Abstract

Objective:

The current study compares outcome after resection of papillary hilar cholangiocarcinoma to that of the more common nodular-sclerosing subtype.

Methods:

Clinical, radiologic, histopathologic, and survival data on all patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma were analyzed. Resected tumors were reexamined and classified as nodular-sclerosing (no component of papillary carcinoma) or papillary (any component of papillary carcinoma); for papillary tumors, the proportion of invasive carcinoma present was determined. Differences in the clinical behavior and histopathologic features of nodular-sclerosing and papillary tumors were assessed.

Results:

From January 1991 to November 2003, 279 patients were evaluated, 154 men (55.2%) and 125 women (44.8%), with a mean age of 65.4 ± 0.7 years (median = 68, range 23–87 years). Of the 215 patients explored, 106 (49.5%) underwent a complete gross resection. An en bloc partial hepatectomy (n = 87) and an R0 resection (n = 82) were independent predictors of favorable outcome. Operative mortality was 7.5% but was 2.8% over the last 4 years of the study, and there were no operative deaths in the last 33 consecutive resections. Twenty-five resected tumors (23.6%) contained a papillary component: 12 were minimally or noninvasive (<10% invasive cancer) and 13 had an invasive component ranging from 10% to 95% (≥10%). Patients with papillary and nodular-sclerosing tumors had similar demographics, operative procedures, and proportion of R0 resections. By contrast, papillary tumors were significantly larger, more often well-differentiated, and earlier stage. Disease-specific survival after resection of papillary tumors (55.7 months) was greater than after resection of nodular-sclerosing lesions (33.5 months, P = 0.013). The papillary phenotype was an independent predictor of survival, although the benefit was more pronounced for less invasive tumors.

Conclusions:

The presence of a component of papillary carcinoma is more common than previous reports have suggested and is an important determinant of survival after resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

Papillary tumor morphology is an important prognostic factor in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma and appears to be more common than prior reports have suggested. An aggressive resectional approach to papillary tumors is warranted, given the possibility of prolonged survival and the increasing safety with which such resections can be performed.

Although adenocarcinoma may arise anywhere in the biliary tree, the proximal extrahepatic bile ducts are the most common site (hilar cholangiocarcinoma).1–5 However, hilar cholangiocarcinoma is rare, accounting for a small fraction of all gastrointestinal cancers.6,7 From a therapeutic standpoint, it is now established that, although hilar tumors arise from the extrahepatic bile ducts, they are most effectively treated with en bloc hepatic resection.8–11 However, many aspects of this disease remain incompletely understood, including the pathogenesis and the clinical and histopathologic factors that influence survival.

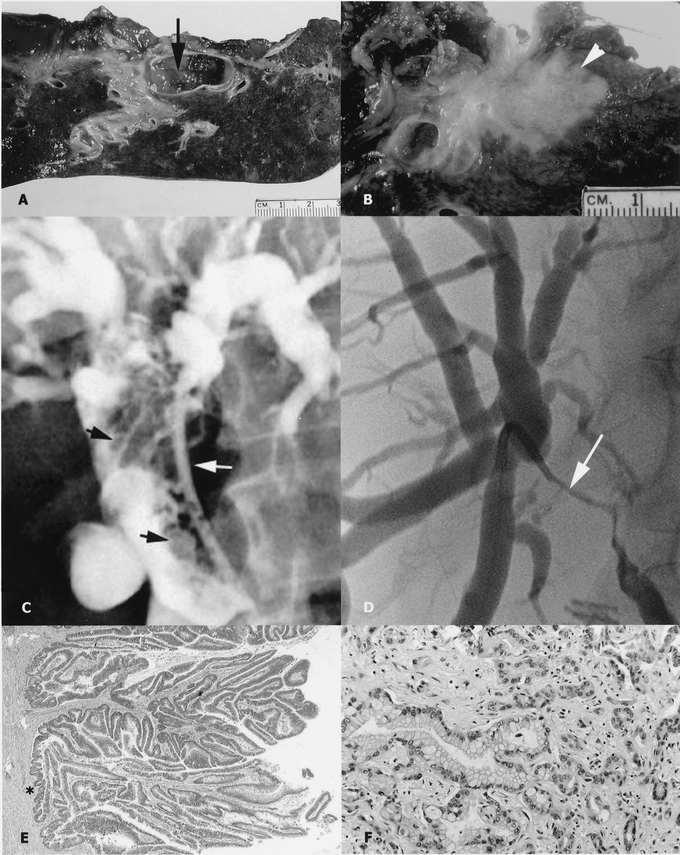

Papillary cholangiocarcinoma is well known but much less common than the more typical nodular-sclerosing morphology associated with hilar cholangiocarcinoma.12–15 Papillary tumors are soft, have a predominantly intraductal growth pattern that expands the duct, and in some cases may have little (if any) associated invasive carcinoma (Fig. 1). These features are in contradistinction to nodular-sclerosing lesions, which are firm, highly invasive, and tend to constrict the bile duct and periductal tissues. While a better prognosis for papillary cholangiocarcinoma has been suggested,13,14 meaningful experience with these tumors is limited since they account for a minority of all extrahepatic bile-duct cancers. The invasive carcinomas arising from papillary precursors are histologically similar to those unassociated with a papillary component, but it is not known whether they have the same biologic behavior. Furthermore, most reports are confounded by inclusion of a large proportion of patients with tumors arising from the distal bile duct.

FIGURE 1. Cholangiographic, gross, and microscopic appearance of a papillary cholangiocarcinoma (left, panels A, C, E) and a nodular-sclerosing tumor (right, panels B, D, F). Note the papillary tumor within the bile-duct lumen (panel A, arrow) and the nodular-sclerosing tumor invading the hepatic parenchyma (panel B, arrow). Transhepatic cholangiogram of a papillary tumor (panel C) showing multiple filling defects that expand the duct (black arrows; the biliary drainage catheter is indicated by the white arrow). This is in contrast to the cholangiographic features of nodular-sclerosing tumors characterized by an irregular stricture that constricts the duct lumen (panel D, arrow); a transhepatic catheter is seen traversing the stricture. Histologic section of a papillary cholangiocarcinoma with no invasive component (panel E, asterisk) and an invasive nodular-sclerosing tumor associated with a desmoplastic stroma (panel F).

