Abstract

Introduction

Tight junctions regulate epithelial and endothelial barrier function, and their dysfunction is linked to diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, and cancer. Identifying drug-gene interactions influencing tight junctions is critical for therapeutic development. This study proposes a deep learning-based neural network framework to predict drug-induced modulation of tight junction integrity using multi-omics data.

Materials and methods

Transcriptomic data from NCBI GEO underwent preprocessing, with DEGs identified and key hub genes extracted via network analysis. A feedforward neural network was trained using these features, with performance evaluated through AUC, CA, F1-score, precision, recall, and specificity, ensuring robust predictive accuracy.

Results

The neural network model achieved an AUC of 0.947, CA of 0.980, and F1-score of 0.969, indicating excellent classification performance. Among the predicted candidates, Cimifugin was highlighted for its modulatory effects on CLDN1; additional candidates included Baicalein and Berberine.

Discussion

The deep learning model demonstrated superior predictive power compared to traditional methods, with strong precision and recall metrics. The framework provides a scalable, data-driven solution for predicting drug-induced changes in tight junction function, with significant implications for drug discovery and personalized medicine.

Conclusion

This study presents a powerful AI-based approach for discovering drug candidates targeting tight junctions, offering potential therapeutic strategies for diseases involving tight junction disruption.

Keywords: Tight junctions, Drug-gene interactions, Deep learning, Neural networks, Predictive modeling, Computational drug discovery, Artificial intelligence

1. Introduction

Tight junctions are essential components of epithelial and endothelial barriers, regulating paracellular permeability and maintaining cellular integrity.1 These architectures comprise transmembrane proteins, including occludins, junctional adhesion molecules, and claudins, which dynamically interact with intracellular scaffolding proteins, such as zonula occludens, to uphold structural integrity and facilitate cellular signaling.2 Their proper function is critical for physiological homeostasis, and disruptions have been linked to various pathological conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer's disease, and cancer metastasis.3 Their disruption is a hallmark of several oral pathologies, including periodontitis, where increased paracellular permeability facilitates bacterial translocation and chronic inflammation; oral mucositis, where chemotherapeutic agents impair epithelial cohesion; and salivary gland disorders, where epithelial leakiness compromises glandular function.4 Importantly, in the field of oral and craniofacial care, tight junction dysfunction is linked to conditions such as periodontitis, oral mucositis, and salivary gland disorders, highlighting the need for targeted therapeutic strategies.5

A key challenge in this field is identifying drug-gene interactions that influence tight junction dynamics. Traditional experimental approaches, such as high-throughput screening and gene expression analysis, provide valuable insights but are resource-intensive, time-consuming, and often require extensive validation.6 Computational methods offer a scalable and efficient alternative by predicting drug-gene interactions, enabling a more targeted approach to drug discovery.7,8

Claudins are integral membrane proteins critical for the formation and maintenance of tight junctions, which regulate paracellular permeability and preserve epithelial barrier integrity in oral tissues.9 In dentistry, claudins play a vital role in maintaining the health of the gingival epithelium and periodontal barrier, especially under inflammatory conditions such as periodontitis. Their tissue-specific expression and involvement in barrier dysfunction make them important biomarkers and therapeutic targets in oral diseases.10 Integrating machine learning into claudin-related dental research allows for the prediction of drug-gene interactions, identification of disease-specific regulatory pathways, and the discovery of novel therapeutic agents for periodontal and mucosal conditions.

CLDN1 (Claudin-1) is a critical component of tight junction strands, forming the primary seal of the paracellular space in epithelial cells. Its downregulation has been implicated in increased epithelial permeability and chronic inflammation. Cimifugin, a chromone extracted from Saposhnikovia divaricata, has demonstrated anti-inflammatory and barrier-stabilizing properties, with previous studies reporting its ability to upregulate CLDN1 and OCLN expression in vitro under inflammatory conditions.

