Abstract

Background

Given the limited understanding of how dietary amino acid intake affects metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), we examined the potential relationship between dietary amino acid patterns and the odds of MAFLD in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on participants aged 6 to 18 years with a WHO body mass index (BMI)-for-age z-score ≥ 1. MAFLD diagnosis followed established consensus definitions. Principal component factor analyses were conducted based on eighteen amino acids. Logistic regression models, adjusted for potential confounders, were used to estimate the odds of MAFLD across amino acid profile score quartiles.

Results

A total of 505 (52.9% boys) with mean ± SD age and BMI-for-age-Z-score of 10.0 ± 2.3 and 2.70 ± 1.01, respectively, were enrolled. Three major amino acid profiles were characterized: (1) higher loads by branched chain, lysine, tyrosine, threonine, methionine, histidine, alanine, and aspartic acid; (2) higher loads of proline, serine, glutamic acid, and phenylalanine; (3) higher loads of tryptophan, arginine, glycine, and cysteine. After adjusting for all potential confounders, participants in the highest quartile of the first amino acid profile tended to be associated with increased odds of MAFLD (OR:2.14; 95%CI:0.97–4.77). There was no significant association for the second and third profiles.

Conclusions

These novel data suggest that the amino acid composition of an individual’s diet may modify their odds of MAFLD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12986-025-01023-x.

Keywords: Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, Amino acid, Overweight and obese, Children and adolescents

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) has emerged as a pressing global health concern, with an alarming rise in its prevalence, particularly among overweight and obese children and adolescents [1]. MAFLD is characterized by excessive hepatic fat accumulation in the presence of metabolic disturbances, and it is strongly correlated with an elevated risk of cardiometabolic comorbidities, including insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [2, 3]. Due to its progressive nature, MAFLD can lead to severe liver complications, including fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, underscoring its potential to cause significant long-term morbidity [2]. Despite its growing burden, there is currently no pharmacological treatment specifically approved for MAFLD, emphasizing the critical importance of lifestyle modifications, particularly adopting healthy dietary patterns and increased physical activity, in managing and preventing the disease [4]. Therefore, early detection and preventive strategies are paramount to curbing the long-term health consequences of MAFLD.

Extensive research has examined the relationship between dietary factors, particularly the quality and quantity of carbohydrates and fats, and the risk of hepatic steatosis and its associated metabolic disturbances [5]. More recent studies have begun to explore the role of dietary protein and amino acids in hepatic fat accumulation, with growing evidence suggesting that these macronutrients may influence not only liver function but also broader metabolic pathways [6–8]. In this framework, the emerging body of literature suggests that certain amino acids, including branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), sulfur-containing amino acids (SAAs), and aromatic amino acids (AAAs), might be potentially associated with anthropometric indices changes, insulin resistance, T2DM, hepatic steatosis, and nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases (NALFD) in adults [9–13]. Interestingly, we found that increased dietary intake of BCAAs, particularly leucine, may have detrimental effects on the development of NAFLD in overweight and obese children and adolescents [14]. In this context, it should be noted that amino acids are not consumed independently but rather interact in complex networks that may produce either synergistic or antagonistic effects on health. Such interactions emphasize the need for a holistic approach to dietary analysis rather than focusing on the effects of individual amino acids in isolation. In recent years, factor analysis techniques have gained prominence in nutritional research as an effective tool for identifying dietary patterns that are associated with the risk of chronic diseases [15]. This method enables researchers to gain a more integrated understanding of how dietary components, including amino acids, interact and contribute to disease outcomes [15, 16]. In this context, several studies have investigated the association between dietary amino acid profiles derived from factor analysis and the risk of developing hypertension [17], dyslipidemia [18], and dysglycemia [19] in adults. As a result, it seems that dietary amino acid profiles play an essential role in maintaining and promoting optimal health [20].

Despite this growing body of work, there remains a lack of research exploring the relationship between dietary amino acid profiles and the odds of MAFLD, particularly in pediatric populations. Given the potential role of amino acid metabolism in liver fat accumulation and metabolic dysfunction, there is a clear need for further investigation into how dietary amino acid intake influences the development of MAFLD in overweight and obese children and adolescents. The present study aims to address this gap by examining the association between dietary amino acid intake profiles and the odds of MAFLD in overweight and obese children and adolescents.

Method

Study design and population

This cross-sectional study was conducted between September 2023 and July 2024 as part of an obesity registry focusing on Iranian children and adolescents [21, 22]. To assess the adequacy of the study’s sample size, a post hoc power analysis was performed using G*Power (version 3.1.9.7). The calculation was based on the observed odds ratio (OR = 2.14) for the association between the highest versus lowest quartile of dietary amino acid profile 1 and MAFLD odds, with a total sample size of 505 participants, a MAFLD prevalence of 39%, and an assumed R² = 0.15 to account for shared variance with other covariates. Assuming a significance level (α) of 0.05 and a normally distributed exposure variable (mean = − 0.0016; SD = 1.00418), the resulting statistical power exceeded 99.%. A sensitivity analysis was also conducted across a range of effect sizes (OR = 1.33 to 2.00), using the same model parameters. The analysis confirmed that the study retained adequate power (≥ 80%) to detect even modest associations.

Participants were consecutively recruited from individuals attending outpatient clinics specializing in gastroenterology, hepatology, endocrinology, and nutrition at the Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Tehran. Eligible participants were those aged 7 to 18 years who were classified as overweight or obese, defined as having a body mass index-for-age (BMI-for-age) Z-score of 1 or greater, in accordance with World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines [23]. Exclusion criteria included: (1) a history of medical conditions such as renal or liver diseases (e.g., Wilson’s disease, autoimmune liver disease, hemochromatosis, viral hepatitis), thyroid disorders, or malignancies; (2) use of hepatotoxic or steatogenic medications (e.g., valproate, amiodarone), weight-loss drugs, or appetite suppressants; (3) recent dietary modifications within the past year due to illness or weight-loss interventions; and (4) incomplete responses on the food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) (fewer than 35 items) or reports of dietary intake deemed implausible. Under- and over-reporting of dietary intake was identified by comparing reported energy consumption with estimated energy requirements, with deviations beyond ± 2 standard deviations leading to exclusion, in accordance with Institute of Medicine guidelines [24].

The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee of the National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute (IR.SBMU.NNFTRI.REC.1402.015). Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians, and assent was secured from the participating children.

Anthropometric and clinical assessments

All anthropometric measurements were conducted by trained pediatric nutritionists using standardized protocols. Body weight was recorded with a calibrated Seca scale (Seca, Hamburg, Germany), with a precision of 100 g, while height was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm using a stadiometer. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m²), and BMI-for-age Z-scores were determined based on internationally recognized growth charts [23]. Waist circumference (WC) was measured at the midpoint between the iliac crest and the lowest rib, with a precision of 0.5 cm.

Pubertal status was assessed by a pediatric endocrinologist following the Marshall and Tanner staging criteria, which categorize participants as prepubertal or pubertal based on breast and genital development stages [25, 26]. Physical activity levels were evaluated using the Persian-adapted Modifiable Activity Questionnaire (MAQ), which estimates weekly metabolic equivalent task (MET) hours. This questionnaire has demonstrated high reliability (97%) and moderate validity (49%) among adolescents [27].

