Abstract

This study aims to comprehensively evaluate the long-term safety profiles of hedgehog pathway inhibitors (HPIs), sonidegib and vismodegib, which have been approved for basal cell carcinoma but lack extensive real-world safety data. Using the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) data from 2012 to 2024, we analyzed adverse events (AEs) associated with these drugs. Notably, most reports were from North America and Europe, which may result in limited generalizability to other populations. Four disproportionality analysis algorithms (ROR, PRR, BCPNN, MGPS) were employed to identify significant AEs across 25 System Organ Classes (SOCs). Common AEs included muscle spasms, alopecia, and ageusia. Unexpected AEs, such as triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), squamous cell carcinoma, and complete atrioventricular block for sonidegib, and atrophic glossitis, malignant neoplasms of the eye, and deafness for vismodegib, were also detected. Gender differences in AE signals and median time to onset (TTO) of sonidegib and vismodegib (67 interquartile range [IQR] 23.25–174.50 vs. 56 IQR 18.00-161.00 days) were determined. The findings suggest sonidegib and vismodegib show differences in reporting patterns that may inform clinical hypotheses requiring confirmation in prospective studies. This study provides new safety insights for clinicians, and may improve patient safety. However, as a spontaneous reporting system, FAERS cannot establish causal relationships. These findings should therefore be considered hypothesis-generating and warrant further research.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-22083-2.

Subject terms: Drug safety, Clinical pharmacology

Introduction

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common type of skin cancer, accounting for about 80% of all skin cancers1. BCC can occur anywhere on the body, but it typically develops on sun-exposed areas of the skin, such as the face, neck, and arms. BCC rarely spreads to other parts of the body or become fatal, but it can invade nearby tissues or be disfiguring if left untreated1. The hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway plays a crucial role in the development of basal cell carcinoma2. The Hh signaling pathway is a critical regulator of embryonic development and tissue homeostasis and regulates normal cell growth and differentiation. In adults, the Hh pathway remains active at low levels to maintain the balance of cell proliferation and differentiation within tissues, particularly in areas with high stem cell activity3. Aberrant activation of this pathway is implicated in various cancers, including basal cell carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer and medulloblastoma4–8. HPIs, including sonidegib, vismodegib, and glasdegib, primarily target two key components of this pathway: Smoothened (SMO) and Gli transcription factors. By binding to the seven-transmembrane domain of the SMO protein, sonidegib, vismodegib, and glasdegib prevent the activation of the pathway, thereby inhibiting the downstream signaling events that lead to cell proliferation and survival9,10. Gli proteins are transcription factors that regulate the expression of genes involved in cell growth and differentiation. Gli inhibitors GANT-58 and GANT-61 interact with the zinc finger domain of Gli proteins to block the transcriptional program driven by the Hh pathway11.

Vismodegib is a second generation cyclopamine derivative that binds directly to SMO protein to prevent Gli activation12. It was approved in 2012 for the treatment of adults with metastatic basal cell carcinoma, or with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma that has recurred following surgery or who are not candidates for surgery and who are not candidates for radiation, which represents the first Hh signaling pathway targeting agent to gain U.S. FDA approval. The Safety Events in Vismodegib (STEVIE) study in 2017 showed response rates (investigator-assessed) were 68.5% in patients with locally advanced BCC and 36.9% in patients with metastatic BCC13. Clinical trials and observation revealed that the most common adverse reactions (≥ 10%) of vismodegib were muscle spasms, alopecia, dysgeusia, weight loss, fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, decreased appetite, constipation, arthralgias, vomiting, and ageusia14. Sonidegib is a biphenyl carboxamide that interact with SMO in the drug-binding pocket15. Sonidegib was approved in the United States and in the European Union in 2015 for the treatment of locally advanced recurrent BCC following surgery and radiation therapy, or advanced BCC in patients who are not eligible for surgery or radiation therapy16. In November 2018, glasdegib was approved for newly-diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML)10. Therefore, there are currently not enough case reports available for analysis. The most common adverse reactions occurring in ≥ 10% of patients included muscle spasms, alopecia, dysgeusia, fatigue, nausea, musculoskeletal pain, diarrhea, decreased weight, decreased appetite, myalgia, abdominal pain, headache, pain, vomiting, and pruritus17. The post-marketing researches have showed that the three most common AEs of HPIs are muscle spasms, alopecia and dysgeusia15,18. Muscle spasms are the most frequently reported AE in the clinical studies, which were reported in 54% of patients receiving sonidegib in BOLT, 71% of patients with vismodegib in ERIVANCE, and 66% of patients with vismodegib in STEVIE studies13,19–21.

However, comprehensive evaluation of long-term safety profile of HPIs in a large sample is lacking. A real-world pharmacovigilance study of HPIs is necessary. The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System is a public, spontaneous reporting system that contains millions of case reports of AEs, and is valuable for post-marketing surveillance and early detection of side effects of drugs22,23. This study aims to investigate the post-marketing safety profile of the HPIs, and to identify emerging adverse reactions from a real-world perspective.

Results

Descriptive analysis

A total of 8670 AE reports of sonidegib and vismodegib (1020 vs. 7650 reports) were identified from FAERS database from January 2012 to September 2024 after removing duplicates. The general characteristics were presented in Table 1. The number of AE reports associated with sonidegib and vismodegib was much higher in males (54.61% vs. 56.42%) than in females (33.63% vs. 36.88%). Patients were mainly aged > = 65 years old (37.75% for sonidegib, 29.86% for vismodegib). Sonidegib-associated AE reports increased gradually from 2015 to 2023 with a sharp rise in 2024 (n = 449, 44.02%). The number of reports of AEs caused by vismodegib exhibited a gradual increase from 2012, reaching a peak in the year 2017 (n = 1436, 18.31%), followed by a gradual decrease till 2024 (Fig. 1). Notably, 43.14% of sonidegib-related and 51.52% of vismodegib-related AE reports were provided by consumers. The most frequently reported outcomes of sonidegib and vismodegib were other serious medical events (51.89% vs. 42.81%), hospitalization (30.87% vs. 27.54%) and death (12.81% vs. 24.99%). As shown in Table 1, the majority of sonidegib-related AE reports were from the United States (70.00%), followed by other (13.33%), Germany (9.02%) and Italy (7.65%). Top five reported countries of vismodegib were the United States (89.96%), other (4.63%), France (2.08%), Germany (1.01%), Canada (0.93%).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of reports with sonidegib and vismodegib from the FAERS database (Q1 2012 to Q3 2024).

