Abstract

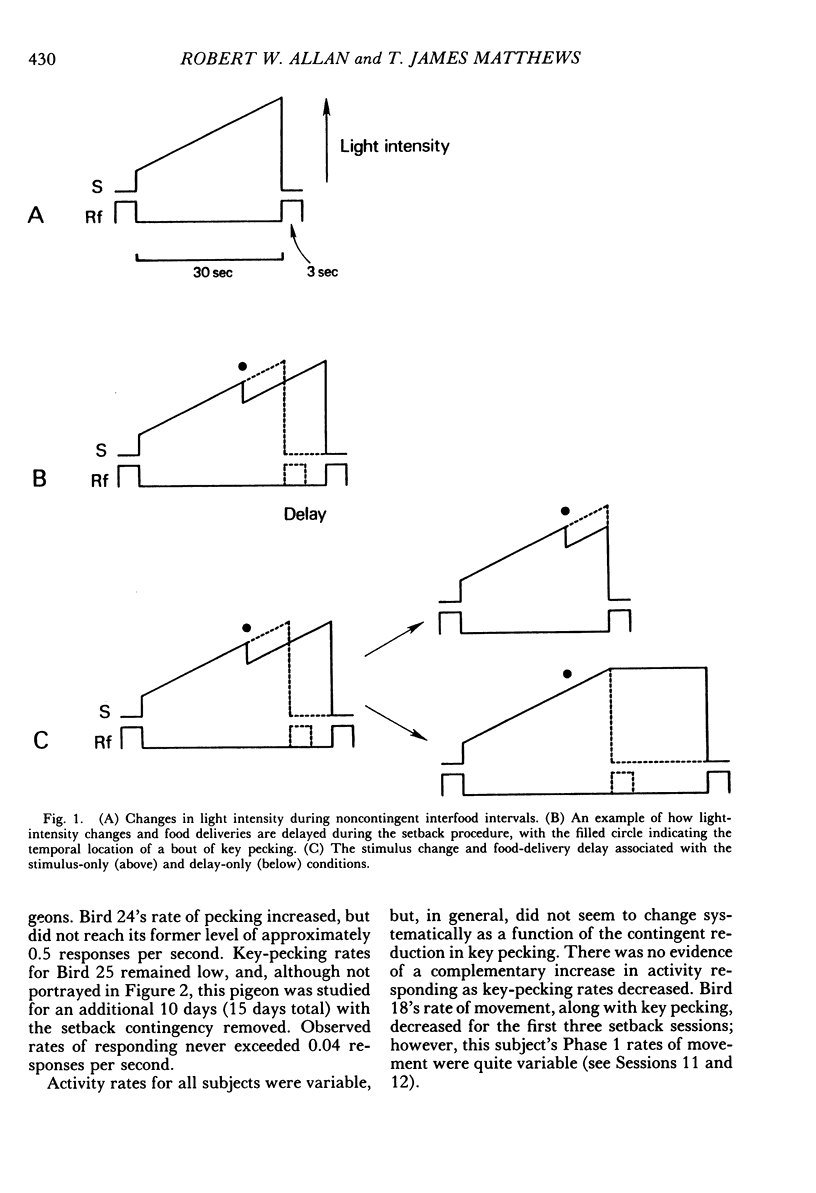

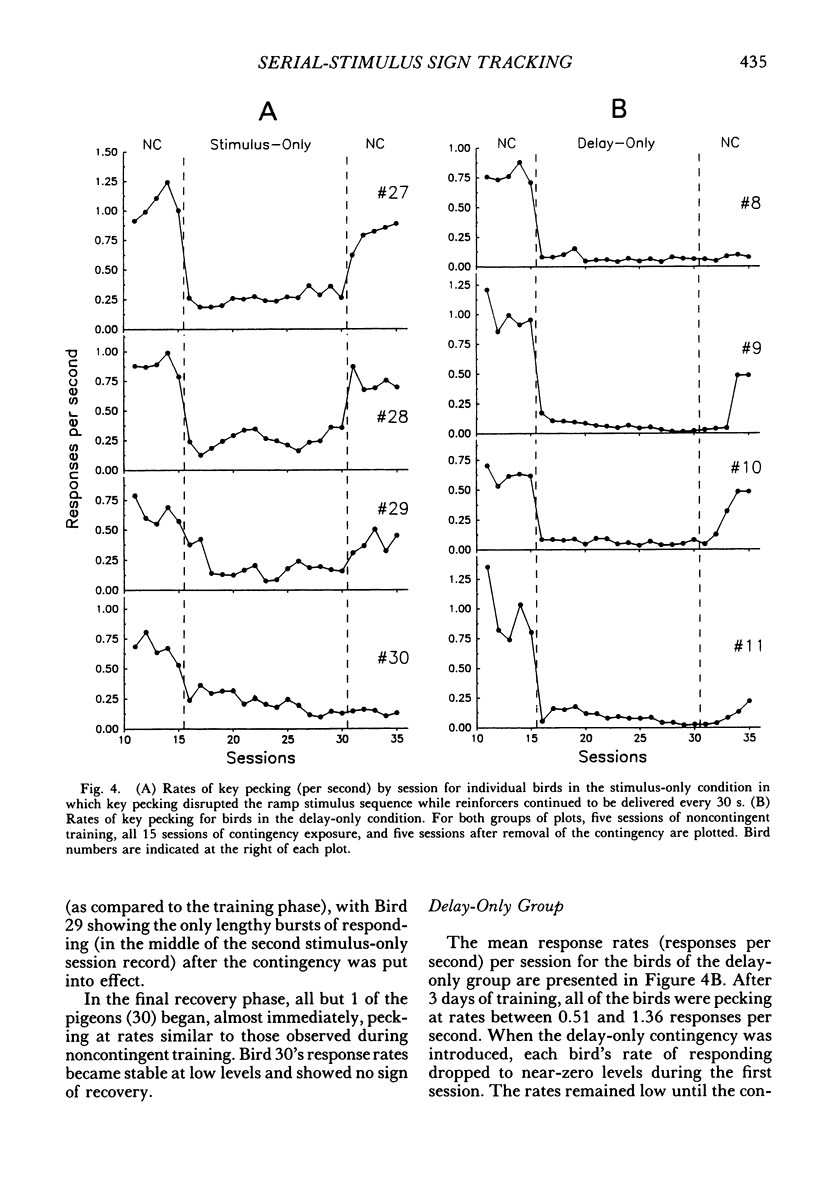

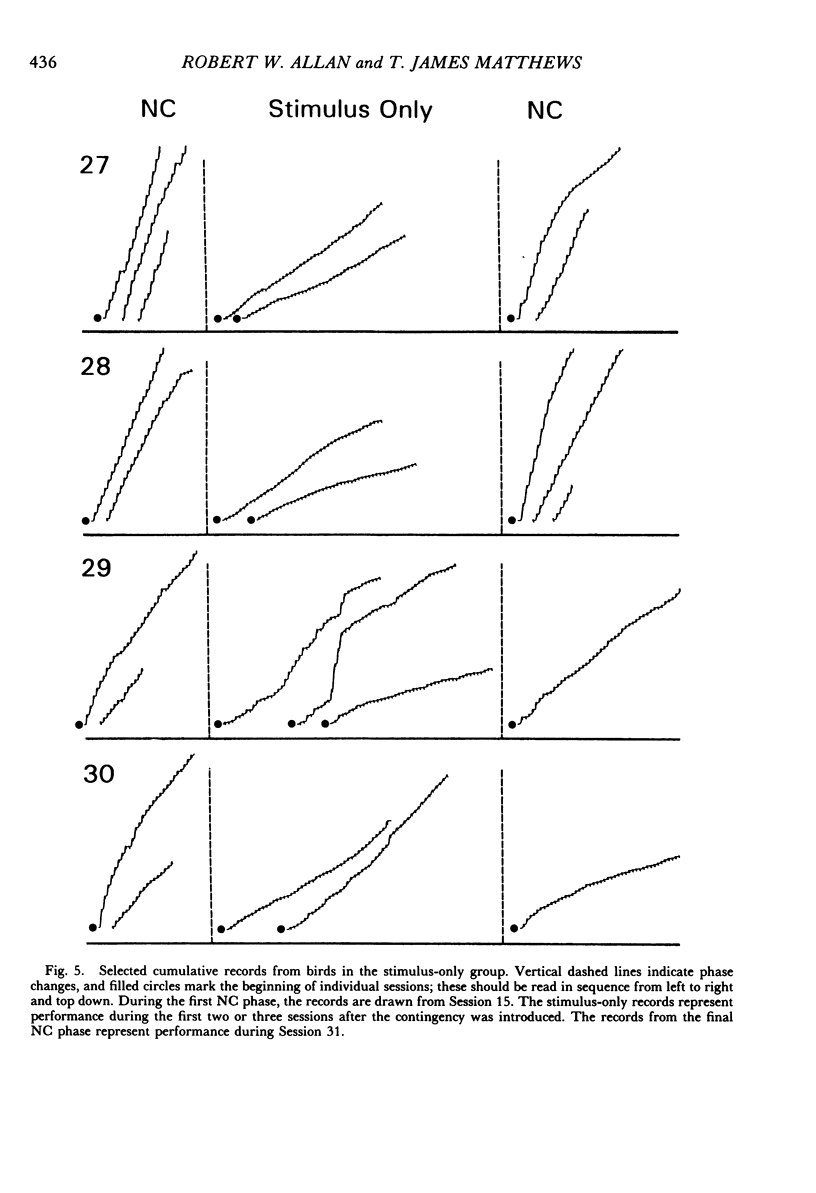

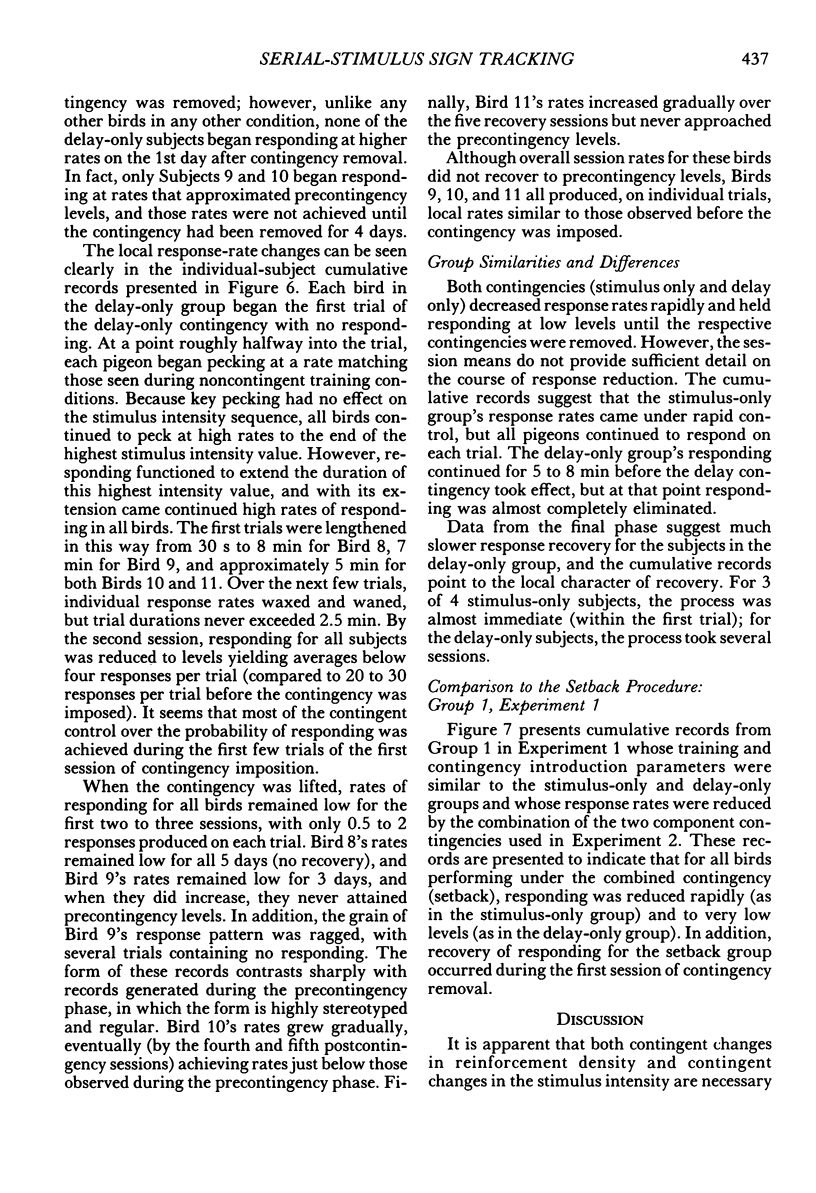

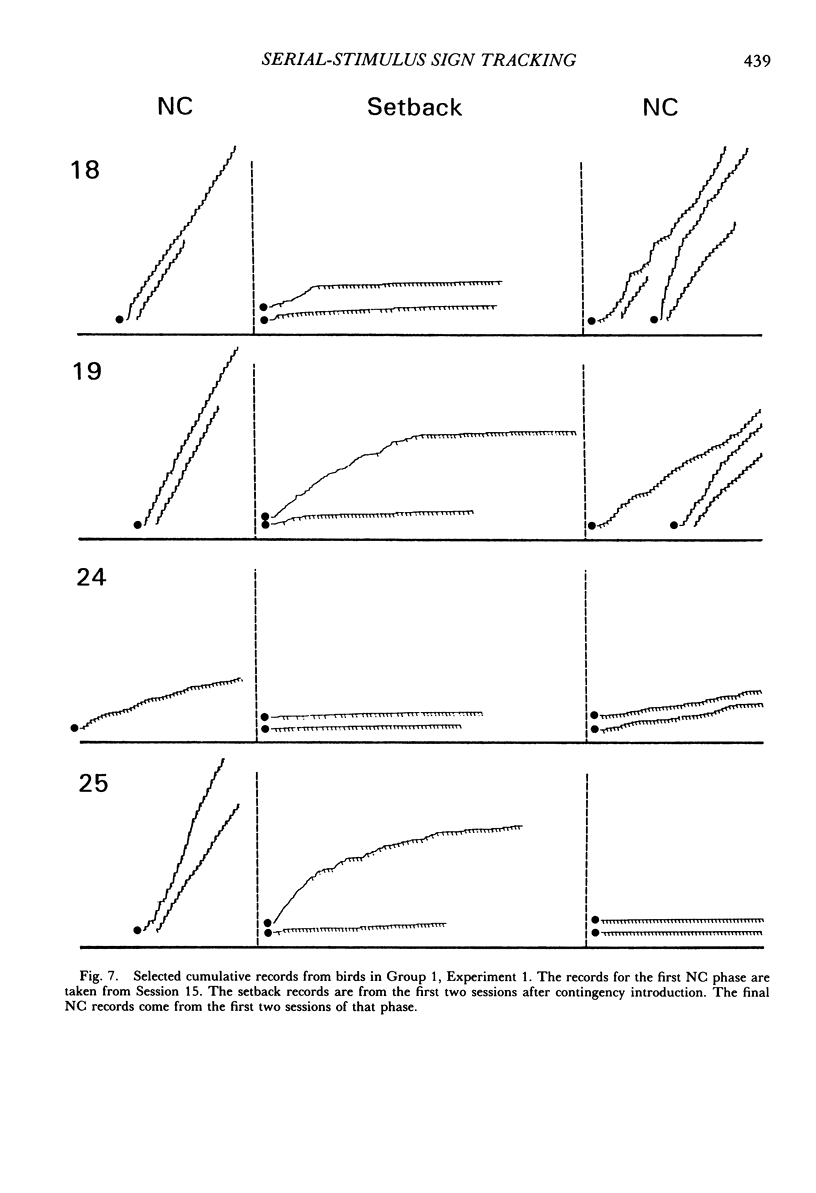

Two experiments examined the effects of a negative (setback) response contingency on key pecking engendered by a changing light-intensity stimulus clock (ramp stimulus) signaling fixed-time 30-s food deliveries. The response contingency specified that responses would immediately decrease the light-intensity value, and, because food was delivered only after the highest intensity value was presented, would delay food delivery by 1 s for each response. The first experiment examined the acquisition and maintenance of responding for a group trained with the contingency in effect and for a group trained on a response-independent schedule with the ramp stimulus prior to introduction of the contingency. The first group acquired low rates of key pecking, and, after considerable exposure to the contingency, those rates were reduced to low levels. The rates of responding for the second group were reduced very rapidly (within four to five trials) after introduction of the setback contingency. For both groups, rates