Blood pressure was measured manually using a mercury sphygmomanometer with an appropriately sized cuff, following a 15-minute rest period. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were determined using the Korotkoff sound technique, with two readings taken at a one-minute interval, and the average value recorded.

Biochemical assessments

Blood samples were collected between 7:00 and 9:00 AM following an overnight fasting period of 8–10 h. Samples were centrifuged within 30–45 min of collection and analyzed on the same day. Fasting blood sugar (FBS) and triglycerides (TG) were measured using enzymatic colorimetric methods. Total cholesterol (TC) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) were determined using cholesterol esterase and phosphotungstic acid methods, respectively. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was calculated using the Friedewald equation [28].

Liver function was assessed by measuring aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels via enzymatic photometry, while gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) was quantified using enzymatic colorimetric methods. These analyses were conducted using commercially available kits from Delta Darman Inc. (Tehran, Iran), and processed with a Selectra 2 auto-analyzer (Vital Scientific, Spankeren, The Netherlands).

Fasting serum insulin was quantified using the electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) technique, employing Roche Diagnostics kits and a Roche/Hitachi Cobas e-411 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Insulin resistance (IR) was estimated using the Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR), calculated as fasting glucose (mmol/L)×fasting insulin (µU/L))/22.5. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation for all biochemical assessments were maintained at ≤ 5.3%.

Dietary assessment

Dietary intake was assessed using a validated and reliable 147-item semi-quantitative FFQ [29, 30]. Trained nutritionists conducted structured interviews with participants and their parents/guardians to determine the frequency and portion sizes of food items consumed over the past year. When children were unable to recall their dietary intake, their mothers provided responses on their behalf. Portion sizes were primarily determined based on U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) food serving guidelines, such as one slice of bread, one medium apple, or one cup of dairy. For foods not covered in USDA tables, standard household measures (e.g., one tablespoon of beans, one piece of chicken (leg, breast, or wing), or rice servings classified as large, medium, or small) were used and converted into grams and servings. The nutritional composition of food items was derived primarily from USDA Food Composition Tables (FCTs) due to limitations in the Iranian FCT, which lacks comprehensive data on raw foods and beverages. However, traditional Iranian foods, such as Kashk, were referenced from the Iranian FCT.

The dietary intake of amino acids was assessed utilizing the USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference (Release 2019) [31]. This comprehensive database is founded on the chemical analysis of the amino acid composition of over 5,000 food items across a variety of food groups. Each food item listed in the FFQ was assigned values for 18 individual amino acids. The intake of amino acids was calculated by multiplying the frequency of consumption of each food item by its respective amino acid content. Furthermore, we organized the amino acids into six categories based on their chemical structures: branched-chain, aromatic, alkaline, sulfuric, acidic, and alcoholic amino acids.

Assessment of MAFLD

MAFLD was identified based on the presence of hepatic steatosis, which was assessed following an 8- to 10-hour overnight fast, on the day of blood sampling. This assessment was conducted using high-resolution B-mode ultrasonography, performed by a trained radiologist. The examination was carried out with a Samsung Medison SonoAce R3 ultrasound machine, utilizing a 7.5–10 MHz linear transducer. In line with the international expert consensus statement, participants were classified as meeting the criteria for MAFLD if they demonstrated hepatic steatosis in conjunction with a BMI for aze Z-score ≥ 1, as established by the World Health Organization growth standards [3].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics, stratified by MAFLD status. Data normality was assessed using histogram plots and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range), while categorical variables were presented as percentages. Group comparisons were performed using independent t-tests, Mann–Whitney U tests, or Chi-square tests, as appropriate.

To investigate profiles of amino acid intake, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on data from 18 specific amino acids: histidine, arginine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, valine, alanine, aspartic acid, cysteine, glutamic acid, glycine, proline, serine, and tyrosine. The analysis, guided by eigenvalues exceeding 1, the scree plot, and the interpretability of the factors, revealed three distinct profiles. Amino acids with an absolute component loading of 0.3 or above were selected for profiles description; however, it is important to note that all amino acids contributed to the computation of the profiles scores.

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) statistic, which assesses the adequacy of the sample size for factor analysis, registered at 0.76. This result indicates a satisfactory level of appropriateness for conducting the analysis. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was utilized to evaluate the suitability of the correlation matrix for factor analysis, yielding a P value of less than 0.01. Participants’ factor scores were calculated by summing the products of their standardized amino acid intakes and the corresponding factor loadings for each profile. The amino acid profile scores were subsequently treated as categorical variables represented in quartiles within the models. Quartiles of amino acid profile scores were calculated using sample-based percentiles derived from the overall distribution across the entire study population. The scores were not stratified by sex or age in order to maintain equal group sizes and preserve statistical power. Each quartile included approximately one-fourth of the total sample (n ≈ 126 per quartile). Quartile categorization was used to facilitate interpretation of the associations across increasing levels of adherence to each amino acid profile. Potential confounding due to age, sex, and pubertal status was addressed through multivariable adjustment in all regression models.

Logistic regression models were employed to assess associations between dietary amino acids intake and the odds of MAFLD, adjusting for confounders in three models: (1) unadjusted, (2) adjusted for age and sex, and (3) further adjusted for BMI-for-age Z-score, puberty status, triglycerides, HOMA-IR, physical activity, dietary energy intake, fiber intake, and saturated fat intake. To test for linear trends across quartiles, the median value of each quartile was modeled as a continuous variable. To assess potential nonlinear relationships between amino acid profile scores and the odds of MAFLD, we conducted restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression analyses were conducted [32] Three knots were placed at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of the profile score distribution to flexibly model exposure–response associations [32]. The models were adjusted for the same covariates included in Model 3. To evaluate the robustness of the observed associations, we conducted post hoc power analyses for each multivariable logistic regression model using observed effect sizes and sample sizes. Power was calculated assuming a two-sided alpha level of 0.05. The estimated effect size (OR), 95% CI, sample sizes per quartile.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA), with p-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the initial 548 overweight and obese children and adolescents enrolled in the study, 31 participants were excluded due to incomplete data related to anthropometric measurements, dietary information, biochemical analyses, or ultrasound results. Additionally, 12 participants were removed for providing implausible dietary reports, characterized by either over-reporting or under-reporting their food intake. As a result, the final analytical sample comprised 505 participants.

The demographic characteristics of the participants, including those with and without MAFLD, are summarized in Table 1. The prevalence of MAFLD in the study population was 38.8%, corresponding to 196 individuals. Among the study population, 52.9% were male, and 23.4% were prepubertal. The mean age and BMI for age Z-score for the study population were 10.0 ± 2.3 years and 2.87 ± 0.98, respectively. As shown in Table 1, individuals with MAFLD had higher values for age, height, weight, WC, BMI, BMI for age Z-score, insulin, HOMA-IR, TG, liver enzymes, and lower values for HDL-C compared to healthy individuals. No significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of gender, pubertal status, physical activity, exposure to secondhand smoke, FBS, TC, LDL-C, SBP, and DBP. In terms of dietary intake, there were no significant differences between the MAFLD and healthy groups for total energy intake, total carbohydrates, total fats, and total protein (expressed as a percentage of total energy). However, individuals with MAFLD consumed more animal-based proteins and less plant-based proteins compared to the healthy group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants according to metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease status

| Total sample (N = 505) | Without MAFLD (N = 309) | MAFLD (N = 196) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||||

