Abstract

Background

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the leading cause of dementia, characterized by the accumulation of amyloid-βeta (Aβ) peptides and hyperphosphorylated tau protein. Altered sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) metabolism is associated with abnormal Aβ peptide accumulation in the brain. S1P receptors are increasingly being targeted for modulating the neuroinflammatory process in AD.

Methods

Wild-type male C57BL/6J mice were administered Aβ to induce the pathological state. The study included four experimental groups: (1) Control group (saline-treated), (2) Aβ group (Aβ + saline-treated), (3) Aβ + cP1P group (Aβ + cP1P at doses of 0.1 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg), and (4) Aβ+ P1P group (Aβ + P1P at doses of 0.1 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg). Behavioral experiments were conducted to assess cognitive and memory functions. Additionally, western blotting and confocal microscopy were performed to investigate molecular and cellular changes.

Results

The findings demonstrate that administration of S1P analogs cP1P and P1P at 0.1 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg significantly reduced Aβ burden by inhibiting the amyloidogenic pathway and decreasing hyperphosphorylated tau protein levels in the mouse brain. Additionally, cP1P and P1P inhibited glial cell activation, as indicated by reduced GFAP and Iba-1 expression, and modulated neuroinflammatory markers, including p-NF-κB, TNF-α, and IL-1β. Furthermore, they regulated S1PR1-mediated Akt/mTOR signaling while preserving mitochondrial function by decreasing the expression levels of p-JNK, Caspase-3, and PARP-1. Moreover, the cP1P and P1P effectively restored synaptic markers such as PSD-95, SNAP-25, and Syntaxin, and significantly improved behavioral outcomes in the Aβ-treated mice. In vitro, results also demonstrated that the novel cP1P and P1P enhanced cell viability against Aβ toxicity.

Keywords: CP1P, P1P, Alzheimer's disease (AD), Amyloid beta (Aβ), Neuroinflammation, Synaptic dysfunction

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most prevalent progressive neurodegenerative disorder and the leading cause of dementia. Its hallmark neuropathological features include accumulating extracellular neuritic plaques composed of amyloid beta (Aβ) and intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles primarily formed from hyperphosphorylated tau [1, 2]. Aβ is generated from amyloid precursor protein (APP) through sequential cleavage by β-secretase (BACE1) and γ-secretase, resulting in Aβ peptides of varying lengths [3]. Both enzymes localize within lipid rafts, specialized plasma membrane microdomains enriched in sphingolipids and cholesterol, suggesting that Aβ production is significantly influenced by membrane composition. This underscores the potential role of disrupted lipid homeostasis as a critical determinant in the progression of neurodegenerative diseases [4, 5].

AD pathology and normal brain aging are characterized by the accumulation of long-chain ceramides and cholesterol. Exposure of hippocampal neurons to Aβ increases cholesterol and ceramide species levels and induces oxidative stress within membranes [6]. Aβ oligomers have been shown to activate sphingomyelinases, thereby elevating ceramide levels in membranes [7], which in turn stimulate the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin, phosphorylated NF-κB (p-NF-κB), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [8]. Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a bioactive sphingolipid metabolite, is a critical second messenger in numerous signaling pathways. It regulates cellular processes such as proliferation, migration, inflammatory responses, vascular and immune system modulation, and apoptosis inhibition [9]. S1P is synthesized by the phosphorylation of sphingosine, a ceramide derivative, via sphingosine kinases (SphK1/2) and mediates its effects through five G protein-coupled S1P receptors (S1PR1-5) [10], which are expressed in various CNS cell types, including neurons, microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [11]. Within the CNS, S1P plays essential roles in neuronal protection and synaptic transmission by modulating membrane excitability and neurotransmitter release [12]. Elevated S1P levels have been observed in regions of microglial accumulation within the brain [13] and are known to contribute to astrogliosis [10, 14, 15].

Several studies and evidence link disrupted sphingolipid metabolism to a variety of neurodegenerative disorders [14, 16, 17]. Recently studies by Di Pardo et al., 2017 demonstrated significantly altered expression of S1P-metabolizing enzymes (SphK1 and S1P lyase) during early Huntington’s disease in both preclinical models and human post-mortem brain samples [15]. Furthermore, SphK1 activity declines with increasing Braak stages of AD pathology in the hippocampus, showing the loss of S1P as an early event in AD progression [10]. Phytosphingosine-1-phosphate (P1P) is a natural sphingolipid metabolite abundant in plants and fungi and, to a lesser extent, in animals [18, 19]. Structurally similar to S1P, P1P features an additional hydroxyl group at carbon-4 (C-4) instead of the trans-double bond between C-4 and C-5 in S1P. As a selective agonist of S1PR1 and S1PR4, the potential role of P1P in modulating AD pathology has not been previously explored. In this study, we investigate the effects of two S1P analogs—phytosphingosine-1-phosphate (P1P) and a synthetic derivative, cyclic phytosphingosine-1-phosphate (cP1P) in a dose-dependent manner using amyloid-β-treated mouse models. Our findings provide robust evidence that Aβ peptide administration induces AD-like pathology in adult mouse brains. Novel sphingolipid derivatives cP1P and P1P demonstrate significant neuroprotective effects, mitigating Aβ-induced toxicity and alleviating AD-associated neuropathological changes in vivo and in vitro. This is the first study to evaluate the therapeutic potential of these sphingolipid derivatives, which exhibit strong neuroprotective properties and dose-dependent anti-AD effects.

Our results suggest that disrupted sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling is intricately linked to neurodegeneration in AD. Moreover, restoring S1P homeostasis represents a promising therapeutic avenue. To this end, we have identified two candidate compounds (P1P and cP1P) with S1P-mimetic properties, which are promising candidates that exert their effects primarily through S1PR1 receptor activation.

Materials and methods

Preparation of Aβ oligomers and S1P analogs

Amyloid-beta oligomers (AβOs) were prepared as previously described (Ali et al., 2017). Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) analogs, including cP1P and P1P, were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 10 mg/mL stock concentrations.

Animal model and ethical approval

Wild-type male C57BL/6J mice (25–30 g, 8 weeks old) were procured from Samtako Bio, Korea. The mice were acclimatized for one week in the university’s animal facility under controlled conditions, maintaining a temperature of 23 ± 2 °C with a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Animals were provided ad libitum access to water and standard laboratory chow. All experiments were carried out by the ethical guidelines issued by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Division of Life Sciences and Applied Life Sciences, Gyeongsang National University, South Korea. Maximum effort was made to minimize the number of animals used and to ensure their welfare during experimental procedures.

Experimental groups

The animals were randomly divided (using a computer-generated randomization table and given coded IDs) into the following experimental groups, with each group consisting of 10 mice (n = 10):

Control group: saline-treated.

Aβ group: Aβ + saline-treated.

Aβ + cP1P group: Aβ + cP1P at doses of 0.1 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg.

Aβ + P1P group: Aβ + P1P at doses of 0.1 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg.

The experimenters who conducted behavioral testing and data collection were blinded to the treatment conditions. Western blot analysis and fluorescent imaging were carried out separately without the participants’ group assignments being known. Coded datasets were used for statistical analysis to preserve blinding.

Drug administration

After acclimatization of one week, the mice were anesthetized using a mixture of Rompun (0.05 mL/100 g body weight) and Zoletil (0.1 mL/100 g body weight) and positioned on a stereotaxic frame. Intracerebroventricular (ICV) injections of either aggregated Aβ1–42 peptide or vehicle (0.9% NaCl) were administered using a Hamilton microsyringe. The injection coordinates relative to the bregma were 1 mm mediolateral (ML), −0.2 mm anteroposterior (AP), and − 2.4 mm dorsoventral (DV). A total volume of 3 µL was injected per mouse at a controlled rate of 1 µL every 5 min. To minimize leakage of the injected solution, the needle was left in position for an additional 3 min before being slowly retracted. Isoflurane anesthesia was also provided instantly before Aβ administration to further reduce discomfort. As the procedure was minimally invasive, no additional analgesics were required. Humane goals were strictly adhered to prevent unnecessary distress or pain. All procedures were conducted under a controlled environment, with the temperature maintained at 36–37 °C to prevent hypothermia.