of responding increased for all but 1 bird when the contingency was removed. A second experiment compared the separate effects of each part of the response contingency. One group was exposed only to the stimulus setback (stimulus only), and a second group was exposed only to the delay of the reinforcer (delay only). The stimulus-only group's rates of responding were immediately reduced to moderate levels, but for most of the birds, these rates recovered quickly when the contingency was removed. The delay-only groups's rates decreased after several trials, to very low levels, and recovery of responding took several sessions once the contingency was removed. The results suggest that (a) sign-tracking behavior elicited by an added clock stimulus may be reduced rapidly and persistently when a setback contingency is imposed, and (b) the success of the contingency is due both to response-dependent stimulus change and response-dependent alterations in the frequency of food delivery. The operation of the contingency is compared with the effects of secondary reinforcement and punishment procedures.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- AZRIN N. H. Effects of punishment intensity during variable-interval reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1960 Apr;3:123–142. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1960.3-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera F. J. Centrifugal selection of signal-directed pecking. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974 Sep;22(2):341–355. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.22-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J. E. Schedules of electric shock presentation in the behavioral control of imprinted ducklings. J Exp Anal Behav. 1972 Sep;18(2):305–321. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1972.18-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEWS P. B. The effect of multiple S delta periods on responding on a fixed-interval schedule. J Exp Anal Behav. 1962 Jul;5:369–374. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1962.5-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deich J. D., Wasserman E. A. Rate and temporal pattern of key pecking under autoshaping and omission schedules of reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1977 Mar;27(2):399–405. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1977.27-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein R. J., Loveland D. H. Food-avoidance in hungry pigeons, and other perplexities. J Exp Anal Behav. 