Abstract

Background

Salinity represents a major global constraint on crop productivity. Promoting the cultivation of tall fescue in saline environments offers not only nutritional advantages for livestock but also enhances its potential for ornamental use. In this mesocosm study, we examined the effects of paclobutrazol (PBZ) on tall fescue performance under salt stress, focusing on key physiological traits to evaluate salt tolerance.

Results

Under high salt stress, paclobutrazol application increased the total number of lateral roots by 85%, from 18.39 to 34.04, and widened their growth angle by 24%, from 24.10° to 29.88°, fundamentally enhancing topsoil exploration. This reconfigured root system supported a 65% increase in tiller number, from 16.39 to 27.11, compared to plants under salt stress alone. Physiologically, paclobutrazol treatment elevated root proline concentration by 3.2-fold and sustained the maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II (Fv/Fm) at 0.7877, a value 23% higher than the salt-stressed control (0.7052) and equivalent to non-stressed plants. Although genes associated with abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthesis were also induced, no significant increase in ABA accumulation was detected. Principal component analysis discretely distinguished the traits into root system, photosynthetic parameters, and stress indicators. NaCl induced stress-associated shifts, while PBZ-treated plants occupied an intermediate position, and showing improved root traits, photosynthesis. A strong positive correlation with control indicates PBZ partially mitigates salinity effects, maintaining functions near non-stressed levels. These synergistic improvements culminated in a 98% increase in aboveground biomass yield, producing 33.75 g per mesocosm compared to 17.06 g under salt stress alone.

Conclusion

We conclude that paclobutrazol promotes a stress-tolerant phenotype by enhancing root exploration, strengthening osmotic regulation, and stabilizing photosynthetic performance, making it a promising agronomic tool for securing forage yield in saline soils.

Keywords: Salt stress, Forage yield, Hormonal regulation, Photochemical efficiency, Plant physiology, Root system architecture, Gene expression, Tall fescue, Paclobutrazol, Salinity stress, Photosystem, Osmotic adjustment

Introduction

Soil salinity is a major abiotic stressor that significantly hinders plant growth and agricultural productivity across diverse global regions. This salinization, marked by the excessive accumulation of soluble salts in the soil, has intensified due to both natural factors and anthropogenic activities such as improper irrigation practices and deforestation [28].

The scale of the problem is substantial. According to the FAO/UNESCO [20], approximately 400 million hectares of land are affected by salinity, with suboptimal irrigation management playing a central role. Nelson and Maredia [37] further estimated that millions of hectares of arable land have become unproductive because of inadequate irrigation, underscoring the urgency of addressing soil salinization as a key threat to global food security.

In arid and semi-arid regions, salinity frequently results from high evaporation rates, which leave salts behind on the soil surface. This process is further exacerbated by excessive groundwater extraction, contributing to secondary salinization [28]. The degradation of agricultural land due to salinity not only curtails current crop output but also poses long-term challenges to the sustainability of agricultural systems.

Most cultivated crops are not inherently tolerant to saline environments, making them highly susceptible to secondary salinity and associated yield losses [28]. Salt stress disrupts several physiological processes in plants, including reduced seed germination, inhibited root development, and compromised photosynthetic efficiency. These impairments are primarily driven by osmotic stress and ion toxicity, both of which destabilize cellular homeostasis and impair overall plant vitality.

To counteract salinity stress, plants activate a suite of adaptive responses aimed at maintaining growth and survival under adverse conditions [22]. However, the mechanisms underlying these responses are complex and often species-specific. Consequently, greater emphasis is now being placed on elucidating the regulatory roles of phytohormones in stress adaptation [54, 60].

Phytohormones such as auxins, gibberellins, cytokinins, abscisic acid (ABA), and ethylene are integral to plant development, governing key processes like cell division, elongation, and differentiation [34, 52]. Among these, ABA is particularly critical in the response to salinity, where it accumulates in plant tissues to induce stomatal closure, thereby minimizing water loss and improving water use efficiency.

However, this adaptation must be finely balanced with the requirement for CO₂ uptake necessary for photosynthesis. The dynamic interplay between stomatal regulation and photosynthetic efficiency under salt stress exemplifies the complexity of hormonal signaling networks in plant adaptation [12]. Despite substantial research on classical phytohormones, relatively less attention has been paid to PBZ, a triazole-based plant growth regulator known for its growth-modulating and stress-mitigating properties [47]. PBZ primarily functions by inhibiting gibberellin biosynthesis, thereby restricting stem elongation and leaf expansion. This reduction in excessive vegetative growth is often accompanied by enhanced root development, which is crucial for water and nutrient acquisition, particularly under stress conditions.

Recent studies have highlighted the potential role of paclobutrazol (PBZ) in improving plant resilience to salt stress. For instance, PBZ treatment has been shown to enhance salinity tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum) by improving photosynthetic efficiency and antioxidant defense [41], in cucumber (Cucumis sativus) by promoting root growth and osmotic adjustment [61] , and in black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) by reducing ion toxicity and oxidative damage (Li et al., 2020). These findings suggest that PBZ may confer salt stress tolerance by modulating key physiological and biochemical pathways. However, the role of PBZ in enhancing salt stress tolerance remains underexplored. Existing evidence, though limited, supports its potential in salinity management. For example, Kishor et al. [29] demonstrated that PBZ mitigated membrane damage, increased relative water content (RWC), and improved chlorophyll retention in mango seedlings under salt stress, suggesting improved cellular integrity and photosynthetic performance. Similarly, PBZ application has been linked to elevated antioxidant enzyme activity and proline accumulation in mango [48] and cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) [33], both of which are essential components of the plant’s defense system against oxidative stress. Antioxidant enzymes play a vital role in scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS), while proline functions as an osmoprotectant, stabilizing proteins and cellular membranes under saline conditions.