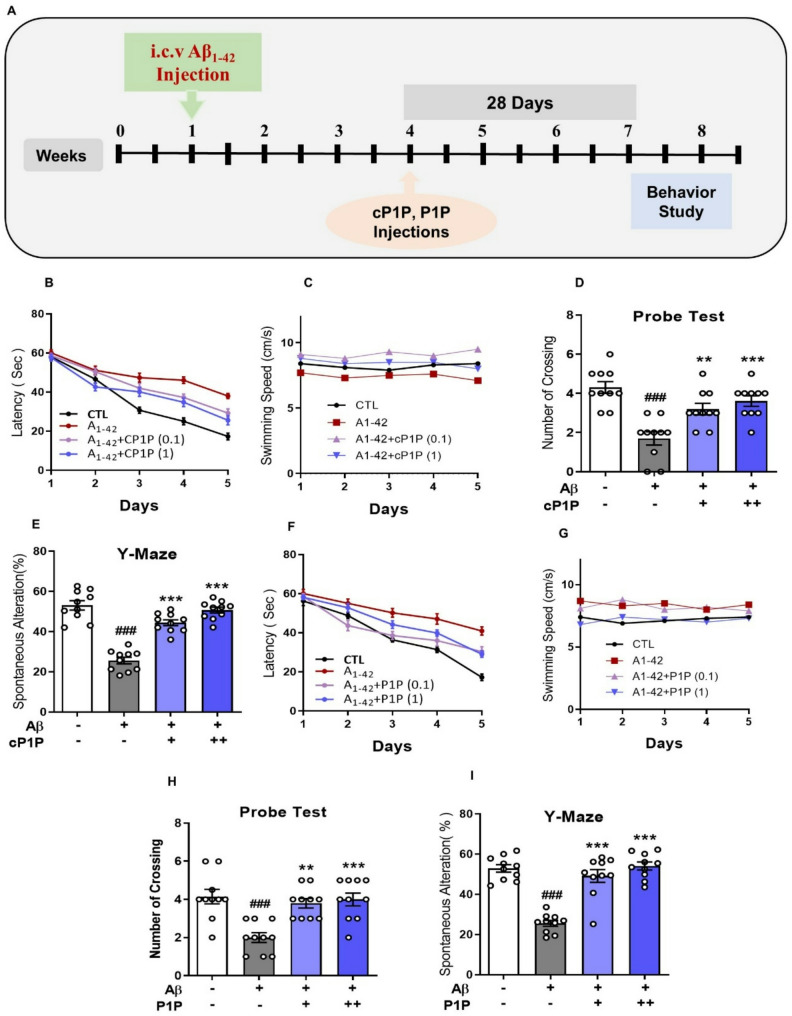

After four weeks following Aβ injections, mice in the respective experimental groups received intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of either vehicle (saline) or S1P analogs (cP1P or P1P) at doses of 0.1 mg/kg or 1 mg/kg, administered on alternate days for four weeks. A schematic representation of the experimental design is provided in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1.

cP1P and P1P Treatment Enhances Memory Performance in AD Mouse Model. A Schematic representation of the experimental study design. B Escape latency (time to locate the hidden platform) over five consecutive days in the Morris Water Maze (MWM) latency test for cP1P-treated mice (n = 10). C Swimming speed of mice during MWM training in cP1P-treated mice. D Number of crossings at the platform location during the MWM probe test in cP1P-treated mice, conducted in the absence of the platform. E Y-maze analysis illustrating the percentage of spontaneous alternation behavior in cP1P-treated mice (n = 10), reflecting working memory performance. F Escape latency to locate the hidden platform over five consecutive days during the MWM latency test for P1P-treated mice (n = 10). G Swimming speed of mice during MWM training in P1P-treated mice. H Number of crossings at the previous platform location during the MWM probe test for P1P-treated mice. I Y-maze analysis showing the percentage of spontaneous alternation behavior in P1P-treated mice (n = 10). The hash symbol (#) denotes a significant difference compared to the control group, whereas the asterisk (*) indicates a significant difference compared to the Aβ1–42-treated group. The ROUT test (Q = 1%) was used to check the data for outliers. All of the data points were included in the final analysis, and no notable outliers were found. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA followed by Student’s t-test. Significance levels: #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01; ###P < 0.001; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Morris water maze (MWM) test

Hippocampal spatial memory was evaluated using the Morris water maze (MWM) and Y-maze tests, as previously described [20, 21]. Behavioral assessments were conducted during the final week of the experimental period before the last intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections. The animals’ movements and routes were tracked and recorded using automated tracking software (SMART, Panlab Harvard Apparatus, Bioscience Company, Holliston, USA).

The MWM test was conducted in a circular tank (100 cm in diameter, 40 cm in height) filled with water maintained at 25 ± 2 °C, rendered opaque by the addition of non-toxic white ink. A transparent platform (10 cm in diameter, 14 cm in height) was submerged 1 cm below the water surface. To assess reference memory, mice underwent training for five consecutive days with the hidden platform fixed at a designated position in the center of one of the four quadrants. During each trial, the starting position was alternated among the other three quadrants. Each trial lasted up to 60 s, during which mice were required to locate the hidden platform. The escape latency (time taken to reach the platform) was recorded. Mice that failed to locate the platform within the allotted time were gently guided to it and allowed to remain on the platform for 30 s. To evaluate spatial memory retention, a single probe trial was conducted on the sixth day, 24 h after the final reference memory test. During the probe trial, the platform was removed, and mice were allowed to swim for 60 s to explore the tank. The time spent in the target quadrant (where the platform was previously located) and the number of crossings over the platform’s original position were recorded and analyzed.

Y-Maze test

Spontaneous alternation behavior, an indicator of the willingness to explore a novel environment, was assessed using a Y-shaped maze constructed of black-painted wood. The dimensions of each arm of the maze were 50 cm in length, 10 cm in width, and 20 cm in height. Behavioral testing was conducted in three independent sessions, during which each mouse was placed at the center of the maze and allowed to freely explore the apparatus for 8 min. An entry into an arm was defined as the mouse having at least 85% of its body within the arm. Spontaneous alternation percentage was calculated using the formula: [Successive triplet sets (entries into three different arms consecutively)/total number of arm entries − 2] × 100.

HT22 cell culture and Aβ treatment

HT22 cells, which are a subclone of the HT4 cell line (catalog no. SCC129; Sigma-Aldrich/Millipore), originally generated from primary mouse hippocampal neurons immortalized with a temperature-sensitive SV40 T-antigen, were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich. The HT22 mouse hippocampal neuronal cell line was cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic solution. The cells were maintained in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂ at 37 °C. Cultures were propagated in T-75 flasks and subsequently transferred to 6-well plates or 35 mm Petri dishes for experimental treatments. For immunofluorescence studies, cells were seeded onto specialized chamber slides to facilitate staining and imaging.

Amyloid-β (Aβ) oligomers were prepared as previously described (Ali et al., 2017). Upon reaching approximately 90% confluence, HT22 cells seeded in 35 mm Petri dishes or chamber slides were treated with two final concentrations of cP1P and P1P (2 µM and 5 µM). Following a 6-hour incubation period, the cells were exposed to 5 µM Aβ₁₋₄₂ oligomers and incubated for an additional 30 min. After treatment, the cells were harvested and prepared for western blot analysis.

Astrocyte cell culture

Primary astrocytes were extracted from postnatal day 0–2 (P0–P2) mouse pups, as described previously with minor modification [22, 23]. The cells were cultured on T75 flasks coated with poly-D-lysine and kept in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, high glucose; Gibco) with 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco) and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) added. The cultures were kept in a humidified environment with 5% CO₂ at 37 °C. The medium was changed every three to four days. Following confluence of 80–90%, microglia and oligodendrocyte precursors were shaken off, resulting in an enriched astrocyte population (>90% GFAP⁺). For the next tests, astrocytes were trypsinized, passaged, and seeded into six-well plates. The cells were then exposed to 5 µM pre-aggregated Aβ for 24 h to generate astrocytic stress. This concentration is hazardous to primary astrocytes and neurons. cP1P (2 µM or 5 µM) was applied to astrocytes in the experimental groups for one hour before they were exposed to Aβ. After treatment, cells were extracted and lysed in order to perform a Western blot examination.

MTT assay

The MTT assay was conducted following the manufacturer’s instructions to evaluate cell viability and optimize the effective dose of cP1P and P1P. HT22 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 1.4 × 10⁵ cells/well in 100 µL of DMEM and allowed to adhere. Cells were subsequently treated with a range of concentrations of cP1P and P1P (0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, and 20 µM) for 24 h. Following the treatment period, 20 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for an additional 3 h. Afterward, the medium was carefully removed, and 100 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to solubilize the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured at 550–570 nm using a microplate reader to determine the relative cell viability.

