Abstract

Background

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a significant global public health concern, with prediabetes serving as a critical stage between normoglycemia and DM. Without intervention, individuals with prediabetes face an increased risk of developing DM, underscoring the need for effective preventive measures. The Hemoglobin Glycation Index (HGI)—which measures the discrepancy between actual and predicted glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels—has shown promise in predicting the onset of both microvascular and macrovascular complications associated with DM. However, its potential role in assessing the risk of developing DM or prediabetes remains to be fully established. This study aims to investigate the predictive capacity of HGI for both DM and prediabetes.

Method

This retrospective cohort study utilized data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), involving participants aged 45 years and older who were assessed in 2011 and followed up in 2015. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were employed to analyze the relationship between HGI and the incidence of prediabetes and DM. Dose-response analyses were conducted using restricted cubic splines, and subgroup analyses were performed based on various demographic and health-related factors.

Results

Among 3,963 participants, 187 individuals (4.72%) developed prediabetes within four years, and 107 individuals (2.70%) developed DM. HGI was independently associated with an increased risk of developing both DM and prediabetes, with adjusted odds ratios of 1.61 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.19–2.16, p = 0.001) and 2.03 (95% CI: 1.40–2.94, p < 0.001), respectively. A linear relationship was observed between HGI and both DM and prediabetes. An interaction effect was identified between age and HGI; specifically, the association between higher HGI and incident DM was more pronounced in individuals aged 45 to 60 years. Among this age group, the OR was 3.93 (95% CI: 2.19–7.05, p < 0.001).

Conclusion

HGI is identified as an independent risk factor for both DM and prediabetes, demonstrating its utility in predicting the likelihood of their development, particularly within the population aged 45 to 60. These findings highlight the potential of HGI as a valuable biomarker for the early identification of DM risk, thereby facilitating the formulation of targeted intervention strategies.

Trial registration

Not applicable.

Keywords: Hemoglobin glycation index, Prediabetes, Diabetes mellitus, CHARLS

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) has become a major killer among global public health diseases, posing a serious threat to public health. In 2019, approximately 9.3% of the global population—463 million people—were living with DM, a figure projected to rise to 10.9% by 2045. Concurrently, the number of adults with prediabetes is expected to increase from 374 million in 2019 to 540 million by 2045 [1]. DM is the fifth leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for 11.3% of total deaths in 2019, with a troubling 46.2% of these occurring in individuals under 60 years of age [2], highlighting a concerning trend towards younger mortality. Moreover, DM imposes a significant economic burden, with global costs reaching $1.31 trillion, equivalent to 1.8% of the global GDP [3]. DM is characterized by hyperglycemia resulting from insufficient insulin secretion or action [4]. Insulin, an endocrine peptide hormone, binds to plasma membrane receptors on target cells to facilitate glucose uptake and inhibit hepatic glucose production. Prediabetes is defined as elevated plasma glucose levels that are higher than normal but not high enough to meet the diagnostic criteria for DM; this condition often progresses to DM [5]. Impaired β-cell function and increased insulin resistance (IR) are the primary pathological mechanisms underpinning DM. The prognosis for DM remains poor, largely due to unclear pathophysiological mechanisms. Complications associated with DM—such as diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome [6], retinopathy, renal failure, diabetic foot, and cardiovascular diseases [7]—contribute significantly to this grim outlook. Delays in diagnosis and treatment further exacerbate the prognosis. Thus, improving DM outcomes necessitates a focus on prevention and early intervention. Current diagnostic methods for DM and prediabetes rely heavily on clinical tests, such as the oral glucose tolerance test. However, these methods have limitations in implementation. Plasma glucose levels can be influenced by various factors [8], leading to controversies surrounding the screening standards for fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) [9]. Therefore, the development of non-invasive, convenient, and cost-effective screening tools is essential. Researchers are exploring biomarkers for early detection, including branched-chain amino acids, aromatic amino acids, low-carbon-number saturated fatty acids, and various carbohydrate metabolites (such as glucose, disaccharides, mannose, arabinose, fructose, and glycolipids) that have shown associations with type 2 diabetes risk [10–13]. However, the stability of these metabolites can be a concern. Recent studies have indicated that levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1༈IGFBP1༉may effectively identify high-risk individuals early on [14]. However, IGFBP1 measurement relies on enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, which can be limited by issues with antibody specificity and cross-reactivity. In conclusion, the identification of a straightforward, cost-effective, non-invasive, and highly predictive biomarker is crucial for improving early detection and intervention strategies for DM. Efforts to enhance screening methodologies will be vital in addressing this growing health crisis effectively.

The Hemoglobin Glycation Index (HGI) is defined as the discrepancy between observed HbA1c values and those predicted based on FPG concentrations [15]. Initially proposed by Hempe et al. in 2002, HGI was developed to quantify inter-individual differences in HbA1c levels [16]. As an emerging biomarker, HGI has gained increasing attention due to its correlation with various diseases, particularly its utility in predicting adverse outcomes in cardiovascular diseases [17–20]. Research on DM and HGI has primarily focused on forecasting microvascular and macrovascular complications associated with DM [21]. Elevated HGI may facilitate the occurrence and progression of diabetic complications by promoting inflammatory responses and the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) [22, 23]. However, few studies have explored the impact of HGI on glucose metabolism. Existing research has shown that individuals without DM but with high HGI levels exhibit higher fasting insulin concentrations and more severe IR when compared to those with low HGI [24]. Additionally, higher HGI is associated with advanced age, obesity, and dyslipidemia—all recognized risk factors for DM [22, 25, 26]. Nevertheless, there is a notable lack of large-scale cohort studies examining the relationship between HGI and the risk of DM and prediabetes.

