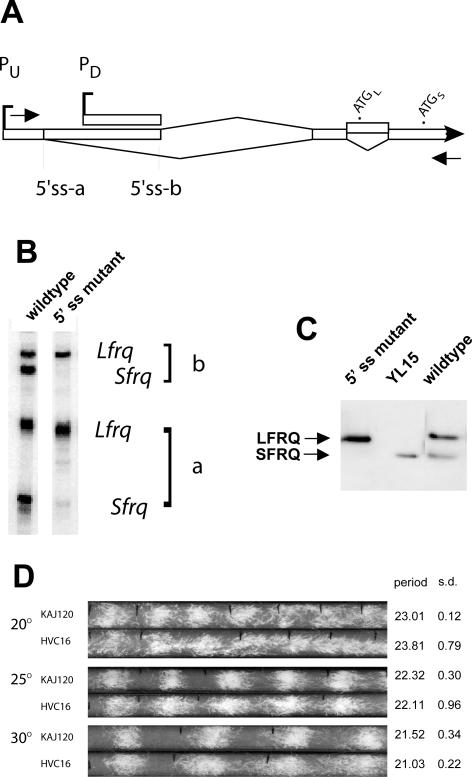

Figure 2.

Splicing of intron 2 is necessary for translation to initiate at AUGS. (A) Schematic of the 5′ end of frq (see Figure 1) with primers for RT-PCR indicated by arrows. (B) RT-PCR products amplified from total RNA from a wild-type strain and a frq10 strain transformed with a frq construct (pHVC16) in which the 5′ splice site for intron 2 has been mutated (see text). The four bands correspond to the top four transcripts depicted in Figure 1; this primer pair would not amplify transcripts coming from PD. Note the absence of the bands (Sfrq) in the 5′ss mutant lane that correspond to splicing of intron 2; the two remaining bands reflect the use of alternative 5′ splice sites a and b in the large 5′ UTR intronic region, respectively. (C) Western analysis of FRQ protein made in three strains: wild-type, HVC16, and YL15 (a strain bearing a deletion of five uORFs, as well as AUGL, which makes only SFRQ; Liu et al., 1997). The 5′ splice site mutant protein shown was prepared from tissue grown at 30°C, but other temperatures give a similar pattern with lower expression. The other strains were grown at 25°C; all were harvested 16 h after transfer to darkness (DD16), in the subjective morning. The extracts were treated with lambda protein phosphatase before analysis to allow clear visualization of SFRQ and LFRQ (Garceau et al., 1997). (D) Race tube analysis of strain HVC16 compared with KAJ120 (a transformant bearing a complete wild-type copy of frq and surrounding sequences; Liu et al., 1997) at three temperatures. The average periods and SDs are shown on the right (n = 6).