Abstract

Liver cirrhosis is a major manifestation of end-stage liver disease, and its pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies are key areas of research in hepatology. The limitations of traditional treatments have prompted researchers to turn their attention to immune regulatory mechanisms, among which macrophage polarization regulation has become the most promising therapeutic target. In this paper, the central role of macrophages in the development of cirrhosis and their regulatory network are described, with a focus on the critical role of M1/M2 polarization balance in the process of liver fibrosis. The dynamic polarization process of macrophages in the hepatic microenvironment is finely regulated: the M1 type activates hepatic stellate cells through proinflammatory factors, such as TNF-α and IL-1β, and promotes ECM deposition, whereas the M2 type participates in tissue repair and fibrosis reversal through the secretion of anti-inflammatory factors, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, and MMPs. On the basis of this mechanism, three main classes of intervention strategies have been developed: first, immunomodulatory therapies, including CCR2/CCR5 antagonists and cytokine modulation; second, small molecule-targeted drugs, such as JNK inhibitors and natural active ingredients; and third, cutting-edge biotherapeutic technologies, including genetically engineered macrophage and stem cell combination therapies. Importantly, the modulation of macrophage polarization through the targeted delivery of siRNA via nanocarriers or the induction of M2-type polarization using mesenchymal stem cells can significantly reduce the degree of fibrosis. However, these strategies still face challenges in translational applications, such as dynamic changes in the polarization state and insufficient target specificity. In the future, we need to analyse the heterogeneity of macrophages with the help of new technologies such as single-cell sequencing, develop spatiotemporal specific regulation schemes, and explore multitarget synergistic therapeutic strategies. The breakthroughs in this field will not only revolutionize the treatment mode of liver cirrhosis but also provide important reference information for the treatment of fibrotic diseases in other organs, marking the shift in liver disease treatment from traditional symptomatic treatment to a new era of precise immunomodulation. In conclusion, the targeted regulation of macrophage polarization has demonstrated significant therapeutic potential for liver cirrhosis, with its clinical application poised to revolutionize the treatment paradigm for liver diseases. Future studies should focus on leveraging single-cell technologies to elucidate macrophage heterogeneity and develop precision delivery strategies targeting macrophages, thereby advancing the clinical translation of personalized combination therapies based on macrophage modulation.

Keywords: Liver cirrhosis, Macrophage, Mechanism, Immune regulation

Introduction

Liver cirrhosis is among the leading causes of liver disease-related mortality worldwide. Clinically, the continued progression of untreated hepatic fibrosis leads to increased hepatic stellate cell activation, extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, and pseudofollicular formation, resulting in the distortion of the hepatic parenchyma and vascular structure and ultimately cirrhosis (Fig. 1). According to global health data, cirrhosis-related morbidity and mortality are increasing, especially in the context of increasing liver damage due to diseases such as hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease and fatty liver, with a poor prognosis, i.e., eventual progression to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or even metastatic cancer. The clinical manifestations of cirrhosis, including liver failure, portal hypertension, and associated complications (e.g., ruptured oesophageal varices and hepatic encephalopathy), severely affect the quality of life of patients and place a significant burden on healthcare systems worldwide [1, 2]. However, despite the progress made by modern medicine in the diagnosis and treatment of cirrhosis, the existing treatments still have major limitations, and liver transplantation, as the only means of cure, cannot be universally applied because of the shortage of donors and surgical risks [3]. In recent years, studies of the immune system have provided new perspectives for the treatment of cirrhosis. Macrophages play a key role as important cells in the immune environment of the liver. Macrophages not only participate in the immune response during liver injury, repair and fibrosis but also play complex roles in the hepatic immune response through their polarization (M1 and M2 types) [4]. The regulatory mechanism of macrophage polarization is considered among the central factors in the development of cirrhosis. M1-type macrophages are involved in liver injury through a proinflammatory response, whereas M2-type macrophages have an anti-inflammatory effect that helps to repair liver damage and promotes the reversal of fibrosis [5].

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of liver cirrhosis

With growing research on the role of macrophages, an increasing number of studies have shown that targeting the polarization state of macrophages may become a new approach for the treatment of liver cirrhosis. By regulating the polarization of macrophages, the immune response of the liver can be effectively modulated, slowing the process of liver fibrosis and promoting liver tissue repair [6]. In recent years, new therapeutic strategies, such as immunotherapy, drug-targeted therapy, and gene therapy, have begun to enter the clinical trial stage, providing a new direction for the treatment of cirrhosis; however, there are still some challenges to overcome [7].

This review explores the regulatory mechanisms of macrophages in cirrhosis, especially their role in liver fibrosis, and analyses how macrophage polarization regulation can be a new avenue for cirrhosis treatment. By summarizing existing studies, this paper provides a scientific basis for future clinical studies and therapeutic options.

Basis of liver cirrhosis-related immunology

The liver is not only a metabolic organ but also an important immune organ with a unique immune environment. Collectively, macrophages, T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells are the core immune cells involved in immune regulation in the liver. The immune environment of the liver has a unique immune tolerance mechanism to prevent unwanted immune responses to autoantigens. Through the interaction between hepatic stellate cells and Kupffer cells, signaling pathways are activated and inflammatory cells are released via TGF-β, PDGF, ROS, and MCP-1, which in turn further activate hepatic stellate cells. Activated stellate cells possess the function of sustaining Kupffer cell activation, ultimately forming a pathological cycle (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The interaction between hepatic stellate cells and Kupffer cells

Definition of the gut–liver axis

Macrophages are important components of the hepatic immune environment. There are two main types of macrophages in the liver: Kupffer cells and monocyte-derived macrophages. Kupffer cells are resident macrophages that reside in hepatic blood sinusoids and play important roles in the hepatic immune response. Kupffer cells play a powerful role in the removal of microorganisms, dead cells, and foreign substances from the blood. Kupffer cells can also regulate the liver immune response and maintain immune tolerance through the secretion of cytokines, chemokines and lysosomal enzymes; they not only play key roles in antigen presentation and immune surveillance but also prevent liver immune responses to food antigens and intestinal bacteria by maintaining immune homeostasis within the liver [8].

