Abstract

Expression of the Escherichia coli sdhCDAB operon encoding the succinate dehydrogenase complex is regulated in response to growth conditions, such as anaerobiosis and carbon sources. An anaerobic repression of sdhCDAB is known to be mediated by the ArcB/A two-component system and the global Fnr anaerobic regulator. While the cAMP receptor protein (CRP) and Cra (formerly FruR) are known as key mediators of catabolite repression, they have been excluded from the glucose repression of the sdhCDAB operon. Although the glucose repression of sdhCDAB was reported to involve a mechanism dependent on the ptsG expression, the molecular mechanism underlying the glucose repression has never been clarified. In this study, we re-examined the mechanism of the sdhCDAB repression by glucose and found that CRP directly regulates expression of the sdhCDAB operon and that the glucose repression of this operon occurs in a cAMP-dependent manner. The levels of phosphorylated enzyme IIAGlc and intracellular cAMP on various carbon sources were proportional to the expression levels of sdhC-lacZ. Disruption of crp or cya completely abolished the glucose repression of sdhC-lacZ expression. Together with data showing correlation between the intracellular cAMP concentrations and the sdhC-lacZ expression levels in several mutants and wild type, in vitro transcription assays suggest that the decrease in the CRP·cAMP level in the presence of glucose is the major determinant of the glucose repression of the sdhCDAB operon.

INTRODUCTION

The term carbon catabolite repression is currently in use to describe the general phenomenon in microorganisms whereby the presence of a carbon source in the medium can repress expression of certain genes and operons, whose gene products are often concerned with catabolism of alternative carbon sources. The mechanisms of carbon catabolite repression in response to rapidly metabolizable carbon sources have been extensively examined in Escherichia coli (1,2). In the vast majority of documented cases, the preferred carbon source is glucose with the famous E.coli glucose–lactose diauxie as the classical example. The glucose-mediated catabolite repression, termed glucose repression, is mainly mediated by the proteins of the phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP):sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS). This system consists of sugar-specific PTS permeases, also referred to as enzymes II, and two general PTS proteins, enzyme I and histidine-containing protein (HPr), that participate in the phosphorylation of all PTS-transported carbohydrates. The glucose-specific PTS proteins consist of the soluble enzyme IIAGlc (EIIAGlc) and the membrane-bound enzyme IICBGlc (EIICBGlc). During translocation of glucose, a phosphoryl group derived from PEP is transferred sequentially along a series of proteins (enzyme I, HPr, EIIAGlc and EIICBGlc) to the transported glucose molecule.

Central to carbon catabolite repression is the phosphorylation state of EIIAGlc. In the presence of glucose, unphosphorylated EIIAGlc binds and inhibits various proteins involved in uptake and metabolism of non-PTS carbohydrates by a mechanism termed inducer exclusion (1,3). However, in the absence of glucose, adenylate cyclase is known to be activated to increase the intracellular amount of cAMP, the allosteric effector necessary for the cAMP receptor protein (CRP) to bind efficiently to DNA and activate transcription at more than 100 promoters (4). A popular model for the regulation of adenylate cyclase activity is that the phosphorylated form of EIIAGlc generated in the absence of glucose stimulates adenylate cyclase activity; thus, glucose transport is presumed to lead to dephosphorylation of IIAGlc, resulting in a de-activation of adenylate cyclase and the glucose repression of many genes (1). Recently, the dephospho-form of EIIAGlc was also shown to interact with FrsA to regulate the flux between respiration and fermentation pathways (5), supporting importance of EIIAGlc in catabolic regulations.

Expression of the E.coli sdhCDAB operon encoding the succinate dehydrogenase complex, the sole membrane-bound enzyme of the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, has also been known to be regulated in response to carbon supply as well as anaerobiosis (6,7). Recent study also revealed that a small RNA, RyhB, down-regulates the mRNA level for sdhCDAB operon at the post-transcriptional initiation level in response to iron availability (8). For the anaerobic repression of sdhCDAB, two global regulatory circuits were shown to be involved: the ArcB/A two-component system and the Fnr anaerobic regulator modulate sdhCDAB expression over a 70-fold range to provide different amounts of enzyme depending on the cells' needs for energy and carbon intermediates (7,9). While the molecular mechanisms underlying the anaerobic repression and the iron availability-dependent regulation have been well documented, the mechanism underlying the glucose repression is still not clear. Although CRP and Cra are known to be the key regulators of catabolite repression, they had been dismissed from the glucose repression of the sdhCDAB operon, although a putative CRP-binding site was proposed to be located on the sdhC promoter region (7). Through a series of genetic analyses to identify the regulator gene(s) involved in the glucose repression of the sdhCDAB operon, it was reported that the EIICBGlc protein acts as a crucial mediator in the glucose repression (10). Recently, it has been shown that the dephospho-form of EIICBGlc can sequester the global repressor Mlc through the direct protein–protein interaction and induce the expression of the Mlc regulon including the genes encoding PTS proteins (11–13). Although Takeda et al. (10) identified mlc as the gene responsible for the multicopy effect on the glucose repression of the sdhCDAB operon, they concluded that the single copy mlc gene on the chromosome is not directly involved in the mechanism of glucose repression of the operon.

In this study, we re-investigated regulation of the sdhCDAB expression by glucose and the PTS to elucidate the mechanism underlying the glucose repression. We conclude that the general carbon catabolite repression regulator CRP directly mediates the glucose repression of the sdhCDAB operon in a cAMP-dependent manner.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Cyclic AMP and orthonitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) were obtained from Sigma. RNA polymerase saturated with σ70, [γ-32P]ATP and [α-32P]CTP were purchased from Amersham Biosciences. Nucleotide triphosphates were from MBI Fermentas. The cycle sequencing kit was from Epicentre Technologies (Madison, WI).

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. To generate the isogenic arcA, crr, ptsG, mlc, crp and cya deletion mutants, the indicated alleles were introduced into parental strain TSDH00 by P1 transduction (14). Luria–Bertani broth (LB) medium was used for the routine growth of bacteria unless otherwise indicated. If necessary, media were supplemented with sugars (40 mM). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 µg/ml; kanamycin, 20 µg/ml; chloramphenicol, 30 µg/ml and tetracycline, 25 µg/ml.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| MG1655 | Wild-type E.coli | (44) |

| MC4100 | F-relA1 araD139(argF-lac) U169 rpsL150 flb5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR thiA | (45) |

| ECL618 | F9 arcA2 zjj::Tn10, Tetr | (46) |

| MG1655Δmlc | MG1655 mlc::Tetr | (21) |

| TP2865 | F-xyl argH1 ΔlacX74 aroB ilvA Δcrr, | (47) |

| SR702ΔptsG | araD139 argF-lacU169rpsL150 thiA1 relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR suhX1 ptsG::cat, Cmr | (5) |

