Abstract

Background

Castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) represents the terminal stage of prostate cancer (PCa), yet the molecular mechanisms driving its development remain unclear. Members of the histone lysine demethylase (KDM) family regulate histone methylation and thereby modulate transcriptional programs during malignant progression, contributing to PCa pathogenesis. While the function of KDM3B in PCa has been described, its involvement in CRPC remains uncertain. This study investigated the mechanistic role of KDM3B in CRPC progression.

Methods

Clinical specimens and publicly available datasets were analyzed to assess KDM3B expression in PCa and CRPC tissues. Cellular proliferation was evaluated through CCK-8 and colony formation assays. In addition, RT-PCR, WB, and CCK-8 assays were employed to elucidate the relationship between KDM3B activity and CRPC development.

Results

KDM3B expression was markedly reduced in both PCa and CRPC samples. Functional assays indicated that KDM3B suppressed the proliferative capacity of CRPC cells in vivo. Moreover, KDM3B upregulated PTEN expression, and its regulatory effect on CRPC cell proliferation was mediated through PTEN modulation.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that KDM3B suppresses CRPC cell proliferation by enhancing PTEN expression, highlighting its potential role as a tumor-suppressive factor in PCa.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40001-025-03371-z.

Keywords: KDM3B, PTEN, Prostate cancer (PCa), Castration-resistance PCa (CRPC), Cell proliferation

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) represents the most prevalent and the second lethal malignancy among men in the United States in 2024 [1]. Furthermore, the incidence of PCa in China is increasing rapidly with nearly 0.02% in 2022 [2]. It serious threatens the health of men worldwide. Therapeutic strategies for PCa include androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) [3], which remains the standard first-line approach capable of delaying disease progression [4]. Nevertheless, sustained ADT inevitably leads to relapse, with patients progressing to castration-resistant PCa (CRPC) [5]. However, there is no effective method for treating CRPC [6]. The underlying mechanisms driving CRPC remain insufficiently defined.

Genetic alterations together with epigenetic regulation critically influence PCa development [7–9]. Among epigenetic processes, post-translational modifications of histone N-terminal tails are central, with acetylation and methylation being the most extensively investigated. Histone methylation occurs at arginine and lysine residues, while lysine methylation on histones H3 and H4 governs a wide spectrum of biological functions [10–12]. These processes are dynamically controlled by histone lysine methyltransferases (KMTs) and histone lysine demethylases (KDMs) [13, 14]. Increasing evidence indicates that KDMs exert significant influence in various malignancies, including PCa [15].

The role of KDM3B in the occurrence of PCa has been reported [16]. However, the function of KDM3B and the mechanism how KDM3B can lead to the occurrence of CRPC is still unclear. In this study, we tried to find the function and mechanism of KDM3B in the occurrence of CRPC. We found that KDM3B was downregulated in both PCa and CRPC tissues. KDM3B can decrease CRPC cells proliferation in vivo. In CRPC cells, KDM3B can affect RKT pathway and then influence the expression of PTEN. We also found that the influence of KDM3B on CRPC cells proliferation though targeting PTEN. Our study has proven that KDM3B can suppress CRPC cells proliferation by targeting PTEN.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatic analysis

UALCAN (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html) was employed to assess KDM3B expression in PCa patients using transcriptomic data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). RNA-seq data of Chinese PCa patients were obtained from The Chinese Prostate Cancer Genome and Epigenome Atlas (CPGEA) (http://www.cpgea.com/). In parallel, the GSE21034 dataset from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) provided profiles from both PCa and normal tissues. Moreover, Gene Set Cancer Analysis (GSCA) (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/GSCA/) was applied to identify signaling pathways potentially involving KDM3B in CRPC.

Tissue samples

CRPC and adjacent non-tumor tissues were collected at Tongji Hospital under protocols approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital (SBKT-2024-103). All donors were informed of the experimental procedures and provided written consent prior to sample collection.

Cell culture

Prostate cell lines were obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The human prostate epithelial line RWPE-1 and PCa lines LNCaP, 22Rv1, C4-2, DU145, and PC-3 were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Catalog No. R8758, Sigma, Darmstadt, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Catalog No. 10091, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Cultures were incubated at 37 °C under 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. PCa cells were additionally maintained in androgen-deprived medium.

Cell transfection and lentivirus production

Transfections were carried out with Lipofectamine 2000 (Catalog No. 11668019, Thermo Fisher Scientific) or polyethyleneimine (PEI) (Catalog No. 408700, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturers’ protocols. HA-KDM3B plasmids were generated using KDM3B-pcDNA3.1 by Youze Biotechnology (Guangzhou, China), and shRNAs were also obtained from the same provider. For lentivirus production, 293 T cells were cotransfected with PSPAX2, PMD2.G, and the indicated shRNAs using PEI. Medium was replaced after 24 h, and viral supernatants were collected following an additional 48 h of culture. The collected medium was subsequently applied to 22Rv1 and DU145 cells. shRNA sequences are provided in Table S1.

