Abstract

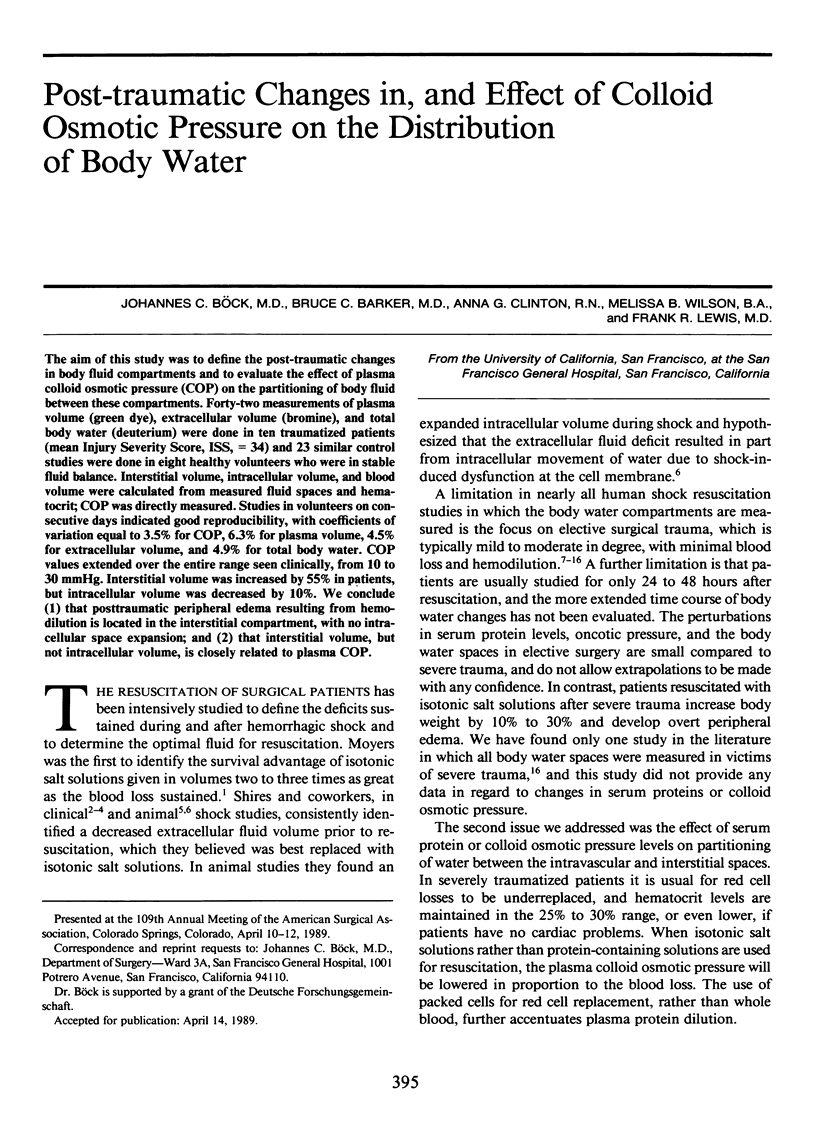

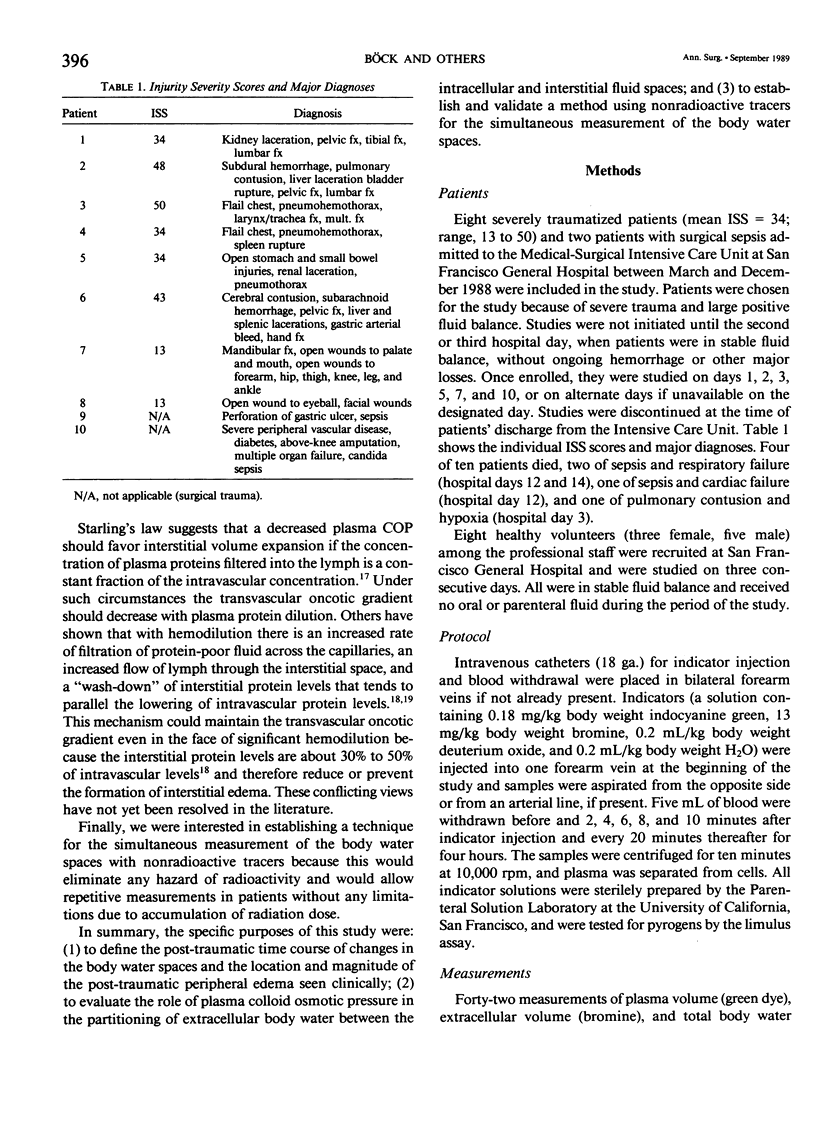

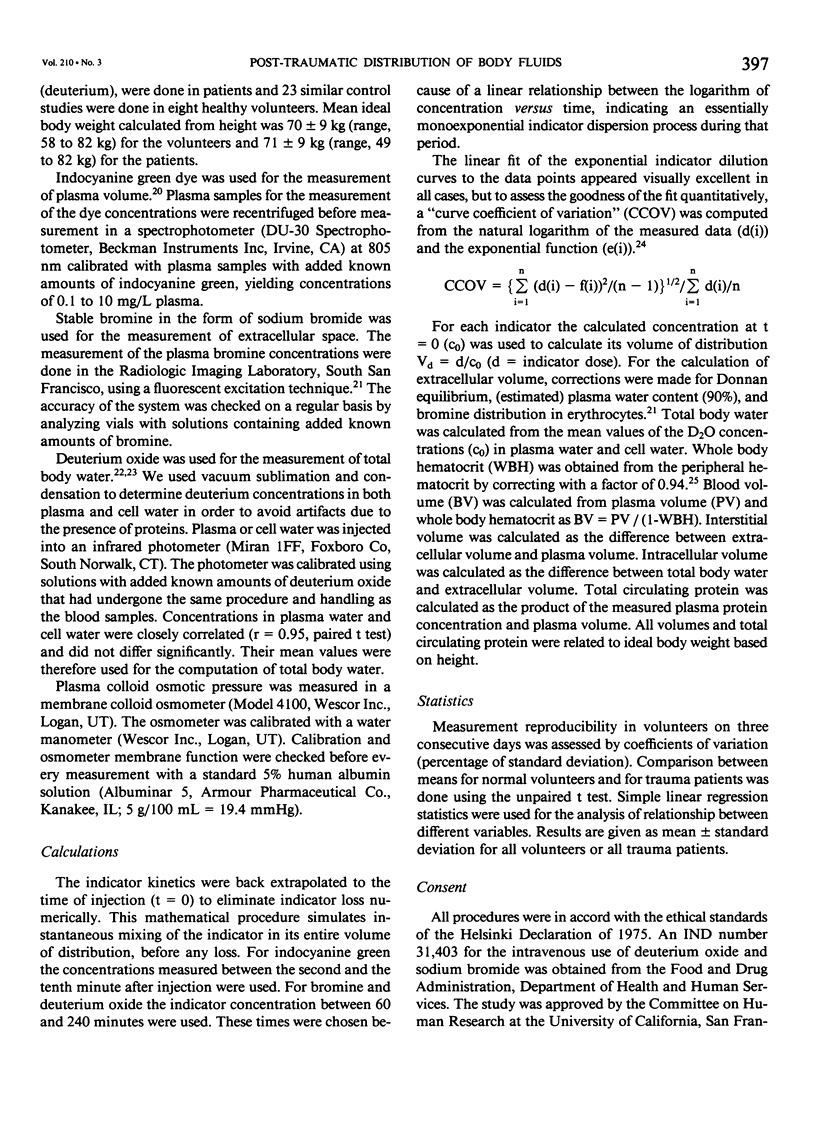

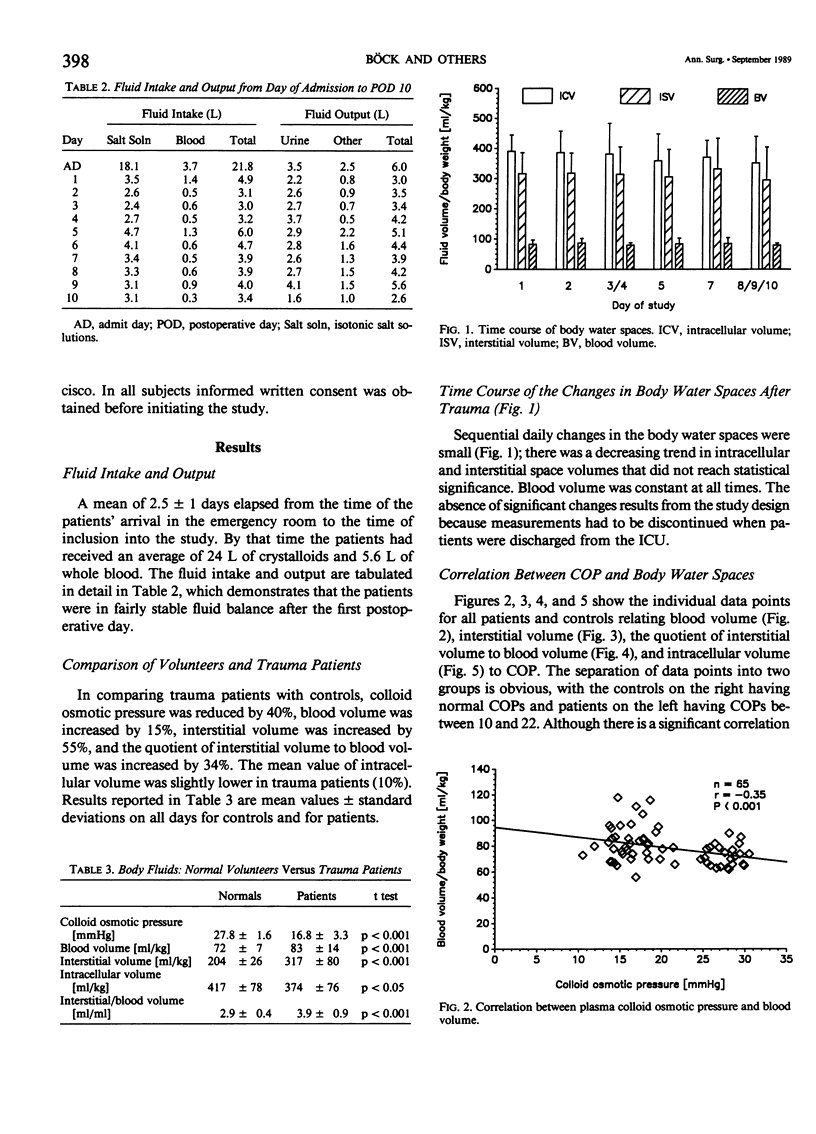

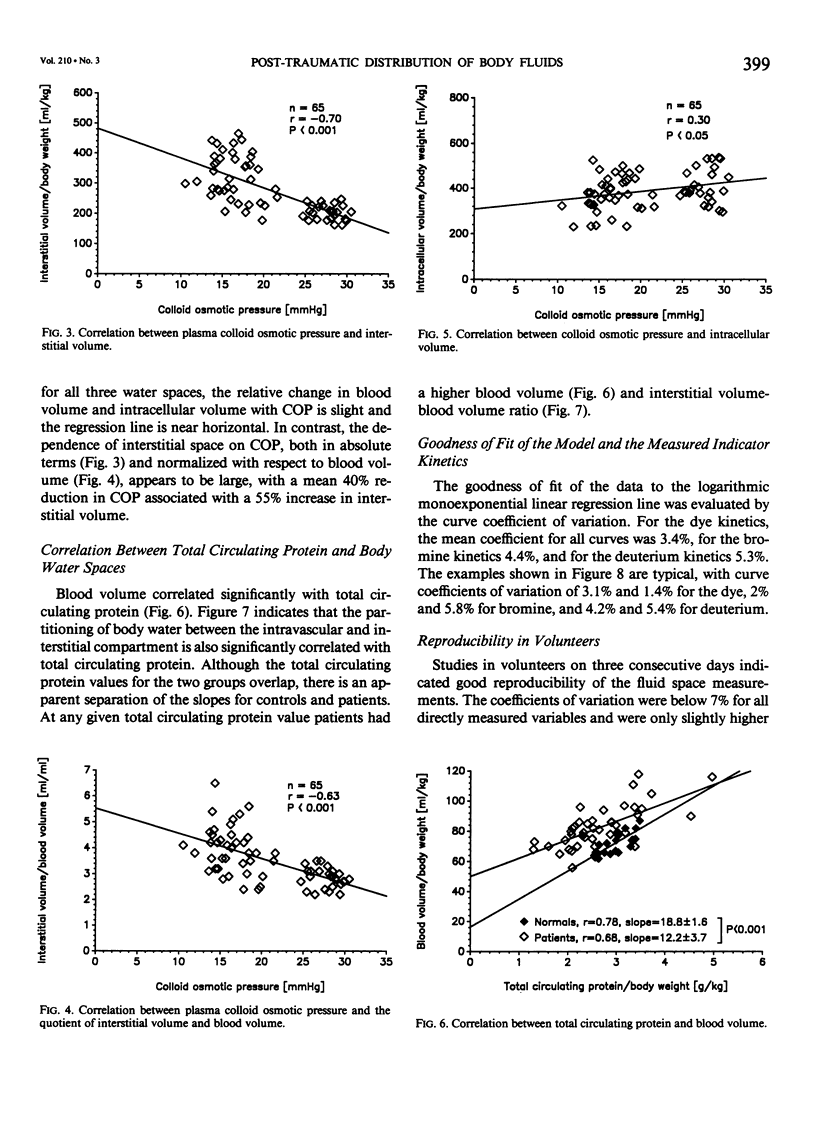

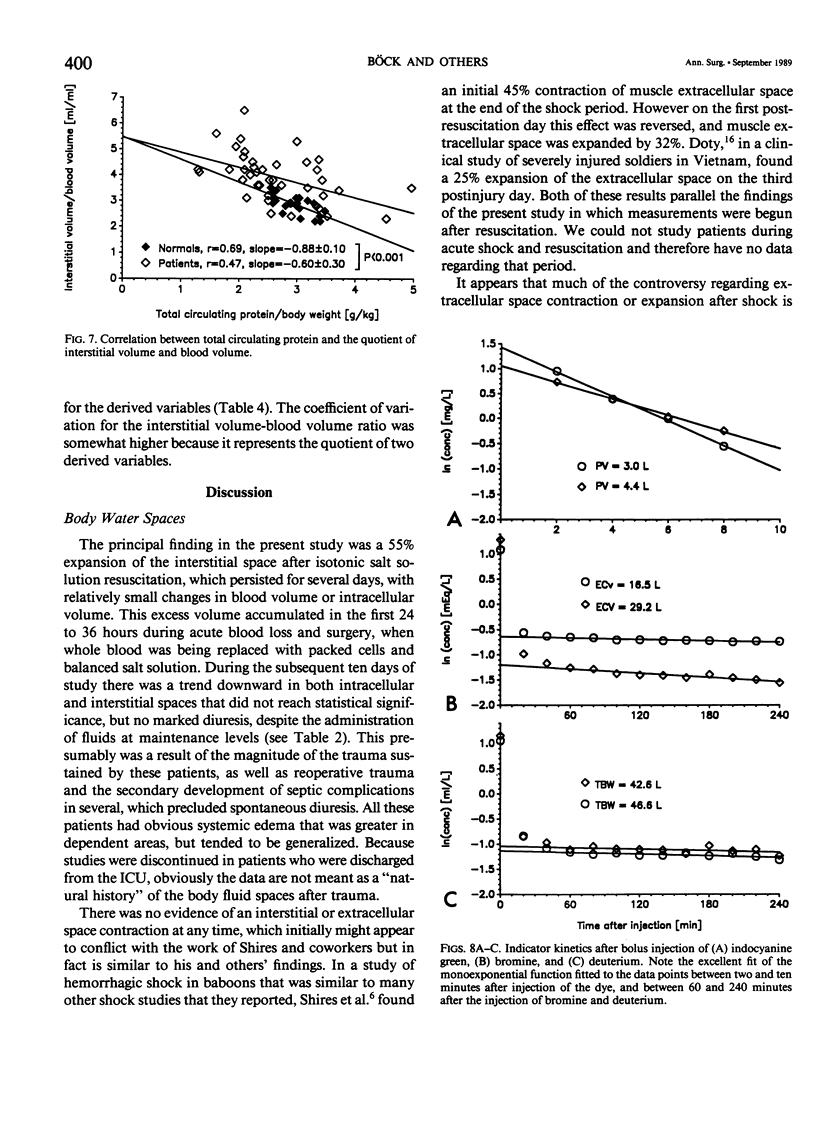

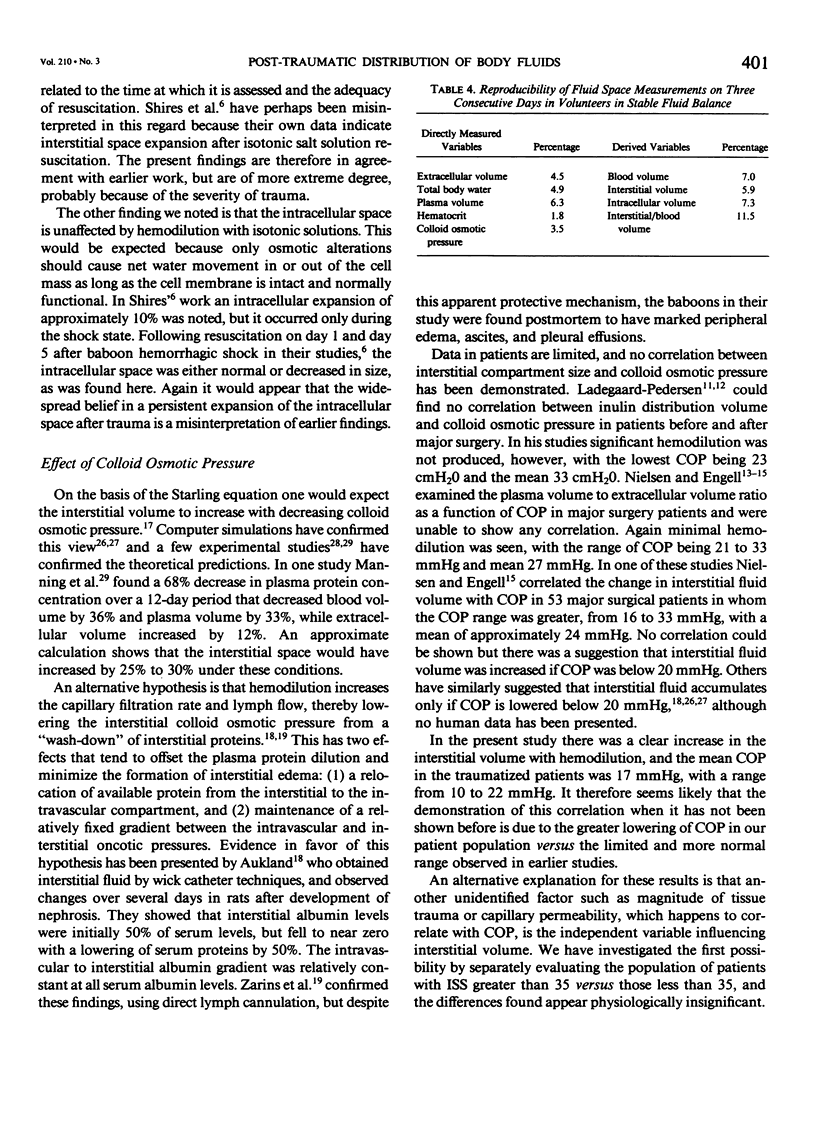

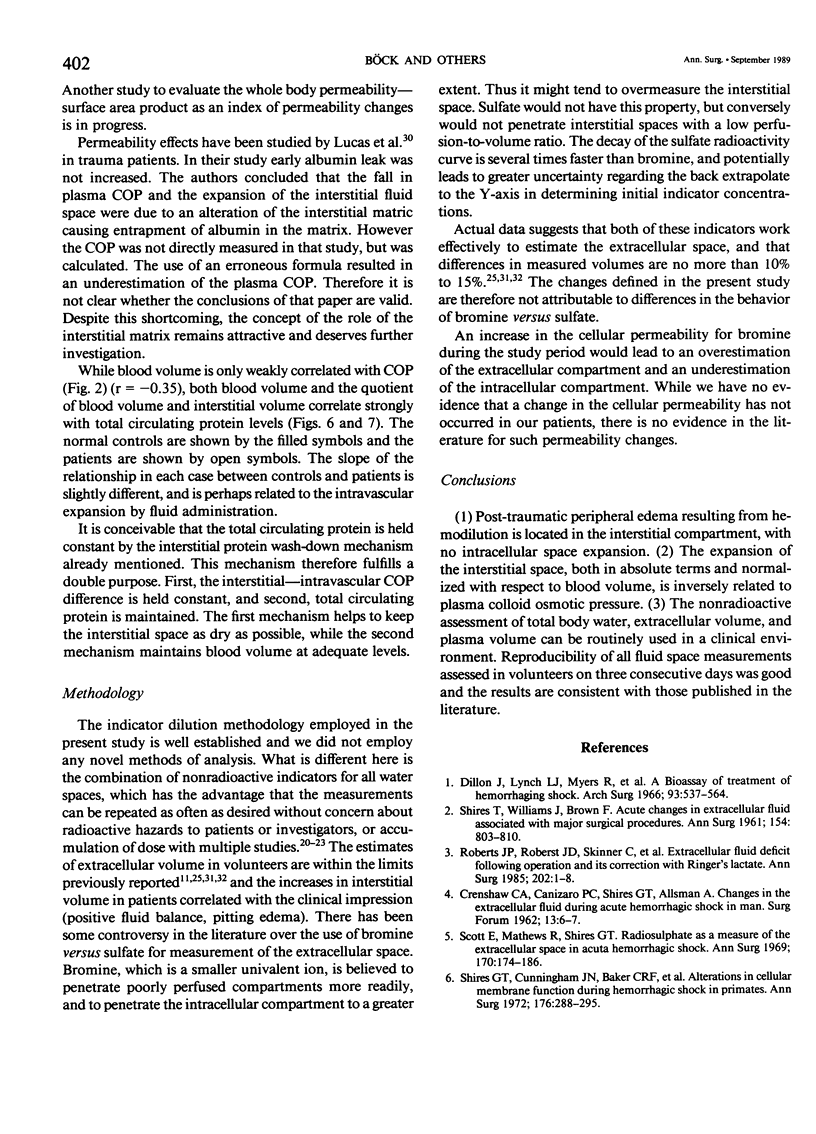

The aim of this study was to define the post-traumatic changes in body fluid compartments and to evaluate the effect of plasma colloid osmotic pressure (COP) on the partitioning of body fluid between these compartments. Forty-two measurements of plasma volume (green dye), extracellular volume (bromine), and total body water (deuterium) were done in ten traumatized patients (mean Injury Severity Score, ISS, = 34) and 23 similar control studies were done in eight healthy volunteers who were in stable fluid balance. Interstitial volume, intracellular volume, and blood volume were calculated from measured fluid spaces and hematocrit; COP was directly measured. Studies in volunteers on consecutive days indicated good reproducibility, with coefficients of variation equal to 3.5% for COP, 6.3% for plasma volume, 4.5% for extracellular volume, and 4.9% for total body water. COP values extended over the