Abstract

Sepsis is a severe systemic inflammatory syndrome and one of the leading causes of global morbidity and mortality. Preclinical studies have identified several quinoxaline-based compounds with anti-inflammatory properties, but their effects in sepsis have not been investigated. This study aimed to identify a quinoxaline derivative with anti-inflammatory properties in sepsis. Examining the inflammatory response of primary mouse macrophages to Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) revealed that 2-methoxy-N-(3-quinoxalin-2-ylphenyl)benzamide (2-MQB) is a promising molecule. It suppressed the production of several inflammatory cytokines, including Interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-12p70, Interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IFN-β, and Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Importantly, 2-MQB inhibited the transcriptional activities of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling pathways, including Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and Interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3). This was accompanied by lower expression of TLR4, Myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88), TIR Domain-containing adaptor molecule 1 (Trif), and TNF Receptor-associated factor 3 (Traf3). Additionally, 2-MQB selectively reduced the expression of genes encoding CD80, CD86, and Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). In vivo, 2-MQB improved mice survival, mitigated tissue damage in the spleen, kidney, and lung, and reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in both LPS-induced endotoxin shock and Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) models. Notably, 2-MQB decreased the numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen and inhibited TLR4 signaling pathways in LPS-induced endotoxemia. In conclusion, these results introduce the quinoxaline derivative 2-MQB as a potential therapeutic agent for sepsis by inhibiting TLR4 signaling pathways, paving the way for future clinical applications.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Quinoxaline, Inflammation, Sepsis, TLR4 pathways, Cytokines

Introduction

Sepsis and septic shock present a significant global health challenge, marked by a dysregulated host response to infection and excessive systemic inflammation. The intricate pathophysiology of these conditions, including metabolic defects, sustained hypotension, hypoperfusion, tissue injury, and organ dysfunction, leads to a high mortality rate of up to 50% [1–3]. Despite advancements in treating this severe inflammatory response, sepsis complications still result in over 10 million deaths annually [3].

The uncontrolled immune response to bacterial infection in sepsis is primarily initiated by Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling pathways. These pathways, which include Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and Interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3)-also known as Myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88)-dependent and TIR Domain-containing adaptor molecule 1 (Trif)-dependent, respectively -drive the excessive production of pro-inflammatory mediators [1, 4, 5]. Therefore, targeting TLR4 signaling pathways offers a therapeutic strategy to control the excessive immune response and its associated tissue impacts. Numerous preclinical studies have aimed to identify derivatives from various chemical groups that modulate TLR4 signaling [6–8]. This research has yielded a wealth of synthetic compounds with significant therapeutic potential for treating sepsis and septic shock by inhibiting TLR4 signaling pathways [9–11].

For example, the dihydrodiazepine 2-TDDP attenuates inflammation in septic mice by suppressing the TLR4/NF-κB and TLR4/IRF3 pathways, leading to reduced secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and reduced tissue damage [8]. Benznidazole, a nitroimidazole, mitigates inflammation in endotoxin shock by decreasing TLR4 expression, enhancing antioxidant capacity, and potentiating activation of Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) [12]. The methyloxirane Fosfomycin mitigates lung injury in septic mice through various mechanisms, including reducing the expression of TLR4, Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and P65 [13]. Dexmedetomidine, an imidazole, suppresses the production of pro-inflammatory factors by inhibiting the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB/Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) pathway and enhancing Interleukin-10 (IL-10) secretion in a sepsis model [14].

Quinoxaline, a bicyclic benzopyrazine ring, has emerged as a versatile pharmacophore in drug discovery and development owing to the diverse biological activities of its derivatives, including analgesic, antimicrobial, antitumor, and anti-inflammatory properties [15–17]. Previous reports have demonstrated the anti-inflammatory properties of quinoxaline derivatives in murine models of inflammation. A recent study has shown that the quinoxaline derivatives DEQX and OAQX exhibit anti-inflammatory potential by reducing levels of IL-1β and TNF-α in carrageenan-induced peritonitis [18]. The trifluoromethoxy quinoxaline reduces inflammatory cells, restores normal epithelial tissue, and decreases the production of IL-1β, IL-6, Interferon-γ (IFN-γ), and TNF-α in a murine model of gastric ulcer [19]. Interestingly, the natural quinoxaline alkaloid, oxymatrine, exerts anti-inflammatory effects and provides neuroprotection through Cathepsin D (CathD)-dependent inhibition of the High mobility group box 1 (HMGB1)/TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway, both in vitro and in vivo [20].

Herein, we hypothesized that synthetic quinoxaline-based derivatives have therapeutic potential in sepsis and septic shock by modulating major TLR4 signaling pathways. Using both in vitro and in vivo approaches, we introduced the quinoxaline derivative 2-methoxy-N-(3-quinoxalin-2-ylphenyl)benzamide (2-MQB) as a new anti-inflammatory molecule. In Lipopolysaccharides (LPS)-induced endotoxin shock and Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) models, 2-MQB demonstrated significant therapeutic potential. It increased survival rates, reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines, and mitigated tissue injury in vital organs. Notably, 2-MQB inhibited TLR4 signaling pathways, including NF-κB and IRF3, by reducing transcriptional activities and the expression of multiple signaling elements.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

The C57BL/6 mice were initially obtained from Charles River Laboratories in Oxford, UK, and were housed in a specific-pathogen-free facility under a 12-h light–dark cycle. The animals were provided with food and water ad libitum. All studies involving these mice were conducted in compliance with the approved protocols (ETHICS2928) by the Standing Research Ethics Committee at King Faisal University, Al Ahsa, Saudi Arabia.

Cell Culture

Peritoneal macrophages were isolated from thioglycolate-injected mice after euthanasia using isoflurane. The cells were purified using the adherence method to achieve a purity level exceeding 97%. The macrophages were then cultured in complete RPMI-1460 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco, MD, USA) at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. The LPS from E. coli O111:B4 (0.2 µg/mL; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) were used to stimulate the macrophages, either alone or in combination with 2-MQB (Mwt 355.4 g/mol; ChemDiv, CA, USA).

Serum Parameters

The ELISA kits for measuring IL-6, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 15 (Cxcl15; a mouse IL-8 homolog), IL-10, IFN-γ, and Kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1) were obtained from Wuhan Fine Biotech (Wuhan, China). Kits for measuring IL-1β, IL-12p70, IFN-β, and TNF-α were sourced from Invitrogen (MD, USA). The assay kits for lactate (Sigma-Aldrich, IL, USA), Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (FAR Diagnostic, Italy) were used according to the manufacturers’ guidelines.

Real-Time PCR

The PrimeScript® reverse transcription master mix (Takara, CA, USA) was used to synthesize cDNA. The ViiA7® quantitative real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, NY, USA) was employed to amplify cDNA using standard cycle settings. The TaqMan® Gene Expression assays (Applied Biosystems, NY, USA) were utilized for the following targets: Tlr4 (Mm00445273_m1), P50 (Mm00476361_m1), Irf3 (Mm00516784_m1), TNF receptor-associated factor (Traf3; Mm00495752_m1), MyD88 (Mm00440338_m1), Trif (Ticam1; Mm00844508_s1), H2-Ea (Major histocompatibility complex II; MhcII; Mm00772352_m1), Cd86 (Mm00444540_m1), Complement component 5a receptor 1 (C5ar1; Mm00500292_s1), Programmed death-ligand 1 (Pdl1; Mm03048248_m1), and Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1). The comparative cycle threshold Ct (ΔΔCt) method was used to calculate relative mRNA expression.

