Abstract

This study focuses on the chimeric peptide KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR and its interaction with cancer cells, specifically HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa and Ca Ski cells. The main objective of this study was to understand the mode of action of this chimera related to its cytotoxic activity, as well as the internalization processes and the type of cell death induced. For this purpose, several in vitro and in vivo assays were performed, showing that the uptake of the chimera is not energy-dependent and could involve a passive transport process. The results suggested that chimera internalization can be mediated by a specific interaction of the peptide with molecules on the cell membrane. The cytotoxic effect of the chimera in cervical cancer cells causes severe morphological changes, including rounding, shrinking, and vacuole formation. It was also determined that the chimera primarily induces early and late apoptosis in HeLa cells, without causing necrosis, and activates caspases 3 and 7. The chimera was localized in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus of the cancer cells, suggesting that the peptide could interact with intracellular targets. In conclusion, this study provides a broader understanding of the mechanism of action of the KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR chimera on cancer cells, highlighting its ability to induce a fast, selective, and significantly cytotoxic effect in cervical cancer cells, which involves cell death through the apoptotic pathway. The toxicity assays in Galleria mellonella and zebra fish showed that the chimera is safe and can be considered for preclinical studies. This study demonstrated that the chemical binding of two sequences with low activity produces a chimeric entity with enhanced cytotoxic activity capable of cellular internalization and inducement of apoptosis.

Introduction

Cervical cancer caused approximately 340,000 deaths in 2022, especially in developing countries. This high mortality rate is largely due to the lack of access to early detection, vaccination programs, and adequate treatment. Despite advances in prevention, such as human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and Pap smears, and in treatment, which includes surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, cervical cancer remains a significant challenge due to its resistance to conventional therapies. In this context, research into new therapeutic strategies is crucial for improving clinical outcomes and patients’ quality of life.

Peptide chimeras have emerged as a promising class of therapeutic agents in the fight against cancer. These molecules, designed by combining different peptide sequences with specific properties, can selectively target cancer cells and trigger cell death mechanisms. Chimeric peptides containing a palindromic sequence derived from lactoferricin B (LfcinB) RWQWRWQWR bound to RRWQWR (sequence derived from LfcinB), RLLR (a sequence derived from buforin), or RKKRRQRRR (a cell-penetrating peptide) have shown remarkable cytotoxic activity against cervical cancer cells, such as HeLa and Ca Ski cell lines. The KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR chimera (referred to here as CH-1) has exhibited antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27893, and Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 strains. , Additionally, it exhibited antifungal activity against reference strains and clinical isolates of Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans. , Furthermore, this chimeric peptide has shown a significant, selective cytotoxic effect against breast cancer cells MCF-7 (IC50 = 40 μM) and cervical cancer cells HeLa (IC50 = 66 μM).

This CH-1 chimaera is a combination of the sequence KKWQWK, which is derived from the minimal activity motif (RRWQWR) of LfcinB and the sequence RLLRRLLR, which twice contains the RLLR motif, which is present in buforin I, buforin II and buforin IIb peptides. , The chimera design was based on combining short sequences belonging to antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) with different mechanisms of action. LfcinB acts mainly on the cell membrane, causing its disruption and/or internalizing itself to act on intracellular targets, , while buforin II and buforin IIb has exhibited cytotoxic activity against leukemia, lung, kidney, prostate, melanoma, breast, and colon cancer cell lines. These peptides are internalized by the cell without affecting the cell membrane and interact with DNA and mitochondria, causing apoptosis. ,

Studies of peptide-cell interactions, specifically in HeLa and Ca Ski cells involving the CH-1 chimera, are crucial for understanding its therapeutic potential against HPV18-positive cervical cancer. In the present study, it was established that the CH-1 is internalized and localized in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus of HeLa cells. The cytotoxic effect induced severe morphological changes, the activation of caspases 3 and 7, and apoptosis. The results obtained provide a comprehensive view of the therapeutic potential of this chimera and contribute to the development of new strategies for the treatment of cervical cancer.

Methods

Peptide Synthesis

The scaling up of the synthesis of CH-1 chimera (KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR) was carried out using the manual solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) Fmoc/tBu strategy. Briefly, 200 mg (lot 1) or 700 mg (lot 2) of Rink amide resin were swollen by treatment with a mixture of N,N dimethylformamide (DMF)/dichloromethane (DCM) (1:1 v/v) under agitation for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Fmoc-group removal was carried out by treating the resin or peptide-resin with 2.5% 4-methylpiperidine in DMF for 15 min with constant shaking at RT (twice). Then the reaction mixture was washed with DMF (3 × 1 min) and DCM (3 × 1 min). The Fmoc–amino acid (0.2 mol) was mixed with dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) (0.2 mol), 6-chloro-2-hydroxybenzotriazol (6-Cl-HOBt) (0.21 mmol) in a mixture DMF/DCM (2:1 v/v) containing two drops of Triton X-100. Then the reaction mixture was shaken for 12 h at RT. The removal of the Fmoc group and the complete incorporation of the amino acids were confirmed using the Kaiser test. The cleavage of the peptide from the resin and deprotection of the amino acid side chains were achieved by treating the dried peptide-resin with a solution containing TFA/water/triisopropylsilane (TIPS)/ethanedithiol (EDT) (92.5:2.5:2.5:2.5; v/v) for 8 h with constant shaking at RT. The peptides were precipitated and washed with cold ethyl ether and then dried at RT.

The synthesis of RhB-CH-1 (RhB-KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR) proceeded in a manner like that described above, and the coupling reaction was carried out by dissolving rhodamine B (0.2 mol), and TBTU (0.2 mol) in DMF; then, N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) (0.8 mol) was added to the resin-peptide and the reaction mixture was stirred for 1 h at RT.

RP-HPLC Peptide Analysis

The peptide (10 μL; 0.5 mg/mL) was analyzed in an Agilent 1260 HPLC (Omaha, NE, USA) chromatograph equipped with a UV–vis (210 nm) detector using a monolithic (Chromolith RP-18, (50 × 4.6 mm)) column. The gradient elution was 5:5:50:100:100:5:5% B at 0:1:9:9.1:12:12.1:15 min, utilizing a flow rate of 2 mL/min. Solvent A: H2O with 0.05% TFA; solvent B: ACN with 0.05% TFA.

Peptide Purification

The peptide (150 mg/mL) was dissolved in a mixture of solvent A/solvent B (1:0.1 v/v) and purified by means of solid phase extraction (RP-SPE using a SPE column (Supelco ENVI-18, 5.0 g)). The peptide was eluted using a growing gradient of Solvent B. The fractions were analyzed using RP-HPLC, and those containing pure peptide were mixed and lyophilized and stored at 4 °C in a dry environment.

LC–MS Peptide Analysis

Two μL of pure peptide (0.05 mg/mL) was analyzed in a Bruker Impact II LC Q-TOF spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionizer (ESI) in positive mode. The chromatographic parameters were intensity solo C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm) (Bruker Daltonik), 40 °C, flow rate 0.25 mL/min. Solvent A: H2O with 0.1% formic acid, and solvent B: ACN with 0.1% formic acid. The MS conditions were end plate offset: 500 V; capillary: 4500 V; nebulizer: 1.8 bar; dry gas flow: 8.0 L/min; dry temperature: 220 °C; ion energy: 5.0 eV; acquisition mode: auto MS/MS; polarity: positive mode; mass range: 20–1000 m/z.

FT-IR Analysis

The peptide/KBr mixture (0.5:300 w/w) was triturated until the particle size was reduced and a homogeneous solid was obtained, and then the mixture was manually compressed to a thin, transparent pellet. The pellet was analyzed in an IR Affinity-1 (Shimadzu) spectrometer with the follow parameters: range 450–4000 cm–1, 64 scans, and resolution 8.0.

Circular Dichroism Analysis

The pure peptide (0.3 mg/mL) was dissolved in either water or water containing 30% trifluoroethanol (TFE), and analyzed using a Jasco-815 spectropolarimeter with a 10 mm path length cell, measuring in the range of 190–250 nm at 20 °C.

NMR Peptide Analysis

The peptides dissolved in D2O (10 mg/700 μL) were analyzed in an NMR Bruker Avance spectrometer operating at a proton frequency of 400.13 Hz at 23 °C. 1H NMR spectra were acquired with a width of 20 ppm, 64 scans, and a 2.0 s relaxation period. The peptides were also analyzed via two-dimensional 1H–1H COSY, 1H–1H TOCSY, and 1H–1H NOESY experiments.

MTT Viability Test

HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa (ATCC CRM-CCL-2) and Ca Ski cells (ATCC CRL-1550) (10,000) at 70–90% confluency were subcultured in 96-well plates in supplemented medium (DMEM 10% SFB) at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. After adherence, the medium was replaced with nonsupplemented medium and incubated for 12 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Afterward, the culture medium was removed, and 100 μL of peptide dissolved in medium at concentrations of 6.25 to 200 mg/mL was added. The cells were incubated for 2 or 24 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Then 10 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Subsequently, 100 μL of DMSO was added and the absorbance at 590 nm was recorded in a microplate reader. Negative control: cells untreated, and positive control: cells treated with H2O2.

