Abstract

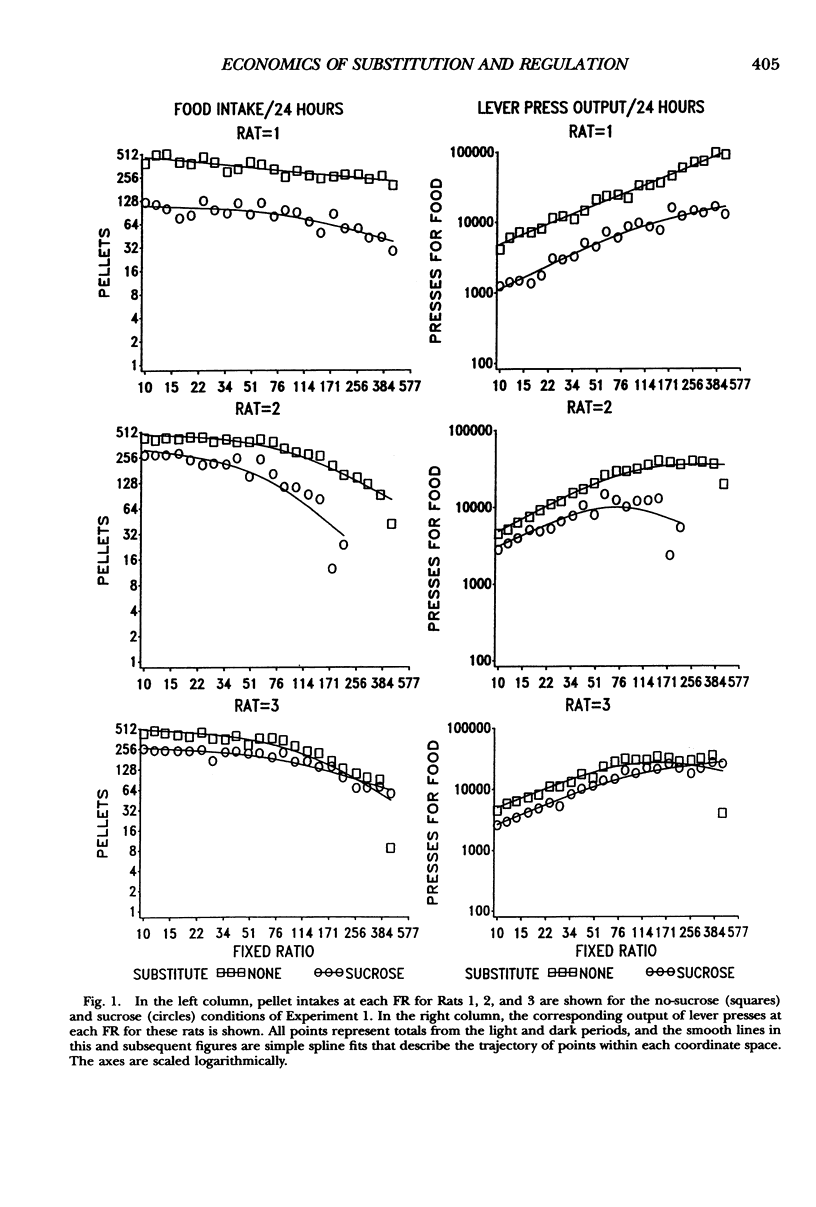

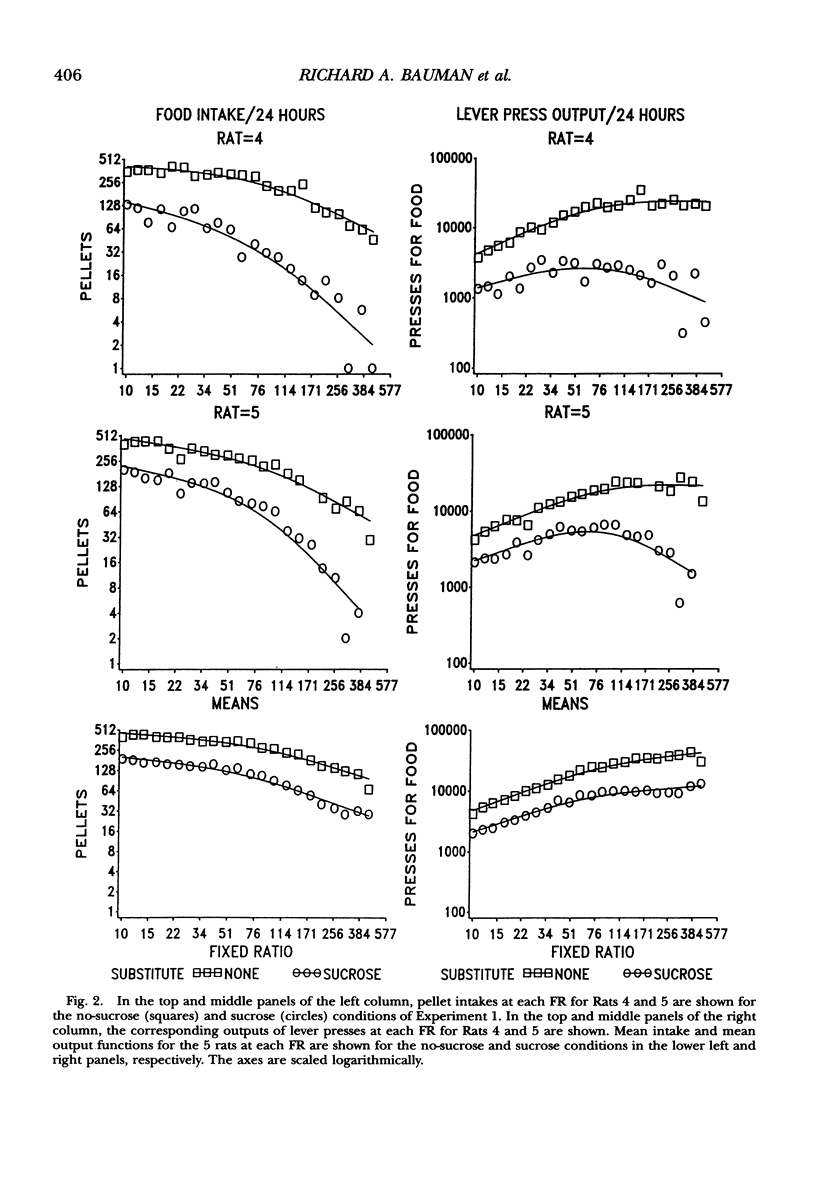

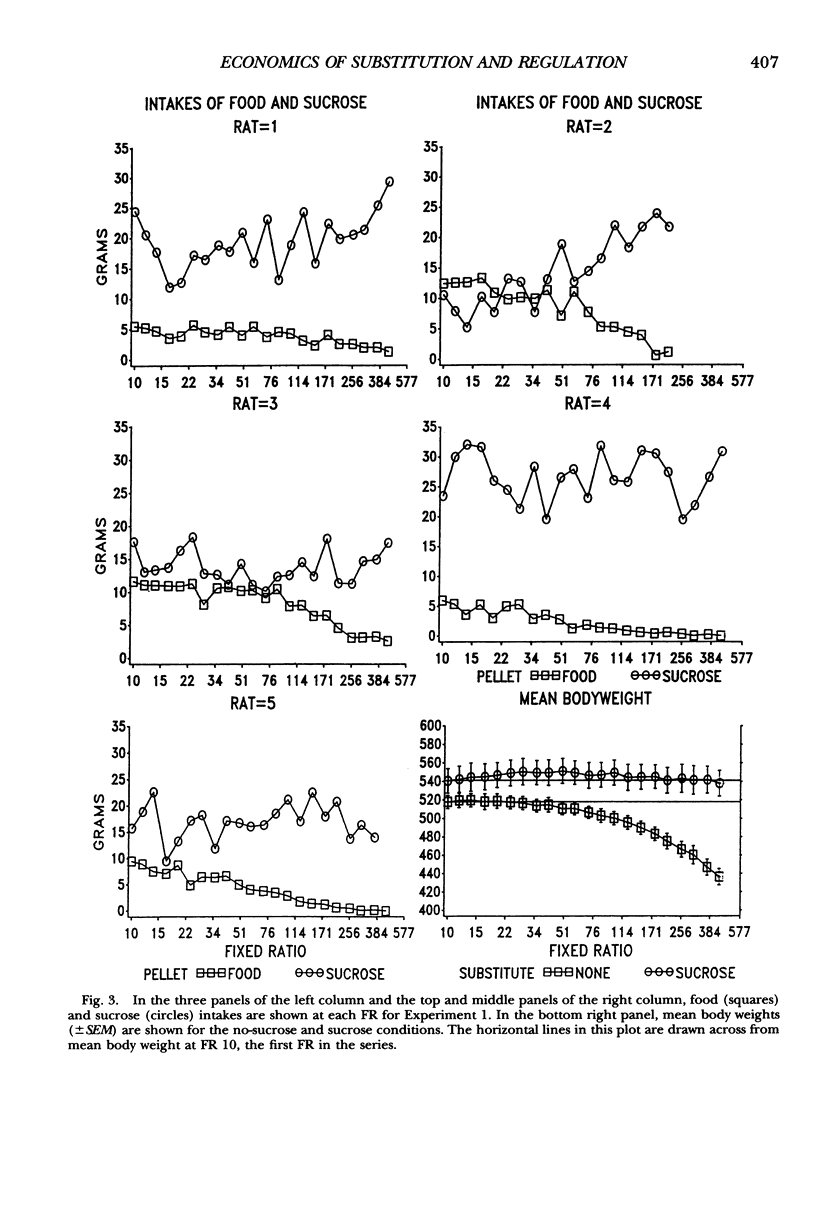

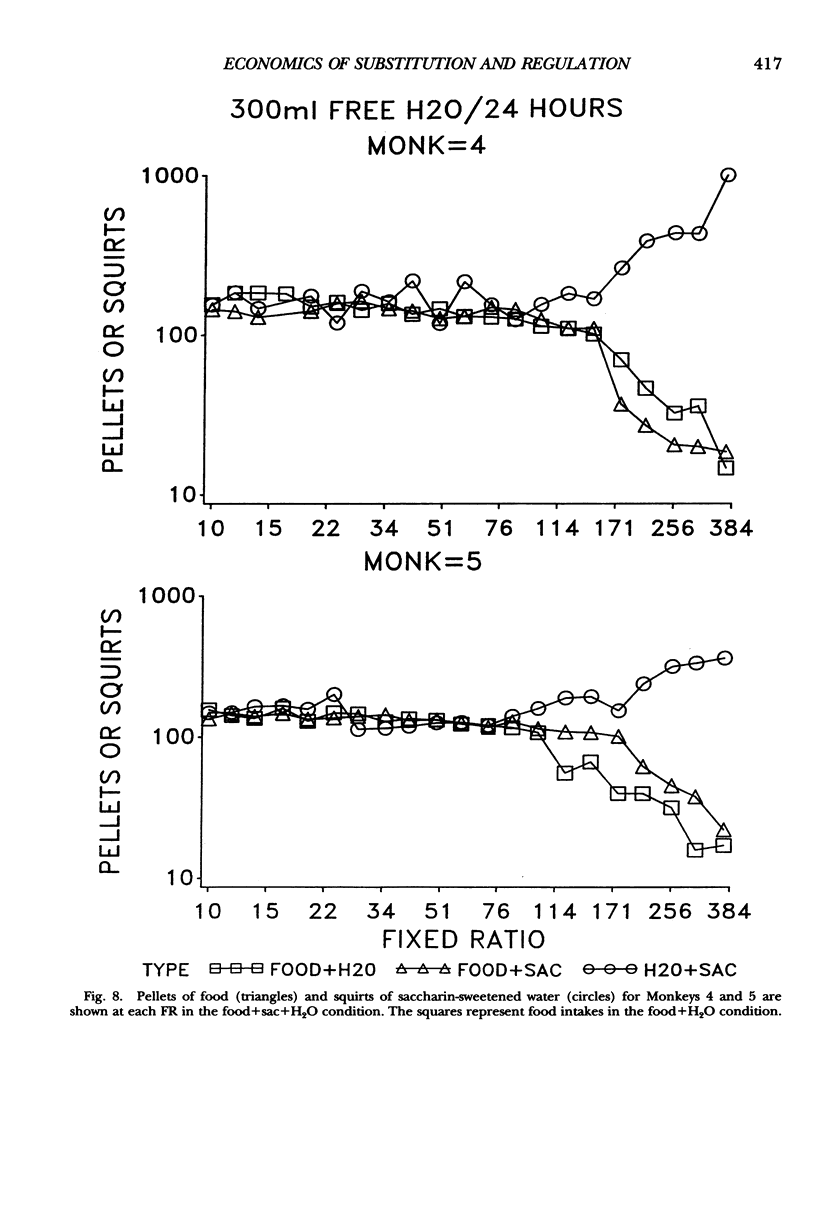

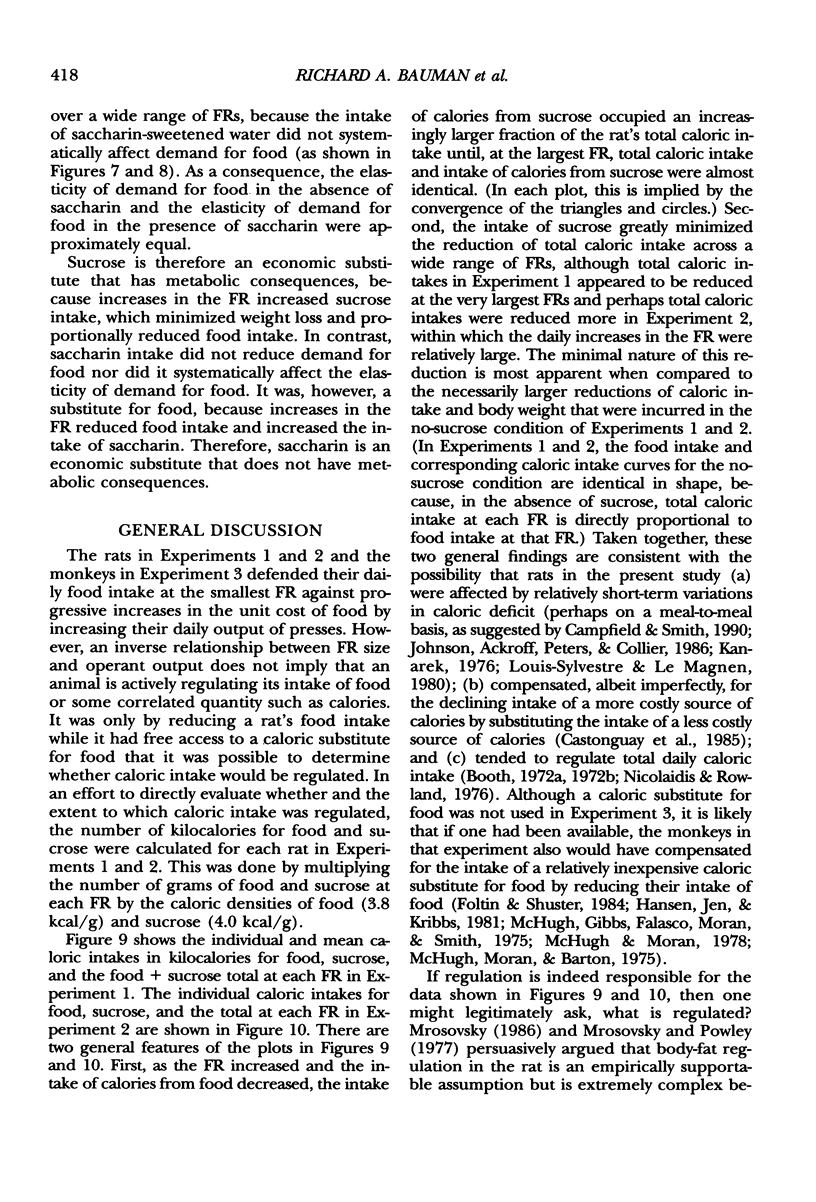

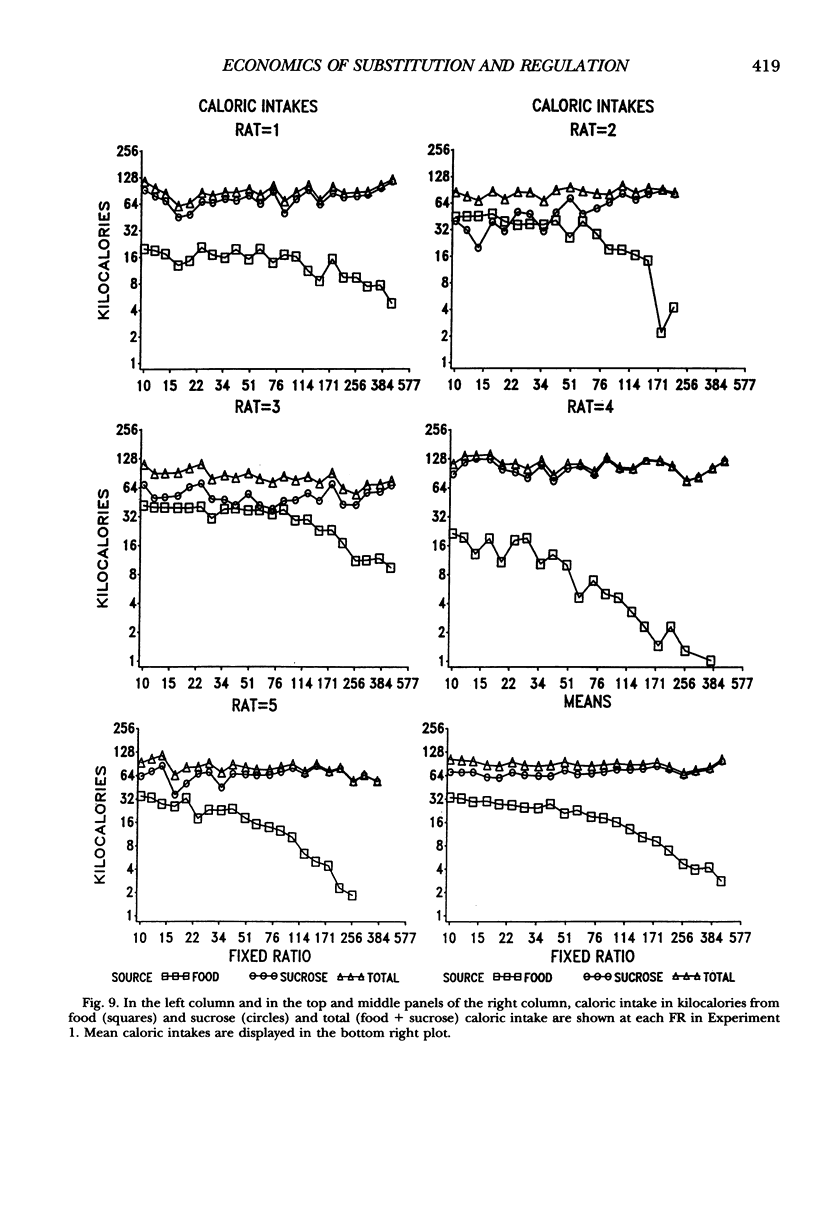

Three experiments were conducted to study the effect of an imperfect substitute for food on demand for food in a closed economy. In Experiments 1 and 2, rats pressed a lever for their entire daily food ration, and a fixed ratio of presses was required for each food pellet. In both experiments, the fixed ratio was held constant during a daily session but was increased between sessions. The fixed ratio was increased over a series of daily sessions once in the absence of concurrently available sucrose and again when sucrose pellets were freely available. For both series, increases in the fixed ratio reduced food intake, but body weight was reduced only in the no-sucrose condition. In the sucrose condition, body weight and total caloric intake (sucrose plus food) were relatively unaffected by increases in the fixed ratio. At all fixed ratios, food intake was proportionally reduced by the intake of sucrose. In Experiment 3, monkeys obtained food or saccharin by pressing keys; the fixed ratio of presses per food pellet was increased once when tap water was each monkey's only source of fluid, again when each monkey's water was sweetened with saccharin, and a third time when each monkey had concurrent access to the saccharin solution and plain water. Increases in the fixed ratio, but not the intake of the saccharin