| YJ2004 | W3110 lacU169 gal490 CI857 (cro-bioA) mlc::TetR | (21) |

| SA2777 | F-his rpsL relA Δcrp, Cmr | (17) |

| CA8000Δcya | CA8000 Hfr relA1 spoT1 thi-1 cya-1400:: | (30) |

| TSDH00 | MC4100 λ [Φ(sdhC′(−312/+450)-′lacZ)] | This work |

| TSDH01 | TSDH00 ΔarcA, Tetr | This work |

| TSDH02 | TSDH00 Δcrr, | This work |

| TSDH03 | TSDH00 ptsG::cat, Cmr | This work |

| TSDH04 | TSDH00 mlc::Tetr | This work |

| TSDH05 | TSDH00 crp::cat, Cmr | This work |

| TSDH06 | TSDH00 Δcya, | This work |

| TSDH10 | MC4100 λ [Φ(sdhC′(−183/+450)-′lacZ)] | This work |

| TSDH20 | MC4100 λ [Φ(sdhC′(−126/+450)-′lacZ)] | This work |

| TSDH30 | MC4100 λ [Φ(sdhC′(−60/+450)-′lacZ)] | This work |

| TSDH40 | MC4100 λ [Φ(sdhC′(+26/+450)-′lacZ)] | This work |

| TSDH50 | MC4100 λ [Φ(sdhC′(−312/+450)-′lacZ)], with mutated CRP binding site | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRE-His-Tag | N-terminal 6 histidine in pRE1, Ampr | (16) |

| pBR322 | Cloning vector | (48) |

| PJHK | pRE1-based expression vector for EIIB | (12) |

| pHisEIIB | pRE1-based expression vector for His-EIIB | This work |

| pBRcrp | crp in pBR322, Tetr | This work |

| pSA600 | Supercoiled plasmid containing rpoC terminator, Ampr | (17) |

| pTSDHpro | sdhC promoter region in pSA600 | This work |

| pRS415 | lacZ lacY+lacA+, Ampr | (19) |

| pRS-sdh0 | pRS415 [Φ(sdhC′(−312/+450)-′lacZ)], Ampr | This work |

| pRS-sdh1 | pRS415 [Φ(sdhC′(−183/+450)-′lacZ)], Ampr | This work |

| pRS-sdh2 | pRS415 [Φ(sdhC′(−126/+450)-′lacZ)], Ampr | This work |

| pRS-sdh3 | pRS415 [Φ(sdhC′(−60/+450)-′lacZ)], Ampr | This work |

| pRS-sdh4 | pRS415 [Φ(sdhC′(+26/+450)-′lacZ)], Ampr | This work |

| pRS-sdh5 | pRS415 [Φ(sdhC′(−312/+450)-′lacZ)] with mutated CRP binding site, Ampr | This work |

To construct pHisEIIB, in which expression of the EIIB domain (the cytosolic domain of EIICBGlc) tagged with 6 histidines at its N-terminus (His-EIIB) is under the control of the pRE1-vector system (15), the pJHK plasmid (12) was digested with NdeI and BamHI, and the fragment encoding the EIIB domain was cloned into pRE-His-Tag (16).

To construct pBRcrp, in which crp expression is under the control of its own promoter, the sequence covering the crp promoter and coding regions was amplified by PCR using a mutagenic primer to create a PstI site (underlined) 316 nt upstream of the crp start codon (5′-CCC TTC GAC CCA CTG CAG TCG CGC TTG CAT-3′) and a reverse primer located 256 nt downstream of the TAA stop codon (5′-GCG ACG CAC CAA TGA TTA AGC GTT TGA TGA AAA-3′). An SspI site is located 194 nt downstream of the stop codon in this PCR product and the 1137 bp PCR product digested with PstI and SspI was cloned into vector pBR322.

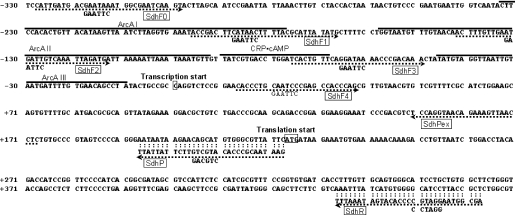

To construct pTSDHpro used as the supercoiled template for assay of in vitro transcription from the sdhC promoter, the DNA fragment covering from the position −183 to +209 relative to the transcription start site of sdhC (9) was amplified by PCR using SdhF1 containing an engineered EcoRI site and SdhP containing an engineered PstI site as the upstream and downstream primers, respectively (Figure 1). The PCR product digested with EcoRI and PstI was ligated into the corresponding cloning sites in front of the rpoC terminator in the plasmid pSA600 (17). Supercoiled template was prepared by Plasmid mini kit (Qiagen) in RNase-free condition for the in vitro transcription assay.

Figure 1.

Organization of the regulatory sites in the sdhC promoter region. The nucleotide sequence between −330 and +470 with respect to the transcription start site of the promoter is shown. Lines above the sequence indicate the three ArcA binding sites and one presumable CRP binding site on the sdhC promoter, and the transcription start point and the translation start codon are marked in boxes. The dashed arrows below the sequence indicate the oligonucleotides SdhF0, SdhF1, SdhF2, SdhF3, SdhF4, SdhPex, SdhP and SdhR, and engineered restriction sites are shown below the arrows. The transcriptional start site and ArcA binding regions were from the previous report (9).

Primer extension assay

Primer extension reactions were carried out as described previously (18). Cells were grown to A600 of 0.5, and total E.coli RNA was purified using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and resuspended in sterile distilled water. Purified [γ-32P]end-labeled primer SdhPex (Figure 1) was mixed with 30 µg of total cell RNA. The mixture was heated to 60°C and then allowed to cool to room temperature over a period of 1 h. After annealing, 50 µl of reaction solution was added, which contained 700 µM dNTPs, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.3 and 100 U of SuperscriptII reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). After the mixture was incubated at 40°C for 70 min, 2 µl of 0.5 M EDTA was added into the reaction mixture and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The DNA was precipitated and resolved on an 8 M urea, 5% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography. The same primer was also used for sequencing the sdhC promoter region.

Construction of transcriptional lacZ fusions

To prepare the sdhC-lacZ fusion plasmid pRS-sdh0, the DNA fragment covering from positions −312 to +450 relative to the transcription start site of sdhC was amplified by PCR using SdhF0 and SdhR containing an engineered BamHI site as the upstream and downstream primers, respectively (Figure 1). The PCR product digested with EcoRI and BamHI was ligated into the corresponding cloning sites of pRS415 (19) to generate the sdhC-lacZ operon fusion plasmid pRS-sdh0. Similarly, the sdhC-lacZ fusions pRS-sdh1, pRS-sdh2, pRS-sdh3 and pRS-sdh4 were constructed first by the PCR amplification method and subsequently cloned into EcoRI/BamHI-digested pRS415 after digestion with the same enzymes. The DNA fragments covering from positions −183 (pRS-sdh1), −126 (pRS-sdh2), −60 (pRS-sdh3) and +26 (pRS-sdh4) to +450 bp relative to the sdhC transcription start were amplified using oligonucleotides SdhF1, SdhF2, SdhF3 and SdhF4 containing the engineered EcoRI sites as the upstream primers, respectively, and SdhR as the downstream primer (Figure 1). To generate mutation in the CRP binding site (CGTGACCTGGATCACT to CTCTGCCTGGACTGCA, changed bases underlined), two sequential PCR steps were carried out. In the first round of PCR, the mutagenic primer SdhCRP1 (5′-GGT TTT ATC CTG AAC TGC AGT CCA GGC AGA GAT AAC AAC-3′) was used in combination with SdhF0 for the amplification of the 5′ region from the CRP binding site, while the mutagenic primer SdhCRP2 (5′-GTT GTT ATC TCT GCC TGG ACT GCA GTT CAG GAT AAA ACC -3′) was used in combination with SdhR for the amplification of the 3′ region. The two PCR products were combined and used as template in the second round of PCR with sdhF0 and SdhR as the upstream and downstream primers, respectively. The second round PCR product digested with EcoRI and BamHI was ligated into the corresponding cloning sites of pRS415 to generate pRS-sdh5. All the constructs were verified by DNA sequencing by the dideoxy method using an Applied Biosystems automated sequencer. The sdhC-lacZ fusions located on pRS-sdh0, pRS-sdh1, pRS-sdh2, pRS-sdh3, pRS-sdh4 and pRS-sdh5 were transferred onto λRZ5 (20) and then inserted into the MC4100 chromosome to generate TSDH00, TSDH10, TSDH20, TSDH30, TSDH40 and TSDH50, respectively, as described previously (19). Several independent lysogens were analyzed to obtain monolysogens.

