Abstract

Background

Risankizumab was an approved novel drug by Japan for psoriasis, we aimed to explore its underlying therapeutic mechanism through the single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) technology.

Methods

ScRNA-seq data (GSE228421) were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. Quality control, normalization, clustering, and cell-type annotation were performed using the R packages Seurat and harmony, together with the CellMarker2.0 database. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the FindMarkers function, and functional enrichment analysis of DEGs was conducted with the ClusterProfiler R package. Cell differentiation trajectories were inferred by pseudo-time analysis using the Monocle2 package. In addition, THP-1 monocytes were differentiated into macrophages and treated with different concentrations of risankizumab. Cell viability was assessed by CCK-8 assay, while cytokine production (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13) was measured using ELISA to evaluate the effects of risankizumab on inflammatory responses and macrophage polarization.

Results

A total of 97,434 cells were analyzed and divided into eight major clusters. Among them, myeloid cells showed the most significant reduction following risankizumab treatment, suggesting that they may be the primary target of the therapy in psoriasis. Functional enrichment analysis revealed that antibacterial humoral response, antimicrobial humoral response, and keratinization activities in myeloid cells were markedly inhibited. Further analysis identified three macrophage subtypes, and risankizumab treatment was found to promote differentiation of anti-inflammatory IL10⁺ M2 macrophages while reducing IL6⁺ M1 macrophages, thereby contributing to the control of psoriasis. Consistently, in-vitro experiments demonstrated that risankizumab suppressed the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and enhanced M2 macrophage polarization, confirming its immunomodulatory role.

Conclusions

This study reveals that risankizumab exerts its anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting M1-type and promoting M2-type macrophage polarization, thereby elucidating its key mechanism for treating psoriasis and providing theoretical support for novel immunotherapy targets.

Keywords: Risankizumab, Psoriasis, Pseudo-time analysis, Myeloid cells, Anti-inflammatory

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, recurrent, immune-mediated skin disease with a prevalence of about 3.2% in the population and is frequently associated with comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus, arthritis, dyslipidemia, myasthenia gravis, and cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases [1]. Clinically, it presents with multiple subtypes, including guttate, plaque (> 80% of cases), pustular, inverse, and erythrodermic psoriasis, imposing substantial physical and psychological burdens on patients [2]. Lesions may occur on the soles, elbows, trunk, palms, genitals, scalp, knees, or nails, typically manifesting as well-demarcated erythematous plaques covered with silvery-white or gray scales [3, 4]. The disease course and severity vary greatly, ranging from localized tear-shaped papules to generalized erythema and scaling, and symptoms often include intense pruritus or burning sensation [5]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for more in-depth research into the pathogenesis of psoriasis.

A number of immune cell groups mediated the pathogenesis of psoriasis, including the keratinocytes, lymphocytes and dendritic cells. The immune system disorder in the skin facilitated the proliferation of epidermal keratinocytes, causing the distinctive thickened, scaly plaques of psoriasis [6]. Studies demonstrated that IL-23 and IL-17 pathways were closely associated with the pathogenesis of psoriasis [7]. In the beginning, psoriasis onset is triggered when the environmental and/or genetic factors activated plasmacytoid dendritic cells, antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and helper T cells type 17 (Th17) cells that produced a number of proinflammatory cytokines, such as the Interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and Interleukin (IL)-17, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-22 and IL-23 involved in the protection against infections on mucosal and epithelial surfaces, especially the infections of candida and staphylococcus that are key drivers of skin inflammation [8]. However, an aberrant production of these cytokines disrupted the appropriate immune responses and stimulated the epidermal and keratinocyte hyperproliferation and differentiation that perpetuated a cycle of chronic inflammation [9]. The evidences form the moderate-to-severe psoriasis indicated that the elevated proinflammatory cytokines not only were observed in the skin lesions, but also presented in the blood [10]. Systematic increase of these cytokines can aggravate chronic subclinical inflammation (or asymptomatic inflammation that causes tissue damage over time) related to multiple comorbidities, such as the inflammatory bowel disease, psoriatic arthritis (PsA), cardiovascular disease (CVD), and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), to promote psoriasis progression [11]. It is proposed that the systemic treatment of targeting psoriasis pathogenesis-related proinflammatory cytokines will not only relieve the cutaneous symptoms, but also decrease the systemic inflammation, and improving long-term outcomes of psoriasis through ameliorating its comorbidity progression [12].

Risankizumab was an IL-23 p19 inhibitor [13], and approved for the severe plaque psoriasis treatment in adults who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy [14]. Meanwhile, Risankizumab was also to evaluate the treatment of Crohn disease, psoriatic arthritis, hidradenitis suppurativa, ankylosing spondylitis and ulcerative colitis [15, 16]. After subcutaneous injection, the absolute bioavailability of risankizumab approximately is 89%, the estimated systemic clearance of patients with 11.2 L distribution volume was 0.31 L/day and the terminal elimination phase was approximately 28 days [17], but its metabolic pathway has not been characterized. In the clinical pharmacology, the Risankizumab was a monoclonal antibody of human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) that bind to the p19 subunit IL-23 cytokine and blocked its interaction with IL-23 receptor, and inhibited the release of chemokines and proinflammatory cytokines, the reduced activity of IL-23 was associated with the decreasing immune responses and inflammatory [13]. The newer biologic therapies of Risankizumab targeting the immunologic signaling pathways and cytokines provided notable clinical improvement of psoriasis, the deeper understanding of its therapeutic mechanism to psoriasis can help the identification and developing new targets for future therapeutic. This study downloaded the single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data of baseline lesion and risankizumab treatment and performed a comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis, a total of 8 main cell clusters from 97,434 cells were identified and the cell proportion analysis revealed the cell alteration after Risankizumab treatment. We found that the macrophages played an important role in mediating the decreased inflammatory response; moreover, the macrophages were the target cells of Risankizumab and polarizing to the anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage were identified in-vitro experiment.