The present study analyzes the clinical and histopathologic features associated with hilar cholangiocarcinoma in a group of consecutive patients treated at a single institution; prognostic factors associated with survival after resection are also assessed. The analyses seek to better characterize the clinical behavior of papillary cholangiocarcinoma and to highlight differences between papillary and nodular-sclerosing subtypes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Identification

All patients with a diagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma evaluated and treated at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) since 1991 were identified. A subset of these patients was the subject of a prior report;8 the current study represents not only an update of the authors’ experience but specifically targets patients with papillary tumors for analysis. Clinical, radiologic, histopathologic, and survival data were entered prospectively and then updated and analyzed retrospectively. Only patients with adenocarcinoma arising from the biliary confluence or the right or left main hepatic ducts were included. Patients with tumors originating in the proximal common hepatic duct were included if the tumor extended to the biliary confluence. Patients with diffuse or multifocal cholangiocarcinoma were included, provided that the right or left hepatic ducts or the biliary confluence was involved. Patients with papillary cholangiocarcinoma were included if the tumor arose from a base within the proximal bile ducts, as defined above. In patients with unresectable disease, biopsy confirmation of the diagnosis was performed in most cases, which was required before initiating any nonsurgical therapy; the small number of patients without biopsy-proven cancer was included only if the imaging studies supported the diagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma (hilar mass causing biliary dilatation), there was no evidence of a primary tumor elsewhere, and subsequent imaging showed evidence of disease progression.

Patient Evaluation

Initial assessment of all patients included a complete history and physical examination, assessment of general health, and review of available test results and imaging studies. Patients were usually referred after at least partial radiographic evaluation had been completed, which in most instances consisted of a computed tomographic scan (CT) and either endoscopic or percutaneous cholangiography. In many patients, biliary stents were placed as part of the cholangiographic procedure. After referral, further evaluation of biliary tumor extent and assessment of possible vascular involvement and/or metastatic disease were typically performed with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and duplex ultrasonography; CT angiography was used selectively to address specific concerns regarding arterial involvement. The preoperative imaging assessment of local tumor extent was used to categorize all patients into 1 of 3 clinical stage groupings, as previously described.8 Over the past several years, positron emission tomography (PET) has been used increasingly to identify occult metastatic disease, although the benefit of this additional test remains to be determined.16 Cases were reviewed at a multidisciplinary hepatobiliary disease management conference.

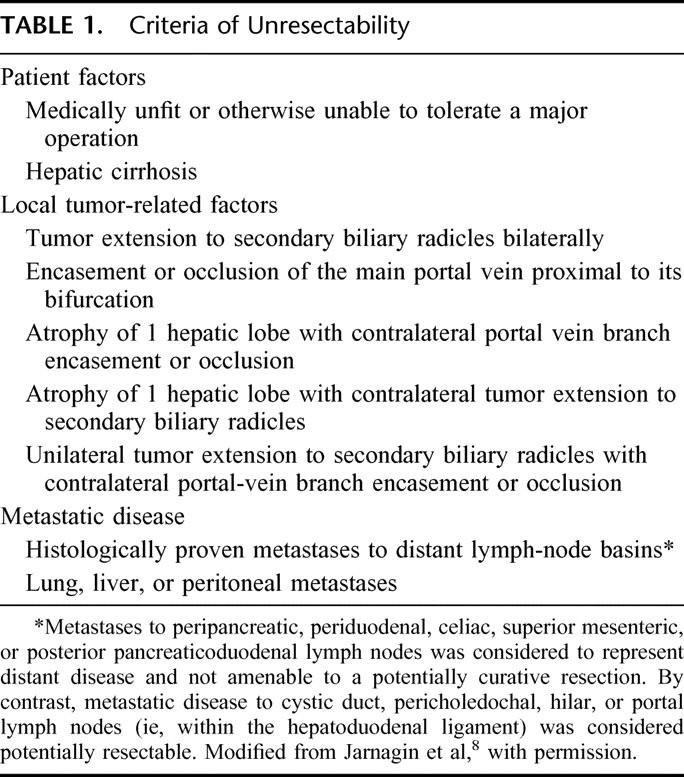

Patients with potentially resectable tumors (Table 1) underwent further evaluation with a screening chest radiograph, routine laboratory studies, assessment by an anesthesiologist, and formal cardiopulmonary testing if warranted. Complications related to biliary tract obstruction or previous biliary intervention (ie, cholangitis, pancreatitis, biliary injury), if present, were treated before operation. In some patients, this required replacing existing biliary catheters, placing new catheters to drain contaminated and obstructed areas of the biliary tree drain or extrahepatic collections, and/or a prolonged course of antibiotics. Routine biliary drainage of jaundiced patients, not previously stented and without cholangitis, was not performed provided that operation could be performed in a timely fashion (within approximately 1 week). Preoperative portal-vein embolization (in patients without lobar atrophy) was not used.

TABLE 1. Criteria of Unresectability

All biopsy material from referring institutions was examined by pathologists at MSKCC. In patients with advanced disease or in those not suitable for operation, biopsy confirmation of the diagnosis was performed, if not done previously, and plastic biliary drainage catheters were replaced with self-expandable metallic stents. However, when the imaging studies suggested a potentially resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma, histologic confirmation of malignancy was not pursued prior to operation.

Conduct of the Operation

In patients undergoing a potentially curative resection, a standardized operative approach was used, as previously described.1,8,17 Since 1997, staging laparoscopy has been used liberally but is now limited to patients with more locally advanced tumors or to assess findings suspicious for metastatic disease on cross-sectional imaging.18,19 Full exploration was performed to exclude metastatic disease. Exposure of the biliary confluence and assessment for vascular involvement was accomplished by early transection of the common bile duct at the level of the duodenum, with reflection superiorly. Intraoperative bile cultures were sent routinely. The entire extrahepatic biliary apparatus (supraduodenal bile duct and gallbladder), usually with en bloc partial hepatectomy, was performed and included a subhilar lymphadenectomy (clearance of all lymph nodes within the hepatoduodenal ligament to the level of the common hepatic artery). Caudate lobectomy was performed routinely for tumors involving the left hepatic duct and in any case when considered necessary to achieve complete tumor clearance. Histologic assessment of resection margins was performed intraoperatively. Additional tissue was resected, if feasible, when residual microscopic disease was suspected based on frozen-section histology. Resection and reconstruction of major vascular structures was performed when necessary to achieve tumor clearance for disease that was otherwise resectable. Roux-en-Y biliary-enteric reconstruction was performed to a segment of jejunum approximately 70 cm in length.

