Abstract

Purpose

Exercise is the primary choice for managing age-related sarcopenia. However, many exercise intervention subtypes are currently used to manage age-related sarcopenia with little published evidence comparing their efficacy, meaning the optimal exercise intervention subtype for sarcopenia remains unclear. We performed a Bayesian network meta-analysis addressing these uncertainties.

Methods

We searched eight databases for literature through to 5 June 2023 to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of exercise interventions for age-related sarcopenia. Skeletal muscle mass index (SMI), handgrip strength (HGS), knee extension strength (KES), gait speed (GS), chair rise test (CST) and time up and go test (TUGT) were used as outcomes. Effect estimates were expressed as standardized mean differences with 95% confidence intervals. We performed a Bayesian network meta-analysis using a random effects model and the R package gemtc to compare the relative efficacy of various exercise intervention subtypes. We also used surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) to estimate relative treatment rankings. This systematic review is registered in PROSPERO, CRD42023474627.

Results

We included 37 RCTs with a total of 2322 subjects and 10 unique exercise intervention subtypes. Most RCTs (72.9%) displayed unclear risk of bias. According to the value of SUCRA, whole-body vibration high frequency (WBVH) ranked first in SMI (99.8%), HGS (96.5%) and GS (76.5%), suggesting it is the most comprehensive and effective exercise intervention subtype for managing age-related sarcopenia. Combined training (CT) ranked first in CST (76.5%) and TUGT (75.2%), suggesting it is the most effective exercise intervention subtype for improving muscle function. Resistance training (RT) ranked first in KES (99.3%) and also performed well on TUGT and HGS.

Conclusion

Our network meta-analysis revealed that certain exercise intervention subtypes are more effective for specific muscle-related outcomes. WBHV, CT and RT are the most promising exercise intervention subtypes for managing sarcopenia, with WBHV providing the most comprehensive improvement in sarcopenia, CT the best improvement in muscle function, and RT the most common exercise intervention subtype for sarcopenia, which remains quite effective in enhancing muscle strength and function. Our meta-analysis provides a valuable reference and guidance for clinicians, researchers and policy makers, but it is limited by the heterogeneity and quality of the included RCTs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12877-025-06529-w.

Keywords: Sarcopenia, Exercise intervention, Network meta-analysis, Systematic review

Introduction

Sarcopenia, characterized by gradual and widespread degeneration of skeletal muscle mass and function [1], affects 5% to 13% of adults aged 60–70 years and 11% to 50% of those aged 80 years or older [2]. The condition is an age-associated deterioration of skeletal muscle [1], and is chronic with a progressive natural history [1, 3, 4]. Costs to the healthcare and social welfare systems are substantial [5–7], and the impact of symptoms on quality of life is significant [8, 9], as it reduces patients’ ability to perform daily tasks [9, 10], impairs their mobility, increases the risk of falls and fractures [8, 11], and consequently reduces patients’ independence [12], leading to social isolation [11, 13], depression [14], and reduced social participation [12, 13, 15]. However, no medications have been approved for the treatment of sarcopenia [1], the effectiveness of most medications is modest [16], and side effects are significant [16, 17]. Even novel, more selective targeted therapies developed in the last decade have failed to demonstrate consistent efficacy in larger clinical trials [18, 19]. As a result, they are often withdrawn or restricted [16], pharmacological treatments are not widely available or accessible for sarcopenia patients [20].

Therefore, patients may turn to other approaches. Exercise therapy has emerged as a direct, effective and non-invasive approach for treating sarcopenia, and is mostly recommended by clinical practice guidelines as the primary treatment for sarcopenia [1, 21], to improve muscle strength [2, 22, 23], function [24–26], and mass [27–29], as well as reduce the risk of adverse outcomes [21, 30]. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that although the exploration of exercise interventions for sarcopenia has become increasingly prevalent and researchers have proposed an array of exercise intervention methods for sarcopenia [2, 22–26], including resistance training [31, 32], aerobic exercise [33, 34], combined resistance [35, 36] and comprehensive training [37, 38], the optimal subtype of exercise for sarcopenia remains unclear. Hence, it is imperative to undertake systematic evaluations and comparisons of the effects of varying exercise intervention approaches on individuals affected by sarcopenia in order to furnish evidence-based guidance for clinical decision-making.

To date, limitations of the current evidence base for exercise interventions in age-related sarcopenia include the fact that, although the impact of exercise on age-related sarcopenia symptoms has been examined in some randomised controlled trials (RCTs), relatively scarce RCTs have directly compared different exercise sub-types in terms of their effects, and most of the previous systematic reviews have used conventional meta-analyses that rely on direct evidence from studies comparing two interventions simultaneously [39–42]. This restriction constrains the ability to effectively compare and analyze interventions, thereby complicating decision-making in the realm of multi-interventional research. Consequently, the appraisal of multiple intervention strategies or the comparison of different intervention strategies becomes a difficult task. Network meta-analysis (NMA) is a novel approach to compare multiple interventions simultaneously using direct and indirect evidence from RCTs [43]. Compared with standard paired analyses, the results of NMAs usually give more precise estimates and can rank interventions to inform clinical decision-making [44].

Thus, we conducted a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis to estimate the efficacy of exercise interventions for age-related sarcopenia as well as the relative efficacy of different subtypes of exercise interventions for various outcome indicators of age-related sarcopenia. NMA allows indirect, as well as direct, comparisons to be made across different RCTs, increasing the number of participants’ data available for analysis, an advantage over published conventional pairwise meta-analyses [43, 44]. Importantly, it also allows a credible ranking system of the efficacy of different comparators to be developed, even in the absence of trials making direct comparisons [45]. We used systematic review methodology to synthesise the results of several high-quality studies, this may assist in developing a more robust design for future RCTs of age-related sarcopenia exercise therapy. It also allows for accurate exercise intervention recommendations for patients with sarcopenia and provides evidence-based support for the development of exercise prescriptions and health management policies for those affected by sarcopenia.

Methods

Our study followed the reporting guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), specifically the Network Meta-Analyses extended statement (PRISMA-NMA) [46], registered as CRD42023474627 in PROSPERO.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched PubMed, CNKI, Embase, Web of Science, VIP, SinoMed and Airiti Library and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials databases from their inception to June 2023. In addition, we searched clinicaltrials.gov and the reference lists of relevant reviews and articles for additional data or eligible RCTs. Finally, we used bibliographies of all obtained articles to perform a recursive search.

RCTs examining the effect of exercise interventions on patients over 60 years of age with sarcopenia, as defined by clinical opinion or specific criteria such as the EWGSOP criteria [47], were selected. We used the following PICOS principles to define the eligible studies: [48]: 1) Population: patients aged over 60 years with sarcopenia; 2) Intervention: any type of exercise intervention; 3) Comparison: non-pharmacological interventions including, but not limited to, usual care, health education or cognitive behavioural therapy; 4) Outcome: skeletal muscle mass index (SMI), handgrip strength (HGS), knee extension strength (KES), gait speed (GS), chair rise test (CST) and timed up and go test (TUGT); 5) Study design: RCTs. The studies were excluded : 1) not full-text; 2) not a randomized controlled trial (RCT); 3) systematic reviews or meta-analysis; 4) subjects were not diagnosed with sarcopenia previously in the exercise group and control group; 5) the exercise group did not receive pure exercise intervention (such as a combination of exercise and nutrition); and 6) the study presented no extractable data.

Two investigators (Wei and He) independently conducted the literature search. We identified studies on sarcopenia using the following terms: sarcopenia or muscle atrophy (both as medical subject heading and free text terms), or myosarcopenia, myopenia, muscle loss, muscle wasting, muscle weakness, or dynapenia (as free text terms). We combined these using the set operator AND with studies identified with the terms: exercise, physical activity, resistance training, aerobic training, balance training, or tai chi (as free text terms). We used Boolean operators, truncation, wildcards, and filters to refine our search strategy for each database. We imposed no restrictions on the language of the studies. We provide the full search strings for PubMed in Appendix 1.

Outcome assessment

We used six muscle-related outcomes to assess the efficacy of exercise interventions for sarcopenia, including SMI (kg/m2), HGS (kg), KES (kg), GS (m/s), CST (s) and TUGT (s). These outcomes reflect the components of sarcopenia, namely muscle mass, strength, and function, and are commonly used in clinical practice and research. We used the absolute change from baseline to post-intervention for each outcome, and we imputed missing data or outliers using the mean or median values of the corresponding groups.

Data extraction

Two investigators (Wang and Meng) independently extracted the following information from the included studies using a standardized data extraction form: 1) basic information about the article, including title, year of publication and authors; 2) characteristics of the study, including participant demographic characteristics (sex ratio, mean age), diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia, sample size, details of the intervention (period of the intervention, content of the intervention), and main outcome indicators; 3) information for risk of bias assessment, including randomisation method, use of blinding and data completeness. We contacted the authors of the original studies for additional data or clarification, if needed. We resolved disagreements between investigators (Wang and Meng) by discussion, otherwise a third reviewer was consulted.

