Abstract

Uncontrolled abnormal cell growth, referred to as cancer, can result in tumors, other fatal disabilities, and immune system deterioration. Typically, the treatment procedure is longer and extremely expensive owing to its higher recurrence and death rates. Early and precise detection and assessment of cancer are significant for improving patient survival rates. Moreover, initial cancer detection makes the treatment simpler and improves the rate of recovery, leading to a lower mortality rate. Gene expression data plays an important part in cancer classification at the initial phase. Precise cancer classification is a challenging and complex task because of the high-dimensional nature of gene expression data, coupled with the small sample size. With the help of artificial intelligence (AI), researchers have recently developed fundamental models utilizing AI methods to diagnose and predict cancer. These techniques now play a leading role in increasing the precision of survival predictions, cancer susceptibility, and recurrence. This paper presents an Artificial Intelligence-Based Multimodal Approach for Cancer Genomics Diagnosis Using Optimized Significant Feature Selection Technique (AIMACGD-SFST) model. The aim is to develop precise and effective techniques for cancer genomics analysis using advanced computational and analytical techniques. The preprocessing stage comprises min-max normalization, handling missing values, encoding target labels, and splitting the dataset into training and testing sets. Furthermore, the AIMACGD-SFST model employs the coati optimization algorithm (COA) method for feature selection process to choose the related features from the dataset. Finally, the ensemble models, namely deep belief network (DBN), temporal convolutional network (TCN), and variational stacked autoencoder (VSAE) are employed for the classification process. The experimental validation of the AIMACGD-SFST approach is performed under three diverse datasets. The comparison study of the AIMACGD-SFST approach illustrated superior accuracy value of 97.06%, 99.07%, and 98.55% over existing models under diverse datasets.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Multimodal approaches, Cancer genomics diagnosis, Significant feature selection, Ensemble models

Subject terms: Computational science, Electrical and electronic engineering

Introduction

As per the world health organization (WHO), cancer is among the deadliest disorders globally. Cancer causes the uncontrolled development of certain abnormal cells that split and spread other cells, giving rise to harmful descendant cells1. Colorectal, stomach, prostate, and lung tumors are the prevalent forms of cancer found in men. Moreover, breast, lung, cervical, and colorectal tumors are prevalent in females. Brain tumors and acute lymphoblastic leukemia are more frequent types that occur in children2. Cancer prevalently affects the quality of life and societal productivity of the patients and it is crucial to detect it early for mitigating mortality rates and enhancing patient outcomes, ultimately preserving workforce efficiency during critical working years. The manual diagnosis method can cause mistakes because of inadequate resources3. Cancer is hard to identify in the initial phases, or can effortlessly relapse after treatment. Additionally, disease diagnosis with precise estimations is challenging. Certain tumors are hard to recognize in their initial stages because of their unclear signs and the indistinct indicators on scans and mammograms4. Therefore, emerging enhanced predictive techniques utilizing multi-variate data and high-resolution diagnostic tools in medical cancer research are vital. Most cells contain a nucleus that comprises deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). DNA carries hereditary data for the organs to multiply, grow, and function5. Proteins carry out key tasks in all organs, and they are created in double steps. Genetic technologies like DNA microarrays assess the concurrent gene activity, providing us with an overall cell view, which aids in distinguishing between healthy and unhealthy conditions6.

Cancer is defined as a set of illnesses connected with uncontrolled cell growth that attacks and spreads to surrounding tissues. DNA microarray-based gene activity description is a capable method to detect cancer in the initial stage. Timely cancer recognition increases the possibility of survival, decreasing personal, economic, and social expenses7. A rapid literature search shows that numerous cancer analysis studies have evolved enormously, particularly those comprising AI models and big datasets comprising historical medical cases to train AI systems8. Furthermore, the literature states that conventional analysis techniques, namely multivariate and statistical analysis, are not as precise as AI. This is very true when AI is employed along with advanced bioinformatics devices that can substantially advance the predictive, prognostic, and diagnostic precision. Recently, AI, especially machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), has become embedded in medical cancer studies, and prediction efficiency in this domain has achieved a new level9. AI is to support cancer prognosis and diagnosis, showing its extraordinary precision level, which is even advanced than that of common statistical applications in oncology. A more particular model, like DL, is gaining popularity10. DL is a subfield of AI and is utilized to build predictive paradigms, which interpret logical patterns from massive historical data to forecast a patient’s survival rate. DL is leveraged widely to improve prediction.

This paper presents an Artificial Intelligence-Based Multimodal Approach for Cancer Genomics Diagnosis Using Optimized Significant Feature Selection Technique (AIMACGD-SFST) model. The aim is to develop precise and effective techniques for cancer genomics analysis using advanced computational and analytical techniques. The preprocessing stage comprises min-max normalization, handling missing values, encoding target labels, and splitting the dataset into training and testing sets. Furthermore, the AIMACGD-SFST model employs the coati optimization algorithm (COA) method for feature selection process to choose the related features from the dataset. Finally, the ensemble models, namely deep belief network (DBN), temporal convolutional network (TCN), and variational stacked autoencoder (VSAE) are employed for the classification process. The experimental validation of the AIMACGD-SFST approach is performed under three diverse datasets. The main contributions of the AIMACGD-SFST approach are summarized below:

The AIMACGD-SFST model utilizes min-max normalization, missing value handling, label encoding, and dataset splitting to ensure clean, consistent inputs. This improves training stability, reduces noise, and assists reliable learning. It significantly improves model robustness and reproducibility across classification tasks.

The AIMACGD-SFST approach employs the COA technique for effectual feature selection, effectively mitigating dimensionality while preserving critical data. This improves learning efficiency, speeds up model training, and reduces overfitting. It also improves overall model generalization and performance on complex classification tasks.

The AIMACGD-SFST methodology implements an ensemble technique to harness the complementary merits of each model, resulting in an improved classification accuracy. This incorporation enables robust feature learning, enhanced temporal pattern recognition, and efficient representation of complex data. It ensures better generalization and stability across varied input conditions.

The AIMACGD-SFST method presents a novel classification framework for high-dimensional data by integrating COA-based feature selection with the hybrid DBN–TCN–VSAE ensemble model. This technique also integrates deep probabilistic modeling, temporal dynamics, and variational encoding for enhanced accuracy and generalization. Unlike existing single-model approaches, it improves robustness through structural diversity.

Literature review on cancer diagnosis

Bouazza11 presented Deep Ensemble Gene Selection and Attention-Guided Classification (DEGS-AGC), a new combined model for gene classification and selection. This model is aimed at addressing those restrictions by two basic elements: DEGS that uses ensemble learning with deep neural networks (DNN), XGBoost, and random forest (RF), for selecting significant genes though decreasing redundancy through attention-guided classification (AGC), and sparse autoencoders in which an attention mechanism (AM) adaptively allocates weights to genes to advance comprehensibility and classification accuracy. Li et al.12 introduced a GS technique for cancer identification through a multi-strategy-guided gravitational search algorithm (MSGGSA) method. This method efficiently addresses the restrictions connected with extreme unpredictability in people, early convergence vulnerability, and susceptibility to local optima faced through conventional GSA. In13, a multi-strategy fusion binary sea-horse optimization relies on a Gaussian transfer function (MBSHO-GTF) is introduced to resolve the FS issue of cancer gene activity data. Initially, the multi-strategy contains the hippo escape (HE) approach, the golden sine (GS) approach, and various inertia weight (IW) approaches. The SHO with the GS strategy doesn’t disturb the design of the novel technique. Xie et al.14 proposed a multi-modal learning framework for the diagnosis of GC and output projection, termed the GaCaMML technique, that is performed through a per-slide training method and a cross-modal AM system. Moreover, execute a feature attribution study through integrated gradient (IG) for identifying significant input features. This technique advances prediction performance in the single-modal learning paradigm. Particularly, the per-slide approach tackles the problem of a higher whole slide pathological images (WSI)-to-patient ratio and results in superior outcomes than the per-person training method. Sethi et al.15 developed a new Gene Expression Data Analysis by AI for Prostate Cancer Diagnoses (GEDAAI-PCD) model. This model inspects the GED to identify PRC. Afterward, the LSTM-DBN paradigm is deployed for PRC classification drives. Jahanyar et al.16 proposed a new approach named MS-ACGAN, in which the generator operates on a surrounded Gaussian distribution. In ML, standardization is of highest significance, which provides insights into model uncertainty and is viewed as a dynamic stage in refining the trustworthiness and strength of approaches. Hence, standardization methods for classifiers emphasize assessing their likelihoods as precisely as possible. Saheed et al.17 recommended an innovative ensemble of FS models through Fisher’s test (F-test) and the Wilcoxon signed rank sum test (WCSRS). Initially, data pre-processing is carried out; then, FS takes place through the F-test and WCSRS, and the p-values (probability value) of the F-test and WCSRS are implemented for cancer gene detection. In18, a different gene selection plan depending on the binary COOT (BCOOT) optimizer framework is introduced. The COOT framework is a recently introduced optimization that can resolve gene selection difficulties, which have yet to be discovered. 3 binary alternatives of the COOT framework are recommended for searching for genes to identify cancer and illnesses. Initially, a hyperbolic tangent transfer function is utilized to change the constant form of the COOT framework to binary. Moreover, a crossover operator (C) is employed to enhance the worldwide search of the BCOOT framework. Sahu et al.19 proposed an efficient model by incorporating Fast Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (FmRMR) feature selection with the binary portia spider optimization algorithm (BPSOA) technique chosen for tuning. Kiliçarslan and Dönmez20 presented a hybrid optimization model integrating adaptive PSO (APSO) and artificial bee colony (ABC) approaches for choosing optimal features from microarray gene expression data, followed by classification using support vector machine (SVM), artificial neural network (ANN), and k-nearest neighbor (kNN) across eight cancer datasets.