Materials and methods

Data download and preprocessing

We downloaded the scRNA-seq data set of GSE228421 from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) [18, 19], and the baseline lesion sites samples and risankizumab treatment of 14 day samples were retained in this study. The “Seurat” package was applied for the quality control and single-cell analysis [20], in which the Read10X function was used to read the expression matrix, cells expressed 200–3,000 genes that presented at least 3 cells and possessed < 10% mitochondrial genes and > 1000 unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) were retained, then the SCTransform function was performed the data normalization and the RunPCA function was used for the principal component analysis (PCA). Subsequently, the “harmony” R package was used to remove the batch effect between samples, the top 20 principal components was conducted the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) dimensionality reduction, and the FindNeighbors and FindClusters functions were used to identify the major cell clusters and the optimal cluster resolution consecutively. To accurately annotate cell types, the CellMarker2.0 database (https://www.labome.com/method/Cell-Markers.html) provide the marker genes for each cell type. The myeloid cells and macrophage performed the same cell typing method [20].

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) among various cultures were identified using the FindMarkers function, setting |log2-fold change|≥ 1, logfc.threshold = 0.25, min.pct = 0.25 and only.pos = TRUE, then the GSEA was performed on DEGs for the significantly enriched genes (p < 0.05) by suing the “ClusterProlifer” R package [21], in which the gseGO function was used to view the biological process (BP) and the “GseaVis” R package was used to present the significantly enriched genes in specific enrichment pathways [22]. In addition, the interest genes were up-loaded to the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) database for their biological process and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis [22].

Pseudo-time trajectory analysis

The “Monocle2” R package (v2.22.0) was employed to infer the pseudo-time differentiation trajectory of macrophage from the Baseline to risankizumab treatment [23]. First, the CDs object was developed using the newCellDataSet function and the DEGs among Baseline and risankizumab groups (avg_log2FC > 0.25 and p_val_adj < 0.01) were identified by the FindAllMarkers function. Then, the reduceDimension function was performed the dimensionality reduction and trajectory (max_components = 2, method = “DDRTree”) based on the DEGs, the orderCells function was used to set the start point of trajectory based on the cells in the baseline group. Finally, we used the differentialGeneTest function to calculate the Pseudotime-related genes (fullModelFormulaStr = " ~ sm.ns and qval < 0.01) and the plot_pseudotime_heatmap function was used to show the genes expression with the pseudotime [23].

Cell culture and drug treatment

Human monocyte cell line THP-1 was incubated in RPMI 1640 medium (Corning, Inc., Corning, NY, USA) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma, USA) and 200 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, Sigma, Darmstadt, Germany) for 24 h to obtain the differentiated macrophages [24]. Risankizumab was purchased from the Boehringer Ingelheim (Ingelheim, Germany) and stored in − 20 °C, and was configured with 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20 ng/mL for 12, 24 and 36 h cell incubation, respectively, and the cell viability and cytokines production were further measured.

Cell viability assay

Cells differentially following the treatment with Risankizumab were cultured at a density of 1 × 103 cells per well in 96-well plates. CCK-8 solution (#C0038, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was added to the cells at specific timepoints [25]. The O.D 450 values of each well were detected after incubation at 37 °C for 2 h using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) [26].

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISA assay kit (Multisciences, Hangzhou, China) was applied to perform ELISA using double antibody sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technology [25]. Briefly, a high-affinity enzyme-labeled plate was pre-coated with the specific antibody for 1 h and then added with standards, samples to be tested and biotinylated detection antibodies. After 2-h incubation, unbound material was removed by the addition of washing buffer, and the horseradish peroxidase-labeled streptavidin (Streptavidin–HRP) was added for culture of 1 h [25]. After washing, the color development substrate TMB was added to develop color in the dark. Next, termination solution was added to terminate the reaction, and the absorbance value was measured at 450 nm [27].

Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR)

The collected cells were used for the total RNA extraction by the TRIzol reagent kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), then the FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Sigma, Germany) was used to perform qRT–PCR of the extracted RNA from each sample (2 μg) on a LightCycler 480 PCR System (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) [25]. The cDNA served as a template with a reaction volume of 20 μl. The PCR reactions were as follows: Cycling conditions began with an initial DNA denaturation phase at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 45 cycles at 94 °C for 15 s, 56 °C for 30 s, and ended at 72 °C for 20 s. Using the 2-ΔΔCT method, the data from the threshold cycle (CT) were standardized to the level of GAPDH. Table 1 lists the specific primers. All the experiments were performed in triplicate.

Table 1.