Additional studies on forage legumes have further corroborated PBZ's role in mitigating ionic toxicity. For instance, in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.), PBZ application was shown to reduce sodium (Na⁺) accumulation and enhance the selectivity for potassium (K⁺) over Na⁺, thereby improving ion homeostasis under saline conditions [62]. Similarly, research on cowpea demonstrated that PBZ treatment alleviated chloride (Cl⁻) ion toxicity and improved overall plant growth and nitrogen content when subjected to salinity stress [63]. Furthermore, PBZ has been found to enhance osmotic adjustment by promoting the accumulation of compatible solutes like proline in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), leading to improved cellular water retention [64]. Collectively, these findings indicate that PBZ may facilitate plant adaptation to saline environments by improving water relations, ion homeostasis, and antioxidative defense mechanisms. Within the Poaceae family, which includes numerous economically significant forage and cereal crops, Hajihashemi et al. [21] reported that salt stress induces the accumulation of soluble carbohydrates in wheat, contributing to enhanced salt tolerance. These carbohydrates function as key osmoprotectants, aiding in the maintenance of cellular turgor pressure and facilitating osmoregulation under saline conditions. Their accumulation is therefore critical for improving stress resilience and maintaining physiological function during salinity stress.

Tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea), a cool-season perennial grass belonging to the Poaceae family, is widely utilized for turf, forage, and ornamental purposes. As a moderately salt-tolerant turfgrass species, it holds promise for use in saline-affected agricultural and landscape systems. However, high soil salinity remains a limiting factor for its optimal growth, establishment, and broader application. Owing to its high genetic heterogeneity, tall fescue populations exhibit substantial intraspecific variation in salt tolerance, providing opportunities for trait improvement through physiological and genetic studies.

Previous research has explored various mechanisms underlying salt tolerance in tall fescue and other Poaceae members, particularly focusing on ion homeostasis, osmotic adjustment, and stress-responsive physiological pathways. Nonetheless, to date, no comprehensive study has directly examined the role of PBZ in enhancing salt tolerance specifically in tall fescue, and only limited data exist for other members of the Poaceae family. Given PBZ’s unique ability to regulate plant growth and enhance abiotic stress resilience, its application in the context of salinity stress warrants further investigation.

Therefore, the present study aims to evaluate the physiological and biochemical effects of PBZ on tall fescue under salt stress. By elucidating the underlying mechanisms through which PBZ enhances salt tolerance, this research contributes novel insights into turfgrass stress physiology and supports the development of more resilient tall fescue cultivars suitable for saline environments.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

This study utilized the salt-tolerant tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea) cultivar ‘Puregold’, which was previously identified through marker-assisted selection techniques [4]. Plant materials were sourced from the Germplasm Conservation Center of the Wuhan Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences. For the initial establishment phase, a single complete tiller was planted per pot in a plastic basin measuring 13 cm in diameter and 11 cm in depth. The pots were filled with a homogeneous 1:1 (v/v) mixture of sand and soil, selected for its optimal drainage and aeration properties to promote healthy root development. The plants were grown under controlled greenhouse conditions with day/night temperatures maintained at 25 °C and 20 °C, respectively, a 14-h photoperiod providing a light intensity between 1000 and 1500 μmol photons m⁻2 s⁻1, and an average relative humidity of approximately 76%. Plants were irrigated daily to maintain adequate hydration and fertilized weekly with half-strength Hoagland’s nutrient solution. The Hoagland’s solution consisted of macronutrients (KNO₃ 6.0 mM, Ca(NO₃)₂·4H₂O 4.0 mM, NH₄H₂PO₄ 1.0 mM, MgSO₄·7H₂O 2.0 mM), micronutrients (H₃BO₃ 46.3 µM, MnCl₂·4H₂O 9.1 µM, ZnSO₄·7H₂O 0.76 µM, CuSO₄·5H₂O 0.32 µM, (NH₄)₆Mo₇O₂₄·4H₂O 0.11 µM), and Fe-EDTA 100 µM, adjusted to pH 5.8 with an electrical conductivity of about 1.8 dS·m⁻1. The canopy height was maintained at approximately 7 cm by regular mowing to ensure uniform growth and minimize competition.

After an 8-week growth period, uniformly developed tillers were carefully selected and transplanted into smaller plastic pots (7 cm in diameter and 9 cm deep) filled with coarse silica aggregate to provide stable anchorage for the subsequent hydroponic phase. Each pot was fitted with a porous plastic mesh at the base to allow roots to extend freely. The pots were then suspended in rectangular plastic basins containing half-strength Hoagland’s solution, which was replenished twice per week and fully refreshed once a week to ensure consistent nutrient availability. Following a 21-day acclimatization period in this hydroponic system, salt stress treatments were initiated. The experimental groups included a control receiving only half-strength Hoagland’s solution, a group treated with 200 mM NaCl, and a group treated with a combination of 200 mM NaCl and 20 µg of paclobutrazol (PBZ).

Sampling and quantification of physiological parameters

Physiological measurements and sampling were conducted seven days after the imposition of the stress treatments. Chlorophyll fluorescence transients were measured on dark-adapted leaves using a pulse-amplitude modulation fluorometer (PAM-2500, Heinz Walz GmbH). The resulting OJIP curves were analyzed using the JIP test methodology to convert the primary fluorescence data into biophysical parameters that describe the energy flux within the photosynthetic apparatus [25]. For biochemical analyses, newly formed roots and leaves were randomly harvested from each basin. Tissues were thoroughly rinsed with running double-distilled water, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent analysis.

The proline content in leaf and root tissues was determined according to the method of Ábrahám et al. [1], which involves extraction with sulfosalicylic acid and reaction with ninhydrin, with the absorbance measured at 520 nm. Soluble sugar concentration was quantified following the protocol of Leach and Braun [65], where sucrose concentration is calculated from the difference in reducing sugars between invertase-treated and control solutions. To assess ion accumulation, potassium (K⁺) and sodium (Na⁺) concentrations were determined from aqueous extracts of dried leaf material using flame photometry.

Malondialdehyde (MDA) content, an indicator of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress, was quantified according to the method of Heath and Packer [53] with minor modifications. Briefly, 0.5–1 g of plant tissue was homogenized in 5–10 mL of ice-cold 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and 1 mL of the supernatant was combined with 2 mL of 1% thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and 2 mL of 10% TCA. The mixture was incubated in a boiling water bath for 15–30 min, cooled, and centrifuged again. Absorbance was measured at 532 nm, and MDA concentration was expressed as nanomoles per gram of fresh weight. The MDA content was calculated using the adjusted absorbance and an extinction coefficient of 155 mM⁻1 cm⁻1 based on the following formula:

|

where A₅₃₂ and A₆₀₀ are the absorbances at 532 and 600 nm, respectively, V_t is the total volume of the extract (mL), ε is the extinction coefficient (155 mM⁻1 cm⁻1), l is the cuvette path length (cm), and FW is the fresh weight of the sample (g).

