Abstract

Sesame (Sesamum indicum) is a major oilseed crop known for its substantial amount of natural antioxidants. Lignan is believed to be the primary attribute for the antioxidant properties of sesame. However, information related to lignans in sesame oils are still deficient and little is known about enzymes involved in conversion of sesamin to sesamolin and from piperitol to sesamolinol. In this study, we used metabolomic (targeted LC-MS) and transcriptome (RNA-Seq) analyses to identify metabolites and key genes associated with lignan production during the young stage (YS) and matured stages (MS) of Sesame seed. The contents of 7 lignan type metabolites and expression of 83 unigenes involved in the lignan pathway differed considerably between YS and MS; 6 of metabolites were only detected at MS while no sesamol is detected in both stages. Similar to metabolite analysis output in RNA Seq analysis majority of genes in lignan biosynthesis pathway were upregulated at MS. These findings will enhance our knowledge of lignan biosynthesis in seeds and provide a foundation for molecular breeding in sesame.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-025-07476-9.

Keywords: Sesame, Lignans, Sesamin, Sesamolin, Seed maturation, Transcriptomics, Metabolomics

Introduction

Sesame (Pedaliaceae, Sesamum indicum L.), a major oilseed crop with high nutritional value, is widely cultivated worldwide. Sesame oil, which makes up 50% of the seed’s weight, contains a substantial amount of natural antioxidants. The potent antioxidant properties of sesame seed extract can be primarily attributed to the presence of lignans [1, 2] and widely distributed across vascular plants [3]. Many scientific studies verify that plants are excellent sources of valuable bioactive compounds, and Phytotherapy represents a promising future development with a wide range of potential applications [4–6].

Lignans are a vital group of bioactive plant compounds utilized in traditional medical systems worldwide [7]. Plants that are sources of lignans have been used as folk remedies in traditional Chinese, Japanese, and Eastern world medicine for at least 1,000 years [8]. Numerous biological activities in lignans have been scientifically proven, making them of therapeutic interest. These activities include immunomodulatory effects, impacts on the cardiovascular system, anti-leishmanial properties, hypolipemic effects, and anti-inflammatory, antifungal, and anti-rheumatic properties [8–11]. Lignans can be isolated from various plant parts, including leaves, stems, roots, rhizomes, seeds, and fruits [12].

The oil from sesame seeds is a rich source of unsaturated fatty acids as well as lignans, which are plant-derived phenylpropanoid dimers chemically known as monolignol dimers [13]. Lignan is produced by dimerizing the lignan backbone coniferyl alcohol, into various intermediates followed by post-dimerization transformations such as methylation, oxidation, demethylation, cyclization, hydrolysis, and/or hydroxylation [14], which produces pinoresinol. Coniferyl alcohol molecule is the primary intermediate that leads to the formation of various classes of lignans [7]. (+)-Sesamin, (+)-sesamolin, and (+)-sesaminol glucosides are the primary lignans found in sesame seeds. Further high level of lignan glucoside mainly sesaminol triglucoside found by [15, 16]. The top lignan metabolites of sesame such as Sesamin (77–930), Sesamolin (61–530), Sesaminol (0.3–1.4), Sesamolinol [6–28], Sesaminol Triglucoside [14–90],Sesaminol Diglucoside (8.2–18.3), Sesaminol Monoglucoside (5.4–19.5) in mg/100 seed were presented by [17]. These compounds have gained attention for their health-promoting properties [18]. Apart from genetic and environmental factors maturity stage of seed and fruit significantly alter the content and composition of lignans [19]. Lignan content reported to be influenced by seed developmental stages in flaxseed [20], Schisandra chinensis [21], and H. pedunculosum [22].

Sesame oil stands out as the most stable among all edible oils, primarily because of the antioxidant properties of its lignans. This has sparked interest in utilizing sesame lignans to enhance the shelf life of other edible oils. CYP81Q1, identified as the sesamin synthase by [2], is a P450 monooxygenase that catalyzes the dual methylenedioxy bridge formation converting pinoresinol to sesamin in Sesamum indicum seeds, with ER localization and expression correlating with seed maturation. Varietal variation to sesamin and sesamolin [23], sesamin and sesamol [24–26] were reported. Information related to lignans in sesame oils are still deficient [27] and little is known about enzymes involved in conversion of sesamin to sesamolin and from piperitol to sesamolinol [28, 29]. Despite extensive studies of individual genes, metabolites, and varietal differences in sesame seed lignan biosynthesis, no published work achieves true multi-omics integration necessary to reveal comprehensive regulatory mechanisms during seed development. Transcriptomics and metabolomics have been extensively used in recent years to screen genes and metabolites involved in lignan biosynthesis [30–33].

In sesame, CYP81Q1, CYP92B14, and specific UGTs such as UGT71A9 have been identified as key enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of sesamin and sesamolin [2]. Prior research in several plant species underscores the developmental regulation of lignan production. For instance, in flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum), the accumulation of secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) increases significantly during seed maturation [34]. In Schisandra chinensis, combined transcriptome and metabolomic investigations demonstrated that lignan biosynthetic genes exhibit differential expression during fruit development, corresponding with variations in lignan concentration [35, 36]. Similarly, in Forsythia spp., developmental and tissue-specific variations in lignan accumulation, such as matairesinol, have been observed [37]. Collectively, these findings highlight the conserved yet species-specific nature of lignan pathway regulation and support the relevance of developmental stage-specific analysis in sesame.

The present study expands on existing knowledge by providing a comprehensive metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis of sesame seed development stages, which has not been previously detailed. Using integrative analysis of the transcriptome and metabolome, this study examined the differences in sesame lignans and the expression patterns of key genes involved in lignan biosynthesis during maturation. The six lignan metabolite of sesame selected for the present study were based on their biological relevance and reported abundance in sesame. Among these lignan metabolites in most previous studies gene expression study were carried for sesamin and sesamolin. The findings will allow us to better understand the synthesis of lignans in seeds and provide insights into the metabolic engineering of lignans in Sesamum indicum.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth condition

For this study a variety called Ado were selected, that was provided by Werer Agricultural research center, Ethiopia. The Sesamum indicum accession selected was known for its high oil content, making it an ideal candidate for studying the biosynthesis pathways as a strong synergistic effect among Oil and Lignan reported in a study conducted by [38]. It demonstrated a growth duration of around 110 days, producing 12.92 quintals per hectare with irrigation and 9.43 quintals per hectare under rain fed conditions, with oil content varying from 51% to 55.14% [39, 40]. Germination and growth were carried out in plastic pots under controlled room conditions, with temperatures set to 26 °C during the day and 22 °C at night, 75% relative humidity, a 16-hour photoperiod, and a light intensity of 175 µmol/(m²·s⁻¹).

Metabolomic analysis

Lignan analysis by the LC-MS/MS

Distilled water was further purified by an Arium Pro ultrapure water system (Sartorius, Germany). LC-MS grade methanol was employed (Th. Geyer, Germany), all eluents were acidified with 0.1% formic acid in LC-MS grade (Merck, Germany). 1,3-Benzodioxole, Sesamin, Sesamolin, Sesamol, Pinoresinol and Pinoresinol diglucoside were obtained from Merck (Germany), Sesaminol, Sesaminol di- and triglucoside from GEBRU (Germany) and Piperitol from ChemFaches (Wuhan, China). 1000 mg/l stock solutions in DMSO were prepared and stored at −20 °C. Dilutions were made in 50% MeOH.

UV-vis and high-resolution fragmentation data

UV- and MS-fragmentation spectra were recorded on an LC-Q-TOF instrument employing an Agilent 1290 Infinity II LC system equipped with a DAD-detector coupled to an Agilent 6545 Q-TOF. Pure standards were used, but still, chromatography was performed to minimize the possibility of interferences. A short gradient with water and methanol, both acidified with 0.1% formic acid, on an Agilent Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.8 μm particle size) was run. A linear gradient from 5 to 95% methanol in 4 min was run, 95% MeOH were hold for 0.5 min and the column was re-equilibrated for 4.5 min. The flow rate was set to 0.4 mL/min, the column was heated to 35 °C and 2 µL were injected.

DAD spectra from 190 to 400 nm were recorded. Q-TOF data for every compound were generated in positive and negative ionization mode, the collision energies were optimized in several runs and the best spectra were selected. The Q-TOF had a Jetstream source, the sheath gas temperature was set to 350 °C and the flow to 11 l/min. The N2 temperature was set to 320 °C, with a flow of 8 l/min and a nebulizer pressure of 35 psig. The voltages were set as follows: Nozzle voltage 1000 V, capillary voltage 3500 V, fragmentor 175 V and skimmer 65 V. 3 TOF spectra per second were acquired in MS1 mode from 100 to 1700 m/z and 3 spectra in MS2 mode from 20 to 1000 m/z. Data evaluation was performed in MassHunter B.0.8.00, MassHunter Molecular Structure Correlator B.0.8.00 and R studio 1.2.1335. Structural formulas were drawn in ChemSketch 2018.2.5.