entire range seen clinically, from 10 to 30 mmHg. Interstitial volume was increased by 55% in patients, but intracellular volume was decreased by 10%. We conclude (1) that posttraumatic peripheral edema resulting from hemodilution is located in the interstitial compartment, with no intracellular space expansion; and (2) that interstitial volume, but not intracellular volume, is closely related to plasma COP.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aukland K. Editorial: Autoregulation of interstitial fluid volume. Edema-preventing mechanisms. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1973 May;31(3):247–254. doi: 10.3109/00365517309082428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassingthwaighte J. B., Ackerman F. H., Wood E. H. Applications of the lagged normal density curve as a model for arterial dilution curves. Circ Res. 1966 Apr;18(4):398–415. doi: 10.1161/01.res.18.4.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E. C., Barr J. W. Determination of blood volume using indocyanine green (cardio-green) dye. Life Sci. 1968 Sep 1;7(17):1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(68)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böck J., Heidelmeyer C., Gersing E., Pahl R., Hellige G. Simultaneous fiberoptic detection of the kinetics of heavy water and indocyanine green dye in arterial vessels. Biomed Tech (Berl) 1988 Jan-Feb;33(1-2):6–9. doi: 10.1515/bmte.1988.33.1-2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CRENSHAW C. A., CANIZARO P. C., SHIRES G. T., ALLSMAN A. Changes in extracellular fluid during acute hemorrhagic shock in man. Surg Forum. 1962;13:6–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervera A. L., Moss G. Crystalloid distribution following hemorrhage and hemodilution: mathematical model and prediction of optimum volumes for equilibration at normovolemia. J Trauma. 1974 Jun;14(6):506–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland J., Pluth J. R., Tauxe W. N., Kirklin J. W. Blood volume and body fluid compartment changes soon after closed and open intracardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1966 Nov;52(5):698–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon J., Lynch L. J., Jr, Myers R., Butcher H. R., Jr, Moyer C. A. A bioassay of treatment of hemorrhagic shock. I. The roles of blood, Ringer's solution with lactate, and macromolecules (dextran and hydroxyethyl starch) in the treatment of hemorrhagic shock in the anesthetized dog. Arch Surg. 1966 Oct;93(4):537–555. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1966.01330040001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty D. B., Hufnagel H. V., Moseley R. V. The distribution of body fluids following hemorrhage and resuscitation in combat casualties. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1970 Mar;130(3):453–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutelius J. R., Shizgal H. M., Lopez G. The effect of trauma on extracellular water volume. Arch Surg. 1968 Aug;97(2):206–214. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1968.01340020070008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JONES H. S., TERRY M. L. Determination of bromide space by means of a polarographic method. J Lab Clin Med. 1958 Apr;51(4):609–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman L., Wilson C. J. Determination of extracellular fluid volume by fluorescent excitation analysis of bromine. J Nucl Med. 1973 Nov;14(11):812–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladegaard-Pedersen H. J., Engell H. C. A comparison between the changes in the distribution volumes of inulin and [51Cr]EDTA after major surgery. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1975 Mar;35(2):109–113. doi: 10.1080/00365517509087213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladegaard-Pedersen H. J. Inulin distribution volume, plasma volume, and colloid osmotic pressure before and after major surgery. Acta Chir Scand. 1974;140(7):505–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas C. E., Benishek D. J., Ledgerwood A. M. Reduced oncotic pressure after shock: a proposed mechanism. Arch Surg. 1982 May;117(5):675–679. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380290121021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning R. D., Jr, Guyton A. C. Dynamics of fluid distribution between the blood and interstitium during overhydration. Am J Physiol. 1980 May;238(5):H645–H651. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.238.5.H645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning R. D., Jr, Guyton A. C. Effects of hypoproteinemia on fluid volumes and arterial pressure. Am J Physiol. 1983 Aug;245(2):H284–H293. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.245.2.H284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton E. S., Mathews R., Shires G. T. Radiosulphate as a measure of the extracellular fluid in acute hemorrhagic shock. Ann Surg. 1969 Aug;170(2):174–186. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196908000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore F. D., Dagher F. J., Boyden C. M., Lee C. J., Lyons J. H. Hemorrhage in normal man. I. distribution and dispersal of saline infusions following acute blood loss: clinical kinetics of blood volume support. Ann Surg. 1966 Apr;163(4):485–504. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196604000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen O. M., Engell H. C. Increased glomerular filtration rate in patients after reconstructive surgery on the abdominal aorta. Br J Surg. 1986 Jan;73(1):34–37. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800730113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen O. M., Engell H. C. The importance of plasma colloid osmotic pressure for interstitial fluid volume and fluid balance after elective abdominal vascular surgery. Ann Surg. 1986 Jan;203(1):25–29. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198601000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen O. M. Extracellular volume, renal clearance and whole body permeability-surface area product in man, measured after single injection of polyfructosan. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1985 May;45(3):217–222. doi: 10.3109/00365518509160998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts J. P., Roberts J. D., Skinner C., Shires G. T., 3rd, Illner H., Canizaro P. C., Shires G. T. Extracellular fluid deficit following operation and its correction with Ringer's lactate. A reassessment. Ann Surg. 1985 Jul;202(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198507000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth E., Lax L. C., Maloney J. V., Jr Ringer's lactate solution and extracellular fluid volume in the surgical patient: a critical analysis. Ann Surg. 1969 Feb;169(2):149–164. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196902000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIRES T., WILLIAMS J., BROWN F. Acute change in extracellular fluids associated with major surgical procedures. Ann Surg. 1961 Nov;154:803–810. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196111000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIRES T., WILLIAMS J., BROWN F. Simultaneous measurement of plasma volume, extracellular fluid volume, and red blood cell mass in man utilizing I-131, S-35-labeled sulfate, and Cr-51. J Lab Clin Med. 1960 May;55:776–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shires G. T., Cunningham J. N., Backer C. R., Reeder S. F., Illner H., Wagner I. Y., Maher J. Alterations in cellular membrane function during hemorrhagic shock in primates. Ann Surg. 1972 Sep;176(3):288–295. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197209000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starling E. H. On the Absorption of Fluids from the Connective Tissue Spaces. J Physiol. 1896 May 5;19(4):312–326. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1896.sp000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virtue R. W., LeVine D. S., Aikawa J. K. Fluid shifts during the surgical period: RISA and S35 determiniations following glucose, saline or lactate infusion. Ann Surg. 1966 Apr;163(4):523–528. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196604000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederhielm C. A. Dynamics of transcapillary fluid exchange. J Gen Physiol. 1968 Jul 1;52(1):29–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarins C. K., Rice C. L., Peters R. M., Virgilio R. W. Lymph and pulmonary response to isobaric reduction in plasma oncotic pressure in baboons. Circ Res. 1978 Dec;43(6):925–930. doi: 10.1161/01.res.43.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]