Abstract

Objective:

To perform a meta-analysis of studies comparing open pyloromyotomy (OP) and laparoscopic pyloromyotomy (LP) in the treatment of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.

Background:

LP has become increasingly popular for the management of pyloric stenosis. Despite a decade of experience, the real benefit of LP over the open procedure remains unclear.

Methods:

Using a defined search strategy, studies directly comparing OP with LP were identified (n = 8). Data for infants treated by both approaches were extracted and used in our meta-analysis. OP and LP were compared in terms of complications, efficacy, operating time, and recovery time. Weighted mean difference (WMD) between continuous variables and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated. For dichotomous data, relative risk (RR) and 95% CI were determined.

Results:

Only 3 studies were prospective, and just 1 study was a prospective randomized controlled trial. Mucosal perforations and incomplete pyloromyotomy were both more common with LP. Compared with OP, LP is associated with higher complication rate (RR 0.81 [0.5, 1.29], P = 0.4), similar operating time (WMD 1.52 minutes [−0.26, 3.29], P = 0.09), shorter time to full feeds (WMD 8.66 hours [7.25, 10.07], P < 0.00001), and shorter postoperative length of stay (WMD 7.03 hours [3.74, 10.32], P = 0.00003).

Conclusions:

OP is associated with fewer complications and higher efficacy. Recovery time appears significantly shorter following LP. A prospective randomized controlled trial is warranted to fully investigate these and other outcome measures.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open pyloromyotomy for the treatment of infantile pyloric stenosis. The real benefits of one approach over the other remain unclear and a prospective randomized controlled trial is required to address the issues raised.

Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS) is a common cause of projectile vomiting in the neonatal period, occurring with an incidence of approximately 1 to 3 per 1000 live births.1 Without surgical intervention, outcome is poor. Following pyloromyotomy, survival approaches 100%. Pyloromyotomy for IHPS has been practiced by surgeons for over a century, and the most commonly used technique is that described by Ramstedt in 1912.2 Ramstedt's pyloromyotomy for IHPS is a well-established and safe procedure. The laparoscopic approach to this procedure was originally described over a decade ago.3,4 With technological advances and the general increase in popularity of laparoscopic surgery, this approach has come into vogue, and a number of centers around the world have reported their experiences. Advantages of the laparoscopic approach have been cited as improved cosmesis, shorter hospital stay, and more rapid postoperative recovery.5–9 Despite its apparent ease of operation and satisfactory results, there remain unanswered questions with regard to its safety, efficacy, and actual benefits.10–12

The aim of this study was to assess any differences in complication rates and outcome following surgery for IHPS between children treated using the open and laparoscopic techniques. We performed a systematic review of the existing evidence and a meta-analysis of the existing data.

METHODS

Searches were made in December 2002 of the MEDLINE electronic database (1966 to present date) and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, using the text words pyloromyotomy and laparoscopy. Only articles published in the English language were considered. The full texts of all studies of possible relevance were obtained, and the reference lists of these studies were checked for additional reports.

All studies reporting the treatment of IHPS by laparoscopic pyloromyotomy (LP) were considered. Studies reporting results following LP or open pyloromyotomy (OP) alone were excluded, and only studies directly comparing the 2 approaches were selected for further analysis. The subjects of this review were all infants with IHPS who underwent pyloromyotomy. The primary outcome measure was total number of complications during and following pyloromyotomy. These were defined by the reviewers as gastrointestinal perforation, serosal laceration, incomplete pyloromyotomy requiring repeat procedure, conversion from laparoscopic to open procedure, and wound infections. Other complications reported from the individual studies were also included. The secondary outcome measures analyzed were duration of surgery, time to full feeds, and postoperative length of stay.

Statistical Analysis

Original data were extracted from the studies and analyzed. Statistical analysis followed the guidelines of the Cochrane Neonatal Review Group for meta-analysis. For the purposes of meta-analysis, the standard deviation (SD) of continuous variables was required. This was reported by 3 studies.8,13,14 One study reported standard error of the mean (SEM)10 and SD was calculated from this. One study12 did not report any indicator of variance; this information was requested from the authors but was unavailable. The remaining studies reported indicators of variance but did not specify what that measure was. Given numerical consistency with values for SD from other studies in this review, they were assumed to be SD.