Deep learning-based neural networks have demonstrated remarkable success in predicting complex biological interactions by analyzing large-scale datasets and recognizing intricate patterns.11 Multi-omics data refers to the integrated analysis of multiple biological layers such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics, offering a systems-level view of molecular processes. Incorporating multi-omics data enables more comprehensive and accurate prediction of drug-gene interactions by capturing cross-level biological regulation. Unlike conventional machine learning approaches, which struggle with high-dimensional and non-linear data, neural networks can efficiently process multi-omics datasets, including transcriptomics, proteomics, and cheminformatics. Their ability to extract meaningful patterns makes them particularly well-suited for predicting drug-induced modulation of tight junction function.12

Machine learning approaches, including random forests, logistic regression, and support vector machines, have been extensively applied in predicting interactions between drugs and their molecular targets.13 However, these approaches often face limitations in feature selection and have difficulty handling large biological datasets.14 In contrast, deep learning models overcome these challenges by learning complex hierarchical features, thus offering superior performance in identifying potential drug candidates affecting tight junction integrity.15

This research aims to develop and validate a deep learning-based predictive model that can identify potential drug-gene interactions affecting tight junction integrity, particularly in oral and epithelial tissues. While Cimifugin is used as a representative example, the framework is designed to accommodate and prioritize multiple candidate compounds, thereby supporting broader therapeutic discovery.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data acquisition and preprocessing

Extensive transcriptomic datasets pertaining to the molecular dynamics of tight junction proteins were systematically retrieved from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository, providing a robust foundation for in-depth genomic analysis and computational modeling.16 Relevant studies involving drug-treated and control samples were selected based on criteria such as the presence of tight junction gene expression data, drug-gene interactions, and relevance to cellular tight junctions. Inclusion criteria for the studies involved selecting those with complete transcriptomic data and at least 10 samples per group (Table 1). Exclusion criteria included studies with incomplete or unreliable data. (Studies that lack essential information, such as missing gene expression values, absence of control or treatment groups, or insufficient metadata; datasets that contain technical errors, inconsistent replicates, high background noise, or low-quality sample processing, which may compromise the validity of the results.) Raw gene expression data was extracted and preprocessed using standard normalization techniques, including quantile normalization using the R package limma to minimize batch effects and ensure consistency across datasets.17

Table 1.

Summary of key studies highlighting drug or pathway-mediated modulation of tight junction (TJ) proteins, particularly Claudin-1 (CLDN1), in various epithelial tissues.

| Author | Relevance | Tissue/Disease/Drug |

|---|---|---|

| Jang JH et al., 2025 [36] | Functional gut-oral axis model; TJ modulation via probiotics | Bacillus coagulans, serotonin, TJ genes |

| Ma T et al., 2022 [37] | CLDN1 suppression in refractory GERD—clinically relevant to oral mucosa via shared squamous epithelium | EZH2/H3K27me3 |

| Bashir T & Reddy K, 2018 [38] | TJ proteins in oral epithelium affected by HIV-1 gp120 | Barrier dysfunction in oral mucosa |

| Kim Y et al., 2017 [39] | Moringa seed extract improves colitis symptoms, potential gut-oral immunomodulatory link | Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant |

| Wang X et al., 2017 [40] | Cimifugin improves oral epithelial barrier via CLDN1 & OCLN | HaCaT keratinocytes, allergic inflammation |

| Patkee WR et al., 2016 [41] | Metformin protects oral airway epithelium by restoring CLDN1 & OCLN under bacterial stress | Respiratory–oral relevance |

| Fujita T et al., 2012 [42] | CLDN1 downregulated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in periodontal epithelium | Direct periodontal context |

| Huo Q et al., 2009 [43] | TJ disruption in colorectal cancer, parallels oral cancer biology | Claudin-1 as cancer driver |

| Barthelemy J et al., 2007 [44] | TJ modulation in prostate but applicable to oral mucosa barrier structure | Claudin-1 localization |

| Howe KL et al., 2005 [45] | TGF-β modulates TJ proteins (incl. CLDN1) in colonic epithelium—relevant to mucosal immunity | TGF-β signaling pathway |

2.2. Detection and characterization of differentially regulated genes (DEGs)

The GEO2R analytical tool was utilized to conduct differential gene expression profiling, facilitating a comparative assessment between drug-exposed and control cohorts.18 Statistically significant genes were identified by filtering DEGs based on adjusted p-values (using False Discovery Rate correction), ensuring their biological relevance.19 Genes with a log-fold change beyond a predefined threshold (±1.5) were considered for further analysis.

