Abstract

Background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a growing global health burden often accompanied by multiple comorbidities that complicate management and worsen clinical outcomes. Understanding the epidemiological profile of these comorbid conditions is essential for developing integrated and effective diabetes care strategies, particularly in low- and middle-income countries such as Nepal. This study aimed to determine the prevalence and factors associated with common comorbidities among patients with T2DM in Nepal.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional household study. The primary data was collected from T2DM patients in Madhesh Province, Nepal. Multistage sampling was used to select 492 patients with T2DM from the population. Data was collected through structured interviews, and comorbidities were documented based on patients self-reports and subsequently verified with physician prescriptions. Data on demographic characteristics, clinical profiles, and behaviour and lifestyle factors were collected as potential predictors of comorbidities. Descriptive statistics and logistic regression were employed to determine the prevalence and associated factors of comorbidities.

Results

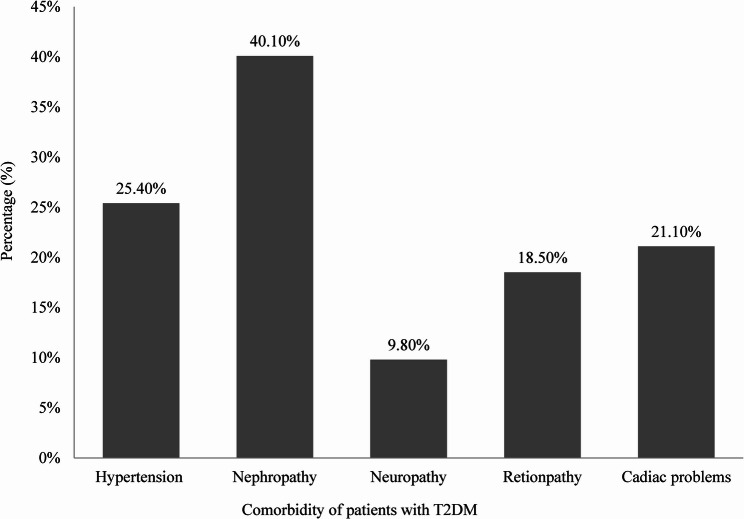

Among 492 patients with T2DM, 92.1% had at least one comorbidity. The most common comorbidity was nephropathy (40.1%), followed by hypertension (25.4%), cardiac problems (21.1%), retinopathy (18.5%), and neuropathy (9.8%). Logistic regression model demonstrated that males had higher odds of hypertension (AOR = 1.734; 95% CI: 1.077–2.791), while poor diet adherence increased the risk of hypertension (AOR = 2.04; 95% CI: 1.195–3.481). Cardiac comorbidities were associated with lower education (primary: AOR = 3.743; 95% CI: 1.696–8.258; secondary: 2.986; 95% CI: 1.455–6.129) and were less common among individuals engaged in business professions (AOR = 0.351; 95% CI: 0.139–0.887). Nephropathy was strongly associated with uncontrolled glycemia (AOR = 2.220; 95% CI: 1.378–3.577) and with comparatively younger age (35–50 years) (AOR = 14.292; 95% CI: 6.36–32.19). Retinopathy risk decreased with dietary compliance (AOR = 0.525; 95% CI: 0.297–0.828), and food avoidance (AOR = 0.607; 95% CI: 0.385– 0.957).

Conclusion

This study highlights a substantial burden of both microvascular and macrovascular comorbidities among patients with T2DM, with nephropathy being the most prevalent. Prioritize integrated care for diabetes and its related comorbidities with targeted support for age-specific patients, those with poor glycemic control, lower educational levels, longer disease duration, and poor dietary adherence.

Keywords: Comorbidities, Glycemic control, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Integrated diabetes management, Epidemiology

Introduction

Diabetes, a well-known epidemic with significant socioeconomic and health-related effects on both individuals and populations, has become a major global health concern. This epidemic is being fueled by shifting demographics (such as population aging), socioeconomic, migratory, dietary, and lifestyle trends, and a corresponding rise in children and adults who are overweight or obese [1–3]. A high blood glucose level is a hallmark of diabetes, a chronic metabolic disease that can severely damage key organs, including the cardiovascular system, vision, kidneys, and nervous system. According to the International Diabetes Federation, 10.5% of people worldwide between the ages of 20 and 79 had diabetes in 2021 (537 million). By 2030, this prevalence is expected to rise 11.3% (643 million), and by 2045, it will reach 12.2% (783 million). Among an estimated 536.6 million individuals living with diabetes worldwide, the prevalence was highest in high-income countries at 11.1%, followed by 10.8% in middle-income countries, and 10.8% in low-income countries [4]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with a multitude of risk factors that contribute to its increasing global prevalence. These risk factors include advancing age, obesity, particularly central adiposity, excessive caloric intake, and dietary patterns rich in animal fat. Furthermore, family history of diabetes, previous gestational diabetes, and polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), regular intake of sugary drinks, physical inactivity, and a history of severe mental illness have all been implicated. The coexistence of comorbid conditions such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and other cardiometabolic disorders further exacerbates the risk. In recent years, insufficient sleep duration, a hallmark of contemporary lifestyles, has emerged as an additional factor playing a key role in the onset of type 2 diabetes. Emerging evidence from pioneering studies suggests that sleep deprivation may impair insulin sensitivity and glucose regulation, being the pathophysiology of the disease [6]. Short sleep duration has been linked to diabetes and obesity, according to recent cross-sectional research [7, 8]. Every newly diagnosed case will already have comorbidities connected to diabetes, such as kidney, nerve, eye, and/or vascular disorders [9–11].

