Abstract

Fructans, a family of oligo- and polyfructoses, are implicated to play a drought-protecting role in plants. Inulin-type fructan is able to preserve the membrane barrier during dehydration. However, whether other fructans would be able to perform this function is unknown. In addition, almost nothing is known about the organization of these systems, which could give insight into the protective mechanism. To get insight into these questions the effect of different fructans on phosphatidylcholine-based model systems under conditions of dehydration was analyzed. Using a vesicle leakage assay, it was found that both levan- and inulin-type fructans protected the membrane barrier. This suggests that fructans in general would be able to protect the membrane barrier function. Furthermore, both fructan-types inhibited vesicle fusion to a large extent as measured using a lipid-mixing assay. Using x-ray diffraction, it was found that in the presence of both inulin- and levan-type fructans the lamellar repeat distance increased considerably. From this it was concluded that fructans are present between the lipid bilayers during drying. Furthermore, they stabilize the Lα phase. In contrast to fructans, dextran did not increase the lamellar repeat distance and it even promoted Lβ phase formation. These data support the hypothesis that fructans can have a membrane-protecting role during dehydration, and give insight into the mechanism of protection.

INTRODUCTION

Fructans are a group of fructose-based oligo- and polysaccharides. Based on the glycosidic linkage between the fructose units, they are divided into different classes: inulins, containing exclusively β(2→1) linkages; levans, containing mainly β(2→6) linkages; and graminans, containing both linkage types. Fructans function as carbohydrate storage compounds in plants. However, evidence is accumulating that fructans could also have a drought-protecting role (Hendry, 1993; Pontis, 1989). A strong argument is that transgenic tobacco plants, which accumulate levan, show enhanced drought tolerance compared to the wild-type control plants (Konstantinova et al., 2002; Pilon-Smits et al., 1995). Since membranes are one of the primary targets of both freezing and desiccation injury of cells (Crowe et al., 1992; Senaratna et al., 1984), it was hypothesized that fructans would protect plants against drought through direct interaction with cellular membranes (Demel et al., 1998). The first indications in support of this hypothesis were found in vitro, showing that levan interacted with phospholipids under hydrated conditions (Demel et al., 1998; Vereyken et al., 2001). Furthermore, it was found that levan stabilizes the Lα phase of phosphatidylethanolamine relative to the HII phase by insertion into the headgroup region of the lipids (Vereyken et al., 2001).

However, regarding dry conditions, not much is known about the polysaccharide-membrane interaction. It has long been thought that polysaccharides in contrast to small carbohydrates would not interact with membranes under these conditions and would not be able to protect the membrane barrier function (Crowe et al., 1998, 1997). Small carbohydrates protect the membrane barrier function as shown by reduced carboxyfluorescein (CF) leakage from liposomes (Crowe et al., 1992). In addition, they lower the Lα-Lβ transition temperature (Crowe et al., 1992). For the polysaccharides hydroxyethyl starch and dextran, it was found that they had very limited abilities to protect the membranes (Crowe et al., 1994, 1997; Koster et al., 2000). On the other hand, Ozaki and Hayashi (1997) showed that in the presence of cycloinulohexaose, the leakage of calcein from liposomes was reduced, suggesting that an oligosaccharide can protect the bilayer. In addition, Hincha et al. (2000) showed that inulin-type fructan from chicory roots and dahlia tubers (degree of polymerization, i.e., DP, 10–30) was able to reduce the amount of CF leakage from liposomes consisting of phosphatidylcholine (PC), which were rehydrated after freeze-drying. Furthermore, the polysaccharides reduced the amount of fusion occurring during dehydration. However, they also showed that chicory inulin was not able to protect membranes during air-drying (Hincha et al., 2002). On the other hand, shorter-chain inulins (DP 2–5) were able to reduce CF-leakage from air-dried vesicles (Hincha et al., 2002). In addition, in the dehydrated state, inulin causes an infrared (IR) frequency shift of a phosphate band, which was interpreted as an interaction with the membrane phospholipids (Hincha et al., 2000, 2002).

These findings suggest that inulin-type fructan is able to protect the membrane barrier. However, it is not clear whether this is limited to the inulin-type or is a more general property of fructans. In addition, almost nothing is known about the structural organization of these polysaccharide-lipid systems that can provide insight into the mechanism by which fructans protect the membrane.

To get insight into these aspects of the fructan-lipid interaction, the effect of polysaccharides on membrane integrity during dehydration was measured using CF fluorescence to study leakage. In addition, the fluorescent couple of NBD-PE and Rh-PE was used to study fusion (lipid mixing). Lipid phase behavior and the dimensions of the multibilayer systems were analyzed by x-ray diffraction. The polysaccharides investigated in this study were dextran, levan (Bacillus subtilis), inulin DP26 (dahlia root), and inulin DP10 (chicory root). The experiments were conducted with POPC as a model lipid. Samples were air-dried to mimic the biological process of dehydration.