Evaluation of the Endocytic Pathway

For the endocytosis assays (temperature, inhibitors, and ATP depletion), the MTT assays were carried out in a manner like that described above, with some changes: i. Temperature: HeLa and Ca Ski cells were incubated for 30 min at 4 °C and then treated with the CH-1 chimera for 2 h at 4 °C. ii. Cytotoxic effect in ATP-depleted cancer cells: the cancer cells were previously treated with 70 μL of sodium azide (1 mg/mL) for 1 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere, and subsequently the cells were washed with PBS and the treatment was added. iii. Evaluation of the cytotoxic effect in cells pretreated with endocytosis inhibitors: the cancer cells were previously treated with 70 μL of each endocytosis inhibitor (50 μg/mL nystatin or 10 μg/mL chlorpromazine) for 1 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere, and subsequently the cells were washed with PBS and the treatment was added. ,

Cytometry Assay

HeLa cells were cultured with 1 × 106 cells/well in 24-well plates in supplemented medium (DMEM 10% SFB) at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. After adherence and synchronization, the medium was removed, and 200 μL of supplemented medium and 200 μL of the chimera (final concentration IC50 = 16 μM (33 μg/mL)) were added and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. The cells were then washed with PBS, treated with trypsin–EDTA, and centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min. They were then resuspended in 100 μL of Muse Annexin V & Dead Cell staining buffer (1X Annexin V binding buffer, 0.5 μL of 7-AAD and 0.5 μL of FITC-Annexin V) and incubated in the dark at RT for 15 min. Then the cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 200 μL of PBS 1 mM EDTA and analyzed via flow cytometry in the Guava Muse cell analyzer. Positive apoptosis control: cells treated with 25% formaldehyde and palindromic peptide RWQWRWQWR; negative control: untreated cells.

Detection of Caspase 3 and 7 Activity Using Luminometry

The HeLa cells were cultured with 1 × 106 cells/well in 24-well plates in supplemented medium (DMEM 10% SFB) at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. After adherence and synchronization, the cells were treated with the chimera at concentrations of 25, 45, or 100 μg/mL for 2 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Afterward, they were washed with PBS, trypsinized to detach them, and centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was then reconstituted with supplemented medium (8000 cells/10 μL). Then, in a white opaque 96-well plate, 10 μL of cell suspension and 40 μL of 1X Caspase-Glo reagent were added in triplicate and incubated for 10 min in the dark at RT, and the luminescence was read in the Thermo Scientific Luminoskan microplate reader. The reagent without cells was used as a blank, and cells without reagent as a negative control.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were cultured on sterile circular slides arranged in a 24-well plate. After adherence, they were treated with the rhodaminated peptide at the IC50 (6 μM) for 2 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Subsequently, they were washed with PBS. The cells were then fixed by treatment with 2% paraformaldehyde with 1% sucrose in 100 mM PBS for 30 min and then washed with PBS. Permeabilization solution (0.1% Triton X-10020 mM Glycine100 mM PBS) was then added for 10 min and washed with PBS. The cells were then treated with blocking solution (1% bovine serum albumin20 mM Glycine100 mM PBS) for 10 min, followed by the addition of SMAC antibody, and then left to incubate for 90 min protected from light. Following this, the cells were washed with PBS. Twenty-five μL of Hoechst 33342 nuclear staining solution (1/50 dilution in 10 mM PBS) was then added and they were incubated for 7 min. They were then washed with PBS. For mounting, 5 μL of Fluoromount fluorescence mounting medium was added to a slide, and the coverslip was placed on top of this with the cells facing down. The cells were left to dry in the dark and subsequently observed with a Leica DMi8 confocal fluorescence microscope in immersion oil, and photographic records were taken.

Contrast Microscopy

Photographic recording was performed via phase-contrast microscopy of the cells treated with the chimera using a Motic microscope at 20 °C for 1 h.

In the membrane integrity assay, cells seeded and adhered to a 24-well plate were treated with the chimera at IC50 for 2 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 atmosphere, then washed with PBS, and 0.4% trypan blue was added. The cells were observed using a Motic phase-contrast microscope, and photographic records were taken.

Toxicity in Galleria mellonella

Larvae obtained from Perkins Biological Products LTDA (Palmira, Valle del Cauca, Colombia), weighing 200 to 300 mg, were rinsed with sterile water. They were subsequently inoculated into the last proleg with 10 μL of saline solution or the chimera and maintained in Petri dishes (n = 10, per group) in the dark at 37 °C. Larval survival was monitored every 24 h for 10 days. Using Kaplan–Meier curves, the viability data were analyzed.

Toxicity in Zebrafish (Danio rerio)

One hundred and fifty wild-type AB zebrafish embryos were fed and raised in an egg-water medium at pH 7.5 and 28 °C until day 3 postfertilization (3 dpf). Following a randomized block design, the embryos were placed in groups of 10 organisms in sterile 6-well culture plates. They were subsequently treated with the peptide at concentrations of 0.5, 10, 20, and 40 μg/mL in the growth medium for 96 h, with water exchange every 24 h. Experiments were performed in triplicate, using the egg-water embryo growth medium as a negative control and 3% dichloroaniline (DCA) in egg-water as a positive control. The survival data were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier curves.

Statistical Analysis

The data were processed and graphed using GraphPad Prism 8 analysis software.

Results

In this study, several assays were performed using the CH-1 (KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR) to approximate the type of interaction occurring between the peptide and the HPV18-positive cervical cancer cells and to gain insight into the mechanism by which the molecule acts.

Two batches of the CH-1 chimera were obtained with SPPS-Fmoc/tBu with chromatographic purity of 88% (batch 1) and 91% (batch 2), and the experimental molecular mass of the products corresponded to that expected (Figures S1 and S2, Supporting Information). The chromatographic profiles of the CH-1 batches showed the same retention time and similar purity (Figures S1 and S2, Supporting Information). The assays of this research were carried out with batch 2.

Likewise, the FT-IR and NMR spectra were identical for the peptides obtained in the two batches. In the FT-IR spectrum of CH-1, characteristic bands (1655, 1543, and 1203 cm–1) associated with peptide structure were observed (Figure S3, Supporting Information). Among them, the amide I band stands out, which corresponds to the stretching vibration of the peptide bond CO and appears in the range of 1600 to 1700 cm–1. The amide II band, located between 1480 and 1575 cm–1, is primarily attributable to C–N stretching and N–H bending vibrations. Additionally, a band is observed in the range of 1229 to 1301 cm–1, corresponding to the amide III band, although with lower intensity. This band is partially obscured by the presence of a band at 1203 cm–1, which corresponds to the C–F stretching vibration of the trifluoroacetate ion, present as the counterion of the peptide. The amide I band is particularly useful for inferring the peptide’s secondary structure. In this case, the minimum transmittance was observed at 1655 cm–1, suggesting the possible presence of α-helix-type structures, as this conformation typically presents an amide I band in the 1650–1660 cm–1 range. Analysis of the CH-1 reveals a high proportion of leucine residues, an amino acid known to promote α-helix formation (Figure S4, Supporting Information).

Through spectral deconvolution and mathematical analysis of the amide I band, it would be possible to estimate the relative content of secondary structures in the peptide’s conformation. After converting the FT-IR spectrum to absorbance values and performing deconvolution of the Amide I band for CH-1 using Origin 2024 software, the signal was found to consist of three peaks centered at 1649, 1653, and 1679 cm–1, as shown in the figure (Figure S4, Supporting Information). The corresponding peak area percentages were 76%, 4%, and 20%, respectively. Based on the wavenumber positions of these peaks and literature reports, the secondary structure of this peptide appears to be predominantly α-helical. Peaks 1 and 2 (1649 and 1653 cm–1, respectively), which together account for 80% of the total area, fall within the range typically associated with α-helices and glutamine side chains (1650–1659 cm–1), consistent with the presence of a Gln residue in the sequence. The remaining 20% of the area corresponds to peak 3 (1679 cm–1), located in a region characteristic of β-turn structures, suggesting that this conformation may be present to a lesser extent.

The FT-IR spectra of CH-1, RhB-CH-1, and Rhodamine B were compared to assess structural differences. The spectrum of Rhodamine B displayed characteristic peaks consistent with those reported in the literature. In contrast, the spectra of CH-1 and RhB-CH-1 were nearly identical and distinctly different from that of Rhodamine B. This observation suggests that the peptide backbone predominantly governs the structural features of the RhB-CH-1 conjugate, and that the incorporation of Rhodamine B into the sequence does not significantly alter the overall structural pattern relative to CH-1 (Figure S5, Supporting Information). The deconvolution of the Amide I band of peptide RhB-CH-1 showed that the secondary structure is composed of 32.5% β-sheets, 28.4% α-helices, and 39.1% β-turns (Figure S6, Supporting Information).