| characteristics | sonidegib | vismodegib |

|---|---|---|

| total | 1020(100%) | 7650(100%) |

| age_yr | 73.00(63.00,83.00) | 72.00(61.00,83.00) |

| age_yrQ | ||

| <18 | 5(0.49%) | 24(0.31%) |

| 18 ~ 65 | 148(14.51%) | 1090(14.25%) |

| >=65 | 385(37.75%) | 2284(29.86%) |

| unknow | 482(47.25%) | 4252(55.58%) |

| Indications | ||

| basal cell carcinoma | 606(58.83%) | 4895(63.87%) |

| small cell lung cancer | 34(0.44%) | |

| squamous cell carcinoma of skin | 31(0.40%) | |

| others | 141(13.69%) | 548(7.15%) |

| basal cell naevus syndrome | 89(1.16%) | |

| product used for unknown indication | 240(23.30%) | 1403(18.31%) |

| congenital anomaly | 42(0.55%) | |

| unknown | 43(4.17%) | 43(0.56%) |

| malignant melanoma | 30(0.39%) | |

| medulloblastoma | 45(0.59%) | |

| neoplasm malignant | 101(1.32%) | |

| skin cancer | 403(5.26%) | |

| Reporter (Top 5) | ||

| Consumer | 440(43.14%) | 3941(51.52%) |

| Pharmacist | 220(21.57%) | 731(9.56%) |

| Physician | 207(20.29%) | 2261(29.56%) |

| unknown | 91(8.92%) | 144(1.88%) |

| Other health-professional | 62(6.08%) | 570(7.45%) |

| Outcomes (Top 5) | ||

| other serious | 316(51.89%) | 1444(42.81%) |

| hospitalization | 188(30.87%) | 929(27.54%) |

| death | 78(12.81%) | 843(24.99%) |

| disability | 17(2.79%) | 70(2.08%) |

| life threatening | 9(1.48%) | 85(2.52%) |

| Reported countries (Top 5) | ||

| United States | 714(70.00%) | 6882(89.96%) |

| other | 136(13.33%) | 354(4.63%) |

| Germany | 92(9.02%) | 77(1.01%) |

| France | 159(2.08%) | |

| Italy | 78(7.65%) | 56(0.73%) |

| Canada | 71(0.93%) | |

| route | ||

| oral | 610(59.80%) | 5584(72.99%) |

| other | 410(40.20%) | 2066(27.01%) |

| sex | ||

| female | 343(33.63%) | 2821(36.88%) |

| male | 557(54.61%) | 4316(56.42%) |

| unknown | 120(11.76%) | 513(6.71%) |

| weight | 70.31(60.00,85.00) | 73.48(62.10,86.26) |

| Year | ||

| 2012 | 69(0.90%) | |

| 2013 | 187(2.44%) | |

| 2014 | 245(3.20%) | |

| 2015 | 8(0.78%) | 402(5.25%) |

| 2016 | 22(2.16%) | 591(7.73%) |

| 2017 | 25(2.45%) | 1401(18.31%) |

| 2018 | 69(6.76%) | 794(10.38%) |

| 2019 | 77(7.55%) | 745(9.74%) |

| 2020 | 69(6.76%) | 692(9.05%) |

| 2021 | 71(6.96%) | 635(8.30%) |

| 2022 | 109(10.69%) | 694(9.07%) |

| 2023 | 121(11.86%) | 667(8.72%) |

| 2024 | 449(44.02%) | 528(6.90%) |

Fig. 1.

The annual distribution of HPIs-related reports of adverse events (AEs) from Q1 2012 to Q3 2024.

Basal cell carcinoma was the most reported indication for sonidegib (n = 606, 58.83%), followed by product used for unknown indication (n = 240, 23.30%), others (n = 141, 13.69%) and unknown (n = 43, 4.17%). Top five indications of vismodegib were basal cell carcinoma (n = 4895, 63.87%), product used for unknown indication (n = 1403, 18.31%), others (n = 548, 7.15%), skin cancer (n = 403, 5.26%) and neoplasm malignant (n = 101, 1.32%). All indications listed above are standardized terms according to Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA).

Signal detection

Table 2 describes signal strength and reports of HPIs at the SOC level. The complete dataset was presented in Supplemental Table S1. AEs associated with sonidegib involved 16 SOCs that complied with at least one algorithm as indicated by our statistical analysis, while vismodegib-related AEs involved 25 SOCs. The only SOC of sonidegib met all four algorithms was surgical and medical procedures, with two SOCs of musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders and metabolism and nutrition disorders for vismodegib.

Table 2.

Signal strength of AEs related to HPIs at the system organ class (SOC) level. Signal strength was categorized based on the lower bound of the ROR 95% confidence interval (ROR05): ++ (strong): ROR05 > 2; + (potential): ROR05 > 1; - (no signal): ROR05 ≤ 1. ROR, reporting odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

| Sonidegib | Vismodegib | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOC | Reports | ROR (95% CI) | Signal Strength | Reports | ROR (95% CI) | Signal Strength |

| Surgical and medical procedures | 115 | 3.43 (2.84, 4.14) | ++ | 121 | 0.43 (0.36, 0.51) | - |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 264 | 2.24 (1.97, 2.55) | + | 2771 | 2.84 (2.73, 2.96) | ++ |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 95 | 1.97 (1.60, 2.41) | + | 1024 | 2.52 (2.36, 2.68) | ++ |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 259 | 1.32 (1.16, 1.50) | + | 2556 | 1.56 (1.50, 1.63) | + |

| Investigations | 179 | 1.29 (1.11, 1.50) | + | 1360 | 1.17 (1.10, 1.23) | + |

| renal and urinary disorders | 60 | 1.28(0.99, 1.65) | + | 160 | 0.42(0.36, 0.49) | - |

| cardiac disorders | 58 | 1.16(0.9, 1.51) | + | 194 | 0.4(0.35, 0.47) | - |

| Neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified | 67 | 1.08 (0.85, 1.38) | + | 381 | 0.79 (0.71, 0.87) | - |

| Nervous system disorders | 190 | 0.99 (0.86, 1.15) | - | 2853 | 1.85 (1.78, 1.93) | + |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 383 | 0.86 (0.77, 0.96) | - | 3206 | 0.86 (0.83, 0.89) | - |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 117 | 0.84 (0.70, 1.01) | - | 1941 | 1.81 (1.73, 1.90) | + |

| ear and labyrinth disorders | 6 | 0.56(0.25, 1.26) | - | 88 | 1.01(0.82, 1.24) | + |

| hepatobiliary disorders | 7 | 0.35(0.17, 0.73) | - | 186 | 1.08(0.94, 1.25) | + |

| Other SOCs with weaker or no signals | - | - | ||||

As shown in Supplementary Table S2, the signal detection analysis revealed a total of 45 sonidegib-related preferred terms (PTs) met all four algorithms simultaneously with 56 effective PTs of vismodegib. Musculoskeletal and connective tissue events, skin and subcutaneous tissue events, and nervous system events that are listed in the label are usually reported in patients treated with HPIs. As shown in Table 3, most common AEs associated with sonidegib included muscle spasms (n = 127, 15.14%), alopecia (n = 72, 8.58%), therapy cessation (n = 50, 5.96%), ageusia (n = 42, 5.01%), product dose omission issue (n = 41, 4.89%). Table 4 demonstrated vismodegib-related AEs were mainly muscle spasms (n = 1870, 21.57%), alopecia (n = 1264, 14.58%), ageusia (n = 930, 10.73%), fatigue (n = 862, 9.94%), dysgeusia (n = 678, 7.82%). The unexpected significant signals of sonidegib and vismodegib were also identified (12 vs. 21 signals). For sonidegib, TNBC (n = 8, ROR 383.82, 95% CI 190.08–775.01.08.01) was the novel AE with the strongest signals. In addition, other unexpected significant AEs such as chronic gastritis, gastric ulcer, oesophagitis, atrioventricular block complete, duodenal ulcer, squamous cell carcinoma, acute myeloid leukaemia, febrile neutropenia, hyperkalaemia, hypercalcaemia, and dehydration were discerned. For vismodegib, the unexpected significant AEs included atrophic glossitis (n = 8, ROR 244.06, 95% CI 117.6–506.48.6.48), malignant neoplasm of eye (n = 11, ROR 141.62, 95% CI 76.98–260.55.98.55), squamous cell carcinoma, madarosis, neutrophil count decreased, anosmia, deafness, hypophosphatemia, embolism, ulcer haemorrhage, actinic keratosis, metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, ectropion, haematological infection, blood electrolytes decreased, dehydration, ocular neoplasm, neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin, nasal neoplasm, hyposmia, and ingrown hair.

