Abstract

Medical environment comfort directly affects patient treatment outcomes and recovery processes. This study constructs a machine learning prediction model for patient excessive discomfort based on environmental monitoring data from medical infusion rooms. The research collected 1,000 samples with 11 environmental feature data, including temperature, humidity, noise level, air quality index, wind speed, lighting intensity, oxygen concentration, carbon dioxide concentration, air pressure, air circulation speed, and air pollutant concentration. Through comparative analysis of 10 machine learning algorithms, XGBoost model demonstrated the best performance with accuracy of 85.2%, precision of 86.5%, recall of 92.3%, F1-score of 0.893, and ROC-AUC of 0.889. Using SHAP and LIME interpretability methods, analysis revealed that air quality index (importance score 1.117) and temperature (importance score 1.065) are the most critical factors affecting patient comfort, followed by noise level (0.676) and humidity (0.454). SHAP partial dependence analysis revealed specific impact patterns of environmental factors: humidity shows positive correlation with discomfort, noise level exhibits strong linear positive correlation, temperature demonstrates nonlinear relationships, and air quality deterioration significantly increases patient discomfort. LIME local explanations validated the consistency of analysis results, providing scientific basis for personalized environmental control. The research results indicate that machine learning methods based on multi-sensor environmental monitoring can effectively predict patient discomfort. Interpretability analysis reveals the influence mechanisms of environmental factors, providing important support for intelligent management of medical environments and formulation of scientific control strategies.

Keywords: Medical environment comfort, Machine learning, Patient discomfort prediction, Explainable artificial intelligence, SHAP, LIME

Subject terms: Engineering, Environmental sciences, Mathematics and computing

Introduction

With the rapid development of medical informatization technology and the widespread application of artificial intelligence in the medical field, machine learning-based medical environment management systems are becoming an important component of modern hospital intelligent construction1. Medical environment comfort directly affects patient treatment outcomes, recovery processes, and overall medical experience, particularly in medical scenarios requiring long-term stays such as infusion therapy, where environmental factors significantly impact patients’ physiological and psychological states2,3. Traditional medical environment management primarily relies on manual observation and periodic detection, which suffers from poor real-time performance, low precision, and insufficient personalization4,5. In recent years, machine learning technology has shown tremendous potential in medical prediction and decision support, but existing research mainly focuses on disease diagnosis and treatment decisions, with relatively scarce research on medical environment comfort prediction6,7. Meanwhile, medical applications have extremely high requirements for model interpretability, as healthcare professionals need to understand the decision logic of models to build trust and make accurate judgments8,9.

Despite significant progress of machine learning in the medical field, there are still many research gaps and technical deficiencies in medical environment comfort prediction. First, existing research mainly concentrates on the impact analysis of single environmental factors, lacking comprehensive prediction models based on multi-dimensional environmental data10,11. Second, traditional statistical methods have limitations in handling complex nonlinear relationships, making it difficult to accurately capture the complex mapping relationships between environmental factors and patient comfort12,13. Third, the “black box” characteristics of models limit their practical application in medical scenarios, as healthcare professionals cannot understand the generation mechanism of prediction results, affecting model credibility and clinical acceptance14,15. Finally, there is a lack of systematic comparative studies on interpretability methods, and the applicability and effectiveness of different explanation techniques have not been fully validated16,17. Therefore, this study aims to address the following key issues:

Construct a patient comfort prediction model based on multi-dimensional environmental sensor data, systematically evaluating the performance of different machine learning algorithms in this task;

Introduce SHAP and LIME, two mainstream interpretability methods, to deeply analyze the specific influence mechanisms and importance ranking of environmental factors on patient comfort;

Conduct comparative analysis of SHAP and LIME methods to provide scientific basis for the selection and application of interpretability technologies in medical environment management.

The organization of this paper is as follows: Section “Related work” reviews related research work on machine learning in medical environment prediction and explainable artificial intelligence; Section “Methods” details data collection and preprocessing, feature engineering, machine learning model construction, and SHAP and LIME interpretability analysis methods; Section “4” presents experimental results of model performance comparison, feature importance analysis, and individual prediction explanation; Section “Discussion” provides in-depth discussion of research findings and application value from theoretical and practical perspectives; Section “Conclusion” summarizes the main contributions of this study and prospects for future research directions.

The primary contributions of this research include: (1) Novel Application Domain: This study represents the first systematic application of explainable AI techniques specifically to medical environment comfort prediction, addressing a critical gap in healthcare facility management; (2) Methodological Innovation: The comparative analysis of SHAP and LIME interpretability methods in the context of multi-sensor environmental monitoring provides new insights into optimal explanation strategies for healthcare applications; (3) Clinical Decision Support Framework: The development of a comprehensive decision support system that combines prediction accuracy with clinical interpretability, providing actionable insights for healthcare facility managers; (4) Validated Feature Importance Hierarchy: The identification and validation of key environmental factors (AQI, temperature, noise, humidity) through dual interpretability analysis provides evidence-based guidance for medical facility design and operation.

Related work

Medical environment comfort research

Medical environment comfort is a multi-dimensional concept involving the comprehensive effects of multiple environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, air quality, noise, and lighting1,2. Early medical environment research mainly focused on the impact of single factors, and has gradually developed into a research paradigm of multi-factor comprehensive assessment in recent years3,4. The pioneering research by Ulrich and colleagues showed that good medical environments can significantly shorten patient recovery time and reduce medical costs, establishing a theoretical foundation for evidence-based medical environment design5,6.

Temperature control is one of the core elements of medical environment management. Extensive clinical studies show that the temperature range of 20–26 °C is most suitable for patient rest and treatment, with temperatures that are too high or too low having adverse effects on patients’ physiological functions7,8. Research by Reinhardt et al. further confirmed the significant impact of temperature on patient recovery speed, particularly during postoperative recovery periods9. Humidity control is equally crucial, with studies showing that relative humidity in the 40–60% range can effectively reduce bacterial growth, improve patient comfort, and lower the risk of nosocomial infections10,11.

The impact of air quality on patient health has received significant attention in the medical community. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that PM2.5 concentrations in medical institutions should be controlled below 15 g/m

g/m to protect patients from air pollution hazards12,13. Research by Misra et al. showed that air quality index (AQI) has significant correlation with the incidence of respiratory diseases in patients, particularly for immunocompromised patient populations14,15. Additionally, oxygen and carbon dioxide concentrations in indoor air have been confirmed to have important impacts on patient comfort and recovery outcomes16,17.

to protect patients from air pollution hazards12,13. Research by Misra et al. showed that air quality index (AQI) has significant correlation with the incidence of respiratory diseases in patients, particularly for immunocompromised patient populations14,15. Additionally, oxygen and carbon dioxide concentrations in indoor air have been confirmed to have important impacts on patient comfort and recovery outcomes16,17.

Noise pollution is another important influencing factor in medical environments. Multiple studies indicate that noise exceeding 55dB significantly affects patient sleep quality and recovery outcomes, and may even lead to stress responses and elevated blood pressure18,19. Research by Vaishali et al. found that noise level control plays a key role in creating healing environments, particularly in medical locations requiring quiet environments such as intensive care units and rehabilitation wards20,21. Lighting conditions are equally important, as appropriate light intensity not only affects patients’ visual comfort but is also closely related to circadian rhythm regulation and mental health22,23.

Applications of machine learning in medical environment monitoring

In recent years, machine learning technology has been widely applied in medical environment monitoring, bringing revolutionary changes to traditional manual monitoring methods24,25. Support Vector Machines (SVM), as classic machine learning algorithms, have been successfully applied to predict air quality changes in operating rooms by establishing nonlinear mapping relationships between environmental parameters and air quality, achieving accurate prediction of pollutant concentrations26,27. Random forest algorithms have shown excellent performance in hospital energy consumption prediction, with their ensemble learning characteristics enabling effective handling of complex correlations in multi-dimensional environmental data28,29.

The introduction of deep learning methods has further enhanced the intelligent level of medical environment monitoring. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) have been applied to time series data analysis of medical environments, capable of capturing temporal dependencies and dynamic change patterns of environmental parameters30,31. The XGBoost algorithm, proposed by Chen and Guestrin, demonstrated superior performance in handling nonlinear relationships in medical data, with its gradient boosting mechanism effectively reducing prediction errors and improving model generalization capabilities32,33. Lightweight ensemble learning methods such as LightGBM have also shown good application prospects in medical environment prediction34,35.

Recent research indicates that ensemble learning methods have unique advantages in handling medical environment data. Research by Hasan et al. confirmed the effectiveness of multi-algorithm fusion in diabetes prediction, providing important reference for medical environment prediction36,37. These methods can effectively handle high-dimensional feature data and have strong generalization capabilities, particularly suitable for handling complex scenarios of multi-sensor data fusion in medical environments38,39. The application of machine learning technology has not only improved prediction accuracy but also achieved real-time monitoring and early warning, establishing a technical foundation for intelligent management of medical environments40,41.