Colony formation assay

At 48 h post-transfection, 22Rv1 and DU145 cells were harvested, resuspended, and plated into 6-well plates at a density of 500 cells/well for colony formation analysis. Cells were maintained in 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS (3 ml/well) under standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2). After a 2-week culture period, the medium was discarded and cells were rinsed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Catalog No. ST447, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Fixation was performed with carbinol for 30 min, followed by crystal violet staining for 20 min. Excess dye was removed by triple rinsing with distilled water, and plates were subsequently air-dried using a blower. Colonies consisting of more than 50 cells were quantified using ImageJ.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated with the CCK-8 kit (Catalog No. CA1210, Solarbio, Beijing, China). Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 3000 cells/well and cultured in 200 µL 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS for 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. At each time point, CCK-8 reagent was added according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and absorbance at 450 nm was determined with a multi-mode reader (LD942, Beijing, China).

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from tissue and cell specimens using TRIzol reagent (Catalog No. T9424, Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Complementary DNA was synthesized from the isolated RNA with the Advantage® RT-for-PCR Kit (Catalog No. 639505, Takara Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Japan). Quantitative analysis was performed on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Sequence Detection System with TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II reagents (Catalog No. RR420A, Takara Bio Inc.) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. β-Actin served as the internal reference. Relative RNA levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences for each target are provided in Table S2.

Antibodies

Rabbit monoclonal antibodies against KDM3B (Catalog No. ab70797) and PTEN (Catalog No. ab260011) were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Mouse monoclonal antibodies specific for AR (Catalog No. ab198394) and β-Actin (Catalog No. ab7871) were also acquired from Abcam. HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG and Goat Anti-Mouse IgG secondary antibodies (Catalog No. A0216/A0208) were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology.

Western blot

Total protein was extracted from tissue and cell line samples using RIPA lysis buffer. Protein lysates were mixed with Dual Color Protein Loading Buffer (Catalog No. NP0007, Thermo Fisher Scientific), separated on 7.5% SDS–PAGE gels, and subsequently transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Catalog No. 71078, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Membranes were blocked with Protein-Free Rapid Blocking Buffer and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against KDM3B (1:1000) and β-Actin (1:1000). After three washes with 1 × TBST (10 min each), membranes were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with the corresponding secondary antibody, followed by detection through X-ray exposure.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

KDM3B expression in clinical PCa specimens was examined by IHC. Tumor tissues were formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at a thickness of 4 µm. Antigen retrieval and immunostaining were conducted according to a standard protocol [16]. Sections were incubated with anti-KDM3B antibody (1:200). Evaluation of staining intensity was independently performed by two pathologists blinded to tissue information.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using data derived from no fewer than three independent experiments, with results expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Group comparisons were assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple groups, while two-group comparisons were evaluated by Student’s t-test. A P value < 0.05 was interpreted as statistically significant.