One of the most critical aspects of managing T2DM lies in understanding and addressing its comorbidity conditions that co-exist with diabetes and exacerbate its health outcomes [12]. Common comorbidities associated with T2DM include hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetic nephropathy, and depression [10, 13]. These comorbid conditions not only increase the complexity of disease management but also significantly heighten the risk of comorbidities and mortality [14].

The presence of comorbidities affects the progression of T2DM and complicates its therapeutic management. For example, hypertension and dyslipidemia synergistically contribute to the progression of macrovascular comorbidities like myocardial infarction and stroke. Similarly, diabetic nephropathy, often present as comorbidity, is a primary contributor to end-stage renal disease [15]. While previous studies have predominantly focused on either microvascular or macrovascular comorbidities in isolation, our study distinguishes itself by comprehensively examining both types of vascular comorbidities [15, 16]. Despite the rising prevalence of T2DM, region-specific data on the burden of comorbidities among diabetic patients especially in low and middle-income countries remain notably scarce. In Nepal, the estimated national prevalence of diabetes among adults aged 20–79 years was 8.5% in 2021, representing over 1.2 million people living with diabetes [17]. Despite this growing burden, there is a notable lack of region-specific data, especially in provinces such as Madhesh, which have unique demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and a high burden of noncommunicable diseases.

This study, conducted in Madesh province in Nepal, aims to estimate the prevalence of common comorbidities and to identify the socio-demographic and behavioral determinants of the comorbidities among patients with T2DM.

Methods

Setting and population

Madhesh province of Nepal was the study area of the present study, covering about 6.5% of the total area of the country. As per the 2021 Nepal census, the total population of the province was 6,126,288. It is the most densely populated province in Nepal and the smallest province by area (9,661 km2). The province includes eight districts, from Parsa in the west to Saptari in the east. It is a center for religious and cultural tourism [17]. All individuals with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) living in the study area were the population of the study.

Inclusion criteria

All individuals clinically diagnosed with T2DM by a registered physician, based on fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥ 126 mg/dL (≥ 7.0 mmol/L) or 2-hour plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL (≥ 11.1 mmol/L) after a 75 g oral glucose load [18], were eligible. Participants were required to be permanent residents (living continuously for at least 6 months) of the selected rural or urban municipalities in Madhesh Province and willing and able to provide informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Individuals with T2DM who were bedridden, critically ill, or mentally unable to respond to the questionnaire were excluded. Temporary residents or seasonal migrants residing in the area for less than 6 months, as well as individuals who had relocated to or were living in other provinces of Nepal during data collection, were also excluded.

Sample size determination

The sample size for this study was calculated using the following formula: n = Z2pq/d2 = n = (1.96 × 1.96 × 0.259 × 0.741)/(0.05)2 = 295. All necessary information was gathered from a previous study [19]. However, to ensure a robust dataset and account for a 5% absentee rate, the study included a total of 492 participants.

Sampling technique

We employed a mixed method sampling technique, combining multistage random sampling (probability) and snowball sampling (non-probability) to ensure comprehensive representation across Madhesh Province, Nepal. In the first stage, two districts were randomly selected from the eight districts in the province. In the second stage, two rural municipalities (gaunpalikas) and one urban municipality (nagarpalikas) were randomly selected from selected each district. In the third stage, snowball sampling was employed to identify individuals diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) within these municipalities. Initially, we identified one patient with T2DM through the assistance of a Female Community Health Volunteer (FCHV), which initiated the snowball sampling process. In this method, we initially selected 100 patients from each of the four selected rural municipalities and 64 patients from each of the two chosen urban municipalities. The first author contacted the patients and explained the purpose of the study. Unfortunately, some patients declined to participate: 6, 10, 2, and 6 patients from selected rural municipalities 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, and 4 and 10 patients from urban municipalities 1 and 2, respectively, did not agree to provide their information. Finally, 376 patients from the rural municipalities and 116 patients from the urban municipalities agreed to participate. Thus, a total of 492 patients were included in the study.

Data collection procedure

Between June 1, 2023, and March 30, 2024, the first author conducted in-person interviews to gather data. The information on sociodemographic characteristics, DM history, current medications, expenditure on treatment, self-reported symptoms, and comorbid conditions, impact of diabetes, comorbidities, and clinical parameters was gathered using a structured questionnaire. Before collecting information, we contacted our selected individuals and arranged a meeting with them. We explained the study’s objective and obtained written consent from the participants. The first author of the study conducted and collected information from each selected patient with T2DM.

Outcome variable

The comorbidities of T2DM were the outcome variables of the study. Diabetes-related comorbidities, including hypertension, nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy, and cardiac problems, were initially identified through participant self-reports. To enhance validity, these self-reports were cross-verified using available physician prescriptions and clinical records, such as laboratory reports or diagnostic test results. The presence of comorbidities was coded as 1, and the absence of comorbidities was coded as 0.

Independent variable

Various socio-economic, demographic, behavioral characteristics and anthropometric measurements were taken as independent variables in our study. We followed a previous study for selecting the variables [20]. We have considered gender (male = 1, female = 2), glycemic control (yes = 1, no = 0), perform exercise at least 30 min 5 days per week (yes = 1, no = 0), education (primary = 1, secondary = 2, college/university = 3), food restriction in daily routine (yes = 1, no = 0), occupation (1 = job, 2 = business, 3 = farming, 4 = housewife, 5 = retired), on dietary recommendation by dietitian (yes = 1, no = 0), age (18–30 year = 1, 35–50 year = 2, 51–60 year = 3 and above 60 year = 4), BMI category (normal = 1, overweight = 2, obesity = 3) and diabetes duration (early stage (1 month-3 years) = 1, mid stage (3 to 6 years) = 2, late stage (more than 6 years) = 3). All independent variables with their groups are mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of characteristics and their association with comorbidities of patients with T2DM