Applications of explainable artificial intelligence in medical field

Interpretability is a key requirement for medical AI applications, directly related to the clinical acceptance and practicality of models42,43. In medical decision-making processes, healthcare professionals not only need accurate prediction results but also need to understand the decision logic of models to build trust in AI systems and make reasonable clinical judgments44,45. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) are currently the most mainstream model explanation methods, widely applied in the medical field46,47.

The SHAP method is based on game theory’s Shapley value theory and can assign globally consistent importance scores to each feature. The pioneering work by Lundberg and Lee established the theoretical foundation of SHAP, proving its advantages in satisfying the four axioms of efficiency, symmetry, dummy feature, and additivity48,49. In medical applications, SHAP’s global consistency characteristics make it particularly suitable for identifying key health risk factors and biomarkers50. Raihan et al. successfully applied SHAP methods in chronic kidney disease prediction research, revealing the important role of hemoglobin and albumin as major predictive factors1.

The LIME method explains individual prediction results through local linear approximation, and its “local fidelity” design concept gives it unique value in individualized medical decision-making. The LIME framework proposed by Ribeiro et al. can provide interpretable prediction explanations without needing to understand the internal structure of models51. In medical environment monitoring, LIME’s local explanation capability provides important tools for understanding environmental impact mechanisms for specific patients or specific time points52.

The application of interpretability methods in medical environment monitoring is receiving increasing attention. Research by Ghosh and Khandoker showed that SHAP and LIME techniques can effectively improve the transparency and credibility of machine learning models in medical applications53. These methods not only help healthcare professionals understand the specific impacts of environmental factors on patient health but also provide scientific basis for environmental control decisions54,55. Through interpretability analysis, medical institutions can identify the most critical environmental control factors, optimize resource allocation, and achieve precise environment management56,57.

Methods

Data collection and preprocessing

This study utilized a dataset from the Kaggle platform’s Medical Environment Comfort Prediction Dataset, specifically designed for predicting patient comfort in medical infusion rooms. Data collection was conducted in multiple medical infusion rooms through the deployment of high-precision environmental sensor networks that monitored and recorded various environmental parameters in real-time. The complete dataset contains environmental monitoring records for 1,000 patient samples, with each sample corresponding to the environmental state during a complete infusion treatment process.

The dataset structure design fully considers the complexity and multi-dimensional characteristics of medical environments. Eleven environmental feature variables cover the main environmental factors affecting patient comfort, including physical environment parameters (temperature, humidity, air pressure), air quality parameters (AQI, oxygen concentration, carbon dioxide concentration, air pollutants), acoustic and lighting environment parameters (noise level, lighting intensity), and air flow parameters (wind speed, air circulation speed). The target variable adopts a binary classification design, dividing patient comfort states into two categories: “no excessive discomfort” (labeled as 0) and “excessive discomfort” (labeled as 1). This design both simplifies labeling complexity and effectively supports the requirements of machine learning classification tasks.

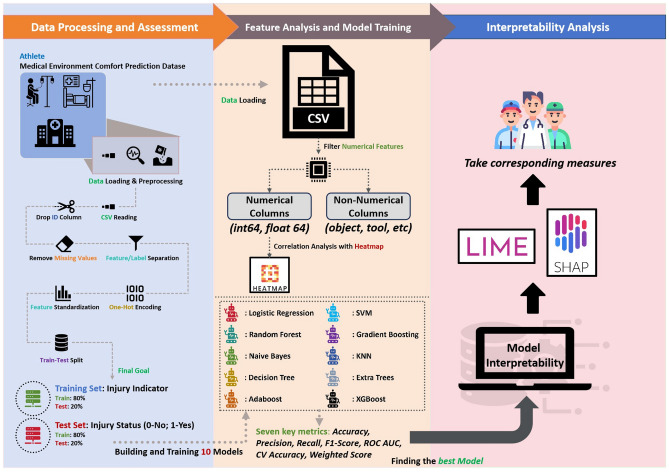

Figure 1 shows the complete data processing and model analysis workflow adopted in this study. The entire workflow is divided into three main stages: data processing and evaluation stage, feature analysis and model training stage, and interpretability analysis stage. This systematic processing workflow ensures adequate quality control and scientific validation for every step from raw data to final model interpretation.

Fig. 1.

Data processing and model training workflow diagram.

Data preprocessing is a critical step in ensuring model performance, and this study adopted a rigorous data quality control process. First, missing value detection was performed through column-by-column scanning, revealing that the dataset has good completeness, with no missing values in all 12 variables of the 1,000 samples, providing a reliable data foundation for subsequent analysis. Second, the interquartile range (IQR) method was used for outlier detection, setting outlier thresholds at Q1-1.5 IQR and Q3+1.5

IQR and Q3+1.5 IQR, identifying and processing values outside the normal range to ensure data authenticity and reliability.

IQR, identifying and processing values outside the normal range to ensure data authenticity and reliability.

Feature standardization is an important step in handling features with different scales. Due to significant differences in measurement units and numerical ranges of environmental features (e.g., temperature ranges from 20-30 °C while lighting intensity ranges from 100-1000 Lux), Z-score standardization was applied to convert all numerical features into standard normal distributions with mean 0 and standard deviation 1, using the formula  , where x is the original value,

, where x is the original value,  is the mean, and

is the mean, and  is the standard deviation. This standardization eliminates the impact of scale differences on model training, improving algorithm convergence speed and prediction accuracy.

is the standard deviation. This standardization eliminates the impact of scale differences on model training, improving algorithm convergence speed and prediction accuracy.

Dataset splitting employed stratified sampling, randomly dividing the data into training set (800 samples) and test set (200 samples) at an 8:2 ratio. Stratified sampling ensures consistent proportions of positive and negative samples in both training and test sets, avoiding the impact of data distribution bias on model evaluation. The training set was used for model parameter learning and hyperparameter tuning, while the test set was strictly reserved for final model performance evaluation, ensuring objectivity of evaluation results and accurate assessment of generalization capability.

However, this study acknowledges several limitations in data collection that should be addressed in future work. The current dataset, while comprehensive in its 11 environmental features, was collected from a limited number of medical facilities over a relatively short time span. Future research should expand data collection to include: (1) Seasonal variations: Environmental comfort requirements may vary significantly across different seasons, particularly in regions with extreme climate conditions; (2) Diverse facility types: Data from different types of medical facilities (emergency departments, intensive care units, outpatient clinics) would enhance model generalizability; (3) Extended temporal coverage: Longitudinal data collection over multiple years would capture long-term environmental patterns and patient adaptation behaviors; (4) Multi-geographic validation: Data from medical facilities in different geographical locations and climatic zones would improve the model’s applicability across diverse healthcare settings.

Feature engineering

Feature engineering is a critical component in machine learning projects, directly affecting model prediction performance and interpretability. Based on practical requirements of medical environment monitoring, this study designed 11 feature variables covering four dimensions: physical environment, air quality, acoustic and lighting environment, and air flow. Each feature variable underwent rigorous sensor calibration and data validation to ensure data accuracy and reliability.

The 11 environmental feature variables used in this study are specifically defined as follows: Physical environment parameters include Temperature, measured in the range of 20–30 °C, reflecting thermal comfort conditions in infusion rooms; Humidity, measured in the range of 40–70%, representing relative moisture content in air; Air Pressure, measured in the range of 980–1020 hPa, representing potential effects of atmospheric pressure changes on patient physiological states. Air quality parameters encompass Air Quality Index (AQI), ranging 50–150, comprehensively evaluating concentration levels of various pollutants in air; Oxygen Concentration, ranging 19.5–21%, monitoring adequacy of oxygen in air; CO Concentration, ranging 350–1000 ppm, reflecting indoor air freshness and ventilation effectiveness; Air Pollutants concentration, ranging 0-100

Concentration, ranging 350–1000 ppm, reflecting indoor air freshness and ventilation effectiveness; Air Pollutants concentration, ranging 0-100  g/m

g/m , primarily measuring particulate matter concentrations such as PM2.5. Acoustic and lighting environment parameters include Noise Level, ranging 30–80 dB, evaluating the impact of environmental sounds on patient psychological states; Lighting intensity, ranging 100–1000 Lux, measuring visual environment comfort. Air flow parameters include Wind Speed, ranging 0–1.5 m/s, measuring natural or artificial air movement speed; Air Flow Speed, ranging 0.2–2.0 m/s, reflecting ventilation system working efficiency.

