Wilson Weatherford (Figure 1) was born on August 6, 1932, in Dallas, Texas. After graduating from Woodrow Wilson High School, he went to Texas A&M, where he received a bachelor of science degree, the distinguished student award, and the distinguished military graduate award. He then went to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, where he received his medical degree in 1958. His rotating internship was at Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC). Thereafter, he was a Public Health Service officer for the city of Dallas for several months and then served in the army for 2 years in Germany, where he received the Army Commendation Medal for Achievements in Preventive Medicine. He returned to BUMC to complete his 3-year residency in internal medicine.

Figure 1.

Wilson Weatherford, MD.

From 1965 to 1996, Dr. Weatherford had a large private practice of internal medicine. He was medical director of Employee Health Services of BUMC from 1971 to 1992. In 1989, Dr. Weatherford was president of the medical staff, and in 1990, he was chairman of the medical board of BUMC. Also in 1989, he helped found and became medical director of the Baylor Center for Restorative Care (BCRC); in 1994, he was named chief of the Division of Geriatrics of the Department of Internal Medicine of BUMC. Dr. Weatherford was instrumental in forming the Baylor Senior Health Network and the Baylor Senior Health Centers and has been medical director of that operation since its beginning. Dr. Weatherford has been a major force at BUMC for nearly 4 decades. He also is a nice guy and a pleasure to be around.

William Clifford Roberts, MD (hereafter, WCR): Dr. Weatherford, I'm grateful that you were willing to talk to me and, therefore, to the readers of BUMC Proceedings. Could you discuss growing up in Dallas, your parents, your siblings, and some of your early memories?

Wilson Weatherford, MD (hereafter, WW): My parents were first-grade sweethearts from Ferris, Texas, 20 miles south of Dallas on I-45. My father was born in December 1899 and my mother in January 1900. Their high school class had about 15 students; the Ferris Independent School District took in all the surrounding farms.

Ferris' population in 1900 and still today is about 2000. Ferris, Texas, started in the mid-1800s. It was founded by 4 Scottish families who moved there from Mississippi: the McDuffs, the McDaniels, the Greens, and one other family, and then the town grew. Everybody there had a Scottish heritage. I am Scot on both sides. Ferris became known for its brick clay—the ‘Ferris brick.’

Another interesting thing is I'm a direct descendant of Red Eagle, who was the Indian chief who fought Andrew Jackson at the battle of Horseshoe Bend. A Scottish trader, Charles Weatherford, came to the USA in the late 1700s and married an Indian princess named Sehoy III, who had a half-breed son whose Christian name was William and whose Indian name was Red Eagle. He became chief of the Creek nation. During the battle, he used straws (reeds) to breathe through while crossing the river so as not to be discovered; that's in Who's Who of America. Though the Creek Nation lost the battle and the war, Red Eagle and Andrew Jackson respected each other. Red Eagle eventually lived with Andrew Jackson for a year at the Hermitage.

My parents married at age 28 and moved to Dallas. Initially, they rented a house on Richmond Street. In 1935, they built a house—the first Federal Housing Administration house in Texas—on McCommas. There was nothing but fields north of there. I came along in 1932, at the height of the depression (Figure 2). We drove the 20 miles to Ferris on Friday, and I spent the weekends playing with my cousins while my parents visited with their parents, brothers, and sisters (Figure 3). Thus, I grew up both in the country and in the city.

Figure 2.

As a child.

Figure 3.

As a toddler in Ferris, Texas.

WCR: Tell me more about your father.

WW: My grandfather wanted my father to run his grocery store in Ferris, but my father, who was a mathematics whiz, went to Trinity University for 2 years and then to Southern Methodist University (SMU) for a while, paying tuition by working at the Ernst & Ernst accounting firm. At that time, Trinity University was located in Waxahachie (which means ‘cow path’ in Indian); it later moved to San Antonio and became a private university. Later, my father joined the United Fidelity Life Insurance Company, started in Dallas by a wealthy family from Wichita Falls. He commuted from Ferris to Dallas by interurban train when he first joined the company. He became treasurer and eventually executive vice president of United Fidelity Life, and he remained there until his death in 1958, when he was only 58 years old. He died from a cerebral hemorrhage at work one day, 2 days after I had graduated from medical school. I was so pleased he got to see me graduate.

My grandfather Weatherford had come to Texas as a cowboy from Tennessee. In a barroom fight one night, a man attacked him. Somebody threw a pistol across the floor to him, and in self-defense he shot the attacker. Afterwards, he jumped on a horse and tore back to Murfreesboro, Tennessee, where he'd come from. Years later he got a call from the fellow; he said that my grandfather should come back to Texas and that he'd been forgiven. They became lifelong friends.

Upon returning to Texas, my grandfather became a gentleman farmer with a modest-sized farm between Lancaster and Ferris. He also founded, owned, and was president of the Farmers and Merchants State Bank. He died at age 83, and his wife died a year later in 1947. My grandparents had 6 children, 5 boys and 1 girl; my father was the next to youngest. One of my uncles moved to the farm and ran it; he was physically gifted, an outstanding athlete who pitched for the Fort Worth Cats and then for the Chicago Cubs. Another uncle became president of the Federal Land Bank.

WCR: What about your mother and her family?

WW: My mother was valedictorian of her class. She had gone to Trinity University for several years and the University of Colorado for a year or so and came back and taught second grade in Wilmer, not far from Ferris. During the depression, hungry people would come to our back door wanting work. She would let them work for a few minutes in the yard to maintain their dignity and then feed them a large meal. This happened many times.

My mother died at the age of 96 in June 1996. She was a very healthy, vibrant lady, who was widowed longer than she was married. She drove a sports car around town in her late 80s; I took it away from her, much to her chagrin, when she was almost 90. She was only 5″ tall, as were her siblings. I got height from my father's side, but not from my daddy, who was 5″6′. I'm 6″1′, and his brothers were tall. My mother was one of 8 children (5 girls and 3 boys). All 3 of my mother's brothers died in their 50s or early 60s from advanced coronary artery disease. The 5 girls lived into their 90s.