HPLC- triple-quadrupole method

A Phenomenex Synergi Hydro RP column, 50 × 2 mm with 2.5 μm particle size was employed. A linear gradient from 5 to 98% methanol in 10 min was run, 98% MeOH were hold for 1.5 min and the column was equilibrated for 5 min. 10 µl were injected and the flow rate was set to 200 µl/min. The column oven temperature was set to 40 °C. An Agilent 1290 Infinity II LC system was coupled to an Agilent 6460 triple quadrupole. It was measured in multiple reaction monitoring mode and the source parameters were as follows: N2 temperature 350 °C, gas flow 13 l/min, nebulizer pressure 60 psig, and capillary voltage 4000 V. These settings apply for the positive and the negative ionization mode. The mass transitions can be found in Accumulation differences in lignan during sesame seed development section. Data evaluation was performed in MassHunter B.0.8.00.

Limits of detection (LOD) and limits of quantification (LOQ) for this method were estimated according to the Guidance document on the estimation of LOD and LOQ for measurements in the field of contaminants in feed and food [33], a calibration curve with four standards between 1 and 50 µg/l was set up, each dilution was measured 10 times plus 10 solvent blanks. The LODs were calculated according to the formulas given below. If the signals in the solvent blanks were close to zero and did not allow to observe the full signal distribution, very low-level spikes between 0.5 and 1 µg/l were used instead (pseudo-blanks).

|

|

Where, Sy = standard deviation of blanks or pseudo-blanks.

b = slope of the calibration curve, highest point does not exceed LOQ more than ten-fold.

Extraction of lignan

A previous study conducted by [2] and our HPLC analysis in the present study revealed two distinct patterns of metabolite accumulation throughout the stages of sesame seed development. We collected samples for metabolite quantification and RNA-Seq analysis at two key stages. The first stage involved sampling when the seed pods were 1.5 to 2.5 cm in length, while the second stage was when the seeds had fully matured, turned brown, and grown longer than 2.5 cm. Extraction of lignans was performed in 80% ethanol and quantification of lignans was done from the harvested seeds in three biological replicates of individually grown plants. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis was performed using an Agilent 1290 Infinity II HPLC (Agilent Technologies, California, United States) coupled with an Agilent 6460 triple quadrupole system. A Phenomenex Synergi Hydro RP column, 50 × 2 mm with 2.5 μm particle size was employed. A linear gradient from 5 to 98% methanol in 10 min was run, 98% MeOH were hold for 1.5 min and the column was equilibrated for 5 min. 10 µl were injected and the flow rate was set to 200 µl/min. The column oven temperature was set to 40 °C. It was measured in multiple reaction monitoring mode and the source parameters were as follows: N2 temperature 350 °C, gas flow 13 l/min, nebulizer pressure 60 psig, and capillary voltage 4000 V. These settings apply for the positive and the negative ionization mode. Data evaluation was performed in MassHunter B.0.8.00.

Transcriptome sequencing and data processing

RNA isolation and sequencing

RNA extraction and sequencing were carried as described in our previous study (Bekele et al. 2024). Briefly, RNA from young and matured stage of seed were extracted using the TRIzol Reagent kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quantity and quality were evaluated with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), and by running a 1% agarose gel. For cDNA synthesis and library preparation, one microgram of RNA with a RIN value above 7, indicating high integrity, was used. The mRNA was isolated and purified using oligo(dT)-rich magnetic beads, then processed into RNA-seq libraries with an insert size between 200 and 300 bp using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina). Libraries were indexed, multiplexed, and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with a 1 × 150 bp single-end configuration. Image analysis and base calling were performed with the HiSeq Control Software (HCS) + OLB + GAPipeline-1.6 (Illumina).

RNA-seq libraries, each with an insert size of 200–300 bp, were prepared and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform using single-end (SE) reads of 100 bp. Analyses were conducted on RNA samples with integrity numbers (RIN) of ≥ 7. Sequence reads for each sample were filtered using Trim Galore (version 0.0.6) with cutadapt version 3.0 and Python 3.6.9. Adapter sequences, polyA tails, and low-quality ends were trimmed, and reads shorter than 30 nucleotides were excluded. The cleaned reads were then mapped to the Sesamum indicum reference genome (release-59), obtained from the Ensembl repository, using HISAT2 version 2.1.0. Reads with a mapping quality score of Q ≥ 20 were assigned to the ‘gene’ feature in the corresponding GFF3 file using feature Counts. Sequencing depth per sample was estimated using the total number of sequenced reads, a read length of 75 bp (single-end), and an assumed Sesamum indicum transcriptome size of 30 Mb. The calculated sequencing depth ranged from approximately 118× to 152× across samples.

Functional annotation of unigenes

In order to investigate the functional roles of assembled unigenes, we performed similarity searches using public protein databases, including KEGG. Following the methodology described by [41], enzyme codes (ECs) were identified based on homologous gene functions annotated through Gene Ontology (GO) terms. InterProScan was then used to predict conserved domains and motifs within the protein sequences. Subsequently, we conducted functional enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using the GO and KEGG databases to explore the biological processes and metabolic pathways in which these genes are involved. This analysis enabled the identification of key pathways and functional categories associated with lignan biosynthesis and seed development.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

To verify the accuracy of gene expression levels in the transcriptome data, we randomly selected six genes from the identified lignan biosynthesis, Triacylglycerol (TAG) biosynthesis, and oil biosynthesis related genes for qRT-PCR analysis, with Actin as the internal reference. Specific primers for qRT-PCR were designed using Primer software (Table 1). Reactions were conducted according to the manufactures’ instructions. Amplification proceeded as follows: pre-denaturation at 95 ◦C for 5 min, 40 cycles at 95 ◦C for 15 s, annealing at 60 ◦C for 40 s. Dissolution curves were recorded from 60 ◦C to 95 ◦C, with a 0.5 ◦C increase every 5 s. Each sample from both steps had three biological replicates. The quantification of gene expression was established using the relative standard curve method and normalized to the housekeeping gene using the 2−∆∆Cq method [42].

Table 1.

Gene and primers used for qRT-PCR

| Genes | Primer pairs | Tm value |

|---|---|---|

| 0Actin | 5’- ATGGAAGCTGCAGGCATTCA-3’ | 58.3 |

| 5’- TGATGCTAGGATTCACCTCC-3’ | 58.5 | |

| SIN_1010113 | 5’-GCACTTCACGCTGTCTTGTG-3’ | 60 |

| 5’- TCAATCCCAACACCAGCCTC-3’ | 60 | |

| SIN1010817 | 5’- CTCCTCCCGAACTCTCCTGA-3’ | 60.1 |

| 5’-ATCGGTGCACCAACTCTGAG-3’ | 60.4 | |

| SIN_1003362 | 5’- CCTCATTCGGGAGCGAGTAC-3’ | 59.5 |

| 5’- CGTCACCAATTCCTCCACCA-3’ | 60.1 | |

| SIN_1022640 | 5’- ATTGATTGGAGCACCCCCTG-3’ | 58.5 |

| 5’- ACCCTCTTCTCGAGCCATCT-3’ | 58.4 | |

| SIN_1022131 | 5’- CGGCGAAAGTCTTGCTTACG-3’ | 59.9 |

| 5’- ACGTTCGCCAGCATTGTAGA-3’ | 60 | |

| SIN_1010690 | 5’-TAGAAGGGCTGGAGTAGAACAC-3’ | 60.2 |

| 5’-TCCGCCAACTCTCAACAATTTT-3’ | 60.3 |

Data availability

The raw sequencing data generated and analyzed during this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1197728.

Result

Metabolomic profiling

The presence and retention time (t[min]) of key lignans in sesame seed extracts, chromatographic profiles were analyzed using LC-MS/MS. Figure 1 displays the extracted ion chromatograms of selected lignans in both absolute and normalized intensity formats. Panel A illustrates the absolute intensities of individual lignans across a retention time range of 4 to 10 min. Distinct peaks were observed for each lignan, confirming their separation and detection. Panel B shows the same chromatographic peaks after normalization of intensity to unity. This highlights peak shape, retention reproducibility, and separation clarity rather than abundance. It has been seen that the separation between structurally similar compounds such as sesamin, sesamolin, and piperitol was maintained.

Fig. 1.

Chromatogram of the investigated lignans from the Phenomenex column employed for the triple-quadrupole method. A Chromatogram; (B) Normalized chromatogram

As displayed in Fig. 1 chromatograms of the quantifiers used for the triple-quadrupole method on the Phenomenex column, the left side displays the original intensities of the 1 mg/l standards, while the right side displays the normalized chromatograms. Generally, the elution order is as it can be expected by taking into consideration the polarity of the monitored analytes. Glucosylation makes the molecules more hydrophilic and therefore, the glucons elute before the corresponding aglycons. A good separation is important even if a MS-detector is employed because of matrix interferences as lignans often show in-source-fragmentation. Because they share the same backbone, a mix-up could be possible, for example between sesaminol diglucoside, sesaminol triglucoside and sesaminol. Therefore, a compromise between a short analysis time and an acceptable separation has to be made.

High-resolution fragmentation data

A targeted LC-MS/MS method was optimized to quantify key lignans in sesame seeds, including pinoresinol, piperitol, sesamin, sesamolin, sesaminol, sesaminol glucosides, and sesamol. The analysis was performed in negative and positive electrospray ionization (ESI) modes, depending on the lignan’s ionization properties. Table 2 summarizes the MS/MS parameters used for each lignan, including their molecular and product ions, fragmentor voltages, collision energies, and the limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ). Each lignan was identified based on its specific parent ion and two product ions derived via collision-induced dissociation (CID). One of the product ions (marked with an asterisk) was selected as the quantifier ion, ensuring the reliability of quantitation.

Table 2.