Given the increasing burden of DM and the urgent need for effective preventive strategies, this study aims to investigate the potential of HGI as a biomarker for risk stratification of DM and prediabetes by analyzing a large cohort from the Chinese population in the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) database. Understanding this relationship may shed light on the pathogenesis of DM and prediabetes, facilitating timely interventions for those at high risk. Furthermore, the findings could contribute to the development of more targeted preventive strategies, ultimately mitigating the public health impact of DM and its complications.

Methods

Data source and study population

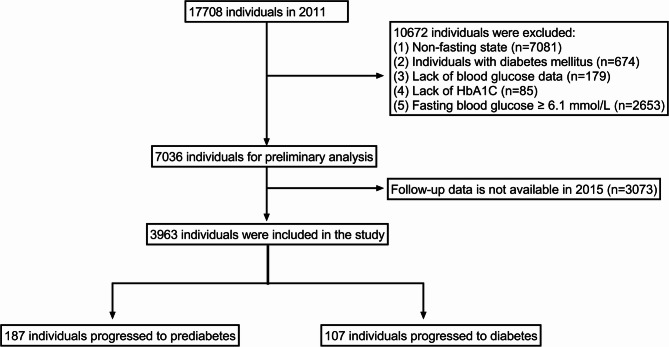

This study employs data from the CHARLS database, a nationwide cohort survey designed to monitor the health and well-being of residents aged 45 and older in China. Initiated in 2011 and followed up in 2015, CHARLS utilized a multistage stratified probability sampling technique, proportional to population size, covering 150 counties and districts across 28 provinces. The initial survey achieved a robust response rate of 80.5%, significantly minimizing the risk of selection bias and enhancing the representativeness of the cohort. This approach ensures that the CHARLS dataset accurately reflects the demographic, socioeconomic, and geographic characteristics of China’s middle-aged and elderly population [27]. Blood samples were collected, stored, and analyzed at −70 °C. HbA1c levels were measured using the affinity high-performance liquid chromatography method, while FPG was assessed via enzymatic colorimetric tests [28]. Detailed information on the study design and cohort profiles is available on the official CHARLS website. For this analysis, the baseline cohort consisted of participants who completed the first wave of the survey in 2011 and were subsequently followed up in 2015, totaling 17,708 individuals. Several exclusion criteria were applied during baseline data inclusion, resulting in the removal of 10,672 subjects: (1) non-fasting state (n = 7,081); (2) individuals with DM (n = 674); (3) lack of plasma glucose data (n = 179); (4) lack of HbA1c data (n = 85); (5) FPG ≥ 6.1 mmol/L (n = 2,653). After these exclusions, we were left with 7,036 participants. An additional 3,073 participants were excluded due to unavailability of follow-up data, yielding a final study sample of 3,963 participants. DM was defined as FPG ≥ 7.0 mmol/L, while prediabetes was defined as FPG between 6.1 and 6.9 mmol/L [29]. Figure 1 presents a detailed flowchart illustrating the inclusion and exclusion criteria used for participant selection.

Fig. 1.

The flowchart of this study

HGI assessment

Laboratory analyses of FPG and HbA1c were conducted at the Youanmen Clinical Laboratory Center of Capital Medical University. HbA1c levels were measured using the affinity high-performance liquid chromatography method, while FPG was assessed via enzymatic colorimetric tests. We developed a linear regression model based on FPG and measured HbA1c, resulting in the following prediction equation: Predicted HbA1c = 4.378 + 0.132 × FPG (mmol/L). By substituting each participant’s FPG into the equation, the individual’s predicted HbA1c value can be calculated. The HGI is calculated derived using the standard formula [15]: HGI = Measured HbA1c - predicted HbA1c.

Outcome definition

The outcome event was defined as the occurrence of DM or prediabetes during the follow-up in 2015. Participants with FPG levels above 7.0 mmol/L were classified as having DM, while those with FPG levels between 6.1 and 6.9 mmol/L were classified as having prediabetes.

Covariates

In this study, the covariates included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), current smoking status, current alcohol consumption status, residential area, level of education, and comorbidities. Education was categorized into four levels: below primary school, primary school, middle school, high school and above. Comorbidities encompassed hypertension, cancer, chronic pulmonary disease, heart disease, stroke, psychiatric disorders, arthritis, dyslipidemia, hepatic disease, kidney disease, digestive system diseases, asthma, and memory-related conditions.

Statistical analysis

All analyses in this study were conducted using R programming language (version 4.4.2). The normality of the data was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous variables were found to be non-normally distributed and were expressed as the median (interquartile range), while categorical variables were represented as n (%). The Mann-Whitney U test was used for analyzing continuous variables. Both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the predictive ability of HGI for the incidence of DM and prediabetes. A restricted cubic splines (RCS) model was employed for dose-response analysis. To ensure model stability, subgroup analyses were conducted across different populations. All tests were two-sided, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the included population

