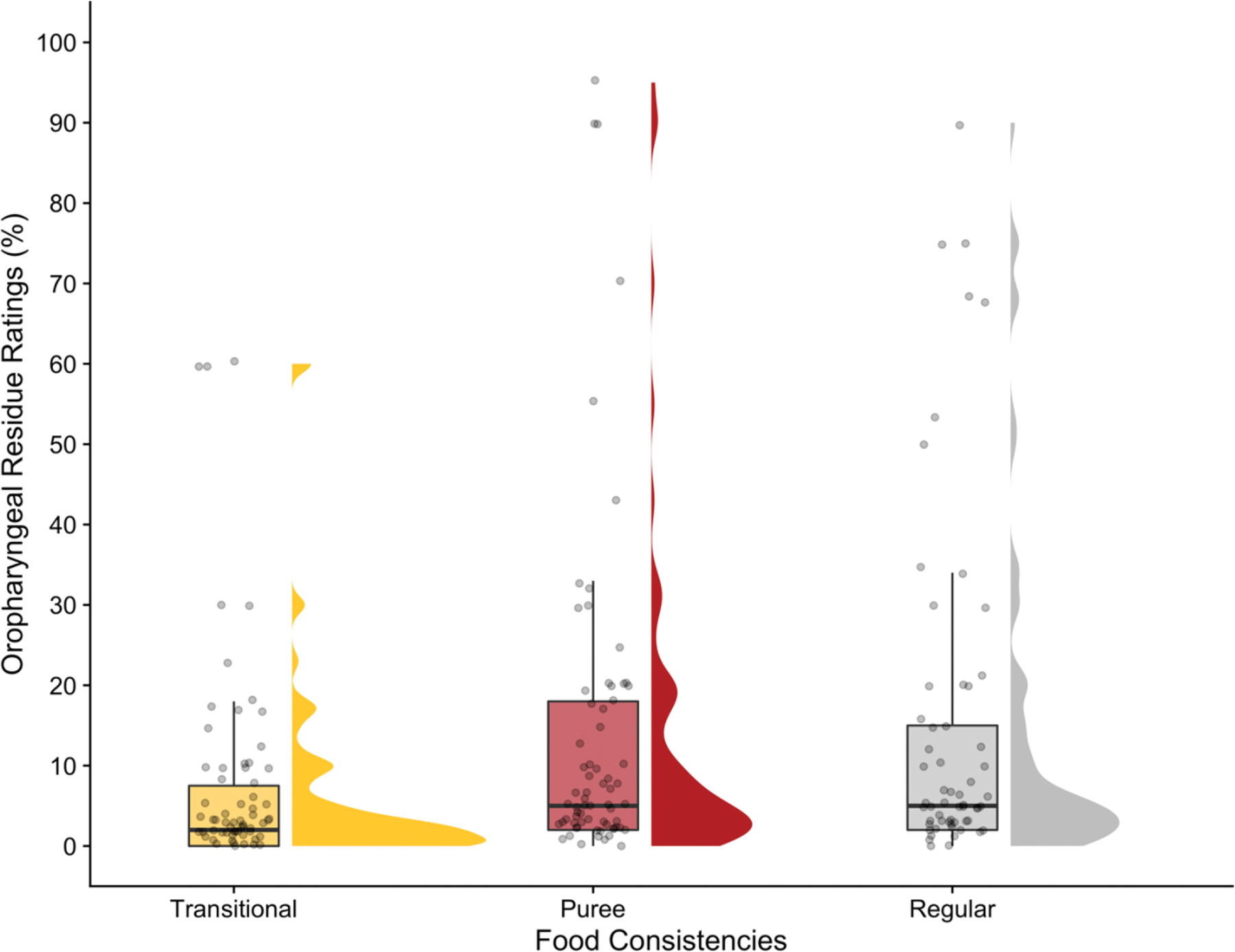

Pureed foods were more likely to have a greater number of swallows (p = .011; O.R. = 2.60; CI = 1.24 – 5.43; Figure 2, Table 2), and more oropharyngeal (p < .001; O.R. = 2.30; CI = 1.70 – 3.12; Figure 3, Table 3), hypopharyngeal (p < .001; O.R. = 2.37; CI = 1.75 – 3.21; Figure 4, Table 3), and epiglottic (p = .004; O.R. = 1.62; CI = 1.17 – 2.25; Figure 5, Table 3) residue when compared to transitional foods.

