Abstract

Aims

Transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis (ATTR-CA) is an important cause of heart failure (HF). Several therapies demonstrated an efficacy in reducing hard and surrogate endpoints. We compared the relative efficacy of therapies evaluated in completed phase III trials.

Methods and results

We conducted a network meta-analysis using data from ATTR-ACT, ATTRIBUTE-CM, APOLLO-B, and HELIOS-B. The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular hospitalizations. Secondary endpoints were changes in the 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire-Overall Summary (KCCQ-OS) scores. For the primary endpoint, tafamidis and vutrisiran demonstrated a significant survival benefit over placebo; acoramidis approached significance. In indirect comparisons, there was no clear evidence of a larger absolute risk reduction for any drug. Tafamidis was associated with the lowest risk for the primary endpoint (surface under the cumulative ranking, SUCRA 82%), followed by vutrisiran monotherapy (70%). Regarding changes in 6MWD, tafamidis and acoramidis had the highest SUCRA curve values (97% and 69%, respectively). For KCCQ-OS changes, tafamidis also had the highest SUCRA (87%), followed by acoramidis (79%) and vutrisiran monotherapy (67%). When the ATTR-ACT trial was excluded from the analysis, vutrisiran monotherapy consistently showed the highest probability of being ranked better than other treatments in terms of primary end-point.

Conclusion

Although differences in trial design and study populations complicate direct efficacy comparisons, tafamidis demonstrated the highest efficacy in improving survival, reducing cardiovascular hospitalizations, and enhancing functional capacity and quality of life in patients with ATTR-CA, but also vutrisiran and acoramidis emerged as viable options.

Keywords: cardiac amyloidosis, Transthyretin, ATTR, Meta-analysis, Network meta-analysis, Trials

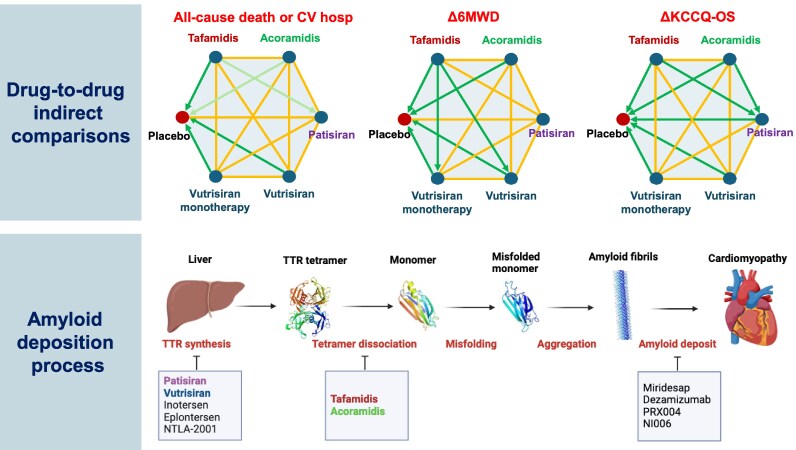

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis (ATTR-CA) is increasingly recognized as a cause of heart failure (HF), yet still often underdiagnosed. ATTR-CA may present in either a wild-type form (previously termed ‘senile’ amyloidosis) or in a hereditary (variant) form linked to pathogenic TTR gene mutations.1 Recent research efforts have led to the development of targeted therapies aimed at improving clinical outcomes for patients with ATTR-CA, and multiple phase III trials have assessed their efficacy. The pivotal ATTR-ACT trial investigated the effectiveness of tafamidis, a transthyretin (TTR) stabilizer that prevents amyloid fibril formation by stabilizing the TTR tetramer. Tafamidis significantly reduced a composite outcome of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular hospitalization over 30 months and showed benefits in functional capacity (6-minute walk distance, 6MWD) and quality of life (QoL; Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire-Overall Summary, KCCQ-OS).2 Consequently, tafamidis became the first approved drug for ATTR-CA without associated neuropathy. In the ATTRIBUTE-CM trial, the TTR stabilizer acoramidis demonstrated similar efficacy, improving a hierarchical composite endpoint including all-cause mortality, cardiovascular hospitalizations, change from baseline in N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide and in the 6MWD compared to placebo. Tafamidis treatment was permitted after the first 12 months from study entry.3 The APOLLO-B trial assessed patisiran, an inhibitor of TTR synthesis, which preserved functional capacity at 12 months, with a secondary composite endpoint including all-cause mortality, HF hospitalizations, and urgent HF visits. One quarter of patients in APOLLO-B were on tafamidis at baseline.4 Lastly, the HELIOS-B trial demonstrated the superior efficacy of vutrisiran, another inhibitor of TTR synthesis, over placebo in reducing a composite of all-cause mortality and recurrent cardiovascular events (defined as hospitalizations for cardiovascular causes or urgent HF visits). This benefit was confirmed in the subgroup receiving tafamidis (40% at study start).5