Here we show that fructans are present between lipid bilayers during dehydration. In addition, fructans stabilize the Lα phase during drying. We also show that they protect the membrane against leakage and fusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Carboxyfluorescein (CF), n-(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl)-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phophoethanolamine (NBD-PE) and (n-lissamine Rhodamine B sulfonyl)-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phophoethanolamine (Rh-PE) were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). CF was purified according to the procedure described by Weinstein et al. (1984). Dextran (mw 37.9 kDa) was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

The chain length of the different fructans used in this study is given as the average degree of polymerization (DP). Levan (25 kDa, DP 125) was isolated from B. subtilis as described in Vereyken et al. (2001). Inulin DP10 (Frutavit IQ) was a kind gift of Sensus (Roosendaal, the Netherlands); it consisted of a mixture of inulin DP5 to DP15. Inulin DP26 (dahlia inulin) was obtained from Sigma and it consisted of a mixture of inulin DP12 to inulin with a DP of ∼40 (compare chromatogram in Hincha et al., 2000).

Preparation of unilamellar vesicles

Lipids dissolved in chloroform were dried using a nitrogen stream. After storage of the lipid film for at least 2 h under vacuum, the lipids were dispersed in aqueous solution under mechanical agitation. For x-ray diffraction experiments lipids were dispersed in water, and for the other experiments the buffer is given under Leakage Experiments, below. Unilamellar vesicles were prepared using a handheld extruder with two layers of polycarbonate membranes (MacDonald et al., 1991). For x-ray diffraction experiments 25-nm filters were used, and in the CF-leakage and fusion assay, 100-nm filters were used.

X-ray experiments

Oriented samples were obtained by making unilamellar vesicles prepared as described above, using 5 mg lipid per sample. A 25-nm filter was necessary to obtain homogenously stacked bilayers in the x-ray sample. Carbohydrate solution of the desired concentration was added to reach a sample volume of 500 μl. The samples were homogenized by freeze/thawing 3×. The samples were spread on a quartz plate, which was heated to 40°C to spread the lipid more easily and to evaporate part of the solvent. The samples were dried for 1 h at room temperature and subsequently dried over saturated salt solutions that generate known relative vapor pressures and thereby known air humidity (Rockland, 1960) to obtain the desired sample hydration. The lowest humidity (0%) was obtained by equilibrating over dry P2O5. After 24 h of exposing the samples to the specific humidity, they were transferred into the 25°C thermostated x-ray chamber, which was also exposed to the same saturated salt solution.

X-ray diffraction measurements were performed at a diffractometer with Ni-filtered CuKα radiation of wavelength λx-ray = 1.54 Å as described in Gordeliy et al. (1996). The repeat distance d of the samples was determined from the positions of diffraction peaks (2d sin θ = λx-ray; θ is the scattering angle). The error in the measured repeat distances was ±0.2 Å. From integral intensities the modules of structure factors were calculated by the equation

|

(1) |

where h is the order of diffraction reflection, L is the Lorentz factor (proportional for oriented specimens at small angles to h), and p is the polarization factor equal to 1/2(1 + cos2(θ)) (Blaurock and Worthington, 1966). The signs of centrosymmetric membrane structure can be equal to ±1 and were determined by the application of Shannon's sampling theorem to the structure factor data (Shannon, 1949) as described in detail previously (McIntosh and Holloway, 1987; McIntosh and Simon, 1986).

The electron density profile along the normal of membrane plane (the x-axis) were calculated by the equation

|

(2) |

Leakage experiments

The experiments were performed as described by Hincha et al. (2002). Unilamellar vesicles were prepared using 10 mg of lipid dispersed in 0.25 ml of 100 mM CF, 10 mM TES, and 0.1 mM EDTA at pH 7.4, and treated as described above in Preparation of Unilamellar Vesicles. To remove the CF not enclosed in the vesicles, the vesicle preparation was passed through a Sephadex G-25 NAP-5 column (Pharmacia, Woerden, The Netherlands) equilibrated in TEN buffer (10 mM TES, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 50 mM NaCl at pH 7.4). The eluted samples were diluted using TEN to a lipid concentration of ∼10 mg/ml. A volume of 40 μl liposomes was mixed with an equal volume of carbohydrate solution and 20-μl aliquots were put into wells of a 60-well microplate. The plates were dried at 28°C and 0% humidity for 24 h in the dark. Afterwards, the dried vesicles were resuspended in 20 μl of TEN buffer. To determine the amount of retention of CF inside the vesicle, 10 μl was taken out of each well and diluted in 300 μl TEN in a 96-well plate. Measurements were made with a Fluoroskan Ascent (Thermo Labsystems, Vantaa, Finland) fluorescence microplate reader at an excitation wavelength of 444 nm and an emission wavelength of 555 nm. The total CF content of the vesicles (100% leakage value) was determined after lysis of the vesicles using 5 μl of 1% (v/v) Triton X-100.