Specific primers for qRT–PCR

| Gene | Forward primer sequence (5′–3′) | Reverse primer sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| C1QB | CGGGTATCCCTGGGACACCTG | GCCGACTTTTCCTGGATTCCCA |

| CTSD | GCAAACTGCTGGACATCGCTTG | GCCATAGTGGATGTCAAACGAGG |

| S100A8 | ATGCCGTCTACAGGGATGACCT | AGAATGAGGAACTCCTGGAAGTTA |

| CD206 | AGCCAACACCAGCTCCTCAAGA | CAAAACGCTCGCGCATTGTCCA |

| CD209 | GCAGTCTTCCAGAAGTAACCGC | GCTCTCCTCTGTTCCAATACTGC |

| IDO1 | GCCTGATCTCATAGAGTCTGGC | TGCATCCCAGAACTAGACGTGC |

| NFE2L2 | CACATCCAGTCAGAAACCAGTGG | GGAATGTCTGCGCCAAAAGCTG |

| GAPDH | GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG | ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA |

Statistical analysis

R software (version 4.3.1) and GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0.2, GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) were used to complete the all statistical analysis and data visualization. The Shapiro–Wilk test results determined the application of the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Student’s t test for comparing the two groups. Spearman’s coefficient was utilized to conduct the correlation analysis. In addition, all in vitro experiments were performed in triplicate, with results expressed as mean ± SD. Comparisons between two groups were performed using Student's t test, while comparisons among multiple groups were conducted using one-way ANOVA. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

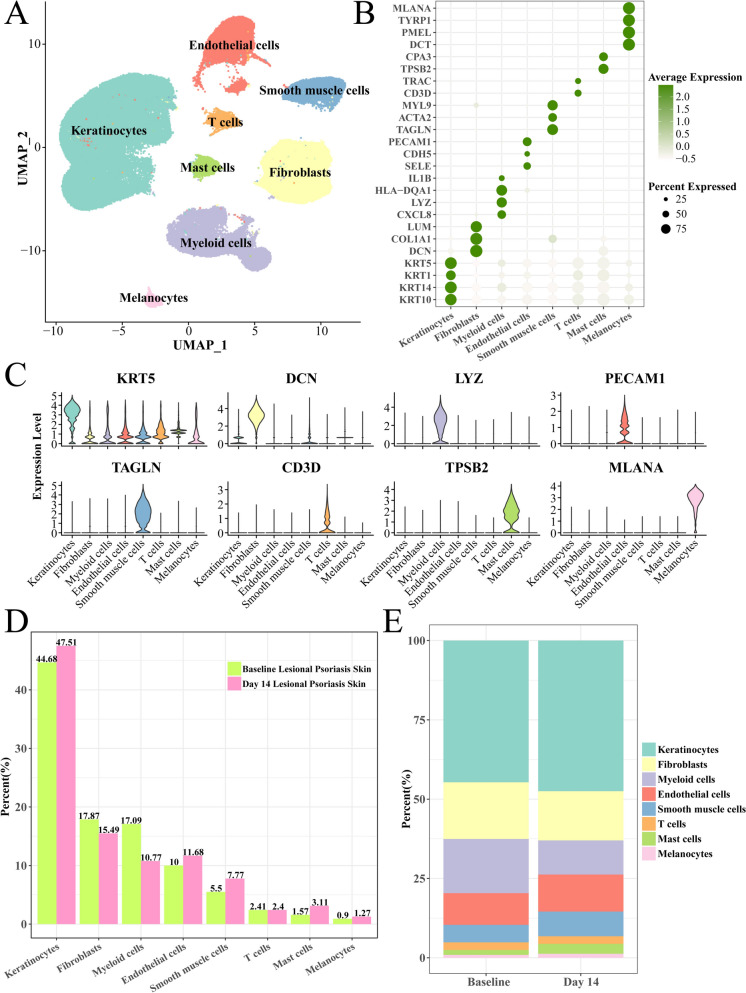

Myeloid cells were significantly decreased after risankizumab treatment

After quality control and scRNA-seq analysis, we obtained 97,434 cells and identified 8 mainly cell clusters (Fig. 1A), such as the endothelial cells, Smooth muscle cells, keratinocytes, mast cells, Fibroblasts, Myeloid cells and Melanocytes. The endothelial cells expressed the PECAM1, CDH5 and SELE marker, Smooth muscle cells with the TAGLN, ACTA2 and MYL9 marker, keratinocytes had high expression of KRT10, KRT14 and 5, Fibroblasts specifically expressed the DCN, COL1A1 and LUM genes, Myeloid cells with highly expression of CXCL8, LYZ and HLA–DQA1 genes (Fig. 1B, C). Interestingly, compared with the baseline group, the Myeloid cells had the largest decreasing proportion after risankizumab treatment from 17.09 to 10.77%, secondary is Fibroblasts from 17.87% to 15.49% (Fig. 1D, E), suggesting the decreasing of Myeloid cells that mediated inflammatory response may be a potential mechanism of risankizumab treating psoriasis.

Fig. 1.

Single-cell landscape of psoriasis following risankizumab treatment. A Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot of cell clusters and annotations. B Bubble plot of marker gene expression of each cell cluster. C Violin plot of marker gene expression. D Proportion of each cell type among baseline and risankizumab groups. E Columnar accumulation plot of each cell type

Risankizumab decreased the keratinization and inflammatory response in the myeloid cells

To elucidate the gene expression alteration of myeloid cells after 14-day risankizumab treatment, we analyzed the differentially enriched genes among baseline and risankizumab groups. Results showed that the antibacterial humoral response and keratinization activities of myeloid cells in the risankizumab group were significantly inhibited, while the activities of T helper cell differentiation, vascular permeability regulation, negative regulation of leukocyte activation, negative regulation of cytokine production, and negative regulation of cell cycle were significantly enhanced (Fig. 2A). In the keratinization pathway, the KRT6A, KRT16 and KRT1, KRT5, KRT6B, and SFN were significantly down-regulated (Fig. 2B), these genes including the HLA–DRB1, CD274, FBXO7, ITCH, FCGR2B, HMGB3, AXL and DUSP22 were significantly up-regulated in the negative regulation of leukocyte activation pathway (Fig. 2C), and the genes containing the TLR4, PDCD, HMOX1, SMAD7, AXL and NMB were significantly overexpressed in the negative regulation of cytokine production pathways (Fig. 2D). In addition, the specific marker genes of keratinization, such as KRT6A, KRT16, SFN and KRT5 were elevated in the baseline group (Fig. 2E), the specific marker genes of negative regulation of leukocyte activation pathway (FCGR2B, LGALS9, IDO1, LILRB2 and HAVCrR2) had significantly overexpression in the risankizumab group (Fig. 2F), implying the key keratinization and inflammatory response in the myeloid cells were inactivated after risankizumab treatment.