The relevant triple-quadrupole method transitions for each Lignan including the corresponding limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) are listed. The quantifiers are marked with asterisks

| Lignan | Molecular ion | Parent ion | Fragmentor [V] | Collision Energy [V] | Product ions | LOD [µg/l] |

LOQ [µg/l] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinoresinol | [M-H]− | 357.1 | 120.0 |

15 22 |

151.1* 135.9 |

1.8 | 6.0 |

| Pinoresinol diglucoside | [M-digluc-OCH3].+ | 339.2 | 90.0 |

5 15 |

323.2 137.0* |

1.7 | 5.7 |

| Piperitol | [M + H]+ | 327.1 | 90.0 |

15 15 |

257.1* 243.0 |

0.2 | 0.6 |

| Sesamin | [M-OCH2].+ | 337.0 | 90.0 |

19 19 |

289.0 135.0* |

0.3 | 1.0 |

| Sesamolin | [M-C7H5O3].+ | 233.0 | 90.0 |

10 10 |

215.0* 187.1 |

1.4 | 4.7 |

| Sesaminol | [M-H]− | 369.1 | 125.0 |

20 15 |

339.9 219.2* |

0.04 | 0.13 |

| Sesaminol glucosides | [M-Gluc-O].+ | 353.1 | 110.0 |

10 10 |

335.2 185.2* |

(di)6.2 (tri) 2.9 |

(di)20.4 (tri) 9.6 |

| Sesamol | [M + H]+ | 139.0 | 90.0 |

10 27 |

108.8* 81.0 |

1.9 | 6.4 |

*Transition set as quantifier

To study the fragmentation behavior of the investigated lignans, the intact molecular ions ([M + H]+, [M + Na]+ or [M-H]−) were isolated in the collision cell, the collision energy was optimized for each precursor in several runs and the obtained Q-TOF spectra were evaluated. Sodium adducts were observed for all lignans in positive mode with varying relative intensities, but they never yielded any high-quality MS/MS spectra.

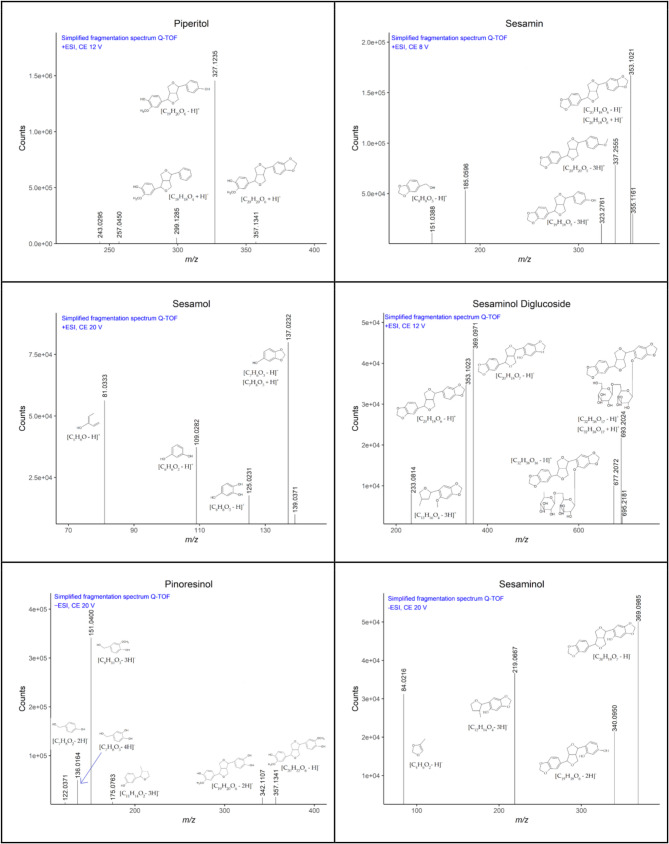

Figure 2 displays the fragmentation spectra of piperitol, sesamin and sesamol in positive ionization mode and several noteworthy observations can be made. Piperitol (collision energy 12 V) forms a high fragment ion corresponding to the cleavage of a CH2O group, this fragment is typical for bisepoxylignans, which has been described by [43]. The next smaller fragment results from the loss of an oxygen, respectively a hydroxyl group. Looking at sesamin (collision energy 8 V), the loss of an oxygen (m/z 337.2555) and the mentioned cleavage a CH2O group (m/z 323.2761) are observed. Moreover, a high peak at 353.1021 m/z is present and would fit to a [M-H]+ radical cation.

Fig. 2.

Fragmentation mass spectra by collision-induced dissociation (CID) of lignans in positive or negative ionization mode. The presented fragmentation mass spectra are the combination of fragmentation data acquired for collision energies between 8-20 eV

For instance, pinoresinol ([M-H]⁻, m/z 357.1) was fragmented using a 120 V fragmentor voltage and collision energies of 15 and 22 V, generating quantifier and qualifier ions at m/z 151.1* and 135.9, respectively. Similarly, sesamin ([M-OCH₃]⁻, m/z 337.0) produced major fragments at m/z 289.0 and 135.0*. A range of LOD 0.2 µg/L (piperitol) to 6.2 µg/L (sesaminol glucosides, diastereomer 1) and LOQ from 0.6 µg/L to 9.6 µg/L. These demonstrated that lignans in the present study has been identified even in the low concentration which is relevant for comparative profiling across developmental stages.

Sesaminol glucosides displayed diastereomer-specific quantification, with distinct LOD/LOQ values (e.g., diastereomer 1: LOD = 6.2 µg/L, LOQ = 2.9 µg/L; diastereomer 2: LOD = 0.4 µg/L, LOQ = 9.6 µg/L), reflecting subtle differences in ionization and fragmentation behavior.

As the details of the triple-quadrupole method presented in Table 2 and the raw spectra presented S, Fig. 1., for pinoresinol, piperitol, sesaminol and sesamol the precursors were the intact [M + H]+ or [M-H]− ions and the fragments are known from the Q-TOF. Pinoresinol diglucoside forms a prominent in-source fragment corresponding to the loss of the glucosides and the cleavage of a methoxygroup. Sesamolin is quantified after the cleavage of the ether group characteristic of sesamolin, this cleavage has been previously described and used for a MS/MS method by [43]. The glucosides of sesaminol are fragmented after the in-source loss of the glucoside units, the sensitivity is limited. The intact glucosides form only very low abundant hydrogen adducts in positive mode and are not ionized in negative mode. The most prominent m/z peaks of the intact molecules originate from sodium adducts, which often can hardly be fragmented due to their high stability.

The limits of detection and quantification for pure lignans are provided in Table 2. Depending on the sample type (seeds, roots, etc.), the extraction method and possible cleaning steps, the sample matrix varies and thus, the possible influence on the LODs and LOQs can be tested for the specific conditions in following works. However, for the purpose of selecting attractive sesame accessions and lignan profiling, trace level analysis in the area of LOQ is not relevant.

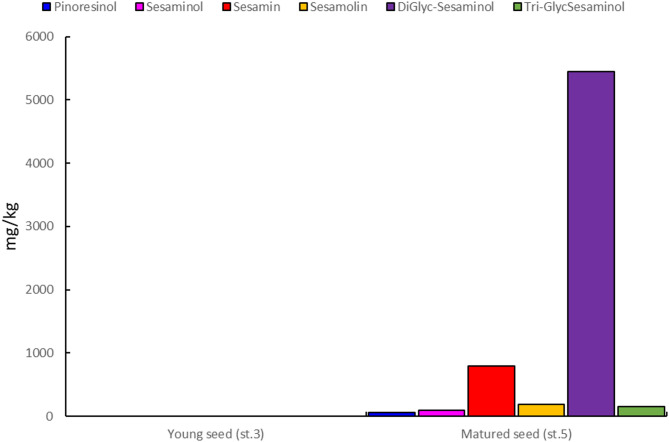

Accumulation differences in lignan during sesame seed development

In the present study lignan content of Sesamum indicum seeds during their different developmental stages were analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). For most of the lignans the highest concentration was found at stage five, which corresponds to the maturity level (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Lignans measured in sesame at the young and matured stage

Comparing the two developmental stages, the lignan concentration was low in stage three (young stage), while it peaked as the seeds get matured (Fig. 3). Similar results were reported previously by Ono et al. (2006) in sesame. Comparing the concentration of each types of lignans in sesame, highest concentration was detected for DiGlyc-Sesaminol (5447.7 mg/kg) followed by sesamin (192 mg/kg), Tri-GlycSesaminol (157 mg/kg), sesamolin (84.5 mg/kg), sesaminol (1.1 mg/kg), and pinoresinol (0.8 mg/kg) (Fig. 1). This study indicated that the biosynthesis of lignan is specific to certain stages of sesame development. Furthermore, the accumulation of lignans seems to follow a distinct regulatory pattern depending on the developmental stages.

Transcriptomic profiling

The detailed statistics of generated rna seq data is available in our previous published work [39] here we presented the brief summary statistics of RNA-Seq data sets (S.Table 2). The mapping results revealed that approximately 75.6% of YS reads and 80% of MS reads were successfully aligned to the sesame reference genome. Overall, the distribution of mapped reads across different genomic locations exhibited similar patterns between the two seed-stage samples.