My grandfather on the Wilson side (hence my first name) was a real ‘pistol’ and a prominent farmer. He came to Ferris from Tupelo, Mississippi, after his brother had come. As was typical in those days, the oldest son inherited the farm, and the rest of the family had to find their way, much in the old English/Scot-tish heritage. He was a very aggressive guy and a real entrepreneur. He built a very pretty home in Ferris after they left the farm in the early 1900s. The home is now being rejuvenated in the historical district.

In about 1907, my grandfather owned a livery stable and shoed horses and fixed buggies. Ferris was a very prominent little town in Ellis County, and people from all around came and had their livery work done at Wilson's Livery Stable. He had 2 partners, and business boomed. The partners wanted to spend money to expand the business. About that time, a Model T Ford came into town on an old rickety dirt road from Dallas. Being an entrepreneur, my grandfather opined that he could make the roads better for the autos. He declined to expand the livery business with his 2 partners, and they bought him out. Predictably, the livery business went bankrupt.

In the meantime, he had found another fellow named Watson, who at that time was a struggling construction man, and another fellow named Gifford, who had a fledgling business, and the 3 got together and created a dirt-moving company. They built roadbeds with mules and plows. They went on to build Lake Dallas, the dams, Garland Road, the Cotton Bowl, and many things in this area. They did the grading and moved all the dirt so that people could come along and pour the cement. The name of the company—Gifford, Hill, Wilson, and Watson—was subsequently shortened to Gifford-Hill, now a well-recognized construction company, which was bought eventually by Bezoar Industries. You can see it on I-30 on the way to Fort Worth.

My mother's folks mostly lived to be 70. My dad's father died at age 83 and my dad's mother at age 82. My brother (Figure 4), I guess, inherited bad genes. At age 41 he had a heart attack and was found to have severe narrowing of the left anterior descending coronary artery. His ejection fraction was only 25%, but nevertheless, he hunted and fished, swam, ran, and worked out without too much difficulty for the next 17 years. He had a left ventricular aneurysm and died at age 58. He had 2 sons, and another was lost at birth. My mother's brothers died at ages 50, 64, and 66. I had a stress test last year and it was perfect, and I eat whatever I want.

Figure 4.

With his younger brother, Charles, in 1944.

WCR: Who had the greater impact on you, your mother or father?

WW: My dad was an extremely well liked, lovable, nurturing type of guy, quiet and soft-spoken, and he loved to hunt and fish. He and my mother were devoted to each other. My mom was probably the biggest influence on me. I had the intellectual gifts, I suppose, to perform at her level of expectation. In grade school I always finished a test in 10 minutes, and it would take everybody else an hour. I'd make maybe a 98 or 97, and she quite seriously would want to know why I didn't make 100.

WCR: Did studies come easy for you, or did you have to work pretty hard?

WW: I had to study. I was a good student but not a great student. I had interests in many things other than studies. We went to school only 11 years in Dallas at that time, so I started college at 16 and finished at 19.

WCR: Where did you go to school?

WW: I went to Stonewall Jackson Elementary School, J. L. Long Junior High, and Woodrow Wilson High School. Woodrow Wilson High School had the largest ROTC in any high school in the USA. The only 2 Heisman trophy winners from the same high school came from Woodrow Wilson. Boone Powell, Jr., later went to the same high school and was on the basketball team, and we often talked about the Woodrow Wilson Wildcats. Boone and I became friends when he joined Baylor.

WCR: How many students were in the Woodrow Wilson High School when you went there?

WW: My graduating class had about 360 students.

WCR: High school then was 3 years, 10th, 11th, and 12th?

WW: Junior high was eighth and ninth grades, and high school was 10th, 11th, and 12th. When I was in the fourth grade, I was promoted to the sixth grade. It just happened to be on the year that the Dallas public schools decided to go to 12 years. The middle of elementary school was where the extra grade was put in. That's why I was just 16 when I graduated from high school (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

In high school.

WCR: Were you an athlete in high school or junior high?

WW: I was pretty good in everything, but not good enough in any one sport. I never played formally on any team. I was a lifeguard in the summers; I could swim like a fish. I worked as a soda jerk starting at age 12 in the summers. I had a paper route for the Dallas Morning News in high school. Also in the summers, I worked in the brick plant for my uncle; our family owned part of the Ferris Brick Company. We got up at 4:00 AM to work on the kilns where bricks was made. They were fired for 28 days. Gas jets fired the bricks; we wore asbestos shoes and could stay under the tin roof only about 20 minutes because it was hot (≥110AF), and dehydration was a problem. Later in college, I thought the studies were very hard but never as hard as working the kilns in the brick plant.

WCR: Were there any teachers in junior high or high school who really had an impact on you?

WW: The principal in high school had a great impact. He was greatly loved by everybody in the school. An English teacher had an impact on me. She stressed reasoning things out, and if you did she would reward you. Although my mom was a very loving person, she had the highest standards. She demanded excellence in whatever we did. She took it for granted that I would do well. It was one of those expectations that was imprinted on me without ever being articulated.

WCR: What was your home like? Were there a lot of books around?

WW: No, not really. It was a very warm, loving home. I had a great childhood. I had a lot of fun and a lot of friends, and I was left to pursue my own interests. My friends became leading architects, attorneys, congressmen, etc. Nobody ever got in trouble. Nobody thought to get in trouble.

WCR: Did your family have dinner together every night? Were there some family rituals?

WW: Every night we ate together. We'd take trips together, usually in the summer. We often went to Galveston and stayed in one of the cottages on the seawall. We drove to Yellowstone, to Colorado, and to Minnesota.

WCR: Do you remember a typical conversation at the dinner table at night when you were growing up?