Figure 2:

Differences in the frequency of number of swallows completed within the ‘during the swallow’ temporal phase across transitional (left), pureed (middle), and regular (right) food textures.

Table 2:

Differences in Number of Swallows Across Foods

| Predictors | Number of Swallows | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratios | CI | p | |

|

| |||

| Pureed Foods (compared to Transitional Foods) | 2.60 | 1.24 – 5.43 | 0.011 |

| Regular Foods (compared to Transitional foods) | 0.67 | 0.30 – 1.48 | 0.319 |

| Random Effects | |||

| σ2 | 3.29 | ||

| τ00 study_id | 3.06 | ||

| ICC | 0.48 | ||

| N study_id | 39 | ||

| Observations | 217 | ||

|

| |||

| Marginal R2 / Conditional R2 | 0.048 / 0.507 | ||

Note: The reference group for all comparisons is Transitional Foods

Figure 3:

Raincloud plots depicting the distribution of oropharyngeal residue ratings (%) across transitional (left), pureed (middle), and regular (right) food textures.

Table 3:

Residue Ratings

| Predictors | Oropharyngeal Residue | Hypopharyngeal Residue | Epiglottis Residue | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p | Estimates | CI | p | |

|

| |||||||||

| Pureed Food (compared to Transitional Foods) | 2.3 | 1.70–3.12 | <0.001 | 2.37 | 1.75–3.21 | <0.001 | 1.62 | 1.17–2.25 | 0.004 |

| Regular Food (compared to Transitional Foods) | 2.25 | 1.66–3.06 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 0.94–1.77 | 0.115 | 1.43 | 1.02–2.00 | 0.039 |

|

N study_id = 39; Observations = 216 | |||||||||

Note: The reference group for all comparisons is Transitional Foods

Figure 4:

Raincloud plots depicting the distribution of hypopharyngeal residue ratings (%) across transitional (left), pureed (middle), and regular (right) food textures.

Figure 5:

Raincloud plots depicting the distribution of epiglottic residue ratings (%) across transitional (left), pureed (middle), and regular (right) food textures.

Regular foods were more likely to have more oropharyngeal (p < .001; O.R. = 2.25; CI = 1.66 – 3.06; Figure 3, Table 3) and epiglottic (p = .039; O.R. = 1.43; CI = 1.02 – 2.00; Figure 5, Table 3) residue when compared to transitional foods.

No other statistically significant differences were observed between transitional foods and either pureed or regular foods.

Aim 2: Differences Swallowing Safety Across Transitional, Pureed, and Regular Foods

Descriptively, all 78 transitional food trials (100%) had a PAS 1 (no penetration or aspiration). Of the pureed food trials, 71 (97%) had a PAS 1, one (1.4%) had a PAS 3 (penetration into the laryngeal vestibule), and one (1.4%) had a PAS 5 (penetration to the vocal folds). Of the regular food trials, 61 (94%) had a PAS 1, three (4.6%) had a PAS 3, and one (1.5%) had a PAS 5. Due to the limited variability in PAS scores, the planned inferential statistics could not be validly performed.

Discussion

This is the first study to explore the effects of transitional foods on swallowing efficiency and safety in outpatient dysphagic adults during FEES. This exploratory study revealed transitional foods appear to facilitate greater pharyngeal swallowing efficiency (less pharyngeal residue) when compared to both pureed and regular food textures. Therefore, transitional foods may be beneficial as part of an adult outpatient FEES protocol when considering DTM recommendations and therapeutic planning, as transitional foods could prove to be additional food category for adult patients with oropharyngeal swallowing dysfunction.

This study focused on pharyngeal swallowing safety and efficiency; two instrumental swallowing assessment outcome measures typically evaluated in routine clinical care. In alignment with our hypothesis, transitional foods had better swallowing efficiency outcome compared to solid texture. In contrast with our hypothesis, they exhibited greater swallowing efficiency compared to puree texture. While we did not compare pureed and regular foods to each other, it is interesting to note that descriptively, solid foods demonstrated less severe ratings of pharyngeal residue than pureed foods in this patient cohort. The reasons for variations in pharyngeal residue across different food types are not fully understood but may be further influenced by principles of food science and oral processing. Bolus characteristics, including cohesion, viscosity, adhesiveness, and brittleness may interact to impact oral processing, oropharyngeal swallowing dynamics, and thereby pharyngeal residue. For instance, non-cohesive texture of low-viscosity purees, such as applesauce, may spread easily and not form a cohesive bolus in the oral cavity compared to transitional or solid foods. In contrast, transitional foods may form a more cohesive bolus due to the initial solid-like texture, which may facilitate bolus transport through the oropharynx during the melting process to puree.