solution, reduced each monkey's food intake. Because neither rats' sucrose nor monkeys' saccharin intakes affected the slope of the respective demand curves for food, monkeys and rats increased their daily output of presses and thereby defended their daily intake of those complementary elements of food. However, sucrose reduced rats' food intake. The relative constancy of body weight and total caloric intake in the sucrose condition is consistent with the possibility that rats tended to regulate caloric intake.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bauman R. A., Kant G. J. Time cost of alternation reduced demand for food in a closed economy. Physiol Behav. 1995 Jun;57(6):1187–1193. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00038-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman R. A. The effects of wheel running, a light/dark cycle, and the instrumental cost of food on the intake of food in a closed economy. Physiol Behav. 1992 Dec;52(6):1077–1083. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90462-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman R. An experimental analysis of the cost of food in a closed economy. J Exp Anal Behav. 1991 Jul;56(1):33–50. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1991.56-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth D. A. Caloric compensation in rats with continuous or intermittent access to food. Physiol Behav. 1972 May;8(5):891–899. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(72)90302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth D. A. Satiety and behavioral caloric compensation following intragastric glucose loads in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1972 Mar;78(3):412–432. doi: 10.1037/h0032291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castonguay T. W., Hirsch E., Collier G. Palatability of sugar solutions and dietary selection? Physiol Behav. 1981 Jul;27(1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90292-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin R. W., Schuster C. R. Response of monkeys to intragastric preloads: limitations on caloric compensation. Physiol Behav. 1984 Nov;33(5):791–798. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen B. C., Jen K. L., Kribbs P. Regulation of food intake in monkeys: response to caloric dilution. Physiol Behav. 1981 Mar;26(3):479–486. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90177-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh S. R. Behavioral economics. J Exp Anal Behav. 1984 Nov;42(3):435–452. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1984.42-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh S. R., Raslear T. G., Shurtleff D., Bauman R., Simmons L. A cost-benefit analysis of demand for food. J Exp Anal Behav. 1988 Nov;50(3):419–440. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1988.50-419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh S. R., Winger G. Normalized demand for drugs and other reinforcers. J Exp Anal Behav. 1995 Nov;64(3):373–384. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1995.64-373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D. F., Ackroff K., Peters J., Collier G. H. Changes in rats' meal patterns as a function of the caloric density of the diet. Physiol Behav. 