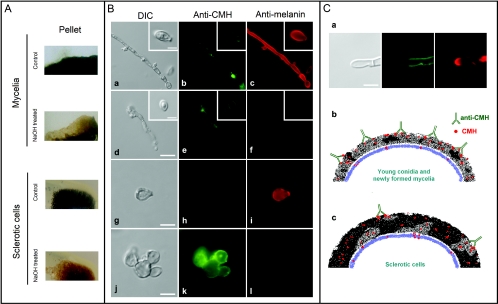

FIG. 8.

Influence of melanin shield on CMH recognition by a monoclonal antibody. (A) F. pedrosoi was treated with alkali (NaOH) or PBS (control), followed by visual analysis of pigmentation. Alkali treatment resulted in fewer pigmented mycelia and sclerotic cells. (B) Untreated mycelia (a) and conidia (a, inset) or sclerotic cells (g) reacted with the antibody to conserved cerebroside (anti-CMH) in limited regions of the cell surface, as demonstrated in panels b and h, respectively. In contrast, these cells were efficiently recognized by the antibodies to melanin (antimelanin, panels c and i). After alkali treatment, the cell shape of F. pedrosoi was maintained (d and j). In these cells, reactivity of fungal forms with the antibody to CMH was greatly increased (e and k), which was accompanied by a clear decrease in the recognition of F. pedrosoi by antibodies to melanin (f and l). Based on these results, we propose in panel C a hypothetical relationship between melanin expression and anti-CMH reactivity in F. pedrosoi. Based on the clear inverse relationship between melanin (red fluorescence) and CMH (green fluorescence) detection on the cell wall of F. pedrosoi (a), we hypothesize that young conidia and growing mycelia that express small quantities of melanin react efficiently with antibodies to CMH, resulting in microbial killing through enhanced phagocytosis or direct antimicrobial action (b). A high amount of melanin, commonly observed in sclerotic cells, would block sites for antibody binding, making fungi more resistant to the antimicrobial action of macrophages and antibodies to CMH (c). Bars, 3.5 μm (B; a, d, g and j), 1.5 μm (insets), 1 μm (C).