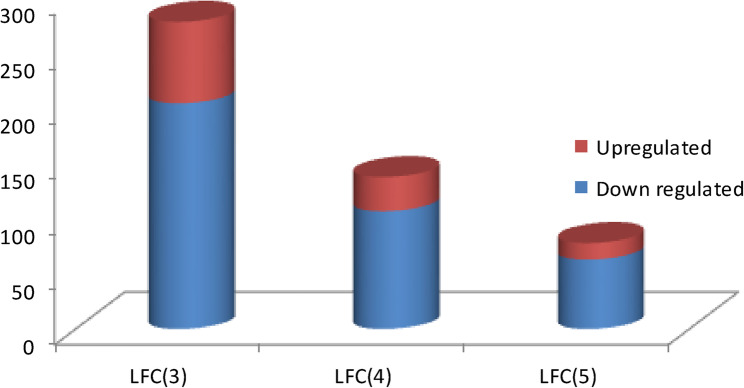

To identify the number of actively expressed genes in the sesame transcriptome, normalized CPM values (log2 scale) were used as expression metrics, and the number of transcripts expressed at each CPM threshold was calculated. With the young stage serving as the control, 205 genes were found to be upregulated, 18,541 non-significant, and 74 downregulated at an LFC (log fold change) of 3. Similarly, for LFC [4], 107 genes were upregulated, 18,682 genes were non-significant, and 31 genes were downregulated (Fig. 4). These highly expressed genes were shown to encode proteins belong to peptidase, protein transport, Glycosyltransferase, non-specific serine/threonine protein kinase. For further details readers can get the top 30 highly expressed genes with their description in our previously published article [39]. The fact that only 75–80% of the genes identified in the sesame reference genome were observed in our transcriptome analysis (RPKM >0.1) is likely a result of the tissue-specific sampling methods used in this study. Our transcriptome primarily targets genes expressed exclusively in developing seeds during young and mature stages, leading to the detection of fewer genes overall.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of higher LFC at each stages of seed development. LFC refers to Log fold changes

Gene ontology and KEGG pathway enrichment of transcriptomic data

To explore the overall gene expression patterns and emphasize the role of identified DEGs in lignan metabolism during sesame seed development, the DEGs were annotated and grouped into different GO categories. The GO classification results revealed that the DEGs participate in various biological processes and molecular functions within specific cellular compartments (Fig. 5). In the present study 7360 genes were assigned with at lest 1 GO term while 2446 genes found no BLAST hit in the Plant DB. We found that the majority of transcripts at matured stage encoded transferase activity, including those involved in aminoacyltransferase activity, ubiquitin-like protein transferase activity, ubiquitin-protein transferase activity (S.Table 1; Fig. 5). While at the early stage structural activity such as structural constituent of ribosome, structural molecule activity, microtubule motor activity and hydrolase activity.

Fig. 5.

Top enriched GO terms

Overall, the results indicate high and developmentally regulated levels of transcription observed for the candidate genes involved in monolignan biosynthesis (Fig. 6). Focusing on the molecular basis of lignan synthesis in sesame seeds, we assessed expression patterns of monolignan-encoding genes related to lignan metabolism. KEGG analysis identified 26 genes expressed during the young stage and 27 during the mature stage (CPM > 0.1), marking them as key participants in lignan metabolic pathways. On the other hand 30 unigenes were equally expressed at each stage equally. The unigenes encoding enzymes or proteins that play a crucial role in monolignol biosynthesis are presented as follows. Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) is responsible for catalyzing the conversion of phenylalanine to cinnamic acid. It was encoded by unigenes, including SIN_1005477, SIN_1004404, and SIN_1002445 (Fig. 7; Table 3).

Fig. 6.

Hierarchical Clustering Heatmap of Genes Involved in Lignan Biosynthesis in Sesame

Fig. 7.

Pathway depicting unigenes involved in monolignon biosynthesis. The expression abundance (LFC) for the identified candidate genes are highlighted in different color scales in sesame developing seeds at young stage (YS) and at matured stage (MS). The full name for the metabolites shown in the pathways is phenylalanine, Cinnamic acid. P-coumaric acid, p-coumaroyl coa, p-coumaroyl quinic acid, coniferyl alcohol, sinapyl alcohol, and p-coumaryl alcohol. The enzymes shown here are PAL (phenylalanine ammonia-lyase), (PTAL) phenylalanine/tyrosine ammonia-lyase, (CYP73A) trans-cinnamate 4-monooxygenase, (4CL) 4-coumarate–CoA ligase, (HCT) shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase, (CYP98A) 5-O-(4-coumaroyl)-D-quinate 3’-monooxygenase, caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase, (CYP84A)/(F5H) ferulate-5-hydroxylase, (COMT) caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase, (CCR) cinnamoyl-CoA reductase, (CAD) cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase. This model is modified from the phenaylpropanoid metabolism pathway in KEGG database http://www.genome.jp/kegg/

Table 3.

Enzymes/proteins related to biosynthesis of TAG

| Ko | Enzyme/protein | Genes | FDR | p-value | LFC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbr. | Full form | |||||

| K00083 | CAD | cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase | SIN_1021093 | 0.504056 | 0.554627 | −0.0676 |

| SIN_1014909 | 0.528932 | 0.5785145 | 0.0356 | |||

| SIN_1005782 | 0.000119 | 0.0002168 | −0.423 | |||

| K00487 | CYP73A | trans-cinnamate 4-monooxygenase | SIN_1023328 | 0.001351 | 0.002209 | −0.1492 |

| SIN_1007513 | 0.005405 | 0.0082511 | 0.1488 | |||

| SIN_1024388 | 2.50E-21 | 1.24E-20 | −0.9143 | |||

| SIN_1024387 | 6.02E-07 | 1.34E-06 | −0.4739 | |||

| SIN_1024386 | 7.00E-09 | 1.80E-08 | 0.2652 | |||

| K00588 | caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase | SIN_1007665 | 1.60E-132 | 6.43E-131 | 3.8655 | |

| SIN_1014884 | 0.001487 | 0.0024186 | −0.142 | |||

| SIN_1007664 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1026198 | 0.491596 | 0.5426941 | −0.0755 | |||

| SIN_1007673 | 7.98E-86 | 1.79E-84 | 2.7711 | |||

| SIN_1007674 | 0 | 0 | 3.6318 | |||

| SIN_1007663 | 5.62E-56 | 7.59E-55 | 2.4777 | |||

| K01904 | 4CL | 4-coumarate–CoA ligase | SIN_1026210 | 0.034508 | 0.0473077 | 0.2227 |

| SIN_1008068 | 3.45E-06 | 7.25E-06 | −0.6701 | |||

| SIN_1022003 | 7.64E-17 | 3.10E-16 | −0.8461 | |||

| SIN_1010817 | 4.94E-119 | 1.72E-117 | 1.6431 | |||

| SIN_1010914 | 0.559506 | 0.608343 | −0.0375 | |||

| SIN_1026519 | 0.993848 | 0.9993705 | 0.0054 | |||

| SIN_1009267 | 0.038554 | 0.0524612 | 0.1236 | |||

| SIN_1006084 | 0.00018 | 0.0003226 | −1.2896 | |||

| SIN_1006083 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1024601 | 0.692977 | 0.7337171 | 0.0238 | |||

| SIN_1023853 | 7.30E-265 | 7.23E-263 | −2.0135 | |||

| SIN_1004004 | 0.028508 | 0.0395019 | 0.1786 | |||

| K09753 | CCR | cinnamoyl-CoA reductase | SIN_1010781 | 0.017694 | 0.0252943 | −0.1137 |

| SIN_1021951 | 9.39E-55 | 1.25E-53 | 1.6535 | |||

| K09754 | CYP98A | 5-O-(4-coumaroyl)-D-quinate 3’-monooxygenase | SIN_1020090 | 9.97E-14 | 3.46E-13 | 0.3433 |

| SIN_1017700 | 0.124294 | 0.1552851 | −0.0616 | |||

| K09755 | CYP84A or F5H | ferulate-5-hydroxylase | SIN_1015002 | 0.025818 | 0.0359606 | 0.6766 |

| SIN_1004523 | 6.27E-06 | 1.29E-05 | 0.979 | |||

| K10775 | PAL | phenylalanine ammonia-lyase | SIN_1005477 | 4.81E-10 | 1.33E-09 | −0.3805 |

| SIN_1004404 | 0.005309 | 0.0081118 | 0.1208 | |||

| SIN_1002445 | 1.66E-20 | 7.95E-20 | −1.0759 | |||

| K13065 | HCT | shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase | SIN_1017673.cds1 | 0.007176 | 0.0107963 | −0.8598 |

| SIN_1003229.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1010921 | 0.200051 | 0.2409115 | −0.2529 | |||

| SIN_1011729.cds1 | 0.785928 | 0.8191824 | 0.0303 | |||

| SIN_1010792 | 3.49E-20 | 1.65E-19 | −0.3967 | |||

| SIN_1019151.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1024063.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1021099.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1016842 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1023599 | 1.20E-153 | 5.60E-152 | 4.724 | |||

| SIN_1025802.cds1 | 0.048361 | 0.0647334 | 0.2709 | |||

| SIN_1003230.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1018030.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1012231.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1018027.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1017682.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1017675.cds1 | 0.002381 | 0.0037883 | −1.098 | |||

| SIN_1018026.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1021964 | 0.000118 | 0.0002154 | −0.6343 | |||

| SIN_1016241 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1019159.cds1 | 4.69E-117 | 1.61E-115 | −3.1411 | |||