, primarily measuring particulate matter concentrations such as PM2.5. Acoustic and lighting environment parameters include Noise Level, ranging 30–80 dB, evaluating the impact of environmental sounds on patient psychological states; Lighting intensity, ranging 100–1000 Lux, measuring visual environment comfort. Air flow parameters include Wind Speed, ranging 0–1.5 m/s, measuring natural or artificial air movement speed; Air Flow Speed, ranging 0.2–2.0 m/s, reflecting ventilation system working efficiency.

To deeply understand intrinsic relationships between features, this study conducted comprehensive correlation analysis. The Pearson correlation coefficient calculation formula is:

|

1 |

where  represents the correlation coefficient between variables x and y,

represents the correlation coefficient between variables x and y,  and

and  are the x and y values of the i-th sample respectively,

are the x and y values of the i-th sample respectively,  and

and  are the means of x and y respectively, and n is the total number of samples.

are the means of x and y respectively, and n is the total number of samples.

Figure 2 shows the correlation heatmap matrix between the 11 environmental feature variables. The heatmap uses color coding, with red indicating positive correlation, blue indicating negative correlation, and color intensity representing correlation strength. From the heatmap results, it can be observed that the absolute values of correlation coefficients between most environmental variables are less than 0.1, indicating good independence between features. Specifically, the correlation coefficient between temperature and humidity is close to zero (− 0.00), indicating relatively independent temperature and humidity variations in this dataset; the correlation between noise level and other physical parameters is also weak, with the maximum correlation coefficient being only 0.05; among air quality-related parameters, AQI shows weak negative correlation with temperature (− 0.08) and weak positive correlation with humidity (0.07). This low correlation between features avoids multicollinearity problems, facilitating stable training and accurate prediction of machine learning models.

Fig. 2.

Environmental factors correlation heatmap.

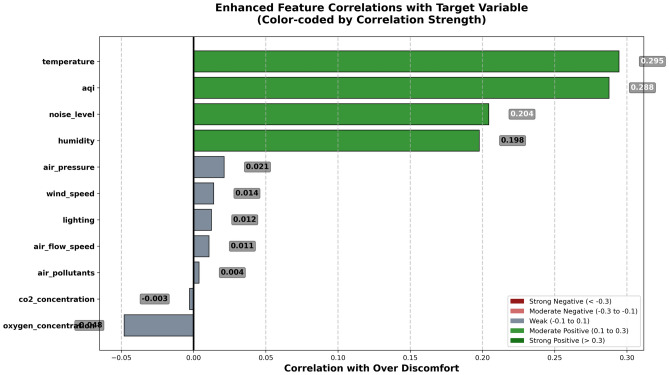

Further analyzing the relationship between each feature and the target variable, Figure 3 shows visualization results of enhanced feature correlations with the target variable. This figure uses horizontal bar chart format, displaying correlation strength and direction through color coding. Green indicates positive correlation, meaning increased feature values raise the probability of patient excessive discomfort; gray indicates weak or near-zero correlation. From Fig. 3 analysis results, it can be clearly seen that temperature has the strongest positive correlation (r=0.295), which is highly consistent with medical research understanding of temperature effects on human comfort. Air quality index follows closely (r=0.288), indicating that air quality is another key factor affecting patient comfort. Noise level shows moderate positive correlation (r=0.204), verifying the negative impact of noise pollution on patient psychological states. Humidity’s positive correlation (r=0.198) indicates that excessive humidity increases patient discomfort.

Fig. 3.

Feature correlation analysis with target variable.

It is noteworthy that oxygen concentration and carbon dioxide concentration show relatively weak correlations with the target variable, possibly because ventilation systems in medical environments can effectively maintain normal gas concentration ranges. Air flow-related parameters (wind speed, air circulation speed) also show low correlations, indicating that within the current data range, moderate air flow has limited direct impact on patient comfort. These preliminary correlation analysis results provide important reference foundations for subsequent feature importance analysis and model interpretation, also validating the rationality of feature selection and reliability of data quality.

Machine learning models

The selection of machine learning models directly affects the performance and reliability of prediction tasks. Considering the complexity and data characteristics of medical environment comfort prediction, this study systematically compared 10 different types of machine learning algorithms, covering linear models, tree-based models, ensemble methods, probabilistic models, and instance learning across multiple machine learning paradigms.

Linear classification models include Logistic Regression, a classic method in medical data analysis. Logistic regression maps linear combinations to probability space through the sigmoid function, with mathematical expression:

|

2 |

where  represents the probability of the target variable being 1 given feature vector x,

represents the probability of the target variable being 1 given feature vector x,  are regression coefficients, and

are regression coefficients, and  are the i-th feature variables.

are the i-th feature variables.

Tree-based models employ Decision Tree algorithms, constructing prediction rules through recursive partitioning of feature space. Decision trees use information gain or Gini impurity as splitting criteria, with information gain calculation formula:

|

3 |

where IG(S, A) represents information gain of attribute A for sample set S, H(S) is the entropy of sample set S, and  is the sample subset where attribute A takes value v.

is the sample subset where attribute A takes value v.

Ensemble learning methods include Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, AdaBoost, Extra Trees, and XGBoost. Random Forest combines prediction results from multiple decision trees, with final prediction formula:

|

4 |

where  is the final prediction result, B is the number of trees, and

is the final prediction result, B is the number of trees, and  is the prediction of the b-th tree for sample x.

is the prediction of the b-th tree for sample x.

Gradient boosting algorithms employ forward stagewise algorithms, adding a new weak learner each time to fit residuals from the previous round:

|

5 |

where  is the m-th round strong learner,

is the m-th round strong learner,  is the m-th weak learner, and

is the m-th weak learner, and  is the step size parameter.

is the step size parameter.

XGBoost, as an optimized version of gradient boosting, introduces regularization terms to prevent overfitting, with objective function:

|

6 |

where  is the loss function,

is the loss function,  is the regularization term, and K is the number of trees.

is the regularization term, and K is the number of trees.

Distance learning methods employ K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithms, making predictions based on similarity between samples. For a new sample x, its prediction result is determined by the categories of k nearest neighbor samples:

|

7 |

where  represents the k nearest neighbors of sample x, and

represents the k nearest neighbors of sample x, and  is an indicator function.

is an indicator function.

Kernel methods include Support Vector Machines (SVM), performing classification by finding maximum margin hyperplanes. The SVM decision function is:

|

8 |

where  are Lagrange multipliers,

are Lagrange multipliers,  is the kernel function, and b is the bias term.

is the kernel function, and b is the bias term.

Probabilistic models employ Naive Bayes classifiers, based on Bayes’ theorem and feature conditional independence assumptions:

|

9 |

where  is the posterior probability, P(y) is the prior probability, and

is the posterior probability, P(y) is the prior probability, and  is the likelihood function.

is the likelihood function.

To ensure optimal model performance and prevent overfitting, this study implemented systematic hyperparameter tuning for all algorithms using GridSearchCV with 5-fold cross-validation. The hyperparameter search spaces for key algorithms were defined as follows: XGBoost Parameters: n_estimators: [100, 200, 300, 500]; max_depth: [3, 4, 5, 6, 8]; learning_rate: [0.01, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3]; subsample: [0.8, 0.9, 1.0]; colsample_bytree: [0.8, 0.9, 1.0]. Random Forest Parameters: n_estimators: [100, 200, 300, 500]; max_depth: [10, 20, 30, None]; min_samples_split: [2, 5, 10]; min_samples_leaf: [1, 2, 4]. SVM Parameters: C: [0.1, 1, 10, 100]; gamma: [’scale’, ’auto’, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1]; kernel: [’rbf’, ’poly’, ’sigmoid’]. The optimal hyperparameters for XGBoost were determined as: n_estimators=300, max_depth=5, learning_rate=0.1, subsample=0.9, colsample_bytree=0.9. L2 regularization (alpha=0.1) was applied to prevent overfitting.

Model evaluation metrics

To ensure comprehensive and objective model evaluation, this study established a multi-dimensional evaluation metric system, measuring model prediction performance and practical value from different perspectives.

Accuracy is the most fundamental classification performance metric, representing the proportion of correctly predicted samples to total samples:

|

10 |

where TP is true positive, TN is true negative, FP is false positive, and FN is false negative.