| Age (years) | 10.0 ± 2.3 | 9.7 ± 2.1 | 10.5 ± 2.5 | < 0.01 |

| Gender (Boys, %) | 52.9 | 52.1 | 54.1 | 0.66 |

| Puberty (Prepubertal, %) | 23.4 | 23.2 | 23.5 | 0.96 |

| Weight (Kg) | 49.6 ± 15.0 | 46.2 ± 12.3 | 55.1 ± 17.2 | < 0.01 |

| Height (cm) | 142.2 ± 12.3 | 140.0 ± 11.4 | 145.5 ± 12.9 | < 0.01 |

| Body mass index (Kg/M2) | 24.0 ± 3.8 | 23.1 ± 3.1 | 24.4 ± 4.4 | < 0.01 |

| BMI for age z-score | 2.87 ± 0.98 | 2.72 ± 0.80 | 2.99 ± 0.72 | 0.02 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 83.5 ± 10.6 | 80.9 ± 9.4 | 87.6 ± 10.9 | < 0.01 |

| Passive smoker (%) | 23.8 | 30.4 | 23.9 | 0.13 |

| Physical activity (MET/hour/week) | 8.6 (3.0–20.4.0.4) | 8.9 (2.6–20.4) | 7.5 (3.7–20.4) | 0.89 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 105.0 (97.5–116.0) | 105.0 (95.0–115.0) | 105.0 (100.0–120.0) | 0.26 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 65.0 (60.0–75.0) | 65.0 (60.0–75.0) | 65.0 (60.0–70.0) | 0.84 |

| Biochemical data | ||||

| Fasting serum insulin (mU/mL) | 16.4 ± 8.6 | 15.5 ± 7.9 | 17.8 ± 9.6 | 0.01 |

| Fasting blood sugar (mg/dl) | 91.1 ± 8.7 | 90.6 ± 8.9 | 91.9 ± 8.5 | 0.11 |

| HOMA-IR | 3.73 ± 2.16 | 3.5 ± 1.9 | 4.1 ± 2.3 | 0.01 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 109.5 (81.0–151.5.0.5) | 110.0 (83.0–152.0) | 122.0 (91.0–168.0) | 0.01 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 171.0 ± 55.9 | 172.3 ± 66.8 | 169.2 ± 31.8 | 0.54 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 47.1 ± 11.7 | 49.0 ± 11.6 | 44.0 ± 11.3 | < 0.01 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl) | 98.0 ± 25.5 | 97.3 ± 24.4 | 99.1 ± 27.2 | 0.43 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 16.0 (11.0–22.0) | 15.0 (11.0–19.0) | 18.0 (13.0–32.0) | 0.01 |

| Aspartate amino transferase (U/L) | 23.0 (17.0–29.0) | 22.0 (16.0–28.0) | 25.0 (17.0–32.0) | 0.01 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (U/L) | 17.0 (15.0–21.0) | 16.9 (14.0–19.0) | 19.0 (16.0–24.0) | 0.01 |

| Dietary intake | ||||

| Energy (Kcal/day) | 3046.3 ± 956.3 | 3069.9 ± 998.5 | 3009.1 ± 887.0 | 0.48 |

| Carbohydrate (% of energy) | 56.0 ± 6.2 | 56.1 ± 5.8 | 56.0 ± 3.7 | 0.89 |

| Fat (% of energy) | 31.1 ± 5.8 | 31.0 ± 5.5 | 31.1 ± 3.6 | 0.76 |

| Total protein (% of energy) | 13.4 ± 2.2 | 13.3 ± 2.1 | 13.6 ± 2.3 | 0.10 |

| Animal protein (% of energy) | 7.0 ± 2.5 | 6.7 ± 2.4 | 7.5 ± 2.6 | 0.01 |

| Plant protein (% of energy) | 6.4 ± 1.4 | 6.5 ± 1.5 | 6.2 ± 1.3 | 0.04 |

Significant p-values are highlighted in bold.HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, Low-density lipoprotein

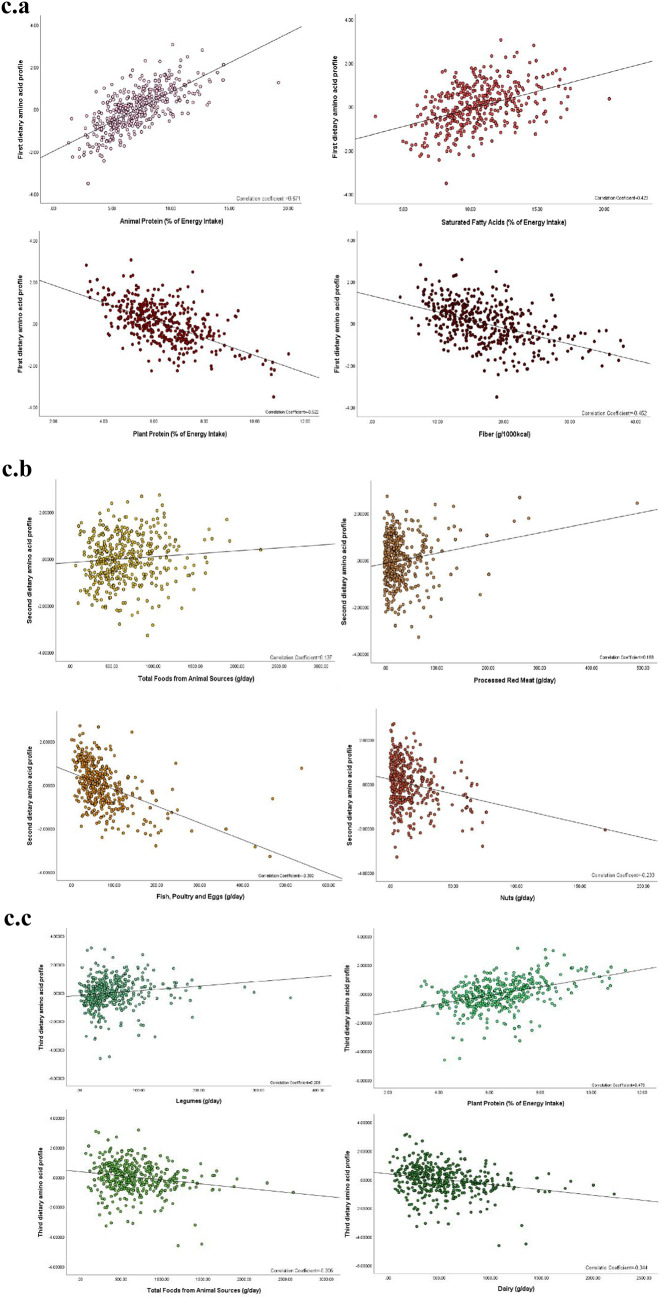

Supplementary Tables 1 and Fig. 1 displays the intake of amino acids, including the daily intake in grams, percentage of total protein intake, percentage of total energy intake, and the sources of amino acids (animal or plant-based). Glutamic acid had the highest intake at 22.04 g per day, while tryptophan had the lowest intake at 1.18 g per day. Glutamic acid alone accounted for 21% of the total amino acid intake, followed by aspartic acid, leucine, proline, and lysine (Fig. 1a). The smallest contributions were made by tryptophan, cysteine, methionine, and histidine. The major sources for most amino acids, such as lysine, methionine, isoleucine, valine, leucine, threonine, histidine, alanine, serine, proline, and phenylalanine, were animal-based proteins, while cysteine, arginine, tryptophan, glycine, aspartic acid, and glutamic acid predominantly came from plant-based sources. Compared to those with MAFMD, healthy individuals had higher intakes of aspartic acid, arginine, and proline, while methionine intake was lower in the healthy group (Fig. 1b). No significant differences were observed for other amino acids between the two groups.