Fig. 2.

GSEA analysis of myeloid cells between risankizumab and baseline groups. A NES plot of day 14 risankizumab vs baseline. B GSEA plot of Keratinization pathway. C GSEA plot of Negative regulation of leukocyte activation pathway. D GSEA plot of negative regulation of cytokine production pathway. The red line represents the running enrichment score across the ranked gene list, where the peak indicates the maximum enrichment score. The heatmap at the bottom illustrates the distribution of gene expression: red indicates up-regulation in the baseline group, while blue indicates up-regulation in the risankizumab group. E Bubble plot of keratinization-related genes expression between baseline and day 14 groups. F Bubble plot of negative regulation of lumphocyte activation-related genes expression between baseline and day 14 groups

Macrophages may be a potential target myeloid cell of Risankizumab for anti-inflammatory

We further sub-divided the myeloid cells into 7 mainly sub-groups to explore its heterogeneity, including the conventional dendritic cells 1 (cDCs 1) and cDCs 2, basal cells, langerhans cells, monocytes, macrophages and fibroblasts (Fig. 3A). Their specific marker genes are shown in Fig. 3B, such as the macrophages significantly expressed the CCL18, FOLR2 and CD163 genes. Then, we compared the number of these cells in baseline and risankizumab samples, and found that the proportion of macrophages had obvious decreased from the 21.41 to 17.24% (Fig. 3C), indicating the macrophages was the key target of risankizumab to anti-inflammatory. Meanwhile, we also demonstrated that the specific high expression genes of macrophages were closely associated with the NF-kappa B, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF), chemokines and interleukin-17 (IL-17) pathways that contributed to pro-inflammatory response (Fig. 3D), the genes of CXCL8, TNFAIP3, CXCL3, CXCL2, MMP9 and NFKBIA in the IL-17 signaling pathway were significantly overexpressed in the macrophages (Fig. 3E) and the marker genes of NF-kappa B signaling pathway, such as the CXCL8, CXCL3, CXCL4 and CXCL2, ICAM1, NFKBIA and TLR4 were up-regulated in the macrophages (Fig. 3F). Overall, these genes all supported the pro-inflammatory response.

Fig. 3.

Landscape of myeloid cells. A UMAP plot of myeloid cells. B Bubble plot of marker genes expression of each cell cluster. C Proportion of myeloid cell sub-cluster in baseline and risankizumab groups. D KEGG analysis of highly expressed genes in macrophage. E Expression levels of genes within the IL-17 pathway in myeloid cell subsets. F Expression levels of genes within the NF-kappa B pathway in myeloid cell subsets

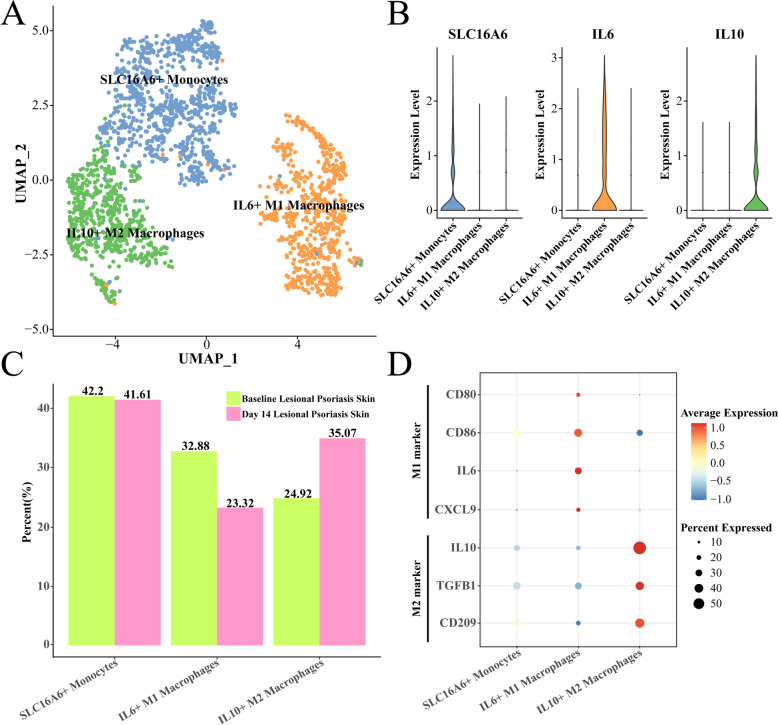

Risankizumab decreased the M1 and increased the M2 macrophages for psoriasis controlling

The macrophages were further divided into three sub-groups, including the SLC16A6 + monocytes, IL6 + M1 macrophages and IL10 + M2 macrophages (Fig. 4A), in which the IL6 and IL10 were the classic marker genes of macrophage M1 and M2, respectively (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, we found that the proportion of IL6 + M1 macrophage was decreased from the 32.88% to 23.32% after risankizumab treatment, while on the contrary, the IL10 + M2 macrophage was increased from the 24.92% to 35.07% (Fig. 4C), and the M2 marker genes such as the CD209, TGFB1 and IL10 were significantly overexpressed in the IL10 + M2 macrophage (Fig. 4D), suggesting the risankizumab treatment controlled the development of psoriasis through decreasing the pro-inflammatory macrophages M1 and increasing the anti-inflammatory macrophages M2 numbers.