Fusion experiments

Fusion experiments were performed as described by Hincha et al. (2002). Two unilamellar vesicles samples were prepared in TEN as described above, one containing 1 mol % of both NBD-PE and Rh-PE in POPC, the other containing only POPC. The vesicles were combined at a ratio 1:9 (labeled:unlabeled), resulting in a lipid concentration of ∼10 mg/ml. A volume of 40 μl vesicles was mixed with an equal volume of carbohydrate solution and 20-μl aliquots were filled into the inside of the caps of 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes. Samples were dried as described under Leakage Experiments, above, and were rehydrated adding 1 ml of TEN buffer into the tubes and then quickly closing and inverting the tube. The samples were mildly shaken, transferred into a cuvette and diluted with 1 ml TEN buffer. Membrane fusion was measured by resonance energy transfer (Struck et al., 1981) with a Kontron SFM 25 fluorimeter (Bio-Tek Instruments, Neufahrn, Germany) as described in Hincha et al. (1998) and Oliver et al. (1998) before and after the addition of 40 μl of 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 solution.

RESULTS

Consequences of the polysaccharide-lipid interaction for bilayer integrity

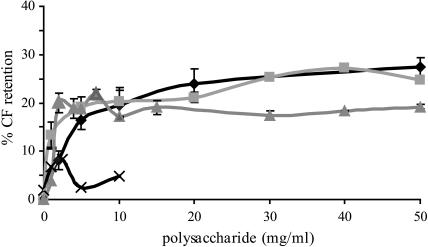

To get insight into the polysaccharide specificity of the membrane barrier protection during air-drying, CF-leakage assays were performed. In this assay, the amount of CF that is retained inside the vesicle during a drying and rehydration process was determined. Inulin DP26 was included in this experiment, since the data could be compared directly with a similar type of inulin isolated from chicory root (Hincha et al., 2002). In the absence of carbohydrates, the CF-content of the POPC vesicles had completely leaked from the vesicle after a drying and rehydration cycle (Fig. 1). Inulin DP26 caused a minor retention of 2–8% CF with a complex concentration dependency. No concentrations >10 mg/ml could be tested, because of the low solubility of this compound. These data are in accordance with previous results (Hincha, unpublished results; and Hincha et al., 2002). In contrast, addition of all the other polysaccharides including dextran resulted in a substantial CF retention. Inulin DP10 and levan showed similar CF retention, whereas the effect of dextran was less pronounced. These data demonstrate that polysaccharides are able to protect the membrane barrier function to some extent during a dehydration-rehydration cycle. Fructans are more potent protectors in this respect than dextran.

FIGURE 1.

The effect of polysaccharides on CF-leakage from POPC unilamellar vesicles during drying. Leakage of CF from the vesicles was determined after drying for 24 h at 0% humidity and subsequent rehydration. The samples contained the indicated amount of polysaccharides, inulin DP26 (x), dextran (▴), levan (▪), and inulin DP10 (♦). The data shown are the mean ± SD from six samples. Where no error bar is visible, it is smaller than the symbol.

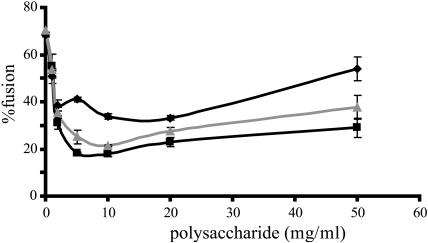

During drying and rehydration many different processes occur which could induce CF-leakage. One of these is vesicle fusion which we analyzed using a fluorescent-based lipid mixing assay. In this protocol, pure POPC vesicles underwent 70% fusion during drying and rehydration (Fig. 2). Addition of any polysaccharide up to a concentration of 10 mg/ml led to a large reduction in fusion. The effect followed the order of inulin DP10 > levan > dextran. Above 10 mg/ml fusion increased slightly again, but even at 50 mg/ml, it never reached the level of the control samples without carbohydrate. Dextran showed the strongest increase followed by levan and inulin DP10.

FIGURE 2.

The effect of polysaccharides on fusion of POPC unilamellar vesicles during drying. Fusion of the vesicles was measured after drying for 24 h at 0% humidity and subsequent rehydration. The samples contained the indicated amount of polysaccharides, dextran (♦), levan (▴), and inulin DP10 (▪).