WW: Just the events of the day. After television came, which wasn't until I was in college, we'd watch I Love Lucy and similar shows while eating supper. I loved the radio. I listened to I Love a Mystery. I made really good grades in high school and never studied ≥30 minutes at night. I was into everything. I was big in Boy Scouts. I was an Eagle Scout, a Sea Scout Quartermaster, and Air Scout Ace. I was in the Order of the Arrow, God and Country, and the Knights of Dumas until I went to college.

WCR: Did you and your dad spend fun time together?

WW: Yes (Figure 6). My dad was a big hunter and fisherman, and on most weekends, he and I would go to Possum Kingdom, Lake Whitney, or Texoma. I loved that time with my dad. We hunted dove particularly. That's still my big passion. In the past 3 years, I have been to Argentina 3 times to hunt doves. I've been to Spain to hunt partridge, to Scotland to hunt pheasant, and to Denmark to hunt pheasant. I've been to Mexico maybe 20 times to hunt white-winged doves. Two or 3 times a year, I go to West Texas to hunt doves in the fall. I love bird field hunting (Figure 7). I burned out on fishing.

Figure 6.

With his father.

Figure 7.

Dove hunting in Argentina, 2000.

Also, I love golf. I play a fair game of golf. I represented Dallas twice in Scotland for pro-ams (2 pros and 2 amateurs). We'd go as a team. I was playing a 7 or 8 handicap, which is reasonable for an amateur.

WCR: You shot in the high 70s?

WW: Rather routinely. Low 80s at the worst. I've had a couple of rounds in the 60s. I don't play as much as I used to. I play in the Byron Nelson tournament every year. Golfing and bird hunting are my 2 big passions.

WCR: How much of that do you do now?

WW: Very little. I'm just busy with other things. I used to think I couldn't live another week unless I got a round or two of golf in every week. Now, as an employee, I don't feel comfortable taking an afternoon off.

When my youngest boy had a brain tumor at age 9, we spent 13 hours in surgery at Boston Children's, and fortunately, the tumor was benign. It was resected without any residual neurological deficit. That was a gut-wrenching experience for everyone. He was back at St. Mark's school in 2 weeks. When I came home and played golf the next time, I teed off on the first tee and hit a beautiful drive down the middle of the fairway. I stood there getting ready to hit my 2 iron, and all of a sudden, the relevance of golf, which had been so important, seemed so insignificant. I was standing there holding the stick with a white ball in the middle of a pasture, and I thought this was really just a game. Other things take more importance in life when you have experiences like that.

WCR: What year was that?

WW: About 1980. He's cured.

WCR: How you choose Texas A&M for college?

WW: We were all in a military high school. Because I liked the military a lot, I decided early one August that A&M would be fun. I went down and signed up.

WCR: That was in August, and you started in September?

WW: I started a week later. If you came from a major high school, you didn't have to take any kind of test. It cost my dad $254 for the semester, and that included room and board, military uniforms, food, books—the whole business.

WCR: So the whole year cost about $500?

WW: Yes, plus a little spending money. Nobody had cars then. We hitchhiked from home to school and vice versa.

WCR: That was 1950?

WW: Yes. Medical school cost $110 a year. I got all my 8 years of post–high school education for ≤$4000.

WCR: How did Texas A&M strike you? Academically, did you like it?

WW: It was very difficult. I studied hard. I finished with the equivalent of a 3.5 grade-point average and received a distinguished student designation. There was no grade inflation then.

WCR: Did you grow a great deal during that period?

WW: Yes. By the time I was a senior, I was a fairly good student, even better with the pressure off. After medical school acceptance, I took 21 hours the last semester and made 6 A's and a B+. At Southwestern, I finished in the upper third of my class. When talking to Ann Rucker, the registrar, I found that I was lucky to get into medical school. Ann Rucker told me that the medical schools weighted the colleges by their varying difficulties. I was only 1 of 2 Aggies accepted into Southwestern that year. Southwestern tacked half a grade point onto our college grades. There were only 3 medical schools in Texas then: Baylor, Southwestern, and Galveston. Galveston took in more freshmen but cut about half of them after the first year. Southwestern tried to keep its students in school. I got accepted at the University of Texas Southwestern and Galveston but not Baylor. I and everyone else were glad to get in anywhere. I studied very hard in medical school, particularly the first year. As a 16-year-old college student I also studied fairly well, but I focused primarily on extracurricular activities.

WCR: What activities did you participate in during college?

WW: I was company commander of the corps of cadets, and we won one of the best company awards. We marched to mess hall in military formation for 4 years. It was just like West Point. All students had to be in the corps of cadets unless they were disabled or veterans of World War II. There were no girls, and Texas A&M was all white at that time. There were about 5000 students. A lot of hazing and military discipline occurred. During World War II, more generals came out of Texas A&M than out of West Point.

My brother was smarter than I. He received a degree in mathematics from Southern Methodist University cum laude. He won a Bronze Star and an air medal in Vietnam. He was drafted, but he scored the highest of all 500 draftees at Fort Polk and then was sent to officers' candidate school. He commanded a company in Vietnam and won many decorations. When he came back, he got an MBA at the University of Texas summa cum laude.

WCR: Wilson, how did you decide to go to medical school? Were there any physicians in your extended family?

WW: None whatsoever. I had wanted to be a doctor ever since I was a little boy.

WCR: Why?

WW: I'm not sure. I remember watching my mother's father die. Maybe that was a factor. I was in the room with him when he died.

WCR: When you went to college, you were premed from the beginning?

WW: Yes.

WCR: Did science appeal to you in high school and college?

WW: Yes, biological sciences, but what I have always enjoyed was the interpersonal relationship, a country doctor–type of relationship, with patients. I think I had a gift for taking information and using it for bedside care. I could integrate everything into patient care. I had a fabulous practice, one of the largest of internal medicine in Dallas. I did that for 30 years, Bill.