Fig. 1.

Overview of amino acid intake and dietary pattern characteristics. a. The most consumed amino acids in the study population, expressed as a percentage of total dietary protein intake. b. Differences in the intake of specific amino acids between children and adolescents with MAFLD and healthy controls. c. Correlations between principal component-derived amino acid profiles and associated food groups and micronutrient intakes

Three primary dietary amino acid profiles were identified through factor analysis, utilizing eigenvalues greater than one, as indicated by the scree plot (Supplementary Fig. 1). The factor loadings for the amino acids in the extracted profiles are shown in Supplementary Table 2. Three profiles were extracted, explaining 78.8% of the total variance in dietary amino acids. The first profile (eigenvalue = 7.55) had high factor loadings for isoleucine, lysine, tyrosine, leucine, valine, threonine, methionine, histidine, alanine, and aspartic acid. The second profile (eigenvalue = 4.89) was characterized by higher loadings for proline, serine, glutamic acid, and phenylalanine. The third profile (eigenvalue = 1.76) was more loadings for tryptophan, arginine, glycine, and cysteine.

The correlations between the amino acid intake profiles and food groups and micronutrients are presented in Supplementary Tables 3 and Fig. 1c. The first profile showed significant positive correlations with food groups from animal sources, including dairy, red meat, fish, poultry, and eggs, as well as with total protein, animal-based protein, total fat, saturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, calcium, and zinc. Conversely, it showed negative correlations with plant-based food groups, plant-based protein, sodium, and fiber. The second profile was positively correlated with animal-based food groups, processed red meat, grains, plant-based protein, sodium, calcium, zinc, magnesium, and fiber, while negatively correlated with red meat, nuts, fruits and vegetables, animal-based protein, total fat, monounsaturated fatty acids, and polyunsaturated fatty acids. The third profile showed positive correlations with red meat, fish, poultry, eggs, plant-based foods, grains, legumes, nuts, total protein, plant-based protein, sodium, zinc, and magnesium, and negative correlations with animal-based foods, dairy, fruits and vegetables, saturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and calcium.

The demographic characteristics of participants across quartiles of amino acid profiles are presented in Supplementary Table 4. As the first amino acid profile score increased, significant reductions in age, WC, and ALT (P < 0.05) were observed. No significant differences were found across quartiles for the second profile. For the third profile, triglycerides increased, and HDL-C decreased as the quartile score increased (P < 0.05).

The dietary intakes across quartiles of the amino acid profiles are shown in Supplementary Table 5. With increasing quartiles of the first amino acid profile, total protein, animal-based protein, total fat, saturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, calcium, and zinc intake increased (P < 0.05), while total energy intake, plant-based protein, polyunsaturated fatty acids, total carbohydrates, sodium, and fiber intake decreased (P < 0.05). For the second profile, animal-based protein, carbohydrates, sodium, calcium, zinc, magnesium, and fiber intake increased (P < 0.05), while plant-based protein, total fat, and polyunsaturated fatty acids decreased (P < 0.05). The third profile showed increases in total protein, plant-based protein, sodium, zinc, and magnesium (P < 0.05), while animal-based protein, saturated fatty acids, carbohydrates, and calcium intake decreased (P < 0.05).

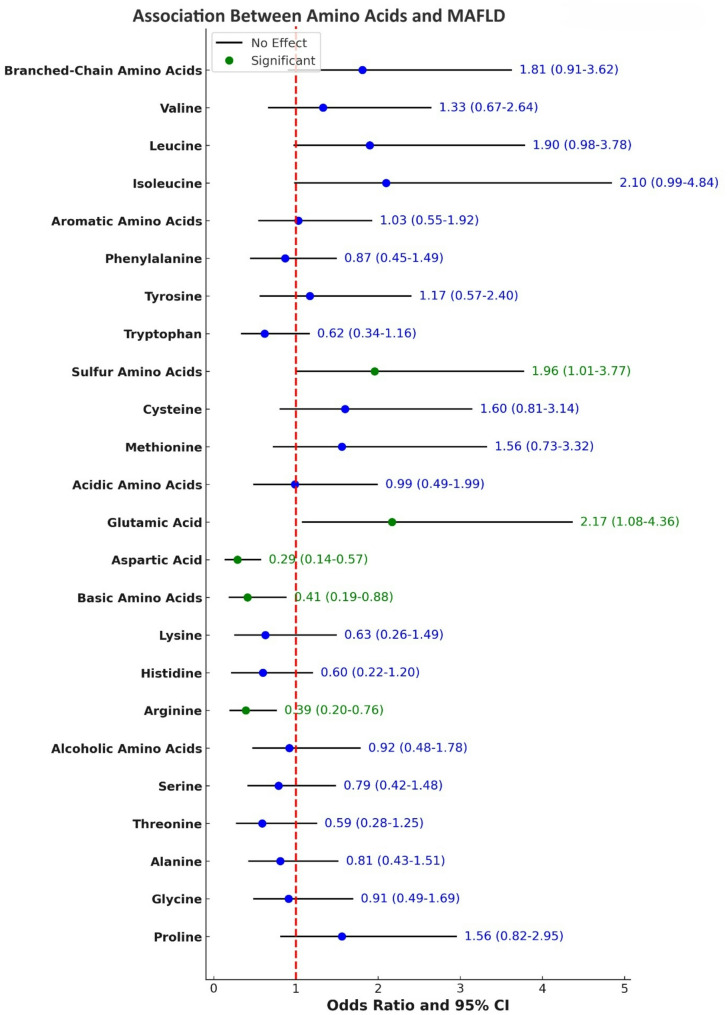

Results from logistic regression analysis for the association between amino acid intake and the odds of developing MAFLD are presented in Supplementary Tables 6 and Fig. 2. After adjusting for confounding factors, the odds of MAFLD were 2.17 times higher in the highest quartile of glutamic acid intake compared to the lowest quartile (OR = 2.17, 95%CI:1.08–4.36; P-trend = 0.05). Moreover, after adjusting for potential confounders, the odds of MAFLD were 71% lower for individuals in the highest quartile of aspartic acid intake (OR = 0.29, 95%CI:0.14–0.57; P-trend = 0.01) and 61% lower for those in the highest quartile of arginine intake (OR = 0.39, 95%CI: 0.20–0.76; P-trend = 0.03).

Fig. 2.

The odds ratio (95% CI) for the association between amino acids intake and the odds of developing MAFLD

The association between dietary amino acid groups and the odds of MAFLD is presented in Supplementary Tables 7 and Fig. 2. After adjusting for confounding variables, individuals in the highest SAAs intake had 96% higher odds of developing MAFLD than those in the lowest quartile (OR = 1.96, 95%CI:1.01–3.77; P-trend = 0.01). Additionally, after adjusting for confounders, individuals in the highest quartile of alkaline amino acid intake had 59% lower odds of MAFLD compared to those in the lowest quartile (OR = 0.41, 95%CI:0.19–0.88; P-trend = 0.90).