At present, the first therapy available in clinical practice for isolated ATTR-CA (i.e. tafamidis) has a poor cost-effectiveness profile,6,7 and there are several potential alternatives demonstrating an efficacy over placebo, sometimes in terms of clinical endpoints and on the background of tafamidis therapy. As vutrisiran and acoramidis can now be considered for clinical use, multiple treatment options will be likely available in the near future for patients with ATTR-CA. Additionally, patisiran can be already used for patients with mixed cardiac and neurologic phenotype. Gaining insight into the relative efficacy of the different therapies would be important to select among different treatment options. As head-to-head trials are extremely unlikely, we have conducted a network meta-analysis (NMA) to perform an indirect comparison of treatment effect on clinical, function and QoL on the results of phase 3 trials.

Methods

Study selection and data extraction

The PRISMA NMA checklist8 is provided in the Supplementary material. The search process consisted in the selection of phase III trials on ATTR-CA published as of 1 October 2024: ATTR-ACT,2 ATTRIBUTE-CM,3 APOLLO-B,4 and HELIOS-B.5 These trials compared tafamidis, acoramidis, patisiran and vutrisiran, respectively, to placebo. In detail, tafamidis therapy was allowed after 12 months from enrolment in ATTRIBUTE-CM,3 and from study start in APOLLO-B4 and HELIOS-B.5 Only HELIOS-B provided separate outcome data for the whole cohort and for patients on vutrisiran monotherapy at baseline (i.e. those who were not on tafamidis at baseline).5 As per inclusion criteria, subgroup analyses of trials on ATTR polyneuropathy9,10 were not included.

Two authors (V.C. and A.A.) extracted independently data from the main text, supplementary materials and information provided on ClinicalTrials.gov. Study characteristics, patients’ demographics and clinical characteristics were collected. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Primary and secondary outcome measures were extracted from selected studies at the longest available follow-up (30 months in all studies2,3,5 except for 12 months in APOLLO-B4).

The primary endpoint was ‘all-cause mortality or cardiovascular hospitalization’. This endpoint was available in all studies (with the partial exception of APOLLO-B considering ‘HF events’ rather than ‘cardiovascular hospitalizations’)4 and considered either hierarchical,2,4,5 or non-hierarchical3; in the latter case, only the first event was considered.3 The number of events, number of patients, and person-time were extracted from each study for the primary endpoint. Changes in 6MWD and KCCQ-OS scores were considered as secondary endpoints, being available in all trials.2–5 Mean changes and standard deviation were evaluated. Details of data extracted and used for the analysis of both primary and secondary endpoints are reported in Supplementary material online, Table S1. The risk of bias and quality of study were assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration tool,11 evaluating selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting, and other potential biases. No funding was received for this analysis. Ethical approval was not needed because of the nature of the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Main trial and patients’ characteristics were summarized, and differences were assessed and verified over the control arm across studies to evaluate the transitivity assumption requested by a NMA. A network plot of the active treatments and placebo was obtained to depict the network structures with nodes and line segments clarifying direct or indirect comparisons. For both primary and secondary endpoints, indirect comparisons were made considering a Bayesian framework and using the BUGSnet package in R (v1.1.2)12 using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulation method. For both binary and continuous endpoints, we considered a fixed effects consistency model with 3 chains 100 000 adaptations, 10 000 burn-ins, and 100 000 iterations. The Brooks–Gelman–Rubin statistical method was utilized to evaluate the convergence of data; details are provided in Supplementary material online, Figures S1 and S2. Both fixed and random effects models were considered at first but only fixed effect model was retained as the Deviance Information Criteria (DIC) did not suggest significant gain in the use of a random effects model (difference in DIC values < 3; Supplementary material online, Figures S3 and S4). Similarly, DIC and posterior mean deviance contributions about each point for both the fixed effects consistency and inconsistency models were compared to check model assumption.