Sahu et al.21 presented a novel hybrid feature selection method namely enhanced prairie-dog optimization with firefly algorithm (E-PDOFA) methodology to improve optimal feature subset selection for cancer classification. Shallangwa, Ahmad, and Isuwa22 proposed a model by integrating logistic chaos-based initialization into three swarm intelligence (SI) algorithms namely PSO, Salp swarm algorithm (SSA), and firefly algorithm (FA), with the logistic-chaos FA (LCFA) achieving the highest accuracy. Sahu et al.23 introduced a hybrid feature selection model, relief with binary learning cooking algorithm (R-BLCA) technique to identify optimal features from high-dimensional cancer datasets. Jeba and Deepalakshmi24 reviewed and compared recent feature selection techniques utilized for analyzing high-dimensional gene expression data from microarrays. Adhikari et al.25 introduced a hybrid ensemble feature selection model integrating multiple filter and wrapper techniques with particle swarm optimization (PSO) and a majority voting classifier (VC) composed of logistic regression (LR), RF, and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) techniques to improve microarray-based cancer classification. Tabassum et al.26 developed a gene expression-based cancer classification process by using differential gene expression analysis with explainable AI (XAI) techniques. Gulande and Awale27 developed a hybrid feature selection framework by incorporating minimum redundancy maximum relevance (mRMR) and recursive feature selection algorithm (RSA) method for lung cancer (LC) classification using microarray gene expression data, where kNN outperformed other models like SVM and ANN. Yaqoob et al.28 proposed an effective feature selection framework that integrates random drift optimization (RDO) with XGBoost to improve cancer classification accuracy and detect biologically relevant genes across diverse cancer types. Nivetha et al.29 introduced a hybrid explainable ML model. The technique comprises Stability-Guided Multi-Source (SGMS)-based feature selection, Novel ElasticNet LR (NEN-LR), RF, and SVM techniques for improving cancer prediction and biomarker identification from gene expression data. Yaqoob, Verma, and Aziz30 improved gene selection and classification accuracy by integrating Sine Cosine and Cuckoo Search Algorithm (SCACSA) with SVM model for effective feature selection and classification. Shukla et al.31 presented a novel Polyvariant kernel for SVM that incorporates Vision Transformer (ViT) features from WSI with gene expression data for improving BC subtype classification. Yaqoob et al.32 improved gene selection and classification in high-dimensional cancer datasets by utilizing a hybrid Harris hawks optimization and cuckoo search algorithm (HHOCSA) technique integrated with kNN, SVM, and naïve bayes (NB) classifiers. Jyothi et al.33 proposed a ML-based framework that utilizes various approaches and feature selection techniques for enhanced accuracy and reliability. Yaqoob et al.34 developed a hybrid Harris Hawk Optimization and Whale Optimization (HHO-WO) approach integrated with a DL model by utilizing RNA-Seq gene expression data. Nargis, Movania, and Siddiqui35 developed a hybrid DL model namely Autoencoder-Integrated Wide Residual Network with Dynamic Optimization (AIW-DynOpt) for accurate and efficient gene expression analysis in head and neck cancer. Yaqoob, Verma, and Aziz36 presented an effective model for BC detection by employing minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance with Salp Swarm Optimization and Weighted SVM (mRMR-SSO-WSVM) methodology to improve accuracy. Motevalli, Khalilian, and Bastanfard37 introduced an efficient gene selection method by combining Fuzzy Entropy and Giza Pyramid Construction (GPC) for dimensionality reduction, followed by cancer classification using convolutional neural network (CNN). Yaqoob38 developed an efficient approach by integrating Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance with the Northern Goshawk Algorithm and SVM (mRMR-NGHA-SVM) technique.

Naccour et al.39 improved lymph node classification in head and neck cancer by integrating CT-based radiomics with ML model for accurate, non-invasive detection of malignancy. Yaqoob et al.40 proposed a Two-stage Mutual Information and PSO SVM (MI-PSO-SVM) method, which selects highly informative gene subsets from high-dimensional datasets for accurate and robust classification. Shukla et al.41 proposed a hybrid feature selection model named Sequential Quantum Teaching Learning-Based Optimization with Genetic Algorithm (SeQTLBOGA) approach for optimizing SVM parameters and gene subsets to enhance BC classification accuracy. Yaqoob, Bhat, and Khan42 evaluated and compared key dimensionality reduction methods such as linear discriminant analysis (LDA), principal component analysis (PCA), and t-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding (t-SNE) techniques for improving cancer classification by utilizing gene expression data. Li and Cheng43 developed DL and radiomics-based models, comprising ViT, Swin transformer (ST), and ConvNeXtBase techniques for non-invasive classification of BC subtypes. Yaqoob et al.44 developed an effective BC classification model by incorporating seagull optimization algorithm (SOA) technique for gene selection with RF classifier. Palmal et al.45 developed a novel multimodal predictive model called Multimodal Graph Convolutional Networks with Calibrated Random Forest (MGCN-CalRF) technique by integrating mRNA sequencing, DNA methylation, copy number variation, microRNA sequencing, clinical data, and whole slide imaging to improve survival prediction accuracy. Uma Kandan, Alketbi, and Al Aghbari46 developed a multi-input CNN model for accurate BC prognosis prediction by utilizing multi-modal data. Yaqoob and Verma47 presented an efficient BC classification model by incorporating kashmiri apple optimization (KAO) and armadillo optimization algorithm (AOA) approaches for gene selection with SVM to improve accuracy and mitigate redundancy in high-dimensional gene expression data. Zhao and Li48 proposed TreeEM, a tree-enhanced ensemble model that incorporates max-relevance and min-redundancy feature selection with extreme RF and Fusion Undersampling RF techniques. Wang, Zhang, and Wang49 aimed to improve ML techniques for cancer diagnosis by handling tumor heterogeneity and high-dimensional data, and to discuss the potential of AI and DL methods. Nagra et al.50 developed a self-inertia weight adaptive PSO incorporated with extreme learning machine (ELM) for effective gene selection and cancer classification using microarray data. Agustriawan et al.51 developed a race-specific prostate cancer diagnosis methodology by utilizing gene expression data and SVM methods with enhanced feature selection. Das et al.52 introduced a DL model by utilizing Enhanced Chimp Optimization (ECO) for gene selection and Depth-wise Separable Convolutional Neural Network (DSCNN) technique for accurate cancer classification from gene expression data. Lawrence, Jimoh, and Yahya53 proposed an efficient cancer classification method by integrating Genetic Algorithms (GAs) for feature selection and DBN for classifying high-dimensional microarray data. Sucharita et al.54 developed a two-step hybrid feature selection method by harnessing moth-flame optimization (MFO) and ELM methods for improved cancer classification using microarray gene expression data. Dhamercherla, Reddy Edla, and Dara55 presented an Eagle Prey Optimization (EPO) technique for effective gene selection in microarray cancer classification. Tabassum et al.56 proposed a cancer classification model using Mutual Information (MI) for gene selection and Bagging with multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) for improving classification accuracy. Alkamli and Alshamlan57 compared hybrid bio-inspired algorithms and DL methods for efficient gene selection and accurate cancer classification using gene expression data. Senbagamalar and Logeswari58 introduced a multiclass cancer classification model using Genetic Clustering Algorithm (GCA) model for feature selection and Divergent Random Forest (DRF) technique for accurate classification of five cancer types from gene expression data.

While various advanced gene selection and classification methods such as DEGS-AGC, MSGGSA, and hybrid swarm intelligence algorithms illustrated promising results, they mostly encounter threats comprising high computational complexity, susceptibility to local optima, and limited interpretability. Several methods face difficulty with scalability when applied to large, high-dimensional datasets, affecting real-time clinical applicability. Moreover, some models lack robust mechanisms for mitigating redundancy effectively or adaptively allocate feature importance, which can affect classification performance. Many approaches encounter limitations such as reliance on single datasets, limited generalizability across diverse populations, and high computational costs with complex models. There is also a research gap in integrating efficient optimization strategies with explainability techniques to improve both predictive accuracy and biological insight. Furthermore, most existing methods do not adequately address imbalanced data or heterogeneity across cancer types, restricting generalizability. Addressing these gaps can result in more robust, scalable, and interpretable cancer classification models. Also, few studies thoroughly address real-time applicability, robustness to noisy data, and integration of multi-omics data, highlighting gaps for future research.