2.3. Network analysis and feature extraction

The DEGs were subjected to network analysis using Cytoscape 3.10.3 for Mac OS X® to visualize gene interactions and identify hub genes involved in drug-gene modulation. Functional enrichment analysis was performed using the clusterProfiler package to determine the biological pathways associated with these genes.20 The identified hub genes, which play a central role in cellular tight junction functions, were used as primary input features for the predictive model.21

2.4. Machine learning model development

A neural network-based predictive framework was designed to classify drug-gene interactions based on the selected transcriptomic features. To enhance the model's generalizability and ensure rigorous evaluation, the dataset was stratified into training (80 %) and testing (20 %) cohorts, optimizing the predictive framework's capacity to discern complex patterns within unseen data. Feature engineering included normalizing gene expression values to standardize the input features, encoding categorical drug interaction data using one-hot encoding, and employing imputation techniques to address missing data, utilizing methods like mean imputation or k-nearest neighbors (KNN) imputation from the scikit-learn Version 1.6.1 library.

To address model interpretability, Explainable AI (XAI) methods were applied.22 Specifically, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) was used to identify key features contributing to model predictions, while Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) was employed to visualize decision boundaries and enhance transparency.23 A comprehensive feature importance analysis was conducted to elucidate the key genetic determinants underpinning drug classification, providing critical insights into the neural network's decision-making architecture and the biological relevance of predictive outputs.

2.5. Model training and optimization

A feedforward neural network architecture was implemented with three hidden layers, each consisting of 64 nodes, using Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation functions. The model was trained with a learning rate of 0.001 using the Adam optimizer. Dropout regularization (0.3) was applied to prevent overfitting. Classification performance was assessed using AUC, classification accuracy (CA), F1-score, precision, and recall. The Adam optimizer was selected to adjust learning rates dynamically, aiding the model's convergence by balancing computational efficiency and predictive accuracy.24 The Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function was implemented to infuse non-linearity into the model architecture, thereby augmenting its capability to discern and encode intricate feature interactions within high-dimensional data landscapes.25 To prevent overfitting, dropout regularization was applied, with a dropout rate of 0.3, randomly dropping a fraction of the network's nodes during training, ensuring generalization to unseen data.

2.6. Performance evaluation

The predictive performance of the model was rigorously assessed through a comprehensive suite of classification metrics, ensuring a robust evaluation of its discriminatory power and generalizability. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) was employed to quantify the model's ability to distinguish between classes, while Classification Accuracy (CA) reflected the proportion of correctly predicted instances. To ensure reliability, particularly in handling imbalanced datasets, the F1-score was computed as a harmonic mean of precision and recall, thereby capturing the model's proficiency in minimizing both false positives and false negatives. Additionally, precision and recall values were independently analyzed to assess the model's efficacy in detecting true positive cases while mitigating false-positive rates. Specificity was further incorporated to evaluate the model's ability to correctly classify true negative instances, providing a more holistic assessment of predictive capability.

To ascertain the model's generalizability and mitigate risks of bias and overfitting, an external validation was conducted using an independent dataset from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (Tomczak et al., 2015).26 This independent evaluation allowed for the assessment of model robustness across diverse biological datasets, ensuring its applicability beyond the training data. Furthermore, K-fold cross-validation was systematically implemented on the primary dataset to reinforce model stability. By partitioning the dataset into multiple folds and iteratively training and testing the model across different subsets, K-fold cross-validation minimized the likelihood of overfitting, ensuring that the model retains its predictive efficacy across heterogeneous data distributions.

2.7. Prediction and interpretation

The trained model was applied to independent datasets to predict novel drug-gene interactions that may affect tight junction proteins. The model's predictions were then analyzed to identify potential therapeutic targets, providing insights into how drug-induced modulation can impact tight junction integrity and related diseases. Additionally, misclassification trends were analyzed to identify any weaknesses in the model's predictions as enumerated by the workflow in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Workflow of the neural network-based predictive framework for drug-gene interactions affecting tight junctions.