The odds of developing MAFLD across quartiles of the amino acid profile scores are provided in Table 2. In the crude model, individuals in the highest quartile of the first dietary amino acid profile had significantly greater odds of MAFLD compared to those in the lowest quartile (OR = 2.21; 95% CI: 1.10–4.44; p = 0.03). This association remained consistent in adjustment Model 1 (OR = 2.30; 95% CI: 1.13–4.70; p = 0.02). In the fully adjusted Model 2, the OR was 2.14 (95% CI: 0.97–4.77; p = 0.06). Although the point estimate remained elevated, this association was no longer statistically significant. However, a significant linear trend was observed across quartiles (P-trend = 0.03), indicating a possible positive relationship between this profile and MAFLD. In continuous analyses, each unit increase in dietary amino acid profile 1 score was associated with a 33% increase in the odds of MAFLD (OR = 1.33; 95% CI: 0.98–1.81; p = 0.06) in the fully adjusted model, though this also did not reach statistical significance. For the second dietary amino acid profile, the odds of MAFLD were higher in the upper quartiles relative to the lowest, but these associations were not statistically significant. In Model 2, the OR comparing Q4 to Q1 was 1.51 (95% CI: 0.81–2.80; p = 0.20), with a P-trend of 0.06. When modeled continuously, the adjusted OR was 1.17 (95% CI: 0.94–1.46; p = 0.16), suggesting a potential positive trend, although the findings did not meet statistical significance. In the analysis of the third dietary amino acid profile, an inverse association with MAFLD was observed across all models. However, this association did not reach statistical significance. In the crude model, individuals in the highest quartile had lower odds of MAFLD compared to those in the lowest quartile (OR = 0.57; 95% CI: 0.29–1.11; p = 0.10). The association remained similar after adjusting for age and sex in Model 1 (OR = 0.59; 95% CI: 0.30–1.16; p = 0.13), and in the fully adjusted Model 2 (OR = 0.62; 95% CI: 0.33–1.53; p = 0.13). When the third dietary amino acid profile score was analyzed as a continuous variable, no statistically significant association with MAFLD was found. The ORs were 0.93 (95% CI: 0.75–1.17; p = 0.56) in the crude model, 0.94 (95% CI: 0.76–1.18; p = 0.62) in Model 1, and 0.95 (95% CI: 0.76–1.19; p = 0.65) in the fully adjusted model.

Table 2.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for the odds of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease according to the proportion of dietary amino acid profiles

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | P-trend | Continues (Per one unit increment |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary amino acid pattern 1 | |||||||

| Number of cases/total population | 45/126 | 46/126 | 48/126 | 57/127 | |||

| Crude model | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.03 (0.61–1.73) | 1.10 (0.66–1.84) | 1.50 (0.90–2.50) | 0.11 | 1.22 (1.01–1.46) | 0.03 |

| Model 1a | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.06 (0.62–1.79 | 1.26 (0.74–2.13) | 1.69 (1.01–2.85) | 0.04 | 1.28 (1.06–1.54) | 0.01 |

| Model 2b | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.92 (0.49–1.75) | 1.64 (0.81–3.31) | 2.14 (0.97–4.77) | 0.03 | 1.33 (0.98–1.81) | 0.06 |

| Dietary amino acid pattern 2 | |||||||

| Number of cases/total population | 44/127 | 42/126 | 54/126 | 56/126 | |||

| Crude model | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.95 (0.56–1.60) | 1.43 (0.86–2.38) | 1.50 (0.90–2.50) | 0.05 | 1.21 (1.01–1.46) | 0.03 |

| Model 1a | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.04 (0.61–1.77) | 1.63 (0.96–2.74) | 1.57 (0.93–2.63) | 0.03 | 1.23 (1.02–1.48) | 0.03 |

| Model 2b | 1.00 (Ref) | 1.13 (0.61–2.09) | 2.01 (1.10–3.65) | 1.51 (0.81–2.80) | 0.06 | 1.17 (0.94–1.46) | 0.16 |

| Dietary amino acid pattern 3 | |||||||

| Number of cases/total population | 53/126 | 48/126 | 48/127 | 47/126 | |||

| Crude model | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.84 (0.51–1.40) | 0.82 (0.49–1.36) | 0.48 (0.33–1.34) | 0.41 | 1.01 (0.84–1.21) | 0.89 |

| Model 1a | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.84 (0.50–1.40) | 0.76 (0.45–1.27) | 0.76 (0.45–1.28) | 0.27 | 0.97 (0.80–1.16) | 0.74 |

| Model 2b | 1.00 (Ref) | 0.71 (0.40–1.26) | 0.69 (0.38–1.24) | 0.62 (0.33–1.53) | 0.13 | 0.95 (0.76–1.1) | 0.65 |

Obtained by Logistic regression analysis.* P-trend was obtained using a quartile of dietary exposure as an ordinal variable in the model.Significant p-values are highlighted in bold.aModel 1 adjusted for age and sex.bModel 2 additionally adjusted for body mass index z-score, pubertal status, triglycerides, Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance, physical activity, energy intake, percentage of total protein intake, fiber intake (grams per 1000 kcal), and saturated fat (percentage of total energy)

To further assess the linearity assumption and explore potential dose-response relationships, we conducted RCS regression using fully adjusted models (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). For the first dietary amino acid profile, the spline curve showed a positive, gradually increasing association with MAFLD odds, supporting the linear trend observed in quartile-based models. The spline for the second dietary amino acid profile suggested a possible threshold effect, with an increase in odds only in the higher percentiles of the score distribution. Dietary amino acid profile 3 displayed a flat and slightly inverse curve across the range of scores, aligning with its non-significant and inverse ORs.

To complement the primary analysis, post hoc power calculations were performed for each pattern using observed ORs (Q4 vs. Q1), case distribution, and sample size. The estimated power for dietary amino acid profile 1 was 78%, reflecting moderate power to detect a statistically significant association. dietary amino acid profile 2 and dietary amino acid profile 3 achieved estimated powers of 70% and 61%, respectively (Supplementary Table 8).

Discussion

This study is the first to comprehensively investigate the association between dietary amino acid profiles and the odds of developing MAFLD among overweight and obese children and adolescents. The study’s findings provide novel insights into how specific dietary amino acid profiles might influence the odds of MAFLD, underscoring the complex interplay between dietary intake, metabolic pathways, and liver health. We identified three distinct dietary amino acid patterns associated with the likelihood of developing MAFLD.