WCR: When you first went into medical school, were there some surprises for you? Was medical school what you expected it to be?

WW: Yes. It was demanding. The first year I just checked out of life and studied. My routine was to go to school all day, come home and have dinner, and study. I lived at home during all 4 years of medical school. We had an upstairs, so it was like my own apartment in my parents' home. As a result, medical school was inexpensive. I'd eat dinner with the family, go out in the yard and hit some golf balls for a while, and then study from 7: 00 PM until 1:00 or 2:00 AM. I always took Saturday night off. I did really well the first year.

WCR: Were there any teachers in medical school who had a major impact on you?

WW: I wasn't inspired by anybody in particular. I loved the gentility of John Chapman, a pulmonologist. He acted like Ronald Coleman, the British actor, and he had come from East Texas. He was charming, smoked a pipe—a total gentleman. We all adored Donald Seldin and stood in awe of him. It was a big thrill when he whipped you with his little pointer when sitting in the front row.

WCR: What made Don Seldin such a legend?

WW: He was a remarkably gifted teacher. The clarity of his presentations, their succinctness, allowed for a mystique about him. He was adored by everybody and not feared at all, just held in the greatest esteem. He was a benign guy. Although he surrounded himself with some malicious teachers, he was not malicious. He was above that. He could take complicated electrolyte and renal problems and make them seem so clear and succinct.

WCR: You started at Southwestern in 1953. At that time, Southwestern was 11 years old. How many students were in your class?

WW: There were 104. We finished with all but 2 or 3 (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Upon graduating from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, 1958.

WCR: Did you have a hard time deciding which specialty to pursue?

WW: LeRoy Kleinsasser, a prominent surgeon at Baylor, asked me on behalf on the surgical department if I would be interested in surgery. He said they would be happy to accept my application for residency in surgery. I did a rotating internship, and those rotations have made me a better doctor. At Southwestern, a very clinically oriented school, we spent tons of time in the emergency room. I had delivered about 160 babies by the time I graduated. As a senior student at Southwestern, I taught the interns from up East how to deliver babies. At Baylor, they took the Southwestern interns and put us in the emergency room rotation the first few months because we had had experience. That was baptism under fire because there was only 1 intern for Baylor's entire emergency room at that time. I really liked internal medicine.

WCR: When in medical school and rotating through internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics-gynecology, pediatrics, and the other services, you just felt most comfortable with internal medicine?

WW: Yes, I really did. I was good at surgery and I was good at obstetrics and the others, but I really enjoyed internal medicine and the doctor/patient thing. I would have been a very good general practitioner because I had a very good bedside manner. People told me that. I was really oriented toward the warm interpersonal relationships with patients. That was, to me, the most satisfying part of it all.

WCR: Wilson, how did you decide to do a rotating internship at Baylor?

WW: I knew I wanted to stay in town. I liked Dallas. I was interested in cardiology, and at that time, cardiology was very low on the totem pole at Southwestern. Tinsley Harrison had left Southwestern for Alabama. Hardly anyone at Southwestern was doing cardiology. I had my fill of Parkland anyway. I was a bit tired of it. I also wanted to practice eventually in Dallas, and so I figured the Baylor contacts would be advantageous for that.

WCR: When you entered Baylor as a rotating intern, how did Baylor strike you?

WW: It was a very nice hospital with some great people. Many of the staff also taught at Southwestern. There was no division of oncology; indeed, it was not even a specialty then. We had only a few people in gastroenterology. Endoscopy had not arrived yet. We had an intensive care unit. I had to rotate through the Veterans Administration Hospital for pulmonary medicine, which then mainly involved tuberculosis and other chronic chest diseases. Both medicine and surgery were at Baylor in 1958. Ralph Tompsett had just come from Cornell a year earlier. I was in his first intern class. He was a mentor and a guy I greatly loved. We became good friends.

WCR: What made him such an impressive figure?

WW: He was very bright, he had a great intellect, and he was a nice person. He was trying to build the department, and he did a fine job. I eventually sat on the search committee for his successor, and we were very fortunate to get John Fordtran, who was outstanding. Mike Emmett has followed admirably in his footsteps. Fordtran built the medicine residency into a nationally recognized program by taking students in the top of their classes. I think I was the first board-certified internist to come out of the internal medicine residency program at Baylor.

WCR: After that rotating internship, you went into the army. How was that experience?

WW: I was going to start my internal medicine residency but was called into the service, and then they delayed my being called. So I had to do something. I worked as an assistant director of public health and was placed in charge of all the public health nurses, communicative disease control, and well-baby clinics for the city of Dallas. I spent almost a year doing that.

WCR: What did you gain from the Public Health Service experience?

WW: I enjoyed it very much. I enjoyed working with and supervising public health nurses. We did tuberculosis control in all of the schools in Dallas and that kind of work.

Because of that experience, when I was called into the service, they sent me to the Fifth Corps headquarters in Frankfurt, Germany, as deputy corps surgeon (Figure 9). I was a captain with 8 years of reserve training. I held a light colonel's job because of my infantry officer training. In case of a war with Russia, we were responsible for medical evacuation for part of Western Europe, including both German and American troops. I also was responsible for communicative disease control for 50,000 troops in Northern Germany. I coordinated a lot with the German health departments and the provost marshal for venereal disease control. I was a preventive medicine officer, a general medical officer, and an infantry officer. My boss was Colonel Hal Jennings, who had been chief of surgery for 9 years at Walter Reed Army Hospital. He stayed a year and then went to Stuttgart. Subsequently he got his star and became head surgeon in Vietnam. He later became surgeon general in the army with 3 stars. We were very good friends.

Figure 9.

While captain in the medical corps, Frankfurt, Germany, 1960.

WCR: Your army experience was quite rewarding?

