Abstract

Tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) infiltration is associated with poor prognosis in human patients with melanoma. However, the mechanism by which TAMs infiltrate tumor tissues in dogs remains unclear. Therefore, the present study aimed to identify macrophage chemotactic factors involved in macrophage migration in canine oral malignant melanoma (OMM). We first analyzed RNA-seq data of canine OMM, then performed immunohistochemistry of OMM tissue, and finally performed a macrophage migration assay using factors secreted from a canine melanoma cell line. The RNA-seq and immunohistochemistry revealed high TAM infiltration in canine oral malignant melanoma. Migration assays were performed using macrophage cell lines and culture supernatants from seven canine melanoma cell lines to identify macrophage chemotactic factors. The analysis of chemokine expression in canine melanoma cell lines revealed a positive correlation between CXCL8 expression and macrophage migration. Furthermore, macrophage migration was significantly reduced by CXCL8 gene knockout and anti-CXCL8-neutralizing monoclonal antibody. Additionally, the addition of recombinant CXCL8 protein rescued the reduction in migratory macrophage cells caused by CXCL8 knockout. These findings indicate that CXCL8 plays a crucial role in macrophage migration and that targeting CXCL8 may be a novel therapeutic approach for canine melanoma.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-22749-x.

Keywords: Dog, CXCL8, IL-8, Macrophage, Migration, Melanoma

Subject terms: Chemotaxis, Cancer microenvironment, Oral cancer, Tumour immunology, Chemokines, Tumour immunology

Introduction

Canine melanoma commonly occurs in the oral cavity (62%), skin (27%), digits (6%), and subungual region (4%)1, with oral malignant melanoma (OMM) being the most common canine malignant oral tumor, accounting for 14.4–45.5% of all oral tumors2. The treatment of OMM focuses on local control through surgery and/or radiotherapy. However, metastatic cases have a poor prognosis. Although combined chemoradiotherapy has been well-studied, chemotherapy offers no significant survival benefit3,4. Recently, systemic therapies, such as the canine melanoma vaccine ONCEPT®5 and the anti-PD-1 antibody gilvetmab®, have been introduced. However, optimal protocols have not yet been established6.

The presence of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which infiltrate the tumor microenvironment, has been reported to correlate with poor prognosis in human cancers7. Consequently, TAM-targeted therapies have been extensively studied in the CCL2-CCR28, CSF-1-CSF-1R9, and CXCL8-CXCR1/2 axes10. Therapeutic strategies can be broadly categorized into limiting effector functions and recruitment, reprogramming, and preventing tumor-induced polarization. The inhibition of tumor-derived CCL2 effectively blocks macrophage recruitment and suppresses tumor cell metastasis8, which has led to the clinical investigation of CCL2-CCR2 inhibition therapy in human pancreatic cancer11.

CXCL8, also known as interleukin (IL)-8, is a member of the ELR+ CXC chemokine family and is expressed by numerous cells, including monocytes, lymphocytes, granulocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells12. CXCL8 recruits neutrophils13–15. CXCL8 exerts its effect by binding to CXCR1 and CXCR2, G-protein-coupled receptors with seven transmembrane domains16–18. CXCR1 binds to CXCL6 and CXCL8, whereas CXCR2 binds to multiple CXCLs19. These receptors are expressed in granulocytes, monocytes, and lymphocytes20. CXCL8 is expressed in various human cancer types21 and is associated with immune suppression, early recurrence, and poor prognosis22. CXCL8 overexpression in human cancer correlates with poor immunotherapy outcomes23. In human melanoma, CXCL8 production in tumor cells is associated with poor prognosis24,25. High CXCL8 expression has been reported in canine mammary tumors, hemangiosarcomas, and melanoma26–28. However, its association with prognosis and antitumor immunity remains unclear.

The mechanism by which macrophages interact with tumor cells in dogs remains poorly understood, and treatment options are limited. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the association between OMM and TAMs to elucidate the macrophage chemotactic factors released by canine melanoma cells.

Results

Canine OMM exhibited higher expression of macrophage-associated genes than the normal oral mucosa

The public RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) database (PRJNA527141) of dogs was reanalyzed to compare the expression of macrophage-associated genes between OMM tissues and normal oral mucosa. Figure 1a shows the expression of selected macrophage-associated genes (see Supplementary Table 1 online). Except for CXCL17 and CXCL12, the expression of macrophage-associated genes was significantly increased as compared to normal mucosa. Figure 1b highlights genes with significant differences (P < 0.001), particularly chemokines such as CCL2, CCL3, and CXCL8, which are known to be associated with macrophage migration. These transcriptomic findings suggest the potential involvement or infiltration of macrophages in canine OMM tissues.

Fig. 1.