There is a paucity of research in the dysphagia literature on food oral processing. A single review to date incorporates the IDDSI framework in the study of oral processing 36. The food science disciplines of oral tribology and rheology may augment our understanding of DTM for in the management of oropharyngeal swallowing dysfunction. Oral tribology investigates the intricate interactions between food and the oral cavity, encompassing elements like lubrication and sensory perception during the swallowing process 37. Rheology delves into the flow and deformation of materials, including how food consistency affects ease of oral transport and swallowing. Food science demonstrates that oral processing goes beyond merely consuming and digesting food; it also plays a crucial role in enhancing our enjoyment of various food textures and flavors (Chen, 2009). Scientists in oral tribology and rheology are increasingly contributing to the development DTM foods tailored to the needs of individuals with dysphagia. For instance, studies have explored the bolus rheological properties in triggering swallowing as well as rheological properties of a fluid on perceived ease of swallowing 38,39.

Our study has several limitations. First, the food types used in this study were presented in a fixed (non-randomized) order according to the standardized protocol of our multidisciplinary dysphagia practice which could have resulted in an order effect. Future research should consider presenting food textures in a randomized order. Second, this study included only one type of transitional, pureed, and regular food – which could impact the generalizability of the findings to different food types within the same IDDSI levels. Future research should compare different types of foods, potentially including other types of puree foods (e.g., pudding), transitional foods (e.g., rice puffs), and chewable solid foods (e.g., saltine crackers). Third, this was a retrospective review of standard of care FEES with a standard protocol consisting of self-selected teaspoons of applesauce and self-selected bites of cracker. Therefore, bolus volumes may not have been matched by mass across the pureed, transitional, and solid food trials which could impact generalizability of findings. For example, if larger bites were routinely taken for one type of food (e.g., applesauce) compared to others (e.g., cracker), it is unknown how pharyngeal residue, penetration, and aspiration may have differed. Therefore, future research should consider expanding on the present study by matching foods by mass to examine if/how findings change. Fourth, food coloring was added to only one of the three food textures, which could have also altered the outcome measures in this study – though the effects of colorants on solid food-related outcome measures during FEES is unknown. Despite these limitations, our study highlights an area of investigative deficiency and the need for further studies incorporating food science principles of DTM to our examination of swallowing efficiency and safety.

Conclusions

This study revealed that transitional foods appear to facilitate greater pharyngeal swallowing efficiency when compared to pureed and regular solid food textures, suggesting this may be a valuable food texture to consider evaluating in patients with swallowing dysfunction. Effects of transitional foods on swallowing safety could not be formally examined given the limited number of airway invasion events across the three food types in this study. Future research should compare other puree and solid food textures to other types of transitional foods and explore the interaction between food textures and other oral preparatory factors on measures of swallowing safety and efficiency.

Funding

Anaïs Rameau was supported by a Paul B. Beeson Emerging Leaders Career Development Award in Aging (K76 AG079040) from the National Institute on Aging and by the Bridge2AI award (OT2 OD032720) from the NIH Common Fund.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Anaïs Rameau owns equity of Perceptron Health, Inc. Anaïs Rameau is a medical advisor for SoundHealth Inc. and Pentax Medical. Reva Barewal is the owner and CEO of Savorease Therapeutic Foods, Inc.

Ethical Review: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Weill Cornell Medicine (IRB #: 22–07025080).

Meeting: This study was presented as a poster at the annual Dysphagia Research Society meeting, San Francisco, CA, in March 2023.