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

Following the completion of behavioral assessments, animals were euthanized under anesthesia, and the brains were rapidly excised. The cortex and hippocampal regions were carefully dissected and immediately stored at −80 °C for subsequent analyses. Protein extraction was performed from the hippocampal and cortical tissues, as well as from HT22 cell lysates, using PRO-PREP protein extraction solution (iNtRON Biotechnology). Samples were homogenized and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 25 min at 4 °C to isolate soluble protein fractions. Protein concentrations were quantified, and equal amounts (20–25 µg per sample) were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gels. Proteins were then transferred onto PVDF membranes, which were subsequently blocked with 5% (w/v) skim milk for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted 1:1000 in blocking solution. After thorough washing, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent (Atto Corporation, Tokyo) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Signals were detected using X-ray film, and the films were scanned and quantified using ImageJ software. β-actin was used as an internal loading control across all experiments. Details of the antibodies utilized in immunoblot and confocal microscopy are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of antibodies used for immunofluorescence and western blotting

| Antibody | Host | Application | Manufacturer | Catalog Number | Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ | Mouse | WB/IF | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, United States | SC28365 | 1:1000/1:100 |

| Bace-1 | Mouse | WB | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, United States | SC33711 | 1:1000 |

| p-Tau | Rabbit | WB | Cell Signaling | 12,885 S | 1:1000 |

| Iba-1 | Rabbit | WB/IF | Abcam | Ab178846 | 1:1000/1:100 |

| GFAP | Mouse | WB | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, United States | SC33673 | 1:1000 |

| S1PR1 | Mouse | WB | Abcam | Ab233386 | 1:1000 |

| AKT | Rabbit | WB | Cell Signaling | 9272 S | 1:1000 |

| p-AKT | Rabbit | WB | Cell Signaling | 9271 S | 1:1000 |

| mTOR | Mouse | WB | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, United States | SC517464 | 1:1000 |

| p-mTOR | Mouse | WB/IF | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, United States | SC293132 | 1:1000/1:100 |

| p-NF-кB | Mouse | WB | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, United States | SC136548 | 1:1000 |

| TNF-α | Mouse | WB | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, United States | SC52746 | 1:1000 |

| IL-1β | Mouse | WB | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, United States | SC32294 | 1:1000 |

| p-JNK | Mouse | WB | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, United States | SC6254 | 1:1000 |

| Parp-1 | Mouse | WB | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, United States | SC8007 | 1:1000 |

| Casp-3 | Rabbit | WB/IF | Cell Signaling | 9662 S | 1:1000/1:00 |

| PSD-95 | Mouse | WB/IF | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, United States | SC71933 | 1:1000/100 |

| SNAP-25 | Mouse | WB | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, United States | SC20038 | 1:1000 |

| SYN | Rabbit | WB/IF | Cell Signaling | 14,151 S | 1:1000/100 |

| NeuN | Mouse | WB | Cell Signaling | D4G4O | 1:1000 |

Immunofluorescence assays

Mice were anesthetized following behavioral assessments and transcardially perfused with physiological saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde to achieve tissue fixation. Post-perfusion, brains were immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h, followed by post-fixation in 25% sucrose solution prepared in PBS (0.01 mM) for 24 h. Subsequently, the brains were embedded in an O.C.T compound and gradually frozen in liquid nitrogen. Coronal sections were prepared at a thickness of 14 μm using a CM 1950 cryostat (Leica Biosystems). For in vitro studies, HT22 hippocampal neuronal cells cultured on specialized chamber slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature. Both brain tissue sections and fixed cells were allowed to dry overnight at room temperature. The slides were then washed twice with PBS (0.01 mM) for 10 min each and subjected to antigen retrieval by incubation in Proteinase K solution for 5 min at room temperature, followed by additional PBS washes. Subsequently, slides were blocked with a solution containing 2% normal goat serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 90 min at room temperature. Primary antibody incubation (dilution 1:100 in PBS) was carried out overnight at 4 °C. The following day, slides were incubated with FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (dilution 1:100 in PBS) for 90 min at room temperature in a darkened environment to prevent photobleaching. Slides were counterstained with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Madison, USA) to visualize nuclei, mounted with anti-fade mounting medium, and covered with glass coverslips. A laser-scanning confocal microscope (FluoView FV 1000 MPE, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used for confocal imaging in order to record high-resolution fluorescent signals.

Statistical analysis

The optical densities of Western blot bands (obtained from scanned X-ray films) and immunofluorescence images were quantified using ImageJ software. Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical comparisons between groups were conducted using one-way ANOVA, followed by Student’s t-test for post hoc analysis, utilizing Prism 6 (GraphPad Software). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical significance is denoted as follows: p < 0.05 (#), p < 0.01 (##), and p < 0.001 (###) based on one-way ANOVA and two-way ANOVA (for some behavioral analysis) followed by the Student’s t-test.

Results

cP1P and P1P improved memory impairment in AD mouse brain

To evaluate whether the administration of cP1P and P1P ameliorates Aβ-induced spatial memory deficits, mice were subjected to the Morris Water Maze (MWM) test. Following the training phase, escape latencies were recorded over five consecutive days. On the first day, no significant differences in escape latencies were observed across experimental groups, indicating comparable baseline performance. However, a pronounced difference in escape latencies emerged between Aβ-injected mice and saline-treated controls from day 2 onward. Notably, mice treated with cP1P and P1P (0.1 and 1 mg/kg) exhibited a significant improvement in escape latency, indicative of enhanced working memory performance during the training sessions (Fig. 1B, F). The overall reduction in escape latency across sessions confirmed successful maze learning in the experimental groups. Swimming speed analysis was also performed, and the results showed no discernible differences between the groups, suggesting that disparities in water maze performance were not caused by motor limitations (Fig. 1C, G). On the sixth day, during the probe test, Aβ-treated mice exhibited fewer crossings into the target quadrant than vehicle-treated controls, indicating impaired spatial memory. Conversely, treatment with S1P analogs in a dose-dependent manner significantly increased the number of crossings into the target quadrant (Fig. 1D, H), reflecting improved spatial memory retention. Exploratory behavior and working memory were further assessed using the Y-maze test. Aβ-treated mice displayed significantly reduced spontaneous alternations compared to control animals, demonstrating impaired working memory. Strikingly, treatment with cP1P and P1P S1P effectively reversed these deficits, as evidenced by a significant improvement in spontaneous alternation performance and increased novel arm exploration (Fig. 1E, I). The behavioral analyses indicate that cP1P and P1P administration mitigates Aβ-induced cognitive impairments, effectively preserving spatial and working memory. These findings suggest the neuroprotective potential of cP1P and P1P in ameliorating memory-associated deficits in Aβ-treated mice.