| SIN_1007058 | 9.49E-06 | 1.92E-05 | −0.9977 | |||

| SIN_1018028.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1024064.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1019371.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1003228.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1017676.cds1 | 8.91E-11 | 2.58E-10 | −1.2595 | |||

| SIN_1010791 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1002411.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1021965 | 3.21E-18 | 1.39E-17 | −0.9455 | |||

| SIN_1016843 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1017651.cds1 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1006306 | 0.341195 | 0.3904707 | 0.2885 | |||

| SIN_1007695.cds1 | Na | |||||

| K13066 | COMT | caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase | SIN_1009240 | 1.14E-205 | 7.77E-204 | 4.279 |

| SIN_1005907 | 3.14E-18 | 1.36E-17 | −0.4935 | |||

| SIN_1009239 | 8.95E-41 | 8.45E-40 | 1.7795 | |||

| SIN_1009242 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1005145 | 6.76E-07 | 1.50E-06 | −1.0146 | |||

| SIN_1013208 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1002216 | 1.06E-06 | 2.31E-06 | 0.5436 | |||

| SIN_1013206 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1009243 | 1.87E-34 | 1.49E-33 | 0.8118 | |||

| SIN_1013207 | Na | |||||

| SIN_1009241 | 9.02E-19 | 4.00E-18 | −1.1045 | |||

| K22395 | CAD | cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase | SIN_1019560.cds1 | 1.16E-28 | 7.67E-28 | 0.8888 |

| SIN_1006729.cds1 | Na | |||||

Additionally, it is implicated in various pathways, such as phenylalanine metabolism, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, metabolic pathways, and the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. In phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, p-coumaric acid is produced from cinnamic acid through the action of trans-cinnamate 4-monooxygenase (CYP73A). The unigenes encoding CYP73A include SIN_1023328, SIN_1007513, SIN_1024388, SIN_1024387, and SIN_1024386. Of these, two unigenes were upregulated during the mature stage, while one was upregulated in the young stage.

4-coumarate–CoA ligase (4CL) catalyzes the conversion of p-coumaric acid to p-coumaroyl CoA. The unigenes encoding 4CL include SIN_1026210, SIN_1008068, SIN_1022003, SIN_1010817, SIN_1010914, SIN_1026519, SIN_1009267, SIN_1006084, SIN_1006083, SIN_1024601, SIN_1023853, and SIN_1004004. p-coumaroyl CoA can either be converted into p-coumaraldehyde by cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR) or take an alternative route to form p-coumaroyl shikimic acid. CCR is encoded by unigenes SIN_1010781 (upregulated at the mature stage) and SIN_1021951 (upregulated at the young stage). Cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase, a key enzyme in monolignol biosynthesis, catalyzes the conversion of p-coumaraldehyde to p-coumaryl alcohol and is encoded by unigenes SIN_1019560.cds1 and SIN_1006729.cds1.

The second monolignol is synthesized through the shikimic acid pathway. In this pathway, p-coumaroyl-CoA is converted into p-coumaroyl shikimic acid by shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase. This enzyme is encoded by unigenes such as SIN_1017673.cds1, SIN_1003229.cds1, SIN_1010921, SIN_1011729.cds1, SIN_1010792, SIN_1019151.cds1, SIN_1024063.cds1, and many others. Of these, nine unigenes are upregulated at the mature stage, while four are upregulated during the young stage. CYP98A catalyzes the conversion of p-coumaroyl shikimic acid to caffeoyl shikimic acid and is encoded by SIN_1020090 (upregulated at the young stage) and SIN_1017700 (upregulated at the mature stage). Shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase further catalyzes the conversion of caffeoyl shikimic acid to caffeoyl-CoA, encoded by 34 unigenes, nine of which are upregulated at the mature stage of sesame seed development.

Caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase, encoded by seven unigenes, is involved in catalyzing the conversion of caffeoyl-CoA to feruloyl-CoA. Four of these unigenes were upregulated during the young stage, with most showing over fivefold increases in expression, indicating that this enzyme is more abundant in the early stages of seed development. The conversion of feruloyl-CoA to coniferyl aldehyde is catalyzed by cinnamoyl-CoA reductase (CCR), which is encoded by two unigenes. Another key enzyme in the synthesis of the second monolignol is cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase, which facilitates the conversion of coniferyl aldehyde to coniferyl alcohol. This enzyme is also encoded by two unigenes.

The biosynthesis of syringyl monolignol in angiosperms involves the hydroxylation and methylation of guaiacyl intermediates, particularly coniferyl aldehyde. Coniferyl aldehyde 5-hydroxylase (CAld5H) and caffeate O-methyltransferase (COMT) play crucial roles in this process [44]. As coniferyl aldehyde is catalyzed and converted into 5-hydroxy-coniferaldehyde by the enzyme ferulate-5-hydroxylase (CYP84A), we found two unigenes encoding thes enzymes. CYP84A, a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, catalyzes the 5-hydroxylation of coniferyl aldehyde to 5-hydroxyconiferyl aldehyde [45]. COMT then preferentially methylates 5-hydroxyconiferyl aldehyde to sinapyl aldehyde, acting as a 5-hydroxyconiferyl aldehyde O-methyltransferase [46]. The third monolignol is produced through the conversion of sinapaldehyde to sinapyl alcohol, catalyzed by cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase, which is also encoded by two unigenes.

As presented in Table 3 it is clearly observed that more genes upregulated during the later stage of seed developmental stage. The results reveal substantial changes in the sesame transcriptome tied to the production and accumulation of lignan components in seeds, particularly in the later phases of development, emphasizing the temporal and developmental regulation of lignan-associated genes. In the early phases of embryogenesis, cycles of lignan synthesis and degradation ensure a steady supply of carbon and other critical nutrients required for rapid cell division and embryo expansion. This could explain the observed increase in the number of hydrolases and transferases (refer to S. Table 1). During sesame seed development, resources are directed toward the production of storage compounds, including lignan and its derivatives. Taken together, these findings highlight notable differences in the physiological activities between the early and middle phases of sesame seed development. Similarly, Fatty acids are synthesized and broken down in early embryogenesis to fuel cell division and growth, possibly explaining the increase in enzymes like hydrolases and lipases that release fatty acids and glycerol [47, 48].

RNA seq validation

Six chosen candidate genes from sesame seeds that are known to aid in lignan metabolism were examined for steady-state mRNA levels using quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 7). The seed sample were used as calibrators to represent the baseline of gene expression to monitor the change in the expression levels for the examined genes in developing sesame seeds. As shown in Fig. 5 SIN_1022131, SIN_1022640, SIN_1010817, SIN_1003362, SIN_1010113, and SIN_1010690 genes showed seed-specific expression patterns with a relative maximum expression ratio up to ~ 13-fold and 10-fold in the case of SIN_1022131 and SIN_1022640, respectively. The RNA Seq data we generated was strongly confirmed to be valid by the generally identical expression trends that were seen at both stages (Fig. 8). It has been reported that the accumulation of lignans in sesame seeds occurs during seed development, with concentrations increasing as seeds mature [2, 49].

Fig. 8.

Six genes were randomly selected for qRT-PCR verification from the identified set. Among them, SIN_1010690, SIN_1010113, and SIN_1003362 are associated with lignan biosynthesis, SIN_1010817 encodes an isoform of 4-coumarate: CoA ligase (4CL), SIN_1022640 is linked to oil biosynthesis, and SIN_1022131 is related to TAG biosynthesis. Actin from S. indicum was used as the reference gene, and the relative expression levels of the six genes were calculated using the 2−∆∆Cq method

Overall, this study shows that sesame seeds are regulated in a coordinated and stage-specific manner at different stages of lignan biosynthesis. Our LC-MS/MS analysis identified key lignans and quantified their dynamic accumulation during seed development, with mature seeds exhibiting the highest concentrations. Profiling of targeted metabolites revealed the presence of major lignans, including sesamin, sesamolin, and sesaminol glucosides, with differences in elution patterns. Concurrently, transcriptome analysis revealed differential expression of genes involved in the phenylpropanoid and monolignol biosynthesis pathways. Notably, essential enzymes such as PAL, 4CL, CCR, COMT, and CAD showed developmentally controlled expression, implying transcriptional control over lignan accumulation. Further validation was carried out via qRT-PCR of selected genes, which confirmed the RNA-Seq expression trends. The results of our study provide integrated transcriptome and metabolome insights into sesame’s lignan biosynthesis regulation paving the way for further functional validation and crop improvement.

Discussion

This study encompasses a comprehensive set of metabolomic and transcriptome studies to better understand the dynamics of lignan production throughout sesame seed development. LC-MS/MS-based targeted profiling allowed for precise quantification of key lignans, whilst RNA-Seq analysis revealed important information about the temporal regulation of genes involved in the monolignol biosynthesis pathway. The findings shed light on the metabolome and transcriptome mechanisms underlying lignan accumulation in Sesamum indicum. Although previous studies primarily focused on major lignans such as sesamin and sesamolin [2, 27, 50], Our data extend these findings by demonstrating that additional lignan metabolites also follow distinct accumulation patterns. Importantly, the observed upregulation of key biosynthetic genes at the mature stage is not merely a reflection of increased metabolic flux but may indicate a coordinated regulatory mechanism that optimizes lignan synthesis as a defense strategy and quality trait [51].