Macrophages of monocyte origin, on the other hand, usually enter the liver at the time of injury and participate in the immune response, fibrosis and liver repair; they enter the liver from the peripheral bloodstream through the action of chemokines and undergo polarization according to the immune microenvironment of the liver, exhibiting different functions. Macrophages of monocyte origin can be further differentiated into M1 or M2 macrophages, exerting proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory effects, respectively [9].

The role of other immune cells in the hepatic immune environment

In addition to macrophages, many other immune cells are present in the hepatic immune milieu and work together to maintain immune homeostasis in the liver and participate in immune responses. First, T cells are important executors of the adaptive immune response. T cells in the liver mainly include CD4 + helper T cells and CD8 + cytotoxic T cells. CD4 + T cells promote or inhibit immune responses by secreting cytokines and regulating the functions of other immune cells. In contrast, CD8 + T cells participate in immune surveillance by recognizing and killing pathogenic infected cells or tumour cells in the liver [10]. Second, the main role of B cells in the liver is to participate in the immune response by producing antibodies to remove pathogens. In disease processes such as cirrhosis, B cells can regulate the immune response of the liver and fight viral infections through interactions with macrophages [11]. Third, dendritic cells are important antigen-presenting cells capable of activating T cells and initiating specific immune responses through the phagocytosis of foreign pathogens. In immune regulation in the liver, dendritic cells coordinate T cell activation and regulate immune tolerance through interactions with macrophages [12]. Finally, natural killer cells (NK cells) are important innate immune cells that play an immunosurveillance role mainly by recognizing and killing infected or tumour cells. NK cells can also promote immune responses by secreting cytokines and enhancing macrophage function [13] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The role of other immune cells in the hepatic immune environment

Immune tolerance in the liver

The liver has unique immune tolerance mechanisms that prevent immune responses to liver autoantigens and prevent excessive immune activation in the liver. Immune tolerance in the liver depends not only on the immunosuppressive effects of macrophages but also on the maintenance of immune homeostasis through the tolerogenic effects of dendritic cells. The main function of dendritic cells in the liver is to present antigens and induce immune tolerance through interactions with T cells, which helps prevent the immune system from attacking the liver. This mechanism of immune tolerance in the liver allows the liver to avoid triggering an excessive immune response in the face of prolonged exposure to intestinal bacteria and food antigens [14].

The relationship between macrophages and liver fibrosis

Mechanisms of macrophage action in liver injury

The immune response of the liver plays a decisive role in liver injury, and macrophages, as key immune cells, are involved in the repair of liver injury through the phagocytosis of pathogens and damaged cells and the secretion of cytokines. In acute liver injury, macrophages can initiate an immune response by recognizing pathogens or injury-associated molecules to clear pathogens and dead cells. However, prolonged chronic liver injury or a sustained inflammatory response leads to a functional imbalance in macrophages, and the sustained activation of M1-type macrophages exacerbates the hepatic inflammatory response and drives the progression of liver fibrosis [15]. As liver injury persists, the role of macrophages becomes progressively more complex. During chronic liver disease or hepatic fibrosis, macrophages not only are involved in immune surveillance and repair but also exacerbate the fibrotic process through the secretion of profibrotic cytokines and growth factors that influence the activation of hepatic stellate cells and the accumulation of ECM [16].

Dual role of macrophages in the fibrotic process

Hepatic fibrosis is the result of long-term chronic injury to the liver, and the role of macrophages in this process is extremely complex, with both profibrotic and antifibrotic potential. M1-type macrophages activate hepatic stellate cells and promote collagen deposition through the secretion of inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, exacerbating the process of fibrosis. In contrast, M2-type macrophages inhibit fibrosis to a certain extent and promote the regeneration and repair of liver tissue through the secretion of anti-inflammatory factors and tissue repair factors, such as IL-10 and TGF-β [17]. In the early stages of fibrosis, the accumulation of M1-type macrophages promotes the progression of liver injury; however, in the later stages of fibrosis, the role of M2-type macrophages becomes more obvious. M2-type macrophages suppress the inflammatory response of M1-type macrophages through the secretion of regulatory factors and help restore immune homeostasis. In addition, M2-type macrophages can aid in the reversal of fibrosis by promoting liver repair. Studies have shown that inducing the polarization of M2-type macrophages helps slow the progression of fibrosis and improves liver function in liver fibrosis models [18, 19].

Mechanisms of macrophage regulation

Macrophage polarization and cirrhosis

The relationship between macrophage polarization and cirrhosis has become an important area of liver fibrosis research. Macrophages can undergo dynamic polarization in response to microenvironmental signals and are mainly classified into proinflammatory M1 macrophages and anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages [20]. This plasticity allows macrophages to play complex regulatory roles in liver injury, inflammation and fibrosis. M1-type macrophages play a predominantly pro-pathological role in the development of cirrhosis. When signals such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) are received, macrophages polarize towards the M1 type [21]. These types of macrophages lead to increased hepatocellular injury, mainly through the secretion of proinflammatory factors such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 and the production of large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) [22]. In addition, M1-type macrophages recruit additional inflammatory cells by secreting chemokines such as CCL2 and CXCL10, resulting in the formation of a vicious cycle [23]. Notably, M1-type macrophages can directly promote hepatic stellate cell activation and accelerate the progression of liver fibrosis through the secretion of factors such as PDGF and TGF-β1 [24].