Membrane integrity was further assessed by measuring electrolyte leakage (EL). Fresh leaf segments were incubated in deionized water, and their conductivity was measured before and after autoclaving to calculate the relative EL percentage [18]. Root system architecture was analyzed semi-automatically from high-resolution 2D images using the EZ-Rhizo system, which enables the detection and quantification of architectural traits [5].

Endogenous abscisic acid (ABA) levels were measured according to the method of Liu et al. [31] with minor modifications. Frozen tissue was extracted, purified, and quantified using a PhytoDetect ELISA kit. For gene expression analysis, total RNA was extracted from clean tissue samples and reverse-transcribed into cDNA. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed for target genes (FaP5CS, FaGluTR, FaSUS1, FaHKT1, FaABA1, and FaLOX1), with elongation factor 1 (EF1) serving as the internal reference gene. Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2⁻ΔΔCt method.

Experimental design and statistical analysis

The experiment was conducted using a fully crossed two-factor factorial design with six replications. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate differences in phenotypic responses among the three treatment groups. All statistical analyses were conducted in RStudio using appropriate statistical packages. The OJIP fluorescence transients were visualized using OriginPro 2022.

Results

The two-way ANOVA revealed significant sources of variation in tall fescue performance (Table 1). Salinity accounted for the largest proportion of variance, with a sum of squares of 8750, representing 36.8% of the total variation, and exerted a highly significant effect on plant growth (F = 95.4, df = 1,93, p < 0.001). Application of paclobutrazol contributed a smaller but significant share of the variance (SS = 405; 1.7% of total; F = 4.42, df = 1,93, p = 0.038). The interaction between salinity and paclobutrazol was also highly significant (SS = 6120; 25.7% of total; F = 66.7, df = 1,93, p < 0.001), indicating that the effect of paclobutrazol was strongly dependent on salinity level. The residual variance (SS = 8520) accounted for 35.8% of the total. These results demonstrate that while salinity stress had the strongest individual effect on tall fescue, paclobutrazol significantly modified the plant’s response, enhancing tolerance under saline conditions.

Table 1.

Summary of analysis of variance

| Source of variation | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salinity | 8750 | 1 | 8750 | 95.4 | < 0.001 |

| Paclobutrazol | 405 | 1 | 405 | 4.42 | 0.038 |

| Salinity x Paclobutrazol | 6120 | 1 | 6120 | 66.7 | < 0.001 |

| Within groups (Error) | 8520 | 93 | 91.6 | ||

| Total | 23,795 | 95 |

Effects of PBZ on root system architecture

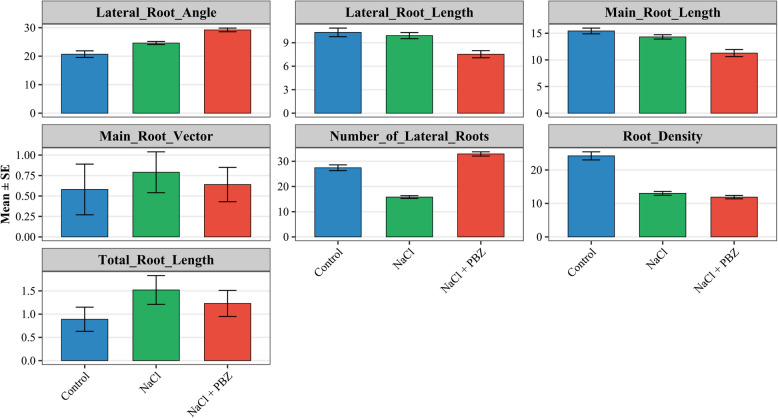

The treatments induced pronounced morphological changes in the root systems of the three groups. Root density was significantly affected by treatment conditions. The control group exhibited the highest root density, averaging 25.53, while the NaCl + PBZ treatment led to a substantial reduction to 10.58. These results suggest that the combined application of NaCl and PBZ may inhibit the formation of a densely packed root system. In contrast, the NaCl-only treatment yielded an intermediate root density of 13.57.

Interestingly, the number of lateral roots was highest in the NaCl + PBZ group, with a mean value of 34.04, indicating that although overall root density decreased, lateral root proliferation was enhanced. Total root length, defined as the combined length of the primary and all lateral roots, did not show significant differences across treatments.

Analysis of lateral root angle, which quantifies the deviation of lateral roots from the main root axis, revealed that the NaCl + PBZ treatment resulted in a more horizontal growth orientation, with an average angle of 29.88°. In comparison, the control and NaCl treatments showed lower angles of 18.79° and 24.10°, respectively. Regarding the main root vector—a measure of directional root growth—the NaCl treatment produced the highest value (0.78), suggesting a more vertical orientation, followed by the NaCl + PBZ group (0.67) and the control group (0.55).

The longest root tip (LRT) was observed in the control treatment at 11.01 cm, while the shortest was recorded in the NaCl + PBZ group at 7.87 cm. These findings indicate that the addition of PBZ under saline conditions alters root system architecture by promoting lateral expansion while restricting vertical root elongation, leading to a more exploratory root growth pattern (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Bar plots illustrating root system architecture traits of tall fescue under different treatment conditions. Main root length and lateral root length are expressed in centimeters, while total root length is presented in meters. The lateral root angle represents the degree of deviation from the main root axis

The analysis of final biomass and tiller count revealed a profound mitigating effect of paclobutrazol (PBZ) on salt-induced growth suppression. Salinity stress alone (NaCl treatment) had a severely negative impact, reducing forage dry matter production by 40.6% and tiller number by 42.9% compared to the unstressed control group. In striking contrast, the application of PBZ under saline conditions (NaCl + PBZ treatment) not only fully alleviated this damage but actually enhanced growth beyond control levels. Plants in this treatment produced 17.6% more dry matter and 5.6% more tillers than the non-stressed control. Ultimately, when compared to the salt-stressed plants, those receiving the combined NaCl + PBZ treatment yielded 97.8% more dry matter and supported 65.4% more tillers, demonstrating a near-complete rescue of phenotypic performance (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Representative photograph showing the morphological responses of tall fescue under different treatments. The combined bar and line plot illustrates the effects of control, NaCl + PBZ, and NaCl treatments on forage dry matter and tiller number in tall fescue

