Abstract

Objectives:

This long-term prospective study describes the effect of myotomy in patients who fail to respond to repeated pneumatic dilations and compares their clinical course with that of patients responding to dilation therapy.

Methods:

Nineteen consecutive patients who had never reached a clinical remission after repeated pneumatic dilation underwent myotomy. Their clinical course was compared with that of patients who had reached a clinical remission after a single (n = 34) or multiple (n = 14) pneumatic dilation(s). Symptoms were graded with a previously described symptom score ranging from 0 to 12. Remission was defined as a score of 3 or less persisting for at least 6 months. Duration of remission was summarized using Kaplan Meier survival curves. Association between baseline factors and the need for surgery was evaluated using logistic regression.

Results:

Complete follow-up was obtained for 98.5% of the patients. The median duration of follow-up was similar in patients treated by myotomy (10.0 years), in patients reaching a clinical remission after a single dilation (10.6 years), but differed in patients undergoing repeated dilations (6.9 years). The 10-year remission rate was 77% (95% CI 53–100%) in patients undergoing myotomy, 72% (95% CI: 56–87%) in patients “successfully” treated with a single pneumatic dilation and 45% (95% CI: 16–73%) in patients undergoing several dilations. Among all baseline factors investigated, young age was associated with an increased need of surgery.

Conclusions:

Myotomy is an effective treatment modality in patients with achalasia who have failed to respond to pneumatic dilation. Young patients may benefit from primary surgical therapy.

Patients with achalasia undergoing myotomy for failed pneumatic dilation were prospectively followed for a median of 10 years. Their outcome was at least as favorable as that of patients having an optimal response to a single pneumatic dilation. Previous dilations did not render surgery more difficult.

Controversy exists with regard to the most optimal therapy for achalasia. None of the available therapeutic methods can reverse the neurologic abnormalities, consisting of a marked reduction or lack of ganglionic cells in Auerbach's plexus, a Wallerian degeneration of extraesophageal nerve fibers and perhaps fewer neurones in the dorsal vagal nucleus.1–5 Therefore, any type of therapy for these patients is strictly palliative. Currently, only 2 treatment modalities promise a long-term relief from dysphagia and regurgitation, namely pneumatic dilation and Heller myotomy. Both methods have different characteristics: pneumatic dilation may cause a too low reduction of lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure and only little improvement in symptoms, and myotomy may have the opposite effect, leading to a higher frequency of gastroesophageal reflux. The results of a single randomized controlled study6 suggest that surgery may be more effective than myotomy in the long-term management of patients with achalasia. However, this study has been criticized for its less than optimal method of pneumatic dilation.7 Thus, at the present time, the optimal therapy for patients with achalasia remains to be determined.

An even greater therapeutic challenge arises in patients who fail to respond to either one of these treatment modalities. There is no prospective controlled study that investigates the effect of surgical myotomy in patients not responding to repeated pneumatic dilation. In fact, it remains unclear whether patients who had previously undergone pneumatic dilation are more difficult to treat surgically. While Patti et al8 encountered no difficulties when dissecting the different anatomic planes in patients who had previously been treated by pneumatic dilation, others9,10 emphasized that surgery is technically more demanding in this situation and occasionally leads to mucosal perforation. Furthermore, there is almost no information on the long-term outcome in patients who have been treated by dilation and subsequently required surgery.