RevMan 4.1.1 (The Cochrane Collaboration) was used for data entry and compilation of the review. Statistical analysis was performed using Metaview 4.1 (Update Software, Oxford, England). Weighted treatment effects were calculated across studies using the fixed effects model. The results are expressed as weighted mean difference (WMD) for continuous variables and relative risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are also reported.

RESULTS

Eight published studies5,7–10,12–14 were identified in which LP and OP were directly compared. All patients (n = 595) from these 8 studies were included in the meta-analysis. Three hundred fifty-five infants who underwent OP were compared with 240 who underwent LP. There were no significant differences in demographic parameters between the infants treated with LP and those with OP in any of these studies. Only 1 of the studies available for inclusion was a randomized controlled trial.

Complications

All 8 studies reported complications during and following pyloromyotomy. One study specifically predefined the complications to be considered10; the remainder reported all complications that occurred. All complications reported are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Complications Reported During or Following Pyloromyotomy

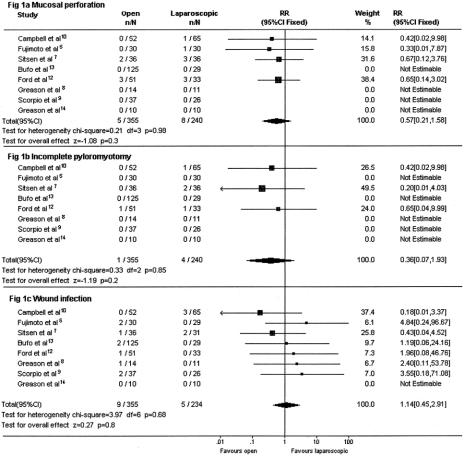

Mucosal perforations occurred less frequently in the OP group, although not significantly so (RR 0.57 [0.21, 1.58], P = 0.3). In 4 studies, there were no mucosal perforations in either group, and these studies cannot therefore be included in the RR calculation as the risk of perforation in each group is zero (Fig. 1a).

FIGURE 1. Forest plot comparing rates of mucosal perforation (A), incomplete pyloromyotomy (B) and wound infection (C) between infants treated with OP and LP. The blocks indicate the estimate of RR and their size relates to the size of the individual study. Blocks to the right of the line of no effect (RR >1.0) favor LP and those to the left of the line of no effect favor OP. The diamond indicates the overall estimate from the meta-analysis. χ2 Test for heterogeneity between studies and the significance of the overall effect are indicated.

Twelve (5%) laparoscopic procedures were converted to open procedures for completion. The reported indications for conversion included mucosal perforation, serosal laceration, inadequate view due to bowel distension, and insufficient experience of the operating surgeon. Three mucosal perforations during LP were not noticed during the original procedure. They later became clinically apparent and were corrected by an open procedure.

Incomplete pyloromyotomy requiring repeat operation (Fig. 1b) occurred in 3 studies and was less common in the OP group (RR 0.36 [0.07, 1.93], P = 0.2). In addition, 1 patient in a series reported by Greason et al8 required balloon dilatation of the pyloric channel following LP but was said to have a normal pylorus.

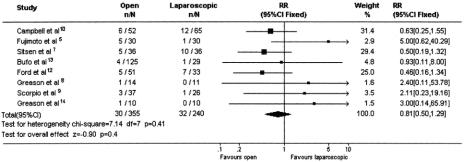

There was no significant difference in rates of wound infection between the groups (RR 1.14 [0.45, 2.91], Fig. 1c) nor in the incidence of all complications (RR 0.81 [0.5, 1.29], Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. Forest plot comparing total complication rates between infants treated with OP and LP. For explanation, see legend to Figure 1.