Results

KDM3B was downregulated in both PCa and CRPC tissues

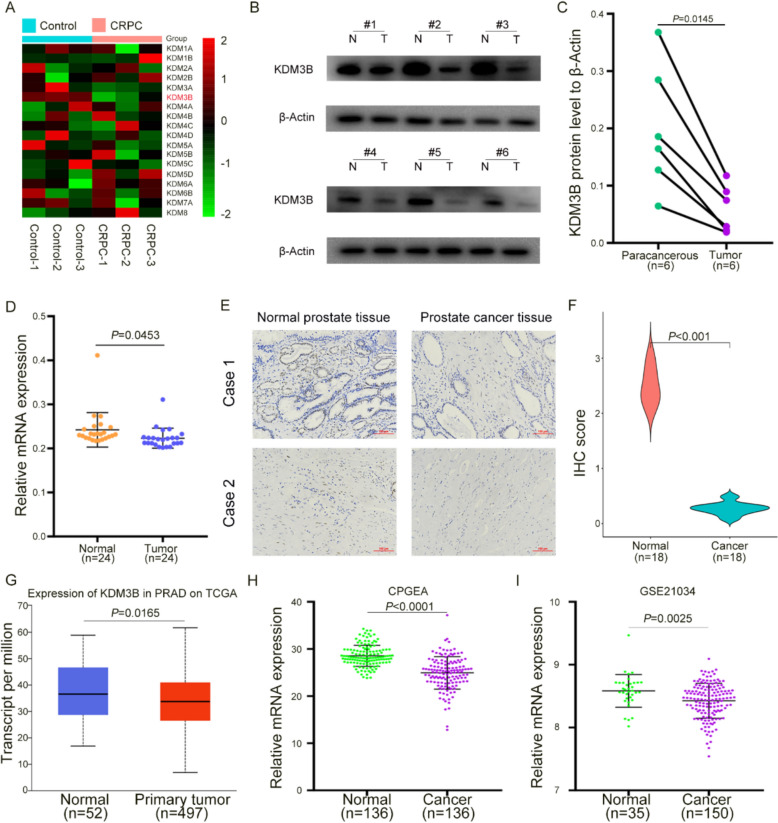

Given that multiple KDM family members have been implicated in PCa progression [17, 18], efforts were directed toward identifying candidates with potential relevance to PCa but limited prior investigation. Clinical CRPC specimens from Tongji Hospital were first analyzed, revealing that among eighteen KDMs, KDM3B exhibited marked downregulation in CRPC (Fig. 1A). Subsequent protein-level assessment further confirmed decreased KDM3B expression in CRPC tumor tissues (Fig. 1B, C). To strengthen this observation, 24 paired CRPC tumors and adjacent normal prostate tissues were examined, demonstrating significant reduction of KDM3B mRNA in CRPC (Fig. 1D). Consistent evidence was obtained from IHC analysis, which showed reduced KDM3B expression in PCa tissues with correspondingly lower IHC scores (Fig. 1E, F). Analysis of public datasets provided further validation. In the TCGA cohort, KDM3B levels were diminished in PCa compared with normal prostate tissues (Fig. 1G). Similarly, examination of Chinese PCa specimens revealed reduced KDM3B expression in tumor tissues (Fig. 1H). In addition, validation using the GEO dataset GSE21034 demonstrated lower KDM3B expression in PCa compared with normal counterparts (Fig. 1I). Collectively, multiple lines of evidence consistently indicated that KDM3B is downregulated in both PCa and CRPC tissues.

Fig. 1.

KDM3B was downregulated in both PCa and CRPC tissues. A Comparative analysis of eighteen KDMs in CRPC and normal prostate tissues. B, C Protein expression of KDM3B in CRPC tissues relative to adjacent normal counterparts. D mRNA expression of KDM3B in CRPC tissues compared with paired normal samples. E Representative IHC staining of KDM3B in CRPC and matched normal tissues. F Quantification of IHC scores for KDM3B in tumor and normal tissues. G Expression profile of KDM3B in PCa patients based on TCGA data analyzed through UALCAN. H KDM3B expression levels in PCa tissues of Chinese patients from the CPGEA database. I Expression of KDM3B in PCa versus normal prostate tissues based on the GSE21034 dataset. β-actin served as an internal control in qRT-PCR and western blot analyses. N, normal tissues; T, tumor tissues