For all endpoints, both median and mean values from posterior distribution were obtained, as values were similar only the latter were reported and results are presented using a league table showing the mean posterior distribution for each outcome, expressed as hazard ratio (HR) and 95% credible interval (CrI) for primary endpoint or as difference from placebo and 95% CrI in changes from baseline in 6MWD and KCCQ. Overall ranking of treatments was obtained within the Bayesian framework to rank each outcome measurement from the best to the worst, and the surface under the cumulative ranking (SUCRA) curves based on ranking profiles are shown. An intervention is more effective when its probability of being ranked small is higher. The length of follow-up duration was used as covariate in models for secondary endpoints to take into account the difference in follow-up duration across studies.

As the population enrolled in the ATTR-ACT trial had a more severe disease phenotype compared to other trials (Table 1), and a worse survival, a sensitivity analysis was performed excluding this trial.

Table 1.

Main patient characteristics

| Study | Treatment | Patient n | Age, median (IQR) | ATTRwt, n (%) | Males, n (%) | NYHA I-II, n (%) | NT-proBNP, median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTR-ACT2 | Tafamidis | 264 | 75 (46–88) | 201 (76) | 241 (91) | 186 (71) | 2996 (1752–4862) |

| Placebo | 177 | 74 (51–89) | 134 (76) | 157 (88) | 114 (64) | 3161 (1864–4825) | |

| ATTRIBUTE-CM3 | Acoramidis | 421 | 77 ± 7a | 380 (90) | 384 (91) | 344 (82) | 2326 (1332–4019) |

| Placebo | 211 | 77 ± 7a | 191 (91) | 186 (88) | 179 (85) | 2306 (1128–3754) | |

| APOLLO-B4 | Patisiran | 181 | 76 (47–85) | 144 (80) | 161 (89) | 166 (92) | 2008 (1135–2921) |

| Placebo | 178 | 76 (41–85) | 144 (81) | 160 (90) | 165 (90) | 1813 (952–3079) | |

| HELIOS-B5 | Vutrisiran | 326 | 77 (45–85) | 289 (89) | 299 (92) | 299 (92) | 2021 (1138–3312) |

| Placebo | 329 | 76 (46–85) | 289 (88) | 306 (93) | 293 (90) | 1801 (1042–3082) | |

| Vutrisiran (mono) | 196 | 78 (46–85) | 173 (88) | 178 (91) | 187 (96) | 2402 (1322–3868) | |

| Placebo | 199 | 76 (53–85) | 174 (87) | 183 (92) | 181 (91) | 1865 (1067–3099) |

aAge available only as mean and standard deviation. ATTRwt, wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis; IQR, interquartile range; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Results

Four trials were included; the main patient characteristics are reported in Table 1. The risk of bias was low in all studies, both globally and in individual domains (see Supplementary material online, Figure S5).

The network plot was shaped as a star with six nodes. As for the HELIOS-B trial, results are presented for the whole population treated with vutrisiran (i.e. with or without tafamidis), and also separately for vutrisiran monotherapy.