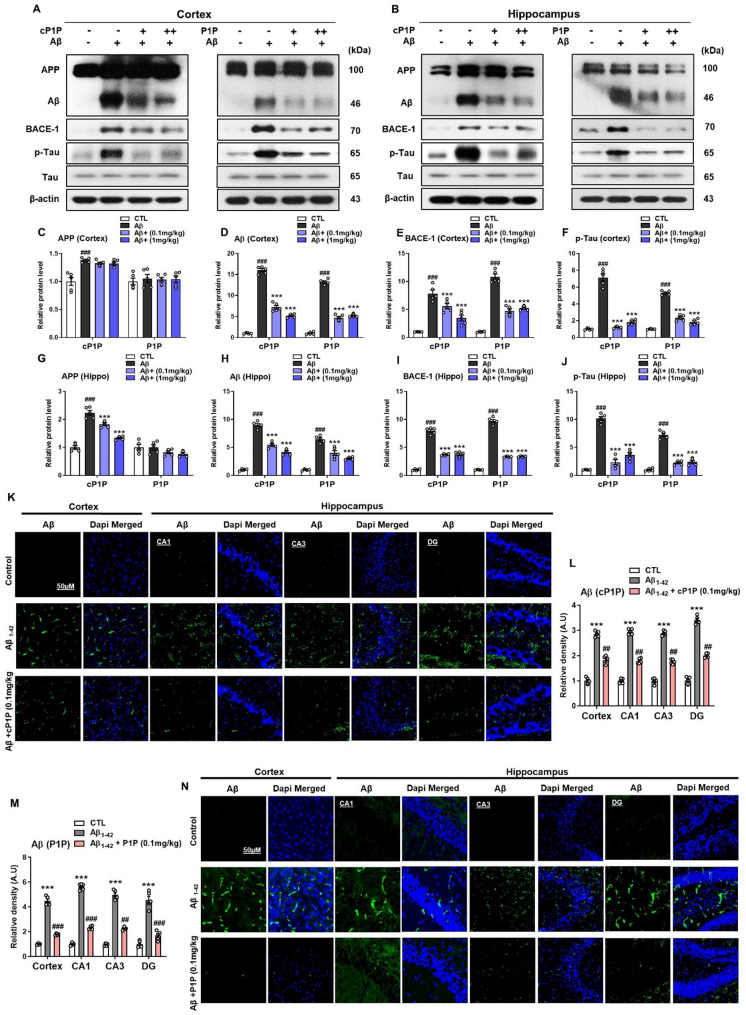

Reduction of Aβ accumulation by cP1P and P1P in Aβ-Treated mice

Aβ deposition is a hallmark pathological event in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), contributing to plaque formation and initiating a multifaceted cascade of neurotoxic processes. This phenomenon remains a key target for the development of novel therapeutic strategies aimed at mitigating the formation of these proteotoxic entities [24]. To assess whether the cP1P and P1P could attenuate Aβ accumulation, we evaluated their effects on Aβ protein levels. Mice treated exclusively with Aβ exhibited markedly elevated Aβ expression in cortical and hippocampal homogenates compared to control animals. Remarkably, treatment with cP1P and P1P significantly reduced Aβ protein expression in both the hippocampus and cortex when compared to the Aβ-treated group. Among the two analogs, cP1P at a lower dose (0.1 mg/kg) demonstrated superior efficacy in lowering Aβ levels, while P1P at a higher dose (1 mg/kg) also achieved a substantial reduction in Aβ burden. These findings suggest that both analogs are effective, with cP1P exhibiting higher potency at the lower dose. Additionally, Aβ-treated mice displayed upregulated expression of beta-secretase enzyme (BACE-1) and hyperphosphorylated tau proteins, indicative of AD-associated pathological alterations. These findings underscore the potential of S1P analogs cP1P and P1P in mitigating key molecular markers associated with Aβ pathology. The pathological alterations induced by Aβ were significantly ameliorated following S1P analog administration, as evidenced by a marked reduction in BACE-1 expression levels and tau protein hyperphosphorylation (Fig. 2A–J). Immunofluorescence analysis further corroborated these findings, revealing pronounced Aβ expression in the cortical and hippocampal CA1, CA3, and DG regions in Aβ-treated mice compared to control animals. Notably, treatment with cP1P (0.1 mg/kg) significantly reduced Aβ accumulation in control animals. Similarly, treatment with P1P (0.1 mg/kg) significantly reduced Aβ accumulation in these regions relative to vehicle-treated Aβ mice (Fig. 2K–N).

Fig. 2.

Reduction of Amyloidogenic Pathway in AD Mouse Brain by cP1P and P1P Treatments. A, B Western blot analysis demonstrated the expression of APP, Aβ, BACE-1, and phosphorylated tau (p-Tau) in the cortical region of Aβ-treated mice (n = 5). Mice administered with cP1P and P1P at doses of 0.1 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg on alternate days for 4 weeks exhibited a notable reduction in the levels of these pathological markers compared to mice treated with Aβ alone. C-J Quantitative histograms of hippocampal protein expression levels further corroborated the findings in the cortex. Both cP1P and P1P treatments significantly decreased APP, Aβ, BACE-1, and p-Tau levels in a dose-dependent manner. For normalization, β-actin served as the loading control for all Western blots. K, N Immunofluorescence micrographs revealed extensive Aβ immunoreactivity in the cortical and CA1, CA3, and DG regions of the hippocampus in Aβ-treated mice that were treated with either Aβ alone and/or Aβ plus cP1P and P1P. (n = 5). L, M Fluorescence quantification, performed using ImageJ software, and statistical analyses confirmed the results. SigmaPlot software was utilized for immunoblot quantification, while fluorescence imaging analysis was performed via ImageJ software. Representative fluorescence micrographs were captured at 10× magnification. Scale bar is 50 μm. Statistical data are presented as mean ± SEM, with significance determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Student’s t-test. #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01; ###P < 0.001 *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

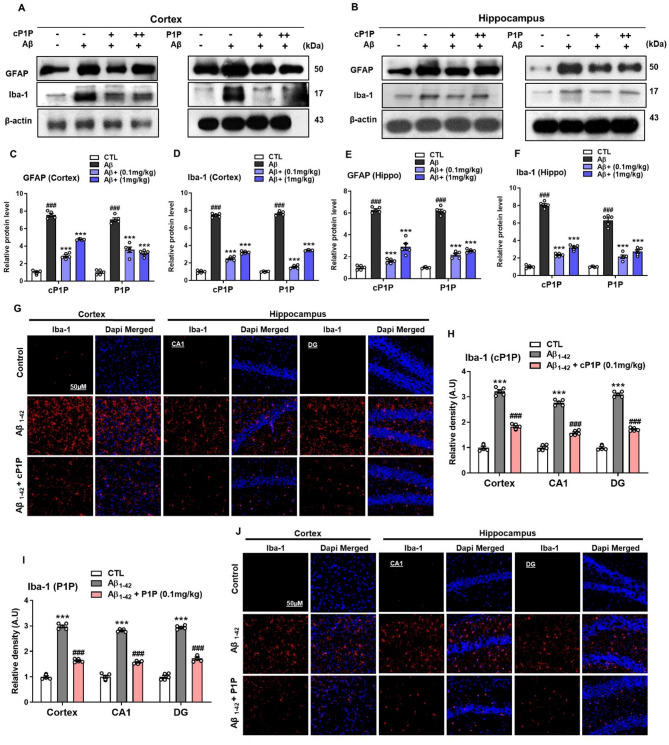

cP1P and P1P alleviate Aβ-Induced glial cell activation in mouse brain areas

Besides Aβ and NFT, neuroinflammation is considered the third most important neuropathological factor correlating with AD [25]. The accumulation of active astrocytes and, especially microglia occurs as a chronic neuroinflammatory response around the Aβ plaques [26, 27]. We, therefore, analyzed the expression of Aβ-induced glial cell activation. Aβ treatment in the mouse brain showed increased expression of astrocytes and microglia as revealed by high expression of GFAP and Iba-1 proteins in brain homogenates of the hippocampus and cortical regions. However, significantly reduced GFAP and Iba-1 protein expression could be found in all groups treated with cP1P and S1P (0.1 mg/kg, 1 mg/kg) (Fig. 3A-F). The decrease in GFAP and Iba-1 expression was more prominent at lower dose concentrations (0.1 mg/kg) in the cP1P-treated group. Aβ-induced microgliosis was observed in Aβ-treated mice, as indicated by increased Iba-1 immunoreactivity in the hippocampal and cortical regions. This effect was significantly attenuated following cP1P and P1P across all groups. (Fig. 3G-J). Together, these results illuminate that cP1P and P1P treatments could rescue the brain inflammatory status and improve AD pathology probably through mechanisms that may alter the abnormal neuroinflammatory responses.

Fig. 3.

Effects of cP1P and P1P on increased gliosis in Aβ-treated mouse brains. A, B Representative western blots analysis for expression of the Iba-1 (a marker of microglia) and GFAP (a marker of astrocytes) from cortex and hippocampus homogenates of the mice that were treated with Aβ alone and Aβ plus cP1P and P1P (0.1 and 1 mg/kg) on each alternate day for 4 weeks (n = 5). C-F Histograms showing the expression levels of GFAP and Iba-1 in Aβ-treated mice hippocampus that were treated with cP1P and P1P at doses of 0.1 and 1 mg/kg on each alternate day for 4 weeks. The same immunoblot membranes were reprobed with beta-actin as loading control. Sigma gel software for the quantification of immunoblots. G, J Representative fluorescence images of Iba-1 immunoreactivity in the cortex and CA1 and DG regions of the hippocampus that were treated with either Aβ alone and/or Aβ plus cP1P and P1P (n = 5). H, I Fluorescence images were analyzed via ImageJ software. Magnification 10X. Scale bar is 50 μm. The values were calculated as a mean ± SEM. #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01; ###P < 0.001; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by student test

cP1P and P1P reduces Aβ-Instigated neuroinflammatory pathological elements in mouse brains

The Gilas assembly, mainly microglia in proximity to Aβ plaque, is known to release various proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α and IL-1β. TNF-α, key neuroinflammatory molecules, activates various signal transduction pathways including NFκB, and is associated with different neurological disorders [28–30]. We examined whether the reduced gliosis is associated with decreased expression of TNF-α and other neuroinflammatory elements. As expected, the mice treated with Aβ and with vehicle only displayed elevated expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and p-NFκB in the hippocampal and cortical homogenates in comparisons to control mice. In contrast, the treatment with cP1P and P1P significantly abolished the increased TNF-α, IL-1β, and p-NFκB protein expression in these brain regions (Fig. 4A-H). Herein, we observed the concentration-dependent inhibition of the inflammatory markers with the effects of cP1P and P1P. The cP1P at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg was more effective compared to 1 mg/kg. However, P1P was more significant at a dose of 1 mg/kg. These results demonstrate that Aβ mediates its detrimental activity through the release of various inflammatory cytokines probably through Gliosis and could be significantly ameliorated when treated with S1P analogs cP1P and P1P. A recent study provides evidence that FTY720, an S1P analog was significantly effective in inhibiting the Aβ-induced inflammatory response in an animal model [31].