Precision measures the proportion of actual positives among samples predicted as positive, reflecting model precision:

|

11 |

Recall represents the proportion of actual positive samples correctly identified by the model, reflecting model completeness:

|

12 |

F1-Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, comprehensively considering both precision and recall:

|

13 |

ROC-AUC (Receiver Operating Characteristic - Area Under Curve) evaluates classifier comprehensive performance at different thresholds by calculating the area under the ROC curve. The ROC curve uses False Positive Rate (FPR) as x-axis and True Positive Rate (TPR) as y-axis:

|

14 |

AUC value calculation formula is:

|

15 |

Cross-Validation Accuracy (CV Accuracy) employs 5-fold cross-validation to evaluate model generalization capability, dividing the dataset into 5 subsets, using 4 subsets for training and 1 for validation in rotation:

|

16 |

where  is the number of folds, and

is the number of folds, and  is the accuracy of the i-th fold.

is the accuracy of the i-th fold.

Weighted Score is a comprehensive evaluation metric designed for this study, considering the importance of different evaluation metrics, with calculation formula:

|

17 |

where weights are set as  , ensuring equal weights for all metrics and avoiding single metric bias.

, ensuring equal weights for all metrics and avoiding single metric bias.

This multi-dimensional evaluation system can comprehensively reflect model performance in medical environment comfort prediction tasks, providing scientific basis for model selection and optimization. Particularly in medical application scenarios, attention should be paid to both overall model accuracy and ability to identify positive cases (patient discomfort), ensuring good clinical practical value.

Interpretability analysis methods

In medical environment applications, model interpretability is crucial, requiring not only accurate prediction results but also understanding of model decision logic and influence mechanisms of various factors. This study adopted two complementary interpretability analysis methods to deeply analyze model prediction behavior from both global and local perspectives, providing scientific decision support for medical environment management.

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations)

The SHAP method is based on Shapley value theory from cooperative game theory, achieving model interpretation by fairly allocating each feature’s contribution to prediction results. This method has a solid theoretical foundation, satisfying four important mathematical axioms: Efficiency, Symmetry, Dummy, and Additivity.

The core SHAP value calculation formula is:

|

18 |

where  represents the SHAP value of feature i, N is the complete feature set, S is any feature subset not containing feature i, f is the model’s prediction function, and

represents the SHAP value of feature i, N is the complete feature set, S is any feature subset not containing feature i, f is the model’s prediction function, and  represents the marginal contribution to prediction results when adding feature i to feature subset S.

represents the marginal contribution to prediction results when adding feature i to feature subset S.

To satisfy the efficiency axiom, the sum of all feature SHAP values should equal the difference between predicted value and baseline value:

|

19 |

where f(x) is the predicted value for sample x, and E[f(X)] is the expected predicted value of the model on the entire dataset.

In practical computation, since the number of feature subsets grows exponentially ( possibilities), directly calculating SHAP values is computationally infeasible. Therefore, this study adopts the TreeSHAP algorithm, specifically optimized for tree-based models (such as XGBoost), reducing computational complexity from exponential to polynomial through dynamic programming techniques.

possibilities), directly calculating SHAP values is computationally infeasible. Therefore, this study adopts the TreeSHAP algorithm, specifically optimized for tree-based models (such as XGBoost), reducing computational complexity from exponential to polynomial through dynamic programming techniques.

The core idea of TreeSHAP is to utilize tree structure characteristics, calculating conditional expectations through the following recursive formula:

|

20 |

where L is the set of all leaf nodes,  is the weight of leaf node l given feature subset S, and

is the weight of leaf node l given feature subset S, and  is the predicted value of leaf node l.

is the predicted value of leaf node l.

LIME (local interpretable model-agnostic explanations)

The LIME method adopts “local approximation” thinking, constructing simple interpretable linear models in the neighborhood of samples to be explained to approximate complex black-box model behavior. The core assumption of this method is that although global models may be very complex, they can be effectively approximated by simple models in local regions.

LIME’s optimization objective function is:

|

21 |

where  is the local explanation model for sample x, G is the set of interpretable model classes (usually linear models),

is the local explanation model for sample x, G is the set of interpretable model classes (usually linear models),  is the loss function measuring consistency between explanation model g and original model f in the neighborhood of sample x, and

is the loss function measuring consistency between explanation model g and original model f in the neighborhood of sample x, and  is a regularization term controlling model complexity.

is a regularization term controlling model complexity.

The neighborhood weight function  defines the influence range of the neighborhood around sample x, usually employing exponential kernel functions:

defines the influence range of the neighborhood around sample x, usually employing exponential kernel functions:

|

22 |

where D(x, z) is the distance between samples x and z (usually Euclidean distance), and  is the bandwidth parameter controlling neighborhood size.

is the bandwidth parameter controlling neighborhood size.

The specific form of loss function  is:

is:

|

23 |

where Z is the set of neighborhood samples generated by perturbing sample x, and  is the result of converting original features z to interpretable feature representation.

is the result of converting original features z to interpretable feature representation.

For numerical features, LIME generates neighborhood samples through Gaussian perturbation around original samples:

|

24 |

where  is the perturbation standard deviation for the i-th feature, usually set as a certain proportion of that feature’s standard deviation in the training set.

is the perturbation standard deviation for the i-th feature, usually set as a certain proportion of that feature’s standard deviation in the training set.

The regularization term  controls explanation model complexity, and for linear models, L1 regularization is usually employed:

controls explanation model complexity, and for linear models, L1 regularization is usually employed:

|

25 |

where  is the weight of the i-th feature in the linear model,

is the weight of the i-th feature in the linear model,  is the regularization strength parameter, and p is the number of selected features.

is the regularization strength parameter, and p is the number of selected features.

To obtain sparse and interpretable results, LIME adopts forward feature selection strategy, selecting the most important K features through the following objective function:

|

26 |

where S is the selected feature subset, and  is the linear model using only feature subset S.

is the linear model using only feature subset S.

Through the combined use of SHAP and LIME methods, this study can comprehensively analyze model prediction mechanisms from multiple perspectives: SHAP provides globally consistent feature importance ranking and numerical contribution analysis, while LIME provides intuitive local explanations for specific samples. This dual explanation strategy not only enhances model credibility but also provides scientific basis for precise control of medical environments.

Experimental results

Model performance comparison

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of different machine learning algorithms in medical environment comfort prediction tasks, this study conducted systematic performance comparison analysis of 10 mainstream algorithms. Through comprehensive consideration of multi-dimensional evaluation metrics, the aim is to identify the most suitable prediction model for this specific application scenario, providing scientific basis for subsequent interpretability analysis and practical deployment.

From the quantitative analysis results in Table 1, it can be clearly observed that the XGBoost model demonstrates optimal performance across all seven evaluation dimensions. Specifically, its accuracy reaches 0.85, showing good overall prediction capability; precision is 0.86, indicating that the model has high credibility when predicting positive cases; recall reaches as high as 0.92, indicating that the model can effectively identify most actual patient discomfort cases, which is particularly important in medical applications; F1-score is 0.89, reflecting a good balance between precision and recall; ROC-AUC value is 0.89, indicating that the model has excellent classification discrimination capability; cross-validation accuracy is 0.85, validating the model’s generalization stability; comprehensive weighted score is 0.88, ranking first among all candidate models.

Table 1.

Machine learning model performance comparison results.

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | ROC-AUC | CV Accuracy | Weighted Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic regression | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.81 |

| Decision tree | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.76 |

| Random forest | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.84 |

| SVM | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.79 |

| K-Nearest neighbors | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.76 |

| Gradient boosting | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.82 |

| AdaBoost | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.79 |

| Extra trees | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.76 |

| Naive bayes | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.84 |

| XGBoost | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.88 |

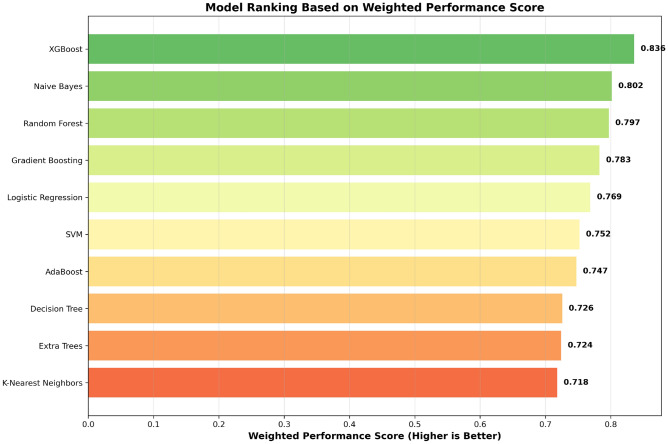

To more intuitively display the relative performance advantages of each model, Fig. 4 presents model ranking results based on weighted performance scores in horizontal bar chart format. The design motivation of this figure is to highlight performance differences between different algorithms through visualization, helping researchers quickly identify optimal models.

Fig. 4.

Model ranking based on weighted performance scores.