1972 Nov;18(3):369–383. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1972.18-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman H. S., Stratton J. W., Newby V. Punishment by response-contingent withdrawal of an imprinted stimulus. Science. 1969 Feb 14;163(3868):702–704. doi: 10.1126/science.163.3868.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh S. R., Navarick D. J., Fantino E. "Automaintenance": the role of reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974 Jan;21(1):117–124. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.21-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevin J. A. Differential reinforcement and stimulus control of not responding. J Exp Anal Behav. 1968 Nov;11(6):715–726. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1968.11-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palya W. L. Sign-tracking with an interfood clock. J Exp Anal Behav. 1985 May;43(3):321–330. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1985.43-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci J. A. Key pecking under response-independent food presentation after long simple and compound stimuli. J Exp Anal Behav. 1973 May;19(3):509–516. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1973.19-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal E. F. Exteroceptive control of fixed-interval responding. J Exp Anal Behav. 1962 Jan;5(1):49–57. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1962.5-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesp R. K., Lattal K. A., Poling A. D. Punishment of autoshaped key-peck responses of pigeons. J Exp Anal Behav. 1977 May;27(3):407–418. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1977.27-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessells M. G. The effects of reinforcement upon the prepecking behaviors of pigeons in the autoshaping experiment. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974 Jan;21(1):125–144. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.21-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Williams H. Auto-maintenance in the pigeon: sustained pecking despite contingent non-reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1969 Jul;12(4):511–520. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1969.12-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]