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of CH-1 and RhB-CH-1 chimeras dissolved in water exhibited random coil characteristics. In contrast, spectra obtained in aqueous solution containing 30% trifluoroethanol (TFE) revealed a minimum near to 206 nm, indicative of α-helical secondary structure elements (Figure S7, Supporting Information). The spectral differences between CH-1 and RhB-CH-1 may be attributed to the intrinsic absorbance of Rhodamine B in the UV region, which can influence CD measurements. These findings suggest that both CH-1 and RhB-CH-1 adopt α-helical conformations in hydrophobic environments.

In the 1H NMR spectrum of the CH-1 chimera, the integration of the observed signals totals 126 protons, which is consistent with the number of nonexchangeable protons in the peptide. The remaining protons are likely rapidly exchanged in D2O and therefore are not detected in the spectrum (Figure S8, Supporting Information). Upon analyzing the spectrum by regions, a segment between 7.0 and 7.6 ppm was observed corresponding to the indole ring protons of tryptophan, which is present in the peptide sequence. Notably, the peptide contains two tryptophan residues, each contributing five aromatic protons, yielding a total of 10 aromatic protons, in agreement with the integrated area of this region (highlighted in blue). In another region, between 3.7 and 4.6 ppm (highlighted in green), signals are observed that correspond to the α-protons of the amino acids. The integration of these signals gives a total of 15 protons, which matches the number of amino acid residues in the peptide, and thus the expected number of α-protons. Additionally, these signals appear as triplets, which is consistent with the peptide’s structure, where each α-proton is adjacent to a CH2 group and therefore couples with two neighboring protons. In the chemical shift range between 1.0 and 3.2 ppm, the signals arise from aliphatic side chain protons of various amino acid residues. Finally, below 1.0 ppm, a signal integrating for 24 protons can be seen, corresponding to the CH3 groups of the four leucine residues (Figure S8, Supporting Information).

On the other hand, analysis of the 1H–1H COSY spectrum reveals correlations between signals from different amino acid residues. For instance, correlations are observed between the CH3 and CH2 groups of the leucine side chains. Furthermore, the aliphatic side-chain protons show correlations with α-protons of amino acids, likely corresponding to glutamine and arginine. Additionally, at around 7.5 ppm, cross-peaks consistent with indole ring protons of tryptophan are evident, further confirming its presence in the peptide sequence (Figure S9, Supporting Information).

1H-1H TOCSY and NOESY experiments were also performed for the aforementioned peptide in D2O. The resulting spectra were overlaid, as shown in the figure, where the green traces correspond to the TOCSY experiment and the purple traces to the NOESY experiment. Analysis of the spectra reveals that the NOESY signals are very weak and do not indicate any correlations suggestive of spatial proximity between amino acid residues in the sequence. One limitation of this spectrum is the use of D2O as solvent, which leads to the exchange of NH protons with deuterium, rendering them unobservable. Since NH protons are among the most informative for detecting proximity interactions in NOESY experiments, their absence significantly limits structural interpretation. Conversely, the TOCSY spectrum displays scalar couplings between protons within individual amino acids present in the sequence, providing information complementary to that obtained from the COSY experiment and supporting the identification of the constituent residues (Figure S10, Supporting Information). 1H NMR spectrum of the peptide RhB-CH-1 allowed the identification of the signals of aromatic protons from the indole rings of Trp residues and aromatic protons from Rhodamine B, α-protons of each amino acid residue forming the peptide backbone, −CH2 protons from Rhodamine-B, aliphatic side-chain protons, and methyl group protons from Leu residues and Rhodamine-B (Figure S11, Supporting Information). 1H–1H COSY spectrum showed the coupling systems corresponding to Leu and Arg residues, protons from the aromatic system of Rhodamine-B and coupling of −CH3 and −CH2 protons from Rhodamine-B (Figure S12, Supporting Information). Overlapped 1H–1H TOCSY and 1H–1H NOESY spectra show signals present in the TOCSY spectrum but absent in the NOESY spectrum (Figure S13, Supporting Information).

Cytotoxic Activity

The CH-1 exhibited significantly selective cytotoxic activity in HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa and Ca Ski cells, which was fast and peptide concentration dependent (Figure , red line and Figure S14, Supporting Information). The CH-1 chimera had an IC50 value of 16 μM (34 μg/mL) and 14 μM (30 μg/mL) in HeLa and Ca Ski cells, respectively. The minimum cellular viability of HeLa and Ca Ski cells was near 0% and 15%, respectively, when the cells were treated with the peptide at 100 μg/mL and 200 μg/mL. The chimera was more active against HeLa cells than Ca Ski cells in peptide concentrations between 50 and 200 μg/mL.

1.

Effect of temperature on the cytotoxic activity of the CH-1 chimera (KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR) against the HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa and Ca Ski cells, after 2 h of treatment at 37 °C (red) and 4 °C (blue). Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests were used, p ≤ 0.05. Statistically significant differences were found between 37 and 4 °C.

Evaluation of the Endocytic Pathway

To assess if the cytotoxic activity of the CH-1 involves endocytosis, three assays were performed: i. evaluation of the cytotoxic effect at 4 °C; ii. evaluation of the cytotoxic effect in cells depleted in ATP; and iii. evaluation of the cytotoxic effect in the presence of endocytosis inhibitors.

In the first assay, the MTT assay was performed at 4 °C to determine whether energy-dependent pathways are involved in the cytotoxic effect. The cytotoxic effect of the peptide was fast and concentration-dependent following the same trend as at 37 °C. The results showed that when the cells were treated with the peptide at 4 °C, the cytotoxic effect in both cell lines diminished, as evidenced by the IC50 values obtained: in HeLa cells IC50 = 36.1 μM at 4 °C versus IC50 = 16.1 μM at 37 °C. The same behavior was observed for Ca Ski cells, IC50 = 42.2 μM at 4 °C versus IC50 = 14.3 μM at 37 °C. This decrease in cytotoxicity may be due to the slowing of the metabolism and other biological processes caused by the treatment at low temperature (Figure , blue line).

In the second assay, the cytotoxic effect of the CH-1 chimera in ATP-depleted cancer cells was determined. For this purpose, energy suppression was performed, treating HeLa and Ca Ski cells with sodium azide. No significant differences were observed between untreated cells (control) and cells treated with sodium azide at any of the concentrations tested in both cell lines (Figure ).

2.

Effect of depletion of cellular ATP on the cytotoxic activity of CH-1 (KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR) in the cervical cancer cell lines HeLa and Ca Ski after 2 h of treatment at 37 °C. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Two-way ANOVA and Sidak’s multiple comparisons test were used, p ≤ 0.05. No statistically significant differences were found between each concentration.

In the third assay, the cytotoxic effect of the CH-1 chimera on cancer cells was evaluated by previously subjecting the cells to pharmacological inhibitors that prevent endocytosis by one of the known pathways. For this, the cells were pretreated with two endocytosis inhibitors (nystatin or chlorpromazine) for a short period of time to prevent the development of late side effects or compensatory mechanisms. Subsequently, the cells were treated with the chimera and the MTT assay was performed. Nystatin was used because it is a drug that can inhibit lipid raft/caveolae-dependent endocytosis. Chlorpromazine is a cationic amphipathic drug that blocks clathrin-mediated endocytosis. The results show that for both cell lines (HeLa and Ca Ski), in the peptide concentration range of 0–200 μg/mL there was no difference in the cytotoxic effect whether cells were pretreated with nystatin or chlorpromazine compared to nonpretreated cells (control); i.e., there was no inhibitory effect by these substances on the cytotoxic effect of the chimera in the cells (Figure ). This allows inferring that the inhibited endocytosis pathways (lipid raft/caveolae-dependent endocytosis and clathrin-mediated endocytosis) are not involved in the process of entry of the chimera into the cancer cell.

3.

Effect of endocytosis inhibitors (nystatin and chlorpromazine) on the cytotoxic activity of the CH-1 chimera (KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR) in the HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa and Ca Ski cells after 2 h of treatment at 37 °C. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Two-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test were used, p ≤ 0.05. *Indicates statistically significant differences in cell viability (%) between treated and untreated cells.

Cell Viability vs Time

In this assay, the cytotoxic effect of the CH-1 chimera on HeLa cells was evaluated at different treatment times: 2, 24, and 48 h. The results show that at all three treatment times, cell viability decreased in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure and Table ).

4.

Cytotoxic activity of the CH-1 chimera (KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR) on the HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa cell line at different treatment times. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

1. Cytotoxic Effect of the CH-1 on HPV18-Positive Cervical Cancer Cells under Different Conditions .

| IC50 μg/mL (μM) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| condition evaluated | parameter | HeLa | Ca Ski |

| evaluation of the cytotoxic effect at 4 and 37 °C | 37 °C | 34 (16) | 30 (14) |

| 4 °C | 76 (36) | 88 (42) | |

| evaluation of the cytotoxic effect in cells depleted in ATP | untreated | 57 (27) | 101 (48) |

| sodium azide | 65 (31) | 86 (41) | |

| evaluation of the cytotoxic effect in the presence of endocytosis inhibitors | untreated | 57 (27) | 101 (48) |

| nystatin | 56 (26.5) | 74 (36) | |

| chlorpromazine | 55 (26) | 88 (42) | |

| cell viability vs time (IC50) | 2 h | 54 (26) | - |

| 24 | 75 (36) | - | |

| 48 | 104 (50) | - | |

| cytotoxic effect of the rhodamine B-labeled chimera in HeLa cells | CH-1 | 34 (16) | - |

| RhB-CH-1 | 16 (7) | - | |

- Indicates that assays were not performed on Ca Ski cells.