Transcriptional regulation of compatible osmolytes

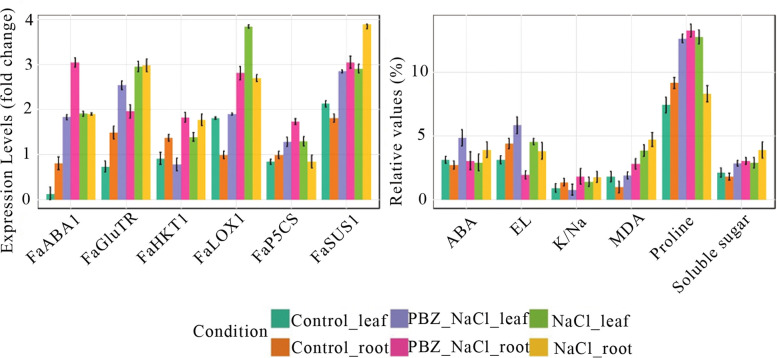

The results of the transcriptional analysis revealed distinct gene expression patterns and their corresponding phenotypic outcomes, underscoring the complex interplay between genetic regulation and stress responses. Notably, FaSUS1 exhibited the highest expression levels, particularly in leaf tissues under the PBZ + NaCl treatment, suggesting its pivotal role in sugar metabolism and stress adaptation. Although soluble sugar content remained relatively stable across treatments, elevated FaSUS1 expression was associated with increased sugar accumulation in the leaves compared to the control. Other genes, such as FaGluTR and FaHKT1, showed pronounced expression variability, especially in root tissues, indicating their involvement in osmotic regulation and ion homeostasis. The observed variation in the K⁺/Na⁺ ratio reflected significant ionic balance adjustments under the PBZ + NaCl treatment. For instance, in root tissues, the K⁺/Na⁺ ratio reached its highest value under PBZ + NaCl treatment, whereas no significant changes were observed in leaf tissues.

FaGluTR, known to influence membrane permeability to electrolytes, typically shows increased expression under stress conditions. In the present study, its expression was suppressed by PBZ + NaCl treatment, coinciding with a marked reduction in electrolyte leakage (EL) in roots. In contrast, EL was significantly elevated in leaves under NaCl treatment alone, indicating salt-induced cellular damage. Furthermore, FaP5CS, a key gene in proline biosynthesis, was significantly upregulated in root tissues under PBZ + NaCl treatment, while no differential expression was observed in leaves. This transcriptional pattern was consistent with biochemical data, showing the highest proline concentrations in roots exposed to PBZ + NaCl.

Collectively, these results highlight the complex gene–environment interactions underlying physiological responses to combined PBZ and NaCl stress in tall fescue (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Bar plots illustrating the expression levels of selected genes and their corresponding phenotypic traits in the leaves and roots of tall fescue under control, PBZ + NaCl, and NaCl treatments. Error bars represent standard deviations (SD)

Chlorophyll a fluorescence

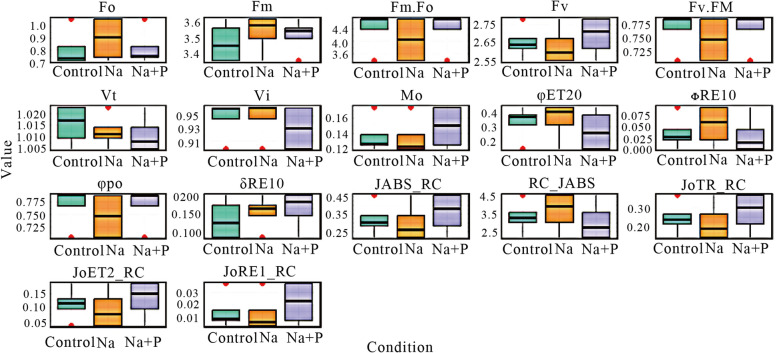

The control treatment exhibited the highest maximum fluorescence intensity (Fm), reaching approximately 1800 arbitrary units (a.u.), indicative of optimal photosystem II (PSII) efficiency and robust electron transport capacity. In contrast, the NaCl treatment resulted in a markedly reduced Fm, with a peak value below 1000 a.u., reflecting impaired PSII function and disrupted electron transport likely caused by sodium-induced stress. The NaCl + PBZ treatment showed intermediate fluorescence levels, with peak values slightly lower than those of the control but significantly higher than those of the NaCl group. These findings suggest that PBZ application partially alleviates the detrimental effects of NaCl stress, contributing to improved PSII activity and electron transport, although not fully restoring photosynthetic performance to control levels (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

OJIP chlorophyll fluorescence transients of tall fescue under control, NaCl, and NaCl + PBZ treatments

The analysis of chlorophyll a fluorescence provided further evidence of the protective role of paclobutrazol on the photosynthetic apparatus under salt stress. The ratio of maximum to initial fluorescence (Fm/F₀), a key indicator of PSII health, declined sharply under salinity stress, falling by 28.0% from 4.7145 in the control to 3.3932 in the NaCl-treated plants. This significant reduction points to substantial damage or inefficiency within PSII. However, this decline was almost entirely prevented by PBZ application; the Fm/F₀ ratio in the NaCl + PBZ treatment (4.7110) was statistically equivalent to the control, representing a 38.9% recovery compared to the salt-stressed group.

This trend was corroborated by the variable fluorescence (Fv) data, which reflect the quantum yield of photochemistry. The Fv value was lowest in the NaCl group (2.5462), representing a 3.4% decrease from the control value (2.6366). Conversely, plants treated with NaCl + PBZ exhibited the highest Fv value (2.7822), which was 5.5% higher than the control and 9.3% higher than the NaCl-only group. This enhancement suggests that PBZ not only preserves PSII integrity under stress but may actually improve the functional capacity for light energy capture and conversion, supporting the overall maintenance of photosynthetic performance observed in the NaCl + PBZ treatment.

The control and NaCl + PBZ treatments maintained nearly identical, optimal Fv/Fm values of 0.7878 and 0.7877, respectively. In stark contrast, salinity stress alone caused a severe 10.5% reduction in the Fv/Fm ratio, which declined significantly to 0.7052. This substantial decrease is a definitive indicator of photoinhibition, reflecting a loss of functional PSII reaction centers. The fact that the Fv/Fm ratio in the NaCl + PBZ treatment was maintained at the same level as the healthy control provides strong evidence that PBZ application effectively attenuates salt-induced photoinhibition, thereby preserving the photosynthetic capacity of the plant under stress (Fig. 4).