| Variable | Category | Hypertension | Nephropathy | Neuropathy | Retinopathy | Cardiac | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes(%) | No(%) | Yes(%) | No(%) | Yes(%) | No(%) | Yes(%) | No(%) | Yes(%) | No(%) | |||||

| Gender | Male | 80(31.3) | 176(68.8) | 101(39.5) | 155(60.5) | 20(78) | 236(92.2) | 33(12.9) | 223(87.1) | 71(27.7) | 185(72.3) | |||

| Female | 45(19.1) | 191(80.9) | 98(41.5) | 138(58.5) | 28(11.9) | 208(88.1) | 58(24.6) | 178(75.4) | 36(15.3) | 200(84.7) | ||||

| χ2 = 9.616(0.002) | χ2 = 0.219(0.640) | χ2 = 2.290(0.130) | χ2 = 11.123(0.001 | χ2 = 11.239(0.001) | ||||||||||

| Glycemic control | Control | 48(16.4) | 244(83.6) | 142(48.6) | 150(51.4) | 19(6.5) | 273(93.5) | 37(12.7) | 255(87.3) | 64(21.9) | 228(78.1) | |||

| Uncontrolled | 77(38.5%) | 123(56.5) | 57(28.5) | 143(71.5) | 29(14.5) | 171(85.5) | 54(27) | 146(73) | 43(21.5) | 157(78.5) | ||||

| χ2 = 29.846(0.001) | χ2 = 19.969(0.001) | χ2 = 8.614(0.003) | χ2 = 16.166(0.001) | χ2 = 0.012(0.912) | ||||||||||

| Perform at least 30 min of exercise 5 days per week | Yes | 95(26.6) | 262(73.4) | 154(43.1) | 203(56.9) | 29(8.1) | 328(91.9) | 62(17.4) | 295(82.6) | 83(23.2) | 274(76.8) | |||

| No | 30(22.2) | 105(77.8) | 45(33.3) | 90(66.9) | 19(14.1) | 116(85.9) | 29(21.5) | 106(78.5) | 24(17.8) | 111(82.2) | ||||

| χ2 = 0.995(0.318) | χ2 = 3.909 (0.048) | χ2 = 3.940(0.047) | χ2 = 1.100(0.294) | χ2 = 1.723(0.19) | ||||||||||

| Education | Primary | 64(27.8) | 166(68.1) | 98(42.6) | 132(57.4) | 13(14.3) | 78(85.7) | 16(17.6) | 75(82.4) | 12(13.2) | 79(86.8) | |||

| Secondary | 36(21.1) | 135(78.9) | 63(36.8) | 108(63.2) | 14(8.2) | 157(91.8) | 24(14) | 147(86) | 51(29.8) | 120(70.2) | ||||

| College/university | 25(27.5) | 66(72.5) | 38(41.8) | 53(58.2) | 21(9.1) | 209(90.8) | 91(22.2) | 79(177.8) | 44(19.1) | 186(80.9) | ||||

| χ2 = 2.626(0.26) | χ2 = 1.434(0.488) | χ2 = 2.701(0.259) | χ2 = 4.372(0.112) | 11.400(0.003) | ||||||||||

| Restricted food in daily routine | Yes | 59(34.1) | 114(65.9) | 54(31.2) | 119(68.8) | 26(8.2) | 293(91.8) | 57(17.9) | 262(82.1) | 62(19.4) | 257(80.6) | |||

| No | 66(20.7) | 253(79.3) | 145(45.5) | 174(54.5) | 22(12.7) | 151(87.3) | 34(19.7) | 139(80.3) | 45(26) | 128(74) | ||||

| χ2 = 10.650(0.001) | χ2 = 9.444 (0.002) | χ2 = 2.656(0.103) | χ2 = 0.237(0.626) | χ2 = 2.850(0.091) | ||||||||||

| Occupation | Jobs | 23(22.8) | 78(77.2) | 53(52.5) | 48(47.5) | 8(7.9) | 93(92.1) | 11(10.9) | 90(89.1) | 20(19.8) | 81(80.2) | |||

| Business | 26(26) | 74(74) | 44(44) | 56(56) | 9(9) | 91(91) | 33(33) | 77(77) | 13(13) | 87(87) | ||||

| Farming | 19(23.2) | 63(76.8) | 33(40.2) | 49(59.8) | 7(8.5) | 75(91.5) | 5(6.1) | 77(93.9) | 31(37.8) | 51(62.2) | ||||

| Housewife | 38(23.8) | 122(76.2) | 54(33.8) | 106(66.3) | 22(13.8) | 138(86.3) | 44(27.5) | 116(72.5) | 27(16.9) | 133(83.1) | ||||

| Retired | 19(38.8) | 30(61.2) | 15(30.6) | 34(69.4) | 2(4.1) | 47(95.9) | 8(16.3) | 41(83.7) | 16(32.7) | 33(67.3) | ||||

| χ2 = 8.630(0.071) | χ2 = 11.539(0.029) | χ2 = 5.281 (0.260) | χ2 = 22.340(0.001) | χ2 = 22.801(0.001) | ||||||||||

| On dietary recommendation by the dietitian | Yes | 101(27.8) | 262(72.2) | 158(43.5) | 205(56.5) | 37(10.2) | 326(89.8) | 54(14.9) | 309(85.1) | 86(23.7) | 277(76.3) | |||

| No | 24(18.6) | 105(81.4) | 41(31.81) | 88(68.2) | 11(8.5) | 118(91.5) | 37(28.7) | 92(71.3) | 21(16.3) | 108(83.7) | ||||

| χ2 = 4.268 (0.039) | χ2 = 5.449(0.020) | χ2 = 0.300(0.584) | χ2 = 12.034 (0.001) | χ2 = 3.073(0.080) | ||||||||||