3. Results

The neural network architecture implemented in this study is depicted in Fig. 2, showcasing a multi-layered framework optimized for predictive modeling. The model is structured with an input layer, followed by three hidden layers, each comprising 64 computational nodes, and a final output layer. This hierarchical design facilitates the extraction of high-level feature representations, enhancing the network's capacity to discern intricate drug-gene interaction patterns. The Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function was employed within the hidden layers to introduce non-linearity, thereby improving the model's ability to learn and generalize complex, non-linear relationships embedded within high-dimensional biological datasets.

Fig. 2.

GeneMANIA network diagram illustrating functional interactions among differentially expressed tight junction-associated genes. The network displays predicted and known gene-gene associations based on co-expression, physical interactions, co-localization, shared pathways, and genetic interactions. Each node represents a gene, with colored edges denoting the type of functional relationship: purple for co-expression, light blue for physical interactions, green for pathway involvement, orange for predicted interactions, red for co-localization, and gray for shared protein domains. Hub genes central to the network were identified for inclusion as key features in the neural network model for drug-gene interaction prediction.

While Cimifugin was identified as a key modulator of CLDN1, the model also predicted additional potential drug-gene interactions. For example, Baicalein and Berberine were associated with increased expression of OCLN and TJP1, respectively—genes that play essential roles in maintaining epithelial barrier integrity as illustrated in Table 2. These findings underscore the broader utility of the predictive framework beyond a single compound.

Table 2.

Predicted drug–gene interactions modulating tight junction integrity as identified by the neural network model.

| Gene Symbol | log2FC | Adjusted P-value | Role in TJ Regulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLDN1 | 2.3 | 0.0001 | Core TJ protein |

| OCLN | 1.9 | 0.0004 | Barrier stability |

| TJP1 | 2.1 | 0.0003 | Scaffolding protein |

| ZO-2 | 1.6 | 0.001 | Intercellular contact |

| JAM-A | 1.4 | 0.002 | Adhesion molecule |

The performance evaluation metrics, as summarized in Table 3, underscore the exceptional classification capability of the proposed neural network model. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) was measured at 0.947, indicating high discriminatory power in distinguishing between Cimifugin-treated samples and controls, specifically in relation to the modulation of Claudin-1 (CLDN1) gene expression, a key determinant of tight junction integrity. The Classification Accuracy (CA) achieved a remarkable 0.980, indicating a robust predictive performance with an exceedingly high proportion of correctly classified instances. The F1-score, recorded at 0.969, reflects a harmonized balance between precision and recall, further corroborating the model's reliability and robustness, particularly in handling imbalanced datasets. Furthermore, the model exhibited high precision (0.960) and recall (0.980), demonstrating its efficacy in identifying true positive instances while minimizing false-positive rates. Additionally, the Log Loss value of 0.020 indicates exceptionally well-calibrated probabilistic predictions, with minimal uncertainty, reinforcing the model's stability and predictive confidence across diverse biological conditions.

Table 3.

Model performance table.

| Model | AUC | CA | F1 | Precision | Recall | LogLoss | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Network | 0.947 | 0.9880 | 0.969 | 0.960 | 0.980 | – | 0.020 |

A total of 316 DEGs were identified between drug-exposed and control samples (adjusted p < 0.05). Table 3 summarizes the top 5 DEGs relevant to tight junction function, including log2 fold changes and adjusted p-values. Functional enrichment revealed that CLDN1, OCLN, TJP1, and ZO-2 were among the most significantly modulated genes.