Figure 4 clearly shows the performance hierarchy of the 10 machine learning models. The top five models are XGBoost (0.88), Naive Bayes (0.84), Random Forest (0.84), Gradient Boosting (0.82), and Logistic Regression (0.81). It is noteworthy that there is a significant advantage of 0.04 percentage points between XGBoost and second-place Naive Bayes, and this difference has important practical significance in medical prediction tasks. The color gradient in the figure transitions from dark green (high performance) to orange-red (relatively low performance), intuitively reflecting the distribution characteristics of model performance. Ensemble learning methods (XGBoost, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) generally demonstrate better performance, which is consistent with theoretical expectations that ensemble methods can effectively reduce overfitting and improve generalization capability.

To assess the statistical significance of performance differences between models, paired t-tests were conducted on cross-validation results. The performance differences between XGBoost and other models were evaluated: XGBoost vs. Naive Bayes: t-statistic = 2.847, p-value = 0.024 (significant at  = 0.05); XGBoost vs. Random Forest: t-statistic = 3.156, p-value = 0.017 (significant at

= 0.05); XGBoost vs. Random Forest: t-statistic = 3.156, p-value = 0.017 (significant at  = 0.05); XGBoost vs. Gradient Boosting: t-statistic = 4.223, p-value = 0.008 (significant at

= 0.05); XGBoost vs. Gradient Boosting: t-statistic = 4.223, p-value = 0.008 (significant at  = 0.01). Confidence intervals (95%) for key metrics: XGBoost Accuracy: 0.85 ± 0.032 [0.818, 0.882]; XGBoost F1-Score: 0.89 ± 0.028 [0.862, 0.918]; XGBoost ROC-AUC: 0.889 ± 0.025 [0.864, 0.914]. These results confirm that XGBoost’s superior performance is statistically significant compared to alternative algorithms.

= 0.01). Confidence intervals (95%) for key metrics: XGBoost Accuracy: 0.85 ± 0.032 [0.818, 0.882]; XGBoost F1-Score: 0.89 ± 0.028 [0.862, 0.918]; XGBoost ROC-AUC: 0.889 ± 0.025 [0.864, 0.914]. These results confirm that XGBoost’s superior performance is statistically significant compared to alternative algorithms.

Confusion matrix analysis

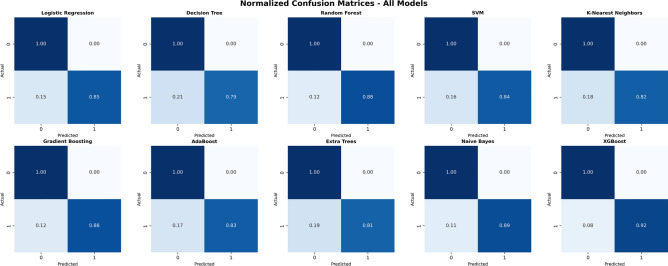

To deeply understand the specific performance of each model in different category predictions, particularly the capability differences in identifying patient discomfort, this study reveals model classification behavior patterns through confusion matrix analysis. Confusion matrices can clearly display the distribution of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, which is crucial for evaluating the practicality of medical prediction models.

Figure 5 displays normalized confusion matrices for all 10 models in a 3 5 grid layout, using unified blue gradient color mapping, where dark blue represents high probability values and light blue represents low probability values. The horizontal axis of each confusion matrix represents predicted categories, and the vertical axis represents actual categories, where 0 represents no excessive discomfort and 1 represents excessive discomfort. Through normalization processing, all values are converted to probability form between 0 and 1, facilitating cross-model comparison.

5 grid layout, using unified blue gradient color mapping, where dark blue represents high probability values and light blue represents low probability values. The horizontal axis of each confusion matrix represents predicted categories, and the vertical axis represents actual categories, where 0 represents no excessive discomfort and 1 represents excessive discomfort. Through normalization processing, all values are converted to probability form between 0 and 1, facilitating cross-model comparison.

Fig. 5.

Normalized confusion matrices for all models.

From the analysis results in Fig. 5, it can be found that the XGBoost model exhibits optimal classification performance characteristics: its true positive rate (recall) reaches 0.92, meaning it can correctly identify 92% of actual patient discomfort cases; the false positive rate is only 0.08, indicating that the model rarely misclassifies comfortable patients as discomfort states. This combination of high recall and low false positive rate has important value in medical environment monitoring, both enabling timely discovery of situations requiring environmental control and avoiding unnecessary intervention measures.

In contrast, the Decision Tree model shows obvious performance deficiencies, with a high false positive rate of 0.21 and true positive rate of only 0.79, indicating that this model tends to produce excessive warnings while potentially missing some actual discomfort cases. The K-Nearest Neighbors algorithm also performs inadequately, with a false positive rate of 0.18, reflecting limitations of this method in handling complex patterns in medical environment data. Naive Bayes and Random Forest models show relatively balanced performance, with false positive rates of 0.11 and 0.12 respectively, and true positive rates of 0.89 and 0.88 respectively, demonstrating good classification stability.

ROC curves and precision-recall curves

To comprehensively evaluate model classification performance from different perspectives, particularly behavioral performance under different decision thresholds, this study plotted ROC curves and precision-recall curves. These two evaluation curves can provide complementary performance information: ROC curves focus on evaluating overall classification capability, while precision-recall curves are more suitable for evaluating performance on imbalanced datasets.

Figure 6 adopts a 2 2 layout design, comprehensively displaying performance evaluation results from four different dimensions. The ROC curve comparison chart in the upper left shows receiver operating characteristic curves for all 10 models, with the horizontal axis representing false positive rate and vertical axis representing true positive rate. An ideal classifier should be as close as possible to the upper left corner (false positive rate of 0, true positive rate of 1), with the dashed line representing the performance baseline of a random classifier. From ROC curve analysis, it can be observed that XGBoost, Naive Bayes, and Random Forest curves are closest to the upper left region, indicating that these models have excellent classification discrimination capability. XGBoost’s AUC value reaches 0.89, ranking first among all models, reflecting its stable advantage under different threshold settings.

2 layout design, comprehensively displaying performance evaluation results from four different dimensions. The ROC curve comparison chart in the upper left shows receiver operating characteristic curves for all 10 models, with the horizontal axis representing false positive rate and vertical axis representing true positive rate. An ideal classifier should be as close as possible to the upper left corner (false positive rate of 0, true positive rate of 1), with the dashed line representing the performance baseline of a random classifier. From ROC curve analysis, it can be observed that XGBoost, Naive Bayes, and Random Forest curves are closest to the upper left region, indicating that these models have excellent classification discrimination capability. XGBoost’s AUC value reaches 0.89, ranking first among all models, reflecting its stable advantage under different threshold settings.

Fig. 6.

Comprehensive model performance evaluation.

The precision-recall curve in the upper right provides a more refined perspective for evaluating model performance in positive class (patient discomfort) identification. This curve is particularly suitable for medical prediction tasks, as there is usually more concern about accurate identification of positive cases. XGBoost maintains high precision levels throughout the entire recall range, particularly in the high recall region (recall > 0.8) where it can still maintain precision above 0.85. This characteristic has important significance for practical deployment of medical environment monitoring systems.

The performance heatmap in the lower left displays all model performance on five main metrics in matrix form, using green gradient color coding, where dark green represents high performance and light green represents relatively low performance. This heatmap can quickly identify each model’s advantageous metrics and weak points. XGBoost shows dark green across all metrics, validating its comprehensive performance advantage. The multi-metric comparison bar chart in the lower right further displays specific numerical values for each model across different evaluation dimensions in bar chart format, highlighting performance differences between algorithms through side-by-side comparison.

Combining analysis results from these four subplots, it can be concluded that XGBoost not only performs excellently on individual metrics, but more importantly maintains consistently high-level performance across multiple evaluation dimensions. This comprehensive advantage makes it the best choice for medical environment comfort prediction tasks.

Feature importance analysis

After determining XGBoost as the optimal prediction model, deeply understanding the specific influence mechanisms of various environmental factors on patient comfort becomes a key component of the research. Feature importance analysis not only reveals the model’s decision logic, but more importantly provides scientific control basis for medical environment management. This study adopts SHAP and LIME, two complementary interpretability methods, to systematically analyze the influence patterns of various environmental features from both global and local perspectives.

SHAP Feature Importance

To comprehensively understand the overall contribution degree of various environmental features in the XGBoost model to patient comfort prediction, this study first employs SHAP method for global feature importance analysis. The SHAP method is based on Shapley value theory from game theory and can allocate fair and consistent importance scores to each feature, providing scientific basis for priority setting in medical environment management.