When HeLa cells were treated with the CH-1 chimera, IC50 values decreased with increasing treatment time. As treatment time increased (2, 24, and 48 h) cell viability at concentrations between 0 and 100 μg/mL also increased, while cell viability was similar and less than 20% at 200 μg/mL at 2, 24, or 48 h of treatment. The IC50 value decreased with increasing treatment time, with lower values for 2 h (26 μM) and 24 h (36 μM), while for the 48 h treatment (50 μM) the IC50 value increased 2-fold (Table ).

Furthermore, the cytotoxic effect of the chimera was determined as a function of treatment time on the HeLa and Ca Ski cell lines using the MTT assay. The cells were treated with the chimera at the IC50 concentration at different times (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 60, and 120 min) at 37 °C. The results show that for both cancer cell lines there is an effect on cell viability at 5 min of treatment and up to 2 h, where the death of half of the population occurs when dealing with the IC50 (Figure ).

5.

Cell viability vs treatment time of the HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa and Ca Ski cell lines treated with KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR chimera on at the IC50 concentration at 37 °C. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3).

Chimera-Precursor Competition

This assay was performed to evaluate whether the precursor peptide can inhibit the cytotoxic effect of the chimera. For this, HeLa cells were treated with RLLRRLLR (assay A), KKWQWK (assay B) or KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR (assay C) peptides for 2 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, the chimera KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR was added to each treatment and incubated for another 2 h. The results show that the pretreatment of the cells with the RLLRRLLR and KKWQWK precursors (assays A and B, respectively) did not have any effect on the activity of the chimera, since the viability curves, as well as the IC50 values, were similar to those obtained with only the chimera (control 1) (Figure ). The precursors RLLRRLLR (control 2) and KKWQWK (control 3) did not exhibit a cytotoxic effect in HeLa cells at the peptide concentrations evaluated during 4 h treatment at 37 °C. The retreatment at 2 h with CH-1 chimera (Assay C) induced a higher cytotoxic effect than the treatment at 0 h (control 1).

6.

Effect of precursor pretreatment on the cytotoxic activity of the KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR chimera in HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa cells. Cells were treated for 2 h at 37 °C with each precursor or the chimera (treatment 1), then washed and the chimera was added (treatment 2), and they incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). Two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test were used, p ≤ 0.05. *Statistically significant differences between experiment C and experiments A and B at the same concentration.

Type of Cell Death (Apoptosis/Necrosis)

The type of cell death was evaluated through flow cytometry assay with the Annexin V/7AAD kit by treating HeLa cells with the CH-1 chimera for 24 h at IC50 (16 μM; 33 μg/mL), 2× IC50 (32 μM; 66 μg/mL), and 4× IC50 (64 μM; 132 μg/mL). The results showed that the cytotoxicity of the chimera at the IC50 (16 μM) is mainly associated with early apoptosis events (45.0%) and to a lesser extent with late apoptosis (10.4%). Doubling and quadrupling the concentration (32 and 64 μM, respectively) resulted in a higher percentage of late apoptosis events associated with the increase in the amount of peptide. Interestingly, necrotic events were less than 0.5% in all cases, suggesting that the cytotoxic effect of chimera at high concentrations preferentially induces apoptosis-mediated cell death in HeLa cells (Figure and Table ).

7.

Flow cytometry assay for determining the type of cell death (apoptosis/necrosis) in HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa cells treated with the CH-1 chimera (KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR) and RWQWRWQWR peptide for 24 h at 37 °C at different concentrations. (A) Representative dot plots of the treatments in the annexin V and 7AAD channels. Q1: Necrosis events, Q2: late apoptosis, Q3: early apoptosis, and Q4: live cell events. Apoptosis control: formaldehyde 25%, negative control: culture medium. (B) Bar graph of the percentage of live cell-related events, early apoptosis, late apoptosis, or necrosis, in each of the treatments; chimera (IC50, 2× IC50 and 4× IC50) and palindromic peptide at IC50, (n = 2), two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons. aStatistically significant differences with the percentage of late apoptosis in untreated cells, p < 0.0001. bStatistically significant differences with the percentage of early apoptosis in untreated cells, p < 0.0001. cStatistically significant differences with the percentage of live untreated cells, p < 0.0001.

2. Percentage of Events Related to Live Cells in Early Apoptosis, Late Apoptosis, or Necrosis in the Flow Cytometry Assay for the Determination of the Type of Cell Death (Apoptosis/Necrosis) in HPV18-Positive Cervical Cancer HeLa Cells Treated with CH-1 for 24 h at 37 °C (n = 2).

| concentration | live cells | early apoptosis | late apoptosis | necrosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 | 44.5 | 45.0 | 10.4 | 0.1 |

| 2× IC50 | 34.1 | 43.4 | 22.2 | 0.4 |

| 4× IC50 | 22.1 | 50.6 | 27.2 | 0.2 |

| untreated | 94.3 | 4.6 | 1.1 | 0.0 |

| formaldehyde 25% | 4.1 | 5.2 | 90.1 | 0.6 |

| RWQWRWQWR | 75.8 | 19.5 | 4.5 | 0.3 |

For this assay, a peptide molecule derived from LfcinB, the palindromic peptide RWQWRWQWR, was also used as a positive control for apoptosis. The results show that, upon treatment with the peptide at IC50 (32 μM; 48 μg/mL), most cells were alive (75.8%) and to a lesser extent suffered early apoptosis (19.5%) or late apoptosis (4.5%) (Table ). This may be because the cells divided after 24 h and there is no peptide available to cause an effect on them. A second assay was conducted to further evaluate the cytotoxic effects of CH-1 on HeLa cells. Cells were treated, for 24 h, with CH-1 (60 μg/mL), actinomycin D (16 μM) as a positive control for apoptosis or EDTA (15 mM) as a necrosis control. Flow cytometry analysis using annexin V and 7-AAD staining revealed that CH-1 treatment resulted in apoptosis-mediated cell death, as evidenced by increased annexin V fluorescence intensity and cell distribution in apoptotic quadrants (Figure S14, Supporting Information).

Detection of Caspase 3 and 7 Activity

The caspase 3 and 7 activity assay was performed to determine if the cell death suffered by HeLa cells due to the action of the CH-1 activates apoptosis-associated enzymes, using a luminescence method. The HeLa cells were treated with CH-1 chimera at 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL for 2 h at 37 °C. The expression of caspases 3 and 7 decreased as the peptide concentration increased. The expression of caspases 3 and 7 was maximal when HeLa cells were treated with CH-1 at 25 μg/mL, which is associated with induction of apoptosis (Figure ).

8.

Activation of caspases 3 and 7 in HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa cells after treatment with the KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR chimera for 2 h at 37 °C. Caspase activity is expressed as a percentage relative to untreated cells (control). Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). One-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests were used, p ≤ 0.05. ****Indicates statistically significant differences between peptide-treated cells (25 and 100 μg/mL) and untreated cells. **Indicates statistically significant differences between peptide-treated cells (45 μg/mL) and untreated cells.

Contrast Microscopy

HeLa and Ca Ski cells were observed for 1 h after addition of treatment using contrast microscopy. Videos were acquired that demonstrate the effect of the chimera on the two cancer cell lines. The videos, presented in time-lapse format (12 and 26 s long), facilitate visualization of the cellular changes (Supporting Information). The recordings show the morphological changes that the cells undergo after contact with the chimera. In HeLa cells, a progressive loss of the elongation and projections characteristic of these cells was observed, as well as cytoplasmic condensation and a reduction in cell volume. The cells undergo changes characteristic of apoptosis, such as rounding, a significant decrease in size, and vacuole formation. The morphological changes become visible approximately 5 min after the addition of the peptide, indicating a rapid effect. During the treatment there was no evident necrotic process, which is consistent with the previous results. In Ca Ski cells, behavior like that observed in HeLa cells was observed, with decreased cell size, increased cytoplasmic density, cell rounding, and vacuole formation. The similarity in the response of both cell lines suggests that the chimera has a consistent effect on different types of cancer cells and reinforces the idea that it can induce apoptosis in different cell lines.

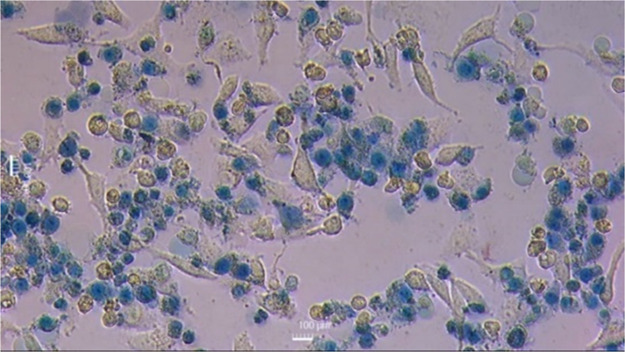

Membrane Integrity

Cells treated with CH-1 showed morphological changes (loss of prolongations, rounding, and shrinkage) involving cell membrane alterations. To determine whether plasma membrane alterations are caused by prolonged exposure to the peptide, CH-1-treated cells were photographed at treatment times of 0, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 10, 12, 15, 17, 18, and 20 min. Morphological changes, such as loss of prolongations, rounding and shrinkage, were evident as early as 2 min, and the involvement of the majority of the cell population was observed at 5 min of treatment, suggesting that these cell membrane alterations caused by CH-1 are instantaneous (Figure S15, Supporting Information).