Effect of polysaccharides on lipid phase properties

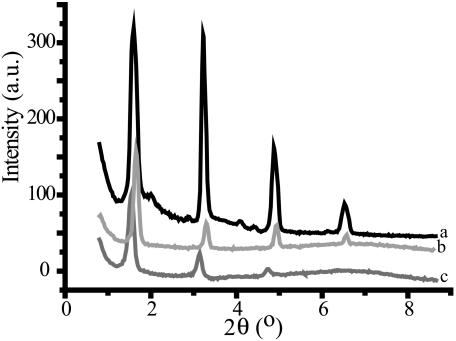

The effect of the different polysaccharides on the organization of POPC was analyzed using x-ray diffraction on oriented systems at different stages of hydration. At 97% humidity, POPC gave four reflections, the intensities decreasing with increasing diffraction angle (Fig. 3). The reflections were spaced following 1:1/2:1/3:1/4 indicative of a multilamellar phase. The repeating distance was 54 Å. This distance corresponds to a hydrated liquid crystalline phase known to occur under these conditions for this lipid (Katsaras et al., 1993). In the presence of dextran in a molar ratio of monosaccharide unit:lipid of 1:1, diffraction pattern b was observed in which the reflections are positioned at slightly higher θ values than for pure POPC. Correspondingly, the repeat distance decreased by 1.7 Å (Table 1). In contrast, in the presence of levan the reflections were observed at smaller diffraction angles corresponding to a 3.5 Å larger repeat distance. In addition, the reflections were broadened such that the fourth-order reflection was hardly visible. This indicates that the presence of levan results in a less ordered sample. Inulin DP10 gave comparable results to levan; the repeat distances are shown in Table 1. Furthermore, from the full summary of measured results in Table 1, it is clear that the repeat distance for all carbohydrates changed in a concentration-dependent manner. In all cases the reflections corresponded to a multilamellar liquid-crystalline phase.

FIGURE 3.

X-ray pattern of POPC in the absence or presence of carbohydrates at 97% humidity. Samples were equilibrated for 24 h over a saturated solution of K2SO4 to reach 97% humidity. Line a is the spectrum of pure POPC, line b is POPC/dextran, and line c is POPC/ levan. In all cases the monosaccharide unit:lipid molar ratio was 1:1.

TABLE 1.

Repeat distance of a POPC multibilayer at 97% humidity in the absence or presence of polysaccharides

| Repeat distance (Å) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugar:lipid | 0:1 | 0.5:1 | 1:1 | 2:1 |

| Levan | 54 | 55.7 | 57.5 | 58.8 |

| Inulin DP 10 | 54 | 54.5 | 54.7 | 58 |

| Dextran | 54 | 53.1 | 52.3 | – |

Samples were kept for 24 h over a saturated K2SO4 solution to obtain 97% humidity. The ratio depicted are mol of lipid to mol of monosaccharide unit.

At the lower humidity of 32%, POPC was present in two phases, as indicated by two sets of reflections corresponding to two repeat distances (diffraction patterns are not shown; results are summarized in Table 2). Since the reflections of both sets related as 1:1/2:1/3:1/4, they correspond to multilamellar phases. The smaller repeat distance of 51.6 Å we assigned to the liquid-crystalline phase. The reduction in repeat distance as compared to the value at 97% humidity is due to the lower hydration of the lipids at this humidity resulting in a thinner water layer. The larger repeat distance of 59 Å is likely to correspond to the gel phase in which the stretched acyl chains increase the bilayer thickness. Consistent with this view, heating the sample to 35°C resulted in one phase with the smaller repeat distance indicative for the liquid crystalline phase (data not shown). The presence of dextran in a monosaccharide unit:lipid molar ratio of 0.5:1 did not result in any phase changes; only a slightly reduced repeat distance of the gel phase was observed. However, the presence of twice the amount of dextran resulted in pure gel phase formation as indicated by a single repeat distance 58.3 Å. In accordance with the data at 97% humidity, the repeat distance is smaller than for pure POPC. Addition of inulin DP10 resulted at both molar ratios in the formation of the liquid crystalline phase with a repeat distance that was larger than that of pure POPC. Levan in a 0.5:1 molar ratio also gave a two-phase system with an increased repeat distance of the Lα phase as observed at higher hydration. However, at the ratio 1:1 one phase is formed, with an intermediate repeat distance which we tentatively assigned to the liquid crystalline phase in analogy with the data obtained at 97% humidity and the data for inulin DP10.

TABLE 2.

The repeat distance and the phase of POPC in the absence or presence at 32% humidity

| Repeat distance (Å) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sugar:lipid | 0:1 | 0.5:1 | 1:1 |

| Levan | 59/51.6 | 58.4/53.7 | 56.3 |

| Inulin DP 10 | 59/51.6 | 52 | 53.5 |

| Dextran | 59/51.6 | 58/51.6 | 58.3 |

Samples were kept for 24 h over a saturated MgCl2 solution to equilibrate the sample at 32% humidity and were measured at 25°C. In the case of multiple phases the repeat distance of each phase is presented. The ratios depicted are mol of lipid to mol of monosaccharide unit.