Risk-of-bias assessment

Two researchers (Wei and He) performed an independent risk of bias assessment of the retrieved studies to determine eligibility. We assessed all potentially relevant studies using the revised cochrane’s risk of bias tool [49]. The assessment covered six domains: random allocation methods, allocation scheme concealment, blinding, outcome data completeness and selective reporting of findings and other sources of bias. We rated each domain as low, high or unclear risk of bias, and provided the rationale and the supporting evidence for each rating. We resolved disagreements between investigators (Wei and He) by discussion, otherwise a third reviewer was consulted. We summarized the results of the risk of bias assessment in a table and a graph, and explained how they affected the quality and credibility of the evidence, and explained how they affected the quality and credibility of the evidence.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

We performed a network meta-analysis using the Bayesian model, with the statistical package “gemtc” (version 0.8–5.8) and “netmeta” (version 0.9–7.9) in R (version 4.1.0). We chose the Bayesian model over the frequentist model for network meta-analysis because it allows us to incorporate prior information and uncertainty, and to obtain posterior distributions and probabilities for each pairwise comparison in the network [50]. We reported the results according to the PRISMA-NMA guidelines [46].

For the network plots and the comparison-adjusted funnel plots, we used Stata version 16 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) generated as follows: 1) network plots were generated to test the symmetry and geometry of the evidence. We used the “network setup mean sd n, study(id) trt(t) format(augment)” command to converts the data from a long format to a wide format and the “netplot” command to generate weighted network plots. In our weighted network plots, each node represents an intervention and each edge represents a direct comparison between two interventions, with node size corresponding to the number of participants and edge width corresponding to the number of studies. 2) comparison-adjusted funnel plots were generated to explore the presence of publication bias or other small-study effects in our study. We used the “network convert pairs” command to transforms the data format from arm-based to study-based and the “netfunnel” command to produce comparison-adjusted funnel plots. Our comparison-adjusted funnel plots are scatter plots of effect size versus precision, with the precision of each comparison in the network measured by the inverse of the standard error, and symmetry around the effect estimate line indicating the absence of publication bias or small study effects. We also added comparison-specific colors to the studies, and fitted a regression line to the funnel plot, which can help to detect and quantify the asymmetry of the plot.

For the network meta-analysis, we run Markov-Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) by calling “JAGS” via “gemtc”, which uses a log-link function and a divergence likelihood method to fit a generalised linear model containing four Markov chains with 10,000 burn-ins and 50,000 iterations each, with a thinning interval of 10 for each outcome. We assessed the convergence of the chains using the Gelman-Rubin diagnostic and the Brooks-Gelman-Rubin plots. We used SMD and 95% credible intervals (CI) to compare the effects of different exercise intervention subtypes on each outcome, based on the absolute change from baseline to post-intervention [51]. We used a random effects model to account for the heterogeneity of the included studies, and we assessed the heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, where I2

50% indicated low heterogeneity and I2 > 50% indicated high heterogeneity. We explored the sources of heterogeneity using descriptive analyses.

50% indicated low heterogeneity and I2 > 50% indicated high heterogeneity. We explored the sources of heterogeneity using descriptive analyses.

Additionally, we analysed the consistency between direct comparisons and network outcome through node splitting. We used the nodesplit function from the gemtc package to perform the node-splitting analysis, which compares the direct and indirect estimates for each comparison in the network and tests their agreement using a Z-test [43]. We reported the P-values for each node-splitting test and considered a P-value less than 0.05 as indicative of inconsistency. And to visualise the drivers of network estimation, possible sources for inconsistency, and possible disturbed network estimates, we also generated net heat plots for each outcome. We used the netheat function from the “netmeta” package to generate the net heat plot, which is a matrix plot that shows the contribution of each direct comparison to each indirect comparison, and the color of each cell indicates the degree of inconsistency.

Finally, in order to determine the efficacy of different types of exercise interventions, we calculated the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) for different exercise interventions within each outcome using the “sucra functions” from the “gemtc” package, and visualized the SUCRA plots using the plot function from the same package. SUCRA is a metric that summarizes the ranking probabilities of each intervention subtype in a network meta-analysis, based on the area under the cumulative ranking curve. SUCRA values range from 0% to 100%, with higher values indicating higher probabilities of being the best intervention subtype. SUCRA can provide a simple and intuitive way to compare and rank the interventions in a network meta-analysis, especially when there are many interventions and outcomes to consider [52]. We used SUCRA to complement the numerical and graphical results of the network meta-analysis, and to provide a summary of the overall ranking and hierarchy of the interventions for each outcome.

Results

Study selection

A total of 3552 citations were acquired, with 3543 citations generated from the search strategy and an additional 9 citations obtained through manual search. After duplicates of 896 articles were deleted, 2579 articles were excluded by title and abstract screening, mainly due to irrelevant population, intervention or outcome. The full texts of the remaining 77 articles were assessed for eligibility according to the inclusion-exclusion criteria, leaving 37 articles eligible for the present review. The process of study selection is shown as a PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for studies selection according to the PRISMA statement

Study characteristics

A total of 37 eligible RCTs were included, published between 2010 and 2023, involving 2322 patients and 10 exercise intervention subtypes, as follows: resistance training (RT) [28, 31, 32, 53–61]; aerobic training (AT) [28, 33, 34, 61–63]; resistance and aerobic training (RAT) [28, 35, 36, 60, 61, 64–73]; comprehensive training (CT) [37, 38, 63, 74, 75]; whole body vibration training - low frequency (WBVL) [33, 76–78]; whole body vibration training - medium frequency (WBVM) [76, 78]; whole body vibration training - high frequency (WBVH) [76, 78]; self-managed training (SM) [79, 80]; respiratory muscle training (RMT) [54]; balance training (BT) [56]. The control groups consisted of health education, psychological intervention or routine care.

All trials were published in full, of these, 3 were four-armed trials [28, 61, 76], 5 were three-armed [54, 60, 62, 78, 80], and the rest were two-armed. The duration of the interventions ranged from 8 to 36 weeks, the sample sizes in the exercise intervention groups ranged from 7 to 123, and the mean age of the subjects ranged from 60.4 ± 2.7 to 89.5 ± 4.4. For the relevant outcome measures, among them, 15 listed SMI outcomes [33, 56, 57, 60, 66–69, 71–73, 78, 79, 81], 27 listed HGS outcomes [28, 31–35, 37, 38, 53, 54, 56–62, 65, 69–71, 73, 75, 78, 79, 81], 6 listed KES outcomes [28, 33, 58, 61, 67, 72], 8 provided CST results [31–33, 35, 59, 76, 77, 80], 19 provided GS results [33, 35, 37, 38, 54, 55, 58, 63, 64, 67, 72–80], and 12 provided TUGT results [31, 35, 58, 59, 64, 70–72, 75–77, 80]. The basic characteristics and more details of individual RCTs are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of randomised controlled trials of exercise interventions for age-related sarcopenia

| Study | Country | Sample size | Sex ratio (female/male) | Age ± SD (years) | Intervention | Duration | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chen et al. (2018) [53] | China | 15 | 15/0 | 66.7 ± 5.3 | RT | 8W | HGS |

| 18 | 18/0 | 68.3 ± 2.8 | CG | ||||

| Cebriá et al. (2018) [54] | Spain | 11 | 9/2 | 82.6 ± 9.1 | RT | 12W | HGS, GS |

| 9 | 5/4 | 87.1 ± 3.8 | RMT | ||||

| 17 | 12/5 | 81.2 ± 5.4 | CG | ||||

| Chen et al. (2017) [28] | China | 15 | 14/1 | 69.3 ± 3.0 | AT | 8W | HGS, KES |

| 15 | 12/3 | 68.6 ± 3.1 | RT | ||||

| 15 | 14/1 | 68.5 ± 2.7 | RAT | ||||

| 15 | 14/1 | 68.6 ± 3.1 | CG | ||||

| Liao et al. (2018) [64] | China | 29 | 29/0 | 66.6 ± 4.5 | RAT | 12W | GS, TUGT |

| 18 | 18/0 | 68.3 ± 6.0 | CG | ||||

| Maruya et al. (2015) [79] | Japan | 34 | 19/15 | 69.2 ± 5.6 | SM | 24W | SMI, HGS, GS |

| 18 | 10/8 | 68.5 ± 6.2 | CG | ||||

| Park et al. (2017) [65] | Korea | 25 | 25/0 | 74.7 ± 5.1 | RAT | 24W | HGS |

| 25 | 25/0 | 73.5 ± 7.1 | CG | ||||

| Tsekoura et al. (2018) [80] | Greece | 18 | 16/2 | 74.5 ± 6.0 | CT | 12W | SMI, HGS, CST, GS, TUGT |