Primary endpoint

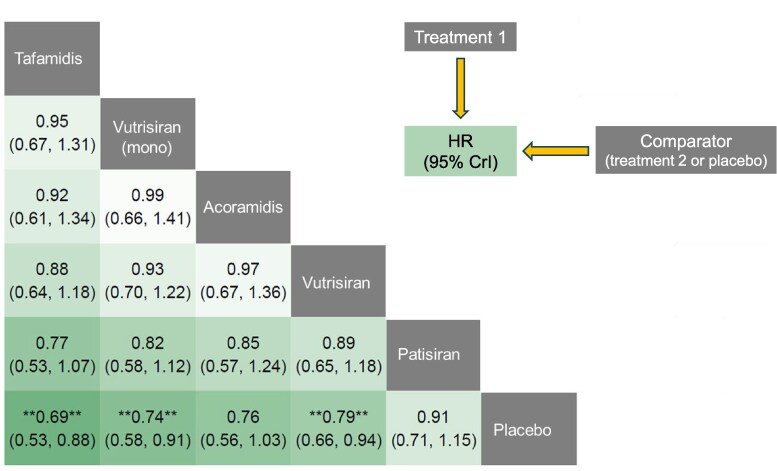

Considering the primary endpoint (all-cause mortality or cardiovascular hospitalization), tafamidis and vutrisiran (either combined with tafamidis or as a monotherapy) conferred a significant survival benefit compared to placebo (see Supplementary material online, Figure S6). Tafamidis showed the greatest relative reduction in the occurrence of the primary outcome as compared to placebo (HR 0.69, 95% CrI from 0.53 to 0.88), followed by vutrisiran monotherapy (HR 0.74, 95% CrI from 0.58 to 0.91); acoramidis showed a trend towards benefit as compared to placebo (HR 0.76, 95% CrI from 0.56 to 1.03). In indirect comparisons, there was no clear evidence of a larger absolute risk reduction for any drug, although there was a signal of a larger effect of tafamidis compared to patisiran, but not to acoramidis or vutrisiran (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Treatment comparisons: primary endpoint. League heat table for the primary endpoint (all-cause mortality or cardiovascular hospitalization) showing the relative treatment effect for direct and indirect comparisons in terms of hazard ratio (and 95% credible intervals, CrI) for the treatment on top compared to the treatment on the right.

Secondary endpoints

The analysis of changes in 6MWD and KCCQ-OS scores suggested that all the active treatments were significantly more effective than placebo in mitigating the decline in functional capacity and QoL, except patisiran for 6MWD (see Supplementary material online, Figure S7).

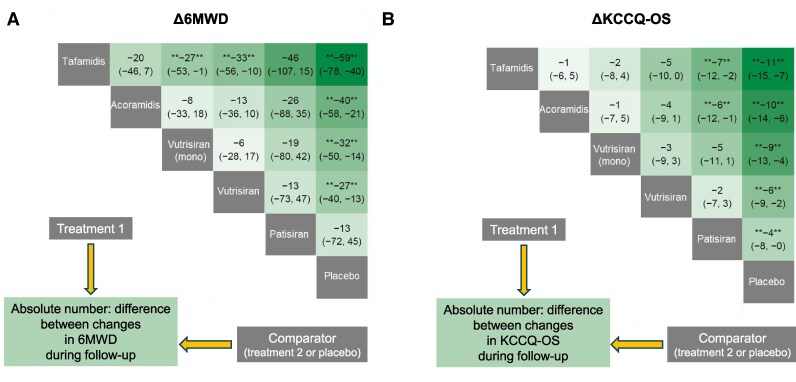

Patients on all active treatments displayed less pronounced declines in 6MWD during follow-up. In absolute values, the difference between tafamidis and placebo was equal to 59 m, between acoramidis and placebo to 40 m, between vutrisiran monotherapy and placebo to 32 m, and between vutrisiran overall (i.e. ± tafamidis) and placebo to 27 m. All differences were significant. From indirect comparisons between drugs, significant differences emerged between tafamidis and vutrisiran monotherapy (absolute difference 27 m favouring tafamidis) and between tafamidis and vutrisiran overall (33 m, favouring tafamidis) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Treatment comparisons: secondary endpoints. League heat tables for the secondary endpoint (absolute mean changes [Δ] in 6-minute walk distance [6MWD] and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire-Overall Summary [KCCQ-OS] score) showing the relative treatment effect for direct and indirect comparisons in terms of reduction on the change (and 95% credible intervals, CrI) for the treatment on top compared to the treatment on the left.

Patients on all active treatments displayed also lower decreases in KCCQ-OS scores compared to placebo. In absolute values, the difference between tafamidis and placebo was equal to 11 points, between acoramidis and placebo to 10 points, between vutrisiran monotherapy and placebo to 9 points, between vutrisiran overall and placebo to 6 points, and between patisiran and placebo to 4 points. From indirect comparisons between drugs, significant differences emerged between tafamidis and patisiran (absolute difference 7 points, favouring tafamidis), and between acoramidis and patisiran (6 points, favouring acoramidis) (Figure 2B).