Materials and methods

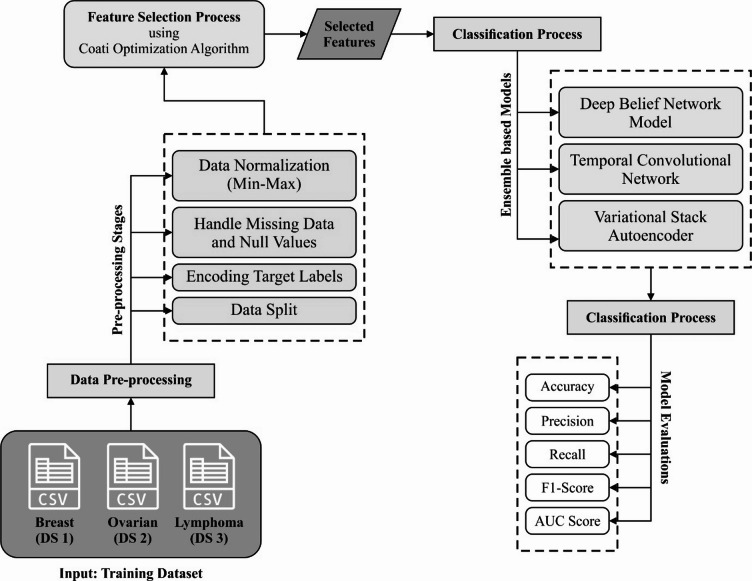

In this paper, the AIMACGD-SFST model is presented. The main intention of the AIMACGD-SFST model is to develop correct and effective techniques for cancer genomics analysis using advanced computational and analytical techniques. To perform that, the AIMACGD-SFST model has data collection, data preparation, feature reduction using COA, and ensemble learning models. Figure 1 represents the workflow of the AIMACGD-SFST technique.

Fig. 1.

Workflow of AIMACGD-SFST model.

Data collection

The performance evaluation of the AIMACGD-SFST model is examined under Brest (DS 1), Ovarian (DS 2), and Lymphoma (DS 3) datasets59. The DS 1 has 97 samples under dual classes, DS 2 has 253 samples under dual classes, and DS 3 samples under three classes. The DS 1 has 24,481 features in total, but only 1024 features are selected. Whereas, the DS 2 contains 15,154 features completely, but 1011 features were chosen. While the DS 3 holds 4027 total features but only 1025 features are selected. The complete details of these databases are presented below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of datasets.

| Dataset | Total samples | Total-selected features | Classes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brest (DS 1) | 97 | 24,481−1024 |

Relapse(Cancer)/46, Non-Relapse(Non-Cancer)/51 |

| Ovarian (DS 2) | 253 | 15,154−1011 | Cancer/162, Normal/91 |

| Lymphoma (DS 3) | 66 | 4027−1025 | DLBCL (Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma)/46, FL (Follicular Lymphoma)/9, CLL (Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia)/11 |

Data preparation

Data pre-processing performs a major role in improving the generalizability and performance of cancer identification techniques. The raw datasets attained from bio-medical resources frequently comprise min-max based data normalization, handling missing data and null values, encoding target labels, and data split through features. To tackle these challenges, a series of pre-processing stages is applied before method evaluation and training.

Data normalization: Normalization is a general pre-processing methodology in ML that handles datasets of diverse scales60. It guarantees that each element is handled equally for clear comparison. To change data through numerical processes, it integrates various metrics into a reliable pattern. This procedure comprises modifying the maximal and minimal values for standardizing the range. The aim is to scale the lowest data value to zero and the highest to one, with all other values proportionally adjusted in [0, 1]. The numerical expression for this model is specified in Eq. (1)

|

1 |

Here,  means input data,

means input data,  indicates transformed data,

indicates transformed data,  and

and  refer to the minimal and maximal values for input data.

refer to the minimal and maximal values for input data.

Handle missing and null values: It is vital in cancer data pre-processing to safeguard the reliability and accuracy of predictive techniques61. Incomplete entries can arise from patient non-responses, recording errors, or equipment malfunctions. Numerical missing values are usually imputed employing the median or mean, based on feature distribution, although categorical data are filled with a distinct placeholder or mode. Records with redundant missing data are frequently extracted to preserve the integrity of the database.

Encoding target labels: Afterwards, encoding targeted labels using values from 0 to n-1 classes for every database, where  is the category count in the respective databases. For convenience in utilizing ML for removing data, definite variables are modified into mathematical form through label encodings.

is the category count in the respective databases. For convenience in utilizing ML for removing data, definite variables are modified into mathematical form through label encodings.

Data split: The pre-processed data is partitioned into dual portions with a 70% to 30% ratio for evaluating and training methods.

Feature reduction using COA

For a significant FS process, the AIMACGD-SFST model employs the COA method to select the most relevant features from the dataset62. This model is chosen for its robust capability in effectually balancing exploration and exploitation through its dual-phase behavior inspired by coatis’ foraging and evasion strategies. The technique also efficiently explores the search space while avoiding premature convergence, making it appropriate for high-dimensional gene expression data, unlike conventional approaches namely PSO, GA, or ACO, COA. It also effectually detects a compact, informative subset of features that preserves classification performance while reducing computational complexity. Its iterative update mechanism ensures robust convergence, and empirical comparisons demonstrate that COA achieves higher accuracy with fewer features than competing methods.

FS aims to recognize the most important aspects of the unique vector features. It selects the minimum vital feature set to enhance the precision of classification. The COA is utilized for detecting the most appropriate subset of features from the removed statistical and texture features. These animals are similar to those of huge domestic cats. Being omnivorous, coatis consume several preys, comprising smaller mammals, insects, alligator eggs, reptiles, and birds. They employ an integration of tactics for searching green iguanas. The COA imitates the intellectual escape and searching models of coatis, reflecting their intellectual behaviour.

Within the COA Initializing stage, every coati is chosen to depict a member of the population. The location of every coati in the searching area is compared to the decision variable value that determines a solution. Primarily, the coati is arbitrarily allocated based on Eq. (2)

|

2 |

Here,  is the value of

is the value of  th decision variable,

th decision variable,  indicates location of

indicates location of  th coati,

th coati,  specifies the decision variable counts,

specifies the decision variable counts,  represents overall coatis counts,

represents overall coatis counts,  and

and  refers to upper and lower bounds of

refers to upper and lower bounds of  th decision variable,

th decision variable,  signifies an arbitrary number in interval [0,1], correspondingly.

signifies an arbitrary number in interval [0,1], correspondingly.

The population matrix, depicting the position of the coati is described in Eq. (3):

|

3 |

The values of the target objective for diverse solutions are depicted by the vector

|

4 |

.

Within the initial stage, COA employs the coatis’ approach of searching  . Coatis work together to increase trees to scare away

. Coatis work together to increase trees to scare away  , although others wait below to catch them. This strategy permits exploration, enabling coatis to hunt for prey across the world. After the coati finds an iguana, the behavior of the group modifies in waiting and climbing.

, although others wait below to catch them. This strategy permits exploration, enabling coatis to hunt for prey across the world. After the coati finds an iguana, the behavior of the group modifies in waiting and climbing.

|

5 |

The locations are upgraded depending on the arbitrary placement of the fallen iguana outlined in Eqs. (6 and 7).

|

6 |

|

|

7 |

If the novel location outcomes in an enhancement in the value of the target function, it will be recognized; alternatively, the coati will retain its preceding location.

|

8 |

Phase 2: Exploitation over Predator Evasion in another stage of their behaviour, COA techniques pretend the activities of coatis while trying to avoid predators. Coatis focus on positioning novel locations that are adjacent to their existing locations and searching for security in this way.

|

9 |

|

|

10 |

Based on Eq. (11), if the novel location outcomes in a greater value than the target location, it will be accepted; Then, the coati resides in its preceding location.

|

11 |

The COA model goes over an iterative procedure comprising the repositioning of every coati in the searching area in the primary and secondary runs. While the model is accomplished, the finest solution attained from every iteration is chosen as the final solution.

The comparison of COA with five recent optimization algorithms such as PSO, GA, grey wolf optimizer (GWO), whale optimization algorithm (WOA), and ant lion optimizer (ALO) demonstrates that COA outperforms others by attaining the highest classification accuracy of 91.0%, selecting the smallest feature subset of 27, and converging fastest within 35 epochs. This indicates the efficiency of the COA model in balancing accuracy, feature reduction, and computational efficiency, making it a robust choice for feature selection. Table 2 depicts the comparison of COA model with recent feature selection algorithms.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of COA model with recent feature selection algorithms across accuracy, feature subset size, and convergence speed.

| Method | Accuracy (%) | Feature subset size | Convergence speed (epochs) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSO | 87.5 | 32 | 45 | Good accuracy but larger subset |

| GA | 86.8 | 35 | 50 | Converge slowly |

| GWO | 88.1 | 30 | 40 | Depicts balanced performance |

| WOA | 86.5 | 33 | 48 | Moderate in accuracy |

| ALO | 87.0 | 31 | 47 | Similar to PSO |

| COA | 91.0 | 27 | 35 | Illustrates fast convergence with small feature set and high accuracy |

The fitness function (FF) applied in the presented model is intended to have a balance between the selected feature counts in all solutions (least) and the classification accuracy (greatest) gained by utilising these chosen attributes. Equation (12) characterizes the FF to appraise solutions.

|

12 |

Now,  characterizes the classification error rate of a provided classifier.

characterizes the classification error rate of a provided classifier.  refers to the selected subset cardinality, and

refers to the selected subset cardinality, and  denotes while number of features in the database,

denotes while number of features in the database,  and

and  are dual parameters according to the significance of classification quality and subset length. Algorithm 1 specifies the COA technique.

are dual parameters according to the significance of classification quality and subset length. Algorithm 1 specifies the COA technique.

Algorithm 1: COA model.

Ensemble learning approaches

Finally, the ensemble models, namely DBN, TCN, and VSAE, is employed for the classification process. The ensemble models are chosen for its complementary strengths of deep probabilistic reasoning, temporal pattern extraction, and hierarchical feature learning. The TCN method effectually handles sequential dependencies with parallelization benefits, while the DBN technique captures high-level abstractions. Moreover, the VSAE model improves generalization through variational inference. This integration addresses the limitations of using a single classifier by enhancing robustness and reducing overfitting. Compared to standalone models, the ensemble attains superior classification performance across diverse data patterns and demonstrates improved adaptability to complex datasets.