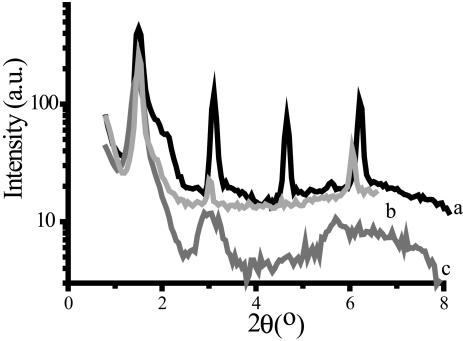

At 0% humidity, POPC showed again a set of reflections corresponding to a multilamellar phase (Fig. 4). The repeat distance was 57.1 Å. Given the lower hydration and the results obtained at 32% humidity, POPC most likely is in a multilamellar gel phase without water between the layers. This assignment is in agreement with Katsaras et al. (1993). In the presence of dextran, the third-order reflection was absent and the diffraction peaks were less intense (Fig. 4). However, the repeat distance was hardly affected (Table 3). Interestingly, the presence of levan resulted a different diffraction pattern (Fig. 4) in which the reflections were substantially broadened and the third-order reflection was absent. The position of the reflections was still indicative of a multilamellar phase. Inulin DP10 gave a similar diffraction pattern (data not shown). The observed repeat distance in the presence of both carbohydrates first increased and then decreased with higher carbohydrate content as is shown in Table 3.

FIGURE 4.

X-ray spectrum of POPC in the absence and presence of carbohydrates at 0% humidity. Samples were equilibrated for 24 h over P2O5. Line a is the spectrum of pure POPC, line b of POPC/dextran, and line c of POPC/levan. In all cases the monosaccharide unit:lipid molar ratio was 1:1.

TABLE 3.

The repeat distance of a POPC bilayer at 0% humidity in the absence or presence of sugars

| Repeat distance (Å) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugar:lipid | 0:1 | 0.5:1 | 1:1 | 2:1 |

| Levan | 57.1 | 59.3 | 58.4 | 54.2 |

| Inulin DP 10 | 57.1 | 58.3 | 57 | 52 |

| Dextran | 57.1 | 57.8 | 56.8 | – |

Samples were kept for 24 h over dry P2O5 to obtain dry samples. The ratios depicted are mol of lipid to mol of monosaccharide unit.

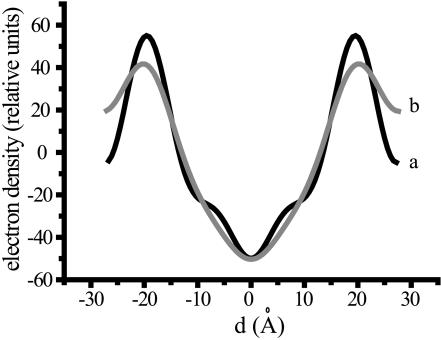

To get insight into the position of the fructans with respect to the bilayer, electron density profiles were calculated at 97% humidity, since the diffraction patterns had the best quality under these conditions. For pure POPC the characteristic electron density profile for a bilayer is obtained (Nagle and Tristram-Nagle, 2000) with a reduced density in the middle of the bilayer where the end of the acyl chains are present and an increased density at the position of the phosphate group (Fig. 5). The distance between the maxima is 39.4 Å. In the presence of levan, changes in the profile are observed in the headgroup region of the bilayer. An increase in electron density is observed at the edges of the spectrum at the expense of the density in the phosphate region. This could be due to the additional density of the fructan molecules entering the headgroup region. These data indicate that levan is predominantly present in the headgroup region in between the lipid layers. For inulin DP10, similar results were obtained (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Electron density profile of POPC in the absence (a) and presence (b) of levan. The electron density profile was calculated from the diffraction pattern at 97% humidity and the monosaccharide unit:lipid ratio was 0.5:1. The center of the bilayer is defined as d = 0.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of polysaccharides on the lipid organization and membrane barrier function during dehydration. From the results it can be concluded that fructans were able to protect the membrane barrier function during a drying and rehydration cycle. In addition, they influenced the lipid phase behavior and the lamellar dimensions.

The effects of polysaccharides on membrane integrity during a drying and rehydration cycle were investigated using a CF-leakage assay. The membrane barrier function was protected by all polysaccharides. Only inulin DP26 did not show a pronounced effect in agreement with earlier studies (Hincha et al., 2002; and Hincha, unpublished results). This is most likely reflecting its poor solubility and consequently its precipitation during the air-drying process. In the presence of both other fructan types CF was retained to the same extent. Therefore, it can be concluded that both inulin and levan are able to protect membrane integrity during drying.

In the presence of dextran a substantial amount of CF was also retained, although less than in the presence of fructan. This seems to contradict the findings of other authors, who found, using a freeze-drying protocol, that the presence of dextran did not lead to CF-retention (Crowe et al., 1994). This latter finding suggests that the air-drying process we employed, and which resembles biological dehydration processes, is more efficient for preserving vesicles in the presence of polysaccharide. Air-drying and freeze-drying differ technically, thereby giving rise to different results (Crowe et al., 1990). In freeze-drying, the low temperature results in ice formation and tightly-packed lipid organizations. In contrast, during air-drying, water is removed slowly at a higher temperature, leading to highly concentrated solutions until glass transitions occur during the final phase of drying.