Level of Evidence: IV– Retrospective cohort study

References

- 1.ASHA Diet Texture Modifications for Dysphagia. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Accessed November 17, 2024. https://www.asha.org/slp/clinical/dysphagia/dysphagia-diets/

- 2.Beck AM, Kjaersgaard A, Hansen T, Poulsen I. Systematic review and evidence based recommendations on texture modified foods and thickened liquids for adults (above 17 years) with oropharyngeal dysphagia – An updated clinical guideline. Clinical Nutrition. 2018;37(6, Part A):1980–1991. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cichero JAY, Steele C, Duivestein J, et al. The Need for International Terminology and Definitions for Texture-Modified Foods and Thickened Liquids Used in Dysphagia Management: Foundations of a Global Initiative. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep. 2013;1(4):280–291. doi: 10.1007/s40141-013-0024-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Namasivayam-Macdonald AM, Steele CM, Carrier N, Lengyel C, Keller HH. The Relationship between Texture-Modified Diets, Mealtime Duration, and Dysphagia Risk in Long-Term Care. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research. 2019;80(3):122–126. doi: 10.3148/cjdpr-2019-004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Logemann JA. Noninvasive approaches to deglutitive aspiration. Dysphagia. 1993;8(4):331–333. doi: 10.1007/BF01321772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clavé P, De Kraa M, Arreola V, et al. The effect of bolus viscosity on swallowing function in neurogenic dysphagia. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2006;24(9):1385–1394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03118.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inamoto Y, Saitoh E, Okada S, et al. The effect of bolus viscosity on laryngeal closure in swallowing: kinematic analysis using 320-row area detector CT. Dysphagia. 2013;28(1):33–42. doi: 10.1007/s00455-012-9410-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peña-Chávez RE, Schaen-Heacock NE, Hitchcock ME, et al. Effects of Food and Liquid Properties on Swallowing Physiology and Function in Adults. Dysphagia. 2023;38(3):785–817. doi: 10.1007/s00455-022-10525-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rofes L, Arreola V, Mukherjee R, Swanson J, Clavé P. The effects of a xanthan gum-based thickener on the swallowing function of patients with dysphagia. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2014;39(10):1169–1179. doi: 10.1111/apt.12696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masuda H, Ueha R, Sato T, et al. Risk Factors for Aspiration Pneumonia After Receiving Liquid-Thickening Recommendations. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2022;167(1). doi: 10.1177/01945998211049114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wirth R, Dziewas R, Beck AM, et al. Oropharyngeal dysphagia in older persons – from pathophysiology to adequate intervention: a review and summary of an international expert meeting. CIA. 2016;11:189–208. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S97481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steele CM, Namasivayam-MacDonald AM, Guida BT, et al. Creation and Initial Validation of the International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative Functional Diet Scale. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2018;99(5):934–944. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cichero JAY, Lam P, Steele CM, et al. Development of International Terminology and Definitions for Texture-Modified Foods and Thickened Fluids Used in Dysphagia Management: The IDDSI Framework. Dysphagia. 2017;32(2):293–314. doi: 10.1007/s00455-016-9758-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barewal R, Shune S, Ball J, Kosty D. A Comparison of Behavior of Transitional-State Foods Under Varying Oral Conditions. Dysphagia. 2021;36(2):316–324. doi: 10.1007/s00455-020-10135-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Complete IDDSI Framework Detailed definitions, 2019. Accessed March 23, 2025. https://www.iddsi.org/images/Publications-Resources/DetailedDefnTestMethods/English/V2DetailedDefnEnglish31july2019.pdf