| Age category | 18–34 years | 32(37.6) | 53(62.4) | 25(29.4) | 60(70.6) | 15(17.6) | 70(82.4) | 39(45.9) | 46(54.1) | 6(7.1) | 79(92.9) | |||

| 35-50years | 34(22.4) | 118(77.6) | 100(65.8) | 52(34.2) | 13(8.6) | 139(91.4) | 12(7.9) | 140(92.1) | 19(13.5) | 133(87.5) | ||||

| 51-60years | 38(26.4) | 106(73.6) | 64(44.4) | 80(55.6) | 10(6.9) | 134(93.1) | 13(9) | 131(91.0) | 42(29.2) | 102(70.2) | ||||

| > 60 | 43(38.7) | 68(61.3) | 10(9) | 101(91) | 10(9.0) | 101(91.0) | 27(24.3) | 52(76.5) | 40(36) | 71(64) | ||||

| χ2 = 11.537 (0.009) | χ2 = 91.325(0.001) | χ2 = 7.625(0.054) | χ2 = 64.686(0.001) | χ2 = 36.388(0.001) | ||||||||||

| BMI category | Normal | 41(18.3) | 183(81.7) | 92(41.1) | 132(58.9) | 32(14.3) | 192(85.7) | 36(16.1) | 188(83.9) | 41(18.3) | 188(83.9) | |||

| Overweight | 61(32.3) | 128(67.7) | 82(43.4) | 107(56.4) | 11(5.8) | 178(94.2) | 34(18) | 155(182) | 45(23.8) | 155(82) | ||||

| Obesity | 23(29.1) | 56(70.9) | 25(68.4) | 54(68.4) | 5(6.3) | 74(93.7) | 21(26.6) | 58(73.4) | 21(26.6) | 58(73.4) | ||||

| χ2 = 11.241(0.004) | χ2 = 3.255(0.196) | χ2 = 9.600(0.008) | χ2 = 4.332(0.115) | χ2 = 3.118(0.210) | ||||||||||

| Diabetes duration | Early stage (1 month − 3 years) | 38(24.7) | 116(75.3) | 74(48.1) | 80(51.9) | 20(13) | 134(87) | 42(27.3) | 112(72) | 15(9.7) | 139(90.3) | |||

| Mid stage (3 to 6 years) | 47(21.5) | 172(78.5) | 100(45.7) | 119(54.3) | 10(4.6) | 209(95.4) | 29(13.2) | 190(86.8) | 55(25.1) | 164(74.9) | ||||

| Late stage (more than 6 years) | 40(33.6) | 79(66.4) | 25(21) | 94(79) | 18(15.1) | 101(84.9) | 20(16.8) | 99(83.2) | 37(31.1) | 82(68.9) | ||||

| χ2 = 6.071(p = 0.048) | χ2 = 24.838(p = 0.001) | χ2 = 12.423(0.002) | χ2 = 12.105(0.002) | χ2 = 20.611(0.002) | ||||||||||

Questionnaire development and validation

A structured questionnaire was prepared in English. It was reviewed by five health science experts to ensure content validity, and their feedback was incorporated. The finalized version was translated into Nepali for participant comprehension. Although Maithili is widely spoken in Madhesh Province, the selected study districts—Parsa and Bara—are areas where Nepali is more commonly used, especially in formal settings such as government offices, health services, and education. As Nepali is also Nepal’s official language, the data collection tool was developed in Nepali to ensure consistency, clarity, and standardization across all study sites [21]. The translated version was carefully reviewed to ensure accuracy and cultural relevance, and a bilingual expert verified its meaning. A pilot survey was conducted to check the consistency/reliability of the questionnaire by using Cronbach’s alph (α), with an expected reliability coefficient was 0.85.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were entered in SPSS (IBM, version 26). We have checked missing data for each variable, whether outcome or independent. A few missing data points were detected and subsequently excluded from the analysis. The prevalence of comorbid conditions among individuals with T2DM was estimated. Frequencies and percentages of categorical variables were calculated using descriptive statistics. The comorbidities were separately analyzed. The chi-square test was used to identify significant factors associated with comorbidities, which were later treated as independent variables in the binary logistic regression model. The multiple binary logistic regression models were applied to assess the impact of selected socio-economic, demographic, and other factors on comorbidities. The multicollinearity problems between the independent variables in the logistic regression model were checked by the variance inflation factor (VIF). In the analysis, all VIF values were less than 5, proving no evidence of multicollinearity problems among the variables. The accuracy and goodness of fit of the model were identified by Hosmer-Lemeshow test. The results from the logistic regression models were presented as adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% Confidence interval of AOR. All statistical tests were conducted with a two-sided approach, with a level of significance considered at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (IBM, Version 26).

Ethical considerations

The Ethical Review Board (ERB) of the Nepal Health Research Council meticulously assessed the ethical considerations, scrutinized the research proposal, and granted approval for the ultimate iteration of the protocol (reference number 2925). Subsequently, we meticulously crafted a consent form in both Nepali and the local dialect. Throughout the implementation phase, our data enumerators diligently explained the contents of the form, elucidating the study’s objectives, and the data collection procedure, outlining the potential risks and benefits, and emphasized the confidentiality measures in place to protect personal information. Prior to enrollment in the study, all participants either affixed their signature or provided a thumb impression (in cases of inability to write) on a separate consent form, thus affirming their voluntary participation.