Patients with unresectable tumors were often referred for systemic chemotherapy or chemoradiation therapy, as appropriate based on disease extent. However, adjuvant therapy was not used routinely in patients submitted to a complete resection.

Data Analysis

Patient demographics, findings of radiographic investigations, and final patient disposition were recorded. In patients submitted to operation, the surgical findings, operation performed, estimated blood loss (as recorded by the anesthesiologist), hospital stay (from the time of operation to discharge) and postoperative complications were recorded. Postoperative complications were graded on a scale of 0 (no complication) to 5 (perioperative mortality), as defined previously;20 operative mortality was defined as any death resulting from a complication of the operation, whenever it occurred. Transfusion of any blood products (packed red cells, whole blood, fresh frozen plasma, or platelets) during the operation or at any time during the index hospital admission was also recorded. Data regarding the resected specimen, including tumor size and differentiation, status of the resection margin (negative [R0] or positive [R1]), metastatic disease to resected lymph nodes, and tumor stage according to the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC; 6th edition)21 were analyzed. Any evidence of microscopic tumor at the biliary, hepatic or soft-tissue resection margin constituted an R1 resection. Tumor differentiation (well, moderate, or poor) was determined on histologic review of the resected specimen. In the current study, invasive cancers classified as well- to moderately differentiated or well-differentiated with areas of moderate differentiation were included with the moderately differentiated lesions.

All resected tumors were reexamined by a pathologist (D.K.) unaware of the clinical follow-up of each case. All tumors were extensively sampled and classified as either papillary or nodular-sclerosing based on review of the hematoxylin and eosin stained sections. Nodular-sclerosing tumors were characterized by well- to poorly differentiated glandular elements invading into or through the bile duct wall and accompanied by a desmoplastic stroma (Fig. 1). Neoplastic papillary projections were not found in the bile ducts of the nodular-sclerosing carcinomas. Papillary cholangiocarcinomas were characterized, at least focally, by exophytic proliferation of neoplastic papillary epithelium within the lumen of the bile ducts, with an invasive component (if present) that typically consisted of infiltrative glandular structures extending into or through the bile duct wall. It should be emphasized that benign biliary neoplasms (ie, adenomas, papillomatosis) were not included. Papillary tumors were carefully scrutinized for evidence of invasive cancer, the proportion of which was calculated in relation to the papillary component. Subsequent analyses compared minimally and noninvasive papillary cholangiocarcinomas (<10%, invasive component) to more invasive papillary tumors (≥10% invasive component).

Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS, version 11.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Chicago, IL). Continuous variables were compared using Student t test (2-tailed) and categorical variables with a χ2 test. Survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method22 and compared by log-rank test. Survival (in months) was measured from the date initially seen at MSKCC to the date of death or date of last contact. Differences in clinical and pathologic variables associated with nodular-sclerosing and papillary tumors were analyzed. Cox regression23 was used to determine independent predictors of outcome, using survival as the dependent variable and factors significant (P = 0.05) on univariate analysis as covariates; perioperative deaths were not included in the survival analyses. P values <0.05 were considered to be significant. Numeric data are presented as median values and/or mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

This study was approved by the institutional review board at MSKCC.

RESULTS

Demographics and Results of Initial Evaluation

From January 1991 to November 2003, 279 patients were seen and evaluated, 154 men (55.2%) and 125 women (44.8%), with a mean age of 65.4 ± 0.7 years (median = 68, range 23–87 years). Two hundred one patients were subjected to 1 or more biliary drainage procedures prior to referral. Imaging studies revealed evidence of portal-vein involvement in 151 patients (54.1%) and lobar atrophy in 120 patients (43%); 103 patients (36.9%) had both. The majority of patients had clinical stage 1 (n = 107, 38.4%) or stage 2 (n = 112, 40.1%) tumors, while the remainder (n = 56, 20.1%) had more locally advanced clinical stage 3 lesions.

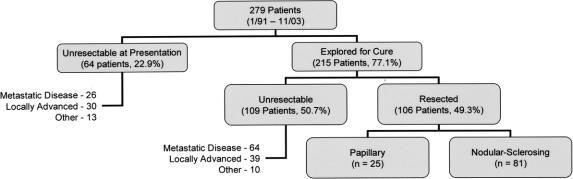

Operative Findings, Operative Procedures, Perioperative Results

Sixty-four patients (22.9%) were not amenable to resection at the time of presentation; 21 had metastatic disease, 25 had locally advanced tumors, 5 had both, and 13 were either medically unfit or refused surgery (Fig. 2). Two hundred fifteen patients (77.1%) were explored for a potentially curative resection, of which 106 (49.5%) underwent a complete gross resection. One hundred nine patients (50.5%) had unresectable disease discovered at exploration, the majority due to metastatic disease.

FIGURE 2. Findings and final disposition in all patients. In patients who were not candidates for resection at presentation, 26 had metastatic disease, 30 had locally advanced tumors, and 5 had both. “Other” refers to 11 medically unfit patients and 2 patients who refused operation. Unresectability at operation was due to metastatic disease in 60 patients or locally advanced disease in 35 (4 patients had both of these findings). “Other” refers to 10 patients in whom the extent of the resection was considered too great because of underlying medical comorbidities or the unexpected finding of hepatic parenchymal disease.

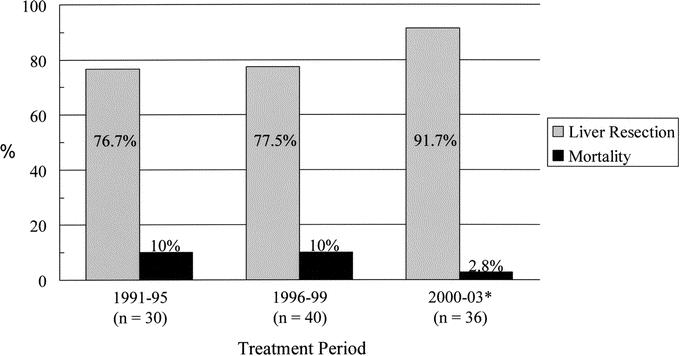

Resectional procedures consisted of excision of the extrahepatic bilary tree and subhilar lymphadenectomy in all patients, and this was combined with an en bloc partial hepatectomy in 87 patients (82.1%). The hepatic resections performed were as follows: extended right hepatectomy (n = 42), right hepatectomy (n = 7), extended left hepatectomy (n = 6), left hepatectomy (n = 28), central hepatectomy (n = 4); en bloc caudate resection was performed in 36 of these patients (41.4%), 11 underwent a formal vascular resection and reconstruction (portal vein in 10, vena cava in 1) and 2 underwent a concomitant pancreaticoduodenectomy. Over the study period, there was a progressive increase in the proportion of patients submitted to hepatic resection, from 76.7% in the first third of patients treated (1991–1995) to 91.7% in the most recent third (2000–2003) (Fig. 3). All patients submitted to resection were clinical stage 1 (n = 64) or 2 (n = 42).8