Reanalysis of RNA-seq data to compare macrophage-associated gene expression between canine oral malignant melanoma (OMM) tissues and normal oral mucosa. a Heatmap showing the expression profiles (row Z-scores) of selected macrophage-associated genes in OMM tissues (n = 8) and normal oral mucosa (n = 3). b Volcano plot displaying differentially expressed genes between OMM tissues and normal mucosa. Selected macrophage-related genes are labeled. Statistical significance is based on adjusted p-values (FDR). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

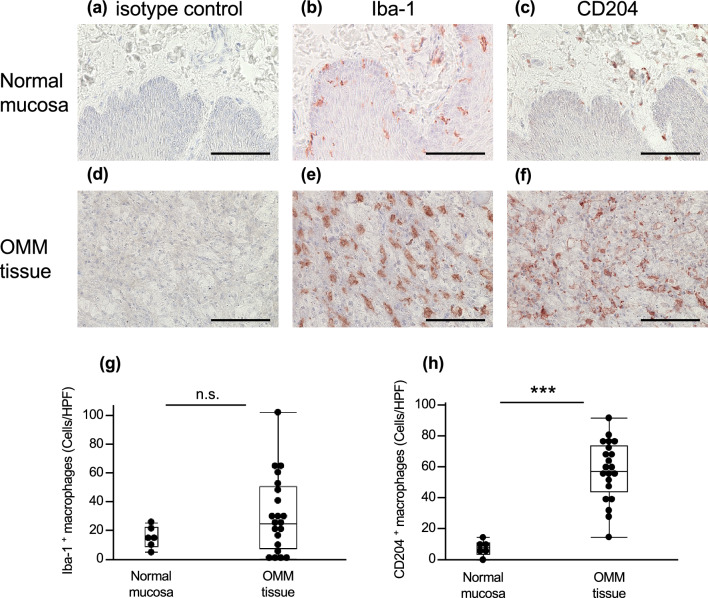

CD204-positive macrophages infiltrated the OMM tissue

Based on the results of the RNA-seq analysis, CD204-positive M2-type macrophage infiltration into OMM tissues and normal mucosa was investigated by immunohistochemistry (IHC). A few CD204-positive M2-type macrophages were observed in the normal oral mucosa, whereas relatively many Iba-1-positive pan-macrophages were observed (Fig. 2a–c). A large number of CD204-positive macrophages and Iba-1-positive macrophages were observed in OMM tissues (Fig. 2d–f). However, the number of Iba-1-positive macrophages varied among cases (Fig. 2g). The numbers of CD204-positive macrophages (Fig. 2h) and Iba-1-positive macrophages (Fig. 2g) were compared between the normal oral mucosa and OMM tissue. The number of CD204-positive macrophages was significantly higher in OMM tissues than in normal tissues. However, no significant difference was observed in the number of Iba-1-positive macrophages. The results showed that melanoma cells promoted the infiltration of CD204-positive macrophages into tumor tissues.

Fig. 2.

a–f Immunostaining of CD204 and Iba-1 positive macrophages in normal oral mucosa and OMM tissues. Bars = 100 µm. g, h Number of Iba-1 and CD204-positive macrophages in normal oral mucosa (n = 6) and OMM tissues (n = 21). ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant.

Each melanoma-conditioned medium (CM) migrated RAW264.7 cells

Chemotaxis assays were performed using culture supernatants from seven melanoma cell lines to evaluate the chemotactic factors released from melanoma cells. Figure 3 and supplementary figure S1 (online) show the number of RAW264.7 mouse macrophage cells migrated by each melanoma-CM. All CM, except for CMGD2, increased the number of migratory cells compared with the control media (Dunnett’s analysis, CMeC1 and CMM12: P < 0.001; KMeC, CMeC2, and CMM7: P < 0.01; CMM10: P < 0.05; CMGD2: not significant). Additionally, differences in the numbers of migratory cells were observed among each cell line.

Fig. 3.

Number of RAW264.7 cells migrated by each melanoma-conditioned medium (CM). Control is an RPMI-based complete medium. All data are presented as means ± SD of three independent experiments. Compared with the control group, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant.

The expression of macrophage-associated chemokines in canine melanoma cell lines correlated with the migration of RAW264.7 cells

The relative mRNA expression levels of CCL5, CX3CL1, CSF-1, IL-34, CXCL8, and CCL2, which are known chemotactic factors for macrophages, were investigated in seven canine melanoma cell lines (Fig. 4a–f). The correlation between mRNA expression levels and the number of migrated RAW264.7 cells was examined (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. S2). CXCL8 mRNA expression showed a weak positive trend with the number of migratory cells, but the correlation was not statistically significant (p = 0.062, Fig. 4g). The production of CXCL8 protein in the culture supernatants was then measured (Fig. 4h), and the correlation between the CXCL8 concentration and the number of migratory cells was assessed. A strong positive correlation was observed between CXCL8 concentration and migratory cells (Fig. 4i).

Fig. 4.

mRNA expression levels of chemokine in seven canine melanoma cell lines. a CCL5, b CX3CL1, c CSF-1, d IL-34, (e) CXCL8, and (f) CCL2. The relative expression level was normalized to the RPL32 gene. g Correlation between the number of migratory RAW264.7 and CXCL8 mRNA expression levels. h Production of CXCL8 in seven canine melanoma cell lines. i Correlation between the number of migratory RAW264.7 and CXCL8 secretion. All data are presented as means ± SD of three independent experiments.