Immunoblotting

The macrophage lysates were fractionated using Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Mouse monoclonal antibodies against TLR4, MyD88, Trif, and Traf3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) and rabbit polyclonal antibodies against CD80, CD86, and PD-L1 (Proteintech, IL, USA) were used. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Proteintech, IL, USA) and HRP-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibodies against β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) were utilized. The Pierce® ECL kit (Pierce, MA, USA) was used to develop chemiluminescence signals, and ImageJ (v1.48; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij) was employed to analyze band intensities.

Plasmids and Transfection

The mouse Il6 promoter-harboring pGL3 plasmid was generously provided by Professor Tadamitsu Kishimoto from Osaka University, Japan. This plasmid was constructed as previously described [8], and mouse Ifnb1 promoter-harboring pGL3 plasmid was constructed following a modified method described earlier [21]. In brief, DNA inserts were synthesized using the following primers: forward 5’ AGATCGCCGTGTAATTCTAGAGGATCCTGAGAGTGTGTTTTGTAA-3 and reverse 5’-GCCGGCCGCCCCGACTCTAGATCCAGAGCAGAATGAGCTA-3’ for Il6 promoter, and forward 5’-AGATCGCCGTGTAATTCTAGACATTCTCACTGCAGCCTTTG-3’ and reverse 5’-GCCGGCCGCCCCGACTCTAGACCAAGGGTTGCGTAATGAAC-3’ for Ifnb1 promoter. The inserts were then cloned into the XbaI site using the In‐Fusion HD Cloning Kit (Clontech, CA, USA). The plasmids (100 ng) were introduced into macrophages using the 4D-Nucleofector electroporation device and a specific electroporation kit (Lonza, MD, USA). The Dual-Luciferase Reporter assay (Promega, WI, USA) was used to determine luciferase activities.

LPS-Induced Endotoxic Shock and CLP

The strategy to inject LPS at different doses was adopted from previous studies, with modifications to induce endotoxin shock [22, 23]. In summary, female mice (7–9 weeks old, 20–22 g) were intraperitoneally injected once with LPS at doses of 7.5 or 20 mg/kg (E. coli O111:B4; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA). The CLP surgery was performed following a modified method described previously [24]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (3%) along with an oxygen flow (3 L/min), and the cecum was exposed through a 1 cm abdominal incision. The cecum was then ligated with 4–0 sutures, punctured using a 20-gauge needle, and gently squeezed to expel a fecal droplet. The mice received a subcutaneous injection of 1 mL saline solution. Control mice underwent the same procedure except for the CLP.

The mice were then randomly divided into groups of 4–8 each. 2-MQB (1, 3, or 5 mg/kg) in a vehicle (vegetable oil) was injected intraperitoneally at 0 and 6 h after LPS challenge or CLP surgery. The mice were monitored for survival and clinical scores for 144 h. Clinical scores were determined following a modified system described previously [25]. Briefly, the system included cumulative scores based on respiratory frequency, eye condition, level of consciousness, response to stimulus, appearance, and activity; each parameter was assigned a score ranging from 0 to 2.

Histopathology and Lymphocytes Isolation

After euthanizing the mice, the spleen, kidney, and lung were excised and fixed in formaldehyde. The sectioned samples were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E; Merck, MO, USA). A histopathologist, who was blind to experimental treatments, analyzed the tissues. For lymphocyte counting, T lymphocytes (including CD4+ and CD8+) and B lymphocytes were isolated from the whole spleen. The cells were purified using the specific Magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) kit (Miltenyi Biotec, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Bacterial Load

Peritoneal lavage was collected from CLP mice by washing the peritoneal cavity with 2 mL of sterile PBS. The lavage and blood samples, taken 24 h after surgery, were serially diluted using sterile PBS (4°C). Then, 100 µL of each sample was spread on tryptic soy agar with 5% sheep blood agar (BD Biosciences, CA, USA). The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, and the colonies were counted and expressed as Colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL).

Statistics

The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical comparisons were performed using SPSS software (version 16.0, IL, USA) as follows: one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for mean values, two-way ANOVA for clinical scores, and log-rank test for survival. The experiments were conducted three times, and samples were analyzed in triplicate. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

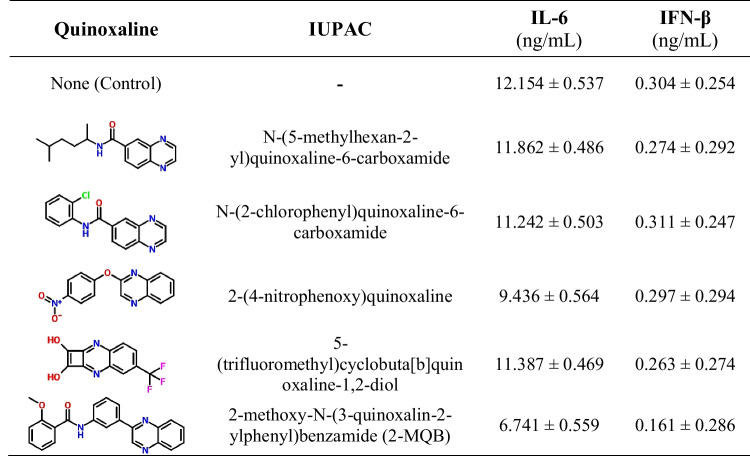

2-MQB Suppresses the Inflammatory Response in Macrophage

To identify a new quinoxaline derivative with anti-inflammatory effects, we initially selected five candidate molecules that had no previous preclinical evidence of anti-inflammatory properties. These molecules were evaluated for potential anti-inflammatory effects in LPS-stimulated macrophages by quantifying IL-6 and IFN-β levels. Among the quinoxaline compounds tested, 2-MQB (Fig. 1A) demonstrated pronounced modulation of the examined cytokine levels (Table 1). As illustrated in Fig. 1B, 2-MQB at concentrations of 10, 20, 30, and 40 µM significantly decreased the production of IL-1β, IL-6, and IFN-β. Furthermore, 2-MQB at concentrations of 20, 30, and 40 µM reduced the production of TNF-α and IFN-γ (Fig. 1C). The production of IL-12p70 was notably reduced only at the highest concentration (40 µM) (Fig. 1D). In contrast, 2-MQB did not affect IL-8 production at any of the examined concentrations (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

2-MQB suppresses LPS-induced inflammatory response in macrophages. Purified macrophages were cultured for 16 h either without (Cont.) or with LPS (0.2 µg/mL) in the absence or presence of 2-MQB at 10, 20, 30, or 40 µM. (A) the chemical structure of 2-MQB. The concentrations of cytokines in the supernatant, including (B) IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-β, (C) TNF-α, IFN-γ, (D) IL-12p70, (E) IL-8, and (F) IL-10, were determined using ELISA. The data, representing three independent experiments with similar results, are shown as mean ± SD. n = 4 mice per experiment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 indicate statistical significance compared to LPS alone, one-way ANOVA; horizontal bars indicate statistical comparison between 2-MQB-treated macrophages

Table 1.