β-Galactosidase assays

Cells were grown to A600 of 1.0, and β-galactosidase activities were measured using permeabilized cells as described previously (14). Enzymatic activities are given in units of µmol ONPG hydrolyzed per min. Average values of at least four independent samples were determined.

Detection of EIICBGlc-interacting proteins

E.coli GI698 harboring pHisEIIB was used for overexpression of His-EIIB. Cell culture and induction of protein overexpression was performed as described previously (12). Purification of His-EIIB was carried out using the BD TALON™ metal affinity resin (BD Biosciences) following the manufacturer's instructions. EIIB was purified as described previously (12). E.coli MG1655 and MG1655 Δmlc (21) cells grown in 500 ml of LB media were resuspended in the binding buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 8.1 containing 200 mM NaCl and 5 mM imidazole) in the presence of 100 µg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The cell suspensions disrupted by passing through a French press at 10 000 p.s.i. were centrifuged at 12 000 g for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant solutions were used as crude extracts. Each crude extract was used for the ligand fishing experiment to search for a protein(s) interacting with His-EIIB by employing the BD TALON™ metal affinity resin. Proteins specifically interacting with His-EIIB were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry as described previously (21). Protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce).

Gel mobility shift assay

Gel mobility shift assays were performed essentially as described previously (12). DNA fragments covering the promoter regions of sdhC and ptsG (from −183 to +156 and −264 to +180, respectively, relative to their transcription start sites) were amplified by PCR and labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by using T4 polynucleotide kinase. The DNA binding reaction mixtures in the binding buffer contained 100 µM of cAMP, 1 nM of 32P-labeled DNA fragments and indicated amounts of CRP. The binding mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 10 min and analyzed by electrophoresis on 6% polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× TBE at room temperature for 90 min.

In vitro transcription

Reactions were carried out as described previously (11) in a 20 µl total volume containing 20 mM Tris-acetate, pH 8.0, 150 mM potassium glutamate, 1 mM DTT, 3 mM MgSO4, 1 nM supercoiled DNA template pTSDHpro, 100 µM cAMP, 40 µg/ml BSA, 1 mM ATP, 100 µM each GTP and UTP, 10 µM CTP, 5 µCi of [α-32P]CTP (3000 Ci/mmol) and 0.2 U of E.coli RNA polymerase. CRP and phosphorylated ArcA were prepared as described previously (21) and added to the reaction as described in the legend to Figure 6. All components except nucleotides were incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Transcription was started by the addition of nucleotides containing 100 µg/ml of heparin and terminated after 30 min by adding 20 µl of formamide loading buffer. mRNA was electrophoresed on an 8 M urea, 5% polyacrylamide gel and visualized by autoradiography.

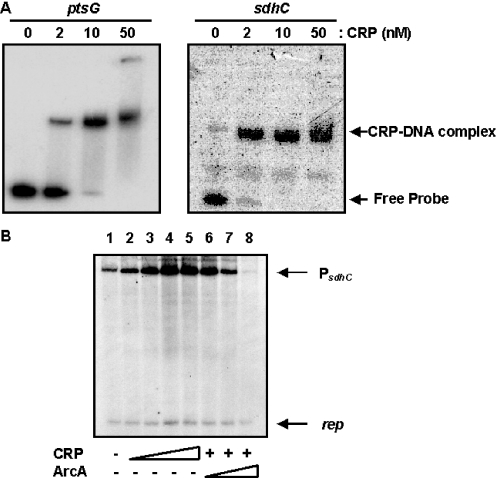

Figure 6.

CRP binds to the sdhC promoter and activates sdhCDAB expression in vitro in the presence of cAMP. (A) CRP binds to its target sites on the ptsG and sdhC promoters. 32P-labeled DNA probes containing the ptsG or sdhC promoter regions were mixed with the indicated CRP concentrations in the presence of 100 µM cAMP and then electrophoresed on 6% polyacrylamide gels. (B) The effect of CRP·cAMP and ArcA on sdhCDAB transcription in vitro. The supercoiled DNA template, pTSDHpro, was used for the in vitro transcription. The templates were preincubated with RNA polymerase and CRP and/or ArcA as described under ‘Materials and Methods.’ The reaction was started and stopped by the addition of NTP solution containing heparin and loading dye, respectively, and analyzed on a 5% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 M urea. Lanes 2–5 contain 5, 10, 20 and 40 nM CRP in the reaction, respectively; lanes 6–8 contain 100, 200 and 400 nM ArcA with 40 nM CRP in the reaction, respectively. The transcripts from the plasmid origin of replication (106/107 nt) are marked as rep. The 248 nt transcript from sdhC promoter is indicated.

Western blot analysis

The phosphorylation state of EIIAGlc was determined according to the procedure developed by Takahashi et al. (22). Cell culture (0.2 ml at A600 = 1.0) was quenched by adding 20 µl of 10 M NaOH followed by vortexing for 10 s, and then 180 µl of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 1 ml of ethanol were added. Samples were chilled at −70°C for at least 15 min, thawed and centrifuged at 4°C. The pellet was rinsed with 70% ethanol and resuspended in 100 µl of the SDS sample buffer, and 20 µl of this solution was analyzed by 15% SDS–PAGE. Proteins were then electrotransferred onto immobilin-P (Millipore, MA) following the manufacturer's protocol and were detected with immunoblotting using antiserum against EIIAGlc raised in mice as described previously (5). The protein bands were visualized by using the SuperSignal West Pico kit (Pierce) following the manufacturer's instructions. The amounts of phosphorylated EIIAGlc were quantified by densitometric tracing of the film using Eagle Eye™ II and Eagle sight software version 3.2 (Stratagene). To detect the intracellular levels of CRP, growing cells were taken at A600 of 1.0 and total cellular proteins were analyzed by SDS–PAGE using a 15% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were then electrotransferred onto immobilin-P and western blot analysis was carried out using polyclonal antibody raised in mice against CRP. The protein bands were visualized by using the SuperSignal West Pico kit (Pierce) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Measurement of intracellular cAMP concentrations

Intracellular cAMP concentrations were measured as described previously (23) with some modifications after cells were grown to an A600 of 1.0. Cells from 1 ml culture were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 500 µl of the cell lysis buffer provided with the cAMP enzyme immunoassay system (Amersham Biosciences). After boiling cell suspensions in lysis buffer for 15 min and centrifugation, the cAMP concentrations in supernatants were determined by using the kit. The average intracellular cAMP concentration was expressed in femtomoles per 109 cells assuming an A600 of1.0 corresponds to 8 × 108 cells/ml (24). Average values of four independent cultures were determined.