Fig. 4.

Treatment of cP1P and P1P inhibited inflammatory response in Aβ-treated mouse brains. A, B Representative western blots analysis for expression of the p-NFκB, TNF-α, and IL-1β from cortex and hippocampus homogenates of the mice that were treated with Aβ alone and Aβ plus cP1P and P1P (0.1 and 1 mg/kg) on each alternate day for 4 weeks (n = 5). C-H Histograms showing the expression levels of p-NFκB, TNF-α, and IL-1β in Aβ-treated mice hippocampus that were treated with cP1P and P1P at doses of 0.1 and 1 mg/kg. The same immunoblot membranes were reprobed with beta-actin as loading control. Sigma gel software for the quantification of immunoblots. The values were calculated as a mean ± SEM. #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01; ###P < 0.001; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by student test

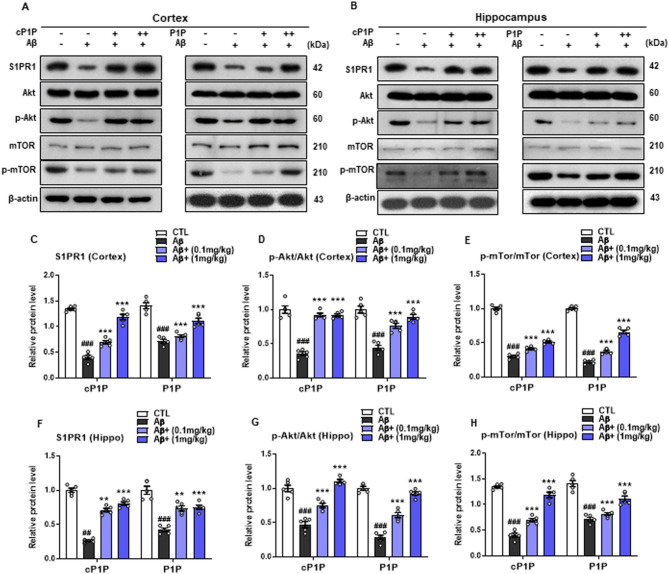

cP1P and P1P treatment counteracts Aβ-induced suppression of Akt/mTOR signaling

Aβ1–42 inhibits the survival-associated Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in an AD mice model. Therefore, we conducted immunoblot analysis for S1PR1, p-Akt, and p-mTOR to assess the effects of cP1P and P1P. Aβ1–42-treated mice showed reduced expression of S1PR1, p-Akt, and p-mTOR compared to the control group. However, treatment with cP1P and P1P (0.1 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg) mitigated the toxic effects of Aβ1–42, significantly increasing the expression of S1PR1, p-Akt, and p-mTOR compared to the Aβ1–42-treated group alone (Fig. A-H). These findings suggest that cP1P and P1P robustly activate the Akt/mTOR pathway in Aβ1–42-treated mice. Figure 5.

Fig. 5.

Treatment of cP1P and P1P abrogates Aβ-induced suppression of Akt/mTOR signaling in Aβ-treated mouse brains. A, B Representative western blots analysis for expression of the S1PR1, p-Akt, and p-mTOR from cortex and hippocampus homogenates of the mice that were treated with Aβ alone and Aβ plus cP1P and P1P (0.1 and 1 mg/kg) on each alternate day for 4 weeks (n = 5). C-H Histograms showing the expression levels of S1PR1, p-Akt, and p-mTOR in Aβ-treated mice hippocampus that were treated with cP1P and P1P at doses of 0.1 and 1 mg/kg. The same immunoblot membranes were reprobed with beta-actin as loading control. Sigma gel software for the quantification of immunoblots. The values were calculated as a mean ± SEM. #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01; ###P < 0.001; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by student test

cP1P and P1P reduce the expression of Aβ-mediated stress and apoptotic markers

C-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), a stress kinase is involved in multiple pathological events, including gene expression, cell proliferation, and apoptosis in brain injury and AD mouse models [32]. Similarly, the expression of pro-apoptotic genes, including p-JNK, caspase 3, and PARP1, were examined with increased expression of Aβ-treated mice, suggesting an increase in neuronal cell death. However, treatment with cP1P significantly reduced the expression of p-JNK in the cortex and hippocampal region. The levels of caspase 3 and PARP1 were also decreased considerably in cP1P-treated mice. The P1P-treated mice also showed a significantly reduced expression of p-JNK, caspase 3, and PARP1 in both hippocampal and cortical brain homogenates (Fig. 6A-H). It was further interesting to observe the more significant reduction in the above inflammatory markers at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg of cP1P. However, the P1P at a dose of 1 mg/kg more profoundly inhibited the inflammatory mediators. Moreover, the immunofluorescence of brain cortical, and hippocampal CA1 and DG regions of P1P treated Aβ-infused mice also visualized decreased expression of caspase-3 when compared to alone Aβ treated mice (Fig. 6I-L).

Fig. 6.

cP1P and P1P protected against Aβ-induced apoptosis. A, B Representative western blots analysis for expression of the p-JNK, caspase 3, and PARP1 from cortex and hippocampus homogenates of the mice that were treated with Aβ alone and Aβ plus cP1P and P1P (0.1 and 1 mg/kg) on each alternate day for 4 weeks (n = 5). C-H Histograms showing the expression levels of p-JNK, caspase 3, and PARP1 in Aβ-treated mice hippocampus that were treated with cP1P and P1P at doses of 0.1 and 1 mg/kg. The same immunoblot membranes were reprobed with beta-actin as a loading control. Sigma gel software for the quantification of immunoblots. I, L Representative fluorescence images of Casp-3 immunoreactivity in the cortex and CA1 and DG region of the hippocampus that were treated with either Aβ alone and/or Aβ plus cP1p and P1P (n = 5). J, K Fluorescence images were analyzed via ImageJ software. Magnification 10X. Scale bar is 50 μm. The values were calculated as a mean ± SEM. #P < 0.05; ## P < 0.01; ### P < 0.001; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by student test

cP1P and P1P improved Aβ-Induced synaptotoxicity in adult mouse cortex and hippocampus

Amyloid-β oligomers are considered principal mediators in causing synaptic plasticity and memory impairment in AD [33]. The AβOs intracerebroventricular injection has been successfully used as a neurological insult causing synapse loss, neuronal dysfunction, and cognitive deficit. Synapse transmission is important for neuronal function and its loss is also one of the pathological contributing factors and correlates of the extent of AD-associated dementia [34]. AD brain represents low levels of pre-and post-synaptic proteins [35, 36] and intracerebral ventricular Aβ infusion in mice previously has been demonstrated to reduce the pre- and post-synapse protein expression [37, 38]. Supporting this notion here we show that Aβ is associated with downregulated synaptic pathology, by decreasing the levels of presynaptic SNAP25, Syntaxin, and postsynaptic PSD-95 protein in the cortex and hippocampal brain regions of Aβ-injected mice. Conversely, the administration of cP1P and P1P attenuated Aβ-induced synapse loss and improved synaptic dysfunction and neurotransmission (Fig. 7A-H). To strengthen the immune blot results, we conducted the immunofluorescence analysis of PSD-95 and Syntaxin. The expression of PSD-95 and Syntaxin were reduced in Aβ-treated mice. Interestingly, the cP1P and P1P administration improved synaptic function (Fig. 7I-N).