Quantum Yield, Electron Transport and Reaction Center Behavior

Among the additional PSII parameters, the maximum quantum yield of PSII photochemistry (φPo) exhibited a consistent trend between the control and NaCl + PBZ treatments, while a marked reduction was observed under NaCl treatment. The quantum yield of electron transport (φET20), reflecting the efficiency of electron movement beyond QA⁻, was significantly lower in the NaCl + PBZ treatment (0.1391) compared to the control (0.3729) and NaCl (0.4459) treatments.

The parameter ΨET20, indicative of the probability that a trapped exciton moves an electron into the electron transport chain beyond QA⁻, showed higher energy transfer efficiency in the NaCl + PBZ treatment. Additionally, δRE10, which reflects the efficiency of electron transfer from intersystem carriers to PSI end acceptors, was substantially elevated under the NaCl + PBZ treatment, suggesting increased accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in response to stress. This finding implies that PBZ may influence the cellular redox balance under saline conditions.

Furthermore, the JABS/RC value, representing the amount of light energy absorbed per active reaction center, was significantly higher in the NaCl + PBZ treatment (0.4579) than in the control (0.3031) and NaCl (0.2181) groups. This suggests that PBZ enhances light-harvesting efficiency per reaction center under salt stress, which may contribute to maintaining photosynthetic performance despite adverse environmental conditions (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Boxplots showing the effects of salinity (Na) and paclobutrazol (P) on chlorophyll a fluorescence parameter of tall fescue compared with the control. Parameters include minimum fluorescence (Fo), maximum fluorescence (Fm), variable fluorescence (Fv), maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm), relative variable fluorescence at time t (Vt) and at the J-step (Vj), approximated initial slope of the fluorescence rise (Mo), quantum yield of electron transport (φET20, φRE10, φPo, δRE10), absorption flux per reaction center (JABS_RC), number of active reaction centers per absorption (RC_JABS), trapped energy flux per reaction center (JoTR_RC), electron transport flux per reaction center (JoET2_RC), and electron flux reducing end acceptors at PSI per reaction center (JoRE1_RC)

Principal component analysis

A principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted to integrate multivariate traits, including root architecture, photosynthetic performance, and stress physiology, and to evaluate the phenotypic responses of plants under control, salinity-stressed (NaCl), and salinity-stressed with paclobutrazol (NaCl + PBZ) conditions.

The first two principal components (PCs) accounted for a substantial portion of the total variance, with PC1 explaining 46.6% and PC2 explaining 22.6%, cumulatively representing 69.2% of the phenotypic variation. The biplot visualization demonstrated clear separation among the three treatment groups, each forming distinct clusters with 95% confidence ellipses (Fig. 6). This segregation indicates that the treatments induced significantly different multivariate phenotypic profiles.

Fig. 6.

Scatter plot matrix illustrating the correlations among physiological parameters across different treatment regime (control, NaCl, and NaCl + PBZ)

The control plants were associated with traits indicative of robust growth, such as greater root density and a higher number of lateral roots. In contrast, plants subjected to NaCl stress were strongly separated from the control along PC1. This separation was driven by their association with elevated stress markers, specifically increased malondialdehyde (MDA) content and electrolyte leakage (EL), alongside a pronounced reduction in dry matter yield.

Notably, the phenotypic profile of the NaCl + PBZ treatment group was intermediate between the control and NaCl-stressed plants along the primary separating axis (PC1). This intermediate positioning suggests that the application of PBZ partially mitigated the salinity-induced shift in the phenotype, resulting in a trait ensemble more like the non-stressed control. Specifically, the NaCl + PBZ group was associated with a higher dry matter yield compared to the NaCl group, indicating that PBZ alleviated the detrimental effects of salinity on productivity. The variable loadings illustrate the trade-offs between oxidative stress, photosynthetic function, and root architecture, with PBZ modulating these relationships to enhance stress tolerance (Fig. 6).

Discussion

The escalating challenge of soil salinity necessitates the development of effective mitigation strategies to safeguard agricultural productivity. This study provides compelling evidence that the triazole compound paclobutrazol (PBZ) confers significant salinity tolerance in tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.). The findings move beyond the simplistic view of PBZ as merely a growth retardant and instead reveal its role as a multifaceted priming agent that orchestrates a sophisticated defense network. This enhanced tolerance is fundamentally rooted in PBZ's ability to potentiate osmotic adjustment through the coordinated accumulation of key osmolytes and to exert a profound protective effect on the photosynthetic apparatus, likely mediated through the regulation of critical stress-responsive genes.

The primary insult of salinity stress is osmotic, immediately imposing a water deficit that mimics physiological drought. Plants respond by initiating osmotic adjustment (OA), a process crucial for maintaining turgor pressure, driving water uptake, and protecting cellular structures. Our data demonstrate that PBZ application under salinity stress acts as a powerful stimulant for this essential process. The most striking observation was the significant accumulation of the amino acid proline in plants treated with NaCl + PBZ. Proline is a versatile osmoprotectant renowned for its roles in stabilizing proteins and membranes, scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS), and acting as a nitrogen and carbon reservoir for post-stress recovery [58]. This surge in proline content was not a passive consequence of stress but an active physiological response, strongly correlated with the transcriptional upregulation of P5CS. This gene encodes the key rate-limiting enzyme in proline biosynthesis, and its enhanced expression provides a clear molecular mechanism for the observed metabolic shift. By promoting the transcription of P5CS, PBZ effectively channels glutamate into the proline biosynthesis pathway, ensuring a rapid and robust osmotic response that is crucial for mitigating the initial osmotic shock of salinity [55].

Concurrently, PBZ treatment significantly elevated the levels of soluble sugars, including sucrose, glucose, and fructose. These compounds serve dual roles as both compatible osmolytes and readily available energy sources. The observed upregulation of sucrose synthase (SUS) genes in the NaCl + PBZ treatment group offers a genetic basis for this phenomenon. SUS is pivotal in sucrose metabolism, governing its breakdown to provide substrates for glycolysis and the synthesis of other metabolites. The enhanced expression of SUS suggests that PBZ redirects carbon partitioning towards the accumulation of these vital osmolytes. This process ensures a steady supply of carbon skeletons not only for maintaining osmotic balance but also for fueling the heightened energy demands of the plant's defense systems under prolonged stress [59]. Therefore, the PBZ-induced OA is a multi-pronged strategy, leveraging both nitrogen (proline) and carbon (sugars) metabolism to combat cellular dehydration.