Duration of Surgery and Postoperative Recovery

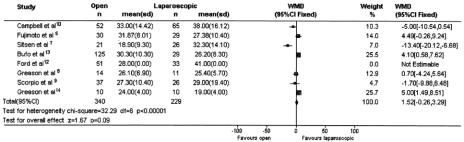

Duration of surgery was assessed in all 8 studies. It was defined as either time from incision to dressing10 or anesthetic time9 but was undefined in the remaining 6 studies. For the purpose of analysis we assumed that reported operating time represented the same time period in each study. Overall, there was no significant difference in operating time between the 2 groups, with the laparoscopic approach appearing slightly quicker (WMD = 1.52 minutes) than the open approach (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3. Forest plot comparing operation time for infants treated with OP and LP. The weighted mean difference (WMD) in minutes and 95% confidence interval between OP and LP was calculated. The blocks indicate the estimate of the WMD and their size relates to the size of the study. Blocks to the right of the line of no effect (WMD >0) favor LP and to the left of the line of no effect (WMD <0) favor OP. The diamond indicates the overall estimate from the meta-analysis. χ2 Test for heterogeneity between studies and the significance of the overall effect are indicated.

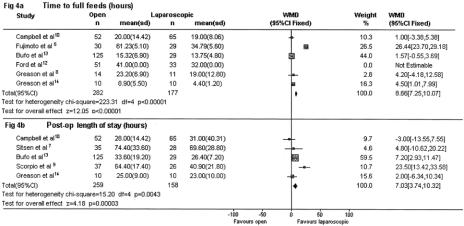

A measure of postoperative recovery was included in all studies. Both time to full feeds (Fig. 4a) and postoperative length of stay (Fig. 4b) were significantly shorter following LP.

FIGURE 4. Forest plot comparing time to full feeds (A) and postoperative length of stay (B) between infants treated with OP and LP. Times are in hours. For explanation, see legend to Figure 3.

DISCUSSION

Methodological Quality of Included Studies

We have performed a systematic review of open versus LP for the treatment of IHPS. Four studies were retrospective reviews of treatment of IHPS in a single center over a specified period of time8,10,12,13 and 3 studies were carried out prospectively.5,9,14 Only 1 study14 used formal randomization to assign patients to one treatment group or the other, although Fujimoto et al5 allocated infants alternately to LP or OP. Sitsen et al7 retrospectively studied 36 infants treated with LP and compared these with 36 nonrandomized infants who underwent OP during an extended time period. This meta-analysis is therefore a review of all existing evidence rather than of randomized controlled trials, and there are severe limitations of any conclusions drawn from these data due to the likelihood of treatment bias. We justify the completion of this review as it is our opinion that there is currently inadequate information on which to base a treatment decision.

Heterogeneity of Data

The considerable heterogeneity of some of the data in this meta-analysis warrants comment and explanation. The operating time and 2 measures of recovery time all exhibit significant heterogeneity, as indicated by the χ2 statistics in the figures. There are a number of possible explanations for this: (i) the studies were all from different centers; (ii) the procedures were performed by a number of different surgeons in each center; (iii) different centers may be at different points on the learning curve of LP; and (iv) reintroduction of feeds postoperatively was based on protocols that differed among centers and also in some cases between treatment groups in the same center. While the basic procedure of either LP or OP is in theory the same in the 2 groups, differences in individual practice or differences in practices between centers may influence the size of the treatment effect. Differences in feeding protocols are likely to strongly influence time to full feeds and therefore probably greatly increase the heterogeneity. The effect of different postoperative feeding protocols between treatment groups in individual studies on the time taken to achieve full feeds and the postoperative length of stay may be significant. The fact that only 1 study was a prospective randomized controlled trial introduces further bias due to nonrandomization of patients between treatment groups.

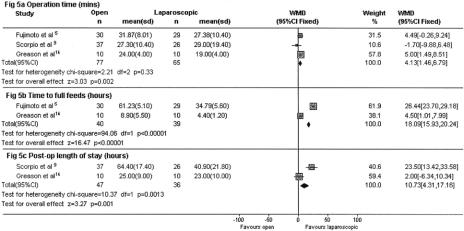

In an attempt to precisely identify the size of any treatment effect, we have performed subgroup analysis for these times using data only from the 3 prospective studies5,9,14 (Fig. 5). This shows a significantly shorter operating time with LP and greater differences in recovery times between the 2 groups.