This study included 3,963 participants from the CHARLS dataset, with an average age of 57 years, of whom 44.11% were male. After four years of follow-up, 187 individuals (4.72%) developed prediabetes, and 107 individuals (2.70%) developed DM. Compared to the normoglycemic group (−0.02), those with prediabetes (0.05) and DM (0.19) had significantly higher HGI values (p < 0.01). Additionally, individuals with prediabetes and DM exhibited the following characteristics: an older average age (59 and 60 years versus 57 years), higher BMI (24.41 and 23.73 vs. 23.31), greater prevalence of dyslipidemia (14.44% and 8.41% vs. 8.29%), increased rates of hypertension (33.16% and 42.06% vs. 22.54%), and higher prevalence of stroke (2.14% and 6.54% vs. 1.85%). Furthermore, individuals with elevated plasma glucose levels were more likely to develop memory-related diseases compared to the normoglycemic group. No significant differences were observed in other characteristics. A detailed summary of participant characteristics is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the population included in this study

| Characteristics | Total (n = 3963) |

Normal (n = 3669) |

Prediabetes (n = 187) |

Diabetes mellitus (n = 107) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 57.00 (51.00, 64.00) | 57.00 (51.00,64.00) | 59.00 (54.00,66.00) | 60.00 (53.50,66.50) | < 0.01 |

| Gender, (%) | 0.29 | ||||

| Female | 2215 (55.89) | 2047 (55.79) | 113 (60.43) | 55 (51.40) | |

| Male | 1748 (44.11) | 1622 (44.21) | 74 (39.57) | 52 (48.60) | |

| Body mass index | 23.37 (21.01, 26.42) | 23.31 (20.96,26.33) | 24.41 (21.64,28.22) | 23.73 (21.70,27.42) | < 0.01 |

| Smoking, (%) | 0.69 | ||||

| No | 2809 (70.88) | 2603 (70.95) | 134 (71.66) | 72 (67.29) | |

| Yes | 1154 (29.12) | 1066 (29.05) | 53 (28.34) | 35 (32.71) | |

| Drink, (%) | 0.99 | ||||

| No | 2676 (67.52) | 2477 (67.51) | 127 (67.91) | 72 (67.29) | |

| Yes | 1287 (32.48) | 1192 (32.49) | 60 (32.09) | 35 (32.71) | |

| Residential area, (%) | 0.32 | ||||

| Urban | 1338 (33.76) | 1229 (33.50) | 66 (35.29) | 43 (40.19) | |

| Rural | 2625 (66.24) | 2440 (66.50) | 121 (64.71) | 64 (59.81) | |

| Education, (%) | 0.12 | ||||

| Below Primary School | 1883 (47.51) | 1723 (46.96) | 105 (56.15) | 55 (51.40) | |

| Primary School | 881 (22.23) | 815 (22.21) | 40 (21.39) | 26 (24.30) | |

| Middle School | 807 (20.36) | 765 (20.85) | 25 (13.37) | 17 (15.89) | |

| High school and above | 392 (9.89) | 366 (9.98) | 17 (9.09) | 9 (8.41) | |

| Co-morbidities, (%) | |||||

| Hypertension | 934 (23.57) | 827 (22.54) | 62 (33.16) | 45 (42.06) | < 0.01 |

| Cancer | 32 (0.81) | 31 (0.84) | 1 (0.53) | 0 (0.00) | 1.00 |

| Chronic lung disease | 385 (9.71) | 357 (9.73) | 17 (9.09) | 11 (10.28) | 0.94 |

| Heart disease | 449 (11.33) | 416 (11.34) | 20 (10.70) | 13 (12.15) | 0.93 |

| Stroke | 79 (1.99) | 68 (1.85) | 4 (2.14) | 7 (6.54) | 0.01 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 51 (1.29) | 44 (1.20) | 4 (2.14) | 3 (2.80) | 0.11 |

| Arthritis | 1330 (33.56) | 1221 (33.28) | 69 (36.90) | 40 (37.38) | 0.41 |

| Dyslipidemia | 340 (8.58) | 304 (8.29) | 27 (14.44) | 9 (8.41) | 0.01 |

| Hepatic disease | 136 (3.43) | 122 (3.33) | 9 (4.81) | 5 (4.67) | 0.43 |

| Kidney disease | 223 (5.63) | 208 (5.67) | 9 (4.81) | 6 (5.61) | 0.88 |

| Digestive system disease | 896 (22.61) | 820 (22.35) | 50 (26.74) | 26 (24.30) | 0.34 |

| Asthma | 172 (4.34) | 156 (4.25) | 9 (4.81) | 7 (6.54) | 0.49 |

| Memory-related disease | 39 (0.98) | 32 (0.87) | 5 (2.67) | 2 (1.87) | 0.03 |

| HGI | −0.01 (−0.25, 0.23) | −0.02 (−0.26,0.22) | 0.05 (−0.16,0.28) | 0.19 (−0.13,0.36) | < 0.01 |

Logistic regression models for predicting the occurrence of DM and prediabetes based on the HGI

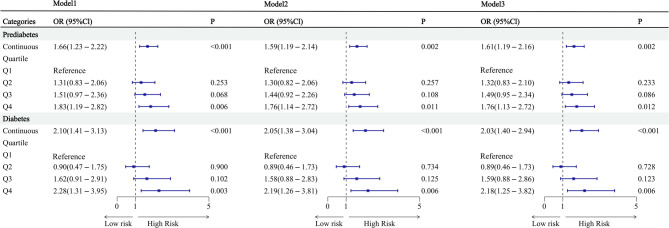

Logistic regression models were constructed separately for the DM and prediabetes populations. Model 1 represents the unadjusted model. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, and alcohol consumption. Model 3 was further adjusted for variables in Model 2, as well as for residential area, education, and comorbidities. Figure 2 demonstrates that in individuals with DM, the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the continuous HGI variable were 2.10 (1.41–3.13), 2.05 (1.38–3.04), and 2.03 (1.40–2.94), respectively, with all p-values < 0.001. In individuals with prediabetes, the OR and 95% CI for the continuous HGI variable were 1.66 (1.23–2.22), 1.59 (1.19–2.14), and 1.61 (1.19–2.16), respectively, with all p-values < 0.002. After stratifying HGI into quartiles, the predicted values for the fourth quartile (Q4) were higher than those for the first quartile (Q1) in both populations. Figure 2 presents the regression models for both groups.

