A surge in the number of deaths from West Nile virus in Canada last year compared with 2004 was likely due to hotter weather.

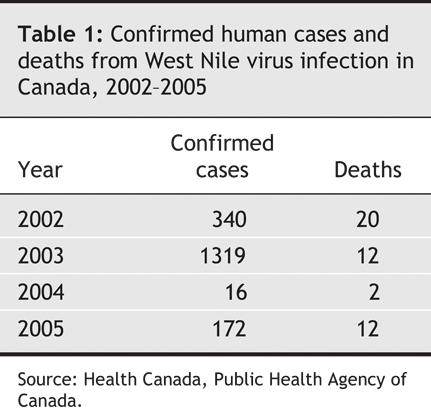

As of Oct. 29, 12 deaths and 172 confirmed human cases of the virus had been reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada (Table 1). In 2004, only 2 people died; in 2003, there were 12 deaths and in 2002, 20.

Table 1

In the US, the number of deaths dropped to 73 from 79 in 2004, 264 in 2003 and 582 in 2002. But a medical epidemiologist with the US Centers for Disease Control would not call the diminishing death rate a trend. It's impossible to accurately predict what will happen in 2006, says Dr. Grant Campbell. “There are so many variables involved.”

These variables include climate, weather, bird migration, immunity and reproduction.

Mike Drebot, head of Health Canada's Viral Zoonoses Section of the Canadian Centre for Human and Animal Health, says this year's surge may have occurred because most regions had a hotter summer than in 2004.

Winnipeg, for example, had an “unprecedented” hot and wet summer, leading to record-breaking numbers of mosquitoes, according to the city's entomologist, Taz Stuart. This led the city to use larvicides and to “fog” sections of the city with insecticide on a nightly basis for nearly a month. Despite these efforts, there were 46 confirmed cases and one reported death from WNV in Manitoba in 2005. In 2004, Manitoba had no deaths and no confirmed cases, and in 2003 the province reported 2 deaths and 39 confirmed cases.

Saskatchewan reported 8 confirmed cases and 2 deaths in 2005. Ontario had the largest number of confirmed cases this year (91) as well as 8 deaths. Southern Ontario's hot summer was a contributing factor, says Drebot.

Overall, the number of cases and deaths have been declining in Canada and the US since 2002. Experts attribute the decline to preventive measures such as removing standing water, spraying and wearing mosquito repellant, as well as to increased immunity in host birds.

“There may not be as many reservoir birds for the virus, which could affect case rates,” says Drebot, adding that research is required to confirm this.

In 2005, 447 birds tested positive for the virus in Canada, compared to 416 in 2004 and 1632 in 2003.

Drebot is encouraged by the fact that some strains of the virus found in Mexico and Texas seem to have become less virulent. In addition, between 2% and 5% of North Americans have been exposed to the virus and may be immune. “We may never see the large epidemics in Canada that we saw in 2002 and 2003,” he says.

Although the virus is lingering in central Canada, it has moved west in the US, likely following the migratory routes of birds, says Campbell. — Kristen Everson, Ottawa

Figure. Winnipeg entomologist Taz Stuart in 2005 explaining plans to fog neighbourhoods with insecticide in view of high counts of mosquitoes. There were 46 confirmed cases and 1 death from WNV in Manitoba last year. Photo by: Canapress