DBN classifier

DBN is a probability-based generative technique that is a multi-layer perceptual stacked network using restricted boltzmann machine (RBM) that focuses on a layer-by-layer model of greedy learning63. The training of DBN is separated into dual stages: primarily, an unsupervised pretraining stage, followed by the supervised reverse modification stage. The RBM is partitioned into a hidden layer (HL) and a visible layer (VL); it contains omnidirectional connections among the nodes in HL and VL, and the nodes inside layers are disconnected. In training nodes, the VL is attained aspects from the database and passing them to HL. Subsequently, the nodes inside the HL are multiplied by the weighting to attain the bias and then added. The output is processed by the function of activation function and passed to subsequent HL. This hierarchical learning methodology not only enhances the learning efficacy of DBN, likewise improves the extraction of multifeature ability of the methodology. Figure 2 signifies the structure of DBN.

Fig. 2.

DBN structure.

During the pretraining stage, the probability distribution function  is given in Eq. (13).

is given in Eq. (13).

|

13 |

Now  represents the normalization constant, and

represents the normalization constant, and  indicate the energy function.

indicate the energy function.

The energy function  of the HL and VL nodes

of the HL and VL nodes

|

14 |

.

Now,  represents the deviation of HL,

represents the deviation of HL,  indicates the deviation of VL,

indicates the deviation of VL,  depicts the node of HL,

depicts the node of HL,  refers to the connection weight between the VL and HL, and

refers to the connection weight between the VL and HL, and  specifies the node of VL.

specifies the node of VL.

The normalization constant  denotes the amount of energy of every node among VL and HL.

denotes the amount of energy of every node among VL and HL.

|

15 |

Within the procedure of unsupervised learning, the function of  -likelihood is basic to the method and imitates the learning capability of methodologies.

-likelihood is basic to the method and imitates the learning capability of methodologies.

|

16 |

Now,  indicates the addition of every training data. Through the RBM training procedure, the CD approach is employed for upgrading the weights

indicates the addition of every training data. Through the RBM training procedure, the CD approach is employed for upgrading the weights  and deviations

and deviations  of VL and HL.

of VL and HL.

|

17 |

|

18 |

|

19 |

Here,  is the value of actual data,

is the value of actual data,  represents the value of predicted data, and

represents the value of predicted data, and  refers to the rate of learning. Once the pre-training procedure is over, the reverse modifications begin. During this procedure, the model is upgraded cyclically depending on the weights

refers to the rate of learning. Once the pre-training procedure is over, the reverse modifications begin. During this procedure, the model is upgraded cyclically depending on the weights  . The node bias

. The node bias  of HL, and the loss function

of HL, and the loss function  .

.

|

20 |

|

21 |

TCN model

TCN is one of the CNN devoted to processing time series64. Its major framework comprises various residual blocks, and every residual block includes a causal and dilated convolution. Causal convolution could safeguard that the output only relies on preceding input data, which effectually precludes the leakage of upcoming data. The dilated convolution increases the receptive area of the convolution layer without increasing extra parameters over the interval sampling mechanism, therefore efficiently resolves the issue of eliminating multi-variate time-series aspects. This model permits the top-level output for combining a broad array of historic input data, substantially improving the capability of the approach, while precluding efficacy loss owing to the depth of the network. Furthermore, the time convolution system accepts a 1D full convolution framework and precisely preserves the temporal length consistency among every input layer and HL over a zero‐filling operation (ZP), guaranteeing that the methodology can handle data sequences end-to-end, presenting an architectural foundation for multiscale extraction of the features. Figure 3 represents the infrastructure of the TCN model.

Fig. 3.

Architecture of TCN.

Let the input time-series  is specified and the equivalent output

is specified and the equivalent output  is expected, subsequently, under the filter action

is expected, subsequently, under the filter action  ,

,

|

22 |

represents factor of expansion,

represents factor of expansion,  is output of convolution operation,

is output of convolution operation,  indicates filter size,

indicates filter size,  signifies element

signifies element  of input sequence, and

of input sequence, and  depicts weight of convolution kernel. As the depth of network n rises, the number of data points attained while gathering data from subsequent layer of network range

depicts weight of convolution kernel. As the depth of network n rises, the number of data points attained while gathering data from subsequent layer of network range  points of the data reduce by

points of the data reduce by  that allows filtering for acquiring the features of sequence with a broader area, while filtering out information. To secure effective learning and data transmission, the concern of gradient vanishing in deeper training network is evaded.

that allows filtering for acquiring the features of sequence with a broader area, while filtering out information. To secure effective learning and data transmission, the concern of gradient vanishing in deeper training network is evaded.

|

23 |

depicts residual function, and

depicts residual function, and  indicates activation function.

indicates activation function.

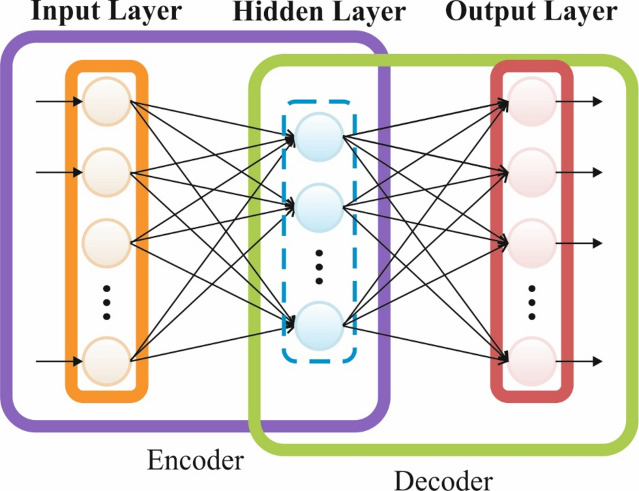

VSAE algorithm

Variational autoencoder (VAE) is extensively used since it was first proposed in65. VAE is used to generate  by samples from the hidden parameter distribution

by samples from the hidden parameter distribution  . The prior probability

. The prior probability  of hidden parameter

of hidden parameter  , representing the new distribution of

, representing the new distribution of  ; the distribution of dataset

; the distribution of dataset  is

is  should be produced, and

should be produced, and  indicates the posterior distribution of

indicates the posterior distribution of  which is otherwise known as encoded. For such reasons,

which is otherwise known as encoded. For such reasons,  is intractable to resolve in real-time, the

is intractable to resolve in real-time, the  The variational approximation is frequently used to replace it. Figure 4 implies the structure of VSAE.

The variational approximation is frequently used to replace it. Figure 4 implies the structure of VSAE.

Fig. 4.

Structure of VSAE model.

In VAE,  represents the Gaussian distribution, and

represents the Gaussian distribution, and  divergence between

divergence between  and

and  is delineated as demonstrated:

is delineated as demonstrated:

|

24 |

Based on the Bayes’ rule, it is formulated by

|

25 |

.

Meanwhile, the  divergence is non-negative, and the equation is represented as

divergence is non-negative, and the equation is represented as

|

26 |

|

27 |

|

.

In the equations,  indicates the variational lower boundary of

indicates the variational lower boundary of  That is furthermore function of loss of VAE. The regularization is the initial term. The reconstruction error is the second term.

That is furthermore function of loss of VAE. The regularization is the initial term. The reconstruction error is the second term.

Consider

, the 1st term on R.H.S of Eq. (27) is computed by

, the 1st term on R.H.S of Eq. (27) is computed by

|

28 |

.

In Eq. (28), the distribution dimension is  .

.

The second term on R.H.S of Eq. (27) is evaluated as:

|

29 |

In Eq. (29),  is selected to be 1, and

is selected to be 1, and

|

30 |

.

Therefore, the VAE loss is attained using Eq. (27), and when the sampling model is used during the procedure of resolving the loss, then backpropagation is used in the neural network (NN).

Various AEs are stacked to construct an SAE network for achieving high-level feature extraction. In contrast,  , the SAE, has a sophisticated network model and optimum non-linear fitting capability that allows it to directly carry out feature extraction from the raw information. However, the SAE extracts feature through non-linear conversion, and it is complex for SAE to model the hidden feature space. By chance, these problems are resolved by presenting VAE. Especially, the

, the SAE, has a sophisticated network model and optimum non-linear fitting capability that allows it to directly carry out feature extraction from the raw information. However, the SAE extracts feature through non-linear conversion, and it is complex for SAE to model the hidden feature space. By chance, these problems are resolved by presenting VAE. Especially, the  and

and  of the Gaussian distribution are attained by using two encoders, later from the standard Gaussian distribution

of the Gaussian distribution are attained by using two encoders, later from the standard Gaussian distribution  , sampling is performed, and the hidden feature vector

, sampling is performed, and the hidden feature vector  is created by Eq. (30) that represents the reparameterization process. Lastly, once the decoders are formed by the FC layer, the feature is reconstructed into data that is equivalent to the input data.

is created by Eq. (30) that represents the reparameterization process. Lastly, once the decoders are formed by the FC layer, the feature is reconstructed into data that is equivalent to the input data.

Model performance analysis

The performance assessment of the AIMACGD-SFST approach is examined under three diverse datasets69. The model runs on Python 3.6.5 with an i5-8600k CPU, 4GB GPU, 16GB RAM, 250GB SSD, and 1 TB HDD, using a 0.01 learning rate, ReLU, 50 epochs, 0.5 dropout, and batch size 5.