HeLa cells were stained with trypan blue after being treated with the chimera at IC50 for 2 h at 37 °C. The photomicrograph shows a group of cells that did not take up the dye and remained colorless with an elongated morphology, demonstrating an intact cell membrane. Another group of cells was observed with loss of projections, rounded, and smaller, and were not stained with the dye. Additionally, a group of stained cells with loss of projections, rounded, and smaller, were observed. These cells stained blue and correspond to cells in which membrane integrity was possibly compromised (Figure ). This result may suggest that in the final stages of apoptosis, the membrane integrity of some cells was compromised, allowing the dye to enter. However, the cells remained intact, with no visible evidence of necrosis.

9.

Contrast microscopy micrograph (200×) of HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa cells after treatment with the KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR chimera for 2 h at 37 °C and subsequent staining with trypan blue.

Subcellular Localization through Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy

To perform this assay, the chimera was previously labeled at the N-terminus with Rhodamine B using SPPS-Fmoc/tBu, obtaining the RhB-KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR (RhB-CH-1) peptide with a purity of 98% and the molecular mass corresponding to the expected (Figure S16, Supporting Information). The cytotoxic effect of RhB-CH-1 on HeLa cells was like that observed for the CH-1 chimera (IC50 = 34 μg/mL/16 μM), being rapid, peptide concentration-dependent, and the IC50 was determined (IC50 = 16 μg/mL/7 μM) (Figure S17, Supporting Information). As a control, the cytotoxic effect of rhodamine B was determined in HeLa cells; the cell viability graph showed that rhodamine B exerted a cytotoxic effect on cells in a concentration-dependent manner, however, the IC50 value (IC50 = 100 μg/mL/209 μM) was significantly higher than that of CH-1 (Figures S17 and S18, Supporting Information). CH-1 and RhB-CH-1 are 13 and 29-fold more cytotoxic than Rhodamine B, respectively, suggesting that the peptide sequence mainly influences the activity of the RhB-CH-1 chimera and that incorporation of Rhodamine B at the N-terminal end of the chimera sequence enhanced the cytotoxic activity compared to the CH-1 chimera (Figures S17 and S18, Supporting Information).

An immunofluorescence assay of the HeLa cells was performed using the SMAC antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488, which binds to actin and fluoresces green. Hoechst 33342 solution, a nuclear DNA dye that fluoresces blue, was also used. HeLa cells were pretreated with the Rhodamine B-conjugated peptide, which fluoresces red. The results clearly show the nucleus (blue channel), the actin in the cytoplasm of the cells (green channel), and the location of the rhodaminated peptide (red channel) (Figure ). The RhB-KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR peptide (red) is in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus, as evidenced by the microphotographs and the colocalization results. This suggests that the chimera can enter cancer cells, and its cytotoxic effect is not limited to its activity at the cell membrane (Figure ). Once the peptide enters the cells, it spreads throughout the cytoplasm and various organelles, such as the nucleus. Since this assay was performed at the IC50 of the rhodaminated peptide, both dead and live cells were observed. The cells showed the same morphological changes described above, such as condensed chromatin in the nucleus, decreased cell size, denser cytoplasm, and rounded cell shape, confirming that the chimera induces cell death by apoptosis.

10.

Confocal fluorescence microscopy micrographs (1000×) of HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa cells treated with the RhB-KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR chimera for 2 h at 37 °C at the IC50. RhB-KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR can be seen in the red channel, Hoechst 33342 can be seen in the blue channel, and SMAC-Alexa Fluor 488 can be seen in the green channel. The open arrows show the colocalization of the RhB-Peptide signal with each fluorophore.

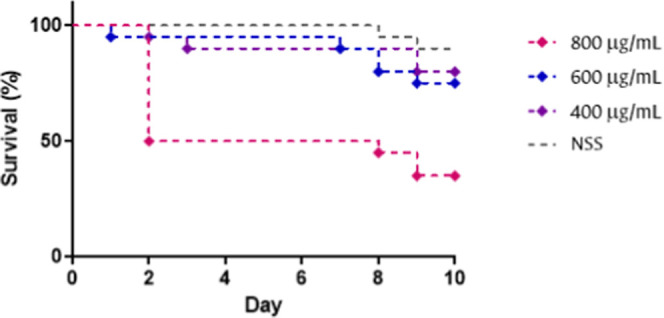

Toxicity in G. mellonella

This in vivo model was chosen to assess the toxicity of the chimera because it is an inexpensive, easy, and rapid method. Furthermore, its use is not restricted by legal or ethical considerations, and the results show a strong correlation with those of 3T3 cell lines (mouse embryonic fibroblasts) and normal human and mouse keratinocytes, so much so that it can even provide more accurate results than toxicity assays in cell lines.

The toxicity was determined by intraperitoneal injection of the chimera into larvae and monitored for 10 days thereafter. The survival curve (Figure ) shows that at 400 μg/mL (20 mg/kg), survival was 80%, and at 600 μg/mL (30 mg/kg), it was 75%. However, at a concentration of 800 μg/mL (40 mg/kg) survival was only 35%, with the lethal dose 50 (LD50) between 600 and 800 μg/mL This result is consistent with the cytotoxicity exhibited by the chimera in the L929 cell line (IC50 = 45 μM) and allows the chimera to be classified as “highly toxic” according to the Loomis & Hayes classification.

11.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve of Galleria mellonella larvae treated with the KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR chimera at different concentrations. n = 10 with two biological replicates. SSN: normal saline solution.

Toxicity in Zebrafish (D. rerio)

The zebrafish model was used to evaluate the acute toxicity of the chimera through the survival of the embryos following administration of the peptide at different concentrations. This vertebrate model offers the advantages of its small size, rapid development, easy reproduction, and transparency, which allows the morphological effects suffered by the embryo to be detected through microscopic observation. Furthermore, it is widely used in the development of new drugs, because it allows evaluation of cardiotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, genotoxicity, and efficacy. ,

The results indicate that individuals treated with peptide concentrations ranging from 0 to 20 μg/mL exhibited 100% survival after 3 days of treatment. In contrast, higher concentrations (25–50 μg/mL) resulted in 100% mortality within the first 24 h (Figure ). It is noteworthy that at concentrations of 40 μg/mL and 50 μg/mL, accelerated embryonic behavior was observed 30 min after the addition of the peptide, producing 100% mortality; however, the other concentrations did not produce mortality during this period. Nonetheless, after 24 h exposure to concentrations of 25 μg/mL and 30 μg/mL, 100% mortality occurred.

12.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of Danio rerio embryos treated for 3 days with varying daily concentrations of CH-1 peptide. (A) Low-dose group: 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 15, and 20 μg/mL. (B) High-dose group: 25, 30, 40, and 50 μg/mL.

In accordance with the above, it was possible to determine the lethal concentration of the peptide for 50% of the population (LC50) in the range of 20–25 μg/mL, and according to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) acute toxicity grading scale, the chimera was classified as slightly toxic.

A few treated embryos suffered malformations such as pericardial edema, yolk sac edema, kyphosis, lordosis, and scoliosis at the concentrations tested; however, these malformations were not significant and were considered nonspecific.

Discussion

The synthesis of the CH-1 chimera was carried out using 200 and 700 mg of Rink amide resin to determine whether the scaling of the synthesis affects the identity and integrity of the peptide. The results showed that both products presented retention times, purities and molecular weights that correspond to the theoretical values. The FT-IR and NMR spectra of batches 1 and 2 are identical, suggesting that the scale-up of the CH-1 chimera synthesis is feasible and reproducible, so batch 2 was chosen for further experiments (Figures S1 and S2, Supporting Information).

FT-IR, DC and NMR experiments indicated that the chimera CH-1 (KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR) and Rod-B-CH-1 (RhB-KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR) show α-helix secondary elements (Figures S3–S7, Supporting Information). The 6-aminohexanoic acid (Ahx) used as a spacer to link the two sequences is an unstructured hydrocarbon chain. Fragment KKWQWK is derived from the minimal motif of LfcinB: RRWQWR, which was classified as a random coil, since circular dichroism analysis shows that it does not have secondary structural elements. In addition, the analogue oncolytic peptide LTX-315 (KKWWKK-Dip-K-NH2) has a random structure determined by circular dichroism. , On the other hand, the peptide (RLLR)5, containing five times the motif RLLR, showed an α-helix conformation. Furthermore, it was described that buforin II 1TRSSRAGLQFPVGRVHRLLRK showed a regular α-helix between Val and Arg and amphipathic properties. , The peptide Buf IIb RAGLQFPVGRLLRRLLRRLLR exhibited activity against HeLa, MX-1, MCF-7, and T47-D cell lines and inhibited the progression of cancer in vivo. These results suggested that the anticancer activity of the CH-1 chimera could be due to the interaction between the KKWQWK and/or RLLRRLLR motifs and the cells, inducing a fast, selective cytotoxic effect in HeLa and Ca Ski cells.