Fig. 7.

cP1P and P1P enhanced Aβ-Induced Synaptotoxicity in Aβ-treated mouse brains. A, B Representative western blots analysis for expression of the PSD-95, SNAP25, and Syntaxin from cortex and hippocampus homogenates of the mice that were treated with Aβ alone and Aβ plus cP1P and P1P (0.1 and 1 mg/kg) on each alternate day for 4 weeks (n = 5). C-H Histograms showing the expression levels of PSD-95, SNAP25, and Syntaxin in Aβ-treated mice hippocampus that were treated with cP1P and P1P at doses of 0.1 and 1 mg/kg. The same immunoblot membranes were reprobed with beta-actin as loading control. Sigma gel software for the quantification of immunoblots. I, N Representative fluorescence images of PSD-95 (green) and Syntaxin (red) immunoreactivity in the cortex and DG region of the hippocampus that were treated with either Aβ alone and/or Aβ plus cP1P and P1P (n = 5). J-M Fluorescence images were analyzed via ImageJ software. Magnification 10X. Scale bar is 50 μm. The values were calculated as a mean ± SEM. #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01; ###P < 0.001; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by student test

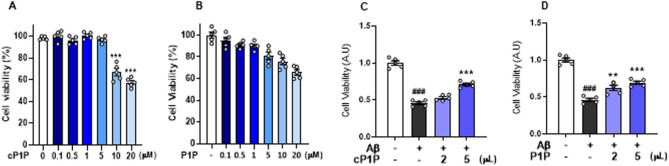

The effect of cP1P and P1P on cell viability

The cytotoxicity of cP1P and P1P was assessed in the mouse-immortalized HT22 neuronal cell line using an MTT assay. Six different concentrations (0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, and 20 µM) of each compound were tested to evaluate their effects on cell viability. The results revealed a dose-dependent decrease in cell viability at concentrations of 10 and 20 µM for both compounds (Fig. 8A, B). Subsequently, cells were treated with Aβ to investigate the protective effects of cP1P and P1P at concentrations of 2 µM and 5 µM. Treatment with Aβ significantly reduced cell viability. However, both cP1P and P1P at doses of 2 µM and 5 µM significantly enhanced cell viability in Aβ-treated HT22 cells (Fig. 8C, D).

Fig. 8.

Effects of cP1P and P1P on cell viability. A, B The representative histograms show the effects of cP1P and P1P on cell viability in HT22 cells at various concentrations. Both compounds significantly reduced cell viability at concentrations of 5 µM and 10 µM. C, D The histograms illustrate the cell viability of HT22 cells treated with 2 µM and 5 µM concentrations of cP1P and P1P, in the presence or absence of Aβ. The data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05

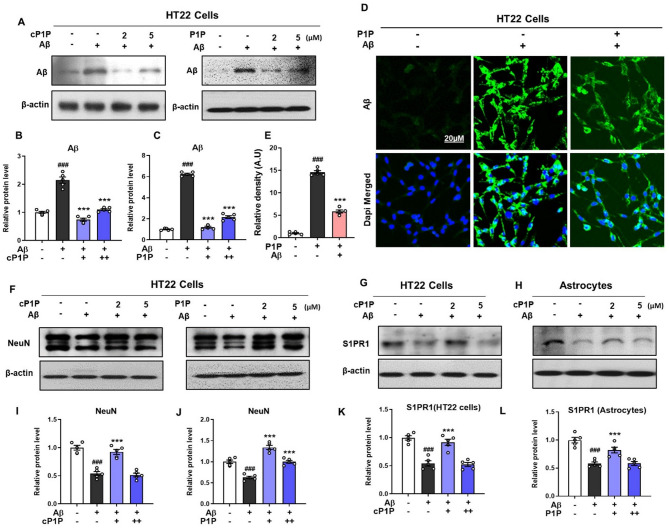

cP1P and P1P treatment attenuated the amyloidogenic pathway in Aβ-treated HT22 and astrocyte cells

In vitro studies using the HT22 hippocampal cell line pre-treated with cP1P and P1P (02 µM and 05 µM) demonstrated a significant decline in Aβ expression. Among the tested concentrations, cP1P at 2 µM was more effective in mitigating Aβ accumulation. These findings were substantiated through immunoblot and immunofluorescence analyses (Fig. 9A–E). NeuN, a neuron-specific marker widely used to assess neuronal survival, was analyzed via Western blot. Aβ treatment reduced NeuN expression, whereas cP1P and P1P treatment effectively restored its levels (Fig. 9F, I, J). Previously, Takasugi et al. reported that the S1P receptor modulator FTY720 significantly reduces Aβ levels [39]. To determine whether the observed reductions were receptor-mediated, we examined S1PR1 expression via western blot in HT22 cells and astrocytes. Aβ treatment resulted in decreased S1PR1 expression in both cell types. However, this reduction was markedly reversed following cP1P treatment, indicating potential signaling through S1PR1 (Fig. 9G, H, K, L). These findings strongly suggest that the attenuation of AD-associated pathology is mediated through receptor-dependent mechanisms in the brain. In summary, our results demonstrate that S1P analog, particularly cP1P, effectively prevent Aβ accumulation both in vivo and in vitro, reduce tau hyperphosphorylation, and ameliorate key pathological hallmarks of AD in pre-Aβ intracerebroventricularly injected mice.

Fig. 9.

Treatment of cP1P and P1P reduced amyloidogenic pathway in Aβ-treated HT22 and Astrocyte cells. A Representative western blot analysis of Aβ expressed in Aβ-treated HT22 cells that were treated with cP1P and P1P at a dose of 02 µM and 05 µM. (B, C) Histograms showing the expression levels of Aβ in Aβ-treated HT22 cells that were treated with cP1P and P1P at a dose of 02 µM and 05 µM. For each blot, the beta-actin was used as a loading control. D, E Representative fluorescence micrographs of Aβ immunoreactivity in HT22 cells treated with Aβ and P1P. F, I, J Representative western blot analysis and corresponding histograms showing NeuN expression in Aβ-treated HT22 cells following treatment with cP1P and P1P at doses of 02 µM and 05 µM (G, H, K, L) Representative western blot analysis of S1PR1 expressed in Aβ-treated HT22 cells and in astrocytes treated with cP1P at a dose of 02 µM and 05 µM. To quantify immunoblots, sigma gel software was used and fluorescence micrographs were analyzed via ImageJ software. Magnification 20X. Scale bar is 20 μm. The values were calculated as a mean ± SEM. #P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01; ###P < 0.001; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA followed by student test

Discussion

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a multifaceted neurodegenerative disorder characterized by aberrant amyloid-beta (Aβ) production, tau hyperphosphorylation, and chronic neuroinflammation [40]. While these pathological hallmarks are well-documented, recent evidence highlights the significant role of dysregulated brain lipid metabolism in the progression of AD. Notably, alterations in sphingolipid pathways have emerged as key contributors to AD pathogenesis. AD brains exhibit reduced levels of sphingosine kinase-1 (SphK1) and elevated expression of sphingosine-1 phosphate lyase (SPL) [41], resulting in decreased sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) levels in a region-specific manner during disease progression [10]. This lipid imbalance is accompanied by diminished sphingomyelin levels in human AD brains [42] and transgenic animal models simulating early-onset familial AD [41]. The reduction in sphingosine kinase-1 (SphK1) activity and/or the elevated expression of sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase (SPL), combined with enhanced sphingomyelin degradation, may collectively contribute to an increase in cerebral ceramide levels. Ceramide and its sphingolipid derivatives are well-recognized for their roles in promoting cellular arrest and apoptosis, in stark contrast to sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), which facilitates cellular differentiation, proliferation, and survival. This dichotomy underscores two fundamentally opposing mechanisms of cellular fate: senescence or apoptosis versus survival and regeneration. The balance between these pathways appears to hinge on the ceramide-S1P axis, with an imbalance favoring ceramide accumulation tipping the scales toward neuronal apoptosis and synaptic dysfunction. This highlights the importance of maintaining a homeostatic equilibrium within the ceramide-S1P biostat to ensure cellular resilience and functional integrity [43]. An imbalance in the ceramide-S1P axis within the brain may result in neuronal cell death and synaptic dysfunction, thereby contributing to the progression of neurodegenerative disorders. The development of novel S1P analogs and modulators targeting sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors (S1PRs) represents a promising therapeutic strategy to mitigate Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. In this study, we explored the efficacy of two S1P analogs, cP1P and P1P, administered in a dose-dependent manner, using an Aβ-induced Alzheimer’s disease (AD) mouse model. To assess and contrast the neuroprotective effects of two structurally related S1P analogues, cP1P and P1P, we chose them. Even at a lower dose (0.1 mg/kg), cP1P consistently showed larger effects than P1P, despite both drugs reducing Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. This discrepancy might be the result of differences in their potency for downstream signaling, stability, or receptor-binding affinity. Because cP1P provided more significant behavioral and molecular improvements, we decided to focus our investigation on receptor involvement in the cP1P-treated groups. This made cP1P a better option for mechanistic research. However, it is impossible to rule out the potential that P1P acts by different or comparable routes, and more research is necessary to understand P1P’s receptor-mediated mechanisms fully. We sought to give a comparative assessment that acknowledges the activity of P1P as a related analog while highlighting the therapeutic potential of cP1P by incorporating both molecules into our experimental design. Our results provide compelling evidence for the potential of S1P analogs as disease-modifying agents in the treatment of AD.