The quinoxalines tested for potential anti-inflammatory properties

Intriguingly, the secretion of IL-10 by LPS-stimulated macrophages increased in the presence of 2-MQB, but this effect was limited to the concentration of 40 µM (Fig. 1F). These findings suggest that 2-MQB acts as a new immunomodulator, attenuating the inflammatory response in macrophages. To our knowledge, the biological activities of 2-MQB have not been previously explored, prompting further investigation. Preliminary in vitro analysis indicated that 2-MQB at 30 µM affected most of the cytokines studied, with results closely resembling those at 40 µM. Therefore, 2-MQB at a concentration of 30 µM was deemed effective for subsequent in vitro experiments.

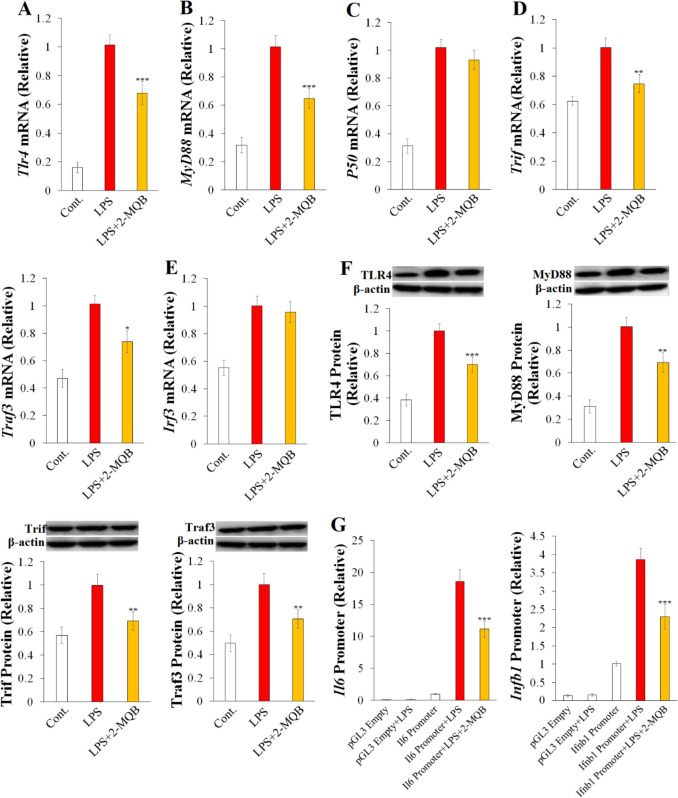

2-MQB Suppresses TLR4 Signaling Pathways

The LPS-induced endotoxin shock activates pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, specifically TLR4/NF-κB and TLR4/IRF3, leading to excessive secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines [1, 4, 5]. Therefore, we initially examined the potential impact of 2-MQB on the mRNA expression of key elements in these signaling pathways in LPS-stimulated macrophages. Notably, 2-MQB (30 µM) reduced the mRNA expression of Tlr4 relative to macrophages treated with LPS alone (Fig. 2A). It also led to a reduction in MyD88 mRNA, a critical element of the TLR4/NF-κB pathway (Fig. 2B). However, there were no notable differences in the mRNA expression of P50 (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, 2-MQB reduced the mRNA expression of TLR4/IRF3 pathway elements, including Trif and Traf3 (Fig. 2D), but not Irf3 (Fig. 2E). Subsequently, changes in the protein levels of TLR4, MyD88, Trif, and Traf3 were confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

2-MQB inhibits TLR4 signaling pathways. Purified macrophages were pre-treated with either DMSO or 2-MQB for 30 min, then cultured for 2 h for mRNA collection or 6 h for lysate collection either without (Cont.) or with LPS (0.2 µg/mL) in the absence or presence of 2-MQB at 30 µM. mRNA and proteins levels were determined by qPCR and immunoblotting, respectively. The mRNAs of (A) Tlr4, (B) MyD88, (C) P50, (D) Trif and Traf3, and (E) Irf3 relative to those of LPS alone. (F) Immunoblots and quantification of TLR4, MyD88, Trif, and Traf3 proteins relative to those of LPS alone. (G) Luciferase activities of pGL3 empty or Il6- or Ifnb1-harboring pGL3 transfected in peritoneal macrophages for 12 h, incubated with DMSO (pGL3 Empty) or 2-MQB (30 µM) for 30 min, and then cultured for 6 h without or with LPS (0.2 µg/mL). The data, representing three independent experiments with similar results, are shown as mean ± SD. n = 4 mice per experiment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 indicate statistical significance compared to LPS alone, one-way ANOVA

Activation of the TLR4 signaling pathways, including NF-κB and IRF3, has been shown to trigger the transcription of several downstream genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IFN-β, respectively [5]. Therefore, we examined the potential impact of 2-MQB on the transcriptional activities of TLR4 pathways by measuring luciferase activities in LPS-stimulated macrophages transfected with either an empty pGL3 plasmid or pGL3 plasmids harboring the Il6 or Ifnb1 promoters. As depicted in Fig. 2G, 2-MQB decreased the luciferase activities driven by the Il6 and Ifnb1 promoters compared to LPS alone-treated macrophages, indicating reduced transcriptional activities of the TLR4/NF-κB and TLR4/IRF3 pathways. Collectively, these findings introduced 2-MQB as a novel suppressor of the TLR4/NF-κB and TLR4/IRF3 signaling cascades in vitro.

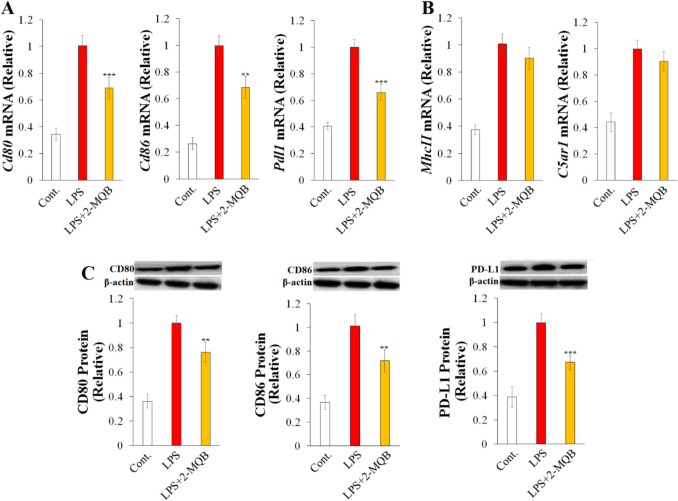

2-MQB Modulates the Phenotype of LPS-Stimulated Macrophage

To better understand the anti-inflammatory effects of 2-MQB, we examined variations in the expression of genes encoding surface molecules associated with sepsis pathogenesis in LPS-stimulated macrophages. These genes included the antigen-presenting receptor MHC II, the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86, the pro-inflammatory fragment C5a receptor (C5aR), and the immunosuppressive factor PD-L1 [1, 26–28]. As depicted in Fig. 3A, 2-MQB (30 µM) decreased the mRNA levels of Cd80, Cd86, and Pdl1 in LPS-stimulated macrophages, while it did not significantly change the mRNA levels of MhcII and C5ar1 (Fig. 3B). Subsequently, changes in the protein levels of CD80, CD86, and PD-L1 were confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 3C). These findings suggest that 2-MQB may influence LPS-stimulated macrophages by selectively modulating surface markers.