Results

Among the 492 diabetic patients, nephropathy was the most common comorbidity (40.1%), followed by hypertension (25.4%), cardiac problems (21.1%), retinopathy (18.5%), and neuropathy as the least common (9.8%) (Fig. 1). Among diabetic patients, 68.3% experienced only one comorbidity and 23.8% had two comorbidities. The most common combinations of dual comorbidities were hypertension with cardiac problems (8.1%), followed by retinopathy (6.7%), nephropathy (5.5%), and neuropathy (3.5%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of common Comorbidities among patents with T2DM

Fig. 2.

Single and dual Comorbidities among patients with T2DM

Associated factors of comorbidities

Among diabetic patients, hypertension was more prevalent in males (31.3%) than females (19.1%), higher in those with uncontrolled glycemic levels (38.5%) versus controlled (16.4%), and more common among those who restricted certain foods (34.1%) compared to those who did not (20.7%). It was also higher in patients adhering to dietary recommendations (27.8%) than non-adherent (18.6%), in overweight (32.3%) and obese patients (29.1%) compared to normal BMI (18.3%), and increased with age, peaking at 26.4% in the 51–60 age groups. Physical activity showed a slightly higher prevalence among those exercising regularly (26.6%) compared to inactivity (22.2%). Occupation and education showed varied rates, with retired individuals showing the highest prevalence (38.8%). Diabetic nephropathy affected 39.5% of males and 41.5% of females, was more common in patients with controlled glycemic levels (48.6%) than uncontrolled (28.5%), and among those adhering to dietary advice (43.5%) compared to non-adherent (31.8%). It was more frequent in patients who exercised regularly (43.1%) than inactive (33.3%), higher in those without food restrictions (45.5%) than those with restrictions (31.2%), and varied by occupation (highest in job workers at 52.5%). Nephropathy was most prevalent in the 35–50 age group (65.8%) and increased with BMI, highest in obese patients (68.4%). It decreased with longer diabetes duration, from 48.1% in early-stage to 21.0% in late-stage. Diabetic neuropathy was more frequent in females (11.9%) than in males (7.8%), higher in uncontrolled glycemic patients (14.5%) than in controlled patients (6.5%), and more common among those who are physically inactive (14.1%) compared to those who are active (8.1%). Food restrictions had little effect, but neuropathy was less common in overweight (5.8%) and obese patients (6.3%) compared to those with a normal BMI (14.3%). Prevalence peaked in the youngest age group (18–34) at 17.6% and was highest in late-stage diabetes (15.1%). Retinopathy affected 24.6% of females and 12.9% of males, was higher in uncontrolled glycemic patients (27.0%) versus controlled (12.7%), and was more prevalent in college-educated patients (22.2%). It was found in 14.9% of patients adhering to dietary recommendations, compared to 28.7% of non-adherent patients, and was higher in those with occupations such as business (33%). Age groups 18–34 and > 60 showed the highest rates (45.9% and 24.3%, respectively). BMI and physical activity had less clear trends. Cardiac comorbidities were observed in 27.7% of males and 15.3% of females, with the highest prevalence in farmers (37.8%) and those older than 60 years (36%). Rates were similar between controlled (21.9%) and uncontrolled glycemic groups (21.5%). Dietary adherence showed a slightly higher prevalence in adherent patients (23.7%) compared to non-adherent (16.3%). Physical activity and food restrictions showed no significant trends. Education was significantly associated with the highest cardiac rates among secondary educated patients (29.8%).

Chi-square tests showed that multiple factors showed a significant association with specific diabetic comorbidities. Hypertension was linked to gender, glycemic control, physical activity, adherence to dietary recommendations, body mass index (BMI), duration of diabetes, food restrictions, and age. Diabetic nephropathy was strongly linked to glycemic control, physical activity, occupation, dietary adherence, duration of diabetes, food restrictions, and age. Neuropathy showed significant relationships with glycemic control, physical activity, BMI, duration of diabetes, and age. Retinopathy was associated with gender, glycemic control, occupation, dietary adherence, duration of diabetes, and age. Cardiac was linked to gender, education, occupation, duration of diabetes, and age. These significant factors were afterwards used as predictors in the logistic regression models to assess their impact on the likelihood of developing each comorbidity (Table 1).

The logistic regression analysis revealed significant associations between patient characteristics and diabetes-related comorbidities with both AORs and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) reported to enhance the interpretability and precision of the findings. Males had higher odds of developing hypertension (AOR = 1.734; 95% CI: 1.077–2.791), and both poor adherence to dietitian-recommended plans (AOR = 2.04; 95% CI: 1.195–3.481) and uncontrolled glycemic status (AOR = 0.402; 95% CI: 0.256–0.631) were significant factors. Additionally younger respondents were less likely (AOR = 0.384; 95% CI: 0.211–0.698, AOR = 0.497; 95% CI: 0.277–0.892) to have hyper tension compare to their older counterparts. Cardiac comorbidities were more likely among individuals with lower education levels, with primary (AOR = 3.743; 95% CI: 1.696–8.258) and secondary (AOR = 2.986; 95% CI: 1.455–6.129) education being significant risk factors. Business professionals were less likely to experience cardiac comorbidities than retirees (AOR = 0.351; 95% CI: 0.139–0.887) and as well as younger respondents(AOR = 0.146; 95% CI: 0.043–0.493; AOR = 0.225; 95% CI: 0.102–0.498). Diabetic nephropathy was strongly linked to poor glycemic control (AOR = 2.220; 95% CI: 1.378–3.577), younger age groups, especially 35–50 years (AOR = 14.292; 95% CI: 6.36–32.19), showed significantly higher odds and avoided harmful foods (AOR = 0.607; 95% CI: 0.385–0.957) was associated with lower likelihood. Retinopathy risk was reduced among those who followed dietary plans (AOR = 0.525; 95% CI: 0.297–0.828), while younger adults (35–50 years) were also less likely to be affected (AOR = 0.310; 95% CI: 0.127–0.759) as well as farmers (AOR = 0.275; 95% CI: 0.079–0.949). Neuropathy was more frequent among patients with normal BMI (AOR = 4.442; 95% CI: 1.555–12.689) and those with a disease duration of over six years, whereas early-stage (AOR = 0.329; 95% CI: 0.115–0.940) and mid-stage (AOR = 0.195;95% CI: 0.075–0.510) diabetes had a protective effect (Table 2).