Figure 5 institutes the confusion matrices generated by the AIMACGD-SFST model below 70:30 of TRPHE/TSPHE. In DS1, the AIMACGD-SFST model exhibits robust discrepancy between cancer and non-cancer cases, with minimal misclassifications in both phases, highlighting its efficiency. DS2 illustrates similar accuracy with slight errors, with the majority of cancer and normal samples correctly classified. DS3 depicts excellent performance in the training phase with perfect classification for certain classes, while the TRPHE maintains robust predictive capability despite the enhanced complexity. Overall, the results state that the AIMACGD-SFST technique efficiently detects and identifies all class labels.

Fig. 5.

Confusion matrices of AIMACGD-SFST technique (a–c) 70%TRPHE and (d–f) 30%TSPHE.

Table 3; Fig. 6 depict the cancer detection of AIMACGD-SFST model on DS 1, DS 2, and DS 3 datasets. Under DS 1, on 70% TRPHE, this AIMACGD-SFST model provides average  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  of 96.96%, 96.96%, 96.96%, 96.96%, and 96.96%, respectively. Moreover, on 30%TSPHE, the AIMACGD-SFST technique provides average

of 96.96%, 96.96%, 96.96%, 96.96%, and 96.96%, respectively. Moreover, on 30%TSPHE, the AIMACGD-SFST technique provides average  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  of 97.06%, 96.43%, 97.06%, 96.63%, and 97.06%, correspondingly.

of 97.06%, 96.43%, 97.06%, 96.63%, and 97.06%, correspondingly.

Table 3.

Cancer detection of AIMACGD-SFST model on DS 1, DS 2, and DS 3 datasets.

| Class labels |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brest (DS 1) | |||||

| TRPHE (70%) | |||||

| Cancer | 96.55 | 96.55 | 96.55 | 96.55 | 96.96 |

| Non-cancer | 97.37 | 97.37 | 97.37 | 97.37 | 96.96 |

| Average | 96.96 | 96.96 | 96.96 | 96.96 | 96.96 |

| TSPHE (30%) | |||||

| Cancer | 94.12 | 100.00 | 94.12 | 96.97 | 97.06 |

| Non-cancer | 100.00 | 92.86 | 100.00 | 96.30 | 97.06 |

| Average | 97.06 | 96.43 | 97.06 | 96.63 | 97.06 |

| Ovarian (DS 2) | |||||

| TRPHE (70%) | |||||

| Cancer | 96.30 | 97.20 | 96.30 | 96.74 | 95.97 |

| Normal | 95.65 | 94.29 | 95.65 | 94.96 | 95.97 |

| Average | 95.97 | 95.74 | 95.97 | 95.85 | 95.97 |

| TSPHE (30%) | |||||

| Cancer | 98.15 | 100.00 | 98.15 | 99.07 | 99.07 |

| Normal | 100.00 | 95.65 | 100.00 | 97.78 | 99.07 |

| Average | 99.07 | 97.83 | 99.07 | 98.42 | 99.07 |

| Lymphoma (DS 3) | |||||

| TRPHE (70%) | |||||

| DLBCL | 97.83 | 97.22 | 100.00 | 98.59 | 95.45 |

| FL | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| CLL | 97.83 | 100.00 | 85.71 | 92.31 | 92.86 |

| Average | 98.55 | 99.07 | 95.24 | 96.97 | 96.10 |

| TSPHE (30%) | |||||

| DLBCL | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| FL | 95.00 | 100.00 | 80.00 | 88.89 | 90.00 |

| CLL | 95.00 | 80.00 | 100.00 | 88.89 | 96.88 |

| Average | 96.67 | 93.33 | 93.33 | 92.59 | 95.62 |

Fig. 6.

Average values of AIMACGD-SFST model on DS 1, DS 2 and DS 3 datasets.

Under DS 2, on 70%TRPHE, the AIMACGD-SFST method provides an average  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  of 95.97%, 95.74%, 95.97%, 95.85%, and 95.97%, correspondingly. Similarly, on 30%TSPHE, the AIMACGD-SFST method provides an average

of 95.97%, 95.74%, 95.97%, 95.85%, and 95.97%, correspondingly. Similarly, on 30%TSPHE, the AIMACGD-SFST method provides an average  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  of 99.07%, 97.83%, 99.07%, 98.42%, and 99.07%, respectively. Under DS 3, on 70%TRPHE, the AIMACGD-SFST approach provides an average

of 99.07%, 97.83%, 99.07%, 98.42%, and 99.07%, respectively. Under DS 3, on 70%TRPHE, the AIMACGD-SFST approach provides an average  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  of 98.55%, 99.07%, 95.24%, 96.97%, and 96.10%, respectively. Likewise, on 30%TSPHE, the AIMACGD-SFST approach provides an average

of 98.55%, 99.07%, 95.24%, 96.97%, and 96.10%, respectively. Likewise, on 30%TSPHE, the AIMACGD-SFST approach provides an average  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  of 96.67%, 93.33%, 93.33%, 92.59%, and 95.62%, correspondingly.

of 96.67%, 93.33%, 93.33%, 92.59%, and 95.62%, correspondingly.

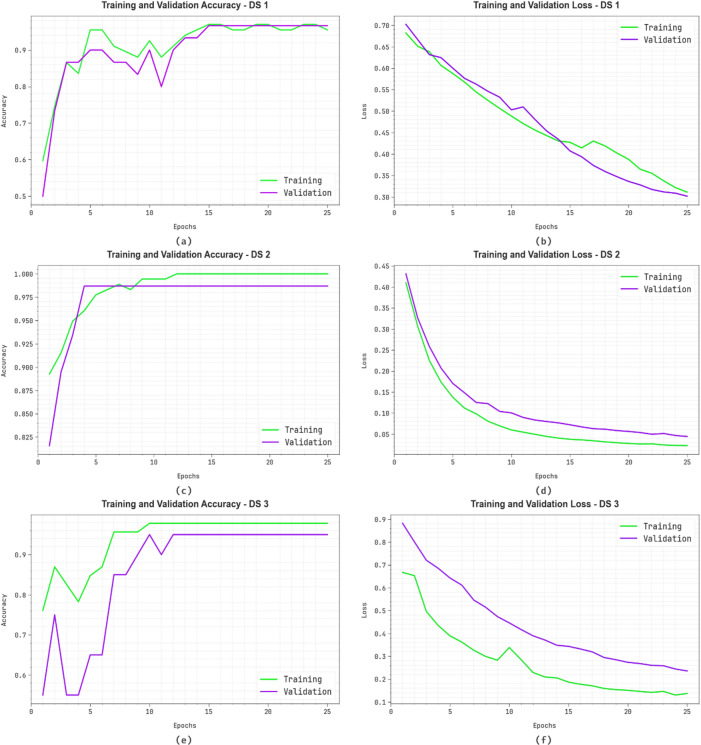

Figure 7 shows the classifier outcomes of AIMACGD-SFST model on DS 1, DS 2 and DS 3 database. Figure 7a,c, and 7e exhibit the accuracy investigation of the AIMACGD-SFST model. The figure reports that the AIMACGD-SFST method achieves progressively higher accuracy with increasing epochs. Moreover, the consistent improvement in validation relative to training displays that the AIMACGD-SFST method effectively learns on the test dataset. Lastly, Fig. 7b,d, and 7f exemplify the loss analysis of the AIMACGD-SFST technique. The outcomes specify that the AIMACGD-SFST technique achieves closely aligned training and validation loss values. It is noted that the AIMACGD-SFST technique learns effectively on the test dataset.

Fig. 7.

(a,c,e) Accuracy curves and (b,d,f) Loss curves on DS 1, DS 2 and DS 3.

Figure 8 establishes the classifier outcomes of AIMACGD-SFST model on DS 1, DS 2 and DS 3 datasets. Figure 8a,b, and 8c present the PR examination of the AIMACGD-SFST approach. The outcomes specified that the AIMACGD-SFST approach results in elevated PR values. Also, the AIMACGD-SFST approach can reach advanced PR values on every class. Figure 8d,e, and 8f demonstrate the ROC valuation of the AIMACGD-SFST approach. The figure defined that the AIMACGD-SFST approach resulted in better ROC values. Further, the AIMACGD-SFST approach can reach increased ROC values for each class.

Fig. 8.

(a–c) PR curves and (d–f) ROC curves on DS 1, DS 2 and DS 3.

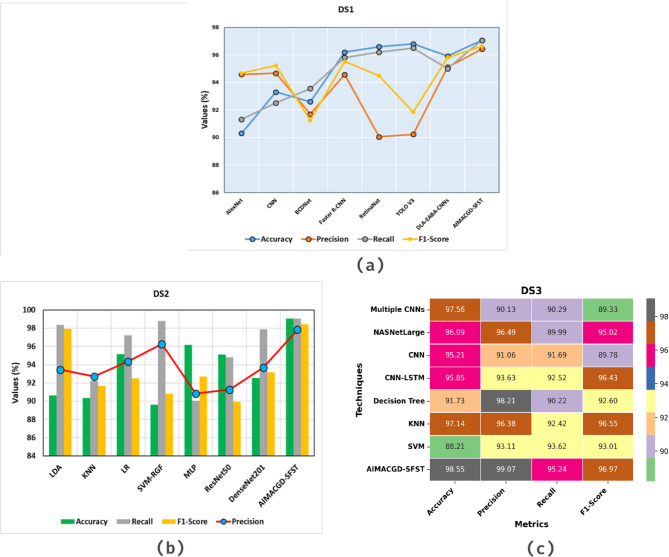

Table 4 represents the comparative analysis of AIMACGD-SFST model on DS 1, DS 2, and DS 3 datasets with existing models such as AlexNet, CNN, BCDNet, Faster Recurrent CNN (R-CNN), RetinaNet, You Look Only Once V3 (YOLO V3), DL-assisted Efficient Adaboost Algorithm CNN (DLA-EABA-CNN), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), SVM with Regularized Greedy Forest (SVM-RGF), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), ResNet50, DenseNet201, Multiple CNN, NASNetLarge, CNN-LSTM, and decision tree (DT) under various metrics66–68.