However, osmotic stress is swiftly followed by ionic stress, characterized by the accumulation of toxic sodium (Na⁺) ions and the disruption of essential potassium (K⁺) homeostasis. A critical indicator of a plant's ability to withstand ionic stress is the maintenance of a high K⁺/Na⁺ ratio. Our results show that PBZ treatment was highly effective in sustaining this ratio under saline conditions. This improvement suggests that PBZ enhances the plant's capacity for selective K⁺ uptake and/or sequestration while limiting Na⁺ influx or facilitating its vacuolar compartmentalization. This physiological response is almost certainly underpinned by the regulated activity of specific ion transporters. For instance, the operation of plasma membrane H⁺-ATPases, which generate the proton motive force for Na⁺ exclusion via SOS1 antiporters, and vacuolar NHX exchangers, which sequester Na⁺ into the vacuole, are known to be influenced by hormonal and signaling cascades [54, 60]. Furthermore, the expression of high-affinity potassium transporters (HAK/KUP/KT) is crucial for K⁺ acquisition under salt stress. We postulate that PBZ, potentially through its interaction with hormonal pathways (particularly gibberellin and abscisic acid cross-talk), modulates the expression or activity of these key transporters, thereby fortifying ionic homeostasis—a cornerstone of salinity tolerance.

The most visually apparent and physiologically critical outcome of this coordinated effort to maintain water and ionic balance was the preservation of photosynthetic function. Chlorophyll a fluorescence analysis provides a powerful, non-invasive window into the performance and health of photosystem II (PSII). The dramatic decline in the Fv/Fm ratio under salt stress alone is a classic signature of photoinhibition, indicating a loss of functional PSII reaction centers. The concomitant rise in F₀ fluorescence further suggests physical disassembly of light-harvesting complexes (LHCII) from the PSII core, a common stress response that, while potentially photoprotective, severely compromises light-use efficiency [56]. Remarkably, PBZ application completely prevented these deleterious changes, maintaining Fv/Fm and F₀ values statistically indistinguishable from those of the unstressed control. This finding powerfully indicates that PBZ acts to stabilize the supra-molecular structure of PSII and its associated antennae, protecting the integrity of the thylakoid membranes against salt-induced damage.

A more granular analysis of the OJIP transient offers deeper insights into the specific sites of protection within the photosynthetic electron transport chain (ETC). The NaCl-induced suppression of the J and I steps indicates a severe bottleneck in electron flow, likely at the level of the plastoquinone (PQ) pool reduction and the subsequent re-oxidation by the cytochrome b₆f complex. The significantly reduced P peak further confirms a widespread dysfunction across the ETC, limiting the overall capacity for linear electron flow. The OJIP curve for the NaCl + PBZ treatment, however, closely mirrored that of the control, demonstrating that PBZ effectively alleviates these bottlenecks and preserves the functional integrity of the entire ETC from PSII to PSI.

Interrogation of the derived JIP-test parameters reveals a nuanced photoprotective strategy employed by PBZ-treated plants. While the quantum yield of primary photochemistry (φPo) was maintained—confirming that energy absorption and trapping by open PSII centers remained efficient, the quantum yield of electron transport (φET20) was notably lower in the NaCl + PBZ group compared to the control. This may seem counterintuitive but is likely a hallmark of an adaptive, protective response. By slightly downregulating the electron flux from QA⁻ to the PQ pool, PBZ may prevent the over-reduction of the ETC, a primary cause of ROS generation under stress conditions [57]. This controlled slowdown is a strategic trade-off to avoid catastrophic oxidative damage. This notion is supported by the significant increase in the performance index (PIabs), a holistic parameter that integrates the main functional steps of photosynthesis. The higher PIabs in the NaCl + PBZ group indicates that despite a potentially slower electron flow, the overall functionality and coordination of the photosynthetic apparatus are vastly superior to the salt-stressed plants without PBZ.

Conclusion

Based on the physiological and molecular evidence presented in this study, we conclude that the application of paclobutrazol (PBZ) confers a significant improvement in salt tolerance in the tall fescue cultivar ‘Puregold’. This enhancement is not achieved through ABA-mediated signaling but is primarily driven by two key mechanisms: the restoration of ionic balance by increasing the K⁺/Na⁺ ratio and the alleviation of oxidative stress through the reduction of lipid peroxidation and membrane damage. The upregulation of genes related to proline synthesis (FaP5CS) and oxidative protection (FaGluTR) further supports the role of PBZ in enhancing osmotic adjustment and scavenging reactive oxygen species. Critically, this physiological mitigation translated to improved plant growth, as evidenced by a significant increase in dry matter yield under salt stress conditions in PBZ-treated plants.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Erick Amombo from Mohammed VI Polytechnic University, Morocco, for his assistance in revising the language of the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

SF and FW conceived and designed the research, supervised the project, and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. XS, GL, and JH performed the experiments and contributed to data collection. FW was responsible for literature review and reference organization. ZM conducted the statistical analyses and generated the figures. SF and ZM jointly interpreted the data. YZ provided funding acquisition, project administration, and general support. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and approved the final version for publication.