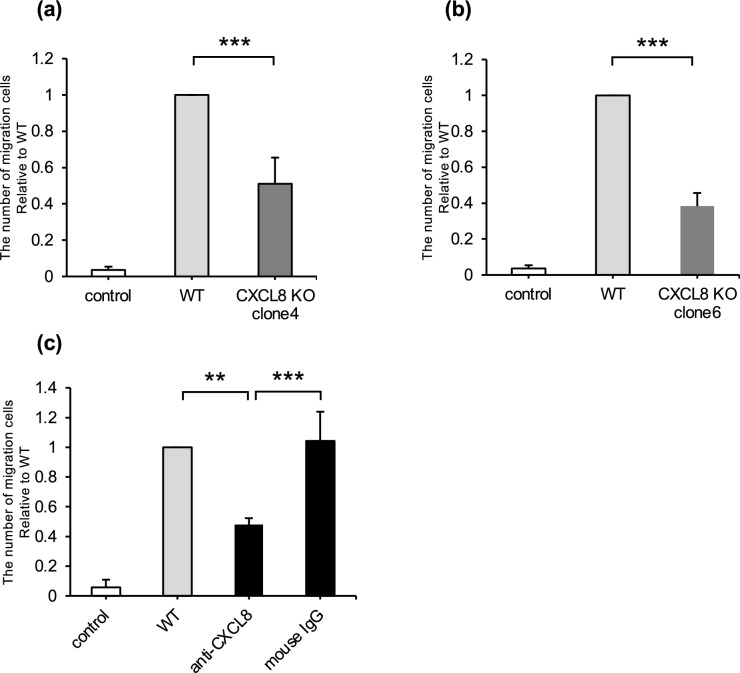

CXCL8 gene knockout or anti-dog CXCL8-neutralizing antibody reduced the number of migrated RAW264.7 cells

Two canine melanoma cell lines (CMeC1 and CMM12) that were knocked out of the CXCL8 gene using the CRISPR/Cas9 system were established to evaluate the effect of CXCL8 on the migration of RAW264.7 cells (see Supplementary Figs. S7 and S8 online). Compared with CM from CMeC1 wild-type (WT) cells, the number of migrated cells was significantly decreased in CM from CMeC1 CXCL8 knock out (CXCL8 KO) clones (Fig. 5a, b). Similarly, CM from CMM12/CXCL8-KO clones showed lower chemotaxis toward RAW264.7 cells than CM from CMM12 WT (see Supplementary Fig. S4 online). Furthermore, the migration of RAW264.7 cells induced by CM from CMeC1 was diminished when CM was pretreated with the anti-dog CXCL8-neutralizing antibody (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

a, b Relative number of RAW264.7 cells migrated by CMeC1 wild-type CM or CMeC1 CXCL8 knockout CM. c Relative number of RAW264.7 cells migrated by CMeC1 CM. The CM of CMeC1 wild-type cells were treated with anti-dog CXCL8 (1 μg/ml) or mouse IgG isotype (1 μg/ml). All data are presented as means ± SD of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

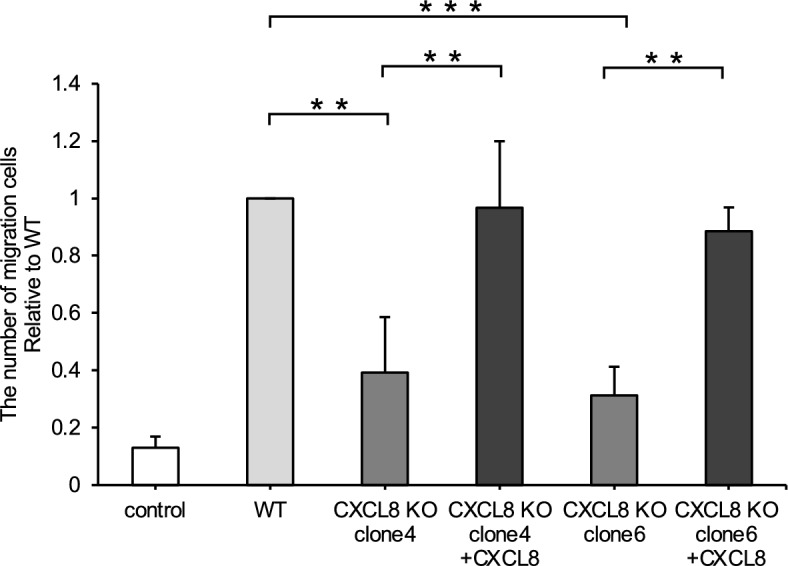

The addition of recombinant dog CXCL8 protein rescued the number of migrated cells in CMeC1/CXCL8 KO-CM

Whether the reduced migratory ability of RAW264.7 cells caused by CXCL8 deficiency could be rescued by exogenous recombinant dog CXCL8 protein was examined. The results showed that migratory cells were significantly restored when 200 ng/ml of recombinant canine CXCL8 protein was added to CM from CMeC1/CXCL8-KO (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Relative number of RAW264.7 cells migrated by CMeC1 CM. The CM of CMeC1 wild-type or CXCL8 knockout cells were treated with dog CXCL8 recombinant protein (200 ng/ml). All data are presented as means ± SD of three independent experiments. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