Fig. 4.

Changes in macrophage subsets after 14 days of risankizumab treatment. A UMAP of further subdivision of macrophages. B Expression level of marker genes in each macrophage sub-group. C Proportion of macrophage sub-groups between baseline and day 14 samples, respectively. D Expression levels of M1 type and M2 marker genes among macrophage sub-groups

Risankizumab induced anti-inflammatory macrophages M2 differentiation

We performed the pseudotime analysis of macrophages to explore the differentiation trajectory of M1 and M2 macrophages during the risankizumab treatment. For the IL6 + M1 macrophage trajectory, the baseline cells were at start point of trajectory and differentiated into three directions and characterized by baseline cells or IL6 + M1 macrophage (Fig. 5A), with the development of pseudotime, the expression of pro-inflammatory genes, such as C1QB, CTSD and S100A8 was decreased (Fig. 5B). The IL10 + M2 macrophages also exhibited multiple differentiation fates from the baseline cells (Fig. 5C), the antigen presenting genes, such as HLA-C, HLA–DPB1 and HLA–DQA2 were down-regulated, while the anti-inflammatory genes including the CD206, CD209 and IDO1 elevated with the pseudotime (Fig. 5D), indicating that risankizumab induced the differentiation of baseline cells to the anti-inflammatory macrophages M2.

Fig. 5.

Differentiation trajectories of M1 and M2 macrophages during risankizumab treatment. A Differentiation trajectories of IL6 + M1 macrophages during risankizumb treatment. B Changes in the expression levels of time-related genes in IL6 + M1 macrophages. C Differentiation trajectories of IL10 + M2 macrophages during risankizumb treatment. D Changes in the expression levels of time-related genes in IL10 + M2 macrophages

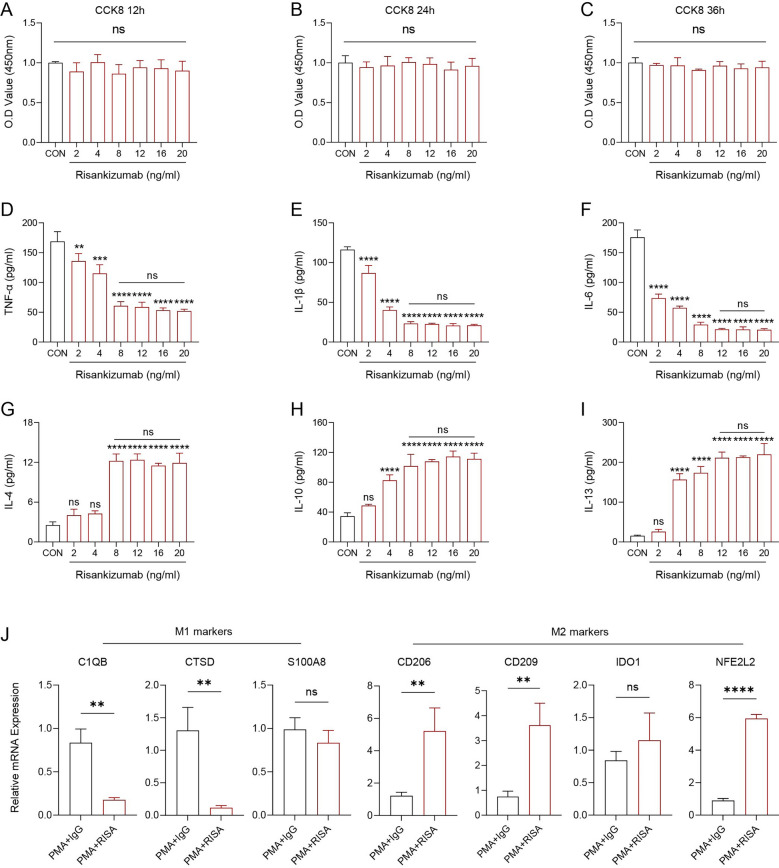

Risankizumab inhibited pro-inflammatory factors production and promoted macrophages M2 polarizing in vitro

Finally, we measured the effects of Risankizumab to the cell viability and cytokines production of monocyte THP-1. After treatment with different concentration of Risankizumab and at different time points, we found that the cell viability had no obvious difference (p > 0.05, Fig. 6A–C), suggesting that treatment time and concentration did not affect cell viability of THP-1 cells in vitro. Subsequently, we measured the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines levels in the THP-1 cell treated with different concentrations of Risankizumab. Accordingly, results of ELISA demonstrated that the concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were significantly decreased (p < 0.05, Fig. 6D–F), while the anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 were significantly elevated with the increasing Risankizumab, and the optimal therapeutic concentration was 8 ng/mL (p < 0.05, Fig. 6G–I). We applied the PMA stimulation of THP-1 cells to obtain the macrophages and followed by the addition of IgG and Risankizumab to explore the effect of Risankizumab on macrophage polarization. The results of qRT–PCR presented that Risankizumab significantly inhibited the M1 markers C1QB and CTSD expression (p < 0.05, Fig. 6J), while the expression of M2 markers, such as the CD206, CD209 and NFE2L2 were significantly up-regulated in the PAM + RISA group (Fig. 6J), demonstrating that Risankizumab promoted the macrophages polarizing to M2 phenotype.