In 1980, we began a prospective long-term observation in patients with achalasia with the aim to determine their long-term clinical course.11 The current analysis is aimed at answering the following questions. (1) What is the long-term clinical course in patients undergoing surgery after failed pneumatic dilations in comparison with that of patients showing an “optimal response” to a single dilation therapy? (2) Does a preceding pneumatic dilation adversely affect the performance of a Heller myotomy and does it increase perioperative morbidity? (3) Does clinical information obtained at initial presentation allow one to predict the eventual requirement of surgery?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Since 1980, all patients with achalasia who were diagnosed and treated at a single institution were prospectively followed and observed. Patients were included in this study if their first treatment was initiated by the senior investigator (V.F.E.) and if they were followed for a minimum of 5 years after either “successful” pneumatic dilation or myotomy. In each instance, the diagnosis of achalasia was based on manometric, radiographic, and endoscopic findings. Patients undergoing myotomy were operated on by the same surgeon (Th.J.). At the time of diagnosis, 6 months after therapy, and then in 2-year intervals thereafter, all patients underwent structured interviews in which specific questions concerning the frequency of dysphagia, regurgitation, and chest pain as well as the degree of weight loss were asked. In addition, a final interview was performed in the fall of 2001 when the study was terminated. All patients were followed until death or until the final interview in 2001, with the exception of a single patient who was lost to follow-up at 5 years following initial therapy.

Between January 1980 and September 1996, a total of 86 patients were diagnosed for the first time to suffer from primary achalasia. For the following reasons, 11 of them were excluded from further analysis: 6 patients were treated in outside institutions, 2 patients refused any therapy, and 3 were considered too ill for invasive therapy. The remaining 75 patients were prospectively followed and investigated. They were divided into 4 different groups. Group A consisted of patients who had reached a clinical remission (symptom score of 3 or less persisting for at least 6 months) after a single pneumatic dilation (n = 34). Group B included patients who had a remission after the second or third dilation (n = 14). Group C consisted of patients who did not achieve remission after a third dilation or who requested an alternative therapy after dilation had failed (n = 19). Group D included 8 patients who preferred surgery as the primary procedure. All patients failing pneumatic dilation underwent myotomy. In addition, the outcome of patients undergoing myotomy for failed pneumatic dilation was compared with an identical number of patients responding to a single dilation and having a similar sex and age distribution as well as a similar length of follow-up (Group A(m)). Table 1 shows the demographic data for the different patient groups.

TABLE 1. Demographic Data

The median total duration of follow-up was 10.6 years in patients undergoing myotomy for failed pneumatic dilation (Group C), 10.0 years in patients who were successfully treated with a single dilation (Group A), 6.9 years in patients requiring several dilations to reach a clinical remission (Group B), and 8.5 years in patients primarily treated by myotomy (Group D).

Evaluation of Symptoms

At the initial investigation and at each follow-up, structured interviews were performed using a previously described scoring system.12 Depending on whether dysphagia, regurgitation, and chest pain occurred occasionally, daily, or several times during the day, a symptom score ranging from 0 to 3 was determined. In addition, a symptom score of 0 to 3 was assigned to the degree of weight loss (Table 2). Thus, a completely asymptomatic patient would have a symptom score of 0, whereas a severely affected patient could have a symptom score up to 12. Patients were considered to have reached a clinical remission if symptoms had totally disappeared or if they had improved by at least 2 points and did not exceed a score of 3 over a period of at least 6 months after therapy.

TABLE 2. Clinical Classification of Achalasia

Manometric and Radiographic Investigations

All patients underwent esophageal manometry with the use of a low-compliance capillary perfusion method.11 During this procedure, the LES resting pressure and relaxation as well as esophageal body motility occurring in response to 10 wet swallows were recorded. In 9 (12%) of the 75 patients, the manometric tube assembly could not be passed through the LES, and recordings were restricted to esophageal body motility. These investigations were repeated 4 weeks after the initial pneumatic dilation.

Radiographic studies were performed in the prone, prone-oblique, and upright position. The maximum caliber of the esophageal body and the caliber of the esophagogastric junction at its narrowest diameter were measured and recorded. Only 2 patients, who had undergone radiographic studies in an outside institution, were excluded from this analysis.