Table 3.

Signal strength of top 20 sonidegib-associated AEs at the preferred term (PT) level in FAERS database. The unexpected AEs are marked with bold font and asterisks. ROR, reporting odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PRR, proportional reporting ratio; χ2, chi-squared; IC, information component; IC025, the lower limit of 95% CI of the IC; EBGM, empirical bayesian geometric mean; EBGM05, the lower limit of 95% CI of EBGM.

| sonidegib | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOC | PT | Case Reports | ROR (95% CI) |

PRR(95% CI) | χ2 | IC(IC025) | EBGM (EBGM05) |

| musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | muscle spasms | 127 | 18.61(15.56, 22.26) | 17.66(14.8, 21.07) | 1999.9 | 4.14(3.88) | 17.64(15.19) |

| skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | alopecia | 72 | 8.05(6.37, 10.18) | 7.84(6.2, 9.92) | 430.99 | 2.97(2.63) | 7.83(6.44) |

| surgical and medical procedures | therapy cessation* | 50 | 19.02(14.37, 25.17) | 18.63(14.16, 4.51) | 834.25 | 4.22(3.82) | 18.61(14.72) |

| nervous system disorders | ageusia | 42 | 46.3(34.11, 62.85) | 45.49(33.9, 61.04) | 1822.93 | 5.5(5.07) | 45.36(35.13) |

| injury, poisoning and procedural complications | product dose omission issue* | 41 | 3.25(2.39, 4.43) | 3.21(2.39, 4.31) | 62.88 | 1.68(1.24) | 3.21(2.48) |

| metabolism and nutrition disorders | decreased appetite | 39 | 4.16(3.03, 5.7) | 4.1(3, 5.61) | 91.89 | 2.04(1.59) | 4.1(3.15) |

| investigations | blood creatine phosphokinase increased | 39 | 48.53(35.35, 66.63) | 47.75(34.9, 65.34) | 1779.98 | 5.57(5.12) | 47.6(36.51) |

| investigations | weight decreased | 38 | 3.49(2.53, 4.8) | 3.45(2.52, 4.72) | 66.24 | 1.78(1.33) | 3.44(2.63) |

| musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | myalgia | 37 | 5.96(4.3, 8.24) | 5.88(4.3, 8.05) | 150.12 | 2.55(2.09) | 5.88(4.48) |

| nervous system disorders | dysgeusia | 33 | 12.13(8.6, 17.11) | 11.98(8.59, 16.72) | 332.17 | 3.58(3.09) | 11.97(8.98) |

| surgical and medical procedures | therapy interrupted* | 28 | 9.09(6.26, 13.2) | 9(6.2, 13.06) | 199.2 | 3.17(2.64) | 8.99(6.58) |

| general disorders and administration site conditions | disease progression | 25 | 5.47(3.69, 8.11) | 5.42(3.66, 8.02) | 90.21 | 2.44(1.88) | 5.42(3.89) |

| musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | muscular weakness | 21 | 5.06(3.29, 7.78) | 5.02(3.26, 7.73) | 67.78 | 2.33(1.72) | 5.02(3.51) |

| neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified (incl cysts and polyps) | malignant neoplasm progression | 19 | 4.33(2.75, 6.79) | 4.3(2.74, 6.75) | 48.17 | 2.1(1.47) | 4.3(2.95) |

| nervous system disorders | taste disorder | 19 | 19.51(12.42, 30.65) | 19.36(12.33, 30.39) | 330.57 | 4.27(3.64) | 19.34(13.25) |

| blood and lymphatic system disorders | febrile neutropenia* | 17 | 6.45(4, 10.4) | 6.41(4, 10.26) | 77.7 | 2.68(2.01) | 6.41(4.3) |

| general disorders and administration site conditions | therapeutic product effect incomplete | 15 | 3.94(2.37, 6.55) | 3.92(2.35, 6.53) | 32.74 | 1.97(1.26) | 3.92(2.57) |

| investigations | blood creatinine increased | 10 | 4.42(2.37, 8.22) | 4.4(2.35, 8.24) | 26.32 | 2.14(1.28) | 4.4(2.62) |

| metabolism and nutrition disorders | dehydration* | 9 | 4.02(2.09, 7.75) | 4(2.09, 7.64) | 20.27 | 2(1.1) | 4(2.31) |

| neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified (incl cysts and polyps) | triple negative breast cancer* | 8 | 383.82(190.08, 775.01) | 382.51(188.89, 774.61) | 2970.14 | 8.54(7.59) | 373.24(207.31) |

Table 4.

Signal strength of top 20 vismodegib-associated AEs at the preferred term (PT) level in FAERS database. The unexpected AEs are marked with bold font and asterisks. ROR, reporting odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PRR, proportional reporting ratio; χ2, chi-squared; IC, information component; IC025, the lower limit of 95% CI of the IC; EBGM, empirical bayesian geometric mean; EBGM05, the lower limit of 95% CI of EBGM.

| vismodegib | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOC | PT | Case Reports | ROR (95% CI) | PRR (95% CI) | χ2 | IC(IC025) | EBGM (EBGM05) |

| musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | muscle spasms | 1870 | 33.6(32.03, 35.25) | 30.5(29.33, 31.72) | 52797.1 | 4.91(4.84) | 30.1(28.92) |

| skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | alopecia | 1264 | 18.88(17.83, 19.99) | 17.73(16.72, 18.8) | 19870.73 | 4.14(4.06) | 17.6(16.78) |

| nervous system disorders | ageusia | 930 | 137.57(128.57, 147.2) | 131.11(123.62, 139.05) | 113440.28 | 6.95(6.86) | 123.87(117.05) |

| general disorders and administration site conditions | fatigue | 862 | 3.28(3.07, 3.52) | 3.18(3, 3.37) | 1308.07 | 1.67(1.57) | 3.18(3) |

| nervous system disorders | dysgeusia | 678 | 29.58(27.38, 31.95) | 28.59(26.43, 30.92) | 17844.45 | 4.82(4.71) | 28.24(26.48) |

| investigations | weight decreased | 659 | 7.46(6.9, 8.06) | 7.24(6.69, 7.83) | 3549.07 | 2.85(2.74) | 7.22(6.76) |

| metabolism and nutrition disorders | decreased appetite | 631 | 8.21(7.59, 8.89) | 7.98(7.38, 8.63) | 3855.66 | 2.99(2.88) | 7.96(7.45) |

| gastrointestinal disorders | constipation | 354 | 5.07(4.56, 5.63) | 5(4.53, 5.51) | 1133.25 | 2.32(2.17) | 4.99(4.57) |

| general disorders and administration site conditions | no adverse event | 223 | 3.71(3.25, 4.24) | 3.68(3.21, 4.22) | 436.15 | 1.88(1.69) | 3.68(3.29) |

| nervous system disorders | taste disorder | 209 | 31.61(27.56, 36.26) | 31.28(27.27, 35.88) | 6044.25 | 4.95(4.75) | 30.86(27.52) |

| musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | myalgia | 186 | 3.47(3.01, 4.01) | 3.45(3.01, 3.96) | 324.12 | 1.79(1.58) | 3.45(3.05) |

| neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified (incl cysts and polyps) | squamous cell carcinoma* | 100 | 41.21(33.8, 50.25) | 41(33.7, 49.88) | 3832.75 | 5.33(5.05) | 40.28(34.12) |

| metabolism and nutrition disorders | dehydration* | 71 | 4.74(3.69, 6.09) | 4.7(3.64, 6.06) | 181.03 | 2.23(1.87) | 4.7(3.81) |

| skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | madarosis* | 49 | 10.5(7.93, 13.91) | 10.48(7.97, 13.79) | 418.1 | 3.38(2.98) | 10.43(8.25) |

| investigations | neutrophil count decreased* | 47 | 3.48(2.61, 4.64) | 3.48(2.59, 4.67) | 82.81 | 1.8(1.39) | 3.47(2.73) |

| nervous system disorders | hypogeusia | 43 | 75.65(55.81, 102.56) | 75.49(56.26, 101.29) | 3057.12 | 6.19(5.76) | 73.05(56.63) |

| nervous system disorders | anosmia* | 43 | 12.67(9.39, 17.11) | 12.65(9.43, 16.97) | 458.68 | 3.65(3.23) | 12.58(9.79) |

| ear and labyrinth disorders | deafness* | 31 | 3.63(2.55, 5.17) | 3.63(2.55, 5.17) | 58.99 | 1.86(1.36) | 3.63(2.7) |

| hepatobiliary disorders | hepatotoxicity | 30 | 4.28(2.99, 6.12) | 4.27(3, 6.08) | 75.09 | 2.09(1.58) | 4.27(3.16) |

| investigations | lymphocyte count decreased* | 29 | 4.49(3.12, 6.46) | 4.48(3.09, 6.5) | 78.33 | 2.16(1.64) | 4.48(3.3) |

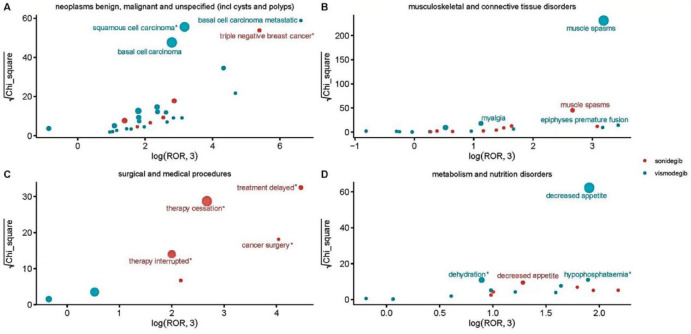

Figure 2 details comparison of the predominant PTs between sonidegib and vismodegib in the four most important SOCs. The PTs of vismodegib predominated in the three SOCs: musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders, metabolism and nutrition disorders, and neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified (incl cysts and polyps), while AEs associated with sonidegib dominated the SOC of surgical and medical procedures.

Fig. 2.

Signal strength of preferred terms (PTs) within the most significant System Organ Classes (SOCs). Red dots represent PTs related to sonidegib, while green dots represent PTs related to vismodegib. The size of the dots represents the number of reports. The unexpected adverse events are marked with asterisks. ROR, reporting odds ratios.

Onset time of events

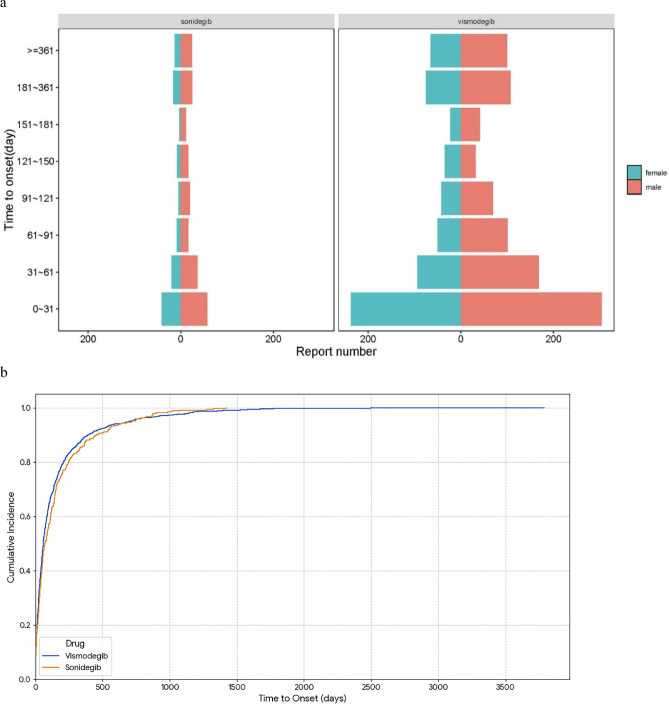

Excluding inaccurate, missing, or unknown reports of TTO, a total of 1870 AEs (321 for sonidegib, 1549 for vismodegib) reported onset time. The median TTO was determined to be 67 days for sonidegib (IQR 23.25–174.50 days), compared with 56.50 days for vismodegib (IQR 18.00–161.00.00.00 days). As illustrated in Fig. 3a, most of AEs associated with sonidegib and vismodegib occurred within the first (30.84% vs. 34.99%), second month (17.45% vs. 17.04%) and third month (7.79% vs. 9.88%) after treatment. The number of AE reports gradually decreased over time. Notably, in 11.53% of sonidegib cases and 10.72% of vismodegib cases, AEs could still occur even after 1 year of treatment with HPIs. Figure 3b illustrates that vismodegib-associated adverse events, on average, tend to have a shorter time-to-onset and accumulate more rapidly over the initial and intermediate treatment periods compared to sonidegib.

Fig. 4.

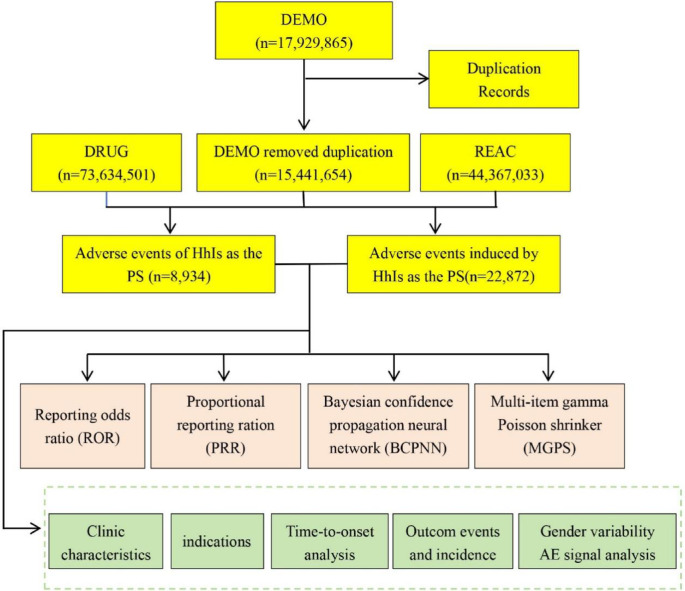

The flowchart of searching and analyzing HPIs-associated adverse events from FAERS database.

Fig. 3.

(a) Time-to-onset (TTO) of HPIs-related adverse events (AEs). (b) Cumulative incidence of adverse events related to sonidegib and vismodegib over time.