FIGURE 3. Trends in the proportion of en bloc hepatic resections performed and operative mortality over the study period. Patients were divided into 3 groups based on date of treatment. Treatment period 1 (n = 30) extended from 1991 to 1995, treatment period 2 (n = 40) from 1996 to 1999, and treatment period 3 (n = 36) from 2000 to 2003 (* to November). Operative mortality was 0% for the last 33 consecutive resections.

Seventy-four patients (69.8%) had 1 or more biliary stents in place at the time of resection. The mean preoperative serum bilirubin level was 5.2 ± 0.7 mg/dL (median = 1.8 mg/dL, range = 0.2–35.7). The mean operative blood loss was 924.2 ± 84.4 mL (median = 800 mL, range = 130–7000), and 56 patients (52.8%) required perioperative transfusion of blood products; 13 received fresh frozen plasma (FFP) only, while the remainder received red blood cell products with or without FFP. Sixty-six patients (62.3%) experienced 1 or more postoperative complications, the most common of which were perihepatic abscesses (n = 32), bile leaks (n = 7), or sterile fluid collections (n = 2) requiring drainage. Major complications (grade 3 or higher, including perioperative deaths) occurred in 47 patients (44.3%). Mean hospital length of stay was 15.3 ± 0.8 days from the date of resection. The overall operative mortality was 7.5% (n = 8) but was notably lower (2.9%) in the most recent treatment group (Fig. 3), and there were no operative deaths in the last 33 consecutive resections.

Histopathology of Resected Tumors

All resected specimens were confirmed as adenocarcinomas. An R0 resection was achieved in 82 patients (77.4%), and this was significantly more likely in patients submitted to a concomitant hepatic resection compared with a bile duct resection alone (83.4% versus 47.4%%, P = 0.001). Twenty-two tumors (20.8%) were associated with regional nodal metastases, and 35 (33%) invasive lesions were well differentiated. Tumor invasion beyond the bile duct wall (AJCC T-stage ≥2) was documented in 93 cases (86.7%), of which 60 (56.6%) invaded into the liver parenchyma or adjacent major vascular structures (AJCC T-stage ≥3). The majority of tumors were AJCC stage 1B (n = 27), 2A (n = 40), or 2B (n = 22); the remainder were stage 0 (carcinoma in situ, n = 6), stage 1A (n = 7), stage 3 (n = 3), or stage 4 (n = 1). There was a close association between tumor differentiation and stage; 23 tumors classified as well-differentiated (65.7%) were early stage (<2A), compared with only 12 (23.5%) moderate or poorly differentiated tumors (P = 0.0001).

Twenty-five tumors were confirmed histologically to have a papillary component. Nineteen of these tumors had an associated invasive component that ranged from 1% to 95%, while 6 had no evidence of invasive cancer (intraductal papillary carcinoma, T-stage pTis). Twelve papillary tumors had <10% invasive carcinoma component, despite a mean size of 3.9 ± 0.6 cm (compared with 2.6 ± 0.2 cm for nodular sclerosing tumors, P = 0.009). Of note, only 2 of the 173 unresectable tumors were radiographically consistent with papillary tumors.

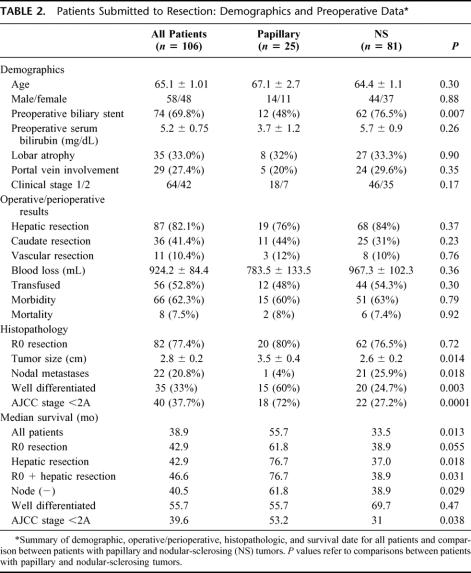

Comparison of Papillary and Nodular-Sclerosing Tumors

Differences in several clinical and histopathologic variables between patients with nodular-sclerosing and papillary tumors are summarized in Table 2. Of the demographic variables analyzed, preoperative biliary stents were less common in patients with papillary tumors (48%) compared with those with nodular-sclerosing lesions (76.5%, P = 0.007); this may be related to the somewhat lower preoperative serum bilirubin level in the former group. There were no differences between the groups with respect to operative procedures and perioperative outcome, including the proportion of en bloc hepatic resections, caudate resections, and vascular resections/reconstructions performed, operative blood loss and the proportion of patients transfused, and morbidity and mortality. Likewise, the proportion of R0 resections was also similar between the 2 groups. By contrast, papillary tumors were significantly larger, less often associated with regional nodal metastases, more often well-differentiated and earlier stage lesions.

TABLE 2. Patients Submitted to Resection: Demographics and Preoperative Data

Disease-Specific Survival

The median follow-up time for all patients was 13.9 months and was 30.4 months in patients who underwent resection (excluding perioperative deaths). Patients with unresectable disease had a median survival of 10.5 months, compared with 38.9 months in those submitted to resection (P = 0.001). Among all resected patients, the status of the resection margin (R0 = 42.9 months, R1= 24 months, P = 0.0003) and a concomitant partial hepatectomy (hepatic resection = 42.9 months, no hepatic resection = 28.8 months, P = 0.021) were potent predictors of outcome. Disease-specific survival after an R0 resection was greater if a concomitant partial hepatectomy was performed (46.6 versus 31.0 months), although this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.065). After an R0 resection with concomitant partial hepatectomy, neither an en bloc caudate lobectomy nor a vascular resection/reconstruction was associated with improved survival compared with similar resections that did not include these procedures (46.6 months with caudate resection versus 47.1 month without caudate resection, P = 0.98; 46.3 months with vascular resection versus 46.6 months without vascular resection, P = 0.97).