Vesicle fusion is a known process causing leakage during air-drying and rehydration of lipid vesicles (Crowe et al., 1998). To get insight into the fusion behavior a lipid-mixing assay was used. It was shown that all tested polysaccharides were efficient fusion inhibitors following the order of inulin DP10 > levan > dextran. This is in accordance with the CF-leakage results in which dextran was also less effective than both fructan types. Comparing the fusion results for inulin DP10 with the results of Hincha et al. (2002) for smaller inulins shows a small deviation in absolute values. However, since different lipid systems were used, the absolute values are not directly comparable.

To get insight into the mechanism by which fructans protect the membrane, the polysaccharide-lipid systems were investigated by x-ray diffraction experiments at different stages of hydration. Under all conditions lamellar phases were maintained for POPC. At 97% humidity, an increase in the lamellar spacing was observed for inulin DP10 and levan. This increase can be explained either by the presence of the carbohydrates in between the layers or a stretching of the acyl chains. The stretching of the acyl chains is very unlikely since levan was not able to influence the chain order of lipids under fully hydrated conditions as measured with deuterium-labeled 1-stearoyl-rac-glycerol (MSG) in 2H-NMR (Vereyken et al., 2001). In that study it was observed that fructans are able to insert between the headgroups of phospholipids, which makes the presence of fructan in the aqueous phase between the lipid bilayers the likely explanation for the increase in lamellar repeat distances. The location of the fructan in the headgroup region is supported by the change of the electron density profile (Fig. 3). Moreover, that fructans are present in between the lipid bilayer is consistent with all other measured x-ray data, the CF-leakage results, and the fusion data.

At 32% humidity for pure POPC, two phases were observed: the liquid crystalline phase (Lα) and the lamellar gel phase (Lβ). In the cases where an Lα phase was observed, the repeat distance followed the same trend as at 97% humidity, meaning an increase in repeat distance for levan and inulin DP10, from which it can be concluded that at this humidity, fructans are also present in between the lipid layers. Since for pure POPC two phases were observed, the effect of the carbohydrates on the phase behavior could be studied. In the presence of inulin DP10 only one set of repeat distances was observed, therefore only one phase was present. We assign this phase to be the Lα phase, given the repeat distance and the analogy with the situation at 97% humidity. In addition, based on the data of Demel et al. (1998) we propose that inulins intercalate between the lipid headgroups, thereby most likely inhibiting formation of the more densely-packed gel phase and thus stabilizing the Lα phase.

In the presence of levan at low carbohydrate content two phases were observed, but at higher concentrations one phase remained. In analogy with the results of inulin DP10 and the known ability of levan to insert in the headgroup region of phospholipids, we propose that levan also promotes the formation of the Lα phase under these conditions. This appears to contradict earlier studies (Vereyken et al., 2001), which showed that under fully hydrated conditions fructans do not influence the Lβ-Lα phase transition temperature. A possible explanation is that the insertion of levan in between the lipids is more pronounced when less water is present, thereby more effectively blocking gel phase formation. This interference of water with carbohydrate-membrane interactions in the dry state has been shown for several mono-, di-, and trisaccharides (Nagase et al., 1997). From these data we conclude that fructans in general promote Lα phase formation during dehydration. The slightly more pronounced effect of inulin DP10 on the phase behavior compared to levan could be explained by differences in flexibility of the carbohydrates as suggested from molecular dynamics studies (Vereyken et al., 2003b). Levan appears to be less flexible compared to inulin and therefore may be less able to interact with membrane lipids.

At 0% humidity, the repeat distances in the presence of levan and inulin DP10 showed the same trend. At lower carbohydrate concentration the repeat distance became larger, indicating again the presence of the polysaccharides in between the lipid bilayer. However, the presence of more carbohydrate leads to a decrease in lamellar spacing. This probably results from an increased fructan-lipid interaction, leading to more mobility in the acyl-chain region, and could even result from melting of the acyl chains and therefore a thinner bilayer. In accordance with this interpretation, by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) it was observed that both carbohydrates induced a phase transition to a more mobile phase at temperatures (Tm) <10°C in a dry lipid system, where for pure POPC the Tm of the dry system was ∼60°C (Vereyken et al., 2003a). Moreover, Hincha et al. (2002) observed a decrease in Tm for dry egg PC in the presence of short-chain inulins and chicory inulin compared to pure egg PC. In addition, a broadening of the peaks was observed. This could be explained by the fact that not all lipids were interacting to the same extent with the fructans as was observed earlier in nuclear magnetic resonance and FTIR experiments (Vereyken et al., 2003a).

From this we can conclude that fructans are present between the lipid bilayer during dehydration, and moreover they stabilize the Lα phase. This is in accordance with the CF-leakage and fusion results.