FIGURE 5. Forest plot of subgroup analysis of prospective studies only comparing operation time (A), time to full feeds (B), and postoperative length of stay (C) between infants treated with OP and LP. For explanation, see legend to Figure 3.

Reviewers’ Conclusions

The data reviewed here support the use of both approaches to pyloromyotomy. OP appears to have a higher efficacy and lower complication rate than LP, but these differences are not statistically significant and may be related to the learning curve. We are unable to identify any clear benefit of LP over the open approach. This review brings to light the fact that there is a lack of good-quality evidence in this area. This is not unique to laparoscopic surgery but is the case in pediatric surgery as a whole, and the need for formalized prospective randomized controlled trials in pediatric surgery has recently been highlighted.15,16 Scorpio et al9 and Ford et al12 have all proposed that a randomized controlled trial be undertaken. With the exception of the small scale study by Greason et al,14 which did not address all outcome measures, this has yet to be performed.

Prospective randomized controlled trials comparing these 2 operative approaches should be conducted. In addition to studying efficacy and rates of complications, such trials should also examine the effect of surgical approach on secondary outcome measures such as time to full feeds, postoperative length of stay, postoperative analgesic requirements, long-term cosmesis of abdominal incisions, effect on growth and development, and financial costs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the assistance of Sima Pindoria with the statistical analysis and Simon Eaton for reviewing the manuscript. Research at the Institute of Child Health and Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust benefits from R & D funding received from the NHS Executive.

Footnotes

Reprints: Agostino Pierro, FRCS, Department of Paediatric Surgery, Institute of Child Health, 30 Guilford Street, London WC1N 1EH. E-mail: a.pierro@ich.ucl.ac.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.Grant GA, McAleer JJ. Incidence of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Lancet. 1984;1:1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramstedt C. Zur operation der angeborenen pylorus stenose. Med Klin. 1912;26:1191–1192. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alain JL, Grousseau D, Terrier G. Extramucosal pyloromyotomy by laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1991;5:174–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan HL, Najmaldin A. Laparoscopic pyloromyotomy for infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pediatr Surg Int. 1993;8:376–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujimoto T, Lane GJ, Segawa O, et al. Laparoscopic extramucosal pyloromyotomy versus open pyloromyotomy for infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: which is better? J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:370–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Downey EC Jr. Laparoscopic pyloromyotomy. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1998;7:220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sitsen E, Bax NM, van der Zee DC. Is laparoscopic pyloromyotomy superior to open surgery? Surg Endosc. 1998;12:813–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greason KL, Thompson WR, Downey EC, et al. Laparoscopic pyloromyotomy for infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: report of 11 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:1571–1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scorpio RJ, Tan HL, Hutson JM. Pyloromyotomy: comparison between laparoscopic and open surgical techniques. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1995;5:81–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell BT, McLean K, Barnhart DC, et al. A comparison of laparoscopic and open pyloromyotomy at a teaching hospital. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1068–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shankar KR, Losty PD, Jones MO, et al. Umbilical pyloromyotomy: an alternative to laparoscopy? Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2001;11:8–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford WD, Crameri JA, Holland AJ. The learning curve for laparoscopic pyloromyotomy. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:552–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bufo AJ, Merry C, Shah R, et al. Laparoscopic pyloromyotomy: a safer technique. Pediatr Surg Int. 1998;13:240–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greason KL, Allshouse MJ, Thompson WR, et al. A prospective, randomized evaluation of laparoscopic versus open pyloromyotomy in the treatment of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Pediatr Endosurg Innovat Techniques. 1997;1:175–179. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baraldini V, Spitz L, Pierro A. Evidence-based operations in paediatric surgery. Pediatr Surg Int. 1998;13:331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moss RL, Henry MC, Dimmitt RA, et al. The role of prospective randomized clinical trials in pediatric surgery: state of the art? J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1182–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]