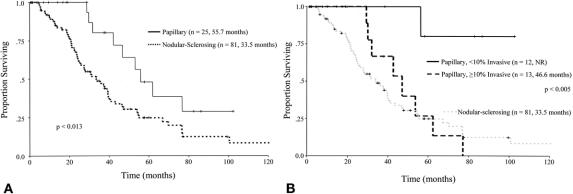

Disease-specific survival after resection of papillary tumors (55.7 months) was significantly better than after resection of nodular-sclerosing lesions (33.5 months, P = 0.013) (Fig. 4A). Among patients who had an R0 resection, an en bloc partial hepatectomy, or both, a persistent survival advantage was seen in the papillary group; this was also true when the analysis was restricted to patients with node (−) and earlier AJCC stage tumors (<2A) but not well-differentiated lesions (Table 2). Furthermore, when patients with noninvasive papillary tumors were excluded (n = 6), papillary morphology was still associated with improved survival compared with nodular-sclerosing tumors (53.2 months versus 33.5 months, P = 0.026).

FIGURE 4. A, Survival after resection of all tumors, nodular-sclerosing (broken line) versus papillary tumors (solid line). B, Survival after resection of papillary tumors, <10% invasive component (solid line; NR indicates not reached) versus ≥10% invasive component (broken black line). Survival of patients with nodular-sclerosing tumors is shown in the light-gray dashed line for comparison.

For papillary tumors, the proportion of invasive carcinoma was an important determinant of survival (Fig. 4B); tumors with <10% invasive component were associated with a median survival that was not reached, compared with 46.6 months for tumors with ≥10% invasion (P = 0.005). Papillary cholangiocarcinoma patients with more invasive lesions (≥10% invasive cancer) had a median disease-specific survival that was greater than that seen after resection of nodular-sclerosing tumors (46.6 versus 33.5 months), although this difference was not significant (P = 0.57).

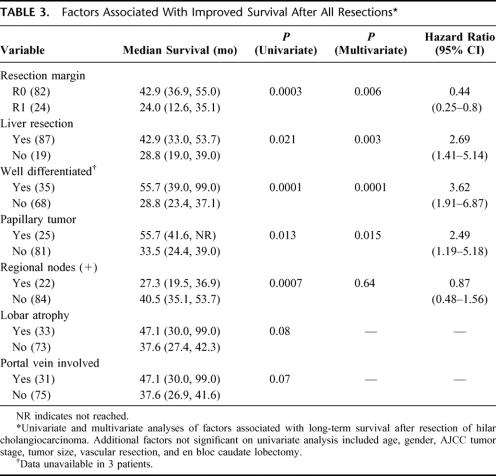

An analysis of factors associated with survival is detailed in Table 3. Of the variables analyzed, an R0 resection, an en bloc partial hepatectomy, well-differentiated histology, and papillary components emerged as independent predictors of survival. The presence of metastatic disease to lymph nodes in the hepatoduodenal ligament was not significant in the multivariate analysis. Lobar atrophy and portal-vein involvement approached significance on univariate analysis because of their close association with a concomitant hepatic resection but were not included in the multivariate model. Variables that were not significant on univariate analysis included age, gender, AJCC tumor stage, tumor size, vascular resection, and en bloc caudate lobectomy.

TABLE 3. Factors Associated With Improved Survival After All Resections

To date, there have been 16 actual 5-year survivors of 68 patients at risk (23.5%, including 7 postoperative deaths). All of these long-term survivors underwent a concomitant partial hepatectomy, 15 (93.8%) had an R0 resection (1 patient with an R1 resection developed recurrence at 47 months), 9 (56.3%) had well-differentiated carcinomas, 5 (31.3%) had papillary tumors, and 3 (18.8%) had regional nodal metastases. Six patients remain cancer free, 1 is alive with recurrence, and 9 have died of disease.

DISCUSSION

Hilar cholangiocarcinoma remains a difficult clinical problem. Prolonged survival is possible only after a complete resection, which should include an en bloc partial hepatectomy in nearly every case. The results of this and other recent studies have documented the importance of hepatic resection in treating hilar cholangiocarcinoma and the increasing safety of such procedures, which can now be performed with an operative mortality much lower than was previously possible.10,24 Even so, because hilar cholangiocarcinoma is a rare disease, this improvement in perioperative outcome has lagged behind similar improvements in hepatic resectional surgery for other diseases, such as metastatic colorectal cancer.25,26 Increasingly, however, as centers gain experience treating hilar cholangiocarcinoma, factors associated with outcome are coming into sharper focus.

The present study highlights the importance of the papillary cholangiocarcinoma histology as an outcome determinant after complete resection. Despite differences in disease stage, the survival advantage of papillary tumors was apparent even when compared with node (−) and less invasive nodular-sclerosing lesions and also when noninvasive papillary lesions were excluded. In addition, the invasive component of papillary carcinomas was generally better differentiated than nodular-sclerosing tumors. As suggested in prior reports,10,27,28 prognosis after resection in the current study was strongly influenced by well-differentiated tumor histology, which correlated closely with earlier disease stage and presence of a papillary component. Indeed, when compared with papillary tumors, well-differentiated nodular-sclerosing tumors had a similar outcome. Nevertheless, both well-differentiated histology and papillary morphology emerged as independent predictors of survival.