The effects observed using fructans are explained in this discussion by the direct interaction of lipids and fructans as supported by the data found under fully hydrated conditions. Considering the data under dehydrated conditions, nonspecific effects of fructans could also be used to explain the observed effects using the vitrification theory of Koster et al. (2000). The presence of a glass between the lipid bilayers during dehydration is hypothesized to mechanically prevent the condensation of the lipid bilayers and thereby a phase transition to the gel phase. This would explain the observed reduction in leakage and also the x-ray data at 0% and 32% humidity, indicating the presence of the Lα phase. In addition, Koster et al. (2000) found that larger dextran molecules were excluded from the interbilayer space. Since levan has a mol wt of 25 kDa, the present data imply that larger molecules are also able to induce this behavior.

In the presence of dextran a different picture emerged. At 97% humidity a slightly decreased repeat distance was observed, indicating that this polysaccharide was not present in between the regular stacked lipid layers. This is consistent with our earlier observation that dextrans hardly have an interaction with the bilayer under fully hydrated conditions (Vereyken et al., 2001), and it also agrees with the results of others (Crowe et al., 1994; Koster et al., 2000). The slight decrease in repeat distance can be explained according to Koster and co-workers (Koster et al., 2000, 1994). They state that polysaccharides are excluded from the intermembrane regions, thereby osmotically dehydrating the lipids to a small degree. This would explain the thinner water layer (see also Rand and Parsegian, 1989).

At 32% humidity only one set of reflections was observed, therefore only one phase was present. The repeat distance was close to that of the gel phase for pure POPC. Therefore, it was concluded that dextrans, in contrast to fructans, promote gel-phase formation under partial dehydration of the lipids, as supported by the vitrification theory—which also explains the small decrease in repeat distance.

In the presence of dextrans at 0% humidity the lamellar spacing was similar to that of pure POPC, again indicating that dextran was not present between the lipid bilayers and had no direct interaction with lipids. This is in accordance with the fact that the order-disorder phase transition temperature hardly changed in the presence of dextran as observed using FTIR (Vereyken et al., 2003a; Crowe et al., 1994; Koster et al., 2000).

There is an apparent contradiction between the x-ray experiments and the leakage and fusion experiments in the presence of dextran. Inhibition of fusion through carbohydrate vitrification would require the carbohydrates to be present between the lipid bilayer. The x-ray data, however, indicate that dextran is largely excluded from the membranes. One explanation could be that the difference depends on the used protocols. It is conceivable that, during drying of the unilamellar vesicles, some dextran is entrapped between the vesicles, thereby protecting some portion of the vesicles—whereas in the x-ray experiments, it is largely excluded from the closely-stacked multilamellar system. That some dextran is present in parts of the sample in the x-ray experiment cannot be excluded. The decrease in intensity of the higher-order reflections could indicate a disturbance in the long-range order in part of the multilamellar stacks. This might indicate that dextrans are not fully excluded from the lipid phase.

How to explain the different effects of fructan and dextran on the bilayer? There is no unambiguous answer to this question, but we suggest that the differences are related to the differences in flexibility of the two polysaccharides. Dextrans are composed of more immobile pyranose rings (Barrows et al., 1995), whereas the fructans are composed of more flexible furanose rings (French and Waterhouse, 1993). The more flexible fructans may have more opportunities to interact with the lipid than the more rigid dextrans (Vereyken et al., 2003b).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an Earth and Life Sciences and Chemical Sciences grant, with financial aid from the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research. Additional support came from Chemical Sciences CW/STW project 349-4608, with financial aid from the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research.

References

- Barrows, S. E., F. J. Dulles, C. J. Cramer, and A. D. French. 1995. Relative stability of alternative chair forms and hydroxymethyl conformations of β-D-glucopyranose. Carbohydr. Res. 276:219–251. [Google Scholar]

- Blaurock, A. E., and C. R. Worthington. 1966. Treatment of low angle x-ray data from planar and concentric multilayered structures. Biophys. J. 6:305–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, J. H., J. F. Carpenter, and L. M. Crowe. 1998. The role of vitrification in anhydrobiosis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 60:73–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, J. H., J. F. Carpenter, L. M. Crowe, and T. J. Anchordoguy. 1990. Are freezing and dehydration similar stress factors? A comparison of modes of interaction of stabilizing solutes with biomolecules. Cryobiology. 27:219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, J. H., F. A. Hoekstra, and L. M. Crowe. 1992. Anhydrobiosis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 54:579–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, J. H., S. B. Leslie, and L. M. Crowe. 1994. Is vitrification sufficient to preserve liposomes during freeze-drying? Cryobiology. 31:355–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, J. H., A. E. Oliver, F. A. Hoekstra, and L. M. Crowe. 1997. Stabilization of dry membranes by mixtures of hydroxyethyl starch and glucose: the role of vitrification. Cryobiology. 35:20–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demel, R. A., E. Dorrepaal, M. J. M. Ebskamp, J. C. M. Smeekens, and B. de Kruijff. 1998. Fructans interact strongly with model membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1375:36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French, A. D., and A. L. Waterhouse. 1993. Chemical structure and characteristics. In Science and Technology of Fructans. M. Suzuki, and N. J. Chatterton, editors. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 41–81.