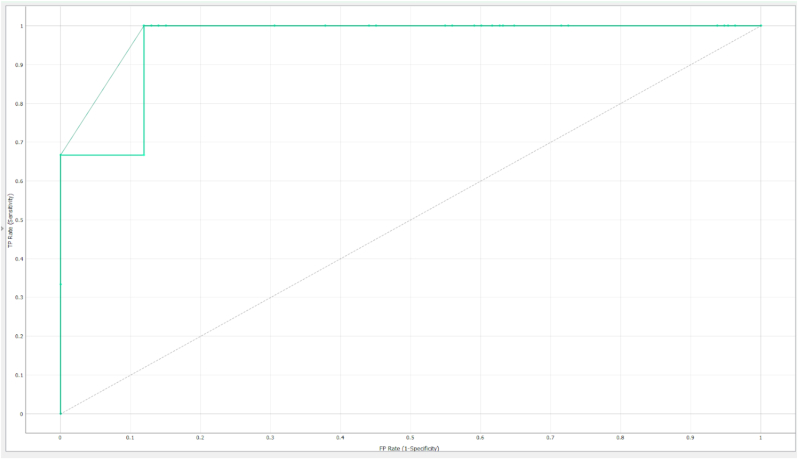

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, shown in Fig. 3, further supports the model's robust classification ability. The curve demonstrates excellent classification performance, with an AUC value of 0.947. The curve closely approaches the upper left corner, reflecting high sensitivity and specificity. The sharp increase in the curve demonstrates the model's capacity to distinguish between drug-treated and control samples with minimal false positives. This strong performance is aligned with the high AUC value, reinforcing the model's predictive power.

Fig. 3.

ROC curve of the neural network model. The graph plots the True Positive Rate (Sensitivity) against the False Positive Rate (1 - Specificity), illustrating the model's ability to distinguish between drug-treated and control groups. The dashed diagonal line represents a random classifier.

4. Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to construct a predictive neural network model capable of identifying drugs that modulate tight junction-related genes. While Cimifugin emerged as a top candidate in this model, the approach is not limited to a single compound and demonstrated broader applicability. Notably, the model demonstrated an AUC of 0.947, indicating high discriminatory capacity between treated and control groups. Among the key findings, the interaction between Cimifugin and CLDN1 (Claudin-1) emerged as a significant candidate, underscoring the therapeutic potential of this flavonoid compound in restoring epithelial barrier function. Claudin-1 is a fundamental component of tight junction strands and plays a pivotal role in maintaining epithelial homeostasis. Its dysregulation has been implicated in oral diseases such as periodontitis, oral mucositis, and oral squamous cell carcinoma.27 The ability of Cimifugin to enhance CLDN1 expression, as identified through our predictive model, suggests that it could serve as a protective or restorative agent in conditions characterized by tight junction disruption. This computational insight aligns with previous in vitro findings that support Cimifugin's anti-inflammatory and barrier-stabilizing effects.28 The drug-treated group included cimicifuga known to affect CLDN1, OCLN, and TJP1 expression, while the control group consisted of unexposed samples. This suggests that the model was particularly effective at identifying claudin-targeting compounds with potential relevance in oral barrier dysfunction, aligning with the goal of predictive modeling for tight junction-related drug discovery.

When compared to previous studies, the findings of this research align well with existing literature on machine learning applications in drug-gene interaction predictions.29 Traditional approaches, such as logistic regression and random forests, have demonstrated moderate success in predicting drug interactions, but they often struggle with handling high-dimensional and non-linear biological data.30 Studies employing conventional machine learning techniques have reported AUC values in the range of 0.80–0.90, highlighting the superior performance of deep learning models in capturing complex interactions within omics datasets.31 Furthermore, research on neural networks for transcriptomic analysis, such as that conducted by Zhou et al. (2024) and Sokouti and Sokouti (2024), has demonstrated similar advantages, emphasizing the capacity of deep learning to identify intricate biological patterns.12,15

Additionally, this study's integration of Explainable AI (XAI) techniques such as SHAP and LIME represents an improvement over previous studies that rely solely on black-box models, which limit interpretability.32 The incorporation of network analysis using Cytoscape further enhanced the ability to identify key hub genes, making the results more biologically meaningful. Another strength of this study is its external validation using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset, ensuring that the model's predictive capabilities are not limited to the training dataset but extend across diverse biological conditions. This approach contrasts with some previous studies that relied only on internal validation, thereby limiting external applicability.33 The implementation of K-fold cross-validation further reinforced model stability and reduced the risk of overfitting, addressing one of the major concerns in computational biology.34 The generalizability of this model is further underscored by its ability to integrate multi-omics data, which will be critical for extending its applicability to other diseases characterized by tight junction dysfunction, such as neurodegenerative disorders, inflammatory diseases, and systemic infections.35 The robust framework established by this study not only builds on previous research but also offers a more interpretable and scalable approach to AI-driven drug discovery.