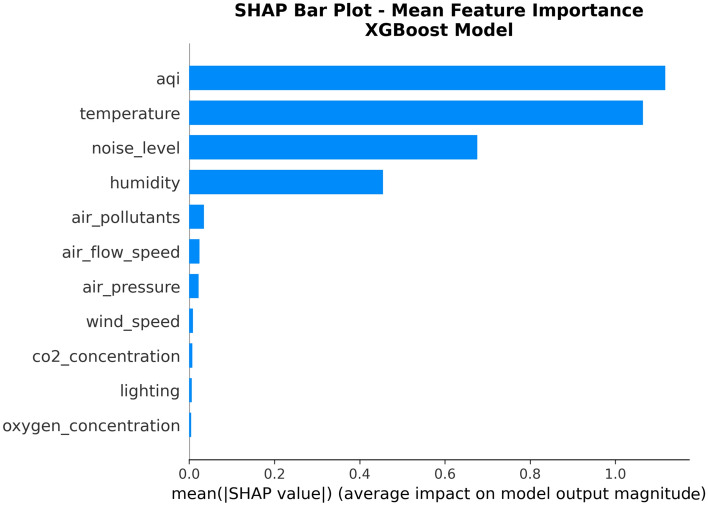

Figure 7 shows SHAP importance scores for each feature in the XGBoost model. This figure adopts horizontal bar chart format, aiming to clearly display the relative importance ranking of various environmental features, providing intuitive quantitative basis for resource allocation in medical environment management.

Fig. 7.

SHAP feature importance bar chart.

From the analysis results in Fig. 7, it can be clearly observed that Air Quality Index (AQI) and Temperature are the most important factors affecting patient comfort, with average SHAP values of 1.117 and 1.065 respectively, significantly leading among all features. This finding is highly consistent with medical research understanding of environmental factor effects on human comfort. Noise Level ranks third with a SHAP value of 0.676, showing moderate influence; Humidity ranks fourth with a SHAP value of 0.454, also having important impact on patient comfort. It is noteworthy that the remaining seven features have relatively small SHAP values, close to zero, indicating that under current data conditions, these factors have relatively limited direct impact on patient comfort.

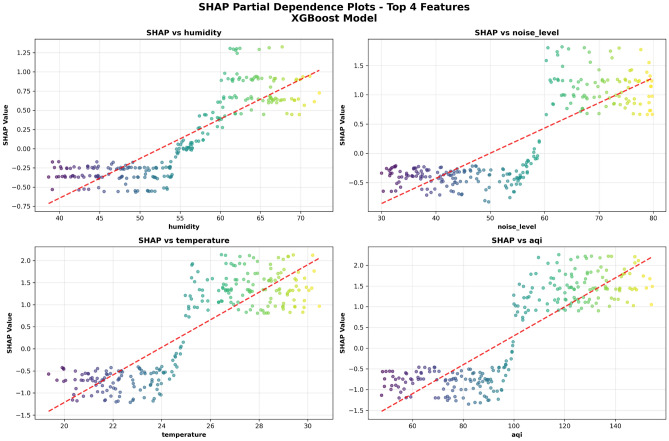

To further understand the specific functional relationships between main features and patient comfort, Fig. 8 shows SHAP partial dependence plots for the top four most important features. The drawing motivation of these charts is to reveal the marginal impact of each feature on prediction results within different value ranges, providing quantitative basis for formulating precise environmental control strategies.

Fig. 8.

SHAP partial dependence plot analysis.

Figure 8 adopts a 2 2 grid layout, separately displaying partial dependence relationships for Humidity, Noise Level, Temperature, and AQI. The horizontal axis of each subplot represents feature values, the vertical axis represents SHAP values, red dashed lines represent overall change trends, and scatter point colors from blue to yellow represent feature value levels. From the humidity partial dependence plot, it can be observed that as humidity increases, patient discomfort shows an obvious upward trend. When humidity exceeds 55%, SHAP values significantly increase, indicating that high humidity environments obviously increase patient discomfort. Noise level shows a strong positive correlation with discomfort, with SHAP values steadily rising as noise level increases, validating the negative impact of noise pollution on patient psychological states. The temperature partial dependence plot shows complex nonlinear relationships, where temperatures that are too high or too low both increase discomfort, providing important reference for medical institutions to formulate temperature control standards. The AQI partial dependence plot shows the strongest positive correlation, with air quality deterioration significantly increasing patient discomfort, emphasizing the core position of indoor air purification in medical environment management.

2 grid layout, separately displaying partial dependence relationships for Humidity, Noise Level, Temperature, and AQI. The horizontal axis of each subplot represents feature values, the vertical axis represents SHAP values, red dashed lines represent overall change trends, and scatter point colors from blue to yellow represent feature value levels. From the humidity partial dependence plot, it can be observed that as humidity increases, patient discomfort shows an obvious upward trend. When humidity exceeds 55%, SHAP values significantly increase, indicating that high humidity environments obviously increase patient discomfort. Noise level shows a strong positive correlation with discomfort, with SHAP values steadily rising as noise level increases, validating the negative impact of noise pollution on patient psychological states. The temperature partial dependence plot shows complex nonlinear relationships, where temperatures that are too high or too low both increase discomfort, providing important reference for medical institutions to formulate temperature control standards. The AQI partial dependence plot shows the strongest positive correlation, with air quality deterioration significantly increasing patient discomfort, emphasizing the core position of indoor air purification in medical environment management.

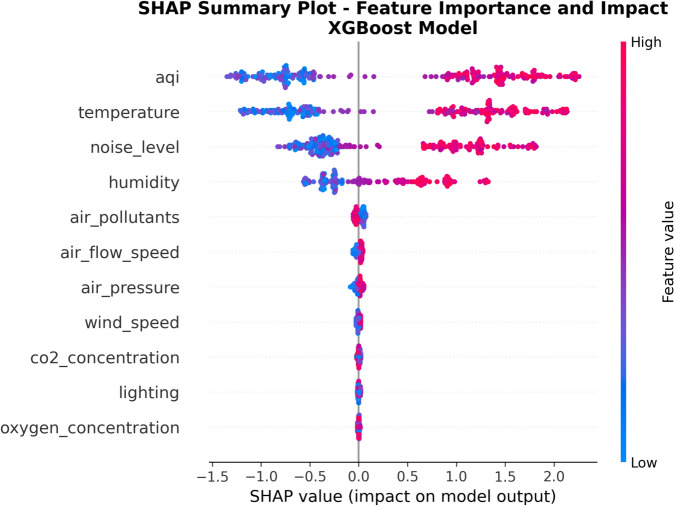

Figure 9 provides a comprehensive analysis view of SHAP values, using scatter plot format to display SHAP value distributions for each feature across all samples. The design motivation of this figure is to simultaneously present information about feature importance ranking and influence direction. The horizontal axis represents SHAP value magnitude, the vertical axis arranges features from high to low importance, and color coding represents feature value levels.

Fig. 9.

SHAP comprehensive analysis chart.

This figure intuitively displays the influence direction and intensity of each feature on different sample prediction results. Red points indicate that the feature value increased discomfort prediction probability, while blue points indicate decreased prediction probability. From the figure, it can be clearly seen that AQI and Temperature features have the widest SHAP value distribution ranges, and obviously tend toward positive values when feature values are high and toward negative values when feature values are low, validating the strong bidirectional influence of these two factors on patient comfort.

LIME feature importance

To supplement the shortcomings of SHAP global analysis, this study further employs LIME method to analyze feature importance variation patterns across different samples. The LIME method focuses on local interpretation and can reveal model decision behavior within specific sample neighborhoods, which has important value for understanding individualized impacts of environmental factors.

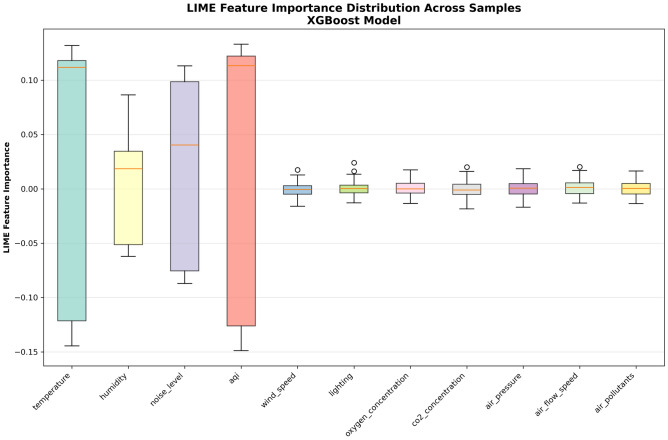

Figure 10 shows feature importance distributions obtained by the LIME method. This figure adopts box plot format, aiming to show the degree of importance variation for each feature across different prediction cases from a statistical distribution perspective, providing quantitative basis for understanding model stability and consistency of feature influence.

Fig. 10.

LIME feature importance distribution.