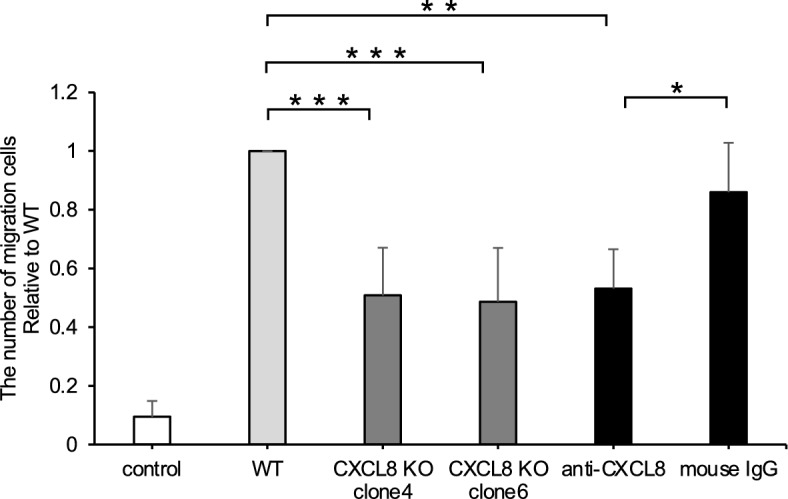

The number of migrated canine macrophage DH82 cells decreased by CXCL8 gene knockout or anti-dog CXCL8-neutralizing antibody

The influence of melanoma-CM and CXCL8 on the migratory ability of canine macrophage DH82 was investigated. Consistent with the assay using RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 3), CM from all melanoma cell lines, except CMGD2, induced a significant increase in the number of migrated DH82 cells (see Supplementary Fig. S3 online). However, unlike RAW264.7 cells, DH82 cell migration did not correlate with CXCL8 or other chemokine expressions. Nevertheless, as shown in Fig. 7, the number of migrated DH82 cells was significantly decreased by CM from CMeC1/CXCL8-KO clones compared with CM from CMeC1 WT. Additionally, the migration of DH82 cells induced by CMeC1 WT-CM was reduced when CM was pretreated with the anti-dog CXCL8-neutralizing antibody, consistent with the result of RAW264.7. These findings indicate that canine melanoma-secreted CXCL8 regulates both mouse and canine macrophage migration in vitro.

Fig. 7.

Relative number of canine macrophage DH82 cells migrated by CMeC1 CM. The CM of CMeC1 wild-type or CXCL8 knockout were treated with anti-dog CXCL8 (1 μg/ml) or mouse IgG isotype (1 μg/ml). All data are presented as means ± SD of four independent experiments. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Reanalysis of RNA-seq public data revealed high expression levels of macrophages and macrophage-related genes in canine OMM tissues, similar to human and mouse melanoma29,30. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that canine melanoma cells release chemotactic factors that promote TAM infiltration and analyzed macrophage markers in tumor tissues from dogs with OMM. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed increased CD204-positive macrophages in OMM compared with normal oral mucosa. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies31,32. However, contrary to previous findings31, no significant difference in Iba-1-positive macrophages was observed between OMM and normal oral mucosa in the present study. No difference was observed in the pan-macrophage marker Iba-1, and an increase in the M2 macrophage marker CD204 indicates a relative increase in M2 phenotype macrophages. In humans, TAMs are predominantly M2-polarized33,34, and the M2/M1 ratio is considered an independent prognostic factor, particularly in malignant melanoma35.

In dogs, the number of CD204-positive macrophages has been identified as a prognostic factor for mammary gland tumors36. However, in melanoma, CD204 expression has not been associated with poor prognosis31. In this study, the relationship between CD204 expression and prognosis could not be evaluated due to the small sample size and lack of long-term follow-up. Additionally, although CD204 is used as an M2 macrophage marker in veterinary medicine, its precise role remains unclear, and the biological significance of CD204-positive cells is not fully understood. A limitation of the present study is that only CD204 was evaluated as an M2 macrophage marker. Further studies are needed to analyze cases with comprehensive clinical data and incorporate multiple M2 markers, such as CD163 and CD206, for a more thorough evaluation.

RAW264.7 cells migrated in response to the CM from canine melanoma cell lines, indicating that macrophage chemotactic factors are released from canine melanoma. The correlation analysis between the mRNA levels in each melanoma cell line and the number of migrated cells indicated that CXCL8 was a potential chemotactic factor among the six chemokines assessed. Previous studies on human and mouse melanoma cells have shown that various cytokines, such as CCL5 and CSF-1, are secreted to promote macrophage migration37. However, no studies have investigated macrophage chemotactic factors released by canine melanoma cells. Furthermore, CXCL8 has traditionally been considered primarily associated with neutrophil chemotaxis rather than monocyte recruitment13. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify CXCL8 as a macrophage chemotactic factor in canine melanoma.

The results showed that the migration of RAW264.7 and DH82 cells was not completely inhibited by the addition of the anti-CXCL8 neutralizing antibody or CM from CXCL8 KO cells (Figs. 5, 6, 7). These findings suggest that other chemotactic factors may be present in the melanoma-CM. Although protein-level analyses of CCL238 and CX3CL139 were not conducted, these monocyte chemotactic factors showed no correlation between their mRNA expression levels and the number of migrated RAW264.7 cells, indicating that they are not the major chemotactic factors in the melanoma-CM. However, since these factors might still be present in the KO cell-CM or the CM after CXCL8-neutralizing antibody treatment, complete inhibition of monocyte migration was not achieved. The reduced macrophage migratory ability by CXCL8 KO could be restored by adding recombinant CXCL8 protein, although no chemotaxis was observed with recombinant CXCL8 protein alone (see Supplementary Fig. S5 online). CXCL8 plays a crucial role in priming the chemotaxis of macrophages and may contribute to macrophage migration in cooperation with other factors in the culture supernatant. CCL3 and CXCL12 have been reported to exhibit a synergistic effect on the chemotactic activity of CXCL8 in immature monocyte-derived dendritic cells40. Additionally, monocytes stimulated with IL-4/IL-13 exhibit CXCR1/CXCR2 upregulation, leading to enhanced CXCL8-induced migration41. Therefore, further studies are needed to investigate not only CXCL8 but also other chemotactic factors.