In contrast, M2-type macrophages exhibit predominantly protective effects. When stimulated by factors such as IL-4 and IL-13, macrophages polarize towards the M2 type [25]. M2-type macrophages inhibit excessive inflammatory responses by secreting anti-inflammatory factors such as IL-10 and TGF-β; moreover, they promote tissue repair and can secrete a variety of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are involved in the degradation and remodelling of the ECM [26]. M2-type macrophages promote hepatic stellate apoptosis and fibrous tissue degradation through the secretion of factors such as arginase-1 and IL-10 during the regression stage of fibrosis [27] (Fig. 4). Notably, the polarization state of macrophages is not fixed but can be dynamically altered in response to microenvironmental signals. Recent studies have shown that this plasticity provides important targets for therapeutic intervention. By regulating the polarization state of macrophages, precise intervention in the process of liver fibrosis may be achieved [28].

Fig. 4.

Regulatory mechanisms of macrophages

Chemokines and receptors of macrophages

Macrophage recruitment and localization are critical for the development of liver fibrosis. During liver injury, chemokines expressed in tissues regulate macrophage migration and activation by binding to specific receptors on the macrophage surface. This chemokine-mediated cell migration plays a unique regulatory role in different stages of liver fibrosis.

The CCL2 (also known as MCP-1)/CCR2 signalling axis is among the most important pathways regulating macrophage recruitment. Studies have shown that in the early stage of liver injury, activated hepatic stellate cells and damaged hepatocytes secrete large amounts of CCL2. CCL2 promotes the migration of these cells from the bone marrow and peripheral blood to the liver through binding to the CCR2 receptor on the surface of monocyte-macrophages. Animal experiments have confirmed that CCR2 deficiency or blockade of the CCL2/CCR2 signalling pathway significantly reduces the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes to the damaged liver, thereby attenuating the degree of liver fibrosis [29]. In addition to the CCL2/CCR2 signalling pathway, the CCL5 (also known as RANTES)/CCR5 signalling pathway plays an important role in macrophage chemotaxis. Activated hepatic stellate cells are the main source of CCL5 in the liver. Experimental evidence suggests that CCL5 can synergize with CCL2 to increase monocyte–macrophage recruitment. In addition, CCL5 can promote the macrophage secretion of pro-fibrotic factors, which are directly involved in the progression of liver fibrosis [30]. Recent studies have revealed a unique role for the CX3CL1/CX3CR1 signalling axis in regulating the distribution of hepatic macrophage subpopulations. Macrophages with high CX3CR1 expression tend to localize near hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells, and this specific localization is important for the maintenance of hepatic immune homeostasis. The function and distribution of these settled macrophages are significantly altered during fibrosis progression, suggesting that the dysregulation of the chemokine network may be among the key factors in disease progression [31].

Notably, different chemokines may play different roles in different stages of liver fibrosis. For example, in the early stage of acute liver injury, CCL2/CCR2-mediated inflammatory cell recruitment may be beneficial for clearing necrotic cells and promoting tissue repair; however, in the chronic injury stage, sustained macrophage recruitment may exacerbate fibrosis progression. Therefore, an in-depth understanding of the spatial and temporal regulation patterns of chemokine networks is important for the development of targeted therapeutic strategies [32].

Role of macrophages in liver repair

Macrophages play complex and critical regulatory roles in liver injury repair. Increasing evidence suggests that macrophages not only are involved in the inflammatory response but also play a central role in tissue repair and regeneration. This reparative role is achieved mainly through the regulation of inflammation, promotion of hepatocyte regeneration, and participation in ECM remodelling, among many other processes. In the early stage of liver injury repair, macrophages promote hepatocyte proliferation and regeneration through the secretion of cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α. These factors can activate signalling pathways such as STAT3 and NF-κB to induce hepatocytes to enter the cell cycle [33]. In addition, macrophages secrete hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which directly promote hepatocyte survival and proliferation [34]. Researchers have reported that macrophage clearance significantly reduces liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy, highlighting its importance in liver repair. In terms of ECM (ECM) remodelling, the role of macrophages is even more complex. On the one hand, macrophages can directly participate in ECM degradation through the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), especially MMP-9 and MMP-13, which play important roles in fibrotic matrix degradation [35]. On the other hand, macrophages can also regulate the process of ECM degradation and maintain the balance of ECM remodelling by secreting tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) [36].

Notably, macrophages at different times may have very different effects on ECM remodelling. During fibrosis progression, proinflammatory macrophages mainly secrete factors such as TGF-β and PDGF, which promote hepatic stellate cell activation and collagen deposition, whereas during fibrosis regression, macrophages shift to secrete MMPs, which promote ECM degradation [37]. The regulatory mechanism of this functional switch and its clinical significance in liver repair are becoming hot research topics. Recent studies have also shown that macrophages play important roles in promoting revascularization and tissue remodelling. By secreting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other angiogenic factors, macrophages can promote hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cell repair and neovascularization, which are important for maintaining the homeostasis of the liver microenvironment [38].

Therapeutic strategies for cirrhosis that target macrophage mechanisms

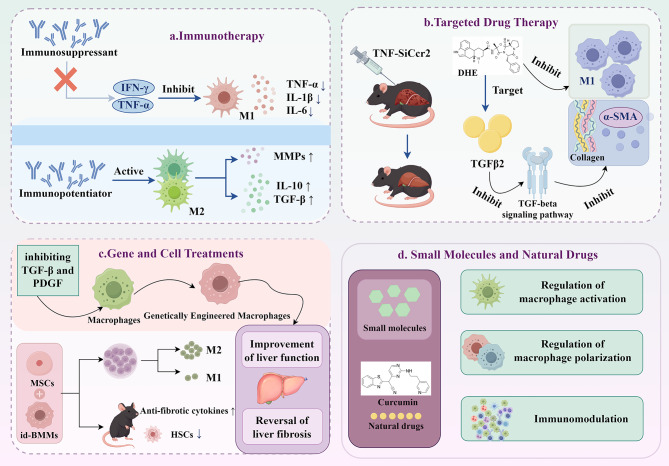

Application of immunosuppressants and immune enhancers

Immunotherapy has begun to receive widespread attention as an important research direction in the treatment of cirrhosis. The regulation of macrophage polarization is particularly important in the treatment of cirrhosis. Macrophages exert different immune effects by receiving different microenvironmental signals and polarizing towards the M1 or M2 phenotype. M1-type macrophages are usually proinflammatory and promote inflammatory responses and injury in the liver through the secretion of cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. In contrast, M2-type macrophages exert anti-inflammatory effects and promote liver repair and fibrosis reversal. Therefore, targeting macrophage polarization has become a new strategy for the treatment of liver cirrhosis [39–41].