The cytotoxic effect of the CH-1 on HPV18-positive cervical cancer HeLa and Ca Ski cells was rapid and peptide concentration-dependent. These results are consistent with the cytotoxic activity observed in other chimeras containing short sequences derived from LfcinB and Buforin II. The chimeras RWQWRWQWR-Ahx-RLLRRLLR (IC50 values 13 and 17 μM) and RLLRRLLR-Ahx-RWQWRWQWR (IC50 values 16 and 22 μM) exhibited a rapid, selective, and concentration-dependent cytotoxic effect against HeLa and Ca Ski cells, with a selectivity index greater than 13. In addition, these chimeras also showed significant cytotoxic activity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells (IC50 = 39 μM) and antimicrobial activity against clinical isolates of C. neoformans var. grubii, and reference strains of E. coli ATCC 25922, E. coli ATCC 11775, S. aureus ATCC 29213, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, and E. faecalis ATCC 29212. ,,

Similarly, the analogous chimeras RLLRRLLR-Ahx-RRWQWR, RRWQWR-Ahx-KLLKKLLK, and KKWQWK-Ahx-KLLKKLLK manifested antibacterial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains. Our results, as well as those described above, suggest that chimeric design using short sequences derived from LfcinB and Buforin II is a promising strategy for identifying peptides with broad-spectrum anticancer and antimicrobial activity.

The CH-1 chimera showed a similar cytotoxic effect on HeLa and Ca Ski cells when treatment was carried out at 4 or 37 °C (Figure and Table ). Similarly, the cytotoxic effect of the peptide was not altered when cells were pretreated with endocytosis inhibitors or sodium azide (Figures and and Table ). These results suggest that the uptake of the chimera was not affected by the ATP deficiency in the cells; that is, the mechanism is not energy-dependent and therefore suggests that internalization is not mediated by endocytosis.

This result shows that the cytotoxic effect of the chimera on the cells occurs even at low temperatures. The guanidino groups of Arg residues form hydrogen bonds and interact electrostatically with the sulfate, phosphate, and carboxylate groups of the cell surface, as well as with membrane proteins, proteoglycans, phospholipids, and sialic acids; these interactions possibly cause the accumulation of the peptide on the cell surface and induce membrane alteration leading to internalization. The results suggested that the cytotoxic effect of the chimeras on the cancer cells tested involved a transport process across the membrane, possibly mediated by receptor–ligand interaction without causing membrane destabilization. , Our results agree with previous reports that demonstrated that LfcinB interacts with the cell membrane of Jurkat T leukemic cells at 10 min of treatment, causing a dose-dependent cell membrane permeabilization. However, the minimal motif RRWQWR did not cause membrane rupture in Jurkat cells and did not internalize the cell; on the other hand, buforin II and derived peptides internalized Jurkat and HeLa cells without affecting membrane integrity. ,,

The cytotoxic effect of the CH-1 on treated cells at 24 and 48 h of treatment gradually decreased 1.4- and 2-fold, respectively, compared to that observed at 2 h of treatment (Figure and Table ). The increase in cell viability of HeLa cells at 24 and 48 h of treatment is much lower than expected, considering the replication time of these cell lines, suggesting that the chimera is active at 24 and 48 h of treatment, inhibiting cell growth. The increased cellular viability at a peptide concentration between 0 and 100 μg/mL may be associated with the duplication of cells unaffected by the chimera, since the doubling time of this cell line is approximately 20 h. However, cell recovery was lower than expected, suggesting that the peptide can exert its cytotoxic effect for up to 48 h without significant loss of activity. It is noteworthy that at the highest concentration (200 μg/mL), cell viability was similar regardless of incubation time, suggesting that at this concentration, the cell population was destroyed, and replication was inhibited.

These results agree with the fact that chimeras containing LfcinB and buforin sequences, as well as short synthetic peptides containing the minimal RRWQWR motif, had a cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells up to 72 h after treatment. ,− Furthermore, the camel lactoferrin coil exerted a significant cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells, which was protein concentration-dependent and was maintained up to 48 h of treatment. Buforin IIb exhibited cytotoxic activity against HeLa (IC50 = 12 μg/mL) and Jurkat (IC50 = 6 μg/mL) cells after 24 h of treatment. The cytotoxic effect of the chimera is sustained over time; this aspect is relevant in the case of a potential therapeutic application, since fewer retreatments are required to maintain the cytotoxic effect.

The cell viability of HeLa and Ca Ski cells treated with the CH-1 chimera at IC50 was monitored for 2 h of treatment with MTT assay. The cell viability of HeLa and Ca Ski cells decreased as treatment time increased (Figure ). The cell viability of HeLa and Ca Ski cells was similar to each other at all times evaluated. The cell viability of both cells decreased progressively with increasing treatment time, becoming evident starting at 5 min of treatment. Note that after 2 h of treatment, the cell viability of HeLa or Ca Ski cells was 50%. These results are in agreement with the fact that when Jurkat and HeLa cells were treated with LfcinB, the cytotoxic activity was instantaneous and was maintained for 2 h. , In addition, chimeras and short peptides containing LfcinB-derived sequences exhibited a selective and significant cytotoxic effect at 2 h of treatment in breast, colon, prostate, oral, and cervical cancer cells. ,− These results suggest that the cytotoxic effect of the CH-1 on the cancer cells occurs from the moment the treatment is added. Cell viability decreased over time, indicating that the cytotoxic effect of the chimera on HeLa and Ca Ski cells is instantaneous and dependent on the treatment duration. It is necessary to study the cytotoxic activity of CH-1 in other cervical cancer cell lines, including HPV-negative cervical cancer cells such as A33 cells, to establish the spectrum of action, which is beyond the scope of this research.

Assays A, B, and control 1 produced the same effect in HeLa cells, which is consistent with the results of the cytotoxic activity of the precursors, where it was observed that the peptides KKWQWK (IC50 = >222 μM) and RLLRRLLR (IC50 = >183 μM) did not exhibit a cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells (Figure , assays A and B). These results agree with those previously reported that showed that these peptides do not exert cytotoxic activity in these cells, suggesting that chemical binding of these two sequences in the CH-1 chimera is required for anticancer activity.

To assess whether the precursor sequences can inhibit the cytotoxic effect of the chimera, a competition assay was performed between the CH-1 and each of its precursors. The cytotoxic effect of the CH-1 was not inhibited by the presence of the precursor peptides, indicating that the activity of the chimera requires the two sequences, KKWQWK and RLLRRLLR, to be bound in a peptide entity. When the cells were treated a second time at 2 h with the CH-1 (IC50 = 10 μM) (Figure , assay C), the cytotoxic effect was greater than when the cells were treated only once (IC50 = 16 μM) (Figure , control 1). These results agree with previous reports that showed that chimeras containing the palindromic sequence RWQWRWQWR exhibited significant cytotoxic activity against HeLa and Ca Ski cells, whereas the peptide precursors of these chimeras exerted no cytotoxic effect at the concentrations tested. These results suggested that if a cell death-activating membrane receptor or a target intracellular specific for the chimera exists, they have no affinity for the precursors, and the latter do not act competitively. When cells were retreated with the chimera (assay C), a decrease in cell viability was observed at different concentrations. This may be because cells that remained viable after the first treatment with the chimera were affected upon the next addition of the chimera, as evidenced by the shift in the curve and the decrease in the IC50 value (IC50 = 10 μM) compared with the control 1 (IC50 = 16 μM) (Figure ).

Cytometry assays using annexin V and 7AAD fluoromarkers showed that 24 h treatment of HeLa cells with the CH-1 at 33, 66, or 132 μg/mL mainly induced apoptosis-mediated cell death (Figure , Q2 and Q3), with minimal cell populations undergoing necrosis (less than 1% in all cases) (Figure , Q1). The main cell population was found in early apoptosis (Figure , Q3), with double that of those in later apoptosis (Figure , Q2). The cell death type observed was independent of the peptide concentration and treatment time. These results are consistent with the type of cell death induced by the RWQWRWQWR peptide in MCF7 breast and Caco-2 cancer cells. , However, in Caco2 colon cancer cells, this peptide not only causes late and early apoptosis, but necrotic processes. Therefore, this result is considered promising, since the cytotoxic effect of the peptides RWQWRWQWR and KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR in HeLa cells does not cause necrotic death. The results of the chimera and the peptide correlate with the type of cell death reported for LfcinB-derived peptides in cells of various types of cancer, where the induction of apoptotic death predominates. − It has been suggested that the cytotoxic mechanism of action of these cationic peptides derived from LfcinB, including the CH-1 chimera, is related to the electrostatic interaction between the positively charged side chains of the peptide and the negatively charged molecules of the cell membrane. Subsequently, the interaction of Trp and Arg residues with the lipid bilayer occurs, causing its disruption, leading to cell lysis or peptide internalization. The RLLRRLLR segment also plays an important role in the activity, since it has been reported that the buforin IIb peptide (RAGLQFPVG(RLLR)3), which contains this motif, interacts with cancer cell gangliosides, penetrates cells without damaging the membrane, and triggers mitochondrial apoptosis by activating caspase 9 through mitochondria-dependent and endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated pathways. , In this way, the chimera induces HeLa cell death through apoptosis (early and late) and does not generate necrosis, in accordance with the cell death mechanisms associated with its component precursor peptides. Caspases 3 and 7 are apoptosis-executioner enzymes and serve as substrates for initiator caspases in the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways; they direct cellular degradation through the cleavage of structural proteins. It can be seen that as the concentration of the chimera increases, there is greater cell death, decreasing caspase concentration (Figure ), suggesting that at higher peptide concentrations, there is a greater number of cells that have already undergone apoptosis, while the number of cells undergoing apoptosis decreases.