Funding

This research was funded by Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China for International Cooperation, grant number 42320104006.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ábrahám E, Hourton-Cabassa C, Erdei L, Szabados L. Methods for determination of proline in plants. In: Plant Stress Tolerance: Methods and Protocols. Humana Press; 2010. p. 317–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Abraham SS, Jaleel CA, Chang Xing Z, Somasundaram R, Azooz MM, Manivannan P, et al. Regulation of growth and metabolism by paclobutrazol and ABA in Sesamum indicum L. under drought conditions. J Mol Sci. 2008;3(2):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allakhverdiev SI, Sakamoto A, Nishiyama Y, Inaba M, Murata N. Ionic and osmotic effects of NaCl-induced inactivation of photosystems I and II in Synechococcus sp. Plant Physiol. 2000;123(3):1047–56. 10.1104/pp.123.3.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amombo E, Li X, Wang G. Screening of diverse tall fescue population for salinity tolerance based on SSR marker-physiological trait association. Euphytica. 2018;214:220. 10.1007/s10681-018-2281-5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armengaud P, Zambaux K, Hills A, Sulpice R, Pattison RJ, Blatt MR, et al. Ez-rhizo: integrated software for the fast and accurate measurement of root system architecture. Plant J. 2009;57(5):945–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asamoah TEO, Atkinson D. The effects of (2RS, 3RS)-1-(4-chlorophenyl)-4,4 dimethyl-2-(1H–1,2,4 triazol-1-yl) pentan-3-ol (paclobutrazol: PP333) and root pruning on the growth, water use and response to drought of Colt cherry rootstocks. Plant Growth Regul. 1985;3:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balasubramaniam T, Shen G, Esmaeili N, Zhang H. Plants’ response mechanisms to salinity stress. Plants. 2023;12(12):2253. 10.3390/plants12122253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baninasab B. Amelioration of chilling stress by paclobutrazol in watermelon seedlings. Sci Hortic. 2009;121(2):144–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baninasab B, Ghobadi C. Influence of paclobutrazol and application methods on high-temperature stress injury in cucumber seedlings. J Plant Growth Regul. 2011;30:213–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banon S, Fernandez JA, Ochoa J, Sanchez-Blanco MJ. Paclobutrazol as an aid to reduce some effects of salt stress in oleander plants. Eur J Hortic Sci. 2005;70:43–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banon S, Ochoa J, Martinez JA, Fernandez JA, Franco JA, Sanchez-Blanco MJ, et al. Paclobutrazol as an aid to reducing the effects of salt stress in Rhamnus alaternus plants. Acta Hortic. 2003;609:263–8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bharath P, Gahir S, Raghavendra AS. Abscisic acid-induced stomatal closure: an important component of plant defense against abiotic and biotic stress. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:615114. 10.3389/fpls.2021.615114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Björkman O, Demmig B. Photon yield of O2 evolution and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics at 77 K among vascular plants of diverse origins. Planta. 1987;170(4):489–504. 10.1007/BF00402983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brini F, Masmoudi K. Ion transporters and abiotic stress tolerance in plants. ISRN Molecular Biology. 2012;2012:927436. 10.5402/2012/927436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen H, Cheng Z, Ma X, Wu H, Liu Y, Zhou K, et al. A knockdown mutation of YELLOW-GREEN LEAF2 blocks chlorophyll biosynthesis in rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2013;32(12):1855–67. 10.1007/s00299-013-1498-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cinq-Mars M, Samson G. Down-regulation of photosynthetic electron transport and decline in CO2 assimilation under low frequencies of pulsed lights. Plants. 2021;10(10):2033. 10.3390/plants10102033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demmig-Adams B, Adams WW III. Photoprotection in an ecological context: the remarkable complexity of thermal energy dissipation. New Phytol. 2006;172(1):11–21. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Dewir YH, Alsadon A. Effects of nutrient solution electrical conductivity on the leaf gas exchange, biochemical stress markers, growth, stigma yield, and daughter corm yield of saffron in a plant factory. Horticulturae. 2022;8(8):673. [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Khashab Abou AM, El-Sammak AF, Elaidy AA, Salama MI. Paclobutrazol reduces some negative effects of salt stress in peach. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1997;122:43–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The salt of the earth: Hazardous for food production. 2002 [cited 2024 May 15]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/worldfoodsummit/english/newsroom/focus/focus1.htm.

- 21.Hajihashemi S, Ehsanpour AA. Influence of exogenously applied paclobutrazol on some physiological traits and growth of Stevia rebaudiana under in vitro drought stress. Biol. 2013;68:414–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasanuzzaman M, Fujita M. Plant responses and tolerance to salt stress: physiological and molecular interventions. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):4810. 10.3390/ijms23094810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasegawa PM, Bressan RA, Zhu JK, Bohnert HJ. Plant cellular and molecular responses to high salinity. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2000;51:463–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Havaux M. Rapid photosynthetic adaptation to heat stress triggered in potato leaves by moderately elevated temperatures. Plant Cell Environ. 1993;16(4):461–7. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1993.tb00893.x. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayat S, Hasan SA, Yusuf M, Hayat Q, Ahmad A. Effect of 28-homobrassinolide on photosynthesis, fluorescence, and antioxidant system in the presence or absence of salinity and temperature in Vigna radiata. Environ Exp Bot. 2010;69(2):105–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hnilickova H, Kraus K, Vachova P, Hnilicka F. Salinity stress affects photosynthesis, malondialdehyde formation, and proline content in Portulaca oleracea L. Plants. 2021;10(5):845. 10.3390/plants10050845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hohmann S. Osmotic stress signaling and osmoadaptation in yeasts. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66(2):300–72. 10.1128/MMBR.66.2.300-372.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosseini P, Bailey RT. Investigating the controlling factors on salinity in soil, groundwater, and river water in a semiarid agricultural watershed using SWAT-salt. Sci Total Environ. 2022;810:152293. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kishor A, Srivastav M, Dubey A, Sharma R. Paclobutrazol minimizes the effects of salt stress in mango (Mangifera indica L.). J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2009;84(4):459–65. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar V, Shriram V, Kavi Kishor PB, Jawali N, Shitole MG. Enhanced proline accumulation and salt stress tolerance of transgenic indica rice by over-expressing P5CSF129A gene. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2010;4:37–48. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu N, Ding Y, Fromm M, Avramova Z. Endogenous ABA extraction and measurement from Arabidopsis leaves. Bio-protocol. 2014;4(19):e1257. 10.21769/bioprotoc.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lutts S, Majerus V, Kinet JM. NaCl effects on proline metabolism in rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings. Physiol Plant. 2002;105(3):450–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manivarman P, Jaleel CA, Kishorekumar A, Sankar B, Somasundaram R, Panneerselvam R. Protection of Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. plants under salt stress caused by paclobutrazol. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2008;61(2):315–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mukherjee A, Gaurav AK, Singh S, Yadav S, Bhowmick S, Abeysinghe S, et al. The bioactive potential of phytohormones: a review. Biotechnol Rep (Amst). 2022;35:e00748. 10.1016/j.btre.2022.e00748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Munns R, Rawson HM. Effect of salinity on salt accumulation and reproductive development in the apical meristem of wheat and barley. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1999;26(5):459–64. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murchie EH, Lawson T. Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis: a guide to good practice and understanding some new applications. J Exp Bot. 2013;64(13):3983–98. 10.1093/jxb/ert208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson M, Mareida M. Environmental impacts of the CGIAR: An assessment. Historical Archive of CGIAR (1959–2009). 2001.