Fig. 3.

2-MQB selectively inhibits surface molecules on LPS-stimulated macrophages. Purified macrophages were pre-treated with either DMSO or 2-MQB for 30 min, then cultured for 2 h for mRNA collection or 6 h for lysate collection either without (Cont.) or with LPS (0.2 µg/mL) in the absence or presence of 2-MQB at 30 µM. mRNA and protein levels were determined by qPCR and immunoblotting, respectively. The mRNAs of (A) Cd80, Cd86, and Pdl1, and (B) MhcII and C5ar1 relative to those of LPS alone. (C) Immunoblots and quantification of CD80, CD86, and PD-L1 relative to those of LPS alone. The data, representing three independent experiments with similar results, are shown as mean ± SD. n = 4 mice per experiment. **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 indicate statistical significance compared to LPS alone, one-way ANOVA

2-MQB Ameliorates the Severity of LPS-Induced Septic Shock

Having reported the anti-inflammatory potential of 2-MQB in LPS-stimulated macrophages in vitro, we investigated its possible influence on the survival rate of mice subjected to LPS-induced endotoxin shock. Initial optimization experiments indicated that 2-MQB at doses of 1 and 6 mg/kg did not affect the weights of the spleen and kidneys, while a slight increase in liver weight was observed at the higher dose (Fig. 4A). Therefore, 2-MQB at doses of 1, 3, and 5 mg/kg was administrated to avoid possible toxicity and to clearly distinguish the effects of different doses. As depicted in Fig. 4B, inducing endotoxin shock with LPS drastically reduced the survival rate of mice to 0% by 72 h after challenge. However, treatment with 2-MQB at doses of 3 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg significantly increased survival rates to 25% and 50%, respectively. Furthermore, 2-MQB at these doses reduced the clinical scores of endotoxin shock (Fig. 4C). The scoring system used to assess the severity of endotoxemia is cumulative, encompassing six distinct parameters: respiration, eye condition, consciousness, response to stimulus, appearance, and activity. Therefore, the reduced clinical scores with 2-MQB treatment suggest a potentially improved prognosis in septic mice.

Fig. 4.

2-MQB attenuates LPS-induced endotoxin shock. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with vehicle (Cont.) or LPS, without or with 2-MQB. The 2-MQB was injected in mice at 0 and 6 h after LPS injection and observed for 144 h. (A) Weights of the spleen, kidneys, and liver from Control mice and LPS-injected mice (7.5 mg/kg) without or with 2-MQB at 1 or 6 mg/kg on day 6 after LPS injection. (B) Survival (%) of Control mice and LPS-injected mice (20 mg/kg) without or with 2-MQB at 1, 3, or 5 mg/kg. (C) Clinical score of Control mice and LPS-injected mice (20 mg/kg) without or with 2-MQB at 1, 3, or 5 mg/kg. The serum levels of (D) IL-1β, IFN-β, (E) IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, (F) IL-12p70, and (G) IL-10 in blood samples from Control mice and LPS-injected mice (7.5 mg/kg) without or with 2-MQB at 1, 3, or 5 mg/kg were determined using ELISA. The data, representing three independent experiments with similar results, are shown as mean ± SD. (A) n = 4 and (B-G) n = 8 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 indicate statistical significance. (A, D-G) one-way ANOVA, compared to LPS treatment alone; (D and E) horizontal bars indicate statistical comparison between 2-MQB treatments. (B) log-rank, and (C) two-way ANOVA; vertical bars indicate statistical comparison, (C) horizontal bar indicates the range of compared data

The pathogenesis of sepsis and septic shock involves a rapid and intense activation of the immune system, resulting in a cytokine storm characterized by excessive secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines [4, 11]. To further explore the therapeutic potential of 2-MQB, a sublethal dose of LPS (7.5 mg/kg) was administered, and serum levels of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12p70, IFN-β, TNF-α, and IL-10 were measured. Consistent with its effects on pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro, 2-MQB at the examined doses (1, 3, and 5 mg/kg) decreased serum levels of IL-1β and IFN-β (Fig. 4D). Its suppressive effects on IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-12p70 were more pronounced at the higher doses (Fig. 4E and F). However, 2-MQB did not significantly alter IL-10 production (Fig. 4G). Overall, these findings indicate that 2-MQB effectively mitigates the inflammatory innate immune response during endotoxin shock.

2-MQB Suppresses Tissue Injury in Vital Organs

To assess the effects of 2-MQB on tissue damage, we conducted histopathological studies on the spleen, kidney, and lung tissues from mice subjected to LPS-induced endotoxin shock. As shown in Fig. 5A, LPS caused marked proliferation and fusion of lymphocyte follicles in the spleen. In the kidney, it resulted in shrunken glomeruli, vascular congestion, stromal hyalinization, and cloudy swelling. The lungs exhibited severe interstitial neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate and significantly congested vessels. 2-MQB treatment at doses of 3 and 5 mg/kg alleviated inflammation-induced tissue injury in the spleen, kidney, and lung, with the higher dose showing more pronounced protective effects (Fig. 5A). The representative images in Fig. 5A illustrate that 2-MQB at 5 mg/kg resulted in moderately congested red pulp with reduced neutrophilic infiltration. The kidney showed significant improvements in LPS-induced pathological changes, appearing nearly normal except for some cloudy swelling of renal tubules. Additionally, the lung exhibited a marked reduction in pathological findings, along with extensive areas of compensatory emphysema. Minimal pathological improvements were observed with 2-MQB at 1 mg/kg in the tissues of the examined organs (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

2-MQB mitigates tissue injury in LPS-induced endotoxin shock. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with vehicle (Cont.) or LPS (20 mg/kg), without or with 2-MQB at 1, 3, or 5 mg/kg. The 2-MQB was injected in mice at 0 and 6 h and tissue samples were collected 48 h after LPS injection. (A) Representative histology images of spleen, kidney and lung (200X; scale bar = 100 µm). Serum levels of (B) PCT, (C) CRP, (D) KIM-1 and AST, (E) ALT, and (F) lactate in blood samples from Control mice and LPS-injected mice without or with 2-MQB were determined using ELISA and assay kits. The data, representing three independent experiments with similar results, are shown as mean ± SD. n = 8 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 indicate statistical significance compared to LPS treatment alone, (B-F) one-way ANOVA; horizontal bars indicate statistical comparison between 2-MQB treatments

We next quantified serum levels of PCT and CRP, which are known markers of inflammatory conditions and organ dysfunction in sepsis [29]. As shown in Fig. 5B and C, 2-MQB at higher doses reduced serum levels of both PCT and CRP. Subsequently, we measured serum levels of KIM-1 (renal dysfunction), ALT and AST (liver injury), and lactate (tissue perfusion and hypoxemia). As shown in Fig. 5D, 2-MQB at the examined doses (1, 3, and 5 mg/kg) reduced serum levels of KIM-1 and AST, while the levels of ALT and lactate were lower at the higher doses (Fig. 5E and F). Taken together, these findings suggest that 2-MQB has systemic therapeutic potential in LPS-induced endotoxin shock.