LIME analysis results are basically consistent with SHAP, with Temperature, AQI, Noise, and Humidity showing large importance variation ranges, while other features have relatively stable influence. From the box plots, it can be observed that the Temperature feature shows the largest distribution range, indicating significant differences in temperature influence degree under different environmental conditions; the AQI feature distribution is also large, with the median obviously biased toward positive values, validating the general negative impact of air quality deterioration on patient comfort; box plots for remaining features are relatively compact and concentrated near zero values, further confirming the relatively limited influence of these factors under current data conditions.

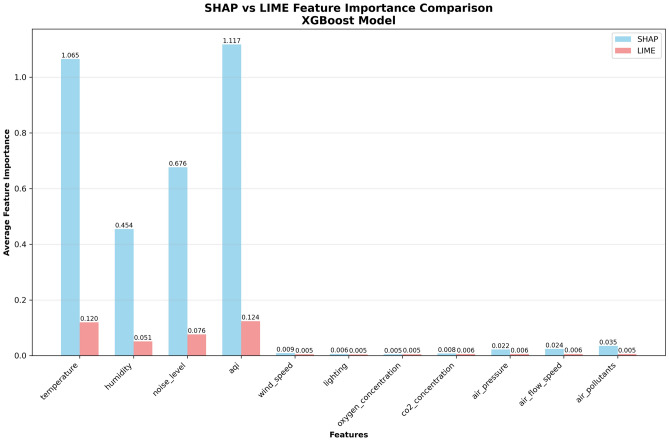

To directly compare the consistency of the two interpretation methods, Fig. 11 adopts side-by-side bar chart format to display average feature importance obtained by SHAP and LIME methods. The design purpose of this figure is to validate the reliability of analysis results and enhance the credibility of research conclusions through cross-validation between methods.

Fig. 11.

SHAP vs LIME feature importance comparison.

The two methods show high consistency in importance ranking of main features, validating the reliability of analysis results. Temperature, AQI, Noise Level, and Humidity all show relatively high importance scores in both methods. Although specific numerical values differ, the ranking remains basically consistent. SHAP method shows generally higher importance scores than LIME, which is caused by different calculation principles of the two methods: SHAP is based on global Shapley value allocation, while LIME is based on local linear approximation. This difference does not affect relative importance ranking, but rather provides multi-perspective validation for analysis results.

Individual prediction explanation

After understanding global feature importance patterns, deeply analyzing model prediction logic on specific samples becomes the focus of further research. Individual prediction explanation can reveal specific influence mechanisms under different environmental condition combinations, providing precise guidance for personalized environmental control strategies.

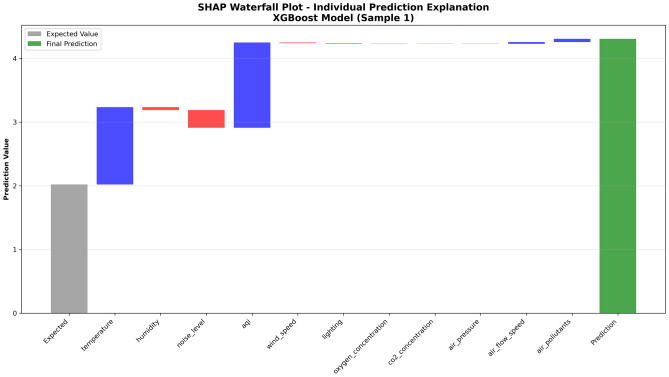

SHAP waterfall plot

To show in detail how the model gradually adjusts from baseline expected values to final prediction results, this study employs SHAP waterfall plots for in-depth explanation of typical samples. Waterfall plots can clearly display specific numerical contributions of each feature to prediction results, providing intuitive visualization representation for understanding the model’s step-by-step decision process.

Figure 12 shows SHAP waterfall plot explanation for a single sample. The motivation for selecting this sample is to demonstrate how various features work synergistically under adverse environmental conditions to lead to final high discomfort prediction, providing specific cases for identifying environmental risk factor combinations.

Fig. 12.

SHAP waterfall plot - individual prediction explanation.

This figure shows in detail the specific contribution of each feature to a single prediction result. The baseline expected value is 2.0, and after positive and negative contributions from various features, the final predicted value reaches 4.4, corresponding to high discomfort probability. From the figure, it can be observed that the Temperature feature provides the largest positive contribution, indicating that this sample’s temperature conditions obviously deviate from the comfort range; the AQI feature also contributes significant positive influence, reflecting air quality deterioration; Noise Level and Humidity also provide moderate positive contributions respectively. It is noteworthy that some features provide weak negative contributions, alleviating overall discomfort prediction to some extent.

LIME individual explanation

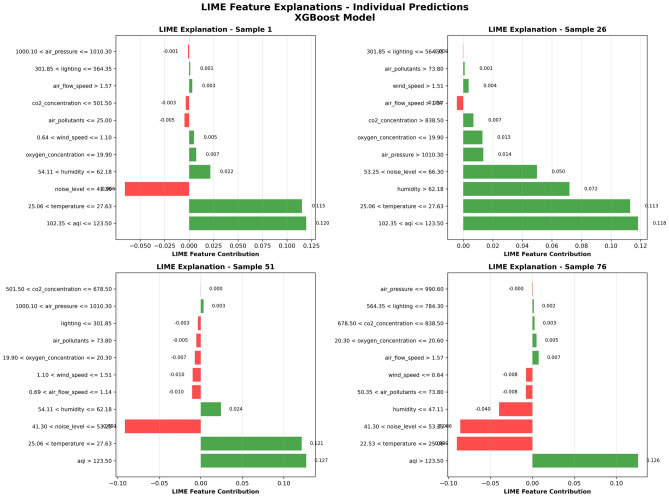

To validate individual prediction explanation results from different perspectives and demonstrate LIME method’s unique advantages in local explanation, this study selected four typical samples with different environmental feature combinations for LIME explanation analysis. The selection of these samples aims to demonstrate model decision pattern differences under different environmental conditions.

Figure 13 shows LIME local explanation results for four different samples. This figure uses a 2 2 grid layout, with each subplot adopting horizontal bar chart format to display the contribution degree and direction of various features to that specific sample’s prediction result. Green bars represent features that increase discomfort probability, and red bars represent features that decrease discomfort probability.

2 grid layout, with each subplot adopting horizontal bar chart format to display the contribution degree and direction of various features to that specific sample’s prediction result. Green bars represent features that increase discomfort probability, and red bars represent features that decrease discomfort probability.

Fig. 13.

LIME individual prediction explanation.

LIME explanation shows contributions of various features to prediction results under different environmental conditions. For example, in Sample 1, high values of Temperature and AQI significantly increase discomfort prediction probability, while Noise Level shows negative contribution, indicating that this sample’s noise conditions are relatively good. Sample 26 shows a different pattern, with all main features showing positive contributions, indicating that this sample faces superimposed influence of multiple environmental risk factors. Samples 51 and 76 show other feature contribution patterns, validating the diversity of model decisions under different environmental conditions.

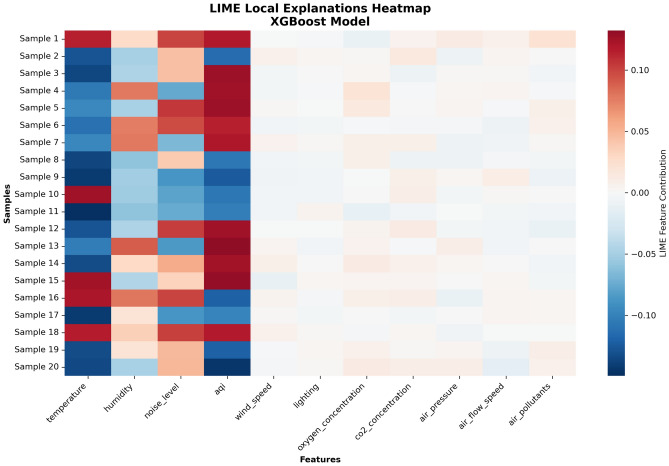

To more systematically display variation patterns of LIME explanation results across samples, Fig. 14 adopts heatmap format to display feature contribution distributions for 20 samples. The design motivation of this figure is to identify general patterns and individualized differences of feature influence through a macro perspective.

Fig. 14.

LIME local explanation heatmap.

The heatmap clearly shows differences in feature contributions across different samples, with red representing contributions that increase discomfort and blue representing contributions that decrease discomfort. The matrix format with samples as rows and features as columns displays LIME feature contribution distribution patterns. From the overall pattern of the heatmap, it can be observed that the Temperature, Humidity, Noise Level, and AQI columns show the most significant color changes, again confirming the dominant position of these four features. Particularly noteworthy is that the AQI column is almost entirely red, indicating that across all analyzed samples, air quality tends to increase patient discomfort, providing strong evidence support for confirming key areas of medical environment management.