WW: It was wonderful. I had no patient care responsibilities. I did some fascinating things. I spent most evenings in dress blues entertaining German, Pakistani, and Chinese generals at cocktail parties and dinners. It was very social, but I enjoy that sort of thing. I was on the corps staff, which included several hundreds of thousands of troops. I was there at the time the Berlin wall went up. Although we weren't fighting anybody, it was kind of a hairy experience. My mother was over there at that time. We did not know if we were going to war or not. You remember Checkpoint Charley. I also worked some with military intelligence. For 15 years after I got out of the army, I was not allowed to go behind the Iron Curtain because I had top-secret clearance.

WCR: Where did you work in Germany?

WW: In the I. G. Farben Building, a giant building on a hill in Frankfurt. Eisenhower didn't bomb that building because he wanted to use it for headquarters after the war. The Germans knew that, and they sat on its lawn during the bombing raids because they knew they wouldn't be bombed.

WCR: You were in the army for 2 years?

WW: I spent one summer in officers' candidate school at Fort Lee, Virginia, while in cadet training, and was on active duty later for 2 years.

WCR: Your entire active duty experience was in Germany?

WW: Right.

WCR: Did you travel around Europe a good bit during 2 years?

WW: Yes. Cynthia and I did.

WCR: You were married then?

WW: Yes. Cynthia was a first grade school teacher in Dallas when I interned. She taught in a poor part of town near Baylor. We saved a little money and bought a duplex in East Dallas, so when I came back to do a residency, we lived in one side and rented the other side. A first-year resident at Baylor at that time was paid $20 a month. Cynthia was paid about $3000 a year.

I loved the army in Germany. It was the best 2 years of my life. We had a little money in our pockets. I was a captain with 8 years in the reserves, so I made about what a light colonel made. Cynthia taught school. Every weekend our biggest decision was whether to go to Paris or to Brussels. We had no kids. We weren't fighting a war. I had no patient care responsibilities there except during winter exercises at Grafenwehr, where I lived in the field with the German battalions as their doctor. It was really interesting.

The last baby I ever delivered was in a bar ditch outside of Brussels. While I was on leave attending the World's Fair in Brussels, we came over the hill and saw police and a big car wreck. Lying in a bar ditch was a woman at full term, dilated, on her back on the creek bank. The baby presented. I told everybody I was a doctor. They all got away and held flashlights, and I delivered that kid in a bar ditch. Somewhere today in Brussels is a hemostat that says 6-West Baylor on it, because I clamped the cord with it. After suctioning the baby, I wrapped it in swaddling clothes and sent it off by ambulance with mama to the hospital. We had a great time in the service.

WCR: How long did it take you to learn the German language?

WW: I'm not gifted in languages. I took lessons, and I also took German classes in college. I'm fairly fluent. I can get along fine in Germany. I learned to speak German, and I speak it fairly well. I go back to Germany on vacation as often as possible. I've been back maybe 15 to 18 times.

WCR: That was a great growth period for you?

WW: It not only was that, but it was a break. Being able to enjoy some things after college, medical school, and internship, having a little money in the pocket, and doing some traveling were great (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

At the Frankfurt Fair with wife, Cynthia, January 1961.

When we met, my wife was 13 and I was 17. We grew up 5 houses apart. I used to throw her paper, and she'd come to the door. We met later somewhere else. We've been married 43 years.

WCR: When did you start dating?

WW: She was too young to date when we met. She went to SMU after high school and I went to Texas A&M, so I'd see her on the weekends. We got more serious when I got to medical school.

WCR: When did you get married?

WW: In 1959. We married when I was assistant director of public health and she was teaching school. Within 8 or 9 months we were in Germany. Rather than signing up for 3 years in order to bring her over a year later, I flew her over after I had been there about 3 months. I was not released from the army until August, and I had to write Olin Teague and a bunch of congressmen to get out. They were holding everybody on reserve status because of the Vietnam conflict. That fall, Kennedy started sending troops to Vietnam. I got out about a month before they froze everybody and sent them to Vietnam. I dodged that bullet.

WCR: Were you pleased with your Baylor residency?

WW: Yes, I loved it. I was particularly pleased to join John Bagwell, who was a wonderful man and a great internist, and Jack Edwards. The 3 of us practiced together for 19 years before we took in another partner. Subsequently, we took in 3 other guys. Then, my world changed.

WCR: You started practice with John Bagwell and Jack Edwards right after your residency?

WW: Yes, the next day.

WCR: Where was the office at that time?

WW: 3710 Swiss—the little building on stilts. I practiced there for 29 years.

WCR: How did you enjoy practice?

WW: I loved it. I worked day and night. I was out nights and weekends. I really worked hard. I took care of my patients.

WCR: What was a typical day like for you then? What time would you wake up in the morning?

WW: About 6:00 or 6:30 AM.

WCR: What time would you get to the hospital?

WW: About 7:00 or 7:30 AM.

WCR: You lived in the Lochwood area?

WW: When I first started we lived in Lochwood, off Garland Road, and then we moved to Merriman Park, which is in Lake Highlands. Subsequently, we moved over by NorthPark Center. On a typical day, I'd see 8 or 10 people on morning rounds and be at the office by 9:30 and then see patients until

5:30 or 6:00 PM, go make rounds again in the hospital, and get home between 8:00 and 9:00 PM. I worked every third weekend for almost 30 years.

WCR: On weekends, you were usually quite busy?

WW: Oh man! Ordeal. We'd have 30 patients in the hospital, and all were sick. It was a very busy practice. After John Bagwell died, Jack Edwards and I stayed together and brought in a couple of other fellows, and then Billy Oliver and Mike Highbaugh joined us. We wound up with a group of 6 physicians.

WCR: When did you bow out of private practice?