| 18 | 15/3 | 71.1 ± 6.4 | SM | ||||

| 18 | 16/2 | 72.8 ± 8.3 | CG | ||||

| Vasconcelos et al. (2016) [55] | Brazil | 14 | 14/0 | 72.0 ± 4.6 | RT | 10W | GS |

| 14 | 14/0 | 72.0 ± 3.6 | CG | ||||

| Huang et al. (2017) [66] | China | 18 | 18/0 | 68.8 ± 4.9 | RAT | 12W | SMI |

| 17 | 17/0 | 69.5 ± 5.0 | CG | ||||

| Piastra et al. (2018) [56] | Italy | 35 | 35/0 | 69.9 ± 2.7 | RT | 36W | SMI, HGS |

| 37 | 37/0 | 70.0 ± 2.8 | BT | ||||

| Lu et al. (2019) [67] | Singaporean | 78 | 53/25 | 69.7 ± 4.3 | RAT | 24W | SMI, KES, GS |

| 14 | 6/8 | 71.0 ± 6.6 | CG | ||||

| Zhu LY et al. (2019) [62] | China | 29 | 20/9 | 74.5 ± 7.1 | AT | 12W | SMI, HGS, KES, CST, GS |

| 19 | 14/5 | 72.2 ± 6.6 | CG | ||||

| Vikberg et al. (2019) [31] | Switzerland | 31 | 18/13 | 70.0 ± 0.2 | RT | 10W | HGS, CST, TUGT |

| 34 | 19/15 | 70.9 ± 0.2 | CG | ||||

| Jung et al. (2018) [68] | Korea | 13 | 13/0 | 75.0 ± 3.9 | RAT | 12W | SMI |

| 13 | 13/0 | 74.9 ± 5.2 | CG | ||||

| Yamada et al. (2019) [32] | Japan | 28 | 18/10 | 84.7 ± 5.1 | RT | 12W | HGS, CST |

| 28 | 15/13 | 83.9 ± 5.7 | CG | ||||

| Li et al. (2021) [36] | China | 37 | 23/14 | 73.7 ± 5.6 | RAT | 12W | SMI, HGS |

| 33 | 21/12 | 72.9 ± 6.2 | CG | ||||

| Zhu Yq et al. (2019) [33] | China | 24 | 0/24 | 88.8 ± 3.7 | AT | 8W | HGS |

| 28 | 0/28 | 89.5 ± 4.4 | WBVL | ||||

| 27 | 0/27 | 87.5 ± 3.0 | CG | ||||

| Makizako et al. (2020) [35] | Japan | 36 | 25/11 | 75.8 ± 7.3 | RAT | 12W | HGS, CST, GS, TUGT |

| 36 | 26/10 | 79.6 ± 7.3 | CG | ||||

| Chiu et al. (2018) [57] | China | 36 | 14/22 | 79.6 ± 7.3 | RT | 12W | SMI, HGS |

| 34 | 21/13 | 80.1 ± 8.2 | CG | ||||

| Liao et al. (2017) [58] | China | 21 | 0/21 | 66.3 ± 4.4 | RT | 24W | HGS, KES, GS, TUGT |

| 25 | 0/25 | 68.4 ± 5.8 | CG | ||||

| Wei et al. (2017) [76] | China | 17 | 11/6 | 78.0 ± 4.0 | WBVL | 12W | CST, GS, TUGT |

| 17 | 11/6 | 75.0 ± 6.0 | WBVM | ||||

| 18 | 13/5 | 74.0 ± 5.0 | WBVH | ||||

| 18 | 13/5 | 76.0 ± 6.0 | CG | ||||

| Zhu Gf et al. (2017) [34] | China | 32 | 15/17 | 65.6 ± 11.9 | AT | 12W | HGS |

| 31 | 16/15 | 66.3 ± 11.4 | CG | ||||

| Kim et al. (2016) [37] | Japan | 34 | 34/0 | 81.4 ± 4.2 | CT | 12W | HGS, GS |

| 34 | 34/0 | 81.1 ± 5.1 | CG | ||||

| Shahar et al. (2013) [59] | Malaysia | 19 | 19/0 | 69.7 ± 5.4 | RT | 12W | HGS, CST, TUGT |

| 19 | 19/0 | 67.2 ± 5.4 | CG | ||||

| Kim et al. (2011) [74] | Japan | 36 | 36/0 | 79.0 ± 2.9 | CT | 12W | GS |

| 37 | 37/0 | 78.7 ± 2.8 | CG | ||||

| Kim et al. (2012) [75] | Japan | 30 | 30/0 | 79.6 ± 4.2 | CT | 12W | HGS, GS, TUGT |

| 28 | 28/0 | 80.2 ± 5.6 | CG | ||||

| Wei N et al. (2016) [77] | China | 20 | - | 75.0 ± 6.0 | WBVL | 12W | CST, GS, TUGT |

| 20 | - | 76.0 ± 6.0 | CG | ||||

| Hamaguchi et al. (2017) [69] | Japan | 7 | 7/0 | 60.4 ± 2.7 | RAT | 12W | SMI, HGS |

| 8 | 8/0 | 60.6 ± 2.3 | CG | ||||

| Kemmler et al. (2010) [70] | Germany | 123 | 123/0 | 68.9 ± 3.9 | RAT | 18W | HGS, TUGT |

| 123 | 123/0 | 69.2 ± 4.1 | CG | ||||

| Hassan et al. (2016) [38] | Australia | 21 | - | 85.7 ± 7.0 | CT | 24W | HGS, GS |

| 21 | - | 86.1 ± 8.2 | CG | ||||

| Wei MQ et al. (2022) [60] | China | 30 | 16/14 | 66.7 ± 4.1 | RAT | 24W | SMI, HGS |

| 30 | 17/13 | 66.8 ± 3.8 | RT | ||||

| 30 | 14/16 | 65.4 ± 3.9 | CG | ||||

| Dong et al. (2021) [71] | China | 31 | 21/10 | 77.3 ± 6.3 | RAT | 12W | SMI, HGS, TUGT |

| 29 | 17/12 | 78.7 ± 4.8 | CG | ||||

| Liu et al. (2020) [72] | China | 40 | 17/23 | 67.5 ± 1.5 | RAT | 24W | SMI, KES, GS, TUGT |

| 40 | 13/27 | 68.5 ± 1.0 | CG | ||||

| Wang et al. (2021) [73] | China | 30 | 20/10 | 70.4 ± 5.1 | RAT | 12W | SMI, HGS, GS |

| 30 | 19/11 | 70.7 ± 3.9 | CG | ||||

| Wang LZ et al. (2019) [61] | China | 20 | 9/11 | 65.1 ± 3.4 | RT | 8W | HGS, KES |

| 20 | 10/10 | 64.2 ± 3.0 | AT | ||||

| 20 | 8/12 | 63.6 ± 5.2 | RAT | ||||

| 20 | 10/10 | 64.1 ± 2.8 | CG | ||||

| Zhang et al. (2023) [78] | China | 23 | 11/12 | 74.2 ± 3.2 | WBVL | 12W | SMI, HGS, GS |

| 23 | 10/13 | 73.2 ± 4.2 | WBVM | ||||

| 24 | 11/13 | 73.7 ± 3.5 | WBVH | ||||

| Peng et al. (2022) [63] | China | 39 | 23/16 | 72.1 ± 6.4 | AT | 8W | GS |

| 38 | 23/15 | 71.8 ± 5.7 | CT |

1Invention: RT resistance training, AT aerobic training, RAT resistance & aerobic training, CT comprehensive training, WBVL whole body vibration training - low frequency, WBVM whole body vibration training - medium frequency, WBVH whole body vibration training - high frequency, SM Self-managed training, RMT respiratory muscle training, BT balance training, CG control group; 2Outcome: SMI skeletal muscle index, HGS handgrip strength, KES knee extensor strength, CST chair stand test, GS gait speed, TUGT timed up and go test

Study risk-of-bias assessment

A high overall risk for bias in individual trials was observed. Exercise intervention trials are inherently difficult to blind, of the included studies, 6 RCTs (16.2%) were downgraded to high risk of bias due to allocation concealment and blinding [53, 56, 69, 71, 78, 79], 27 RCTs (72.9%) were considered as unclear risk for reasons such as incomplete assessment of outcome data, and only 4 RCTs (10.8%) were at low risk of bias across all domains [59–61, 67]. Figure 2 presents the risk of bias assessment graph. Figure 2a presents the risk of bias assessment for each study, according to the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool and Fig. 2b is the percent of studies with categories for risk of bias. The Appendix includes an explanation of the criteria used to judge the risk of bias for each domain, and reports the risk of bias results for all included trials. The high risk of bias in the included studies may affect the validity and reliability of the results, and thus, sensitivity analysis was performed to address this issue.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias assessment graph for included studies. a Summary for the risk of bias in each study, b Percent of studies with categories for risk of bias. D1 = random sequence generation, D2 = allocation concealment, D3 = blinding, D4 = missing outcome, D5 = selective reporting, D6 = other bias