Pneumatic Dilation

All pneumatic dilations were carried out by the senior investigator (V.F.E.) using a Browne-McHardy pneumatic dilator under fluoroscopic control. The day before the dilations, the patients’ diet consisted of liquids only. The balloon of the dilator was placed at the gastroesophageal junction and inflated to a minimum pressure of 6 psi. Depending on a patient's actual tolerance, pressures ranged from 6 to 12 psi with the aim of maintaining this pressure for approximately 2 minutes. All patients who maintained a symptom-score of > 3 or redeveloped this score during his or her further clinical course received repeated dilations. Patients also underwent repeated dilations if their symptom score did not decrease by a minimum of 2 or if the patient elected additional therapy.

Myotomy

In patients of group C, myotomy was performed if 3 consecutive pneumatic dilations had failed to induce a clinical remission (n = 7) or if the patient elected an alternative treatment modality after 1 (n = 3) or 2 unsuccessful pneumatic dilation(s) (n = 9). The median time between the first pneumatic dilation and the performance of myotomy was 2 years (range: 0.2–12.3 years). In all patients undergoing surgery, Heller myotomy was carried out by a single surgeon (Th.J.) during conventional laparotomy and was always combined with a partial anterior fundoplication (Dor procedure).13

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was focused on determining the recurrence-free survival for different patient groups using Kaplan Meier survival curves.14 Patient characteristics, symptoms, as well as manometric and radiologic measurements were described using summary statistics and were calculated for each group separately. Quantitative variables were summarized using counts (n), means, standard deviations (SD), medians and range, ie, minimum and maximum of values. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CI) for the difference of means were estimated on the basis of the t-distribution. Qualitative or categorical variables are described using frequencies (n), percentages (%), and the exact 95% CI for proportions.15

The association between baseline factors and the need for surgery was investigated using a logistic regression model. Baseline factors considered in this analysis were sex, age, duration of symptoms, symptom score, LESP, and esophageal body diameter. The forward selection method was implemented to select the factors more highly associated with the need for surgery. The validity of the model was checked using sensitivity analyses based on models including interaction terms and investigating linearity assumptions for the effects of covariates. For the factors included in the final model, the estimated odds ratios and the corresponding 95% CI15 are presented.

RESULTS

Clinical Effectiveness

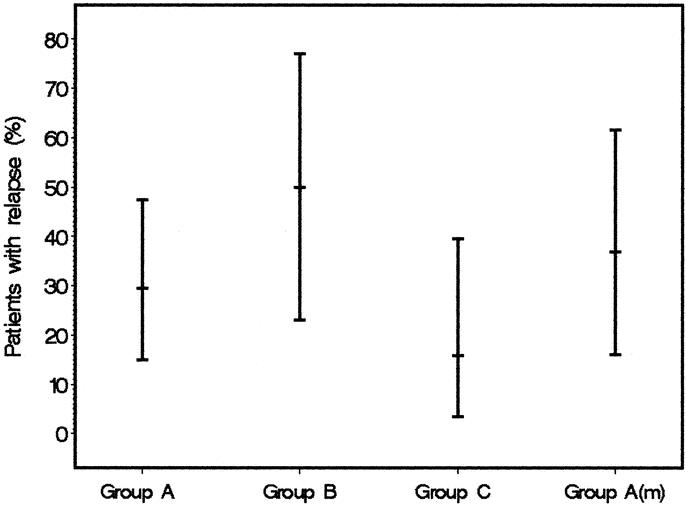

As shown in Figure 1, patients undergoing myotomy for failed pneumatic dilation (Group C) had a median decrease in symptom score of 7 points while patients showing a clinical remission after a single pneumatic dilation decreased their symptom score by a median of 5 points. The findings were again similar for matched patients of Group A (median decrease in symptom score: 7 points) and for patients who had reached a clinical remission only after repeated dilations (median decrease in symptom score: 7.5 points). Sixteen percent of patients (n = 3) undergoing myotomy (Group C) for failed pneumatic dilation fulfilled the criteria of a clinical relapse by reaching a symptom score of 4. However, these patients still felt significantly improved and elected to have no further therapy. In contrast, relapses occurred in 29% of patients in Group A and 50% of patients in Group B (Fig. 2). Two patients in Group A and 2 further patients in Group B became resistant to dilation therapy and required surgery during their further clinical course. None of the 8 patients treated primarily by myotomy developed a clinical relapse. Two of them reached a maximum symptom score of 3, one reached a maximum symptom score of 2, two reached a maximum symptom score of 1, and three remained completely asymptomatic throughout the observation period.