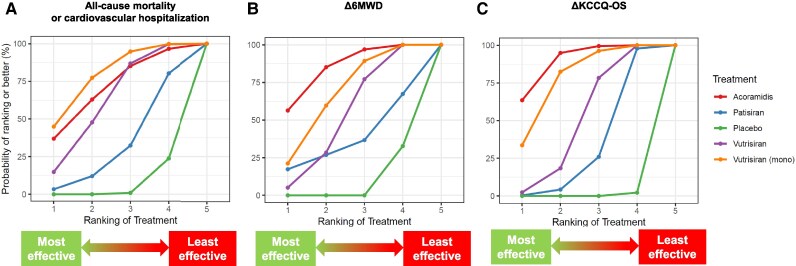

Treatment ranking

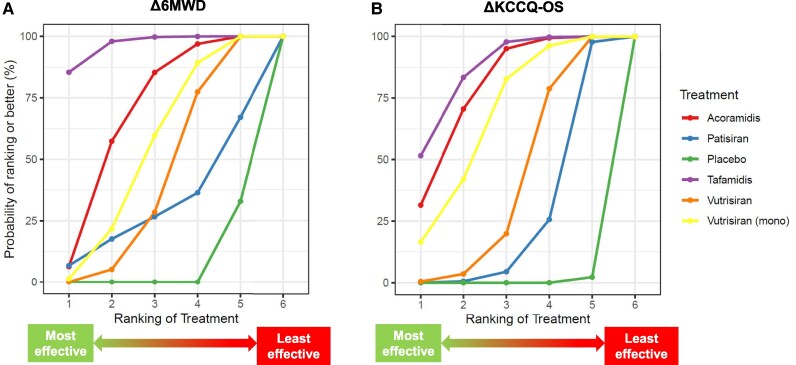

Active treatments and the placebo were ranked according to the extent of reduction in the primary endpoint. Tafamidis was the treatment conferring the lowest risk for the primary endpoint (SUCRA = 82%), followed by vutrisiran monotherapy (70%) (Figure 3). Even for the change in 6MWD, the curve of tafamidis was consistently over the curves of the other treatments (97%), followed by acoramidis (69%) (Figure 4A). For the KCCQ-OS changes, tafamidis had the highest SUCRA (87%), followed by acoramidis (79%), and then by vutrisiran monotherapy (67%) (Figure 4B).

Figure 3.

Primary endpoint: surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) plot. SUCRA plot for the primary endpoint showing the likelihood of ranking for each treatment. X axis represents the possible rank of treatment options; Y axis represents, for each treatment, the probabilities of having each ranked.

Figure 4.

Secondary endpoints: surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) plot. SUCRA plot showing the likelihood of ranking for each treatment for the secondary endpoints of changes in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD; A) and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire-Overall Summary (KCCQ-OS; B).

Sensitivity analyses

When excluding the ATTR-ACT trial from the analysis, only vutrisiran or vutrisiran in monotherapy conferred a significant prognostic benefit in terms of all-cause death and HF hospitalizations as compared to placebo (HR 0.73, 95% CrI from 0.58 to 0.91 and HR 0.79, 95% CrI from 0.66 to 0.94, respectively). No significant difference between drugs emerged from indirect comparisons.

Acoramidis, vutrisiran and vutrisiran in monotherapy performed better than placebo in reducing the decline in 6MWD and KCCQ-OS. Moreover, patisiran was better than placebo in preserving QoL, while acoramidis performed better than patisiran (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sensitivity analysis excluding the ATTR-ACT trial

| All cause death or CV hospitalization | Δ6MWD | ΔKCCQ-OS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CrI) | m (95% CrI) | values (95% CrI) | ||

| Vutrisiran (monotherapy) | vs. placebo | 0.73 (0.58; 0.91)a | −32 (−50; −14)a | −9 (−13; −4)a |

| Acoramidis | 0.76 (0.56; 1.03) | −40 (−58; −21)a | −10 (−14; −6)a | |

| Vutrisiran | 0.79 (0.66; 0.94)a | −26 (−40; −13)a | −6 (−9; −2)a | |

| Patisiran | 0.91 (0.71; 1.15) | −13 (−72; + 44) | −4 (−8; 0) | |

| Vutrisiran (monotherapy) | vs. patisiran | 0.82 (0.58; 1.12) | −19 (−80; + 42) | −5 (−11; + 1) |

| Acoramidis | 0.85 (0.57; 1.24) | −26 (−87; + 35) | −6 (−12; −1)a | |

| Vutrisiran | 0.89 (0.65; 1.18) | −13 (−73; + 46) | −2 (−7; + 3) | |

| Vutrisiran (monotherapy) | vs. vutrisiran | 0.93 (0.69; 1.23) | −6 (−28; + 17) | −3 (−9; + 3) |

| Acoramidis | 0.97 (0.67; 1.37) | −13 (−36; + 10) | −4 (−9: + 1) | |

| Vutrisiran (monotherapy) | vs. acoramidis | 0.99 (0.66; 1.41) | −8 (−33; + 19) | −1 (−7; + 5) |

aIndicates P < 0.05. 6MWD, 6-minute walk distance; CrI, credible interval; CV, cardiovascular; HR, hazard ratio; KCCQ-OS: Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire-Overall Summary.