RESULTS

Deletion of the glucose-specific PTS genes affects the glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression

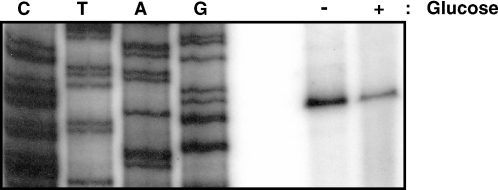

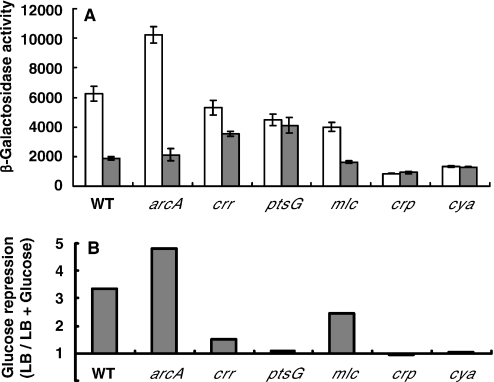

Although CRP and Cra are well-characterized global transcription factors regulating carbon catabolite repression of more than 100 genes, they have been dismissed from the glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression (7). To elucidate the mechanism of sdhCDAB repression by glucose, we first tested whether the glucose repression occurs at the transcriptional level or post-transcriptionally. Expression from the sdhC promoter was monitored by primer extension assay of the total RNA extracted from E.coli MG1655 cells grown in the presence or absence of glucose. The level of the sdhC transcript from the cells grown in the absence of glucose was much higher than that of cells grown in the presence of glucose (Figure 2). Since this result indicated that the glucose effect on sdhCDAB occurs at the transcriptional level, we constructed a series of transcriptional sdhC-lacZ fusion strains. The strain TSDH00 contains a single copy of the sdhC-lacZ transcriptional fusion gene in which sdhC promoter region extends from −312 to +450 relative to the transcription start site (Figure 1). Growth in the presence of glucose caused ∼3.4-fold decrease in sdhC-lacZ expression when compared with growth without glucose (Figure 3) in agreement with the mRNA level determined by the primer extension assays in Figure 2 and previous reports (7,10). As the ArcA anaerobic repressor is known to serve as the major transcriptional regulator of the sdhCDAB operon, we monitored the effect of arcA deletion on the glucose repression of sdhC-lacZ expression. While deletion of the arcA gene resulted in increase of sdhC-lacZ expression as expected from the previous reports (6,7,9,10), it did not show any remarkable effect on the glucose repression of sdhC-lacZ expression. As a previous study had shown that the glucose repression of sdhC-lacZ expression is ptsG-dependent (10), we tested the effect of the two glucose-specific PTS genes, crr and ptsG encoding EIIAGlc and EIICBGlc, respectively, on sdhC-lacZ expression. Deletion mutations of crr and ptsG were transduced into the TSDH00 strain to generate strains TSDH02 and TSDH03, respectively, and β-galactosidase activities of these strains were measured. As shown in Figure 3, the glucose repression was negligible in the crr deletion mutant when compared with wild type: growth of the TSDH02 strain in LB with glucose resulted in only a marginal decrease (∼1.5 fold) of sdhC-lacZ expression when compared with that without glucose. Deletion of ptsG resulted in the complete loss of glucose repression of sdhC-lacZ expression in agreement with the previous study (10). Loss of glucose repression of sdhC-lacZ expression in TSDH02 and TSDH03 implies that the glucose-specific PTS proteins play crucial roles in the glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression.

Figure 2.

Primer extension analysis of the sdhC transcript indicates that the glucose repression occurs at the transcriptional level. Total RNA was isolated from E.coli MG1655 cells grown in LB medium or LB medium supplemented with 40 mM glucose under aerobic condition. Primer extension analysis was carried out as described under ‘Materials and Methods.’ Lanes C, T, A and G show the DNA sequencing reaction products from the corresponding region within the sdhC regulatory region using the same primer.

Figure 3.

Effect of glucose in the medium on sdhC-lacZ expression in the strain TSDH00 and its isogenic mutants. (A) Relative levels of sdhC-lacZ expression. TSDH00 (WT) and its indicated mutant derivatives, each carrying the sdhC-lacZ transcriptional fusion gene on their chromosome, were grown in LB medium or LB medium supplemented with 40 mM glucose under aerobic conditions, and β-galactosidase activities were measured as described under ‘Materials and Methods.’ The shaded and open bars indicate β-galactosidase activities in Miller units in cells grown in LB medium with and without glucose, respectively. Activities represent the average of at least four independent experiments. (B) Glucose repression of sdhC-lacZ expression presented as the ratio of β-galactosidase activities in cells grown in LB to those in cells grown in LB + glucose.

In agreement with the previous study by Takeda et al. (10), the results in Figure 3 demonstrate the complete loss of the glucose repression of sdhC-lacZ expression in ptsG mutant. It was previously shown that the induction of ptsG and ptsHIcrr expression by glucose was also ptsG-dependent, and various studies showed that Mlc is the repressor responsible for this glucose induction (18,25–28). Further studies revealed that the dephospho-form of EIICBGlc could sequester the global repressor Mlc through the direct protein–protein interaction and induce expression of the Mlc regulon (11–13). Thus, the simplest model that could account for the glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression and its dependence on ptsG was the existence of a transcription regulator interacting with EIICBGlc and repressing the expression of the sdhCDAB operon in the presence of glucose. To search for a protein(s) interacting with EIICBGlc and thus mediating the glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression, we carried out a ligand fishing experiment. When the crude extracts prepared from MG1655 and its isogenic mlc mutant were mixed with EIIB or 6His-tagged form of EIIB (His-EIIB) and subjected to pull-down assays using the BD TALON™ metal affinity resin, we could not find out any proteins other than Mlc that specifically interacted with the glucose-sensing EIIB domain of the ptsG gene product (data not shown). Although it is well established that Mlc is the global transcription repressor regulating expression of many genes in response to the presence of glucose, the possibility that Mlc may participate in the glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression was ruled out as the mlc null mutant, TSDH04, still exhibited the glucose repression of sdhC-lacZ expression (Figure 3), in agreement with a previous report (10).

Regulation of sdhCDAB expression by the CRP·cAMP complex

Considering the fact that only Mlc, which is known to exist in a very limiting concentration in E.coli (18,25), could be fished out from the crude extract of MG1655 using EIIB as bait (data not shown), we assumed that the glucose repression of the sdhCDAB operon might not involve any transcription regulators interacting with EIICBGlc in E.coli and that the effect of ptsG on the glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression might be indirect.