Fig. 6.

Risankizumab promoted M2 polarization of macrophages. A-C Changes in cell viability of THP-1 after stimulation with different concentrations of Risankizumab at different time points and relative quantitative analysis. D–I Alterations of cytokines in the culture medium supernatants of THP-1 after stimulation with different concentrations of Risankizumab were quantified. J Changes in the direction of M1/M2 polarization of THP-1 before and after Risankizumab stimulation. All procedures were performed in triplicate (n = 3). The results are presented as mean ± SD, *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001 and nsp > 0.05.

Discussion

Psoriasis was a chronic inflammatory mediating skin disease that was associated with multiple other diseases and affected more than 60 million children and adults worldwide. In the past 20 years, the genetic and immunological studies highlighted the causal immunological circuits that focused on the adaptive immune pathways of IL-17 and IL-23, the crucial role of TNF-α and Th17 responses and keratinocyte hyperproliferation. Meanwhile, the definition of histological remission features of psoriasis included the (i) normalization of keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation as measured by Ki-67 immunostaining; (ii) reduction of pathologic inflammatory cell population (such as T cells and dendritic cells); (iii) reduction of epidermal hyperplasia; (iv) restoration of orthokeratosis and granular layer [28]. Risankizumab was an approved IL-23 p19 inhibitor for the treatment of severe plaque psoriasis, we performed a comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis and elucidated the target cells of risankizumab and its underlying mechanism of psoriasis treatment in present study.

We compared the cell alteration after risankizumab treatment at single-cell resolution, and found that the numbers of myeloid cells were significantly decreased. Previous studies reported that the hyperproliferation and differentiation of keratinocytes combined with the increasing myeloid cells infiltration in the dermal layer were a classic histological feature of psoriasis [29], in which the myeloid cells, such as the monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs) and neutrophils were the mainly contributor to host inflammation response [30] mediating the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and vascular phenotype (vascular inflammation) [31]. The ROS-activated proinflammatory signals played a crucial relevance in psoriasis’s immunoregulation of contributing to the recruitment of inflammatory cells and aggravating inflammatory cascade [32], both myeloid cells and the keratinocytes were the oxidative stress sources [33]. The vascular phenotype was closely associated with the neutrophil’s infiltration, which produced ROS production mediating vascular inflammation in patients with severe psoriasis [34]. The decreased coronary inflammation in the moderate to severe psoriasis after biotherapy hinted the correlation between vascular inflammation and skin disease [35]. In addition, the inhibited antimicrobial humoral response and keratinization activities, and the enhanced T helper cell differentiation, vascular permeability regulation, negative regulation of leukocyte activation, negative regulation of cytokine production of myeloid cells also supported the lower inflammation that mediated by myeloid cells. These evidences supported that the risankizumab induced the decreasing of myeloid cells to reduce the inflammatory response of psoriasis.

Notably, in this study, the functional relevance of M1 and M2 macrophages was directly supported by both single-cell transcriptomic data and in vitro validation. The scRNA-seq analysis demonstrated a marked reduction in IL6 + M1 macrophages and a concomitant increase in IL10 + M2 macrophages following risankizumab treatment. Pseudotime trajectory analysis further revealed a shift in differentiation toward the M2 phenotype, characterized by the upregulation of anti-inflammatory genes, such as CD206, CD209, and IDO1. These transcriptomic findings were consistent with our in vitro assays, in which risankizumab significantly downregulated pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) and upregulated anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13). Together, these results indicate that the therapeutic effect of risankizumab is not only associated with a reduction in pro-inflammatory macrophage activity but also with an active promotion of M2 polarization, highlighting a specific immunoregulatory mechanism rather than a generalized anti-inflammatory response. Previous studies revealed that the IL-23 is a member of IL-6 family and produced by several cells, such as keratinocytes and macrophages to defend against bacteria and fungi infection [36], the IL6 + M1 macrophages often induced by IFN-γ have the capacity of antigen presentation and production of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and IL-23 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α mediating anti-inflammatory response [37, 38]. In contrast, the IL-4 induced M2 macrophages that produced the IL-10 and over-expressed several reporters, such as mannose receptor, CD209, CD163, dectin-1, class A scavenger receptor (CD204), promoting anti-inflammatory response, angiogenesis and tissue remodeling [39, 40], Huang el at, reported that the Foxp3–Treg-of-B cells induced the polarization of M2-like macrophages that ameliorated the imiquimod-induced psoriasis [41]. Several IL-23 inhibitors, such as guselkumab and tildrakizumab, have also been shown to reduce inflammatory cell infiltration in psoriatic lesions [42, 43]. Previous studies reported that these agents similarly attenuate the expansion of myeloid populations and downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokine production [44]. Our findings that risankizumab decreases myeloid cell abundance and promotes M2 macrophage polarization suggest that its mechanism is largely consistent with the broader IL-23 blockade strategy [45]. However, the specific induction of IL10 + M2 macrophages observed in our data set may indicate a more distinct immunoregulatory profile, highlighting the need for future comparative studies to clarify whether this represents a shared or unique feature of risankizumab therapy. In addition, we also demonstrated that the risankizumab promoted the polarization of M1 macrophages to M2 macrophages with the increasing of IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13 and the decreasing of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in vitro experiment, these evidences supported that the decreasing IL6 + M1 macrophages and the increasing IL10 + M2 macrophages may be the underlying treatment mechanism of risankizumab to psoriasis.