Only vutrisiran in monotherapy showed a curve consistently higher than other treatments for the primary endpoint, while for both secondary endpoints acoramidis had the highest SUCRA, followed by vutrisiran in monotherapy (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis: surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) plot. SUCRA plot showing the likelihood of ranking for each treatment for the primary endpoint (A) and secondary endpoints of changes in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD; B) and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire-Overall Summary (KCCQ-OS; C).

Discussion

We compared the efficacy of tafamidis, acoramidis, patisiran and vutrisiran in patients with ATTR-CA through a dedicated statistical approach called NMA. Although there was no clear evidence of a larger absolute risk reduction for any drug in indirect comparisons, tafamidis demonstrated the greatest benefit in survival, hospitalization reduction, and QoL improvement, followed by vutrisiran and acoramidis. Sensitivity analyses excluding the ATTR-ACT trial, which included patients with a more severe disease, confirmed vutrisiran efficacy over acoramidis and patisiran.

As the first approved disease-modifying treatment for ATTR-CA without neuropathy, tafamidis remains the benchmark in ATTR-CA therapy. The ATTR-ACT trial demonstrated its superiority over placebo in improving survival rates and secondary endpoints, including functional capacity and QoL, over a 30-month follow-up. This NMA confirms tafamidis role in clinical practice as a therapeutic option for ATTR-CA, highlighting its robust and sustained impact on both prognostic and QoL indicators.

Among other treatments, vutrisiran monotherapy conferred a survival benefit comparable to tafamidis. The trial findings, confirmed by this NMA, also highlighted vutrisiran and acoramidis notable impact on functional capacity and QoL measures, with a high ranking concerning changes in 6MWD and KCCQ-OS, thereby positioning it as viable single-agent options in managing ATTR-CA.

Importantly, the ATTR-ACT trial, which underpins tafamidis approval, involved a patient cohort representing a more advanced disease, with a higher prevalence of hereditary ATTR and with different background pharmacological therapy than those in recent trials assessing alternative disease-modifying drugs like vutrisiran and acoramidis. This discrepancy in baseline clinical characteristics may partially explain tafamidis superior effect size in survival and hospitalization outcomes. Indeed, more severe clinical presentations in the ATTR-ACT cohort might have amplified the impact of tafamidis on critical endpoints, potentially skewing direct comparisons with newer agents. Sensitivity analyses performed in this NMA, including the exclusion of data from ATTR-ACT trial, corroborate this hypothesis.

The possibility of combining therapies, particularly those with different mechanisms of action, represents an exciting avenue for advancing ATTR-CA treatment. The HELIOS-B trial explored this approach by not only allowing concurrent tafamidis with vutrisiran but also providing preliminary data on the feasibility and efficacy of combination therapy. Although data are still limited, combining TTR stabilizers like tafamidis with TTR synthesis inhibitors like vutrisiran might theoretically offer synergistic benefits by addressing different facets of the ATTR amyloidogenic pathophysiology. However, there is some insight from our NMA that vutrisiran monotherapy may be superior to the combination with tafamidis; this finding, possibly related to the more limited room for improvement in patients receiving tafamidis at baseline, is worth of further investigation. Moreover, the economic implications of dual therapies are a critical consideration, given the substantial costs associated with these agents. In addition to its efficacy, vutrisiran subcutaneous administration every three months offers a practical advantage over the daily oral dosing required for tafamidis, which could improve patient adherence and QoL. Furthermore, phase 3 trials on monoclonal antibodies (NCT06183931) or gene editing (NCT06128629) are underway, and are expected to provide additional treatment options for patients with ATTR-CA, requiring further analyses about the relative efficacy and cost-effectiveness of single therapies and combined approaches.