Efficacy on muscle mass

We used SMI to determine the effect of each exercise intervention subtype on subjects’ muscle mass. Fifteen RCTs provided 917 subjects with SMI data [33, 56, 57, 60, 66–69, 71–73, 78, 79, 81], among them, three were three-arm trials [60, 78, 80] and the rest were two-arm trials. 10 intervention subtypes were included, of these, CG (14 RCTs), RAT (8 RCTs), and RT (4 RCTs) were the three most commonly investigated subtypes. Thus, our HGS network meta-analysis included 10 nodes in total, each representing a unique subtype of exercise intervention or control. Figure 3A shows the network plot of the SMI data, indicating the structure of the network and the number of studies for each direct comparison. The nodes with the most direct interactions in the network were CG (16 interactions), RAT (10 interactions), and RT (4 interactions). The model fit was good. Pooled network SMD values indicate that only RAT (SMD, 0.42; 95%CI, 0.04 to 0.81), WBVM (SMD, 1.54; 95%CI, 0.21 to 2.87) and WBVH (SMD, 2.92; 95%CI, 1.66 to 4.81) were significantly improved SMI when compared with CG (p < 0.05). League Table (Supplementary table 1) shows the network meta-analysis table of the SMI data, presenting the effect estimates and 95% CI for each comparison and outcome. SUCRA analysis provided a ranking of each subcatype exercise intervention according to its efficacy in improving SMI (Fig. 4A). The top-ranked exercise intervention subcatypes for improving SMI were WBVH (SUCRA values, 99.8), WBVM (SUCRA values, 85.2%), and WBVL (SUCRA values, 62.2%).

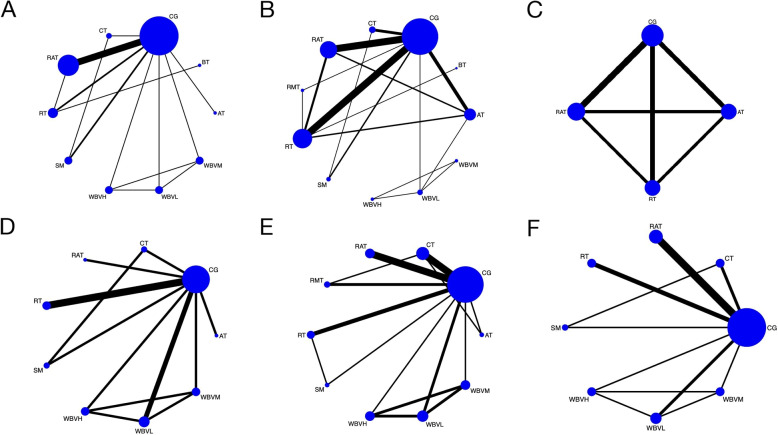

Fig. 3.

Network plots of A.SMI, B.HGS, C.KES, D.CST, E.GS and F.TUGT. The node’s size corresponded to the sample size of participants, and the line’s size indicated the number of studies comparing the two interventions. SMI, skeletal muscle mass; HGS, handgrip strength; KES, knee extension strength; GS, gait speed; CST, chair rise test; TUGT, timed up to go test; RT, resistance training; AT, aerobic training; RAT, resistance & aerobic training; CT, comprehensive training; WBVL, whole body vibration training - low frequency; WBVM, whole body vibration training - medium frequency; WBVH, whole body vibration training - high frequency; SM, self-managed training; RMT = respiratory muscle training; BT, balance training; CG, control group

Fig. 4.

The surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) value for A.SMI, B.HGS, C.KES, D.CST, E.GS AND F.TUGT. Larger SUCRA values indicate higher ranking probabilities. SMI, skeletal muscle mass; HGS, handgrip strength; KES, knee extension strength; GS, gait speed; CST, chair rise test; TUGT, timed up to go test; RT, resistance training; AT, aerobic training; RAT, resistance & aerobic training; CT, comprehensive training; WBVL, whole body vibration training - low frequency; WBVM, whole body vibration training - medium frequency; WBVH, whole body vibration training - high frequency; SM, self-managed training; RMT = respiratory muscle training; BT, balance training; CG, control group

I2

50%, indicates no significant statistical heterogeneity; node splitting indicates no significant loop inconsistency (p > 0.005), as shown in Fig. 6A, no warm color increase was observed. Based on the results of the tests with a funnel plot (Fig. 5A), there was no evidence of publication bias.

50%, indicates no significant statistical heterogeneity; node splitting indicates no significant loop inconsistency (p > 0.005), as shown in Fig. 6A, no warm color increase was observed. Based on the results of the tests with a funnel plot (Fig. 5A), there was no evidence of publication bias.

Fig. 6.

Heat plots for A.SMI, B.HGS, C.KES, D.CST, E.GS AND F.TUGT. Gray square size represents the relative contribution of the direct evidence (column) and the network evidence (row). Inconsistencies between the row’s direct and indirect evidence are represented by the colors; warmer colors indicate stronger inconsistencies. SMI, skeletal muscle mass; HGS, handgrip strength; KES, knee extension strength; GS, gait speed; CST, chair rise test; TUGT, timed up to go test; RT, resistance training; AT, aerobic training; RAT, resistance & aerobic training; CT, comprehensive training; WBVL, whole body vibration training - low frequency; WBVM, whole body vibration training - medium frequency; WBVH, whole body vibration training - high frequency; SM, self-managed training; RMT = respiratory muscle training; BT, balance training; CG, control group

Fig. 5.

Funnel plots of A.SMI, B.HGS, C.KES, D.CST, E.GS AND F.TUGT. In Fig. A: A=CG; B=AT; C=RAT; D=CT; E=WBVL; F=WBVM; G=WBVH; H=SM; I=BT; J=RT. In Fig. B: A=CG; B=AT; C=RAT; D=CT; E=WBVL; F=WBVM; G=WBVH; H=SM; I=RMT; J=BT; K=RT. In Fig. C: A=CG; B=AT; C=RAT; D=RT. In Fig. D: A=CG; B=AT; C=RAT; D=CT; E=WBVL; F=WBVM; G=WBVH; H=SM; I=RT. In Fig. E: A=RT; B=AT; C=RAT; D=CT; E=WBVL; F=WBVM; G=WBVH; H=RMT; I=SM; J=CG. In Fig. F: A=CG; B=RAT; C=CT; D=WBVL; E=WBVM; F=WBVH; G=SM; H=RT. SMI, skeletal muscle mass; HGS, handgrip strength; KES, knee extension strength; GS, gait speed; CST, chair rise test; TUGT, timed up to go test; RT, resistance training; AT, aerobic training; RAT, resistance & aerobic training; CT, comprehensive training; WBVL, whole body vibration training - low frequency; WBVM, whole body vibration training - medium frequency; WBVH, whole body vibration training - high frequency; SM, self-managed training; RMT = respiratory muscle training; BT, balance training; CG, control group

Efficacy on muscle strength

We used HGS to determine the effect of each exercise intervention subtype on subjects’ muscle strength in the upper limbs, and KES to determine muscle strength in the lower limbs.

Handgrip strength

Twenty-seven RCTs provided 1694 subjects with HGS data [28, 31–35, 37, 38, 53, 54, 56–62, 65, 69–71, 73, 75, 78, 79, 81], among them, five were three-arm trials [54, 60, 62, 78, 80], two were four-arm trails [28, 61], and the rest were two-arm trials. All 11 intervention subtypes were included, of these, CG (25 RCTs), RT (11 RCTs), and RAT (10 RCTs) were the three most commonly investigated subtypes. Thus, our HGS network meta-analysis included 11 nodes in total, each representing a unique subtype of exercise intervention or control. Figure 3B shows the network plot of the HGS data, indicating the structure of the network and the number of studies for each direct comparison. The nodes with the most direct interactions in the network were CG (33 interactions), RT (17 interactions), and RAT (15 interactions). The model fit was good. Pooled network SMD values indicate that only WBVH (SMD, 9.57; 95%CI, 3.01 to 16.14) and RAT (SMD, 2.96; 95%CI, 1.37 to 4.55) were effective in improving subjects’ HGS compared with CG (p < 0.05), as shown in Supplementary Table 2. SUCRA analysis provided a ranking of each subcatype exercise intervention according to its efficacy in improving HGS (Fig. 4B). The top-ranked exercise intervention subcatypes for improving HGS were WBVH (SUCRA values, 96.5%), RMT (SUCRA values, 75.4%), and WBVM (SUCRA values, 71.8%).