The difference in outcome between papillary and nodular-sclerosing cholangiocarcinoma appears to be related, at least in part, to differences in disease biology. However, the data show that the favorable impact of papillary histology on survival is most pronounced in patients with less invasive cancers, suggesting that once a certain critical degree of invasiveness is reached, the clinical behavior of papillary cholangiocarcinoma approaches that of nodular-sclerosing tumors. This contrasts somewhat with a recent report from Hoang et al that summarized results from the SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results) database of the National Cancer Institute and showed a survival advantage of papillary cholangiocarcinoma even in patients with more invasive tumors and tumors associated with regional lymph node metastases.13

Whether more invasive cholangiocarcinomas of papillary origin are distinct from nodular-sclerosing cancers is thus less clear but perhaps can be clarified through a better understanding cholangiocarcinoma pathogenesis. The molecular events associated with the development of cholangiocarcinoma have been investigated but are incompletely understood.29 Likewise, the changes that distinguish papillary from nodular-sclerosing lesions are unclear.14,30 Abraham et al,30 in an analysis of 14 cases of papillary bile duct carcinomas, failed to identify any unifying molecular derangements, although the study population was heterogeneous and there was no direct comparison to nodular-sclerosing tumors. Despite gaps in our understanding of these tumors, it is reasonable to postulate differences in the genetic changes between invasive papillary tumors and purely nodular-sclerosing lesions. The finding of highly invasive tumors with some residual papillary carcinoma components would suggest the possibility of overlap between 2 distinct pathogenetic mechanisms. Alternatively, this finding may represent the slow evolution of noninvasive papillary carcinomas to more invasive and aggressive tumors, an explanation that is possible but would require a long symptom-free period.

The results of previous studies would suggest that papillary tumors account for approximately 4% to 5% of all malignant epithelial tumors of the extrahepatic biliary tree,13,14 which is lower than that seen in the present report. One possible explanation for this difference is that papillary tumor histology is more common in the proximal biliary tree. Alternatively, and perhaps more likely, minor elements of papillary carcinoma among highly invasive tumors may be more common than appreciated previously.

The marked reduction in perioperative mortality over the past several years represents an important finding of the current study. It must be emphasized that this trend is not the result of any specific change in clinical practice, such as preoperative portal vein embolization or aggressive percutaneous biliary drainage, as advocated by some,9,10,24,31,32 but is rather a manifestation of the general overall improvement in perioperative results seen over the past decade.26 The results of the current study also support a policy of selective application of both caudate- and portal-vein resection when necessary to achieve tumor clearance.

In summary, papillary tumor morphology is an important prognostic factor in patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma, especially when this component predominates, and appears to be more common than prior reports have suggested. An aggressive resectional approach to papillary tumors is warranted, given the possibility of prolonged survival and the increasing safety of such procedures.

Discussions

Dr. William Chapman (St. Louis, Missouri): This report comes from one of the premiere surgical groups internationally and once again provides important data analyzing variables of outcome for what has previously been viewed as a dismal prognosis.

In the current report, Drs. Jarnagin, Blumgart, and colleagues investigate their experience over a 12-year period, during which time they treated 279 patients with a diagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Two hundred fifteen of these patients, or 49%, were able to undergo complete surgical resection, with approximately 80% undergoing a concomitant bile duct and hepatic resection. There are many variables which are presented in this well-written manuscript, but I would like to focus on just a couple of points and questions for the authors.

The first issue, which is the subject of the current paper, involved the 25 patients who were found to have papillary-type cholangiocarcinoma in distinction to the usual nodular sclerosing morphology. This represented a high 24% of patients in the current review, significantly greater than the approximately 5% that had previously been thought to be represented by this particular subtype. In addition, the authors found that this particular subgroup had significantly more favorable long-term survival with actuarial 5-year survival of approximately 35% in comparison to patients with the more typical nodular sclerosing morphology, where their 5-year survival was only approximately only 20%, decreasing to the 25 to 10% at 10 years, essentially suggesting that there were few long-term survivors for this more common diagnosis, even with the margin-negative resection.

I have 3 questions. Based on the information presented today, have you been able to go back and can you predict which patients prospectively may have the more favorable papillary type cholangiocarcinoma? In other words, are there imaging features or techniques which may suggest the presence of this tumor type and which in those patients a very aggressive approach for resection might be considered?

Second, of the 215 patients who were screened and selected for operative therapy, slightly over a half, or 109, were unable to undergo surgical resection. Some of the patients had metastatic disease that was not discovered until the time of exploration. However, almost 20% of the patients had what was classified as “locally advanced disease” that was not discovered until exploration. Could you clarify what factors were identified in the operating room that were not apparent based on what has become very sophisticated preoperative imaging? Was this based on operative ultrasonography or some other factor? And is there a way to reduce the rate of nontherapeutic laparotomy in these patients?

Finally, my third question. Could you comment on the potential role of liver transplantation in patients with cholangiocarcinoma? As you may be aware, early experiences with transplantation in this disease type were not favorable. However, there have now been several prospective trials reported in highly selected patients using neoadjuvant chemoradiation in which long-term survival rates are between 50% and 70%. These data have resulted in recently recommended guidelines from UNOS to provide potential priority listing for patients with locally advanced cholangiocarcinoma, as long as patients have been entered in a carefully controlled neoadjuvant protocol. Have you considered this for any of your patients, including those who you felt had locally advanced but nonmetastatic disease? While there is some appropriate skepticism regarding this approach, I would point out that a similar view was expressed only a few years ago for transplantation for HCC, and this has now been shown to be a very effective and standard therapy for carefully selected patients.

Dr. Steven C. Stain (Nashville, Tennessee): Over a 13-year period, the authors treated 279 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinomas. Of the 215 patients explored, 106 had a complete resection, including an en bloc partial hepatectomy in 82% and a clear histologic margin in 77%. Even when performed by the expert surgeons, these are difficult procedures. Despite no deaths in the last 33 consecutive resections, the mortality for the entire series was 7.5%, and the 62% of the patients had complications.

The series of 106 resected patients presented today overlaps with the authors’ 2001 article published in Annals of Surgery, but this analysis focuses on comparing 81 patients with nodular sclerosing histology to 25 patients with papillary tumors. All resected specimens were retrospectively reviewed by a pathologist blinded to the clinical outcome and staged using 6th-edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. After multivariate analyses, only 4 factors were statistically associated with long-term survival: resection margin, partial hepatectomy, presence of a well-differentiated or papillary tumor.

In nearly every method compared, clear resection margins, partial hepatectomy, clear margins with hepatic resections, node negatives, and earlier-stage tumors, patients with papillary tumors had longer survival than those with nodular sclerosing tumors. Many authors, including the senior author more than 20 years ago, have suggested the favorable prognosis of papillary tumors.

I have 3 questions for the authors. First, the primary premise of the manuscript is that patients with papillary tumors have better prognosis than nodular sclerosing tumors. I believe this can largely be explained by the facts that nearly a quarter of the papillary tumors were carcinoma in situ, only 1 of the 24 patients had spread to regional lymph nodes, and thus, these patients were more likely to have lower-stage tumor. Is much of the favorable survival due to the inclusion of the patients with papillary carcinoma in situ? What is the median survival of the patients with papillary tumors, if you exclude the carcinoma in situ patients?