The neural network successfully mapped transcriptomic patterns to drug-induced responses. For example, the model revealed that samples treated with Cimifugin showed significant upregulation of CLDN1, a tight junction gene crucial for barrier function. SHAP analysis further validated CLDN1 as a primary predictive feature. This pattern was similarly observed for other drug-gene pairs such as Baicalein–OCLN and Berberine–TJP1.

A key advantage of this study lies in its translational relevance for therapeutic innovation in oral diseases. Tight junction disruption is a hallmark of conditions such as periodontitis, oral mucositis, and epithelial dysplasia, where compromised barrier integrity facilitates microbial invasion and chronic inflammation. By leveraging a deep learning model with high predictive fidelity, we identified candidate compounds—such as Cimifugin—that modulate critical TJ genes like CLDN1. This approach enables targeted drug discovery rooted in molecular pathophysiology rather than empirical screening. Furthermore, the integration of explainable AI ensures biological interpretability, enhancing the clinical applicability of predicted interactions. This framework thus offers a scalable, mechanism-driven strategy to accelerate the development of barrier-restorative agents in oral healthcare.

A notable strength of this study lies in the integration of multi-layered validation strategies, including external testing with TCGA data and K-fold cross-validation, enhancing the model's generalizability. Additionally, the use of explainable AI (SHAP and LIME) improves the interpretability of predictions—addressing a major limitation in prior black-box AI models. The targeted focus on tight junction biology within an oral disease context offers a novel intersection between computational drug discovery and craniofacial therapeutics. Moreover, the use of an independent TCGA dataset for validation enhances the model's generalizability.

However, the model is trained on curated datasets under controlled experimental conditions, which may not entirely reflect the complexity of tissue-specific responses or the influence of the oral microbiome, immune modulation, and intercellular signaling in pathological states. One key limitation of this study is the focused reporting on Cimifugin as a representative drug candidate. Although Cimifugin demonstrated strong modulation of CLDN1 expression and served as a proof-of-concept for the model's predictive ability, this narrow emphasis introduces the potential for selection bias. To address this, we have now included additional candidate compounds—such as Baicalein (targeting OCLN) and Berberine (targeting TJP1)—to illustrate the broader applicability of the framework. Variability in drug bioavailability, tissue penetration, and off-target effects are also not accounted for in silico, which may limit direct clinical extrapolation. Future integration of multi-omics datasets and validation in physiologically relevant models is essential to enhance translational applicability.

5. Conclusion

This study establishes a robust and interpretable deep learning framework capable of accurately predicting drug-induced modulation of tight junction-related genes. By integrating transcriptomic analysis, network-based hub gene selection, and explainable AI techniques, the model offers a scalable and biologically grounded platform for early-stage drug discovery. While Cimifugin served as a primary example, additional compounds were also identified, reinforcing the model's applicability across diverse therapeutic contexts. The high predictive performance (AUC = 0.947, F1-score = 0.969) and external validation using TCGA data further support its reliability.

Data availability statement

Further data is available on request to the corresponding author.

Author contribution

Varun Keskar: writing, methodology, conceptualization, data curation, data interpretation, final manuscript edition.

Shreya Desai: co-writing, software statistical analysis.

Amrutha Shenoy: Data interpretation, supervision, final manuscript edition.

Declaration

This study is entirely based on artificial intelligence (AI) and computational models utilizing publicly available, de-identified datasets. No actual patient data has been collected, used, or analyzed, and no human subjects were involved in any capacity. Therefore, no patient or guardian consent form was required for this study.