I2

50%, indicate no significant statistical heterogeneity; node splitting indicates no significant loop inconsistency (p > 0.005), as shown in Fig. 6B, no warm color increase was observed. The funnel plot appeared symmetrical, indicated no publication bias (Fig. 5B).

50%, indicate no significant statistical heterogeneity; node splitting indicates no significant loop inconsistency (p > 0.005), as shown in Fig. 6B, no warm color increase was observed. The funnel plot appeared symmetrical, indicated no publication bias (Fig. 5B).

Knee extension strength

Six RCTs provided KES data [28, 33, 58, 61, 67, 72], among them, two were four-arm trails [28, 61] and the rest were two-arm trials. In addition to control, 3 exercise intervention subtypes, RT, RAT and AT, were researched. As shown in Fig. 3C, our KES network meta-analysis included 4 nodes in total, each representing a unique subtype of exercise intervention or control. Figure 3 C shows the network plot of the KES data, indicating the structure of the network and the number of studies for each direct comparison. The nodes with the most direct interactions in the network were CG (10 interactions) and RT (8 interactions). The model fit was good. Pooled network SMD values indicate that RT (SMD, 5.70; 95%CI, 3.08 to 8.31) and RAT (SMD, 2.59; 95%CI, 0.52 to 4.66) were effective in improving subjects’ KES compared with CG (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 3). Notably, the result also indicate that CG was more effective than AT in improving subjects’ KES, although the difference was not significant (p > 0.05). SUCRA analysis provided a ranking of each subcatype exercise intervention according to its efficacy in improving KES. The top-ranked exercise intervention subcatypes for improving KES were RT (SUCRA values, 99.3%) and RAT (SUCRA values, 66.4%), as shown in Fig. 4C. However, the results of the ranking indicate that AT (SUCRA values, 13.4) is still ranked last, even after CG (SUCRA values, 20.8%).

I2 50%, indicate no significant statistical heterogeneity; node splitting indicates no significant loop inconsistency (p > 0.005), as shown in Fig. 6C, no warm color increase was observed. Figure 5C appeared symmetrical, indicated no publication bias.

50%, indicate no significant statistical heterogeneity; node splitting indicates no significant loop inconsistency (p > 0.005), as shown in Fig. 6C, no warm color increase was observed. Figure 5C appeared symmetrical, indicated no publication bias.

Efficacy on muscle function

We used CST, GS and TUGT to determine the effect of each exercise intervention subtype on subjects’ muscle function.

Chair stand test

Eight RCTs provided 443 subjects with CST data [31–33, 35, 59, 76, 77, 80], including one four-arm trial [76], one three-arm trial [80], all the rest were two-arm trials. 9 intervention subtypes were included, of these, CG (8 RCTs), RT (3 RCTs), and WBVL (2 RCTs) were the three most commonly investigated subtypes. Thus, our CST network meta-analysis included 9 nodes in total, each representing a unique subtype of exercise intervention or control. Figure 3D shows the network plot of the CST data, indicating the structure of the network and the number of studies for each direct comparison. The nodes with the most direct interactions in the network were CG (11 interactions), WBVL (4 interactions) and RT (3 interactions). The model fit was good. Pooled network SMD values revealed that no subtype of exercise intervention was significantly superior to CG in improving CST (p > 0.005), as shown in Supplementary Table 4. SUCRA analysis provided a ranking of each subcatype exercise intervention according to its efficacy in improving CST. The top-ranked exercise intervention subcatypes for improving CST were CT (SUCRA values, 76.5%), SM (SUCRA values, 75.4%) and WBVM (SUCRA values, 53.8%), as shown in Fig. 4D.

I2 50%, indicate no significant statistical heterogeneity; node splitting indicates no significant loop inconsistency (p > 0.005), unfortunately, the heat plot could not be analysed due to the insufficient number of designs. Figure 5D appeared symmetrical, indicated no publication bias.

50%, indicate no significant statistical heterogeneity; node splitting indicates no significant loop inconsistency (p > 0.005), unfortunately, the heat plot could not be analysed due to the insufficient number of designs. Figure 5D appeared symmetrical, indicated no publication bias.

Gait speed

Nineteen RCTs provided GS results [33, 35, 37, 38, 54, 55, 58, 63, 64, 67, 72–80], including one four-arm trial [76], three three-arm trial [54, 78, 80], all the rest were two-arm trials. A total of 1114 subjects were randomised. 10 intervention subtypes were included, of these, CG (17 RCTs), CT (6 RCTs), and RAT (5 RCTs) were the three most commonly investigated subtypes. Thus, our GS network meta-analysis included 10 nodes in total, each representing a unique subtype of exercise intervention or control. Figure 3E shows the network plot of the GS data, indicating the structure of the network and the number of studies for each direct comparison. The nodes with the most direct interactions in the network were CG (21 interactions), CT (7 interactions) and RAT (5 interactions). The model fit was good. Pooled network SMD values indicate that no subtype of exercise intervention was significantly superior to CG in improving GS ( ), as shown in Supplementary Table 5. SUCRA analysis provided a ranking of each subcatype exercise intervention according to its efficacy in improving GS. The top-ranked exercise intervention subcatypes for improving GS were WBVH (SUCRA values, 76.5%), AT (SUCRA values, 74.9%) and CT (SUCRA values, 6%), as shown in Fig. 4E.

), as shown in Supplementary Table 5. SUCRA analysis provided a ranking of each subcatype exercise intervention according to its efficacy in improving GS. The top-ranked exercise intervention subcatypes for improving GS were WBVH (SUCRA values, 76.5%), AT (SUCRA values, 74.9%) and CT (SUCRA values, 6%), as shown in Fig. 4E.

There was evidence of significant heterogeneity and inconsistency in the GS network meta-analysis, as indicated by the I2 statistic and the node splitting test. Figure 6D visualises the heterogeneity and inconsistency, as shown by the warm colour in the plot indicating the degree of inconsistency of CG with AT and CT, respectively. Figure 5E appeared symmetrical, indicating no publication bias.

Timed up and go test

Twelve RCTs provided TUGT data [31, 35, 58, 59, 64, 70–72, 75–77, 80], among them, one was four-arm trail [76], one was three-arm trail [80] and the rest were two-arm trials. A total of 876 subjects were randomised. 8 intervention subtypes were included, of these, CG (12 RCTs), RAT (5 RCTs), and RT (3 RCTs) were the three most commonly investigated subtypes. Thus, our TUGT network meta-analysis included 8 nodes in total, each representing a unique subtype of exercise intervention or control. Figure 3F shows the network plot of the TUGT data, indicating the structure of the network and the number of studies for each direct comparison. The nodes with the most direct interactions in the network were CG (15 interactions), RAT (5 interactions) and RAT (3 interactions). The model fit was good. Pooled network SMD values indicate that only RT (SMD, −1.95; 95%CI, −3.30 to −0.61) and RAT (SMD, −1.31; 95%CI, −2.18 to −0.43) were effective in improving subjects’ TUGT compared with CG (p < 0.05), as shown in Supplementary Table 6. SUCRA analysis provided a ranking of each subcatype exercise intervention according to its efficacy in improving TUGT. The top-ranked exercise intervention subcatypes for improving TUGT were CT (SUCRA values, 75.2%), RT (SUCRA values, 72.4%) and SM (SUCRA values, 71.0%), as shown in Fig. 4F.

I2 50%, indicate no significant statistical heterogeneity; node splitting indicates no significant loop inconsistency (p > 0.005), as shown in Fig. 6E, no warm color increase was observed. Figure 5F appeared symmetrical, indicated no publication bias.

50%, indicate no significant statistical heterogeneity; node splitting indicates no significant loop inconsistency (p > 0.005), as shown in Fig. 6E, no warm color increase was observed. Figure 5F appeared symmetrical, indicated no publication bias.

Discussion

Sarcopenia is one of the most common conditions affecting older adults [82], with more than one tenth of older adults living in the community having low muscle mass and strength [83]. Indeed, the prevalence of sarcopenia has doubled in the last decade compared to the previous two decades, a tendency that has been linked to aging, sedentary lifestyles, and poor nutrition [84]. Fortunately, older adults with sarcopenia can benefit from regular and appropriate exercise, which can prevent or delay the loss of muscle mass and strength and improve their health and well-being [85]. The aim of this study was to compare the relative efficacy of different exercise intervention subtypes for age-related sarcopenia, we conducted a network meta-analysis of 37 RCTs involving 2322 older adults with sarcopenia,and compared the effectiveness of various exercise intervention subtypes in improving muscle mass, strength and function. We hypothesized that resistance training (RT) would be the most effective exercise intervention subtype for sarcopenia, as it can increase muscle mass and strength by inducing muscle hypertrophy and neural adaptation. However, our network meta-analysis results suggested that WBVH and CT were equally or more effective than RT in improving muscle mass, strength, and function. These findings challenge the conventional wisdom that RT is the best option for sarcopenia prevention and treatment [41, 86, 87], and suggest that WBVH and CT may have additional benefits for sarcopenia that RT does not provide.