Plant metabolites can be detected using metabolomics under various growth conditions using high-throughput tools that allow simultaneous qualitative and quantitative analysis of a wide range of metabolites, thereby helping us to better understand how metabolites interact with physiological changes [52]. In our present study analysis of LC-MS revealed lignan composition and content in sesame seeds during development and we observed significant variations in the levels of different lignans. For example, pinoresinol ranged from 0.7 to 0.9 mg/kg, sesaminol from 0.5 to 1.7 mg/kg, sesamin from 135 to 234 mg/kg, sesamolin from 46.7 to 116.4 mg/kg, DiGlyc-sesaminol from 5195 to 5794 mg/kg, and Tri-Glyc-sesaminol from 139 to 171 mg/kg. No sesamol was detected. Our result for DiGlyc-Sesaminol and Tri-GlycSesaminol is an agreement with High accumulation of Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) content flax seed at the nearly mature stage S5 [53–56]. Previous studies reported a range of concentrations for various lignans, including sesamin content of 5.19 mg/g [57], 2.48 mg/g [27], 0.67–6.35 mg/g [50], 2.49 mg/g [58], 1.55 mg/g [59], 27–67% of total lignan [60]. Further, studies also reported sesamolin content of 18.01 mg/g [58], 20–59% of total lignan [60], 0.62 mg/g [59], and 1.72 mg/g [27].

Our findings are comparable with earlier research that have explored lignan content in sesame seeds; nevertheless, inconsistencies in concentration values, such as the lower sesamin levels found in our study compared to prior publication [61] may reflect differences in experimental methodologies or sesame varieties. For example, our study quantified sesamin in the range of 135 to 234 mg/kg, compared to a reported range of 77 to 930 mg/100 g by [61]. The observed differences can be attributed to methodological variations. In the cited study, a multi-step extraction and purification protocol was applied, involving defatting of seeds with n-hexane, sequential elution with methanol and chloroform/methanol mixtures, and further purification using silica gel chromatography and TLC prior to HPLC-DAD quantification. Such procedures are designed to isolate and enrich specific lignan compounds, often resulting in higher concentration values. In contrast, our study utilized a simplified and biologically relevant approach: lignans were extracted directly from whole seeds using 80% ethanol and quantified using LC-MS/MS without prior defatting or fractionation. Moreover, the concentrations reported in our study are based on fresh whole seed weight, while the reference study analyzed defatted flour or oil fractions, which inherently concentrate lignans such as sesamin. Differences in analytical platforms, matrix type, and extraction efficiency likely account for the variation in absolute values. Nonetheless, our approach provides a robust and reproducible method to assess lignan accumulation dynamics under developmental stages. It is critical to acknowledge that genotype-specific variations play a pivotal role in lignan accumulation, as seen in other studies that highlighted the impact of genetic factors on lignan content [62, 63].

Beyond health benefits of lignan such as pharmaceutical activities such as antibacterial [64], antiviral [65], antitumor [66], HIV reverse transcription inhibition [67], cytotoxic [68], antioxidant [69–74], Remarkable ecological functions of lignan for plants, offering protection against herbivores and microorganisms reported by [75, 76]. In the present study study, we observed that lignan accumulation progressed more slowly during the early stages and accelerated in the later stages. Similar findings have been reported for FA content in Brassica napus, Glycine max, and Camellia oleifera, with higher levels observed at later stages [77–80]. Reported continuous accumulation of total lignan detected 15 days after pollination to seed maturation but sesamolin show decreasing trend [28]. Furthermore, a study by [33] on Herpetospermum-specific lignans supports our findings, as they detected no lignans at the early stage but observed lignan accumulation during the maturation stage. In sesame, the observed variation in lignan content between seed developmental stages suggests that lignan accumulation may be tightly regulated and may serve as a protective mechanism, particularly during the maturation phase.

The lignan content of sesame seeds is a quality trait and an important breeding target [81]. Lignans are natural chemical compounds of plant origin that are naturally occurring secondary metabolites formed by the shikimic acid pathway [3]. Among the monomers that form lignans are cinnamyl alcohol, cinnamic acid, propenylbenzene, and allylbenzene. Lignans are classified into two categories: classical lignans and neolignans [7]. The molecular bond between the monomers in classical lignans is between β-β’ positions. While, neolignans are compounds with structural units coupled differently, without the β-β′ bond [3].

Lignans, such as sesamin and sesamolin, are antioxidants that are produced through the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway. In the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway tyrosine or phenylalanine is converted into coniferyl alcohol, which is then stereoselectively combined to give pinoresinol. Pinoresinol is further metabolized in mature seeds to piperitol, sesamin, and sesamolin, which are catalyzed by O2/NADPH cytochrome P450s and then methylenedioxy bridges are formed [82, 83].

The three precursors of Lignan Biosynthesis were p-coumaric acid, sinapic acid, and ferulic acid. They arise from shikimic acid pathway, via phenylalanine. The first three reactions reduce the carboxylic group of the hydroxycinnamates to alcohol group, with the formation of corresponding alcohols, called monolignols, that is, p-coumaric alcohol, sinnapyl alcohol, and coniferyl alcohol [84].

The molecular basis of lignan biosynthesis in sesame involves the phenylpropanoid pathway, where enzymes such as phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) and cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H) catalyze key steps. Our transcriptomic analysis revealed significant upregulation of genes involved in this pathway during the later stages of seed development. This correlates with increased lignan accumulation, suggesting that these enzymes play a crucial role in regulating the final stages of lignan biosynthesis. Specifically, we identified 154 unigenes encoding enzymes involved in monolignol formation, with 45 genes upregulated at the mature stage. This upregulation likely complements the enhanced lignan accumulation observed at this stage.

4CL is an important enzyme in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and affects lignan biosynthesis [33]. We found 4CL involved across different pathways of phenylpropanoid pathway. An enzyme 4-coumarate–CoA ligase (4CL) catalyze the the conversion of Cinnamic acid to Cinnamoyl-CoA and it was encoded by 6 unigenes among these six were upregulated at young stage while five unigenes were upregulated at matured stage. Similarly [33] reported two upregulated and one downregulated genes encoding 4CL. This might suggest that multiple isoforms and paralogous genes may perform redundant functions [33]. The other pathway 4CL involved in is in the conversion of p-coumaric acid to p-coumaroyl-CoA, which is encoded by 12 unigenes in the present study. Four overlapping yet distinct isoforms of 4CL reported by [85] in Arabidopsis and Five 4CL genes identified in rice [86]. A decrease in lignin content, particularly guaiacyl units as a result of Antisense suppression of 4CL in Arabidopsis were reported by [87]. In subsequent syntheses, coniferyl alcohol is a crucial starting material for synthesizing lignans. This is a very intricate synthesis process regulated by various genes and enzymes [33]. Pinoresinol is a crucial intermediate in the process of lignan formation. Lignans are derived through the oxidation and cyclization of two molecules of coniferyl alcohol in the presence of the dirigent protein (DIR) [88]. Pinoresinol undergoes cyclization and oxidation with another molecule of coniferyl alcohol to form another intermediate [33].

Interestingly, the up-regulation of specific genes, such as 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL), demonstrates the relevance of various isoforms in controlling lignan production. Our findings are consistent with previous research in Arabidopsis and rice, which found varied expression patterns of 4CL genes during lignan formation [33, 85, 86]. The differential expression of these genes during seed development highlights the complexities of lignan biosynthesis and shows that precise gene expression regulation is required for efficient lignan accumulation.

A reaction that involve the conversion of Cinnamic acid to p-coumaric acid were catalyzed by an enzyme 5-O-(4-coumaroyl)-D-quinate 3’-monooxygenase (CYP98A). This enzyme were encoded by two unigenes and one unigenes were upregulated at early stage of the seed development while the other upregulated at matured stage. Alteration of cyp98a3 in Arabidopsis resulted in reduced lignin content, altered lignin composition, and developmental defects [89].

The final reaction formation of monolignan produced in the phenayl propanoid pathway as seen in kegg pathway were catalyzed by Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD). Phenylalanine converted to cinnamic acid by cinnamyl-alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD). From our present study three unigenes were identified to encode this enzyme. Among these unigenes two were upregulated at matured stage while one unigene is upregulated at young stage of seed development. Mutation in CAD resulting in reduced lignin content and altered stem structure(91). It is a key enzyme in lignin biosynthesis, catalyzing the final step of monolignol production [91]. CAD is an enzyme typically exists as a dimer with subunit molecular weights ranging from 42.5 to 44 kDa [92]. High affinity of CAD for coniferyl aldehyde and coniferaldehyde substrates were reported by [92, 93].

The differential expression of various isoforms of 4CL and other crucial enzymes, such as CYP98A and CAD, may mechanistically arise from stage-specific transcriptional regulation potentially influenced by developmental signals. The existence of both early and late-expressed 4CL isoforms indicates a divergence in metabolic pathways, with one group facilitating primary metabolism in early seed development and another focused on the increased synthesis of secondary metabolites in later stages. This bifurcation may potentially be influenced by external cues or hormone signals that remain to be fully elucidated. Our findings resonate with similar observations in other crops [77–80], indicating that such metabolic shifts are a conserved strategy for optimizing seed quality. Moreover, our research emphasises the interaction between metabolic and transcriptome changes during the development of sesame seeds. Through the integration of transcriptomic and metabolomic data, we have elucidated the impact of gene expression patterns on lignan content. This could lead to the identification of candidate genes for breeding programs aimed at enhancing lignan levels in sesame, a valuable trait for both agricultural and pharmaceutical applications.