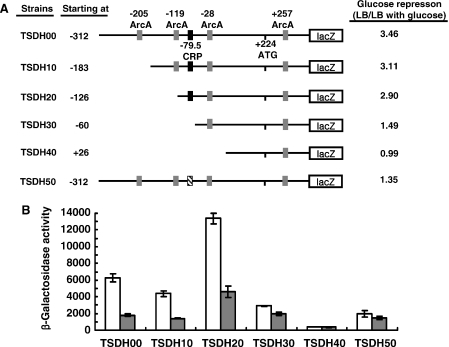

To search for the cis-acting region(s) responsible for regulation of the glucose repression of the sdhCDAB operon, a series of single-copy transcriptional lacZ fusion constructs containing various promoter regions of sdhC were generated and introduced into the E.coli strain MC4100. The glucose repression of sdhC expression in TSDH00 and four different 5′ deletion constructs of sdhC-lacZ fusion, TSDH10, TSDH20, TSDH30 and TSDH40, was monitored in cultures grown aerobically in the presence or absence of glucose (Figure 4). Disruption of the upstream ArcA site centered at −205 bp relative to the transcription start site (the TSDH10 strain) modestly reduced the level of aerobic gene expression as previously reported (9), while deletion of the DNA region containing the ArcA site centered at −119 elevated the level of aerobic sdhC-lacZ expression (TSDH20 strain). Regardless of the changes in the aerobic sdhC-lacZ expression levels, both the promoter fusions TSDH10 and TSDH20 still exhibited the glucose repression of sdhC-lacZ expression to significant levels similar to wild-type TSDH00 (Figure 4). On the construct TSDH30, lacZ was fused to the region covering from −60 to +450 bp relative to the sdhC transcription start, and thus the presumed CRP-binding site centered at −79.5 (29) was deleted but it still retains the ArcA binding site centered at −28 (9). This construct resulted in the significant reduction of β-galactosidase activity and growth of the TSDH30 strain in LB with glucose resulted in only a marginal decrease (1.49 fold) of sdhC-lacZ expression when compared with growth without glucose (Figure 4). These results indicate that the factor mediating the glucose repression may bind to the region extending from −126 to −60 relative to the transcription start site of the sdhC promoter, where the presumed CRP-binding site is located (29) (Figures 1 and 4). Since it was reported that the crp deletion mutant cell still showed the glucose repression of sdhC-lacZ expression (7), it had been believed that a regulator other than CRP would be responsible for the glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression (10). The promoter deletion experiments in this study, however, led us to speculate that CRP may be the direct regulator of the glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression. Therefore, we mutated the putative CRP binding site centered at −79.5 to check whether it is directly involved in the glucose repression of sdh expression. TSDH50, which contains a single copy of the sdhC-lacZ transcriptional fusion gene with mutated CRP binding site (CGTGACCTGGATCACT to CTCTGCCTGGACTGCA), resulted in the significant reduction of β-galactosidase activity and almost complete loss of the glucose repression of lacZ expression similar to the TSDH30 strain (Figure 4). From these results, we concluded that the CRP binding site on the sdhC promoter region is directly involved in the glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression.

Figure 4.

5′ Deletion analysis of the sdhC promoter region. Each construct was inserted into the MC4100 chromosome and monolysogens were selected and grown in LB media with or without glucose to search for the cis-acting region(s) responsible for regulation of the glucose repression of the sdhCDAB operon. (A) 5′ Deletion constructs of the transcriptional sdhC-lacZ fusions. Four ArcA binding sites, one CRP binding site and the translation start site are schematically shown. Mutated CRP binding site on TDH50 is shown as hatched box. The numbers refer to the nucleotide positions relative to the transcription start site of sdhC. Effect of glucose on sdhC expression is presented on the right side of each construct as the ratio of β-galactosidase activities in cells grown in LB to those in cells grown in LB with glucose. (B) β-Galactosidase activities of 5′ deletion constructs of the sdhC-lacZ fusion. Cells harboring each fusion construct were aerobically grown in LB medium or LB medium supplemented with 40 mM glucose, and β-galactosidase activities were measured as described above. Values represent the average of at least four independent determinations ± SD.

The involvement of CRP and cAMP on the glucose repression of sdhC expression was further investigated using two deletion mutants lacking either CRP or cAMP production. Cells of the crp mutant strain, SA2777, were used to generate an isogenic crp deletion mutant of the parental strain TSDH00 by P1 transduction. After crp deletion was confirmed by western blot analysis using anti-CRP polyclonal antibody in this strain, TSDH05 (data not shown), β-galactosidase activities were measured in TSDH05 cells grown in LB media in the presence and absence of glucose. Contrary to the previous report, the glucose repression was completely abolished in this mutant strain (compare data for the crp mutant with wild type in Figure 3A and B). The sdhC-lacZ expression of TSDH05 grown in LB was even lower than that of wild-type cells grown in the presence of glucose, indicating that CRP is directly involved in the regulation of sdhCDAB expression. To determine whether the glucose repression of sdhC-lacZ expression is dependent on cAMP, an isogenic cya deletion mutant of TSDH00 was also generated by P1 transduction from the CA8000Δcya strain (30). The sdhC-lacZ expression in this mutant strain TSDH06 showed a similar pattern with that of TSDH05 and was not affected by the presence of glucose (cya mutant in Figure 3). From these results, we concluded that the CRP·cAMP complex is one of the major transcriptional regulators of the sdhCDAB operon and it is directly involved in the glucose repression of sdhCDAB.

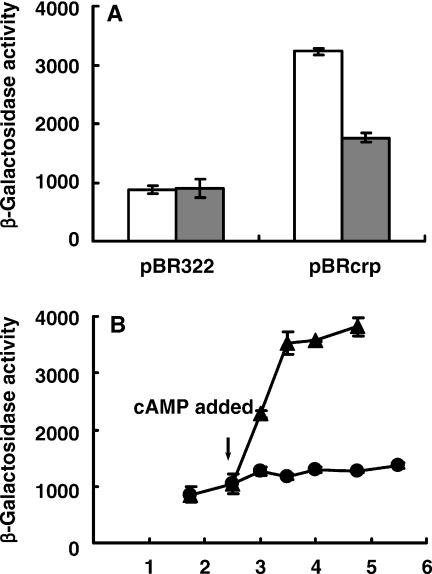

To confirm the direct involvement of CRP and cAMP in the glucose repression of the sdhCDAB operon, we tested the effect of episomally expressed CRP and cAMP added in the medium on sdhC-lacZ expression in the two mutant cells. The genomic DNA fragment containing the crp gene including its own promoter was cloned into the low copy number plasmid pBR322, and the product pBRcrp was transformed into the crp deletion mutant to see whether the glucose repression phenotype is recovered. The episomal expression of CRP increased the sdhC-lacZ expression in TSDH05 cells and the TSDH05 cells transformed with pBRcrp showed the glucose-dependent repression of sdhC-lacZ expression (Figure 5A). The sdhC-lacZ expression of TSDH05 cells harboring pBRcrp grown in the absence of glucose showed ∼1.8-fold higher β-galactosidase activity than that of cells grown in the presence of glucose, while TSDH05 cells harboring pBR322 showed the lower β-galactosidase activity regardless of the presence of glucose. These results suggest that elimination of the glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression in TSDH05 resulted from the failure of activation of gene expression by CRP. Inducibility of the sdhC promoter by cAMP was also investigated in the cya mutant strain (Figure 5B). The sdhC-lacZ expression level in TSDH06 cells was not significantly changed during the cell growth (filled circles). When 1 mM of cAMP was added to the growth medium, however, the sdhC-lacZ expression of TSDH06 cells was increased to ∼3-fold within 1 h. These results support that intracellular cAMP production as well as crp expression plays a crucial role in the regulation of sdhCDAB expression.

Figure 5.