Subgroup analyses

To further investigate gender differences in HPIs-related AEs, we performed the gender-based subgroup analysis. Full results were shown in the Supplementary Table S3 and Table S4. As expected, the number of reports and incidence of the significant AEs were notably higher in males than in females. Our results revealed that the most significant AEs included muscle spasms, alopecia and ageusia in patients receiving vismodegib and sonidegib regardless of gender. Additionally, the risks of muscle spasms, alopecia and ageusia are significantly elevated when receiving vismodegib compared to sonidegib. The novel significant gender-specific signals of HPIs were detected as follows: TNBC, atrioventricular block complete, sepsis, localized infection, and urinary tract infection were more likely to occur in females, with acute myeloid leukaemia, weight decreased and gastrointestinal disorders such as gastric ulcer gastritis, duodenal ulcer being more prevalent in males with sonidegib. After receiving vismodegib, females were more prone to develop atrophic glossitis, cholestasis, and acute hepatitis, while males were more commonly affected by metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, hip fracture, and deafness (Supplementary Table S4).

In order to assess the relationship between age and AEs associated with HPIs, we divided the AE reports into three subgroups based on age: children (aged < 18 years), adult (aged 18–65 years), and elderly (aged > 65 years). In patients with sonidegib, the occurrence of ageusia, dyspepsia, gastritis and localized infection was more prevalent in the adult group than in the elderly group. Decreased appetite, urinary tract infection, therapy interrupted, sepsis and 20 other AEs were found to be more common in the elderly group of sonidegib. In patients with vismodegib, high-risk AEs associated with children included epiphyses premature fusion, asthenia, and death. Adult are more prone to develop dehydration, embolism, pneumonitis during vismodegib treatment. The elderly were more commonly affected by cholestasis, anosmia, duodenal ulcer, acute hepatitis, B-cell lymphoma and deafness (Supplementary Table S5).

Discussion

Our study expands the safety profile of HPIs vismodegib and sonidegib by searching and analyzing the real-world data from a large population. Overall, sonidegib displays a relatively higher safety profile with lower risk of AEs, partly due to differences of pharmacokinetics between the two HPIs9. Recent drug approvals of the two drugs (2012 for vismodegib, 2015 for sonidegib) mean limited real-world patient exposure time. This prevents capture of rare or very late-onset AEs in FAERS, as insufficient time has passed for them to occur and be reported, leading to an incomplete safety profile. To overcome this inherent limitation and build a more complete safety profile, ongoing pharmacovigilance and long-term observational studies are essential. As SMO inhibitors, sonidegib and vismodegib have similar demographic characteristics. More reports from male patients and patients aged > = 65 were expected, which is consistent with BCC epidemiological research24. More indications were observed in patients with vismodegib than in patients with sonidegib, which are associated with multiple clinical trials of vismodegib7. This disparity introduces potential confounding by indication and reporting biases that must be considered when comparing their safety profiles. As shown in Table 1, our study was predominantly comprised of reports from the United States and Europe. Extrapolating these findings to global populations should be done with extreme caution. Moreover, a substantial proportion of adverse event reports (23.30% for sonidegib and 18.31% for vismodegib) in FAERS lacked a specified indication for drug use. This missing information poses a significant challenge to the interpretation of our findings, as it is undetermined if the drug usage in these instances was appropriate, in the right dosages, or abused. Notably, about a half of reports of HPIs in this study were submitted by consumers, which can introduce bias into the analysis results. Supplementary Table S6 revealed that FAERS reporting rates of AEs were significantly lower than clinical trial incidence, suggesting that there is a significant under-reporting in FAERS for these highly prevalent AEs. It is recommended that clinicians proactively counsel patients on expected AEs, manage symptoms to improve quality of life and adherence, and regularly assess at visits.

The results of this study indicated that AEs associated with sonidegib involved fewer SOCs than those of vismodegib (16 vs. 25 SOCs). Further disproportionality analysis showed that sonidegib had fewer AEs and a lower incidence of most AEs compared with vismodegib, which aligns with previous research19,20,25. It is important to note that spontaneous reporting systems like FAERS are primarily hypothesis-generating and cannot establish definitive causal relationships between drug exposure and reported AEs. Findings from clinical studies suggest that the three most common AEs of HPIs are muscle spasms, alopecia and dysgeusia15,18. The mechanisms of muscle spasms caused by HPIs are not yet fully understood, which are hypothesized to occur because of calcium influx into the muscle cells. Studies have reported that noncanonical Hh signaling promotes the opening of plasma membrane calcium channels in muscle cells26,27. Therefore, calcium channel blocker amlodipine can greatly reduce occurrence of muscle spasms in patients treated with vismodegib28. Other studies suggest that increased actin expression may play a significant role in the occurrence of muscle spasms related to HPIs29. Muscle spasms can be relieved by dose reduction or interruption of HPIs, massage, heating, stretching and gentle exercise15,30.

HPIs-induced alopecia, manifesting as gradual hair thinning, has a longer onset time compared with hair loss induced by chemotherapy9. The Hh signaling pathway is a critical regulator of hair follicle development and cycling. Inhibition of Hh signaling pathway blocks transition to anagen phase in the hair follicle after hair shedding in telogen phase, resulting in hair thinning and alopecia31. The alopecia is reversible, but regrowth takes many months32. In addition to alopecia, vismodegib could cause a variety of skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders, such as hair growth abnormal, hypotrichosis, and unexpected AEs, including madarosis, actinic keratosis, and ingrown hair. Sonidegib exhibited fewer AEs, fewer report numbers, and lower signal intensity, implying that sonidegib may pose a lower risk in skin and subcutaneous tissue.

Taste disturbance (dysgeusia and ageusia) is among the most common AEs associated with HPIs25. The mechanisms by which HPIs induce taste disturbances are Hh pathway blockade leads to disruptions in taste papillae, taste buds and neurophysiological taste function33. After stopping Hh pathway inhibition, taste buds and sensory responses recover33,34. Nutritional management and using vismodegib at a reduced dose with milder side effects could make oral Hh pathway inhibition treatment more tolerable35,36. At the PT level, we identified a number of unexpected AEs involving the sensory organs, such as eye, ear, nose, and tongue. Further studies showed that vismodegib exhibited stronger toxicity than sonidegib to special sensory organs. Hh pathway has been reported to be a modulator of development and maintenance of special sensory organs, including eye, ear, and nose37–39. It is remarkable that atrophic glossitis was found to be the unexpected AE of vismodegib with the strongest signal, which occurs almost exclusively in females (Supplementary Table S4). This finding represents a exploratory signal with strong biological plausibility, aligning with the known class effects of HPIs on taste bud loss and taste disturbance. While the biological rationale is strong, FAERS data cannot definitively prove causation. Therefore, this signal warrants further confirmation through more studies. It is necessary for clinicians to pay more attention to the AEs involving sensory organs in patients receiving vismodegib.