KDM3B suppressed CRPC cells proliferation

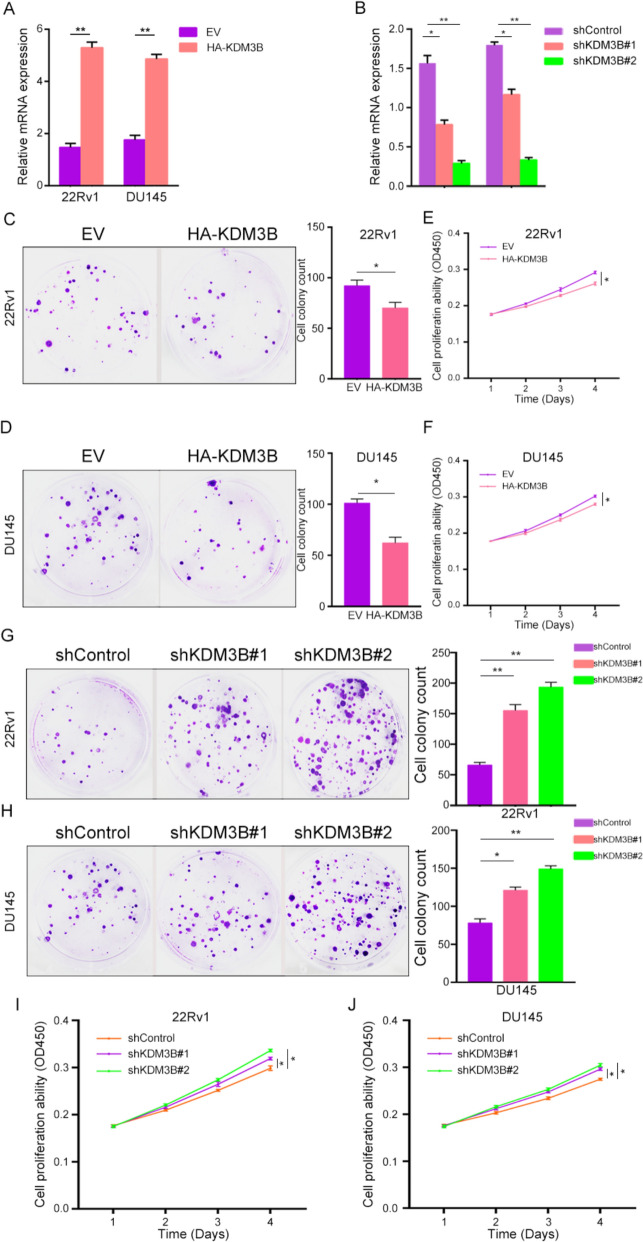

Given the observed downregulation of KDM3B in PCa and CRPC tissues, KDM3B was hypothesized to function as a tumor-suppressive factor. Previous studies have reported its inhibitory role in tumor cell proliferation [16, 19]. To examine whether KDM3B regulates proliferative capacity in CRPC cells, comparative analyses of KDM3B expression were conducted among prostate cell lines. KDM3B expression was markedly reduced in PCa cells relative to RWPE-1 (Figure S1A-B). On this basis, two CRPC-representative lines, 22Rv1 and DU145, which display relatively higher KDM3B expression and proliferate independently of androgen signaling [20] were selected for functional studies. Stable overexpression models were generated by transfecting HA-KDM3B plasmids, resulting in elevated KDM3B expression at transcript level. (Fig. 2A). We found the plasmids increased KDM3B 3 and 2.5 times in 22Rv1 cells and DU145 cells, respectively. KDM3B knockdown was achieved through shKDM3B lentiviral infection, leading to effective suppression of KDM3B expression in both cell lines (Fig. 2B). Cells transfected with shKDM3B#1 lentivirus would get half KDM3B expression and one third expression of KDM3B when transfected by shKDM3B#2 lentivirus, respectively. Then, Cell colony formation assays revealed that KDM3B overexpression significantly reduced clonogenic potential in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells (Fig. 2C, D). Consistent with this observation, CCK-8 assays demonstrated decreased proliferative activity upon HA-KDM3B transfection (Fig. 2E, F). Then, cytometry experiment was done to test the apoptosis ability changing after cells transfected with HA-KDM3B plasmids. We found with KDM3B overexpression, 22Rv1 cells apoptosis would increase (Figure S1C). Conversely, Functional assessment showed that KDM3B depletion enhanced colony formation (Fig. 2G, H), and CCK-8 assays further confirmed increased proliferative activity following knockdown (Fig. 2I, J).

Fig. 2.

KDM3B suppressed CRPC cells proliferation in vivo. A The mRNA expression of KDM3B following transfection with HA-KDM3B plasmids in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells. B Efficiency of KDM3B knockdown using shKDM3B lentivirus confirmed by qRT-PCR. C, D Colony formation assays of 22Rv1 and DU145 cells transfected with HA-EV or HA-KDM3B plasmids. E, F Proliferation of CRPC cells assessed after HA-EV or HA-KDM3B transfection. G, H Colony formation of CRPC cells transfected with shControl or shKDM3B lentivirus. I, J Proliferative activity of 22Rv1 and DU145 cells following shControl or shKDM3B transfection. β-actin was used as an internal control in qRT-PCR and western blot experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

KDM3B increased the expression of PTEN

Given the tumor-suppressive role of KDM3B in CRPC progression, the underlying mechanism was further investigated. Analysis using GSCA revealed that KDM3B was implicated in multiple pathways associated with PCa, with the AR signaling and RTK pathways being the most relevant (Fig. 3A). The AR pathway regulates androgen receptor (AR) expression, whereas the RTK pathway is linked to phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), a critical regulator of PCa development [21, 22]. Since 22Rv1 and DU145 cells retain the ability to proliferate under androgen-deprived conditions, KDM3B was hypothesized to exert a more substantial influence on PTEN expression. To test this assumption, 22Rv1 cells were transduced with shKDM3B lentivirus, and both AR and PTEN expression were assessed. The results indicated that suppression of KDM3B altered PTEN levels more prominently than AR (Fig. 3B). Subsequent experiments in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells confirmed that KDM3B upregulated PTEN protein expression to a greater extent than AR (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that the antitumor activity of KDM3B in CRPC is primarily mediated through the enhancement of PTEN expression.

Fig. 3.

KDM3B increased the expression of PTEN in CRPC cells. A Pathways associated with KDM3B involvement in PCa. B Relative mRNA levels of PTEN and AR following shKDM3B lentiviral transduction in 22Rv1 cells. C Protein levels of AR and PTEN after shKDM3B lentiviral transduction in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells. β-actin was used as an internal control for qRT-PCR and western blot analyses. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01