Fig. 2.

Logistic regression of HGI predicting the occurrence of prediabetes and diabetes Model 1: unadjusted Model 2: adjusted for age, gender, body mass index, smoking and drinking Model 3: adjusted for Model 2 + residential area, education, and all co-morbidities OR, Odds ratio; CI, Confidence interval. HGI: Hemoglobin glycation index

RCS model

A multivariable-adjusted RCS regression method was employed to demonstrate the dose-response relationship between HGI and the prevalence of DM and prediabetes across four groups (the entire population, the normoglycemic group, the DM group, and the prediabetes group). Figure 3A shows a linear relationship between HGI and the incidence of prediabetes (p = 0.007), and Fig. 3B shows a linear relationship between HGI and the incidence of DM (p < 0.001), with an inflection point of −0.0172 for both groups.

Fig. 3.

Restricted cubic spline regression with multivariable - adjusted associations was adopted to demonstrate the dose - response relationships between HGI and prediabetes/diabetes in the prediabetes group (Fig. 3A) and the diabetes group (Fig. 3B)

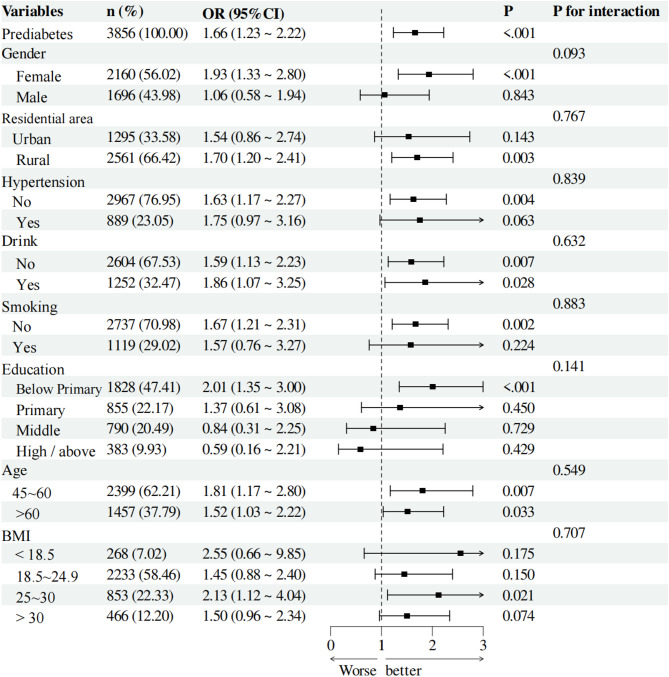

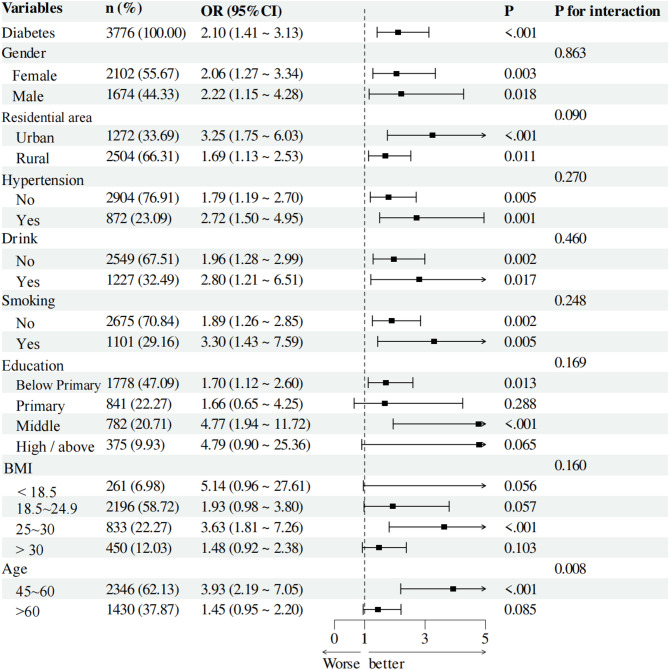

Subgroup analysis

We conducted subgroup analyses for individuals in the DM and prediabetes groups to assess the applicability of HGI across different populations. We analyzed various subgroups, considering variables such as gender, residential area, hypertension status, educational level, smoking status, alcohol consumption, age, and BMI. In the prediabetes group, all interaction p-values were greater than 0.05, indicating no significant statistical interactions among different subgroups. This result suggests that the effect of HGI did not show significant differences across various subgroups (Fig. 4). In the DM group, we observed a significant interaction between age and HGI (p = 0.008). Specifically, individuals aged 45 to 60 years had an OR of 3.93 (95% CI: 2.19–7.05, p < 0.001), indicating a greater impact of HGI in this age cohort. These findings emphasize the importance of age as a factor affecting the applicability of HGI (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Subgroup analyses were conducted among individuals with prediabetes to determine the applicability of HGI in different populations

Fig. 5.