Unexpected neoplasm-related AEs after sonidegib treatment included TNBC, squamous cell carcinoma, acute myeloid leukaemia, and vismodegib was associated with malignant neoplasm of eye, squamous cell carcinoma, metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, ocular neoplasm, neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin, nasal neoplasm. The mechanisms of secondary malignancies post HPIs therapy are still uncertain. The possible mechanisms may involve inhibition of Hh signaling pathway leads to alternative activation of the RAS-MAPK pathway, thereby driving tumor growth and enhancing metastatic behavior40. Studies have demonstrated that canonical Hh signaling contributes to TNBC growth and metastatic spread by enhancing tumor angiogenesis41. Moreover, administration of sonidegib reduces xenograft proliferation and vascularization in TNBC angiogenesis by inhibiting Hh signaling42. Furthermore, the EDALINE study (GEICAM/2012-12) is a phase Ib clinical trial investigating sonidegib in combination with docetaxel in triple-negative advanced breast cancer patients, suggesting that some of those patients already had TNBC when they received sonidegib43,44. This supports the explanations of reverse causality. The Hh pathway plays a critical and complex role in eye development, maintenance, and various ocular diseases. Both inhibition and activation of Hh signaling can result in eye abnormalities45–48. This is a possible mechanism for the occurrence of malignant neoplasms of the eye after treatment with vismodegib. Although our data imply the potential of HPIs to induce or promote second primary malignancies, it is illogical to determine whether second primary tumors are caused by HPIs only by AE signals due to the limitations of this study. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted as preliminary signals rather than definitive evidence. The identified potential drug-adverse event pairs warrant further rigorous research using study designs capable of assessing causality. Early recognition of neoplasm-related AEs is essential because these AEs may be life-threatening.

It is noteworthy that the long-term use of sonidegib was associated with a risk of complete atrioventricular block, which appears to occur only in females. In contrast, the relevant SOCs for vismodegib did not include cardiac disorders, suggesting that vismodegib seems to have better cardiac safety. This finding may have particularly clinical preventive significance for females with cardiac disorders.

Our study indicated that the majority of AEs associated with sonidegib and vismodegib occurred within 3 months (56.07% vs. 61.91%), with the highest incidence in the first month (30.84% vs. 34.99%). Vismodegib caused adverse events earlier than sonidegib (56 vs. 67 days). It is crucial to monitor AEs within the first 3 months after HPIs treatment, and sonidegib-treated patients should be observed for longer. A significant limitation of our TTO analysis is the inherent reporting delay between AE occurrence and reporting present in FAERS. This delay means that the calculated TTO reflects the time from drug initiation to the reported onset, not necessarily the actual biological latency. AEs with longer true latencies are disproportionately less likely to be reported, or their reports may be significantly delayed, leading to a potential truncation of the observed TTO distribution. The delay, plus under-reporting of long-latency events, shortens observed TTO making drugs appear to have quicker effects than reality. This biases TTO findings towards acute events and can miss important chronic or late-onset safety signals. Gender differences in AEs associated with HPIs have not been comprehensively investigated before. In our study, males were more likely to experience AEs than females. We identified the unexpected significant gender-specific AEs associated with HPIs such as female-specific TNBC and complete atrioventricular block for sonidegib, as well as female-specific atrophic glossitis for vismodegib. Only children receiving vismodegib were at risk of epiphyses premature fusion and death. Consequently, our findings suggest that it is necessary to monitor the occurrence of AEs in specific population subgroups, especially in children with vismodegib, which is the only subgroup with death reports.

This study has the following limitations: Firstly, FAERS is a spontaneous reporting system, and information collection is not restricted in health care professionals, which may lead to the accumulation of incomplete or inaccurate information. The passive nature of surveillance also results in substantial and non-random underreporting, capturing only a small fraction of all AEs. Serious AEs, those associated with newly marketed drugs, or events receiving significant public attention are disproportionately reported, which can inflate signals for these events while potentially obscuring signals for more common or less severe AEs. Moreover, most reports originated from the United States, potentially limiting the generalizability of our findings and providing an incomplete picture of the drugs’ global safety profile. The differing number of indications and associated clinical trial activities between vismodegib and sonidegib represent a major challenge for direct safety profile comparisons using FAERS data. Vismodegib’s broader therapeutic reach implies exposure to a more diverse and potentially sicker patient cohort, which can inflate its raw adverse event counts and disproportionality signals due to confounding by indication. Indication bias occurs when a drug is administered to patients at high baseline risk for an adverse event, thereby creating a spurious drug-event association or masking a true risk, as the observed effect is actually due to the underlying condition. Secondly, the US FDA does not require a proof of causal relationship when reports are submitted. The results from the FAERS database only represent statistical correlation between a particular drug and the corresponding adverse reaction, so further clinical observations, trials, and studies are needed to determine causality. Thirdly, FAERS database lacks comprehensive details for complete causal or epidemiological analysis. For example, FAERS provides the numerator (i.e., the number of adverse event reports for a drug) but lacks a reliable denominator (i.e., the total number of patients exposed to the drug). Consequently, it is impossible to calculate the incidence rate of an AE49. This inability to quantify frequency precludes any robust risk quantification or meaningful comparison of risks between drugs. Likewise, the absence of a direct control or comparator group (e.g., BCC patients not treated with HPIs or receiving other therapies) limits the ability to contextualize the relative safety of sonidegib and vismodegib. Future studies with active comparators or population-based cohorts are needed to confirm our findings. Furthermore, lacking data on potential confounders, including polypharmacy, comorbidities, and treatment duration means FAERS signals are prone to spurious associations (e.g., confounding by indication, drug-drug interactions), making it hard to determine if the drug itself caused the AE or if other patient factors/medications were responsible. Despite the limitations of the FAERS database, the comprehensive analysis of AEs associated with HPIs in this study lays the ground for the safe usage of HPIs in clinics and further clinical research.

Conclusion

This study provides an overview of HPIs-associated suspected AEs based on real-world data from the FAERS database and reveals divergent reporting patterns between sonidegib and vismodegib. We identified 25 SOCs affected by AEs associated with HPIs, predominantly in general disorders and administration site, musculoskeletal and connective tissue, gastrointestinal and nervous system. The analysis results were consistent with findings of previous observation and clinical trials. Additionally, we discovered unexpected significant AEs, such as second primary malignancies, disorders of special sensory organs, complete atrioventricular block, and so on. HPIs are a novel class of anticancer drugs, and more research is needed to characterize their safety profile.

Methods

Data source

The study was conducted using data from the US FAERS database. It is crucial to recognize that FAERS is a spontaneous reporting system. Reports submitted to FAERS represent suspected associations between drugs and adverse events, not confirmed causal relationships. These data are valuable for generating hypotheses and identifying potential safety signals, but they do not permit the establishment of definitive causality. The adverse event reports linked to HPIs submitted in the FAERS database from Q1 2012 to Q3 2024 were extracted. The generic names (sonidegib, vismodegib) and brand names (Odomzo, Erivedge) were utilized to identify the HPIs-related case reports in the FAERS database. Code for reported role of drugs in AEs were categorized into four forms: primary suspect (PS), secondary suspect (SS), concomitant (C), and interacting (I). Case reports, in which the reporter referred to sonidegib and vismodegib as a “Primary Suspect”, were measured in an attempt to restrict the analysis to those drugs directly suspected of causing the AEs50.

Data cleaning was performed by first aggregating quarterly FAERS files (DEMO, DRUG, REAC). Drug names were mapped to active ingredients, and adverse events were coded to MedDRA Preferred Terms. Subsequently, poor-quality reports were excluded for the following reasons: missing critical data fields, implausible temporal relationships (e.g., event onset before drug initiation), or classification as a non-relevant report. The data deduplication was performed before statistical analysis following the criteria: Data were sorted by CASEID and FDA_DT (or PRIMARYID). Reports with identical CASEID (assigned by initial submitter) were grouped as duplicates. When CASEID were the same, the latest FDA_DT was selected, and when the CASEID and FDA_DT were the same, the higher PRIMARYID was chosen51. For higher precision, additional fuzzy matching on key fields like PATIENT_AGE, PATIENT_SEX, OCUR_DATE (onset date), and PRIMARY_REPORTER_COUNTRY can be used to identify potential duplicates that might have different CASEIDs but refer to the same event reported by different entities (e.g., patient and manufacturer). Duplicates were merged under the master PRIMARYID. The most complete report is retained based on: data richness (e.g., lab results, narrative details), submission source (manufacturer and professional reports prioritized over consumers), and timeliness (newest data supersedes older versions). Reports were included only if the drug of interest was designated as a “primary suspect” agent. To ensure data quality, exclusion criteria were applied to remove unusable or duplicate entries. Reports were excluded for meeting any of the following conditions: (1) lacking a documented AE, (2) absence of any suspect drug, (3) identification as a duplicate, or (4) poor quality due to missing essential information. For missing demographic data (e.g., age, sex), a complete-case analysis approach was adopted, thereby excluding reports with missing values for a specific variable from any analysis that requires that variable. Figure 4 illustrates the entire flow of data processing.