- Gordeliy, V. I., V. G. Cherezov, A. V. Anikin, M. V. Anikin, V. V. Chupin, and J. Teixeira. 1996. Evidence of entropic contribution to “hydration” forces between membranes. Progr. Coll. Pol. Sci. 100:338–344. [Google Scholar]

- Hendry, G. A. F. 1993. Evolutionary origins and natural functions of fructans—a climatological, biogeographic and mechanistic appraisal. New Phytol. 123:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hincha, D. K., E. M. Hellwege, A. G. Heyer, and J. H. Crowe. 2000. Plant fructans stabilize phosphatidylcholine liposomes during freeze-drying. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hincha, D. K., A. E. Oliver, and J. H. Crowe. 1998. The effects of chloroplast lipids on the stability of liposomes during freezing and drying. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1368:150–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hincha, D. K., E. Zuther, E. M. Hellwege, and A. G. Heyer. 2002. Specific effects of fructo- and gluco-oligosaccharides in the preservation of liposomes during drying. Glycobiology. 12:103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsaras, J., K. R. Jeffrey, D. S. Yang, and R. M. Epand. 1993. Direct evidence for the partial dehydration of phosphatidylethanolamine bilayers on approaching the hexagonal phase. Biochemistry. 32:10700–10707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinova, T., D. Parvanova, A. Atanassov, and D. Djilianov. 2002. Freezing tolerant tobacco, transformed to accumulate osmoprotectants. Plant Sci. 163:157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Koster, K. L., Y. P. Lei, M. Anderson, S. Martin, and G. Bryant. 2000. Effects of vitrified and nonvitrified sugars on phosphatidylcholine fluid-to-gel phase transitions. Biophys. J. 78:1932–1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster, K. L., M. S. Webb, G. Bryant, and D. V. Lynch. 1994. Interactions between soluble sugars and POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylphosphatidylcholine) during dehydration: vitrification of sugars alters the phase behavior of the phospholipid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1193:143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, R. C., R. I. MacDonald, B. P. Menco, K. Takeshita, N. K. Subbarao, and L. R. Hu. 1991. Small-volume extrusion apparatus for preparation of large, unilamellar vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1061:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, T. J., and P. W. Holloway. 1987. Determination of the depth of bromine atoms in bilayers formed from bromolipid probes. Biochemistry. 26:1783–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, T. J., and S. A. Simon. 1986. The hydration force and bilayer deformation: a reevaluation. Biochemistry. 25:4058–4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase, H., H. Ueda, and M. Nakagaki. 1997. Effect of water on lamellar structure of DPPC/sugar systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1328:197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagle, J. F., and S. Tristram-Nagle. 2000. Structure of lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1469:159–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, A. E., D. K. Hincha, L. M. Crowe, and J. H. Crowe. 1998. Interactions of arbutin with dry and hydrated bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1370:87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki, K., and M. Hayashi. 1997. Cryoprotective effects of cycloinulinohexaose on freezing and freeze-drying of liposomes. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 44:2116–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilon-Smits, E. A. H., M. J. M. Ebskamp, M. J. W. Jeuken, P. J. Weisbeek, and S. C. M. Smeekens. 1995. Improved performance of transgenic fructan-accumulating tobacco under drought stress. Plant Physiol. 107:125–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontis, H. G. 1989. Fructans and cold stress. J. Plant Physiol. 134:148–150. [Google Scholar]

- Rand, R. P., and V. A. Parsegian. 1989. Hydration forces between lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 988:352–376. [Google Scholar]

- Rockland, L. S. 1960. Saturated salt solutions for static control of relative humidity between 5° and 40°C. Anal. Chem. 32:1375–1376. [Google Scholar]

- Senaratna, T., B. D. McKersie, and R. H. Stinson. 1984. Association between membrane phase properties and dehydration injury in soybean axes. Plant Physiol. 76:759–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, C. E. 1949. Proc. Instr. Radio Eng. N4 37. [Google Scholar]

- Struck, D. K., D. Hoekstra, and R. E. Pagano. 1981. Use of resonance energy transfer to monitor membrane fusion. Biochemistry. 20:4093–4099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vereyken, I. J., V. Chupin, R. A. Demel, S. C. Smeekens, and B. de Kruijff. 2001. Fructans insert between the headgroups of phospholipids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1510:307–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vereyken, I. J., V. Chupin, F. A. Hoekstra, S. C. M. Smeekens, and B. de Kruijff. 2003a. The effect of fructan on membrane lipid organization and dynamics in the dry state. Biophys. J. 84:3759–3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vereyken, I. J., A. van Kuik, T. H. Evers, P. J. Rijken, and B. de Kruijff. 2003b. Structural requirements of the fructan-lipid interaction. Biophys. J. 84:3147–3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, J. N., E. Ralston, D. Leserman, R. D. Klausner, P. Dragsten, P. Henkart, and R. Blumental. 1984. Liposome Technology. G. Gregoriadis, editor. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 183–204.