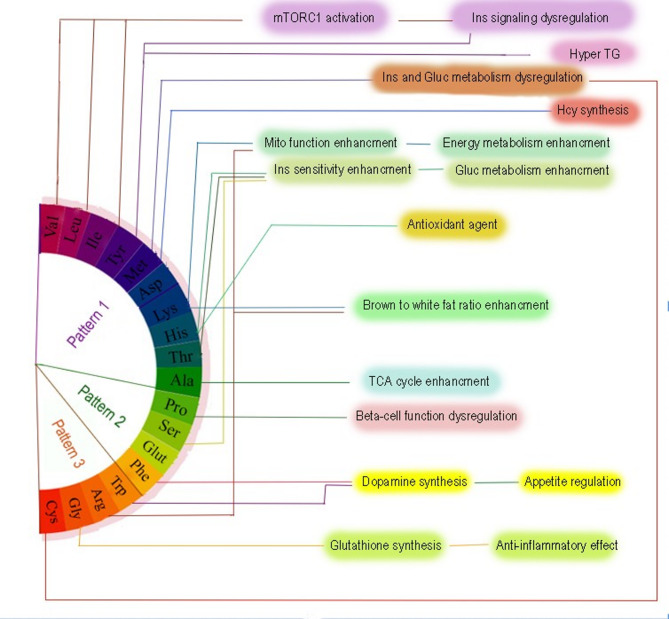

The first dietary amino acid profile, which exhibited a high loading of BCAAs, methionine, tyrosine, lysine, threonine, histidine, alanine, and aspartic acid, showed a significant association with an increased odd of MAFLD. This profile was notably correlated with higher intakes of animal-based protein sources, including dairy, red meat, poultry, fish, and eggs. Additionally, it was positively correlated with total fat intake, including saturated fatty acids and monounsaturated fatty acids, as well as with key micronutrients such as calcium and zinc. Conversely, the first dietary amino acid pattern exhibited negative correlations with plant-based foods and nutrients, such as plant proteins, sodium, and dietary fiber. In the fully adjusted model, individuals in the highest quartile of adherence to the first amino acid profile exhibited 2.14-fold higher odds of developing MAFLD compared to those in the lowest quartile (OR = 2.14; 95% CI: 0.97–4.77; p = 0.06). Although this association did not reach statistical significance, the trend across quartiles was significant (P-trend = 0.03), suggesting a graded and potentially meaningful relationship between the dietary amino acid pattern and MAFLD odds. This finding is supported by power analysis, which indicated adequate statistical power (78%) to detect moderate effect sizes, thus lending additional credibility to the observed trend. When modeled as a continuous variable, the association between dietary amino acid profile 1 score and MAFLD also approached significance (OR = 1.33; 95% CI: 0.98–1.81; p = 0.06), further supporting a potential linear relationship. This was reinforced by the restricted cubic spline analysis, which illustrated a steadily increasing risk of MAFLD with higher dietary amino acid profile 1 scores, consistent with a non-linear yet progressive dose-response association. The significance of these findings becomes apparent when considering the metabolic effects of BCAAs, methionine, and tyrosine, which have been implicated in pathways that promote hepatic fat accumulation, insulin resistance, and dysregulated lipid metabolism [33–35]. Furthermore, the positive correlation with saturated fats and animal proteins suggests that a diet rich in these components may exacerbate the risk of MAFLD through synergistic mechanisms, such as enhanced fatty acid synthesis and impaired insulin signalling [36, 37]. Figure 3 further elucidates the potential mechanisms underlying this dietary amino acid pattern’s association with MAFLD. As depicted in Fig. 3, this pattern is linked to mTORC1 activation, a central regulator of cell growth and metabolism [38]. mTORC1 plays a crucial role in nutrient sensing, and its activation by BCAAs, particularly leucine, has been shown to disrupt insulin signalling and glucose metabolism [33]. The result is a cascade of metabolic disturbances, including hypertriglyceridemia and insulin resistance, which contribute to the development of MAFLD [39]. Moreover, the intake of animal proteins, a hallmark of this pattern, has been associated with promoting inflammatory responses and oxidative stress in the liver, leading to an exacerbation of hepatic fat accumulation and liver injury [40]. Thus, the combination of BCAAs, methionine, and tyrosine, along with a diet high in animal-based proteins and saturated fats, appears to create a metabolic environment conducive to the development of MAFLD. In this regard, a prospective study within the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study framework examined the dietary intake of amino acid patterns and the incidence of dysglycemia [19]. Consistent with the amino acid dietary pattern of our study, one of the dietary patterns extracted in the study by Mirmiran et al. included valine, leucine, isoleucine, tyrosine, methionine, aspartic acid, threonine, alanine, histidine, and serine, which, like our first pattern, was positively correlated with animal sources. The results of this study showed that increased dietary intake of the aforementioned amino acid pattern was associated with a nonsignificant increase in the odds of dysglycemia in adults [19].

Fig. 3.

Mechanistic pathways of dietary amino acids role in developing metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

The second amino acid dietary profile, characterized by higher loads of glutamic acid, proline, serine, and phenylalanine, exhibited mixed associations with MAFLD. While this pattern was positively correlated with food sources rich in animal proteins (such as dairy and processed red meats) and plant-based proteins, as well as with sodium, calcium, zinc, magnesium, and fiber, it was negatively correlated with the intake of fruits, vegetables, and nuts. Interestingly, glutamic acid, a key component of this pattern, strongly correlates with MAFLD odds, supporting previous studies that suggest its role in promoting liver fat accumulation and metabolic dysfunction [41, 42]. However, in the present study, the association between adherence to the second amino acid profile and the odds of MAFLD did not reach statistical significance in the fully adjusted model when comparing the highest to the lowest quartile (OR = 1.51; 95% CI: 0.81–2.80; p = 0.19). Similarly, although the P for trend across quartiles approached significance (P-trend = 0.06), the continuous association in the adjusted model was not significant (OR = 1.17; 95% CI: 0.94–1.46; p = 0.16). Power analyses revealed modest statistical power for detecting associations of this magnitude, which may have limited the ability to identify significant relationships in this pattern. Restricted cubic spline analysis did not indicate a clear non-linear association between dietary amino acid pattern 2 scores and MAFLD odds, suggesting the absence of a strong dose-response trend. The mixed metabolic effects of this pattern highlight the complexity of nutrient interactions and suggest that the detrimental effects of specific amino acids may be mitigated by the intake of other beneficial nutrients. This is particularly relevant when considering the correlations with processed meats and sodium, which may contribute to inflammation and oxidative stress, further exacerbating liver damage [43]. In this regard, in the study by Mirmiran et al., increased dietary intake of an extracted amino acid pattern with a higher load of proline and glutamic acid was associated with a significant 24% increase in the incidence of dysglycemia [19]. Further research involving diverse age groups is essential to conduct a more comprehensive examination of this issue.

The third dietary amino acid profile, characterized by higher intakes of tryptophan, arginine, glycine, and cysteine, was associated with a decreased likelihood of MAFLD. However, this inverse association did not achieve statistical significance in any of the models. Specifically, in the fully adjusted model, individuals in the highest quartile of adherence had lower odds of MAFLD compared to the lowest quartile (OR = 0.62; 95% CI: 0.33–1.53; p = 0.30), but the confidence interval included the null, indicating a non-significant result. The trend across quartiles was also non-significant (P-trend = 0.13), and the association was not statistically significant when modeled as a continuous variable (OR = 0.95; 95% CI: 0.76–1.10; p = 0.65). These findings were further supported by the restricted cubic spline analysis, which did not indicate a significant non-linear dose-response relationship. Post hoc power calculations suggested limited power to detect modest associations for this pattern, possibly contributing to the non-significant results. From a dietary composition standpoint, this dietary amino acid profile was positively correlated with red meat, poultry, fish, and eggs, but it also showed a strong correlation with plant-based foods, including grains, legumes, nuts, and plant proteins. In particular, the intake of arginine, a key amino acid in this pattern, was inversely associated with MAFLD risk, aligning with previous research suggesting that arginine may have hepatoprotective effects [44]. Arginine has been shown to promote nitric oxide production, which helps regulate vascular tone and insulin sensitivity [45]. Furthermore, the positive association with plant-based foods and the negative correlation with saturated fatty acids may confer additional metabolic benefits, supporting the hypothesis that diets rich in plant-based proteins, fiber, and antioxidants may help prevent liver fat accumulation and reduce the risk of insulin resistance. Despite the absence of statistically significant associations in this study, the directionality of the estimates and the nutrient profile of this pattern support its potential protective role. However, further investigations with larger sample sizes and prospective designs are warranted to elucidate these associations more definitively.