Table 4.

Comparative analysis of AIMACGD-SFST model on DS 1, DS 2, and DS 3 datasets.

| Dataset | Technique |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS 1 | AlexNet | 90.30 | 94.58 | 91.32 | 94.67 |

| CNN | 93.30 | 94.67 | 92.51 | 95.23 | |

| BCDNet | 92.60 | 91.70 | 93.56 | 91.25 | |

| Faster R-CNN | 96.20 | 94.57 | 95.80 | 95.53 | |

| RetinaNet | 96.60 | 90.05 | 96.20 | 94.49 | |

| YOLO V3 | 96.80 | 90.23 | 96.50 | 91.85 | |

| DLA-EABA-CNN | 95.91 | 95.11 | 95.00 | 95.81 | |

| AIMACGD-SFST | 97.06 | 96.43 | 97.06 | 96.63 | |

| DS 2 | LDA | 90.61 | 93.44 | 98.35 | 97.94 |

| KNN | 90.34 | 92.71 | 92.24 | 91.70 | |

| LR | 95.16 | 94.34 | 97.24 | 92.49 | |

| SVM-RGF | 89.61 | 96.25 | 98.79 | 90.82 | |

| MLP | 96.18 | 90.83 | 90.03 | 92.68 | |

| ResNet50 | 95.13 | 91.27 | 94.82 | 89.93 | |

| DenseNet201 | 92.52 | 93.69 | 97.90 | 93.16 | |

| AIMACGD-SFST | 99.07 | 97.83 | 99.07 | 98.42 | |

| DS 3 | Multiple CNNs | 97.56 | 90.13 | 90.29 | 89.33 |

| NASNetLarge | 96.09 | 96.49 | 89.99 | 95.02 | |

| CNN | 95.21 | 91.06 | 91.69 | 89.78 | |

| CNN-LSTM | 95.85 | 93.63 | 92.52 | 96.43 | |

| DT | 91.73 | 98.21 | 90.22 | 92.60 | |

| KNN | 97.14 | 96.38 | 92.42 | 96.55 | |

| SVM | 88.21 | 93.11 | 93.62 | 93.01 | |

| AIMACGD-SFST | 98.55 | 99.07 | 95.24 | 96.97 |

Figure 9a portrays the comparative exploration of AIMACGD-SFST approach with current models on DS 1 dataset. The result described that the AlexNet, CNN, BCDNet, Faster R-CNN, RetinaNet, YOLO V3, and DLA-EABA-CNNs methodologies achieved lowest values. Whereas, the AIMACGD-SFST model attained greater performance with  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  97.06%, 96.43%, 97.06%, and 96.63%, respectively.

97.06%, 96.43%, 97.06%, and 96.63%, respectively.

Fig. 9.

Comparative analysis of AIMACGD-SFST model (a) DS 1, (b) DS 2, and (c) DS 3 datasets.

Figure 9b illustrates the comparative study of AIMACGD-SFST technique with present approaches on DS 2 dataset. The result conveyed that the LDA, KNN, LR, SVM-RGF, MLP, ResNet50, and DenseNet201 techniques attained lowest values. Whereas, the AIMACGD-SFST method attained highest performance with  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  99.07%, 97.83%, 99.07%, and 98.42%, correspondingly.

99.07%, 97.83%, 99.07%, and 98.42%, correspondingly.

Figure 9c depicts the comparative analysis of AIMACGD-SFST model with existing techniques on DS 3 dataset. The outcome reported that the Multiple CNNs, NASNetLarge, CNN, CNN-LSTM, DT, KNN, and SVM techniques attained lowest values. Meanwhile, the AIMACGD-SFST technique has obtained higher performance with  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  98.55%, 99.07%, 95.24%, and 96.97%, respectively.

98.55%, 99.07%, 95.24%, and 96.97%, respectively.

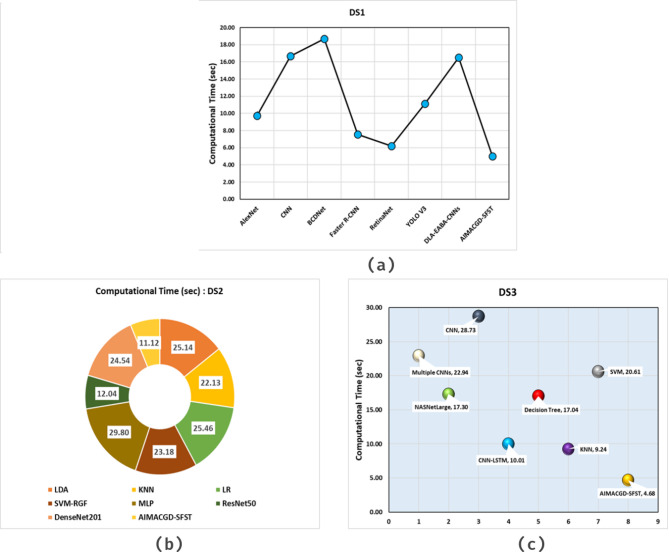

Table 5; Fig. 10 specify the computational time (CT) analysis of the AIMACGD-SFST approach with existing models. The result illustrates that the AlexNet, CNN, BCDNet, Faster R-CNN, RetinaNet, YOLO V3, and DLA-EABA-CNNs models attained worse performance. Whereas, the AIMACGD-SFST model attained lower CT of 5.02 s.

Table 5.

CT evaluation of AIMACGD-SFST approach on DS 1, DS 2, and DS 3 datasets.

| Dataset | Technique | CT (s) |

|---|---|---|

| DS 1 | AlexNet | 9.74 |

| CNN | 16.69 | |

| BCDNet | 18.70 | |

| Faster R-CNN | 7.54 | |

| RetinaNet | 6.18 | |

| YOLO V3 | 11.11 | |

| DLA-EABA-CNNs | 16.52 | |

| AIMACGD-SFST | 5.02 | |

| DS 2 | LDA | 25.14 |

| KNN | 22.13 | |

| LR | 25.46 | |

| SVM-RGF | 23.18 | |

| MLP | 29.80 | |

| ResNet50 | 12.04 | |

| DenseNet201 | 24.54 | |

| AIMACGD-SFST | 11.12 | |

| DS 3 | Multiple CNNs | 22.94 |

| NASNetLarge | 17.30 | |

| CNN | 28.73 | |

| CNN-LSTM | 10.01 | |

| DT | 17.04 | |

| KNN | 9.24 | |

| SVM | 20.61 | |

| AIMACGD-SFST | 4.68 |

Fig. 10.

CT evaluation of AIMACGD-SFST approach with existing models.

Figure 10b demonstrate the CT evaluation of the AIMACGD-SFST technique with existing approaches on DS 2 dataset. The result highlighted that the LDA, KNN, LR, SVM-RGF, MLP, ResNet50, and DenseNet201 techniques attained the worst performance. Whereas, the AIMACGD-SFST method attained lesser CT of 11.12 s.

Figure 10c portrays the CT evaluation of the AIMACGD-SFST model with existing techniques on DS 3 dataset. The outcome depicted that the Multiple CNNs, NASNetLarge, CNN, CNN-LSTM, DT, KNN, and SVM techniques obtained worst performance. Meanwhile, the AIMACGD-SFST technique attained the lowest CT of 4.68 s.

Table 6 indicates the Floating-Point Operations per second (FLOPs) and GPU memory consumption (in megabytes) comparison of the AIMACGD-SFST methodology69. The AIMACGD-SFST methodology demonstrates the lowest computational cost with only 0.79 GFLOPs and a minimal GPU memory requirement of 1200 MB, thus highlighting its suitability for deployment in resource-constrained environments. In contrast, models like UNet and TransUNet illustrate significantly higher FLOPs of 102.27 and 50.39, respectively, with GPU usage ranging from 3877 MB to 4918 MB, exhibitng a heavier computational load. SegNeXt, with 2.33 GFLOPs and 2657 MB GPU usage, balances performance and efficiency but still remains notably higher than the AIMACGD-SFST model, thus accentuating its compactness.

Table 6.