WW: My practice evolved into something else. I was honored to be elected president of the medical staff in 1989. At the end of that time, I was further honored by being asked to continue as chairman of the medical board at the time when diag-nosis-related groups were coming in and the hospital was going through economic constraints. By that time, Boone Powell, Jr., had asked me to work with Dallas Medical Resource, Ray Hunt, and others on an international plan to develop referral bases at BUMC. We developed outcome measures and mortality statistics.

Boone knew that I was interested in organizational things and perceived that I had an ability to see a little over the hill. We created the first or at least one of the first long-term care hospitals in the USA, namely, BCRC. We had just moved Baylor Institute for Rehabilitation to Gaston Avenue, and there was an empty building. Initially, BCRC consisted of 1 patient, 2 nurses, and 1 physician (me). We started a long-term care hospital. I had to conceive, organize, develop, and market it, and it became a fabulous success. It started in 1989, and we are now in our 14th year. Boone and Jerry Bryant asked me if I would develop that building and become its medical director. I told my wife that that activity would take a couple of hours a day, and she said sure. (I had just finished being in charge of a 5-year rebuilding program at Royal Oaks Country Club.)

Fifty percent of stroke patients used to go directly from BUMC to a nursing home after an average 21-day hospital stay. BUMC was losing almost half a million dollars a year on stroke patients.

By educating the medical staff, we eventually brought the hospital stay down to an average of 4 days. More importantly, by moving patients to BCRC long enough for maximal rehabilitation, 90% of them were able to go home to home health care. It's been calculated that BCRC now saves Baylor a tremendous amount of money each year. Thus, we have gone from losing money annually to actually making a profit on diagnosis-related group 14 (strokes). We won a best practice award from Medicare. Representatives from probably 30 health care systems have come down to look at BCRC and copy what we have done. It's been great.

WCR: How many beds does BCRC have?

WW: Seventy-four. We just added an extension in Garland, and it too has been very successful.

WCR: How did the senior centers evolve?

WW: Elders in Dallas have a major problem accessing physicians. There are 200,000 people ≥65 years of age in Dallas County today. Many physicians in private practice simply quit seeing seniors by discharging them from their practices. I reasoned that we needed to start senior clinics. We started a model for Baylor Health Care System (BHCS) that differed from others. We took areas of town where there were heavy concentrations of seniors, preferably 20,000 within a 5-mile radius. We located the centers in shopping centers or at least in areas where seniors could get a full complement of care (near a drug store and grocery store), preferably without having to get on a freeway.

The first senior center opened on June 23, 1993, in Casa Linda. We rented and outfitted an old building there, the East Dallas Chamber of Commerce building. That morning I expected a few seniors to show up. We had some balloons and punch but had done no previous marketing. By word of mouth, the news got around because Highland Park Cafeteria was across the street, and before the day was over, we had seen ≥1700 seniors, had ≥80 requests for chart transfers, and made ≥100 appointments. The Dallas police had to come to direct traffic. We quickly realized that we had tapped into something. The senior centers became a great success. The seniors loved them. The clinics were oriented entirely to that age group and included prevention and wellness.

We eventually built 12 senior health centers that have served ≥30,000 people. We provide 5000 referrals to medical subspecialists and surgeons and ≥3000 admissions to BHCS hospitals annually. What we've done is hold the senior population to the parent institution, namely BUMC, for secondary and tertiary care while providing customer-oriented primary care with highly qualified and interested physicians and staff. The senior centers have been well received by all physicians, who were getting inundated with 30,000 people they wouldn't otherwise see. We are now trying to build clinics in some underserved areas, such as Fair Park.

I got board certified in geriatrics, and then I went to John Fordtran in 1994 and told him that we had built this nationally recognized program of senior clinics and that we needed a geriatric section (or division) in the Department of Internal Medicine. He said, ‘Fine. You're the chief of geriatrics.’ I said, ‘Thanks very much!’ Four other internists at BUMC have now become board certified in geriatrics other than our recruited geriatricians. We then built the geriatric center, which is the hub of our senior clinics and referral program, and we've built chaplaincy programs. We've also built a nationally recognized frail elderly homebound program. We've developed nursing home relationships that have had fabulous outcome results.

WCR: Is the number of patients now in the senior centers continuing to grow?

WW: Our current census is about 22,000. The attrition rate is 10% a year because the average age is 78.5 years, but we grow by about 2% above that. Persons aged 55 and over are now moving into the senior system.

WCR: So you can be 55 now and come to a senior center?

WW: We had so much pressure from the offspring of the seniors that we let them come if they are 55 years old or older. Students from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center now rotate in our senior clinics. We also have a formal rotation from the Methodist Hospital family practice program, and we have a formal rotation from the family practice residency at Baylor Garland. I run a mentored fellowship in aging/geron-tology for the Baylor graduate school at Waco. They assign a student to me for 3 months, and I give him or her a project for 3-hour credit. We're also a teaching site for the University of Texas at Arlington for graduate nurse practitioners in geriatrics. Texas Tech uses our clinics as teaching sites for doctors of pharmacy. Thus, we do a lot of teaching. We also do research. We've got 3 articles coming out this year. We're presenting 8 abstracts to the American Geriatric Society meeting next month in Washington, DC. One of these abstracts has won a presidential award.

WCR: How many Baylor senior clinics are operating now?

WW: We consolidated the Bedford, Hurst, and Grand Prairie clinics into a single one in Irving. We are in Richardson, Mesquite, Garland, Hillside, Pleasant Grove, Fair Park, Irving, and Brookhaven.

WCR: What's the average number of patients seen at each of these clinics each day?

WW: The average doctor sees about 15 patients a day.

WCR: How many physicians are at each of these clinics?

WW: Usually 2 doctors and a nurse practitioner. In addition, there's a pharmacist, dietitian, social worker, nurse, other support personnel, and x-ray facilities. We have mammography, and densitometer vans come by every 2 weeks. At one time we had glaucoma vans come by to check vision. The whole idea is to take the mountain to Mohammed by delivering care in the community setting.

WCR: Are all the physicians at these clinics on salary from BUMC?