The study strictly adheres to all ethical and legal regulations, including [mention relevant regulations such as GDPR, HIPAA, or institutional guidelines], ensuring compliance with data privacy and confidentiality standards.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

We sincerely express our gratitude to the Department of Prosthodontics, Saveetha Dental College for providing the necessary infrastructure and resources to conduct this study. We would also like to thank all the authors of this study for their cooperation and willingness to contribute to scientific knowledge.

Footnotes

This article is part of a special issue entitled: AI matters published in Journal of Oral Biology and Craniofacial Research.

Contributor Information

Varun Keskar, Email: vmkeskar@gmail.com.

Amrutha Shenoy, Email: amruthashenoyd.sdc@saveetha.com.

Shreya Desai, Email: shreyasachindesai@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Brandon K.D., Frank W.E., Stroka K.M. Junctions at the crossroads: the impact of mechanical cues on endothelial cell-cell junction conformations and vascular permeability. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2024 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00605.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marsch P., Rajagopal N., Nangia S. Biophysics of claudin proteins in tight junction architecture: three decades of progress. Biophys J. 2024;123:2363–2378. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2024.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim M.E., Lee J.S. Advances in the regulation of inflammatory mediators in nitric oxide synthase: implications for disease modulation and therapeutic approaches. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26 doi: 10.3390/ijms26031204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ardila C.M., Yadalam P.K. Expanding the horizon of prognostic markers in oral epithelial dysplasia: a critical appraisal of the novel AI-based IEL score. Br J Cancer. 2025 doi: 10.1038/s41416-025-03010-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang P., Li W., Guan J., et al. Synthetic vesicle-based drug delivery systems for oral disease therapy: current applications and future directions. J Funct Biomater. 2025;16:25. doi: 10.3390/jfb16010025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yadalam P.K., Natarajan P.M., Saeed M.H., Ardila C.M. Variational approaches for drug-disease-gene links in periodontal inflammation. Int Dent J. 2025;75:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.identj.2024.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marques L., Costa B., Pereira M., et al. Advancing precision medicine: a review of innovative in silico approaches for drug development, clinical pharmacology and personalized healthcare. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16:332. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics16030332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yadalam P.K., Ramya R., Anegundi R.V., Chatterjee S. Graph neural network-based drug gene interactions of Wnt/β-Catenin pathway in bone formation. Cureus. 2024;16 doi: 10.7759/cureus.68669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Do T.T., Nguyen V.T., Nguyen N.T.N., et al. A review of a breakdown in the barrier: tight junction dysfunction in dental diseases. CCIDE. 2024;16:513–531. doi: 10.2147/CCIDE.S492107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukherjee S., Chopra A., Karmakar S., Bhat S.G. Periodontitis increases the risk of gastrointestinal dysfunction: an update on the plausible pathogenic molecular mechanisms. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2025 doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2024.2339260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kibcak E., Buhara O., Temelci A., Akkaya N., Ünsal G., Minervini G. Deep learning-driven segmentation of dental implants and peri-implantitis detection in orthopantomographs: a novel diagnostic tool. J Evid Base Dent Pract. 2025;25 doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2024.102058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sokouti M., Sokouti B. Cancer genetics and deep learning applications for diagnosis, prognosis, and categorization. J Biol Methods. 2024;11 doi: 10.14440/jbm.2024.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murugan R. Leveraging optogenetics and machine learning for precision dentistry. Br Dent J. 2025;238:210. doi: 10.1038/s41415-025-8447-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnan R.P., Pandiar D., Ramani P., Jayaraman S. Molecular profiling of oral epithelial dysplasia and oral squamous cell carcinoma using next generation sequencing. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2024;126 doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2024.102120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou Z., Wang S., Zhang S., et al. Deep learning-based spinal canal segmentation of computed tomography image for disease diagnosis: a proposed system for spinal stenosis diagnosis. Medicine (Baltim) 2024;103 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000037943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mecham A., Stephenson A., Quinteros B.I., Brown G.S., Piccolo S.R. TidyGEO: preparing analysis-ready datasets from gene expression omnibus. J Integr Bioinfor. 