Table 2.

Binary logistic regression results for factors associated with comorbidities of patients with T2DM

| Variable | Hypertension (AOR: 95% CI: Lower-Upper) |

Cardiac (AOR: 95% CI: Lower-Upper) |

Diabetic nephropathy (AOR: 95% CI: Lower-Upper) |

Diabetic Retinopathy (AOR: 95% CI: Lower-Upper) |

Diabetic Neuropathy (AOR: 95% CI: Lower-Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Male Vs FemaleR) |

1.734** (1.077–2.791) |

1.260 (0.537–2.955) |

1.128 (0.451–2.882) |

||

| Primary education Vs College/universityR | 3.743**(1.696–8.258) | ||||

| Secondary school Vs College/universityR | 2.986**(1.455–6.129) | ||||

| Job Vs RetriedR | 0.644 (0.276–1.501) | 1.52(0.846–4.50.846.50) |

0.698 (0.241–2.018) |

||

| Business Vs RetriedR | 0.351 **(0.139–0.887) | 1.84(0.792–4.35) | 1.51 (0.53–4.254) | ||

| Farming Vs RetriedR | 1.382 (0.587–3.251) | 1.82(0.747–4.47) | 0.275 **(0.079–0.949) | ||

| Housewife Vs RetriedR | 0.647 (0.195–2.14) | 1.54(0.66–3.615) | 1.117 (0.315–3.958) | ||

| Exercise 30 min 5 days/week Yes Vs NoR | 1.135(0.67–1.921) | 0.813 (0.412–1.605) | |||

| Early stage (1 month − 3 years) Vs Late stage (more than 6 years) | 0.741(0.307–1.786) | 2.03 (0.98–4.209) | 1.053 (0.422–2.630) | 0.329** (0.115–0.940) | |

| Mid stage (3 to 6 years) Vs Late stage (more than 6 years)R | 1.211(0.661–2.22) | 1.36 (0.739–2.51) | 1.17 (0.571–2.397) | 0.195**(0.075–0.510) | |

| BMI category | |||||

| Normal weight Vs ObeseR | 0.714(0.381–1.337) | 4.442**(1.555–12.689) | |||

| Overweight Vs ObeseR | 1.352 (0.722–2.53) | 1.261 –(0.403–3.940) | |||

| GC(Unontrol Vs ControlR) |

0.402** (0.256–0.631) |

2.220** (1.378–3.577) | 0.795(0.445–1.421) | 0.398* (0.195–0.812) | |

| Dietary plan recommended by dietician, (No Vs YesR) |

2.040 (1.195–3.481) |

1.147(0.687–1.914) | 0.525**(0.297–0.928) | ||

| Avoid food, (No Vs YesR) |

1.334 (0.854–2.084) |

0.607**(0.385–0.957) | |||

| Age categories | |||||

| 18–34 years Vs > 60 yearsR |

0.909(0.458- 1.804) |

0.146** (0.043–0.493) | 3.78** (1.14–10.06) | 2.415(0.902–6.46) | 0.2.572 (0.664–9.958) |

| 35–50 years Vs > 60 yearsR |

0.384 (0.211–0.698) |

0.225**(0.102-0.0.102.0.498) | 14.292** (6.36–32.190) | 0.310* (0.127–0.759) | 1.813 (0.575–5.715) |

| 51–60 years Vs > 60 yearsR |

0.497 (0.277–0.892) |

0.642(0.344–1.196) | 7.16* (3.31–15.49) | 0.606 (0.276–1.332) | 1.047(0.354–3.096) |

| Hosmer and Lemeshow test | Chi square value, 12.839(p = 0.117) | Chi square value, 11.367(p = 0.207) | Chi square value, 13.087 (p = 0.109) | Chi square value, 14.794(p = 0.06) | Chi square value, 17.329 (p = 0.27) |

| Nagelker R square | 0.174 | 0.182 | 0.309 | 0.242 | 0.157 |

N.B.: R reference case, AOR Adjusted odds ratio, CI Confidence interval

Discussion

The prevalence of diabetic nephropathy in this study was 40.4%, which is consistent with global estimates (35.3%) [19], suggesting that common risk factors such as poor glycemic control, hypertension, longer duration of diabetes, and limited screening for microvascular comorbidities were similarly prevalent in our study population [22, 23]. However, the slightly higher rate observed in our setting may also reflect context-specific challenges, such as delayed diagnosis, lower health literacy, or limited access to preventive care, which warrant further exploration. The prevalence of hypertension among diabetics in this study was 25.4%, near to a similar study with prevalence of (30.95%) [24]. This is due to limited chronic disease management in resource-poor settings may increase this burden [25]. The prevalence of diabetic neuropathy in this study was 9.8%, lower than in other reports (46% and 50.70%) possibly due to differences in diagnosis, disease duration, younger patients, or under diagnosis in resource-limited settings [26, 27]. Neuropathy is a common comorbidity linked to poor glycemic control and metabolic syndrome, and limited neurological assessments may have contributed to underreporting [28, 29]. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in this study was 18.5%, which was lower compared to reported in various international studies (42.2%) [30]. The slightly lower prevalence observed in the present study may have been due to shorter diabetes duration among participants, or under diagnosis resulting from limited access to ophthalmologic screening in some cases. The prevalence of cardiac comorbidities (21.1%) in this study aligns with similar regional findings (21%) [31], likely due to indistinguishable demographic characteristics, healthcare infrastructure and diagnostic practices may also contribute to this observed similarity.