Restoration of sdhC-lacZ expression by the addition of cAMP and episomal expression of CRP in the cya and crp mutants, respectively. (A) Complementation of the crp mutation phenotype on sdhC-lacZ expression by episomally expressed CRP. The open bars represent the sdhC-lacZ expression in the TSDH05 (Δcrp) strain harboring pBRcrp grown in LB and the shaded bars represent that in LB supplemented with glucose (40 mM). The TSDH05 strain harboring pBR322 was used as a control. (B) Addition of cAMP in growing medium increases the expression of sdhC-lacZ in cya mutant cells. Freshly grown TSDH06 (Δcya) cells were inoculated into LB medium. After incubation for 2.5 h (marked with arrow) under aerobic condition at 37°C, cAMP (1 mM) was added to the medium (triangle), β-galactosidase activities were determined in cells taken at the indicated times and compared with those in cells grown without addition of cAMP (circle).

The CRP·cAMP complex binds to the sdhC promoter and regulates transcription in vitro

To show the direct binding of the CRP·cAMP complex to the sdhC promoter in vitro, gel shift assays were carried out using purified CRP and the sdhC promoter fragment in the presence of cAMP. The results showed that CRP·cAMP specifically binds to the sdhC promoter (Figure 6A). As the amount of CRP added in the reaction mixture increased, the amount of the CRP–promoter DNA complex also increased. Binding affinity of the CRP·cAMP complex toward the sdhC promoter was comparable with that toward the ptsG promoter.

To investigate the effect of CRP·cAMP binding to the promoter on sdhCDAB transcription, the in vitro transcription assay was performed with a supercoiled DNA template (pTSDHpro) containing base pairs −183 to +209 relative to the transcription start site, covering the sdhC promoter and its CRP and ArcA binding sites. When RNA polymerase alone was present in the reaction, transcription from the sdhC promoter did not occur efficiently (Figure 6B, lane 1). The addition of CRP and cAMP, however, remarkably increased the promoter activity (Figure 6B, lanes 2–5). Most intriguingly, incubation of the reaction mixture with ArcA-P repressed the CRP-activated promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6B, lanes 6–8). The specificity of CRP·cAMP function in sdhCDAB transcription was confirmed by the consistent activity of rep that originates from replication origin of the DNA template regardless of the presence of CRP and ArcA-P. These data confirm that the CRP·cAMP complex affects the sdhCDAB transcription initiation and is directly involved in the glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression.

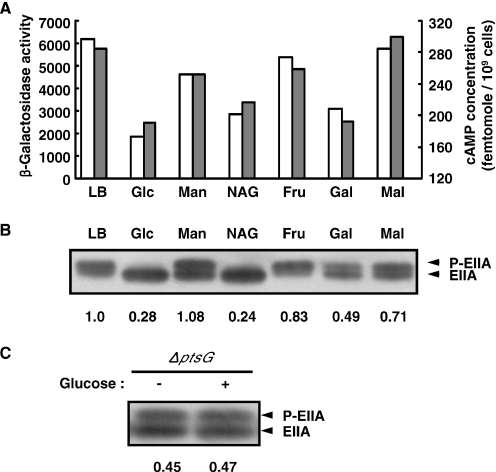

The level of phosphorylated EIIAGlc correlates with the intracellular cAMP concentration and sdhC-lacZ expression

It was reported that expression of sdhC-lacZ varied depending on the type of carbon source added in the medium (7). From the above results, it could be assumed that the different expression levels of sdhC-lacZ on various sugars might result from the change in the intracellular cAMP concentration depending on the type of carbon source. To verify this assumption, the relationship between the intracellular cAMP concentrations and β-galactosidase activities was determined in TSDH00 cells grown in LB with various carbon sources. β-Galactosidase activities of TSDH00 revealed the carbon source-dependent expression of sdhC-lacZ (Figure 7A). Growth with mannose, fructose or maltose did not affect the expression level of sdhC-lacZ, while N-acetylglucosamine and galactose showed the similar effect with glucose on sdhC-lacZ expression. To investigate the effect of cAMP on sdhC-lacZ expression, the levels of intracellular cAMP were also measured (Figure 7A). The intracellular cAMP level in TSDH00 cells decreased when glucose was added to the medium, in agreement with the previous reports [reviewed in (1)]. The intracellular cAMP level in cells grown on glucose, N-acetylglucosamine or galactose was lower than that in cells grown on mannose, fructose or maltose. The result showed that carbon source-dependent expression of sdhC-lacZ is in accordance with the intracellular cAMP concentration. Although the mechanism for the regulation of the intracellular cAMP level is not fully understood, a popular model for the regulation of adenylate cyclase activity is that phosphorylated EIIAGlc stimulates adenylate cyclase activity and increases the intracellular cAMP concentration (1). Therefore, we measured the level of EIIAGlc phosphorylation in the cells grown with various carbon sources by western blot analysis according to the procedure developed by Takahashi et al. (22) as described under ‘Materials and Methods’ (Figure 7B). It is well established that phosphorylated EIIAGlc migrates slower than the dephosphorylated form on an SDS–polyacrylamide gel (22). The data in Figure 7A and B show that there is a general correlation between the level of EIIAGlc phosphorylation and the intracellular cAMP concentration in the cells grown on each carbon source: the level of phosphorylated EIIAGlc in cells grown with glucose, N-acetylglucosamine or galactose was lower than that in cells grown with mannose, fructose or maltose (Figure 7B). Taken together with above results, this result led us to the conclusion that the different phosphorylation state of EIIAGlc on each sugar reflects the different cAMP concentration in the cell, and consequently the different sdhCDAB expression level depending on the type of carbon source added to the medium. From these facts, it could be predicted that the ptsG gene plays an indirect role and the crr gene product is the major determinant on the glucose repression of sdhC expression. It could be assumed that the level of EIIAGlc phosphorylation may be unaffected by glucose in the ptsG mutant because EIIAGlc cannot pass the phosphate group on to EIICBGlc. To verify this, we measured the level of EIIAGlc phosphorylation in ptsG cells. As shown in Figure 7C, glucose in the growth medium did not affect the phosphorylation state of EIIAGlc in the ptsG mutant cells. Based on these results, it is assumed that the loss of glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression in the ptsG mutant results from the lack of glucose-dependent regulation of the EIIAGlc phosphorylation state in the mutant that affects the level of intracellular cAMP.

Figure 7.

The phosphorylation level of EIIAGlc correlates with the intracellular cAMP concentration and the sdhC-lacZ expression level. (A) Samples from exponentially growing cultures of the TSDH00 in LB or LB containing indicated sugars (40 mM) were taken and β-galactosidase activities (open bars) and cAMP concentrations (shaded bars) were determined as described above. (B) Using the same samples, the phosphorylation states of EIIAGlc were determined by western blot analysis as described under ‘Materials and Methods.’ Amounts of the phosphorylated EIIAGlc were quantitated using an image analyzer, and ratios compared with the sample from cells grown in LB are shown below the protein bands. (C) Western blot analysis indicates that the phosphorylation state of EIIAGlc is not affected by the presence of glucose in the ptsG mutant. Ratios of the amount of phosphorylated EIIAGlc compared with the sample from wild-type cells grown in LB are indicated below the protein bands.

DISCUSSION

It was reported that activities of E.coli TCA cycle enzymes such as succinate dehydrogenase are remarkably reduced during anaerobiosis and in the presence of glucose in the medium almost 40 years ago (31). The recent studies in the transcriptomic and proteomic levels also revealed that the genes involved in the TCA cycle are strongly repressed by glucose and/or anaerobiosis (32–34). While the mechanism underlying the anaerobic repression of sdhCDAB was well documented in previous studies (7,9), the mechanism of the glucose repression of sdhCDAB expression still remains as a puzzling issue.