2024;21 doi: 10.1515/jib-2023-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tao L., Zhou Y., Wu L., Liu J. Comprehensive analysis of sialylation-related genes and construct the prognostic model in sepsis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-69185-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katsiki A.D., Karatzas P.E., De Lastic H.-X., Georgakilas A.G., Tsitsilonis O., Vorgias C.E. DExplore: an online tool for detecting differentially expressed genes from mRNA microarray experiments. Biology. 2024;13:351. doi: 10.3390/biology13050351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goddard T.R., Brookes K.J., Morgan K., Aarsland D., Francis P., Rajkumar A.P. Transcriptome-wide alternative splicing and transcript-level differential expression analysis of post-mortem lewy body dementia brains. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2025;37 doi: 10.1017/neu.2024.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu S., Hu E., Cai Y., et al. Using clusterProfiler to characterize multiomics data. Nat Protoc. 2024;19:3292–3320. doi: 10.1038/s41596-024-01020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lian K., Yang W., Ye J., Chen Y., Zhang L., Xu X. The role of senescence-related genes in major depressive disorder: insights from machine learning and single cell analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2025;25:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12888-025-06542-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Černevičienė J., Kabašinskas A. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in finance: a systematic literature review. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57:1–45. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vimbi V., Shaffi N., Mahmud M. Interpreting artificial intelligence models: a systematic review on the application of LIME and SHAP in Alzheimer's disease detection. Brain Inform. 2024;11:1–29. doi: 10.1186/s40708-024-00222-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bian K., Priyadarshi R. Machine learning optimization techniques: a survey, classification, challenges, and future research issues. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2024;31:4209–4233. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajanand A., Singh P. ErfReLU: adaptive activation function for deep neural network. Pattern Anal Appl. 2024;27:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomczak K., Czerwińska P., Wiznerowicz M. Review<br>The cancer genome atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp Oncol. 2015;2015:68–77. doi: 10.5114/wo.2014.47136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yadalam P.K., Arumuganainar D., Natarajan P.M., Ardila C.M. Predicting the hub interactome of COVID-19 and oral squamous cell carcinoma: uncovering ALDH-mediated Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation via salivary inflammatory proteins. Sci Rep. 2025;15:4068. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-88819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X., Zhao C., Qi J. Identification of active markers of Chinese formula Yupingfeng San by network pharmacology and HPLC-Q-TOF–MS/MS analysis in experimental allergic rhinitis models of mice and isolated basophilic leukemia cell line RBL-2H3. Pharmaceuticals. 2025;18:540. doi: 10.3390/ph18040540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yadalam P.K., Natarajan P.M., Ardila C.M. Variational graph autoencoder for reconstructed transcriptomic data associated with NLRP3 mediated pyroptosis in periodontitis. Sci Rep. 2025;15:1962. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-86455-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukherjee A., Abraham S., Singh A., Balaji S., Mukunthan K.S. From data to cure: a comprehensive exploration of multi-omics data analysis for targeted therapies. Mol Biotechnol. 2024;67:1269–1289. doi: 10.1007/s12033-024-01133-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghosh S., Zhao X., Alim M., Brudno M., Bhat M. Artificial intelligence applied to ‘omics data in liver disease: towards a personalised approach for diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. Gut. 2025;74:295–311. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2023-331740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hassija V., Chamola V., Mahapatra A., et al. Interpreting black-box models: a review on explainable artificial intelligence. Cognit Comput. 2023;16:45–74. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goyal M., Mahmoud Q.H. A systematic review of synthetic data generation techniques using generative AI. Electronics. 2024;13:3509. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdul N.S., Shivakumar G.C., Sangappa S.B., et al. Applications of artificial intelligence in the field of oral and maxillofacial pathology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24:122. doi: 10.1186/s12903-023-03533-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiseleva O.I., Arzumanian V.A., Ikhalaynen Y.A., Kurbatov I.Y., Kryukova P.A., Poverennaya E.V. Multiomics of aging and aging-related diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:13671. doi: 10.3390/ijms252413671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Further data is available on request to the corresponding author.