FIGURE 1. Change in symptom score from the time of diagnosis to the last follow-up. Data are shown as boxplots (median; minimum; 1st, 2rd, and 3rd quartile; maximum) for all 4 patient groups (Group A = patients reaching a clinical remission after a single dilation [A(m) = subgroup matched with Group C], Group B = patients reaching a clinical remission after repeated dilations, Group C = patients undergoing myotomy after failed pneumatic dilation).

FIGURE 2. Relapse rate and the corresponding 95% CI for all patient groups. (Group A = patients reaching a clinical remission after a single dilation [A(m) = subgroup matched with Group C], Group B = patients reaching a clinical remission after repeated dilations, Group C = patients undergoing myotomy after failed pneumatic dilation).

Figure 3 details the Kaplan Meier estimates for time in remission in 4 different patient groups. A total of 7 patients (9%) had died (2 patients of Group A, 3 of Group B, 1 of Group C, and 1 of Group D) during the course of the study and were censored at the time of death. In 3 instances, death had occurred as a consequence of cardiovascular disease and the 4 remaining patients had died of extraesophageal malignant neoplasms. In addition, 1 patient was censored for loss to follow-up. The 10-year remission rate after myotomy for failed pneumatic dilation (77%, 95% CI: 53–100%) was comparable to the 10-year remission rate of patients responding to a single pneumatic dilation (72%, 95% CI: 56–87%) and slightly but not significantly worse than that of patients who were primarily treated by myotomy (100%). A less favorable prognosis was found in patients who required several pneumatic dilations to induce a clinical remission. Their 10-year remission rate was 45% (95% CI: 16–73%).

FIGURE 3. Probability of staying in remission (%) according to Kaplan-Meier for all patient groups (Group A = patients reaching a clinical remission after a single dilation [A(m) = subgroup matched with Group C], Group B = patients reaching a clinical remission after repeated dilations, Group C = patients undergoing myotomy after failed pneumatic dilation).

Effect of Therapy on Radiographic and Manometric Findings

Eighteen of the 19 patients (95%) treated by myotomy for failed pneumatic dilation and all patients undergoing pneumatic dilation underwent radiographic investigations prior and following therapy. Posttherapeutic manometric data were obtained in 17 of 19 patients of Group A(m) after pneumatic dilation but in only 7 of the surgically treated patients. As shown in Table 3, a single pneumatic dilation (Group A(m)) resulted in a similar change in the diameter of the esophageal body and the width of the gastric cardia when compared with patients undergoing myotomy (Group C). In contrast, the change in LES pressure appeared to be more pronounced after myotomy.

TABLE 3. Change in Radiographic Findings and LES Pressure After Myotomy (Group C) and After “Successful” Treatment by Single Pneumatic Dilation (Group A(m))

Complications Related to Pneumatic Dilation and Myotomy

Patients included in Group A and B (total n = 47) underwent a total of 78 pneumatic dilations. Nine of these dilations were followed by a temporary increase in retrosternal pain and 2 patients developed intramural hematomas, which regressed spontaneously. Two additional patients displayed a postdilation diverticulum at the gastric cardia. One perforation occurred and was successfully treated without surgery. Late complications occurred in 3 patients and consisted in the development of reflux symptoms, 2 of whom were associated with erosive esophagitis.