Although CRP was excluded from the regulatory circuit of sdhCDAB expression (7), several reasons prompted us to re-consider the CRP·cAMP complex as the direct mediator of the glucose repression of sdhCDAB: (i) the CRP·cAMP complex has been established as the major regulator of the glucose-mediated carbon catabolite repression of more than 100 genes (1); (ii) a putative CRP-binding site was proposed to be located on the sdhC promoter region (29) (Figure 1), although binding of CRP to the promoter has never been demonstrated; (iii) we could not find any transcription regulators other than Mlc that interact with the glucose-sensing EIIB domain of the ptsG gene product (data not shown), while it was shown that the ptsG gene acts as a crucial mediator of the glucose repression of the sdhCDAB operon (10). Furthermore, the mlc mutant still showed the glucose repression of sdhCDAB (10) (Figure 3); (iv) in a previous review, it was proposed that catabolite repression of the sdhCDAB operon is controlled presumably by the CRP·cAMP complex (35). (v) Finally, recent reports on the transcriptome analyses of the crp mutant using microarray techniques indicated that expression of the sdhCDAB operon was affected by deletion of the crp gene (36,37). It was proposed that the sdhCDAB operon might actually be regulated by the CRP homologue Fnr in vivo (37), based on the facts that Fnr has been shown to regulate sdhCDAB expression in response to anaerobiosis (7), the consensus sequence for Fnr is similar to that for CRP, and both proteins can bind to the DNA site for the other protein (38).

From the results in this study, it is evident that CRP is directly involved in the regulation of sdhCDAB expression and the glucose repression of sdhCDAB occurs in a cAMP-dependent manner. Genetic studies using cya and crp mutants and the sdhC-lacZ fusion strain harboring the mutated crp binding site on the sdhC promoter region suggest that both cAMP and CRP are required for sdhCDAB expression and its glucose repression (Figures 3–5). In vitro studies demonstrate binding of CRP to the sdhC promoter and activation by the CRP·cAMP complex of sdhC transcription (Figure 6). Furthermore, the phosphorylation level of EIIAGlc in cells grown with different carbon sources correlates with the intracellular concentration of cAMP and the sdhC-lacZ expression level (Figure 7). It was previously reported that the phosphorylation level of EIIAGlc is dependent on the type of carbon source in the medium (39). Although no biochemical evidence has been provided, it is generally believed that the phosphorylated form of EIIAGlc stimulates adenylate cyclase activity (1). In the presence of glucose, N-acetylglucosamine or galactose in the medium, the level of the phospho-form of EIIAGlc decreased (Figure 7B). This decrease seems to be responsible for reduced activity of adenylate cyclase and reduced production of cAMP required to activate sdhCDAB expression after binding to its receptor protein CRP. Thus, we conclude that the CRP·cAMP complex mediates the glucose repression of the sdhCDAB operon. There still remains one question why the ptsG mutant exerts a more profound effect than mutation of crr on the glucose repression of the sdhCDAB promoter (Figure 3), that is in conflict with our conclusion that the crr gene product EIIAGlc is the major regulator in orchestrating glucose repression of the sdhCDAB promoter. One possibility for this conflict may be due to the pleiotropic effect of the ptsG and crr mutants on expression of many genes expected from the fact that both EIICBGlc and EIIAGlc interact with and regulate activities of many regulatory proteins (1,5,11–13). More studies need to be carried out to fully understand this question.