1986;36(5):929–936. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanarek R. B. Energetics of meal patterns in rats. Physiol Behav. 1976 Sep;17(3):395–399. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(76)90097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea S. E., Roper T. J. Demand for food on fixed-ratio schedules as a function of the quality of concurrently available reinforcement. J Exp Anal Behav. 1977 Mar;27(2):371–380. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1977.27-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis-Sylvestre J., Le Magnen J. Fall in blood glucose level precedes meal onset in free-feeding rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1980;4 (Suppl 1):13–15. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(80)90041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh P. R., Gibbs J., Falasco J. D., Moran T., Smith G. P. Inhibitions of feeding examined in rhesus monkeys with hypothalamic disconnexions. Brain. 1975 Sep;98(3):441–454. doi: 10.1093/brain/98.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh P. R., Moran T. H., Barton G. N. Satiety: a graded behavioural phenomenon regulating caloric intake. Science. 1975 Oct 10;190(4210):167–169. doi: 10.1126/science.1166310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran T. H., McHugh P. R. Distinctions among three sugars in their effects on gastric emptying and satiety. Am J Physiol. 1981 Jul;241(1):R25–R30. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1981.241.1.R25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrosovsky N. Body fat: what is regulated? Physiol Behav. 1986;38(3):407–414. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrosovsky N., Powley T. L. Set points for body weight and fat. Behav Biol. 1977 Jun;20(2):205–223. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6773(77)90773-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuringer A. J. Animals respond for food in the presence of free food. Science. 1969 Oct 17;166(3903):399–401. doi: 10.1126/science.166.3903.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevin J. A., Mandell C., Atak J. R. The analysis of behavioral momentum. J Exp Anal Behav. 1983 Jan;39(1):49–59. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1983.39-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevin J. A., Smith L. D., Roberts J. Does contingent reinforcement strengthen operant behavior? J Exp Anal Behav. 1987 Jul;48(1):17–33. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1987.48-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaïdis S., Rowland N. Metering of intravenous versus oral nutrients and regulation of energy balance. Am J Physiol. 1976 Sep;231(3):661–668. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.231.3.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overmann S. R. Dietary self-selection by animals. Psychol Bull. 1976 Mar;83(2):218–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck J. W. Rats defend different body weights depending on palatability and accessibility of their food. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1978 Jun;92(3):555–570. doi: 10.1037/h0077474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers P. J., Carlyle J. A., Hill A. J., Blundell J. E. Uncoupling sweet taste and calories: comparison of the effects of glucose and three intense sweeteners on hunger and food intake. Physiol Behav. 1988;43(5):547–552. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(88)90207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclafani A. Carbohydrate taste, appetite, and obesity: an overview. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1987 Summer;11(2):131–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclafani A. Carbohydrate-induced hyperphagia and obesity in the rat: effects of saccharide type, form, and taste. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1987 Summer;11(2):155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(87)80020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEISKRANTZ L. Effects of medial temporal lesions on taste preference in the monkey. Nature. 1960 Sep 3;187:879–880. doi: 10.1038/187879b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtshafter D., Davis J. D. Set points, settling points, and the control of body weight. Physiol Behav. 1977 Jul;19(1):75–78. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(77)90162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young P. T. Hedonic organization and regulation of behavior. Psychol Rev. 1966 Jan;73(1):59–86. doi: 10.1037/h0022630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]