- 38.Ozturk M, Turkyilmaz Unal B, García-Caparrós P, Khursheed A, Gul A, Hasanuzzaman M. Osmoregulation and its actions during the drought stress in plants. Physiol Plant. 2021;172(2):1321–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patterson JH, Newbigin E, Tester M, Bacic A, Roessner U. Metabolic responses to salt stress of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars, Sahara and Clipper, which differ in salinity tolerance. J Exp Bot. 2009;60(14):4089–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pinheiro C, Chaves MM. Photosynthesis and drought: can we make metabolic connections from available data? J Exp Bot. 2011;62(3):869–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rahimi R, Paknejad F, Sadeghishoae M, Ilkaee MN, Rezaei M. Combined effects of paclobutrazol application and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPRs) inoculation on physiological parameters of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under drought stress. Cereal Res Commun. 2024;52(3):1015–29. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rai AN, Penna S. Molecular evolution of plant P5CS gene involved in proline biosynthesis. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(11):6429–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salam U, Ullah S, Tang ZH, Elateeq AA, Khan Y, Khan J, et al. Plant metabolomics: an overview of the role of primary and secondary metabolites against different environmental stress factors. Life. 2023;13(3):706. 10.3390/life13030706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shu S, Guo SR, Sun J, Yuan LY. Effects of salt stress on the structure and function of the photosynthetic apparatus in Cucumis sativus and its protection by exogenous putrescine. Physiol Plant. 2012;146(3):285–96. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2012.01623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silva-Ortega CO, Ochoa-Alfaro AE, Reyes-Agüero JA, Aguado-Santacruz GA, Jiménez-Bremont JF. Salt stress increases the expression of P5CS gene and induces proline accumulation in cactus pear. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2008;46(1):82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh M, Kumar J, Singh S, Singh VP, Prasad SM. Roles of osmoprotectants in improving salinity and drought tolerance in plants: a review. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2015;14(3):407–26. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soumya PR, Kumar P, Pal M. Paclobutrazol: a novel plant growth regulator and multistress ameliorant. Indian J Plant Physiol. 2017;22(3):267. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Srivastava M, Kishor A, Dahuja A, Sharma RR. Effects of paclobutrazol and salinity on ion leakage, proline content, and activities of antioxidant enzymes in mango (Mangifera indica L.). Sci Hortic. 2010;125(4):785–8. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stirbet A, Govindjee. On the relation between the Kautsky effect (chlorophyll a fluorescence induction) and Photosystem II: Basics and applications of the OJIP fluorescence transient. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2011;104(1–2):236–57. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang DH, Webster J, Adam Z, Lindahl M, Andersson B. Induction of acclimative proteolysis of the light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b protein of photosystem II in response to elevated light intensities. Plant Physiol. 1998;118(3):827–34. 10.1104/pp.118.3.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang C, Zhang ZS, Gao HY, Fan XL, Liu MJ, Li XD. The mechanism by which NaCl treatment alleviates PSI photoinhibition under chilling-light treatment. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2014;140:286–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mukherjee A, Gaurav AK, Singh S, Yadav S, Bhowmick S, Abeysinghe S, et al. The bioactive potential of phytohormones: a review. Biotechnol Rep (Amst). 2022;35:e00748. 10.1016/j.btre.2022.e00748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heath RL, Packer L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts. I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1968;125(1):189–98. 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao C, Zhang H, Song C, Zhu JK, Shabala S. Mechanisms of plant responses and adaptation to soil salinity. Innovation (Camb). 2020;1(1):100017. 10.1016/j.xinn.2020.100017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Julkowska MM, Testerink C. Tuning plant signaling and growth to survive salt. Trends Plant Sci. 2023;28(5):552–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalaji HM, Goltsev V, Bosa K, Allakhverdiev SI, Strasser RJ, Govindjee. Experimental in vivo measurements of light emission in plants: A perspective dedicated to David Walker. Photosynthesis Research. 2017;134(1):1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moustakas M, Baycu G, Gevrek-Kürüm N, Moustaka J, Csatári I, Rognes SE. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity of photosystem II function during photoinhibition and recovery in salt-stressed Arabidopsis thaliana. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(15):8256.35897832 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Per TS, Khan MIR, Anjum NA, Masood A, Hussain SJ, Khan NA. Jasmonates in plants under abiotic stresses: crosstalk with other phytohormones matters. Environ Exp Bot. 2023;205:105137. [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Zelm E, Zhang Y, Testerink C. Salt tolerance mechanisms of plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2020;71:403–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhao C, Zhang H, Song C, Zhu JK, Shabala S. Mechanisms of plant responses and adaptation to soil salinity. Innov (Camb). 2020;1(1):100017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang Y, Zhang R, Duan X, Hu Z, Shen M, Leng P. Natural cold acclimation of Ligustrum lucidum in response to exogenous application of paclobutrazol in Beijing. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum. 2019;41(1):15. 10.1007/s11738-018-2800-y. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Desta B, Amare G. Paclobutrazol as a plant growth regulator. Chemical and Biological Technologies in Agriculture. 2021;8(1):1. 10.1186/s40538-020-00199-z. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Naeem M, Aftab T, Idrees M, Alam MM, Khan MM, Uddin M. Plant efficacy and alkaloids production in Sadabahar (Catharanthus roseus L.): role of potent PGRs and mineral nutrients. Catharanthus roseus: Current Research and Future Prospects. 2017;12:35–57. 10.1007/978-3-319-51620-2_3.

- 64.Maheshwari C, Garg NK, Hasan M, V P, Meena NL, Singh A, Tyagi A. Insight of PBZ mediated drought amelioration in crop plants. Frontiers in plant science. 2022;13:1008993. 10.3389/fpls.2022.1008993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Leach KA, Braun DM. Soluble sugar and starch extraction and quantification from maize (Zea mays) leaves. Current Protocols in Plant Biology. 2016;1(1):139–61. 10.1002/cppb.20018. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.