Flow cytometry assays demonstrated that CH-1 retains its biological activity up to 24 h post-treatment. Notably, an increase in the population undergoing late apoptosis was observed at higher peptide concentrations. This suggests that caspase activation may not be directly correlated with CH-1 activity under these conditions. These findings align with previous reports indicating that apoptosis induced by LfcinB in B lymphoma cells at high concentrations (50 μM) occurs independently of caspase activation. Nevertheless, further investigation is required to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the apparent reduction in caspase involvement at elevated peptide levels. The observed results are consistent with flow cytometry-based analyses of cell death induced by short synthetic peptides derived from LfcinB in breast and colon cancer cell lines. ,

The morphological changes observed in HeLa and Ca Ski cells treated with the CH-1 chimera were decreased cell size, increased cytoplasmic density, cell rounding, and vacuole formation. There was no evidence that the cells underwent a necrotic process. The videos illustrate the effect induced by the CH-1 in HeLa and Ca Ski cells in real time; the transformation that the cells undergo under the action of the chimera is dramatic and severe (Supporting Information). Severe morphological changes were already evident after 5 min of treatment. The affected cells acquire morphological characteristics of cells undergoing an apoptotic process. During treatment, no disintegration, cell rupture, or cell changes indicative of cell necrosis were observed. These results are consistent with previous reports showing that LFB, chimeras, and LfcinB-derived peptides induced similar morphological changes in HeLa cells and other cancer cell lines. ,− ,

Treatment of HeLa cells with trypan blue revealed that some cells exhibiting morphological changes, such as loss of projection, rounding, and shrinkage, were stained in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Figure ). These cells may be in the late stages of the apoptotic process, during which the cell membrane may be permeable. However, there is no evidence of cell necrosis, which is consistent with cytometry assays. Confocal microscopy assays were performed with the rhodamine-labeled chimera at the N-terminal end (Figure ). The RhB-CH-1 chimera (RhB-KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR) was synthesized by means of SPPS-Fmoc/tBu, purified via RP-SPE and characterized using RP-HPLC and LC–MS (Figure S16, Supporting Information). The RhB-CH-1 chimera was more cytotoxic to the cervical cancer cells tested than the unlabeled chimera, indicating that incorporation of Rhodamine B at the N-terminal end of the sequence enhanced cytotoxic activity (Figure S14, Supporting Information). Rhodamine B bound to the alpha-amine group of the sequence, decreasing the net charge to +7 and increasing the hydrophobicity of the chimera. Rhodamine B is a bulky molecule that could affect the interaction of the N-terminal region of the chimera with the cell by steric hindrance. The RhB-CH-1 internalized into HeLa cells, colocalizing in the cytoplasm and nucleus without affecting the membrane.

Our results are in agreement with previous reports that demonstrated that buforin IIb internalizes HeLa cells, inducing apoptosis and upregulation of stress proteins. Biotin-labeled buforin IIb penetrated HeLa cells without causing membrane disruption and accumulated in the nucleus. Other reports show that buforin crosses the cell membrane without altering it, and its intracellular accumulation induces cell death by apoptosis in HeLa cells. In addition, it has been suggested that buforin interacts with membrane receptors, inhibiting cell proliferation and angiogenesis. On the other hand, the RRWQWR peptide had no internalization capacity and did not cause damage to Jurkat cells, whereas internalization of this peptide through liposomes induced apoptosis-mediated cell death. These results suggest that the (RLLR)2 motif is relevant in cell internalization of the CH-1. Our results indicate that the C-terminal region of the chimera containing the (RLLR)2 motif is relevant for the internalization of the chimera in HeLa cells. Furthermore, it can be suggested that the KKWQWK-ahx-RLLRRLLR sequence can be used as a transporter and drug delivery system.

Research into in vivo models, such as G. mellonella and zebrafish, has allowed the toxicity and efficacy of the chimera to be evaluated in complete biological systems. Toxicity of the CH-1 was high and mild in G. mellonella and zebrafish, respectively. The CH-1 was selective for cancer cells, and the observed toxicity suggests that this peptide can be considered safe, and the LD50 values provide valuable information for future clinical trials.

In summary, the CH-1 peptide was successfully synthesized via SPPS-Fmoc/tBu and scaled up without compromising its structural integrity or identity. Its cytotoxic effect on HPV18-positive cervical cancer cell lines (HeLa and Ca Ski) was found to be rapid, selective, and concentration-dependent. The cytotoxic activity of the CH-1 chimera persisted for up to 48 h and exhibited time-dependent behavior within the first 2 h of treatment. CH-1 induced pronounced morphological alterations, efficiently internalized into HeLa cells, colocalized within both the cytoplasm and nucleus, and triggered apoptosis. The peptide chimera KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR emerges as a promising therapeutic candidate for cervical cancer. This study demonstrates that chemically linking two sequences with low individual activity can yield a chimeric peptide with enhanced cytotoxicity, improved cellular uptake, and apoptosis-mediated cell death induction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and the Universidad Europea de Madrid. The authors also acknowledge to Laboratorio Instrumental de Alta Complejidad (LIAC) and the Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Transferencia, Universidad de la Salle, for the research funding.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Ahx

6-aminohexanoic acid

- LfcinB

lactoferricin B

- AMP

antimicrobial peptide

- SPPS

solid phase peptide synthesis

- DMF

N,N dimethylformamide

- DCM

dichloromethane

- RT

room temperature

- DCC

dicyclohexylcarbodiimide

- 6-Cl-HOBt

6-chloro-2-hydroxybenzotriazol

- TIPS

triisopropylsilane

- EDT

ethanedithiol

- RhB

Rhodamine B

- DIPEA

diisopropylethylamine

- TBTU

o-benzotriazol-1-yl-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium tetrafluoroborate

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- ACN

acetonitrile

- RP-SPE

reverse phase solid phase extraction

- BFS

bovine fetal serum

- DNEM

Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- FT-IR

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supporting Information.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.5c05953.

Videos 1 and 2 taken of HeLa and Ca Ski cells using contrast microscopy for 1 h after the addition of the chimera KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR. Figure S1. Characterization by RP-HPLC of the CH-1 chimera KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR. Figure S2. Characterization by LC–MS of the CH-1 chimera: KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR (Theoretical mass 2091.353 u). Figure S3. FT-IR spectrum of the CH-1 chimera. Figure S4. Deconvolution of the Amide I band in the FT-IR spectrum of CH-1. Figure S5. FT-IR spectrum of the Rhodamine B (A, pink), RhB-CH-1 (B, green), chimera CH-1 (C, blue). Figure S6. Deconvolution of the Amide I band of peptide RhB-CH-1. Figure S7. Circular dichroism spectra of CH-1 (blue) and RhB-CH-1 (red) were recorded in water (A) and in 30% trifluoroethanol (TFE) in water (B). Figure S8. 1H NMR spectrum of CH-1 in D2O (400 MHz). Figure S9. 1H–1H COSY spectrum of CH-1 in D2O (400 MHz). Figure S10. Overlapped 1H–1H TOCSY and 1H–1H NOESY spectra of the peptide KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR-NH2 in D2O (400 MHz). Figure S11. 1H NMR spectrum of the peptide RhB-KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR-NH2 in DMSO-d 6 (400 MHz). Figure S12. 1H–1H COSY spectrum of the peptide RhB-KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR-NH2 in DMSO-d 6 (400 MHz). Figure S13. Overlapped 1H–1H TOCSY and 1H–1H NOESY spectra of the peptide RhB-KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR-NH2 in DMSO-d 6 (400 MHz). Figure S14. Effect of CH-1 on HeLa Cells. (A) HeLa cells were treated with CH-1 (60 μg/mL), actinomycin D (16 μM), or EDTA (15 mM) for 24 h. Figure S15. HeLa cells were microphotographed after treatment with RhB-1 or RhB-2 for 2 h at 37 °C (peptide concentration 100 μg/mL). Figure S16. Peptide chimera RhB-KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR. Figure S17. Cytotoxic effect of CH-1 (KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR) and RhB-CH-1 (RhB-KKWQWK-Ahx-RLLRRLLR) against HeLa cell line. Figure S18. Cytotoxic effect of Rhodamine B (PDF)

NAC: Conceptualization, investigation, data analysis, writing. ACBC: Conceptualization, data analysis, investigation, writing. JERC: data analysis, investigation, writing. DSFZ: data analysis, investigation, writing. EAMC: data analysis, investigation, writing. JERM: data analysis, investigation, writing, supervision. EMS: supervision and funding acquisition. CCG: supervision and funding acquisition. CMPG: data analysis, investigation, writing, supervision. RFM: supervision and funding acquisition. ZJRM: investigation, writing, funding acquisition, supervision. JGC: investigation, writing, funding acquisition, supervision.