We used SMI, HGS, KES, GS, CST and TUGT as outcome measures to evaluate the effects of exercise interventions on muscle mass, strength, and function, respectively. For muscle mass, our network meta-analysis results suggested that only RT, WBVM and WBVH were significantly better than control in increasing SMI. Notably, based on the SUCRA value, WBVH has been identified as the most efficacious intervention, compared to all other subtypes, including RT. As for improving muscle strength, our study revealed that, as compared to CG, only WBVH and RAT significantly improved HGS, while RT and RAT significantly improved KES. Additionally, WBVH and RT had the highest SUCRA values and were ranked as the most efficacious interventions for HGS and KES, respectively. Regarding the improvement of muscle function, the results of our network meta-analysis showed that compared to CG, only RT and RAT were able to reduce TUGT time, while no exercise intervention subtypes were able to significantly reduce CST time or improve GS. Despite the failure of existing exercise interventions to demonstrate significant effects in improving muscle function, SUCRA values ranking the subtypes of exercise intervention showed that CT ranked first in reducing both TUGT and CST time, and WBVH ranked first in improving GS. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive network meta-analysis to comparatively evaluate the effectiveness of various subcatypes of exercise intervention for sarcopenia. The results of our study indicate that there are notable differences among the effectiveness of various exercise intervention subtypes for sarcopenia. More importantly, contrary to the commonly accepted notion of RT being the most effective intervention for sarcopenia, our findings indicate that WBVH and CT can serve as effectively as RT in managing sarcopenia, and in some aspects, even better. We acknowledge that this focus on SMI may limit the generalizability of our findings, as other muscle mass indexes such as appendicular lean mass index (ALMI) are also commonly used in sarcopenia research. Future studies could benefit from exploring these additional indexes to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of different exercise interventions on sarcopenia.

Previoulsy published pairwise meta-analyses and network meta-analyses have focused on comparing a limited number of subtypes or exercise interventions with other mainstream non-pharmacological therapies. The NMA by Zeng et al. [88] of 20 RCTs found that RT and CT were effective for improving physical ability and performance in older adults with sarcopenia. However, it focused on analysing the effects of common subtypes of exercise interventions on muscle function, neglecting muscle mass and strength, which are also core indicators for evaluating sarcopenia. Another NMA by Shen et al. [87] of 42 RCTs proved that RT with or without nutrition, as well as CT and BT, were the most effective interventions for improving the quality of life of elderly patients with sarcopenia. Neverless, this study included RCTs that combined exercise and nutrition as an intervention, which may have confounded or altered the effect of the exercise intervention, and it also omitted some important differences between exercise intervention subtypes, simplifying the comparison and interpretation of results. In contrast to these meta-analyses, our network meta-analysis integrates a much broader base of published RCT evidence on exercise interventions for age-related sarcopenia, providing a more precise typology of exercise interventions and a comprehensive assessment of individual outcomes in an overall analysis. More specifically, we imposed no restrictions on the languages of the studies and added manual backtracking searches to maximise the number of eligible RCTs in our study. Meanwhile, we also examined the effect of exercise interventions on individual outcomes such as KES, CST, and GS, using endpoints that were relatively standardised across trials and closely related to the the diagnostic indicators recommended by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia. As a result, our network meta-analysis represents a significant improvement over earlier pairwise meta-analyses and network meta-analyses.

Appropriate exercise intervention subtype selection is a major challenge for older adults with sarcopenia, particularly for those suffering from other musculoskeletal system disorders such as osteoporosis [89]. Our network meta-analysis provides valuable insights into the comparative effectiveness of various exercise intervention subtypes for sarcopenia in older adults. We found that WBVH, CT and RT were the most effective exercise intervention subtypes for age-related sarcopenia. According to our results, WBVH ranked first in efficacy SUCRA values for SMI, HGS and GS, and CT ranked highest in efficacy SUCRA values for TUCT and CST, suggesting that WBVH is the optimal exercise intervention for sarcopenia, both in terms of muscle mass, strength, and function, whereas CT is more advantageous in terms of improvement in physical ability and performance. This finding is novel and intriguing, as it challenges the conventional wisdom that RT is the best option for sarcopenia prevention and treatment [1, 39]. Just considering the quantity of first-hand evidence the outcome obtained by this network meta-analysis might be more credible. According to our findings, although RT also ranked relatively high in terms of efficacy SUCRA values for TUGT and HGS, it only ranked first for KES, and the efficacy rankings for KSE did not incorporate WBVH and CT. About this discrepancy, we propose that WBVH and CT may have additional benefits for sarcopenia that RT does not provide.

About WBVH, we speculated that this may be due to its different mechanism of action on the neuromuscular system than other exercise intervention subtypes. WBVH may stimulate the reflexive activation of muscle fibers, increase the recruitment of motor units, and enhance the coordination of muscle groups [78], which could improve the muscle quality and function of older adults with sarcopenia, especially for fast-twitch fibers that are more prone to sarcopenia [90]. Besides that, WBVH can also increase blood flow, oxygen delivery and growth hormone secretion to the muscles, thus promoting muscle growth and repair [91]. Previous studies have confirmed that WBVH stimulates the neuromuscular system, thereby improving muscle coordination, balance, and reflexes [92], as well as reducing muscle fatigue and soreness, leading to improved muscle performance and recovery [93]. These effects of WBVH may explain why it can improve SMI, HGS, and GS, especially GS, in older adults with sarcopenia better than other exercise intervention subtypes. As for CT, it has been shown to have positive effects on muscle mass, strength, and power, as well as on functional performance and cardiovascular fitness in older adults with sarcopenia [37, 38]. According to our results, CT ranked highest in efficacy SUCRA values for TUGT and CST, suggesting that CT is the best exercise intervention for sarcopenia in terms of improvement in physical ability and performance. This is consistent with previous studies that reported that CT can improve TUGT and CST performance in older adults with sarcopenia [1, 89]. We speculate that this may be due to the different mechanisms of action of CT and other exercise intervention subtypes on the cardiovascular and respiratory systems. TUGT and CST require not only muscle strength and power, but also balance, coordination, endurance, and fatigue resistance, which depend on the cardiovascular [94] and respiratory systems [95], as well as the neuromuscular system [96]. CT may provide a more holistic and integrated stimulus for these systems, while other exercise intervantions may focus more on the neuromuscular system. In terms of RT, it is a well-established and widely recommended therapy for sarcopenia, as it can increase muscle mass and strength by inducing muscle hypertrophy [97] and neural adaptation [98]. Our findings corroborate this as well: RT ranked first in efficacy SUCRA values for KES, which is a measure of the maximal force generated by the knee extensor muscles, such as the quadriceps. Although RT is not first in either HGS or TUGT in our measurements, it is relatively high. This may be attributed to RT presents greater advantages in terms of instrumentation, programme design and safety than WBVH and CT, it does not require specialized equipment or devices, such as vibration platforms or treadmills, which may be expensive, inaccessible, or unsafe for some older adults. Moreover, RT can be tailored to the individual needs and preferences of the older adults, by adjusting the load, volume, frequency, and intensity of the exercises. These mechanisms may explain why WBVH and CT can improve muscle mass, strength, and function better than RT in older adults with sarcopenia. We believe that WBVH, CT, and RT are all effective exercise interventions for sarcopenia in older adults, WBVH and CT can serve as effective alternatives or complements to RT for sarcopenia prevention and treatment, but they may have different effects and benefits for different outcomes and goals.

In summary, the novelty of this study lies in its use of a Bayesian network meta-analysis to compare the relative efficacy of different exercise intervention subtypes for age-related sarcopenia, which is an understudied topic. This systematic review currently includes 37 RCTs with a total of 2322 subjects and 10 unique exercise intervention subtypes. We conducted the literature search, eligibility evaluation, and data extraction separately and in duplicate, with any inconsistencies handled by agreement. We used the Bayesian framework, a method that offers greater flexibility and more natural interpretability, describing the relative effects between two subtypes with a probability distribution of random variables, which was preferred for network meta-analysis. According to the value of SUCRA, whole body vibration training with high frequency was the most comprehensive and effective exercise method for improving subjects’ SMI (99.8%), HGS (96.5%) and GS (76.5%). Meanwhile, comprehensive training was the most effective form of exercise for improving muscle function, CST (76.5%) and TUGT (75.2%). Furthermore, resistance training was also a more comprehensive exercise method, ranking relatively high on the TUGT and HGS, and ranking first on the KES (99.3%). The significance of this study lies in the fact that the most effective subtype of exercise intervention for sarcopenia is still unclear because there is a lack of published evidence comparing their effectiveness, this study provides crucial information for clinicians and researchers to select the most appropriate subtype of exercise intervention for their patients and future studies. Therefore, this study has the potential to enhance the quality of life for older adults and contribute to the prevention and management of sarcopenia.