- 16.Steele CM, Alsanei WA, Ayanikalath S, et al. The Influence of Food Texture and Liquid Consistency Modification on Swallowing Physiology and Function: A Systematic Review. Dysphagia. 2015;30(1):2–26. doi: 10.1007/s00455-014-9578-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayne D, Barewal Reva, and Shune SE Sensory-Enhanced, Fortified Snacks for Improved Nutritional Intake Among Nursing Home Residents. Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2022;41(1):92–101. doi: 10.1080/21551197.2022.2025971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruno E, Barewal R, Shune S. In Vivo Behavior of Transitional Foods as Compared to Purees: A Videofluoroscopic Analysis. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. doi: 10.1044/2025_AJSLP-24-00099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butler SG, Stuart A, Markley L, Rees C. Penetration and aspiration in healthy older adults as assessed during endoscopic evaluation of swallowing. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2009;118(3):190–198. doi: 10.1177/000348940911800306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butler SG, Stuart A, Markley L, Feng X, Kritchevsky SB. Aspiration as a Function of Age, Sex, Liquid Type, Bolus Volume, and Bolus Delivery Across the Healthy Adult Life Span. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2018;127(1):21–32. doi: 10.1177/0003489417742161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marvin S, Gustafson S, Thibeault S. Detecting Aspiration and Penetration Using FEES With and Without Food Dye. Dysphagia. 2016;31(4):498–504. doi: 10.1007/s00455-016-9703-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtis J, Perry S, Troche MS. Detection of Airway Invasion During Flexible Endoscopic Evaluations of Swallowing: Comparing Barium, Blue Dye, and Green Dye. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2019;28(2):515–520. doi: 10.1044/2018_AJSLP-18-0119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curtis JA, Seikaly ZN, Dakin AE, Troche MS. Detection of Aspiration, Penetration, and Pharyngeal Residue During Flexible Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES): Comparing the Effects of Color, Coating, and Opacity. Dysphagia. 2021;36(2):207–215. doi: 10.1007/s00455-020-10131-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis JA. A Scoping Review and Tutorial for Developing Standardized and Transparent Protocols for Flexible Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups. 2022;7(6):1960–1971. doi: 10.1044/2022_PERSP-22-00118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curtis JA, Rameau A, Mocchetti V. Effects of Puree Type and Color on Ratings of Pharyngeal Residue, Penetration, and Aspiration during FEES: A Prospective Study of 37 Dysphagic Outpatient Adults. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica. Published online November 19, 2024:1–16. doi: 10.1159/000542227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crary MA, Mann GDC, Groher ME. Initial Psychometric Assessment of a Functional Oral Intake Scale for Dysphagia in Stroke Patients. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2005;86(8):1516–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.11.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belafsky PC, Mouadeb DA, Rees CJ, et al. Validity and Reliability of the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10). Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(12):919–924. doi: 10.1177/000348940811701210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray J, Langmore SE, Ginsberg S, Dostie A. The significance of accumulated oropharyngeal secretions and swallowing frequency in predicting aspiration. Dysphagia. 1996;11(2):99–103. doi: 10.1007/BF00417898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenbek JC, Robbins JA, Roecker EB, Coyle JL, Wood JL. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1996;11(2):93–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00417897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Dea MB, Langmore SE, Krisciunas GP, et al. Effect of Lidocaine on Swallowing During FEES in Patients With Dysphagia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;124(7):537–544. doi: 10.1177/0003489415570935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curtis JA, Borders JC, Perry SE, Dakin AE, Seikaly ZN, Troche MS. Visual Analysis of Swallowing Efficiency and Safety (VASES): A Standardized Approach to Rating Pharyngeal Residue, Penetration, and Aspiration During FEES. Dysphagia. 2022;37(2):417–435. doi: 10.1007/s00455-021-10293-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curtis JA, Borders JC, Troche MS. Visual Analysis of Swallowing Efficiency and Safety (VASES): Establishing Criterion-Referenced Validity and Concurrent Validity. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2022;31(2):808–818. doi: 10.1044/2021_AJSLP-21-00116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenbek JC, Robbins J, Roecker EB, Coyle JL, Wood JL. A penetration-aspiration scale. Dysphagia. 1996;11(2):93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Published online 2021. https://www.R-project.org/

- 35.Steele CM, Grace-Martin K. Reflections on clinical and statistical use of the Penetration-Aspiration Scale. Dysphagia. 2017;32:601–616. doi: 10.1007/s00455-017-9809-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cichero JAY. Evaluating chewing function: Expanding the dysphagia field using food oral processing and the IDDSI framework. Journal of Texture Studies. 2020;51(1):56–66. doi: 10.1111/jtxs.12462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shewan HM, Pradal C, Stokes JR. Tribology and its growing use toward the study of food oral processing and sensory perception. J Texture Stud. 2020;51(1):7–22. doi: 10.1111/jtxs.12452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen J, Lolivret L. The determining role of bolus rheology in triggering a swallowing. Food Hydrocolloids. 2011;25(3):325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.06.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nyström M, Qazi WM, Bülow M, Ekberg O, Stading M. Effects of Rheological Factors on Perceived Ease of Swallowing. Applied Rheology. 2015;25(6):9–17. doi: 10.3933/applrheol-25-63876 [DOI] [Google Scholar]