Comparison of computational complexity in terms of flops and GPU across various segmentation models.

| Method | FLOPs (G) | GPU (M) |

|---|---|---|

| UNet | 102.27 | 3877 |

| AttUNet | 104.00 | 2027 |

| TransUNet | 50.39 | 4918 |

| SegNeXt | 2.33 | 2657 |

| CariesAttNet | 14.44 | 4535 |

| AIMACGD-SFST | 0.79 | 1200 |

Conclusion

In this study, the AIMACGD-SFST model is presented. The AIMACGD-SFST technique comprises data collection, data preparation, feature reduction using COA, and ensemble learning models. The experimental validation of the AIMACGD-SFST approach is performed under three diverse datasets. The comparison study of the AIMACGD-SFST approach illustrated superior accuracy value of 97.06%, 99.07%, and 98.55% over existing models under diverse datasets. The limitations of the AIMACGD-SFST approach comprise limited generalizability across various datasets and domains, as the performance of the model was validated on a single benchmark dataset. The approach lacks thorough evaluation under real-time or streaming data conditions, which are critical for deployment in dynamic environments. Interpretability of the model remains a challenge, making it difficult for users to comprehend the rationale behind predictions. Furthermore, the absence of adaptive mechanisms may affect performance when dealing with growing attack patterns or concept drift. The model also encounters threats in scaling to RNA-Seq or whole-genome data due to high dimensionality and resource demands. Clinical deployment may be affected by data heterogeneity and batch effects. Moreover, the model lacks adaptability to streaming or real-time data, affecting performance in dynamic settings. Scalability under high-dimensional or large-scale data is not extensively analyzed.

The decision-making capabilities of the model could be enhanced in future studies by integrating domain knowledge or hybrid strategies and by incorproating expert insights with data-driven learning. This may also enhance accuracy and adaptability across diverse scenarios.

Future work may also consider improving robustness against adversarial noise for ensuring reliable performance when facing malicious or unexpected input perturbations, increasing the security and trustworthiness of the technique.

The broader applicability and real-time deployment may be enhanced by developing methods to enhance scalability and efficiency in handling high-dimensional or large-scale data. Such advancements will enable the model to perform reliably in more complex and resource-demanding environments.

Author contributions

J.D.D.J.: Conceptualization, formal analysis, writing-original draft. S.S.S.: Investigation, software, visualization. K.L.: Resources, investigation, software. R.K.: Data curation, methodology, validation. G.-H.S.: Data curation, resources, visualization. G.P.J.: Validation, supervision, writing-review and editing. W.C.: Funding acquisition, project administration, supervision.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at [https://csse.szu.edu.cn/staff/zhuzx/Datasets.html], reference number59.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Gyanendra Prasad Joshi, Email: joshi@kangwon.ac.kr.

Woong Cho, Email: wcho@kangwon.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Alromema, N., Syed, A. H. & Khan, T. A hybrid machine learning approach to screen optimal predictors for the classification of primary breast tumors from gene expression microarray data. Diagnostics13, 708. 10.3390/diagnostics13040708 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AbdElNabi, M. L. R., Wajeeh Jasim, M., El-Bakry, H. M., Taha, M. H. N. & Khalifa, N. E. M. Breast and colon cancer classification from gene expression profiles using data mining techniques. Symmetry12, 408. 10.3390/sym12030408 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Souza, J. T., De Francisco, A. C. & De Macedo, D. C. Dimensionality reduction in gene expression data sets. IEEE Access.7, 61136–61144. 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2915519 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dey, U. K. & Islam, M. S. Genetic expression analysis to detect type of leukemia using machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 1st International Conference on Advances in Science, Engineering and Robotics Technology (ICASERT), Dhaka, Bangladesh, 3–5 May 2019, vol. 12, 1–6. 10.1109/ICASERT.2019.8934628 (IEEE, 2020).

- 5.Akhand, M. A. H., Miah, M. A., Kabir, M. H. & Rahman, M. M. H. Cancer classification from DNA microarray data using mRMR and artificial neural network. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl.10, 106–111. 10.14569/IJACSA.2019.0100716 (2019).

- 6.Rukhsar, L. et al. Analyzing RNA-seq gene expression data using deep learning approaches for cancer classification. Appl. Sci.12, 1850. 10.3390/app12041850 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erkal, B., Ba¸sak, S., Çilo˘glu, A. & ¸Sener, D. D. Multiclass classification of brain cancer with machine learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2020 Medical Technologies Congress (TIPTEKNO), Antalya, Turkey, 19–20 November 2020, 1–4. 10.1142/S0219519425300029 (IEEE, 2020).

- 8.Hammood, N. M., Rashad, N. K. & Algamal, Z. Y. Neutrosophic Topp-Leone extended exponential distribution modeling with application for bladder cancer patients. Int. J. Neutrosophic Sci. (IJNS). 25 (1). 10.54216/IJNS.250122 (2025).

- 9.Daoud, M. & Mayo, M. A survey of neural network-based cancer prediction models from microarray data. Artif. Intell. Med.97, 204–214. 10.1016/j.artmed.2019.01.006 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alsayadi, H. A., Abdelhamid, A. A., El-Kenawy, E. S. M., Ibrahim, A. & Eid, M. M. Ensemble of machine learning fusion models for breast cancer detection based on the regression model. Fusion Pract. Appl.9 (2). 10.54216/FPA.090202 (2022).

- 11.Bouazza, S. H. A Deep ensemble gene selection and attention-guided classification framework for robust cancer diagnosis from microarray data. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res.15(1), 20235–20241. 10.1007/s10044-025-01446-5 (2025).

- 12.Li, M., Jin, C., Cai, Y., Deng, S. & Wang, L. MSGGSA: a multi-strategy-guided gravitational search algorithm for gene selection in cancer classification. Pattern Anal. Appl.28 (2). 10.1007/s10462-024-10954-5 (2025).

- 13.Wang, Y. C. et al. GOG-MBSHO: multi-strategy fusion binary sea-horse optimizer with Gaussian transfer function for feature selection of cancer gene expression data. Artif. Intell. Rev.57 (12). 10.1016/j.artmed.2024.102871 (2024).

- 14.Xie, Y. et al. Improving diagnosis and outcome prediction of gastric cancer via multimodal learning using whole slide pathological images and gene expression. Artif. Intell. Med.152, 102871 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sethi, B. K., Singh, D., Rout, S. K. & Panda, S. K. Long short-term memory-deep belief network-based gene expression data analysis for prostate cancer detection and classification. IEEE Access.. 12, 1508–1524. 10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3346925 (2023).

- 16.Jahanyar, B., Tabatabaee, H. & Rowhanimanesh, A. MS-ACGAN: A modified auxiliary classifier generative adversarial network for schizophrenia’s samples augmentation based on microarray gene expression data. Comput. Biol. Med.162, 107024. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107024 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Saheed, Y. K., Balogun, B. F., Odunayo, B. J. & Abdulsalam, M. Microarray gene expression data classification via Wilcoxon sign rank sum and novel Grey Wolf optimized ensemble learning models. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinf.20(6), 3575–3587. 10.1109/TCBB.2023.3305429 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Pashaei, E. & Pashaei, E. Hybrid binary COOT algorithm with simulated annealing for feature selection in high-dimensional microarray data. Neural Comput. Appl.35 (1), 353–374. 10.1007/s00521-022-07780-7 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahu, B. et al. Novel hybrid feature selection using binary Portia spider optimization algorithm and fast mRMR. Bioengineering12 (3). 10.3390/bioengineering12030291 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Kiliçarslan, S. & Dönmez, E. Improved multi-layer hybrid adaptive particle swarm optimization based artificial bee colony for optimizing feature selection and classification of microarray data. Multimed. Tools Appl.83 (26), 67259–67281. 10.1007/s11042-023-17234-4 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahu, B. et al. PDO-FA: A novel hybrid approach for feature selection from cancer datasets. Proc. Comput. Sci.258, 39–48. 10.1016/j.procs.2025.01.006 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shallangwa, I. Y., Ahmad, A. A. & Isuwa, J. Swarm intelligent optimization algorithms for precision gene selection in microarray-based cancer classification. Sci. World J.19 (3), 842–854. 10.4314/swj.v19i3.32 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahu, B. et al. Binary learning cooking algorithm with relief for feature selection of high-dimensional gene expression data. In 2025 International Conference on Emerging Smart Computing and Informatics (ESCI), 1–6. 10.1109/ESCI63694.2025.10988151 (IEEE, 2025).

- 24.Jeba, J. M. P. & Deepalakshmi, P. Selection of robust feature selection methods used for gene expression analysis of microarray data. In 2024 5th International Conference on Image Processing and Capsule Networks (ICIPCN), 918–924. 10.1109/ICIPCN63822.2024.00158 (IEEE, 2024).

- 25.Adhikari, A. et al. A two-stage ensemble feature selection and particle swarm optimization approach for micro-array data classification in distributed computing environments. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.04251. (2025).

- 26.Tabassum, F. et al. Precision cancer classification and biomarker identification from mRNA gene expression via dimensionality reduction and explainable AI. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.07260. (2024).

- 27.Gulande, P. & Awale, R. A hybrid mRMR-RSA feature selection approach for lung cancer diagnosis using gene expression data. Biomed. Pharmacol. J.18, 257–270. 10.13005/bpj/3086 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yaqoob, A., Verma, N. K., Aziz, R. M. & Shah, M. A. Optimizing cancer classification: a hybrid RDO-XGBoost approach for feature selection and predictive insights. Cancer Immunol. Immunother.73 (12). 10.1007/s00262-024-04821-8 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Nivetha, S., Anandakumar, K., Inbarani, H. H. & Khan, M. Explainable machine learning framework for gene expression-based biomarker identification and cancer classification using feature selection. Med. Data Min. 8(3), 19. 10.53388/MDM202508019 (2025).