KDM3B suppressed CRPC cells proliferation by increasing the expression of PTEN

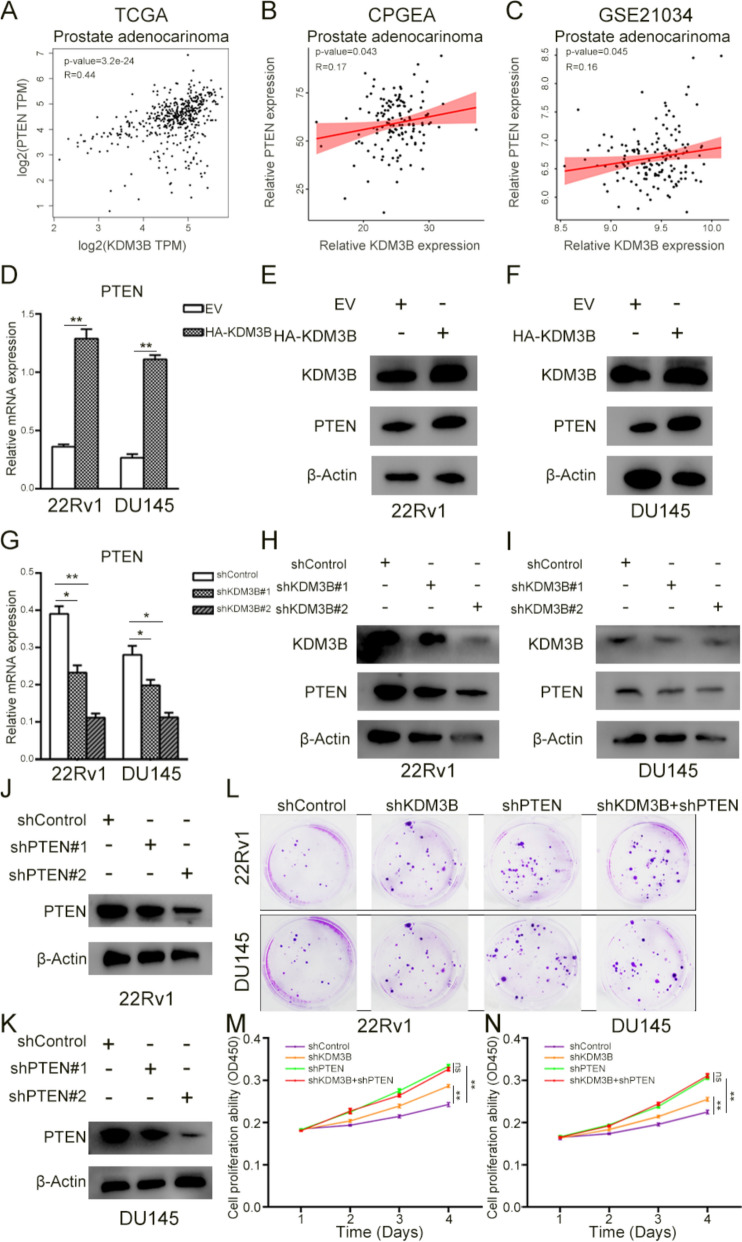

Given that KDM3B enhances PTEN expression, its inhibitory role in CRPC cell proliferation was hypothesized to be mediated by PTEN upregulation. Correlation analysis based on TCGA, CPGEA, and GSE21034 datasets demonstrated a positive association between KDM3B and PTEN (Fig. 4A–C). To validate this relationship, HA-KDM3B plasmids were introduced into 22Rv1 and DU145 cells, resulting in elevated PTEN mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 4D–F). Conversely, KDM3B silencing in both cell lines led to reduced PTEN expression (Fig. 4G–I), confirming that KDM3B positively regulates PTEN in CRPC cells. To determine whether KDM3B-mediated suppression of proliferation depends on PTEN, a PTEN knockdown (shPTEN) lentivirus was constructed. Transduction of CRPC cells with shPTEN markedly diminished PTEN expression (Fig. 4J, K), while KDM3B levels remained unaffected (Figure S1D–E). Combined transduction with shKDM3B and shPTEN in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells showed that PTEN depletion substantially reduced colony formation, and no difference was observed between shPTEN alone and the combined group (Fig. 4L, Figure S1F–G). Similar results were obtained in CCK-8 assays, where PTEN knockdown diminished proliferation, and the inhibitory effect of KDM3B overexpression was negated under conditions of PTEN loss (Fig. 4M, N). Collectively, the evidence indicates that KDM3B suppresses CRPC cell proliferation by enhancing PTEN expression.

Fig. 4.

KDM3B suppressed CRPC cells proliferation by targeting PTEN. A–C Correlation between KDM3B and PTEN mRNA expression in PCa patient cohorts derived from the TCGA database (A), CPGEA database (B), and GSE21034 dataset (C). D PTEN mRNA levels following HA-KDM3B plasmid transfection in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells. E, F PTEN protein expression after KDM3B overexpression in 22Rv1 (E) and DU145 (F) cells. G PTEN mRNA levels following shKDM3B transduction in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells. H, I PTEN protein expression after KDM3B knockdown in 22Rv1 (H) and DU145 (I) cells. J, K PTEN protein expression after shPTEN lentiviral transduction in CRPC cell lines. L Colony formation in PCa cells transduced with shControl, shKDM3B, shPTEN, or shKDM3B + shPTEN. M, N Proliferation capacity of 22Rv1 and DU145 cells transduced with shControl, shKDM3B, shPTEN, or shKDM3B + shPTEN. β-actin served as the internal control for qRT-PCR and western blot assays. ns, P > 0.05; * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01

Discussion

As the terminal stage of PCa, CRPC poses a severe threat to male health [6]. Once PCa progresses to CRPC, effective therapeutic strategies remain unavailable, and the underlying mechanisms governing its development are still not fully defined. Both genetic alterations and epigenetic modifications contribute substantially to PCa progression [7–9]. Genetic abnormalities also play an important role for CRPC. A study in 2012 has reported the landscape genetic change in CRPC and found AR, PTEN and FOXA1 playing an important role [23]. Among various epigenetic modifications, histone methylation—occurring on arginine and lysine residues of histone tails [24], —is of particular relevance, and its dynamic regulation is mediated by KMTs and KDMs [13, 14]. KDMs participated in lots of biological processes such as transcription, replication, and chromosome maintenance [25]. In addition, KDMs were also important for maintaining cell fate and genomic stability [26].