No complications were observed in the patients undergoing myotomy. In no instance was the surgical technique adversely affected by previous dilations. Also, there was no evidence for the presence of submucosal fibrosis at or near the esophagogastric junction. Only 1 patient developed symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux with erosive esophagitis but was successfully treated with acid suppressing medications.

Predictors of Requirement for Surgical Myotomy

During prolonged observation, 23 (34%) of the 67 patients primarily treated with pneumatic dilation eventually underwent surgical myotomy (19 from Group C and 4 additional patients from Groups A and B who experienced late recurrences that did not respond to further dilations). None of the clinical parameters determined at initial presentation (duration of symptoms, symptom score, LESP, and diameter of the esophageal body) were seen to be associated with the requirement for surgery. However, there was a strong association between age at which the diagnosis of achalasia was first established and the requirement of surgery. For each year of increasing age, the odds ratio for the eventual requirement of myotomy decreased by 0.943 (95% CI: 0.90–0.98). If these data were translated into the risk of eventual myotomy, the following information could be obtained: a patient who is diagnosed to have achalasia at age 15 has a 70% (95% CI: 58–80%) chance to eventually undergo myotomy, while this risk decreases in a 40-year-old patient to 35% (95% CI: 32–39%) and in a 70-year-old patient to 8% (95% CI: 4–18%). Figure 4 shows the calculated risk, including the 95% CI for different ages, ranging from 15 to 70 years.

FIGURE 4. Probability (with corresponding 95% CI) for the need of surgery according to the patient's age at first diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that patients undergoing surgical myotomy (Group C) for failed pneumatic dilation have an excellent prognosis that is at least as favorable as that of patients who respond to a single dilation (Group A). In the patients included in this study, there was no evidence that repeated dilations render surgery more difficult. Finally, as the eventual requirement of surgery appears to be a function of age, it is suggested that young patients should be preferably treated with myotomy.

Until now, it has remained unclear whether patients with achalasia who do not respond to repeated pneumatic dilations are also more difficult to treat surgically. Most studies addressing this issue are retrospective and have applied different therapeutic strategies.9,10,16–19 In these studies, it has been suggested that more than 80% of all surgically treated patients experience a significant improvement in symptoms. However, such conclusions are not only limited by the retrospective nature of previous investigations but also by the fact that the definitions for clinical remission were vague and that follow-up was either incomplete or too short to allow reliable conclusions. The current study overcomes several of these methodological shortcomings: (1) all patients were prospectively followed and reinvestigated in 2-year intervals; (2) stringent criteria for clinical remission were used; (3) pneumatic dilations and surgical procedures were each performed by a single gastroenterologist and surgeon therefore maintaining a constant treatment modality; and (4) follow-up extended from a minimum of 5 years to a maximum of 18 years and was obtained in all but 1 patient until death or until the conclusion of this study in the fall of 2001.

The results suggest that surgery for failed pneumatic dilation leads to a similar long-term outcome when compared with that of patients who were successfully treated with a single pneumatic dilation. A comparison of the outcome of the former patient group with that of patients requiring several dilations to achieve a clinical remission suggests that patients requiring surgery for failed pneumatic dilations have a more favorable long-term prognosis. The question must therefore be raised whether failed pneumatic dilation is an indication for immediate surgery rather than repeated dilative procedures. However, it is accepted that these observations are based on a small number of patients undergoing surgery for failed pneumatic dilation and that differences in outcome between subgroups were not dramatic. It remains unclear whether the current observation obtained in this single institution can be extrapolated to the general population of patients with achalasia. Further clarifications could be expected from multicenter investigations. However, in view of the fact that reliable conclusions not only require large patient numbers but also intensive follow-up over a period of several years, it is questionable that such an ideal prospective study will be viable in the near future.