Extensive evidence emphasizes the crucial role of Aβ metabolism in the initiation and progression of AD [44, 45]. Key proteins involved in this process, including β-secretase (BACE1), γ-secretase, and amyloid precursor protein (APP), are integral membrane components whose activities are profoundly influenced by the sphingolipid and cholesterol composition of membrane lipid rafts [4, 5, 46]. The Aβ-injected mouse model was selected because it is a well-established and widely used model that enables reproducible induction of Aβ pathology, oxidative stress, and cognitive impairment within a short experimental timeframe. This model is particularly useful for evaluating the neuroprotective effects of novel compounds such as cP1P and P1P. Notably, Aβ has been shown to activate sphingomyelinases within lipid rafts, catalyzing the hydrolysis of sphingomyelins into elevated levels of ceramide [7]. Ceramide levels are notably elevated during the early stages of AD [47] and have been implicated in the stabilization of BACE1 expression [48]. Similarly, it has been reported that reduced expression of sphingosine kinase 1 (SphK1) and increased expression of the sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) degrading enzyme, sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase (SPL), are closely associated with Aβ deposition [41]. Interestingly, the functional antagonist of the S1P1 receptor, Fingolimod, has demonstrated significant efficacy in reducing Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels, as well as the overall Aβ burden, in 3-month-old 5xFAD mice [49]. Consistent with these findings, earlier studies have shown that Fingolimod and KRP203, both S1PR1 modulators, effectively reduced Aβ production in primary neuronal cells derived from mice [39]. However, in APP transgenic mouse models, treatment with Fingolimod resulted in a decrease in Aβ40 levels but paradoxically led to an increase in Aβ42 levels within the brain. In the current study, we observed pronounced overexpression of Aβ in both the Aβ-induced AD mouse model and the HT22 mouse hippocampal neuronal cells. This increased Aβ expression was accompanied by a marked upregulation of the BACE1 enzyme, corroborating the toxic effects of Aβ in disrupting sphingolipid homeostasis. Furthermore, tau proteins exhibited hyperphosphorylation as a downstream consequence of the elevated Aβ accumulation. Notably, pharmacological intervention with cP1P significantly ameliorated these pathological phenotypes. The findings suggest that the S1P analog cP1P effectively mitigated abnormal APP processing and Aβ accumulation, likely through activation of S1PR1 signaling pathways (Fig. 2). To validate this hypothesis, we assessed S1PR1 expression levels in HT22 cells and astrocytes. Aβ-treated cells demonstrated a significant decline in S1PR1 expression. However, treatment with cP1P (2 µM) dramatically restored S1PR1 levels, suggesting the involvement of S1PR1-mediated signaling in both neuronal cells and astrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 1). These observations indicate that cP1P not only modulates S1PR1 expression but also highlights the impact of Aβ on astrocytic S1PR1, further emphasizing the therapeutic potential of S1P analogs in addressing Aβ-induced neurotoxicity.

Chronic neuroinflammation, characterized by sustained glial cell activation, represents a critical neuropathological hallmark of numerous neurodegenerative disorders, including AD [50]. Neuroinflammation is recognized as the third most significant neuropathological factor associated with AD [25]. Consistent with this, our study demonstrated that the novel sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) analogs, administered in two doses (with the lower dose exhibiting greater potency), effectively attenuate neuroinflammation. This was evidenced by a marked reduction in the protein expression levels of key inflammatory markers, including TNF-α, NF-κB, and IL-1β. Moreover, the anti-inflammatory properties of these novel S1P derivatives were accompanied by anti-apoptotic effects and the prevention of synaptic dysfunction in an adult mouse model. These findings align with prior research, which has reported that Aβ injection into the mouse brain induces apoptotic neurodegeneration [37, 51]. Similarly, our results show increased expression levels of p-JNK, cleaved caspase-3, and PARP-1 in Aβ-treated mouse brains. Moreover, treatment with cP1P and P1P significantly modulated the mitochondrial system, leading to a reduction in apoptotic markers. These findings were corroborated by enhanced caspase-3 immunoreactivity in the cortex and hippocampal regions, which was markedly diminished in mice treated with cP1P and P1P. Notably, in most instances, the treatment with cP1P at a dose of 0.1 mg/kg exhibited a more pronounced effect in reducing the expression of these apoptotic markers. These observations align with previous post-mortem studies and experimental research, which have linked sphingosine-1-phosphate-related signaling to neuronal cell death [52]. The aforementioned findings prompted us to investigate the effects of these novel S1P analogs cP1P and P1P on Aβ-induced synaptic dysfunction and behavioral impairments. Spatial memory and cognitive deficits are well-established hallmarks of AD pathogenesis. Aβ, known as a proteotoxic agent, has previously been shown to induce neural damage in mice, leading to significant cognitive deficits and memory impairment [38, 53].

S1P, a neuroprotective sphingolipid second messenger, plays a crucial role in memory formation by enhancing depolarization-evoked glutamate release through activation of the S1PR1 receptor. Notably, we observed abnormally low levels of key synaptic proteins, including PSD-95, SNAP-25, and Syntaxin, in brain homogenates from Aβ-treated mice. However, a remarkable reversal of these deficits was observed following treatment with cP1P and P1P. Additionally, we noted a significant decline in behavioral performance in Aβ-treated mice, as evidenced by increased escape latency, reduced crossing, and decreased spontaneous alternation behavior. These behavioral impairments were notably ameliorated in mice treated with cP1P and P1P, indicating a profound effect of these S1P analogs on both synaptic function and cognitive performance. Previous studies have demonstrated that S1P regulates neurotransmitter release and that the knockdown of S1P leads to altered long-term potentiation (LTP), a process that can be modulated by the administration of S1P in animal models [12, 54]. In summary, this study presents novel insights into the drug-like properties of S1P analogs in mitigating Aβ-induced cognitive decline, working memory deficits, neuroinflammation, and associated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of AD. Even though both groups received the same amount of exogenous Aβ, the mice treated with cP1P and P1P had a lower Aβ burden, which is probably due to improved Aβ clearance and decreased aggregation. According to earlier research, these effects might be mediated by glial activity modulation and inflammatory response inhibition. Moreover, these innovative S1P analog derivatives demonstrated efficacy in counteracting Aβ-induced inflammation and other AD-related neuropathological complications in vitro. Further detailed mechanistic investigations are essential to fully explore the therapeutic potential of these novel compounds in AD and other neurological disorders. Collectively, our findings provide a preclinical “proof of concept” that targeting deregulated sphingosine-1-phosphate may represent a promising strategy for the development of disease-modifying therapies for AD.

Conclusion

The findings of this study demonstrate the neuroprotective potential of S1P analogs, cP1P and P1P, in mitigating Aβ-induced neuropathology. By inhibiting the amyloidogenic pathway, reducing hyperphosphorylated tau, modulating glial activation mediated neuroinflammation, and regulated Akt/mTOR signaling, these analogs effectively attenuated key pathological hallmarks of AD. Moreover, their ability to preserve mitochondrial function, restore synaptic markers, and improve cognitive and memory functions highlights their therapeutic promise. These results suggest that the novel cP1P and P1P could serve as effective candidates for developing novel treatments for neurodegenerative diseases, particularly AD. Further investigations are needed to elucidate their precise mechanisms and long-term efficacy.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Abbreviations

- S1P

Sphingosine 1-phosphate

- P1P

Phytosphingosine-1-phosphate

- cP1P

Cyclic phytosphingosine-1-phosphate

- NFKB

Nuclear factor kappa B

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- FITC

Fluorescein Isothiocyanate

- PBS

Phosphate buffer saline

- p-JNK

Phospho- C-jun N-terminal Kinase

- PARP-1

Poly[ADP-ribose] polymerase 1

- Iba-1

Ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- SNAP-25

Synaptosomal-associated protein 25

- Syn

Syntaxin

- PSD-95

Post synaptic density protein-95

- NeuN

Neuronal nuclear antigen

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

Authors’ contributions

K.C and R.A designed the model, wrote the manuscript, and helped in sample collection; T.J.P provided critical suggestions in manuscript writing while helping in statistical analysis; M.W.K performed the confocal microscopy; H.J.L and S.A performed the Western blot experiments; M.O.K. supervised, organized, provided critical instructions, and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the paper and provided feedback. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Bio&Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean Government (MSIT) (RS-2024-00441331).