This research was conducted with the financial support of MinCiencias through the project: “Obtención de un prototipo peptídico promisorio para el desarrollo de un medicamento de amplio espectro para el tratamiento del cáncer de colon, cuello uterino y próstata”. Contract RC No. 845-2019.

All authors declare that all methods reported here were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the National University of Colombia (code 01-2023). This present material is the original work of the authors and has not been previously published elsewhere.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- World Health Organization . International Agency for Research on Cancer; World Health Organization, 2019. https://www.iarc.who.int/cancer-type/cervical-cancer/ (accessed 19 July 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Small W., Bacon M. A., Bajaj A., Chuang L. T., Fisher B. J., Harkenrider M. M., Jhingran A., Kitchener H. C., Mileshkin L. R., Viswanathan A. N., Gaffney D. K.. Cervical Cancer: A Global Health Crisis. Cancer. 2017;123(13):2404–2412. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardila-Chantré N., Parra-Giraldo C. M., Vargas-Casanova Y., Barragán-Cardenas A. C., Fierro-Medina R., Rivera-Monroy Z. J., Rivera-Monroy J. E., García-Castañeda J. E.. Hybrid Peptides Inspired by the RWQWRWQWR Sequence Inhibit Cervical Cancer Cells Growth in Vitro. Explor. Drug Sci. 2024;2:614–631. doi: 10.37349/eds.2024.00064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda-Castañeda H. M., Huertas-Ortiz K. A., Leal-Castro A. L., Vargas-Casanova Y., Parra-Giraldo C. M., García-Castañeda J. E., Rivera-Monroy Z. J.. Designing Chimeric Peptides: A Powerful Tool for Enhancing Antibacterial Activity. Chem. Biodiversity. 2021;18(2):e2000885. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.202000885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Sánchez A. G., Rodríguez-Mejía K. G., Cuero-Amu K. J., Ardila-Chantré N., Reyes-Calderón J. E., González-López N. M., Huertas-Ortiz K. A., Fierro-Medina R., Rivera-Monroy Z. J., García-Castañeda J. E.. A New Methodology for Synthetic Peptides Purification and Counterion Exchange in One Step Using Solid-Phase Extraction Chromatography. Processes. 2025;13(1):27. doi: 10.3390/pr13010027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre-Guataqui K., Márquez-Torres M., Pineda-Castañeda H. M., Vargas-Casanova Y., Ceballos-Garzon A., Rivera-Monroy Z. J., García-Castañeda J. E., Parra-Giraldo C. M.. Chimeric Peptides Derived from Bovine Lactoferricin and Buforin II: Antifungal Activity against Reference Strains and Clinical Isolates of Candida Spp. Antibiotics. 2022;11(11):1561. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11111561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal S. K., Vargas-Casanova Y., Pineda-Castañeda H. M., García-Castañeda J. E., Rivera-Monroy Z. J., Parra-Giraldo C. M.. In Vitro Antifungal Activity of Chimeric Peptides Derived from Bovine Lactoferricin and Buforin II against Cryptococcus Neoformans Var. Grubii. Antibiotics. 2022;11(12):1819. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11121819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolos Vasii A. M., Moisa C., Dochia M., Popa C., Copolovici L., Copolovici D. M.. Anticancer Potential of Antimicrobial Peptides: Focus on Buforins. Polymers. 2024;16(6):728. doi: 10.3390/polym16060728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi G.-S., Park C. B., Kim S. C., Cheong C.. Solution Structure of an Antimicrobial Peptide Buforin II. FEBS Lett. 1996;398:87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnaud S., Evans R. W.. Lactoferrin - A Multifunctional Protein with Antimicrobial Properties. Mol. Immunol. 2003;40(7):395–405. doi: 10.1016/S0161-5890(03)00152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Montoya I. A., Cendón T. S., Arévalo-Gallegos S., Rascón-Cruz Q.. Lactoferrin a Multiple Bioactive Protein: An Overview. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj. 2012;1820(3):226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. S., Park C. B., Kim J. M., Jang S. A., Park I. Y., Kim M. S., Cho J. H., Kim S. C.. Mechanism of Anticancer Activity of Buforin IIb, a Histone H2A-Derived Peptide. Cancer Lett. 2008;271(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J. H., Sung B. H., Kim S. C.. Buforins: Histone H2A-Derived Antimicrobial Peptides from Toad Stomach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Biomembr. 2009;1788(8):1564–1569. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang A., Zheng X., Chen S., Duan G.. In Vitro Study of HPV18-Positive Cervical Cancer HeLa Cells Based on CRISPR/Cas13a System. Gene. 2024;921:148527. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2024.148527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drin G., Cottin S., Blanc E., Rees A. R., Temsamani J.. Studies on the Internalization Mechanism of Cationic Cell-Penetrating Peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(33):31192–31201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303938200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercauteren D., Vandenbroucke R. E., Jones A. T., Rejman J., Demeester J., De Smedt S. C., Sanders N. N., Braeckmans K.. The Use of Inhibitors to Study Endocytic Pathways of Gene Carriers: Optimization and Pitfalls. Mol. Ther. 2010;18(3):561–569. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adochitei A., Drochioiu G.. Rapid Characterization of Peptide Secondary Structure by FT-IR Spectroscopy. Rev. Roum. Chim. 2011;56:783–791. [Google Scholar]

- Sadat A., Joye I. J.. Peak Fitting Applied to Fourier Transform Infrared and Raman Spectroscopic Analysis of Proteins. Appl. Sci. 2020;10(17):5918. doi: 10.3390/app10175918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuril A. K., Vashi A., Subbappa P. K.. A Comprehensive Guide for Secondary Structure and Tertiary Structure Determination in Peptides and Proteins by Circular Dichroism Spectrometer. J. Pept. Sci. 2025;31(1):e3648. doi: 10.1002/psc.3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, A. I. Pharmacological Inhibition of Endocytic Pathways: Is It Specific Enough to Be Useful? Methods Mol. Biol.; Ivanov, A. I. , Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2008; Vol. 440, pp 15–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennick J. J., Johnston A. P. R., Parton R. G.. Key Principles and Methods for Studying the Endocytosis of Biological and Nanoparticle Therapeutics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021;16:266–276. doi: 10.1038/s41565-021-00858-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delenclos M., Trendafilova T., Mahesh D., Baine A. M., Moussaud S., Yan I. K., Patel T., McLean P. J.. Investigation of Endocytic Pathways for the Internalization of Exosome-Associated Oligomeric Alpha-Synuclein. Front. Neurosci. 2017;11:172. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S., Nguyen V., Coder D.. Assessment of Cell Viability. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 2013;64(1):9.2.1–9.2.26. doi: 10.1002/0471142956.cy0902s64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ted, A. ; Loomis, A. W. H. . Loomis’s Essentials of Toxicology, 4th ed.; Academic Press, Ed.; Elsevier: San Diego, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Gao X., Liu L., Guo S., Duan J., Xiao P.. Zebrafish as a Vertebrate Model for High-Throughput Drug Toxicity Screening: Mechanisms, Novel Techniques, and Future Perspectives. J. Pharm. Anal. 2025;15:101195. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2025.101195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero M. V., Candiracci M.. Zebrafish as Toxicological Model for Screening and Recapitulate Human Diseases. J. Unexplored Med. Data. 2018;3(2):4. doi: 10.20517/2572-8180.2017.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Harbawi M.. Toxicity Measurement of Imidazolium Ionic Liquids Using Acute Toxicity Test. Procedia Chem. 2014;9:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.proche.2014.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huertas Méndez N. D. J., Vargas Casanova Y., Gómez Chimbi A. K., Hernández E., Leal Castro A. L., Melo Diaz J. M., Rivera Monroy Z. J., García Castañeda J. E.. Synthetic Peptides Derived from Bovine Lactoferricin Exhibit Antimicrobial Activity against E. Coli ATCC 11775, S. Maltophilia ATCC 13636 and S. Enteritidis ATCC 13076. Molecules. 2017;22(3):452. doi: 10.3390/molecules22030452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaiss-Luna M. C., Jemioła-Rzemińska M., Strzałka K., Manrique-Moreno M.. Understanding the Biophysical Interaction of LTX-315 with Tumoral Model Membranes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24(1):581. doi: 10.3390/ijms24010581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M., Liu Q., Yao J. F., Wang Y. T., Ma Y. N., Xu H., Yu Q. Y., Li Z., Du S. S., Qi Y. K.. Synthesis and Structural Optimization of Oncolytic Peptide LTX-315. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2024;107:117760. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2024.117760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]