In a recent meta-analysis adopting a frequentist approach, TTR-targeting therapies were confirmed to improve survival in patients with ATTR-CA, with no significant efficacy differences reported between TTR stabilizers and gene-silencing agents.13 Noteworthy, a post-hoc network meta-analysis suggested that patisiran and tafamidis ranked highest for reducing all-cause and CV mortality. While these observations are consistent with our findings on tafamidis, they are more difficult to reconcile for patisiran, which did not demonstrate superiority over placebo for hard outcomes (all-cause mortality, all-cause hospitalizations, and urgent heart failure visits) in the APOLLO-B trial.4

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, and more important, differences in trial design and in study populations complicate direct efficacy comparisons, and any definite conclusion cannot be drawn from the present analyses. For example, a longer follow-up may reveal more pronounced effects on mortality and hospitalization. To address this limitation, all analyses were performed accounting for follow-up duration., Nevertheless, the relatively short follow-up of the APOLLO-B trial may have contributed to the negative findings for patisiran and should be taken into account when interpreting these results. The variability in primary endpoint definition further limits comparability, with APOLLO-B focusing specifically on HF events rather than broader cardiovascular outcomes, potentially underestimating the impact of patisiran on survival outcomes. Additionally, baseline patient characteristics, such as age and disease severity, varied between trials, which may influence drug efficacy perception. For example, the pronounced effect size of tafamidis observed in the ATTR-ACT trial may be partly attributed to the older and more severely affected cohort included in the study. This was the reason why we ran a sensitivity analysis excluding this study. Another possible confounder is tafamidis therapy as part of background treatment after 12 months, in ATTRIBUTE-CM, or from study start, in APOLLO-B and HELIOS-B. Tafamidis therapy could potentially alter outcomes in ways not fully accounted for within the NMA framework, and only the HELIOS-B trial considered patients on tafamidis treatment at baseline or not as separate subgroups. Finally, the relatively small number of trials does not permit the performance of additional sensitivity analyses.

In conclusion, this first comparison of tafamidis with all other therapies for ATTR-CA, limited by difference in trial characteristics, suggests that tafamidis may have the highest efficacy in improving outcome of ATTR-CA patients, with vutrisiran and acoramidis also providing significant prognostic benefit.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

None

Contributor Information

Alberto Aimo, Health Science Interdisciplinary Center, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Piazza Martiri della Libertà, 33 - 56127, Pisa, Italy; Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Fondazione Monasterio, Via Moruzzi, 1 - 56124, Pisa, Italy.

Vincenzo Castiglione, Health Science Interdisciplinary Center, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Piazza Martiri della Libertà, 33 - 56127, Pisa, Italy; Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Fondazione Monasterio, Via Moruzzi, 1 - 56124, Pisa, Italy.

Michele Emdin, Health Science Interdisciplinary Center, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Piazza Martiri della Libertà, 33 - 56127, Pisa, Italy; Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Fondazione Monasterio, Via Moruzzi, 1 - 56124, Pisa, Italy.

Valentina Lorenzoni, Institute of Management, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Piazza Martiri della Libertà, 33 - 56127, Pisa, Italy.

Giuseppe Vergaro, Health Science Interdisciplinary Center, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Piazza Martiri della Libertà, 33 - 56127, Pisa, Italy; Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Fondazione Monasterio, Via Moruzzi, 1 - 56124, Pisa, Italy.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal Open online.

Author contributions

Alberto Aimo (Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Writing—original draft [equal]), Vincenzo Castiglione (Conceptualization [equal], Data curation [equal], Writing—original draft [equal]), Michele Emdin (Conceptualization [equal], Writing—review & editing [lead]), Valentina Lorenzoni (Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [lead], Writing—original draft [supporting]), and Giuseppe Vergaro (Conceptualization [lead], Formal analysis [equal], Supervision [lead], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [lead])

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Fondazione Pisa (Grant number 313/22).