Controversy exists as to whether previous dilations render surgery more difficult and thus impair the outcome of this procedure. In patients treated with botulinium toxin injections, a marked fibrotic reaction at the gastroesophageal junction has been described8,20 and has occasionally led to difficulties in dissecting the different esophageal planes. Although it has been suggested that previous pneumatic dilations do not affect the final outcome of surgery,16,17 some authors have noted that dissection and myotomy are technically more challenging in these patients.9,10,19 One might speculate that the slightly better long-term clinical course of patients primarily treated by myotomy supports the latter assumption. However, the current data do not allow this conclusion for the following reasons. First, patients undergoing primary myotomy largely differed in numbers compared with patients treated surgically for failed pneumatic dilation. Second, the differences in long-term outcome between the 2 groups were minor and did not reach statistical significance. Thus, in the patients reported in this study, previous dilations did not affect the surgical technique, nor did such therapy affect outcome. However, it should be noted that we restricted pneumatic dilations to a maximum of 3 consecutive treatment sessions. The possibility remains that larger number of dilations may adversely affect surgery, as has been occasionally described in previous publications.8

Studies investigating the long-term effectiveness of pneumatic dilation have reported “success rates” ranging from 50% to 85%.10,11,21–23 These discrepancies in therapeutic efficacy might possibly be explained by differences in completeness and length of follow-up or by differences in definition of success. In the current investigation, in which all patients were prospectively followed for a median of almost 10 years (range: 2.8–17.5), and in which stringent criteria for remission were used, 34% (n = 23) of all patients eventually required surgical therapy either for failed pneumatic dilation (n = 19) or for late recurrences (n = 4). Such treatment failures not only hamper patient satisfaction but also may increase the rate of complications as well as costs of therapy.24,25

In the hope to optimize treatment of achalasia and to tailor such therapy to the individual patient, several authors have attempted to determine predictors for success of certain treatment modalities. For pneumatic dilation, it has been suggested that advanced age, a moderately dilated esophagus and a long history of symptoms predict favorable treatment results.22,27–32 However, little agreement exists as to whether all or only some of these criteria represent significant risk factors for therapeutic failure. In this prospective study, a logistic regression model was used to determine the association between potential risk factors and the eventual need for surgery. The results clearly show that only young age is strongly associated with a poor outcome of pneumatic dilation. As age increases, the need for surgical therapy progressively diminishes. From these findings and previous observations (22,27–28,31) it is concluded that young patients should have the option of primary surgical therapy.

In the past, an all too optimistic view of the efficacy of pneumatic dilation as well as a widespread skepticism with regard to the cost and morbidity of surgery have led many gastroenterologist to recommend pneumatic dilation as primary therapy for all patients with achalasia. However, considering the accumulating long-term results of this procedure,23 the success of surgery in patients resistant to dilation and the recently made improvements in surgical techniques,33 this oversimplified therapeutic approach has to be questioned. In view of these more recent data and the current findings, we believe that a randomized trial comparing pneumatic dilation with laparoscopic myotomy is urgently required. If such a trial should ever be initiated, stratification of patient groups according to age at diagnosis should be an essential part of its design.