Subgroup analyses were carried out on individuals with diabetes to determine the applicability of HGI in different populations

Discussion

In this study, we utilized large-scale cohort data from the CHARLS to examine the predictive value of the HGI for the incidence of DM and prediabetes. Our findings reveal a significant association between HGI and the risk of developing DM and prediabetes. Notably, HGI demonstrated a linear relationship with both conditions, reinforcing its role as a valid predictive indicator of DM risk and suggesting its potential for assessing risk across various glycemic states. We found that higher HGI values correlated positively with an increased risk of developing prediabetes and DM, indicating that HGI could function as a continuous risk indicator, thereby offering a more nuanced assessment than traditional categorical methods. Additionally, subgroup analyses highlighted that the correlation between HGI and DM risk was particularly pronounced among individuals aged 45 to 60 years, suggesting that age significantly influences the predictive accuracy of HGI. Therefore, adopting targeted evaluation methods for specific populations could enhance the identification of high-risk individuals effectively.

The HGI reveals the discrepancy between actual HbA1c levels and the theoretical values expected based on plasma glucose [30]. First proposed by Dr. Hempe and colleagues in 2002 [16], HGI has emerged as a valuable tool for assessing glycemic variability and has been significantly associated with an increased risk of both microvascular and macrovascular complications of DM [31–34]. Despite its importance, there is limited research on the role of HGI in predicting the onset of DM and prediabetes. Our study builds upon prior research while introducing innovative elements. For instance, Lu et al. demonstrated that individuals with higher HGI levels face a greater risk of developing DM, irrespective of plasma glucose status [35]. Our findings support this, showing that individuals with elevated plasma glucose also exhibited higher HGI levels. However, our research diverges from previous studies in several key areas. Most importantly, we are the first to examine the incidence of prediabetes as an outcome, establishing a linear relationship between HGI and the onset of prediabetes. Additionally, our data were sourced from the CHARLS database, which includes a nationally representative population from various regions in China, contrasting with the REACTION study data used by Lu et al. This difference underscores the broader applicability of our findings. Furthermore, our results indicate that age significantly influences the predictive value of HGI, particularly among individuals aged 45 to 60 years. This may be related to the following factors. First and foremost, muscle mass decreases by approximately 1% annually starting from middle age, with a more pronounced decline after the age of 50 [36]. Meanwhile, visceral fat increases year by year [37]. These changes are significantly associated with increased IR [38, 39]. Second, mitochondrial function declines with age, which may be associated with a reduction in mitochondrial DNA copy number, decreased fatty acid oxidation capacity, IR, and diminished muscle function [40, 41]. Third, aging diminishes the regenerative capacity of pancreatic β-cells [42, 43]. Two studies have demonstrated that, compared with β-cells in middle age, both younger and older groups exhibit higher expression levels of genes associated with ion channels, immune response, protein folding and degradation, endoplasmic reticulum stress response, autophagy, amino acid activation, incretin signaling, and fatty acid metabolism [44, 45]. These findings suggest that the decline in β-cell function is more pronounced in middle age. In addition, inflammatory markers (including mainly interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and tumor necrosis factor) accumulate with increasing age [46]. Particularly during middle age, hormonal changes may lead to a more pronounced accumulation of these inflammatory factors. Elevated levels of these markers are associated with age-related diseases such as cardiovascular disease, increased IR, and cancer [47]. We found no significant interaction between HGI and BMI; instead, a notable interaction was observed between HGI and age. In conclusion, our study reveals several significant distinctions from previous research, highlighting the potential of HGI as a predictive tool for both DM and prediabetes, particularly concerning age.

The HGI can predict the onset of DM and prediabetes, though the precise mechanisms involved remain unclear. HGI is primarily associated with the body’s inflammatory responses and oxidative stress through several pathways that influence the progression of DM and its prediabetic states. HGI reflects plasma glucose variability over time, which contributes to increased oxidative stress, the production of inflammatory cytokines, and endothelial dysfunction [48, 49]—common pathological factors for cardiovascular diseases and prediabetes. A high HGI level indicates an enhancement of non-enzymatic glycation reactions within cells, closely linked to the formation of AGEs [10, 22, 23]. The formation and accumulation of AGEs initiate a cascade of oxidative stress responses, resulting in elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells. These ROS can activate multiple inflammatory pathways, exacerbating cellular damage and tissue inflammation, which in turn contributes to the development of DM and prediabetes. AGEs not only directly promote the apoptosis of pancreatic β-cells but also disrupt their insulin synthesis and secretion. This exacerbates hyperglycemia, triggering chronic inflammation and further AGE production [50–52], thus forming a vicious cycle. Furthermore, compared to persistent hyperglycemia, creating a vicious cycle. Furthermore, compared to persistent hyperglycemia, fluctuations in blood glucose levels lead to significantly increased pancreatic β-cell dysfunction and apoptosis, resulting in reduced insulin secretion. In summary, HGI serves as a crucial predictor of DM and prediabetes, with its effects mediated through oxidative stress, inflammation, and cellular dysfunction [53].