- 30.Yaqoob, A., Verma, N. K. & Aziz, R. M. Optimizing gene selection and cancer classification with hybrid sine cosine and cuckoo search algorithm. J. Med. Syst.48 (1). 10.1007/s10916-024-01961-3 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Shukla, V., Mathur, A., Narayan, P. & Kishor, K. A multi-modal approach for the molecular subtype classification of breast cancer by using vision transformer and novel SVM polyvariant kernel. IEEE Access.10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3575126 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yaqoob, A., Verma, N. K., Aziz, R. M. & Saxena, A. Enhancing feature selection through metaheuristic hybrid cuckoo search and Harris hawks optimization for cancer classification. In Metaheuristics for Machine Learning: Algorithms and Applications, 95–134. 10.1002/9781394233953.ch4 (2024).

- 33.Jyothi, V., Srujana, M., Himasreeja, Y., Sanjana, S. S. & Fatima, B. Decoding tumor gene expression for multiclass cancer classification. In 2025 International Conference on Electronics and Renewable Systems (ICEARS), 1666–1670. 10.1109/ICEARS64219.2025.10941486 (IEEE, 2025).

- 34.Yaqoob, A., Verma, N. K., Aziz, R. M. & Shah, M. A. RNA-Seq analysis for breast cancer detection: a study on paired tissue samples using hybrid optimization and deep learning techniques. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol.150(10), 455. 10.1007/s00432-024-05968-z (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Nargis, A., Movania, M. M. & Siddiqui, S. Autoencoder-Integrated WideResNet with dynamic optimization (AIW-DynOpt): A novel hybrid deep learning approach for head and neck cancer gene expression analysis. J. Univers. Comput. Sci.31 (2). 10.3897/jucs.125224 (2025).

- 36.Yaqoob, A., Verma, N. K. & Aziz, R. M. Improving breast cancer classification with mRMR + SS0 + WSVM: a hybrid approach. Multimed. Tools Appl. 1–26. 10.1007/s11042-024-20146-6 (2024).

- 37.Motevalli, M., Khalilian, M. & Bastanfard, A. Optimizing the hybrid feature selection in the DNA microarray for cancer diagnosis using fuzzy entropy and the Giza pyramid construction algorithm. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Appl.24 (01). 10.1142/S1469026824500317 (2025).

- 38.Yaqoob, A. Combining the mRMR technique with the Northern goshawk algorithm (NGHA) to choose genes for cancer classification. Int. J. Inform. Technol. 1–12. 10.1007/s41870-024-01849-3 (2024).

- 39.Naccour, S., Moawad, A., Santer, M., Dejaco, D. & Freysinger, W. Machine learning-based classification of cervical lymph nodes in HNSCC: A radiomics approach with feature selection optimization. Cancers17 (16). 10.3390/cancers17162711 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Yaqoob, A., Mir, M. A., Jagannadha Rao, G. V. V. & Tejani, G. G. Transforming cancer classification: the role of advanced gene selection. Diagnostics14 (23). 10.3390/diagnostics14232632 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Shukla, A. K. et al. Optimized breast cancer diagnosis using self-adaptive quantum metaheuristic feature selection. Sci. Rep.15 (1). 10.1038/s41598-025-05014-z (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Yaqoob, A., Bhat, M. A. & Khan, Z. Dimensionality reduction techniques and their applications in cancer classification: a comprehensive review. Int. J. Genet. Modif. Recomb. 1 (2), 34–45. 10.37591/IJGMR (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li, H. & Cheng, T. Multicenter and multimodal ultrasound-based radiomics and transformer-driven end-to-end deep learning for breast cancer molecular subtype classification. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci.18 (3). 10.1016/j.jrras.2025.101656 (2025).

- 44.Yaqoob, A. et al. SGA-Driven feature selection and random forest classification for enhanced breast cancer diagnosis: A comparative study. Sci. Rep.15 (1). 10.1038/s41598-025-05014-z (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Palmal, S., Arya, N., Saha, S. & Tripathy, S. Integrative prognostic modeling for breast cancer: unveiling optimal multimodal combinations using graph convolutional networks and calibrated random forest. Appl. Soft Comput.154 (111379). 10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111379 (2024).

- 46.Uma Kandan, S., Alketbi, M. M. & Al Aghbari, Z. Multi-input CNN: a deep learning-based approach for predicting breast cancer prognosis using multi-modal data. Discover Data. 3 (1). 10.1007/s44248-025-00021-x (2025).

- 47.Yaqoob, A. & Verma, N. K. Feature selection in breast cancer gene expression data using KAO and AOA with SVM classification. J. Med. Syst.49(1), 1–21. 10.1007/s10916-025-01704-0 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Zhao, G. & Li, D. TreeEM: Tree-enhanced ensemble model combining with feature selection for cancer subtype classification and survival prediction. Results Appl. Math.27 (100605). 10.1016/j.rinam.2025.100605 (2025).

- 49.Wang, J., Zhang, Z. & Wang, Y. Utilizing feature selection techniques for AI-driven tumor subtype classification: enhancing precision in cancer diagnostics. Biomolecules. 15 (1). 10.3390/biom15010081 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Nagra, A. A. et al. A gene selection algorithm for microarray cancer classification using an improved particle swarm optimization. Sci. Rep.14 (1). 10.1038/s41598-024-46035-5 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Agustriawan, D. et al. Framework for race-specific prostate cancer detection using machine learning through gene expression data: feature selection optimization approach. JMIR Bioinform. Biotechnol.6(1), e72423. 10.2196/72423 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Das, A., Neelima, N., Deepa, K. & Özer, T. Gene selection based cancer classification with adaptive optimization using deep learning architecture. IEEE Access.12, 62234–62255. 10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3392633 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lawrence, M. O., Jimoh, R. G. & Yahya, W. B. An efficient feature selection and classification system for microarray cancer data using genetic algorithm and deep belief networks. Multimed. Tools Appl.84 (8), 4393–4434. 10.1007/s11042-024-18802-y (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sucharita, S., Sahu, B., Swarnkar, T. & Meher, S. K. Classification of cancer microarray data using a two-step feature selection framework with moth-flame optimization and extreme learning machine. Multimed. Tools Appl.83 (7), 21319–21346. 10.1007/s11042-023-16353-2 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dhamercherla, S., Reddy Edla, D. & Dara, S. Cancer classification in high dimensional microarray gene expressions by feature selection using eagle prey optimization. Front. Genet.16, 1528810. 10.3389/fgene.2025.1528810 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Tabassum, N., Kamal, M. A. S., Akhand, M. A. H. & Yamada, K. Cancer classification from gene expression using ensemble learning with an influential feature selection technique. BioMedInformatics4 (2), 1275–1288. 10.3390/biomedinformatics4020070 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alkamli, S. S. & Alshamlan, H. M. Performance evaluation of hybrid Bio-Inspired and deep learning algorithms in gene selection and cancer classification. IEEE Access. (2025).

- 58.Senbagamalar, L. & Logeswari, S. Genetic clustering algorithm-based feature selection and divergent random forest for multiclass cancer classification using gene expression data. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst.17 (1). 10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3556816 (2024).

- 59.https://csse.szu.edu.cn/staff/zhuzx/Datasets.html

- 60.Elabd, E., Hamouda, H. M., Ali, M. A. & Fouad, Y. Climate change prediction in Saudi Arabia using a CNN GRU LSTM hybrid deep learning model in al Qassim region. Sci. Rep.15 (1), 1–19. 10.1038/s41598-025-67098-4 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Challa, A., Vutukuri, A., Kenguva, M. & Kanagala, S. K. February. Automated data preprocessing and training interface for machine learning applications. In AIP Conference Proceedings, vol. 2942, No. 1. 10.1063/5.0196137 (AIP Publishing, 2024).

- 62.Kausar, F. & Ramamurthy, B. Coati optimization algorithm for detecting pediatric kidney abnormalities using ultrasound images, 10.5281/zenodo.7896543

- 63.Duan, X. et al. Simulation study of deep belief Network-Based rice transplanter navigation deviation pattern identification and adaptive control. Appl. Sci.15 (2). 10.3390/app15020790 (2025).

- 64.Wang, Y. et al. TCN–Transformer spatio-temporal feature decoupling and dynamic kernel density Estimation for gas concentration fluctuation warning. Fire8 (5). 10.3390/fire8050175 (2025).

- 65.Chen, K., Mao, Z., Zhao, H., Jiang, Z. & Zhang, J. A variational stacked autoencoder with harmony search optimizer for valve train fault diagnosis of diesel engine. Sensors. 20 (1). 10.3390/s20010223 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Puttegowda, K. et al. Enhanced machine learning models for accurate breast cancer mammogram classification. Glob. Transit. 10.1016/j.glt.2025.04.007 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Prabhakar, S. K. & Lee, S. W. An integrated approach for ovarian cancer classification with the application of stochastic optimization. IEEE Access8, 127866–127882. 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2992325 (2020).

- 68.Bappi, J. O., Rony, M. A. T., Islam, M. S., Alshathri, S. & El-Shafai, W. A novel deep learning approach for accurate cancer type and subtype identification. IEEE Access.10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3145678 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang, Z. et al. CariesAttNet: an Attention-Enhanced Encoder-Decoder network for automated caries segmentation in CBCT images (June 2025). IEEE Access.10.1109/ACCESS.2025.3145678 (2025).41221151 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Akhand, M. A. H., Miah, M. A., Kabir, M. H. & Rahman, M. M. H. Cancer classification from DNA microarray data using mRMR and artificial neural network. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl.10, 106–111. 10.14569/IJACSA.2019.0100716 (2019).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at [https://csse.szu.edu.cn/staff/zhuzx/Datasets.html], reference number59.