Footnotes

Reprints: Prof. Dr. Volker F. Eckardt, Deutsche Klinik für Diagnostik, Aukammallee 33, 65191 Wiesbaden, Germany. E-mail: eckardt.gastro@dkd-wiesbaden.de.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cassella RR, Brown ALJr, Sare GP, et al. Achalasia of the esophagus: pathologic and etiologic considerations. Ann Surg. 1964;160:474–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hurst AF, Rake GW. Achalasia of the cardia. Q J Med. 1930;23:491–507. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith B. The neurological lesion in achalasia of the cardia. Gut. 1970;11:388–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lendrum FC. Anatomic features of the cardiac orifice of the stomach with special reference to cardiospasm. Arch Intern Med. 1937;59:474–511. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Misiewicz JJ, Waller SL, Anthony PP, et al. Achalasia of the cardia: pharmacology and histopathology of isolated cardiac sphincteric muscle from patients with and without achalasia. Q J Med. 1969;38:17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csendes A, Braghetto I, Henriquez A, et al. Late results of a prospective randomised study comparing forceful dilatation and oesophagomyotomy in patients with achalasia. Gut. 1989;30:299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richter JE. Surgery or pneumatic dilatation for achalasia: a head-to-head comparison. Now are all the questions answered? Gastroenterology. 1989;97:1340–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patti MG, Feo CV, Arcerito M, et al. Effects of previous treatment on results of laparoscopic Heller myotomy for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:2270–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morino M, Rebecchi F, Festa V, et al. Preoperative pneumatic dilatation represents a risk factor for laparoscopic Heller myotomy. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:359–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vantrappen G, Hellemans J, Deloof W, et al. Treatment of achalasia with pneumatic dilatations. Gut. 1971;12:268–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckardt VF, Aignherr C, Bernhard G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1732–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckardt VF. Clinical presentation and complications of achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:281–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dor J, Humbert P, Dor V, et al. L’ interet de la technique de Nissen modifiee dans la prevention du reflux apres cardiomyotomie extra-muquese de Heller. Mem Acad Chir (Paris). 1962;88:877–884. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner MJ, Altman DG. Estimating with confidence. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1988;296:1210–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferguson MK, Reeder LB, Olak J. Results of myotomy and partial fundoplication after pneumatic dilation for achalasia. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62:327–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holzman MD, Sharp KW, Ladipo JK, et al. Laparoscopic surgical treatment of achalasia. Am J Surg. 1997;173:308–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ponce J, Juan M, Garrigues V, et al. Efficacy and safety of cardiomyotomy in patients with achalasia after failure of pneumatic dilation. Dig Dis Sci. 1999;44:2277–2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beckingham IJ, Callanan M, Louw JA, et al. Laparoscopic cardiomyotomy for achalasia after failed balloon dilatation. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:493–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horgan S, Hudda K, Eubanks T, et al. Does botulinum toxin injection make esophagomyotomy a more difficult operation? Surg Endosc. 1999;13:576–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West RL, Hirsch DP, Bartelsman Katz PO, et al. Pneumatic dilatation is effective long-term treatment for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1973–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parkman HP, Reynolds JC, Ouyang A, et al. Pneumatic dilatation or esophagomyotomy treatment for idiopathic achalasia: clinical outcomes and cost analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West RL, Hirsch DP, Bartelsman JFWM, et al. Long term results of pneumatic dilation in achalasia followed for more than five years. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1346–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nair LA, Reynolds JC, Parkman HP, et al. Complications during pneumatic dilation for achalasia or diffuse esophageal spasm. Analysis of risk factors, early clinical characteristics, and outcome. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1893–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richter JE. Comparison and cost analysis of different treatment strategies in achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:359–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robertson CS, Fellows IW, Mayberry JF, et al. Choice of therapy for achalasia in relation to age. Digestion. 1988;40:244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vantrappen G, Hellemans J. Achalasia. In: Diseases of the Esophagus. New York: Springer Verlag; 1974:287–354. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fellows IW, Ogilvie AL, Atkinson M. Pneumatic dilatation in achalasia. Gut. 1983;24:1020–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz PO, Gilbert J, Castell DO. Pneumatic dilatation is effective long-term treatment for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1973–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chawla YK, Dilawari JB, Reddy DN, et al. Pneumatic dilatation in achalasia cardia. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1987;6:101–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azizkhan RG, Tapper D, Eraklis A. Achalasia in childhood: a 20-year experience. J Pediatr Surg. 1980;15:457–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barnett JL, Eisenman R, Nostrant TT, et al. Witzel pneumatic dilation for achalasia: safety and long-term efficacy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:482–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaninotto G, Costantini M, Molena D, et al. Treatment of esophageal achalasia with laparoscopic Heller myotomy and Dor partial anterior fundoplication: Prospective evaluation of 100 consecutive patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]