It should be noted that this study has certain limitations. First, the single-cell RNA sequencing data used in this study were obtained solely from public databases, with a limited sample size that may affect the generalizability of the results. Future work could expand the sources of samples, incorporate more patient cohorts and data from different populations, and conduct multi-center validation. Second, the pseudo-temporal trajectory infers cellular differentiation direction solely based on transcriptomic profiles, yielding results that are speculative and lack direct validation through sequential experiments. Future studies should incorporate in vivo animal model experiments to further validate the dynamic changes in M1/M2 polarization. Third, this study was validated solely using the THP-1 cell model, which fails to fully replicate the complex immune microenvironment found in psoriasis patients. Consequently, future research should incorporate patient-derived primary cells or skin organoid models to conduct experiments with greater clinical relevance. Finally, although this study has revealed potential mechanisms, it lacks direct correlation analysis with patient clinical efficacy or prognostic data. Future research should integrate clinical follow-up data to explore the relationship between macrophage polarization and treatment response, thereby enhancing the translational value of these findings.

Conclusion

This study, combining single-cell transcriptomic analysis with in vitro experiments, elucidated the key mechanism of risankizumab in the treatment of psoriasis. The findings identified myeloid cells, particularly macrophages, as the main therapeutic targets. Risankizumab was shown to suppress pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages while promoting anti-inflammatory M2 polarization, thereby attenuating inflammatory responses. These results provide new evidence for understanding the therapeutic mechanism of risankizumab and establish a foundation for precision immunotherapy in psoriasis.

Acknowledgements

None

Abbreviations

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- IL

Interleukin

- APCs

Antigen-presenting cells

- Th17

Helper T cells type 17

- IFN

Interferon

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- IL

Interleukin

- PsA

Psoriatic arthritis

- NAFLD

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- IgG1

Immunoglobulin G1

- scRNA-seq

Single-cell RNA sequencing

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- UMIs

Unique molecular identifiers

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- BP

Biological process

- DAVID

Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- PMA

Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- cDCs 1

Conventional dendritic cells 1

Author contributions

All authors contributed to this present work: [YY], [LZL], [JL] and [WS] designed the study. [JYZ], [LHY] and [GG] collected data, [TT] and [JL] analyzed data. [WS], [YY], [LZL], [GG] and [JL] drafted the manuscript. [YY], [JYZ], [TT] and [WS] reviewed and revised the manuscript. The manuscript has been approved by all authors for publication.

Funding

The study was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Hubei (No. 2018CFB289), the Science Foundation of Health Commission of Hubei Province (No. WJ2019M074), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Jingmen (No. 2020YFZD022), the Project of Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Guangdong Province of China (No. 20221280) and The Science Foundation of Health Commission of Hubei Province (No. W2023Q021).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the [GSE228421] repository, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE228421].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yuan Yuan, Linzi Li—Equal contribution.

Contributor Information

Jing Liu, Email: liujing1350@gzucm.edu.cn.

Wen Sun, Email: mdsunny@yeah.net.

References

- 1.Sharma K, Kumar S. Current strategies for the management of psoriasis with potential pharmacological pathways using herbals and immuno-biologicals. Curr Mole Pharmacol. 2024;17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Zhang B, Roesner LM, Traidl S, Koeken V, Xu CJ, Werfel T, et al. Single-cell profiles reveal distinctive immune response in atopic dermatitis in contrast to psoriasis. Allergy. 2023;78(2):439–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crowley JJ, Pariser DM, Yamauchi PS. A brief guide to pustular psoriasis for primary care providers. Postgrad Med. 2021;133(3):330–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffiths CE, Barker JN. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370(9583):263–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2005;64 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):ii18–23; discussion ii4–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Chan TC, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. Interleukin 23 in the skin: role in psoriasis pathogenesis and selective interleukin 23 blockade as treatment. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2018;9(5):111–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowley JJ, Warren RB, Cather JC. Safety of selective IL-23p19 inhibitors for the treatment of psoriasis. J Euro Acad Dermatol Venereol JEADV. 2019;33(9):1676–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahil SK, Capon F, Barker JN. Update on psoriasis immunopathogenesis and targeted immunotherapy. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38(1):11–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swindell WR, Johnston A, Xing X, Voorhees JJ, Elder JT, Gudjonsson JE. Modulation of epidermal transcription circuits in psoriasis: new links between inflammation and hyperproliferation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e79253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, Ciragil P. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005(5):273–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, Mehta NN, Ogdie A, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):377–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Girolomoni G, Griffiths CE, Krueger J, Nestle FO, Nicolas JF, Prinz JC, et al. Early intervention in psoriasis and immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: a hypothesis paper. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(2):103–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Haens G, Panaccione R, Baert F, Bossuyt P, Colombel JF, Danese S, et al. Risankizumab as induction therapy for Crohn’s disease: results from the phase 3 advance and motivate induction trials. Lancet. 2022;399(10340):2015–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamiya K, Ohtsuki M. Epidemiological survey of patients with pustular psoriasis in the Japanese Society for Psoriasis Research from 2017 to 2020. J Dermatol. 2023;50(1):3–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baeten D, Østergaard M, Wei JC, Sieper J, Järvinen P, Tam LS, et al. Risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor, for ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept, dose-finding phase 2 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(9):1295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feagan BG, Panés J, Ferrante M, Kaser A, D’Haens GR, Sandborn WJ, et al. Risankizumab in patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: an open-label extension study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(10):671–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krueger JG, Ferris LK, Menter A, Wagner F, White A, Visvanathan S, et al. Anti-IL-23A mAb BI 655066 for treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: Safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and biomarker results of a single-rising-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(1):116-24.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francis L, McCluskey D, Ganier C, Jiang T, Du-Harpur X, Gabriel J, et al. Single-cell analysis of psoriasis resolution demonstrates an inflammatory fibroblast state targeted by IL-23 blockade. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shahrajabian MH, Sun W. Survey on Multi-omics, and Multi-omics Data Analysis, Integration and Application. Current Pharmaceutical Analysis. 2023;19(4):267–81.