2-MQB Suppresses Lymphocytes Number and TLR4 Signaling in Septic Mice

T and B lymphocytes are essential for the initial development and late immune suppression of sepsis [30–32]. To assess the effects of 2-MQB on lymphocyte populations, we counted T lymphocytes (CD4+ and CD8+) and B lymphocytes in the whole spleen from mice subjected to LPS-induced endotoxin shock. As shown in Fig. 6A, 2-MQB at 3 mg/kg decreased the total numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes 18 h after the LPS challenge, while there were no significant changes in the number of B lymphocytes (Fig. 6B). The higher dose of 2-MQB (5 mg/kg) led to a decrease in CD4+ T cells at both 6 and 18 h after LPS injection (Fig. 6C), while there were no significant changes in the number of CD8+ cells at 18 h (Fig. 6D). Consistent with the lower dose, the B lymphocyte counts in the spleen remained unchanged with 2-MQB at 5 mg/kg (Fig. 6E). Overall, these findings suggest that 2-MQB modulates the adaptive immune response directly and/or indirectly through T and B lymphocytes during endotoxin shock.

Fig. 6.

2-MQB modulates lymphocytes populations in LPS-induced endotoxin shock. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with LPS (7.5 mg/kg) without or with 2-MQB treatment at 3 or 5 mg/kg at 0 and 6 h after LPS injection. (A) The number of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and (B) B lymphocytes per spleen in mice treated with 2-MQB at 3 mg/kg at 0, 6, and 18 h after LPS injection. The number of (C) CD4+ and (D) CD8+ T lymphocytes and (E) B lymphocytes per spleen in mice treated with 2-MQB at 5 mg/kg at 0, 6, and 18 h after LPS injection. The data, representing three independent experiments with similar results, are shown as mean ± SD. (A-E) n = 4 mice per group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 indicate statistical significance compared to LPS treatment alone at a time point, one-way ANOVA

Having found that 2-MQB inhibited TLR4 signaling in vitro, we examined its potential inhibitory effects on TLR4 signaling in LPS-induced endotoxin shock. Septic mice received 2-MQB at doses of 3 or 5 mg/kg, and mRNA expression of TLR4 signaling elements was quantified in peritoneal macrophages 6 h after LPS injection. As shown in Fig. 7A, Tlr4, MyD88, and Trif mRNA levels were reduced with 2-MQB treatment at 3 mg/kg, while there was no significant reduction in Traf3 mRNA levels (Fig. 7B). In comparison, 2-MQB treatment at 5 mg/kg decreased mRNA expression of all examined TLR4 signaling pathway elements (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 7.

2-MQB inhibits TLR4 signaling in LPS-induced endotoxin shock. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with vehicle (Cont.) or LPS (7.5 mg/kg) without or with 2-MQB treatment at 3 or 5 mg/kg at 0 and 6 h after LPS injection. The mRNA levels were determined by qPCR. The mRNAs of (A) Tlr4, MyD88, Trif, and (B) Traf3 in peritoneal macrophage from Control mice and LPS-injected mice without or with 2-MQB at 3 mg/kg relative to LPS alone. The mRNAs of (C) Tlr4, MyD88, Trif, and Traf3 in peritoneal macrophage from Control mice and LPS-injected mice without or with 2-MQB at 5 mg/kg relative to LPS alone. The data, representing three independent experiments with similar results, are shown as mean ± SD. n = 5 mice per group. **P < 0.01 indicates statistical significance compared to LPS treatment alone, one-way ANOVA

2-MQB Ameliorates the Severity of CLP

Polymicrobial models of sepsis involve various pathogens, better reflecting the complex infections seen in humans [33]. Therefore, the therapeutic potential of 2-MQB was assessed using the CLP model. 2-MQB was administered at doses of 3 or 5 mg/kg, which had shown significant therapeutic potential in LPS-induced sepsis. As depicted in Fig. 8A, CLP reduced the survival rate of mice to 0% by 120 h after surgery. However, treatment with 2-MQB at 3 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg significantly improved survival rates to 25% and 37.5%, respectively. Furthermore, 2-MQB at these doses ameliorated the severity of sepsis, as indicated by the cumulative clinical scores (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

2-MQB ameliorates the severity of polymicrobial sepsis. Mice underwent CLP laparotomy and injected with vehicle (Cont.) or LPS, without or with 2-MQB at 3 or 5mg/kg 0 and 6 h after surgery and observed for 144 h. (A) Survival (%) of Control mice and CLP mice without or with 2-MQB. (B) Clinical score of Control mice and CLP mice without or with 2-MQB. The serum levels of (C) IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-β, and (D) IL-12p70 and IFN-γ were determined using ELISA. (E) Bacterial load (CFU; Colony forming unit) in peritoneal lavage and blood samples obtained at 24 h postsurgery. The data, representing three independent experiments with similar results, are shown as mean ± SD. (A-E) n = 8 mice per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 indicate statistical significance. (A) log-rank, (B) two-way ANOVA; vertical bars indicate statistical comparison, (B) horizontal bar indicates the range of compared data. (C-E) one-way ANOVA, compared to LPS treatment alone

2-MQB (3 and 5 mg/kg) decreased serum levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-β (Fig. 8C), while the suppressive effects of 2-MQB on IL-12p70 and IFN-γ were more pronounced at higher doses (Fig. 8D). Subsequently, to investigate the potential mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of 2-MQB on survival and the systemic inflammatory response, bacterial load was determined in peritoneal lavage and peripheral blood. Interestingly, lower bacterial loads in both the peritoneal lavage and blood were observed with 2-MQB treatment at both 3 and 5 mg/kg (Fig. 8E).

Finally, histopathological studies were conducted to assess the effects of 2-MQB on CLP-induced tissue damage in the spleen, kidney, and lung. As shown in Fig. 9, CLP caused markedly congested red pulp and fused lymphoid follicles in the spleen. It led to vascular congestion, atrophied glomeruli, and widespread stromal hyalinization in the kidney, as well as thickened interalveolar septa with congested blood vessels and massive neutrophilic infiltration in the lung. Tissue injury in the spleen, kidney, and lung was alleviated with 2-MQB at doses of 3 and 5 mg/kg, with the higher dose exhibiting more pronounced protective effects. Treatment with 2-MQB at 5 mg/kg resulted in marked improvement in the spleen, with mildly congested red pulp. It improved renal pathology, showing moderate cloudy swelling in the tubular epithelium. Additionally, it led to significant improvement in pulmonary pathology, with residual minimal congestion and compensatory emphysema. Collectively, these findings reinforce the therapeutic potential of 2-MQB in sepsis.

Fig. 9.

2-MQB mitigates tissue injury in polymicrobial sepsis. Mice underwent CLP laparotomy and injected with vehicle (Cont.) or 2-MQB at 3 or 5 mg/kg at 0 and 6 h and tissue samples were collected 48 h after surgery. Representative histology images of the spleen, kidney and lung from Control mice and CLP mice without or with 2-MQB (200X; scale bar = 100 µm)

Discussion

Current treatments for sepsis and septic shock have shown limited success in managing these severe inflammatory conditions, underscoring the need for new, effective, and affordable options. This study exploited both in vitro and in vivo models to present 2-MQB as a promising anti-inflammatory agent with therapeutic potential for sepsis and septic shock. This quinoxaline derivative attenuated the severity of the inflammatory syndrome, improved survival rates, suppressed the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and mitigated tissue damage in multiple organs in mice subjected to LPS-induced endotoxin shock and CLP models. Notably, 2-MQB inhibited both TLR4 signaling pathways, NF-κB and IRF3, by reducing the expression of key signaling elements and the transcriptional activities on the promoters of downstream genes.