When evaluating HbA1c and HGI, a variety of confounding factors can influence these measurements. First, age is a significant factor. As age increases, changes in metabolism and hormonal responses may affect insulin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis, thereby leading to alterations in HbA1c levels [54, 55]. Secondly, differences in genetic background can also influence HbA1c levels. Existing studies have shown that the heterogeneity in hemoglobin glycation rates among different racial groups may lead to differences in HbA1c values at similar levels of glucose exposure. This phenomenon may be mediated by differences in red blood cell lifespan or hemoglobin-glucose affinity among different races [56]. Moreover, the quantity and quality of hemoglobin can also impact the values of HbA1c. For instance, individuals with sickle cell disease, thalassemia, and other hemoglobinopathies may experience alterations in red blood cell lifespan and the accuracy of HbA1c measurements [57, 58]. Finally, certain diseases such as liver disease, endocrine disorders (e.g., Cushing’s syndrome), and infections can also affect glucose metabolism and HbA1c levels, potentially leading to misinterpretations of DM control [59–62]. These factors influence HGI by compromising the accuracy of HbA1c measurements. Model 3 was adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, residential area, education, and all comorbidities. We did not adjust for factors such as race, hemoglobin variants, or infections. Future studies should consider these factors in further analyses.

This study presents several innovative aspects. Firstly, by analyzing a large-scale longitudinal cohort from the CHARLS database, we systematically assessed the effectiveness of HGI as a predictor of DM and prediabetes. Unlike prior studies that focused on specific populations or employed cross-sectional designs, our research utilized a nationally representative sample, enhancing applicability and reliability. Secondly, we identified a dose-response relationship between HGI and the incidence of DM and prediabetes across various plasma glucose categories. Specifically, we observed a linear relationship between HGI and the occurrence of both DM and prediabetes, which allowed us to establish critical values for different patient groups. This finding has significant clinical implications for the early identification of high-risk populations and the development of targeted prevention strategies. Lastly, our subgroup analysis indicated that age influences the relationship between HGI and DM risk, revealing that individuals aged 45 to 60 have a higher predictive value. In summary, our study expands the understanding of HGI’s role in predicting DM and prediabetes and underscores its potential for enhancing patient care through early intervention.

Although this study is innovative, it still has some limitations. First, the measurement of HGI may be influenced by sample collection and processing conditions, which can compromise its consistency across different clinical settings. Additionally, biological differences among individuals can result in variability in HGI levels, impacting its accuracy as a predictive marker. Second, the CHARLS database sample is limited to middle-aged and elderly individuals in China. The current findings cannot yet be directly extrapolated to other age groups and racial populations, necessitating further clinical studies for validation. Furthermore, although we accounted for various covariates, not all potential confounding factors—such as genetic background, lifestyle, physical activity, and medication information (such as statins)—were included. These factors may also affect the relationship between HGI and the risks of DM and prediabetes. To address these limitations, future research should focus on multicenter and international comparative studies, as well as investigating the long-term effects of adjustment factors on the risk of DM and prediabetes.

Conclusion

HGI may serve as a useful marker to identify individuals at higher risk of DM and prediabetes, pending further validation. HGI is a cost-effective biomarker calculated from existing data (HbA1c and FPG), suitable for routine screening. Its linear relationship with DM incidence allows for more nuanced risk assessment compared to traditional methods. Integrating HGI into risk prediction models enhances accuracy, especially in the 45 to 60 age group. If the HGI is excessively high, it is recommended that timely interventions, such as health education and lifestyle modifications, be initiated in clinical practice. Future research should validate HGI’s predictive value across diverse populations and explore its integration with other biomarkers to optimize risk stratification. Incorporating HGI into clinical practice could improve early detection and intervention of DM, reducing complications.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- DM

Diabetes Mellitus

- HGI

Hemoglobin Glycation Index

- HbA1c

Glycated Hemoglobin

- CHARLS

China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

- FPG

Fasting Plasma Glucose

- CI

Confidence Intervals

- OR

Odds Ratios

- AGEs

Advanced Glycation End Products

- RCS

Restricted Cubic Splines

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species

Authors’ contributions

The concept of this study was designed by J.B. and D.M., J.B., D.M. and M.L.conducted the data analysis and drafted the manuscript; H.Y.,Q.H. and T.L. revised the manuscript and was responsible for supervising the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No.ZR2016HM49), Hori-zontal research project of Shandong University (No.3450012001901 and 23460012711702), and Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Development Plan Project of Shandong Province (No.2019 − 0891).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The CHARLS study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University. All participants provided written informed consent before participating in the CHARLS study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jing-Xian Bai and De-Gang Mo contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Tao Liu, Email: 13563504653@163.com.

Qian-Feng Han, Email: hqfg01@163.com.

Heng-Chen Yao, Email: yaohc66@126.com.