Notably, mice lack the homologous gene for CXCL8. However, mouse CXCR1 and CXCR2 (see Supplementary Fig. S6 online) were present and could bind exogenous canine CXCL8 protein in this study. Since dogs expressed endogenous CXCL8 and the CXCR1 (see Supplementary Fig. S6 online), similar results were likely obtained in mouse and canine macrophage cell lines. In the present study, we did not examine other chemokines; however, since previous studies have reported that canine tumor-derived proteins can induce phenotypic changes in murine macrophages42,43, the potential cross-reactivity of proteins other than CXCL8 between dogs and mice requires careful consideration in future investigations.

The inhibition of the CXCL8-CXCR1/2 axis is currently being developed as a potential treatment for inflammatory and tumor-related diseases in humans, with some already in clinical trials. Anti-CXCL8 antibodies, such as ABX-IL844,45 and HuMax-IL846, have been reported to inhibit tumor growth and metastasis. By identifying new treatment targets, we will develop antibody therapies not only for humans but also for dogs.

In conclusion, TAMs significantly infiltrated canine OMM tissues. Additionally, CXCL8 plays a crucial role as a key macrophage chemoattractant. A limitation of this study is the lack of experiments blocking CXCR1 and CXCR2, which will be necessary in future investigations to elucidate the function of CXCL8. Additionally, future studies should assess not only M2 markers but also M1 markers to gain a more comprehensive understanding of macrophage polarization in the tumor microenvironment. To clarify the clinical significance of TAMs and CXCL8 expression, it will also be essential to prospectively collect clinical cases with long-term follow-up and prognostic data.

Methods

Ethical approval statement

All owners of tumor-bearing dogs admitted to the Yamaguchi University Animal Medical Center provided comprehensive consent for the use of clinical information (including excised tumor tissues) for research and publication. All owners provided written informed consent for the use of each tissue specimen in the present study. All experiments were approved by the Yamaguchi University Animal Use Review Committee (Approval No. 579) and conducted in accordance with the Yamaguchi University Guidelines for Animal Care and Use and the ARRIVE guidelines.

Cell line validation and culture

The mouse macrophage cell line RAW264.7 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)-based complete medium, consisting of DMEM high glucose medium (Fujifilm Wako, Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 units/ml penicillin–streptomycin, and 55 µM 2-mercaptoethanol. The canine melanoma cell lines CMeC1, CMeC247, KMeC, CMM7, CMM10, and CMM1248 were provided by Dr. Takayuki Nakagawa (The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan) and cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640-based complete medium, consisting of RPMI-1640 medium (Fujifilm Wako) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin–streptomycin, and 55 µM 2-mercaptoethanol. The canine melanoma cell line CMGD249 was provided by Dr. Jaime F Modiano (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and cultured in an RPMI-1640-based complete medium. The canine macrophage cell line DH82 was purchased from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (EC94062922, London, UK) and cultured in a DMEM-based complete medium supplemented with 1 × MEM nonessential amino acids (Fujifilm Wako). All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. The absence of mycoplasma contamination in all cell lines was confirmed using the e-MycoTM Plus Mycoplasma PCR Detection Kit (iNtRON Bio, Burlington, MA, USA).

Generation of melanoma-CM from culture supernatants of canine melanoma cell lines

The canine melanoma cell lines were seeded at 5 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates in a 2.0 mL total volume of RPMI-based complete medium. After 24 h of incubation, culture supernatants were harvested and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected and stored at − 80 °C. The mouse anti-dog CXCL8-neutralizing monoclonal antibody (#258,911, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and mouse IgG1 isotype control (MG1-45, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) were added at a concentration of 1 µg/mL into the canine melanoma-CM. The recombinant canine CXCL8 protein (NBP2-34,908, Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, USA) was supplemented at a final concentration of 200 ng/mL into the CM.

Gene knockout using the CRISPR/Cas9 system

The CRISPR/Cas9-based knockout system generated CXCL8 KO cells. A small guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting canine CXCL8, 5′-CAAGCTGGCTGTTGCTCTCT-3′, was designed using the E-CRISP online software (http://www.e-crisp.org/E-CRISP/). The designed sgRNA was synthesized and cloned into lentiCRISPRv2 plasmid#52,961 (Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA) as described previously50. The plasmid and packaging vectors were then transfected into HEK293T cells (RIKEN Bioresource Research Center, Ibaraki, Japan, Cat#RCB2202) to produce lentivirus expressing the sgRNA, particularly targeting the CXCL8 gene. After transduction with lentivirus, CMeC1 and CMM12 cells were cultured in puromycin (2.5 μg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich, Tokyo, Japan) to obtain CXCL8 knockout cells. Individual clones were isolated using the limiting dilution method and further validated using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to confirm the absence of CXCL8 production (see Supplementary Fig. S7 online).