Quinoxaline derivatives are a an important class of heterocyclic compounds in the pharmaceutical industry, serving as a nucleus for the development of new compounds with various biological activities [34]. While the anti-inflammatory properties of several quinoxaline derivatives have been documented, their therapeutic potential in sepsis remains unexplored. In this study, initial in vitro experiments revealed that the quinoxaline derivative 2-MQB acts as an anti-inflammatory agent. It effectively decreased the secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12p70, IFN-γ, IFN-β, and TNF-α, while modestly increasing the secretion of IL-10 in LPS-stimulated macrophages. Although the anti-inflammatory effects of 2-MQB have not been previously investigated, other molecules containing a quinoxaline moiety have been reported to suppress the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro. For example, a series of 6,9-dichloro-4-ethoxy[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]quinoxaline compounds inhibit the secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α by LPS-stimulated HL-60 myeloid cells [35]. Additionally, several novel pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoxaline-based derivatives inhibit LPS-induced expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in microglia [36].

Given that mice have a low sensitivity to LPS [37], we administered high dose of LPS to mimic sepsis-induced Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and severe endotoxemia [38], allowing us to evaluate survival and tissue damage. Since sublethal dose of LPS is sufficient to cause systemic inflammation with rapidly increased serum cytokines [39], we also used low dose of LPS which induced moderate endotoxemia [40, 41], enabling us to assess cytokines, TLR4 signaling, and lymphocyte populations. Consistent with the observed reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro, 2-MQB treatment reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines in septic mice, including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12p70, IFN-γ, IFN-β, and TNF-α. The potential of quinoxaline-based compounds to suppress the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in vivo has been reported. For instance, the quinoxaline derivatives DEQX and OAQX have been shown to reduce IL-1β and TNF-α levels and suppress leukocyte migration in the carrageenan model of peritonitis in mice [18].

Trifluoromethoxy quinoxaline reduces the inflammatory cells, restores normal epithelial tissue, and reduces TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and INF-γ secretion in a murine model of gastric ulcer [19]. Contrary to the in vitro findings, 2-MQB treatment did not significantly increase serum IL-10 levels in septic mice. The enhancing effect of 2-MQB on IL-10 in vitro was modest and confined to the highest concentration. Generally, this moderate effect of 2-MQB might be abolished in the complex in vivo system, where intricate interactions among immune cells, cytokines, and systemic factors can influence IL-10 production.

Dimerization of TLR4 induced by LPS activates the TLR4/NF-κB and TLR4/IRF3 signaling pathways. This activation leads to the expression of downstream genes encoding pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and type I IFNs [2, 5, 42]. Earlier research has shown that suppressing the expression and/or phosphorylation of TLR4 pathway elements inhibits its pro-inflammatory functions [6, 9, 10, 43]. In this study, mechanistic investigations both in vitro and in vivo revealed that 2-MQB decreased the expression of TLR4, MyD88, Trif, and Traf3. Additionally, it inhibited the transcriptional functions of the TLR4/NF-κB and TLR4/IRF3 signaling cascades. These findings suggest that 2-MQB most likely decreased the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines through the inhibition of the TLR4/NF-κB and TLR4/IRF3 signaling pathways. To our knowledge, only two studies have indirectly linked quinoxaline’s anti-inflammatory effects with TLR4 signaling. Oxymatrine, a natural quinoxaline, has been shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects through CathD-dependent inhibition of the HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway, both in vivo and in vitro [20]. Additionally, several novel pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoxaline-based compounds have been identified as activators of Sirtuin 6 (Sirt6) [36], an enzyme plays role in regulating inflammatory diseases [44, 45], through interacting with RelA subunit of NF-κB and modulating the expression of downstream target genes [46]. It has been also found that the quinoxaline derivatives 5e and 5f block P38 MAPK, demonstrating potent in vivo anti-inflammatory effects [47]. These observations suggest that mechanisms other than direct suppression of TLR4 pathways may contribute to the anti-inflammatory effects of 2-MQB. Further investigations may be needed to explore more potential mechanisms.

Our findings indicated that 2-MQB reduced the levels of CD80, CD86, and PD-L1 in macrophages stimulated with LPS, while the levels of MHCII and C5aR remained unchanged. CD80 and CD86 are key surface markers induced by LPS on M1 macrophages. They play significant roles in exacerbating the inflammatory response during endotoxin shock and contribute to tissue damage [26]. Therefore, the 2-MQB-mediated reduction of CD80 and CD86, along with decreased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, likely led to improved outcomes and mitigated tissue damage in septic mice. On the other hand, increased PD-L1 levels is associated with immunosuppression and indicates a dysregulated response in sepsis [27, 48]. Consequently, blocking PD-L1 is associated with the restoration of the normal macrophage functions [49, 50]. In this context, the downregulated expression of PD-L1 with 2-MQB treatment might be associated with the restoration of a normal macrophage response. Additionally, cytokine production by macrophages during the inflammatory innate immune response plays a crucial role in driving systemic inflammation in endotoxin shock. Excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines can lead to various organ dysfunctions and higher mortality [51, 52]. Therefore, the lower serum concentrations of the inflammatory biomarkers PCT and CRP suggest that 2-MQB could enhance systemic anti-inflammation, thereby mitigating tissue damage in multiple organs of septic mice. Elevated levels of markers such as lactate, KIM-1, AST, and ALT during sepsis indicate hypoperfusion and hypoxia, as well as renal and hepatic dysfunction, respectively [53–55]. Thus, the reduced levels of these markers, along with ameliorated tissue injury and decreased inflammatory markers, indicate a broad protective potency of 2-MQB even in severe sepsis.

While the murine model of LPS-induced endotoxemia provides valuable insights into certain molecular mechanisms, it differs from human sepsis and does not capture its intricate and multifaceted nature [56]. Polymicrobial models, such as CLP, involve different pathogens and may better reflect the complex infection seen in humans. Therefore, we assessed the therapeutic potential of 2-MQB in the CLP model. Similar to its effects in the LPS model, 2-MQB treatment improved survival and reduced the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12p70, IFN-γ, IFN-β, and TNF-α, in CLP septic mice. These effects were accompanied by mitigated damage in the tissues of the spleen, kidney, and lung, as well as a reduced bacterial load in both peritoneal lavage and peripheral blood. The reduced bacterial load was likely one of the mechanisms behind the anti-inflammatory properties of 2-MQB in CLP septic mice. Considering that 2-MQB has the potential to partially restore the innate immune response in septic mice through its effects on the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the expression of surface markers, including PD-L1, it is reasonable to hypothesize that such partial restoration could improve bacterial clearance in both the spleen and blood.