Histone methylation represents the covalent addition of methyl groups to lysine and arginine residues on histone tails [27]. Canonical lysine methylation sites include H3K4, H3K9, H3K27, H3K36, H3K56, H3K79, and H4K20 [10, 12]. Removal of these methyl marks, termed histone lysine demethylation, is catalyzed by KDMs [14]. Dysregulation of KDM activity has been implicated in tumorigenesis across multiple malignancies [15]. For example, KDM1A has reported important for liver, breast and lung cancers [28–30]. In addition, knockdown of KDM2B in glioblastoma cells reduced cells’ proliferation ability and caused DNA damage accumulation, implicating the central role of KDM2B in glioblastoma [31]. KDM3 profoundly changed the transcription of genes in Wnt/β-catenin pathway then enhancing self-renewal of colorectal cancer stem cells [32]. In addition, other KDMs also important for the progression of lots of cancers [33]. The role of KDMs in PCa has been reported, too. For instance, KDM4C enhances PCa cell proliferation through c-Myc upregulation [34], while KDM6B and KDM7A promote PCa initiation by increasing AR expression [35, 36]. Furthermore, a study also found a number of KDM family named KDM6A changed apparently in CRPC patients indicated the important role of KDM family in CRPC occurrence [23]. So, in the study, we further analyzed the role of KDM3B for CRPC.

In this study, the functional role and underlying mechanism of KDM3B in CRPC were systematically examined. We found that KDM3B was downregulated in both PCa and CRPC tissues (Fig. 1) and it suppressed CRPC cells proliferation in vivo (Fig. 2). In addition, overexpression of KDM3B would promote CRPC cells apoptosis (Figure S1C-D). This means that KDM3B inhibited the occurrence of CRPC. Next, we tried to search out the mechanism of KDM3B in suppressing CRPC. By pathway analysis and experiments, we got that KDM3B may influence the expression of PTEN which in RTK pathway (Fig. 3). Then, we found that KDM3B increased PTEN expression at transcriptional level (Fig. 4D–I). Finally, we proved that KDM3B suppressed CRPC cells proliferation by increasing PTEN expression (Fig. 4L–N).

Previous work has suggested a role for KDM3B in CRPC. In particular, one report showed that KDM3B influenced the growth of androgen-independent PCa cells [16], which consistent with the results we have found, proved the cancer inhibition ability of KDM3B. Whole transcriptome analysis in that study revealed an association between KDM3B and PCa, yet the mechanistic basis by which KDM3B contributed to disease development remained unresolved. In the present study, bioinformatic analyses identified PTEN as a key downstream target of KDM3B, implicating its regulatory function in CRPC initiation and progression.

PTEN, a tumor suppressor frequently deleted at chromosome 10q23, exhibits dysregulation across various malignancies, including those of the brain, ovary, breast, and prostate [37, 38]. By inhibiting AKT phosphorylation, PTEN suppresses activation of the PI3-K signaling cascade, thereby restraining uncontrolled cellular proliferation. Through this mechanism, PTEN exerts antitumor activity and impedes oncogenic transformation [39, 40]. The important role of PTEN in PCa has been widely reported. A study found that PTEN loss is widely occurred in Asian PCa patients [41]. PTEN deficiency is an important factor for PCa progression [40]. In addition, various of oncogenes caused PCa by influencing PTEN expression. KLF5 acetylation would promote PTEN deficiency and cause PCa progression [42]. TIMP1 deficiency would promote PCa development by influencing PTEN expression [43]. In this study, we found that KDM3B increased PTEN expression and then inhibiting CRPC development.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the current work addressed KDM3B function primarily in vivo, and additional in vitro experiments are required to substantiate its role. Second, the identification of potential downstream targets relied on bioinformatic prediction, which alone is insufficient for definitive conclusions. Third, though KDM3B had a lower an expression in PCa cells, its expression higher in 22Rv1 and DU145 cells than LNCaP PCa cells, which is sensitive to androgen. The result is different from the expression trend in tissues. We thought the difference results may came from the complexity of human tissues compared to simple cells. So, further study should be made to explain this phenomenon. Forth, due to the difficulty in collecting clinical CRPC, we only collected a small number of CRPC tissues for study. The smaller sample size lacks representativeness and is prone to causing bias. Finally, though we found that KDM3B increased PTEN therefore exercise an anti-cancer effect, other targets may also exist. So, the searching for downstream target genes in this way is inadequate. More detailed studies will need to be conducted to validate our findings in the future.