Immunosuppressants play important roles in regulating the polarization state of macrophages, especially in inhibiting the activity of M1-type macrophages. By applying immunosuppressive agents, e.g., by blocking the relevant signalling pathways involving TNF-α or IFN-γ, the inflammatory response triggered by M1-type macrophages can be attenuated, which effectively reduces liver injury [42, 43]. For example, preclinical studies have shown that the activity of M1-type macrophages can be inhibited and fibrosis attenuated in cirrhosis models by antibodies targeting TNF-α [44]. Immunopotentiators, on the other hand, play a protective role by promoting the polarization of M2-type macrophages, which help liver repair and regeneration through the secretion of anti-inflammatory factors such as IL-10 and TGF-β, as well as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which promote ECM remodelling [45]. For example, IL-4 and IL-13 significantly promote the M2-type polarization of macrophages, which in turn reduces the progression of liver fibrosis [46]. In addition, some small-molecule drugs, such as natural products like curcumin and steroids, have shown potential in modulating macrophage polarization to the M2 type and have significant inhibitory effects on liver fibrosis [47]. Although good results have been demonstrated in several preclinical studies by modulating macrophage polarization, several challenges remain for practical application. Macrophage polarization status is regulated by a variety of factors, such as cytokines, chemokines, and the immune microenvironment of the liver [48]. These factors play different roles in different stages of liver injury, making it difficult to achieve significant therapeutic effects in clinical practice by means of simple targeted polarization.

Drug-targeted therapy

In recent years, targeting the receptors and signalling pathways of macrophages has become an emerging direction in the treatment of cirrhosis. Macrophages play a crucial role in the liver immune microenvironment, and targeting their receptors and associated signalling pathways can modulate their polarization state and thus influence the course of liver fibrosis. For example, drugs targeting the C-C chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2)/CCL2 axis have attracted attention, and studies have shown that CCR2 small interfering RNA (siRNA) vectors (e.g., tetrahedral framework nucleic acid, tFNA) can effectively target macrophages and attenuate liver fibrosis [49]. A tFNA-siCcr2 complex has been shown to significantly ameliorate hepatic fibrosis in a mouse model while restoring immune cell homeostasis and reducing the accumulation of profibrotic macrophages. Another study revealed that dihydroergotamine (DHE) attenuates hepatic fibrosis by targeting TGFβR2 and inhibiting TGFβ signalling. DHE effectively inhibits the expression of hepatic fibrosis-associated genes, such as collagen and α-SMA, and reduces macrophage infiltration in the liver [50]. These findings provide a new target for the treatment of liver fibrosis.

Clinical studies have begun to explore several therapeutic strategies targeting macrophage receptors. For example, inhibitors targeting the TGFβ receptor are already in the clinical stage and have shown potential to improve liver fibrosis [51]. In addition, clinical studies are testing compounds such as the small-molecule CCR2 inhibitor cenicriviroc, which has been shown to reduce macrophage recruitment and attenuate liver inflammation [52]. However, these therapeutic approaches still face numerous challenges, including issues of target specificity and side effects. For example, while the inhibition of the TGFβ signalling pathway slows the fibrotic process, prolonged inhibition may lead to the oversuppression of the immune system; thus, finer regulatory strategies are needed [53].

Gene therapy and cell therapy

Genetically engineered macrophages have emerged as a promising research area in the treatment of liver cirrhosis. The modification of macrophages by genetic engineering, especially by transducing key factors that inhibit liver fibrosis (e.g., TGF-β and PDGF), can significantly improve the process of liver fibrosis. Studies have shown that genetic engineering to modify the cytokine production pattern of macrophages can facilitate the hepatic repair process [54, 55]. In addition, several studies have shown that macrophages genetically engineered to enhance endogenous regenerative responses in the liver, for example, by modulating the immune microenvironment, help attenuate the inflammatory response associated with cirrhosis [56].

The combined application of stem cell therapy with macrophages is an important breakthrough in the current treatment of liver cirrhosis. Combination therapy with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and bone marrow-derived macrophages (id-BMMs) induced by colony-stimulating factor-1 has been shown to effectively reduce the degree of fibrosis in a mouse model of liver cirrhosis [57]. This combination therapy has also been shown to exert a potent reparative effect by inducing M2 polarization of macrophages in an in vitro culture system. An in vivo study revealed that combination therapy not only significantly reduces liver fibrosis but also enhances hepatocyte proliferation and promoted liver regeneration [58]. The combined application of MSCs and macrophages has shown promising therapeutic potential through different mechanisms, such as promoting the secretion of antifibrotic cytokines and enhancing the apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells. The combined application of stem cells and macrophages not only promotes the reversal of fibrosis but also improves liver function through immunomodulatory mechanisms [59]. For example, researchers have reported that BM-MSCs promote Ly6Chi to Ly6Clo macrophage polarization in the liver through the secretion of cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10, thereby effectively attenuating liver fibrosis [60].

The role of small-molecule drugs in regulating macrophage function

Small-molecule drugs and natural products show great promise in regulating macrophage function because of their unique mechanisms of action and good bioaccessibility. In recent years, studies have shown that a variety of small-molecule compounds and natural products affect the activation state, polarization, and immunomodulatory functions of macrophages through different mechanisms, thus demonstrating significant potential in the treatment of liver fibrosis.