The study exploited both in vitro and in vivo methods to identify 2-MQB, a new immunomodulatory molecule belonging to quinoxaline family with significant anti-inflammatory properties. In mouse models of sepsis and septic shock, 2-MQB showed strong therapeutic potential by reducing severe inflammatory responses and alleviating tissue damage. Notably, the findings revealed that 2-MQB acts as a new suppressor of the TLR4/NF-κB and TLR4/IRF3 signaling pathways in both experimental settings. Overall, 2-MQB is a promising candidate for treating sepsis and septic shock due to its ability to regulate excessive immune reactions. Furthermore, the quinoxaline moiety in 2-MQB provides a versatile structure, making it a promising foundation for developing new anti-inflammatory drugs.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their deep gratitude to Professor Tadamitsu Kishimoto, Immunology Frontier Research Center (iFReC)-Worl Premier Research Center (WPI), Osaka University, Japan, for providing plasmid. The authors are grateful for Deanship of Scientific Research, King Faisal University (KFU), Hofuf, Saudi Arabia, and Deanship of Scientific Research, Aqaba Medical Sciences University (AMSU), Aqaba, Jordan for valuable technical and administrative support.

Author Contributions

Hamza Hanieh: Designed study, Performed research, Analyzed data, Wrote the paper, Resources. Manal Alfwuaires: Performed research, Analyzed data, Wrote the paper, Resources. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hotchkiss, R.S., L.L. Moldawer, S.M. Opal, K. Reinhart, I.R. Turnbull, and J.-L. Vincent. 2016. Sepsis and septic shock. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2: 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer, M., C.S. Deutschman, C.W. Seymour, M. Shankar-Hari, D. Annane, M. Bauer, et al. 2016. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). Journal of the American Medical Association 315: 801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudd, K.E., S.C. Johnson, K.M. Agesa, K.A. Shackelford, D. Tsoi, D.R. Kievlan, et al. 2020. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: Analysis for the global burden of disease study. The Lancet 395: 200–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao, M., G. Wang, and J. Xie. 2023. Immune dysregulation in sepsis: Experiences, lessons and perspectives. Cell Death Discovery 9: 465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basak, B., and S. Akashi-Takamura. 2024. IRF3 function and immunological gaps in sepsis. Frontiers in Immunology 15: 1336813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romerio, A., and F. Peri. 2020. Increasing the chemical variety of small-molecule-based TLR4 modulators: An overview. Frontiers in Immunology 11: 1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billod, J.-M., A. Lacetera, J. Guzmán-Caldentey, and S. Martín-Santamaría. 2016. Computational approaches to toll-like receptor 4 modulation. Molecules 21: 994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanieh H., Alfwuaires M.A., Abduh M.S., Abdrabu A., Qinna N.A., and Alzahrani A.M. 2024 Protective effects of a Dihydrodiazepine against endotoxin shock through suppression of TLR4/NF-κB/IRF3. Signaling Pathways. Inflammation 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.AlZahrani, A. M., P. Rajendran, G. M. Bekhet, R. Balasubramanian, L. K. Govindaram, Ahmed EA, et al. 2024. Protective effect of 5, 4-dihydroxy-6, 8-dimethoxy7-O-rhamnosylflavone from Indigofera aspalathoides Vahl on lipopolysaccharide-induced intestinal injury in mice. Inflammopharmacology 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Vaez, H., M. Rameshrad, M. Najafi, J. Barar, A. Barzegari, and A. Garjani. 2016. Cardioprotective effect of metformin in lipopolysaccharide-induced sepsis via suppression of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in heart. European Journal of Pharmacology 772: 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng, Y., Y. Gao, W. Zhu, X.-g Bai, and J. Qi. 2024: Advances in molecular agents targeting toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathways for potential treatment of sepsis. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 268: 116300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambertucci, F., O. Motiño, S. Villar, J.P. Rigalli, Alvarez M. de Luján, V.A. Catania, et al. 2017. Benznidazole, the trypanocidal drug used for Chagas disease, induces hepatic NRF2 activation and attenuates the inflammatory response in a murine model of sepsis. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 315: 12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yildiz, I.E., A. Topcu, I. Bahceci, M. Arpa, L. Tumkaya, T. Mercantepe, et al. 2021. The protective role of fosfomycin in lung injury due to oxidative stress and inflammation caused by sepsis. Life Sciences 279: 119662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin, Y., Z. Li, H. Chen, X. Jiang, Y. Zhang, and F. Wu. 2019. Effect of dexmedetomidine on kidney injury in sepsis rats through TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB/iNOS signaling pathway. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 23: 5020–5025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng, G., W. Sa, C. Cao, L. Guo, H. Hao, Z. Liu, et al. 2016. Quinoxaline 1, 4-di-N-oxides: Biological activities and mechanisms of actions. Frontiers in Pharmacology 7: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meka, G., and R. Chintakunta. 2023. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity of quinoxaline derivatives: Design synthesis and characterization. Results in Chemistry 5: 100783. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anjali, Kamboj P, O., Alam, H., Patel, I., Ahmad, S. S., Ahmad et al. 2024. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation, and in silico studies of quinoxaline derivatives as potent p38α MAPK inhibitors. Archiv der Pharmazie 357:2300301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Neri, J.M., P.E.A. Siqueira, A.LCd.S.L. Oliveira, R.M. Araújo, RFd. Araújo, A.A. Martins, et al. 2024. Anticancer, anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of aminoalcohol-based quinoxaline small molecules. Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira 39: e395124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daghistani, H., Y. Almoghrabi, T. Shamrani, M. M. Jawi, and M. A. Bazuhai. 2024. Mitigation of indomethacin-induced gastric ulcer in rats by 2, 3-Dichloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy) quinoxaline: modulation of inflammatory mechanisms. Journal of Contemporary Medical Sciences 10:318–324.