The proposed mechanisms in Fig. 3 offer additional insight into the potential benefits of the third dietary amino acid profile. This dietary amino acid profile is associated with several metabolic pathways that promote overall health and may help reduce the risk of MAFLD. Specifically, the amino acids in this pattern are linked to enhanced dopamine synthesis and appetite regulation, which could lead to improved energy balance and reduced fat accumulation [46]. Furthermore, cysteine and glycine, two amino acids in this pattern, are critical precursors for glutathione synthesis, an important antioxidant that helps protect the liver from oxidative damage [47]. The protective effects of this pattern may also be attributed to its anti-inflammatory properties, which are mediated by the amino acids that regulate immune function and reduce hepatic inflammation. However, this association’s lack of statistical significance suggests that additional factors, such as genetic predisposition, environmental influences, or other dietary components, may be at play.

The third extracted amino acid profile showed a higher load of tryptophan, arginine, glycine, and cysteine. In addition, this profile was positively correlated with red meat (weak correlation), poultry, fish, eggs, whole foods from plant sources, grains, legumes, nuts, and plant-based proteins, and negatively correlated with whole foods from animal sources, dairy, and saturated fatty acids. In separate analyses of amino acids in the present study, arginine was significantly associated with reduced odds of MAFLD. It is possible that all of the above factors work synergistically to reduce the odds of developing MAFLD, although this association was not significant in our study.

Our findings highlight the importance of considering dietary amino acid profile, rather than isolated amino acids, in understanding the complex relationship between diet and MAFLD. The interactions between various amino acids and other nutrients may have synergistic or antagonistic effects on liver health, and evaluating these interactions using a holistic approach, such as factor analysis, provides a more comprehensive understanding of their role in disease pathogenesis. Although PCA remains a widely accepted technique for reducing data dimensionality and identifying underlying dietary constructs, future research may also consider applying unsupervised clustering methods such as K-means clustering. These approaches could allow for the identification of mutually exclusive dietary profiles, which may improve interpretability and targeting in public health or clinical interventions. We suggest that comparative analyses using both PCA and clustering methods could enhance our understanding of the relationship between dietary amino acid intake and metabolic health outcomes in population studies. Furthermore, the findings suggest that dietary interventions aimed at modifying amino acid intake patterns, particularly by reducing BCAAs and increasing plant-based proteins, could be an effective strategy in preventing or managing MAFLD in overweight and obese children and adolescents.

Strengths and limitations.

This study possesses several notable strengths that enhance its scientific rigor and relevance. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first to examine the association between dietary amino acid profiles and the odds of MAFLD in the pediatric population, providing new insights into the complex relationship between diet and liver health. Using validated and reliable questionnaires to assess dietary intake and physical activity ensures the robustness of the data. The presence of mothers during face-to-face interviews likely improved the accuracy of dietary recall and intake quantification among child participants. Additionally, all dietary and anthropometric assessments were conducted by trained pediatric dietitians, minimizing the likelihood of data collection errors and increasing the precision of measurements. However, certain limitations should be acknowledged. Due to the cross-sectional design, we cannot determine whether the observed associations between dietary amino acid intake and MAFLD reflect a causal relationship or are influenced by reverse causality. Longitudinal studies are needed to establish temporal relationships, while interventional studies are essential to more definitively assess the potential causal role of specific amino acid profiles in the development of MAFLD. Although a validated FFQ was used, and interviews were conducted by trained nutritionists in the presence of caregivers to enhance accuracy, we acknowledge the possibility of recall bias and the limited temporal resolution inherent in estimating dietary intake over a one-year period. These factors may affect the precision of amino acid intake estimations and should be considered when interpreting our findings. The amino acid composition of food items was derived from the USDA Food Composition Tables due to the limited data available in the Iranian food database. However, differences in livestock feed, food preparation methods, and local agricultural practices may affect the amino acid content of foods consumed in Iran. This introduces a potential limitation in accurately estimating amino acid intake based on region-specific dietary sources. Quartiles of amino acid pattern scores were derived from the overall sample distribution without stratification by sex or age. While this approach ensured balanced group sizes and preserved statistical power, it may not fully capture developmental differences in dietary intake patterns. Although we adjusted for sex, age, and pubertal status in all multivariable models, some residual confounding may still be present. Furthermore, despite adjustments for several confounders, the potential for residual confounding due to unmeasured or unidentified factors cannot be entirely excluded, which may influence the interpretation of the results. Additionally, the lack of data on serum amino acid concentrations restricts the ability to directly assess the correlation between dietary intake and amino acid levels in the body. Finally, as the study focused on overweight and obese children and adolescents, the findings may not be directly generalizable to the normal-weight pediatric population. Future research should address these limitations by incorporating longitudinal designs, serum biomarkers, and a broader range of potential confounders to further explore the causal mechanisms behind these associations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides novel insights into the role of dietary amino acid profiles in the development of MAFLD. The results suggest that specific amino acid profiles, especially those enriched in BCAAs and sulfur-containing amino acids, may increase the odds of MAFLD, while patterns enriched in plant-based proteins, fiber, and amino acids like arginine may offer protective benefits. Further longitudinal studies are needed to validate these findings and elucidate the underlying mechanisms. The integration of dietary amino acid profile analysis into clinical practice could provide valuable tools for the early detection and prevention of MAFLD in pediatric populations.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation to the participants of the study for their enthusiastic support and to the staff of the involved hospitals for their valuable help. This study is taken from the Obesity registry program in children at Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.CHMC. REC.1401.016). We are thankful to Dr. Mohammad Hassan Sohouli and Dr. Afshin Ostovar, head of the obesity registry at Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Author contributions

Overall, GA, PR, and MR, supervised the project and approved the final version of the manuscript to be submitted. GA designed the research; PD assessed the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; PM, ZST, and DB gathered data; AN and MHS analyzed and interpreted the data; AN drafted the initial manuscript; and GA critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Funding

No financial support was provided in any way for this research.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

National nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute (NNFTRI) ethics committee approved the study protocol (IR.SBMU.NNFTRI.REC.1402.015). All participants provided written informed consent and were informed about the study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants adhered to the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Pejman Rohani, Email: rohanipejmanmd@gmail.com.