In terms of small-molecule drugs, the development of drugs targeting macrophages has focused on several key signalling pathways. In particular, JNK inhibitors (e.g., CC-930) have been shown to have significant antifibrotic effects in preclinical studies, effects that are closely related to the ability of JNK inhibitors to inhibit the activation of proinflammatory macrophages [61]. By inhibiting the proinflammatory response of macrophages, JNK inhibitors effectively slow the progression of liver fibrosis. Another class of small-molecule drugs is inhibitors that target Galectin-3. The role of Galectin-3 in macrophage activation, polarization, and fibrosis has been extensively studied. Studies have shown that Galectin-3 inhibitors can attenuate the progression of liver fibrosis by regulating the activation state of macrophages. Galectin-3 is not only involved in the macrophage polarization process but also affects the expression of fibrosis-related genes and regulates the immune microenvironment of the liver [62].

Natural products exhibit unique advantages in regulating macrophage function. Many natural products play important roles in antifibrotic therapy by modulating the polarization state of macrophages as well as the immune response. Curcumin, one of the most widely known natural products, can effectively attenuate the polarization of M1-type macrophages and promote the transformation of M2-type macrophages by inhibiting the NF-κB signalling pathway, thereby suppressing excessive inflammatory responses and promoting liver repair [63, 64]. The anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin have been demonstrated in preclinical studies of a variety of liver diseases. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) from green tea is also a potent natural product that affects macrophage function by modulating STAT3 signalling, reducing the secretory effect of M1-type macrophages and promoting the formation of M2-type macrophages [65]. Those effects highlight the potential of EGCG in antifibrotic therapy, especially in the modulation of hepatic immune responses. Additionally, soy isoflavones exert anti-inflammatory effects on the body by inactivating the NF-κB or MAPK signalling pathways in macrophages [66]. In addition, some traditional Chinese medicine compounds and their active ingredients have shown promising results with regard to the regulation of macrophage function. For example, silymarin attenuates liver injury by regulating oxidative stress in macrophages [67]. By modulating the expression of inflammatory factors in macrophages, Ginkgo biloba extract has been shown to have antifibrotic effects [68]. Furthermore, Zhang et al. also reported that tanshinone IIA (Tan IIA) regulates the polarization state of macrophages and promotes liver repair [69] (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Regulatory mechanisms of macrophages

Conclusion and future perspectives

The central regulatory role of macrophages in the pathogenesis and progression of cirrhosis has become increasingly prominent as the understanding of the hepatic immune microenvironment has advanced. This review summarizes the multiple roles of macrophages in the development of cirrhosis and their regulatory mechanisms and discusses the current status and challenges of therapeutic strategies targeting macrophages. Through their unique plasticity and diversity, macrophages perform complex regulatory functions at different stages of liver fibrosis. Studies have shown that the polarization state of macrophages, the chemokine network, and their interactions with other cells together constitute a sophisticated regulatory network [70]. This complex regulatory mechanism provides multiple potential targets for the development of novel therapeutic strategies but also poses challenges in terms of therapeutic precision and specificity.

There have been several positive advances in therapeutic strategies targeting macrophages. A variety of therapeutic options, ranging from immunomodulation to small-molecule drug development, have shown promise in preclinical studies and early clinical trials. In particular, the results of clinical studies with drugs such as CCR2/CCR5 antagonists have provided important support for the feasibility of this therapeutic strategy [71, 72]. However, further studies are still needed to improve the specificity of treatment, ensure the safety of long-term medication use, and overcome the challenges posed by individual heterogeneity [73, 74]. In conclusion, breakthroughs may come from the following areas. First, new technologies, such as single-cell sequencing, can be used to characterize the function of macrophage subpopulations in depth and provide new targets for precision therapy [75]. Second, the development of novel drug delivery systems may improve the targeting and safety of treatment [76]. Finally, combination therapy strategies have been explored to optimize treatment regimens for different stages of liver fibrosis [77]. Although the therapeutic strategy of targeting macrophages still faces many challenges, its application in the treatment of liver cirrhosis is promising.

Notably, in recent years, treatment strategies for liver cirrhosis have gradually shifted from macrolevel anti-inflammatory approaches to precision modulation targeting the immune microenvironment. Among these, macrophage-centric therapeutic strategies have achieved significant breakthroughs, advancing from proof-of-concept to clinical implementation. Researchers are no longer confined to broad immunosuppression but are focusing on reshaping macrophage functional phenotypes to synergize antifibrotic effects with tissue repair; this includes guiding macrophage polarization towards a reparative phenotype by modulating metabolic reprogramming [78, 79] or epigenetic modifications [80–82]. Additionally, engineered macrophage therapies have demonstrated potential in oncology [83], offering a technical pathway for liver cirrhosis treatment—particularly for targeted delivery and long-term regulation within highly heterogeneous microenvironments. In the future, overcoming the limitations of traditional molecular targeting by developing intervention strategies with enhanced spatiotemporal specificity and more precise cell-type targeting is urgently needed. For instance, integrating artificial intelligence [84] to predict patient-specific macrophage response patterns for guiding personalized combination therapies is likely to become a core direction for next-generation treatments. Simultaneously, defining key biomarkers—such as specific macrophage subpopulation profiles [85]—for patient stratification and treatment response evaluations will be a critical challenge in achieving clinical precision medicine. These efforts not only hold promise for providing new pathways to reverse fibrosis in cirrhosis patients but also may redefine the theoretical framework and practical paradigm of immunotherapy for chronic liver disease.

Acknowledgements

The material in all the pictures of this article was provided friendly by Figdraw.