Second, to date, there have been only 16 actual 5-year survivors of the 68 patients at risk. All had a hepatic resection, and 15 of the 16 had a tumor-free margin. It is significant that there are only 6 cancer-free survivors with more than 5 years’ follow-up. Patients still die of their disease after 5 years. The authors have not advocated adjuvant therapy after resection. In light of the fact so few patients are actually cured after resection, would the authors consider prospectively studying the efficacy of alternate therapies, either chemotherapy, radiation, or even transplantation in these patients?

And lastly, 11 patients had formal resection of either the portal vein (10) or vena cava (1). Did any of the actual 5-year survivors have vascular resections? If not, would the authors consider the subgroup of patients incurable, although not necessarily irresectable?

Dr. Henry A. Pitt (Indianapolis, Indiana): Many manuscripts in the literature suggest that papillary biliary tumors have a better prognosis, but most are not adequately powered to prove that trend. This report clearly is adequately powered.

For those of us who work in the pancreas, many similarities exist between what we are now seeing with the intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, the IPMNs of the pancreas, at least histologically and to some extent clinically with these papillary lesions in the biliary tree. Would the authors conjecture about the similarities and differences?

Similarly, some overlap may exist between the biliary cystadenomas and the papillary lesions in the biliary tree. Would the authors also comment on how they differentiate those patients.

Finally, in the pancreas the pathologists have done a good job in the last couple of years in differentiating patients with benign, borderline (or dysplasia), carcinoma in situ, and invasive tumors, which correlate with prognosis. My question, therefore, is how generalizable is your 10% invasive category? Is this categorization only useful for your pathologists, or should we classify papillary biliary tumors in a very similar way with benign, borderline, in situ, and invasive tumors?

Dr. Alan W. Hemming (Gainesville, Florida): Dr. Blumgart, you resected approximately 50% of patients operated on, which was lower than the series that we just presented. Do you think that your reduced mortality in the last few years is because you are better than us at selecting patients to back out on? I guess another way to ask it is: What do you think would be a realistic trade-off between being aggressive in resecting patients versus increasing our operative mortality? Should we all be aiming at zero percent operative mortality? Or does that mean that if we aim for zero percent and back out, we are denying some patients that are curable their chance at cure?

Dr. Reid B. Adams (Charlottesville, Virginia): I am going to potentially stir a little controversy for a minute and ask a question about extended resection. With the supposition that we all agree that R-0 resections are critical for cure, a second supposition is that you can adequately preoperatively detect a papillary versus a nodular sclerosing tumor.

With those 2 suppositions and considering the better prognosis and the amount of invasion in the papillary lesions, do you think that you can get away with a smaller extent of resection for those tumors that are truly at the confluence of the right and left duct; in other words, those that have been classified as 1 or 2 tumors without extension out the right or the left side?

I ask this in light of your results and the decreased submucosal spread seen with these papillary tumors.

Dr. Bryan M. Clary (Durham, North Carolina): A very nice series, Dr. Blumgart and Dr. Jarnagin. I would be a little bit more cautious about describing the current mortality rate as profoundly different from the earlier years and your experience. The numbers are very small, and 1 or 2 untoward events can obviously change the numbers significantly.

I noticed in your data that the preoperative bilirubins I believe on average were roughly 4 or so. So in terms of preoperative portal-vein embolization and drainage, I was wondering if you looked through your data and noted whether the mortalities that you have experienced are in those patients who have markedly elevated bilirubins. You know, a number of these patients present with bilirubins of 10, 15, and even higher. And I was wondering if there was any correlation now with your mortality rates from that.

Dr. William Jarnagin (New York, New York): Thank you very much. First, 3 questions from Dr. Chapman.

Can you predict papillary phenotype preoperatively? As you saw in the cholangiogram, these tumors often have quite a distinctive cholangiographic and cross-sectional imaging appearance, expanding the duct rather than constricting it. So yes, in many cases you can. However, the 25 cases we are reporting were identified as the result of a very detailed pathologic examination looking for features of papillary phenotype. In the patients with unresectable disease, we clearly did not biopsy the tumors sufficiently for the pathologist to determine whether it was papillary or not. Also, for the patients who had more invasive papillary phenotypes, one might not be able to predict this preoperatively.

In terms of nontherapeutic laparotomy, what were the findings? Metastatic disease was not uncommon, but by and large we remain only fair at best in assessing unresectable, locally advanced tumors laparoscopically. We continue to use laparoscopy liberally, although not in every case, and we have increasingly been using PET scans. I think there is a role for both. However, nontherapeutic laparotomies continue to be a problem because locally advanced disease is often difficult to determine, even at initial assessment at laparotomy. We can obviously tell beforehand which patients have encased vessels that will never be resectable, but many patients have extensive involvement of the portal vein or hepatic artery, which is not infrequently difficult to determine until you actually get there and assess it.

Liver transplantation, as you mentioned, has had a dismal outcome, and I think it needs to be studied very carefully before it can be advocated. The data from the Mayo Clinic are quite compelling, but let us point out that a very significant proportion of patients drop out with advancing disease. The patients who come to transplantation may simply reflect better disease biology. I think transplantation is reasonable to consider for very highly selected patients as part of a clinical trial.

Dr. Stain asked about carcinoma in situ. Six of the papillary patients in this series had minimal to no invasion seen. However, one of the slides that was passed over during the presentation compared outcome stratified by a number of different variables. When one only examines patients with lower stage tumors, the papillary patients still had a significantly greater survival. Also, when one excludes the 6 patients with minimal or no invasive component, there was still a better survival in the papillary group.

Regarding cancer recurrence after 5 years, this was unfortunately common. Five-year survival with cholangiocarcinoma does not equate to cure. Over half of the actual 5-year survivors in our series eventually developed recurrent disease. I think a proper prospective study of adjuvant therapy is desperately needed in this field.

Regarding vascular resection in incurrable patients, it is indeed true that only 1 of the actual 5-year survivors in this group underwent a vascular resection and reconstruction. It would seem reasonable to conclude that patients requiring vascular resection have disease that is more advanced than those who do not. It should be pointed out that, in the present series, the patients who underwent vascular resections were the ones who actually needed them. This is different from the philosophy of some groups who advocate routine vascular resections for most patients, even when the resection could be done without it. If one looks at the survival in our group of patients who underwent a liver resection with a negative margin, whether they had a vascular resection or not had no influence on survival. I, therefore, believe that vascular resection only in patients who require them is a reasonable policy.