WW: Yes. They are salaried via a production model such that there is a basic draw with incentives built in. There's an expectation that they see a minimum number of patients daily. They get benefits like other BUMC employees, with paid time off and matched retirement. The physicians are employees of the HealthTexas Provider Network. We now have 7 really fine board-certified, fellowship-trained geriatricians in our geriatric center. One oversees long-term care, another the academics and teaching, another the geriatric centers assessment program, etc. I am very proud of what we've been able to build in the geriatric section. We had nothing 10 years ago, and now we've got national recognition from both the U.S. News & World Report and the American Geriatric Society. We have the largest group of geriatric patients in the USA. Medicare uses some of our patient data.

WCR: Is Medicare taking care of all the expenses in these senior clinics?

WW: It worked well when we were cost based. More recently, we've gone into ambulatory patient group payments, which was a major hit to us because previously the salaries of ancillary people who contributed to the prevention and wellness programs were reimbursed at cost report time by the federal government. Medicare now pays a certain fee for that service, and payments are far less. It became a financial constraint. Additionally, Medicare, while saying it wants better care for the elderly, reduced pay for primary care physicians by 5.4%. While Medicare wants more care, more prevention, more wellness, and more exposure of care for the elders, at the same time it is removing more and more of the reimbursements for these activities. The net effect is we're going to wind up with nobody seeing seniors. Somebody has to see the seniors. They're going to come into the emergency room if there is not a clinic for them. We are now still having to work under tremendous constraints.

WCR: What do you envision will happen regarding compensation by the federal government for Medicare-aged people?

WW: What's happening now is terribly distressing. A big surprise for offspring of senior family members who go to a nursing home is learning that Medicare pays nothing for nursing home care. A senior in a nursing home is allowed to keep a certain income, a home, certain cash value in life insurance policies, and an inexpensive car. All other savings must be spent in paying the nursing home bills. When all those resources are exhausted, the patient can apply for Medicaid. A Medicaid bed, however, is underfunded by about $15 a day at most nursing homes. Therefore, many nursing homes refuse to take Medicaid-funded patients. Thus, we must keep the elderly out of nursing homes for as long as possible. This problem is a major societal issue. On top of this underfunding, the number of seniors is growing enormously. A catastrophe will occur at some point. We're postured to take care of these elderly people, but we've got to have reasonable re-imbursement to do it. We actually save the government money by what we do. They turn around and take that money away in order to save them money. It's crazy. It's kind of a classic governmental approach to things.

WCR: What is your day like now, Wilson?

WW: I have a meeting almost every morning at 7:00. I inspect facilities, put out fires, have strategy sessions, see some consults, teach, and lecture a lot. I speak all over the country. Last year I spoke at the Johns Hopkins review course on geriatrics, and soon I will speak at Rush-Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago and at the University of Chicago.

WCR: Are you getting competition in the senior clinics from the other hospital systems now?

WW: None. They've tried to create models, but their models were flawed and unsuccessful.

WCR: Are the physicians in your senior clinics happy there?

WW: They're very happy. We've never had anybody leave because of dissatisfaction with the job. Physicians now are beginning to polarize either to hospital work or to ambulatory care. Our physicians want ambulatory care. They have no night or weekend call, they receive nice paid time off, and they can participate in academic teaching. We have geriatric rounds twice monthly, and they're very good. Each physician is required to attend at least 50% of them, as well as 50% of the Department of Internal Medicine grand rounds. The clinics don't open on Tuesdays until 9:30 AM so that the medical grand rounds lectures can be attended. Each physician maintains advanced cardiac life support status. Each physician also participates in chronic disease management and is rewarded economically for that. Longevity is also rewarded.

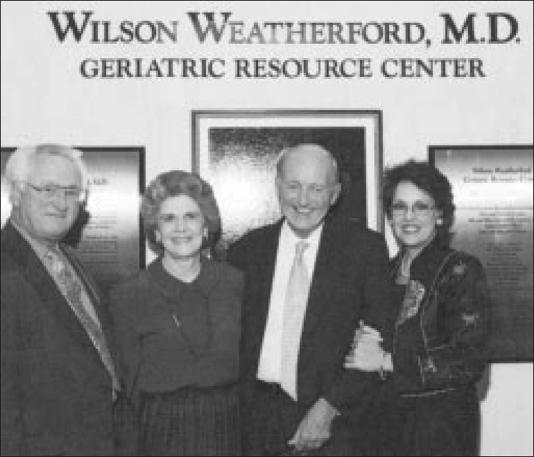

WCR: Wilson, you've been involved in a lot of activities at Baylor through the years. What ones are you most proud of?

WW: I'm most honored by having been elected president of the staff and chairman of the medical board and by having the geriatric center library named for me (Figure 11). That was a singular honor for me. The creation of the BCRC and of the Division of Geriatrics, both of which have received national acclaim, are both personal and Baylor achievements. We've had people like Boone Powell and Joel Allison at Baylor who allow you to create. Joel is great, and Tim Parris is a gifted and brilliant administrator. He's doing a fabulous job as president of BUMC. I consider them good friends. We hunt and fish together. Both Joel and Tim see well over the hill and down the road. The thing that's made me the happiest is to have all these fellows as friends. We've always been very blessed in having some really competent people at Baylor.

Figure 11.

At the dedication of the Wilson Weatherford, MD, Geriatric Resource Center. Left to right: BHCS Foundation President Charles Cooper, donor Margaret Sharpe, Dr. Weatherford, and BHCS Foundation Vice President Milla Perry Jones.

WCR: Your weekends are much quieter now than they were when you were in private practice.

WW: Yes, I come down to the office most Saturdays and Sundays because I still read electrocardiograms, which I've done for years. I'm certified to do that. I'm just so busy during the week that it's hard to organize my thoughts. I'll spend 3 or 4 hours on Saturdays alone, constructing a talk or preparing a manuscript. I like that.