Golaleh Asghari, Email: g_asghari@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Liu J, Mu C, Li K, Luo H, Liu Y, Li Z. Estimating global prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in overweight or obese children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 2021;66:1604371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pipitone RM, Ciccioli C, Infantino G, La Mantia C, Parisi S, Tulone A, et al. MAFLD: a multisystem disease. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2023;14:20420188221145549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eslam M, Alkhouri N, Vajro P, Baumann U, Weiss R, Socha P, Marcus C, Lee WS, Kelly D, Porta G. Defining paediatric metabolic (dysfunction)-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:864–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li T, Zhao J, Cao H, Han X, Lu Y, Jiang F, Li X, Sun J, Zhou S, Sun Z. Dietary patterns in the progression of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease to advanced liver disease: a prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2024;120:518–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yki-Järvinen H, Luukkonen PK, Hodson L, Moore JB. Dietary carbohydrates and fats in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:770–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pillai RR, Kurpad AV. Amino acid requirements in children and the elderly population. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:S44–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ling Z-N, Jiang Y-F, Ru J-N, Lu J-H, Ding B, Wu J. Amino acid metabolism in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tricò D, Biancalana E, Solini A. Protein and amino acids in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2021;24:96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teymoori F, Asghari G, Hoseinpour S, Roosta S, Bordbar M, Mirmiran P, et al. Dietary amino acids and anthropometric indices: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 2023;67:e000646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asghari G, Farhadnejad H, Teymoori F, Mirmiran P, Tohidi M, Azizi F. High dietary intake of branched-chain amino acids is associated with an increased risk of insulin resistance in adults. J Diabetes. 2018;10:357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okekunle AP, Zhang M, Wang Z, Onwuka JU, Wu X, Feng R, Li C. Dietary branched-chain amino acids intake exhibited a different relationship with type 2 diabetes and obesity risk: a meta-analysis. Acta Diabetol. 2019;56:187–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galarregui C, Cantero I, Marin-Alejandre BA, Monreal JI, Elorz M, Benito-Boillos A, Herrero JI, de la Ruiz-Canela OV, Hermsdorff M. Dietary intake of specific amino acids and liver status in subjects with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: fatty liver in obesity (FLiO) study. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60:1769–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mokhtari E, Ahmadirad H, Teymoori F, Mohammadebrahim A, Bahrololomi SS, Mirmiran P. The association between dietary amino acids and the risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among Tehranian adults: a case-control study. BMC Nutr. 2022;8:155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nikparast A, Razavi M, Sohouli MH, Hekmatdoost A, Dehghan P, Tohidi M, et al. The association between dietary intake of branched-chain amino acids and the odds of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among overweight and obese children and adolescents. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2024;24:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu FB. Dietary pattern analysis: a new direction in nutritional epidemiology. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salehi-Abargouei A, Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L, Keshteli AH, Feizi A, Feinle-Bisset C, Adibi P. Nutrient patterns and their relation to general and abdominal obesity in Iranian adults: findings from the SEPAHAN study. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55:505–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teymoori F, Asghari G, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Dietary amino acids and incidence of hypertension: a principle component analysis approach. Sci Rep. 2017;7:16838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdi F, Mohammadzadeh M, Abbasalizad-Farhangi M. Dietary amino acid patterns and cardiometabolic risk factors among subjects with obesity; a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr Disord. 2024;24:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirmiran P, Bahadoran Z, Esfandyari S, Azizi F. Dietary protein and amino acid profiles in relation to risk of dysglycemia: findings from a prospective population-based study. Nutrients. 2017;9:971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fappi A, Mittendorfer B. Dietary protein intake and obesity-associated cardiometabolic function. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2020;23:380–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rohani P, Ejtahed H-S, Shojaie S, Sohouli MH, Hasani-Ranjbar S, Larijani B, et al. Enhancing childhood obesity management: implementing an obesity registry for Iranian children and adolescents. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2024;23:2395–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikparast A, Sohouli MH, Forouzan K, Farani MA, Dehghan P, Rohani P, Asghari G. The association between total, animal, and plant protein intake and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in overweight and obese children and adolescents. Nutr J. 2025;24:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Organization WH. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and development. In WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and development. 2006.

- 24.Intakes SCotSEoDR I, So I, SoURLo UDRN. Fiber PotDoD, macronutrients po: dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids. National Academies; 2005.

- 25.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45:13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delshad M, Ghanbarian A, Ghaleh NR, Amirshekari G, Askari S, Azizi F. Reliability and validity of the modifiable activity questionnaire for an Iranian urban adolescent population. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warnick GR, Knopp RH, Fitzpatrick V, Branson L. Estimating low-density lipoprotein cholesterol by the Friedewald equation is adequate for classifying patients on the basis of nationally recommended cutpoints. Clin Chem. 1990;36:15–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asghari G, Rezazadeh A, Hosseini-Esfahani F, Mehrabi Y, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Reliability, comparative validity and stability of dietary patterns derived from an FFQ in the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:1109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esfahani FH, Asghari G, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Reproducibility and relative validity of food group intake in a food frequency questionnaire developed for the Tehran lipid and glucose study. J Epidemiol. 2010;20:150–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. Legacy Release [Internet]. Nutrient Data Laboratory, Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center, ARS, USDA [https://agdatacommons.nal.usda.gov/articles/dataset/USDA_National_Nutrient_Database_for_Standard_Reference_Legacy_Release/24661818/1]

- 32.Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. Springer; 2001.

- 33.Zhang F, Zhao S, Yan W, Xia Y, Chen X, Wang W, Zhang J, Gao C, Peng C, Yan F. Branched chain amino acids cause liver injury in obese/diabetic mice by promoting adipocyte lipolysis and inhibiting hepatic autophagy. EBioMedicine. 2016;13:157–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Orgeron ML, Stone KP, Wanders D, Cortez CC, van Gettys NT. TW: Chapter Eleven - The Impact of Dietary Methionine Restriction on Biomarkers of Metabolic Health. In Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. Volume 121. Edited by Tao Y-X: Academic Press; 2014: 351–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Hellmuth C, Kirchberg FF, Lass N, Harder U, Peissner W, Koletzko B, et al. Tyrosine is associated with insulin resistance in longitudinal metabolomic profiling of obese children. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:2108909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Wit N, Derrien M, Bosch-Vermeulen H, Oosterink E, Keshtkar S, Duval C, de Vogel-van den Bosch J, Kleerebezem M, Müller M, van der Meer R. Saturated fat stimulates obesity and hepatic steatosis and affects gut microbiota composition by an enhanced overflow of dietary fat to the distal intestine. Am J Physiology-Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G589–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leamy AK, Egnatchik RA, Young JD. Molecular mechanisms and the role of saturated fatty acids in the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52:165–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ben-Sahra I, Manning BD. mTORC1 signaling and the metabolic control of cell growth. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2017;45:72–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jung UJ, Choi M-S. Obesity and its metabolic complications: the role of adipokines and the relationship between obesity, inflammation, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:6184–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan BL, Norhaizan ME, Liew W-P-P. Nutrients and oxidative stress: friend or foe? Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:9719584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaouche L, Marcotte F, Maltais-Payette I, Tchernof A. Glutamate and obesity - what is the link? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2024;27:70–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maltais-Payette I, Boulet MM, Prehn C, Adamski J, Tchernof A. Circulating glutamate concentration as a biomarker of visceral obesity and associated metabolic alterations. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2018;15:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He K, Li Y, Guo X, Zhong L, Tang S. Food groups and the likelihood of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2020;124:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Dalaen S, Alzyoud J, Al-Qtaitat A. The effects of L-arginine in modulating liver antioxidant biomarkers within carbon tetrachloride induced hepatotoxicity: experimental study in rats. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2016;9:293–8. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Piatti P, Monti LD, Valsecchi G, Magni F, Setola E, Marchesi F, Galli-Kienle M, Pozza G, Alberti KGM. Long-term oral L-arginine administration improves peripheral and hepatic insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:875–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller GD. Appetite regulation: hormones, peptides, and neurotransmitters and their role in obesity. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2019;13:586–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vairetti M, Di Pasqua LG, Cagna M, Richelmi P, Ferrigno A, Berardo C. Changes in glutathione content in liver diseases: an update. Antioxidants. 2021;10:364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.