References

- 1.Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: results from the international diabetes federation diabetes atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;157:107843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, Srinivasan M, Lin J, Geiss LS, Albright AL, et al. Trends in cause-specific mortality among adults with and without diagnosed diabetes in the USA: an epidemiological analysis of linked national survey and vital statistics data. Lancet. 2018;391(10138):2430–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bommer C, Heesemann E, Sagalova V, Manne-Goehler J, Atun R, Bärnighausen T, et al. The global economic burden of diabetes in adults aged 20–79 years: a cost-of-illness study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(6):423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edgerton DS, Kraft G, Smith M, Farmer B, Williams PE, Coate KC, et al. Insulin’s direct hepatic effect explains the inhibition of glucose production caused by insulin secretion. JCI Insight. 2017;2(6):e91863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan RMM, Chua ZJY, Tan JC, Yang Y, Liao Z, Zhao Y. From pre-diabetes to diabetes: Diagnosis, treatments and translational research. Medicina (B Aires). 2019;55(9):546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Umpierrez G, Korytkowski M. Diabetic emergencies - ketoacidosis, hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar state and hypoglycaemia. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(4):222–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pantalone KM, Hobbs TM, Wells BJ, Kong SX, Kattan MW, Bouchard J, et al. Clinical characteristics, complications, comorbidities and treatment patterns among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a large integrated health system. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2015;3(1):e000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;183:109119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gong Q, Zhang P, Wang J, Ma J, An Y, Chen Y, et al. Morbidity and mortality after lifestyle intervention for people with impaired glucose tolerance: 30-year results of the Da Qing diabetes prevention outcome study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(6):452–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guasch-Ferré M, Hruby A, Toledo E, Clish CB, Martínez-González MA, Salas-Salvadó J, et al. Metabolomics in prediabetes and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(5):833–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu F, Tavintharan S, Sum CF, Woon K, Lim SC, Ong CN. Metabolic signature shift in type 2 diabetes mellitus revealed by mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(6):E1060-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menni C, Fauman E, Erte I, Perry JR, Kastenmüller G, Shin SY, et al. Biomarkers for type 2 diabetes and impaired fasting glucose using a nontargeted metabolomics approach. Diabetes. 2013;62(12):4270–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suhre K, Meisinger C, Döring A, Altmaier E, Belcredi P, Gieger C, et al. Metabolic footprint of diabetes: a multiplatform metabolomics study in an epidemiological setting. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):e13953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer NMT, Kabisch S, Dambeck U, Honsek C, Kemper M, Gerbracht C, et al. Low IGF1 and high IGFBP1 predict diabetes onset in prediabetic patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2022;187(4):555–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hempe JM, Liu S, Myers L, McCarter RJ, Buse JB, Fonseca V. The hemoglobin glycation index identifies subpopulations with harms or benefits from intensive treatment in the ACCORD trial. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(6):1067–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hempe JM, Gomez R, McCarter RJ Jr., Chalew SA. High and low hemoglobin glycation phenotypes in type 1 diabetes: a challenge for interpretation of glycemic control. J Diabetes Complications. 2002;16(5):313–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng W, Huang R, Pu Y, Li T, Bao X, Chen J, et al. Association between the haemoglobin glycation index (HGI) and clinical outcomes in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Ann Med. 2024;56(1):2330615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei X, Chen X, Zhang Z, Wei J, Hu B, Long N, et al. Risk analysis of the association between different hemoglobin glycation index and poor prognosis in critical patients with coronary heart disease-a study based on the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1):113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng PC, Hsu SR, Cheng YC, Liu YH. Relationship between hemoglobin glycation index and extent of coronary heart disease in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang J, Shangguan Q, Xie G, Yang M, Sheng G. Sex-specific associations between haemoglobin glycation index and the risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in individuals with pre-diabetes and diabetes: a large prospective cohort study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26(6):2275–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xin S, Zhao X, Ding J, Zhang X. Association between hemoglobin glycation index and diabetic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus in China: a cross- sectional inpatient study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1108061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S, Hempe JM, McCarter RJ, Li S, Fonseca VA. Association between inflammation and biological variation in hemoglobin A1c in U.S. nondiabetic adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(6):2364–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Felipe DL, Hempe JM, Liu S, Matter N, Maynard J, Linares C, et al. Skin intrinsic fluorescence is associated with hemoglobin A(1c)and hemoglobin glycation index but not mean blood glucose in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(8):1816–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marini MA, Fiorentino TV, Succurro E, Pedace E, Andreozzi F, Sciacqua A, et al. Association between hemoglobin glycation index with insulin resistance and carotid atherosclerosis in non-diabetic individuals. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(4):e0175547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin L, Wang A, He Y, Wang W, Gao Z, Tang X, Yan L, Wan Q, Luo Z, Qin G, et al. Effects of the hemoglobin glycation index on hyperglycemia diagnosis: results from the REACTION study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;180:109039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiorentino TV, Marini MA, Succurro E, Andreozzi F, Sciacqua A, Hribal ML, et al. Association between hemoglobin glycation index and hepatic steatosis in non-diabetic individuals. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;134:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, Strauss J, Yang G. Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):61–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen X, Crimmins E, Hu PP, Kim JK, Meng Q, Strauss J, Wang Y, Zeng J, Zhang Y, Zhao Y. Venous Blood-Based biomarkers in the China health and retirement longitudinal study: Rationale, Design, and results from the 2015 wave. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188(11):1871–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, Delgado V, Federici M, Filippatos G, Grobbee DE, Hansen TB, et al. 2019 ESC guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(2):255–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soros AA, Chalew SA, McCarter RJ, Shepard R, Hempe JM. Hemoglobin glycation index: a robust measure of hemoglobin A1c bias in pediatric type 1 diabetes patients. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010;11(7):455–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCarter RJ, Hempe JM, Gomez R, Chalew SA. Biological variation in HbA1c predicts risk of retinopathy and nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Steen SC, Woodward M, Chalmers J, Li Q, Marre M, Cooper ME, et al. Haemoglobin glycation index and risk for diabetes-related complications in the action in diabetes and vascular disease: preterax and diamicron modified release controlled evaluation (ADVANCE) trial. Diabetologia. 2018;61(4):780–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim MK, Jeong JS, Yun JS, Kwon HS, Baek KH, Song KH, et al. Hemoglobin glycation index predicts cardiovascular disease in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 10-year longitudinal cohort study. J Diabetes Complications. 2018;32(10):906–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu JD, Liang DL, Xie Y, Chen MY, Chen HH, Sun D, et al. Association between hemoglobin glycation index and risk of cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality in type 2 diabetic patients: a meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:690689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin L, Wang A, Jia X, Wang H, He Y, Mu Y, et al. High hemoglobin glycation index is associated with increased risk of diabetes: a population-based cohort study in China. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1081520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkinson DJ, Piasecki M, Atherton PJ. The age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and function: measurement and physiology of muscle fibre atrophy and muscle fibre loss in humans. Ageing Res Rev. 2018;47:123–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huffman DM, Barzilai N. Role of visceral adipose tissue in aging. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790(10):1117–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim HJ. Insulin sensitivity and muscle loss in the absence of diabetes mellitus: findings from a longitudinal Community-Based cohort study. J Clin Med. 2025;14(4):1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Zhao Y, Yue R. Aging adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. Biogerontology. 2024;25(1):53–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petersen KF, Befroy D, Dufour S, Dziura J, Ariyan C, Rothman DL, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the elderly: possible role in insulin resistance. Science. 2003;300(5622):1140–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hebert SL, Marquet-de Rougé P, Lanza IR, McCrady-Spitzer SK, Levine JA, Middha S, Carter RE, Klaus KA, Therneau TM, Highsmith EW, et al. Mitochondrial aging and physical decline: insights from three generations of women. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(11):1409–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scaglia L, Cahill CJ, Finegood DT, Bonner-Weir S. Apoptosis participates in the remodeling of the endocrine pancreas in the neonatal rat. Endocrinology. 1997;138(4):1736–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gregg BE, Moore PC, Demozay D, Hall BA, Li M, Husain A, et al. Formation of a human β-cell population within pancreatic islets is set early in life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(9):3197–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tong X, Dai C, Walker JT, Nair GG, Kennedy A, Carr RM, et al. Lipid droplet accumulation in human pancreatic islets is dependent on both donor age and health. Diabetes. 2020;69(3):342–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shrestha S, Erikson G, Lyon J, Spigelman AF, Bautista A, Manning Fox JE, Dos Santos C, Shokhirev M, Cartailler JP, Hetzer MW, et al. Aging compromises human islet beta cell function and identity by decreasing transcription factor activity and inducing ER stress. Sci Adv. 2022;8(40):eabo3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michaud M, Balardy L, Moulis G, Gaudin C, Peyrot C, Vellas B, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines, aging, and age-related diseases. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(12):877–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh T, Newman AB. Inflammatory markers in population studies of aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(3):319–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rizzo MR, Barbieri M, Marfella R, Paolisso G. Reduction of oxidative stress and inflammation by blunting daily acute glucose fluctuations in patients with type 2 diabetes: role of dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibition. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(10):2076–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Monnier L, Mas E, Ginet C, Michel F, Villon L, Cristol JP, et al. Activation of oxidative stress by acute glucose fluctuations compared with sustained chronic hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2006;295(14):1681–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pezhman L, Tahrani A, Chimen M. Dysregulation of leukocyte trafficking in type 2 diabetes: mechanisms and potential therapeutic avenues. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:624184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Makita Z, Vlassara H, Rayfield E, Cartwright K, Friedman E, Rodby R, Cerami A, Bucala R. Hemoglobin-AGE: a Circulating marker of advanced glycosylation. Science. 1992;258(5082):651–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Friedman EA. Advanced glycosylated end products and hyperglycemia in the pathogenesis of diabetic complications. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(Suppl 2):B65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim MK, Jung HS, Yoon CS, Ko JH, Jun HJ, Kim TK, et al. The effect of glucose fluctuation on apoptosis and function of INS-1 pancreatic beta cells. Korean Diabetes J. 2010;34(1):47–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pani LN, Korenda L, Meigs JB, Driver C, Chamany S, Fox CS, et al. Effect of aging on A1C levels in individuals without diabetes: evidence from the Framingham offspring study and the National health and nutrition examination survey 2001–2004. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(10):1991–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karakelides H, Irving BA, Short KR, O’Brien P, Nair KS. Age, obesity, and sex effects on insulin sensitivity and skeletal muscle mitochondrial function. Diabetes. 2010;59(1):89–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pemberton JS, Fang Z, Chalew SA, Uday S. Ethnic disparities in HbA1c and hypoglycemia among youth with type 1 diabetes: beyond access to technology, social deprivation and mean blood glucose. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2025;13(1):e004369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.McLean A, Wright F, deJong N, Skinner S, Loughlin CE, Levenson A, Carden MA. Hemoglobin A(1c) and Fructosamine correlate in a patient with sickle cell disease and diabetes on chronic transfusion therapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(9):e28499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu A, Ji L, Chen W, Xia Y, Zhou Y. Effects of α-thalassemia on HbA(1c) measurement. J Clin Lab Anal. 2016;30(6):1078–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sehrawat T, Jindal A, Kohli P, Thour A, Kaur J, Sachdev A, et al. Utility and limitations of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) in patients with liver cirrhosis as compared with oral glucose tolerance test for diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9(1):243–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nadelson J, Satapathy SK, Nair S. Glycated hemoglobin levels in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Int J Endocrinol. 2016;2016:8390210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sharma A, Vella A. Glucose metabolism in Cushing’s syndrome. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2020;27(3):140–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holt RIG, Cockram CS, Ma RCW, Luk AOY. Diabetes and infection: review of the epidemiology, mechanisms and principles of treatment. Diabetologia. 2024;67(7):1168–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.