However, our findings should be interpreted with caution, as there are several limitations and uncertainties in the current evidence base. Firstly, the quality and quantity of the included RCTs were suboptimal, as many of them had unclear or high risk of bias, small sample sizes, short duration, and inconsistent reporting of results. These factors may introduce heterogeneity, inconsistency, and publication bias in the network meta-analysis, and reduce the generalizability and reliability of the results. We performed sensitivity analysis to address these issues, and found that the results were robust and stable. Secondly, the exercise intervention subtypes were diverse and complex, as they involved different factors such as exercise frequency, intensity, duration, and mode. We did not attempt to separately extract and analyze each specific subtype, as it would require considerable effort and resources, and may not be feasible or meaningful. We used standardized mean differences to pool the results across different outcome measures, and SUCRA values to rank the exercise intervention subtypes according to their efficacy. However, these methods may not capture the nuances and differences among the exercise intervention subtypes, and may not reflect the clinical significance of the results. Therefore, future research should adopt more rigorous and consistent methods to design, conduct, and report exercise interventions for sarcopenia, and use more specific and relevant outcome measures to evaluate their effects. This will contribute to the construction of a more reliable and pragmatic evidence base, providing solid support for the practice and guidance of exercise interventions.

Conclusion

Our network meta-analysis revealed significant variations in the effectiveness of different exercise intervention subtypes for sarcopenia. We found that certain exercise intervention subtypes were more effective for specific muscle-related outcomes. Whole body vibration training with high frequency is the most comprehensive and effective exercise method for improving muscle mass, muscle strength, and muscle function. Comprehensive training is the most effective form of exercise for improving muscle function. Resistance training is also a more comprehensive exercise method, ranking relatively high on the TUGT and HGS, and ranking first on the KES. These findings provide valuable evidence for determining the most effective exercise intervention subtype in managing age-related sarcopenia.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

Meta-analysis registration

This study was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023474627).

Authors' contributions

Wei and Wang contributed to study concept and design. Wei and He independently reviewed studies and extracted data. Wang, Meng and Zhang did the statistical analyses. Wei, He, Wang, Meng, and Zhang analysed and interpreted the data. Wei and He drafted the manuscript, Wang and Yang contributed important revisions to the intellectual content of the manuscript.

Funding

Guang Yang obtained “The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities” (Number: 135222026).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guang Yang, Email: yangg100@nenu.edu.cn.

Ziheng Wang, Email: wangzh654@nenu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morley J. Sarcopenia: diagnosis and treatment. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12:452–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, Iijima K, et al. Asian working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(3):300–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang M, Liu Y, Zuo Y, Tang H. Sarcopenia for predicting falls and hospitalization in community-dwelling older adults: EWGSOP versus EWGSOP2. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):17636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen I, Shepard DS, Katzmarzyk PT, Roubenoff R. The healthcare costs of sarcopenia in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(1):80–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.for Health Statistics NC, et al. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1600 Clifton Rd, vol 30333. Atlanta; 2012

- 7.Goates S, Du K, Arensberg M, Gaillard T, Guralnik J, Pereira SL. Economic impact of hospitalizations in US adults with sarcopenia. J Frailty Aging. 2019;8:93–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petermann-Rocha F, Balntzi V, Gray SR, Lara J, Ho FK, Pell JP, et al. Global prevalence of sarcopenia and severe sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13(1):86–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu J, Wan CS, Ktoris K, Reijnierse EM, Maier AB. Sarcopenia is associated with mortality in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontology. 2022;68(4):361–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeung SS, Reijnierse EM, Pham VK, Trappenburg MC, Lim WK, Meskers CG, et al. Sarcopenia and its association with falls and fractures in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10(3):485–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsumoto H, Tanimura C, Tanishima S, Osaki M, Noma H, Hagino H. Sarcopenia is a risk factor for falling in independently living Japanese older adults: a 2-year prospective cohort study of the gaina study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(11):2124–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi T, Umegaki H, Makino T, Cheng XW, Shimada H, Kuzuya M. Association between sarcopenia and depressive mood in urban-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(6):508–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martin FC. Frailty, sarcopenia, falls and fractures. In: Falaschi P, Marsh D, editors. Orthogeriatrics: Practical Issues in Geriatrics. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 47–61.

- 14.Olgun Yazar H, Yazar T. Prevalence of sarcopenia in patients with geriatric depression diagnosis. Irish Journal of Medical Science (1971 -). 2019;188:931–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang KV, Hsu TH, Wu WT, Huang KC, Han DS. Is sarcopenia associated with depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Age Ageing. 2017;46(5):738–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwak JY, Kwon KS. Pharmacological interventions for treatment of sarcopenia: current status of drug development for sarcopenia. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2019;23(3):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burton LA, Sumukadas D. Optimal management of sarcopenia. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:217–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Lach-Trifilieff E, Minetti GC, Sheppard K, Ibebunjo C, Feige JN, Hartmann S, et al. An antibody blocking activin type ii receptors induces strong skeletal muscle hypertrophy and protects from atrophy. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34(4):606–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rooks D, Praestgaard J, Hariry S, Laurent D, Petricoul O, Perry RG, et al. Treatment of sarcopenia with bimagrumab: results from a phase ii, randomized, controlled, proof-of-concept study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(9):1988–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dent E, Morley J, Cruz-Jentoft A, Arai H, Kritchevsky S, Guralnik J, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for sarcopenia (icfsr): screening, diagnosis and management. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22:1148–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phu S, Boersma D, Duque G. Exercise and sarcopenia. J Clin Densitom. 2015;18(4):488–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Konopka AR, Douglass MD, Kaminsky LA, Jemiolo B, Trappe TA, Trappe S, et al. Molecular adaptations to aerobic exercise training in skeletal muscle of older women. J Gerontol Ser Biomed Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(11):1201–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karavirta L, Häkkinen A, Sillanpää E, García-López D, Kauhanen A, Haapasaari A, et al. Effects of combined endurance and strength training on muscle strength, power and hypertrophy in 40–67-year-old men. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21(3):402–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gudlaugsson J, Aspelund T, Gudnason V, Olafsdottir AS, Jonsson PV, Arngrimsson SA, et al. The effects of 6 months’ multimodal training on functional performance, strength, endurance, and body mass index of older individuals. Are the benefits of training similar among women and men? Laeknabladid. 2013;99(7-8):331–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Sousa N, Mendes R, Silva A, Oliveira J. Combined exercise is more effective than aerobic exercise in the improvement of fall risk factors: a randomized controlled trial in community-dwelling older men. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(4):478–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galvao DA, Taaffe DR. Resistance exercise dosage in older adults: single-versus multiset effects on physical performance and body composition. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2090–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konopka AR, Harber MP. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy after aerobic exercise training. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2014;42(2):53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen HT, Chung YC, Chen YJ, Ho SY, Wu HJ. Effects of different types of exercise on body composition, muscle strength, and IGF-1 in the elderly with sarcopenic obesity. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(4):827–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White Z, Terrill J, White RB, McMahon C, Sheard P, Grounds MD, et al. Voluntary resistance wheel exercise from mid-life prevents sarcopenia and increases markers of mitochondrial function and autophagy in muscles of old male and female c57bl/6j mice. Skeletal Muscle. 2016;6(1):1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landi F, Marzetti E, Martone AM, Bernabei R, Onder G. Exercise as a remedy for sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17(1):25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vikberg S, Sörlén N, Brandén L, Johansson J, Nordström A, Hult A, et al. Effects of resistance training on functional strength and muscle mass in 70-year-old individuals with pre-sarcopenia: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019 1;20(1):28–34. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Yamada M, Kimura Y, Ishiyama D, Nishio N, Otobe Y, Tanaka T, et al. Synergistic effect of bodyweight resistance exercise and protein supplementation on skeletal muscle in sarcopenic or dynapenic older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(5):429–37. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Zhu Yq, Peng N, Zhou M, Liu Pp, Qi Xl, Wang N, et al. Tai Chi and whole-body vibrating therapy in sarcopenic men in advanced old age: A clinical randomized controlled trial. Eur J Ageing. 2019;16(3):273–82. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Zhu Gf, Shen Zf, Shen Qh, Jin Yq, Lou Zy. Effect of Yi Jin Jing (Sinew-transforming Qigong Exercises) on skeletal muscle strength in the elderly. J Acupunct Tuina Sci. 2017;15(6):434–9. Accessed 17 Nov 2023.