Data availability

The authors declare that the data presented in this study will be given upon request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and Consent Participate

This study was carried out in animals following approved guidelines (Approval ID: 125, Code: GNU-200331-M0020) by the Animal Ethics Committee (IACUC) of the Division of Applied Life Science, Gyeongsang National University, South Korea

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Kyonghwan Choe and Riaz Ahmad contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Tae Ju Park, Email: taeju.park@einsteinmed.edu.

Myeong Ok Kim, Email: mokim@gnu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Singh SK, et al. Overview of alzheimer’s disease and some therapeutic approaches targeting Abeta by using several synthetic and herbal compounds. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2016;2016:p7361613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polanco JC, et al. Amyloid-beta and Tau complexity - towards improved biomarkers and targeted therapies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(1):22–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow VW, et al. An overview of APP processing enzymes and products. Neuromolecular Med. 2010;12(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vetrivel KS, Thinakaran G. Membrane rafts in Alzheimer’s disease beta-amyloid production. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801(8):860–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grosgen S, et al. Role of amyloid beta in lipid homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801(8):966–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cutler RG, et al. Involvement of oxidative stress-induced abnormalities in ceramide and cholesterol metabolism in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(7):2070–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jana A, Pahan K. Fibrillar amyloid-beta-activated human astroglia kill primary human neurons via neutral sphingomyelinase: implications for alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2010;30(38):12676–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haughey NJ, et al. Roles for dysfunctional sphingolipid metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease neuropathogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801(8):878–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rivera J, Proia RL, Olivera A. The alliance of sphingosine-1-phosphate and its receptors in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(10):753–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Couttas TA, et al. Loss of the neuroprotective factor sphingosine 1-phosphate early in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prager B, Spampinato SF, Ransohoff RM. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling at the blood-brain barrier. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21(6):354–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kajimoto T, et al. Involvement of sphingosine-1-phosphate in glutamate secretion in hippocampal neurons. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(9):3429–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimura A, et al. Essential roles of sphingosine 1-phosphate/S1P1 receptor axis in the migration of neural stem cells toward a site of spinal cord injury. Stem Cells. 2007;25(1):115–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He X, et al. Deregulation of sphingolipid metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31(3):398–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Pardo A, et al. Defective sphingosine-1-phosphate metabolism is a druggable target in huntington’s disease. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maglione V, et al. Impaired ganglioside metabolism in Huntington’s disease and neuroprotective role of GM1. J Neurosci. 2010;30(11):4072–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soliven B, Miron V, Chun J. The neurobiology of sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling and sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulators. Neurology. 2011;76(8 Suppl 3):S9-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schurer NY, Plewig G, Elias PM. Stratum corneum lipid function. Dermatologica. 1991;183(2):77–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickson RC. Sphingolipid functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: comparison to mammals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:27–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ali T, et al. Anthocyanin-Loaded PEG-Gold nanoparticles enhanced the neuroprotection of anthocyanins in an Abeta1-42 mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(8):6490–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rehman SU, et al. Anthocyanins reversed d-galactose-induced oxidative stress and neuroinflammation mediated cognitive impairment in adult rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(1):255–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarthy KD. and De Vellis, Preparation of separate astroglial and oligodendroglial cell cultures from rat cerebral tissue.J Cell Biol. 1980;85(3):890–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Schildge S et al. Isolation Cult Mouse Cortical Astrocytes. J Vis Exp. 2013(71):50079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Shukla M, et al. Mechanisms of melatonin in alleviating Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(7):1010–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graham WV, Bonito-Oliva A, Sakmar TP. Update on Alzheimer’s disease therapy and prevention strategies. Annu Rev Med. 2017;68:413–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chun H, Lee CJ. Reactive astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease: a double-edged sword. Neurosci Res. 2018;126:44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meda L, et al. Activation of microglial cells by beta-amyloid protein and interferon-gamma. Nature. 1995;374(6523):647–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olmos G. J. Llado 2014 Tumor necrosis factor alpha: a link between neuroinflammation and excitotoxicity. Mediators Inflamm 2014 p861231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamamoto M, et al. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha regulate amyloid-beta plaque deposition and beta-secretase expression in Swedish mutant APP Transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(2):680–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leal MC, et al. Interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha: reliable targets for protective therapies in parkinson’s disease? Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kolahdooz Z, et al. Sphingosin-1-phosphate receptor 1: a potential target to inhibit neuroinflammation and restore the sphingosin-1-phosphate metabolism. Can J Neurol Sci. 2015;42(3):195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rehman SU, et al. Inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase protects against brain damage and improves learning and memory after traumatic brain injury in adult mice. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28(8):2854–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hampel H. Amyloid-beta and cognition in aging and alzheimer’s disease: molecular and neurophysiological mechanisms. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33(Suppl 1):S79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller UC, Deller T, Korte M. Not just amyloid: physiological functions of the amyloid precursor protein family. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18(5):281–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terry RD, et al. Physical basis of cognitive alterations in Alzheimer’s disease: synapse loss is the major correlate of cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 1991;30(4):572–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pham E, et al. Progressive accumulation of amyloid-beta oligomers in alzheimer’s disease and in amyloid precursor protein Transgenic mice is accompanied by selective alterations in synaptic scaffold proteins. FEBS J. 2010;277(14):3051–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmad A, et al. Neuroprotective effect of Fisetin against Amyloid-Beta-Induced Cognitive/Synaptic Dysfunction, Neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration in adult mice. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(3):2269–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lourenco MV, et al. TNF-alpha mediates PKR-dependent memory impairment and brain IRS-1 Inhibition induced by alzheimer’s beta-amyloid oligomers in mice and monkeys. Cell Metab. 2013;18(6):831–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takasugi N, et al. FTY720/fingolimod, a sphingosine analogue, reduces amyloid-beta production in neurons. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e64050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Congdon EE, Sigurdsson EM. Tau-targeting therapies for alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018. 10.1038/s41582-018-0013-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ceccom J, et al. Reduced sphingosine kinase-1 and enhanced sphingosine 1-phosphate lyase expression demonstrate deregulated sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soderberg M, et al. Lipid composition in different regions of the brain in alzheimer’s disease/senile dementia of alzheimer’s type. J Neurochem. 1992;59(5):1646–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bryan L. Regulation and functions of sphingosine kinases in the brain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1781(9):459–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.St George-Hyslop PH, Petit A. Molecular biology and genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. CR Biol. 2005;328(2):119–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanzi RE. The genetics of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puglielli L, Tanzi RE, Kovacs DM. Alzheimer’s disease: the cholesterol connection. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(4):345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Han X, et al. Substantial sulfatide deficiency and ceramide elevation in very early Alzheimer’s disease: potential role in disease pathogenesis. J Neurochem. 2002;82(4):809–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Puglielli L, et al. Ceramide stabilizes beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 and promotes amyloid beta-peptide biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(22):19777–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aytan N, et al. Fingolimod modulates multiple neuroinflammatory markers in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Glass CK, et al. Mechanisms underlying inflammation in neurodegeneration. Cell. 2010;140(6):918–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ali T, et al. Natural dietary supplementation of anthocyanins via PI3K/Akt/Nrf2/HO-1 pathways mitigate oxidative stress, neurodegeneration, and memory impairment in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(7):6076–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chakrabarti SS, et al. Ceramide and Sphingosine-1-Phosphate in cell death pathways: relevance to the pathogenesis of alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2016;13(11):1232–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Balducci C, Forloni G. Vivo application of beta amyloid oligomers: a simple tool to evaluate mechanisms of action and new therapeutic approaches. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(15):2491–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kanno T, et al. Regulation of synaptic strength by sphingosine 1-phosphate in the hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2010;171(4):973–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data presented in this study will be given upon request from the corresponding author.