Abbreviations

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- NK

Cells natural killer cells

- IFN-γ

Interferon-γ

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- NO

Nitric oxide

- MMPs

Metalloproteinases

- HGF

Hepatocyte growth factor

- IGF-1

Insulin-like growth factor 1

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- TIMPs

Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

- tFNA

Tetrahedral framework nucleic acid

- DHE

Dihydroergotamine

- MSCs

Mesenchymal stem cells

- id-BMMs

Bone marrow-derived macrophages

- EGCG

Epigallocatechin gallate

- Tan IIA

Tanshinone IIA

Author contributions

Shihao Zheng: Writing – original draft. Size Li: Writing – review & editing, Software, Validation, Visualization. Qiuyue Wang: Writing – review & editing, Software, Validation. Xiaobin Zao: Data curation, Methodology. Xiaoke Li: Software, Validation. Wenying Qi: Writing – review & editing. Fane Cheng: Software, Validation. Yuexiao Geng: Data curation, Methodology. Peng Zhang: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Xinyue Shi: Writing – review & editing, Software, Validation. Yongan Ye: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This work was supported by Pilot Program for Enhancing Clinical Research and Achievement Transformation Capabilities (No. DZMG-ZJXY-23012) and 2025 Beijing University of Chinese Medicine Graduate Student Independent Research Projects (No. DZMYJS2025010).

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Shihao Zheng, Size Li and Qiuyue Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Shihao Zheng, Email: zz94080266@163.com.

Xinyue Shi, Email: sxy199656@163.com.

Yongan Ye, Email: yeyongan@vip.163.com.