WCR: What do you do in your spare time now? Do you still hunt and play golf?

WW: I work in the garden, and Cynthia and I do other things as well.

WCR: Tell me about Cynthia and your family.

WW: We have 3 boys (Figure 12). None has an interest in medicine. One still is a student in the Houston area. One runs a small computer service, and one has a small construction business.

Figure 12.

With his wife and 3 sons in Acapulco, around 1982.

WCR: Are they married?

WW: No. One was, but no longer.

WCR: Any grandchildren?

WW: No, and don't want any, thank you.

WCR: You both have lived here in Dallas a long time. You must have a lot of friends?

WW: I can't go anywhere where I don't run into 2 or 3 friends. It always amazes my kids. I went into a store the other day, and 3 of the 4 people standing in line were friends of mine. One guy said, ‘Do you know everybody in Dallas?’ I said, ‘Just about.’ Having grown up and gone to school here, not a day goes by that I don't see somebody I know.

WCR: Who were some of your classmates in medical school who are around Baylor now or around Dallas?

WW: Weldon Tillery, who was chief of pathology until recently; George Hurt and Eugene Todd, both urologists; Bob Allison, an internist; and Ted Bywaters, an orthopaedist. Dan Polter, chief of gastroenterology, is a contemporary.

WCR: What plans do you have for the rest of your professional career?

WW: I hope to work until I fall over.

WCR: You enjoy it?

WW: Yes. I don't know what I'd do with myself if I didn't work. I'm not through building, as they say. I hope I can continue to work for a number of years. A lot of what I do now, Bill, is mentoring. I enjoy seeing people fulfill what they want to do in their careers. I'm really pleased that we've created a whole new delivery system of care.

WCR: How big are the senior clinics from a square footage standpoint?

WW: Each is about 7500 square feet, including roughly 12 examining rooms, an ancillary lab, and an x-ray facility. The one at Hillside is somewhat larger since it has a big aquatic pool. The pool is full all day long, from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM. It allows nonweightbearing exercise with a geriatric temperature and geriatric design. We gerrymandered an old President's Health Spa that went bankrupt and built our clinic there but used their pool.

WCR: Tell me about your geriatric chaplaincy program.

WW: I got some wealthy friends to fund that. It's been very successful. We have 3 chaplains now, and it's for spiritual support for the elderly. Patients get counseling at the centers or the chaplains go to the patients' homes. Elders have a lot of spiritual needs. We had ≥1000 spiritual counseling sessions last year.

WCR: Wilson, it is my understanding that in 1900, the average American had a life expectancy of about 50 years, and in 2000, it was about 80 years.

WW: Yes, 79.5 for men and 83 for women.

WCR: So in 100 years it has gone up 30 years. What is the life expectancy going to be in 2100, a hundred years from now?

WW: I don't know the answer to that. I suspect it will rise but at a slower rate. If you control cancer, cholesterol, and infection, there's no reason you can't live 120 years. I'm not sure what the quality of life would be. Just think of the social, economic, and health implications of that.

WCR: Wilson, what are the most common problems you see in the 12 senior clinics?

WW: The most common things we see are hypertension and degenerative arthritis. Diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease also are very common. We work under a concept called ‘compression of morbidity.’ Instead of having a gradual decline from age 65 consuming many resources and making patients feel lousy, we spend a little bit on prevention to keep seniors well and productive until the last few months. It took the government 30 years, Bill, to realize that if you spent $1 for prenatal care, $10 in mental retardation care would be saved. If we spend a little bit on wellness for the elderly and then use advance directives and other things, we could save money and at the same time have a healthier population.

WCR: What's going to happen regarding suicide in the elderly? If I had been healthy up to age 90 and all of a sudden I was in a very debilitated situation, suicide is not a bad way to go.

WW: And suicide is not uncommon. About 15% of the elderly are depressed. Depression in the elderly has multifactorial reasons, including change of job status, loss of sense of value, chronic illness, and family disruption or loss. Our generation and older generations tend to tough things out, not take pills, and try to resolve problems ourselves. In our clinics, depression approaches 20%. Many elderly would respond to medications, but they don't know that the medications exist. By age 90, most people are dependent on somebody else. My mom, who was very religious, said, ‘Why don't you let me go?’ I said, ‘We need you here, Mom. What are you talking about?’ She said, ‘I'm ready to go home and be with the Lord.’ She was serious about that. She would never do anything, but she was totally ready to die. I think you have to be there to feel that way. I don't know the answer to your question.

A prominent author called me one day from New York and said, ‘I've heard of you.’ And I said, ‘Thank you.’ He said, ‘I've got an aunt whom I adore. She helped me grow up with my mom in East Texas. She now lives in New Mexico. She's seen a doctor but didn't believe that he gave her the time and attention she needed. I would feel better if she had another opinion. She's not thinking, she's apathetic, she's lost 30 lb.’ He went through a whole litany of things that were wrong. He had her brought down to see me, and she had been misdiagnosed. She had very significant orthostatic hypotension, which had never been dealt with, from hypoperfusing her brain. She couldn't drive or think straight or walk steadily. She was profoundly depressed. I corrected her orthostatic hypotension and her atrial fibrillation, which was intermittent, by controlling the ventricular rate. I also corrected her vitamin B12 deficiency and treated her depression with low-dose Zoloft. In 6 weeks, this woman drove to my office, walked in, and was fully cognizant, alert, and in sinus rhythm. She said, ‘I have never felt better in my life.’ She then started volunteering in the hospital near her home. The author sent me one of his books with a nice note in it.

WCR: Wilson, is there anything that you'd like to talk about that we haven't touched on?

WW: I don't know what it'd be. I owe Baylor a lot. I hope I've returned some of the nice things they've done for me.

WCR: Wilson, on behalf of the readers of BUMC Proceedings, thank you.

WW: My pleasure.