Conclusion

In this study, we performed transcriptome and metabolome analysis to dissect the regulatory networks of lignan biosynthesis from two different seed developmental stages (young and matured stages) of sesame. Almost all the metabolites quantified are expressed only at the matured stage and none of them were expressed at young stage. Most of the DEGs related to lignan biosynthesis were expressed during the subsequent stage. Through DEGs analysis, we also identified several important enzymes, including 4CL, CAD, PAL, CCR, and COMT, along with the unigenes they encode. The results showed that the gene expression profiles of different seed development stage was closely related to the pattern of metabolite accumulation. Taken together, our findings provide new insights into the regulation of lignan biosynthesis in sesame and offer a valuable resource for future molecular validation studies and potential breeding applications.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CAD

Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase

- 4CL

4-coumarate–CoA ligase

- PAL

Phenylalanine ammonia lyase

- CCR

Cinnamoyl-CoA reductase

- COMT

Caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- GO

Gene ontology

- CPM

Count per million

- LFC

Log fold change

- LODs

Limits of detection

- LOQs

Limits of quantification

Authors’ contributions

Author ContributionsConceptualization: M.A., B.B.Formal analysis: M.A., B.B., Investigation: M.A., B.B., Funding acquisition: M.A.Methodology: M.A., B.B., Resources: M.A., M.GSupervision: M.A.,T.M, D.B, K.TWriting – original draft: B.B., M.A., Writing – review & editing: B.B., M.A.,M.G., D.B, T.M., K.T.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation under grant number REF 3.4 – ETH – 1146528 – GF - E.

Data availability

The raw sequencing data generated and analyzed during this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1197728.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fukuda Y, Osawa T, Namiki M, Ozaki T. Studies on antioxidative substances in Sesame seed. Agric Biol Chem. 1985;49(2):301–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ono E, Nakai M, Fukui Y, Tomimori N, Fukuchi-Mizutani M, Saito M, et al. Formation of two methylenedioxy bridges by a sesamum CYP81Q protein yielding a furofuran lignan, (+)-sesamin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(26):10116–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cui Q, Du R, Liu M, Rong L. Lignans and their derivatives from plants as antivirals. Molecules. 2020;25(1):183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ali ES, Akter S, Ramproshad S, Mondal B, Riaz TA, Islam MT, et al. Targeting Ras-ERK cascade by bioactive natural products for potential treatment of cancer: an updated overview. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22(1):246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haruna A, Yahaya SM. Recent advances in the chemistry of bioactive compounds from plants and soil microbes: a review. Chem Africa. 2021;4(2):231–48. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samtiya M, Aluko RE, Dhewa T, Moreno-Rojas JM. Potential health benefits of plant food-derived bioactive components: an overview. Foods. 2021;10(4):839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motyka S, Jafernik K, Ekiert H, Sharifi-Rad J, Calina D, Al-Omari B, et al. Podophyllotoxin and its derivatives: potential anticancer agents of natural origin in cancer chemotherapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;158:114145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gan XH, Robin JP, Huerta JMM, Braquet P, Bonavida B. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-?) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1?) secretion but not IL-6 from activated human peripheral blood monocytes by a new synthetic demethylpodophyllotoxin derivative. J Clin Immunol. 1994;14(5):280–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahlqvist SR, Landberg G, Roos G, Norberg B. Cell cycle effects of the anti-rheumatic agent CPH82. Rheumatology. 1994;33(4):327–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghisalberti EL. Cardiovascular activity of naturally occurring lignans. Phytomedicine. 1997;4(2):151–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuroda T, Kondo K, Iwasaki T, Ohtani A, Takashima K. Synthesis and hypolipidemic activity of diesters of arylnaphthalene Lignan and their heteroaromatic analogs. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 1997;45(4):678–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berlin J, Bedorf N, Mollenschott C, Wray V, Sasse F, Höfle G. On the Podophyllotoxins of root cultures of Linum flavum. Planta Med. 1988;54(03):204–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davin LB, Lewis NG. An historical perspective on Lignan biosynthesis: Monolignol, allylphenol and hydroxycinnamic acid coupling and downstream metabolism. Phytochem Rev. 2003;2(3):257–88. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majdalawieh AF, Dalibalta S, Yousef SM. Effects of Sesamin on fatty acid and cholesterol metabolism, macrophage cholesterol homeostasis and serum lipid profile: A comprehensive review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;885:173417. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Moazzami AA, Andersson RE, Kamal-Eldin A. HPLC analysis of sesaminol glucosides in sesame seeds. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;54(3):633–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moazzami AA, Andersson RE, Kamal-Eldin A. Characterization and analysis of Sesamolinol diglucoside in sesame seeds. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2006;70(6):1478–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moazzami AA. Sesame Seed Lignans Diversity, Human Metabolism and Bioactivities. [Uppsala]: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. 2006. Available from: https://pub.epsilon.slu.se/1264/1/Thesis_Ali_Moazzami_2006_Final.pdf#page=11.22. Cited 29 Apr 2025.

- 18.Murata J, Ono E, Yoroizuka S, Toyonaga H, Shiraishi A, Mori S, et al. Oxidative rearrangement of (+)-sesamin by CYP92B14 co-generates twin dietary lignans in Sesame. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dar AA, Arumugam N. Lignans of sesame: purification methods, biological activities and biosynthesis – a review. Bioorg Chem. 2013;50:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuji Y, Uchida A, Fukahori K, Chino M, Ohtsuki T, Matsufuji H. JJ Barchi editor 2018 Chemical characterization and biological activity in young Sesame leaves (Sesamum indicum L.) and changes in iridoid and polyphenol content at different growth stages. PLoS ONE 13 3 e0194449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hata N, Hayashi Y, Okazawa A, Ono E, Satake H, Kobayashi A. Comparison of Sesamin contents and CYP81Q1 gene expressions in aboveground vegetative organs between two Japanese Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) varieties differing in seed Sesamin contents. Plant Sci. 2010;178(6):510–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dat NT, Dang NH, Thanh LN. New flavonoid and pentacyclic triterpene from Sesamum indicum leaves. Nat Prod Res. 2016;30(3):311–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasumoto S, Katsuta M. Breeding a high-lignan-content sesame cultivar in the prospect of promoting metabolic functionality. Japan Agricultural Research Quarterly: JARQ. 2006;40(2):123–9. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dar AA, Kancharla PK, Chandra K, Sodhi YS, Arumugam N. Assessment of variability in lignan and fatty acid content in the germplasm of sesamum indicum L. J Food Sci Technol. 2019;56(2):976–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muthulakshmi C, Pavithra S, Selvi S. Evaluation of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) germplasm collection of Tamil Nadu for -linolenic acid, Sesamin and Sesamol content. Afr J Biotechnol. 2017;16(23):1308–13. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Usman SM, Viswanathan PL, Manonmani S, Uma D. Genetic studies on sesamin and sesamolin content and other yield attributing characters in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). Electron J PLANT Breed. 2020;11(01). Available from: http://www.ejplantbreeding.org/index.php/EJPB/article/view/3443. Cited 19 Apr 2025.

- 27.Shi L, Liu R, Jin Q, Wang X. The contents of lignans in Sesame seeds and commercial Sesame oils of China. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2017;94(8):1035–44. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ke T, Dong C, Mao H, Zhao Y, Chen H, Liu H et al. Analysis of expression sequence tags from a full-length-enriched cDNA library of developing sesame seeds (Sesamum indicum). BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11(1). Available from: https://bmcplantbiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2229-11-180. Cited 16 Sep 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Marchand PA, Lewis NG, Zajicek J. Oxygen insertion in Sesamumindicum furanofuran lignans. Diastereoselective syntheses of enzyme substrate analogues. Can J Chem. 1997;75(6):840–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dossou SSK, Xu F, Cui X, Sheng C, Zhou R, You J, et al. Comparative metabolomics analysis of different Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) tissues reveals a tissue-specific accumulation of metabolites. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21(1):352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Dong S, Bai W, Jia J, Gu R, Zhao C, et al. Metabolic and transcriptional regulation of phenolic conversion and tocopherol biosynthesis during germination of Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) seeds. Food Funct. 2020;11(11):9848–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun B, Wang P, Guan M, Jia E, Li Q, Li J, et al. Tissue-specific transcriptome and metabolome analyses reveal candidate genes for lignan biosynthesis in the medicinal plant schisandra sphenanthera. BMC Genomics. 2023;24(1):607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z, Tan M, Zhang Y, Jia Y, Zhu S, Wang J, et al. Integrative analyses of targeted metabolome and transcriptome of isatidis radix autotetraploids highlighted key polyploidization-responsive regulators. BMC Genomics. 2021;22(1):670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mason JK, Thompson LU. Flaxseed and its lignan and oil components: can they play a role in reducing the risk of and improving the treatment of breast cancer? Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39(6):663–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen CY, Liu SY, Yan Y, Yin L, Di P, Liu HM, et al. Candidate genes involved in the biosynthesis of Lignan in schisandra chinensis fruit based on transcriptome and metabolomes analysis. Chin J Nat Med. 2020;18(9):684–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hong CP, Kim CK, Lee DJ, Jeong HJ, Lee Y, Park SG, et al. Long-read transcriptome sequencing provides insight into lignan biosynthesis during fruit development in schisandra chinensis. BMC Genomics. 2022;23(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rahman MMA, Dewick PM, Jackson DE, Lucas JA. Lignans of forsythia intermedia. Phytochemistry. 1990;29(6):1971–80. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wan Y, Li H, Fu G, Chen X, Chen F, Xie M. The relationship of antioxidant components and antioxidant activity of sesame seed oil. J Sci Food Agric. 2015;95(13):2571–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bekele B, Andargie M, Gallach M, Beyene D, Tesfaye K. Decoding gene expression dynamics during seed development in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) through RNA-seq analysis. Genomics. 2025;117(2):110997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bekele B, Andargie M, Mekonnen T, Beyene D, Tesfaye K. Characters associations and principal component analysis for quantitative traits of Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) genotypes from Ethiopia. Ecol Genet Genomics. 2025;35:100357.