Dr. Pitt asked about papillary bile duct cancers and their correlate in the pancreas: the intraductal papillary mucinous tumors. It is a very interesting question and not unreasonable to consider that these tumors might have a similar pathogenesis. Clearly, they have gross and histopathologic features in common. A recent study by Dr. Abraham at Johns Hopkins reported a very nice analysis of intraductal biliary tumors and found that they were quite different genetically than papillary type tumors arising from the pancreas. In fact, they were more similar to intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. I think it would also be reasonable to consider pancreatic tumors in a similar way of minimal to no invasion versus more invasive tumors.

Dr. Hemming asked about the better outcome in the more recent patients in this series. This is a difficult question to discuss in such an abbreviated time, but I think it overall reflects a general improvement in outcome after major hepatic resection not only in our experience but as reported by others, as well. It should be emphasized that patients in this series were not treated with portal-vein embolization or extensive preoperative biliary drainage as a matter of routine. I think it remains a point of some debate about how much these additional procedures add; they may benefit selected patients, but I do not believe that they represent the last word on reducing morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, I do not think the improved recent results have been the result of less extensive resections, since there has been a progressive increase in the proportion of hepatic resections. In addition, although not shown, there has been a progressive increase in the proportion of caudate resections as well. I do not know what the answer is, but I suspect that the better outcome has been part of the general trend towards better results overall for all hepatic resections over the past several years.

Dr. Clary asked about the improvement in mortality and recommended being cautious with our results. Of course, we are cautious. However, the trend is clear, and it is not unreasonable to talk about improvement in perioperative outcome based on the data presented.

Finally, Dr. Adams asked about smaller resections for papillary tumors. I think the lesson for these tumors is the same as that for the nodular sclerosing tumors: an R0 resection must be obtained in order to achieve a favorable outcome. In the present series, when one looks at the papillary group that underwent a biliary resection alone, the survival was not as good as those who underwent a concomitant hepatic resection. Therefore, I think we need to be careful before we start backing off from the extent of resection.

Footnotes

Present address of Jonathan Koea: Department of Surgery, Auckland Hospital, Auckland, New Zealand.

Reprints: William R. Jarnagin, MD, Department of Surgery, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021. E-mail: jarnagiw@mskcc.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burke EC, Jarnagin WR, Hochwald SN, et al. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system. Ann Surg. 1998;228:385–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagorney DM, Donohue JH, Farnell MB, et al. Outcomes after curative resections of cholangiocarcinoma. Arch Surg. 1993;128:871–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: a spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg. 1996;224:463–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tompkins RK, Thomas D, Wile A, et al. Prognostic factors in bile duct carcinoma: analysis of 96 cases. Ann Surg. 1981;194:447–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Launois B, Reding R, Lebeau G, et al. Surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: French experience in a collective survey of 552 extrahepatic bile duct cancers. J HBP Surg. 2000;7:128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parker SL. Cancer statistics 1996. CA Cancer J Clin. 1996;46:5–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenlee RT, Hill-Harmon MB, Murray T, et al. Cancer statistics, 2001. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:15–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, et al. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuhaus P, Jonas S, Bechstein WO, et al. Extended resections for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1999;230:808–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondo S, Hirano S, Ambo Y, et al. Forty consecutive resections of hilar cholangiocarcinoma with no postoperative mortality and no positive ductal margins: results of a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2004;240:95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rea DJ, Munoz-Juarez M, Farnell MB, et al. Major hepatic resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of 46 patients. Arch Surg. 2004;139:514–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henson DE, Albores-Saavedra J, Corle D. Carcinoma of the gallbladder: histologic types, stage of disease, grade, and survival rates. Cancer. 1992;70:1493–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoang MP, Murakata LA, Katabi N, et al. Invasive papillary carcinomas of the extrahepatic bile ducts: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. Modern Pathol. 2002;15:1251–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albores-Saavedra J, Murakata L, Krueger JE, et al. Non-invasive and minimally invasive papillary carcinomas of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Cancer. 2000;89:508–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinbren K, Mutum SS. Pathological aspects of cholangiocarcinoma. J Pathol. 1983;139:217–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kluge R, Schmidt F, Caca K, et al. Positron emission tomography with [(18)F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose for diagnosis and staging of bile duct cancer. Hepatology. 2001;33:1029–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blumgart LH, Benjamin IS. Liver resection for bile duct cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 1989;69:323–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarnagin WR, Bodniewicz J, Dougherty E, et al. A prospective analysis of staging laparoscopy in patients with primary and secondary hepatobiliary malignancies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber SM, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, et al. Staging laparoscopy in patients with extrahepatic biliary carcinoma: analysis of 100 patients. Ann Surg. 2002;235:392–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin RC, Brennan MF, Jaques DP. Quality of complication recording in the surgical literature. Ann Surg. 2002;235:803–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Joint Commission on Cancer. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Statist Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawasaki S, Imamura H, Kobayashi A, et al. Results of surgical resection for patients with hilar bile duct cancer: application of extended hepatectomy after biliary drainage and hemihepatic portal vein embolization. Ann Surg. 2003;238:84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belghiti J, Di Carlo I, Sauvanet A, et al. A ten-year experience with hepatic resection in 338 patients: evolutions in indications and of operative mortality. Eur J Surg. 1994;160:277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y, et al. Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1803 consecutive cases over the past decade. Ann Surg. 2002;236:397–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strong RW. Surgical resection for cholangiocarcinoma involving the confluence of the major hepatic ducts. Aust NZ J Surg. 1987;57:911–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su CH, Tsay SH, Wu CC, et al. Factors influencing postoperative morbidity, mortality, and survival after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1996;223:384–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rashid A. Cellular and molecular biology of biliary tract cancers. Surg Oncol Clin North Am. 2002;11:995–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abraham SC, Lee JH, Hruban RH, et al. Molecular and immunohistochemical analysis of intraductal papillary neoplasms of the biliary tract. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:902–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Kondo S, et al. Aggressive preoperative management and extended surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Nagoya experience. J HBP Surg. 2000;7:155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebata T, Nagino M, Kamiya J, et al. Hepatectomy with portal vein resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: audit of 52 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2003;238:720–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]