Statistical analysis

Disproportionality analysis was performed to identify potential associations between HPIs and adverse events. Four statistical algorithms were applied: reporting odds ratio (ROR), the proportional reporting ratio (PRR), the Bayesian confidence propagation neural network (BCPNN), and the multi-item gamma Poisson shrinker (MGPS)52–54. The formulas and thresholds for these algorithms are summarized in Table 5. The rationale for employing these methods is to leverage their complementary strengths: frequentist methods (ROR and PRR) offer high sensitivity for initial signal detection, whereas Bayesian methods (BCPNN and MGPS) enhance robustness for rare events and reduce false positives through statistical shrinkage. An AE signal can only be identified when AE signals simultaneously met the four algorithm criteria. Unexpected AEs were defined as any AE not listed in the drug label. For reports listing multiple therapies, primary analysis was carried out based on the drug designated as the “primary suspect” by the reporter. For strong signals, a qualitative review of reports was performed to identify consistent patterns of concomitant medications that might explain or exacerbate the AE. When a zero cell was encountered in the 2 × 2 contingency table, a standard correction of + 0.5 was added to all four cells to facilitate the calculation of ROR and PRR. In contrast, rare event signals were handled more robustly by Bayesian methods (BCPNN/MGPS), which are specifically designed to address low-count data. A signal for a rare event was considered more credible when supported by strong biological plausibility. Conflicting signals were reconciled by emphasizing consistency and plausibility. A signal detected by frequentist but not Bayesian methods was considered weak and preliminary, often due to a low case count insufficient for Bayesian significance. False discovery rate (FDR) control was used to manage the rate of Type I errors (false positives).

Table 5.

Overview of formulas and criteria for disproportionality analysis. a, number of reports containing both the target drugs and target adverse drug events; b, number of reports containing other adverse drug events of the target drugs; c, number of reports containing the target adverse drug events of other drugs; d, number of reports containing other drugs and other adverse drug events; N, the number of reports; ROR, reporting odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; PRR, proportional reporting ratio; χ2, chi-squared; IC, information component; IC025, the lower limit of 95% CI of the IC; E (IC), the IC expectations; V(IC), the variance of IC; MGPS, multi-item gamma Poisson shrinker; EBGM, empirical bayesian geometric mean; EBGM05, the lower limit of 95% CI of EBGM.

| Algorithms | Formulas | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| ROR | ROR = ad/bc | Lower limit of 95% CI > 1, N ≥ 3 |

| 95%CI = eln(ROR)±1.96(1/a+1/b+1/c+1/d)^0.5 | ||

| PRR | PRR = [a(c + d)]/[c(a + b)] | PRR ≥ 2, χ2 ≥ 4, N ≥ 3 |

| χ2 = [(ad-bc)^2](a + b + c + d)/[(a + b)(c + d)(a + c)(b + d)] | ||

| BCPNN | IC = log2a(a + b + c + d)/[(a + c)(a + b)] | IC025 > 0 |

| 95%CI = E(IC) ± 2[V(IC)]^0.5 | ||

| MGPS | EBGM = a(a + b + c + d)/[(a + c)(a + b)] | EBGM05 > 2 |

| 95%CI = eln(EBGM)±1.96(1/a+1/b+1/c+1/d)^0.5 |

The TTO of AEs associated with HPIs was defined as the time interval between the AE onset date in the DEMO file (EVENT_DT) and the date of medication initiation in the THER file (START_DT). We removed data including inaccurate, wrong or missing date inputs55. Reports lacking the necessary data point for a particular analysis were excluded from that specific analysis. For TTO analysis, only reports with valid and complete dates for both drug initiation and adverse event onset were included in TTO calculations. If either the start date, event date, or the derived TTO was missing, ambiguous, or invalid, the report was excluded from the TTO analysis. This approach can introduce selection bias, as reports with complete date information might differ systematically from those with missing dates. Subgroup analyses (e.g., by age or sex) were only performed if the relevant demographic or clinical data for a sufficient number of reports within that subgroup was available and considered reliable. If a subgroup has substantial missing data for the characteristic defining that subgroup, the analysis for that specific subgroup is either not performed or its results are presented with a strong caveat regarding the incompleteness of the data and potential for bias. All data processing and statistical analyses were carried out using Microsoft EXCEL 2019, SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, United States), and R software version 4.4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Z.Z. and D.C. designed this study. Z.Z. and Z.W. executed data searching and statistical analyses. Q.G., X.C. and L.Z. prepared all figures and Tables, and took responsibility for the collection, integrity and accuracy of the data. All the authors contributed to the interpretation of data and the writing and editing of this paper. All the authors approved the final version submitted for publication.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The FAERS is a public database that contains reports of adverse events voluntarily submitted to FDA. The data used in our study are derived from this database, hence ethical approval and patient informed consent are not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Roky, A. H. et al. Overview of skin cancer types and prevalence rates across continents. Cancer Pathog Ther.S294971322400058210.1016/j.cpt.2024.08.002 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Caro, I. & Low, J. A. The role of the Hedgehog signaling pathway in the development of basal cell carcinoma and opportunities for treatment. Clin. Cancer Res. : Off J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res.16, 3335–3339 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jing, J. et al. Hedgehog signaling in tissue homeostasis, cancers and targeted therapies. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther.8, 1–33 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skoda, A. M. et al. The role of the Hedgehog signaling pathway in cancer: a comprehensive review. Bosn J. Basic. Med. Sci.18, 8–20 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma, C. et al. Molecular mechanisms involving the Sonic Hedgehog pathway in lung cancer therapy: recent advances. Front Oncol12, 729088 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Gonnissen, A., Isebaert, S. & Haustermans, K. Hedgehog signaling in prostate cancer and its therapeutic implication. Int. J. Mol. Sci.14, 13979–14007 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girardi, D., Barrichello, A., Fernandes, G. & Pereira, A. Targeting the Hedgehog pathway in cancer: current evidence and future perspectives. Cells8, 153 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawahira, H. et al. Combined activities of Hedgehog signaling inhibitors regulate pancreas development. Development130, 4871–4879 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Migden, M., Farberg, A., Dummer, R., Squittieri, N. & Hanke, C. W. A review of Hedgehog inhibitors sonidegib and vismodegib for treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. J. Drugs Dermatol.20, 156–165 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norsworthy, K. J. et al. FDA approval summary: Glasdegib for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res.25, 6021–6025 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rimkus, T., Carpenter, R., Qasem, S., Chan, M. & Lo, H. W. Targeting the Sonic Hedgehog signaling pathway: review of smoothened and GLI inhibitors. Cancers8, 22 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robarge, K. D. et al. GDC-0449—a potent inhibitor of the Hedgehog pathway. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.19, 5576–5581 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basset-Séguin, N. et al. Vismodegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma: Primary analysis of STEVIE, an international, open-label trial. Eur. J. Cancer (Oxf. Engl.:) 86, 334–348 (2017).) 86, 334–348 (2017). (1990). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.FDA. Labeling-package insert of vismodegib (Erivedge). (2023).