- 35.Makizako H, Nakai Y, Tomioka K, Taniguchi Y, Sato N, Wada A, et al. Effects of a multicomponent exercise program in physical function and muscle mass in sarcopenic/pre-sarcopenic adults. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1386. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Li Z, Cui M, Yu K, Zhang Xw, Li Cw, Nie Xd, et al. Effects of nutrition supplementation and physical exercise on muscle mass, muscle strength and fat mass among sarcopenic elderly: A randomized controlled trial. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2021;46(5):494–500. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Kim H, Kim M, Kojima N, Fujino K, Hosoi E, Kobayashi H, et al. Exercise and nutritional supplementation on community-dwelling elderly japanese women with sarcopenic obesity: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(11):1011–19. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Hassan BH, Hewitt J, Keogh JWL, Bermeo S, Duque G, Henwood TR. Impact of resistance training on sarcopenia in nursing care facilities: A pilot study. Geriatr Nurs. 2016;37(2):116–21. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Lu L, Mao L, Feng Y, Ainsworth BE, Liu Y, Chen N. Effects of different exercise training modes on muscle strength and physical performance in older people with sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang H, Huang WY, Zhao Y. Efficacy of exercise on muscle function and physical performance in older adults with sarcopenia: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(13):8212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vlietstra L, Hendrickx W, Waters DL. Exercise interventions in healthy older adults with sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Australas J Ageing. 2018;37(3):169–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bao W, Sun Y, Zhang T, Zou L, Wu X, Wang D, et al. Exercise programs for muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance in older adults with sarcopenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Dis. 2020;11(4):863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ, Caldwell DM, Lu G, Ades A. Evidence synthesis for decision making 4: inconsistency in networks of evidence based on randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Making. 2013;33(5):641–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dias S, Welton NJ, Jansen JP, Sutton AJ. Network meta-analysis for decision-making. John Wiley & Sons; 2018.

- 45.Madden L, Piepho HP, Paul P. Statistical models and methods for network meta-analysis. Phytopathology. 2016;106(8):792–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, Chaimani A, Schmid CH, Cameron C, et al. The prisma extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(11):777–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bahat G, Tufan A, Tufan F, Kilic C, Akpinar TS, Kose M, et al. Cut-off points to identify sarcopenia according to European working group on sarcopenia in older people (EWGSOP) definition. Clin Nutr. 2016;35(6):1557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123(3):A12–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Higgins JPT, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Sterne JAC. Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd ed. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2019. p. 205–228.

- 50.Rücker G, Schwarzer G. Ranking treatments in frequentist network meta-analysis works without resampling methods. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Follmann D, Elliott P, Suh I, Cutler J. Variance imputation for overviews of clinical trials with continuous response. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(7):769–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salanti G, Ades A, Ioannidis JP. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(2):163–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen HT, Wu HJ, Chen YJ, Ho SY, Chung YC. Effects of 8-week kettlebell training on body composition, muscle strength, pulmonary function, and chronic low-grade inflammation in elderly women with sarcopenia. Exp Gerontol. 2018;112:112–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cebriá M, Balasch-Bernat M, Tortosa M, Balasch PS. Effects of resistance training of peripheral muscles versus respiratory muscles in older adults with sarcopenia who are institutionalized: a randomized controlled trial. J Aging Phys Act. 2018;26(4):637–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vasconcelos KS, Dias J, Araújo MC, Pinheiro AC, Moreira BS, Dias RC. Effects of a progressive resistance exercise program with high-speed component on the physical function of older women with sarcopenic obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20:432–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piastra G, Perasso L, Lucarini S, Monacelli F, Bisio A, Ferrando V, et al. Effects of two types of 9-month adapted physical activity program on muscle mass, muscle strength, and balance in moderate sarcopenic older women. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chiu SC, Yang RS, Yang RJ, Chang SF. Effects of resistance training on body composition and functional capacity among sarcopenic obese residents in long-term care facilities: A preliminary study. BMC Geriatrics. 2018;18(1). Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Liao CD, Tsauo JY, Lin LF, Huang SW, Ku JW, Chou LC, et al. Effects of elastic resistance exercise on body composition and physical capacity in older women with sarcopenic obesity. Medicine. 2017;96(23):e7115. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Shahar S, Norshafarina, Badrasawi M, Noor, Abdul Manaf Z, Zaitun Yassin M, et al. Effectiveness of exercise and protein supplementation intervention on body composition, functional fitness, and oxidative stress among elderly Malays with sarcopenia. Clin Interv Aging. 2013:1365. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Wei M, Meng D, Guo H, He S, Tian Z, Wang Z, et al. Hybrid exercise program for sarcopenia in older adults: The effectiveness of explainable artificial intelligence-based clinical assistance in assessing skeletal muscle area. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):9952. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 61.Wang L, Guo Y, Luo J. Effects of home exercise on sarcopenia obesity for aging people. Chin J Rehabil Theory Pract. 2019;25(1):90–6. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu LY, Chan R, Kwok T, Cheng KCC, Ha A, Woo J. Effects of exercise and nutrition supplementation in community-dwelling older Chinese people with sarcopenia: A randomized controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2018;48(2):220–8. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Peng T, Zhu M, Lin X, Yuan J, Zhou F, Hu S, et al. Seffect of new yijinjing exercise on lower limb motor function and balance function in senile patients with sarcopenia. Chin Manipulation Rehabil Med. 2022;13(17):21–6. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liao CD, Tsauo JY, Huang SW, Ku JW, Hsiao DJ, Liou TH. Effects of elastic band exercise on lean mass and physical capacity in older women with sarcopenic obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park J, Kwon Y, Park H. Effects of 24-week aerobic and resistance training on carotid artery intima-media thickness and flow velocity in elderly women with sarcopenic obesity. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017;24(11):1117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang SW, Ku JW, Lin LF, Liao CD, Chou LC, Liou TH. Body composition influenced by progressive elastic band resistance exercise of sarcopenic obesity elderly women: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2017;53(4):556-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Lu Y, Niti M, Yap KB, Tan CTY, Zin Nyunt MS, Feng L, et al. Assessment of sarcopenia among community-dwelling at-risk frail adults aged 65 years and older who received multidomain lifestyle interventions. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1913346. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Jung WS, Kim YY, Park HY. Circuit training improvements in Korean women with sarcopenia. Percept Mot Skills. 2019;126(5):828–42. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Hamaguchi K, Kurihara T, Fujimoto M, Iemitsu M, Sato K, Hamaoka T, et al. The effects of low-repetition and light-load power training on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with sarcopenia: A pilot study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1). Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Kemmler W, von Stengel S, Engelke K, Häberle L, Mayhew JL, Kalender WA. Exercise, body composition, and functional ability: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(3):279–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dong X, Mo Y, Wang X, Wang x. Effects of resistance exercise on muscle mass, muscle strength and physical performance in the elderly at risk of sarcopenia. Chin Nurs Manag. 2021;21(8):1190–5.

- 72.Liu Y, Cai J. Effects of elastic band placement training on lower limb muscle strength in elderly patients with sarcopenia and functional motor capacity in elderly patients with sarcopenia. J Changchun Normal Univ. 2020;39(10):123–6.

- 73.Wang G, Cai W, Shen X, Li C, Xu Y. Effects of resistance training using elastic band for 12 weeks on muscle strength of elderly patients with sarcopenia in community. Chin J Clin Healthc. 2021;24(6).

- 74.Kim HK, Suzuki T, Saito K, Yoshida H, Kobayashi H, Kato H, et al. Effects of exercise and amino acid supplementation on body composition and physical function in communitydwelling elderly Japanese sarcopenic women: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;60(1):16–23. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Kim H, Suzuki T, Saito K, Yoshida H, Kojima N, Kim M, et al. Effects of exercise and tea catechins on muscle mass, strength and walking ability in communitydwelling elderly Japanese sarcopenic women: A randomized controlled trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;13(2):458–65. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Wei N, Pang MY, Ng SS, Ng GY. Optimal frequency/time combination of whole body vibration training for developing physical performance of people with sarcopenia: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31(10):1313–21. Accessed 17 Nov 2023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.Wei N, Ng S, Ng G, Lee R, Lau M, Pang M. Whole-Body vibration training improves muscle and physical performance in community dwelling with sarcopenia: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Phys Ther Rehabil. 2016;2(1). Accessed 17 Nov 2023.

- 78.Zhang X, Wei L, Liu F, Chen S, Ma X, Liu Z. Study on the effect of whole-body vibration training instrument with different frequency on rehabilitation of senile sarcopenia. China Med Equip. 2023;20(8):101–5. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maruya K, Asakawa Y, Ishibashi H, Fujita H, Arai T, Yamaguchi H. Effect of a simple and adherent home exercise program on the physical function of community dwelling adults sixty years of age and older with pre-sarcopenia or sarcopenia. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28(11):3183–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tsekoura M, Billis E, Tsepis E, Dimitriadis Z, Matzaroglou C, Tyllianakis M, et al. The effects of group and home-based exercise programs in elderly with sarcopenia: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med. 2018;7(12):480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]