- 20.Zulibiya A, Wen J, Yu H, Chen X, Xu L, Ma X, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals potential for endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in Tetralogy of Fallot. Congenit Heart Dis. 2023;18(6):611–25. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song Z, Yu J, Wang M, Shen W, Wang C, Lu T, et al. CHDTEPDB: transcriptome expression profile database and interactive analysis platform for Congenital Heart Disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2023;18(6):693–701. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, et al. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D607–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang Y, Yu W, Hu T, Peng H, Hu F, Yuan Y, et al. Unveiling macrophage diversity in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: identification of a distinct lipid-associated macrophage subset. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1335333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nowostawska M, Corr SA, Byrne SJ, Conroy J, Volkov Y, Gun’ko YK. Porphyrin-magnetite nanoconjugates for biological imaging. J Nanobiotechnology. 2011;9:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang W, Liu H, Zeng Z, Liang Z, Xie H, Li W, et al. KRT17 promotes T-lymphocyte infiltration through the YTHDF2-CXCL10 axis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2023;11(7):875–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiu J, Zhou T, Wang D, Hong W, Qian D, Meng X, et al. Pan-cancer analysis identifies AIMP2 as a potential biomarker for breast cancer. Curr Genom. 2023;24(5):307–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Lin S-L, Lee S-T, Huang S-E, Chang T-H, Geng Y-J, Sulistyowati E, et al. Delivery of superoxide dismutase 3 gene with baculoviruses inhibits TNF-α triggers vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and inflammation. Curr Gene Ther. 2025;25(4):546–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suárez-Fariñas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, Lowes MA, Krueger JG. Resolved psoriasis lesions retain expression of a subset of disease-related genes. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(2):391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brembilla NC, Senra L, Boehncke WH. The IL-17 family of cytokines in psoriasis: IL-17A and beyond. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Vlerken-Ysla L, Tyurina YY, Kagan VE, Gabrilovich DI. Functional states of myeloid cells in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(3):490–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Croxford AL, Karbach S, Kurschus FC, Wörtge S, Nikolaev A, Yogev N, et al. IL-6 regulates neutrophil microabscess formation in IL-17A-driven psoriasiform lesions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(3):728–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bocheńska K, Smolińska E, Moskot M, Jakóbkiewicz-Banecka J, Gabig-Cimińska M. Models in the research process of Psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017. 10.3390/ijms18122514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Li Y, Zhou L, Yuan X, Wang Y, Deng Q, et al. Nav1.8 in keratinocytes contributes to ROS-mediated inflammation in inflammatory skin diseases. Redox Biol. 2022;55:102427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, Foroughi N, Krishnamoorthy P, Raper A, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(9):1031–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schüler R, Brand A, Klebow S, Wild J, Veras FP, Ullmann E, et al. Antagonization of IL-17A attenuates skin inflammation and vascular dysfunction in mouse models of psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(3):638–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cline A, Feldman SR. Risankizumab for psoriasis. Lancet (London, England). 2018;392(10148):616–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang X, Li Y, Fu M, Xin HB. Polarizing Macrophages In Vitro. Methods Mole Biol (Clifton, NJ). 2018;1784:119–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng Y, Wang Y, Zou C, Hu B, Zhao M, Wu X. Tumor-associated macrophages facilitate the proliferation and migration of cervical cancer cells. Oncologie. 2022;24(1):147–61. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(10):889–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugaya M, Miyagaki T, Ohmatsu H, Suga H, Kai H, Kamata M, et al. Association of the numbers of CD163(+) cells in lesional skin and serum levels of soluble CD163 with disease progression of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;68(1):45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang JH, Lin YL, Wang LC, Chiang BL. M2-like macrophages polarized by Foxp3(-) treg-of-B cells ameliorate imiquimod-induced psoriasis. J Cell Mol Med. 2023;27(11):1477–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thomas SE, Barenbrug L, Hannink G, Seyger MMB, de Jong E, van den Reek J. Drug survival of IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors for psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drugs. 2024;84(5):565–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou L, Wang Y, Wan Q, Wu F, Barbon J, Dunstan R, et al. A non-clinical comparative study of IL-23 antibodies in psoriasis. MAbs. 2021;13(1):1964420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sachen KL, Hammaker D, Sarabia I, Stoveken B, Hartman J, Leppard KL, et al. Guselkumab binding to CD64(+) IL-23-producing myeloid cells enhances potency for neutralizing IL-23 signaling. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1532852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krueger JG, Eyerich K, Kuchroo VK, Ritchlin CT, Abreu MT, Elloso MM, et al. IL-23 past, present, and future: a roadmap to advancing IL-23 science and therapy. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1331217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the [GSE228421] repository, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE228421].