- 15.Jain, S., Song, R. & Xie, J. Sonidegib: mechanism of action, pharmacology, and clinical utility for advanced basal cell carcinomas. OncoTargets Ther.10, 1645–1653 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casey, D. et al. FDA approval summary: sonidegib for locally advanced basal cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res.23, 2377–2381 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.FDA. Labeling-package insert of sonidegib (Odomzo). (2023).

- 18.Cozzani, R. et al. Efficacy and safety profile of vismodegib in a real-world setting cohort of patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma in Argentina. Int. J. Dermatol.59, 627–632 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sekulic, A. et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of vismodegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma: final update of the pivotal ERIVANCE BCC study. BMC Cancer. 17, 332 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dummer, R. et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of sonidegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma: 42-month analysis of the phase II randomized, double-blind BOLT study. Br. J. Dermatol.182, 1369–1378 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dréno, B. et al. Two intermittent vismodegib dosing regimens in patients with multiple basal-cell carcinomas (MIKIE): a randomised, regimen-controlled, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol.18, 404–412 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen, C., Wu, B., Zhang, C. & Xu, T. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: an updated comprehensive disproportionality analysis of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Int. Immunopharmacol.95, 107498 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fusaroli, M. et al. Post-marketing surveillance of CAR-T-cell therapies: analysis of the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) database. Drug Saf.45, 891–908 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basset-Seguin, N. & Herms, F. Update on the management of basal cell carcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol.100, 5750 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dummer, R. et al. Sonidegib and vismodegib in the treatment of patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma: a joint expert opinion. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol.34, 1944–1956 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Girard, E. et al. Occurrence of vismodegib-induced cramps (muscular spasms) in the treatment of basal cell carcinoma: a prospective study in 30 patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.78, 1213–1216e2 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teperino, R. et al. Hedgehog partial agonism drives warburg-like metabolism in muscle and brown fat. Cell151, 414–426 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ally, M. S. et al. Effect of calcium channel Blockade on vismodegib-induced muscle cramps. JAMA dermatol.151, 1132–1134 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teh, N. & Leow, L. J. The role of actin in muscle spasms in a case series of patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma treated with a Hedgehog pathway inhibitor. Dermatol. Ther.11, 293–299 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dummer, R. et al. The 12-month analysis from basal cell carcinoma outcomes with LDE225 treatment (BOLT): A phase II, randomized, double-blind study of sonidegib in patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol.75, 113–125e5 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dessinioti, C., Antoniou, C. & Stratigos, A. J. From basal cell carcinoma morphogenesis to the alopecia induced by Hedgehog inhibitors: connecting the Dots. Br. J. Dermatol.177, 1485–1494 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cantelli, M. et al. Vismodegib-induced alopecia: trichoscopic and confocal microscopy evaluation. Skin. Appendage Disord. 6, 384–388 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumari, A. et al. Hedgehog pathway Blockade with the cancer drug LDE225 disrupts taste organs and taste sensation. J. Neurophysiol.113, 1034–1040 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumari, A. et al. Recovery of taste organs and sensory function after severe loss from hedgehog/smoothened Inhibition with cancer drug sonidegib. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 114, E10369–E10378 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoon, J. Vismodegib dose reduction effective when combined with Itraconazole for the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. JAAD Case Rep.7, 107–109 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Le Moigne, M. et al. Dysgeusia and weight loss under treatment with vismodegib: benefit of nutritional management. Support Care Cancer. 24, 1689–1695 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wall, D. S. et al. Progenitor cell proliferation in the retina is dependent on notch-independent Sonic hedgehog/Hes1 activity. J. Cell. Biol.184, 101–112 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Driver, E. C. et al. Hedgehog signaling regulates sensory cell formation and auditory function in mice and humans. J. Neurosci. : Off J. Soc. Neurosci.28, 7350–7358 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maurya, D. K., Bohm, S. & Alenius, M. Hedgehog signaling regulates ciliary localization of mouse odorant receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, E9386–E9394 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Zhao, X. et al. RAS/MAPK activation drives resistance to Smo inhibition, metastasis, and tumor evolution in Shh pathway-dependent tumors. Cancer Res.75, 3623–3635 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riobo-Del Galdo, N. A., Lara Montero, Á. & Wertheimer, E. V. Role of Hedgehog signaling in breast cancer: pathogenesis and therapeutics. Cells8, 375 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Di Mauro, C. et al. Hedgehog signalling pathway orchestrates angiogenesis in triple-negative breast cancers. Br. J. Cancer. 116, 1425–1435 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martín, M. et al. A phase I study of sonidegib (S) in combination with docetaxel (D) in patients (pts) with triple negative (TN) advanced breast cancer (ABC): GEICAM/2012-12 (EDALINE study). Ann. Oncol.27, vi87 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruiz-Borrego, M. et al. A phase Ib study of sonidegib (LDE225), an oral small molecule inhibitor of smoothened or Hedgehog pathway, in combination with docetaxel in triple negative advanced breast cancer patients: GEICAM/2012–12 (EDALINE) study. Invest. New. Drugs. 37, 98–108 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cavodeassi, F., Creuzet, S. & Etchevers, H. C. The Hedgehog pathway and ocular developmental anomalies. Hum. Genet.138, 917–936 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Todd, L. & Fischer, A. J. Hedgehog signaling stimulates the formation of proliferating müller glia-derived progenitor cells in the chick retina. Dev. (camb Engl). 142, 2610–2622 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qu, J. Y., Xiao, Y. T., Zhang, Y. Y., Xie, H. T. & Zhang, M. C. Hedgehog signaling pathway regulates the proliferation and differentiation of rat meibomian gland epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci.62, 33 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu, M., Chen, X., Liu, H. & Di, Y. Expression and significance of the Hedgehog signal transduction pathway in oxygen-induced retinal neovascularization in mice. Drug Des. Dev. Ther.12, 1337–1346 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang, K., Wang, M., Li, W. & Wang, X. A real-world disproportionality analysis of Tivozanib data mining of the public version of FDA adverse event reporting system. Front. Pharmacol.15, 1408135 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu, S., Hu, W., Chen, M., Xiao, X. & Liu, R. A real-world pharmacovigilance study of FDA adverse event reporting system events for lutetium-177-PSMA-617. Sci. Rep.14, 25712 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shu, Y. et al. Post-marketing safety concerns with secukinumab: a disproportionality analysis of the FDA adverse event reporting system. Front. Pharmacol.13, 862508 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shu, Y. et al. Fluoroquinolone-associated suspected tendonitis and tendon rupture: a pharmacovigilance analysis from 2016 to 2021 based on the FAERS database. Front. Pharmacol.13, 990241 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang, Y. et al. Safety assessment of brexpiprazole: real-world adverse event analysis from the FAERS database. J. Affect. Disord. 346, 223–229 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bate, A. et al. A bayesian neural network method for adverse drug reaction signal generation. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol.54, 315–321 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kinoshita, S., Hosomi, K., Yokoyama, S. & Takada, M. Time-to-onset analysis of amiodarone-associated thyroid dysfunction. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther.45, 65–71 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.