RNA-seq analysis

Previously published RNA-seq data (PRJNA527141) from 8 canine OMM tissues and 3 normal oral mucosal tissues were reanalyzed to compare the expression of macrophage-associated genes. RNA-seq analysis was performed. The data FASTQ-formatted RNA-seq reads were preprocessed using Trimmomatic (ver. 0.39)51 and aligned to Ensembl-derived canine cDNAs (release-109) using Salmon (ver. 1.3.0) software52. Statistical analysis was performed using the DESeq2 software (ver. 1.44.0)53. The criteria for identifying upregulated and downregulated genes were based on a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 between OMM and oral mucosa, with upregulated genes defined as those with a fold change > 2 and downregulated genes defined as those with a fold change < –2. The data were visualized using the R software (ver. 4.0.3) (https://www.R-project.org/)with the R package ggplot2 (ver. 3.3.5) (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org.).

Immunohistochemistry

Our laboratory’s tissue archives sourced 6 normal oral mucosal tissues from healthy dogs and 21 OMM tissues. For specific details, please refer to Supplementary Tables S2 online. 4 μm thick sections were cut from archival paraffin-embedded tissues and placed on coated glass slides (MAS-GP type A; Matsunami, Osaka, Japan). The sections were deparaffinized in xylene and hydrated in graded ethanol. The sections were incubated with 10% H2O2 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min at 65 °C for melanin bleaching. Antigen retrieval was performed by autoclaving in Tris–EDTA (pH 9.0) buffer for CD204 and 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for Iba-1 for 20 min at 121 °C. The sections were treated with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min at room temperature and rinsed with PBS to block endogenous peroxidase activity. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with 5% bovine serum albumin mixed with 5% skimmed milk in PBS for 30 min at room temperature to prevent nonspecific antibody binding. The slides were incubated with primary antibodies against mouse anti-human CD204 monoclonal antibody (SRA-E5, Cosmo Bio Co., LTD, Tokyo, Japan) (1:1000 dilution)54 and rabbit anti-rat Iba-1 polyclonal antibody (Wako, Osaka, Japan) (1:2000 dilution)55 overnight at 4 °C. Rabbit IgG isotype control (DA1E, Cell Signaling Technology, Massachusetts, MA, USA) and mouse IgG1 isotype control (P3.6.2.8.1, eBioscience, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) were negative controls. After three washes in PBS for 5 min each, the sections were incubated with Histofine Simple Stain MAX PO (Nichirei Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) for 30 min as the secondary antibody at room temperature. Red color development was labeled with Histofine Simple Stain AEC (Nichirei Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), followed by counterstaining with Mayer’s hematoxylin. For each antibody, positive cells were manually counted in 10 randomly selected fields under high-power magnification (× 400 HPF) for each sample.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA from each canine melanoma cell line was isolated using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using a ReverTra Ace qPCR RT kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). Real-time PCR was performed using a QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) according to a previous report56. Detection was performed using a CFX Touch Real-Time PCR system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S3 online. The amplification of each gene was evaluated using the melting curves of the PCR products.

Transwell migration assay

Cell migration was assayed in 24-well cell culture plates using Transwell inserts with 5 μm pore membranes (#CH3-24 KURABO, Okayama, Japan) for RAW264.7 cells and 8 μm pore membranes (#PTEP24H48, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for DH82 cells. Then, 4 × 105 RAW264.7 cells were suspended in 200 µL of FBS-free DMEM and transferred to the upper chamber of the Transwell, whereas 600 μL of each melanoma-CM was added to the lower chamber. Similarly, 2 × 105 DH82 cells suspended in 200 µL of FBS-free DMEM were added to the upper Transwell chamber, whereas 750 µL of each melanoma-CM was added to the lower chamber. A culture medium containing 10% FBS was used as a control in the lower chamber. The Transwell chamber was incubated at 37 °C for 4 h and washed twice with PBS. Cells that did not pass through the upper chamber were carefully wiped off with a cotton swab, fixed, and stained with Hemacolor (#1.11661, Merck). The stained cells were counted in 10 randomly selected fields under high-power magnification (× 400 HPF) for each sample and analyzed using a BZ-X800 (KEYENCE, Osaka, Japan).

ELISA

The culture supernatants from each cell line were collected. CXCL8 was detected using the Canine IL-8/CXCL8 DuoSet ELISA kit (#DY1608, R&D Systems) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Western blotting analysis

Recombinant canine (NBP2-34908, Novus Biologicals) (same as the recombinant protein used in transwell migration assay), recombinant human CXCL8 protein (HZ-1318, Proteintech Group, Inc., Rosemont), or proten ectracted from CMeC1 underwent electrophoresis in 15% acrylamide gel. The proteins were subsequently blotted onto a PVDF membrane (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and then blocked using a blocking buffer (Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 and 5% skimmed milk) for a duration of 1 h at room temperature (RT). The membrane was left to incubate overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti-canine CXCL8 monoclonal antibody (#258911, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) (same as the antibody used in transwell migration assay) or mouse anti-beta actin monoclonal antibody (AC-74, Sigma-Aldrich) in TBS-T with 5% BSA. Following this, the membrane underwent incubation with horseradish peroxidase HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (BioLegend, San Diego, USA) for 1 h at RT. Finally, specific proteins were visualized using an ECL reagent (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and detected with AMERSHAM Image Quant 800 (Global Life Sciences Technologies Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The results were shown in Supplementary Fig. S8.