Logistic regression analysis identified poor glycemic control as a significant risk factor for hypertension, diabetic nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy. This finding was aligned with previous findings that established a strong relationship between chronic hyperglycemia and the onset of both microvascular and macrovascular comorbidities [32–35]. Persistent hyperglycemia likely contributes to endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and direct damage to blood vessels and peripheral nerves, which collectively exacerbate comorbidity risk. Participants with lower education had a higher likelihood of experiencing cardiac comorbidities. This aligns with prior research indicating that lower education levels are often linked to limited health literacy, reduced self-management capacity, and poorer access to healthcare services, thereby increasing vulnerability to cardiovascular disease among individuals with diabetes [36]. Retired individuals exhibited higher odds of developing cardiac comorbidities and diabetic retinopathy compared to those engaged in business or farming. This may be attributed to post-retirement lifestyle changes such as reduced physical activity and increased sedentary behavior that negatively impact cardiovascular and retinal health, especially in individuals with underlying metabolic conditions. Similar associations have been reported in previous studies, which also found a higher prevalence of these comorbidities among retired individuals. Longer diabetes duration (> 6 years) was significantly associated with diabetic neuropathy, supported by a previous study [37, 38], which highlighted the cumulative effect of prolonged hyperglycemia in causing nerve damage through metabolic and ischemic pathways. Non-adherence to dietitian-recommended dietary plans was strongly linked to increased odds of hypertension and diabetic retinopathy. This finding was in line with previous studies [39, 40], which demonstrated that poor dietary practices undermine glycemic and blood pressure control, both critical in preventing diabetes-related comorbidities. Inadequate dietary management characterized by excess sodium, sugar, and saturated fats can accelerate vascular and retinal damage. Participants who did not avoid certain harmful foods were more likely to develop diabetic nephropathy. This finding in our study is supported by previous literature [41]. A diet high in sodium, processed foods, and animal proteins can place excessive strain on renal function, accelerating the progression of kidney disease. Older adults exhibited significantly higher odds of hypertension and cardiac Comorbidities, consistent with findings from a previous study [42–44]. Age-related vascular stiffening, impaired endothelial function, and cumulative exposure to hyperglycemia likely contribute to this elevated risk. Our finding that older age is associated with increased retinopathy prevalence aligns with previous research, which attributes this association to factors such as medication non-adherence, missed follow-up appointments, and inadequate anti-VEGF therapy. Conversely, younger diabetic individuals (35–50 years) showed a higher risk of diabetic nephropathy, likely due to early-onset diabetes leading to longer disease duration and worsening of blood lipid metabolism. Similar findings have been reported in other studies, which also observed increased nephropathy risk among younger adults with diabetes [45].

Strengths and limitations

This study effectively addresses a major public health concern by focusing on comorbidities of patients with T2DM, covering both macrovascular (nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy) and microvascular (hypertension, cardiac disease) comorbidities. It offers comprehensive health profiling by assessing multiple comorbid conditions within a single study. However, this study’s cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships between outcomes and predictors. We also acknowledge potential biases. Selection bias may have occurred due to the snowball sampling method; however, we minimized this by using multiple initial contacts and involving local health personnel to reach a more diverse and representative sample. Recall and reporting bias from self-reported information was mitigated through a pre-tested questionnaire, interviews conducted in participants’ preferred language, and thorough interviewer training to ensure consistency.

Conclusion

This study highlights a substantial burden of both microvascular and macrovascular comorbidities among individuals with T2DM, with diabetic nephropathy being the most prevalent. Revealing demographic factors, lifestyle behaviors, and disease characteristics significantly influence the risk of developing hypertension, cardiac, nephropathy, retinopathy, and neuropathy among patients with T2DM. Addressing modifiable factors such as dietary adherence and glycemic control could substantially reduce comorbidity rates and improve patient outcomes. Meanwhile, targeted interventions focusing on education, early screening, and personalized care for high-risk groups are crucial to effectively managing and preventing diabetes-related comorbidities.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Health Coordinator, Health Post Incharge, Administrative Officer, and community political leaders for their invaluable support and cooperation to collect the data for this study. The authors are thankful to all study participants and staff for their contributions. ChatGPT 4.0 was used to improve readability and language of the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: NKC, MGHData curation: NKC, MMFormal analysis: NKC, MM, MGHFunding acquisition: No funding to reportInvestigation: MGHMethodology: NKC, MM, MGHProject administration: MGHResources: MGHSoftware: NKC, MMSupervision: MGHValidation: MGHVisualization: MMWriting – original draft: NKC, MMWriting – review & editing: NKC, MM, MGH.

Funding

There was no grant, technical or corporate support for this study.

Data availability

This study was based on the primary data. The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC), Government of Nepal (Ref. No.: 2925, dated May 2, 2023). Participants were explained about the objective of the study, and informed consent was documented.