References

- 1.Jia, He, Zhang. Long Non-coding RNAs regulating macrophage polarization in liver cancer. Curr Pharm Des. 2024;30:2120–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore, Mackinnon, Wojtacha, Pope, Fraser, Burgoyne, Bailey, Pass, Atkinson, McGowan, et al. Phenotypic and functional characterization of macrophages with therapeutic potential generated from human cirrhotic monocytes in a cohort study. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:1604–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Krenkel, Puengel, Govaere, Abdallah, Mossanen, Kohlhepp, Liepelt, Lefebvre, Luedde, Hellerbrand, et al. Therapeutic inhibition of inflammatory monocyte recruitment reduces steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 2018;67:1270–1283. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Wang, Smith, Hao, He, Kong. M1 and M2 macrophage polarization and potentially therapeutic naturally occurring compounds. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;70:459–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bility, Nio, Li, McGivern, Lemon, Feeney, Chung, Su. Chronic hepatitis C infection-induced liver fibrogenesis is associated with M2 macrophage activation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moroni, Dwyer, Graham, Pass, Bailey, Ritchie, Mitchell, Glover, Laurie, Doig, et al. Safety profile of autologous macrophage therapy for liver cirrhosis. Nat Med. 2019;25:1560–1565. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Schierwagen, Uschner, Ortiz, Torres, Brol, Tyc, Gu, Grimm, Zeuzem, Plamper, et al. The role of macrophage-inducible C-type lectin in different stages of chronic liver disease. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Ju, Tacke. Hepatic macrophages in homeostasis and liver diseases: from pathogenesis to novel therapeutic strategies. Cell Mol Immunol. 2016;13:316–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park, Kim, Lee, Choi, Na. Enhanced stem cell-mediated therapeutic immune modulation with zinc oxide nanoparticles in liver regenerative therapy. Biomaterials. 2025;320:123232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun, Su, Jiao, Wang, Zhang. T cells in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casari, Siegl, Deppermann, Schuppan. Macrophages and platelets in liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1277808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ness, Lin, Gordon. Regulatory dendritic cells, T cell Tolerance, and dendritic cell therapy for Immunologic disease. Front Immunol. 2021;12:633436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu, Galat, Galat, Lee, Wainwright, Wu. NK cell-based cancer immunotherapy: from basic biology to clinical development. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sankar, Pearson, Worlikar, Perricone, Holcomb, Mendiratta-Lala, Xu, Bhowmick, Green. Impact of immune tolerance mechanisms on the efficacy of immunotherapy in primary and secondary liver cancers. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan, Xie, Tan, Li, Gong, He, Li, Chen. Role of Exosomal modulation of macrophages in liver fibrosis. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2024;12:201–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu, He, Yang, Chen, Zhang, Zhong, Chen, Zhong, He, Sun. Paeoniflorin coordinates macrophage polarization and mitigates liver inflammation and fibrogenesis by targeting the NF-[Formula: see text]B/HIF-1α pathway in CCl(4)-Induced liver fibrosis. Am J Chin Med. 2023;51:1249–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu, Liu, Qiu, Yang, Peng. Monotropein attenuates renal cell carcinoma cell progression and M2 macrophage polarization by weakening NF-κB. Int Urol Nephrol. 2025;57:1785–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Igarashi, Wada, Muto, Sone, Hasegawa, Seino. Amelioration of liver fibrosis with autologous macrophages induced by IL-34-based condition. Inflamm Regen. 2025;45:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang, Liu, Yang, Tang, Zhao, Li. Regulation of Concanavalin A-induced immune hepatitis in mice by Dihydromyricetin at the M1/M2 type macrophage level. Discov Med. 2025;37:64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sica, Invernizzi, Mantovani. Macrophage plasticity and polarization in liver homeostasis and pathology. Hepatology. 2014;59:2034–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian, Li, Yang, Chang, Fan, Ji, Xie, Yang, Li. Cannabinoid receptor 1 participates in liver inflammation by promoting M1 macrophage polarization via RhoA/NF-κB p65 and ERK1/2 Pathways, Respectively, in mouse liver fibrogenesis. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li, Zheng, Chen, Wang, Chen, Zou, Liu. Lactobacillus plantarum-Derived inorganic polyphosphate regulates immune function via inhibiting M1 polarization and resisting oxidative stress in macrophages. Antioxid (Basel). 2025;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Xiong, Wang, Zhang, Zhang, Liu, Liu, Wang. Human leukocyte antigen DR alpha inhibits renal cell carcinoma progression by promoting the polarization of M2 macrophages to M1 via the NF-κB pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;144:113706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glim, Niessen, Everts, van Egmond, Beelen. Platelet derived growth factor-CC secreted by M2 macrophages induces alpha-smooth muscle actin expression by dermal and gingival fibroblasts. Immunobiology. 2013;218:924–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun, Zhou, Wu, Li, Huang, Peng. Quercetin promotes the M1-to-M2 macrophage phenotypic switch during liver fibrosis treatment by modulating the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Xu, Ding, Mei, Hu, Kong, Dai, Bu, Xiao, Ding. Dual roles and therapeutic targeting of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor microenvironments. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10:268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, Liang, Kong, Zhang, Qian, Yu, Liu. Therapeutic potential of voltage-dependent potassium channel subtype 1.3 Blockade in alleviating macrophage-related renal inflammation and fibrogenesis. Cell Death Discov. 2025;11:218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang, Wu, Li, Huang, Li, Pan, Li, Huang, Meng, Zhang, et al. PSTPIP2 connects DNA methylation to macrophage polarization in CCL4-induced mouse model of hepatic fibrosis. Oncogene. 2018;37:6119–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varjavand, Hesampour. The role of mesenchymal stem cells and Imatinib in the process of liver fibrosis healing through CCL2-CCR2 and CX3CL1-CX3CR1 axes. Rep Biochem Mol Biol. 2023;12:350–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sasaki, Miyakoshi, Sato, Nakanuma. Chemokine-chemokine receptor CCL2-CCR2 and CX3CL1-CX3CR1 axis May play a role in the aggravated inflammation in primary biliary cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:358–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coombes, Manka, Swiderska-Syn, Vannan, Riva, Claridge, Moylan, Suzuki, Briones-Orta, Younis, et al. Osteopontin promotes cholangiocyte secretion of chemokines to support macrophage recruitment and fibrosis in MASH. Liver Int. 2025;45:e16131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Chen Y, Zhu, Nagashimada W, Nagata X. Cenicriviroc suppresses and reverses steatohepatitis by regulating macrophage infiltration and M2 polarization in mice. Endocrinology. 2024;165. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Noble L, Henson R. Hyaluronate activation of CD44 induces insulin-like growth factor-1 expression by a tumor necrosis factor-alpha-dependent mechanism in murine macrophages. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2368–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiore M, Bayo, Peixoto, Atorrasagasti S. Gómez Bustillo, García, Aquino, Mazzolini. Involvement of hepatic macrophages in the antifibrotic effect of IGF-I-overexpressing mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shapouri-Moghaddam. Mohammadian, Vazini, Taghadosi, Esmaeili, Mardani, Seifi, Mohammadi, Afshari, Sahebkar. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:6425–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sun, Li, Meng, Huang, Zhang. Li. Macrophage phenotype in liver injury and repair. Scand J Immunol. 2017;85:166–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohkubo I. Minamino, Eshima, Kojo, Okizaki, Hirata, Shibuya, Watanabe, Majima. VEGFR1-positive macrophages facilitate liver repair and sinusoidal reconstruction after hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e105533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramachandran, Dobie, Wilson-Kanamori, Dora, Henderson, Luu, Portman, Matchett, Brice, Marwick, et al. Resolving the fibrotic niche of human liver cirrhosis at single-cell level. Nature. 2019;575:512–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Weng W, Xu H, Wang S, Liu Z, Xu, Xu, et al. Repolarization of immunosuppressive macrophages by targeting SLAMF7-Regulated CCL2 signaling sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma to immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 2024;84:1817–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei P, Yuan, Shao W, Guo Z. Polarization of Tumor-Associated macrophages by Nanoparticle-Loaded Escherichia coli combined with Immunogenic cell death for cancer immunotherapy. Nano Lett. 2021;21:4231–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oyarce V-C. Chen, Boerma, Daemen. Re-polarization of immunosuppressive macrophages to tumor-cytotoxic macrophages by repurposed metabolic drugs. Oncoimmunology. 2021;10:1898753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ahmadi D, Mojarad, Taherkhani J, Honardoost G. Effects of micro- and nanoplastic exposure on macrophages: a review of molecular and cellular mechanisms. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2025:1–24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Feng C, Wang, Gao, Chen, Ru, Luo Y, Li L, et al. IL-37 suppresses the sustained hepatic IFN-γ/TNF-α production and T cell-dependent liver injury. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;69:184–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang M, Gong, Guo, Fu, Zhang. Zhou, Li. Macrophage polarization and its role in liver disease. Front Immunol. 2021;12:803037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen H, Wu, Xu, Gong, Chen G. Rubicon promotes the M2 polarization of Kupffer cells via LC3-associated phagocytosis-mediated clearance to improve liver transplantation. Cell Immunol. 2022;378:104556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schenkel M, Swinger, Abo B, Lu C, Kuplast-Barr CK, et al. A potent and selective PARP14 inhibitor decreases protumor macrophage gene expression and elicits inflammatory responses in tumor explants. Cell Chem Biol. 2021;28:1158–e11681113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohammadi B. Barreto, Banach, Majeed, Sahebkar. Macrophage plasticity, polarization and function in response to curcumin, a diet-derived polyphenol, as an Immunomodulatory agent. J Nutr Biochem. 2019;66:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu X, Cai, Li S, Zhang, Lu, Chen, Chen, Li, et al. Single-cell immune profiling of mouse liver aging reveals Cxcl2 + macrophages recruit neutrophils to aggravate liver injury. Hepatology. 2024;79:589–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tian Z, Li, Huang, Guo, Dai, Bai, Tang, Lin G. Liver-Targeted delivery of small interfering RNA of C-C chemokine receptor 2 with tetrahedral framework nucleic acid attenuates liver cirrhosis. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15:10492–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng, Yuan, Dong, Zhang, Jiang Y, Ye, Zhou, Chen J, et al. Dihydroergotamine ameliorates liver fibrosis by targeting transforming growth factor β type II receptor. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:3103–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tacke. Targeting hepatic macrophages to treat liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2017;66:1300–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tacke W. An update on the recent advances in antifibrotic therapy. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12:1143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Avila B. Targeting CCL2/CCR2 in Tumor-Infiltrating macrophages: A tool emerging out of the box against hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;7:293–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shin M, Lee K, Kim, Kim K. Current landscape of adoptive cell therapy and challenge to develop Off-The-Shelf therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;40:791–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li S, Shao, Jin F, Lin, Xiang S. Mesenchymal stem cells attenuate liver fibrosis by targeting Ly6C(hi/lo) macrophages through activating the cytokine-paracrine and apoptotic pathways. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7:239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang, Li, Jiang, Cui Y, Tang. Liu. Ferulic acid combined with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells attenuates the activation of hepatic stellate cells and alleviates liver fibrosis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:863797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watanabe T, Seino, Kawata, Kojima I, Lewis S, Lu, Kikuta K, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and induced bone Marrow-Derived macrophages synergistically improve liver fibrosis in mice. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2019;8:271–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haideri MK, Taylor, Kirkwood S, Lewis. O’Duibhir, Vernay, Forbes, Forrester. Injection of embryonic stem cell derived macrophages ameliorates fibrosis in a murine model of liver injury. NPJ Regen Med. 2017;2:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu Q, Tang Y, Wang, Ye, Zou, Li, Ye Z. Efficacy and safety of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14:301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Su, Wu X. Mesenchymal stem cell-based Smad7 gene therapy for experimental liver cirrhosis. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tapia-Abellán R-A. Antón, Miras-López, Francés, Such, Martínez-Esparza, García-Peñarrubia. Regulatory role of PI3K-protein kinase B on the release of interleukin-1β in peritoneal macrophages from the Ascites of cirrhotic patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;178:525–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang D, Jin, Tang. Zhang. Macrophage in liver fibrosis: identities and mechanisms. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;120:110357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tong W, Gu, Li F, Zeng D. Effect of Curcumin on the non-alcoholic steatohepatitis via inhibiting the M1 polarization of macrophages. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2021;40:S310–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhao C, Liu, Chen, Wu X, Wang, Jia, Li X, et al. Curcumin reduces Ly6C(hi) monocyte infiltration to protect against liver fibrosis by inhibiting Kupffer cells activation to reduce chemokines secretion. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;106:868–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yi Y, Xu, Zhang C, Li W, Dong D, Dong. Zhou. EGCG targeting STAT3 transcriptionally represses PLXNC1 to inhibit M2 polarization mediated by gastric cancer cell-derived Exosomal miR-92b-5p. Phytomedicine. 2024;135:156137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tan, Zhang C. Isoflavones Daidzin and Daidzein inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in RAW264.7 macrophages. Chin Med. 2022;17:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Clichici O, Nagy O, Filip M. Silymarin inhibits the progression of fibrosis in the early stages of liver injury in CCl₄-treated rats. J Med Food. 2015;18:290–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pan L, Li T, Yang, Ruan. Li. Ginkgo Biloba extract EGb761 attenuates Bleomycin-Induced experimental pulmonary fibrosis in mice by regulating the balance of M1/M2 macrophages and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)-Mediated cellular apoptosis. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e922634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang W, Yang, Kou L. Tanshinone IIA alleviate atherosclerosis and hepatic steatosis via down-regulation of MAPKs/NF-κB signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;152:114465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arabpour, Saghazadeh R, Anti-inflammatory. M2 macrophage polarization-promoting effect of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;97:107823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Madan, Verma. Awasthi. Cenicriviroc, a CCR2/CCR5 antagonist, promotes the generation of type 1 regulatory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2024;54:e2350847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ambade, Lowe, Kodys, Catalano, Gyongyosi, Cho, Iracheta-Vellve, Adejumo, Saha, Calenda, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of CCR2/5 signaling prevents and reverses alcohol-induced liver damage, steatosis, and inflammation in mice. Hepatology. 2019;69:1105–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Machado D. Pathogenesis Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Gastroenterol. 2016;150:1769–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Watson, Paul, Rahman, Amir-Zilberstein, Segerstolpe, Epstein, Murphy, Geistlinger, Lee, Shih, et al. Spatial transcriptomics of healthy and fibrotic human liver at single-cell resolution. Nat Commun. 2025;16:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Li H, Wang W. Dynamics of liver cancer cellular taxa revealed through single-cell RNA sequencing: advances and challenges. Cancer Lett. 2024;611:217394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kumar, Xin, Ma T, Osna M. Therapeutic targets, novel drugs, and delivery systems for diabetes associated NAFLD and liver fibrosis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;176:113888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou, Li, Liang, Liu L. Combination therapy based on targeted nano drug co-delivery systems for liver fibrosis treatment: a review. J Drug Target. 2022;30:577–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sacks, Baxter, Campbell, Carpenter, Cognard, Dippel, Eesa, Fischer, Hausegger, Hirsch, et al. Multisociety consensus quality improvement revised consensus statement for endovascular therapy of acute ischemic stroke. Int J Stroke. 2018;13:612–632. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Bian N, Zhou, Tong, Dai, Zhao, Qiang, Gao X. Ubiquitin-specific protease 1 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma progression by modulating mitochondrial fission and metabolic reprogramming via cyclin-dependent kinase 5 stabilization. Cell Death Differ. 2024;31:1202–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ha W, Zhang Y. Interplay between gut microbiome, host genetic and epigenetic modifications in MASLD and MASLD-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2024;74:141–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xue Q, Liu G, Tan, Xie, Wang Y. Epigenetic regulation in fibrosis progress. Pharmacol Res. 2021;173:105910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen S, Liu, Jiang, Xu. Xiao, Rao, Duo. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wu Q, Zhang Q, Li DSC, Li Q, et al. Dual-Engineered Macrophage-Microbe encapsulation for metastasis immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2024;36:e2406140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gupta K. Perspective of artificial intelligence in healthcare data management: A journey towards precision medicine. Comput Biol Med. 2023;162:107051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chakarov, Lim, Tan, Lim, See, Lum, Zhang, Foo, Nakamizo, Duan, et al. Two distinct interstitial macrophage populations coexist across tissues in specific subtissular niches. Science. 2019;363. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.