Statistical analysis

Mean values and standard deviations (SD) were calculated based on at least three independent biological experiments. The significance of differences between samples was assessed using one-way factorial ANOVA followed by multiple comparisons using Tukey–Kramer tests. P-values < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro software ver. 16.1.0 (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the dogs and their owners for making this study possible. We wish to thank all Yamaguchi University Animal Medical Center’s clinical staff and Dr. Kenji Hagimori (Kamogawa Animal Medical Center, Kyoto, Japan) for helping us succeed in the present study.

Author contributions

M.I. designed the present study. N.O. and M.I. performed all experiments. RNA-seq analysis and immunohistochemistry (partial) were performed by S.S. and H.Y., respectively. N.O. and M.I. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. M.S., K.B. and T.M. contributed to the interpretation of the results. K.I., D.K., T.N., and S.M. provided the experiment resources. M.I. supervised the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science) KAKENHI Grant Number 22K14991 and The UBE Foundation 64th Research Grant Award.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Other researchers have deposited sequence data supporting this study’s findings in the Sequence Read Archive of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with the primary accession code PRJNA527141.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gillard, M. et al. Naturally occurring melanomas in dogs as models for non-UV pathways of human melanomas. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res.27, 90–102 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishiya, A. T. et al. Comparative aspects of canine melanoma. Vet. Sci.3, 7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boston, S. E. et al. Efficacy of systemic adjuvant therapies administered to dogs after excision of oral malignant melanomas: 151 cases (2001–2012). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc.245, 401–407 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy, S. et al. Oral malignant melanoma - the effect of coarse fractionation radiotherapy alone or with adjuvant carboplatin therapy. Vet. Comp. Oncol.3, 222–229 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grosenbaugh, D. A. et al. Safety and efficacy of a xenogeneic DNA vaccine encoding for human tyrosinase as adjunctive treatment for oral malignant melanoma in dogs following surgical excision of the primary tumor. Am J Vet Res.72, 1631–1638 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polton, G. et al. Melanoma of the dog and cat: consensus and guidelines. Front Vet Sci.11, 1359426 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruffell, B., Affara, N. I. & Coussens, L. M. Differential macrophage programming in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol.33, 119–126 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qian, B. Z. et al. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature475, 222–225 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai, H., Zhang, Y., Wang, J. & Gu, J. Defects in Macrophage Reprogramming in Cancer Therapy: The Negative Impact of PD-L1/PD-1. Front Immunol.12, 690869 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han, Z. J. et al. Roles of the CXCL8-CXCR1/2 axis in the tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy. Molecules27, 137 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nywening, T. M. et al. Targeting tumour-associated macrophages with CCR2 inhibition in combination with FOLFIRINOX in patients with borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a single-centre, open-label, dose-finding, non-randomised, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol.17, 651–662 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zlotnik, A., Morales, J. & Hedrick, J. A. Recent advances in chemokines and chemokine receptors. Crit. Rev. Immunol.19, 1–47 (1999). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baggiolini, M., Loetscher, P. & Moser, B. Interleukin-8 and the chemokine family. Int. J. Immunopharmacol.17, 103–108 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baggiolini, M., Walz, A. & Kunkel, S. L. Neutrophil-activating peptide-1/interleukin 8, a novel cytokine that activates neutrophils. J. Clin. Invest.84, 1045–1049 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stillie, R., Farooq, S. M., Gordon, J. R. & Stadnyk, A. W. The functional significance behind expressing two IL-8 receptor types on PMN. J. Leukoc. Biol.86, 529–543 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes, W. E., Lee, J., Kuang, W. J., Rice, G. C. & Wood, W. I. Structure and functional expression of a human interleukin-8 receptor. Science253, 1278–1280 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy, P. M. & Tiffany, H. L. Cloning of complementary DNA encoding a functional human interleukin-8 receptor. Science253, 1280–1283 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park, S. H. et al. Structure of the chemokine receptor CXCR1 in phospholipid bilayers. Nature491, 779–783 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuo, Y. et al. CXC-chemokine/CXCR2 biological axis promotes angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo in pancreatic cancer. Int. J. Cancer.125, 1027–1037 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chuntharapai, A., Lee, J., Hébert, C. A. & Kim, K. J. Monoclonal antibodies detect different distribution patterns of IL-8 receptor A and IL-8 receptor B on human peripheral blood leukocytes. J. Immunol.153, 5682–5688 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie, K. Interleukin-8 and human cancer biology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev.12, 375–391 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, Q. et al. The CXCL8-CXCR1/2 pathways in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev.31, 61–71 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuen, K. C. et al. High systemic and tumor-associated IL-8 correlates with reduced clinical benefit of PD-L1 blockade. Nat. Med.26, 693–698 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hensley, C. et al. In vivo human melanoma cytokine production: inverse correlation of GM-CSF production with tumor depth. Exp. Dermatol.7, 335–341 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nürnberg, W., Tobias, D., Otto, F., Henz, B. M. & Schadendorf, D. Expression of interleukin-8 detected by in situ hybridization correlates with worse prognosis in primary cutaneous melanoma. J. Pathol.189, 546–551 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim, J. H. et al. Interleukin-8 promotes canine hemangiosarcoma growth by regulating the tumor microenvironment. Exp. Cell. Res.323, 155–164 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren, X., Fan, Y., Shi, D. & Liu, Y. Expression and significance of IL-6 and IL-8 in canine mammary gland tumors. Sci Rep.13, 1302 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rahman, M. M. et al. Transcriptome analysis of dog oral melanoma and its oncogenic analogy with human melanoma. Oncol. Rep.43, 16–30 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, J. et al. Single-cell characterization of the cellular landscape of acral melanoma identifies novel targets for immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res.28, 2131–2146 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davidson, S. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals a dynamic stromal niche that supports tumor growth. Cell Rep.31, 107628 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yokota, S., Kaji, K., Yonezawa, T., Momoi, Y. & Maeda, S. CD204⁺ tumor-associated macrophages are associated with clinical outcome in canine pulmonary adenocarcinoma and transitional cell carcinoma. Vet J.296–297, 105992 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porcellato, I. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages in canine oral and cutaneous melanomas and melanocytomas: phenotypic and prognostic assessment. Front Vet Sci.9, 878949 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Locati, M., Curtale, G. & Mantovani, A. Diversity, mechanisms, and significance of macrophage plasticity. Annu Rev Pathol.15, 123–147 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noy, R. & Pollard, J. W. Tumor-associated macrophages: from mechanisms to therapy. Immunity41, 49–61 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.López-Janeiro, Á., Padilla-Ansala, C., de Andrea, C. E., Hardisson, D. & Melero, I. Prognostic value of macrophage polarization markers in epithelial neoplasms and melanoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mod. Pathol.33, 1458–1465 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seung, B. J. et al. CD204-expressing tumor-associated macrophages are associated with malignant, high-grade, and hormone receptor-negative canine mammary gland tumors. Vet. Pathol.55, 417–424 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reschke, R., Enk, A. H. & Hassel, J. C. Chemokines and cytokines in immunotherapy of melanoma and other tumors: from biomarkers to therapeutic targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci.25, 6532 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsou, C. L. et al. Critical roles for CCR2 and MCP-3 in monocyte mobilization from bone marrow and recruitment to inflammatory sites. J. Clin. Invest.117, 902–909 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Auffray, C. et al. CX3CR1+ CD115+ CD135+ common macrophage/DC precursors and the role of CX3CR1 in their response to inflammation. J. Exp. Med.206, 595–606 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gouwy, M. et al. Chemokines and other GPCR ligands synergize in receptor-mediated migration of monocyte-derived immature and mature dendritic cells. Immunobiology219, 218–229 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonecchi, R. et al. Induction of functional IL-8 receptors by IL-4 and IL-13 in human monocytes. J. Immunol.164, 3862–3869 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eto, S. et al. The impact of damage-associated molecules released from canine tumor cells on gene expression in macrophages. Sci. Rep.11, 8525 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beirão, B. C., Raposo, T., Pang, L. Y. & Argyle, D. J. Canine mammary cancer cells direct macrophages toward an intermediate activation state between M1/M2. BMC Vet. Res.11, 151 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mian, B. M. et al. Fully human anti-interleukin 8 antibody inhibits tumor growth in orthotopic bladder cancer xenografts via down-regulation of matrix metalloproteases and nuclear factor-kappaB. Clin. Cancer Res.9, 3167–3175 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang, S. et al. Fully humanized neutralizing antibodies to interleukin-8 (ABX-IL8) inhibit angiogenesis, tumor growth, and metastasis of human melanoma. Am. J. Pathol.161, 125–134 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bilusic, M. et al. Phase I trial of HuMax-IL8 (BMS-986253), an anti-IL-8 monoclonal antibody, in patients with metastatic or unresectable solid tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer.7, 240 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inoue, K. et al. Establishment and characterization of four canine melanoma cell lines. J. Vet. Med. Sci.66, 1437–1440 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshitake, R. et al. Molecular investigation of the direct anti-tumour effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in a panel of canine cancer cell lines. Vet. J.221, 38–47 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bianco, S. R. et al. Enhancing antimelanoma immune responses through apoptosis. Cancer Gene Ther.10, 726–736 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Igase, M. et al. Combination therapy with reovirus and ATM inhibitor enhances cell death and virus replication in canine melanoma. Mol Ther Oncolytics.15, 49–59 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics30, 2114–2120 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patro, R., Duggal, G., Love, M. I., Irizarry, R. A. & Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods.14, 417–419 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol.15, 550 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kato, Y. et al. The class A macrophage scavenger receptor CD204 is a useful immunohistochemical marker of canine histiocytic sarcoma. J. Comp. Pathol.148, 188–196 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nemoto, Y. et al. Histiocytic sarcoma with spinal necrosis in a dog with progressing non-ambulatory tetraparesis. Open Vet. J.13, 394–399 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Igase, M. et al. The effect of 5-aminolevulinic acid on canine peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol.251, 110473 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Other researchers have deposited sequence data supporting this study’s findings in the Sequence Read Archive of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with the primary accession code PRJNA527141.