Consent for publication

Not applicable for this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Narayan KMV, Gregg EW, Fagot-Campagna A, Engelgau MM, Vinicor F. Diabetes: a common, growing, serious, costly, and potentially preventable public health problem. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;50(Suppl 2):S77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes.. 2022 [cited 2022 Jan 25]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/index.html

- 4.Spiegel K, Leproult R, Van Cauter E. Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function. Lancet. 1999;354:1435–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM, Newman AB, Resnick HE, Redline S, Baldwin CM, et al. Association of sleep time with diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:863–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ko GT, Chan JC, Chan AW, Wong PT, Hui SS, Tong SD, et al. Association between sleeping hours, working hours and obesity in Hong Kong Chinese: the better health for better Hong Kong health promotion campaign. Int J Obes (Lond). 2007;31:254–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaturvedi N. The burden of diabetes and its comorbidities: trends and implications for intervention. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;76(Suppl 1):S3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmet P. Preventing diabetic comorbidities: a primary care perspective. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;84:107–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raheja BS, Kapur A, Bhoraskar A, Sathe SR, Jorgensen LN, Moorthi SR, et al. DiabCare asia: India study: diabetes care in India – current status. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:717–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 10th ed.. 2021 [cited 2022 Jan 25]. Available from: https://www.diabetesatlas.org

- 12.Maruthur NM, Tseng E, Hutfless S, Wilson LM, Suarez-Cuervo C, Berger Z, et al. Diabetes medications as monotherapy or metformin-based combination therapy for type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(6):413–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohan V, Deepa M, Deepa R. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its association with microvascular comorbidities in type 2 diabetes: the Chennai urban rural epidemiology study (CURES-34). Diabetes Technol Ther. 2007;9(3):319–27. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic comorbidities. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(1):137–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beckman JA, Creager MA, Libby P. Diabetes and atherosclerosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. JAMA. 2002;287(19):2570–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Central Bureau of Statistics. National Population and Housing Census. 2021.. 2022 [cited 2022 Jan 25]. Available from: https://censusnepal.cbs.gov.np

- 17.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th edn. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, 2021. Available at: https://diabetesatlas.org

- 18.World Health Organization. Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia: report of a WHO/IDF consultation. Geneva: WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abu Al-Halaweh A, Davidovitch N, Almdal TP, Cowan A, Khatib S, Nasser-Eddin L, et al. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus comorbidities among Palestinians with T2DM. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2017;11(Suppl 2):S783–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Government of Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics. National Population and Housing Census 2011: National Report. Kathmandu: CBS. 2012. [Available from: https://cbs.gov.np]

- 21.Wagnew F, Eshetie S, Kibret GD, Zegeye A, Dessie G, Mulugeta H, et al. Diabetic nephropathy and hypertension in diabetes patients of sub-Saharan countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Afkarian M, Zelnick LR, Hall YN, et al. Clinical manifestations of kidney disease among US adults with diabetes, 1988–2014. JAMA. 2016;316(6):602–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas MC, Brownlee M, Susztak K, et al. Diabetic kidney disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akalu Y, Belsti Y. Hypertension and its associated factors among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients at Debre Tabor general hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:1621–31. 10.2147/DMSO.S254537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adler AI, Stratton IM, Neil HA, et al. Association of systolic blood pressure with macrovascular and microvascular comorbidities of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 36): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321(7258):412–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shiferaw WS, Akalu TY, Work Y, et al. Prevalence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Endocr Disord. 2020;20:49. 10.1186/s12902-020-0534-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrei Cristian B, Amorin Remus P. Diabetic neuropathy prevalence and its associated risk factors in two representative groups of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus patients from Bihor County. Maedica (Bucur). 2018;13(3):229–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boulton AJM, Vinik AI, Arezzo JC, et al. Diabetic neuropathies: a statement by the American diabetes association. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(4):956–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ejigu T, Tsegaw A. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and risk factors among diabetic patients at University of Gondar tertiary eye care and training center, North-West Ethiopia. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2021;28(2):71–80. 10.4103/meajo.meajo_24_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Einarson TR, Acs A, Ludwig C, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review of scientific evidence from across the world in 2007–2017. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:83. 10.1186/s12933-018-0728-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HAW, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular comorbidities of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321(7258):405–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ang L, Jaiswal M, Martin C, Pop-Busui R. Glucose control and diabetic neuropathy: lessons from recent large clinical trials. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14(9):528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galindo RJ, Beck RW, Scioscia MF, Umpierrez GE, Tuttle KR. Glycemic monitoring and management in advanced diabetic nephropathy. Endocr Rev. 2020;41(5):756–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee K, Lee GH, Lee SE, Yang JM, Bae K. Glycemic control and retinal microvascular changes in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients without clinical retinopathy. Diabetes Metab J. 2024;48(5):983–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan N, Javed Z, Acquah I, et al. Low educational attainment is associated with higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the united States adult population. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li W, Yu K, Jia N, et al. Past shift work and incident coronary heart disease in retired workers: a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2021;190(9):1821–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mørkrid K, Ali L, Hussain A. Risk factors and prevalence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a study of type 2 diabetic outpatients in Bangladesh. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2010;30(1):11–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abera B, Yazew T, Legesse E, et al. Dietary adherence and associated factors among hypertensive patients in governmental hospitals of Guji zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. J Health Popul Nutr. 2024;43:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dow C, et al. Diet and risk of diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review. Eur J Epidemiol. 2018;33(2):141–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu SS, Hua J, Huang YQ, Shu L. Association between dietary patterns and diabetic nephropathy in a middle-aged Chinese population. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23(6):1058–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao X, Zhang J, Zhang X, et al. Age at diagnosis, diabetes duration and the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes mellitus: a cross-sectional study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1131395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clua-Espuny JL, González-Henares MA, Queralt-Tomas MLL, et al. Mortality and cardiovascular comorbidities in older complex chronic patients with type 2 diabetes. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:6078498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leley SP, Ciulla TA, Bhatwadekar AD. Diabetic retinopathy in the aging population: a perspective of pathogenesis and treatment. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:1367–78. 10.2147/CIA.S297494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng L, Chen X, Luo T, Ran X, Hu J, Cheng Q, et al. Early-onset type 2 diabetes as a risk factor for end-stage renal disease in patients with diabetic kidney disease. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:200076. 10.5888/pcd17.200076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This study was based on the primary data. The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.