Under fully aerobic conditions, the TCA cycle in E.coli operates as an oxidative pathway that needs the activities of succinate dehydrogenase, encoded by sdhCDAB, and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. In the presence of readily fermentable sugars and/or under anaerobic conditions, however, the TCA cycle hardly operates in an oxidative way because coupling of the pathway to terminal respiration is absolutely required to maintain the activities of the succinate dehydrogenase complex and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex that produce FADH2 and NADH, respectively. On the other hand, the reactions that make oxaloacetate, succinyl-coenzyme A and α-ketoglutarate are necessary because these intermediates are still required for the biosynthesis of amino acids and tetrapyrroles. Under these conditions, the TCA cycle is converted from an oxidative and cyclic into a reductive and branched pathway to solve the problem. In the reductive pathway, succinyl-coenzyme A is made by reversing the reactions between oxaloacetate and succinyl-coenzyme A, using the enzyme fumarate reductase instead of succinate dehydrogenase (40). Thus, the decreased sdhCDAB expression by carbon catabolite repression in the presence of glucose provides one of the mechanisms to maintain the TCA cycle in a reductive pathway, leading to accumulation of succinate and succinyl-coenzyme A (41). The sdhCDAB operon in this study is not the first example of genes encoding the TCA cycle enzymes whose expression are activated by CRP and repressed by ArcA and Fnr. The acnB, encoding one of the two aconitases differentially expressed in E.coli, has been shown to be regulated in the same way as the sdhCDAB operon (42). Intriguingly, expression of both fumA and sdhCDAB was recently shown to be down-regulated by the small RNA, RyhB (8). Expression of the fumA and fumC genes encoding two fumarase isozymes of the TCA cycle in E.coli was also shown to be subject to the glucose repression and require cAMP (43). Thus, decrease in the CRP·cAMP level in the presence of readily fermentable glucose seems to be responsible for the reduced expression of genes encoding enzymes necessary to maintain the TCA cycle in an oxidative pathway and conversion of the cycle into a reductive pathway.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Korea Research Foundation Grant (KRF-2004-015-C00480) and the 21C Frontier Microbial Genomics and Applications Center Program (Grant MG05-0202-6-0), Republic of Korea. T.-W.N. and Y.-H.P. were supported by BK21 Research Fellowships from the Korean Ministry of Education and Human Resources Development. The authors thank Dr A. Peterkofsky for his generous gifts of strains and plasmids. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Korea Research Foundation.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Postma P.W., Lengeler J.W., Jacobson G.R. Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 1993;57:543–594. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.543-594.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saier M.H., Jr, Ramseier T.M., Reizer J. Regulation of carbon utilization. In: Neidhardt F.C., editor. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: Cellular and Molecular Biology. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1149–1174. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurley J.H., Faber H.R., Worthylake D., Meadow N.D., Roseman S., Pettigrew D.W., Remington S.J. Structure of the regulatory complex of Escherichia coli IIIGlc with glycerol kinase. Science. 1993;259:673–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brückner R., Titgemeyer F. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: choice of the carbon source and autoregulatory limitation of sugar utilization. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2002;209:141–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koo B.-M., Yoon M.-J., Lee C.-R., Nam T.-W., Choe Y.-J., Jaffe H., Peterkofsky A., Seok Y.-J. A novel fermentation/respiration switch protein regulated by enzyme IIAGlc in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:31613–31621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405048200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iuchi S., Aristarkhov A., Dong J.M., Taylor J.S., Lin E.C. Effects of nitrate respiration on expression of the Arc-controlled operons encoding succinate dehydrogenase and flavin-linked L-lactate dehydrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:1695–1701. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.6.1695-1701.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park S.-J., Tseng C.-P., Gunsalus R.P. Regulation of succinate dehydrogenase (sdhCDAB) operon expression in Escherichia coli in response to carbon supply and anaerobiosis: role of ArcA and Fnr. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;15:473–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masse E., Gottesman S. A small RNA regulates the expression of genes involved in iron metabolism in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:4620–4625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032066599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen J., Gunsalus R.P. Role of multiple ArcA recognition sites in anaerobic regulation of succinate dehydrogenase (sdhCDAB) gene expression in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1997;26:223–236. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5561923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeda S.-I., Matsushika A., Mizuno T. Repression of the gene encoding succinate dehydrogenase in response to glucose is mediated by EIICBGlc protein in Escherichia coli. J. Biochem. 1999;126:354–360. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee S.J., Boos W., Bouche J.P., Plumbridge J. Signal transduction between a membrane-bound transporter, PtsG, and a soluble transcription factor, Mlc, of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 2000;19:5353–5361. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nam T.-W., Cho S.-H., Shin D., Kim J.-H., Jeong J.-Y., Lee J.-H., Roe J.-H., Peterkofsky A., Kang S.-O., Ryu S., Seok Y.-J. The Escherichia coli glucose transporter enzyme IICBGlc recruits the global repressor Mlc. EMBO J. 2001;20:491–498. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka Y., Kimata K., Aiba H. A novel regulatory role of glucose transporter of Escherichia coli: membrane sequestration of a global repressor Mlc. EMBO J. 2000;19:5344–5352. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller J.H. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy P., Peterkofsky A., McKenney K. Hyperexpression and purification of Escherichia coli adenylate cyclase using a vector designed for expression of lethal gene products. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:10473–10488. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.24.10473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu P.P., Nosworthy N., Ginsburg A., Miyata M., Seok Y.-J., Peterkofsky A. Expression, purification, and characterization of enzyme IIAglc of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system of Mycoplasma capricolum. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6947–6953. doi: 10.1021/bi963090m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryu S., Garges S. Promoter switch in the Escherichia coli pts operon. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:4767–4772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim S.-Y., Nam T.-W., Shin D., Koo B.-M., Seok Y.-J., Ryu S. Purification of Mlc and analysis of its effects on the pts expression in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:25398–25402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simons R.W., Houman F., Kleckner N. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostrow K.S., Silhavy T.J., Garret S. Cis-acting sites required for osmoregulation of ompF expression in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1986;168:1165–1171. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1165-1171.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeong J.-Y., Kim Y.-J., Cho N., Shin D., Nam T.-W., Ryu S., Seok Y.-J. Expression of ptsG encoding the major glucose transporter is regulated by ArcA in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:38513–38518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406667200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi H., Inada T., Postma P., Aiba H. CRP down-regulates adenylate cyclase activity by reducing the level of phosphorylated IIAGlc, the glucose specific phosphotransferase protein in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1998;259:317–326. doi: 10.1007/s004380050818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma Z., Richard H., Foster J.H. pH-dependent modulation of cyclic AMP levels and GadW-dependent repression of rpoS affect synthesis of the GadX regulation and Escherichia coli acid resistance. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:6852–6859. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.23.6852-6859.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis L.G., Kuehl M., Battey J. Basic Methods in Molecular Biology. London: Prentice-Hall International Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimata K., Inada T., Tagami H., Aiba H. A global repressor (Mlc) is involved in glucose induction of the ptsG gene encoding major glucose transporter in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;29:1509–1519. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plumbridge J. Expression of ptsG, the gene for the major PTS transporter in Escherichia coli, is repressed by Mlc and induced by growth on glucose. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;29:1053–1063. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plumbridge J. Expression of the phosphotransferase system (PTS) both mediates and is mediated by Mlc regulation in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 1999;33:260–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka Y., Kimata K., Inada T., Tagami H., Aiba H. Negative regulation of the pts operon by Mlc: mechanism underlying glucose induction in Escherichia coli. Genes Cells. 1999;4:391–399. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilde R., Guest J.R. Transcript analysis of the citrate synthase and succinate dehydrogenase genes of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1986;132:3239–3251. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-12-3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah S., Peterkofsky A. Characterization and generation of Escherichia coli adenylate cyclase deletion mutants. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:3238–3242. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.10.3238-3242.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray C.T., Wimpenny J.W., Hughes D.E., Mossman M.R. Regulation of metabolism in facultative bacteria. I. Structural and functional changes in Escherichia coli associated with shifts between the aerobic and anaerobic states. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1966;117:22–32. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(66)90148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh M.K., Rohlin L., Kao K.C., Liao J.C. Global expression profiling of acetate-grown Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:13175–13183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110809200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonzalez R., Tao H., Shanmugam K.T., York S.W., Ingram L.O. Global gene expression differences associated with changes in glycolytic flux and growth rate in Escherichia coli during the fermentation of glucose and xylose. Biotechnol. Prog. 2002;18:6–20. doi: 10.1021/bp010121i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng L., Shimizu K. Global metabolic regulation analysis for Escherichia coli K12 based on protein expression by 2-dimensional electrophoresis and enzyme activity measurement. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003;61:163–178. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cecchini G., Schroder I., Gunsalus R.P., Maklashina E. Succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate reductase from Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1553:140–157. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(01)00238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gosset G., Zhang Z., Nayyar S., Cuevas W.A., Saier M.H., Jr Transcriptome analysis of Crp-dependent catabolite control of gene expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:3516–3524. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3516-3524.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng D., Constantinidou C., Hobman J.L., Minchin S.D. Identification of CRP regulon using in vitro and in vivo transcriptional profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;132:5874–5893. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sawers G., Kaiser M., Sirko A., Freundlich M. Transcriptional activation by FNR and CRP: reciprocity of binding-site recognition. Mol. Microbiol. 1997;23:835–845. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2811637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hogema B.M., Arents J.C., Bader R., Eijkemans K., Yoshida H., Takahashi H., Aiba H., Postma P.W. Inducer exclusion in Escherichia coli by non-PTS substrates: the role of the PEP to pyruvate ratio in determining the phosphorylation state of enzyme IIAGlc. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;30:487–498. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ingledew W.J., Poole R.K. The respiratory chains of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 1984;48:222–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.48.3.222-271.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alam K.Y., Clark D.P. Anaerobic fermentation balance of Escherichia coli as observed by in vivo nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:6213–6217. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.11.6213-6217.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cunningham L., Gruer M.J., Guest J.R. Transcriptional regulation of the aconitase genes (acnA and acnB) of Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1997;143:3795–3805. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-12-3795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tseng C.-P., Yu C.-C., Lin H.-H., Chang C.-Y., Kuo J.-T. Oxygen- and growth rate-dependent regulation of Escherichia coli fumarase (FumA, FumB, and FumC) activity. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:461–467. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.2.461-467.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blattner F.R., Plunkett G.T., Bloch C.A., Perna N.T., Burland V., Riley M., Collado-Vides J., Glasner J.D., Rode C.K., Mayhew G.F., et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silhavy T., Besman M., Enquist L. Experiments with Gene Fusions. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1984. pp. xi–xii. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Iuchi S., Furlong D., Lin E.C. Differentiation of arcA, arcB, and cpxA mutant phenotypes of Escherichia coli by sex pilus formation and enzyme regulation. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:2889–2893. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2889-2893.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levy S., Zeng G.-Q., Danchin A. Cyclic AMP synthesis in Escherichia coli strains bearing known deletions in the pts phosphotransferase operon. Gene. 1990;86:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90110-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sambrook J., Russell D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]