Conclusion

In conclusion, KDM3B expression is reduced in CRPC tissues, and its upregulation suppresses CRPC cell proliferation through enhancement of PTEN expression. These results indicate that KDM3B represents a promising therapeutic target for CRPC.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary material 1. (A–B) KDM3B expression at mRNA and protein levels across prostate cell lines. (C) Cell apoptosis of 22Rv1 after transfected with HA-EV or HA-KDM3B plasmids, respectively. (D–E) KDM3B protein expression after shKDM3B lentiviral transduction in 22Rv1 (D) and DU145 (E) cells. (F–G) Colony formation capacity of 22Rv1 (F) and DU145 (G) cells following transduction with shControl or shKDM3B lentivirus. β-actin served as an internal reference in qRT-PCR and western blot assays. Statistical significance was defined as ns for P > 0.05, * for P < 0.05, and ** for P < 0.01

Acknowledgements

We thank Bullet Edits Limited for the linguistic editing and proofreading of the manuscript.

Author contributions

PFZ and YTW designed the study, finished cell experiments and analyzed the data. YFL and XC collected the clinical samples and finished tissue experiments. JJM analyzed the data form public databases. LMP and YTW revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82403182).

Data availability

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the public databases such as TCGA and CPGEA. Other data can get from the correspondence author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethic committee of Tongji Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University (SBKT-2024–103). Each participate volunteered to join and signed the informed consent form. The study conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to publish this article. All patients understood the purpose of the study, voluntarily provided specimens and consented to the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Giaquinto AN, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(1):12–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sur S, Steele R, Shi X, Ray RB. miRNA-29b inhibits prostate tumor growth and induces apoptosis by increasing Bim expression. Cells. 2019. 10.3390/cells8111455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross RW, Xie W, Regan MM, Pomerantz M, Nakabayashi M, Daskivich TJ, et al. Efficacy of androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in patients with advanced prostate cancer: association between Gleason score, prostate-specific antigen level, and prior ADT exposure with duration of ADT effect. Cancer. 2008;112(6):1247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part II: Recent changes in prostate cancer trends and disease characteristics. Cancer. 2019;125(2):317–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Joniau S, van der Kwast T, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2014;65(2):467–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nowacka-Zawisza M, Wisnik E. DNA methylation and histone modifications as epigenetic regulation in prostate cancer (review). Oncol Rep. 2017;38(5):2587–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perdana NR, Mochtar CA, Umbas R, Hamid AR. The risk factors of Prostate cancer and its prevention: a literature review. Acta Med Indones. 2016;48(3):228–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Yan L, Yao W, Chen K, Xu H, Ye Z. Integrated analysis of genetic abnormalities of the histone lysine methyltransferases in prostate cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:193–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JE, Wang C, Xu S, Cho YW, Wang L, Feng X, et al. H3k4 mono- and di-methyltransferase MLL4 is required for enhancer activation during cell differentiation. Elife. 2013;2:e01503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sze CC, Cao K, Collings CK, Marshall SA, Rendleman EJ, Ozark PA, et al. Histone H3K4 methylation-dependent and -independent functions of Set1A/COMPASS in embryonic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2017;31(17):1732–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C, Lee JE, Lai B, Macfarlan TS, Xu S, Zhuang L, et al. Enhancer priming by H3K4 methyltransferase MLL4 controls cell fate transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(42):11871–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Husmann D, Gozani O. Histone lysine methyltransferases in biology and disease. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2019;26(10):880–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen H, Xu W, Lan F. Histone lysine demethylases in mammalian embryonic development. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49(4):e325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterling J, Menezes SV, Abbassi RH, Munoz L. Histone lysine demethylases and their functions in cancer. Int J Cancer. 2020. 10.1002/ijc.33375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarac H, Morova T, Pires E, McCullagh J, Kaplan A, Cingoz A, et al. Systematic characterization of chromatin modifying enzymes identifies KDM3B as a critical regulator in castration resistant prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2020;39(10):2187–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Metzler VM, de Brot S, Haigh DB, Woodcock CL, Lothion-Roy J, Harris AE, et al. The KDM5B and KDM1A lysine demethylases cooperate in regulating androgen receptor expression and signalling in prostate cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1116424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duan L, Chen YA, Liang Y, Chen Z, Lu J, Fang Y, et al. Therapeutic targeting of histone lysine demethylase KDM4B blocks the growth of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;158:114077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.An MJ, Kim DH, Kim CH, Kim M, Rhee S, Seo SB, et al. Histone demethylase KDM3B regulates the transcriptional network of cell-cycle genes in hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;508(2):576–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu X, Gong S, Roy-Burman P, Lee P, Culig Z. Current mouse and cell models in prostate cancer research. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20(4):R155-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haddadi N, Lin Y, Travis G, Simpson AM, Nassif NT, McGowan EM. PTEN/PTENP1: “regulating the regulator of RTK-dependent PI3K/Akt signalling”, new targets for cancer therapy. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strainic MG, Pohlmann E, Valley CC, Sammeta A, Hussain W, Lidke DS, et al. RTK signaling requires C3ar1/C5ar1 and IL-6R joint signaling to repress dominant PTEN, SOCS1/3 and PHLPP restraint. FASEB J. 2020;34(2):2105–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grasso CS, Wu YM, Robinson DR, Cao X, Dhanasekaran SM, Khan AP, et al. The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7406):239–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Migliori V, Muller J, Phalke S, Low D, Bezzi M, Mok WC, et al. Symmetric dimethylation of H3R2 is a newly identified histone mark that supports euchromatin maintenance. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(2):136–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Black JC, Van Rechem C, Whetstine JR. Histone lysine methylation dynamics: establishment, regulation, and biological impact. Mol Cell. 2012;48(4):491–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi Y, Lan F, Matson C, Mulligan P, Whetstine JR, Cole PA, et al. Histone demethylation mediated by the nuclear amine oxidase homolog LSD1. Cell. 2004;119(7):941–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouchard C, Sahu P, Meixner M, Notzold RR, Rust MB, Kremmer E, et al. Genomic location of PRMT6-dependent H3R2 methylation is linked to the transcriptional outcome of associated genes. Cell Rep. 2018;24(12):3339–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao C, Vasilatos SN, Bhargava R, Fine JL, Oesterreich S, Davidson NE, et al. Functional interaction of histone deacetylase 5 (HDAC5) and lysine-specific demethylase 1 (LSD1) promotes breast cancer progression. Oncogene. 2017;36(1):133–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayami S, Kelly JD, Cho HS, Yoshimatsu M, Unoki M, Tsunoda T, et al. Overexpression of LSD1 contributes to human carcinogenesis through chromatin regulation in various cancers. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(3):574–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Augert A, Eastwood E, Ibrahim AH, Wu N, Grunblatt E, Basom R, et al. Targeting notch activation in small cell lung cancer through LSD1 inhibition. Sci Signal. 2019. 10.1126/scisignal.aau2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Staberg M, Rasmussen RD, Michaelsen SR, Pedersen H, Jensen KE, Villingshoj M, et al. Targeting glioma stem-like cell survival and chemoresistance through inhibition of lysine-specific histone demethylase KDM2B. Mol Oncol. 2018;12(3):406–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li J, Yu B, Deng P, Cheng Y, Yu Y, Kevork K, et al. KDM3 epigenetically controls tumorigenic potentials of human colorectal cancer stem cells through Wnt/beta-catenin signalling. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sterling J, Menezes SV, Abbassi RH, Munoz L. Histone lysine demethylases and their functions in cancer. Int J Cancer. 2021;148(10):2375–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin CY, Wang BJ, Chen BC, Tseng JC, Jiang SS, Tsai KK, et al. Histone demethylase KDM4C stimulates the proliferation of prostate cancer cells via activation of AKT and c-Myc. Cancers. 2019. 10.3390/cancers11111785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee KH, Hong S, Kang M, Jeong CW, Ku JH, Kim HH, et al. Histone demethylase KDM7A controls androgen receptor activity and tumor growth in prostate cancer. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(11):2849–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cao Z, Shi X, Tian F, Fang Y, Wu JB, Mrdenovic S, et al. KDM6B is an androgen regulated gene and plays oncogenic roles by demethylating H3K27me3 at cyclin D1 promoter in prostate cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, Podsypanina K, Bose S, Wang SI, et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275(5308):1943–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steck PA, Pershouse MA, Jasser SA, Yung WK, Lin H, Ligon AH, et al. Identification of a candidate tumour suppressor gene, MMAC1, at chromosome 10q23.3 that is mutated in multiple advanced cancers. Nat Genet. 1997;15(4):356–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stambolic V, Suzuki A, de la Pompa JL, Brothers GM, Mirtsos C, Sasaki T, et al. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell. 1998;95(1):29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wise HM, Hermida MA, Leslie NR. Prostate cancer, PI3K, PTEN and prognosis. Clin Sci. 2017;131(3):197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu Y, Mo M, Wei Y, Wu J, Pan J, Freedland SJ, et al. Epidemiology and genomics of prostate cancer in Asian men. Nat Rev Urol. 2021;18(5):282–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang B, Liu M, Mai F, Li X, Wang W, Huang Q, et al. Interruption of KLF5 acetylation promotes PTEN-deficient prostate cancer progression by reprogramming cancer-associated fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 2024. 10.1172/JCI175949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guccini I, Revandkar A, D’Ambrosio M, Colucci M, Pasquini E, Mosole S, et al. Senescence reprogramming by TIMP1 deficiency promotes prostate cancer metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(1):68–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1. (A–B) KDM3B expression at mRNA and protein levels across prostate cell lines. (C) Cell apoptosis of 22Rv1 after transfected with HA-EV or HA-KDM3B plasmids, respectively. (D–E) KDM3B protein expression after shKDM3B lentiviral transduction in 22Rv1 (D) and DU145 (E) cells. (F–G) Colony formation capacity of 22Rv1 (F) and DU145 (G) cells following transduction with shControl or shKDM3B lentivirus. β-actin served as an internal reference in qRT-PCR and western blot assays. Statistical significance was defined as ns for P > 0.05, * for P < 0.05, and ** for P < 0.01

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the public databases such as TCGA and CPGEA. Other data can get from the correspondence author.