- 41.Altschul S. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 – ∆∆CT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi T, Sweeney C, Sutherland SC. Underway physical oceanography and carbon dioxide measurements during Nathaniel B. Palmer cruise 320619970216. PANGAEA. 2016. p. 11522 data points. Available from: https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.866753. Cited 20 Jul 2025.

- 44.Higuchi T. Pathways for monolignol biosynthesis via metabolic grids: coniferyl aldehyde 5-hydroxylase, a possible key enzyme in angiosperm syringyl lignin biosynthesis. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B. 2003;79B(8):227–36. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osakabe K, Tsao CC, Li L, Popko JL, Umezawa T, Carraway DT, et al. Coniferyl aldehyde 5-hydroxylation and methylation direct syringyl lignin biosynthesis in angiosperms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(16):8955–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li L, Popko JL, Umezawa T, Chiang VL. 5-hydroxyconiferyl aldehyde modulates enzymatic methylation for syringyl monolignol formation, a new view of monolignol biosynthesis in angiosperms. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(9):6537–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ruuska SA, Girke T, Benning C, Ohlrogge JB. Contrapuntal networks of gene expression during Arabidopsis seed filling[W]. Plant Cell. 2002;14(6):1191–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abdullah HM, Akbari P, Paulose B, Schnell D, Qi W, Park Y, et al. Transcriptome profiling of camelina sativa to identify genes involved in triacylglycerol biosynthesis and accumulation in the developing seeds. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016;9(1):136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumazaki T, Yamada Y, Karaya S, Kawamura M, Hirano T, Yasumoto S, et al. Effects of day length and air and soil temperatures on Sesamin and Sesamolin contents of Sesame seed. Plant Prod Sci. 2009;12(4):481–91. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williamson KS, Morris JB, Pye QN, Kamat CD, Hensley K. A survey of Sesamin and composition of Tocopherol variability from seeds of eleven diverse Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) genotypes using HPLC-PAD‐ECD. Phytochem Anal. 2008;19(4):311–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tong Z, Yang K, Chen X, Xu F, Sui X, Huang Y et al. Multiomic analysis of the synthetic pathways of secondary metabolites in tobacco leaves at different developmental stages. Front Plant Sci. 2025;16. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2025.1615756/full. Cited 18 Jul 2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Yuan Y, Zuo J, Zhang H, Zu M, Yu M, Liu S. Transcriptome and metabolome profiling unveil the accumulation of flavonoids in dendrobium officinale. Genomics. 2022;114(3):110324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eliasson C, Kamal-Eldin A, Andersson R, Åman P. High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of secoisolariciresinol diglucoside and hydroxycinnamic acid glucosides in flaxseed by alkaline extraction. J Chromatogr A. 2003;1012(2):151–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ford JD, Huang KS, Wang HB, Davin LB, Lewis NG. Biosynthetic pathway to the cancer chemopreventive secoisolariciresinol Diglucoside – Hydroxymethyl glutaryl Ester-Linked Lignan oligomers in flax (Linum u sitatissimum) seed. J Nat Prod. 2001;64(11):1388–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hano C, Martin I, Fliniaux O, Legrand B, Gutierrez L, Arroo RRJ, et al. Pinoresinol–lariciresinol reductase gene expression and secoisolariciresinol diglucoside accumulation in developing flax (Linum usitatissimum) seeds. Planta. 2006;224(6):1291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Madhusudhan B, Wiesenborn D, Schwarz J, Tostenson K, Gillespie J. A dry mechanical method for concentrating the lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside in flaxseed. LWT. 2000;33(4):268–75. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang L, Zhang Y, Li P, Zhang W. Variation of sesamin and sesamolin contents in sesame cultivars from China. Pak J Bot. 2013;45(1)177-182.

- 58.Wang L, Zhang Y, Li P, Wang X, Zhang W, Wei W, et al. HPLC analysis of seed Sesamin and Sesamolin variation in a Sesame germplasm collection in China. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2012;89(6):1011–20. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rangkadilok N, Pholphana N, Mahidol C, Wongyai W, Saengsooksree K, Nookabkaew S, et al. Variation of sesamin, sesamolin and tocopherols in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) seeds and oil products in Thailand. Food Chem. 2010;122(3):724–30. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bhunia RK, Chakraborty A, Kaur R, Gayatri T, Bhat KV, Basu A, et al. Analysis of fatty acid and Lignan composition of Indian germplasm of Sesame to evaluate their nutritional merits. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2015;92(1):65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moazzami AA, Haese SL, Kamal-Eldin A. Lignan contents in sesame seeds and products. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2007;109(10):1022–7. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kancharla PK, Arumugam N. Variation of oil, sesamin, and sesamolin content in the germplasm of the ancient oilseed crop Sesamum indicum L. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2020;97(5):475–83. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smeds AI, Jauhiainen L, Tuomola E. Characterization of variation in the lignan content and composition of winter rye, spring wheat, and spring oat. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57(13):5837–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kawazoe K, Yutani A, Tamemoto K, Yuasa S, Shibata H, Higuti T, et al. Phenylnaphthalene compounds from the subterranean part of Vitex rotundifolia and their antibacterial activity against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Nat Prod. 2001;64(5):588–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Janmanchi D, Tseng YP, Wang KC, Huang RL, Lin CH, Yeh SF. Synthesis and the biological evaluation of arylnaphthalene lignans as anti-hepatitis B virus agents. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18(3):1213–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Capilla A. Antitumor agents. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new compounds related to podophyllotoxin, containing the 2,3-dihydro-1,4-benzodioxin system. Eur J Med Chem. 2001;36(4):389–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cow C, Leung C, Charlton JL. Antiviral activity of arylnaphthalene and aryldihydronaphthalene lignans. Can J Chem. 2000;78(5):553–61. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu SJ, Wu TS. Cytotoxic arylnaphthalene lignans from phyllanthus oligospermus. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2006;54(8):1223–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hadeel SY, Khalida SA, Walsh M. Antioxidant activity of Sesame seed lignans in sunflower and flaxseed oils. Food Res. 2019;4(3):612–22. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hassanein EHM, Althagafy HS, Baraka MA, Abd-alhameed EK, Ibrahim IM, Abd El-Maksoud MS et al. The promising antioxidant effects of lignans: Nrf2 activation comes into view. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2024; Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00210-024-03102-x. Cited 9 Sep 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Hu C, Yuan YV, Kitts DD. Antioxidant activities of the flaxseed lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside, its aglycone secoisolariciresinol and the mammalian lignans enterodiol and enterolactone in vitro. Food Chem Toxicol. 2007;45(11):2219–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mahendra Kumar C, Singh SA. Bioactive lignans from Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.): evaluation of their antioxidant and antibacterial effects for food applications. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52(5):2934–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Polat Kose L, Gulcin İ. Evaluation of the antioxidant and antiradical properties of some phyto and mammalian lignans. Molecules. 2021;26(23):7099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Suja KP, Jayalekshmy A, Arumughan C. Antioxidant activity of sesame cake extract. Food Chem. 2005;91(2):213–9. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fang X, Hu X. Advances in the synthesis of Lignan natural products. Molecules. 2018;23(12):3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamauchi S, Taniguchi E. Synthesis and insecticidal activity of lignan analogs (II). Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1992;56(3):412–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lin P, Wang K, Zhou C, Xie Y, Yao X, Yin H. Seed transcriptomics analysis in camellia Oleifera uncovers genes associated with oil content and fatty acid composition. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(1):118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Woodfield HK, Sturtevant D, Borisjuk L, Munz E, Guschina IA, Chapman K, et al. Spatial and temporal mapping of key lipid species in Brassica napus seeds. Plant Physiol. 2017;173(4):1998–2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Woodfield HK, Cazenave-Gassiot A, Haslam RP, Guschina IA, Wenk MR, Harwood JL. Using lipidomics to reveal details of lipid accumulation in developing seeds from oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.). Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA). 2018;1863(3):339–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang S, Miao L, He J, Zhang K, Li Y, Gai J. Dynamic transcriptome changes related to oil accumulation in developing soybean seeds. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9):2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Andargie M, Vinas M, Rathgeb A, Möller E, Karlovsky P. Lignans of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.): a comprehensive review. Molecules. 2021;26(4):883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jiao Y, Davin LB, Lewis NG. Furanofuran lignan metabolism as a function of seed maturation in Sesamum indicum: methylenedioxy bridge formation. Phytochemistry. 1998;49(2):387–94. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kato MJ, Chu A, Davin LB, Lewis NG. Biosynthesis of antioxidant lignans in sesamum indicum seeds. Phytochemistry. 1998;47(4):583–91. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hano CF, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Davin LB, Cort JR, Lewis NG, Editorial. Lignans: insights into their Biosynthesis, metabolic Engineering, analytical methods and health benefits. Front Plant Sci. 2021;11:630327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]