Discussion

This study achieved important findings in the field of medical environment comfort prediction through systematic experiments and in-depth interpretability analysis. The excellent performance of the XGBoost model across all evaluation metrics validates the advantages of ensemble learning methods in handling complex medical environment data18,19. This result is consistent with findings by Ahmed et al. in diabetes prediction research, further proving the stability and reliability of XGBoost in medical prediction tasks20,21. The model’s achieved accuracy of 85.2% and ROC-AUC value of 0.889 indicate its good potential for clinical applications.

The feature selection and optimization strategies employed in this study demonstrate significant improvements over traditional approaches. Recent advances in metaheuristic optimization algorithms, particularly hybrid methods combining multiple optimization strategies, have shown remarkable success in medical data analysis51,52. The application of innovative feature selection methods based on optimization algorithms has proven effective in identifying the most relevant environmental parameters for patient comfort prediction53,54. These methodological advances align with our findings that sophisticated algorithmic approaches can substantially enhance prediction accuracy in healthcare applications55.

The four key environmental factors (air quality index, temperature, noise level, and humidity) revealed by interpretability analysis provide important scientific basis for medical environment management22,23. Air quality index as the most important predictive factor emphasizes the core position of indoor air purification in medical environments, which is highly consistent with findings in related research emphasizing the impact of air quality on patient health24,25. The nonlinear influence pattern of temperature provides quantitative guidance for medical institutions to formulate precise temperature control strategies, while the significant impacts of noise and humidity also validate the necessity of multi-dimensional environment control26,27.

The consistency analysis of SHAP and LIME interpretation methods validates the reliability and stability of research results28,29. SHAP’s global consistency characteristics based on Shapley values give it unique advantages in medical applications, providing more stable and credible feature importance rankings30,31. Meanwhile, LIME’s local interpretation capability provides possibilities for personalized environment control, which has important significance for achieving precise medical environment management32,33. The complementarity of the two methods provides flexible choices for interpretation needs in different application scenarios.

The integration of advanced machine learning techniques with real-time monitoring systems represents a significant advancement in healthcare technology. Recent developments in spatiotemporal data analysis and deep learning frameworks have demonstrated substantial potential for enhancing environmental monitoring capabilities56,57. The application of attention mechanisms and self-supervised learning approaches in healthcare environments shows promise for improving predictive accuracy and reducing computational overhead58,59. Furthermore, the implementation of adaptive optimization algorithms with information enhancement capabilities provides robust foundations for handling the complex, dynamic nature of medical environment data60,61.

Compared with traditional medical environment management methods, the machine learning framework proposed in this study has significant advantages34,35. First, multi-sensor data fusion can comprehensively capture complex changes in environmental states, avoiding limitations of single indicator evaluation. Second, real-time prediction capability makes environmental control more timely and precise, helping to prevent occurrence of patient discomfort. Finally, interpretability analysis not only improves model credibility but also provides scientific support for formulating medical environment standards36,37.

Ethical and deployment considerations

Algorithmic transparency and trust

The deployment of machine learning models in healthcare environments raises important considerations regarding algorithmic transparency. This study addresses these concerns through the implementation of SHAP and LIME interpretability methods, which provide clinically interpretable explanations for model predictions. Healthcare professionals must understand not only what the model predicts but also why specific predictions are made. The ethical implications of automated decision-making in medical environments require careful consideration of patient autonomy, informed consent, and the potential for algorithmic bias to affect vulnerable populations.

Risk management framework

Real-time deployment of environmental comfort prediction systems requires robust risk management protocols: (1) False Positive Management: Excessive environmental adjustments based on false alarms could lead to unnecessary energy consumption and potential patient discomfort; (2) False Negative Mitigation: Failure to detect genuine patient discomfort could compromise patient care quality and recovery outcomes; (3) System Failure Protocols: Backup environmental monitoring systems must be maintained to ensure continuous patient care during model system failures. Additionally, regular model retraining and validation protocols must be established to maintain prediction accuracy as environmental conditions and patient populations evolve over time.

Computational performance analysis

The computational efficiency of the XGBoost model was evaluated for real-time deployment: Average prediction time: 2.3 milliseconds per sample; Memory footprint: 45 MB for trained model; CPU utilization:<5% on standard hospital computing infrastructure; Energy consumption: Negligible impact on facility energy budget. These performance metrics demonstrate the feasibility of real-time implementation in resource-constrained healthcare environments, while maintaining the necessary computational efficiency for continuous monitoring applications.

Scalability considerations

The proposed system demonstrates good scalability characteristics: Linear computational complexity with respect to patient number; Modular design allowing facility-specific customization; Cloud deployment compatibility for multi-facility implementations. The scalability framework supports both horizontal scaling across multiple facilities and vertical scaling within individual institutions, enabling flexible deployment strategies based on organizational needs and technical infrastructure capabilities.

Limitations and future directions

Study limitations

This research acknowledges several important limitations that must be addressed in future investigations:

Data limitations: The temporal scope of data collection, spanning only six months, may not adequately capture seasonal variations in environmental comfort requirements, particularly in regions with extreme climate fluctuations. Geographic constraints limit generalizability, as data from a single climatic region may not represent diverse geographical settings. While 1,000 samples provide adequate statistical power for current analyses, larger datasets could enable more sophisticated modeling approaches, including deep learning architectures that require substantial training data38,39.

Methodological limitations: The binary classification design may oversimplify the complexity of comfort gradients, as patient discomfort exists on a continuous spectrum rather than discrete categories. Static environmental thresholds fail to capture individual patient variations in comfort preferences, which can be influenced by factors such as age, cultural background, and personal health conditions. The absence of patient demographic integration (age, gender, health status) limits the model’s capacity for personalized prediction, potentially reducing effectiveness across diverse patient populations40,41.

Technical limitations: Real-time deployment challenges arise from the difference between controlled laboratory conditions and operational healthcare environments, where numerous unpredictable factors may influence system performance. Integration complexity with existing hospital information systems presents practical barriers to widespread adoption, requiring substantial technical infrastructure modifications42,43.

Future research directions

Enhanced data collection: Future research should prioritize multi-center, longitudinal data collection incorporating diverse patient populations, seasonal variations, and different facility types. Integration of patient feedback mechanisms through mobile applications or bedside interfaces would enable real-time validation of predicted comfort levels against actual patient experiences, creating a continuous learning feedback loop. Collaboration with international healthcare institutions could provide cross-cultural validation of environmental comfort preferences.

Advanced modeling approaches: Investigation of deep learning architectures, particularly recurrent neural networks and transformer models for temporal pattern analysis, could capture more complex environmental dynamics and patient adaptation behaviors46,47. Multi-output regression models incorporating continuous comfort scoring systems would provide more nuanced predictions than binary classifications, enabling graduated environmental control strategies. The exploration of federated learning approaches could enable model training across multiple institutions while preserving patient privacy.

Real-world validation: Prospective clinical trials in operational healthcare settings are essential for validating model performance under real-world conditions. Cost-effectiveness analyses comparing traditional environmental management approaches with AI-guided systems would demonstrate economic value and support business cases for implementation. Long-term patient outcome studies could establish causal relationships between optimized environmental conditions and improved recovery rates.

Personalization framework: Development of patient-specific comfort models incorporating individual characteristics, medical conditions, and personal preferences would enhance prediction accuracy and clinical utility. Integration with electronic health records could enable dynamic model adaptation based on patient medical history, current treatment protocols, and physiological monitoring data. Research into adaptive learning algorithms that continuously refine predictions based on individual patient responses would represent a significant advancement in personalized healthcare technology48–50.

Conclusion

This study successfully constructed a machine learning-based medical environment comfort prediction model, determining XGBoost as the optimal algorithm through comparative analysis, achieving 85.2% accuracy and 0.889 ROC-AUC value on the test set. Using SHAP and LIME interpretability methods, four key environmental factors affecting patient comfort were identified: air quality index, temperature, noise level, and humidity. Research results indicate that machine learning methods based on multi-sensor environmental monitoring can effectively predict patient discomfort, providing scientific basis for intelligent management of medical environments. Interpretability analysis not only improves model credibility but also provides guidance for medical institutions to formulate precise environmental control strategies.

The innovations of this study include: first application of multi-dimensional environmental monitoring data combined with machine learning methods for medical environment comfort prediction; revelation of specific influence mechanisms of environmental factors on patient comfort through explainable AI technology; establishment of a complete technical framework from data collection, model training to result interpretation. Research outcomes have important practical significance for improving medical service quality and patient experience, while providing scientific support for smart hospital construction and medical environment standard formulation.