- 20.Gan, P., L. Ding, G. Hang, Q. Xia, Z. Huang, X. Ye, et al. 2020. Oxymatrine attenuates dopaminergic neuronal damage and microglia-mediated neuroinflammation through cathepsin D-dependent HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB pathway in Parkinson’s disease. Frontiers in Pharmacology 11: 776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferri, F., A. Parcelier, V. Petit, A.-S. Gallouet, D. Lewandowski, M. Dalloz, et al. 2015. TRIM33 switches off Ifnb1 gene transcription during the late phase of macrophage activation. Nature Communications 6: 8900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaman, M.M.-U., K. Masuda, K.K. Nyati, P.K. Dubey, B. Ripley, K. Wang, et al. 2016. Arid5a exacerbates IFN-γ–mediated septic shock by stabilizing T-bet mRNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: 11543–11548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo, W.-J., S.-L. Yu, C.-C. Chang, M.-H. Chien, Y.-L. Chang, K.-M. Liao, et al. 2022. HLJ1 amplifies endotoxin-induced sepsis severity by promoting IL-12 heterodimerization in macrophages. eLife 11: e76094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zemtsovski, J.D., S. Tumpara, S. Schmidt, V. Vijayan, A. Klos, R. Laudeley, et al. 2024. Alpha1-antitrypsin improves survival in murine abdominal sepsis model by decreasing inflammation and sequestration of free heme. Frontiers in Immunology 15: 1368040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shrum, B., R.V. Anantha, S.X. Xu, M. Donnelly, S.M. Haeryfar, J.K. McCormick, et al. 2014. A robust scoring system to evaluate sepsis severity in an animal model. BMC Research Notes 7: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nolan, A., H. Kobayashi, B. Naveed, A. Kelly, Y. Hoshino, S. Hoshino, et al. 2009. Differential role for CD80 and CD86 in the regulation of the innate immune response in murine polymicrobial sepsis. PLoS ONE 4: e6600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamori, Y., E.J. Park, and M. Shimaoka. 2021. Immune deregulation in sepsis and septic shock: Reversing immune paralysis by targeting PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. Frontiers in Immunology 11: 624279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, Y.-C., S.-T. Shou, and Y.-F. Chai. 2022. Immune checkpoints in sepsis: New hopes and challenges. International Reviews of Immunology 41: 207–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lelubre, C., and J.-L. Vincent. 2018. Mechanisms and treatment of organ failure in sepsis. Nature Reviews Nephrology 14: 417–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pauken, K.E., and E.J. Wherry. 2015. SnapShot: T cell exhaustion. Cell 3163: 1038-1038. e1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Garofalo, A.M., M. Lorente-Ros, G. Goncalvez, D. Carriedo, A. Ballén-Barragán, A. Villar-Fernández, et al. 2019. Histopathological changes of organ dysfunction in sepsis. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental 7: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang, J., X. Zhu, and J. Feng. 2024. The changes in the quantity of lymphocyte subpopulations during the process of sepsis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25: 1902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alverdy, J.C., R. Keskey, R. Thewissen. 2020. Can the cecal ligation and puncture model be repurposed to better inform therapy in human sepsis? Infection and immunity 88. 10.1128/IAI.00942-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Pereira, J.A., A.M. Pessoa, M.N.D. Cordeiro, R. Fernandes, C. Prudêncio, J.P. Noronha, et al. 2015. Quinoxaline, its derivatives and applications: A State of the Art review. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 97: 664–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guirado, A., J.I.L. Sánchez, A.J. Ruiz-Alcaraz, D. Bautista, and J. Gálvez. 2012. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 4-alkoxy-6, 9-dichloro [1, 2, 4] triazolo [4, 3-a] quinoxalines as inhibitors of TNF-α and IL-6. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 54: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu, J., S. Shi, G. Liu, X. Xie, J. Li, A.A. Bolinger, et al. 2023. Design, synthesis, and pharmacological evaluations of pyrrolo [1, 2-a] quinoxaline-based derivatives as potent and selective sirt6 activators. European journal of medicinal chemistry 246: 114998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cauwels, A., B. Vandendriessche, and P. Brouckaert. 2013. Of mice, men, and inflammation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110: E3150–E3150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva, J.F., V.C. Olivon, F.L.A. Mestriner, C.Z. Zanotto, R.G. Ferreira, N.S. Ferreira, et al. 2020. Acute increase in O-GlcNAc improves survival in mice with LPS-induced systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Frontiers in physiology 10: 1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seemann, S., F. Zohles, and A. Lupp. 2017. Comprehensive comparison of three different animal models for systemic inflammation. Journal of biomedical science 24: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kunze, F.A., M. Bauer, J. Komuczki, M. Lanzinger, K. Gunasekera, A.-K. Hopp, et al. 2019. ARTD1 in myeloid cells controls the IL-12/18–IFN-γ axis in a model of sterile sepsis, chronic bacterial infection, and cancer. The Journal of Immunology 202: 1406–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malgorzata-Miller, G., L. Heinbockel, K. Brandenburg, J.W. van der Meer, M.G. Netea, and L.A. Joosten. 2016. Bartonella quintana lipopolysaccharide (LPS): Structure and characteristics of a potent TLR4 antagonist for in-vitro and in-vivo applications. Scientific reports 6: 34221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen, X.-S., S.-H. Wang, C.-Y. Liu, Y.-L. Gao, X.-L. Meng, W. Wei, et al. 2022. Losartan attenuates sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy by regulating macrophage polarization via TLR4-mediated NF-κB and MAPK signaling. Pharmacological Research 185: 106473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okan, A., Z. Doğanyiğit, S. Yilmaz, S. Uçar, E.S. Arikan Söylemez, and R. Attar. 2023. Evaluation of the protective role of resveratrol against sepsis caused by LPS via TLR4/NF-κB/TNF-α signaling pathways: Experimental study. Cell Biochemistry and Function 41: 423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mendes, K.L., D. de Farias Lelis, and S.H.S. Santos. 2017. Nuclear sirtuins and inflammatory signaling pathways. Cytokine, growth factor reviews 38: 98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hou, K.L., S.K. Lin, L.H. Chao, E. Hsiang-Hua Lai, C.C. Chang, C.T. Shun, et al. 2017. Sirtuin 6 suppresses hypoxia-induced inflammatory response in human osteoblasts via inhibition of reactive oxygen species production and glycolysis—A therapeutic implication in inflammatory bone resorption. BioFactors 43: 170–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blasi, E., R. Barluzzi, V. Bocchini, R. Mazzolla, and E.F. Bistoni. 1990. Immortalization of murine microglial cells by a v-raf/v-myc carrying retrovirus. Journal of neuroimmunology 27: 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tariq, S., O. Alam, and M. Amir. 2018. Synthesis, anti-inflammatory, p38α MAP kinase inhibitory activities and molecular docking studies of quinoxaline derivatives containing triazole moiety. Bioorganic Chemistry 76: 343–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson, J.K., Y. Zhao, M. Singer, J. Spencer, and M. Shankar-Hari. 2018. Lymphocyte subset expression and serum concentrations of PD-1/PD-L1 in sepsis-pilot study. Critical Care 22: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, Y., Y. Zhou, J. Lou, J. Li, L. Bo, K. Zhu, et al. 2010. PD-L1 blockade improves survival in experimental sepsis by inhibiting lymphocyte apoptosis and reversing monocyte dysfunction. Critical care 14: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen, J., R. Chen, S. Huang, B. Zu, and S. Zhang. 2021. Atezolizumab alleviates the immunosuppression induced by PD-L1-positive neutrophils and improves the survival of mice during sepsis. Molecular Medicine Reports 23: 1–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zech, A., B. Wiesler, C.K. Ayata, T. Schlaich, T. Dürk, M. Hoßfeld, et al. 2016. P2rx4 deficiency in mice alleviates allergen-induced airway inflammation. Oncotarget 7: 80288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Falcón, C.R., N.F. Hurst, A.L. Vivinetto, P.H.H. López, A. Zurita, G. Gatti, et al. 2021. Diazepam impairs innate and adaptive immune responses and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Frontiers in Immunology 12: 682612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vincent, J.-L., and D. De Backer. 2013. Circulatory shock. New England Journal of Medicine 369: 1726–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brozat, J.F., N. Harbalioğlu, P. Hohlstein, S. Abu Jhaisha, M.R. Pollmanns, J.K. Adams, et al. 2024. Elevated serum KIM-1 in sepsis correlates with kidney dysfunction and the severity of multi-organ critical illness. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25: 5819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang, D., Y. Yin, and Y. Yao. 2014. Advances in sepsis-associated liver dysfunction. Burns & trauma 2:2321–3868. 132689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Bojalil, R., A. Ruíz-Hernández, A. Villanueva-Arias, L.M. Amezcua-Guerra, S. Cásarez-Alvarado, A.M. Hernández-Dueñas, et al. 2023. Two murine models of sepsis: Immunopathological differences between the sexes—possible role of TGFβ1 in female resistance to endotoxemia. Biological Research 56: 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.