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Aimo A, Merlo M, Porcari A, Georgiopoulos G, Pagura L, Vergaro G, Sinagra G, Emdin M, Rapezzi C. Redefining the epidemiology of cardiac amyloidosis. A systematic review and meta-analysis of screening studies. Eur J Heart Fail 2022;24:2342–2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maurer MS, Schwartz JH, Gundapaneni B, Elliott PM, Merlini G, Waddington-Cruz M, Kristen AV, Grogan M, Witteles R, Damy T, Drachman BM, Shah SJ, Hanna M, Judge DP, Barsdorf AI, Huber P, Patterson TA, Riley S, Schumacher J, Stewart M, Sultan MB, Rapezzi C. Tafamidis treatment for patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1007–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gillmore JD, Judge DP, Cappelli F, Fontana M, Garcia-Pavia P, Gibbs S, Grogan M, Hanna M, Hoffman J, Masri A, Maurer MS, Nativi-Nicolau J, Obici L, Poulsen SH, Rockhold F, Shah KB, Soman P, Garg J, Chiswell K, Xu H, Cao X, Lystig T, Sinha U, Fox JC. Efficacy and safety of acoramidis in transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2024;390:132–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maurer MS, Kale P, Fontana M, Berk JL, Grogan M, Gustafsson F, Hung RR, Gottlieb RL, Damy T, González-Duarte A, Sarswat N, Sekijima Y, Tahara N, Taylor MS, Kubanek M, Donal E, Palecek T, Tsujita K, Tang WHW, Yu W-C, Obici L, Simões M, Fernandes F, Poulsen SH, Diemberger I, Perfetto F, Solomon SD, Di Carli M, Badri P, White MT, Chen J, Yureneva E, Sweetser MT, Jay PY, Garg PP, Vest J, Gillmore JD. Patisiran treatment in patients with transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 2023;389:1553–1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fontana M, Berk JL, Gillmore JD, Witteles RM, Grogan M, Drachman B, Damy T, Garcia-Pavia P, Taubel J, Solomon SD, Sheikh FH, Tahara N, González-Costello J, Tsujita K, Morbach C, Pozsonyi Z, Petrie MC, Delgado D, Van der Meer P, Jabbour A, Bondue A, Kim D, Azevedo O, Hvitfeldt Poulsen S, Yilmaz A, Jankowska EA, Algalarrondo V, Slugg A, Garg PP, Boyle KL, Yureneva E, Silliman N, Yang L, Chen J, Eraly SA, Vest J, Maurer MS. Vutrisiran in patients with transthyretin amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2024;392:33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kazi DS, Bellows BK, Baron SJ, Shen C, Cohen DJ, Spertus JA, Yeh RW, Arnold SV, Sperry BW, Maurer MS, Shah SJ. Cost-effectiveness of tafamidis therapy for transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2020;141:1214–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Castiglione V, Aimo A, Vergaro G. Cost-effectiveness of transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis screening and treatment: a dilemma for the clinician. Int J Cardiol 2024:402;131855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, Chaimani A, Schmid CH, Cameron C, Ioannidis JPA, Straus S, Thorlund K, Jansen JP, Mulrow C, Catalá-López F, Gøtzsche PC, Dickersin K, Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D. The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Solomon SD, Adams D, Kristen A, Grogan M, González-Duarte A, Maurer MS, Merlini G, Damy T, Slama MS, Brannagan TH, Dispenzieri A, Berk JL, Shah AM, Garg P, Vaishnaw A, Karsten V, Chen J, Gollob J, Vest J, Suhr O. Effects of patisiran, an RNA interference therapeutic, on cardiac parameters in patients with hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis: analysis of the APOLLO study. Circulation 2019;139:431–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garcia Pavia P, Gillmore JD, Kale P, Berk JL, Maurer MS, Conceição I, Dicarli M, Solomon S, Chen C, Arum S, Vest J, Grogan M, Hababou C. HELIOS-A: 18-month exploratory cardiac results from the phase 3 study of vutrisiran in patients with hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis. Arch Cardiovasc Dis Suppl 2023;15:31–32. [Google Scholar]

- 11. https://methods.cochrane.org/bias/resources/rob-2-revised-cochrane-risk-bias-tool-randomized-trials. Last access: October 30, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beliveau A, Boyne DJ, Slater J, Brenner D, Arora P. BUGSnet: an R package to facilitate the conduct and reporting of Bayesian network meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019;19:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Prata AA, Katsuyama ES, Scardini PG, Covre AC, Neto WF, Fernandes JM, Barbosa GS, Fukunaga C, Pinheiro RP, Antunes VLJ, Gioli-Pereira L, Fernandes F. The efficacy and safety of specific therapies for cardiac transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2025;25:296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.